Abstract

Viruses are responsible for the majority of infectious diseases, from the common cold to HIV/AIDS or hemorrhagic fevers, the latter with devastating effects on the human population. Accordingly, the development of efficient antiviral therapies is a major goal and a challenge for the scientific community, as we are still far from understanding the molecular mechanisms that operate after virus infection. Interferon-stimulated gene 15 (ISG15) plays an important antiviral role during viral infection. ISG15 catalyzes a ubiquitin-like post-translational modification termed ISGylation, involving the conjugation of ISG15 molecules to de novo synthesized viral or cellular proteins, which regulates their stability and function. Numerous biomedically relevant viruses are targets of ISG15, as well as proteins involved in antiviral immunity. Beyond their role as cellular powerhouses, mitochondria are multifunctional organelles that act as signaling hubs in antiviral responses. In this review, we give an overview of the biological consequences of ISGylation for virus infection and host defense. We also compare several published proteomic studies to identify and classify potential mitochondrial ISGylation targets. Finally, based on our recent observations, we discuss the essential functions of mitochondria in the antiviral response and examine the role of ISG15 in the regulation of mitochondrial processes, specifically OXPHOS and mitophagy.

1. Introduction

1.1. ISG15 Definition

The innate immune response is the first line of defense against microbial and viral infections. Invading microorganisms produce danger- and pathogen-associated molecular patterns that interact with host pattern-recognition receptors, triggering several intracellular signaling cascades that activate nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB), mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and interferon (IFN) regulatory factors (IRFs), resulting in the expression of a broad array of proteins involved in host defense such as type-I IFNs and proinflammatory cytokines [1,2]. The release of type-I IFNs has both autocrine and paracrine effects via IFNα/β receptors (IFNARs) on the cell surface. Binding to IFNARs leads to the activation of the Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription proteins (JAK-STAT) signaling pathway and the formation of the interferon-stimulated gene factor 3 (ISGF3) complex, with the subsequent expression of IFN-stimulated genes [3] that establish an antiviral state and play important roles in determining the host innate and adaptive immune responses [4].

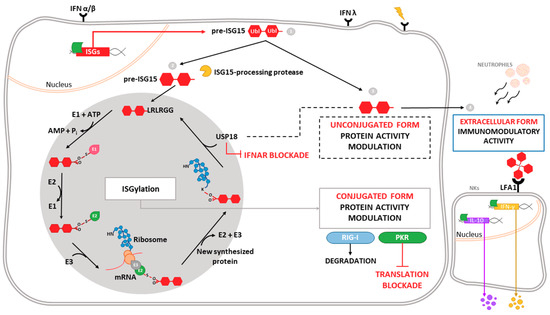

One of the most highly induced genes in the type-I IFN signaling cascade is ISG15 (interferon-stimulated gene 15), which encodes a small ubiquitin-like protein involved in a post-translational modification (PTM) process termed ISGylation. Through this process, ISG15 covalently binds to a wide range of target proteins [5]. ISG15 exists in three different forms: unconjugated within the cell, conjugated to target proteins, and released into the serum (Figure 1). ISG15 is synthesized as a 17-kDa precursor that is proteolytically processed into a mature form of 15 kDa. This processing exposes a carboxy-terminal LRLRGG motif, required for ISGylation [6] (Figure 1). ISGylation is the result of the coordination of three enzymatic activities-activation, conjugation and ligation—performed by ISG15-activating enzymes (E1), ISG15-conjugating enzymes (E2) and ISG15-ligating enzymes (E3), respectively [7] (Figure 1). Considering the broad substrate selectivity described for ISGylation, and the fact that Herc5 (the major ISG15-ligating enzyme) associates with polyribosomes, it has been established that ISGylation targets proteins undergoing active translation [8]. In the context of viral infection, those newly synthesized proteins are largely viral proteins and cellular proteins involved in the innate immune response.

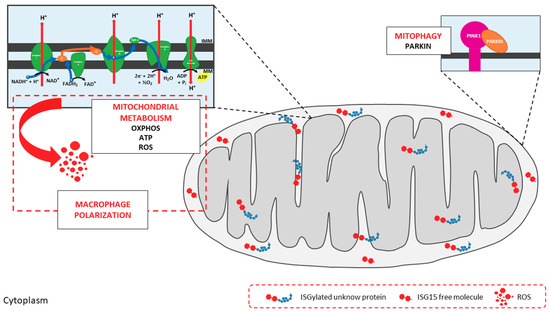

Figure 1.

Intracellular and extracellular activities of ISG15. Different stimuli trigger the expression of ISG15, which is produced as a precursor of 17 kDa with two ubiquitin-like domains linked by a hinge region (1). Intracellular ISG15 can be processed into its mature form and conjugated to de novo synthesized proteins in a process termed ISGylation. ISG15 processing exposes its carboxy-terminal LRLRGG motif, allowing its conjugation to lysine residues in target proteins to modulate their function. In addition, ISGylation is reversible due to the action of the protease USP18, which also regulates IFNAR-mediated signaling (2). ISG15 can remain unconjugated within the cell, regulating protein activity (3), or be secreted as a cytokine, acting as a chemotactic and stimulating factor for immune cells (4). Binding of ISG15 to LFA-1 integrin receptor on the surface of NK cells promotes the activation, production and release of IFN-γ IL-10 after IL-12 priming. Moreover, extracellular ISG15 is able to form dimers/multimers through cysteine residues, to modulate cytokine levels.

ISG15 conjugation to target proteins is a covalent and reversible process through the action of a 43-kDa deISGylase enzyme, ubiquitin-specific protease 18 (USP18) [9,10]. Interestingly, both ISG15 and its conjugating and deconjugating enzymes are upregulated by type-I IFN [9], as well as by other stimuli such as type-II and type-III IFNs [11,12,13], lipopolysaccharide [14], retinoic acid [15], DNA damage or genotoxic reagents [16]. USP18 not only acts as a deconjugating enzyme, but also as a negative regulator of the type-I IFN pathway (Figure 1), with important implications in antiviral and antibacterial responses, immune cell development, autoimmune diseases and cancer [17]. In humans, ISG15 binds to USP18, increasing its stability and leading to a decrease in IFN-α/β signaling. Consequently, ISG15 deficiency results in low USP18 levels, and therefore a sustained elevation in ISG expression. This role for ISG15, which is absent in mice, seems to be predominant in humans, since patients appear not to be more susceptible to viral infections [18,19].

