Abstract

In 2021, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, coronavirus research spiked, with over 83,000 original research articles related to the word “coronavirus” added to the online resource PubMed. Just 2 years later, in 2023, only 30,900 original research articles related to the word “coronavirus” were added. While, irrefutably, the funding of coronavirus research drastically decreased, a possible explanation for the decrease in interest in coronavirus research is that projects on SARS-CoV-2, the causative agent of COVID-19, halted due to the challenge of establishing a good cellular or animal model system. Most laboratories do not have the capabilities to culture SARS-CoV-2 ‘in house’ as this requires a Biosafety Level (BSL) 3 laboratory. Until recently, BSL 2 laboratory research on endemic coronaviruses was arduous due to the low cytopathic effect in isolated cell culture infection models and the lack of means to quantify viral loads. The purpose of this review article is to compare the human coronaviruses and provide an assessment of the latest techniques that use the endemic coronaviruses—HCoV-229E, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-NL63, and HCoV-HKU1—as lower-biosafety-risk models for the more pathogenic coronaviruses—SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV.

1. Introduction

Coronaviruses are zoonotic pathogens, with many having the potential to infect humans and cause severe disease, posing a concerning, continual global threat to humanity [1,2]. In recent years, much attention has been given to human coronaviruses; however, this was not the case in the years immediately following their discovery. The first two human endemic seasonal common cold coronaviruses, HCoV-229E and HCoV-OC43, were identified in the 1960s and determined to be distinct from each other when the serologic antibodies of an individual infected with one coronavirus did not react with the spike protein of the other [3,4,5]. Before the initial outbreak of a mysterious and fatal disease in China in 2003—severe acute respiratory syndrome, now known to be caused by a human coronavirus, SARS-CoV [6,7,8]—coronaviruses were thought to be inconsequential and were only associated with the common cold and upper respiratory illness in children [3,4]. Before SARS-CoV emerged, little progress had been made in understanding the epidemiology of human endemic coronaviruses, and no attempts had been made to develop a vaccine or therapeutic options [9].

The outbreak of SARS-CoV heightened scientific interest in coronaviruses, leading to the discovery of two additional endemic coronaviruses, namely, HCoV-HKU1 and HCoV-NL63 [10,11,12,13]. However, challenges in culturing endemic coronaviruses in isolated cell lines and a lack of non-cytopathic viral quantification methods led to research stagnation regarding these coronaviruses [14]. The 2012 outbreak of what is now known as the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), just 10 years after the SARS-CoV outbreak, raised concerns among scientists about the potential of coronaviruses to jump species and spread among the human population rapidly [15,16]. Less than a decade later, the world came to a standstill with the COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 in 2019 [17,18].

The scientific community made significant advances during the pandemic, developing and employing novel RNA-based vaccines, antibodies, and protease-targeting antivirals against SARS-CoV-2 [19,20,21,22]. These efforts significantly reduced the impact of COVID-19, although the impact of the pandemic was considerable. With these resources now available, researchers must prepare for the ever-evolving variants of SARS-CoV-2 and the possibility of novel coronaviruses expanding to the human population from animal carriers.

One research strategy that has gained popularity in recent years is using less pathogenic endemic coronaviruses, as safer and more approachable alternatives, to discover antivirals and understand coronavirus biology [14,23,24,25]. In this review, we compare human endemic coronaviruses to their more pathogenic counterparts and outline recent advances in the culturing of endemic coronaviruses (HCoV-229E, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-NL63, and HCoV-HKU1) as safer replacements for the more pathogenic coronaviruses (SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2) used in discovery studies. The increased attention given to endemic coronaviruses is well deserved. It will likely lead to breakthroughs in the development of antivirals, insights into host and viral biology, and a better understanding of how and when viruses become endemic—an essential question that will inform current policies and the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 worldwide.

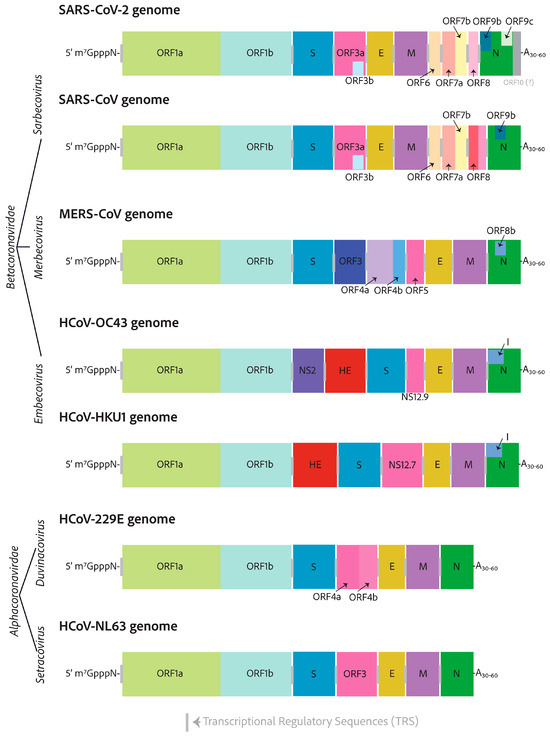

3. Genomes and Basic Genetic Differences

Human coronaviruses are relatively distantly related and are closest in terms of relation to zoonotic ancestors [57,58]. With time, there have been evolutionary adaptations enabling them to infect new host species. The remaining similarities between human coronaviruses can teach us about the components that are most important to getting the job done [59]. All coronavirus genomes are 5′-capped and have a poly-A tail on their 3′ end [26]. They have very similar 5′-ends, with two open reading frames separated by a ribosome frameshift secondary structure. The open reading frames on either side are called ORF1a and ORF1b [26]. Coronavirus 3′-ends are radically different in comparison, but they all encode the essential structural components of the virion particles—the S, E, M, and N proteins—and several diverging accessory factors, as shown in Figure 2 [60].

The accessory factors are the least well-studied coronavirus proteins. The sarbecovirus 3′ end regions are the most complex, with 10 to 13 potential coding sequences. On the other end of the spectrum, the HCoV-229E and HCoV-NL63 alphacoronaviruses only encode the necessary structural genes—S, E, M, and N—as well as a viroporin-encoding gene, indexed as ORF3 for HCoV-229E, which is broken into two open reading frames for HCoV-NL63, ORF4a, and ORF4b [61]. All HCoVs encode a similar viroporin protein, whose gene is positioned between the S and E in the genomes, with many differing pseudonyms, all shown in pink in Figure 2 [61].

The HCoV-OC43 NS12.9 viroporin was knocked out in a recombinant mutant virus and found not to be essential, but it reduced viral titer 10-fold. It was thus suggested to be important for proper viral fitness and production [61]. NS12.9 was shown to have ion channel activity. This was confirmed with electrophysiology experiments with exogenous expression in yeast and Xenopus oocytes [61]. Viroporins from other enterovirus and influenza A, EV71-2B, and IAV-M2, respectively, could reverse the phenotype observed for the loss of NS12.9 in HCoV-OC43 infection [61]. Additionally, the SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a, HCoV-229E ORF4a, and HCoV-NL63 ORF3 were also able to complement the loss of NS12.9 in HCoV-OC43 infection [61]. Other similar accessory factors between distantly related betacoronaviruses include the I protein, which is situated in the middle of the nucleocapsid open reading frame. For SARS-CoV-2, the I protein is annotated as ORF9b, which has been shown to target the mitochondrial outer membrane protein Tom70 to switch off the mitochondrially regulated apoptosis responses and to target mitochondrial innate immune responses led by the release of mitochondrial DNA or the activation of the mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein, MAV [62]. MERS-CoV ORF8b was also shown to inhibit the innate immune response type I interferon expression by inhibiting the interaction of the IKKε kinase with HSP70, which is essential for the kinase activation of the interferon regulatory factor 3 [63].

