Abstract

Wood-based materials in the form of wood veneer composites (WVCs) possess a high lightweight construction potential for load-bearing applications in mechanical engineering due to their high strength properties combined with low density. However, in order to substitute energy-intensive metallic construction materials (such as steel or aluminum), additional structural space is required to compensate for the comparatively low stiffness by means of the area moment of inertia. Under bending loads, an increase in cross-sectional height at a constant span length leads to elevated shear stresses. Owing to the low shear strength and stiffness of wood-based materials, the influence of shear stresses must be considered in both the design of wooden components and in material testing. Current standards for determining the bending properties of wood-based materials only describe methods for assessing pure bending behavior, without accounting for shear effects. The present contribution introduces a method for determining both bending and shear properties of WVC using the three-point bending test. This approach allows for the derivation of bending and shear modulus values through an analytical model based on Timoshenko beam theory by testing various span-to-height ratios. These modulus values represent material constants and enable the numerical design of wooden components for arbitrary geometric parameters.

1. Introduction

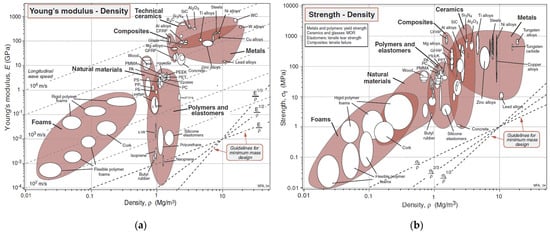

The main application areas of wood are in the energy and chemical sectors, the paper industry, and, in processed form as wood-based materials, in furniture and structural timber engineering [1,2,3,4,5]. In contrast, wood-based materials are currently rarely used as construction materials in technical applications of mechanical engineering. Upon closer examination, however, a few promising approaches can be identified for the use of wood-based materials in load-bearing elements, such as in automotive engineering, materials handling technology, or even in aerospace [6,7,8,9,10]. Metals, with their isotropic and homogeneous structure combined with superior mechanical properties, have outpaced the anisotropic and inhomogeneous material wood as a construction material since the onset of industrialization [11]. By processing wood into engineered wood products, particularly in the form of veneer-based composites (WVCs—wood veneer composites), anisotropy and inhomogeneity can be largely minimized [12,13]. These materials exhibit favorable mechanical properties while maintaining a low density, which grants them significant lightweight potential. Provided sufficient structural space is available, they allow for the substitution of energy-intensive metallic or fiber-reinforced structures, as illustrated in Figure 1 [11].

Figure 1.

Ashby-graphics; (a) strength/density; (b) Young’s modulus/density.

The research group “Application of Renewable Materials” of the Chair of Materials Handling and Conveying Engineering at the University of Technology Chemnitz aims to exploit the existing lightweight potential of wood-based composite materials (WVCs), particularly plywood, and to develop sustainable applications in the field of mechanical engineering using modular timber construction [9]. In previous research projects, components such as workpiece carriers, load-handling devices, vertical conveyors, and frame elements have been developed [14]. In addition to compressive stresses, three-point bending has proven to be the predominant loading case, in which, depending on the ratio of span length to component height, a combined bending–shear stress condition occurs [15].

The development of timber components is consistently guided by the principle “as light as possible, as safe as necessary.” Consequently, component design constitutes an optimization task, in which the structural functionality over the entire service life must be ensured while minimizing material usage. Only under these conditions can true lightweight construction be achieved.

This objective can be realized through strength and deformation analyses; however, the specific material characteristics of wood must be considered, including anisotropy and the influence of moisture content and temperature (service climate) on mechanical properties [16]. In structural timber engineering, EN 1995 (EUROCODE 5) provides a design standard that regulates the calculation of load-bearing timber components based on a semi-probabilistic safety concept [17].

Nevertheless, the partial safety factors and the corresponding determination methods described in EN 1995 cannot be directly transferred to mechanical engineering applications. For example, EN 1995 classifies loads according to their duration of action (weeks, months, years), whereas in mechanical engineering, the decisive parameter is the number of load cycles. Despite these differences, EN 1995 provides valuable methodological approaches that can be adapted for the design of timber components in mechanical engineering. The analysis and adaptation of these methods form a central focus of current and future research activities.

Accordingly, the author’s primary research objective is the development of design methodologies, calculation frameworks, and safety concepts for timber components intended for mechanical engineering applications.

The foundation of this research was established through the joint project “Wood in Mechanical Engineering (HoMaba)—Design Concepts, Characteristic Value Requirements, and Characteristic Value Determination” conducted between 2018 and 2022 [18]. Within this project, fundamental design principles for static load cases were developed, which provide a basis for future research extensions addressing dynamic and long-term loading conditions.

