Abstract

As a critical institutional arrangement for regulating the distribution of ecosystem service benefits, the scientific setting of ecological compensation standards is particularly vital in cross-regional watershed governance. However, there is currently a lack of methods grounded in the multifunctionality of forests and residents’ preferences for determining compensation. Taking the Jinghe watershed as a case study, this research employed a contingent valuation questionnaire survey (n = 747 valid responses) to analyze residents’ perceptions and willingness for forest ecological compensation. The results show that (1) watershed residents generally understand the multifunctional services of forests (cognitive rate: 71.6%–96.4%), and most agree that upstream forest construction benefits downstream ecology, but 30%–40% remain unclear about specific compensation policies. (2) The average willingness to accept (WTA) compensation for upstream residents is 314.10 CNY/mu/year, while the average willingness to pay (WTP) for downstream residents is 289.59 CNY/mu/year. This translates to a compensation standard range of 4343.85 to 4711.5 CNY/ha/year, approximately twice the local afforestation cost but one-sixth of the estimated total ecosystem service value. (3) While over 60% of respondents prefer compensation via governmental funds, there is notable and growing acceptance for development-oriented mechanisms like industrial collaboration and joint park construction under fiscal constraints. (4) Regression analysis indicates that occupation, annual income, and ecological cognition positively influence willingness, whereas age and household size show negative correlations; formal education level showed no significant impact. This study provides empirical evidence and a preference-based framework for setting scientifically grounded and socially accepted multifunctional ecological compensation standards in cross-regional watersheds.

1. Introduction

Forests simultaneously provide multiple products and services, such as timber production, hydrological regulation, carbon sequestration, soil erosion control, and biodiversity conservation [1,2], exhibiting the characteristics of non-rivalry and non-excludability inherent to public goods. The externality of these services often leads to market failures and under-provision [3]. Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) has thus been advocated as an economic instrument to incentivize forest managers by internalizing these externalities, based on the principle of “who benefits pays” [4,5].

However, the vast majority of current PES practices are single-targeted, designed to compensate for a single dominant service (e.g., water yield or carbon sequestration). While straightforward to implement, this traditional “single-function compensation” model overlooks the multifunctional nature of forest ecosystems [6]. Fundamentally, it differs from the emerging “multifunctional ecological compensation” in both methodological approach and practical implementation. The core objective of the traditional model is to incentivize and quantify the supply of one specific ecosystem service. Its assessment relies on a single proxy indicator directly linked to that service (e.g., a specific water quality parameter or carbon stock), and its payment mechanism is typically a linear payment based on that indicator [7]. This design can, in terms of management orientation, lead to lopsided and even unsustainable practices aimed at maximizing a single metric—for instance, prioritizing timber production may undermine soil and water conservation functions [8]. In contrast, multifunctional ecological compensation aims to optimize the synergistic supply and overall value of multiple ecosystem services, with the core objective of balancing trade-offs between different services to maximize total value [9]. Methodologically, this requires establishing a comprehensive evaluation system encompassing multiple service indicators to measure the outcomes of multi-objective synergistic management. Its payment mechanism necessitates designing more complex performance-based or bundled payment schemes based on the achievement of multiple targets [10]. Ultimately, this compensation model guides forest managers toward close-to-nature, sustainable multifunctional management, thereby enhancing the overall stability and service resilience of the ecosystem [11]. This shift from compensating for a single output to rewarding comprehensive, multifunctional management represents a fundamental evolution in PES design and is an essential requirement for supporting high-quality, sustainable forest governance [12].

Determining socially acceptable and economically viable compensation standards is crucial for the success of PES. The Contingent Valuation Method (CVM) has been widely used to assess residents’ willingness to pay (WTP) and willingness to accept (WTA) for ecosystem services, providing an important basis for trans-regional watershed compensation [13,14]. Existing research has revealed the influence of socio-economic factors, cognitive levels, and regional economic disparities on compensation willingness [15]. However, significant limitations persist in the current literature: First, most studies are confined to a single-function compensation framework and fail to integrate residents’ perceptions of forest multifunctionality and preference heterogeneity into compensation design [16]. Second, although the concept of multifunctional compensation has been proposed, its practical implementation pathways—particularly how to translate residents’ multifunctional preferences into specific compensation standards and differentiated mechanisms—remain underexplored [17,18]. Finally, existing CVM studies methodologically often focus merely on the simple calculation of willingness values, with insufficient exploration of preference heterogeneity [19,20]. There is also a scarcity of research that combines cognitive analysis with WTP/WTA valuation to jointly guide the innovative design of compensation mechanisms [21].

To address these challenges, this study introduces an integrated methodological innovation: the systematic combination of residents’ cognition of multifunctional forest services, heterogeneity preference analysis, and rigorous WTP/WTA valuation. Using the Jinghe River Basin in the Loess Plateau as a case study, this research investigates not only “how much” upstream and downstream residents are willing to pay or accept but also delves into “how their cognition, socio-economic characteristics, and preferences shape these values” and “how to design differentiated compensation mechanisms accordingly.” Specifically, this study aims to address the following core research questions: (1) What is the current state of residents’ cognition regarding the multifunctional services of forests in the Jinghe River Basin? How does this cognition influence their willingness to participate in ecological compensation? (2) Within the multifunctional management framework, what is the compensation standard range calculated based on residents’ WTP/WTA? How does this standard differ from single-function compensation standards? (3) Is there heterogeneity in residents’ preferences for different compensation methods (e.g., cash payments, industrial collaboration, technical compensation)? What are the underlying driving factors? By addressing these questions, this study aims to strengthen the theoretical and empirical foundations of multifunctional ecological compensation and provide policy-relevant insights for transitioning from single-function forest management and compensation toward integrated multifunctional approaches.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and relevant research ethics guidelines, and was reviewed and approved by the Academic and Ethics Committee of the Institute of Forest Ecology, Environment and Protection, Chinese Academy of Forestry. As this research primarily involved anonymous questionnaire surveys and posed minimal risk to participants, the committee issued an institutional statement confirming that the study design complied with ethical standards.

All questionnaire surveys and interviews were conducted with the informed consent of participants. Prior to data collection, each participant was clearly informed about the purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits of the study, and was explicitly notified of their right to withdraw at any time without any negative consequences. All participants provided written informed consent. All collected data were anonymized, used solely for academic research purposes, and kept strictly confidential.

2.2. The Study Area

As one of the major rivers in the Loess Plateau, the Jinghe River originates from Liupan Mountain in Ningxia and serves as a “mother river” flowing through three provinces/autonomous regions (Shaanxi, Gansu, and Ningxia). It sustains the production and domestic water needs of approximately 6.4 million people across 32 counties and cities, including southeastern Guyuan City (35°14′–36°31′ N, 105°19′–106°57′ E) in Ningxia, eastern Gansu (Longdong region), and northwestern Guanzhong in Shaanxi. The watershed covers an area of 45,421 km2, with an average annual precipitation of 400–600 mm and an average annual runoff of 320 million m3.

Upstream Representative Area: Guyuan City, Ningxia. Situated in the warm-temperate semi-arid climate zone of the Loess Plateau, Guyuan City exhibits a typical continental monsoon climate, with an average annual temperature of 7 °C, precipitation of 499.7 mm, and evaporation of 1364.4 mm. By the end of 2020, the city’s forestry land area amounted to 6,166,100 mu (411,073 hectares), with a forest area of 3,854,100 mu (256,940 hectares) and a forest coverage rate of 24.42%. According to 2022 data, its permanent population was 1,151,900. In 2024, the city’s gross domestic product (GDP) reached 46.373 billion Chinese Yuan (CNY), representing a 6.1% year-on-year increase at constant prices.

Downstream Representative Area: Pingliang City, Gansu. Located at 34°54′–35°43′ N, 107°45′–108°30′ E, Pingliang City in Gansu Province falls within the temperate continental semi-arid semi-humid climate zone, with an average annual temperature of 8.8 °C and precipitation ranging from 497.3 to 637.6 mm. Over the past three years, Pingliang has completed 860,000 mu (57,333 hectares) of land greening, achieving a forest and grass coverage rate of 44.7%. The city has a registered population of 2,285,000 and a permanent population of 1,772,700. In 2023, its gross domestic product (GDP) reached 66.86 billion Chinese Yuan (CNY), with a per capita GDP of 37,057 CNY.