4. Cell Entry

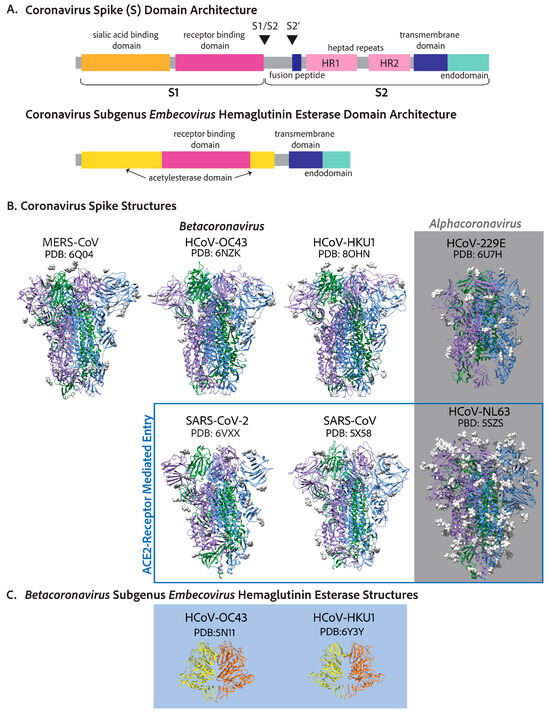

The coronavirus spike protein (S) forms trimer conformations that jet out from the virion membrane by approximately 20 nm [26]. While the initial binding to the corresponding adhesion factor determines the specificity of a cell in terms of being susceptible to infection, this is only the beginning of its function as a viral fusion protein [30,31]. After attachment to a susceptible cell, the spike is cleaved in highly conserved sites despite the receptor binding sequences of the protein being radically different in terms of amino acid sequences [31]. The cleavage of the coronavirus S protein leads to a conformational change akin to a loaded spring that launches membrane fusion between the CoV envelope and the cell plasma membrane [30]. The spike can be divided into two main domains—the S1 domain, responsible for engaging with host cell receptors, and the S2 domain, which fuses membranes—as shown in Figure 3A [30]. Cleavage leading to the separation of S1 and S2 can occur in either the virus-producing cell directly after translation or once they reach the cell surface of the next target [30]. SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV S proteins are cleaved at the S1/S2 site in the virus-producing cell by a proprotein convertase like furin so that S1 and S2 domains of the spike of a mature SARS-CoV-2 or MERS-CoV virion are noncovalently bound subunits [30,35]. S1 is responsible for engaging the adhesion factor, and S2 anchors the virion to the membrane and facilitates membrane fusion [30,31]. S1 can engage carbohydrates such as sialic acids in its N-terminal domain and the protein receptor in its C-terminal domain [31]. The role of both carbohydrate and protein receptors is still being elucidated. However, there is evidence that both are important [64]. S is cleaved a second time at the S2’ location which is mediated by TMPRSS2 at the cell surface or by a similar protease on the endosome membrane like cathepsin L [30,31]. This second cleavage launches the spring, leading to membrane fusion and the release of the genome into the cytosol [38]. In contrast to SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV S protein is cleaved at both sites by the target cell proteases [65,66]. In either case, membrane fusion depends on the target cell proteases [30]. Figure 3B shows the solved crystal or cryo-EM structures of each human-infecting coronavirus spike protein, each decorated with glycosides, as well as the solved structures of the two human-infecting embecovirus hemagglutinin esterase proteins.

Figure 3.

Coronavirus spike proteins have similar conserved domain architectures. (A) The betacoronavirus spike is designed to be cleaved at two sites, leading to two functionally different subunits: S1, which includes the receptor binding domain, and S2, the cell–virion fusion domain. The N-terminal domain of S1 is shown to interact with carbohydrates like sialic acids, and the receptor binding domain is in the C-terminal half of S1 [31,64,67,68]. S2 includes the fusion peptide, which buries into the host cell membrane, leading to cell–virion fusion, two heptad repeats, a transmembrane region, and an endodomain [30,38]. The endodomain includes ER-export (COPII), ER-retrieval peptides (COPI), and a membrane protein interaction site. (B) The spike crystal structures or cryo-EM structures of each human coronavirus. SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and HCoV-NL63 spike proteins all attach to ACE2 [69]. MERS-CoV interacts with DPP4 [67]. HCoV-229E interacts with APN [70]. Historically, HCoV-HKU1 was shown to use sialic acids as a functional receptor to trigger conformational opening to allow for S2’ cleavage and fusion [71]; however, it was recently shown that the HKU1 spike uses TMPRSS2 as a functional receptor with important sialic acid attachments [72]. HCoV-OC43 has only been shown to attach to sialic acids [73]. (C) The hemagglutinin esterase structures of the embecoviruses: HCoV-OC43 [74] and HCoV-HKU1 [75].

Adhesion factors for human coronaviruses follow some interesting trends. The angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is the adhesion factor of SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2, and, through completely differential evolutionary means, HCoV-NL63 [36,76,77,78,79]. Thus, HCoV-NL63 is an important, safer alternative to SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 in cell entry mechanism studies and the discovery of cell entry inhibition antivirals [78]. The functional receptor for MERS-CoV is the surface metallopeptidase, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) [80]. HCoV-229E utilizes aminopeptidase N (APN) as its functional receptor [70]. ACE2, DPP4, and APN are all members of the MA metallopeptidase family and have some similarity in tissue expression and structure (Table 1). More evidence is needed to ascertain the advantages of utilizing metallopeptidase for cell adhesion, as typically the spike is not cleaved via the attachment receptor [72,80]. HCoV-OC43 and HCoV-HKU1 spike proteins recognize the attachment of O-acetylated sialic acids to cell surface glycoproteins and glycolipids, which have been shown to allow cell entry. Numerous reports show that SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2, and MERS-CoV S proteins interact with sialic acids, although typically, the focus is the protein receptor that determines cell susceptibility [64,67,68,73,81,82].

While it has long been accepted that embecoviruses HCoV-OC43 and HCoV-229E attach to and recognize 9-O-acetylated sialic acids in receptor-mediated entry [73], it is not clear whether there are specific sialic-decorated proteins or lipids necessary for entry [72]. Saunders et al. recently showed that TMPRSS2 is a functional adhesion receptor for HCoV-HKU1 [72]. Using current methods, HCoV-HKU1 does not culture well in isolated cell culture models, making infection studies more difficult and HCoV-HKU1 the least studied coronavirus [72]. Because of this difficulty, Saunders et al. exogenously expressed HCoV-HKU1 spike in HEK293T cells that do not express TMPRSS2 [72]. Only when there is co-expression of TMPRSS2 is there cell–cell fusion. For the SARS-CoV-2 spike expressed in HEK293T cells, only the expression of ACE2 leads to cell–cell fusion and not TMPRSS2 expression [72]. They tested a full panel of other cell membrane proteases, including APN, DPP2, ACE2, TMPRSS4, and TMPRSS11D, but only TMPRSS2 allows cell–cell fusion for HCoV-HKU1 spike [72]. They also expressed TMPRSS2 protease-inactive mutants as well as wild-type in HEK293T cells and determined the entry of a lentiviral pseudovirus decorated with the HCoV-HKU1 spike, all of which still led to the cell entry of the pseudovirus likely via endocytosis means [72]. However, HEK293T without TMPRSS2 did not allow the entry of the HCoV-HKU1 pseudovirus, suggesting that TMPRSS2 is acting as a cell adhesion factor, not only as a spike cleavage protease, in the case of HCoV-HKU1 [72]. Intriguingly, Vero-E6 cells that express TMPRSS2 are not susceptible to infection with HCoV-HKU1 pseudovirus, indicating other cell entry factors such as protein sialyation or glycosylation must be necessary for proper HCoV-HKU1 entry [72]. To test this, Saunders et al. treated V20S cells that express TMPRSS2 with Neuraminidase to enzymatically remove protein sialic acids, specifically Lectin SNA and Siglec-E, without interfering with the cell surface levels of TMPRSS2 and found that, indeed, sialic acids were necessary to trigger HCoV-HKU1 entry [72].

The conclusions of this paper only focus on HCoV-HKU1, the least studied coronavirus. However, the implication that TMPRSS2 can be a cell adhesion factor outside its role in spike cleavage should be investigated for other coronaviruses, specifically HCoV-OC43, the coronavirus most closely related to HCoV-HKU1. There may be evidence that factors other than sialic acids are important for HCoV-OC43 receptor-mediated entry. The sialic acid binding domain of the HCoV-OC43 spike protein is in the S1 N-terminal domain; however, Chuyun Wang et al. found two S1 C-terminal domain-targeting neutralizing antibodies that inhibit infection but not sialic acid binding [83]. Nevertheless, the finding by Saunders et al., that only TMPRSS2 decorated with the correct sialic acids can allow the entry of the HCoV-HKU1 pseudovirus, highlights the potentially more important role of sialic acids in coronavirus entry, which should be investigated [72]. While protein receptors like ACE2 and adhesion factors like sialic acids receive a lot of attention, the cell proteases that induce spike cleavage can be equally important in terms of cell entry [84].

Table 1.

Human coronaviruses and their primary cell tropism within the human body.

Table 1.

Human coronaviruses and their primary cell tropism within the human body.

| Virus | Host of Origin a | Intermediary Host b | Primary Cell Attachment Receptor/Factors c | Human Cell Tropism/Attachment Receptor Tissue Expression d | Susceptible Cell Lines e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 | Bat | Pangolin (?) | Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE2) | Correlates well with ACE2 expression: ciliated epithelial cells as well as vascular endothelial cells of the lung, trachea, intestine, skin and sweat glands, kidney, brain and heart. | Vero E6/76, Calcu-3, Caco-2 |

| SARS-CoV | Bat | Palm Civet | Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE2) | Correlates well with ACE2 expression: ciliated epithelial cells as well as vascular endothelial cells of the lung, trachea, intestine, skin and sweat glands, kidney, brain and heart. | Vero E6, Calu-3 cells |

| MERS-CoV | Bat | Camel | Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DDP4 or CD26) | Correlates well with DPP4 expression: expression in parathyroid gland, intestine, placenta, prostate, seminal vesicle, salivary gland and liver. Only low and medium expression in the nasopharynx and bronchus, respectively. | Huh-7 cells, Vero E6 |

| HCoV-OC43 | Mice | Bovine | 9-O-acetylated sialic acids | 9-O-Ac were found in the adrenal gland, colon, cerebellum, gray matter, pancreas, prostate, salivary gland, and small intestine, which correlates well with expression of CASD1 and SIAE, the O-acetyltransferase and O-acetylesterase, respectively. Both of these have low and medium expression in the nasopharynx and bronchus, respectively. | Vero E6, MRC-5, Mv1Lu, RD, Huh7, modified Vero E6 that stably overexpress TMPRSS2 |

| HCoV-HKU1 | Rodent | Mice | TMPRSS2, 9-O-acetylated sialic acids | TMPRSS2 localizes to the lung, gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, kidney, parathyroid gland. 9-O-Ac were found in the adrenal gland, colon, cerebellum, gray matter, pancreas, prostate, salivary gland, and small intestine, which correlates well with expression of CASD1 and SIAE, the O-acetyltransferase and O-acetylesterase, respectively. Both of these have low and medium expression in the nasopharynx and bronchus, respectively. | Primary Lung Epithelial Cultures, does not take well to isolated cell lines. |

