Abstract

In the years of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), various treatment options have been utilized. COVID-19 continues to circulate in the global population, and the evolution of the Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus has posed significant challenges to the treatment and prevention of infection. Remdesivir (RDV), an anti-viral agent with in vitro efficacy against coronaviruses, is a potent and safe treatment as suggested by a plethora of in vitro and in vivo studies and clinical trials. Emerging real-world data have confirmed its effectiveness, and there are currently datasets evaluating its efficacy and safety against SARS-CoV-2 infections in various clinical scenarios, including some that are not in the SmPC recommendations according for COVID-19 pharmacotherapy. Remdesivir increases the chance of recovery, reduces progression to severe disease, lowers mortality rates, and exhibits beneficial post-hospitalization outcomes, especially when used early in the course of the disease. Strong evidence suggests the expansion of remdesivir use in special populations (e.g., pregnancy, immunosuppression, renal impairment, transplantation, elderly and co-medicated patients) where the benefits of treatment outweigh the risk of adverse effects. In this article, we attempt to overview the available real-world data of remdesivir pharmacotherapy. With the unpredictable course of COVID-19, we need to utilize all available knowledge to bridge the gap between clinical research and clinical practice and be sufficiently prepared for the future.

1. Introduction

In December 2019 in Wuhan, China, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was first identified, calling the world to face an unprecedented health hazard. Due to its rapid transmission, it quickly spread throughout the world, and on 11 March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) characterized the outbreak as a pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic has put a strain on health systems worldwide, causing severe pneumonia and thus increasing hospitalization, intensive care use (ICU) admissions, and mortality rates, especially in people with comorbidities.

SARS-CoV-2 transmission occurs when respiratory droplets and aerosolized viral particles bind to host surface cellular receptors of the upper respiratory tract, conjunctiva, and gastrointestinal tract. The highest risk of transmission occurs in the early phase of the disease, prior to experiencing symptoms. The incubation period is three to five days, depending on protein S variations and virus mutations, while the viral load peaks within one week after symptom onset. Disease progression follows a biphasic course, initially reflecting active viral replication and toxicity, followed by a hyperinflammatory response [1]. Symptomatic COVID-19 varies from mild disease to severe pneumonia, which may lead to hospitalization, respiratory failure, the need for mechanical ventilation, ICU, and death. Multiple vaccines and treatment options have been used to mitigate the effects of COVID-19 on public health. Early intervention, especially in high-risk populations, is pivotal to ensure the best outcomes for patients.

Remdesivir (RDV), branded under the name Veklury, is an antiviral agent that has previously demonstrated antiviral activity against filoviruses (Ebola viruses, Marburg virus), coronaviruses (SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2), paramyxoviruses (parainfluenza type III virus, Nipah virus, Hendra virus, measles, and mumps virus), and Pnemoviridae (respiratory syncytial virus) [2]. In vitro studies showed that remdesivir exhibited antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2; thus, it was proposed as an investigational drug early during the pandemic [3]. Consequently, based on data from compassionate use program and clinical trials that demonstrated the superior clinical efficacy of remdesivir to placebo, RDV was first approved by the European Medical Agency (EMA) in July 2020, while the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval followed in October 2020. Initial approval was in the form of conditional marketing authorization, which turned into full marketing authorization in 2022 [4,5].

Real-world evidence (RWE) is an important complement to the Randomized Clinical Trials (RCTs) in a fast-changing pandemic landscape. Constant evolution in disease variants, vaccination status, and populations at risk, as well as approved standards of care, mandate the acquisition of RWE to enable decision making across the diverse spectrum of heterogeneous populations. RWE aids in clarifying therapeutic effectiveness by studying outcomes in heterogenous, more representative patient populations; thus, its role in the drug development process is becoming increasingly important. Due to the rapidly changing nature of the COVID-19 pandemic and the rush to make critical health decisions, multiple real-world studies have been conducted, utilizing information from primary and secondary dataset sources. Primary data typically refer to observational data that are collected in a prospective manner, e.g., cohort and case-control studies. Secondary data consist of electronic health records and hospital chargemaster sources [6]. In this study, we aimed to overview the available evidence of the real-world use of RDV with regards to associated outcomes, including safety and effectiveness, and current trends of use.

2. Materials and Methods

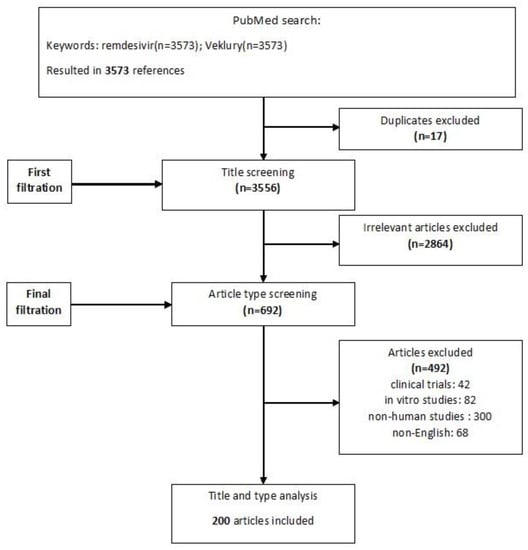

Broad searches of Pubmed and peer-reviewed international conferences were conducted using the keywords “Remdesivir” and/or “Veklury” between 1 February 2020 and 20 April 2023. Relevant publications were identified based on the titles and abstracts, and respective references were hand-searched. Clinical trials or experimental data were excluded. Only English language papers were included in this study. Duplicates and irrelevant articles were removed, and all disagreements were discussed and resolved. The study flowchart is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of included and excluded studies.

3. Remdesivir Outcomes

SARS-CoV-2 is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus. RDV is a phosphoramidite prodrug of a monophosphate nucleoside and acts as a viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) inhibitor, targeting the viral genome replication process [7,8]. Once RDV is metabolized into its pharmacologic active analog adenosine triphosphate (GS-443902), it competes with ATP for integration by the RdRp complex into the nascent RNA strand and, upon subsequent incorporation of a few more nucleotides, results in the termination of RNA synthesis, limiting viral replication. Even higher concentrations of NTP pools can reduce the efficiency of delayed chain termination and result in the formation of full-length RNA products, which retain RDV residues in the primer strand that is later used as a template. Recent data have shown that RDV exhibits inhibitory effects even when present in the template, namely, template-dependent inhibition [9]. RDV’s antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 has been previously well demonstrated in vitro and in clinical trials. Potential benefits expand across a wide spectrum of outcomes in the real-world setting, confirming prior experimental data [4].

3.1. Clinical Improvement and Increased Chance of Recovery

A number of cohort studies have shown favorable results of RDV treatment with regards to clinical improvement and increased chance of recovery [10,11]. When compared with standard of care in patients with severe COVID-19 and the 14-day clinical recovery determined using a 7-point ordinal scale, RDV was associated with significantly greater recovery (aOR: 2.03 [95% CI: 1.34, 3.08], p < 0.001), while mortality was reduced by 62% in patients with severe COVID-19 [11]. Similarly, the WHO 8-point ordinal scale exhibited clinical improvement by day 28 or hospital discharge without worsening of the WHO severity score [12]. In an Italian cohort study, RDV treatment was not associated with a significant reduction of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients, but it was repeatedly associated with a shorter duration of mechanical ventilation (MV) and higher rates of hospital discharge (hazard ratio [HR], 2.25; 95% CI: 1.27–3.97; p = 0.005), independent of other risk factors [13]. In the Greek cohort study of 551 patients, a 5-day course of RDV (200 mg on Day 1, 100 mg on Days 2, 3, 4, and 5) given during the first seven days of symptom onset was associated with significantly shorter hospital stay by 2.6 days, lower rates of intubation (p = 0.019), higher probability of discharge (p = 0.052), and a lower mortality rate (OR 0.38, 95% CI: 0.22–0.67) [14]. These data are in agreement with a retrospective study of five hospitals in the USA comparing the time to clinical improvement versus without RDV. RDV recipients had a shorter time to clinical improvement than controls (median, 5.0 days vs. 7.0 and an adjusted HR of 1.47 [10].

