Abstract

Monkeypox virus (MPXV) re-emerged in 2022 with a global outbreak that affected more than 100,000 individuals worldwide. People living with HIV (PLWH) accounted for a substantial proportion of cases, raising concerns about disease presentation, management, and outcomes in this population. Evidence indicates that PLWH with advanced or uncontrolled HIV infection experienced more severe mpox, with higher hospitalization rates, more complications, and longer disease courses. In contrast, individuals with well-controlled HIV generally had outcomes similar to those without HIV. Access to timely diagnosis, consistent antiretroviral therapy, and availability of tecovirimat were key factors influencing prognosis. Reports also suggest bidirectional interactions between mpox and HIV pathogenesis. Immune activation and APOBEC3-related viral evolution have been proposed; however, these mechanisms remain incompletely characterized and warrant further investigation. Moreover, disparities in healthcare access and stigma compound the vulnerability of PLWH, emphasizing the need for integrated approaches.

1. Introduction

Mpox, caused by the monkeypox virus (MPXV), is a zoonotic disease historically endemic to West and Central Africa, where human–animal interactions and wildlife reservoirs facilitated transmission. In recent years, however, mpox has emerged as a global health concern, highlighting its potential for international spread. Human-to-human transmission occurs mainly through direct contact with skin lesions, bodily fluids, or respiratory droplets from infected individuals or animals [1,2].

The global outbreak that began in May 2022 was unprecedented in scale and differed from earlier outbreaks by sustaining human-to-human transmission across international sexual networks. Most cases were reported among men who have sex with men (MSM), many of whom were people living with HIV (PLWH), underscoring shared transmission routes and specific immunological vulnerabilities in this population [3].

MPXV is currently classified into two major clades: clade I (Congo Basin, subdivided into Ia and Ib) and clade II (West African, subdivided into IIa and IIb). These clades differ in virulence, with clade I generally associated with more severe outcomes and higher case fatality rates [1,2,3]. The 2022 multinational outbreak was driven by clade IIb, which spread to more than 121 countries and led the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, later lifted in 2023 [3]. Since then, clade Ib outbreaks have predominated in Central Africa, particularly in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), with growing evidence of international spread, and have progressively extended beyond the region. Recently, imported cases have been detected in multiple countries across Europe, Asia, and the Americas, including cases without travel history, indicating sustained human-to-human transmission outside Africa [3,4].

Epidemiological patterns also differ between clades. Clade IIb primarily affected MSM aged 30–39 years (87% of global cases), whereas clade I outbreaks in the DRC have disproportionately affected children under 15 years, who accounted for 70% of cases and nearly 90% of deaths [3,5,6,7]. Although global incidence declined after 2022, both clades continue to circulate, sustained by animal reservoirs and persistent human-to-human transmission [3]. The recent emergence and transcontinental spread of clade Ib underscore its potential for wider dissemination and highlight the urgent need for enhanced laboratory and genomic surveillance worldwide.

Mpox–HIV co-infection has become a pressing clinical concern. PLWH with advanced immunosuppression—particularly those with low CD4+ T-cell counts or uncontrolled viremia—face an elevated risk of severe disease, complications, prolonged viral shedding, hospitalization, and death. Conversely, individuals with well-controlled HIV generally present outcomes comparable to those without HIV. Mpox infection may also alter immune dynamics in PLWH, raising unresolved questions about antiviral efficacy, vaccine immunogenicity, and long-term management [8].

This review provides a comprehensive synthesis of the current evidence on mpox in PLWH, with emphasis on epidemiology, clinical features, pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment, prevention, and public health implications.

2. Epidemiology of Mpox–HIV Co-Infection

During the 2022 outbreak, HIV co-infection emerged as a key determinant of disease burden and outcomes. WHO data indicated that most cases occurred among MSM (87.0%). Among those with known HIV status, 51.2% were people living with HIV (PLWH), a prevalence markedly higher than the background level in this group [3]. Multiple cohort studies across Europe and the Americas consistently reported 38–41% of mpox cases in PLWH, confirming the strong overlap with HIV-positive sexual networks [9,10,11].

Advanced immunosuppression was strongly linked to adverse outcomes. Hospitalization rates approached 30% among PLWH with CD4 counts <100 cells/µL, compared with 16% in those with CD4 >300 cells/µL. Mortality reached 27% in the most severely immunocompromised patients [8]. In African clade Ib epidemics, case fatality rates reached up to 10%, with children and PLWH disproportionately affected. Pediatric infections accounted for approximately 5–10% of reported cases in endemic regions, frequently linked to household transmission, whereas women represented less than 3% of global cases during the 2022 outbreak, though they remain particularly vulnerable in endemic settings through caregiving and community exposure rather than sexual transmission [8,12,13,14].

These findings underscore the critical need to integrate mpox surveillance, diagnosis, prevention, and treatment strategies within existing HIV care frameworks, particularly for populations at highest risk [3,15].

3. Clinical Manifestations

Before 2022, mpox typically presented with fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy, and a synchronous vesiculopustular rash. Most cases were self-limiting within 2–4 weeks, with case fatality rates (CFR) <4% for clade II and ~11% for clade I, particularly among children [9,16,17,18,19].

The 2022 multinational outbreak displayed distinctive features, including asynchronous lesion development, frequent genital and perianal involvement, and proctitis as an initial presentation, sometimes requiring hospitalization. Painful oral ulcers were common, whereas lymphadenopathy appeared less frequent than in earlier descriptions. Pregnancy was associated with poor outcomes, with fetal loss reported in up to 50% of cases [18,20,21,22].

Clinical expression varied by viral clade. In the 2024 DRC outbreak (clade Ib), children exhibited widespread extragenital lesions and higher morbidity, although overall mortality was relatively low (0.5%). However, pregnancy losses remained frequent among infected women [23]. By contrast, the global clade IIb epidemic predominantly affected MSM, with risk strongly linked to multiple sexual partners and concomitant sexually transmitted infections (STIs) [24].

Among PLWH, incidence ranged from 38 to 50% [21,25,26,27]. Genital, anal, and perianal lesions, proctitis, and severe necrotizing mucocutaneous disease were disproportionately observed, alongside systemic complications such as pneumonitis, central nervous system involvement, endocarditis, and ocular disease [21,25,26,27,28,29].

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses confirmed poorer outcomes in PLWH. Hospitalization risk was significantly higher (pooled RR 1.57; 95% CI: 1.18–2.08), particularly among those with CD4 counts <200 cells/µL (pooled OR 5.3; 95% CI: 2.0–14.1; p < 0.001) or unsuppressed viremia (pooled OR 3.0; 95% CI: 2.1–4.2) [26,30,31]. Mortality was also elevated (pooled OR 3.9; 95% CI: 2.27–6.65; p < 0.001), with most deaths occurring in severely immunosuppressed individuals [26,29,31,32]. Fatality rates up to 13% were reported among hospitalized cases [26,27].