| HCoV-NL63 | Bat | Palm Civet | Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE2) | Correlates well with ACE2 expression: ciliated epithelial cells as well as vascular endothelial cells of the lung, trachea, intestine, skin and sweat glands, kidney, brain and heart. | Vero E6, MRC-5, LLC-MK2, Mv1Lu |

| HCoV-229E | Bat | Bat | Aminopeptidase N (APN) | APN is expressed on the surface of myeloid progenitors, monocytes, granulocytes, myeloid leukemia cells, and stem cells. It is highly expressed in the gastrointestinal tract, the liver, pancreas, and kidney. | MRC-5, Huh7, Mv1Lu |

a The host species of origin of a coronavirus is the species that has an endemic infection with the most closely related coronavirus ancestors [57,58,85,86]. b Coronaviruses have mosaic genomes with spliced regions from different coronaviruses, some of which may be of differing host species. If this splicing is in the spike region, the coronavirus may be capable of expanding its host species range, leading to cross-species transmission to the human host [57,58]. There are controversial opinions on whether SARS-CoV-2 was spliced in the spike region and even whether it has pangolin coronavirus ancestors as indicated by a “?” [1,87]. The intermediary host showed evidence of coronavirus infection with closely related ancestors of the human coronavirus and may have allowed for genomic recombination or adaptations leading to the capability of spreading to the human host. c The primary cell attachment receptors for SARS-CoV-2 [76,88], SARS-CoV [79], MERS-CoV [80], HCoV-OC43 [73], HCoV-HKU1 [71,72], HCoV-NL63 [78], and HCoV-229E [70]. d The human cell tropism is largely determined by tissue expression of the protein receptors—ACE2 [89,90], DDP4 [89,90], 9-O-acetylated sialic acids [89,90,91,92,93], TMPRSS2 [89,90], and APN [89,90]. e The most appropriate cell lines for culturing are those that are both susceptible to infection and produce an observable cytopathic effect that can be utilized to quantify viral titers. The more pathogenic coronaviruses have been known to produce drastic cytopathic effects in various cell lines—SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV [79,94], and MERS-CoV [51,95]. For endemic coronaviruses that were initially cultured in organ cultures of many different cell types, finding an isolated cell culture that achieves an observable cytopathic effect has been a challenge [14,23,24,96]. An isolated cell culture model for HCoV-HKU1 has still not been found. As such, it is typically cultured in primary epithelial cultures [72].

5. Evolution and Host Tropism—Cell Receptors and Cell Tropism

Coronaviruses are zoonotic, and many are capable of infecting multiple host species. The most closely related ancestors to human coronaviruses are those that infect other mammalian host species [57,58]. Host tropism, or the span of host species susceptible to infection, is primarily decided by the tissue expression of the primary adhesion factor recognized by the spike’s receptor binding domain as shown in Table 1. Recent evidence suggests that cell surface proteases, endosomal proteases, and the S2 domain are also important determinants of host tropism [31]. Cross-species transmissions of coronaviruses occur frequently, as we have seen in the past 20 years with SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2 and will likely continue to see with human globalization and climate change impacts. What allows coronaviruses to expand their host range quickly? Genomic recombination may be one of the key drivers of host switching by coronaviruses, primarily when it occurs in the spike gene region [97]. The emergence of SARS-CoV as a human pathogen was likely a result of a recombination event, in which ancestral bat SARS-CoV-like viruses did not have the ability to recognize ACE2 and likely gained that ability through recombination on multiple occasions [97]. The bat pathogen able to infect humans had evidence of recombination with a palm civet coronavirus, making the palm civet the intermediary host species [57]. It has been shown that SARS-CoV-like bat viruses that do not have the ability to bind ACE2 are unable to infect the human host [98].

However, whether genomic recombination is necessary for a host-switching event is debatable. While all seven human coronaviruses have traces of genomic recombination shown by their mosaic-like genomes—the regions of different ancestral coronavirus sources stitched together—there is disagreement as to whether all human coronaviruses show evidence of that stitching in their spike gene, specifically for SARS-CoV-2 [97]. SARS-CoV-2’s most closely related ancestor is a bat coronavirus RaTG13, and some have suggested there is evidence of recombination with a pangolin coronavirus in the receptor binding domain of the spike [1,87]. Others argue that recombination was not a driving force in the spike region [99]. While pangolins may have acted as an intermediary host, some make the case that the most recent common ancestor of RaTG13 and SARS-CoV-2 evolved from closely related Sarbecoviruses in bats that had the ability to replicate in both pangolins and humans [87,99,100]. In this case, there was no recombination with a pangolin virus whatsoever. Indeed, the RaTG13 spike can also bind the ACE2 receptor, which it primarily utilizes in cell entry [99]. Thus, it may be the case that recombination was not a driving force in SARS-CoV-2 cross-species transmission, leading to the debate around whether the pangolin is an intermediary host.

Other hypotheses for how coronaviruses expand their host range include promiscuous receptor binding as well as infection and adaptation to intermediary hosts [97]. With the increased research efforts to understand and prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection, many noncanonical receptors have been identified for SARS-CoV-2, suggesting a potentially more receptor-independent cell entry mechanism. CD147 [101], Neuropilin-1 [102], AXL [103], GRP78 [104], TfR [105], and TMEM106B [106] have all been identified as noncanonical functional receptors for SARS-CoV-2 entry. While this receptor promiscuous cell entry has yet to be established as a means of host jumping, it is associated with the broad tissue tropism that presents with SARS-CoV-2 infection, which can often even be found in tissues with very low to no expression of ACE2 [107]. Broader tissue tropism has yet to be explored for endemic human coronaviruses.

Additionally, coronaviruses can quickly evolve and adapt to a new host, as we have seen with SARS-CoV-2’s rapid adaptation to the human host through beneficial mutations that arise randomly and are selected for by enhanced transmission and increased viral progeny, leading to variants that outcompete all others. This selection of beneficial mutations, leading to the rise of variants, is not only a trait of SARS-CoV-2. The molecular epidemiology of HCoV-OC43 suggests that different genotypes or variants evolved over time [108], albeit much slower than occurred with SARS-CoV-2. However, the initial stages of HCoV-OC43 infecting the human host may have resulted in a similar pace of mutational adaptation compared to SARS-CoV-2. Unfortunately, the molecular epidemiology of HCoV-OC43 may be lost to time. Historical records show there was a pandemic around the same time in which HCoV-OC43 first infected humans, as determined by molecular dating methods [57,58,109].

6. Pathogenicity

6.1. How Prevalent Are Endemic Coronaviruses?

Measuring the prevalence of endemic coronaviruses prior to the COVID-19 pandemic was complicated as mere common cold symptoms typically do not elicit a need to seek medical assistance, and thus many infections went undetected, leading to wide-ranging estimates of total endemic coronavirus prevalence from 5% to greater than 30%. Additionally, inherent seasonality and changes year to year in infection rates may have led to discrepancies between studies. Endemic coronaviruses have been studied in large cohort studies, such as in the Michigan Household Influenza Vaccine Evaluation (HIVE) study, which followed families with children who reported acute respiratory illness within the household from years 2010 to 2018 [110]. From 2010 to 2018, the HIVE cohort ranged from 895 to 1426 individuals. Of all acute respiratory illnesses reported, human endemic coronavirus tests were positive between 8.3% and 14.8% of the time, depending on the year, with HCoV-OC43 being the most prevalent overall, although in some years other coronaviruses were dominant [110]. Endemic coronavirus infections follow seasonality and peak every 2 years [110]. One explanation for this is that antibodies from the previous season can prevent symptoms of infection the following year [110].

The HIVE study followed already enrolled participants during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, in which 437 patients reported a total of 773 acute respiratory illnesses between March 2020 and June 2021 [111]. The incidence of acute respiratory illness during this period was 50% lower than in the previous pre-pandemic length of time from March 2016 to June 2017 [111]. In this pandemic-era study, rhinovirus infection was the most prevalent, followed by endemic coronaviruses, and HCoV-NL63 was the predominant coronaviral infection, seen in 4.2% of all samples tested [111]. There was even one case of co-infection with NL63 and SARS-CoV-2 [111]. The start of this study coincided with the early waves of the pandemic, with the implementation of public health restrictions such as school closure, masking requirements, and the cancellation of large crowd events like concerts. Results suggested that these measures also abated endemic coronavirus infection [112].

The National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System (NREVSS) followed the seasonality of endemic HCoVs from 2014 to 2021 [113,114]. The surveillance system collected viral testing results across the United States weekly from patient centers, including clinical, public health, and commercial laboratories [113,114]. Of all specimens submitted to the NREVSS, 3.6% were positive for any HCoV, and HCoV-OC43 was dominant, with 40.1% of all positive for an HCoV [113,114]. Shah et al. also reported on seasonality, suggesting that endemic HCoVs had seasonal onsets between October and November, peaking from January to February, with offsets in April to June [113]. The only year to deviate was 2020–2021, in which the endemic HCoV season was delayed by 11 weeks, likely due to public health measures taken to reduce the SARS-CoV-2 burden [113]. While this study is valuable for detecting seasonal onset and offset of endemic coronaviruses, it may be biased because only those who deem themselves ’sick enough’ will seek medical assistance and go through viral testing [113,114].