Beyond the above-mentioned forms of ISG15—conjugated to target proteins or unconjugated within the cell—ISG15 is also secreted into the serum, mainly by granulocytes via their secretory pathway [20]. Lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 receptor (LFA1) has recently been identified as the cellular receptor for ISG15 (Figure 1). ISG15 binding to LFA1 triggers the activation of SRC family kinases, promoting IFN-γ and Interleukin-10 (IL-10) secretion in natural killer (NK) cells and, likely, also T-lymphocytes [21]. The role of ISG15 as an inductor of IFN-γ secretion seems to be the basis for the increased susceptibility to mycobacterial diseases in patients lacking a functional form of ISG15 [20]. Secreted ISG15 has also been described to promote NK [22] and dendritic cell [23] maturation, and to act as a chemotactic factor for neutrophils [24]. Along this line, a recent study highlighted the presence of dimeric and multimeric forms of extracellular ISG15 important for its cytokine activity during parasite infection, and speculated on the existence of an unknown ISG15 receptor on dendritic cells that mediates chemotaxis of these cells to the site of infection and IL-1β production [25].

Although there are several features of ISG15 that are shared with ubiquitin, specially its structure, conjugation and deconjugation mechanisms [26], ISGylation has not been shown to stimulate proteasomal degradation of its substrates [10]. Furthermore, some of the ISGylation consequences are exerted by restricting the ubiquitin system, what might be mediated through the conjugation of ISG15 to different E2 and E3 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes [27], or even through the formation of mixed ubiquitin–ISG15 chains [28]. As a result, ISGylation can decrease the polyubiquitylated proteins levels and downregulate protein turnover by the proteasome system [28]. Additionally, unlike ubiquitin, no poly-ISG15 chains or specific ISG15-interacting motifs have been identified yet.

In the following sections, we discuss the antiviral mechanisms mediated by ISGylation of both viral and cellular proteins, with a focus on mitochondrial proteins, as we recently showed that ISG15 modulates essential mitochondrial metabolic processes such as respiration and mitophagy in macrophages, with important implications for innate immune responses [29].

1.2. Antiviral Role of ISG15 and ISGylation

The antiviral activity associated with ISG15 and/or ISGylation has been widely described since the first observation that ISG15-/- mice were more susceptible to viral infections than their wild-type counterparts, albeit the role of ISG15 and ISGylation in viral life cycles is specific to the virus involved [30]. Early studies using ISG15-/- mice demonstrated that ISG15 has a protective effect against lethal infection by Influenza virus, Herpes Simplex virus (HSV-1) and Sindbis virus (SINV) [31]. Similarly, mice deficient in UbE1l—the E1 enzyme of ISG15—were also more susceptible to lethal infection by SINV [32]. Moreover, exogenous expression of wild-type ISG15 by recombinant chimeric SINV protected IFNAR-/- mice against systemic and lethal infections, whereas expression of ISG15 mutants unable to conjugate to proteins did not show this protective effect [33], indicating an intrinsic antiviral role for ISGylation. It should be noted that such an antiviral effect could be due to the conjugation of ISG15 to viral and/or cellular proteins. By contrast, free ISG15, but not ISGylation, has been described to promote antiviral responses against Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) infection [34].

To date, an antiviral effect mediated by ISG15 or ISGylation has been described using in vitro and/or in vivo systems for many other DNA and RNA viruses, including Hepatitis B virus [35], Vesicular stomatitis virus [36,37], Respiratory syncytial virus [38,39], Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) [40], and Ebola virus [27]. The antiviral effect of ISG15 and ISGylation has also been described against viruses of the genera Novirhabdovirus, Birnavirus and Iridovirus in zebrafish, an example of the evolutionary conservation of the antiviral role of ISG15 among vertebrates [41].

Given the importance of the antiviral response governed by ISG15, it is not surprising that viruses have evolved strategies to counteract its antiviral effects. For example, Influenza B virus (IBV) NS1 protein [42], Vaccinia virus E3 protein [43], and Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) IE1 and PUL26 proteins obstruct ISG15 antiviral action by preventing ISGylation [44]. Similar mechanisms are also described for Orthonairovirus and Arterivirus OTU-domain-containing proteases [45] and for Coronavirus papain-like proteases (PLpro), which cleave ISG15 from target proteins. Remarkably, a PLpro inhibitor was shown to protect mice from lethal infection in vivo [46]. Surprisingly, it has been reported that ISGylation is necessary for robust production of Hepatitis C virus (HCV), conferring a novel role for ISG15 as a proviral factor that promotes virus production. Indeed, in human hepatocytes, siRNA silencing of ISG15 was sufficient to both inhibit HCV replication and increase IFN expression [47]. Several reports have now highlighted a role for ISG15 in the monitoring of HCV replication in cell cultures, as well as in the maintenance of HCV in liver, and pinpoint ISG15 as among the predictor genes for non-response to IFN therapy [48].

1.3. ISGylated Viral Proteins

Regarding the direct antiviral effect of ISGylation via conjugation to viral proteins, perhaps the best-known example is the Influenza A virus (IAV) NS1 protein. This non-structural protein is abundantly expressed in infected cells and acts in multiple stages of the viral cycle, with important roles in IFN antagonism including sequestering double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), inhibiting dsRNA-activated protein kinase (PKR) and contributing to the nuclear export of viral mRNAs while blocking the splicing and export of cellular mRNAs [49]. Seven lysine (K) residues in the NS1 protein were identified as potential target sites of ISGylation [50]. Specifically, ISG15 binding to K41, which is part of the NS1 nuclear-localization signal, prevents its interaction with importin-α, inhibiting the translocation of NS1 to the nucleus and therefore repressing IAV replication and viral RNA processing [51]. Moreover, ISGylation of the IAV NS1 protein blocks its ability to counteract the innate immune response, prevents its interaction with PKR and, therefore, restores IFN-induced antiviral activities against IAV [50].

Beyond NS1, Influenza virus nucleoprotein (NP) and matrix protein (M1) have also been reported as targets of ISG15 conjugation. ISGylated NP hinders the oligomerization of the more abundant unconjugated NP, acting as a dominant-negative inhibitor of NP oligomerization, impeding the formation of viral ribonucleoproteins and causing decreased viral protein synthesis and virus replication [52]. Interestingly, this study also identified a new role for Influenza B virus NS1 in the sequestration of ISGylated viral proteins, especially ISGylated NPs, which is perhaps an evolutionary mechanism to block the antiviral effect of ISGylation.