2.3. Research Methods

2.3.1. Questionnaire Design

This study employed the contingent valuation method (CVM) to assess residents’ willingness to pay (WTP) and willingness to accept (WTA) compensation for multifunctional forest ecosystem services within the watershed. To ensure the validity of the CVM results, careful scenario design and bias control were implemented:

(1) Ecological perception and cognition, including respondents’ awareness, evaluation, and perceived importance of multiple ecosystem services provided by watershed forests, such as water regulation, soil conservation, carbon sequestration, biodiversity conservation, and ecological stability. These items were measured using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“very low”) to 5 (“very high”).

To integrate residents’ multidimensional perceptions of forest ecosystem services into a core explanatory variable, principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on the following five attitude statements measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “Strongly Disagree” to 5 = “Strongly Agree”): (1) Statement A: Forests can simultaneously provide multiple services such as timber, water conservation, and carbon sequestration. (2) Statement B: Strengthening forest construction in the upper reaches of the Jinghe River helps improve the ecological environment of the lower reaches. (3) Statement C: Many of the ecological services provided by forests cannot be valued by market prices. (4) Statement D: Downstream areas should benefit from ecological services and provide compensation to upstream areas for them. (5) Statement E: I have a personal responsibility to contribute to the ecological protection of the river basin. The data were deemed suitable for PCA. A principal component with an eigenvalue greater than 1 was extracted. The composite score of this principal component was defined as the “Ecological Cognition Composite Score” and was included as a continuous variable in subsequent econometric models.

(2) Economic valuation and payment vehicle, focusing on respondents’ willingness to pay (WTP) for ecological compensation (downstream residents) and willingness to accept (WTA) compensation (upstream residents and forest managers). An open-ended contingent valuation format was adopted to elicit the maximum amount respondents were willing to pay or the minimum amount they were willing to accept per hectare per year. Payment vehicles were explicitly defined as realistic and feasible channels, including direct cash payments, local government special funds, ecological taxes, and increased water tariffs, allowing respondents to select their preferred option and thereby enhancing the realism of the scenario.

To reduce hypothetical bias, the compensation mechanism was described as “being considered for implementation,” and its operational process and expected outcomes were explained to increase respondents’ engagement and the seriousness of their responses. To strike a balance between avoiding direct anchoring and providing a reasonable cognitive framework, three reference points were provided as background information before the valuation questions: (1) the current government subsidy standard for ecological public welfare forests (15 CNY·mu−1·yr−1); (2) the average annual afforestation cost per mu calculated over a 60-year rotation period (150 CNY·mu−1·yr−1); and (3) the estimated value of forest ecosystem services, including carbon sequestration and water conservation (1500 CNY·mu−1·yr−1) [22].

(3) Socio-economic characteristics, including gender, age, education level, household income, occupation, place of residence (urban/rural), and involvement in forest-related activities or institutions.

2.3.2. Sample Size and Sampling Strategy

Survey data were collected through both offline and online channels.

Offline survey: Conducted among permanent residents in the upstream area (Guyuan City, Ningxia) and downstream area (Pingliang City, Gansu) of the Jinghe River Basin. A combination of stratified random sampling and simple random sampling was applied to cover urban residents, rural residents, forest farm workers, watershed environmental managers, and government staff, ensuring occupational diversity. Because forest farm and government staff are more familiar with relevant policies, they were intentionally sampled in relatively higher proportions to capture expert perspectives.

Online survey: An unrestricted online questionnaire was distributed via internet platforms to collect independent views from the general public outside the watershed.

Potential sampling bias and treatment: Although the total sample size (n = 747) exceeded the minimum statistical requirement (n = 385) and the valid response rate exceeded 85%, some structural biases existed: (1) over-representation of policy-familiar groups (forest farm and government staff) in the offline sample, potentially inflating overall awareness levels; (2) self-selection bias in the online sample, which was dominated by younger and more highly educated respondents whose ecological awareness and WTP may be systematically higher. To address these issues and enhance robustness, statistical weighting was not applied. Instead, sub-sample regression analyses (upstream, downstream, and outside the watershed) combined with full-sample control variables were employed to explore behavioral mechanisms across groups, and sample limitations were explicitly acknowledged in the discussion.

Invalid Sample Exclusion Criteria: To ensure data quality, invalid questionnaires were excluded during the data cleaning phase based on the following criteria: (1) Incomplete Questionnaires: Questionnaires with extensive missing responses or with key items (e.g., WTP/WTA valuation, core perception items) left unanswered. (2) Missing or Contradictory Key Information: Questionnaires where socio-economic background information (e.g., income, occupation) was missing, or where responses contained obvious logical contradictions. (3) Non-compliant Age: Respondents under the age of 17 were excluded, as they may lack independent economic decision-making capacity and mature understanding of ecological compensation policies. After applying these exclusions, the final numbers of valid questionnaires obtained were 317 (upstream), 264 (downstream), and 166 (extra-basin), respectively (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Questionnaire Recovery Status.

2.4. Data Analysis Methods

2.4.1. Reliability and Validity Verification

Reliability analysis was conducted to assess the reliability and accuracy of responses to quantitative data, particularly cognitive and perceptual scale items. This study employed the X coefficient method to test reliability, with the formula expressed as:

Here, K represents the total number of items in the scale, denotes the variance of the scores for the i-th item, and represents the variance of the total scores for all items.

This survey required a confidence level of 95% and a sampling error not exceeding 5%. Based on the standard sample size formula for population proportion estimation, the minimum required sample size was calculated to be approximately 385. However, the actual sample size far exceeded this threshold. The survey achieved a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.907, indicating excellent reliability.

2.4.2. Econometric Model Specification and Hypotheses

Before analyzing the influencing factors of willingness to accept (WTA)/willingness to pay (WTP) compensation, several hypotheses were proposed:

Hypothesis 1.

Willingness to accept/pay compensation is negatively correlated with residents’ average age [23].

Hypothesis 2.

Ecological compensation willingness is positively correlated with educational attainment, as better-educated individuals are typically more forward-looking, pay greater attention to the ecological environment, and can more accurately recognize the value of ecological products provided by forests [24,25].

To identify the key factors influencing residents’ WTP/WTA decisions, this study employed a binary Logit model for regression analysis. The rationale for selecting this model is that the dependent variable in this study is a binary categorical variable (“willingness to pay/accept compensation”: 1 = yes, 0 = no). The Logit model is particularly suited for analyzing such binary choice problems. It maps the values of linear predictor variables onto the 0–1 probability interval via the logistic function, thereby effectively estimating the influence of various factors on the probability of choice. This is a well-established and standard method in environmental economics and willingness-to-pay research. Independent variables included: (1) gender; (2) age; (3) occupation (categorical, with “farmer” as the reference group); (4) education level; (5) household size; (6) individual annual income; and (7) the principal component score of “ecological awareness” extracted using PCA. The basic model specification is:

where is the probability that individual is willing to pay or accept compensation.

2.4.3. Expected Value

For the minimum ecological compensation standard funds that downstream residents of the watershed are willing to pay, the mathematical expectation (expected value) was calculated using the following formula:

where represents the minimum ecological compensation standard acceptable to residents (in CNY), denotes the value of the discrete random variable X, is the probability corresponding to the value X, and n is the number of samples willing to accept compensation at that specific amount (individuals).

3. Results

3.1. Basic Characteristics of the Sample

As shown in Table 2, the survey respondents were predominantly male across all regions, with the highest male proportion (59%) observed among those outside the watershed. The age distribution of respondents was concentrated in the 18–49 age group, accounting for approximately 80% of the sample. Upstream region: The proportions of respondents in the 18–29, 30–39, and 40–49 age groups were relatively close, at 26.2%, 28.7%, and 28.4%, respectively. Downstream region: The largest age groups were 30–39 (39.8%) and 40–49 (41.3%), together comprising over 80% of respondents. Outside the watershed: The age composition differed somewhat, with the largest group being 18–29-year-olds (38.9%), followed by 30–39-year-olds (25.7%) and 40–49-year-olds (16.2%).

Table 2.

Personal Information Variables and Assignments.

The educational attainment of respondents varied substantially across the upstream, downstream, and extra-watershed regions. Upstream region: Respondents with a bachelor’s degree constituted the largest group (117 individuals, 36.9% of the upstream sample). Downstream region: The proportions of respondents with junior high school, senior high school, vocational college, and bachelor’s degrees were relatively evenly distributed, each accounting for approximately 20%. Extra-watershed region: Respondents exhibited significantly higher educational levels, with bachelor’s degree holders (31.3%) and postgraduates or above (48.8%) collectively comprising nearly 80% of the sample (Table 2).