Collectively, these findings support proposals to classify disseminated or necrotizing mpox as an AIDS-defining condition [8,28,33].

4. Diagnosis and Laboratory Considerations

Timely diagnosis of mpox is critical, particularly in PLWH with immunosuppression, who face a higher risk of severe disease. In suspected cases, especially where sexual transmission is possible or HIV status is unknown, the WHO recommends concurrent HIV testing alongside mpox evaluation [21,34].

Nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT), particularly real-time PCR, remains the diagnostic gold standard. Assays can either detect Orthopoxvirus broadly or MPXV specifically, while clade-specific PCR and whole-genome sequencing (WGS) may further refine diagnosis and inform surveillance [35]. Lesion swabs and crusts are the preferred samples; oropharyngeal swabs can also be informative. Depending on clinical presentation, anorectal swabs, semen, urine, cerebrospinal fluid, or vitreous fluid may be collected [35]. PCR testing of EDTA whole blood has limited sensitivity due to the brief duration of viremia. Serology is not routinely recommended, although acute IgM detection or a four-fold rise in IgG titers may support diagnosis [35].

Basic laboratory investigations should include complete blood count, renal and hepatic function tests, and cultures for bacterial superinfection. Reported abnormalities include leukocytosis, elevated transaminases, altered blood urea nitrogen (low or high), hypoalbuminemia, and cytopenia [21,34,35,36].

The differential diagnosis is broad and includes varicella-zoster virus (VZV), herpes simplex virus (HSV), syphilis, disseminated gonococcal infection, measles, scabies, dengue, Zika virus, vasculitis, and bacterial skin infections. In immunocompromised patients, disseminated cryptococcosis may also mimic mpox [21,35]. Unlike VZV, mpox typically shows slower lesion progression, a more centrifugal rash, and lymphadenopathy, which is uncommon in varicella. Lesions on palms and soles may occur, but are not consistent features. PCR-confirmed mpox–VZV co-infection has been reported in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (10–13%), presenting with overlapping clinical signs and an intermediate lesion burden between both infections. Co-infections with other STIs, such as syphilis or gonorrhea, are also frequent in sexual transmission networks [21].

Hospitalization is strongly recommended for PLWH with CD4 counts <100 cells/µL or uncontrolled HIV viremia, due to the high risk of necrotizing lesions, bacterial sepsis, and systemic complications [8,35]. Importantly, while diagnosis and laboratory work-up are similar for individuals with and without HIV, the threshold for hospitalization and the intensity of monitoring must be lower in PLWH, particularly those with advanced immunosuppression.

5. Intra-Host Genetic Variability in PLWH

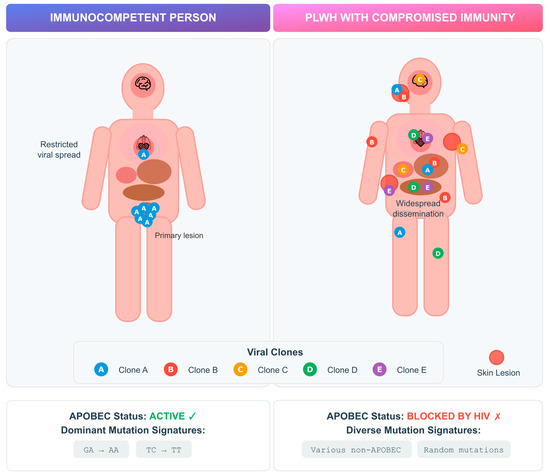

Advanced HIV infection provides a permissive environment for persistent MPXV replication, which may drive intra-host diversification. Similar dynamics have been observed in other viral infections, such as SARS-CoV-2, where prolonged replication in immunocompromised hosts enabled rapid viral evolution [37] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Intra-host MPXV genetic variability in PLWH versus immunocompetent individuals. Schematic representation of viral replication dynamics and mutational patterns according to host immune status. In immunocompetent individuals (left), APOBEC3-mediated cytidine deamination restricts viral replication and drives characteristic G→A and TC→TT mutation signatures. In PLWH with advanced immunosuppression (right), impaired APOBEC activity permits widespread viral dissemination and intra-host diversification, resulting in multiple viral clones and heterogeneous, non-APOBEC mutation patterns.

Case studies have described multiple viral clones in single mpox infections, including in PLWH, suggesting diversification can occur early in infection [38,39]. MPXV, as a DNA virus, mutates more slowly than RNA viruses, and much of its diversity is thought to result from APOBEC-mediated editing [40,41]. APOBEC (apolipoprotein B mRNA-editing enzyme catalytic polypeptide-like) proteins are host cytidine deaminases that normally restrict viral replication by inducing G-to-A hypermutations in viral genomes. In MPXV, APOBEC activity leaves a characteristic mutational signature likely to have been an important driver of viral evolution during the 2022 outbreak, as well as suggesting sustained human transmission since at least 2016 [40,41]. Interestingly, studies in patients with advanced HIV revealed novel mutations lacking the characteristic APOBEC signature. In particular, a Vietnamese cohort study involving patients with severely compromised immune systems (median CD4 count of 14/µL) revealed 10/12 new mutations without APOBEC patterns, suggesting alternative evolutionary mechanisms under immunosuppression [42].

Comparative analyses further highlight divergent dynamics depending on immune status. An Italian study identified that in immunocompetent patients, identical viral clones were usually detected across anatomical sites, whereas in advanced HIV, prolonged infection allowed distinct clones to emerge in different tissues over time [43]. This compartmentalized evolution may affect transmissibility, shedding duration, and treatment outcomes.

The relatively low mutation rate of MPXV makes it hard to distinguish between within-host evolution and simultaneous infection [44]. Although co-infections with multiple strains have been reported, most observed diversity likely reflects within-host evolution rather than simultaneous infection by different lineages [44,45]. Moreover, technical limitations may also be hindering our ability to detect viral diversity. Beyond point mutations, MPXV exhibits genome plasticity through structural changes such as gene duplication, loss, and ITR expansion, which may enhance adaptability but are often missed in routine sequencing [44].

Despite HIV being disproportionately represented among mpox cases, studies of viral genomic diversity from PLWH remain scarce, especially from Africa, where both HIV and MPXV are endemic and clade I outbreaks continue to drive high morbidity [46]. Recent sequencing efforts are beginning to bridge this gap, but more studies integrating longitudinal, multi-site sampling with immunological and clinical data are needed. Single-cell transcriptomic analyses suggest that even virologically suppressed PLWH display distinct immune responses during acute mpox, potentially influencing viral diversification [47].

