Abstract

While autophagy has been shown to act as an anti-viral defense, the Picornaviridae avoid and, in many cases, subvert this pathway to promote their own replication. Evidence indicates that some picornaviruses hijack autophagy in order to induce autophagosome-like membrane structures for genomic RNA replication. Expression of picornavirus proteins can specifically induce the machinery of autophagy, although the mechanisms by which the viruses employ autophagy appear to differ. Many picornaviruses up-regulate autophagy in order to promote viral replication while some members of the family also inhibit degradation by autolysosomes. Here we explore the unusual relationship of this medically important family of viruses with a degradative mechanism of innate immunity.

1. Introduction

Autophagy is a cellular process by which cytosolic material is targeted for degradation by the cell [1]. Autophagy initiates when proteins, membranes, and organelles are engulfed into a unique double-membraned structure known as an autophagosome. This vesicle matures by acidification and fuses with lysosomes to form the degradative autolysosome [2]. Autophagy plays important roles in breaking down protein aggregates and cellular structures as well as recycling of intracellular components [3]. In addition to maintaining cellular homeostasis, autophagy can be induced by cellular stressors such as starvation, drug treatments, or infection. Autophagy is also as a mechanism by which the cell controls infection through degradation of cytosolic viruses and bacteria [4,5]. However, as is true for most immune responses, several pathogens subvert the autophagic machinery in order to promote their survival and replication.

In retrospect, the history of picornaviruses and autophagosomes stretches back to some of the earliest fine-detailed microscopic analyses of infected cells. For years, scientists have been learning how this medically important class of viruses rearranges cellular ultrastructure. In 1958, the first electron microscopy (EM) analysis was carried out by Marguerite Vogt’s group, using monkey kidney cells infected with poliovirus (PV) [6]. This study, one of the first EM studies conducted on a uniformly infected, synchronous population of infected cells, identified cytoplasmic vesicles termed by the authors “U bodies”. The presence of U bodies correlated with the maximal release of virus from the cells. As lysis approached, clear vacuoles were seen in place of the U bodies. The techniques used were insufficient to identify virions during infection. However, this work clearly established the unusual pattern of membrane rearrangements in the cytoplasm of picornavirus-infected cells.

In 1962, Samuel Dales and Richard Franklin published a fine structure study of murine L cells infected with encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) [7]. The images demonstrate cytoplasmic regions filled with multi-lamellar structures, which we would now identify as autophagosomes. This study marks the first demonstration that we can find of autophagic induction in a picornavirus-infected cell. Although large crystalline arrays of virus are observed in the cytoplasm, it is difficult to tell if any are within the membrane-bound cytoplasmic bodies.

In 1965, Dales, working with George Palade, published a comprehensive EM analysis of PV-infected cells [8]. The authors analyzed HeLa cells treated with PV at a high multiplicity of infection (MOI = 22) and used EM protocols that provided high-contrast images of intracellular membranes. In their images, Dales and Palade identified “membrane-enclosed cell bodies” occupying nearly the entire cytoplasm of the cell. They identified these bodies, which they measured to be 70–200 nm each in diameter, to be the same as the U bodies observed by Vogt. In the Dales study, progeny virus particles were observed both inside and outside the small bodies. These vesicles clearly have two lipid bilayers with an electron-light luminal region in between, a hallmark of classical autophagosomes. The authors suggested that newly formed viral particles were being taken up into these vesicles as a response to infection.

The question remained whether such vesicles are present or relevant during infections in vivo. It was not until 1984 that the neurons of PV-infected monkeys were examined at the level of electron microscopy [9]. The double-membraned vesicles seen in this in vivo study bear a strong resemblance to the vesicles identified by Dales and Palade in HeLa cells, and are strikingly similar to autophagosomes. This same study found double-membraned vesicles in PV-infected cultured cynomolgus monkey kidney (CMK) cells, indicating that the membrane rearrangements in cultured cells reflect in vivo intracellular rearrangements. Therefore, these membranes have been the subject of intense study for years.

Although the molecular tools to conclusively identify these membranes as autophagosomes would not be available for years, the evidence for double-membraned vesicle formation during picornavirus infection has been accumulating for more than half a century. Many questions remained—first and foremost being what role these vesicles play in the virus life cycle and the interaction between the virus and its host.