The following research topics were investigated within the HoMaba project:

- Extensive material characterization of veneer, solid wood, and plywood made from birch and beech, followed by implementation of the obtained characteristic values in a comprehensive material database [19,20,21].

- Development of analytical and simulation-based models for predicting component mechanical properties based on fundamental material parameters [22,23,24,25].

- Establishment of basic safety assessment methodologies for timber components [18,23].

2. Statement of the Problem

Compared to conventional metallic construction materials such as steel and aluminum, wood and wood-based composites (WVCs) exhibit significantly lower absolute values of elastic and shear moduli, as illustrated in Table 1. In particular, the shear stiffness is markedly lower, as reflected by the ratio between the elastic and shear moduli. Shear loading in the radial–tangential plane (RT-plane), also referred to as rolling shear, is especially critical in plywood and must therefore be carefully considered in structural design [26,27,28,29,30].

Table 1.

Comparison of modulus values of steel, aluminum, solid birch wood, and birch plywood.

Current design codes in both mechanical engineering and structural timber engineering require separate verification of strength under bending and shear loads. Deformation verification, however, is not mandatory and is typically performed only to assess the long-term serviceability of a component. These verifications are generally based on Euler–Bernoulli beam theory, which considers bending without accounting for shear deformation effects [35].

This assumption is valid for metallic components, as metals possess very high shear stiffness. Likewise, it is justified in traditional timber engineering applications, where structural members typically exhibit large span-to-depth ratios, rendering shear deformation effects negligible. However, when substituting metallic structures with wood-based composites, the application of Euler–Bernoulli beam theory can lead to inaccurate results, since the global modulus of elasticity in three-point bending depends on the span-to-depth ratio. As this ratio decreases, the influence of shear deformation increases, resulting in a lower global modulus of elasticity.

Due to the comparatively low stiffness values of WVC materials, the area moment of inertia must be increased—i.e., the component depth must be enlarged—to limit deflections. However, this change in geometry alters the span-to-depth ratio, which in turn increases the influence of shear deformation on overall deflection and thus cannot be neglected. While stress verifications are generally uncritical due to the required increase in cross-sectional area, they must nonetheless be performed. More importantly, deformation verification should be carried out using Timoshenko beam theory when designing timber components for mechanical engineering applications.

By reformulating the Timoshenko beam theory, a computational approach can be derived for determining the global modulus of elasticity of a component for any given span-to-depth ratio. This requires knowledge of the material’s bending and shear moduli. Test procedures for determining these parameters are described in the relevant standards EN 310, EN 408, and EN 789 [36,37,38]. Each of these standards specifies distinct methods for evaluating bending and shear properties, designed to minimize interfering factors through defined testing conditions, thereby ensuring reliable results.

However, performing multiple types of tests to determine mechanical properties is both time- and cost-intensive—particularly for full-scale component tests, which are essential for characterizing the mechanical behavior of a component and validating analytical or numerical calculations. Consequently, there is a need for a practical testing methodology that enables the rapid and efficient determination of both bending and shear properties with minimal effort.

The present study introduces an evaluation methodology for three-point bending tests based on Timoshenko beam theory, which offers the following advantages:

- Simultaneous determination of bending and shear properties from three-point bending tests;

- Rapid and straightforward testing of materials and components;

- Provision of characteristic values for the structural design of timber components.

3. Materials and Methods

The material investigations were conducted on birch plywood bonded with phenol–formaldehyde resin. All individual test specimens were prepared from panel material originating from a single production batch of commercially available birch plywood manufactured in Eastern Europe. Consequently, the specimens may contain inherent wood-related or manufacturing-induced imperfections. Visual inspection of the cut edges revealed occasional overlaps, open joints, and knots. These features inherently contribute to higher standard deviations in the measured properties. Such specimens were intentionally not excluded from testing, as defective material may also occur under practical application conditions. Ideal characteristic values derived from flawless materials would therefore not be representative for design purposes. Table 1 summarizes the key material specifications. The density was determined in accordance with EN 323, and the moisture content was measured according to EN 322 on a randomly selected subset of specimens. The corresponding mean values are reported in Table 2 [39,40].

Table 2.

Material specifications of the tested birch plywood.

