Abstract

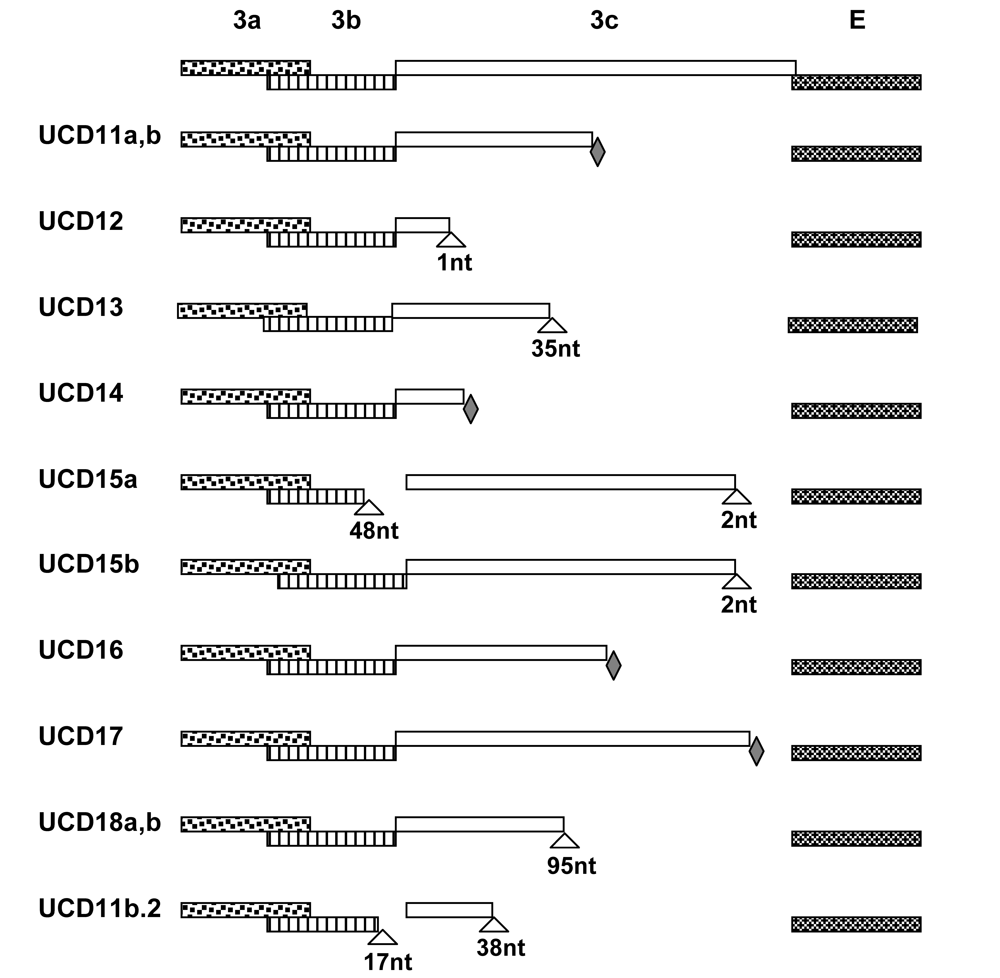

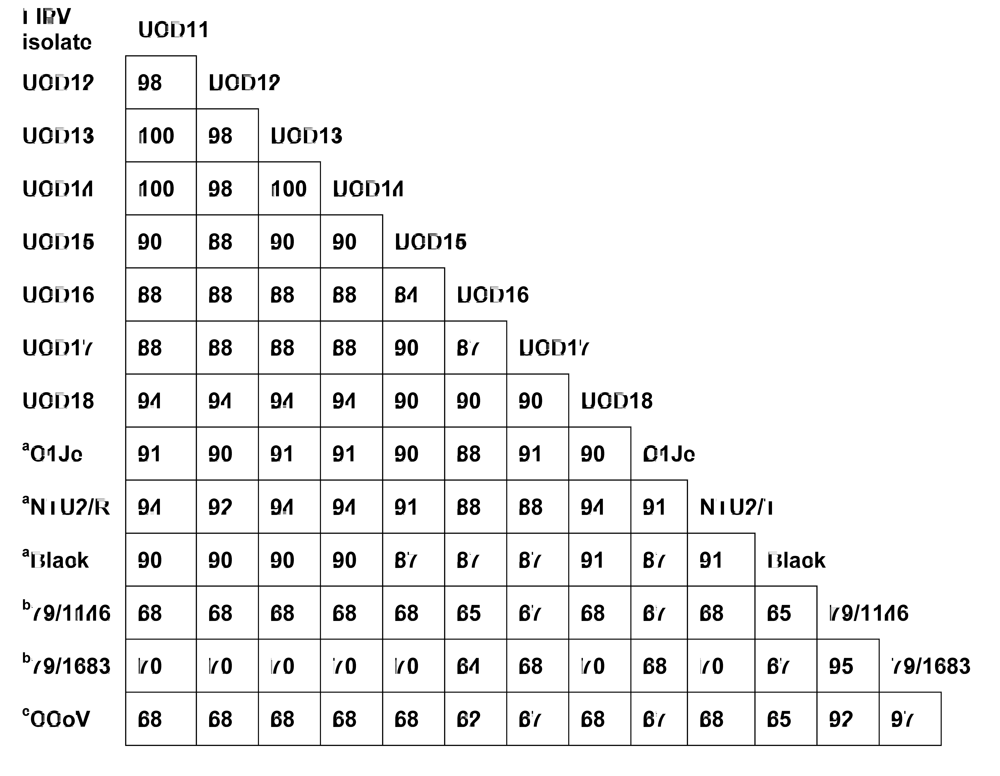

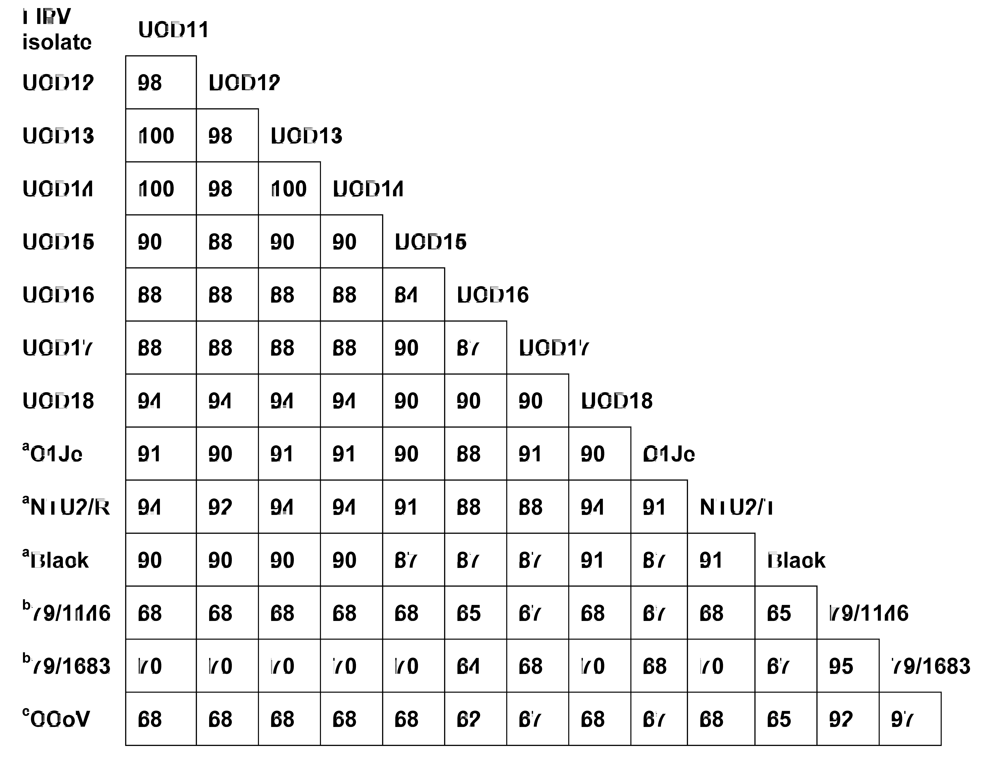

The internal FECV→FIPV mutation theory and three of its correlates were tested in four sibs/half-sib kittens, a healthy contact cat, and in four unrelated cats that died of FIP at geographically disparate regions. Coronavirus from feces and extraintestinal FIP lesions from the same cat were always >99% related in accessory and structural gene sequences. SNPs and deletions causing a truncation of the 3c gene product were found in almost all isolates from the diseased tissues of the eight cats suffering from FIP, whereas most, but not all fecal isolates from these same cats had intact 3c genes. Other accessory and structural genes appeared normal in both fecal and lesional viruses. Deliterious mutations in the 3c gene were unique to each cat, indicating that they did not originate in one cat and were subsequently passed horizontally to the others. Compartmentalization of the parental and mutant forms was not absolute; virus of lesional type was sometimes found in feces of affected cats and virus identical to fecal type was occasionally identified in diseased tissues. Although 3c gene mutants in this study were not horizontally transmitted, the parental fecal virus was readily transmitted by contact from a cat that died of FIP to its housemate. There was a high rate of mutability in all structural and accessory genes both within and between cats, leading to minor genetic variants. More than one variant could be identified in both diseased tissues and feces of the same cat. Laboratory cats inoculated with a mixture of two closely related variants from the same FIP cat developed disease from one or the other variant, but not both. Significant genetic drift existed between isolates from geographically distinct regions of the Western US.