In sum, intra-host MPXV variability in PLWH appears to result from prolonged replication, impaired immune control, and tissue-specific pressures. Understanding these dynamics will require dedicated studies and enhanced genomic surveillance, particularly in endemic regions.

6. Immunopathogenesis and Disease Progression

6.1. Viral Load Dynamics During Mpox Infection

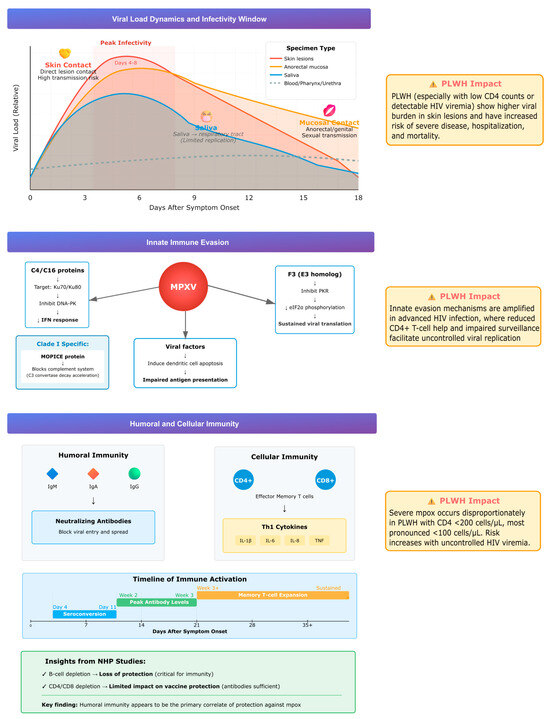

Understanding viral load dynamics and viable virus shedding in different types of clinical lesions has been shown to be relevant to patient care, severity assessment and infection control (Figure 2). PLWH tend to present higher viral loads in skin lesions, and reduced CD4+ T-cell counts or uncontrolled HIV viremia correlate with severe disease, hospitalization, and mortality. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 19 studies (880 patients, 1477 specimens) confirmed that skin lesions, anorectal swabs, and saliva contain the highest viral DNA, while pharyngeal, urethral, and blood samples usually show lower levels. Anorectal and saliva specimens also yielded viable virus more frequently, supporting their role in transmission. Viral loads typically peaked 4–8 days after symptom onset, with viable virus persisting for 14–19 days depending on specimen type. Although saliva contained high viral loads, the respiratory tract does not appear to be the primary replication site, suggesting that direct mucosal contact rather than inhalation plays a larger role in transmission. PLWH showed significantly higher viral burden in skin lesions, though differences in other sample types were less pronounced [48]. Taken together, these data support that the peak infectious period takes place early in the disease course and may persist for up to three weeks, highlighting the importance of early detection and infection prevention measures to be implemented. Clinical monitoring is of particular relevance in the setting of uncontrolled HIV infection, due to higher viral loads and worse outcomes in the setting of immunocompromise.

Figure 2.

Summary of viral load dynamics, immune evasion, and host responses during mpox infection, highlighting higher viral burden and impaired immunity in PLWH.

6.2. Innate Immunity Evasion

MPXV employs several strategies to evade host innate immunity. Viral proteins C4 and C16 inhibit DNA sensing by targeting the Ku heterodimer (Ku70/Ku80), which normally activates the DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK) pathway, a key sensor of cytosolic DNA that triggers interferon responses. By blocking this pathway, MPXV prevents recognition of its genome as a danger signal. The virus also suppresses natural killer (NK) cell function by reducing TNF-α and IFN-γ secretion. The F3 protein, a vaccinia virus E3 homolog, disrupts the interferon–protein kinase R (IFN–PKR) axis by blocking PKR activation and eIF2α phosphorylation, thereby suppressing interferon signaling and sustaining viral protein synthesis. In dendritic cells, MPXV induces apoptosis, impairing antigen presentation and adaptive immune priming [49].

A distinctive virulence factor of clade I (Congo Basin) strains is the MPXV inhibitor of complement enzymes (MOPICE), which binds complement proteins and accelerates C3 convertase decay, blocking both classical and alternative complement pathways. This complement evasion likely contributes to the greater virulence and higher case fatality rates associated with clade I compared with clade II [49].

These mechanisms operate in all hosts but are particularly consequential in PLWH with advanced immunosuppression, where diminished CD4+ T-cell function and impaired immune surveillance exacerbate viral escape and promote severe, uncontrolled infection.

6.3. Humoral and Cellular Immunity

Acute MPXV infection induces rapid and effective immune responses. Early seroconversion with IgM, IgA, and IgG occurs, along with neutralizing antibody development [50]. Infection also triggers expansion of effector memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, accompanied by a Th1-skewed cytokine profile characterized by elevated IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF [51,52]. Protection against severe disease in non-human primate models of vaccination appears primarily antibody-mediated, as B-cell depletion abrogates protection, whereas depletion of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells has a limited effect [51]. This highlights the central role of humoral immunity, although cellular immunity contributes to viral clearance. In PLWH, progressive CD4+ T-cell depletion compromises both arms of the immune response. Clinical data confirm that PLWH with CD4 counts <200 cells/µL, and especially <100 cells/µL, are disproportionately affected by severe mpox. In a series of 382 HIV-positive patients, lower CD4 counts were strongly associated with disease severity compared with those maintaining CD4 counts of 200–350 cells/µL [8].

6.4. Immune Humoral Response to Infection in Vaccinated Patients

Seroconversion for IgG typically occurs between days four and seven after symptom onset (median 7.5 days), while IgM/IgA appear between days eight and 11. Antibody titers rise progressively, peaking during the second and third weeks. Neutralizing antibodies become detectable around one week after symptom onset and remain stable for at least 20 days. In a study, IgG/IgM titers in patients treated with antivirals seemed to transiently decline between days 12–15, possibly due to reduced antigen load, though this requires further research. Humoral immune responses do not seem to be significantly altered by HIV status or prior smallpox vaccination [50].

Additional studies indicated that prior smallpox vaccination and mpox infection induce cross-reactive antibodies, with enhanced neutralizing capacity observed in individuals with hybrid immunity. Seroneutralization assays further demonstrated that complement activity augments neutralization against both MVA and MPXV [51].

Large serological analyses including individuals with and without HIV showed comparable antibody levels against vaccinia (A27L, A33R) and mpox (A29L, A35R) antigens among those born before 1981, consistent with waning immunity following cessation of universal smallpox vaccination [53].

Overall, the interplay between viral load dynamics, immune evasion, and host responses determines disease progression, as illustrated in Figure 2.