Another example of ISGylation of a viral protein with antiviral effects is the 2A protease (2Apro) of Coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3). ISG15 conjugation to 2Apro inhibits its ability to cleave the eukaryotic initiation factor eIF4G in cardiomyocytes, hindering the translational shutoff induced by CVB3 infection [53]. Consequently, ISG15 conjugation to CVB3 leads to a reduction in virus titers and limits inflammatory cardiomyopathy, heart failure and lethality [53]. Similarly, ISGylation of the HCMV scaffold protein pUL26 interferes with the viral modulation of the innate immune response. Specifically, ISGylation of pUL26 at K136 and K169 inactivates its function in the downregulation of TNFα-mediated NF-κB activation, suppressing HCMV growth [44]. Finally, another example of an ISGylated viral protein is the Human papillomavirus (HPV) L1 capsid protein. ISGylated L1 proteins were shown to be incorporated into HPV pseudoviruses, resulting in a reduced infectivity; the precise mechanism that mediates this inhibitory effect remains elusive [8].

1.4. ISGylated Cellular Proteins

Knowledge about the impact of host protein ISGylation in virus replication and cell homeostasis is still scant. In contrast to ubiquitylation, the molecular effect of ISG15 conjugation on target proteins is not always clear. Protein ISGylation has been reported to increase protein degradation by selective autophagy [54], but there are also many examples where ISGylation inhibits ubiquitylation, frustrating proteasome-mediated degradation of target proteins [55,56,57].

With regard to proteins involved in antiviral response, many effectors of IFN signaling such as PKR [58], retinoic acid-inducible gene-I (RIG-I) [59] and Myxoma resistance protein 1 (MxA) [60] have been reported to be targets of ISGylation. PKR ISGylation at K69 and K159, both located in the dsRNA-binding motif, triggers its activation. This modification occurs in the absence of viral RNA and leads to the phosphorylation of eIF2α, preventing protein translation [58] and suggesting that ISGylation might mediate the activation of PKR in response to stressful stimuli beyond viral infection. Further, ISG15 conjugation to RIG-I decreases RIG-I cellular levels and downregulates RIG-I-mediated signaling. Accordingly, ISGylation of RIG-I represents a negative feedback loop that might control the strength of the antiviral response [59]. Interestingly, free ISG15 also regulates RIG-I levels by promoting the interaction between RIG-I and the autophagic cargo receptor p62, mediating RIG-I degradation via selective autophagy [61]. The interferon-induced MxA protein is also a target of ISGylation, though the effect of this modification is not clear.

Other proteins involved type-I IFN signaling and regulation, such as components of the JAK-STAT pathway or regulators of signal transduction (e.g., JAK1 and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 [ERK1]), are also bound by ISG15, although the functional consequences of ISGylation remain unknown [9,62]. Moreover, interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3), STAT1 and the actin-binding protein Filamin B are also targets for ISG15 conjugation, with implications in the development of the innate immune response. IRF3 is ISGylated at K193, K360 and K366, which attenuates its interaction with the peptidyl-prolyl isomerase PIN1, preventing IRF3 ubiquitylation. Thus, ISGylation of IRF3 sustains its activation and enhances IRF3-mediated antiviral responses by inhibiting its degradation [63]. In a similar manner, ISGylation of phosphorylated STAT1 (pSTAT1) inhibits its polyubiquitylation and further proteasomal degradation, supporting sustained STAT1 activation [57]. ISGylation of Filamin B, which acts as a scaffold of IFN signaling mediators, negatively regulates IFNα-induced c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK) signaling, preventing apoptosis induction [64].

Beyond antiviral response, ISGylation has been described to block the process of virus budding by interfering with the endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT) machinery. For example, ISGylation of CHMP5 triggers its aggregation and the sequestration of the Vps4 cofactor LIP5, impairing the membrane recruitment of Vps4 and its interaction with the Gag budding complex of Avian sarcoma leukosis virus and HIV-1, leading to the inhibition of virus release from the cell [65]. Similarly, ISGylation of tumor susceptibility gene 101 protein (TSG101), another component of the ESCRT sorting complex, inhibits the trafficking of viral hemagglutinin to the cell surface during IAV infection [66], blocking virus release. ISG15 has also been described to inhibit the interaction of HIV-1 Gag protein with TSG101, underscoring a critical role of ISG15 in the IFN-mediated inhibition of HIV-1 budding and release [40]. This sorting mechanism is also used in the generation of exosomes, which are small vesicles secreted to the extracellular environment by most cell types. Interestingly, ISGylation of TSG101 has been recently reported to inhibit exosome secretion [67].

The above examples serve to illustrate the relevance of ISGylation in the induction and regulation of the antiviral response (for a more complete review of ISGylated cellular proteins see Reference [30]), and highlight the complexity of fully understanding the consequences of ISGylation in the regulation of biochemical processes where it is involved. Although the significance of ISGylation of host proteins has been elucidated for only a small set of cellular proteins, ISGylation has a broad target specificity, and there is increasing evidence for its role in regulating many cellular functions. To address this concept, several proteomic studies have been performed to determine ISGylated host proteins. Zhao et al. [60] transfected a tagged ISG15 protein into IFN-stimulated HeLa cells, and used affinity selection to identify 158 ISGylated proteins. In a similar approach, Giannakopoulos et al. [68] used IFN-stimulated USP18-/- mouse embryonic fibroblasts and human U937 cells to detect up to 76 proteins conjugated to endogenously-expressed ISG15. A third proteomic study [69] identified 174 ISGylated cellular proteins in IFN-stimulated A549 human lung adenocarcinoma cells stably expressing FLAG-ISG15. More recently, Peng et al. [70] examined ISGylated proteins in Influenza virus-infected A549 cells, identifying a total of 22 cellular proteins in addition to viral NS1 protein. We have surveyed the proteins identified by these four studies, which rendered up to 330 cellular proteins. Identified proteins include, as previously outlined [8], abundant constitutively expressed proteins as well as diverse interferon-induced proteins. Interestingly, there is only a low degree of overlap between the studies, and only four proteins are common to all four analyses (the glycolytic enzymes ALDO1 and ENO1, the peroxiredoxin PRDX1, and STAT1). These discrepancies may reflect the different transcriptional/translational patterns of the different cell lines included in each study, as it is believed that the biological effects of ISGylation are dynamic and cell type/tissue-specific [5].