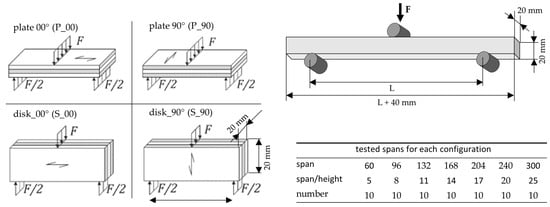

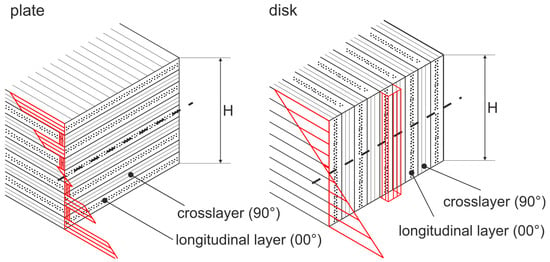

Conventional three-point bending tests were conducted in accordance with the principles of EN 310 [23]. All specimens featured a square cross-section. In total, seven different span-to-depth ratios ranging from 5 to 25 were examined. Although the anisotropy of the material is largely reduced by the cross-laminated structure of the plywood, variations in mechanical behavior still occur depending on the specimen orientation. Following the approach of EN 1995-1, the specimens were categorized according to two criteria: (i) the position of the mid-plane relative to the direction of loading—classified as plate or panel loading—and (ii) the fiber orientation of the face layers relative to the longitudinal axis of the specimen—defined as 0° or 90° orientation [17]. This classification results in four distinct test configurations:

- P-00°: Plate loading with the face-layer fibers oriented parallel to the specimen’s longitudinal axis;

- P-90°: Plate loading with the face-layer fibers oriented perpendicular to the longitudinal axis;

- S-00°: Panel loading with the face-layer fibers parallel to the longitudinal axis;

- S-90°: Panel loading with the face-layer fibers perpendicular to the longitudinal axis.

Figure 2 provides an overview of the entire experimental matrix. All tests were carried out using a Zwick/Roell Z250 universal testing machine (Zwick/Roell, Ulm, Germany) at a constant crosshead speed of 10 mm/min.

Figure 2.

Overview of the experimental setup; left: tested configurations according to EN 1995-1 [24]; top right: test setup; bottom right: tested span-to-height ratios.

The specimen deformations were not measured directly using an optical system but were instead obtained from the displacement of the testing machine’s crosshead. Consequently, the measured displacement includes not only the deformation of the specimen itself but also additional contributions—most notably the local indentation of the loading nose into the relatively soft surface of the plywood specimen. These extraneous deformations must be subtracted prior to determining the material parameters. For this purpose, specimens in each respective configuration were subjected to compression tests, and the corresponding force–displacement curves were recorded as correction curves. Prior to the evaluation of material properties, these deformation values were subtracted from the measured displacements of the bending tests at the corresponding force levels [23].

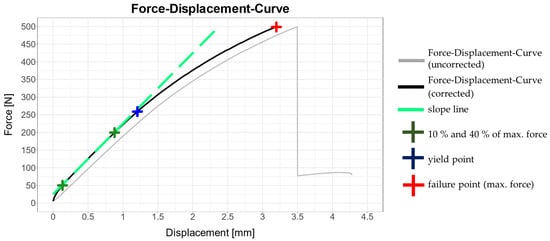

Figure 3 presents an example of a force–displacement curve obtained from a representative specimen. The grey curve represents the uncorrected measurement, which includes all deformation components originating from the testing setup and specimen contact. The black curve depicts the corrected force–displacement relationship after the removal of undesired deformation contributions. Based on the corrected force–displacement data, the stress parameters and the global modulus of elasticity were determined. First, the maximum test force corresponding to the failure point was identified. In Figure 3, this failure point is indicated by a red cross. Subsequently, the global modulus of elasticity was calculated in accordance with EN 789 by applying linear regression to all data points within the interval between 10% and 40% of the ultimate load (dark green crosses in Figure 3). The slope of this linear segment was then converted into the modulus of elasticity (green line in Figure 3) [38]. Finally, the proportional limit was determined, representing the transition from linear to nonlinear behavior. This point is defined as the first location along the curve where the local tangent modulus falls below 95% of the slope of the initial linear region. The stress corresponding to this point is defined as the maximum permissible stress and is marked in Figure 3 by a blue cross. Conversion of the measured forces into stress values was performed using the standard equations for calculating bending stress under three-point bending conditions (Equations (A5) and (A6) in the Appendix A).

Figure 3.

Exemplary force–displacement curve with the key parameters used for property determination.

The deformation data used for the determination of characteristic values represent the total deformation of the specimen resulting from the combined effects of bending and shear. The global modulus of elasticity derived from these measurements thus characterizes the specific elastic behavior of the specimen, taking into account its geometric parameters. It does not represent a material constant, but rather a value dependent on the span-to-depth ratio. In contrast, the bending modulus and the shear modulus are material constants that describe the resistance to deformation under pure bending and pure shear loading, respectively. Standardized testing procedures determine these constants by minimizing external influences. For instance, in three-point bending tests, a minimum span-to-depth ratio of 20 is prescribed in order to minimize shear effects to a level that may be neglected according to the relevant standards. The modulus of elasticity determined under these conditions is referred to as the bending modulus; however, strictly speaking, it corresponds to the global modulus of elasticity at the specified span-to-depth ratio.