3. Poliovirus Subversion of the Autophagic Machinery

In order to understand the nature and origin of the observed vesicles, immuno-EM experiments were performed on PV-infected HeLa cells [24]. Initial experiments suggested that PV induced double-membraned autophagic-like structures 50–500 nm in diameter. While this is consistent with previous work, these structures are smaller than typical autophagosomes, which range from 500–1500 nm in diameter [8,25]. Using an antibody to the viral protein 2C to identify PV-relevant vesicles, cellular fractionation studies showed that these vesicles co-sediment with a variety of markers for ER, Golgi, and lysosomes [24,26]. Since autophagosomes contain markers from throughout the cell, these data led to the hypothesis that autophagy is involved in the formation of PV-induced membranes.

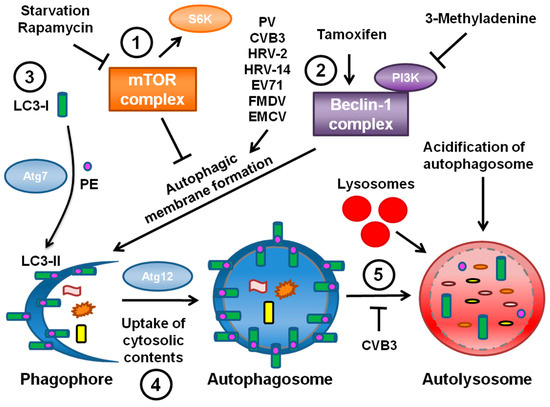

Confirmation of the nature of these vesicles had to wait for the identification of specific markers to monitor autophagosome formation, maturation and degradation. Genetic studies of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae identified several genes, now termed ATG genes, essential for the autophagic pathway. Many of these genes are conserved in mammalian systems [27]. Although the signals leading to autophagic induction are still poorly understood, these studies have provided cellular protein markers for autophagosomal membranes and autophagic degradation, as shown in Figure 1.

Microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 (LC3), the mammalian homolog of yeast ATG8p, is a specific marker of autophagic membranes. LC3 is found in the cytoplasm when autophagy levels are low; this form is known as LC3-I. However, upon induction of autophagy LC3-I is conjugated to phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) and thereafter becomes membrane-bound to autophagosomes; this form is known as LC3-II (Figure 1, part 3) [28]. LC3-II appears to be required to complete formation of the autophagosome [29]. The isoforms of LC3 can be distinguished by Western blotting and a relative increase in LC3-II levels is indicative of increased autophagy. In addition, LC3 conjugated to GFP can be expressed in cells and monitored by immunofluorescence; LC3-GFP will form puncta in response to induction of autophagy. The ubiquitin-binding protein p62 also interacts with LC3-II in order to target cargo to autophagosomes for degradation [30]. Since p62 is degraded along with the rest of the autophagosome contents, steady-state levels of p62 can be monitored as an indicator of autophagic degradation levels. Advances in technology also allowed for the manipulation of the autophagic pathway via gene knockdown of various ATG proteins, the effects of which could be assessed by these newly available assays.

Using LC3 as a marker, studies were undertaken to investigate the PV-induced vesicles [31]. When GFP-LC3 was expressed in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells during PV infection, the GFP signal co-localized with the viral 3A protein, a component of viral replication complexes on host membranes [32]. Immunofluorescence showed that inducing autophagy using the pharmacological inducers rapamycin or tamoxifen when GFP-LC3 was expressed induced puncta indicative of autophagy.

During infection, punctate LC3 also co-localized with lysosomal-associated membrane protein LAMP1, a marker of late endosomes and lysosomes [31]. Studies of Legionella pneumophila had previously established co-localization of punctate LC3 with LAMP1 as an assay for identifying mature autophagosomes [33]. These data suggested that autophagosomes were forming and perhaps maturing in the presence of PV. When the viral proteins 2BC or 3A were individually expressed in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells, this co-localization was not observed. Only when the two proteins were co-expressed did LAMP1 co-localize with GFP-LC3.

When rapamycin or tamoxifen were present during infection of H1-HeLa cells the intracellular production of PV increased [31]. However, the autophagy inhibitor drug 3-MA decreased viral yield. In addition, RNAi directed against LC3 or ATG12 reduced both intracellular and extracellular viral titers. This study provided the first evidence that PV subverts the autophagic pathway in order to generate membranes for establishing viral replication complexes. The effect of inhibiting autophagy was more pronounced on levels of virus found in the medium prior to cell lysis than on cell-associated virus. Therefore, these data provided the first indication that the autophagy pathway plays a role in extracellular release of cytosolic contents. The existence of a non-conventional secretory pathway regulated by autophagy has now been confirmed using several other assays [34,35,36].