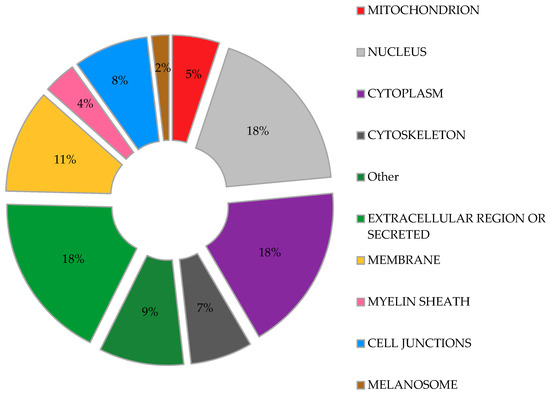

We used DAVID bioinformatics resources [71,72] to determine the subcellular localization of the proteins identified as ISGylation targets in the aforementioned studies, with the aim to obtain a comprehensive picture of the broad range of actions of ISG15. In agreement with a previous report [73], our analysis (Figure 2) shows that ISG15-targeted proteins are found almost throughout the cell, including nucleus, perinuclear space, cytosol, mitochondria, rough endoplasmic reticulum and cell membranes [73]. Moreover, a similar percentage of ISGylation targets were predicted to be located in the nucleus, cytoplasm, extracellular space or as secreted proteins (Figure 2). Interestingly, proteins associated with cytoskeleton and cell junctions represent a significant percentage of the ISG15 target proteins. Other cell structures such as the melanosome or myelin sheath were also represented in the study, perhaps accounting for a specific role of ISGylation in these organelles.

Figure 2.

Predicted subcellular distribution of ISGylated proteins. Proteins identified as ISGylation targets in different proteomic studies were evaluated for their subcellular location. Percentage of the total ISGylated proteins located in each cellular organelle is shown.

The potential role of ISG15 in mitochondria seems to be relevant, as a recent study predicted that 17% of free ISG15 was localized to mitochondria [13]. In our own analysis of the above proteomic studies, fifty-two ISGylated proteins were predicted to localize to mitochondria, representing about 5% of the total ISG15 target proteins (Figure 2). Further examination of these potentially ISGylated proteins indicate that different mitochondrial processes could be affected by ISG15 conjugation (Table 1). Remarkably, several subunits of the ATP synthase (complex V of the respiratory chain) appear to be ISG15 targets, which may be of relevance as mitochondrial ATP production is the main source of energy for the cell. In line with these observations, our recent work linked ISG15 to the control of the mitochondrial oxidative metabolism in macrophages in the context of viral infection [29]. Based on the evident association between ISG15 and mitochondria, we will briefly review the role of mitochondria as antiviral mediators and targets of ubiquitin-like modifiers, focusing on the current knowledge about ISG15- and ISGylation-mediated regulation of these multifunctional organelles.

Table 1.

ISGylated proteins predicted to locate to mitochondria. Proteins identified as ISGylation targets in different proteomic studies [60,68,69,70] predicted to locate to mitochondria. Proteins are grouped according to biological functions.

3. Future Perspectives

The functional significance of PTMs in disease etiology, and the pathologic response to their disruption, is the subject of intense investigation. Many of these reversible modifications act as regulatory mechanisms in mitochondria and show promise for mitochondria-targeted therapeutic strategies. With the advent of mass spectrometry-based screening techniques, there has been a vast increase in our current state of knowledge on mitochondrial PTMs and their protein targets. Detecting ISGylated proteins in different organelles remains challenging, as it typically occurs in only a small portion of the total protein pool of the cell, albeit with essential roles in regulating protein fate and function. Understanding the consequences of ISGylation of mitochondrial proteins will require much work, but should be rewarding not only for developing new strategies to combat viral infections, but also for future applications in other biomedically relevant processes/diseases, for example inflammation, cancer and neurodegeneration.

Funding

This work was supported by grant SAF2014-54623-R and SAF2017-88089-R (funded both by MINISTERIO DE ECONOMÍA, INDUSTRIA Y COMPETIVIDAD, and FEDER/FSE).

