The Highly Interrelated Morbidity Respiratory Viruses Cause Among Humans and Animals in Mongolia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Team and Screening Process

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

- Publications reporting data on respiratory viruses circulating in Mongolia.

- Records involving humans, animals, or both.

- Publications written in English and accessible in full text.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

- Studies unrelated to Mongolia or that did not include Mongolian data.

- Documents that did not involve any of the six viral families.

- Conference abstracts without full text, commentaries, news articles, and editorials.

- Non-English sources or reports lacking accessible full text.

- Studies focusing solely on non-respiratory pathogens.

3. Results

3.1. Orthomyxiviridae

3.1.1. Impact of Influenza on Mongolia’s Human Population

3.1.2. Epidemiology

3.1.3. Virus Types and Subtypes

3.1.4. Surveillance Data and Outbreaks

3.1.5. Public Health Interventions

3.1.6. Influenza’s Impact upon Mongolia’s Animal Population

- Domestic animals

- 2.

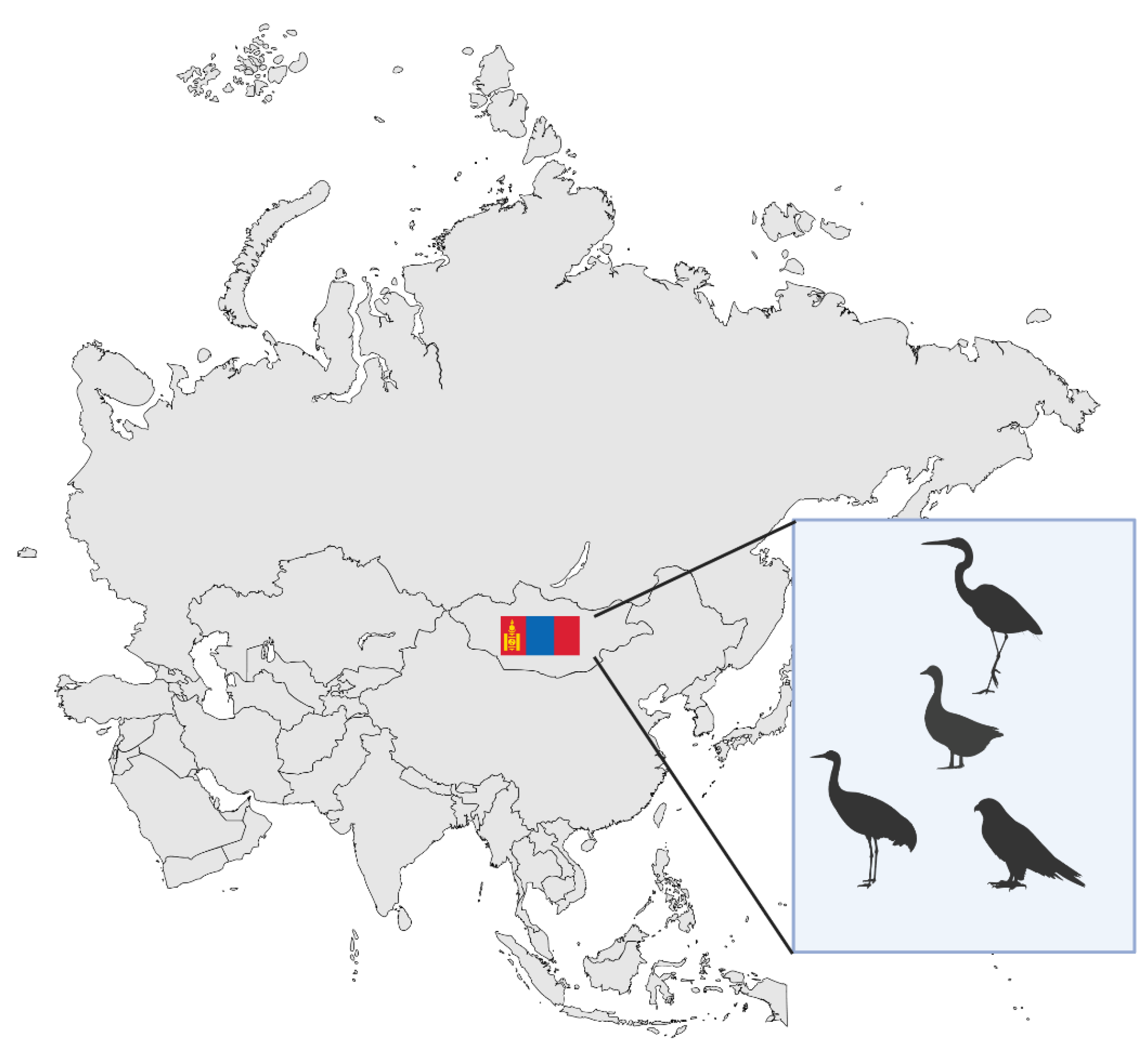

- Wild birds and wildlife

- 3.

- Zoonotic interfaces and spillover risks.

3.1.7. Epidemiology

- Transmission pathways

- 2.

- Geographical and seasonal patterns

- 3.

- Environmental and ecological factors

- 4.

- Virus types and subtypes relevant to Mongolia

3.1.8. Surveillance Data and Outbreaks

3.1.9. Animal Health Interventions

3.2. Coronaviridae

3.2.1. Epidemiology

- Transmission routes

- 2.

- Vulnerable groups and risk

- 3.

- Vaccination and immunity

- 4.

- Social and behavioral influences

- 5.

- Diagnostic capabilities and laboratory gaps

3.2.2. Surveillance Data and Outbreaks

- National seroprevalence surveillance efforts

- 2.

- Genomic surveillance

- 3.

- Surveillance capacity

- 4.

- National diagnostic preparedness

3.2.3. Public Health Interventions

- Initial government actions and preparedness

- 2.

- National surveillance and mass testing.

- 3.

- Vaccine procurement

- 4.

- Vaccine hesitancy

- 5.

- Environmental and economic observations

3.2.4. Impact upon Mongolia’s Animal Population

- Domestic animals

- 2.

- Wild animals

3.2.5. Epidemiology

3.2.6. Virus Types and Subtypes Relevant to Mongolia

- Surveillance data and outbreaks

- 2.