3.2. Reduced Disease Progression

Multiple studies showed RDV’s capacity to mitigate the deleterious effects of COVID-19. In a cohort study from Korea, RDV treatment resulted in significantly reduced progression to MV by day 28 (23% vs. 45%; p = 0.032), as well as a significantly shorter duration of MV versus supportive care (average 1.97 vs. 5.37 d; p = 0.017). Interestingly, rapid viral load reduction was also observed after RDV treatment [15]. When combined with dexamethasone in addition to standard of care, RDV use resulted in a significant reduction in symptom duration, radiographic evidence of pneumonia infiltration, and respiratory failure requiring MV by day 30 (OR 0.36, 95% CI: 0.29–0.46, p < 0.0001) compared to standard of care alone in a recent Danish cohort [16]. This comes to no surprise, as the findings of the Adaptive Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Trial-1 (ACTT-1) suggested that hospitalized COVID-19 patients recovered faster with RDV treatment. A secondary analysis of the data showed higher clinical improvement rates and slower progression to severe disease when treated with RDV. It is indicated that RDV prevents the progression of disease in hospitalized individuals even if they need oxygen supplementation (HR, 0.74; 95% CI: 0.57–0.94) or MV (HR, 0.73; 95% CI: 0.53–1.00) [17].

3.3. Reduced Mortality: Treatment Comparison

There is no doubt that RDV reduced the death rate in COVID-19 hospitalized patients with plentiful real-world studies as evidence. A multicenter US study of 24,856 hospitalized patients treated with RDV showed lower inpatient mortality overall (HR 083; 95% CI: 0.79, 0.87) and increased hospital discharge rate by day 28 (HR 1.19; 95% CI: 1.14, 1.25) compared to matched standard of care-treated individuals [18]. Similarly, in another multicenter study of 28,855 individuals, improved survival rates at 14- and 28-day follow-up were concluded in COVID-19 patients treated with RDV (14-day adjusted HR: 0.76; p < 0.0001; 28-day adjusted HR: 0.88; p = 0.003) [19].

Initially, RDV did not show a mortality benefit in patients without the need of oxygen, contrary to those on low-flow oxygen, where a significant reduction in mortality was achieved (adjusted HR 0.85, 95% CI: 0.77–0.92) [12]. The final results of the Solidarity multinational trial among COVID-19 inpatients confirmed this finding, showing no significant effect of RDV if the patients were already ventilated [20]. However, Mozaffari et al. showed that RDV use was superior even in patients with no need for supplemental oxygen, at 14 and 28 days of follow-up [19]. In agreement with these findings, in non-ventilated hospitalized patients, the likelihood of ventilation and the death rate were reduced [20]. This comes in line with RWE and meta-analysis supporting early administration, as per initial viral replication, and thus the antiviral effect of the regimen [10,21]. Notably, emerging data show that the effect extends across all variant surges [22,23]. The reduction in the mortality rate and hospital admission of outpatient COVID-19-positive individuals has been also compared among nirmatrelvir/ritonavir, molnupiravir, and RDV. Death or hospitalization did not differ among high-risk COVID-19 Italian outpatients treated with currently available antivirals [24].

3.4. Benefits of Early Treatment

Clinical experience indicated that delaying RDV treatment could have unfavorable clinical outcomes in terms of higher rates of progression to severe COVID or death in comparison with earlier treated patients. A large observational cohort of 28,855 individuals in the RDV group associated early initiation of treatment with improved survival among patients with COVID-19 [19]. Pre-admission symptom duration was inversely proportionate to the survival rate when treatment began on admission, but the threshold of clinical benefits remained diverse. A retrospective single-center cohort study showed a significantly lower (p = 0.001) mortality rate when RDV infusion started within 6 days of symptoms, while there was no significant difference when symptom duration exceeded 6 days [25]. Early administration of a 5-day course of remdesivir (within two days of admission) was associated with a significantly shorter time to clinical improvement, lower viral load [26] and positive IgG antibodies, reduced length of hospital stay, and lower risk of in-hospital death [27]. In another retrospective single-center study, the threshold of clinical benefit was set to 9 days from symptom onset for the initiation of RDV when significantly lower all-cause mortality was documented (p = 0.004) [28]. Keeping in mind that testing is delayed for several days following manifestations, other authors showed that if RDV was initiated within three days of a positive test result, the length of stay was shorter (p = 0.03), in addition to the mortality rate and the need for MV [29].

In the course of the pandemic, evidence has also been shown regarding RDV as an early outpatient treatment option for COVID-19. In a recent Greek study, 150 individuals were split into two groups that both received RDV treatment. The control group consisted of hospitalized COVID-19 patients with a median of 8 days from symptom onset who were infused RDV for 5 days, while the study group consisted of non-hospitalized COVID-19 positive individuals who received RDV for 3 days and had a median of 4 days from symptom onset. The early 3-day treatment course of RDV prevented progression to critical disease, significantly decreased hospitalizations (p < 0.001), respiratory failure (p < 0.001), and lowered mortality (p = 0.012) [30]. In another study, where early RDV and sotrovimab were used individually as outpatient treatments, hospitalizations and visits to the emergency department were significantly less likely within 29 days from symptom onset (RDV: 11% versus 23.3%; OR = 0.41; sotrovimab: 8% versus 23.3%; OR = 0.28).There was no significant difference between sotrovimab and RDV [31]. Three independent studies (one prospective and two retrospective) later confirmed the significant reduction in hospitalizations and deaths when RDV was initiated early in the progression of COVID-19 [32,33,34].

3.5. Reduced Post Hospitalization Outcomes

Even following successful treatment, SARS-CoV-2 sequalae may remain present, affecting patients’ health for months. Post-Acute COVID syndrome (PACS) has been identified, even though the underlying pathogenetic mechanisms remain elusive [35]. Patients require a multisystemic approach and commonly need hospital readmission. RWE has shown that previous RDV treatment showed superior results based on the need for readmission during a 30-day follow-up [36], especially among those with milder disease (RR: 0.31; 95% CI: 0.13, 0.75) [37]. In a real-world cohort analysis of individuals hospitalized with COVID-19 who were admitted to the ICU, those treated with RDV had reduced hospital readmission risk at 30, 60, and 90 days, irrespective of the predominant circulating SARS-CoV-2 variant [38]. RDV treatment exhibits a protective effect against the onset of PACS, showing a 35.9% reduction after 6 months of follow-up (p < 0.001) [39]. The results of a long-term follow-up of the randomized SOLIDARITY trial provide no convincing evidence of RDV benefit, but wide confidence intervals included both possible benefit and harm [40]. Further studies are pivotal for safe conclusions to be drawn in this direction.

4. Remdesivir in Combination with Other Agents

Numerous studies have examined the effects of combining RDV with other therapeutic agents, especially immunomodulatory regimes in real-world settings.