1. Introduction

Feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) was first introduced as an “important disorder of cats” by Holzworth [1] and a clinico-pathologic conference on the disease was published the following year [2]. The incidence of FIP rose progressively over the next two decades. The occurrence of FIP among all cats seen at veterinary medical teaching hospitals in the USA from 1986-1995 was 1:200 among new feline visits, 1:300 among total cat accessions, and 1% of accessions at diagnostic laboratories [3]. The incidence is several times higher among kittens and young cats originating from catteries or shelters. The disease was thought to be viral when first described but no specific etiologic agent was identified at the time [4]. Zook et al. [5] observed virus particles in the tissues of experimentally infected cats, however, the close similarities of FIP virus (FIPV) in tissues to members of the family Coronaviridae was noted by Ward [6]. The ability of FIPV to cause either a non-effusive (dry, parenchymatous) or effusive (wet, non-parenchymatous) form of the disease was first reported by Montali and Strandberg [7]. The close genetic relationship of FIPV to coronaviruses of dogs and swine was first recognized by Pedersen et al. [8]. The existence of two serotypes, feline- or canine-coronavirus like, was described in 1984 [9].

FIP was originally believed to be an uncommon clinical manifestation of a ubiquitous and largely nonpathogenic agent named feline enteric coronavirus (FECV) [10]. Subsequent studies demonstrated that the agent of FIP was distinct from FECV in disease potential but that both viruses co-existed in the same population and were antigenically identical [reviewed in 11, 12]. It was subsequently hypothesized that FIPV might be a simple mutant of FECV [13], and the two viruses were later described as biotypes of each other [14]. Animal studies, with both natural [15] and experimental [16] infection, also suggest that FIPVs arise spontaneously during the course of FECV infection. Vennema et al. [17] demonstrated that all major structural and accessory genes of wild type FECVs were virtually identical to FIPVs from the same or closely related cats. However, 85% of FIPVs studied had deleterious mutations in a small accessory gene called 3c. These mutations, which were either deletions or introduced stop codons, were also found to be unique to each cat.

In spite of indirect and direct supporting evidence for internal FECV→FIPV mutation, the role of FECV mutation in FIP, and especially in the 3c gene, has not been given much attention in the literature of FIP [reviewed 11]. In fact, there is a general feeling that FIPV and FECV are either the same virus, with disease being dependent on the nature of the host’s immune response [reviewed 11], or that the causative mutation is in other genes [18]. Although the precise origin of FIPVs is debated, there appears to be agreement regarding the relative cell tropisms of FECVs and FIPVs. FECVs are thought to have greater tropism for the mature apical intestinal epithelium, while FIPVs are believed to have a greater tropism for macrophages [reviewed 11]. This has led to the a strongly held belief that coronaviruses found in the feces are FECV-like, while viruses found in extra-intestinal (usually lesional) tissues are FIPV-like [19].

The purpose of this study was to repeat the original work of Vennema et al. [17] with a new and geographically diverse group of cats and to test the major tenant of the FECV→FIPV theory and three of its possible correlates. The major tenant of the theory assumes that functional mutations in the 3c gene are somehow related to the FIP biotype. The first correlate of this theory supposes that each FIP cat will have its own unique 3c mutant which is not transmitted cat-to-cat. The second correlate assumes compartmentalization of enteric and FIP biotypes to gut and internal tissues, respectively. The third correlate, if correct, should show FIPVs to be as geographically diverse as the FECVs from which they arise

2. Results and Discussion

2.2. Experimental infection of laboratory cats establishes that FIPV-UCD11a, b possess the FIP biotype and that co-infection with both variants leads to infection with one or the other variant but not both

Twelve laboratory cats were inoculated intraperitoneally with a cell-free inoculum prepared from the diseased omentum of Red, which contained two variant forms of the virus (FIPV-UCD11a and -UCD11b). Three of these cats developed effusive FIP within 2-4 weeks. Viral RNA was isolated from the omentum of each experimentally infected cat at the time of necropsy. The S (one cat) and E, M, N and 3a-c, 7a, b genes (all three cats) were sequenced. One of the cats was found to be infected with FIPV-UCD11a, while two of the cats were each infected with FIPV-UCD11b. Each of these cats had a nearly identical variant of UCD-11a or UCD-11b in its diseased omentum (Table 4). The premature stop codon of parental 3c gene was preserved in FIPV isolates from all three cats. However, FIPV-UCD11b.2 isolated from one of the three cats had acquired two additional large deletions affecting both the 3b and 3c genes that were not in the infecting virus (Table 4 and Figure 2).