8. Vaccination and Preventive Strategies in PLWH

Vaccination is central to mpox prevention, particularly for vulnerable groups such as PLWH. Current strategies rely on vaccines originally developed for smallpox. First- and second-generation vaccines (e.g., Dryvax®, ACAM2000®) used live replicating vaccinia virus and carried risks of severe adverse events [70]. Third-generation vaccines, particularly MVA-BN (Imvanex® in Europe, JYNNEOS™ in the U.S., IMVAMUNE® in Canada), contain non-replicating modified vaccinia Ankara and have a favorable safety profile [71,72,73,74]. Regional alternatives include C16-KMB (Japan) and OrthopoxVac (Russia) [75].

Evidence for efficacy is extrapolated from smallpox vaccination (~85% protection) and human and nonhuman primate studies [76,77,78,79,80]. Clinical trials involving >5000 naïve participants confirmed good safety, with fewer adverse events in MVA-BN compared to the ACAM2000® [81]. During the 2022 outbreak, intradermal administration (0.1 mL) was adopted to address shortages, showing comparable immunogenicity to the standard subcutaneous route (0.5 mL) [82,83].

For PLWH, data are encouraging. A U.S. phase II trial showed 80% seroconversion after one dose in antiretroviral therapy (ART)-treated PLWH (CD4 200–750/µL) [84]. Observational studies indicate reduced protection after a single dose of MVA-BN (vaccine effectiveness (VE) ~35% vs. 84% in HIV-negative participants), but robust protection with two doses, with no breakthrough infections reported in fully vaccinated PLWH in one study [85]. Meta-analyses confirm VE of 35–86% and 66–90% after one and two doses, respectively, with outcomes in PLWH broadly comparable to the general population when fully vaccinated [86].

Breakthrough infections and reinfections have been reported both in people with and without HIV infection, typically milder than primary infections, with lower hospitalization and fewer mucosal lesions [87]. Most occurred 6–9 months after vaccination, suggesting waning immunity [88]. Animal and human studies support consideration of booster doses at 2–3 years after vaccination, particularly for high-risk groups such as MSM with multiple partners, sex workers, and travelers to endemic regions [88,89,90,91].

Vaccine uptake and willingness remain challenges. While willingness among MSM seems to be as high as 77% in some studies, it may show variability in different settings that provide care for PLWH, influenced by personal concerns about vaccine safety, perception of risk, access to health services, engagement in high-risk sexual exposure, mpox risk awareness and knowledge about the [92]. Real-world uptake appears to be lower, with a systematic review estimating only 35.7% among PLWH [93]. Of note, during the 2022 outbreak, mpox prevention strategies were hindered by vaccine shortage and available vaccines, until very recently, were not available in many African countries. Addressing stigma, misinformation, and access barriers is essential to maximize protection.

Beyond vaccination, innovative preventive strategies such as wastewater surveillance and community-based interventions (e.g., partnerships with Non-Governmental Organizations, dating apps, and venues) have proven valuable in early detection and targeted risk communication [94,95,96,97].

9. Public Health Implications

The overlapping epidemiology of mpox and HIV underscores the need for integrated approaches to surveillance, prevention, and care. PLWH, particularly those with advanced immunosuppression, face a disproportionate burden of severe disease, hospitalization, and mortality, making them a priority group for clinical and public health interventions.

Early recognition and prompt diagnosis are critical to mitigate severe outcomes, especially in immunocompromised patients who may present atypically. Integration of HIV and mpox services, including testing, vaccination, antiviral access, and follow-up, can improve outcomes and reduce delays in care [34].

At the prevention level, equitable access to vaccination is essential. While MVA-BN has demonstrated safety and immunogenicity in PLWH, reduced effectiveness after a single dose highlights the importance of completing two-dose schedules and considering boosters in high-risk groups [85]. Addressing barriers such as stigma, misinformation, and structural inequities will be key to improving vaccine uptake and trust among vulnerable populations.

Genomic surveillance must also be strengthened, particularly in endemic regions of Africa where HIV and mpox co-circulate and clade I outbreaks continue to drive high morbidity and mortality. Enhanced sequencing, coupled with clinical and immunological data, will be vital to monitor viral evolution in PLWH and to inform treatment and prevention strategies. Complementary tools, such as wastewater monitoring and community-based digital health interventions, can support early outbreak detection and targeted communication [94,95,96,97].

10. Conclusions

Mpox has re-emerged as a global health concern with profound implications for PLWH. Evidence consistently shows that advanced immunosuppression is associated with more severe disease, prolonged viral shedding, and increased risk of hospitalization and death. Antiviral options remain limited, with tecovirimat widely used but lacking robust efficacy data in PLWH, while other therapies require further evaluation. MVA-BN vaccination is safe and immunogenic in this population, but full schedules and, potentially, booster doses are needed to ensure adequate protection.

Addressing the dual burden of mpox and HIV requires integrated prevention and care strategies, equitable access to antivirals and vaccines, and strengthened surveillance, particularly in endemic regions. Including PLWH in clinical trials and genomic studies is essential to close current knowledge gaps. A comprehensive, equity-driven response is critical to reduce disparities in disease outcomes and to improve preparedness for future Orthopoxvirus threats.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.C. and D.P.; Writing—original draft preparation, R.C., J.C., D.S. and D.P.; writing—review and editing, R.C., J.C., D.S. and D.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA, GPT-5 model) exclusively to assist with language editing. Figures were created with the assistance of Claude Pro (Anthropic, San Francisco, CA, USA, model Opus 4.1). All content was reviewed and approved by the authors, who take full responsibility for the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AIDS | Acquired immune deficiency syndrome |

| APOBEC | Apolipoprotein B mRNA Editing Catalytic Polypeptide-like |

| ART | Antiretroviral Therapy |

| CD4 | Cluster of Differentiation 4 |

| CDC | U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CFR | Case fatality rate |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CMV | Cytomegalovirus |

| Ct | Cycle thresholds |

| DRC | Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| HSV | Herpes Simplex Virus |

| IgG | Immunoglobulin G |

| IgM | Immunoglobulin M |

| ITR | Inverted terminal repeats |

| MPXV | monkeypox virus |

| MSM | Men who have sex with men |

| NAAT | Nucleic acid amplification testing |

| NIH OI | U.S. National Institutes of Health Opportunistic Infections |

| NYSDOH | New York State Department of Health |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PLWH | People living with HIV |