The combination of RDV with corticosteroids has been dominating the literature. A Chinese cohort study that included 1544 patients evaluated RDV and dexamethasone coadministration in hospitalized patients with moderate-to-severe COVID-19. Patients in the RDV group had a significantly reduced length of hospital stay by 2.65 days (p = 0.002), lower WHO clinical progression scale scores in the 30-, 60- and 90-day follow-up periods (p < 0.001), and reduced in-hospital mortality (p = 0.042) [41]. A similar study in Italy showed a significantly reduced death rate (p < 0.003) and length of hospital stay (p < 0.0001) in the RDV combined with dexamethasone group compared to dexamethasone alone. Rapid elimination of SARS-CoV-2 was observed (median 6 vs. 16 days; p < 0.001) [41]. Among COVID-19 patients with complicated disease or those admitted to the ICU, those with concurrent use of corticosteroids displayed a reduced in-hospital mortality rate [42,43], in agreement with previous results from the RECOVERY trial [44]. Treatment with dexamethasone, RDV, or both in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 was associated with a lower frequency of neurological complications in an additive manner, such that the greatest benefit was observed in patients who received both drugs together [45].

The combination of RDV with the immunomodulating agents tocilizumab/baricitinib achieved shorter respiratory recovery time (median 11 versus 21 days, p = 0.033) and better respiratory status at the 14- and 28-day follow-up, as shown in a retrospective Japanese study [46]. Experience from Spain came to show that the combination of RDV with dexamethasone and tocilizumab decreased the risk of all-cause 28-day mortality and the need for invasive MV in patients with high viral loads and low-grade systemic inflammation [47].

Current trends examine the combination of RDV with other antivirals or monoclonal agents, especially in the context of immunosuppression and persistent disease, as well as breakthrough or re-infection. With clinical trial data under way, RWE is useful (Table 1) (See next section for details).

Table 1.

Remdesivir experience in special populations.

5. Special Populations

Patients with multiple co-morbidities and special conditions were at particular high risk for adverse outcomes following infection with SARS-CoV-2. Post vaccination statistics showed lower induced immune responses in immunocompromised patients, especially those with hematological malignancies and solid organ transplant recipients [59]. Although patients with common co-morbidities e.g., hypertension, pulmonary disease etc., are included in many clinical trials, special populations, e.g., pregnant women, patients on renal replacement, and hematologic patients, are often underrepresented due to bioethics, legislation or vulnerability. Evidence mostly comes a posteriori following implementation in clinical practice.

RDV has shown nephrotoxicity in non-human studies. Even though the respective toxic doses were 3.5 times higher than those used in treatment, RDV use in individuals with impaired renal function is a safety concern. A high number of studies assessed the efficacy and safety of RDV in patients with chronic kidney disease, patients on dialysis, and kidney transplant recipients [61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70]. RDV was well tolerated in patients with acute kidney injury or chronic kidney disease [63] while reducing the risk of mortality in patients on dialysis [64]. RDV treatment within 48 h shortened the time to recovery and discharge in patients with end-stage renal disease [66]. All real-world studies showed that RDV was relatively safe and well tolerated in patients with severe renal disease [62,63,65,81]. The results of RWE and emerging needs also drove the Phase 3, randomized, REDPINE study, recruiting patients with eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, regardless of the need for dialysis. Even in this population, RDV was safe and well tolerated, while no dose adjustment was required [82].

Pregnant women when compared to similar age non-pregnant individuals are more likely to require hospitalization or even admission to the ICU and need invasive MV [71]. They have been historically excluded from drug development research protocols in fear of adverse pregnancy and maternal health outcomes [83]. RWE from the US showed that RDV was a potent and low-risk treatment option, promoting clinical improvement, lowering ICU and death rates, and resulting in a low incidence of serious adverse effects [71,72,73,74].

The evidence of RDV efficacy and safety among immunocompromised populations has come from cohorts or case series, highlighting the potential of a combination of antiviral therapies or prolonged courses of RDV (Table 1) with variable results [32,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80]. Persistent infection in immunocompromised patients remains a concern, as it seems to drive virus evolution and the selection of new variants [84]; hence, experience of individualized successful treatment is necessary. Nonetheless, recent data have shown that RDV-associated reduction in mortality in hospitalized cancer patients was consistently observed across all variants of concern prior to B4/5 [85], while its use reduced re-admission in immunocompromised patients [86]. The available RWE in special populations is summarized in Table 1, including patients with chronic liver disease [77,87], those prone to liver damage [79], the pediatric population [75,76,88], and very elderly [78].

6. Resistance/Mutations

RDV has been recognized as a broad-spectrum antiviral agent, effectively inhibiting the replication of SARS-CoV-2 by binding to the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) [89]. Its unique capacity as an analog allows it to evade the proofreading activity of the viral exoribonuclease, thereby conferring its efficacy against all known coronaviruses [90]. However, after more than 2 years of widespread RDV use during the COVID-19 pandemic, concerns have arisen regarding the potential development of SARS-CoV-2 resistance mechanisms. Surveillance efforts to identify resistance-associated mutations have been limited, as the specific resistance patterns of SARS-CoV-2 remain largely unknown due to its insidious onset and sudden emergence.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, mutations in the conserved nsp12 protein of RdRp, found across all coronaviruses, had been proposed and confirmed to confer resistance against RDV [90]. Consequently, research efforts have primarily focused on this region of the viral genome [91]. A recent exploratory analysis of SARS-CoV-2 genomes revealed low and stable levels of RDV resistance in a real-world setting, with circulating mutated variants conferring resistance to RDV being associated with poor viral fitness [92]. Until recently, only two amino acid substitutions, D484Y and E802D, had been identified in vivo in immunocompromised COVID-19 patients who received intravenous RDV treatment [93,94]. Commonalities between the two cases include prolonged viral shedding due to the patients’ immunocompromised status and underlying lung involvement, raising questions about compartmentalized resistance given RDV poor lung penetration [95,96].

A study investigating the diversity of SARS-CoV-2 within 14 individual patients over time and the impact of antiviral treatment on the virus found that RDV treatment could rapidly fix newly acquired mutations, adding to the list of concerns [97]. Moreover, a pre-print case series of renal transplant recipients reports the development of a newly discovered V792I mutation in SARS-CoV-2’s RdRp following RDV treatment, further emphasizing the need for careful isolation precautions in immunocompromised hosts to prevent the spread of mutated SARS-CoV-2 isolates [98].

7. Limitations

A number of limitations are identified in this review. Even though a systematic and transparent description of methods is presented in the respective sections and Figure 1, bias in the selection and interpretation of studies is possible, as in every literature review. Moreover, we performed a literature review in a rapidly evolving field that has utterly changed since the beginning of the pandemic. Comparison studies included did not involve regimens that at the moment are no longer recommended, e.g., lopinavir/ritonavir and hydroxychloroquine, as no true power of evidence would be added. In this context, it is possible that by the time this manuscript is published, RDV indications may be outdated or more data will be available. In addition, only English-language papers were reviewed. Experience from RDV recorded in non-English literature contributing significant input may have been missed. Moreover, one cannot overcome potential publication bias that already excludes negative results. Grey or unpublished literature was not assessed in this report.

Last, the authors have to recognize potential random and systematic errors that have to be accounted for in real-world study populations before safe conclusions are drawn. Even though random errors caused by population heterogenicity can be addressed with confidence intervals when the sample size is sufficient, systematic errors (bias) including immortal time bias and cofounders, should be taken into account when RWE is assessed. The implementation of methodological approaches such as propensity score matching, risk set sampling, and multivariate analysis helps balance heterogenic features of populations. It is of great importance to equally understand the methods used to achieve sufficient quality of evidence.

8. Expert Opinion and Future Directions

An evidence gap between clinical practice and clinical research calls for harnessing real-world data [99]. RDV (Veklury®) has been proven safe and effective in the treatment of COVID-19 in hospitalized patients, evident by multiple and variable real-world studies. Experience has come to add up from the beginning of the pandemic and extends across a diverse spectrum of disease (early disease with risk factors not requiring oxygen to severe disease requiring oxygen), populations, and/or co-morbidities. The benefits of timely treatment and studies showing similar clinical outcomes in outpatients underline the need for early COVID-19 diagnosis while expanding access to outpatient antimicrobial treatment facilities. Several studies showed that RDV infusion in the outpatient setting seems to be a safe and efficient alternative to conventional hospitalization for treating non-severe COVID-19 patients [100]. In one of the studies, only 2% reported adverse effects and only 5% required hospitalization [101].