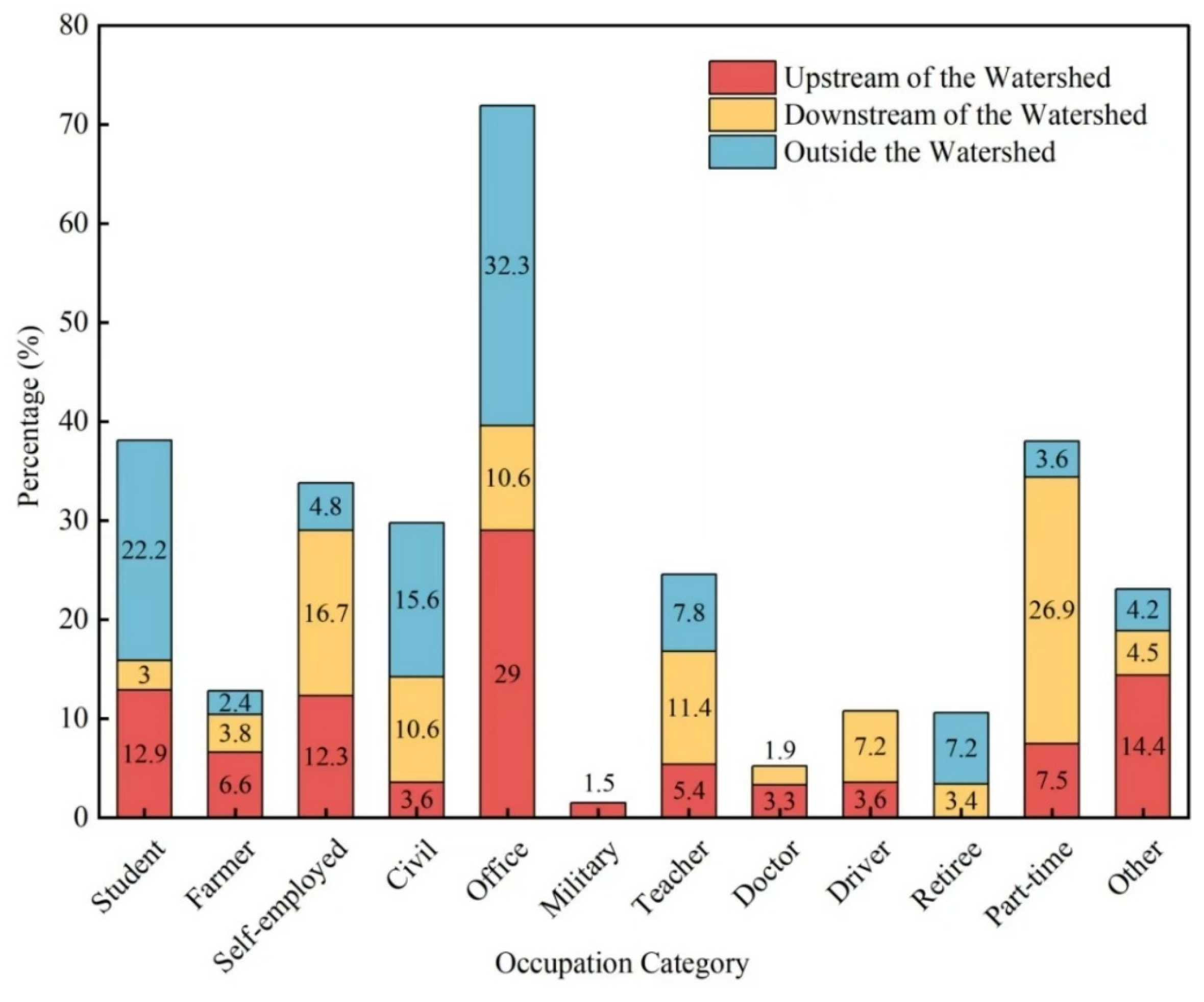

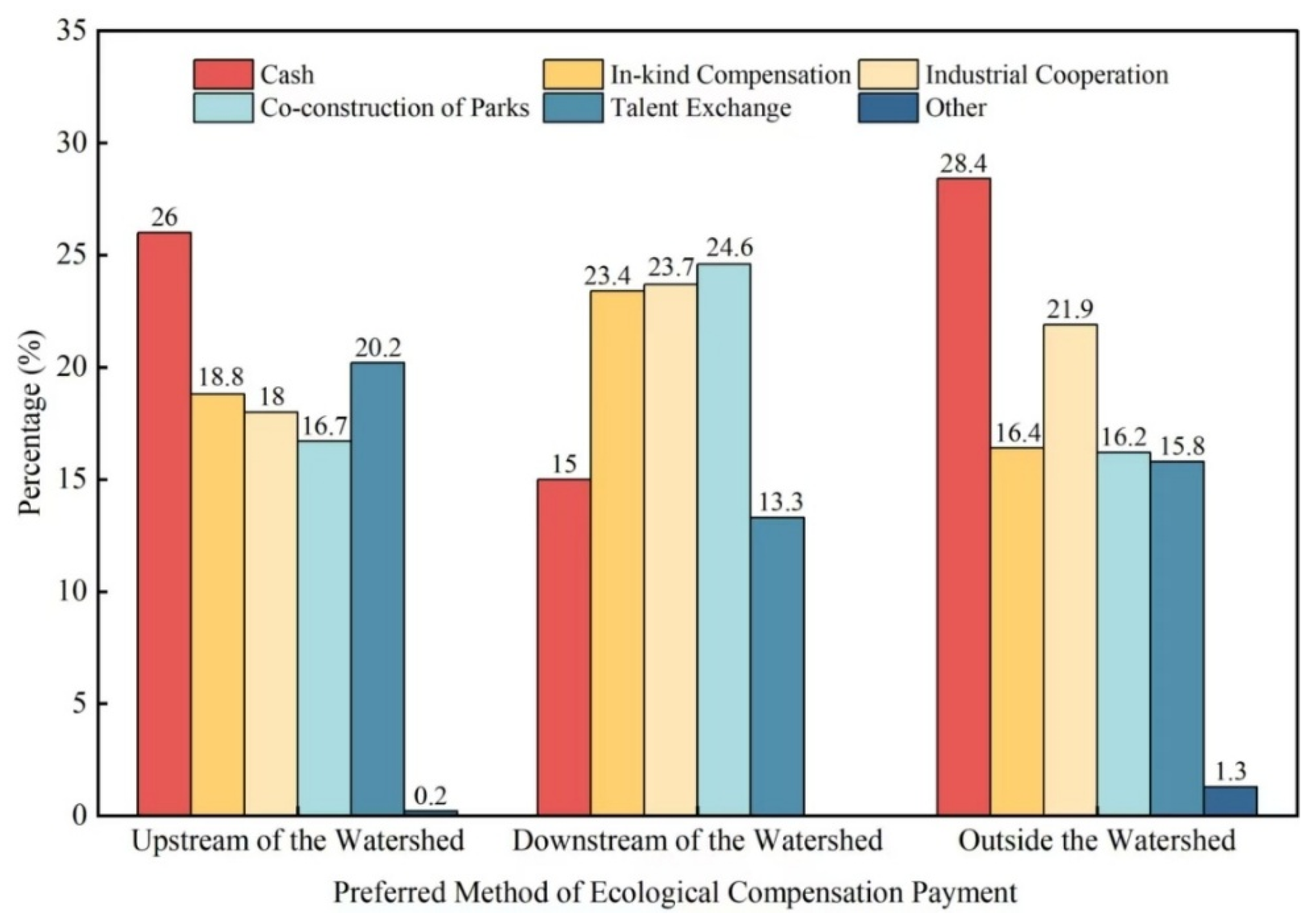

The occupations of respondents were primarily office clerks, part-time workers (farmers + migrant workers), self-employed individuals, and students. Upstream region: Respondents were predominantly office clerks, accounting for 29.0% of the sample. Downstream region: The largest occupational group was part-time workers (farmers + migrant workers), comprising 26.9% of respondents. Extra-watershed region: Office clerks constituted the highest proportion (32.3%), followed by students (22.2%) and civil servants (15.6%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Occupation Types of Respondents.