Wastewater studies may be a better approach with which to measure endemic coronavirus prevalence as there is no bias in terms of the severity of illness needed to report, and they would also account for asymptomatic cases where the virus may still be shed [115]. However, fewer data are attached, and no information is given about who is more likely to be infected or have more pathogenic disease, such as what age groups are affected [115,116]. Other information can supplement wastewater studies about the region, such as high tourism levels and population demographics, which should be considered when interpreting results [115,116]. Additionally, more studies are needed to test how long viruses ‘survive’ in wastewater to then be detected some number of days later [115,116]. Wastewater testing was a valuable resource in seeking to determine when SARS-CoV-2 was peaking in the past years of the COVID-19 pandemic; as a result, other respiratory viruses are now being surveilled with this method [115,116]. Bohem et al. tested wastewater RNA concentrations via RT-qPCR analysis of several respiratory viruses, including human influenza, metapneumovirus, parainfluenza, endemic coronavirus, respiratory syncytial virus, rhinovirus, and SARS-CoV-2, from a Californian wastewater treatment plant from February 2021 to June 2022 [116]. During this time, SARS-CoV-2 had the highest median viral RNA concentration found in wastewater [116]. Endemic coronaviruses had the second-highest median viral RNA concentration, above that of rhinovirus [116]. This wastewater study contrasts with the self-reported HIVE and NREVSS studies that show that rhinovirus is the most abundant [112,113,116]. Gathering information about endemic coronaviruses by both means is vital to understanding endemic coronavirus prevalence better.

6.2. What Kind of Disease Do Endemic Coronaviruses Cause?

The first observation of human coronavirus disease was in the 1960s, when healthy adults volunteered to be infected with HCoV-229E and HCoV-OC43 [3,117,118]. Both were shown to cause a common cold that, on average, cleared within one week [3,43]. Symptoms from infected adults showed that the alphacoronavirus, HCoV-229E, was typically mild compared to the betacoronavirus, HCoV-OC43 [3]. Nevertheless, these studies left out vulnerable populations, including children. More recent studies show that endemic coronavirus infection is more prevalent in children under the age of 5, with roughly 42% to 50% of 6–12-month-olds displaying antibodies from an HCoV-229E infection [119], and that number increases to 65% for 2.5–3.5-year-olds [120]. Other studies show a similar trend where endemic coronaviruses tend to be more severe in children than adults, likely because adults have built up neutralizing antibodies and T-cell responses [121,122]. HCoV-NL63 was first discovered in an infant with pneumonia due to endemic coronavirus infection [10,11,69]. Other possible complications in infants or children due to endemic coronavirus infection are croup, encephalitis, and bronchitis [3]. In addition to children, patients who are immunocompromised or are elderly can have more severe outcomes to endemic coronavirus infection [3,9,123]. HCoV-HKU1 was discovered in 2004 in an elderly Chinese man who presented with chronic obstructive airway disease [12]. In general, infection by an endemic coronavirus is not lethal or severe in adults without underlying disease or old age [3]. However, cases in infants, children, and those with underlying diseases can be more complicated.

Zoonotic coronaviruses are known to cause disease in the respiratory tract and central nervous system, as well as gastroenteritis [3]. While human coronaviruses can be detected in stool samples, as described in the wastewater studies in the earlier section, no HCoV-229E- or HCoV-OC43-infected volunteers presented gastrointestinal disease, suggesting that endemic coronaviruses may be shed through the gastrointestinal system without causing considerable disease [3,5]. Other studies reveal that there can be some gastrointestinal symptoms in cases of human endemic coronaviruses, specifically in children [124]. There has also been evidence of endemic HCoV infection of the central nervous system in mice models, and this has been found in human post-mortem brain samples [125,126,127]. Some argue that the effect of human endemic coronavirus on the central nervous system has been severely underestimated [128].

In contrast to endemic coronaviruses, SARS-CoV, the causative agent of severe acute respiratory syndrome, causes considerable pathology, even in healthy individuals [6,7,8,129]. The SARS-CoV epidemic, although brief, spread to 29 countries with a total of 8422 cases and 916 fatalities, roughly a 10% fatality rate [129]. The spread of SARS-CoV was controlled within 7 months of the first outbreak. SARS disease follows a two-phase, occasionally three-phase, illness in which the first phase is typically symptom-free, followed by the second phase of respiratory symptoms, fever, vomiting, and diarrhea [129]. Then, about 15% of adults will develop a third phase, in which there is acute respiratory distress [129]. Public health measures, including the quarantine of infected people and contact tracing, were integral in limiting the SARS-CoV epidemic [129].

The Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus, MERS-CoV, which initially became known in 2012, causes the most severe disease of any known coronavirus, with a mortality rate of 35% per the World Health Organization [130]. The transmission of MERS-CoV typically occurs with interaction with a dromedary camel; however, human-to-human transmission is possible and more likely to occur among those who provide health care to an infected individual [130]. Symptoms of MERS-CoV infection typically include a fever, cough, shortness of breath, and pneumonia [130]. Gastrointestinal symptoms have also been reported [130].

SARS-CoV-2 infection typically involves mild to moderate respiratory illness, and most people recover without specialized care [131]. However, some populations, like those with co-morbidities and seniors, are more likely to develop more severe disease and require medical intervention [131]. Symptoms usually begin 5–6 days after exposure and can last up to 14 days [131]. The most common symptoms are a fever, chills, and a sore throat. However, they may also include muscle aches, fatigue, a runny nose, headaches, dizziness, the loss of taste or smell, appetite loss, and gastrointestinal illnesses such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea [131]. Additionally, several patients who recover from COVID-19 disease develop chronic illness, which includes a wide range of symptoms that not present in the individual prior to SARS-CoV-2 infection, known as long COVID [131].

6.3. A Note on Endemicity

Endemic viruses are consistently maintained in a population and have predictable patterns [132]. For example, the flu peaks in winter, and the most prevalent strains are predicted from the previous year’s data to inform vaccine development [132]. Nonendemic viruses, on the other hand, have an unstable and unpredictable transmission with potential surges or disappearances over periods of time [132]. Despite its worldwide presence, SARS-CoV-2 has yet to reach an endemicity seen with the other HCoVs [132]. Endemicity is reached when there is a reduction in the overall virus transmission, and a pattern of infection emerges [132]. At this moment, SARS-CoV-2 population dynamics are unpredictable, unlike endemic viruses, and the threat of resurgence and variant transmission continues [132].

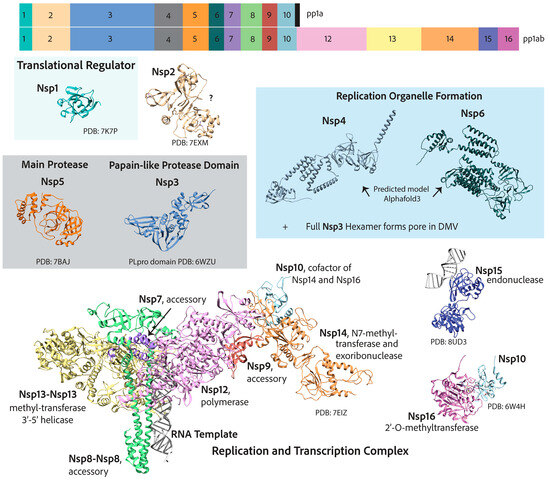

7. Replication and Transcription Proteins

Arguably, all viruses have complex methods to deal with their genetic material, considering that they most likely require host factors to replicate while conflictingly needing to hide that genetic material from invader detection systems of the host cell. Coronaviruses are no different. After the translation of the two 5′ open reading frames and subsequent self-proteolytic cleavage by the main protease, nsp5, and the Papain-like 3CL protease domain of nsp3, the 16 nonstructural proteins get to work with three main tasks outlined below: (A) the reorganization of cellular membranes to form replication organelles; (B) viral genome replication and transcription inside these replication organelles; (C) RNA-capping [26,45]. A detailed map of the two coronavirus 5′-encoded polypeptides and the nonstructural proteins is depicted in Figure 4. Endemic coronaviruses are organized similarly to the more pathogenic coronaviruses and have considerably similar nonstructural proteins. The similarity of each nonstructural protein from the seven human coronaviruses is depicted with heatmaps in Figure 5. The most highly conserved nsps are those distal to the 5′ end, such as nsp10, nsp12, nsp13, nsp14, and nsp16. Accordingly, due to this high degree of conservation in amino acid sequence and function, endemic coronaviruses are favorable model systems for studying these nonstructural proteins’ functions and discovering inhibitors that can be used as therapeutics. Furthermore, nonstructural proteins involved in genome replication and transcription may be better targets for resistance-refractory therapeutics than highly mutagenic spikes.

Figure 4.

A map of coronavirus 5′-end nonstructural genes that, once translated into two polypeptides (pp1a and pp1ab), are self-cleaved into 16 nonstructural proteins that are responsible for genome replication and transcription. The function of nsp2 is not completely resolved. Nsp11, not shown, encodes a 13 amino acid peptide whose function is unknown.

Figure 5.

Heatmaps of percent similarity between human coronavirus nonstructural protein amino acid sequences. NCBI reference genomes used for sequence analysis: SARS-CoV-2 (NC_045512.2), SARS-CoV (NC_004718), MERS-CoV (NC_019843.3), HCoV-OC43 (NC_006213.1), HCoV-HKU1 (NC_006577), HCoV-229E (NC_002645.1), and HCoV-NL63 (NC_005831.2).

