Abstract

Hexadecyloxypropyl-cidofovir (HDP-CDV) is a novel ether lipid conjugate of (S)-1-(3-hydroxy-2-phosphonoylmethoxypropyl)-cytosine (CDV) which exhibits a remarkable increase in antiviral activity against orthopoxviruses compared with CDV. In contrast to CDV, HDP-CDV is orally active and lacks the nephrotoxicity of CDV itself. Increased oral bioavailability and increased cellular uptake is facilitated by the lipid portion of the molecule which is responsible for the improved activity profile. The lipid portion of HDP-CDV is cleaved in the cell, releasing CDV which is converted to CDV diphosphate, the active metabolite. HDP-CDV is a highly effective agent against a variety of orthopoxvirus infections in animal models of disease including vaccinia, cowpox, rabbitpox and ectromelia. Its activity was recently demonstrated in a case of human disseminated vaccinia infection after it was added to a multiple drug regimen. In addition to the activity against orthopoxviruses, HDP-CDV (CMX001) is active against all double stranded DNA viruses including CMV, HSV-1, HSV-2, EBV, adenovirus, BK virus, orf, JC, and papilloma viruses, and is under clinical evaluation as a treatment for human infections with these agents.

Keywords:

antiviral drugs; Cidofovir; HPMPA; acyclic nucleoside phosphonates; smallpox; vaccinia; biodefense 1. Introduction

Smallpox was a major cause of mortality worldwide until it was eliminated by the WHO vaccination program in the late 1970s [1]. It was a disease easily transmitted by aerosol which caused 30% mortality and disfiguring skin lesions in survivors. Vaccination for smallpox was discontinued thereafter and the world population has become vulnerable again to the disease because of minimal herd immunity. Several years ago concern arose that smallpox could be used as a bioweapon by hostile groups or terrorists [2,3]. In addition, genetically modified strains of poxviruses were shown to be lethal to animals even though they had been preimmunized by vaccination [4]. Although vaccination is still considered as the primary approach to a potential recurrence of smallpox, many individuals are now immunosupressed because of HIV infections, cancer chemotherapy and organ transplantation. Immunosuppressed persons would not be good candidates for vaccination [5] and alternative therapies are needed. A screening effort was undertaken to find agents which inhibited the replication of poxviruses and could be developed as therapeutics.

2. Cidofovir Identified as an Effective Inhibitor of Poxviruses

(S)-1-(3-hydroxy-2-phosphono-methoxypropyl)adenine (HPMPA) and (S)-1-(3-hydroxy-2-phosphonomethoxypropyl)-cytosine (HPMPC, cidofovir) are acyclic nucleoside phosphonate antivirals first described by Holy and De Clercq [6,7]. Both HPMPA and HPMPC were shown to have antiviral activity in the vaccinia virus mouse tail lesion model [7,8]. HPMPC (cidofovir, CDV) was shown to be active in lethal aerosol or intranasal cowpox infections [9,10] when given by parenteral injection. CDV was also active when given as an aerosol in cowpox-infected mice [11]. However, CDV given intravenously has substantial nephrotoxicity which limits its dose to 5 mg/kg/week. In a smallpox outbreak, it would not be possible to use an intravenous drug with significant nephrotoxicity widely. An oral drug with less toxicity which could be delivered from a stockpile and self administered would be much more desirable for emergency use.

4. Synthesis of HDP-CDV

We next turned out attention to CDV, HPMPA, and the acyclic nucleoside phosphonates (ANPs). The ANPs can be regarded as close analogs of nucleoside monophosphates, except that they possess a metabolically stable phosphorus-carbon bond and lack a complete ribose or deoxyribose functionality. Unlike conventional nucleosides, ANPs do not require the often rate-limiting initial phosphorylation step for activation. As a result, ANPs like CDV and HPMPA are fully active against thymidine kinase or UL-97 mutant viruses which are resistant to acyclovir or ganciclovir. After conversion of ANPs to the active metabolite inside cells (ANP-diphosphate), the metabolites are generally retained inside cells for prolonged periods of time, which leads to more convenient dosing regimens [22]. However, ANPs have poor cellular permeation and oral bioavailability due to the charges on the phosphonic acid at physiologic pH levels. Another drawback involves their tendency to concentrate in the kidney proximal tubule, resulting in nephrotoxicity [22]. The next section describes the application of the alkoxyalkyl ester strategy to ANPs.