- Animal health interventions

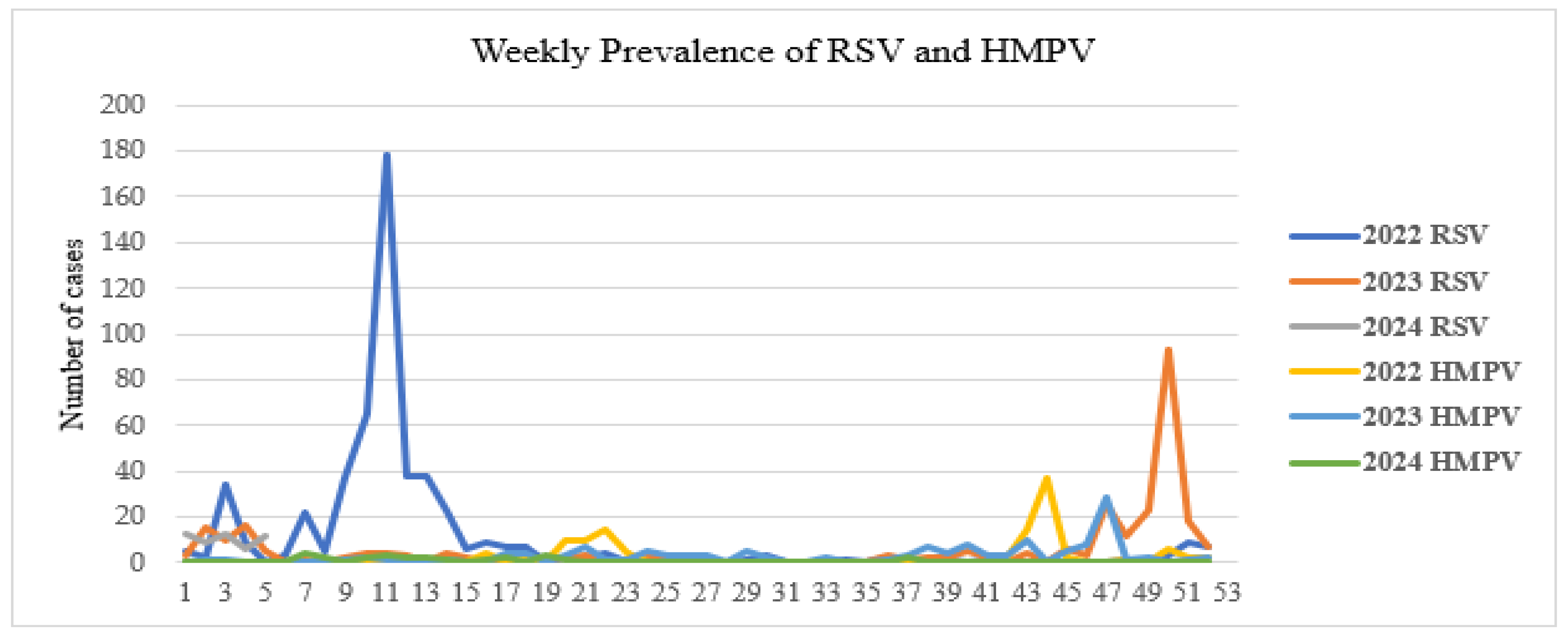

3.3. Pneumoviridae

3.3.1. Impact of RSV on Mongolia’s Human Populations

3.3.2. Epidemiology

3.3.3. Virus Types and Subtypes

3.3.4. Surveillance Data and Outbreaks

3.3.5. Public Health Interventions

3.3.6. Animal Diseases

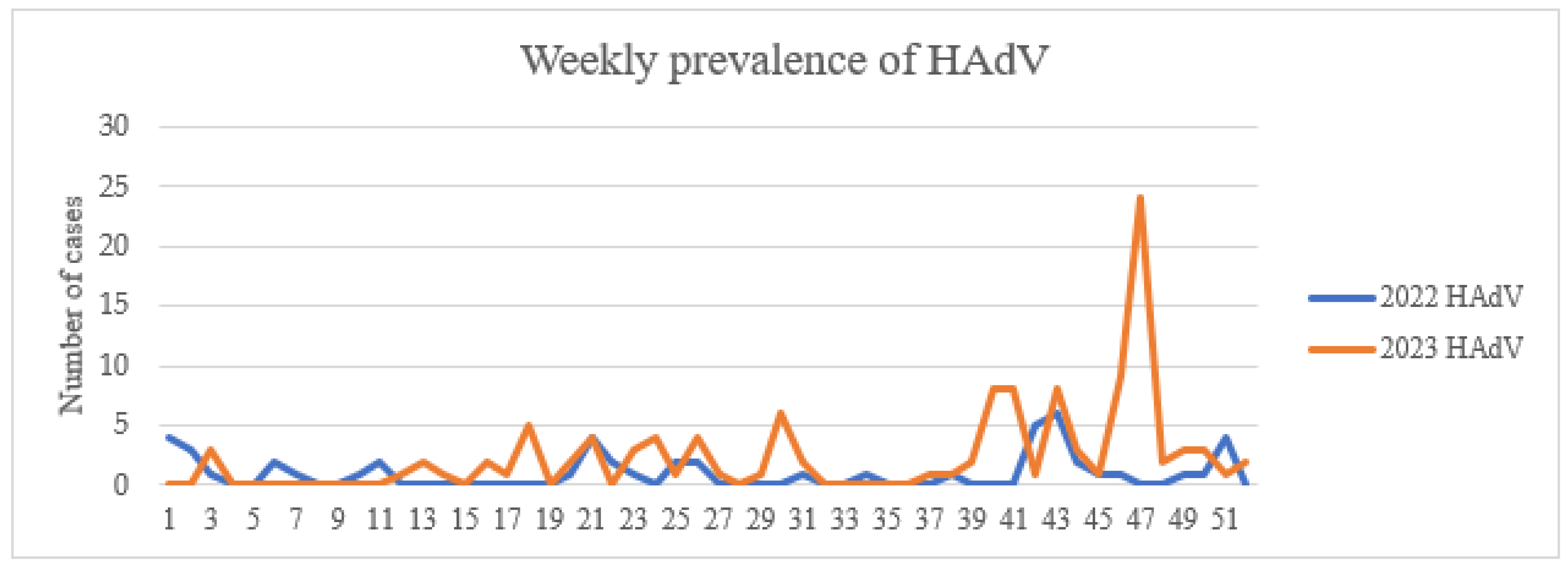

3.4. Adenoviridae

3.4.1. Impact of HAdV on Mongolia’s Human Population and Epidemiology

3.4.2. Virus Types and Subtypes

3.4.3. Surveillance Data and Outbreaks

3.4.4. Public Health Interventions

3.4.5. Animal Diseases

3.5. Paramyxoviridae

3.5.1. Impact upon Mongolia’s Human Populations

- Epidemiology in human populations

- 2.

- Virus types and subtypes relevant to Mongolia

- 3.

- Surveillance data and outbreaks

- 4.

- Public health interventions

3.5.2. Impact upon Mongolia’s Animal Population

- Epidemiology in animal populations

- 2.

- Virus types and subtypes relevant to Mongolia’s animal population

- 3.

- Surveillance data and outbreaks

- 4.