Following extensive vaccination coverage, a shift in the affected population has been observed. At the moment, COVID-19 tends to dominate the elderly and/or severely immunocompromised high-risk populations, commonly already hospitalized for reasons other than COVID-19. In the setting of polypharmacy and a lack of drug–drug interactions, and importantly, the absence of specific or strict eligibility criteria as occurs with other regimens, RDV is an ideal candidate for high-risk individuals, asymptomatic early in the course of disease, with an equally safe profile providing a “low burden” of once-a-day infusion. In this case, compliance is ensured as per RDV’s IV administration that requires the presence of a health care provider.

However, the issue of persistent or breakthrough infections in immunocompromised populations remains of concern. Simultaneous or sequential combination with other antivirals and/or repeated or prolonged courses have been proposed. Different mechanisms of action across various available antivirals can potentiate synergistic effects when co-administered, with possibly faster and more effective viral clearance in this population [54,57,60]. In view of emerging RWE suggesting that when used for extended or repeated treatment courses, RDV leads to improved clinical and laboratory findings and eventually discharge, large clinical trials are now in progress [48,49,53,56,60] (Table 1).

At present, it is not possible to definitively state that repeated administration of RDV will pose significant challenges in clinical settings. The identified mutations associated with resistance have been found to compromise viral fitness, suggesting that the therapeutic value of RDV is still largely intact [91,92]. A recent in vitro study revealed that introducing the V166L mutation—the sole Nsp12 substitution after 17 passages under RDV, located outside the polymerase active site—into a recombinant SARS-CoV-2 virus led to a modest 1.5-fold increase in EC50, indicating a quite high in vitro barrier to RDV resistance [102]. This comes in line with SARS-CoV-2 resistance analyses from the Phase 3 PINETREE trial indicating a high barrier to the development of RDV resistance in COVID-19 patients [103]. Nevertheless, as our understanding of SARS-CoV-2 resistance mechanisms advances, the pursuit of novel antivirals exhibiting greater affinity for the RdRp complex may become increasingly important.

Such compounds would not only enhance the efficacy of current antiviral agents but also help safeguard against potential future resistance developments. Ideally, a promising future oral version of the RDV compound would exhibit enhanced oral bioavailability and plasma half-life, allowing for significantly and quickly reduced viral loads, tissue-specific localization, and decreased lung injury. Adequate safety and resistance profiles would be ideal, so that maximally maintained antiviral activity against different SARS-CoV-2 variants is ensured.

RDV has been the intravenously administered version (version 1.0) of GS-441524. In that sense, oral GS-441524 derivatives (VV116 and ATV006; version 2.0, targeting highly conserved viral RdRp) could be game-changers in treating COVID-19, as oral administration has the potential to maximize clinical benefits, including a decreased duration of COVID-19 and a reduced post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection, as well as limited side effects such as hepatic accumulation [104]. Nonetheless, the gap between bench and bedside is not to be minimized soon if (1) large-scale manufacturing ability for increased accessibility and affordability to outpatients is not ensured and (2) RWE for better understanding of the clinical phenotype diversity and impact of intervention is not efficiently collected.

Author Contributions

K.A., C.S. and C.G. conceived of the idea; K.A., E.A.R., G.S., E.P., G.K. and S.T. performed literature searches; K.A., E.A.R. and G.S. wrote the manuscript; E.A.R. and G.S. drew figures and table; K.A., C.S., A.T., C.G. and G.K. critically corrected the manuscript; K.A. oversaw the study and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

K.A. has received honoraria from Angelini, Viatris, Gilead Sciences, MSD, GSK/ViiV, Pfizer Hellas, 3M; G.K. has received honoraria from AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol, GENESIS Pharma, Glaxo, Demo, Janssen, Innovis, Unipharma, Novartis, Roche, Meditrina, Sanofi, Takeda; A.T. has received grants and honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline, Astra Zeneca, Chiesi, Roche, and Boehringer Ingelheim; C.G. has received honoraria from Astra Zeneca, Bio-merieux, Gilead Sciences, GSK/ViiV, MSD, Pfizer Hellas, 3M; C.S. has received Menarini, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, MSD, BIANEX, Mylan, WinMedica, Bayer, Sanofi, Novo, Bausch Health, ELPEN, Lilly, Nutricia, Lavipharm. All authors received the aforementioned grants/honoraria outside the submitted work.