Table 4.

Name and biotype designation of coronavirus isolates from three cats dying of experimentally induced FIP. The genes that were sequenced, their mutability, degree of relatedness to the consensus sequence of FIPV-UCD11a, b, and nature of the functional mutation in the 3c gene are given for each cat.

| Cat # | Isolate | Genes sequenced | #SNPs/nts sequenced a | Type of mutation in 3c | GenBank Accession # |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 07-036 | FIPV-UCD11a.1ab | E,M,N,3a-c,7a,b | 5/6711 | Stop codon same as FIPV-UCD11a | FJ917530 |

| FIPV-UCD11a.1bc | 7/6711 | FJ917531 | |||

| 05-243 | FIPV-UCD11b.1ab | E,M,N,3a-c,7a,b | 6/4680 | Stop codon same as FIPV-UCD11b | FJ917532 |

| FIPV-UCD11b.1bc | 7/4680 | FJ917533 | |||

| 98-272 | FIPV-UCD11b.2ab | S,E,M,N,3a-c,7a,b | 5/8943 | Stop codon same as FIPV-UCD11b, plus deletions in 3b,c | FJ917534 |

| FIPV-UCD11b.2bc | 8/8943 | FJ917535 |

a # SNPs detected when compared to their parental FIPV-UCD11a or FIPV-UCD11b viruses.

bVariant strain isolated from experimentally infected cat.

cVariant strain used for SNP comparison.

It is important to determine by animal inoculation studies the true biotype of a feline coronavirus that is being reported, rather than always referring to a generic feline coronavirus [reviewed in 11]. Feline coronaviruses that possess the FIP biotype, such as FIPV-UCD11a,b, will readily induce FIP in from 25-100% of infected individuals, depending on the strain being tested [reviewed in 11]. However, bonifed (cat-to-cat passaged, non-tissue culture adapted) FECV strains will rarely induce FIP in healthy cats [9,12,15,17].

2.5. There was no evidence for cat-to-cat (i.e., horizontal) transmission of 3c gene mutants among cats in the same environment

FIPV is unique from most other viruses, because it is infrequently spread from animal-to-animal in a horizontal manner, yet it is highly infectious when extracts of diseased tissues or fluids are inoculated into naïve cats by a number of routes [reviewed in 11]. The general belief is that enteric biotypes are compartmentalized to the gut, while FIP biotypes are found only within internal organs [19]. However, viruses with 3c mutations identical to FIPVs from lesional tissues were present in the feces of some cats in this study (Table 3), thus making horizontal transmission theoretically possible in certain circumstances. There is also evidence that FIPV may have been shed in urine of FIPV infected cats [35], and that coronavirus may be present in the blood, especially among younger cats [36]. There are also several reports of FIP outbreaks of sufficient magnitude and acuteness to suggest horizontal transmission [reviewed in 11]. While this study did not answer the question as to the relative importance of vertical and horizontal transmission, it indicated the need to carefully study fecal and lesional virus isolates that are involved in explosive, large scale, epizootics of FIP and not just the common enzootic form.

2.6. Precedence and possible role for functional 3c gene mutations

Positive proof that the 3c protein is responsible for the FIP phenotype, in at least a proportion of cats dying of FIP, will require knowledge of its exact function, of which we currently know very little. A GenBlank blast search shows a 30% genetic homology between feline coronavirus 3c and SARS coronavirus 3a (data not shown). Moreover, the 3c protein of feline coronavirus also has an identical hydrophillicity profile to its own M protein and to the M and 3a proteins of SARS coronavirus [37]. These similarities prompted Oostra and colleagues [37] to state – “(…) it appears that all group 1 [corona] viruses expresss group-specific proteins predicted to be triple-spanning membrane proteins. Examples are the feline ORF 3c protein and the HCOV-NL63 ORF 3a protein (…) Despite the small amount of sequence homology among this protein, the similarities in their hydropathy profiles, both to each other and to the corresponding M proteins, as well as to the SARS-CoB 3a protein, are quite remarkable. Nothing is known about these proteins, but it is clear that it will be interesting to learn more about their biological features.” A great deal of research has been reported, and is being conducted, on the SARS coronavirus 3a gene and protein and it is evident that this gene and its product play an important role in viral assembly, spread and pathogenesis, as well as to protective immunity [38-40]. If the 3c protein of feline coronavirus truly has an analogous function to SARS coronavirus 3a protein, SARS coronavirus research might be applicable to feline coronaviruses and how they cause disease.