5. The Roles of Specific Viral Proteins in Induction of Autophagic Signaling

Most of what is known about the virus proteins involved in induction and regulation of autophagy comes from studies of PV. The contiguous region of the viral genome spanning the proteins 2B, 2C, and 3A is involved in altering the physical structure of the cell during virus replication. Previous studies have shown that expression of the viral protein 3A leads to severe swelling of the ER due to inhibition of the ER-Golgi trafficking, while the 2C protein plays a role in host membrane rearrangements and viral replication [46,47,48]. The 2C protein did not co-fractionate with the ER marker p63. When 3A was expressed singly or co-expressed with 2C, the ER marker calnexin did co-fractionate with these viral proteins [26]. It is possible that some host proteins may be excluded from these membranes due to modification by the viral proteins, but more research needs to be performed to investigate this phenomenon.

Expression of the viral precursor protein 2BC yielded single-membraned electron-light vesicles, in contrast to those induced by infection with PV [26]. Co-expression of 2BC and 3A not only showed membranes of a similar density to those induced by PV, but those membranes appeared to be autophagosome-like as well. This work not only provided a new method for examining autophagosomes, but identified the specific viral proteins that play a role in inducing autophagosome-like vesicles.

In addition to generating single-membraned vesicles, 2BC is sufficient to induce lipidation of cytosolic LC3-I to generate membrane-associated LC3-II [26,48]. Interestingly, expression of either 2B or 2C alone was not sufficient to increase LC3-II levels, indicating that a function of the 2BC precursor is required for this effect [49]. 2BC was among the first proteins identified shown to be sufficient for induction of autophagic signaling. This makes it all the more curious that classical double-membraned autophagosomes are not observed when 2BC is expressed alone. These data indicated for the first time that LC3-II formation is not sufficient for autophagosome formation. The specific role of 3A in forming autophagosomes is not yet understood.

Little is known about the proteins of other picornaviruses and their roles in inducing or regulating autophagy. When expressed in the absence of other viral proteins, the EMCV and FMDV 3A proteins each co-localize with GFP-LC3 [43,44]. These results are similar to those seen with PV 3A [31]. It has been shown that co-expression of FMDV 2B and 2C is sufficient to recapitulate certain functions of 2BC, but this is not the case for co-expression of PV 2B and 2C [49,50]. Therefore, the role of 2BC and its cleavage products may differ between FMDV and PV. It is unclear if the 2BC and 3A proteins of HRV-14 and CVB3 exhibit analogous functions during infection. More research is needed to fully understand how the picornaviruses utilize these proteins, perhaps in different ways, in order to induce and regulate autophagy.

Acknowledgments

The authors were supported by the Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin fund.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References and Notes