Acknowledgments

We thank Diego Sanz for his technical assistance and Kenneth McCreath for reviewing and correcting the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Iwasaki, A. A virological view of innate immune recognition. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 66, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brubaker, S.W.; Bonham, K.S.; Zanoni, I.; Kagan, J.C. Innate immune pattern recognition: A cell biological perspective. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 33, 257–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivashkiv, L.B.; Donlin, L.T. Regulation of type I interferon responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raftery, N.; Stevenson, N.J. Advances in anti-viral immune defence: Revealing the importance of the IFN JAK/STAT pathway. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2017, 74, 2525–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, D.E. Interferon-stimulated gene 15 and the protein ISGylation system. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2011, 31, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potter, J.L.; Narasimhan, J.; Mende-Mueller, L.; Haas, A.L. Precursor processing of pro-ISG15/UCRP, an interferon-beta-induced ubiquitin-like protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 25061–25068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durfee, L.A.; Huibregtse, J.M. The ISG15 conjugation system. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012, 832, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Durfee, L.A.; Lyon, N.; Seo, K.; Huibregtse, J.M. The ISG15 conjugation system broadly targets newly synthesized proteins: Implications for the antiviral function of ISG15. Mol. Cell 2010, 38, 722–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malakhov, M.P.; Kim, K.I.; Malakhova, O.A.; Jacobs, B.S.; Borden, E.C.; Zhang, D.E. High-throughput immunoblotting. Ubiquitiin-like protein ISG15 modifies key regulators of signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 16608–16613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villarroya-Beltri, C.; Guerra, S.; Sanchez-Madrid, F. ISGylation—A key to lock the cell gates for preventing the spread of threats. J. Cell Sci. 2017, 130, 2961–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, J.L.; D’Cunha, J.; Tom, P.; O’Brien, W.J.; Borden, E.C. Production of ISG-15, an interferon-inducible protein, in human corneal cells. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 1996, 16, 937–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, B.; Bai, Q.; Chi, X.; Goraya, M.U.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Chen, B.; Chen, J.L. Infection with Classical Swine Fever Virus Induces Expression of Type III Interferons and Activates Innate Immune Signaling. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tecalco Cruz, A.C.; Mejia-Barreto, K. Cell type-dependent regulation of free ISG15 levels and ISGylation. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2017, 11, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malakhova, O.; Malakhov, M.; Hetherington, C.; Zhang, D.E. Lipopolysaccharide activates the expression of ISG15-specific protease UBP43 via interferon regulatory factor 3. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 14703–14711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitha-Rowe, I.; Hassel, B.A.; Dmitrovsky, E. Involvement of UBE1L in ISG15 conjugation during retinoid-induced differentiation of acute promyelocytic leukemia. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 18178–18187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, Y.J.; Park, J.H.; Chung, C.H. Interferon-Stimulated Gene 15 in the Control of Cellular Responses to Genotoxic Stress. Mol. Cells 2017, 40, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honke, N.; Shaabani, N.; Zhang, D.E.; Hardt, C.; Lang, K.S. Multiple functions of USP18. Cell Death Dis. 2016, 7, e2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Bogunovic, D.; Payelle-Brogard, B.; Francois-Newton, V.; Speer, S.D.; Yuan, C.; Volpi, S.; Li, Z.; Sanal, O.; Mansouri, D.; et al. Human intracellular ISG15 prevents interferon-alpha/beta over-amplification and auto-inflammation. Nature 2015, 517, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speer, S.D.; Li, Z.; Buta, S.; Payelle-Brogard, B.; Qian, L.; Vigant, F.; Rubino, E.; Gardner, T.J.; Wedeking, T.; Hermann, M.; et al. ISG15 deficiency and increased viral resistance in humans but not mice. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogunovic, D.; Byun, M.; Durfee, L.A.; Abhyankar, A.; Sanal, O.; Mansouri, D.; Salem, S.; Radovanovic, I.; Grant, A.V.; Adimi, P.; et al. Mycobacterial disease and impaired IFN-gamma immunity in humans with inherited ISG15 deficiency. Science 2012, 337, 1684–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swaim, C.D.; Scott, A.F.; Canadeo, L.A.; Huibregtse, J.M. Extracellular ISG15 Signals Cytokine Secretion through the LFA-1 Integrin Receptor. Mol. Cell 2017, 68, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Cunha, J.; Knight, E., Jr.; Haas, A.L.; Truitt, R.L.; Borden, E.C. Immunoregulatory properties of ISG15, an interferon-induced cytokine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padovan, E.; Terracciano, L.; Certa, U.; Jacobs, B.; Reschner, A.; Bolli, M.; Spagnoli, G.C.; Borden, E.C.; Heberer, M. Interferon stimulated gene 15 constitutively produced by melanoma cells induces e-cadherin expression on human dendritic cells. Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 3453–3458. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Owhashi, M.; Taoka, Y.; Ishii, K.; Nakazawa, S.; Uemura, H.; Kambara, H. Identification of a ubiquitin family protein as a novel neutrophil chemotactic factor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 309, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napolitano, A.; van der Veen, A.G.; Bunyan, M.; Borg, A.; Frith, D.; Howell, S.; Kjaer, S.; Beling, A.; Snijders, A.P.; Knobeloch, K.P.; et al. Cysteine-Reactive Free ISG15 Generates IL-1beta-Producing CD8alpha(+) Dendritic Cells at the Site of Infection. J. Immunol. 2018, 201, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, T.; Iwahara, S.; Saeki, Y.; Sasajima, H.; Yokosawa, H. Link between the ubiquitin conjugation system and the ISG15 conjugation system: ISG15 conjugation to the UbcH6 ubiquitin E2 enzyme. J. Biochem. 2005, 138, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okumura, A.; Pitha, P.M.; Harty, R.N. ISG15 inhibits Ebola VP40 VLP budding in an L-domain-dependent manner by blocking Nedd4 ligase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 3974–3979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, J.B.; Arimoto, K.; Motamedchaboki, K.; Yan, M.; Wolf, D.A.; Zhang, D.E. Identification and characterization of a novel ISG15-ubiquitin mixed chain and its role in regulating protein homeostasis. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldanta, S.; Fernandez-Escobar, M.; Acin-Perez, R.; Albert, M.; Camafeita, E.; Jorge, I.; Vazquez, J.; Enriquez, J.A.; Guerra, S. ISG15 governs mitochondrial function in macrophages following vaccinia virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perng, Y.C.; Lenschow, D.J. ISG15 in antiviral immunity and beyond. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 423–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenschow, D.J.; Lai, C.; Frias-Staheli, N.; Giannakopoulos, N.V.; Lutz, A.; Wolff, T.; Osiak, A.; Levine, B.; Schmidt, R.E.; Garcia-Sastre, A.; et al. IFN-stimulated gene 15 functions as a critical antiviral molecule against influenza, herpes, and Sindbis viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 1371–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannakopoulos, N.V.; Arutyunova, E.; Lai, C.; Lenschow, D.J.; Haas, A.L.; Virgin, H.W. ISG15 Arg151 and the ISG15-conjugating enzyme UbE1L are important for innate immune control of Sindbis virus. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 1602–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenschow, D.J.; Giannakopoulos, N.V.; Gunn, L.J.; Johnston, C.; O’Guin, A.K.; Schmidt, R.E.; Levine, B.; Virgin, H.W.T. Identification of interferon-stimulated gene 15 as an antiviral molecule during Sindbis virus infection in vivo. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 13974–13983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werneke, S.W.; Schilte, C.; Rohatgi, A.; Monte, K.J.; Michault, A.; Arenzana-Seisdedos, F.; Vanlandingham, D.L.; Higgs, S.; Fontanet, A.; Albert, M.L.; et al. ISG15 is critical in the control of Chikungunya virus infection independent of UbE1L mediated conjugation. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Luo, J.K.; Zhang, D.E. The level of hepatitis B virus replication is not affected by protein ISG15 modification but is reduced by inhibition of UBP43 (USP18) expression. J. Immunol. 2008, 181, 6467–6472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchie, K.J.; Hahn, C.S.; Kim, K.I.; Yan, M.; Rosario, D.; Li, L.; de la Torre, J.C.; Zhang, D.E. Role of ISG15 protease UBP43 (USP18) in innate immunity to viral infection. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 1374–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knobeloch, K.P.; Utermohlen, O.; Kisser, A.; Prinz, M.; Horak, I. Reexamination of the role of ubiquitin-like modifier ISG15 in the phenotype of UBP43-deficient mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25, 11030–11034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, E.C.; Barber, J.; Tripp, R.A. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) attachment and nonstructural proteins modify the type I interferon response associated with suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) proteins and IFN-stimulated gene-15 (ISG15). Virol. J. 2008, 5, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Sanz, R.; Mata, M.; Bermejo-Martin, J.; Alvarez, A.; Cortijo, J.; Melero, J.A.; Martinez, I. ISG15 Is Upregulated in Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection and Reduces Virus Growth through Protein ISGylation. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 3428–3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okumura, A.; Lu, G.; Pitha-Rowe, I.; Pitha, P.M. Innate antiviral response targets HIV-1 release by the induction of ubiquitin-like protein ISG15. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 1440–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langevin, C.; van der Aa, L.M.; Houel, A.; Torhy, C.; Briolat, V.; Lunazzi, A.; Harmache, A.; Bremont, M.; Levraud, J.P.; Boudinot, P. Zebrafish ISG15 exerts a strong antiviral activity against RNA and DNA viruses and regulates the interferon response. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 10025–10036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, W.; Krug, R.M. Influenza B virus NS1 protein inhibits conjugation of the interferon (IFN)-induced ubiquitin-like ISG15 protein. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerra, S.; Caceres, A.; Knobeloch, K.P.; Horak, I.; Esteban, M. Vaccinia virus E3 protein prevents the antiviral action of ISG15. PLoS Pathog. 2008, 4, e1000096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.J.; Kim, E.T.; Kim, Y.E.; Lee, M.K.; Kwon, K.M.; Kim, K.I.; Stamminger, T.; Ahn, J.H. Consecutive Inhibition of ISG15 Expression and ISGylation by Cytomegalovirus Regulators. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frias-Staheli, N.; Giannakopoulos, N.V.; Kikkert, M.; Taylor, S.L.; Bridgen, A.; Paragas, J.; Richt, J.A.; Rowland, R.R.; Schmaljohn, C.S.; Lenschow, D.J.; et al. Ovarian tumor domain-containing viral proteases evade ubiquitin- and ISG15-dependent innate immune responses. Cell Host Microbe 2007, 2, 404–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, X.; Agnihothram, S.; Mielech, A.M.; Nichols, D.B.; Wilson, M.W.; StJohn, S.E.; Larsen, S.D.; Mesecar, A.D.; Lenschow, D.J.; Baric, R.S.; et al. A chimeric virus-mouse model system for evaluating the function and inhibition of papain-like proteases of emerging coronaviruses. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 11825–11833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnaud, N.; Dabo, S.; Akazawa, D.; Fukasawa, M.; Shinkai-Ouchi, F.; Hugon, J.; Wakita, T.; Meurs, E.F. Hepatitis C virus reveals a novel early control in acute immune response. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Li, S.; McGilvray, I. The ISG15/USP18 ubiquitin-like pathway (ISGylation system) in hepatitis C virus infection and resistance to interferon therapy. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2011, 43, 1427–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marc, D. Influenza virus non-structural protein NS1: Interferon antagonism and beyond. J. Gen. Virol. 2014, 95, 2594–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Zhong, G.; Zhu, L.; Liu, X.; Shan, Y.; Feng, H.; Bu, Z.; Chen, H.; Wang, C. Herc5 attenuates influenza A virus by catalyzing ISGylation of viral NS1 protein. J. Immunol. 2010, 184, 5777–5790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Hsiang, T.Y.; Kuo, R.L.; Krug, R.M. ISG15 conjugation system targets the viral NS1 protein in influenza A virus-infected cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 2253–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Sridharan, H.; Chen, R.; Baker, D.P.; Wang, S.; Krug, R.M. Influenza B virus non-structural protein 1 counteracts ISG15 antiviral activity by sequestering ISGylated viral proteins. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahnefeld, A.; Klingel, K.; Schuermann, A.; Diny, N.L.; Althof, N.; Lindner, A.; Bleienheuft, P.; Savvatis, K.; Respondek, D.; Opitz, E.; et al. Ubiquitin-like protein ISG15 (interferon-stimulated gene of 15 kDa) in host defense against heart failure in a mouse model of virus-induced cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2014, 130, 1589–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakashima, H.; Nguyen, T.; Goins, W.F.; Chiocca, E.A. Interferon-stimulated gene 15 (ISG15) and ISG15-linked proteins can associate with members of the selective autophagic process, histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) and SQSTM1/p62. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 1485–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, S.D.; Haas, A.L.; Wood, L.M.; Tsai, Y.C.; Pestka, S.; Rubin, E.H.; Saleem, A.; Nur, E.K.A.; Liu, L.F. Elevated expression of ISG15 in tumor cells interferes with the ubiquitin/26S proteasome pathway. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 921–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Li, X.L.; Hassel, B.A. Proteasomes modulate conjugation to the ubiquitin-like protein, ISG15. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 1594–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganesan, M.; Poluektova, L.Y.; Tuma, D.J.; Kharbanda, K.K.; Osna, N.A. Acetaldehyde Disrupts Interferon Alpha Signaling in Hepatitis C Virus-Infected Liver Cells by Up-Regulating USP18. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2016, 40, 2329–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okumura, F.; Okumura, A.J.; Uematsu, K.; Hatakeyama, S.; Zhang, D.E.; Kamura, T. Activation of double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase (PKR) by interferon-stimulated gene 15 (ISG15) modification down-regulates protein translation. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 2839–2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.J.; Hwang, S.Y.; Imaizumi, T.; Yoo, J.Y. Negative feedback regulation of RIG-I-mediated antiviral signaling by interferon-induced ISG15 conjugation. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 1474–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Denison, C.; Huibregtse, J.M.; Gygi, S.; Krug, R.M. Human ISG15 conjugation targets both IFN-induced and constitutively expressed proteins functioning in diverse cellular pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 10200–10205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.; Duan, T.; Feng, Y.; Liu, Q.; Lin, M.; Cui, J.; Wang, R.F. LRRC25 inhibits type I IFN signaling by targeting ISG15-associated RIG-I for autophagic degradation. EMBO J. 2018, 37, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malakhova, O.A.; Yan, M.; Malakhov, M.P.; Yuan, Y.; Ritchie, K.J.; Kim, K.I.; Peterson, L.F.; Shuai, K.; Zhang, D.E. Protein ISGylation modulates the JAK-STAT signaling pathway. Genes Dev. 2003, 17, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.X.; Yang, K.; Liu, X.; Liu, X.Y.; Wei, B.; Shan, Y.F.; Zhu, L.H.; Wang, C. Positive regulation of interferon regulatory factor 3 activation by Herc5 via ISG15 modification. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010, 30, 2424–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, Y.J.; Choi, J.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Yu, K.R.; Kim, S.M.; Ka, S.H.; Oh, K.H.; Kim, K.I.; Zhang, D.E.; Bang, O.S.; et al. ISG15 modification of filamin B negatively regulates the type I interferon-induced JNK signalling pathway. EMBO Rep. 2009, 10, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pincetic, A.; Kuang, Z.; Seo, E.J.; Leis, J. The interferon-induced gene ISG15 blocks retrovirus release from cells late in the budding process. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 4725–4736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanyal, S.; Ashour, J.; Maruyama, T.; Altenburg, A.F.; Cragnolini, J.J.; Bilate, A.; Avalos, A.M.; Kundrat, L.; Garcia-Sastre, A.; Ploegh, H.L. Type I interferon imposes a TSG101/ISG15 checkpoint at the Golgi for glycoprotein trafficking during influenza virus infection. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 14, 510–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villarroya-Beltri, C.; Baixauli, F.; Mittelbrunn, M.; Fernandez-Delgado, I.; Torralba, D.; Moreno-Gonzalo, O.; Baldanta, S.; Enrich, C.; Guerra, S.; Sanchez-Madrid, F. ISGylation controls exosome secretion by promoting lysosomal degradation of MVB proteins. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannakopoulos, N.V.; Luo, J.K.; Papov, V.; Zou, W.; Lenschow, D.J.; Jacobs, B.S.; Borden, E.C.; Li, J.; Virgin, H.W.; Zhang, D.E. Proteomic identification of proteins conjugated to ISG15 in mouse and human cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 336, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, J.J.; Pung, Y.F.; Sze, N.S.; Chin, K.C. HERC5 is an IFN-induced HECT-type E3 protein ligase that mediates type I IFN-induced ISGylation of protein targets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 10735–10740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Q.-S.; Li, G.-P.; Sun, W.-C.; Yang, J.-B.; Quan, G.-H.; Liu, N. Analysis of ISG15-Modified Proteins from A549 Cells in Response to Influenza Virus Infection by Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Chin. J. Anal. Chem. 2016, 44, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.W.; Sherman, B.T.; Lempicki, R.A. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.W.; Sherman, B.T.; Lempicki, R.A. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: Paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, K.J.; Carr, A.L.; Pru, J.K.; Hearne, C.E.; George, E.L.; Belden, E.L.; Hansen, T.R. Localization of ISG15 and conjugated proteins in bovine endometrium using immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy. Endocrinology 2004, 145, 967–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shadel, G.S.; Clayton, D.A. Mitochondrial DNA maintenance in vertebrates. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1997, 66, 409–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neupert, W.; Herrmann, J.M. Translocation of proteins into mitochondria. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2007, 76, 723–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, T.; Wagner, R. Mitochondrial Outer Membrane Channels: Emerging Diversity in Transport Processes. Bioessays 2018, 40, e1800013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papa, S.; Martino, P.L.; Capitanio, G.; Gaballo, A.; De Rasmo, D.; Signorile, A.; Petruzzella, V. The oxidative phosphorylation system in mammalian mitochondria. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2012, 942, 3–37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cannino, G.; Ciscato, F.; Masgras, I.; Sanchez-Martin, C.; Rasola, A. Metabolic Plasticity of Tumor Cell Mitochondria. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, M. The role of mitochondrial dysfunction in sepsis-induced multi-organ failure. Virulence 2014, 5, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinde, A.; Luo, J.; Bharathi, S.S.; Shi, H.; Beck, M.E.; McHugh, K.J.; Alcorn, J.F.; Wang, J.; Goetzman, E.S. Increased mortality from influenza infection in long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase knockout mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 497, 700–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawai, T.; Akira, S. The roles of TLRs, RLRs and NLRs in pathogen recognition. Int. Immunol. 2009, 21, 317–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seth, R.B.; Sun, L.; Ea, C.K.; Chen, Z.J. Identification and characterization of MAVS, a mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein that activates NF-kappaB and IRF 3. Cell 2005, 122, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koshiba, T.; Yasukawa, K.; Yanagi, Y.; Kawabata, S. Mitochondrial membrane potential is required for MAVS-mediated antiviral signaling. Sci. Signal. 2011, 4, ra7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, F.; Sun, L.; Zheng, H.; Skaug, B.; Jiang, Q.X.; Chen, Z.J. MAVS forms functional prion-like aggregates to activate and propagate antiviral innate immune response. Cell 2011, 146, 448–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, H.S.; Suh, H.W.; Kim, S.J.; Jo, E.K. Mitochondrial Control of Innate Immunity and Inflammation. Immune Netw. 2017, 17, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Gao, C. Regulation of MAVS activation through post-translational modifications. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2018, 50, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, J.R.; Nunnari, J. Mitochondrial form and function. Nature 2014, 505, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Yoon, Y. Mitochondrial fission: Regulation and ER connection. Mol. Cells 2014, 37, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilokani, L.; Nagashima, S.; Paupe, V.; Prudent, J. Mitochondrial dynamics: Overview of molecular mechanisms. Essays Biochem. 2018, 62, 341–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castanier, C.; Garcin, D.; Vazquez, A.; Arnoult, D. Mitochondrial dynamics regulate the RIG-I-like receptor antiviral pathway. EMBO Rep. 2010, 11, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onoguchi, K.; Onomoto, K.; Takamatsu, S.; Jogi, M.; Takemura, A.; Morimoto, S.; Julkunen, I.; Namiki, H.; Yoneyama, M.; Fujita, T. Virus-infection or 5’ppp-RNA activates antiviral signal through redistribution of IPS-1 mediated by MFN1. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1001012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnoult, D. Mitochondrial fragmentation in apoptosis. Trends Cell Biol. 2007, 17, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castanier, C.; Arnoult, D. Mitochondrial dynamics during apoptosis. Med. Sci. 2010, 26, 830–835. [Google Scholar]