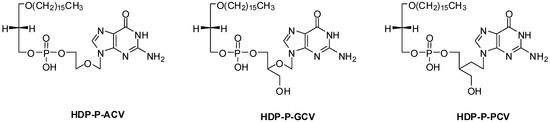

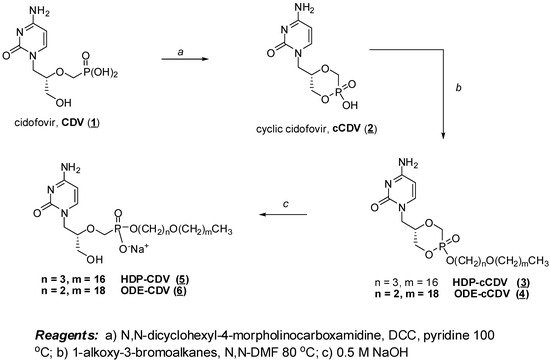

Synthesis of HDP-Cyclic-CDV and HDP-CDV

Building on early successes with HDP-P esters of acyclovir and ganciclovir, we synthesized the hexadecyloxypropyl and octadecyloxyethyl esters of CDV and cyclic CDV as shown in Figure 2 [23]. Briefly, CDV (1) was cyclized with dicyclohexylcarbodiimide to cyclic CDV (2) and esterified with 3-hexadecyloxy-1-propanol or 2-octadexyloxy-1-ethanol by the Mitsunobu reaction [24], yielding HDP-cyclic CDV (3) or ODE-cyclic CDV (4). The cyclic diesters were exposed to 0.5 N NaOH to open the ring, yielding HDP-CDV (5) or ODE-CDV (6). Alternative methods of synthesis of the alkoxyalkyl nucleoside phosphonates which are more suitable for scale up have been reported by Beadle and coworkers [25].