7.1. Reorganization of Cellular Membranes to Form Replication Organelles

All mammalian-infecting positive-stranded RNA virus replication complexes can reorganize cellular membranes remarkably [133,134]. Different viruses tend to reorganize distinct specific organellar membranes to assemble their replication complexes. This has been shown for poliovirus [135,136], hepatitis c virus [137], norovirus [138], arteriviruses [139], and coronaviruses [51,52]. One of the earliest descriptions of coronavirus’ reorganization of organellar membranes to form replication organelles was of murine hepatitis virus (MHV), a mouse-infecting coronavirus [140,141]. These early papers hint at replication components being associated with double-membraned vesicles. These structures were characterized further in SARS-CoV-infected cells, showing that the replication complex components localize to DMVs that bud from the ER and Golgi membranes as seen by immunofluorescence and electron microscopy [142,143,144]. These ER–Golgi-associated vesicle structures where replication components localize are distinct from compartments that form new virion particles [51,143]. It was later shown that the transmembrane proteins nsp3, nsp4, and nsp6 could form these replication organelles when expressed in cells that were not infected [49]. These DMVs may protect viral genomic RNA during replication, which forms a double-stranded RNA intermediate that is easily recognized as foreign by the host cell Rig-I-like receptors [145]. Further, the compartmentalization of replication could enhance replication kinetics by increasing the concentration and availability of necessary viral and host factors [51].

Most recently, coronavirus DMVs were shown to not only house the replication complex but also to be the site of viral RNA synthesis by electron microscopy with radioactively labeled ribonucleotides for MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV, and infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) [51]. Interestingly, these replication organelles were shown to have pores formed by a hexamer of nsp3, which spans the double membrane [52]. Electron tomography of cryo-lamellae showed that the DMVs of MHV-infected cells have a membrane-spanning pore [52]. Using a GFP-tagged-nsp3 construct, the domain density in the electron tomography confirmed that nsp3 forms the pore complex [52]. Nsp3 has an N-terminal ubiquitin-like domain that binds single-stranded RNA (like the viral genome) [146] and the nucleocapsid [147]. There are still some great mysteries about these DMV replication organelles. How do nsp4, nsp6, and nsp3 form them? How does viral RNA enter? How do all the components of the replication complex enter, or is the complex formed inside?

7.2. Viral Genome Replication and Transcription Inside Double Membranous Organelles

The most complete structure of the coronavirus RTC consists of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), the helicase, the bifunctional exoribonuclease and N7-methyltransferase protein, as well as several essential accessory factors [148]. The RNA-dependent RNA polymerase catalytic subunit, nsp12, has the typical right-handed conformation of polymerases [46,149]. Nsp12 only displays polymerase activity for short RNA templates with an RNA primer. Nsp12 interacts with nsp7 and a dimer of nsp8, which stimulate its polymerase activity [46,149]. It has also been suggested that nsp7 and nsp8 act together as a primase [150]. However, some suggest they are merely processivity factors [151]. Nsp7 and nsp8 have RNA-binding capability themselves [151]. The RdRp works closest with the helicase, nsp13, an ATP-dependent 3′ to 5′ helicase that has two copies in cryo-EM structures of the complex [152]. The 3′ to 5′ helicase activity opposes that of the RdRp, which adds nucleotides to the 3′ end [152], a contradiction that is yet to be fully parsed out [152]. Nsp13 is also involved in RNA capping by acting as an RNA 5′triphosphatase (RTPase), hydrolyzing the 5′γ-phosphate end of the nascent RNA [152]. Intriguingly, both nsp12 and nsp13 were characterized as FeS-cluster-containing enzymes and may be involved in electron relay cascades [153,154]. Two FeS clusters were found in nsp12 by Mössbauer spectroscopy, and the mutation of cysteine residues that ligate the cluster in the polymerase domain diminished polymerase activity [153,154]. Nsp13 uniquely ligates two zinc ions and one FeS cluster [154]. The replacement of the lone FeS cluster in nsp13 with zinc diminished the affinity of the helicase with its physiological substrate, dsRNA, instead increasing its affinity with dsDNA [154].

The most straightforward process the RTC undergoes inside the cell is continuous RNA synthesis. The viral positive RNA genome is first replicated to the negative sense, creating a double-stranded intermediate, the substrate of the helicase, nsp13 [54]. After unwinding, the negative sense strand is used as a template for synthesizing a new positive-sense viral RNA genome [53,54]. While simple, the act is incredible given the sheer size of the coronavirus genome, which can be three to four times the size of a typical RNA virus [149]. The speed with which the RdRp accomplishes this feat is also alarming. It is more than twice as fast as the poliovirus 3Dpol [149]. Generally, replication rates are inversely related to fidelity [155]. However, this is not the case for coronaviruses, whose RdRp has relatively comparable misincorporation rates to poliovirus 3Dpol, albeit slightly higher [149]. In vitro mutational studies attribute the high processivity rate with minimal loss of fidelity to an atypical alanine in the motif F active site of coronavirus nsp12 (as shown for SARS-CoV) and serine in motif C of the palm domain, respectively, as compared to the poliovirus 3Dpol [149].

Additionally, coronaviruses have a built-in proofreading exoribonuclease, nsp14, that cleaves misincorporated ribonucleotides. Nsp14 is in the DEDD family of 3′-5′ exonucleases and has been shown to be associated with the RdRp [148]. Nsp14 exoribonuclease activity is increased significantly in the presence of nsp10, a small cysteine-rich protein [148]. The substrate of the nsp14-nsp10 complex is dsRNA, which excises misincorporated ribonucleotides at the 3′ end [156]. Mutating the DEDD motif of MHV nsp14 of an infective virus results in an increased mutation rate of 15- to 20-fold higher than seen in a wild-type virus [157].

The second mode of function of the RTC is discontinuous RNA synthesis or the transcription of 3′-end structural and accessory factors [54]. This transcription relies on transcriptional regulatory sequences in the viral genomes between 3′ open reading frames that match a 5′ leader sequence [53,54]. During RNA synthesis, single-strand matching allows for template switching such that each newly synthesized 3′-end mRNA or subgenomic mRNA has both the 3′-end poly-A tail as well as the 5′-end up to the leader sequence, which is then capped, as discussed next [53,54].

7.3. RNA Capping

The coronavirus RNA-capping mechanism is a multi-enzyme process that mimics cellular RNA capping. It is essential for the virus to evade host cell immune 5′-3′ exonucleases that target uncapped RNAs, and it facilitates the translation of viral RNAs by cellular ribosomes [53]. After the synthesis of new viral genomic RNA or subgenomic mRNA, first, the 5′-most nucleotide γ-phosphate is hydrolyzed by nsp13 RTPase activity (pppA-RNA → ppA-RNA) [53]. Subsequently, the NiRAN domain of nsp12 acts as an RNA-guanylyl-transferase to transfer a guanosine monophosphate to the 5′-diphosphate RNA, resulting in a 5′–5′ triphosphate bridge or (GpppA-RNA) [53,158]. Nsp14, with its C-terminal N7-methyltransferase domain, is then recruited to methylate the N7 position of the guanosine, resulting in the cap-0 structure (7m-GpppA-RNA) [53]. Another methyl group is transferred to the 2’O position of the first mRNA nucleotide (7m-GpppAm2-RNA) by the S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) enzyme nsp16, with nsp10 as its cofactor [53]. This second methylation is important for preventing the reversal of the guanylyl transfer reaction [159].

7.4. Additional Functions of Nonstructural Proteins

Cellular translation repression by nsp1 was captured by cryo-electron microscopy to bind the 40S ribosomal subunit at the mRNA channel to inhibit translation in 2020 [160]. The repression of translation by nsp1 has two main advantages: (1) the inhibition of cellular innate immune responses and (2) the enhanced production of viral proteins [160]. There is evidence that viral proteins and critical host factors can bypass nsp1 translational repression, but how they do so is highly debated [161]. Bujanic et al. showed that specific residues within the first stem-loop of the leader sequences are both necessary and sufficient to bypass the repression of nsp1 translation [161]. Rao et al. determined that a 5′ terminal-oligopyrimidine is responsible for the evasion of viral translational repression [162]. Others have shown that multiple elements of viral RNAs enable this capability [160]. Nsp1 has also been shown to inhibit cellular innate immunity by catalyzing the cleavage of host cell defense mRNAs while protecting viral mRNAs by binding the 5′ leader sequence [163,164]. Ribosomal translation inhibition and the cleavage of host cell mRNAs by nsp1 are functionally distinct, as mutational studies of nsp1 are able to eliminate mRNA cleavage but not ribosomal inhibition [165]. Nsp15 is an RNA endonuclease that has also been linked to the degradation of cellular mRNAs and could be a target of therapeutics [166].