- Schrepfer, E.; Scorrano, L. Mitofusins, from Mitochondria to Metabolism. Mol. Cell 2016, 61, 683–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickles, S.; Vigie, P.; Youle, R.J. Mitophagy and Quality Control Mechanisms in Mitochondrial Maintenance. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, R170–R185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youle, R.J.; Narendra, D.P. Mechanisms of mitophagy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 12, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkikas, I.; Palikaras, K.; Tavernarakis, N. The Role of Mitophagy in Innate Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, D.C. Mitochondria: Dynamic organelles in disease, aging, and development. Cell 2006, 125, 1241–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twig, G.; Shirihai, O.S. The interplay between mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 14, 1939–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamanaka, R.B.; Chandel, N.S. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species regulate cellular signaling and dictate biological outcomes. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2010, 35, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tal, M.C.; Sasai, M.; Lee, H.K.; Yordy, B.; Shadel, G.S.; Iwasaki, A. Absence of autophagy results in reactive oxygen species-dependent amplification of RLR signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 2770–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmore, S. Apoptosis: A review of programmed cell death. Toxicol. Pathol. 2007, 35, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osellame, L.D.; Blacker, T.S.; Duchen, M.R. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of mitochondrial function. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 26, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinberg, S.E.; Sena, L.A.; Chandel, N.S. Mitochondria in the regulation of innate and adaptive immunity. Immunity 2015, 42, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, E.L.; Kelly, B.; O’Neill, L.A.J. Mitochondria are the powerhouses of immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2017, 18, 488–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandhir, R.; Halder, A.; Sunkaria, A. Mitochondria as a centrally positioned hub in the innate immune response. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2017, 1863, 1090–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angajala, A.; Lim, S.; Phillips, J.B.; Kim, J.H.; Yates, C.; You, Z.; Tan, M. Diverse Roles of Mitochondria in Immune Responses: Novel Insights Into Immuno-Metabolism. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banoth, B.; Cassel, S.L. Mitochondria in innate immune signaling. Transl. Res. 2018, 202, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, S.K.; Tikoo, S.K. Viruses as modulators of mitochondrial functions. Adv. Virol. 2013, 2013, 738794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, L.D.; Gevaert, K.; De Smet, I. Protein Language: Post-Translational Modifications Talking to Each Other. Trends Plant Sci. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marquez, J.; Lee, S.R.; Kim, N.; Han, J. Post-Translational Modifications of Cardiac Mitochondrial Proteins in Cardiovascular Disease: Not Lost in Translation. Korean Circ. J. 2016, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nesci, S.; Trombetti, F.; Ventrella, V.; Pagliarani, A. Post-translational modifications of the mitochondrial F1FO-ATPase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2017, 1861, 2902–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komander, D.; Rape, M. The ubiquitin code. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2012, 81, 203–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, M.; Reichert, A.S. How to get rid of mitochondria: Crosstalk and regulation of multiple mitophagy pathways. Biol. Chem. 2017, 399, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, S.; Juncker, M.; Kim, C. Regulation of mitophagy by the ubiquitin pathway in neurodegenerative diseases. Exp. Biol. Med. 2018, 243, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, J.W.; Ordureau, A.; Heo, J.M. Building and decoding ubiquitin chains for mitophagy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escobar-Henriques, M.; Langer, T. Dynamic survey of mitochondria by ubiquitin. EMBO Rep. 2014, 15, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.; McStay, G.P. Regulation of Mitochondrial Dynamics by Proteolytic Processing and Protein Turnover. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton, S.M.; Borg, N.A.; Dixit, V.M. Ubiquitin in the activation and attenuation of innate antiviral immunity. J. Exp. Med. 2016, 213, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Qian, C.; Cao, X. Post-Translational Modification Control of Innate Immunity. Immunity 2016, 45, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, E.S. Protein modification by SUMO. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2004, 73, 355–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enserink, J.M. Regulation of Cellular Processes by SUMO: Understudied Topics. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 963, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X. SUMO-Mediated Regulation of Nuclear Functions and Signaling Processes. Mol. Cell 2018, 71, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harder, Z.; Zunino, R.; McBride, H. Sumo1 conjugates mitochondrial substrates and participates in mitochondrial fission. Curr. Biol. 2004, 14, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.; Hildick, K.L.; Luo, J.; Dearden, L.; Wilkinson, K.A.; Henley, J.M. SENP3-mediated deSUMOylation of dynamin-related protein 1 promotes cell death following ischaemia. EMBO J. 2013, 32, 1514–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prudent, J.; Zunino, R.; Sugiura, A.; Mattie, S.; Shore, G.C.; McBride, H.M. MAPL SUMOylation of Drp1 Stabilizes an ER/Mitochondrial Platform Required for Cell Death. Mol. Cell 2015, 59, 941–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.G.; Kim, H.; Jeong, E.I.; Lee, H.J.; Park, S.; Lee, S.Y.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, S.W.; Chung, C.H.; Jung, Y.K. SUMO-Modified FADD Recruits Cytosolic Drp1 and Caspase-10 to Mitochondria for Regulated Necrosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2017, 37, e00254-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerra de Souza, A.C.; Prediger, R.D.; Cimarosti, H. SUMO-regulated mitochondrial function in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2016, 137, 673–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Im, E.; Yoo, L.; Hyun, M.; Shin, W.H.; Chung, K.C. Covalent ISG15 conjugation positively regulates the ubiquitin E3 ligase activity of parkin. Open Biol. 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshizumi, T.; Imamura, H.; Taku, T.; Kuroki, T.; Kawaguchi, A.; Ishikawa, K.; Nakada, K.; Koshiba, T. RLR-mediated antiviral innate immunity requires oxidative phosphorylation activity. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, B.J.; Trewin, A.J.; Amitrano, A.M.; Kim, M.; Wojtovich, A.P. Use the Protonmotive Force: Mitochondrial Uncoupling and Reactive Oxygen Species. J. Mol. Biol. 2018, 430, 3873–3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.; Carter, A.B. The Metabolic Prospective and Redox Regulation of Macrophage Polarization. J. Clin. Cell. Immunol. 2015, 6, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).