6. Mechanism of Action

6.1. Mechanism of Increased Antiviral Activity of HDP-CDV

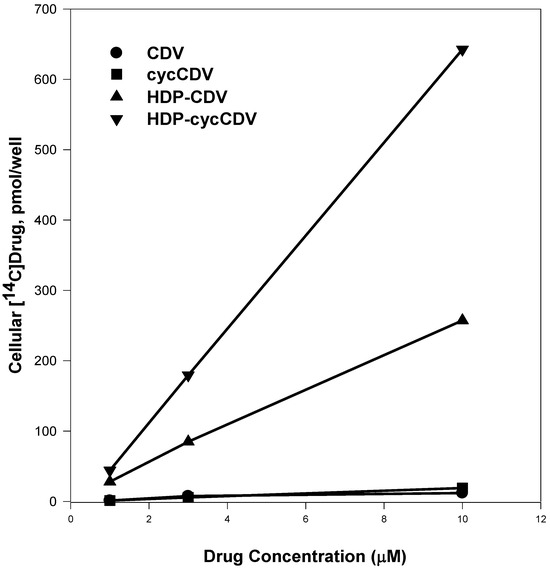

The increase in antiviral activity noted with HDP-CDV compared to CDV itself was unusually large (100-fold or more). To investigate the reason for this, we next evaluated the cellular uptake and metabolism of [2-14C]-CDV and HDP-[2-14C]-CDV in MRC-5 human lung fibroblasts, a common host cell for poxvirus study [28]. At four hours, the cellular radioactive drug content observed after exposure to 1 μM CDV was only 1.2 versus 28 picomoles/well with 1.0 μM HDP-CDV. At concentrations of 3 and 10 μM, drug uptake of HDP-CDV was 77 and 245 picomoles/well, an increase of 11- to 23-fold versus CDV (Figure 3). At 3 and 10 μM, the uptake of HDP-cCDV was approximately twice that of HDP-CDV and 32-fold greater than observed with cCDV (Figure 3). The mechanism of uptake has not been studied extensively, but it is believed that the HDP-CDV internalized after insertion into the plasma membrane bilayer outer leaflet as is typical for lysophospholipids. Transfer to the internal leaflet is probably spontaneous but may also be catalyzed by flippases. This process has not been studied in detail. In the cells phospholipase C or other phosphatases as yet unidentified, release CDV which is converted to the active metabolite by cellular enzymes. Conversion of HDP-CDV to CDV diphosphate (CDVpp), an analog of deoxycytidine triphosphate, was measured by HPLC. Cells exposed to CDV and HDP-CDV for 48 hours had 1.8 and 184 picomoles of CDVpp, respectively; a difference of 100-fold [28]. Thus, it seems clear that increased antiviral activity of HDP-CDV is due to increased cellular uptake and conversion to CDVpp, the inhibitor of poxvirus DNA polymerase.

Figure 3.

Uptake of 14C-labeled CDV, cyclic-CDV, HDP-cyclic-CDV and HDP-CDV in MRC-5 Human Lung Fibroblasts. Adapted from Reference 31.

6.2. Mechanism of Inhibition of Vaccinia DNA Polymerase by CDV Diphosphate

The mechanism of inhibition of the vaccinia polymerase had not been studied previously. Using the purified vaccinia E9L DNA polymerase and different primer template pairs, Wendy Magee and David Evans found that CDV was incorporated into the growing DNA strand opposite template G’s but at a lower catalytic efficiency than dCTP [29]. CDV-terminated primers could be extended at the next addition step, but these CDV+1 reaction products are not good substrates for further synthesis. While CDV can be excised from the primer 3´ terminus by exonuclease of vaccinia virus polymerase, DNAs which have CDV as the penultimate 3´ residue were found to be completely resistant to exonuclease cleavage [29]. In addition, and perhaps more importantly, when CDV is present in the template strand, the vaccinia DNA polymerase is not able to bridge the CDV base, resulting in chain termination which prevents further rounds of replication; similar results were noted when HPMPA was incorporated into the template strand [30]. Interestingly, HPMPA, the adenine analog of HPMPC, inhibits exclusively by the latter mechanism. Thus, there are several important mechanisms by which CDV and HPMPA inhibit vaccinia virus replication.

7. Early Studies of the Pharmacology and Toxicology of HDP-CDV in Mice

Equimolar doses of 14C-labeled CDV (5.6 mg/kg intraperitoneal) and HDP-CDV (10 mg/kg oral or intraperitoneal) were administered to mice [31]. After oral administration, HDP-CDV and metabolites in plasma reached their highest level, 2.34 μM, at three hours while intraperitoneal CDV showed a Cmax of 0.84 μM at one hour. Comparison of the oral and parenteral areas under curve (AUC) indicated that the relative oral bioavailability of HDP-CDV was 88% [31]. The oral bioavailability of CDV in rats has been reported to be less than 3%. HDP-CDV persists in plasma following absorption in mice with a T½ of 14.9 hours and is converted to CDV and metabolites in the tissues [31]. HDP-CDV is stable in plasma for several days at 37 °C and the plasma CDV noted after administration of HDP-CDV is a result of tissue metabolism.

The tissue distribution of CDV, HDP-CDV and metabolites was determined using 14C-labeled drugs and the Cmax and area under curve (AUC0-72hr) of drug and metabolites was calculated (Table 2). Several notable trends were apparent. The Cmax for intraperitoneal CDV in kidney was 180 nanomoles/gm, 30-times that observed for oral HDP-CDV. When CDV is given intraperitoneally, most of the radioactive CDV appeared in the kidney and very little CDV was noted in brain, heart, liver, lung and spleen. In contrast, oral HDP-CDV delivered large amounts of the drug and metabolites to liver and and greater exposures in other tissues including brain. In kidney, HDP-CDV AUC was only 19% of that observed with parenteral CDV, suggesting that the high kidney Cmax and AUC noted with parenteral CDV is responsible for its nephrotoxicity [31].