3. Experimental Section

3.2. Subjects

Four Scottish Fold kittens were born into the same cattery in Sonoma, California; Red, Toby and Lucy were from the same litter of three, while Tux was born a week later in a litter of three to a sister queen and the same tom. Simba, an 11 year-old American curl, was born in an unrelated cattery and resided in another Sonoma household as a pet. Lucy was placed into this household with Simba when she was 17 weeks old, while Red went to live in another home with two other older cats when at 14 weeks of age. Tux and Toby remained in their home cattery with several other cats. Lucy, Tux, Red and Toby first showed signs of indicative FIP at 23, 33, 35 and 40, weeks of age, and were euthanatized with confirmed disease at 27, 37, 39 and 41 weeks of age, respectively. All other contact cats have remained healthy to this time.

Four additional cats were recruited from the western US. Two of them were 26- and 60-month old Burmese (388406 and 392312) from Paradise and Menlo Park, CA, respectively. The third was a 16-month old Birman (388210) from San Jose, CA, and the fourth was a 2-year old Sphinx (Cat-T) from Mountlake Terrace, WA (courtesy Dr. Tracy Tomlinson). Full necropsies on all cats, except Cat-T were performed at the School of Veterinary Medicine Teaching Hospital (VMTH), University of California, Davis, CA. Cat-T was necropsied at a private veterinary diagnostic laboratory (Phoenix Central Laboratory, Everett, WA).

A definitive diagnosis of FIP was confirmed on all eight cats by gross and microscopic examination of tissues and immunohistochemistry. The four related Scottish Folds and Cat-T suffered from the effusive form of FIP, while the two Burmese and one Birman cats suffered from non-effusive FIP. Samples of diseased omentum (effusive FIP) or kidney granulomas (non-effusive FIP), along with feces (or colonic mucus/mucosal scrapings from one cat) were collected at the time of necropsy and stored at -20°C. Feces from the healthy sentinel cat, Simba, were also collected.

3.3. FIPV transmission studies

A cell free inoculum was made from the diseased omentum of Red, one of the four related cats. Omentum was frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground to a powder. The frozen omental powder was reconstituted in 0.25g/ml HBSS (Hanks buffered saline solution) and centrifuged twice at 2,000 x g for 30 minutes. The supernatant was stored at -70°C as viral stock. The viral stock was diluted 1:3 with HBSS when used as inoculum for the FIPV transmission study. Adult specific pathogen free cats were obtained from the breeding colony of the Feline Health and Pet Care Center, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis, CA. A total of twelve cats were inoculated intraperitoneally with 1 ml of cell free viral inoculum. Three cats developed FIP within 2-4 weeks and complete necropsies established that all three cats had effusive FIP. Diseased tissues and feces were collected for isolation of feline coronavirus RNA.