- Animal health interventions

3.6. Picornaviridae

3.6.1. Impact upon Mongolia’s Human Populations

3.6.2. Epidemiology

3.6.3. Virus Types and Subtypes Relevant to Mongolia

3.6.4. Surveillance Data and Outbreaks

3.6.5. Public Health Interventions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

| MERS-CoV | Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus |

| EIV | Equine influenza virus |

| BCoV | Bovine coronavirus |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| HAdV | Human adenovirus |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

| UNDP | United Nations Development Programme |

| UN-Habitat | United Nations Human Settlements Programme |

| HPIV | Human parainfluenza virus |

| ILI | Influenza-like-illness |

| SARI | Severe acute respiratory infection |

| RSV | Respiratory syncytial virus |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| HMPV | Human metapneumovirus |

| AIVs | Avian influenza viruses |

| LPAIVs | Low-pathogenicity avian influenza viruses |

| HPAIVs | Highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses |

| HPAI | Highly pathogenic avian influenza |

| ODOT | One door-one test |

| NDV | Newcastle Disease Virus |

| APMV | Avian Paramyxovirus |

| PPRV | Peste des Petits Ruminants Virus |

References

- Bender, R.G.; Sirota, S.B.; Swetschinski, L.R.; Dominguez, R.M.V.; Novotney, A.; Wool, E.E.; Ikuta, K.S.; Vongpradith, A.; Rogowski, E.L.B.; Doxey, M.; et al. Global, regional, and national incidence and mortality burden of non-COVID-19 lower respiratory infections and aetiologies, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 974–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troeger, C.; Blacker, B.; Khalil, I.A.; Rao, P.C.; Cao, J.; Zimsen, S.R.; Albertson, S.B.; Deshpande, A.; Farag, T.; Abebe, Z.; et al. Estimates of the global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of lower respiratory infections in 195 countries, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 1191–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D.; Karim, S.S.A.; Aknin, L.; Allen, J.; Brosbøl, K.; Colombo, F.; Barron, G.C.; Espinosa, M.F.; Gaspar, V.; Gaviria, A.; et al. The Lancet Commission on lessons for the future from the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Comm. 2022, 400, 1224–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moynihan, R.; Sanders, S.; Michaleff, Z.A.; Scott, A.M.; Clark, J.; To, E.J.; Jones, M.; Kitchener, E.; Fox, M.; Johansson, M.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on utilisation of healthcare services: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e045343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haldane, V.; De Foo, C.; Abdalla, S.M.; Jung, A.-S.; Tan, M.; Wu, S.; Chua, A.; Verma, M.; Shrestha, P.; Singh, S.; et al. Health systems resilience in managing the COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons from 28 countries. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 964–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN Country Team. UN Mongolia Annual Results Report 2024. 2024. Available online: https://mongolia.un.org/en/295166-un-mongolia-annual-results-report-2024 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Sack, A.; Daramragchaa, U.; Chuluunbaatar, M.; Gonchigoo, B.; Bazartseren, B.; Tsogbadrakh, N.; Gray, G.C. Low Prevalence of Enzootic Equine Influenza Virus among Horses in Mongolia. Pathogens 2017, 6, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, M.; Jambal, L.; Karesh, W.B.; Fine, A.; Shiilegdamba, E.; Dulam, P.; Sodnomdarjaa, R.; Ganzorig, K.; Batchuluun, D.; Tseveenmyadag, N.; et al. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Virus among Wild Birds in Mongolia. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e44097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiengprugsawan, V.S.; Dorj, G.; Dracakis, J.G.; Batkhorol, B.; Lkhagvaa, U.; Battsengel, D.; Ochir, C.; Naidoo, N.; Kowal, P.; Cumming, R.G. Disparities in outpatient and inpatient utilization by rural-urban areas among older Mongolians based on a modified WHO-SAGE instrument. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooluun, B. Mongolia Counts 64.7 Million Head of Livestock. Available online: https://montsame.mn/en/read/335867 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Huang, C.Y.; Su, S.B.; Chen, K.-T. Surveillance strategies for SARS-CoV-2 infections through one health approach. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Li, K.; Xiao, S.; Hu, J.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, S.; Wang, W.; Hong, J.; Zhao, Z.; et al. Global epidemiology of animal influenza infections with explicit virus subtypes until 2016: A spatio-temporal descriptive analysis. One Health 2023, 16, 100514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, T.P.; Moncla, L.; Dudas, G.; VanInsberghe, D.; Sukhova, K.; Lloyd-Smith, J.O.; Worobey, M.; Lowen, A.C.; Nelson, M.I. The global H5N1 influenza panzootic in mammals. Nat. Perspect. 2024, 637, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Wang, L.F.; Sun, B.-W.; Wan, W.-B.; Ji, X.; Baele, G.; Bi, Y.-H.; Suchard, M.A.; Lai, A.; Zhang, M.; et al. Zoonotic infections by avian influenza virus: Changing global epidemiology, investigation, and control. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, e522–e531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nerpel, A.; Käsbohrer, A.; Walzer, C.; Desvars-Larrive, A. Data on SARS-CoV-2 events in animals: Mind the gap! One Health 2023, 17, 100653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yondon, M.; Zayat, B.; Nelson, M.I.; Heil, G.L.; Anderson, B.D.; Lin, X.; Halpin, R.A.; McKenzie, P.P.; White, S.K.; Wentworth, D.E.; et al. Equine Influenza A(H3N8) Virus Isolated from Bactrian Camel, Mongolia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20, 2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, S.M.; Damdinjav, B.; Perera, R.A.; Chu, D.K.; Khishgee, B.; Enkhbold, B.; Poon, L.L.; Peiris, M. Absence of MERS-Coronavirus in Bactrian Camels, Southern Mongolia, November 2014. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015, 21, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, L.A.H.; Tsedenbal, N.; Khishigmunkh, C.; Tserendulam, B.; Altanbumba, L.; Luvsantseren, D.; Ulziibayar, M.; Suuri, B.; Narangerel, D.; Tsolmon, B.; et al. Respiratory Syncytial Virus and Influenza Infections in Children in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, 2015–2021. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2024, 18, e13303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmaa, O.; Burmaa, A.; Gantsooj, B.; Darmaa, B.; Nymadawa, P.; Sullivan, S.G.; Fielding, J.E. Influenza epidemiology and burden of disease in Mongolia, 2013–2014 to 2017–2018. West. Pac. Surveill. Response J. 2021, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF-Mongolia’s Air Pollution Is a Child Health Crisis. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/eap/press-releases/mongolias-air-pollution-child-health-crisis (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Batsukh, Z.; Tsolmon, B.; Otgonbaatar, D.; Undraa, B.; Dolgorkhand, A.; Ariuntuya, O. One Health in Mongolia. In One Health: The Human-Animal-Environment Interfaces in Emerging Infectious Diseases; Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, E.S.; Fieldhouse, J.K.; Choi, J.Y.; Gray, G.C. A Mini Review of the Zoonotic Threat Potential of Influenza Viruses, Coronaviruses, Adenoviruses, and Enteroviruses. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, G.C.; Robie, E.R.; Studstill, C.J.; Nunn, C.L. Mitigating Future Respiratory Virus Pandemics: New Threats and Approaches to Consider. Viruses 2021, 13, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Types of Influenza Viruses. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/viruses-types.html (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Baigalmaa, J.; Tuul, T.; Darmaaa, B.; Soyolmaaa, E. Analysis of fatal outcomes from influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 in Mongolia. West. Pac. Surveill. Response J. 2012, 3, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Nukiwa, N.; Burmaa, A.; Kamigaki, T.; Darmaa, B.; Od, J.; Od, I.; Gantsooj, B.; Naranzul, T.; Tsatsral, S.; Enkhbaatar, L.; et al. Evaluating influenza disease burden during the 2008–2009 and 2009–2010 influenza seasons in Mongolia. West. Pac. Surveill. Response J. 2011, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmaa, A.; Kamigaki, T.; Darmaa, B.; Nymadawa, P.; Oshitani, H. Epidemiology and impact of influenza in Mongolia, 2007–2012. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2012, 8, 530–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nukiwa-Souma, N.; Burmaa, A.; Kamigaki, T.; Od, I.; Bayasgalan, N.; Badarchiin Darmaa, A.S.; Nymadawa, P.; Oshitani, H. Influenza Transmission in a Community during a Seasonal Influenza A(H3N2) Outbreak (2010–2011) in Mongolia: A Community-Based Prospective Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Lin, Y.; Tsogtbayar, O.; Khuyagaa, S.-O.; Khurelbaatar, E.; Galsuren, J.; Prox, L.; Zhanga, S.; Tighe, R.M.; Gray, G.C.; et al. Interactive effects of air pollutants and viral exposure on daily influenza hospital visits in Mongolia. Environ. Res. 2024, 268, 120743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsedenbal, N.; Tsend-Ayush, A.; Badarch, D.; Jav, S.; Pagbajab, N. Influenza B viruses circulated during last 5 years in Mongolia. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burmaa, A.; Tsatsral, S.; Odagiri, T.; Suzuki, A.; Oshitani, H.; Nymadawaa, P. Cumulative incidence of pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 by a community-based serological cohort study in Selenghe Province, Mongolia. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2012, 6, e97–e104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anchlan, D.; Ludwig, S.; Nymadawa, P.; Mendsaikhan, J.; Scholtissek, C. Previous H1N1 influenza A viruses circulating in the Mongolian population. Arch. Virol. 1996, 141, 1553–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krylov, V.F.; Obrosova-Serova, N.P.; Žilina, N.N.; Evstigneeva, N.A.; Molibog, E.V.; Zakstel’skaja, L.J.; Kupul, A.; Cerenčimed, O.; Hišigdorž, A. Clinical and epidemiological features of an outbreak of influenza in Ulan Bator in 1971. Bull. World Health Organ. 1973, 49, 567. [Google Scholar]