According to Timoshenko beam theory, the total deformation in three-point bending is composed of a bending and a shear component [35]. These components can be considered independently of one another. The mathematical formulation of this relationship is given in Equation (A1) (Appendix A). Accordingly, the bending deformation depends on the bending modulus, while the shear deformation depends on the shear modulus (see Appendix A, Equations (A2) and (A3)). By substituting the differential equations for bending and shear under the load case of three-point bending with a central point load, a fundamental expression for the global modulus of elasticity can be derived as a function of the bending modulus, the shear modulus, the span length, and the cross-sectional parameters (area and moment of inertia), as shown in Equation (1). If the cross-sectional geometry is known, the equations for the cross-sectional area and moment of inertia can be inserted, simplifying the expression. Regardless of the cross-sectional shape, the specimen width cancels out, leaving only the span and specimen height as relevant geometric parameters. Consequently, Equation (1) reflects the dependency of the global modulus of elasticity on the span-to-depth ratio. When global moduli of elasticity are known for different span-to-depth ratios, the bending modulus and shear modulus of the material can be determined by applying nonlinear regression to the experimental data.

EGlobal = (κ ∙ EBiegung ∙ G ∙ A ∙ S2)/(κ ∙ G ∙ A ∙ S2 + 12 ∙ EBiegung ∙ Iyy)

EGlobal—global modulus of elasticity [MPa]; EBiegung—bending modulus [MPa];

G—shear modulus [MPa]; S—span length [mm]; A—cross-sectional area [mm2];

Iyy—moment of inertia [mm4];

κ—shear correction factor (for rectangular cross-sections κ = 5/6).

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Modulus Parameters

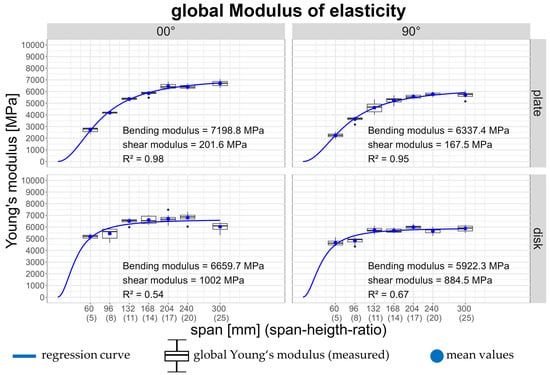

Figure 4 presents the box plots of the experimentally determined global moduli of elasticity for all tested span-to-depth ratios and configurations. The results indicate a clear trend: as the span-to-depth ratio increases, the global modulus of elasticity also increases. The curves asymptotically approach the value of the bending modulus, as the influence of shear deformation diminishes with increasing span-to-depth ratio. The bending and shear moduli determined through nonlinear regression of Equation (1) for the tested configurations are also displayed in the respective graphs. The blue curves in Figure 4 represent the calculated relationships of the global moduli of elasticity obtained using the regression-based bending and shear modulus values. Visually, the calculated and measured data show good agreement. The coefficients of determination (R2) confirm this observation: for the plate configurations, a very good correlation was achieved with R2 ≥ 0.95. In contrast, the panel configurations exhibit moderate agreement, with 0.54 ≤ R2 ≤ 0.67. This difference can be attributed to the less pronounced influence of shear deformation in panel loading compared to plate loading. At small span-to-depth ratios, the global moduli of elasticity are significantly higher under panel loading than under plate loading. The measured values in these configurations also show greater scatter around the regression curve, which explains the lower coefficients of determination. Nevertheless, when combined with visual inspection, the overall correspondence between the regression curves and the experimental data can still be regarded as satisfactory.

Figure 4.

Global moduli of elasticity and results of the nonlinear regression.

In the plate-00° configuration, the highest bending moduli were obtained, whereas the corresponding shear moduli were comparatively low. This behavior can be explained by the fact that shear loading acts in the radial–tangential (RT) plane of the cross layers, as illustrated in Figure 5. The cross layers possess very low rolling shear strength and therefore contribute minimally to the overall resistance against deformation. In the plate-90° configuration, both the bending and shear moduli exhibit lower values. The reason for this is that, in this configuration, there is one additional cross layer and one fewer load-bearing longitudinal layer compared to the plate-00° configuration. Under panel loading, the shear moduli are approximately five times higher than those determined under plate loading. This is because, in this case, the shear stresses act not in the RT-plane but in the tangential–longitudinal (TL) plane. In the TL-plane, the wood fibers themselves are subjected to shear, whereas in the RT-plane, the lignin matrix primarily carries the shear load, allowing the fibers to slip relative to one another. As a result of the higher shear moduli, the global moduli of elasticity for small span-to-depth ratios are greater under panel loading than under plate loading. Conversely, the bending moduli are lower for the panel configurations. Similar to the plate configurations, the 90° fiber orientation in the panel loading case exhibits lower modulus values than the 00° orientation, owing to the smaller number of load-bearing longitudinal layers.