Early oral toxicity studies with HDP-CDV showed that single doses of 100 mg/kg could be used safely [32]. However, significant weight loss and some mortality were noted at doses of 30 mg/kg/day for 7 to 14 days which was apparently due to gastrointestinal toxicity. No kidney or liver toxic effects were apparent (Hostetler, unpublished observations, 2002). We were able to use 1 to 10 mg/kg/day doses of HDP-CDV for up to 21 days in various animal models of viral disease.

Table 2.

Comparison of areas under curve with oral HDP-[2-14C]-CDV and intraperitoneal [2-14C]-CDV in mouse tissues.

Table 2.

Comparison of areas under curve with oral HDP-[2-14C]-CDV and intraperitoneal [2-14C]-CDV in mouse tissues.

| AUC0-72hr | AUC Ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue | CDV | HDP-CDV | H/C |

| Brain | 0.87 | 3.96 | 4.6 |

| Heart | 3.46 | 14.26 | 4.1 |

| Liver | 39.6 | 1366.0 | 34.5 |

| Lung | 6.27 | 49.9 | 8.0 |

| Kidney | 1093.0 | 203 | 0.19 |

| Spleen | 9.92 | 53.2 | 5.4 |

Data are nmol/gm.hrs after a single oral dose of 10 mg/kg HDP-[2-14C]-CDV or a molar equivalent intraperitoneal dose of [2-14C]-CDV (5.6 mg/kg). Ratio column abbreviation: H = HDP-CDV, C = CDV. Adapted from Reference [31].

9. Current Status of Development of HDP-CDV (CMX001)

CMX001 is under consideration as an agent for inclusion in the Strategic National Stockpile for emergency use in the event of a release of variola or for complications of smallpox vaccination. In addition to its antiviral activity against the orthopoxviruses, HDP-CDV has been shown to be active as an antiviral against all double stranded DNA (dsDNA) virus infections including human CMV [39]; HSV-1, HSV-2 and EBV [40], various strains of adenovirus [41], BK virus [42], orf [43], JC virus and human papilloma virus [44]. Currently, CMX001 has completed Phase I clinical trials in normal volunteers and Phase II trials are ongoing in CMV infections in stem cell transplant patients (NCT00942305) and BK virus infection in kidney transplant patients (NCT00793598). In addition, CMX001 has been used successfully in a number of emergency IND (E-IND) applications in patients having infections with CMV, HSV, adenovirus, BK virus and JC virus infections sponsored by Chimerix Inc., the licensee. Finally, an expanded access trial entitled “A Multicenter, Open-label Study of CMX001 Treatment of Serious Diseases or Conditions Caused by dsDNA Viruses” is also open (NCT01143181).

10. Conclusions

HDP-CDV is a novel ether lipid antiviral which is orally active and lacks the nephrotoxicity of CDV itself. Increased oral bioavailability and increased cellular uptake, facilitated by the lipid portion of the molecule, is responsible for the improved activity profile. It is a highly effective agent against a variety of orthopoxvirus infections in animals including vaccinia, cowpox, rabbitpox and ectromelia. Its activity was recently demonstrated in disseminated vaccinia infection in man after HDP-CDV (CMX001) was added to a multiple drug regimen. In addition to the activity against orthopoxviruses, HDP-CDV (CMX001) is active against all dsDNA viruses including CMV, HSV-1, HSV-2, EBV, adenovirus, BK virus, orf, JC, and human papilloma viruses, and is in clinical development as a treatment for human infections with these viruses.

Acknowledgements

The research was supported in part by NIH grants AI074057, AI071803, EY07366 and EY018599. Hostetler is a consultant to Chimerix Inc. and the terms of this relationship have been reviewed and approved by the University of California, San Diego, in accordance with their conflict of interest policies.

References and Notes

- World Health Organization. The Global Eradication of Smallpox: Final Report of the Global Commission for the Certification of Smallpox Eradication; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1980.