References

- Cevik, M.; Kuppalli, K.; Kindrachuk, J.; Peiris, M. Virology, transmission, and pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2. BMJ 2020, 371, m3862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, L. Broad-spectrum prodrugs with anti-SARS-CoV-2 activities: Strategies, benefits, and challenges. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 1373–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frediansyah, A.; Nainu, F.; Dhama, K.; Mudatsir, M.; Harapan, H. Remdesivir and its antiviral activity against COVID-19: A systematic review. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2021, 9, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleem, A.; Kothadia, J.P. Remdesivir. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing LLC: Tampa, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Grein, J.; Ohmagari, N.; Shin, D.; Diaz, G.; Asperges, E.; Castagna, A.; Feldt, T.; Green, G.; Green, M.L.; Lescure, F.X.; et al. Compassionate Use of Remdesivir for Patients with Severe Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2327–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.F.; Hu, F.C.; Lee, P.I. The Advantages and Challenges of Using Real-World Data for Patient Care. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2020, 13, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Tian, L.; Liu, Y.; Hui, N.; Qiao, G.; Li, H.; Shi, Z.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Xie, X.; et al. A promising antiviral candidate drug for the COVID-19 pandemic: A mini-review of remdesivir. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 201, 112527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, Z. Natural Products, Alone or in Combination with FDA-Approved Drugs, to Treat COVID-19 and Lung Cancer. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchesnokov, E.P.; Gordon, C.J.; Woolner, E.; Kocinkova, D.; Perry, J.K.; Feng, J.Y.; Porter, D.P.; Gotte, M. Template-dependent inhibition of coronavirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase by remdesivir reveals a second mechanism of action. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 16156–16165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garibaldi, B.T.; Wang, K.; Robinson, M.L.; Zeger, S.L.; Bandeen-Roche, K.; Wang, M.C.; Alexander, G.C.; Gupta, A.; Bollinger, R.; Xu, Y. Comparison of Time to Clinical Improvement With vs. Without Remdesivir Treatment in Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e213071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olender, S.A.; Walunas, T.L.; Martinez, E.; Perez, K.K.; Castagna, A.; Wang, S.; Kurbegov, D.; Goyal, P.; Ripamonti, D.; Balani, B.; et al. Remdesivir Versus Standard-of-Care for Severe Coronavirus Disease 2019 Infection: An Analysis of 28-Day Mortality. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2021, 8, ofab278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garibaldi, B.T.; Wang, K.; Robinson, M.L.; Betz, J.; Caleb Alexander, G.; Andersen, K.M.; Joseph, C.S.; Mehta, H.B.; Korwek, K.; Sands, K.E.; et al. Real-World Effectiveness of Remdesivir in Adults Hospitalized With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Retrospective, Multicenter Comparative Effectiveness Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75, e516–e524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapadula, G.; Bernasconi, D.P.; Bellani, G.; Soria, A.; Rona, R.; Bombino, M.; Avalli, L.; Rondelli, E.; Cortinovis, B.; Colombo, E.; et al. Remdesivir Use in Patients Requiring Mechanical Ventilation due to COVID-19. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2020, 7, ofaa481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrakis, V.; Rapti, V.; Akinosoglou, K.; Bonelis, C.; Athanasiou, K.; Dimakopoulou, V.; Syrigos, N.K.; Spernovasilis, N.; Trypsianis, G.; Marangos, M.; et al. Greek Remdesivir Cohort (GREC) Study: Effectiveness of Antiviral Drug Remdesivir in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19 Pneumonia. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, E.J.; Ko, J.H.; Kim, S.E.; Kang, S.J.; Baek, J.H.; Heo, E.Y.; Shi, H.J.; Eom, J.S.; Choe, P.G.; Bae, S.; et al. Clinical and Virologic Effectiveness of Remdesivir Treatment for Severe Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Korea: A Nationwide Multicenter Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2021, 36, e83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benfield, T.; Bodilsen, J.; Brieghel, C.; Harboe, Z.B.; Helleberg, M.; Holm, C.; Israelsen, S.B.; Jensen, J.; Jensen, T.; Johansen, I.S.; et al. Improved Survival Among Hospitalized Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treated With Remdesivir and Dexamethasone. A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, 2031–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fintzi, J.; Bonnett, T.; Sweeney, D.A.; Huprikar, N.A.; Ganesan, A.; Frank, M.G.; McLellan, S.L.F.; Dodd, L.E.; Tebas, P.; Mehta, A.K. Deconstructing the Treatment Effect of Remdesivir in the Adaptive Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Trial-1: Implications for Critical Care Resource Utilization. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 74, 2209–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chokkalingam, A.P.; Hayden, J.; Goldman, J.D.; Li, H.; Asubonteng, J.; Mozaffari, E.; Bush, C.; Wang, J.R.; Kong, A.; Osinusi, A.O.; et al. Association of Remdesivir Treatment With Mortality Among Hospitalized Adults With COVID-19 in the United States. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2244505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffari, E.; Chandak, A.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, S.; Thrun, M.; Gottlieb, R.L.; Kuritzkes, D.R.; Sax, P.E.; Wohl, D.A.; Casciano, R.; et al. Remdesivir Treatment in Hospitalized Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Comparative Analysis of In-hospital All-cause Mortality in a Large Multicenter Observational Cohort. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75, e450–e458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Solidarity Trial Consortium. Remdesivir and three other drugs for hospitalised patients with COVID-19: Final results of the WHO Solidarity randomised trial and updated meta-analyses. Lancet 2022, 399, 1941–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amstutz, A.; Speich, B.; Mentré, F.; Rueegg, C.S.; Belhadi, D.; Assoumou, L.; Costagliola, D.; Olsen, I.C.; Briel, M. Remdesivir in Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients: Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Seattle, WA, USA, 19–22 February 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mozaffari, E.; Chandak, A.; Kalil, A.C.; Chima-Melton, C.; Chiang, M.; Lee, E.Y.; Gupta, R.; Wang, C.Y.; Gottlieb, R. Immunocompromised patients hospitalized for COVID-19 in the United States: Evolving patient characteristics and clinical outcomes across emerging variants. In Proceedings of the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases (ECCMID), Copenhagen, Denmark, 15–18 April 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mozaffari, E.; Chandak, A.; Gottlieb, R.L.; Chima-Melton, C.; Read, S.; Dau, L.; Thrun, M.; Gupta, R.; Berry, M.; Hollemeersch, S.; et al. Remdesivir is associated with decreased mortality in hospitalised COVID-19 patients requiring high-flow oxygen in the United States. In Proceedings of the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases (ECCMID), Copenhagen, Denmark, 15–18 April 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tiseo, G.; Barbieri, C.; Galfo, V.; Occhineri, S.; Matucci, T.; Almerigogna, F.; Kalo, J.; Sponga, P.; Cesaretti, M.; Marchetti, G.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir, Molnupiravir, and Remdesivir in a Real-World Cohort of Outpatients with COVID-19 at High Risk of Progression: The PISA Outpatient Clinic Experience. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2023, 12, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Vidal, C.; Alonso, R.; Camon, A.M.; Cardozo, C.; Albiach, L.; Agüero, D.; Marcos, M.A.; Ambrosioni, J.; Bodro, M.; Chumbita, M.; et al. Impact of remdesivir according to the pre-admission symptom duration in patients with COVID-19. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 3296–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spagnuolo, V.; Voarino, M.; Tonelli, M.; Galli, L.; Poli, A.; Bruzzesi, E.; Racca, S.; Clementi, N.; Oltolini, C.; Tresoldi, M.; et al. Impact of Remdesivir on SARS-CoV-2 Clearance in a Real-Life Setting: A Matched-Cohort Study. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2022, 16, 3645–3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.K.H.; Lau, K.T.K.; Au, I.C.H.; Xiong, X.; Lau, E.H.Y.; Cowling, B.J. Clinical Improvement, Outcomes, Antiviral Activity, and Costs Associated With Early Treatment With Remdesivir for Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 74, 1450–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aye, T.T.; Myat, K.; Tun, H.P.; Thiha, P.; Han, T.M.; Win, Y.Y.; Han, A.M.M. Early initiation of remdesivir and its effect on oxygen desaturation: A clinical review study among high-risk COVID-19 patients in Myanmar. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2022, 11, 4644–4649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paranjape, N.; Husain, M.; Priestley, J.; Koonjah, Y.; Watts, C.; Havlik, J. Early Use of Remdesivir in Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19 Improves Clinical Outcomes: A Retrospective Observational Study. Infect. Dis. Clin. Pract. 2021, 29, e282–e286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panagopoulos, P.; Petrakis, V.; Trypsianis, G.; Papazoglou, D. Early 3-day course of remdesivir in vaccinated outpatients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. A success story. J. Chemother. 2022, 34, 550–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccicacco, N.; Zeitler, K.; Ing, A.; Montero, J.; Faughn, J.; Silbert, S.; Kim, K. Real-world effectiveness of early remdesivir and sotrovimab in the highest-risk COVID-19 outpatients during the Omicron surge. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2022, 77, 2693–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biscarini, S.; Villa, S.; Genovese, C.; Tomasello, M.; Tonizzo, A.; Fava, M.; Iannotti, N.; Bolis, M.; Mariani, B.; Valzano, A.G.; et al. Safety Profile and Outcomes of Early COVID-19 Treatments in Immunocompromised Patients: A Single-Centre Cohort Study. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meini, S.; Bracalente, I.; Bontempo, G.; Longo, B.; De Martino, M.; Tascini, C. Early 3-day course of remdesivir to prevent progression to severe Covid-19 in high-risk patients with hospital-acquired SARS-CoV-2 infection: Preliminary results from two Italian outbreaks. New Microbiol. 2022, 45, 304–307. [Google Scholar]