Figure 5.

Stress scenarios in plate and disk loading [29].

A direct comparison of the experimentally determined modulus values with selected reference data for birch plywood from the literature is presented in Table 3. The literature values were obtained in accordance with standardized testing procedures, typically based on four-point bending tests. In these studies, differentiation is generally made only with respect to the orientation of the face-layer fibers relative to the longitudinal axis of the specimen. A distinction between plate and panel loading configurations is not reported in the reviewed sources. Overall, the bending moduli determined for the plate-00° configuration differ from those found in the literature. Possible explanations include variations in material density and moisture content among the tested plywood, as well as differences between the testing methods (three-point versus four-point bending). However, the most likely main reason for the observed discrepancies is the deformation correction procedure described in Section 3. For the plate-90° configuration, as well as for the shear moduli of both configurations, no significant deviations from the literature values were observed.

Table 3.

Comparison between measured module values and module values from literature sources.

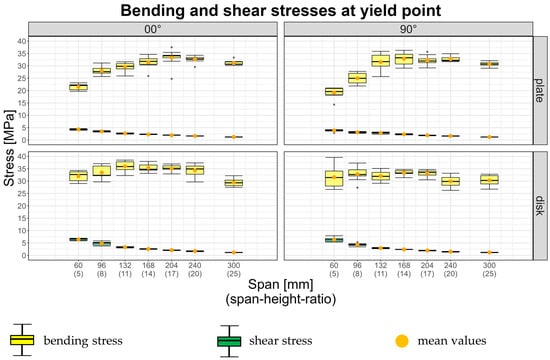

4.2. Stresses

Figure 6 presents the bending and shear stresses at the proportionality limit for all tested configurations. The stresses were calculated according to the equations provided in Equations (A5) (bending) and (A6) (shear). For plate loading, the determined bending stresses are initially low at small span-to-depth ratios and tend to increase with increasing ratios. Similar to the behavior observed for the modulus of elasticity, the stress levels approach an asymptotic limit, which can be defined as the bending strength for the respective configuration. The opposite trend is observed for the shear stresses: these are highest at the smallest tested span-to-depth ratio and decrease as the ratio increases. This behavior indicates that at small span-to-depth ratios, shear deformation has a greater influence on failure. This is evident from the fact that the achieved bending stresses are lower than those observed at larger spans, such as those typically prescribed in standardized test methods. Due to the abrupt failure behavior of the specimens, it cannot be clearly determined whether pure shear or pure bending failure occurred. However, the results suggest that shear failure in the cross layers predominates at small span-to-depth ratios, while at larger ratios, bending failure in the outer tension layers is more likely. For both panel configurations, the measured bending stresses remain approximately constant across all span-to-depth ratios. The shear stresses, similar to the plate configuration, are highest at the smallest ratio. No significant differences between the 00° and 90° configurations were observed for either plate or panel loading. The mean values and standard deviations of the key parameters for all configurations are summarized in Table A2 in Appendix A.

Figure 6.

Bending and shear stresses at the yield point.

Table 4 compares the determined strength parameters with corresponding values reported in the literature. The results show relatively good agreement with the values presented in [41], although the measured bending strength for configuration Plate-00° is slightly lower than that reported in the reference. In contrast, the bending and shear strength values from [27,42] are significantly higher than the experimentally determined values obtained in this study. This discrepancy likely results from differences in the material properties or in the methodologies used to determine the strength parameters.

Table 4.

Comparison between measured stress values and stress values from literature sources.

5. Conclusions

This study presented a method for determining the bending and shear properties of wood-based materials using data from three-point bending tests evaluated in accordance with the Timoshenko beam theory. Using commercial birch plywood as an example, the modulus and strength parameters were determined and analyzed for different specimen orientations. The results for the global modulus of elasticity demonstrate its dependence on the span-to-depth ratio: the smaller the ratio, the lower the global modulus of elasticity. By applying nonlinear regression, the bending and shear moduli of the material were identified for the different configurations. The analyses show that the global modulus of elasticity can be accurately predicted for any span-to-depth ratio using the bending and shear moduli determined through this method.

Furthermore, bending and shear stresses were evaluated for various configurations and span-to-depth ratios. The findings indicate that for plate-loaded specimens with small span-to-depth ratios, the bending strength is lower than for specimens tested at larger ratios, as typically specified in standardized test methods. Consequently, shear effects must also be considered in the design of components with small span-to-depth ratios.