- Henderson, D.A. Bioterrorism as a public health threat. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 1998, 4, 488–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, D.A.; Inglesby, T.V.; Bartlett, J.G.; Ascher, M.S.; Eitzen, E.; Jahrling, P.B.; Hauer, J.; Layton, M.; McDade, J.; Osterholm, M.T.; O’Toole, T.; Parker, G.; Perl, T.; Russell, P.K.; Tonat, K. Smallpox as a biological weapon:medical and public health management. JAMA 1999, 281, 2127–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbins, S.J.; Jackson, R.J.; Fenner, F.; Beaton, S.; Medveczky, J.; Ramshaw, I.A.; Ramsay, A.J. Expression of mouse interleukin-4 by a recombinant ectromelia virus suppresses cytolytic lymphocyte responses and overcomes genetic resistance to mousepox. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 1205–1210. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, T. Smallpox pill promising: New drug could thwart smallpox outbreaks. Nature News. 20 March 2002. [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, E.; Sakuma, T.; Baba, M.; Pauwels, R.; Balzarini, J.; Rosenberg, I.; Holý, A. Antiviral activity of phosphonylmethoxyalkyl derivatives of purine and pyrimidines. Antivir. Res. 1987, 8, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snoeck, R.; Sakuma, T.; De Clercq, E.; Rosenberg, I.; Holy, A. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1988, 32, 1839–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neyts, J.; De Clercq, E. Efficacy of (S)-1-(3-hydroxy-2-phosphonylmethoxypropyl)cytosine for the treatment of lethal vaccinia virus infections in severe combined immune deficiency (SCID) mice. J. Med. Virol. 1993, 41, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, M.; Martinez, M.; Smee, D.F.; Kefauver, D.; Thompson, E.; Huggins, J.W. Cidofovir protects mice against lethal aerosol or intranasal cowpox virus challenge. J. Infect. Dis. 2000, 181, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smee, D.F.; Bailey, K.W.; Wong, M.H.; Sidwell, R.W. Intranasal treatment of cowpox virus respiratory infections in mice with cidofovir. Antivir. Res. 2000, 47, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, M.; Martinez, M.; Kefauver, D.; West, M.; Roy, C. Treatment of aerosolized cowpox virus infection in mice with aerosolized cidofovir. Antivir. Res. 2002, 54, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korba, B.A.; Xie, H.; Wright, K.N.; Hornbuckle, W.E.; Gerin, J.L.; Tennant, B.C.; Hostetler, K.Y. Liver-targeted antiviral nucleosides: Enhanced antiviral activity of phosphatidyl-dideoxyguanosine versus dideoxyguanosine in woodchuck hepatitis virus infection in vivo. Hepatology 1996, 23, 958–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shackleford, D.M.; Porter, C.J.H.; Charman, W.N. Lymphatic absorption of orally administered prodrugs. In Prodrugs: Challenges and Rewards; Stella, V.J., Borchardt, R.T., Hageman, M.J., Oliyai, R., Maag, H., Tilley, J.W., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007; Volume 5, pp. 653–682. [Google Scholar]