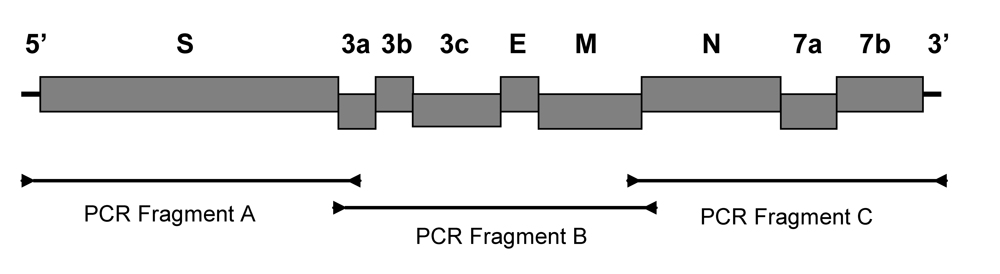

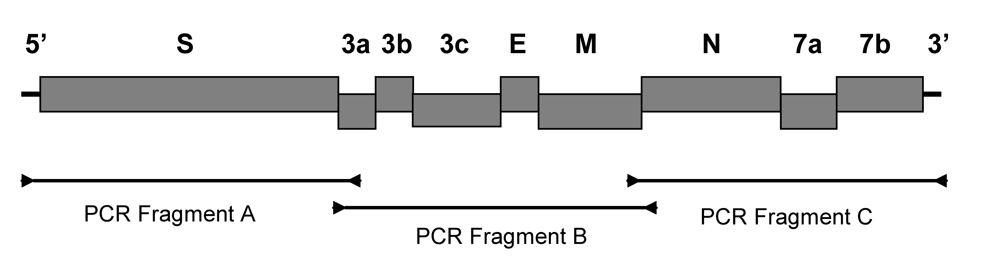

3.6. Cycle sequencing

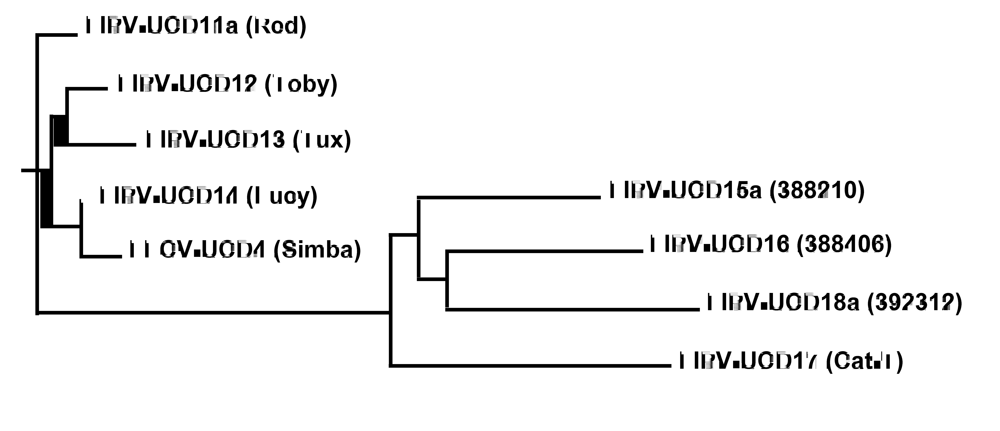

Sixty primers were ultimately used for sequencing, with the S gene requiring the most primer development and modification (primer sequences not shown). Regions containing mixed sequences due to the presence of a minor variant were also resolved with overlapping primers. The purified overlapping PCR products encoding the nine structural and accessory genes were sequenced with a BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, USA) in 15 µl reaction containing 1 µl Big Dye terminator mix, 2 µl reaction buffer (5x), 35 ng sequencing primer, and 3 µl (out of 50 µl) gel purified PCR product. The sequencing reaction was incubated at 93°C for 2 min and then amplified for 40 cycles at 93°C for 20 s, 50°C for 20 s, and 60°C for 4 min. Unincorporated dye terminators and dNTP were removed by gel filtration based Performa DTR Ultra 96-well plate kit (EdgeBio, USA) and the cycle amplified products were analyzed by capillary electrophoresis using an ABI 3730 Genetic Analyser (Applied Biosystems, USA). Vector NTI advance 10 software (Invitrogen, USA) was used for alignment of sequence data. The percent sequence identity for pairwise alignment and the phylogenetic relationship among different FIPV isolates was analyzed using ClustalW2II (www.ebi.ac.uk/tools/clustalw2/).

4. Conclusions

The ubiquitous form of feline coronavirus is readily passed cat-to-cat by the fecal-oral route and is the cause of a mild or unapparent enteritis. Like coronaviruses in general, feline enteric coronavirus (FECV) is undergoing constant mutation within its accessory and structural genes. Feline infectious peritonitis (FIP), which is a highly fatal systemic disease, is a sequel of FECV infection in a small proportion of cats. The virus isolated from the diseased tissues of cats with FIP is highly related to the FECV identified in the feces. Although SNP and deletion mutations were common between isolates from the same cat, only the 3c gene was rendered non functional by such mutations. Deleterious mutations in 3c tend to be found in diseased internal tissues, while viruses with intact 3c are found mainly in the feces. While deleterious mutations of the 3c gene were seen in all 8 FIP cats in this study, and in virtually all previously reported FIPVs, they are by no means a universal finding. However, there is compelling evidence that when they do occur, they are the cause of FIP and not an effect of the disease. Deleterious 3c gene mutants will readily cause FIP when inoculated into laboratory cats, whereas their largely non-pathogenic fecal counterparts with intact 3c genes are readily transmitted from one cat to another. These gene 3c mutants, when they occur, are unique to each cat with FIP, indicating that they arise independently in each host and not by mutation in one cat with subsequent horizontal spread to others. Several minor variants can co-exist in both tissues and feces and when two variants are inoculated together into the same cat, one or the other, but not both, will predominate. The high mutability of feline coronaviruses leads to minor genetic differences between cats in one closely contained geographic area, while significant genetic differences are seen between isolates from geographically disparate regions. More in depth studies on the function of the feline coronavirus 3c gene will be important for determining its precise role in FIP.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Center for Companion Animal Health, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis, CA 95616. We are also grateful for anonymous and named donations from owners of cats dying from FIP. The authors are grateful for the assistance of Sue Weitendorf for allowing access to a critical group of cats used in this study.