| RR | Relative risk |

| STIs | Sexually transmitted infections |

| US | United States |

| VIGIV | Vaccinia Immune Globulin Intravenous |

| VZV | Varicella-Zoster Virus |

| WGS | Whole-genome sequencing |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Antunes, F.; Cordeiro, R.; Virgolino, A. Monkeypox: From a Neglected Tropical Disease to a Public Health Threat. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2022, 14, 772–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitjà, O.; Ogoina, D.; Titanji, B.K.; Galvan, C.; Muyembe, J.-J.; Marks, M.; Orkin, C.M. Monkeypox. Lancet 2023, 401, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Mpox Trends. 28 July 2025. Available online: https://worldhealthorg.shinyapps.io/mpx_global/ (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Weekly Communicable Disease Threats Report, Week 29, 12–18 July 2025. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/communicable-disease-threats-report-12-18-july-2025-week-29 (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Epidemiological Update, 5 April 2024: Outbreak of Mpox Caused by Monkeypox Virus Clade I in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/outbreak-mpox-caused-monkeypox-virus-clade-i-democratic-republic-congo (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Epidemiological Update, 14 January 2025: Mpox Due to Monkeypox Virus Clade I. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/epidemiological-update-14-january-2025-mpox-due-monkeypox-virus-clade-i (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Africa CDC Weekly Event-Based Surveillance Report, March 2024. Available online: https://africacdc.org/download/africa-cdc-weekly-event-based-surveillance-report-march-2024 (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Mitjà, O.; Alemany, A.; Marks, M.; Mora, J.I.L.; Rodríguez-Aldama, J.C.; Silva, M.S.T.; Herrera, E.A.C.; Crabtree-Ramirez, B.; Blanco, J.L.; Girometti, N.; et al. Mpox in People with Advanced HIV Infection: A Global Case Series. Lancet 2023, 401, 939–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, K.G.; Eberly, K.; Russell, O.O.; Snyder, R.E.; Phillips, E.K.; Tang, E.C.; Peters, P.J.; Sanchez, M.A.; Hsu, L.; Cohen, S.E.; et al. HIV and Sexually Transmitted Infections Among Persons with Monkeypox—Eight U.S. Jurisdictions, May 17–July 22, 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 1141–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philpott, D.; Hughes, C.M.; Alroy, K.A.; Kerins, J.L.; Pavlick, J.; Asbel, L.; Crawley, A.; Newman, A.P.; Spencer, H.; Feldpausch, A.; et al. Epidemiologic and Clinical Characteristics of Monkeypox Cases—United States, May 17–July 22, 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 1018–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornhill, J.P.; Barkati, S.; Walmsley, S.; Rockstroh, J.; Antinori, A.; Harrison, L.B.; Palich, R.; Nori, A.; Reeves, I.; Habibi, M.S.; et al. Monkeypox Virus Infection in Humans across 16 Countries—April–June 2022. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 679–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Factsheet for Health Professionals on Mpox. 16 August 2024. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/all-topics-z/monkeypox/factsheet-health-professionals (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Srivastava, S.; Laxmi; Sharma, K.; Sridhar, S.B.; Talath, S.; Shareef, J.; Mehta, R.; Satapathy, P.; Sah, R. Clade Ib: A new emerging threat in the Mpox outbreak. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1504154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beiras, C.G.; Malembi, E.; Escrig-Sarreta, R.; Ahuka, S.; Mbala, P.; Mavoko, H.M.; Subissi, L.; Abecasis, A.B.; Marks, M.; Mitjà, O. Concurrent outbreaks of mpox in Africa-an update. Lancet 2025, 405, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical Considerations for Mpox in Immunocompromised People. September 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mpox/hcp/clinical-care/immunocompromised-people.html (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Di Giulio, D.B.; Eckburg, P.B. Human Monkeypox: An Emerging Zoonosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2004, 4, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, K.; Leggat, P.A. Human Monkeypox: Current State of Knowledge and Implications for the Future. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2016, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, E. What to Know About Monkeypox. JAMA 2022, 327, 2278–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunge, E.M.; Hoet, B.; Chen, L.; Lienert, F.; Weidenthaler, H.; Baer, L.R.; Steffen, R. The Changing Epidemiology of Human Monkeypox—A Potential Threat? A Systematic Review. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antinori, A.; Mazzotta, V.; Vita, S.; Carletti, F.; Tacconi, D.; Lapini, L.E.; D’abramo, A.; Cicalini, S.; Lapa, D.; Pittalis, S.; et al. Epidemiological, Clinical and Virological Characteristics of Four Cases of Monkeypox Support Transmission through Sexual Contact, Italy, May 2022. Eurosurveillance 2022, 27, 2200421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Clinical Management and Infection Prevention Control for Mpox: Living Guideline, May 2025; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez Clemente, N.; Coles, C.; Paixao, E.S.; Brickley, E.B.; Whittaker, E.; Alfven, T.; Rulisa, S.; Higuita, N.A.; Torpiano, P.; Agravat, P.; et al. Paediatric, Maternal, and Congenital Mpox: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2024, 12, e572–e588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosius, I.; Vakaniaki, E.H.; Mukari, G.; Munganga, P.; Tshomba, J.C.; De Vos, E.; Bangwen, E.; Mujula, Y.; Tsoumanis, A.; Van Dijck, C.; et al. Epidemiological and Clinical Features of Mpox during the Clade Ib Outbreak in South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo: A Prospective Cohort Study. Lancet 2025, 405, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugwu, C.L.J.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Wu, J.; Kong, J.D.; Asgary, A.; Orbinski, J.; Woldegerima, W.A. Risk Factors Associated with Human Mpox Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Glob. Health 2025, 10, e016937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Fu, L.; Wang, B.; Sun, Y.; Wu, X.; Peng, X.; Li, Y.; Lin, Y.-F.; Fitzpatrick, T.; Vermund, S.H.; et al. Clinical Characteristics of Human Mpox (Monkeypox) in 2022: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pathogens 2023, 12, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Soto, M.C.; Arroyo-Hernández, H. Epidemiological and Clinical Characteristics of Monkeypox among People with and without HIV in Peru: A National Observational Study. J. Infect. Public Health 2024, 17, 102494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, I.; Ceballos-Liceaga, S.E.; de la Torre, A.; García-Rodríguez, G.; López-Martínez, I.B.; López-Gatell, H.; Mosqueda-Gómez, J.L.; Valdés-Ferrer, S.I. Clinical Features and Outcomes of Mpox in People with and without HIV: A National Comparative Study. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2024, 96, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grau-Echevarría, A.; Blaya-Imbernón, D.; Finello, M.; Zafrilla, E.P.; García, Á.G.; Leal, R.P.; Labrandero-Hoyos, C.; Magdaleno-Tapial, J.; Díez-Recio, E.; Hernández-Bel, P. Atypical Mucocutaneous Manifestations of Mpox: A Systematic Review. J. Dermatol. 2025, 52, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saldana, C.S.; Kelley, C.F.; Aldred, B.M.; Cantos, V.D. Mpox and HIV: A Narrative Review. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2023, 20, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabil, M.; Gaidhane, S.; Roopashree, R.; Kaur, M.; Srivastava, M.; Barwal, A.; Prasad, G.V.S.; Rajput, P.; Syed, R.; Dev, A.; et al. Association of HIV Infection and Hospitalization among Mpox Cases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzam, A.; Khaled, H.; Salem, H.; Ahmed, A.; Heniedy, A.M.; Hassan, H.S.; Hassan, A.; El-Mahdy, T.S. The Impact of Immunosuppression on the Mortality and Hospitalization of Monkeypox: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the 2022 Outbreak. Virol. J. 2024, 21, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, A.M.; Elrosasy, A.; Mahmoud, A.M.; Saed, S.A.A.; Moawad, W.A.E.; Hamouda, E.; Nguyen, D.; Tran, V.P.; Pham, H.T.; Sah, S.; et al. The Effect of HIV and Mpox Co-Infection on Clinical Outcomes: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. HIV Med. 2024, 25, 897–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinnetti, C.; Cimini, E.; Mazzotta, V.; Matusali, G.; Vergori, A.; Mondi, A.; Rueca, M.; Batzella, S.; Tartaglia, E.; Bettini, A.; et al. Mpox as AIDS-Defining Event with a Severe and Protracted Course: Clinical, Immunological, and Virological Implications. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, e127–e135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Integration of HIV and Syphilis Testing Services as Part of Mpox Response: Standard Operating Procedures. March 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240107229 (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- World Health Organization. Diagnostic Testing and Testing Strategies for Mpox: Interim Guidance, 12 November 2024; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro da Silva, S.J.; Kohl, A.; Pena, L.; Pardee, K. Clinical and Laboratory Diagnosis of Monkeypox (Mpox): Current Status and Future Directions. iScience 2023, 26, 106759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.H.; Radecki, P.; Belinky, F.; Bhiman, J.N.; Meiring, S.; Kleynhans, J.; Amoako, D.; Canedo, V.G.; Lucas, M.; Kekana, D.; et al. Rapid Intra-Host Diversification and Evolution of SARS-CoV-2 in Advanced HIV Infection. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaku, N.; Yasugi, M.; Tshibangu-Kabamba, E.; Wakabayashi, Y.; Uesaka, Y.; Nakagama, Y.; Nogimori, T.; Yamamoto, T.; Mbala-Kingebeni, P.; Ngoyi, D.M.; et al. Multiple-Clone Infections of Mpox: Insights from a Single Primary Lesion. CMI Commun. 2024, 1, 105042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vauhkonen, H.; Kallio-Kokko, H.; Hiltunen-Back, E.; Lönnqvist, L.; Leppäaho-Lakka, J.; Mannonen, L.; Kant, R.; Sironen, T.; Kurkela, S.; Lappalainen, M.; et al. Intrahost Monkeypox Virus Genome Variation in Patient with Early Infection, Finland, 2022. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023, 29, 649–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, Á.; Neher, R.A.; Ndodo, N.; Borges, V.; Gannon, B.; Gomes, J.P.; Groves, N.; King, D.J.; Maloney, D.; Lemey, P.; et al. APOBEC3 Deaminase Editing in Mpox Virus as Evidence for Sustained Human Transmission since at Least 2016. Science 2023, 382, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isidro, J.; Borges, V.; Pinto, M.; Sobral, D.; Santos, J.D.; Nunes, A.; Mixão, V.; Ferreira, R.; Santos, D.; Duarte, S.; et al. Phylogenomic Characterization and Signs of Microevolution in the 2022 Multi-Country Outbreak of Monkeypox Virus. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1569–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoa, H.T.T.; Dung, N.T.; Hung, L.M.; Hong, N.T.T.; Quy, V.T.; Thao, N.T.; Duy, N.T.; Truong, H.; Hoang, T.M.; Thanh, N.T.; et al. Emerging Monkeypox Virus Sublineage C.1 Causing Community Transmission, Vietnam, 2023. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2024, 30, 2385–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueca, M.; Tucci, F.G.; Mazzotta, V.; Gramigna, G.; Gruber, C.E.M.; Fabeni, L.; Giombini, E.; Matusali, G.; Pinnetti, C.; Mariano, A.; et al. Temporal Intra-Host Variability of Mpox Virus Genomes in Multiple Body Tissues. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e28791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzón, S.; Varona, S.; Negredo, A.; Vidal-Freire, S.; Patiño-Galindo, J.A.; Ferressini-Gerpe, N.; Zaballos, A.; Orviz, E.; Ayerdi, O.; Muñoz-Gómez, A.; et al. Monkeypox Virus Genomic Accordion Strategies. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taouk, M.L.; Steinig, E.; Taiaroa, G.; Savic, I.; Tran, T.; Higgins, N.; Tran, S.; Lee, A.; Braddick, M.; Moso, M.A.; et al. Intra- and Interhost Genomic Diversity of Monkeypox Virus. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e29029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masirika, L.M.; Udahemuka, J.C.; Schuele, L.; Nieuwenhuijse, D.F.; Ndishimye, P.; Boter, M.; Mbiribindi, J.B.; Kacita, C.; Lang, T.; Gortázar, C.; et al. Epidemiological and Genomic Evolution of the Ongoing Outbreak of Clade Ib Mpox Virus in the Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1459–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Xie, Y.; Guo, J.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Jiang, B.; Wang, J. Single-Cell Sequencing of Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells Reveals Immune Landscape of Monkeypox Patients with HIV. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2025, 14, 2459136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kwon, R.; Lee, H.; Lee, S.W.; Rahmati, M.; Koyanagi, A.; Smith, L.; Kim, M.S.; Sánchez, G.F.L.; Elena, D.; et al. Viral Load Dynamics and Shedding Kinetics of Mpox Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Travel Med. 2023, 30, taad111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salauddin, M.; Zheng, Q.; Murtuza, M.S.; Zheng, C.; Hossain, G. Monkeypox Immunity: A Landscape of Host–Virus Interactions, Vaccination Strategies, and Future Research Horizons. Anim. Zoonoses 2025, 1, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colavita, F.; Matusali, G.; Mazzotta, V.; Bettini, A.; Lapa, D.; Meschi, S.; Francalancia, M.; Pinnetti, C.; Bordi, L.; Mizzoni, K.; et al. Profiling the Acute Phase Antibody Response against Mpox Virus in Patients Infected during the 2022 Outbreak. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e28851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubert, M.; Guivel-Benhassine, F.; Bruel, T.; Porrot, F.; Planas, D.; Vanhomwegen, J.; Wiedemann, A.; Burrel, S.; Marot, S.; Palich, R.; et al. Complement-Dependent Mpox-Virus-Neutralizing Antibodies in Infected and Vaccinated Individuals. Cell Host Microbe 2023, 31, 937–948.