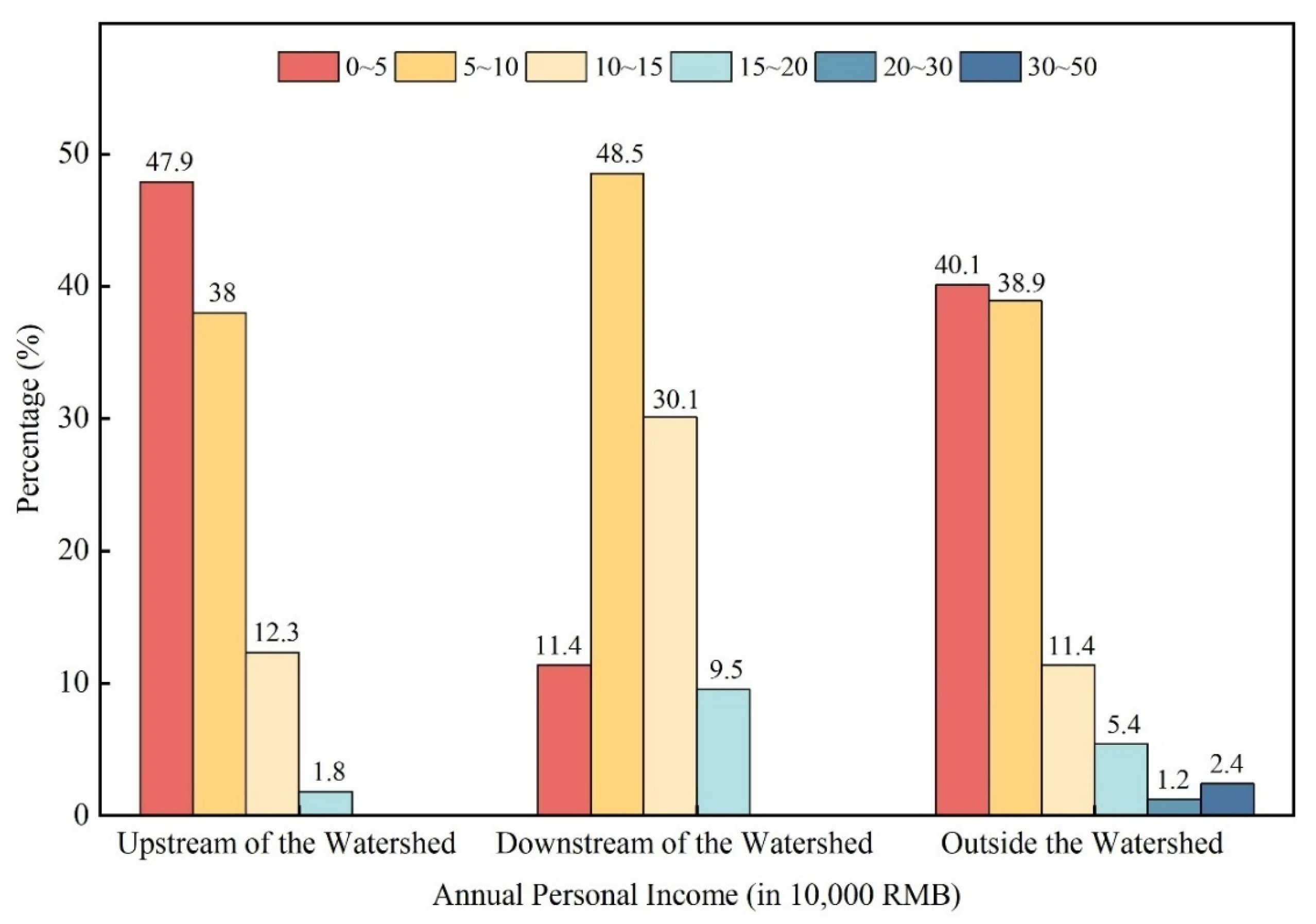

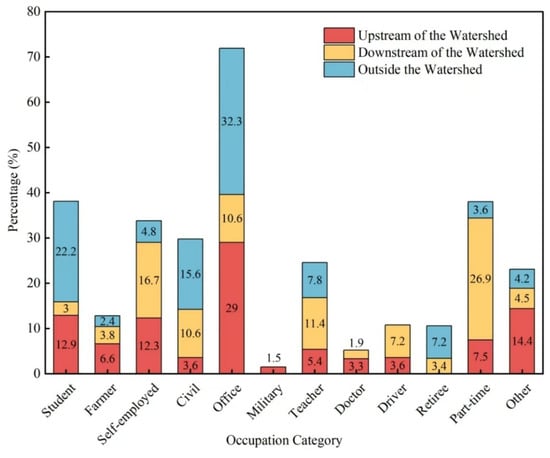

Respondents’ personal annual incomes were predominantly low, with most below CNY 100,000. Upstream region: The proportions of personal annual income in the CNY 0–50,000 and CNY 50,000–100,000 brackets were 47.9% and 38.0%, respectively. Downstream region: Personal annual income was higher than in the upstream region, with the largest proportions in the CNY 50,000–100,000 (48.5%) and CNY 100,000–150,000 (30.1%) brackets. Extra-watershed region: The CNY 0–50,000 (40.1%) and CNY 50,000–100,000 (38.9%) brackets accounted for the largest shares of personal annual income (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Respondents’ Personal Income Profile.

3.2. Residents’ Awareness and Understanding of Ecological Compensation Policy

In this survey, the vast majority of respondents recognized that forests have multiple service functions. Extra-watershed region: The highest proportion of aware respondents (96.3%) was observed. Downstream region: The lowest awareness rate (71.6%) was recorded, with 11.7% and 16.7% of respondents indicating they were unaware or unsure, respectively. Upstream region: Awareness stood at 88.3%.

Over half of respondents in the Jinghe River Basin reported having heard of ecological compensation policies and being exposed to knowledge about multifunctional forest management and forest multifunctional ecological compensation (concepts, policies, methods), with the downstream region exhibiting the highest proportion (70.1%). The majority of respondents across all regions believed that strengthening forest ecological construction in the upstream Jinghe River Basin could improve downstream ecological environments to some extent, with proportions of 86.7% (upstream), 71.6% (downstream), and 94.6% (extra-watershed).

Regardless of region, most respondents agreed that forest protection and scientific forest management in the upstream Jinghe River Basin should receive ecological compensation. Notably, data from the broader extra-watershed survey area showed that 93.4% supported compensation, while 18.9% of downstream residents still indicated that compensation should not be provided (Table 3).

Table 3.

Forest Farmers’ Perceptions of Ecological Compensation.