- Rajme-Lopez, S.; Martinez-Guerra, B.A.; Zalapa-Soto, J.; Roman-Montes, C.M.; Tamez-Torres, K.M.; Gonzalez-Lara, M.F.; Hernandez-Gilosul, T.; Kershenobich-Stalnikowitz, D.; Sifuentes-Osornio, J.; Ponce-de-Leon, A.; et al. Early Outpatient Treatment With Remdesivir in Patients at High Risk for Severe COVID-19: A Prospective Cohort Study. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2022, 9, ofac502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalbandian, A.; Sehgal, K.; Gupta, A.; Madhavan, M.V.; McGroder, C.; Stevens, J.S.; Cook, J.R.; Nordvig, A.S.; Shalev, D.; Sehrawat, T.S.; et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozaffari, E.; Liang, S.; Stewart, H.M.; Thrun, M.; Hodgkins, P.; Haubrich, R. 459. COVID-19 Hospitalization and 30-Day Readmission: A Cohort Study of U.S. Hospitals. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2021, 8, S332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, A.; Jindal, A.; Andrea, S.B.; Selvaraj, V.; Dapaah-Afriyie, K. Association of Treatment with Remdesivir and 30-day Hospital Readmissions in Patients Hospitalized with COVID-19. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 363, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.S.; Berry, M.; Abdelghany, M.; Chokkalingam, A. Remdesivir Reduced the Hazard of Hospital Readmission in People With COVID-19 Admitted to the ICU While Delta and Omicron Were the Predominant Circulating Variants. In Proceedings of the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases (ECCMID), Copenhagen, Denmark, 15–18 April 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Boglione, L.; Meli, G.; Poletti, F.; Rostagno, R.; Moglia, R.; Cantone, M.; Esposito, M.; Scianguetta, C.; Domenicale, B.; Di Pasquale, F.; et al. Risk factors and incidence of long-COVID syndrome in hospitalized patients: Does remdesivir have a protective effect? QJM 2022, 114, 865–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nevalainen, O.P.O.; Horstia, S.; Laakkonen, S.; Rutanen, J.; Mustonen, J.M.J.; Kalliala, I.E.J.; Ansakorpi, H.; Kreivi, H.R.; Kuutti, P.; Paajanen, J.; et al. Effect of remdesivir post hospitalization for COVID-19 infection from the randomized SOLIDARITY Finland trial. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrone, A.; Nevola, R.; Sellitto, A.; Cozzolino, D.; Romano, C.; Cuomo, G.; Aprea, C.; Schwartzbaum, M.X.P.; Ricozzi, C.; Imbriani, S.; et al. Remdesivir Plus Dexamethasone Versus Dexamethasone Alone for the Treatment of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Patients Requiring Supplemental O2 Therapy: A Prospective Controlled Nonrandomized Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75, e403–e409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanafusa, M.; Nawa, N.; Goto, Y.; Kawahara, T.; Miyamae, S.; Ueki, Y.; Nosaka, N.; Wakabayashi, K.; Tohda, S.; Tateishi, U.; et al. Effectiveness of remdesivir with corticosteroids for COVID-19 patients in intensive care unit: A hospital-based observational study. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e28168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilgram, L.; Appel, K.S.; Ruethrich, M.M.; Koll, C.E.M.; Vehreschild, M.; de Miranda, S.M.N.; Hower, M.; Hellwig, K.; Hanses, F.; Wille, K.; et al. Use and effectiveness of remdesivir for the treatment of patients with covid-19 using data from the Lean European Open Survey on SARS-CoV-2 infected patients (LEOSS): A multicentre cohort study. Infection 2023, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Group, R.C.; Horby, P.; Lim, W.S.; Emberson, J.R.; Mafham, M.; Bell, J.L.; Linsell, L.; Staplin, N.; Brightling, C.; Ustianowski, A.; et al. Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients with Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundmann, A.; Wu, C.H.; Hardwick, M.; Baillie, J.K.; Openshaw, P.J.M.; Semple, M.G.; Böhning, D.; Pett, S.; Michael, B.D.; Thomas, R.H.; et al. Fewer COVID-19 Neurological Complications with Dexamethasone and Remdesivir. Ann. Neurol. 2023, 93, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kojima, Y.; Nakakubo, S.; Kamada, K.; Yamashita, Y.; Takei, N.; Nakamura, J.; Matsumoto, M.; Horii, H.; Sato, K.; Shima, H.; et al. Combination therapy with remdesivir and immunomodulators improves respiratory status in COVID-19: A retrospective study. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 5702–5712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, S.; Polotskaya, K.; Fernández, M.; Gonzalo-Jiménez, N.; de la Rica, A.; García, J.A.; García-Abellán, J.; Mascarell, P.; Gutiérrez, F.; Masiá, M. Survival benefit of remdesivir in hospitalized COVID-19 patients with high SARS-CoV-2 viral loads and low-grade systemic inflammation. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2022, 77, 2257–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, E.S.; Simmons, W.; Karmarkar, E.N.; Yoke, L.H.; Braimah, A.B.; Orozco, J.J.; Ghiuzeli, C.M.; Barnhill, S.; Sack, C.L.; Benditt, J.O.; et al. Successful Treatment of Prolonged, Severe Coronavirus Disease 2019 Lower Respiratory Tract Disease in a B cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Patient With an Extended Course of Remdesivir and Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 76, 926–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dioverti, M.V.; Gaston, D.C.; Morris, C.P.; Huff, C.A.; Jain, T.; Jones, R.; Anders, V.; Lederman, H.; Saunders, J.; Mostafa, H.H.; et al. Combination Therapy With Casirivimab/Imdevimab and Remdesivir for Protracted SARS-CoV-2 Infection in B-cell-Depleted Patients. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2022, 9, ofac064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajakumar, I.; Isaac, D.L.; Fine, N.M.; Clarke, B.; Ward, L.P.; Malott, R.J.; Pabbaraju, K.; Gill, K.; Berenger, B.M.; Lin, Y.-C.; et al. Extensive environmental contamination and prolonged severe acute respiratory coronavirus-2 (SARS CoV-2) viability in immunosuppressed recent heart transplant recipients with clinical and virologic benefit with remdesivir. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2022, 43, 817–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldi, F.; Dentone, C.; Mikulska, M.; Fenoglio, D.; Mirabella, M.; Magne, F.; Portunato, F.; Altosole, T.; Sepulcri, C.; Giacobbe, D.R.; et al. Case report: Sotrovimab, remdesivir and nirmatrelvir/ritonavir combination as salvage treatment option in two immunocompromised patients hospitalized for COVID-19. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 1062450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trottier, C.A.; Wong, B.; Kohli, R.; Boomsma, C.; Magro, F.; Kher, S.; Anderlind, C.; Golan, Y. Dual Antiviral Therapy for Persistent Coronavirus Disease 2019 and Associated Organizing Pneumonia in an Immunocompromised Host. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 76, 923–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckland, M.S.; Galloway, J.B.; Fhogartaigh, C.N.; Meredith, L.; Provine, N.M.; Bloor, S.; Ogbe, A.; Zelek, W.M.; Smielewska, A.; Yakovleva, A.; et al. Treatment of COVID-19 with remdesivir in the absence of humoral immunity: A case report. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helleberg, M.; Niemann, C.U.; Moestrup, K.S.; Kirk, O.; Lebech, A.-M.; Lane, C.; Lundgren, J. Persistent COVID-19 in an Immunocompromised Patient Temporarily Responsive to Two Courses of Remdesivir Therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 222, 1103–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, M.A.; Chen, T.Y.; Choi, H.; Hwang, M.; Navarathna, D.; Hao, L.; Gale, M., Jr.; Camus, G.; Ramirez, H.E.; Jinadatha, C. Extended Remdesivir Infusion for Persistent Coronavirus Disease 2019 Infection. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2022, 9, ofac382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camprubí, D.; Gaya, A.; Marcos, M.A.; Martí-Soler, H.; Soriano, A.; Mosquera, M.D.M.; Oliver, A.; Santos, M.; Muñoz, J.; García-Vidal, C. Persistent replication of SARS-CoV-2 in a severely immunocompromised patient treated with several courses of remdesivir. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 104, 379–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fesu, D.; Bohacs, A.; Hidvegi, E.; Matics, Z.; Polivka, L.; Horvath, P.; Czaller, I.; Sutto, Z.; Eszes, N.; Vincze, K.; et al. Remdesivir in Solid Organ Recipients for COVID-19 Pneumonia. Transplant. Proc. 2022, 54, 2567–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colaneri, M.; Amarasinghe, N.; Rezzonico, L.; Pieri, T.C.; Segalini, E.; Sambo, M.; Roda, S.; Meloni, F.; Gregorini, M.; Rampino, T.; et al. Early remdesivir to prevent severe COVID-19 in recipients of solid organ transplant: A real-life study from Northern Italy. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 121, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafont, E.; Pere, H.; Lebeaux, D.; Cheminet, G.; Thervet, E.; Guillemain, R.; Flahault, A. Targeted SARS-CoV-2 treatment is associated with decreased mortality in immunocompromised patients with COVID-19. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2022, 77, 2688–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shields, A.M.; Anantharachagan, A.; Arumugakani, G.; Baker, K.; Bahal, S.; Baxendale, H.; Bermingham, W.; Bhole, M.; Boules, E.; Bright, P.; et al. Outcomes following SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with primary and secondary immunodeficiency in the UK. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2022, 209, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.H.; Park, S.D.; Jeon, Y.; Chung, Y.K.; Kwon, J.W.; Jeon, Y.H.; Jung, H.Y.; Park, S.H.; Kim, C.D.; Kim, Y.L.; et al. Clinical Effectiveness and Safety of Remdesivir in Hemodialysis Patients with COVID-19. Kidney Int. Rep. 2022, 7, 2522–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackley, T.W.; McManus, D.; Topal, J.E.; Cicali, B.; Shah, S. A Valid Warning or Clinical Lore: An Evaluation of Safety Outcomes of Remdesivir in Patients with Impaired Renal Function from a Multicenter Matched Cohort. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e02290-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakare, S.; Gandhi, C.; Modi, T.; Bose, S.; Deb, S.; Saxena, N.; Katyal, A.; Patil, A.; Patil, S.; Pajai, A.; et al. Safety of Remdesivir in Patients With Acute Kidney Injury or CKD. Kidney Int. Rep. 2021, 6, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, K.; Nangaku, M.; Ryuzaki, M.; Yamakawa, T.; Yoshihiro, O.; Hanafusa, N.; Sakai, K.; Kanno, Y.; Ando, R.; Shinoda, T.; et al. Survival and predictive factors in dialysis patients with COVID-19 in Japan: A nationwide cohort study. Ren. Replace. Ther. 2021, 7, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, N.N.; Pisano, J.; Nguyen, C.T.; Lew, A.K.; Hazra, A.; Sherer, R.; Mullane, K.M. Remdesivir Use in the Setting of Severe Renal Impairment: A Theoretical Concern or Real Risk? Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e3990–e3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiswarya, D.; Arumugam, V.; Dineshkumar, T.; Gopalakrishnan, N.; Lamech, T.M.; Nithya, G.; Sastry, B.; Vathsalyan, P.; Dhanapriya, J.; Sakthirajan, R. Use of Remdesivir in Patients With COVID-19 on Hemodialysis: A Study of Safety and Tolerance. Kidney Int. Rep. 2021, 6, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elec, F.; Magnusson, J.; Elec, A.; Muntean, A.; Antal, O.; Moisoiu, T.; Cismaru, C.; Lupse, M.; Oltean, M. COVID-19 and kidney transplantation: The impact of remdesivir on renal function and outcome-a retrospective cohort study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 118, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butt, B.; Hussain, T.; Jarrar, M.; Khalid, K.; Albaker, W.; Ambreen, A.; Waheed, Y. Efficacy and Safety of Remdesivir in COVID-19 Positive Dialysis Patients. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estiverne, C.; Strohbehn, I.A.; Mithani, Z.; Hirsch, J.S.; Wanchoo, R.; Goyal, P.G.; Lee Dryden-Peterson, S.; Pearson, J.C.; Kubiak, D.W.; Letourneau, A.R.; et al. Remdesivir in Patients With Estimated GFR <30 ml/min per 1.73 m(2) or on Renal Replacement Therapy. Kidney Int. Rep. 2021, 6, 835–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stancampiano, F.; Jhawar, N.; Alsafi, W.; Valery, J.; Harris, D.M.; Kempaiah, P.; Shah, S.; Heckman, M.G.; Siddiqui, H.; Libertin, C.R. Use of remdesivir for COVID-19 pneumonia in patients with advanced kidney disease: A retrospective multicenter study. Clin. Infect. Pract. 2022, 16, 100207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burwick, R.M.; Yawetz, S.; Stephenson, K.E.; Collier, A.-R.Y.; Sen, P.; Blackburn, B.G.; Kojic, E.M.; Hirshberg, A.; Suarez, J.F.; Sobieszczyk, M.E.; et al. Compassionate Use of Remdesivir in Pregnant Women With Severe Coronavirus Disease 2019. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 73, e3996–e4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, J.; Abdelwahab, M.; Colburn, N.; Day, S.; Cackovic, M.; Rood, K.M.; Costantine, M.M. Early Administration of Remdesivir and Intensive Care Unit Admission in Hospitalized Pregnant Individuals With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Obs. Gynecol. 2022, 139, 619–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrallah, S.; Nguyen, A.Q.; Hitchings, L.; Wang, J.Q.; Hamade, S.; Maxwell, G.L.; Khoury, A.; Gomez, L.M. Pharmacological treatment in pregnant women with moderate symptoms of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022, 35, 5970–5977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, K.M.; Pinilla, M.; Stek, A.M.; Shapiro, D.E.; Barr, E.; Febo, I.L.; Paul, M.E.; Deville, J.G.; George, K.; Knowles, K.; et al. Pharmacokinetics of Tenofovir Alafenamide With Boosted Protease Inhibitors in Pregnant and Postpartum Women Living With HIV: Results From IMPAACT P1026s. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2022, 90, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Rojo, P.; Agwu, A.; Kimberlin, D.; Deville, J.; Mendez-Echevarria, A.; Sue, P.K.; Galli, I.; Humeniuk, R.; Juneja, K.; et al. Remdesivir in the treatment of children 28 days to < 18 years of age hospitalised with COVID-19 in the CARAVAN study. Thorax 2022, 77, A172–A173. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, D.L.; Aldrich, M.L.; Hagmann, S.H.F.; Bamford, A.; Camacho-Gonzalez, A.; Lapadula, G.; Lee, P.; Bonfanti, P.; Carter, C.C.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Compassionate Use of Remdesivir in Children With Severe COVID-19. Pediatrics 2021, 147, e2020047803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umemura, T.; Nishikawa, K.; Mutoh, Y.; Sasano, H.; Kozaki, K.; Yamada, T.; Ichihara, T. Usage experience of remdesivir for SARS-CoV-2 infection in a patient with chronic cirrhosis of Child–Pugh class C. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 1947–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Rincon, J.M.; Lopez-Carmona, M.D.; Cobos-Palacios, L.; Lopez-Sampalo, A.; Rubio-Rivas, M.; Martin-Escalante, M.D.; de-Cossio-Tejido, S.; Taboada-Martinez, M.L.; Muino-Miguez, A.; Areses-Manrique, M.; et al. Remdesivir in Very Old Patients (>/=80 Years) Hospitalized with COVID-19: Real World Data from the SEMI-COVID-19 Registry. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.K.H.; Au, I.C.H.; Cheng, W.Y.; Man, K.K.C.; Lau, K.T.K.; Mak, L.Y.; Lui, S.L.; Chung, M.S.H.; Xiong, X.; Lau, E.H.Y.; et al. Remdesivir use and risks of acute kidney injury and acute liver injury among patients hospitalised with COVID-19: A self-controlled case series study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 56, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldman, J.D.; Lye, D.C.B.; Hui, D.S.C.; Marks, K.; Bruno, R.; Montejano, R.; Spinner, C.; Galli, M.; Ahn, M.Y.; Nahass, R.; et al. Impact of baseline alanine aminotransferase levels on the safety and efficacy of remdesivir in severe COVID-19 patients. Hepatology 2020, 72 (Suppl. 1), 279A. Available online: https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/global-literature-on-novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov/resource/pt/covidwho-986086 (accessed on 29 April 2023).