- Chaw, L.; Kamigaki, T.; Burmaa, A.; Urtnasan, C.; Od, I.; Nyamaa, G.; Nymadawa, P.; Oshitani, H. Burden of Influenza and Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection in Pregnant Women and Infants Under 6 Months in Mongolia: A Prospective Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yondon, M.; Heil, G.L.; Burks, J.P.; Zayat, B.; Waltzek, T.B.; Jamiyan, B.-O.; McKenzie, P.P.; Krueger, W.S.; Friary, J.A.; Gray, G.C. Isolation and characterization of H3N8 equine influenza A virus associated with the 2011 epizootic in Mongolia. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2013, 7, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakoda, Y.; Sugar, S.; Batchluun, D.; Erdene-Ochir, T.-O.; Okamatsu, M.; Isoda, N.; Soda, K.; Takakuwa, H.; Tsuda, Y.; Yamamoto, N.; et al. Characterization of H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza virus strains isolated from migratory waterfowl in Mongolia on the way back from the southern Asia to their northern territory. Virology 2010, 406, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motoshima, M.; Okamatsu, M.; Asakura, S.; Kuribayashi, S.; Sengee, S.; Batchuluun, D.; Ito, M.; Maeda, Y.; Eto, M.; Sakoda, Y.; et al. Antigenic and genetic analysis of H3N8 influenza viruses isolated from horses in Japan and Mongolia, and imported from Canada and Belgium during 2007–2010. Arch. Virol. 2011, 156, 1379–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.M.; Batchuluun, D.; Kim, M.-C.; Choi, J.-G.; Erdene-Ochir, T.-O.; Paek, M.-R.; Sugir, T.; Sodnomdarjaa, R.; Kwon, J.-H. Genetic analyses of H5N1 avian influenza virus in Mongolia, 2009 and its relationship with those of eastern Asia. Vet. Microbiol. 2011, 147, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulaankhuu, A.; Bazarragchaa, E.; Okamatsu, M.; Hiono, T.; Bodisaikhan, K.; Amartuvshin, T.; Tserenjav, J.; Urangoo, T.; Buyantogtokh, K.; Matsuno, K.; et al. Genetic and antigenic characterization of H5 and H7 avian influenza viruses isolated from migratory waterfowl in Mongolia from 2017 to 2019. Virus Genes 2020, 56, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.; Otgontogtokh, N.; Lee, D.-H.; Davganyam, B.; Lee, S.-H.; Cho, A.Y.; Tseren-Ochir, E.-O.; Song, C.-S. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Clade 2.3.4.4 Subtype H5N6 Viruses Isolated from Wild Whooper Swans, Mongolia, 2020. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankhanbaatar, U.; Sainnokhoi, T.; Settypalli, T.B.; Datta, S.; Gombo-Ochir, D.; Khanui, B.; Dorj, G.; Basan, G.; Cattoli, G.; Dundon, W.G.; et al. Isolation and Identification of a Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5N6 Virus from Migratory Waterfowl in Western Mongolia. J. Wildl. Dis. 2022, 58, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajihara, M.; Sakoda, Y.; Soda, K.; Minari, K.; Okamatsu, M.; Takada, A.; Kida, H. The PB2, PA, HA, NP, and NS genes of a highly pathogenic avian influenza virus A/whooper swan/Mongolia/3/2005 (H5N1) are responsible for pathogenicity in ducks. Virol. J. 2013, 10, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soilemetzidou, E.S.; de Bruin, E.; Eschke, K.; Azab, W.; Osterrieder, N.; Czirják, G.Á.; Buuveibaatar, B.; Kaczensky, P.; Koopmans, M.; Walzere, C.; et al. Bearing the brunt: Mongolian khulan (Equus hemionus hemionus) are exposed to multiple influenza A strains. Vet. Microbiol. 2020, 242, 108605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurelbaatar, N.; Krueger, W.S.; Heil, G.L.; Darmaa, B.; Ulziimaa, D.; Tserennorov, D.; Baterdene, A.; Anderson, B.D.; Gray, G.C. Sparse evidence for equine or avian influenza virus infections among Mongolian adults with animal exposures. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2013, 7, 1246–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khurelbaatar, N.; Krueger, W.S.; Heil, G.L.; Darmaa, B.; Ulziimaa, D.; Tserennorov, D.; Baterdene, A.; Anderson, B.D.; Gray, G.C. Little Evidence of Avian or Equine Influenza Virus Infection among a Cohort of Mongolian Adults with Animal Exposures, 2010–2011. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damdinjav, B.; Raveendran, S.; Mojsiejczuk, L.; Ankhanbaatar, U.; Yang, J.; Sadeyen, J.-R.; Iqbal, M.; Perez, D.R.; Rajao, D.S.; Park, A.; et al. Evidence of Influenza A(H5N1) Spillover Infections in Horses, Mongolia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2025, 31, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkhasbaatar, A.; Gilbert, M.; Fine, A.E.; Shiilegdamba, E.; Damdinjav, B.; Buuveibaatar, B.; Khishgee, B.; Johnson, C.K.; Leung, C.Y.H.; Ankhanbaatar, U.; et al. Ecological characterization of 175 low-pathogenicity avian influenza viruses isolated from wild birds in Mongolia, 2009–2013 and 2016–2018. Vet. Med. Sci. 2022, 9, 2676–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.M.; Tseren Ochir, E.O.; Heo, G.-B.; An, S.-H.; Dondog, U.; Myagmarsuren, T.; Lee, Y.-J.; Lee, K.-N. Surveillance and Genetic Analysis of Low-Pathogenicity Avian Influenza Viruses Isolated from Feces of Wild Birds in Mongolia, 2021 to 2023. Animals 2024, 14, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Meng, W.; Liu, D.; Yang, Q.; Chen, L.; Dai, Q.; Ma, T.; Gao, R.; Ru, W.; Li, Y.; et al. Migratory Whooper Swans Cygnus cygnus Transmit H5N1 Virus between China and Mongolia: Combination Evidence from Satellite Tracking and Phylogenetics Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamnikova, S.S.; Mandler, J.; Bekh-Ochir, Z.H.; Dachtzeren, P.; Ludwig, S.; Lvov, D.K.; Scholtissek, C. A Reassortant H1N1 Influenza A Virus Caused Fatal Epizootics among Camels in Mongolia. Virology 1993, 197, 558–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishtiaq, F.; Gilbert, M.; Brown, J.; Joyner, P.; Sodnomdarjaa, R.; Luttrell, M.P.; Stallknecht, D.; Joly, D.O. Antibodies to Influenza A Virus in Wild Birds across Mongolia, 2006–2009. J. Wildl. Dis. 2012, 48, 768–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamendin, K.; Kydyrmanov, A.; Kasymbekov, Y.; Khan, E.; Daulbayeva, K.; Asanova, S.; Zhumatov, K.; Seidalina, A.; Sayatov, M.; Fereidouni, S.R. Continuing evolution of equine influenza virus in Central Asia, 2007–2012. Arch. Virol. 2014, 159, 2321–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, B.T.; Than, D.D.; Ankhanbaatar, U.; Gombo-Ochir, D.; Shura, G.; Tsolmon, A.; Mok, C.K.P.; Basan, G.; Yeo, S.J.; Park, H. Assessing potential pathogenicity of novel highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N6) viruses isolated from Mongolian wild duck feces using a mouse model. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2022, 11, 1425–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, M.; Koel, B.F.; Bestebroer, T.M.; Lewis, N.S.; Smith, D.J.; Fouchier, R.A.M. Serological Evidence for Non-Lethal Exposures of Mongolian Wild Birds to Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5N1 Virus. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e113569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharshov, K.; Sivay, M.; Liu, D.; Pantin-Jackwood, M.; Marchenko, V.; Durymanov, A.; Alekseev, A.; Damdindorj, T.; Gao, G.F.; Swayne, D.E.; et al. Molecular characterization and phylogenetics of a reassortant H13N8 influenza virus isolated from gulls in Mongolia. Virus Genes 2014, 49, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, P.C.; De Groot, R.J.; Haagmans, B.; Lau, S.K.; Neuman, B.W.; Perlman, S.; Sola, I.; Van Der Hoek, L.; Wong, A.C.; Yeh, S.H. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Coronaviridae 2023. J. Gen. Virol. 2023, 104, 1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chimeddorj, B.; Mandakh, U.; Le, L.V.; Bayartsogt, B.; Deleg, Z.; Enebish, O.; Altanbayar, O.; Magvan, B.; Gantumur, A.; Byambaa, O.