References

- Holzworth, J.E. Some important disorders of cats. Cornell Vet. 1963, 53, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Feldman, B.F.; Jortner, B.S. Clinico-pathology conference. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1964, 144, 1409–1411. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rohrbach, B.W.; Legendre, A.M.; Baldwin, C.A.; Lein, D.H.; Reed, W.M.; Wilson R.B. Epidemiology of feline infectious peritonitis among cats examined at veterinary medical teaching hospitals. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2001, 218, 1111–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfe, L.G.; Griesemer, R.A. Feline infectious peritonitis. Pathol. Vet. 1966, 3, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zook, B.C.; King, N.W.; Robinson. R.L.; McCombs H.L. Ultrastructural evidence for the viral etiology of feline infectious peritonitis. Pathol. Vet. 1968, 5, 91–95. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, J. Morphogenesis of a virus in cats with experimental feline infectious peritonitis. Virol. 1970, 41, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montali, R.J.; Strandberg, J.D. Extraperitoneal lesions in feline infectious peritonitis. Vet. Pathol. 1972, 9, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, N.C.; Ward, W. Antigenic relationship of the feline infections peritonitis virus to coronaviruses of other species. Arch. Virol. 1978, 58, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, N. C.; Black, J. W.; Boyle, J. F.; Evermann, J. F.; McKeirnan, A. J.; Ott, R. L. Pathogenic differences between various feline coronavirus isolates. Coronaviruses; molecular biology and pathogenesis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1984, 173, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, N.C.; Boyle, J.F.; Floyd, K.; Fudge, A.; Barker J. An enteric coronavirus infection of cats and its relationship to feline infectious peritonitis. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1981, 42, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, N.C. A review of feline infectious peritonitis virus infection: 1963-2008. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2009, 11, 225–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, N.C.; Allen, C.E.; Lyons L.A. Pathogenesis of feline enteric coronavirus infection. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2008, 10, 529–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, N.C. Virologic and immunologic aspects of feline infectious peritonitis virus infection. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1987, 218, 529–550. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Horzinek, M.C.; Herrewegh, A.; de Groot, R.J. Perspectives on feline coronavirus evolution. Feline Pract. 1995, 23, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hickman, M.A.; Morris, J.G.; Rogers, Q.R.; Pedersen, N.C. Elimination of Feline Coronavirus Infection from a Large Experimental Specific Pathogen-Free Cat Breeding Colony by Serologic Testing and Isolation. Feline Pract. 1995, 23, 96–102. [Google Scholar]