9. Conclusions and Final Remarks

Undoubtedly, coronaviruses have enormous potential to cause a great deal of harm and mayhem to humans [6,7,9,15,18,130]. Due to the safety precautions necessary to study the more pathogenic coronaviruses, Biosafety Level (BSL) 3 laboratories can be relatively inept, with equipment only providing the most basic requirements [16]. While highly pathogenic coronavirus research is undeniably important in determining antiviral treatment effectiveness before drug approval, endemic coronavirus research provides an opportunity to screen and evaluate antiviral therapeutics and make discoveries in a lower-biosafety-risk manner. Current techniques and methods of endemic coronavirus research in BSL 2 laboratories have finally risen to the challenge [14,23,24,96,168]. Discoveries made in endemic human coronaviruses will likely soar and lead to a deeper understanding of coronavirus biology and host cell biology, as well as better therapeutics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.L.H. Writing—original draft preparation, A.L.H. Writing—review and editing, A.L.H. and T.A.R. Visualization, A.L.H. and T.A.R. Supervision, T.A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Intramural Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (to T.A.R.) under the ZIA HD008814.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings are available in this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nunziata Maio, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, for advice and editing, Yolanda L. Jones, National Institutes of Health Library Editing Services, for editing assistance, the Intramural Research Program and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development for support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jaimes, J.A.; Andre, N.M.; Chappie, J.S.; Millet, J.K.; Whittaker, G.R. Phylogenetic Analysis and Structural Modeling of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Reveals an Evolutionary Distinct and Proteolytically Sensitive Activation Loop. J. Mol. Biol. 2020, 432, 3309–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Shah, T.; Wang, B.; Qu, L.; Wang, R.; Hou, Y.; Baloch, Z.; Xia, X. Cross-species transmission, evolution and zoonotic potential of coronaviruses. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 1081370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Hoek, L. Human coronaviruses: What do they cause? Antivir. Ther. 2007, 12, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradburne, A.F.; Bynoe, M.L.; Tyrrell, D.A. Effects of a “new” human respiratory virus in volunteers. Br. Med. J. 1967, 3, 767–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradburne, A.F.; Somerset, B.A. Coronative antibody tires in sera of healthy adults and experimentally infected volunteers. J. Hyg. 1972, 70, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ksiazek, T.G.; Erdman, D.; Goldsmith, C.S.; Zaki, S.R.; Peret, T.; Emery, S.; Tong, S.; Urbani, C.; Comer, J.A.; Lim, W.; et al. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 1953–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rota, P.A.; Oberste, M.S.; Monroe, S.S.; Nix, W.A.; Campagnoli, R.; Icenogle, J.P.; Penaranda, S.; Bankamp, B.; Maher, K.; Chen, M.H.; et al. Characterization of a novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Science 2003, 300, 1394–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drosten, C.; Gunther, S.; Preiser, W.; van der Werf, S.; Brodt, H.R.; Becker, S.; Rabenau, H.; Panning, M.; Kolesnikova, L.; Fouchier, R.A.; et al. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 1967–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Wong, G.; Shi, W.; Liu, J.; Lai, A.C.K.; Zhou, J.; Liu, W.; Bi, Y.; Gao, G.F. Epidemiology, Genetic Recombination, and Pathogenesis of Coronaviruses. Trends Microbiol. 2016, 24, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyrc, K.; Berkhout, B.; van der Hoek, L. The novel human coronaviruses NL63 and HKU1. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 3051–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Hoek, L.; Pyrc, K.; Jebbink, M.F.; Vermeulen-Oost, W.; Berkhout, R.J.; Wolthers, K.C.; Wertheim-van Dillen, P.M.; Kaandorp, J.; Spaargaren, J.; Berkhout, B. Identification of a new human coronavirus. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, P.C.; Lau, S.K.; Chu, C.M.; Chan, K.H.; Tsoi, H.W.; Huang, Y.; Wong, B.H.; Poon, R.W.; Cai, J.J.; Luk, W.K.; et al. Characterization and complete genome sequence of a novel coronavirus, coronavirus HKU1, from patients with pneumonia. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 884–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouchier, R.A.; Hartwig, N.G.; Bestebroer, T.M.; Niemeyer, B.; de Jong, J.C.; Simon, J.H.; Osterhaus, A.D. A previously undescribed coronavirus associated with respiratory disease in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 6212–6216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fausto, A.; Otter, C.J.; Bracci, N.; Weiss, S.R. Improved Culture Methods for Human Coronaviruses HCoV-OC43, HCoV-229E, and HCoV-NL63. Curr. Protoc. 2023, 3, e914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Memish, Z.A.; Zumla, A.I.; Al-Hakeem, R.F.; Al-Rabeeah, A.A.; Stephens, G.M. Family cluster of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 2487–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahkarami, M.; Yen, C.; Glaser, C.; Xia, D.; Watt, J.; Wadford, D.A. Laboratory Testing for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus, California, USA, 2013–2014. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015, 21, 1664–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zai, J.; Wang, X.; Li, Y. Potential of large “first generation” human-to-human transmission of 2019-nCoV. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.L.; Wang, X.G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.L.; et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenmaker, L.; Witzigmann, D.; Kulkarni, J.A.; Verbeke, R.; Kersten, G.; Jiskoot, W.; Crommelin, D.J.A. mRNA-lipid nanoparticle COVID-19 vaccines: Structure and stability. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 601, 120586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruell, H.; Vanshylla, K.; Weber, T.; Barnes, C.O.; Kreer, C.; Klein, F. Antibody-mediated neutralization of SARS-CoV-2. Immunity 2022, 55, 925–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, J.; Leister-Tebbe, H.; Gardner, A.; Abreu, P.; Bao, W.; Wisemandle, W.; Baniecki, M.; Hendrick, V.M.; Damle, B.; Simon-Campos, A.; et al. Oral Nirmatrelvir for High-Risk, Nonhospitalized Adults with Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1397–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najjar-Debbiny, R.; Gronich, N.; Weber, G.; Khoury, J.; Amar, M.; Stein, N.; Goldstein, L.H.; Saliba, W. Effectiveness of Paxlovid in Reducing Severe Coronavirus Disease 2019 and Mortality in High-Risk Patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 76, e342–e349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, R.; Watanabe, N.; Bandou, R.; Yoshida, T.; Daidoji, T.; Naito, Y.; Itoh, Y.; Nakaya, T. A Cytopathic Effect-Based Tissue Culture Method for HCoV-OC43 Titration Using TMPRSS2-Expressing VeroE6 Cells. mSphere 2021, 6, e00159-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirtzinger, E.E.; Kim, Y.; Davis, A.S. Improving human coronavirus OC43 (HCoV-OC43) research comparability in studies using HCoV-OC43 as a surrogate for SARS-CoV-2. J. Virol. Methods 2022, 299, 114317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.I.; Lee, C. Human Coronavirus OC43 as a Low-Risk Model to Study COVID-19. Viruses 2023, 15, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, P.S.; Perlman, S. Coronaviridae. In Fields Virology, 6th ed.; Knipe, D.M., Howley, P., Eds.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philidelphia, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 825–858. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, J.D.; Tyrrell, D.A. The morphology of three previously uncharacterized human respiratory viruses that grow in organ culture. J. Gen. Virol. 1967, 1, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudoux, P.; Carrat, C.; Besnardeau, L.; Charley, B.; Laude, H. Coronavirus pseudoparticles formed with recombinant M and E proteins induce alpha interferon synthesis by leukocytes. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 8636–8643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guruprasad, L. Human coronavirus spike protein-host receptor recognition. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2021, 161, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, C.B.; Farzan, M.; Chen, B.; Choe, H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, G.R.; Daniel, S.; Millet, J.K. Coronavirus entry: How we arrived at SARS-CoV-2. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2021, 47, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Q.; Langereis, M.A.; van Vliet, A.L.; Huizinga, E.G.; de Groot, R.J. Structure of coronavirus hemagglutinin-esterase offers insight into corona and influenza virus evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 9065–9069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, Y.; Li, W.; Li, Z.; Koerhuis, D.; van den Burg, A.C.S.; Rozemuller, E.; Bosch, B.J.; van Kuppeveld, F.J.M.; Boons, G.J.; Huizinga, E.G.; et al. Coronavirus hemagglutinin-esterase and spike proteins coevolve for functional balance and optimal virion avidity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 25759–25770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belshaw, R.; Pybus, O.G.; Rambaut, A. The evolution of genome compression and genomic novelty in RNA viruses. Genome Res. 2007, 17, 1496–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhao, S. Furin cleavage sites naturally occur in coronaviruses. Stem Cell Res. 2020, 50, 102115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milewska, A.; Nowak, P.; Owczarek, K.; Szczepanski, A.; Zarebski, M.; Hoang, A.; Berniak, K.; Wojarski, J.; Zeglen, S.; Baster, Z.; et al. Entry of Human Coronavirus NL63 into the Cell. J. Virol. 2018, 92, e01933-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owczarek, K.; Szczepanski, A.; Milewska, A.; Baster, Z.; Rajfur, Z.; Sarna, M.; Pyrc, K. Early events during human coronavirus OC43 entry to the cell. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kielian, M.; Rey, F.A. Virus membrane-fusion proteins: More than one way to make a hairpin. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006, 4, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuniga, S.; Cruz, J.L.; Sola, I.; Mateos-Gomez, P.A.; Palacio, L.; Enjuanes, L. Coronavirus nucleocapsid protein facilitates template switching and is required for efficient transcription. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 2169–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuniga, S.; Sola, I.; Moreno, J.L.; Sabella, P.; Plana-Duran, J.; Enjuanes, L. Coronavirus nucleocapsid protein is an RNA chaperone. Virology 2007, 357, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stohlman, S.A.; Baric, R.S.; Nelson, G.N.; Soe, L.H.; Welter, L.M.; Deans, R.J. Specific interaction between coronavirus leader RNA and nucleocapsid protein. J. Virol. 1988, 62, 4288–4295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almazan, F.; Galan, C.; Enjuanes, L. The nucleoprotein is required for efficient coronavirus genome replication. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 12683–12688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturman, L.S.; Holmes, K.V. The molecular biology of coronaviruses. Adv. Virus Res. 1983, 28, 35–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturman, L.S.; Holmes, K.V. Characterization of coronavirus II. Glycoproteins of the viral envelope: Tryptic peptide analysis. Virology 1977, 77, 650–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, F.; Khan, K.S.; Le, T.K.; Paris, C.; Demirbag, S.; Barfuss, P.; Rocchi, P.; Ng, W.L. Coronavirus RNA Proofreading: Molecular Basis and Therapeutic Targeting. Mol. Cell 2020, 80, 1136–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snijder, E.J.; Decroly, E.; Ziebuhr, J. The Nonstructural Proteins Directing Coronavirus RNA Synthesis and Processing. Adv. Virus Res. 2016, 96, 59–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziebuhr, J.; Snijder, E.J.; Gorbalenya, A.E. Virus-encoded proteinases and proteolytic processing in the Nidovirales. J. Gen. Virol. 2000, 81, 853–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snijder, E.J.; Bredenbeek, P.J.; Dobbe, J.C.; Thiel, V.; Ziebuhr, J.; Poon, L.L.; Guan, Y.; Rozanov, M.; Spaan, W.J.; Gorbalenya, A.E. Unique and conserved features of genome and proteome of SARS-coronavirus, an early split-off from the coronavirus group 2 lineage. J. Mol. Biol. 2003, 331, 991–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelini, M.M.; Akhlaghpour, M.; Neuman, B.W.; Buchmeier, M.J. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus nonstructural proteins 3, 4, and 6 induce double-membrane vesicles. mBio 2013, 4, e00524-13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosert, R.; Kanjanahaluethai, A.; Egger, D.; Bienz, K.; Baker, S.C. RNA replication of mouse hepatitis virus takes place at double-membrane vesicles. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 3697–3708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snijder, E.J.; Limpens, R.; de Wilde, A.H.; de Jong, A.W.M.; Zevenhoven-Dobbe, J.C.; Maier, H.J.; Faas, F.; Koster, A.J.; Barcena, M. A unifying structural and functional model of the coronavirus replication organelle: Tracking down RNA synthesis. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolff, G.; Limpens, R.; Zevenhoven-Dobbe, J.C.; Laugks, U.; Zheng, S.; de Jong, A.W.M.; Koning, R.I.; Agard, D.A.; Grunewald, K.; Koster, A.J.; et al. A molecular pore spans the double membrane of the coronavirus replication organelle. Science 2020, 369, 1395–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevajol, M.; Subissi, L.; Decroly, E.; Canard, B.; Imbert, I. Insights into RNA synthesis, capping, and proofreading mechanisms of SARS-coronavirus. Virus Res. 2014, 194, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sola, I.; Almazan, F.; Zuniga, S.; Enjuanes, L. Continuous and Discontinuous RNA Synthesis in Coronaviruses. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2015, 2, 265–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatakeyama, S.; Matsuoka, Y.; Ueshiba, H.; Komatsu, N.; Itoh, K.; Shichijo, S.; Kanai, T.; Fukushi, M.; Ishida, I.; Kirikae, T.; et al. Dissection and identification of regions required to form pseudoparticles by the interaction between the nucleocapsid (N) and membrane (M) proteins of SARS coronavirus. Virology 2008, 380, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.; Dellibovi-Ragheb, T.A.; Kerviel, A.; Pak, E.; Qiu, Q.; Fisher, M.; Takvorian, P.M.; Bleck, C.; Hsu, V.W.; Fehr, A.R.; et al. beta-Coronaviruses Use Lysosomes for Egress Instead of the Biosynthetic Secretory Pathway. Cell 2020, 183, 1520–1535.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forni, D.; Cagliani, R.; Pozzoli, U.; Mozzi, A.; Arrigoni, F.; De Gioia, L.; Clerici, M.; Sironi, M. Dating the Emergence of Human Endemic Coronaviruses. Viruses 2022, 14, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forni, D.; Cagliani, R.; Clerici, M.; Sironi, M. Molecular Evolution of Human Coronavirus Genomes. Trends Microbiol. 2017, 25, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forni, D.; Cagliani, R.; Arrigoni, F.; Benvenuti, M.; Mozzi, A.; Pozzoli, U.; Clerici, M.; De Gioia, L.; Sironi, M. Adaptation of the endemic coronaviruses HCoV-OC43 and HCoV-229E to the human host. Virus Evol. 2021, 7, veab061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesheh, M.M.; Hosseini, P.; Soltani, S.; Zandi, M. An overview on the seven pathogenic human coronaviruses. Rev. Med. Virol. 2022, 32, e2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Wang, K.; Ping, X.; Yu, W.; Qian, Z.; Xiong, S.; Sun, B. The ns12.9 Accessory Protein of Human Coronavirus OC43 Is a Viroporin Involved in Virion Morphogenesis and Pathogenesis. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 11383–11395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenhard, S.; Gerlich, S.; Khan, A.; Rodl, S.; Bokenkamp, J.E.; Peker, E.; Zarges, C.; Faust, J.; Storchova, Z.; Raschle, M.; et al. The Orf9b protein of SARS-CoV-2 modulates mitochondrial protein biogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 2023, 222, e202303002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.R.; Ye, Z.W.; Lui, P.Y.; Zheng, X.; Yuan, S.; Zhu, L.; Fung, S.Y.; Yuen, K.S.; Siu, K.L.; Yeung, M.L.; et al. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus ORF8b Accessory Protein Suppresses Type I IFN Expression by Impeding HSP70-Dependent Activation of IRF3 Kinase IKKepsilon. J. Immunol. 2020, 205, 1564–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sriwilaijaroen, N.; Suzuki, Y. Roles of Sialyl Glycans in HCoV-OC43, HCoV-HKU1, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 Infections. Methods Mol. Biol. 2022, 2556, 243–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Pohlmann, S. A Multibasic Cleavage Site in the Spike Protein of SARS-CoV-2 Is Essential for Infection of Human Lung Cells. Mol. Cell 2020, 78, 779–784.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, J.; Wan, Y.; Luo, C.; Ye, G.; Geng, Q.; Auerbach, A.; Li, F. Cell entry mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 11727–11734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.J.; Walls, A.C.; Wang, Z.; Sauer, M.M.; Li, W.; Tortorici, M.A.; Bosch, B.J.; DiMaio, F.; Veesler, D. Structures of MERS-CoV spike glycoprotein in complex with sialoside attachment receptors. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2019, 26, 1151–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomris, I.; Unione, L.; Nguyen, L.; Zaree, P.; Bouwman, K.M.; Liu, L.; Li, Z.; Fok, J.A.; Rios Carrasco, M.; van der Woude, R.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Spike N-Terminal Domain Engages 9-O-Acetylated alpha2-8-Linked Sialic Acids. ACS Chem. Biol. 2023, 18, 1180–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Rasool, S.; Fielding, B.C. Understanding Human Coronavirus HCoV-NL63. Open Virol. J. 2010, 4, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Tomlinson, A.C.; Wong, A.H.; Zhou, D.; Desforges, M.; Talbot, P.J.; Benlekbir, S.; Rubinstein, J.L.; Rini, J.M. The human coronavirus HCoV-229E S-protein structure and receptor binding. eLife 2019, 8, e51230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pronker, M.F.; Creutznacher, R.; Drulyte, I.; Hulswit, R.J.G.; Li, Z.; van Kuppeveld, F.J.M.; Snijder, J.; Lang, Y.; Bosch, B.J.; Boons, G.J.; et al. Sialoglycan binding triggers spike opening in a human coronavirus. Nature 2023, 624, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, N.; Schwartz, O. [TMPRSS2 is the receptor of seasonal coronavirus HKU1]. Med. Sci. 2024, 40, 335–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortorici, M.A.; Walls, A.C.; Lang, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, Z.; Koerhuis, D.; Boons, G.J.; Bosch, B.J.; Rey, F.A.; de Groot, R.J.; et al. Structural basis for human coronavirus attachment to sialic acid receptors. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2019, 26, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakkers, M.J.; Lang, Y.; Feitsma, L.J.; Hulswit, R.J.; de Poot, S.A.; van Vliet, A.L.; Margine, I.; de Groot-Mijnes, J.D.; van Kuppeveld, F.J.; Langereis, M.A.; et al. Betacoronavirus Adaptation to Humans Involved Progressive Loss of Hemagglutinin-Esterase Lectin Activity. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 21, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurdiss, D.L.; Drulyte, I.; Lang, Y.; Shamorkina, T.M.; Pronker, M.F.; van Kuppeveld, F.J.M.; Snijder, J.; de Groot, R.J. Cryo-EM structure of coronavirus-HKU1 haemagglutinin esterase reveals architectural changes arising from prolonged circulation in humans. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Ye, G.; Shi, K.; Wan, Y.; Luo, C.; Aihara, H.; Geng, Q.; Auerbach, A.; Li, F. Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2020, 581, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, G.; Nelli, R.K.; Phadke, K.S.; Bravo-Parra, M.; Mora-Diaz, J.C.; Bellaire, B.H.; Gimenez-Lirola, L.G. SARS-CoV-2 Is More Efficient than HCoV-NL63 in Infecting a Small Subpopulation of ACE2+ Human Respiratory Epithelial Cells. Viruses 2023, 15, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, H.; Pyrc, K.; van der Hoek, L.; Geier, M.; Berkhout, B.; Pohlmann, S. Human coronavirus NL63 employs the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus receptor for cellular entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 7988–7993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Moore, M.J.; Vasilieva, N.; Sui, J.; Wong, S.K.; Berne, M.A.; Somasundaran, M.; Sullivan, J.L.; Luzuriaga, K.; Greenough, T.C.; et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature 2003, 426, 450–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Shi, X.