- Scow, R.O.; Stein, Y.; Stein, O. Incorporation of dietary lecithin and lysolecithin into lymph chylomicrons in the rat. J. Biol. Chem. 1967, 242, 4919–4924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, A.; Borgström, B. Absorption and metabolism of lecithin and lysolecithin by intestinal slices. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1967, 137, 240–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hantz, O.; Allaudeen, H.S.; Ooka, T.; De Clerck, E.; Trepo, C. Inhibition of human and woodchuck hepatitis virus DNA polymerase by the triphosphates of acyclovir, l-(2’-deoxy-2’-fluoro-P-n-arabinofuranosyl)-5-iodocytosine and E-5-(2-bromovinyl)-2´-deoxyuridine. Antivir. Res. 1984, 4, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berk, L.; Schalm, S.W.; de Man, R.A.; Heytink, R.A.; Berthelot, P.; Brechot, C.; Boboc, B.; Degos, F.; Marcellin, P.; Benhamou, Je.P.; Hess, G.; Rosso, S.; zum Btischenfelde, K-H.M.; Chamuleau, R.A.F.M.; Jansen, P.L.M.; Reesink, H.W.; Meyer, B.; Beglinger, C.; Staider, G.A.; Den Ouden-Muller, J.W.; De Jong, M. Failure of acyclovir to enhance the antiviral effect of a lymphoblastoid interferon on HBe-seroconversion in chronic hepatitis B. A multi-centre randomized controlled trial. J. Hepatol. 1992, 14, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostetler, K.Y.; Beadle, J.R.; Kini, G.D.; Gardner, M.F.; Wright, K.N.; Wu, T.H.; Korba, B.A. Enhanced oral absorption and antiviral activity of 1-O-octadecyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-acyclovir and related compounds in hepatitis B virus infection, in vitro. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1997, 53, 1815–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostetler, K.Y.; Beadle, J.R.; Hornbuckle, W.E.; Bellezza, C.A.; Tochkov, I.A.; Cote, P.J.; Gerin, J.L.; Korba, B.E.; Tennant, B.C. Antiviral activities of oral 1-O-hexadecylpropanediol-3-phospho-acyclovir and acyclovir in woodchucks with chronic woodchuck hepatitis virus infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 1964–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beadle, J.R.; Kini, G.D.; Aldern, K.A.; Gardner, M.F.; Wright, K.N.; Rybak, R.J.; Kern, E.R.; Hostetler, K.Y. Synthesis and antiviral evaluation of 1-O-hexadecylpropanediol-3-P-acyclovir: Efficacy against HSV-1 infection in mice. Nucleos. Nucleot. Nucleic Acids 2000, 19, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostetler, K.Y.; Rybak, R.J.; Beadle, J.R.; Gardner, M.F.; Aldern, K.A.; Wright, K.N.; Kern, E.R. In vitro and in vivo activity of 1-O-hexadecylpropanediol-3-phospho-ganciclovir and 1-O-hexadecyl-propanediol-3-phospho-penciclovir in cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus infections. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 2001, 12, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cundy, K.C. Clinical pharmacokinetics of the antiviral nucleotide analogues cidofovir and adefovir. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1999, 36, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beadle, J.R. Synthesis of cidofovir and (S)-HPMPA ether lipid prodrugs. Curr. Protoc. Nucleic Acid Chem. 2007. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitsunobu, O. The use of diethyl azodicarboxylate and triphenylphosphine in synthesis and transformation of natural products. Synthesis 1981, January, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beadle, J.R.; Wan, W.B.; Ciesla, S.L.; Keith, K.A.; Hartline, C.; Kern, E.R.; Hostetler, K.Y. Synthesis and antiviral evaluation of alkoxyalkyl derivatives of 9-(S)-(3-hydroxy-2-phosphono-methoxypropyl)-adenine against cytomegalovirus and orthopoxviruses. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 2010–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huggins, J.W.; Baker, R.O.; Beadle, J.R.; Hostetler, K.Y. Orally active ether lipid prodrugs of cidofovir for the treatment of smallpox. Antivir. Res. 2002, 53, 104. [Google Scholar]