- Yang, Z.; Klionsky, D.J. Eaten alive: A history of macroautophagy. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010, 12, 814–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deretic, V.; Levine, B. Autophagy, immunity, and microbial adaptations. Cell Host Microbe 2009, 5, 527–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, B.; Mizushima, N.; Virgin, H.W. Autophagy in immunity and inflammation. Nature 2011, 469, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudchodkar, S.B.; Levine, B. Viruses and Autophagy. Rev. Med. Virol. 2009, 19, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deretic, V. Autophagy in immunity and cell-autonomous defense against intracellular microbes. Immunol. Rev. 2011, 240, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallman, F.; Williams, R.C.; Dulbecco, R.; Vogt, M. Fine structure of changes produced in cultured cells sampled at specified intervals during a single growth cycle of polio virus. J. Biophys. Biochem. Cytol. 1958, 4, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dales, S.; Franklin, R.M. A comparison of the changes in fine structure of l cells during single cycles of viral multiplication, following their infection with the viruses of mengo and encephalomyocarditis. J. Cell Biol. 1962, 14, 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dales, S.; Eggers, H.J.; Tamm, I.; Palade, G.E. Electron microscopic study of the formation of poliovirus. Virology 1965, 26, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, I.; Hagiwara, A.; Komatsu, T. Ultrastructural studies on the pathogenesis of poliomyelitis in monkeys infected with poliovirus. Acta Neuropathol. 1984, 64, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salonen, A.; Ahola, T.; Kaariainen, L. Viral RNA replication in association with cellular membranes. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2005, 285, 139–173. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie, J. Wrapping things up about virus RNA replication. Traffic 2005, 6, 967–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, D.J.; Schwartz, M.D.; Dye, B.T.; Ahlquist, P. Engineered retargeting of viral RNA replication complexes to an alternative intracellular membrane. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 12193–12202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraris, P.; Blanchard, E.; Roingeard, P. Ultrastructural and biochemical analyses of hepatitis C virus-associated host cell membranes. J. Gen. Virol. 2010, 91, 2230–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knoops, K.; Kikkert, M.; Worm, S.H.; Zevenhoven-Dobbe, J.C.; van der Meer, Y.; Koster, A.J.; Mommaas, A.M.; Snijder, E.J. SARS-coronavirus replication is supported by a reticulovesicular network of modified endoplasmic reticulum. PLoS Biol. 2008, 6, e226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reggiori, F.; Monastyrska, I.; Verheije, M.H.; Cali, T.; Ulasli, M.; Bianchi, S.; Bernasconi, R.; de Haan, C.A.; Molinari, M. Coronaviruses hijack the LC3-I-positive EDEMosomes, ER-derived vesicles exporting short-lived ERAD regulators, for replication. Cell Host Microbe 2010, 7, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spuul, P.; Balistreri, G.; Kaariainen, L.; Ahola, T. Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase-, Actin-, and Microtubule-dependent transport of semliki forest virus replication complexes from the plasma membrane to modified lysosomes. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 7543–7557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopek, B.G.; Perkins, G.; Miller, D.J.; Ellisman, M.H.; Ahlquist, P. Three-dimensional analysis of a viral RNA replication complex reveals a virus-induced mini-organelle. PLoS Biol. 2007, 5, e220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rust, R.C.; Landmann, L.; Gosert, R.; Tang, B.L.; Hong, W.; Hauri, H.P.; Egger, D.; Bienz, K. Cellular COPII proteins are involved in production of the vesicles that form the poliovirus replication complex. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 9808–9818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belov, G.A.; Altan-Bonnet, N.; Kovtunovych, G.; Jackson, C.L.; Lippincott-Schwartz, J.; Ehrenfeld, E. Hijacking components of the cellular secretory pathway for replication of poliovirus RNA. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 558–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogerus, C.; Egger, D.; Samuilova, O.; Hyypia, T.; Bienz, K. Replication complex of human parechovirus 1. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 8512–8523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiner, C.A.; Jackson, W.T. Fragmentation of the Golgi apparatus provides replication membranes for human rhinovirus 1A. Virology 2010, 407, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krogerus, C.; Samuilova, O.; Poyry, T.; Jokitalo, E.; Hyypia, T. Intracellular localization and effects of individually expressed human parechovirus 1 non-structural proteins. J. Gen. Virol. 2007, 88, 831–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jauka, T.; Mutsvunguma, L.; Boshoff, A.; Edkins, A.L.; Knox, C. Localisation of Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus protein 2C to the golgi apparatus using antibodies generated against a peptide region. J. Virol. Methods 2010, 168, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegel, A.; Giddings, T.H., Jr; Ladinsky, M.S.; Kirkegaard, K. Cellular origin and ultrastructure of membranes induced during poliovirus infection. J. Virol. 1996, 70, 6576–6588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizushima, N.; Ohsumi, Y.; Yoshimori, T. Autophagosome formation in mammalian cells. Cell Struct. Funct. 2002, 27, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suhy, D.A.; Giddings, T.H., Jr; Kirkegaard, K. Remodeling the endoplasmic reticulum by poliovirus infection and by individual viral proteins: An autophagy-like origin for virus-induced vesicles. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 8953–8965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukada, M.; Ohsumi, Y. Isolation and characterization of autophagy-defective mutants of saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 1993, 333, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeya, Y.; Mizushima, N.; Ueno, T.; Yamamoto, A.; Kirisako, T.; Noda, T.; Kominami, E.; Ohsumi, Y.; Yoshimori, T. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 5720–5728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, N.; Hayashi-Nishino, M.; Fukumoto, H.; Omori, H.; Yamamoto, A.; Noda, T.; Yoshimori, T. An Atg4B mutant hampers the lipidation of LC3 paralogues and causes defects in autophagosome closure. Mol. Biol. Cell 2008, 19, 4651–4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankiv, S.; Clausen, T.H.; Lamark, T.; Brech, A.; Bruun, J.A.; Outzen, H.; Overvatn, A.; Bjorkoy, G.; Johansen, T. P62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 24131–24145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, W.T.; Giddings, T.H., Jr; Taylor, M.P.; Mulinyawe, S.; Rabinovitch, M.; Kopito, R.R.; Kirkegaard, K. Subversion of cellular autophagosomal machinery by RNA viruses. PLoS Biol. 2005, 3, e156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giachetti, C.; Hwang, S.S.; Semler, B.L. Cis-acting lesions targeted to the hydrophobic domain of a poliovirus membrane protein involved in RNA replication. J. Virol. 1992, 66, 6045–6057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanson, M.S.; Isberg, R.R. Analysis of the intracellular fate of legionella pneumophila mutants. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1996, 797, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manjithaya, R.; Subramani, S. Autophagy: A broad role in unconventional protein secretion? Trends Cell Biol. 2011, 21, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duran, J.M.; Anjard, C.; Stefan, C.; Loomis, W.F.; Malhotra, V. Unconventional secretion of Acb1 is mediated by autophagosomes. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 188, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manjithaya, R.; Anjard, C.; Loomis, W.F.; Subramani, S. Unconventional secretion of pichia pastoris Acb1 is dependent on grasp protein, peroxisomal functions, and autophagosome formation. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 188, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, J.; Zhang, J.; Si, X.; Gao, G.; Mao, I.; McManus, B.M.; Luo, H. Autophagosome supports coxsackievirus B3 replication in host cells. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 9143–9153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talloczy, Z.; Jiang, W.; Virgin, H.W., 4th; Leib, D.A.; Scheuner, D.; Kaufman, R.J.; Eskelinen, E.L.; Levine, B. Regulation of starvation- and virus-induced autophagy by the eIF2alpha kinase signaling pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002, 99, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemball, C.C.; Alirezaei, M.; Flynn, C.T.; Wood, M.R.; Harkins, S.; Kiosses, W.B.; Whitton, J.L. Coxsackievirus infection induces autophagy-like vesicles and megaphagosomes in pancreatic acinar cells in vivo. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 12110–12124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.Y.; Ha, Y.E.; Choi, J.E.; Ahn, J.; Lee, H.; Kweon, H.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, D.H. Coxsackievirus B4 uses autophagy for replication after calpain activation in rat primary neurons. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 11976–11978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brabec-Zaruba, M.; Berka, U.; Blaas, D.; Fuchs, R. Induction of autophagy does not affect human rhinovirus type 2 production. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 10815–10817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, K.A.; Jackson, W.T. Human rhinovirus 2 induces the autophagic pathway and replicates more efficiently in autophagic cells. J. Virol 2011, 85, 9651–9654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.C.; Chang, C.L.; Wang, P.S.; Tsai, Y.; Liu, H.S. Enterovirus 71-induced autophagy detected in vitro and in vivo promotes viral replication. J. Med. Virol. 2009, 81, 1241–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, V.; Pacheco, J.M.; LaRocco, M.; Burrage, T.; Jackson, W.; Rodriguez, L.L.; Borca, M.V.; Baxt, B. Foot-and-mouth disease virus utilizes an autophagic pathway during viral replication. Virology 2011, 410, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Xinna, G.; Xin, G.; Yang, H. Autophagy promotes the replication of encephalomyocarditis virus in host cells. Autophagy 2011, 7, 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doedens, J.R.; Giddings, T.H., Jr; Kirkegaard, K. Inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum-to-golgi traffic by poliovirus protein 3A: Genetic and ultrastructural analysis. J. Virol. 1997, 71, 9054–9064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.W.; Teterina, N.; Egger, D.; Bienz, K.; Ehrenfeld, E. Membrane rearrangement and vesicle induction by recombinant poliovirus 2C and 2BC in human cells. Virology 1994, 202, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, D.J.; Flanegan, J.B. Synchronous replication of poliovirus RNA: Initiation of negative-strand RNA synthesis requires the guanidine-inhibited activity of protein 2C. J. Virol. 1997, 71, 8482–8489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.P.; Kirkegaard, K. Modification of cellular autophagy protein LC3 by poliovirus. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 12543–12553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffat, K.; Knox, C.; Howell, G.; Clark, S.J.; Yang, H.; Belsham, G.J.; Ryan, M.; Wileman, T. Inhibition of the secretory pathway by foot-and-mouth disease virus 2BC protein is reproduced by coexpression of 2B with 2C, and the site of inhibition is determined by the subcellular location of 2C. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 1129–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2011 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).