The analyses conducted in this study establish an initial foundation for the analytical design of wood veneer composites (WVCs) for mechanical engineering applications. The presented investigations are limited to static loading under three-point bending up to failure. Future research should focus on dynamic and long-term loading scenarios to derive corresponding material parameters, ensuring the structural functionality of components over their intended service life. Additionally, further material testing and statistical analyses are required to provide a more detailed understanding of the influence of shear stresses on failure behavior.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.K. and S.E.; methodology, P.K. and S.E.; software, P.K.; validation, P.K. and S.E.; formal analysis, P.K.; investigation, P.K.; resources, P.K.; data curation, P.K.; writing—original draft preparation, P.K.; writing—review and editing, P.K. and S.E.; visualization, P.K.; supervision, S.E.; project administration, S.E.; funding acquisition, S.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research project “Wood-based materials in mechanical engineering (HoMaba)”, on which this publication is based, was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture (funding reference 22004418). The project was a joint project of the following research partners: TU of Munich, Fraunhofer Institute of Wood Research WKI, Dresden University of Technology, Institut für Holztechnologie Dresden (IHD), Institut für Fasern & Papier GmbH (PTS), University of Technology Chemnitz, Eberswalde University of Sustainable Development, University of Göttingen, and the Technical University of Applied Science Rosenheim.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all partners who worked on the project and to the German Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture for funding this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WVC | wood veneer composite | Iyy | moment of inertia [mm4] |

| wGlobal | total deformation [mm] | Wy | section modulus [mm3] |

| wbending | deformation part of bending [mm] | F | load [N] |

| wshear | deformation part of shear [mm] | b | cross-sectional width [mm] |

| EGlobal | global modulus of elasticity [MPa] | h | cross-sectional height [mm] |

| EBending | bending modulus [MPa] | MB | bending moment [Nmm] |

| G | shear modulus [MPa] | σbending | bending stresses [MPa] |

| S | span length [mm] | τ | shear stresses [MPa] |

| A | cross-sectional area [mm2] | ||

| κ | shear correction factor (for rectangular cross-sections κ = 5/6) | ||

Appendix A

Table A1.

Formulas for calculation in this paper.

Table A1.

Formulas for calculation in this paper.

| TIMOSHENKO Beam theory | |

| (A1) | |

| (A2) | |

| (A3) | |

| (A4) | |

| Stresses | |

| (A5) | |

| (A6) | |

Table A2.

Results of the material tests.

Table A2.

Results of the material tests.

| Orientation | Span [mm] | Span/Height | Young’ Modulus [MPa] | Bending Strength [MPa] | Shear Strength [MPa] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plate 00° | 60 | 5 | 2723 ± 201.4 | 21.5 ± 1.3 | 4.3 ± 0.26 |