- Kern, E.R.; Hartline, C.; Harden, E.; Keith, K.; Rodriguez, N.; Beadle, J.R.; Hostetler, K.Y. Enhanced inhibition of orthopoxvirus replication in vitro by alkoxyalkyl esters of cidofovir and cyclic cidofovir. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 991–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldern, K.A.; Ciesla, S.L.; Winegarden, K.L; Hostetler, K.Y. The increased antiviral activity of 1-O-hexadecyloxypropyl-cidofovir in MRC-5 human lung fibroblasts is explained by unique cellular uptake and metabolism. Mol. Pharmacol. 2003, 63, 678–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magee, W.C.; Hostetler, K.Y.; Evans, D.H. Mechanism of inhibition of vaccinia virus DNA polymerase by cidofovir diphosphate. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 3153–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magee, W.C.; Aldern, K.A.; Hostetler, K.Y.; Evans, D.H. Cidofovir and (S)-9-[3-hydroxy-(2-phosphonomethoxy)propyl]adenine are highly effective inhibitors of vaccinia virus DNA polymerase when incorporated into the template strand. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciesla, S.L.; Trahan, J.; Winegarden, K.L.; Aldern, K.A.; Painter, G.R.; Hostetler, K.Y. Esterification of cidofovir with alkoxyalkanols increases oral bioavailability and diminishes drug accumulation in kidney. Antivir. Res. 2003, 59, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smee, D.F.; Wong, M.-H.; Bailey, K.W.; Beadle, J.R.; Hostetler, K.Y.; Sidwell, R.W. Effects of highly active antiviral substances on lethal vaccinia virus (IDH strain) respiratory infections in mice. Int. J. Antimicrobial Agents. 2004, 23, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucker, E.M.; Baker, R.O.; Beadle, J.R.; Shamblin, J.; Kefauver, D.; Zwiers, S.H.; Martinez, M.; Ciesla, S.; Trahan, J.; Hostetler, K.Y.; Huggins, J.W. Orally bioavailable alkoxyalkyl esters of cidofovir: In vitro and in vivo efficacy against orthopox viruses. In Proceedings of 16th International Conference on Antiviral Research, Savannah, GA, USA, 27 April–1 May 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Buller, R.M.; Owens, G.; Schriewer, J.; Melman, L.; Beadle, J.R.; Hostetler, K.Y. Efficacy of oral active ether lipid analogs of cidofovir in a lethal mousepox model. Virology 2004, 318, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quenelle, D.C.; Collins, D.J.; Hostetler, K.Y.; Beadle, J.R.; Wan, W.B.; Kern, E.R. Oral treatment of cowpox and vaccinia infections in mice with ether lipid esters of cidofovir. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, M.M.; Rice, A.D.; Moyer, R.W. Rabbitpox virus and vaccinia virus infection of rabbits as a model for human smallpox. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 11084–11095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.; Touchette, E.; Oberle, C.; Almond, M.; Robertson, A.; Trost, L.C.; Lampert, B.; Painter, G.; Buller, R.M. Efficacy of therapeutic intervention with an oral ether-lipid analogue of cidofovir (CMX001) in a lethal mousepox model. Antivir. Res. 2008, 77, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Progressive Vaccinia in a Military Smallpox Vaccinee—United States 2009. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm58e0519a1.htm (accessed on 14 September 2010).

- Beadle, J.R.; Rodriquez, N.; Aldern, K.A.; Hartline, C.; Harden, E.; Kern, E.R.; Hostetler, K.Y. Alkoxyalkyl esters of cidofovir and cyclic cidofovir exhibit multiple log enhancement of antiviral activity against cytomegalovirus and herpesvirus replication, in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 2381–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams-Aziz, S.L.; Hartline, C.B.; Harden, E.A.; Daily, S.M.; Prichard, M.N.; Kushner, N.L.; Beadle, J.R.; Wan, W.B.; Hostetler, K.Y.; Kern, E.R. Comparative activity of lipid esters of cidofovir and cyclic cidofovir against replication of herpesviruses in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 3724–3733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartline, C.B.; Gustin, K.M.; Wan, W.B.; Ciesla, S.L.; Beadle, J.R.; Hostetler, K.Y.; Kern, E.R. Activity of ether lipid ester prodrugs of acyclic nucleoside phosphonates against adenovirus replication in vitro. J. Infect. Dis. 2005, 191, 396–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randhawa, P.; Farasati, N.A.; Shapiro, R.; Hostetler, K.Y. Ether lipid derivatives of cidofovir inhibit polyomavirus BK replication in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 1564–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Pozzo, F.; Andrei, G.; Lebeau, I.; Beadle, J.R.; Hostetler, K.Y.; De Clercq, E.; Snoeck, R. In vitro evaluation of the anti-orf virus activity of alkoxyalkyl esters of CDV, cCDV and (S)-HPMPA. Antivir. Res. 2007, 75, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanier, R.; Chimerix Inc., Durham, NC, USA. Personal communication, 2010.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2010 by the authors. licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).