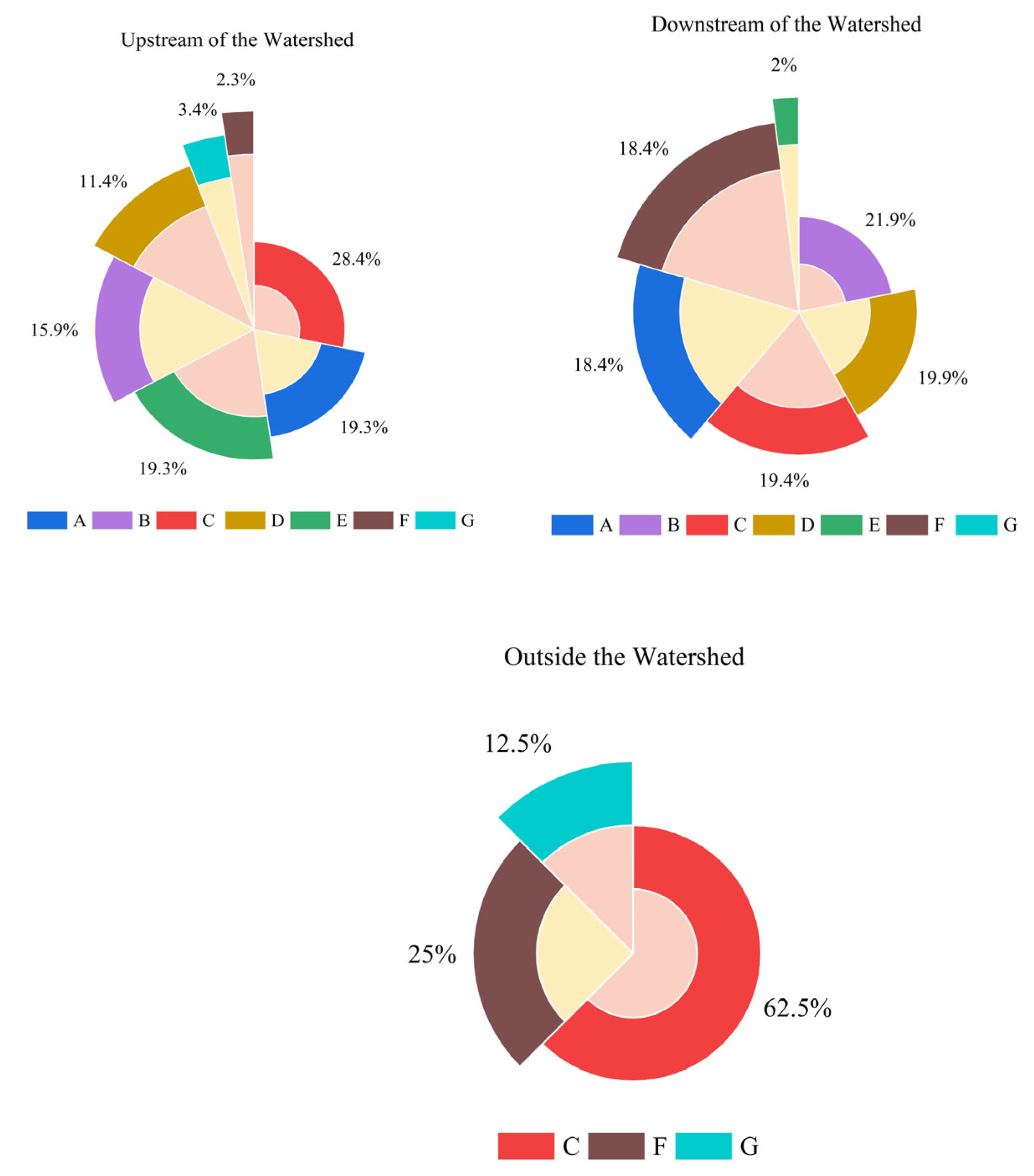

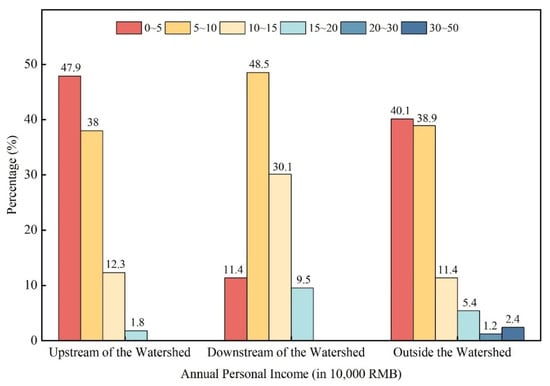

In the survey on why downstream regions do not support forest ecological compensation for upstream areas, the most frequently cited reason by upstream respondents was “Relevant authorities can fully cover the costs of forest ecological protection and construction in the upstream Jinghe River Basin,” accounting for 28.4%. This was followed by “Upstream areas have not contributed to forest resource and ecological environment protection in the Jinghe River Basin” and “High household economic income, no need for compensation,” each comprising 19.3%. These three reasons collectively accounted for nearly 70% of responses. Downstream respondents cited more diverse reasons for opposing compensation. Proportions were similar for “Upstream areas have not contributed to forest resource and ecological environment protection in the Jinghe River Basin,” “The current forest resources and ecological environment in the Jinghe River Basin are already good, requiring no compensation,” “Relevant authorities can fully cover the costs of forest ecological protection and construction in the upstream Jinghe River Basin,” and “Jinghe River Basin forest ecological environment is irrelevant to me”—each accounting for approximately 20%. Additionally, about 20% of respondents chose “Other,” indicating that the questionnaire design failed to fully capture the downstream respondents’ concerns. Among extra-watershed respondents, the dominant reason (62.5%) was “Relevant authorities can fully cover the costs of forest ecological protection and construction in the upstream Jinghe River Basin” (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Reasons for Respondents’ Opposition to Ecological Compensation. Note: A: The upstream area has not made contributions to the forest resources and ecological environment protection of the Jinghe River Basin; B: The forest resources and ecological environment of the Jinghe River Basin are currently in good condition and do not require compensation; C: The costs for forest ecological environment protection and construction in the upstream area of the Jinghe River Basin can be fully covered by the relevant departments; D: The forest ecological environment of the Jinghe River Basin has nothing to do with me; E: My family has a relatively high income and does not need compensation; F: Other; G: Can’t say it clearly.

3.3. Residents’ Willingness to Pay (WTP)/Willingness to Accept (WTA) Compensation

3.3.1. Influencing Factors of Residents’ Willingness to Accept (WTA)/Willingness to Pay (WTP) Compensation

Based on these hypotheses, six indicator variables were selected—gender, age, occupation, educational level, household size, and respondents’ personal annual income—to develop a model and conduct statistical analysis, aiming to identify the factors influencing residents’ WTA/WTP compensation willingness. The empirical results partially support these hypotheses. As shown in Table 4, the Logit regression results indicate that age, occupation, household size, and individual annual income have statistically significant effects on residents’ willingness to pay or accept ecological compensation. Age is significantly and negatively associated with compensation willingness, providing support for Hypothesis 2. In contrast, education level does not exhibit a statistically significant effect, and therefore Hypothesis 2 is not supported. With respect to Hypothesis 1, gender does not show a statistically significant association with compensation willingness in the regression results, indicating that Hypothesis 1 is not supported. In addition, occupation, household size, individual annual income, and ecological cognition (PCA score) exhibit statistically significant effects. Household size shows a significant negative association, whereas occupation, annual income, and ecological cognition are positively associated with compensation willingness.

Table 4.

Binary Logistic Regression Results for Willingness to Accept Compensation.

3.3.2. Residents’ Average Willingness to Pay (WTP)/Willingness to Accept (WTA) Compensation

As shown in Table 5, the average minimum ecological compensation amount acceptable to upstream respondents was 314.10 CNY per mu per year (WTA), while downstream respondents’ average minimum willingness to pay (WTP) for ecological compensation was 289.59 CNY per mu per year. For residents surveyed outside the watershed, the average minimum ecological compensation amount they found acceptable was 506.32 CNY per mu per year (WTA).

Table 5.

Minimum Acceptable Ecological Compensation Amounts by Region.