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in Mongolia: Results from a national population survey. Lancet Reg. Health—West. Pac. 2021, 17, 100317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erkhembayar, R.; Dickinson, E.; Badarch, D.; Narula, I.; Warburton, D.; Thomas, G.N.; Ochir, C.; Manaseki-Holland, S. Early policy actions and emergency response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Mongolia: Experiences and challenges. Lancet 2020, 8, e1234–e1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chimeddorj, B.; Bailie, C.R.; Mandakh, U.; Price, D.J.; Bayartsog, B.; Meagher, N.; Altanbayar, O.; Magvan, B.; Deleg, Z.; Gantumur, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 seroepidemiology in Mongolia, 2020–2021: A longitudinal national study. Lancet Reg. Health—West. Pac. 2021, 36, 100760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashdorj, N.J.; Dashdorj, N.D.; Mishra, M.; Danzig, L.; Briese, T.; Lipkin, W.I.; Mishra, N. Molecular and Serologic Investigation of the 2021 COVID-19 Case Surge Among Vaccine Recipients in Mongolia. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2148415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batmunkh, B.; Otgonbayar, D.; ShaariiI, S.; Khaidav, N.; Shagdarsuren, O.-E.; Boldbaatar, G.; Danzan, N.-E.; Dashtseren, M.; Unurjargal, T.; Dashtseren, I.; et al. RBD-specific antibody response after two doses of different SARS-CoV-2 vaccines during the mass vaccination campaign in Mongolia. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0295167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashdorj, N.J.; Wirz, O.F.; Röltgen, K.; Haraguchi, E.; Buzzanco, A.S.; Sibai, M.; Wang, H.; Miller, J.A.; Solis, D.; Sahoo, M.K.; et al. Direct comparison of antibody responses to four SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in Mongolia. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 1738–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosbayar, A.; Angarag, N.; Andrade, M.S.; Miller, R. A Cross-sectional Study of Depression, Anxiety and Stress in Mongolians During COVID-19 Lockdowns. J. Health Manag. 2025, 27, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsogbadrakh, B.; Yanjmaa, E.; Badamdorj, O.; Choijiljav, D.; Gendenjamts, E.; Ayush, O.-E.; Pojin, O.; Davaakhuu, B.; Sukhbat, T.; Dovdon, B.; et al. Frontline Mongolian Healthcare Professionals and Adverse Mental Health Conditions During the Peak of COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 800809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turbat, B.; Sharavyn, B.; Tsai, F.-J. Attitudes towards Mandatory Occupational Vaccination and Intention to Get COVID-19 Vaccine during the First Pandemic Wave among Mongolian Healthcare Workers: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 19, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorjdagva, J.; Batbaatar, E.; Kauhanena, J. Mass testing for COVID-19 in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia: “One door-one test” approach. Lancet Reg. Health—West. Pac. 2021, 9, 100149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganbat, G.; Lee, H.; Jo, H.-W.; Jadamba, B.; Karthe, D. Assessment of COVID-19 Impacts on Air Quality in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, Based on Terrestrial and Sentinel-5P TROPOMI Data. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2022, 22, 220196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sereejav, E.; Sandagdorj, A.; Bazarjav, P.; Ganbold, S.; Enkhtuvshin, A.; Tsedenbal, N.; Namuuntsetseg, B.; Chimedregzen, K.; Badarch, D.; Otgonbayar, D.; et al. Antibody responses to mRNA versus non-mRNA COVID vaccines among the Mongolian population. IJID Reg. 2023, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dambadarjaa, D.; Altankhuyag, G.E.; Chandaga, U.; Khuyag, S.-O.; Batkhorol, B.; Khaidav, N.; Dulamsuren, O.; Gombodorj, N.; Dorjsuren, A.; Singh, P.; et al. Factors Associated with COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Mongolia: A Web-Based Cross-Sectional Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erendereg, M.; Tumurbaatar, S.; Byambaa, O.; Enebish, G.; Burged, N.; Khurelsukh, T.; Baatar, N.-E.; Munkhjin, B.; Ulziijargal, J.; Gantumur, A.; et al. Molecular epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 in Mongolia, first experience with nanopore sequencing in lower- and middle-income countries setting. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2023, 11, e1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natoli, L.; Gaysuren, N.; Odkhuu, D.; Bell, V. Mongolia Red Cross Society, influenza preparedness planning and the response to COVID-19: The case for investing in epidemic preparedness. West. Pac. Surveill. Response J. WPSAR 2020, 11, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taichiro Takemura, U.A.; Settypalli, T.B.K.; Purevtseren, D.; Shura, G.; Damdinjav, B.; Ali, H.O.A.B.; Dundon, W.G.; Cattoli, G.; Lamien, C.E. SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Beaver Farm, Mongolia, 2021. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2024, 30, 391–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rima, B.; Collins, P.; Easton, A.; Fouchier, R.; Kurath, G.; Lamb, R.A.; Lee, B.; Maisner, A.; Rota, P. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Pneumoviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 2017, 98, 2912–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarasinghe, G.K.; Ayllon, M.A.; Bao, Y.; Basler, C.F.; Bavari, S.; Blasdell, K.R.; Briese, T.; Brown, P.A.; Bukreyev, A.; Balkema-Buschmann, A.; et al. Taxonomy of the order Mononegavirales: Update 2019. Arch. Virol. 2019, 164, 1967–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langedijk, A.C.; Bont, L.J. Respiratory syncytial virus infection and novel interventions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 734–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mufson, M.A.; Örvell, C.; Rafnar, B.; Norrby, E. Two Distinct Subtypes of Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus. J. Gen. Virol. 1985, 66, 2111–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendry, R.M.; Talis, A.L.; Godfrey, E.; Anderson, L.J.; Fernie, B.F.; McIntosh, K. Concurrent circulation of antigenically distinct strains of respiratory syncytial virus during community outbreaks. J. Infect. Dis. 1986, 153, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piralla, A.; Chen, Z.; Zaraket, H. An update on respiratory syncytial virus. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falsey, A.R.; Hennessey, P.A.; Formica, M.A.; Cox, C.; Walsh, E.E. Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection in Elderly and High-Risk Adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 1749–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zang, N.; Cong, B.; Shi, Y.; Xu, L.; Jiang, M.; Wang, P.; Zou, J.; Zhang, H.; et al. Landscape of respiratory syncytial virus. Chin. Med. J. 2024, 137, 2953–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welliver, R.C. Respiratory syncytial virus and other respiratory viruses. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2003, 22, S6–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbati, F.; Moriondo, M.; Pisano, L.; Calistri, E.; Lodi, L.; Ricci, S.; Giovannini, M.; Canessa, C.; Indolfi, G.; Azzari, C. Epidemiology of Respiratory Syncytial Virus-Related Hospitalization Over a 5-Year Period in Italy: Evaluation of Seasonality and Age Distribution Before Vaccine Introduction. Vaccines 2020, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadha, M.; Hirve, S.; Bancej, C.; Barr, I.; Baumeister, E.; Caetano, B.; Chittaganpitch, M.; Darmaa, B.; Ellis, J.; Fasce, R.; et al. Human respiratory syncytial virus and influenza seasonality patterns-Early findings from the WHO global respiratory syncytial virus surveillance. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2020, 14, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, L.A.H.; Tsedenbal, N.; Khishigmunkh, C.; Tserendulam, B.; Altanbumba, L.; Luvsantseren, D.; Ulziibayar, M.; Suuri, B.; Narangerel, D.; Tsolmon, B.; et al. Impact of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine 13 introduction on severe lower respiratory tract infections associated with respiratory syncytial virus or influenza virus in hospitalized children in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. IJID Reg. 2024, 11, 100357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferella, A.; Streitenberger, N.; Perez Aguirreburualde, M.S.; Dus Santos, M.J.; Fazzio, L.E.; Quiroga, M.A.; Zanuzzi, C.N.; Asin, J.; Carvallo, F.; Mozgovoj, M.V.; et al. Bovine respiratory syncytial virus infection in feedlot cattle cases in Argentina. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2023, 35, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Poel, W.H.M.; Langedijk, J.P.M.; Kramps, J.A.; Middel, W.G.J.; Brand, A.; Van Oirschot, J.T. Bovine respiratory syncytial virus antibodies in non-bovine species. Arch. Virol. 1995, 140, 1549–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucciarone, C.M.; Franzo, G.; Lupini, C.; Alejo, C.T.; Listorti, V.; Mescolini, G.; Brandao, P.E.; Martini, M.; Catelli, E.; Cecchinato, M. Avian Metapneumovirus circulation in Italian broiler farms. Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escobar-Alfonso, S.; Alvarez-Mira, D.M.; Beltran-Leon, M.; Ramirez-Nieto, G.; Gomez, A.P. Avian Metapneumovirus Subtype B Circulation in Poultry and Wild Birds of Colombia. Pathogens 2024, 13, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jirjis, F.F.; Noll, S.L.; Halvorson, D.A.; Nagaraja, K.V.; Shaw, D.P. Pathogenesis of avian pneumovirus infection in turkeys. Vet. Pathol. 2002, 39, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkő, M.; Aoki, K.; Arnberg, N.; Davison, A.J.; Echavarría, M.; Hess, M.; Jones, M.S.; Kaján, G.L.; Kajon, A.E.; Mittal, S.K.; et al. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Adenoviridae 2022. J. Gen. Virol. 2022, 103, 1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghebremedhin, B. Human adenovirus: Viral pathogen with increasing importance. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. 2014, 4, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shieh, W.J. Human adenovirus infections in pediatric population—An update on clinico-pathologic correlation. Biomed. J. 2022, 45, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, L.S.; Taylor, B.; Reimels, W.; Barrett, F.F.; Devincenzo, J.P. Adenovirus 7a: A community-acquired outbreak in a children’s hospital. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2000, 19, 996–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pscheidt, V.M.; Gregianini, T.S.; Martins, L.G.; Veiga, A.B.G.d. Epidemiology of human adenovirus associated with respiratory infection in southern Brazil. Rev. Med. Virol. 2021, 31, e2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.K.; Shimizu, H.; Phan, T.G.; Hayakawa, Y.; Islam, A.; Salim, A.F.M.; Khan, A.R.; Mizuguchi, M.; Okitsu, S.; Ushijima, H. Molecular epidemiology of adenovirus infection among infants and children with acute gastroenteritis in Dhaka City, Bangladesh. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2009, 9, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, H.; Phan, T.G.; Nishimura, S.; Okitsu, S.; Maneekarn, N.; Ushijima, H. An outbreak of adenovirus serotype 41 infection in infants and children with acute gastroenteritis in Maizuru City, Japan. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2007, 7, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ison, M.G. Adenovirus infections in transplant recipients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006, 43, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, B.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Xu, C.; Liao, Y.; Hu, M.; Yang, J.; Lai, S.; Wang, L.; Yang, W. Seasonal association between viral causes of hospitalised acute lower respiratory infections and meteorological factors in China: A retrospective study. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e154–e163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhumbra, N.; Wroblewski, M.E. Adenovirus. Pediatr. Rev. 2010, 31, 173–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lessa, F.C.; Gould, P.L.; Pascoe, N.; Erdman, D.D.; Lu, X.; Bunning, M.L.; Marconi, V.C.; Lott, L.; Widdowson, M.A.; Anderson, L.J.; et al. Health care transmission of a newly emergent adenovirus serotype in health care personnel at a military hospital in Texas, 2007. J. Infect. Dis. 2009, 200, 1759–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, K.L.; Broderick, M.P.; Franklin, S.E.; Blyn, L.B.; Freed, N.E.; Moradi, E.; Ecker, D.J.; Kammerer, P.E.; Osuna, M.A.; Kajon, A.E.; et al. Transmission dynamics and prospective environmental sampling of adenovirus in a military recruit setting. J. Infect. Dis. 2006, 194, 877–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Lu, X.; Erdman, D.D.; Anderson, E.J.; Guzman-Cottrill, J.A.; Kletzel, M.; Katz, B.Z. Identification of adenoviruses in specimens from high-risk pediatric stem cell transplant recipients and controls. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008, 46, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jin, X.-H.; Ishiko, H.; Thanh Ha, N.; Ohguchi, T.; Akanuma, M.; Aoki, K.; Ohno, S. Molecular Epidemiology of Adenoviral Conjunctivitis in Hanoi, Vietnam. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2006, 142, 1064–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Seo, J.W.; Lee, S.K.; Hong, I.H.; Choi, S.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, H.S. Molecular Epidemiology of Adenoviral Keratoconjunctivitis in Korea. Ann. Lab. Med. 2022, 42, 683–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toovey, O.T.R.; Kulkarni, P.; David, J.; Patel, A.; Lai, F.Y.; Burns, J.; Thompson, C.; Ellis, J.; Tang, J.W. An outbreak of adenovirus D8 keratoconjunctivitis in Leicester, United Kingdom, from March to August 2019. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 3969–3973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohma, K.; Bayasgalan, N.; Suzuki, A.; Darma, B.; Oshitani, H.; Nymadawa, P. Detection and serotyping of human adenoviruses from patients with influenza-like illness in mongolia. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2012, 65, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-K.; Choi, J.; Yoon, J.; Jung, J.; Park, J.-Y.; Park, J.; Kim, Y.; Park, J.-Y.; Park, D. Molecular Detection of Equine Adenovirus 1 in Nasal Swabs from Horses in the Republic of Korea. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataseven, V.S.; Oğuzoğlu, T.; Başaran-Karapınar, Z.; Bilge-Dağalp, S. First genetic characterization of equine adenovirus type 1 (EAdV-1) in Turkey. Res. Vet. Sci. 2012, 92, 324–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, H.M.; Mahony, T.J.; Vanniasinkam, T. Genetic characterization of equine adenovirus type 1. Vet. Microbiol. 2012, 155, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Z.; Huang, R.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.; Xu, L.; Gao, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, Q. Fowl Adenovirus Serotype 4 Influences Arginine Metabolism to Benefit Replication. Avian Dis. 2020, 64, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, S.; Yang, J.; Tang, Y.; Diao, Y. Pathogenicity of fowl adenovirus serotype 4 (FAdV-4) in chickens. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2019, 75, 104017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balboni, A.; Terrusi, A.; Urbani, L.; Troia, R.; Stefanelli, S.A.M.; Giunti, M.; Battilani, M. Canine circovirus and Canine adenovirus type 1 and 2 in dogs with parvoviral enteritis. Vet. Res. Commun. 2022, 46, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hornsey, S.J.; Philibert, H.; Godson, D.L.; Snead, E.C.R. Canine adenovirus type 1 causing neurological signs in a 5-week-old puppy. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rima, B.; Balkema-Buschmann, A.; Dundon, W.G.; Duprex, P.; Easton, A.; Fouchier, R.; Kurath, G.; Lamb, R.; Lee, B.; Rota, P.; et al. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Paramyxoviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 2019, 100, 1593–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- About Human Parainfluenza Viruses (HPIVs). Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/parainfluenza/about/index.html (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Tseren-Ochir, E.O.; Yuk, S.S.; Khishgee, B.; Kwon, J.H.; Noh, J.Y.; Hong, W.T.; Jeong, J.H.; Gwon, G.B.; Jeong, S.; Kim, Y.J.; et al. Molecular Characterization of Avian Paramyxovirus Types 4 and 8 Isolated from Wild Migratory Waterfowl in Mongolia. J. Wildl. Dis. 2018, 54, 342–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruvot, M.; Fine, A.E.; Hollinger, C.; Strindberg, S.; Damdinjav, B.; Buuveibaatar, B.; Chimeddorj, B.; Bayandonoi, G.; Khishgee, B.; Sandag, B.; et al. Outbreak of Peste des Petits Ruminants among Critically Endangered Mongolian Saiga and Other Wild Ungulates, Mongolia, 2016–2017. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duprex, W.P.; Dutch, R.E. Paramyxoviruses: Pathogenesis, Vaccines, Antivirals, and Prototypes for Pandemic Preparedness. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 228 (Suppl. 6), S390–S397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burmaa, A. Disease Burden and Epidemiological Characteristics of Influenza in Mongolia. Tohoku University. 2021. Available online: https://tohoku.repo.nii.ac.jp/records/99488?utm (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Song, Y.; Gong, Y.N.; Chen, K.F.; Smith, D.K.; Zaraket, H.; Bialasiewicz, S.; Tozer, S.; Chan, P.K.; Koay, E.S.; Lee, H.K.; et al. Global epidemiology, seasonality and climatic drivers of the four human parainfluenza virus types. J. Infect. 2025, 90, 106451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shabbir, M.Z.; Nissly, R.H.; Ahad, A.; Rabbani, M.; Chothe, S.K.; Sebastian, A.; Albert, I.; Jayarao, B.M.; Kuchipudi, S.V. Complete Genome Sequences of Three Related Avian Avulavirus 1 Isolates from Poultry Farmers in Pakistan. Genome Announc. 2018, 6, e00361-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, D.J. Newcastle disease and other avian paramyxoviruses. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2000, 19, 443–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, P.; Sreenivasa, B.P.; Barrett, T.; Corteyn, M.; Singh, R.P.; Bandyopadhyay, S.K. Recent epidemiology of peste des petits ruminants virus (PPRV). Vet. Microbiol. 2002, 88, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, X.F.; Fine, A.E.; Pruvot, M.; Njeumi, F.; Walzer, C.; Kock, R.; Shiilegdamba, E. PPR virus threatens wildlife conservation. Science 2018, 362, 165–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, R. Mongolia Investigation of Peste des Petits Ruminants (PPR) Among Wild Animals and Its Potential Impact on the Current PPR Situation in Livestock. 2019. Available online: https://meridian.allenpress.com/jwd/article/54/2/342/194630/Molecular-Characterization-of-Avian-Paramyxovirus (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Sprygin, A.; Sainnokhoi, T.; Gombo-Ochir, D.; Tserenchimed, T.; Tsolmon, A.; Ankhanbaatar, U.; Krotova, A.; Shumilova, I.; Shalina, K.; Prutnikov, P.; et al. Outbreak of peste des petits ruminants in sheep in Mongolia, 2021. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022, 69, 1695–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banyard, A.C.; Parida, S.; Batten, C.; Oura, C.; Kwiatek, O.; Libeau, G. Global distribution of peste des petits ruminants virus and prospects for improved diagnosis and control. J. Gen. Virol. 2010, 91 Pt 12, 2885–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatar, M.; Khanui, B.; Purevtseren, D.; Khishgee, B.; Loitsch, A.; Unger, H.; Settypalli, T.B.K.; Cattoli, G.; Damdinjav, B.; Dundon, W.G. First genetic characterization of peste des petits ruminants virus from Mongolia. Arch. Virol. 2017, 162, 3157–3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benfield, C.T.O.; Hill, S.; Shatar, M.; Shiilegdamba, E.; Damdinjav, B.; Fine, A.; Willett, B.; Kock, R.; Bataille, A. Molecular epidemiology of peste des petits ruminants virus emergence in critically endangered Mongolian saiga antelope and other wild ungulates. Virus Evol. 2021, 7, veab062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Organisation for Animal Health; Food and Agriculture Organization. Global Strategy for the Control and Eradication of PPR. Available online: https://www.woah.org/app/uploads/2021/12/ppr-global-strategy-avecannexes-2015-03-28.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- World Organisation for Animal Health. National Strategy for the Control and Eradication of PPR. Available online: https://www.gf-tads.org/ppr/progress-on-ppr-control-and-eradication-strategy/en/#:~:text=The%20overarching%20PPR%20Global%20Control,official%20WOAH%20PPR%2Dfree%20status (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Zell, R.; Delwart, E.; Gorbalenya, A.E.; Hovi, T.; King, A.M.Q.; Knowles, N.J.; Lindberg, A.M.; Pallansch, M.A.; Palmenberg, A.C.; Reuter, G.; et al. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Picornaviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 2017, 98, 2421–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrenfeld, E.; Domingo, E.; Roos, R.P. The Picornaviruses; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Atmar, R.L.; Piedra, P.A.; Patel, S.M.; Greenberg, S.B.; Couch, R.B.; Glezen, W.P. Picornavirus, the most common respiratory virus causing infection among patients of all ages hospitalized with acute respiratory illness. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 506–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuramitsu, M.; Kuroiwa, C.; Yoshida, H.; Miyoshi, M.; Okumura, J.; Shimizu, H.; Narantuya, L.; Bat-Ochir, D. Non-polio enterovirus isolation among families in Ulaanbaatar and Tov province, Mongolia: Prevalence, intrafamilial spread, and risk factors for infection. Epidemiol. Infect. 2005, 133, 1131–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, E.J.; Kim, Y.I.; Kim, S.Y.; Ahn, S.H.; Lee, H.J.; Suh, B.; Yu, J.; Park, J.; Lee, Y.J.; Jung, E.; et al. A Bivalent Inactivated Vaccine Prevents Enterovirus 71 and Coxsackievirus A16 Infections in the Mongolian Gerbil. Biomol. Ther. 2023, 31, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Tsatsral, S.; Liu, C.; Li, L.; Ren, L.; Xiao, Y.; Xie, Z.; Zhou, H.; Vernet, G.; Nymadawa, P.; et al. Respiratory infection with enterovirus genotype C117, China and Mongolia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20, 1075–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limon, G.; Ulziibat, G.; Sandag, B.; Dorj, S.; Purevtseren, D.; Khishgee, B.; Basan, G.; Bandi, T.; Ruuragch, S.; Bruce, M.; et al. Socio-economic impact of Foot-and-Mouth Disease outbreaks and control measures: An analysis of Mongolian outbreaks in 2017. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2020, 67, 2034–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, A.M.; Tsedenkhuu, P.; Bold, B.; Purevsuren, B.; Bold, D.; Morris, R. Epidemiology of the 2010 Outbreak of Foot-and-Mouth Disease in Mongolia. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2015, 62, e45–e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. About Rhinoviruses. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/rhinoviruses/about/ (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Tsatsral, S.; Xiang, Z.; Fuji, N.; Maitsetseg, C.; Khulan, J.; Oshitani, H.; Wang, J.; Nymadawa, P. Molecular Epidemiology of the Human Rhinovirus Infection in Mongolia during 2008–2013. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2015, 68, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