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, S.; Wang, D.; Tong, P.; Guo, D.; Fu, L.; Cui, Y.; Liu, X.; et al. Structure of MERS-CoV spike receptor-binding domain complexed with human receptor DPP4. Cell Res. 2013, 23, 986–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petitjean, S.J.L.; Chen, W.; Koehler, M.; Jimmidi, R.; Yang, J.; Mohammed, D.; Juniku, B.; Stanifer, M.L.; Boulant, S.; Vincent, S.P.; et al. Multivalent 9-O-Acetylated-sialic acid glycoclusters as potent inhibitors for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, E.A.; Moons, S.J.; Timmermans, S.; de Jong, H.; Boltje, T.J.; Bull, C. Sialic acid O-acetylation: From biosynthesis to roles in health and disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 297, 100906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Hesketh, E.L.; Shamorkina, T.M.; Li, W.; Franken, P.J.; Drabek, D.; van Haperen, R.; Townend, S.; van Kuppeveld, F.J.M.; Grosveld, F.; et al. Antigenic structure of the human coronavirus OC43 spike reveals exposed and occluded neutralizing epitopes. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Lu, Y.; Pu, D.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; et al. TMPRSS2 and glycan receptors synergistically facilitate coronavirus entry. Cell 2024, 187, 4261–4271.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corman, V.M.; Muth, D.; Niemeyer, D.; Drosten, C. Hosts and Sources of Endemic Human Coronaviruses. Adv. Virus Res. 2018, 100, 163–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Liu, Z.; Chen, D. Human coronaviruses: Origin, host and receptor. J. Clin. Virol. 2022, 155, 105246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temmam, S.; Vongphayloth, K.; Baquero, E.; Munier, S.; Bonomi, M.; Regnault, B.; Douangboubpha, B.; Karami, Y.; Chretien, D.; Sanamxay, D.; et al. Bat coronaviruses related to SARS-CoV-2 and infectious for human cells. Nature 2022, 604, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Xia, L.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, Q. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science 2020, 367, 1444–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Protein Atlas. Available online: https://Proteinatlas.org (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Uhlen, M.; Fagerberg, L.; Hallstrom, B.M.; Lindskog, C.; Oksvold, P.; Mardinoglu, A.; Sivertsson, A.; Kampf, C.; Sjostedt, E.; Asplund, A.; et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 2015, 347, 1260419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnard, K.N.; Wasik, B.R.; LaClair, J.R.; Buchholz, D.W.; Weichert, W.S.; Alford-Lawrence, B.K.; Aguilar, H.C.; Parrish, C.R. Expression of 9-O- and 7,9-O-Acetyl Modified Sialic Acid in Cells and Their Effects on Influenza Viruses. mBio 2019, 10, e02490-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, A.; Krishna, M.; Varki, N.M.; Varki, A. 9-O-acetylated sialic acids have widespread but selective expression: Analysis using a chimeric dual-function probe derived from influenza C hemagglutinin-esterase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 7782–7786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langereis, M.A.; Bakkers, M.J.; Deng, L.; Padler-Karavani, V.; Vervoort, S.J.; Hulswit, R.J.; van Vliet, A.L.; Gerwig, G.J.; de Poot, S.A.; Boot, W.; et al. Complexity and Diversity of the Mammalian Sialome Revealed by Nidovirus Virolectins. Cell Rep. 2015, 11, 1966–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sims, A.C.; Burkett, S.E.; Yount, B.; Pickles, R.J. SARS-CoV replication and pathogenesis in an in vitro model of the human conducting airway epithelium. Virus Res. 2008, 133, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.C.; Ho, C.T.; Chuo, W.H.; Li, S.; Wang, T.T.; Lin, C.C. Effective inhibition of MERS-CoV infection by resveratrol. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Ma, C.; Wang, J. Cytopathic Effect Assay and Plaque Assay to Evaluate in vitro Activity of Antiviral Compounds Against Human Coronaviruses 229E, OC43, and NL63. Bio-Protocol 2022, 12, e4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, H.L.; Bonavita, C.M.; Navarrete-Macias, I.; Vilchez, B.; Rasmussen, A.L.; Anthony, S.J. The coronavirus recombination pathway. Cell Host Microbe 2023, 31, 874–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, H.L.; Letko, M.; Lasso, G.; Ssebide, B.; Nziza, J.; Byarugaba, D.K.; Navarrete-Macias, I.; Liang, E.; Cranfield, M.; Han, B.A.; et al. The evolutionary history of ACE2 usage within the coronavirus subgenus Sarbecovirus. bioRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boni, M.F.; Lemey, P.; Jiang, X.; Lam, T.T.; Perry, B.W.; Castoe, T.A.; Rambaut, A.; Robertson, D.L. Evolutionary origins of the SARS-CoV-2 sarbecovirus lineage responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 1408–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytras, S.; Xia, W.; Hughes, J.; Jiang, X.; Robertson, D.L. The animal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Science 2021, 373, 968–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenizia, C.; Galbiati, S.; Vanetti, C.; Vago, R.; Clerici, M.; Tacchetti, C.; Daniele, T. SARS-CoV-2 Entry: At the Crossroads of CD147 and ACE2. Cells 2021, 10, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantuti-Castelvetri, L.; Ojha, R.; Pedro, L.D.; Djannatian, M.; Franz, J.; Kuivanen, S.; van der Meer, F.; Kallio, K.; Kaya, T.; Anastasina, M.; et al. Neuropilin-1 facilitates SARS-CoV-2 cell entry and infectivity. Science 2020, 370, 856–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Qiu, Z.; Hou, Y.; Deng, X.; Xu, W.; Zheng, T.; Wu, P.; Xie, S.; Bian, W.; Zhang, C.; et al. AXL is a candidate receptor for SARS-CoV-2 that promotes infection of pulmonary and bronchial epithelial cells. Cell Res. 2021, 31, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, B.; Lv, Y.; Moser, D.; Zhou, X.; Woehrle, T.; Han, L.; Osterman, A.; Rudelius, M.; Chouker, A.; Lei, P. ACE2-independent SARS-CoV-2 virus entry through cell surface GRP78 on monocytes—Evidence from a translational clinical and experimental approach. EBioMedicine 2023, 98, 104869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Z.; Wang, C.; Tang, X.; Yang, M.; Duan, Z.; Liu, L.; Lu, S.; Ma, L.; Cheng, R.; Wang, G.; et al. Human transferrin receptor can mediate SARS-CoV-2 infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2317026121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggen, J.; Jacquemyn, M.; Persoons, L.; Vanstreels, E.; Pye, V.E.; Wrobel, A.G.; Calvaresi, V.; Martin, S.R.; Roustan, C.; Cronin, N.B.; et al. TMEM106B is a receptor mediating ACE2-independent SARS-CoV-2 cell entry. Cell 2023, 186, 3427–3442.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M. Cellular Tropism of SARS-CoV-2 across Human Tissues and Age-related Expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in Immune-inflammatory Stromal Cells. Aging Dis. 2021, 12, 718–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, S.K.; Lee, P.; Tsang, A.K.; Yip, C.C.; Tse, H.; Lee, R.A.; So, L.Y.; Lau, Y.L.; Chan, K.H.; Woo, P.C.; et al. Molecular epidemiology of human coronavirus OC43 reveals evolution of different genotypes over time and recent emergence of a novel genotype due to natural recombination. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 11325–11337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berche, P. The enigma of the 1889 Russian flu pandemic: A coronavirus? Presse Med. 2022, 51, 104111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monto, A.S.; DeJonge, P.M.; Callear, A.P.; Bazzi, L.A.; Capriola, S.B.; Malosh, R.E.; Martin, E.T.; Petrie, J.G. Coronavirus Occurrence and Transmission Over 8 Years in the HIVE Cohort of Households in Michigan. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 222, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrie, J.G.; Bazzi, L.A.; McDermott, A.B.; Follmann, D.; Esposito, D.; Hatcher, C.; Mateja, A.; Narpala, S.R.; O’Connell, S.E.; Martin, E.T.; et al. Coronavirus Occurrence in the Household Influenza Vaccine Evaluation (HIVE) Cohort of Michigan Households: Reinfection Frequency and Serologic Responses to Seasonal and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronaviruses. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 224, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fine, S.R.; Bazzi, L.A.; Callear, A.P.; Petrie, J.G.; Malosh, R.E.; Foster-Tucker, J.E.; Smith, M.; Ibiebele, J.; McDermott, A.; Rolfes, M.A.; et al. Respiratory virus circulation during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic in the Household Influenza Vaccine Evaluation (HIVE) cohort. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2023, 17, e13106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.M.; Winn, A.; Dahl, R.M.; Kniss, K.L.; Silk, B.J.; Killerby, M.E. Seasonality of Common Human Coronaviruses, United States, 2014–2021. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022, 28, 1970–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killerby, M.E.; Biggs, H.M.; Haynes, A.; Dahl, R.M.; Mustaquim, D.; Gerber, S.I.; Watson, J.T. Human coronavirus circulation in the United States 2014–2017. J. Clin. Virol. 2018, 101, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Gwee, S.X.W.; Ng, J.Q.X.; Lau, N.; Koh, J.; Pang, J. Wastewater surveillance to infer COVID-19 transmission: A systematic review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 804, 150060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boehm, A.B.; Hughes, B.; Duong, D.; Chan-Herur, V.; Buchman, A.; Wolfe, M.K.; White, B.J. Wastewater concentrations of human influenza, metapneumovirus, parainfluenza, respiratory syncytial virus, rhinovirus, and seasonal coronavirus nucleic-acids during the COVID-19 pandemic: A surveillance study. Lancet Microbe 2023, 4, e340–e348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamre, D.; Procknow, J.J. A new virus isolated from the human respiratory tract. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1966, 121, 190–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]