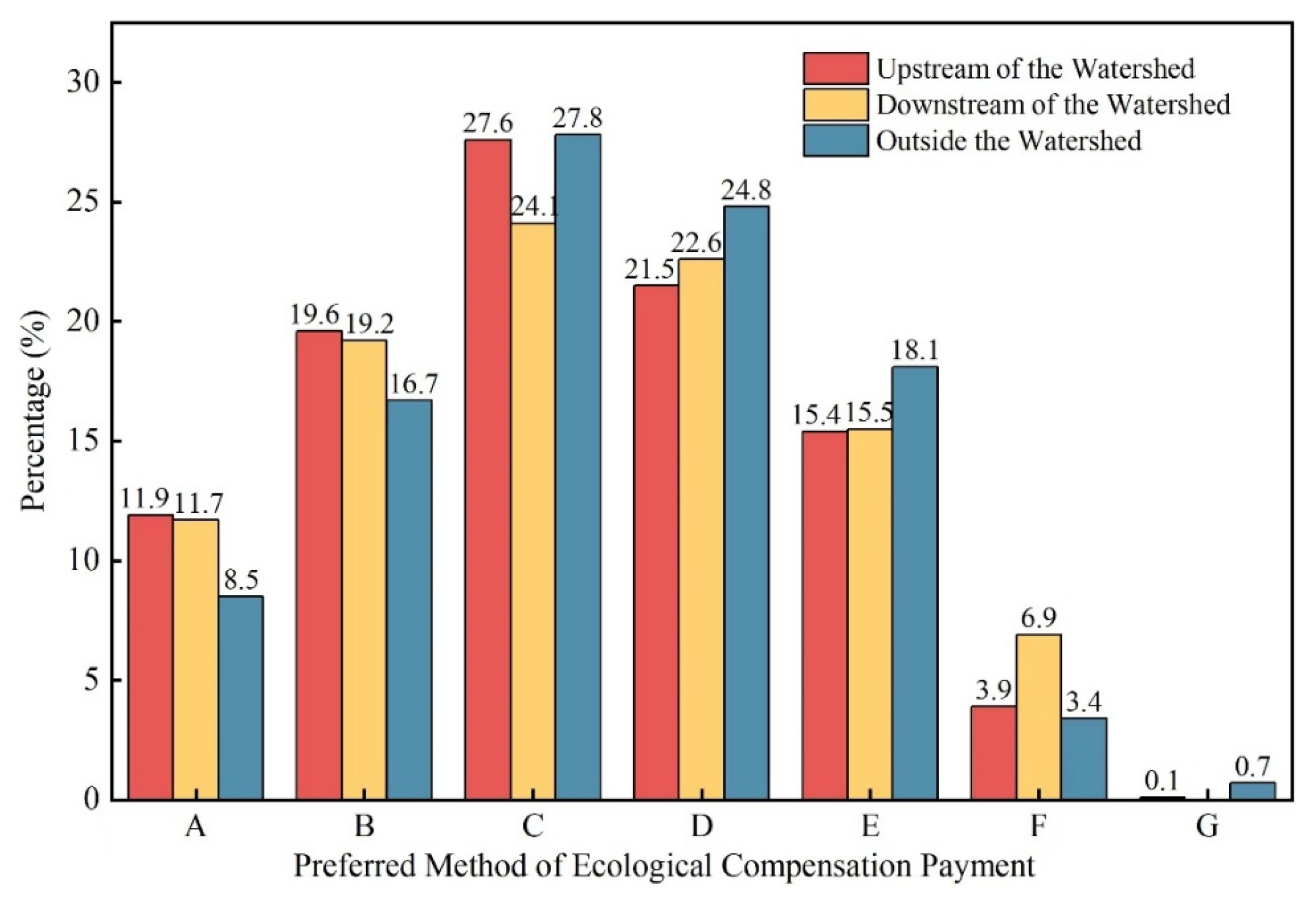

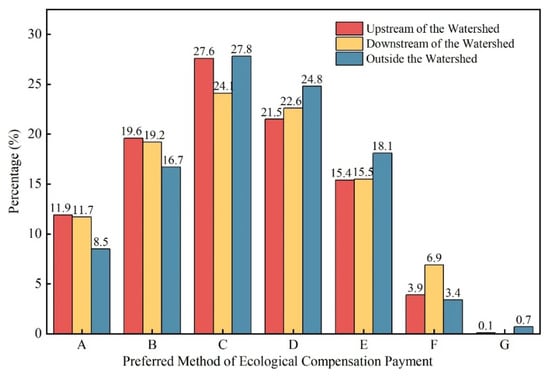

3.4. Residents’ Preferred Compensation Methods

Regarding residents’ preferred methods for raising ecological compensation funds, respondents from the upstream, downstream, and extra-watershed regions showed similar preferences, with the most frequently selected options being central government special funds, local government special funds, corporate donations, and ecological taxes. Central government special funds had the highest proportion across all regions, accounting for 27.6% (upstream), 24.1% (downstream), and 27.8% (extra-watershed), respectively. Local government special funds were the second most preferred, with proportions of 21.5% (upstream), 22.6% (downstream), and 24.8% (extra-watershed). In the upstream and downstream regions, respondents chose corporate donations slightly more frequently than ecological taxes, while extra-watershed respondents showed the opposite preference, with ecological taxes selected more often than corporate donations (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Residents’ Preferred Ecological Compensation Fund-Raising Methods. Note: A represents individual donations; B represents corporate donations; C represents central government special funds; D represents local government special funds; E represents ecological taxes; F represents water price increases; G represents other.

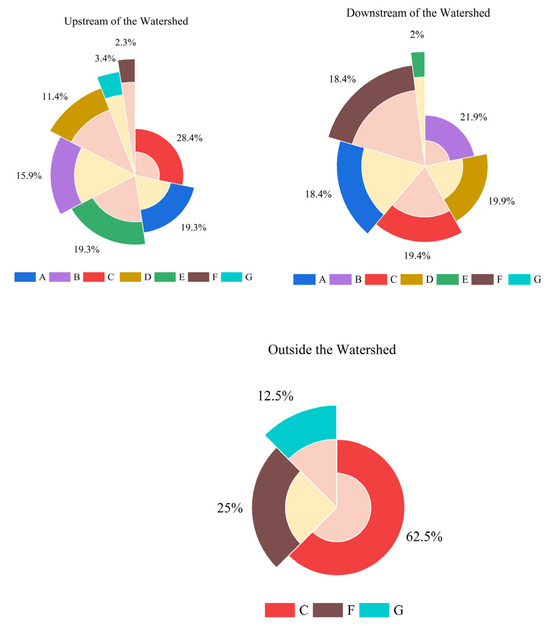

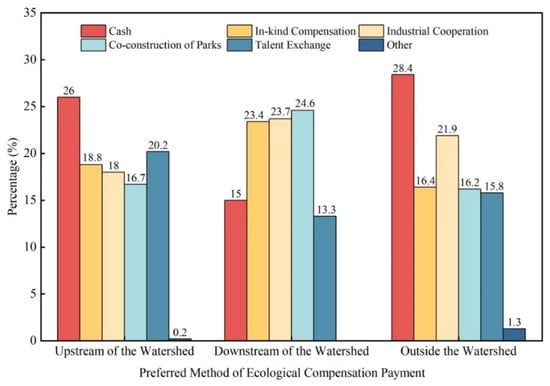

Regarding ecological compensation payment methods: Upstream region (as the compensated party): Cash payments were the most frequently chosen method, accounting for 26.0% of respondents, followed by talent exchange (20.2%). Downstream region (as the paying party): The top choices were joint industrial park development (24.6%), industrial collaboration (23.7%), and in-kind compensation (23.4%). Extra-watershed region: Cash compensation was preferred by 28.4% of respondents, followed by industrial collaboration (21.9%) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Residents’ Preferred Ecological Compensation Payment Methods.

4. Discussion

4.1. Ecological Awareness and Equitable Compensation Standards Among Residents in the Jinghe River Basin

River basin residents are critical stakeholders in ecological compensation, with their decision to engage stemming from a synthesis of rational and emotional factors rooted in their ecological awareness [26]. Research indicates that awareness of ecological value significantly and positively influences residents’ willingness to participate in conservation efforts [27]. This study found a high baseline awareness of forests’ multiple ecosystem services among residents, with recognition rates of 86.2% (upstream), 71.6% (downstream), and 95.8% (extra-watershed). There is a widespread acknowledgment of the connection between upstream forest management and downstream environmental quality.

However, a critical gap persists: 30–40% of residents remained unaware or unclear about specific ecological compensation policies. This deficiency directly undermines participation and willingness to pay, corroborating findings from other basins that higher policy awareness correlates with greater engagement [18]. Therefore, it is essential to enhance public understanding through diversified communication, fostering the perception that watershed ecological compensation is a shared responsibility requiring active public participation, not solely a governmental obligation.

This context of awareness is crucial for interpreting and determining equitable compensation standards—a core yet challenging aspect of research on forest ecological benefit compensation [28]. By integrating an evaluation of forest multifunctionality with questionnaire surveys on compensation willingness, this study derived a standard range. The calculated willingness to pay (WTP) and willingness to accept (WTA) are 289.59 and 314.10 CNY per mu per year, respectively, translating to a range of 4343.85–4711.5 CNY per hectare per year.

Positioning this standard within broader economic and regional contexts reveals several key insights. First, compared to a local study in the Liupanshan area [22], this standard is approximately twice the afforestation cost (2036 CNY/ha/a) but only about one-sixth of the estimated total forest ecosystem service value (27,253 CNY/ha/a). This indicates that while the derived standard surpasses basic costs, it still captures only a fraction of the total ecological value generated. Second, the significant disparity between current national compensation standards (225 CNY/ha/a) and both this study’s range and farmers’ expectations underscores that existing schemes fail to fully reflect the value of multifunctional services or compensate for positive externalities, thereby weakening conservation incentives.

A cross-basin comparison demonstrates that compensation standards are highly context-dependent, shaped by local economic levels, ecosystem conditions, and environmental awareness [29]. For instance, WTA in the arid Shiyang River Basin (8787.61 CNY/ha/a) far exceeds the value found in the Jinghe River Basin, likely due to more severe water scarcity and higher opportunity costs [30]. Conversely, a proposed standard in the economically less developed Chishui River Basin (approximately 443 CNY/ha/a) is significantly lower [31]. Research in the Xijiang River Basin further corroborates the positive correlation between regional economic development and WTP [32]. These variations emphasize that effective, socially accepted compensation standards cannot be uniform but must be calibrated to local socioeconomic and ecological realities.