- Akinosoglou, K.; Schinas, G.; Rigopoulos, E.A.; Polyzou, E.; Tzouvelekis, A.; Adonakis, G.; Gogos, C. COVID-19 Pharmacotherapy in Pregnancy: A Literature Review of Current Therapeutic Choices. Viruses 2023, 15, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, J.R.; Goldman, J.D.; Tuttle, K.R.; Teixeira, J.P.; Koullias, Y.; Llewellyn, J.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, H.; Hyland, R.H.; Osinusi, A.; et al. The REDPINE Study: Efficacy and Safety of Remdesivir in People With Moderately and Severely Reduced Kidney Function Hospitalised for COVID-19 Pneumonia. In Proceedings of the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases (ECCMID), Copenhagen, Denmark, 15–18 April 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.I.; Dallmann, A.; Brooks, K.; Best, B.M.; Clarke, D.F.; Mirochnick, M.; van den Anker, J.N.; Capparelli, E.V.; Momper, J.D. Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic modeling of remdesivir and its metabolites in pregnant women with COVID-19. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharm. 2023, 12, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.; Choudhary, M.C.; Regan, J.; Sparks, J.A.; Padera, R.F.; Qiu, X.; Solomon, I.H.; Kuo, H.H.; Boucau, J.; Bowman, K.; et al. Persistence and Evolution of SARS-CoV-2 in an Immunocompromised Host. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2291–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffari, E.C.A.; Chima-Melton, C.; Kalill, A.; Read, S.; Der-Torossian, C.; Dau, L.; Gupta, R.; Berry, M.; Gottlieb, R.L. Remdesivir is associated with lower mortality in cancer patients hospitalized for COVID-19 across emerging variants. In Proceedings of the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases (ECCMID), Copenhagen, Denmark, 15–18 April 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.Y.; Goldman, J.D.; Berry, M.; Brown, G.; Abdelghany, M.; Chokkalingam, A. Remdesivir Reduces Readmission in Immunocompromised Adult Patients Hospitalised with COVID-19. In Proceedings of the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases (ECCMID), Copenhagen, Denmark, 15–18 April 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, J.D.; Lye, D.C.B.; Hui, D.S.; Marks, K.M.; Bruno, R.; Montejano, R.; Spinner, C.D.; Galli, M.; Ahn, M.Y.; Nahass, R.G.; et al. Remdesivir for 5 or 10 Days in Patients with Severe Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1827–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parcha, V.; Booker, K.S.; Kalra, R.; Kuranz, S.; Berra, L.; Arora, G.; Arora, P. A retrospective cohort study of 12,306 pediatric COVID-19 patients in the United States. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, C.J.; Tchesnokov, E.P.; Woolner, E.; Perry, J.K.; Feng, J.Y.; Porter, D.P.; Götte, M. Remdesivir is a direct-acting antiviral that inhibits RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 with high potency. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 6785–6797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini Maria, L.; Andres Erica, L.; Sims Amy, C.; Graham Rachel, L.; Sheahan Timothy, P.; Lu, X.; Smith Everett, C.; Case James, B.; Feng Joy, Y.; Jordan, R.; et al. Coronavirus Susceptibility to the Antiviral Remdesivir (GS-5734) Is Mediated by the Viral Polymerase and the Proofreading Exoribonuclease. mBio 2018, 9, e00221-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, L.J.; Pruijssers, A.J.; Lee, H.W.; Gordon, C.J.; Tchesnokov, E.P.; Gribble, J.; George, A.S.; Hughes, T.M.; Lu, X.; Li, J.; et al. Mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase confer resistance to remdesivir by distinct mechanisms. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022, 14, eabo0718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Focosi, D.; Maggi, F.; McConnell, S.; Casadevall, A. Very low levels of remdesivir resistance in SARS-COV-2 genomes after 18 months of massive usage during the COVID19 pandemic: A GISAID exploratory analysis. Antivir. Res. 2022, 198, 105247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandhi, S.; Klein, J.; Robertson, A.J.; Peña-Hernández, M.A.; Lin, M.J.; Roychoudhury, P.; Lu, P.; Fournier, J.; Ferguson, D.; Mohamed Bakhash, S.A.K.; et al. De novo emergence of a remdesivir resistance mutation during treatment of persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection in an immunocompromised patient: A case report. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinot, M.; Jary, A.; Fafi-Kremer, S.; Leducq, V.; Delagreverie, H.; Garnier, M.; Pacanowski, J.; Mékinian, A.; Pirenne, F.; Tiberghien, P.; et al. Emerging RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase Mutation in a Remdesivir-Treated B-cell Immunodeficient Patient With Protracted Coronavirus Disease 2019. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e1762–e1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, L. Tissue distributions of antiviral drugs affect their capabilities of reducing viral loads in COVID-19 treatment. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 889, 173634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boshier, F.A.; Pang, J.; Penner, J.; Parker, M.; Alders, N.; Bamford, A.; Grandjean, L.; Grunewald, S.; Hatcher, J.; Best, T. Evolution of viral variants in remdesivir-treated and untreated SARS-CoV-2-infected pediatrics patients. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyer, A.; Günther, T.; Robitaille, A.; Lütgehetmann, M.; Addo, M.M.; Jarczak, D.; Kluge, S.; Aepfelbacher, M.; Schulze zur Wiesch, J.; Fischer, N.; et al. Remdesivir-induced emergence of SARS-CoV2 variants in patients with prolonged infection. Cell Rep. Med. 2022, 3, 100735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, J.I.; Duerr, R.; Dimartino, D.; Marier, C.; Hochman, S.; Mehta, S.; Wang, G.; Heguy, A. Remdesivir resistance in transplant recipients with persistent COVID-19. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 76, 342–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, M.T.; Jimenez-Solem, E.; Ankarfeldt, M.Z.; Nyeland, M.E.; Andreasen, A.H.; Petersen, T.S. The Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial-1 (ACTT-1) in a real-world population: A comparative observational study. Crit. Care 2020, 24, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, S.; Alizadeh, M.; Shahrestanaki, E.; Mohammadpoor Nami, S.; Qorbani, M.; Aalikhani, M.; Hassani Gelsefid, S.; Mohammadian Khonsari, N. Prognostic comparison of COVID-19 outpatients and inpatients treated with Remdesivr: A retrospective cohort study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0277413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereta, I.; Morancho, A.; Lopez, N.; Ibanez, B.; Salas, C.; Moreno, L.; Castells, E.; Barta, A.; Cubedo, M.; Coloma, E.; et al. Hospital at home treatment with remdesivir for patients with COVID-19: Real-life experience. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 127, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Checkmahomed, L.; Carbonneau, J.; Du Pont, V.; Riola, N.C.; Perry, J.K.; Li, J.; Paré, B.; Simpson, S.M.; Smith, M.A.; Porter, D.P.; et al. In Vitro Selection of Remdesivir-Resistant SARS-CoV-2 Demonstrates High Barrier to Resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022, 66, e0019822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, L.L.H.; Li, J.; Martin, R.; Han, D.; Xu, S.; Camus, G.; Perry, J.K.; Hyland, R.; Porter, D.P. Remdesivir Resistance Analyses From The Pinetree Study In Outpatients With COVID-19. In Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Seattle, WA, USA, 19–22 February 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, L.; Song, X.Q. Oral GS-441524 derivatives: Next-generation inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1015355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).