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraes-Cardoso, I.; Benet, S.; Carabelli, J.; Perez-Zsolt, D.; Mendoza, A.; Rivero, A.; Alemany, A.; Descalzo, V.; Grifoni, A.; Sette, A.; et al. Immune Responses Associated with Mpox Viral Clearance in Men with and without HIV in Spain: A Multisite, Observational, Prospective Cohort Study. Lancet Microbe 2024, 5, 100859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Wang, H.; Sun, L.; Feng, J.; Li, W.; Cheng, L.; Liao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Ge, X.; et al. Levels of Antibodies against the Monkeypox Virus Compared by HIV Status and Historical Smallpox Vaccinations: A Serological Study. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2024, 13, 2356153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.K.; Schrodt, C.A.; Minhaj, F.S.; Waltenburg, M.A.; Cash-Goldwasser, S.; Yu, Y.; Petersen, B.W.; Hutson, C.; Damon, I.K. Interim Clinical Treatment Considerations for Severe Manifestations of Mpox—United States, February 2023. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). Study of Tecovirimat for Human Monkeypox Virus (STOMP). ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05534984. Updated 10 December 2024. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05534984 (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- ANRS Emerging Infectious Diseases (MPX-RESPONSE). TECOVIRIMAT for Mpox—Primary Clinical Outcome Results from the Randomized Part of the UNITY Clinical Trial. In Proceedings of the IAS 2025, Kigali, Rwanda, 17 July 2025; Trial Summary. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05597735 (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Yu, P.A.; Elmor, R.; Muhammad, K.; Yu, Y.C.; Rao, A.K. Tecovirimat Use under Expanded Access to Treat Mpox in the United States, 2022–2023. NEJM Evid. 2024, 3, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldred, B.; Lyles, R.H.; Scott, J.Y.; Gromer, D.J.; Aldredge, A.; Workowski, K.A.; Wiley, Z.; Titanji, B.K.; Szabo, B.; Sheth, A.N.; et al. Early Tecovirimat Treatment for Mpox Disease among People with HIV. JAMA Intern. Med. 2024, 184, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.G.; Gigante, C.M.; Wynn, N.T.; Matheny, A.; Davidson, W.; Yang, Y.; Condori, R.E.; O’cOnnell, K.; Kovar, L.; Williams, T.L.; et al. Tecovirimat Resistance in Mpox Patients, United States, 2022–2023. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023, 29, 2426–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford, A.; Rimmer, S.; Gilchrist, M.; Sun, K.; Davies, E.P.; Waddington, C.S.; Chiu, C.; Armstrong-James, D.; Swaine, T.; Davies, F.; et al. Use of Cidofovir in a Patient with Severe Mpox and Uncontrolled HIV Infection. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, e218–e226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raccagni, A.A.O.; Candela, C.; Bruzzesi, E.; Mileto, D.; Canetti, D.; Rizzo, A.; Castagna, A.; Nozza, S. Real-Life Use of Cidofovir for the Treatment of Severe Monkeypox Cases. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e28218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehnertz, N.; Babcock, M.; Ruprecht, A.; Griffith, J.; Lynfield, R. 897. Patients with Mpox, Minnesota, 2022. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2023, 10 (Suppl. 2), S489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thet, A.K.; Kelly, P.J.; Kasule, S.N.; Shah, A.K.; Chawala, A.; Latif, A.; Chilimuri, S.S.; Zeana, C.B. The Use of Vaccinia Immune Globulin in the Treatment of Severe Mpox Virus Infection in HIV/AIDS. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 76, 1671–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use of Intravenous Vaccinia Immune Globulin (VIGIV) Under an Expanded Access Investigational New Drug (IND) Protocol for Monkeypox (Mpox) Treatment and Postexposure Prophylaxis. 2025. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mpox/media/pdfs/2024/08/VIGIV-Protocol.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Cinatl, J.; Bechtel, M.; Reus, P.; Ott, M.; Rothweiler, F.; Michaelis, M.; Ciesek, S.; Bojkova, D. Trifluridine for treatment of mpox infection in drug combinations in ophthalmic cell models. J. Med. Virol. 2024, 96, e29354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perzia, B.P.; Cavanaugh, C.; Xiao, Q.; Shin, B.; Jacobi, F. Treatment of ocular-involving monkeypox virus with topical trifluridine and oral tecovirimat in the 2022 outbreak. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 2023, 32, 101891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pi, C.; Adah, O.; Cholli, P.A.; Martines, R.; Abate, G.; Hainaut, L.; Poowanawittayakom, N. Relapsed monkeypox keratitis in advanced HIV infection in St. Louis, Missouri, USA. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2024, 30, 1406–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV: Mpox. 2024. Available online: https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/sites/default/files/guidelines/archive/adult-adolescent-oi-2024-10-08.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- McLean, J.R.; Zucker, J.E.; Vail, R.M.; Shah, S.S.; Fine, S.M.; McGowan, J.P.; Merrick, S.T.; Radix, A.E.; Rodriguez, J.; Norton, B.L.; et al. Prevention and Treatment of Mpox. In New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute Clinical Guidelines; Johns Hopkins University: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Eslami, A.; Alimoghadam, S.; Khoshravesh, S.; Shirani, M.; Alimoghadam, R.; Alavi Darazam, I. Mpox vaccination and treatment: A systematic review. J. Chemother. 2024, 36, 85–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Imvanex. 23 April 2018. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/imvanex (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). EMA Recommends Approval of Imvanex for the Prevention of Monkeypox Disease. 22 July 2022. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/ema-recommends-approval-imvanex-prevention-monkeypox-disease (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Bavarian Nordic A/S. Jynneos—Product Information. 2025. Available online: https://bavariannordic.io/uploads/jynneos-pi.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Bavarian Nordic A/S. Health Canada Extends Approval of IMVAMUNE to Immunization Against Monkeypox and Orthopox Viruses. GlobeNewswire News Room. 12 November 2020. Available online: https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2020/11/12/2125193/0/en/Health-Canada-Extends-Approval-of-IMVAMUNE-to-Immunization-against-Monkeypox-and-Orthopox-Viruses.html (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Pischel, L.; Martini, B.A.; Yu, N.; Cacesse, D.; Tracy, M.; Kharbanda, K.; Ahmed, N.; Patel, K.M.; Grimshaw, A.A.; Malik, A.A.; et al. Vaccine effectiveness of 3rd generation mpox vaccines against mpox and disease severity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine 2024, 42, 126053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Townsend, M.B.; Keckler, M.S.; Patel, N.; Davies, D.H.; Felgner, P.; Damon, I.K.; Karem, K.L. Humoral Immunity to Smallpox Vaccines and Monkeypox Virus Challenge: Proteomic Assessment and Clinical Correlations. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 900–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jezek, Z.; Gromyko, A.I.; Szczeniowski, M.V. Human monkeypox. J. Hyg. Epidemiol. Microbiol. Immunol. 1983, 27, 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Jezek, Z.; Grab, B.; Paluku, K.M.; Szczeniowski, M.V. Human monkeypox: Disease pattern, incidence and attack rates in a rural area of northern Zaire. Trop. Geogr. Med. 1988, 40, 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- UK Health Security Agency. Guidance Smallpox and Mpox: The Green Book. Chapter 29; 2025. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/68483ced944a600f13bcb899/Green-Book-chapter-29_Smallpox-and-mpox_6June2025.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Karem, K.L.; Reynolds, M.; Hughes, C.; Braden, Z.; Nigam, P.; Crotty, S.; Glidewell, J.; Ahmed, R.; Amara, R.; Damon, I.K. Monkeypox-Induced Immunity and Failure of Childhood Smallpox Vaccination To Provide Complete Protection. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2007, 14, 1318–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittman, P.R.; Hahn, M.; Lee, H.S.; Koca, C.; Samy, N.; Schmidt, D.; Hornung, J.; Weidenthaler, H.; Heery, C.R.; Meyer, T.P.; et al. Phase 3 Efficacy Trial of Modified Vaccinia Ankara as a Vaccine against Smallpox. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1897–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). EMA’s Emergency Task Force Advises on Intradermal Use of Imvanex/Jynneos Against Monkeypox. 19 August 2022. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/emas-emergency-task-force-advises-intradermal-use-imvanex-jynneos-against-monkeypox (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Dalton, A.F.; Diallo, A.O.; Chard, A.N.; Moulia, D.L.; Deputy, N.P.; Fothergill, A.; Kracalik, I.; Wegner, C.W.; Markus, T.M.; Pathela, P.; et al. Estimated Effectiveness of JYNNEOS Vaccine in Preventing Mpox: A Multijurisdictional Case-Control Study, United States, August 19, 2022–March 31, 2023. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overton, E.T.; Stapleton, J.; Frank, I.; Hassler, S.; Goepfert, P.A.; Barker, D.; Wagner, E.; Von Krempelhuber, A.; Virgin, G.; Weigl, J.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of Modified Vaccinia Ankara-Bavarian Nordic Smallpox Vaccine in Vaccinia-Naive and Experienced Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected Individuals: An Open-Label, Controlled Clinical Phase II Trial. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2015, 2, ofv040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillus, D.; Le, N.H.; Tober-Lau, P.; Fietz, A.-K.; Hoffmann, C.; Stegherr, R.; Huang, L.; Baumgarten, A.; Voit, F.; Bickel, M.; et al. Safety and effectiveness of MVA-BN vaccination against mpox in at-risk individuals in Germany (SEMVAc and TEMVAc): A combined prospective and retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 775–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, L.M.K.; Betancur, E.; Riera-Montes, M.; Lienert, F.; Scheele, S. MVA-BN vaccine effectiveness: A systematic review of real-world evidence in outbreak settings. Vaccine 2024, 42, 126409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucker, J.; McLean, J.; Huang, S.; DeLaurentis, C.; Gunaratne, S.; Stoeckle, K.; Glesby, M.J.; Wilkin, T.J.; Fischer, W.; Damon, I.; et al. Development and Pilot of an Mpox Severity Scoring System. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 229 (Suppl. 2), S229–S233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guagliardo, S.A.J.; Kracalik, I.; Carter, R.J.; Braden, C.; Free, R.; Hamal, M.; Tuttle, A.; McCollum, A.M.; Rao, A.K. Monkeypox Virus Infections After 2 Preexposure Doses of JYNNEOS Vaccine, United States, May 2022–May 2024. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2024, 73, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earl, P.L.; Americo, J.L.; Wyatt, L.S.; Eller, L.A.; Montefiori, D.C.; Byrum, R.; Piatak, M.; Lifson, J.D.; Amara, R.R.; Robinson, H.L.; et al. Recombinant modified vaccinia virus Ankara provides durable protection against disease caused by an immunodeficiency virus as well as long-term immunity to an orthopoxvirus in a non-human primate. Virology 2007, 366, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Leeuwen, L.P.; Shamier, M.C.; Verstrepen, B.E.; Götz, H.M.; Schmitz, K.S.; Akhiyate, N.; Wijnans, K.; Bogers, S.; E van Royen, M.; van Gorp, E.C.; et al. Orthopoxvirus-specific antibodies wane to undetectable levels 1 year after MVA-BN vaccination of at-risk individuals, the Netherlands, 2022–2023. Eurosurveillance 2024, 29, 2400575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haute Autorité de Santé. Avis n° 2024.0058/AC/SESPEV du 29 Août 2024 du Collège de la Haute Autorité de Santé Relatif à la Stratégie de Vaccination Contre le Mpox. 2024. Available online: https://www.has-sante.fr/upload/docs/application/pdf/2024-08/avis_2024.0058.ac.sespev_du_29_aout_2024_du_college_de_la_has_relatif_a_la_strategie_de_vaccination__2024-08-30_16-13-45_323.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Liu, J.; Liu, S.; Yu, S.; Du, X.; Hao, J.; Hui, R.; Buh, A.; Chen, W.; Chen, J. Willingness to receive mpox vaccine among men who have sex with men: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulaiman, S.K.; Isma’il Tsiga-Ahmed, F.; Musa, M.S.; Makama, B.T.; Sulaiman, A.K.; Abdulaziz, T.B. Global prevalence and correlates of mpox vaccine acceptance and uptake: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Commun. Med. 2024, 4, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, B. What poo tells us: Wastewater surveillance comes of age amid covid, monkeypox, and polio. BMJ 2022, 378, o1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfe, M.K.; Yu, A.T.; Duong, D.; Rane, M.S.; Hughes, B.; Chan-Herur, V.; Donnelly, M.; Chai, S.; White, B.J.; Vugia, D.J.; et al. Use of Wastewater for Mpox Outbreak Surveillance in California. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 570–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wurtzer, S.; Levert, M.; Dhenain, E.; Boni, M.; Tournier, J.N.; Londinsky, N.; Lefranc, A.; Sig, O.; Ferraris, O.; Moulin, L. First Detection of Monkeypox Virus Genome in Sewersheds in France: The Potential of Wastewater-Based Epidemiology for Monitoring Emerging Disease. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2022, 9, 991–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia Iglesias, J.; Williams, J.; Nagington, M.; May, T.; Buijsen, S.; McHugh, C.; Horwood, J.; Pickersgill, M.; Chataway, J.; Amlôt, R. Responding to Mpox: Communities, Communication, and Infrastructures; University College London: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://theippo.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Responding-to-Mpox.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).