| 96 | 8 | 4188 ± 62.4 | 28.08 ± 1.74 | 3.51 ± 0.22 | |

| 132 | 11 | 5363 ± 113.8 | 29.6 ± 1.76 | 2.7 ± 0.16 | |

| 168 | 14 | 5855 ± 144.9 | 31.48 ± 2.4 | 2.25 ± 0.17 | |

| 204 | 17 | 6457 ± 233.7 | 33.31 ± 3.34 | 1.97 ± 0.2 | |

| 240 | 20 | 6405 ± 178.9 | 32.69 ± 1.37 | 1.64 ± 0.07 | |

| 300 | 25 | 6691 ± 262.2 | 31.22 ± 1.1 | 1.25 ± 0.04 | |

| plate 90° | 60 | 5 | 2235 ± 185.0 | 19.22 ± 2.07 | 3.86 ± 0.42 |

| 96 | 8 | 3642 ± 199.4 | 25.01 ± 2.23 | 3.13 ± 0.28 | |

| 132 | 11 | 4623 ± 458.8 | 31.55 ± 3.46 | 2.86 ± 0.31 | |

| 168 | 14 | 5242 ± 295.9 | 32.84 ± 2.52 | 2.33 ± 0.18 | |

| 204 | 17 | 5562 ± 154.3 | 32.29 ± 1.84 | 1.9 ± 0.11 | |

| 240 | 20 | 5773 ± 163.7 | 32.77 ± 1.16 | 1.64 ± 0.06 | |

| 300 | 25 | 5703 ± 287.2 | 30.75 ± 0.94 | 1.23 ± 0.04 | |

| disk 00° | 60 | 5 | 5170 ± 196.6 | 31.98 ± 2.1 | 6.44 ± 0.42 |

| 96 | 8 | 5443 ± 451.0 | 38.27 ± 5.61 | 4.8 ± 0.71 | |

| 132 | 11 | 6509 ± 218.5 | 35.98 ± 2.05 | 3.29 ± 0.19 | |

| 168 | 14 | 6602 ± 348.6 | 35.4 ± 1.69 | 2.54 ± 0.12 | |

| 204 | 17 | 6702 ± 372.3 | 35.68 ± 2.31 | 2.11 ± 0.14 | |

| 240 | 20 | 6814 ± 345.1 | 34.33 ± 2.42 | 1.72 ± 0.12 | |

| 300 | 25 | 6026 ± 362.6 | 29.46 ± 1.59 | 1.18 ± 0.06 | |

| disk 90° | 60 | 5 | 4642 ± 236.3 | 31.59 ± 4.16 | 6.32 ± 0.83 |

| 96 | 8 | 4826 ± 271.1 | 33.72 ± 3.95 | 4.22 ± 0.5 | |

| 132 | 11 | 5732 ± 229.7 | 32.06 ± 2.03 | 2.91 ± 0.18 | |

| 168 | 14 | 5684 ± 179.5 | 33.39 ± 0.99 | 2.38 ± 0.07 | |

| 204 | 17 | 5991 ± 163.1 | 33.18 ± 1.36 | 1.95 ± 0.08 | |

| 240 | 20 | 5659 ± 256.7 | 29.94 ± 2.25 | 1.49 ± 0.11 | |

| 300 | 25 | 5872 ± 264.8 | 30.28 ± 2.14 | 1.21 ± 0.08 |

References

- Sikkema, R.; Dallemand, J.F.; Matos, C.T.; van der Velde, M.; San-Miguel-Ayanz, J. How can the ambitious goals for the EU’s future bioeconomy be supported by sustainable and efficient wood sourcing practices? J. For. Res. 2017, 32, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownell, H.; Iliev, B.E.; Bentsen, N.S. How much wood do we use and how do we use it? Estimating Danish wood flows, circularity, and cascading using national material flow accounts. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 423, 138720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The State of the World’s Forests 2024; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, R.J.; Richter, K. Part D General Aspects and Concepts in Wood Utilization. In Springer Handbook of Wood Science and Technology; Niemz, P., Teischinger, A., Sandberg, D., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1786–1974. [Google Scholar]

- Ramage, M.H.; Burridge, H.; Busse-Wicher, M.; Fereday, G.; Reynolds, T.; Shah, D.U.; Wu, G.; Yu, L.; Fleming, P.; Densley-Tingley, D.; et al. The wood from the trees: The use of timber in construction. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 68, 333–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair-Bauernfeind, C.; Zimek, M.; Asada, R.; Bauernfeind, D.; Baumgartner, R.J.; Stern, T. Prospective sustainability assessment: The case of wood in automotive applications. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2020, 25, 2027–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, R.; Tajmer, M.; Bach, C. Wood and Wood-Based Materials in Space Applications—A Literature Review of Use Cases, Challenges and Potential. Aerospace 2024, 11, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ligenium: Innovative Materialtransportlösungen für Maschinenbau, Produktion und Logistik. Available online: https://www.ligenium.de/ (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Holz im Maschinen- und Anlagenbau: Forschungsgruppe Anwendung Erneuerbarer Werkstoffe der TU Chemnitz. Available online: https://www.tu-chemnitz.de/mb/FoerdTech/aew/aew_start.php (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- NEQ: Holzbaukran. Available online: https://www.neq-cranes.at/krane/holzbaukran/ (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Ashby, M.F. Materials Selection in Mechanical Design, 3rd ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 3–4, 37–39. ISBN 0-7506-4357-9. [Google Scholar]

- Baensch, F. Damage Evolution in Wood and Layered Wood Composites Monitored In Situ by Acoustic Emission, Digital Image Correlation and Synchrotron Based Tomographic Microscopy; ETH-Zürich: Zürich, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Keylwerth, R. Die Anisotrope Elastizität des Holzes und der Lagenhölzer; VDI-Forschungsheft 430; Deutscher Ingenieur: Düsseldorf, Germany, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Forschungsgruppe Anwendung Erneuerbarer Werkstoffe—Projekte. Available online: https://www.tu-chemnitz.de/mb/FoerdTech/aew/aew_projekte.php (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Molotnikov, V.; Molotnikov, A. Theoretical and Applied Mechanics; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; ISBN 978-3-031-09312-8. [Google Scholar]

- Niemz, P.; Teischinger, A.; Sandberg, D. Springer Handbook of Wood Science and Technology; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 443–451. ISBN 978-3-030-81314-7. [Google Scholar]

- EN 1995-1-1:2023—10-Entwurf; Eurocode 5—Design of Timber Structures—Part 1-1: General Rules and Rules for Buildings. European Comitee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2023.