4.2. Residents’ Awareness and Compensation Standards: A Behavioral Economics Perspective

The observed gap between the willingness to accept (WTA) of upstream residents and the willingness to pay (WTP) of downstream residents is a core phenomenon prevalent in environmental valuation [32]. Beyond the traditional “cost-bearer vs. beneficiary” role explanation, insights from behavioral economics, specifically loss aversion and the endowment effect, offer a deeper understanding of this disparity. For upstream residents, the developmental restrictions imposed by forest conservation are perceived as a “loss.” Individuals typically assign a much higher psychological weight to losses than to gains of equivalent magnitude [33]. Consequently, the compensation they demand (WTA) must not only cover direct costs but also include a substantial premium to offset this subjective sense of loss. Conversely, downstream residents view payment as an “expenditure” for acquiring future ecological benefits, a decision based on an assessment of gains, which naturally leads to more conservative valuations. This decision-making framework, rooted in different mental accounting and reference points, constitutes the fundamental behavioral mechanism causing WTA to systematically exceed WTP.

Furthermore, the pervasiveness of this gap is also influenced by institutional and cognitive legitimacy. The study reveals that despite policy outreach, a significant portion of residents remain unclear about the rights and responsibilities associated with ecological compensation. In the absence of a clear, legally binding framework for horizontal compensation, upstream residents may develop a perception of “entitlement to compensation” based on their role as “ecological guardians,” thereby inflating their compensation expectations [34]. Simultaneously, the existing low-level, universal national ecological subsidies may inadvertently serve as a psychological anchor. This can lead some downstream residents to believe “the government is already responsible,” while failing to meet the threshold required to incentivize higher-level multifunctional management upstream, thereby objectively maintaining a low-level equilibrium gap between payment and compensation expectations. Thus, the WTA-WTP gap is not merely an outcome of economic calculation but a product shaped jointly by the specific institutional environment and psychological cognition [35].

4.3. Socioeconomic and Cognitive Drivers of Ecological Compensation Preferences

This study integrates descriptive statistics and econometric results to explore the mechanisms shaping residents’ willingness to pay (WTP) and willingness to accept (WTA) for ecological compensation in the Jinghe River Basin. Consistent with previous studies, residents’ participation in ecological compensation is jointly influenced by external institutional contexts and internal socioeconomic and cognitive factors [36]. Economic conditions play a foundational role: household income significantly affects both WTP and WTA, as higher-income individuals generally possess greater payment capacity and risk tolerance [37,38,39].

Our results further confirm that occupation and income are among the most significant determinants of compensation preferences. Office workers and students exhibit significantly higher WTP than farmers, reflecting not only their relatively stable economic conditions but also their greater access to information, familiarity with policy instruments, and stronger recognition of long-term ecological benefits. In contrast, upstream farmers, as direct providers of ecosystem services and bearers of opportunity costs, express stronger WTA and a marked preference for direct cash compensation. Age and household size show consistently negative effects on both WTP and WTA, indicating that family life-cycle stage and economic burden impose important constraints on compensation decisions. Older respondents and those with larger households tend to adopt more conservative financial strategies and are more sensitive to the adequacy of compensation levels. An important and somewhat unexpected finding is that formal educational attainment does not exert a statistically significant direct effect on WTP or WTA. This contrasts with some earlier studies (e.g., Jie et al., 2011) but aligns with Ren et al. (2023), who reported only weak positive effects of education on WTP [40,41]. We suggest that in the context of prolonged policy promotion and environmental communication in China, formal education is no longer the sole or dominant channel shaping environmental awareness. Instead, integrated ecological cognition formed through occupational experience, media exposure, and community interaction—captured here by the PCA-derived ecological cognition index—plays a more direct and robust role in motivating compensation behavior. This underscores the importance of cognitive and perceptual factors in translating abstract ecological values into concrete economic decisions.

Notably, the robust statistical significance of the ecological cognition component highlights the critical role of integrated cognitive formation in translating ecological values into actual payment behavior. Comparisons of effect magnitudes further indicate that, after controlling for other variables, economic factors (income) and cognitive factors (PCA scores) act as the two primary drivers of willingness, whereas demographic characteristics (age and household size) mainly operate as constraining factors.

4.4. From Social Preferences to Policy Practice: A Prudent Pathway for Establishing Multifunctional Ecological Compensation Standards

The residents’ willingness to pay and willingness to accept revealed in this study provide important social preference evidence for formulating multifunctional ecological compensation policies in the watershed. However, it must be clearly recognized that the standard derived from the Contingent Valuation Method (CVM) is essentially an exploratory benchmark of social acceptability, not a precise and directly enforceable policy value. Therefore, we propose a “calibration-iteration” policy translation framework to prudently transform social preferences into operable and sustainable compensation mechanisms.

Phase 1: Using social willingness as a negotiation benchmark. The compensation range identified in this study (4343.85–4711.5 CNY·ha−1·yr−1) should serve as a socio-political reference point for policy discussion. Its value lies in reflecting local residents’ recognition of ecological value and their payment willingness, providing an empirical starting point for cross-regional negotiations. At the same time, its origin from a specific sample and methodology must be openly explained to avoid direct application.

Phase 2: Comprehensive calibration with multi-dimensional evidence. The social willingness benchmark needs to be calibrated against other key evidence: on one hand, cost-based accounting (e.g., management costs, opportunity costs for upstream landowners) determines the “floor price” of compensation to ensure feasibility; on the other hand, ecosystem service value assessment (e.g., quantification of hydrological regulation, carbon sequestration, etc.) informs the “ceiling price,” reflecting ecological outputs. Mechanism design should be diversified and differentiated, combining fiscal transfers, industrial collaboration, technical compensation, and other means, with particular attention to the relatively higher willingness to pay downstream and the preference for cash compensation upstream.

Phase 3: Piloting first and dynamic iteration. The final policy scheme should be validated and optimized through small-scale, time-bound pilot programs in representative sub-watersheds. Using the compensation range and mechanisms formed in the first two phases as a starting point, continuous monitoring of ecological outcomes, socioeconomic impacts, and stakeholder feedback should be conducted, and the compensation standards, payment conditions, and supporting measures should be dynamically adjusted accordingly, thereby completing a robust transition from “stated preferences” to “revealed behavior.”

5. Conclusions and Limitations

5.1. Main Conclusions

(1) Residents in the watershed exhibit a relatively high level of awareness of the multifunctional ecosystem services provided by forests (70%–95%) and generally recognize the ecological interdependence between upstream and downstream regions. However, awareness of specific ecological compensation policies remains limited, with approximately 30%–40% of respondents reporting that they are not familiar with such policies.

(2) The average willingness to accept (WTA) among upstream residents is 314.10 CNY·mu−1·yr−1, while the average willingness to pay (WTP) among downstream residents is 289.59 CNY·mu−1·yr−1. After conversion, this corresponds to a compensation standard ranging from 4343.85 to 4711.50 CNY·ha−1·yr−1, which is approximately twice the actual afforestation cost but only about one-sixth of the estimated ecosystem service value.

(3) Residents’ preferred compensation mechanisms are becoming increasingly diversified. Although more than 60% of respondents still prefer government-funded compensation, development-oriented approaches such as industrial cooperation and joint industrial park development receive broad acceptance when fiscal resources are constrained.

(4) Occupation, individual annual income, and ecological cognition are key factors that exert significant positive effects on compensation willingness, whereas age and household size show significant negative correlations. Formal educational attainment does not exhibit a statistically significant direct effect.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study has several limitations. First, the inherent hypothetical bias of the CVM cannot be fully eliminated; stated preferences may exceed actual payment behavior. Second, while the sample size is sufficient, the potential over-representation of specific groups (e.g., those familiar with policies) in its structure may affect the inference of willingness values to the general population. Furthermore, the valuation of “multifunctionality” is relatively holistic and does not disaggregate to the marginal value of individual service functions. Future research could deepen in the following directions. First, employing methods like choice experiments that better parse attribute preferences to further clarify residents’ WTP for specific forest ecosystem services and their trade-offs. Second, conducting longitudinal studies to compare residents’ stated preferences with their actual behavior under real compensation schemes to validate and calibrate preference assessment methods. Third, exploring integrated modeling that combines social preference data with biophysical models and cost–benefit analysis to develop more operational, spatially explicit optimization schemes for ecological compensation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.W. and Y.W.; methodology, X.W.; software, L.S.; validation, L.S. and Y.W.; formal analysis, X.W.; investigation, L.S.; resources, Y.W.; data curation, L.S. and X.W.; writing—original draft preparation, X.W.; writing—review and editing, X.W. and Y.W.; visualization, X.W.; supervision, X.W.; project administration, X.W.; funding acquisition, X.W. and Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number U20A2085), Liupanshan National Nature Reserve Ecological Protection and Restoration Project (grant number 91117-2024).