| Viral Family | Human Viruses | Animal Viruses |

|---|---|---|

| Orthomyxoviridae | Influenza A (H1N1), A (H1N1) pdm09, A (H3N2), Influenza B/Victoria, B/Yamagata | Equine influenza A (H3N8), reassortant H1N1 (camel), highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (H5N1, H5N6, H5N8), low pathogenic avian influenza subtypes (H1N1, H2N3, H3N6, H3N8, H4N6, H5N3, H6N1, H7N3, H7N7, H8N4, H10N7, H12N3, H13N6, H13N8, H16N3) |

| Coronaviridae | SARS-CoV-2 | SARS-CoV-2, bovine-like CoV |

| Pneumoviridae | Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV A, RSV B, RSV A + B coinfection) | No animal studies or detections reported in Mongolia |

| Adenoviridae | Human adenoviruses (HAdV-B7, B3, D8, C1, C2, C5, C6) | No animal studies or detections reported in Mongolia |

| Paramyxoviridae | Human parainfluenza virus (HPIV-3) | Avian paramyxoviruses (APMV-1, APMV-4, APMV-8), Pesde des petits ruminants virus (PPRV) |

| Human rhinoviruses (HRV-A, HRV-B, HRV-C) | Food-and-mouth disease virus |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Enkhbat, M.; Batzorig, U.; Dashdondog, N.; Trujillo-Vargas, C.M.; Dambadarjaa, D.; Gray, G.C. The Highly Interrelated Morbidity Respiratory Viruses Cause Among Humans and Animals in Mongolia. Viruses 2025, 17, 1557. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121557

Enkhbat M, Batzorig U, Dashdondog N, Trujillo-Vargas CM, Dambadarjaa D, Gray GC. The Highly Interrelated Morbidity Respiratory Viruses Cause Among Humans and Animals in Mongolia. Viruses. 2025; 17(12):1557. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121557

Chicago/Turabian StyleEnkhbat, Maralmaa, Ulziikhutag Batzorig, Nyamaakhuu Dashdondog, Claudia M. Trujillo-Vargas, Davaalkham Dambadarjaa, and Gregory C. Gray. 2025. "The Highly Interrelated Morbidity Respiratory Viruses Cause Among Humans and Animals in Mongolia" Viruses 17, no. 12: 1557. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121557

APA StyleEnkhbat, M., Batzorig, U., Dashdondog, N., Trujillo-Vargas, C. M., Dambadarjaa, D., & Gray, G. C. (2025). The Highly Interrelated Morbidity Respiratory Viruses Cause Among Humans and Animals in Mongolia. Viruses, 17(12), 1557. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121557