- Engelhardt, M.; Khaloian Sarnaghi, A.; Buchelt, B.; Krüger, R.; Schulz, T.; Gecks, J.; Kluge, P.; Krüger, R.; Penno, E.; Raskop, S.; et al. Holzbasierte Werkstoffe im Maschinenbau (HoMaba)—Berechnungskonzepte, Kennwertanforderungen, Kennwertermittlung (Wood-Based Materials in Mechanical Engineering—Calculation Concepts, Parameter Requirements, Parameter Determination); Technische Informationsbibliothek (TIB): Hanover, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Meynerts, P. Mechanische Eigenschaften von Holzwerkstoffen. Datenbank. Available online: https://www.tu-chemnitz.de/projekt/FT/Projektarchiv/Holzwerkstoffe/hwc.php (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Krüger, R.; Buchelt, B.; Wagenführ, A. Method for determination of beech veneer behavior under compressive load using the short-span compression test. Wood Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 1125–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchelt, B.; Wagenführ, A.; Dietzel, A.; Raßbach, H. Quantification of cracks and cross-section weakening in sliced veneers. Eur. J. Wood Prod. 2018, 76, 381–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluge, P.; Eichhorn, S. Calculation Concept for Wood-Based Components in Mechanical Engineering. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2023, 25, 2300085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluge, P. Dimensionierungs- und Bemessungsgrundlagen für Statisch Beanspruchte Bauteile aus Holzfurnierlagenverbundwerkstoffen zur Anwendung im Maschinenbau. Ph.D. Thesis, TU Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Krüger, R.; Buchelt, B.; Zauer, M.; Wagenführ, A. Veneer Composites for Structural Applications—Mechanical Parameters as Basis for Design. Forests 2025, 16, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, R. Investigations on Rotary-Cut Veneer of Beech Wood for the Application of Veneer-Based Materials in Mechanical Engineering. Ph.D. Thesis, TU Dresden, Dresden, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M. Evaluating rolling shear strength properties of cross-laminated timber by short-span bending tests and modified planar shear tests. J. Wood Sci. 2017, 63, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, Y.; Crocetti, R.; Wålinder, M. In-plane mechanical properties of birch plywood. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 340, 127852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Huang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Gong, M. Rolling shear failure of CLT transverse layer: AE characterization of damage mechanisms under different test methods. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 440, 137479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xie, Q.; Han, Y.; Sui, Y.; Wu, Y.; Xue, J.; Wang, Y. Experimental study on the mechanical properties of wood subjected to combined perpendicular-to-grain normal and rolling shear loads. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 449, 138320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, T.K.; Ormarsson, S. Chapter 10 Modeling the mechanical Behavior of Wood Materials and Timber Structures. In Wood Science and Technology; Niemz, P., Teischinger, A., Sandberg, D., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; p. 536. [Google Scholar]

- EN 1993-1-1:2010-12; Eurocode 3: Design of Steel Structures—Part 1-1: General Rules and Rules for Buildings. European Comitee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2010.

- EN 1999-1-1:2014-03; Design of Aluminium Structures—Part 1-1: General Structural Rules. European Comitee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2014.

- EN 338:2016-07; Structural Timber—Strength Classes. European Comitee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2016.

- EN 12369-2:2025-11; Wood-Based Panels—Characteristic Values for Structural Design—Part 2: Plywood. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2025.

- Spura, C. Technische Mechanik 2—Elastostatik: Nach Fest Kommt ab; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019; pp. 223–266. [Google Scholar]

- EN 310:1993; Wood-Based Panels—Determination of Modulus of Elasticity in Bending and of Bending Strength. European Comitee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 1993.

- EN 408:2012; Timber Structures—Structural Timber and Glued Laminated Timber—Determination of Some Physical and Mechanical Properties (Includes Amendment A1:2012). European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2012.

- EN 789:2005; Timber Structures—Test Methods—Determination of Mechanical Properties of Wood Based Panels. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2005.

- EN 323:1993; Wood-Based Panels—Determination of Density. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2023.

- EN 322:1993; Wood-Based Panels—Determination of Moisture Content. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2023.

- Finish Forest Industries Federation; UPM. Handbook of Finnish Plywood; Kirjapaino Markprint Oy: Lathi, Finland, 2007; ISBN 952-9506-66-X. [Google Scholar]

- Zalcmanis, A.; Zudrags, K.; Japins, G. Birch Plywood Sample Tension and Bending Property Investigation and Validation in Solid Works Environment. In Proceedings of the Research for Rural Development. 2018. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330640903_Birch_plywood_sample_tension_and_bending_property_investigation_and_validation_in_solid_works_environment (accessed on 21 October 2025). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).