- Poland, A.M.; Vennema, H.; Foley, J.E.; Pedersen, N.C. Two related strains of feline infectious peritonitis virus isolated from immunocompromised cats infected with a feline enteric coronavirus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1996, 34, 3180–3184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vennema, H.; Poland, A.; Foley, J.; Pedersen, N.C. Feline infectious peritonitis viruses arise by mutation from endemic feline enteric coronaviruses. Virol. 1998, 243, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rottier, P. J.; Nakamura, K. Acquisition of macrophage tropism during the pathogenesis of feline infectious peritonitis is determined by mutations in the feline coronavirus spike protein. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 14122–14130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dye, C.; Siddell, S. G. Genomic RNA sequence of feline coronavirus strain FCoV C1Je. J Feline Med. Surg. 2007, 9, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrewegh, A.A.; Mähler , M.; Hedrich, H.J.; Haagmans, B.L.; Egberink, H.F.; Horzinek, M.C.; Rottier, P.J.; de Groot, R.J. Persistence and evolution of feline coronavirus in a closed cat-breeding colony . Virol. 1997, 4 , 349–363. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C-N.; Su, B-L.; Huang, H-P.; Lee, J-J.; Hsieh, M-W.; Chueh, L-L. Field strain feline coronaviruses with small deletions in ORF7b associated with both enteric infection and feline infectious peritonitis. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2009, 11, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, M.; Boedeker, N.; Gibbs, P.; Kania, S. Deletions in the 7a ORF of feline coronavirus associated with an epidemic of feline infectious peritonitis. Vet. Microbiol. 2001, 8, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, I.; Kecskeméti, S.; Tanyi, J.; Klingeborn, B.; Belák S. Preliminary studies on feline coronavirus distribution in naturally and experimentally infected cats. Res. Vet. Sci. 2000, 68, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addie, D. D.; Kennedy, L. J.; Nart, P ; Radford, A. D. Feline leucocyte antigen class II polymorphism and susceptibility to feline infectious peritonitis. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2004, 6, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kipar, A.; Baptiste, K.; Barth, A.; Reinacher, M. Natural FCoV infection: cats with FIP exhibit significantly higher viral loads than healthy infected cats. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2006, 8, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipar , A.; Meli, M. L.; Failing, K.; Euler, T.; Gomes-Keller, M. A.; Schwartz, D.; Lutz, H.; Reinacher, M. Natural feline coronavirus infection: differences in cytokine patterns in association with the outcome of infection. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2006, 112, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meli, M.; Kipar, C.; Müller, A.; Jenal, K.; Gönczi, E.; Borel, N.; Gunn-Moore, D.; Chalmers, S.; Linn, F.; Rinacher, M.; Lutz, H. High viral loads despite absence of clinical and pathological findings in cats experimentally infected with feline coronavirus (FCoV) type I and in naturally FCoV-infected cats. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2004, 6, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paltrinieri, S.; Gelain, M.E.; Ceciliani, F.; Ribera, A.M.; Battilani, M. Association between faecal shedding of feline coronavirus and serum alpha1-acid glycoprotein sialylation. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2008, 10, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foley, J. E.; Pedersen, N. C. Inheritance of susceptibility of feline infectious peritonitis in purebred catteries. Feline Pract. 1996, 24, 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, J. E.; Poland, A.; Carlson, J.; Pedersen, N.C. Risk factors for feline infectious peritonitis among cats in multiple-cat environments with endemic feline enteric coronavirus. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1997, 210, 1313–1318. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Battilani, M.; Coradin, T.; Scagliarini, A.; Ciulli, S.; Ostanello, F.; Prosperi, S.; Morganti, L. Quasispecies composition and pylogenetic analysis of feline coronaviruses (FCoVs) in naturally infected cats. FEMS 32. Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2003, 39, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, M.; Mitsutake, Y.; Miyanohara, Y. Antigenic and plaque variations of serotype II feline infectious peritonitis coronaviruses. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 1997, 59, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addie, D.D.;Schaap; Nicolson, L; Jarrett, O. Persistence and transmission of natural type I feline coronavirus infection. J. Gen. Virol. 2003, 84, 2735–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrewegh, A.A.; Vennema, H.; Horzinek, M.C.; Rottier, P.J.; de Groot, R.J. The molecular genetics of feline coronaviruses: comparative sequence analysis of the ORF7a/7b transcription unit of different biotypes. Virol. 1995, 212, 622–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, Jr., W.D.; Hurvitz, L. Feline infectious peritonitis: Experimental studies. J Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1971, 158, 994–1002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Can-Sahna, K.; Soydal Ataseven, V.; Pinar, D.; Oğuzoğlu, T. C. The detection of feline coronaviruses in blood samples from cats by mRNA RT-PCR. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2004, 9, 369–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oostra, M.; de Haan, C.A.M.; de Groot, R.J.; Rottier P.J.M. Glycosylation of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus triple-spanning membrane proteins 3a and M. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 2326–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, N.; Mossel, E. C.; Narayanan, K.; Popov, V. L.; Huang, C.; Inoue, T.; Peters, C. J.; Makino, S. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coroanvirus 3a protein is a viral structural protein. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 3182–3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, X.; Guo, Z.; Yang, H.; Peng, L.; Xie, Y.; Wong, T. Y.; Lai, S. T.; Guo, Z. Amino terminus of the SARS coronavirus protein 3a elicits strong, potentially protective humoral responses in infected patients. J. Gen. Virol. 2006, 87, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y. J. The Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)-coronavirus 3a protein may function as a modulator of the trafficking properties of the spike protein. Virol. J. 2005, 10, 2–5. [Google Scholar]

© 2009 by the authors; licensee Molecular Diversity Preservation International, Basel, Switzerland. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.