Data Availability Statement

The original survey data presented in this study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions. Data supporting the reported results can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Costanza, R.; d’Arge, R.; Groot, R.D.; Farber, S.; Grasso, M.; Hannon, B.; Limburg, K.; Naeem, S.; O’Neill, R.V.; Paruelo, J.; et al. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 1997, 387, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pukkala, T. Which type of forest management provides most ecosystem services? For. Ecosyst. 2016, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Lou, G.; Yao, J. Research on the profit contribution of forest ecological benefits based on policy and market-tools compensation projects in nanping. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindhjem, H.; Mitani, Y. Forest owners’ willingness to accept compensation for voluntary conservation: A contingent valuation approach. J. For. Econ. 2012, 18, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayrand, K.; Paquin, M. Payment for environmental services: A survey and assessment of current schemes. J. Helminthol. 2004, 1, 77–80. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chang, L.; Cheng, Y.; Cao, S. A method of evaluating ecological compensation under different property rights and stages: A case study of the Xiaoqing River Basin, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Xu, T.; Wang, B. Payments for forest ecosystem services in China: A multi-function quantitative ecological compensation standard based on the Human Development Index. Front. Earth Sci. 2025, 13, 1447513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmonds, J.S.; Sonter, L.J.; Watson, J.E.M.; Bennun, L.; Costa, H.M.; Dutson, G.; Edwards, S.; Grantham, H.; Griffiths, V.F.; Jones, J.P.; et al. Moving from biodiversity offsets to a target-based approach for ecological compensation. Conserv. Lett. 2020, 13, e12695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Shen, J.; He, W.; Sun, F.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, C.; Kong, Y.; An, M.; Yuan, L.; et al. Changes in ecosystem services value and establishment of watershed ecological compensation standards. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zabel, A.; Roe, B. Optimal design of pro-conservation incentives. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 69, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggers, J.; Melin, Y.; Lundström, J.; Bergström, D.; Öhman, K. Management strategies for wood fuel harvesting—Trade-offs with biodiversity and forest ecosystem services. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asbjornsen, H.; Wang, Y.; Ellison, D.; Ashcraft, C.M.; Atallah, S.S.; Jones, K.; Mayer, A.; Altamirano, M.; Yu, P. Multi-targeted payments for the balanced management of hydrological and other forest ecosystem services. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 522, 120482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, P.; Mohan, K.C.; Shrestha, S.; Aryal, A.; Shrestha, U.B. Assessments of ecosystem service indicators and stakeholder’s willingness to pay for selected ecosystem services in the Chure region of Nepal. Appl. Geogr. 2016, 69, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Li, W.H.; Zhen, L.; Huang, H.Q.; Wei, Y.J.; Naomi, I. Estimating eco-compensation requirements for forest ecosystem conservation: A case study in Hainan province, southern China. Outlook Agric. 2011, 40, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.A.; Clarkson, B.D.; Barton, B.J.; Joshi, C. Implementing ecological compensation in New Zealand: Stakeholder perspectives and a way forward. J. R. Soc. N. Z. 2014, 44, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Ni, H.; Zhang, Q. Eco-compensation practice in China’s river basins. In Proceedings of the 2017 3rd International Forum on Energy, Environment Science and Materials (IFEESM 2017); Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Clot, S.; Grolleau, G.; Méral, P. Payment vs. compensation for ecosystem services: Do words have a voice in the design of environmental conservation programs? Ecol. Econ. 2017, 135, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, W.P.; Zhen, L.; Xiao, Y. Distinct eco-compensation standards for ecological forests in Beijing. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2019, 39, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.H.; Wang, H.J.; Wang, H.L.; Chen, C.Y. An introduction to framework of assessment of the value of ecosystem services. Prog. Geogr. 2012, 21, 963–969. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, J.; Yan, Y.; Wang, D. Principal analysis and method improvement on cost calculation in watershed ecological com-pensation. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2010, 30, 0221–0227. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, S.; Zhang, C.; Liu, C.; Liu, X.; Xie, G. Forest ecological compensation standard based on spatial flowing of water services in the upper reaches of Miyun Reservoir, China. Ecosyst. Serv. 2019, 39, 100983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, L.X. Study on Ecological Compensation Standard of Residents in Jing River Watershed of Liupan Mountains Area, Ningxia. Master’s Thesis, Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, Hohhot China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, B.; Wang, Y.; Hao, J.; Liu, Y.; Bohnett, E.; Zhang, K. Optimizing stand structure for trade-offs between overstory timber production and understory plant diversity: A case-study of a larch plantation in northwest China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2018, 29, 2998–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.G.; Huang, X.J.; Lu, Y.X. The willingness to accept of farm households for preserving farmland and its driving mechanism. China Land Sci. 2009, 23, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackl, F.; Halla, M.; Pruckner, G.J. Local compensation payments for agri-environmental externalities: A panel data analysis of bargaining outcomes. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2007, 34, 295–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.N.; Ge, Y.X.; Jie, Y.M.; Zheng, Y.C. A study on the influence of ecological cognition on river basin residents’ willingness to participate in ecological compensation. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. 2019, 29, 109–116. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, H.T.; Sun, D.C.; Xu, T.; Zhao, M.J. The Influence Mechanism of Ecological Value Cognition on Farmers’ Willingness to Participate in Ecological Management: An Example from Weihe Basin in Shaanxi Province. China Rural Surv. 2017, 2, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Chi, C.; Huang, X.; Gao, X.; Hu, P. Horizontal Ecological Compensation of Watershed from the Perspective of Ecosystem Services Flow: A Case of the Yangtze River Mainstream. Econ. Geogr. 2025, 45, 133–145. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K. The Ecological Compensation Standard Study Based on Double-Bounded Dichotomous CVM. Master’s Thesis, Northeast Agricultural University, Harbin, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, W.P.; Zhen, L.; Xie, G.D.; Xiao, Y. Determining eco-compensation standards based on the ecosystem services value of the mountain ecological forests in Beijing, China. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 26, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Robinson, B.E.; Liang, Y.C.; Polasky, S.; Ma, D.C.; Wang, F.C.; Ruckelshaus, M.; Ouyang, Z.Y.; Daily, G.C. Benefits, costs, and livelihood implications of a regional payment for ecosystem service program. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 16681–16686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Yang, L.; Min, Q. Establishment of an eco-compensation fund based on eco-services consumption. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 211, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Zhang, S.; Lu, Y.; Li, Q. Determining the ecological compensation standard based on forest multifunction evaluation and financial net present value analysis: A case study in southwestern Guangxi, China. J. Sustain. For. 2020, 39, 730–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, T.; Berhane, T.; Mulatu, D.W.; Rannestad, M.M. Willingness to accept compensation for afromontane forest ecosystems conservation. Land Use Policy 2011, 105, 105382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, N.; Li, D.; Zhang, S.; Shi, K.; Chen, W. Research on subsidy standards for public welfare forests based on a dynamic game model—Analysis of a case in Jiangxi, China. Front. For. Glob. Change 2023, 6, 1192140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southgate, D.; Wunder, S. Paying for watershed services in Latin America: A review of current initiatives. J. Sustain. For. 2009, 28, 497–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.L.; Zhu, Z.L.; Ren, K.L. Farmers’ participation and influencing factors in payments for environmental services in limited developing ecological zones: A case of Yanchi County in Ningxia Province. J. Arid Land. 2018, 41, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, X.C.; Luo, X.F.; Huang, Y.Z.; Tang, L. Relationship between policy incentives, ecological cognition, and organic ferti lizer application by farmers: Based on a moderated mediation model. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2021, 29, 1274–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, Y.M.; Ge, Y.X.; Xu, G.L. Analysis of the degree of awareness and willingness to pay for ecological compensation among residents in the lower reaches of the yellow river: Based on a questionnaire survey in shandong province. Issues Agric. Econ. 2011, 32, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.L.; Kuang, Y. Progresses, predicaments and optimization paths of transverse watershed ecological compensation in the Yangtze river economic belt. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Bas. 2023, 40, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.