Abstract

Bamboo is an important agroforestry and forest plant managed and utilized by rural communities in some countries in the Asia Pacific region, which can generate various benefits to meet social and environmental needs. In rural areas of China, as a large number of forest land management rights have been allocated to small-scale farmers, the willingness of small-scale farmers to reinvest in bamboo forest management has become a key factor for bamboo forest ecosystems to be able to sustainably supply quality ecosystem services. Therefore, it is necessary to answer the question of how to enhance small-scale farmers’ willingness to reinvest in bamboo forest management in the current policy and market context. Combining the prospect theory, the mindsponge theory, the theory of planned behavior (TPB), and the technology acceptance model (TAM), this study constructs theoretical models of perceived property rights security, perceived bamboo forest certification, government support, group decision making, risk perception, perceived value, geographic conditions, and resource endowment affecting willingness to reinvest in bamboo forest management. Based on 1090 questionnaires from a field study in Fujian, China, in 2021, structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to test the theoretical model. The results show that, under the current policy and market environment, government support is the key to enhance small-scale farmers’ willingness to reinvest in bamboo forest management, and their perception of ecological certification also has a facilitating effect on small-scale farmers’ willingness to reinvest in bamboo forest management, in which risk perception plays a significant mediating role. The government can enhance small-scale farmers’ willingness to reinvest in bamboo forest management by maintaining stable land property rights policies, increasing the publicity and promotion of bamboo forest certification, and enhancing information exchange among farmers.

1. Introduction

Bamboo is an important agroforestry and forest plant managed and utilized by rural communities in some countries in the Asia Pacific region, which can generate various benefits to meet social and environmental needs [1]. China is one of the countries with the widest distribution, largest area, and earliest utilization of bamboo in the world. According to the results of the 9th National Forest Resources Inventory, China currently has a bamboo forest area of 6.41 million hectares [2], ranking first in the world. Various studies have indicated [3,4] that bamboo plantations provide ecosystem services similar to other forests or grasslands, including the supply of bamboo products, soil conservation, carbon sequestration, air purification, oxygen release, and cultural tourism. Bamboo has a wide range of uses, and bamboo products have expanded from traditional primary processed products such as bamboo tools and bamboo shoots to fine-processed products such as bamboo charcoal, soft-packaged bamboo food, and bamboo building materials: from “original bamboo utilization” to fully processed “full bamboo utilization”. In addition, due to the fast growth rate of bamboo, it has a superior carbon sequestration capacity compared to other tree species. It has been shown that the mean aboveground carbon sequestration of a 29-year-old Taiwan red cypress (Chamaecyparis formosensis) and a 33-year-old Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria japonica) was 2.83 and 4.44 Mg ha−1yr−1, respectively, which was much lower than 8.13 Mg ha−1yr−1 for Moso bamboo and 9.89 Mg ha−1yr−1 for a Makino bamboo forest [1,5]. Bamboo forests are fast-growing, short-cycling, and high-yielding, and under scientific and rational management, a single afforestation can be harvested for many years with a long economic life, which makes them a “renewable” resource [6,7]. Therefore, bamboo forests are also known as the “second largest forest in the world” and are the best material to replace wood in many fields.

The reinvestment willingness of small-scale farmers reflects their motivation for the sustainable management of bamboo forests, which in rural China is a key factor that enables the bamboo forest ecosystem to provide sustained high-quality ecosystem services. However, through field investigation, we found that most of the small-scale farmers are not fully aware of the role of bamboo and the development potential of the bamboo industry. Due to the continuous decline in market price of bamboo timber and bamboo shoots in recent years, as well as the significant migration of the rural labor force leading to the rising employment costs, the profit margins for farmers have been reduced. This has directly resulted in a decrease in the motivation for bamboo forest management among small-scale farmers. As an integral component of sustainable forest management, exploring the influencing mechanism of small-scale farmers’ reinvestment willingness in bamboo forest management has significant practical implications in alleviating the supply–demand imbalance of global timber and climate change.

According to the existing literature, the factors influencing small-scale farmers’ willingness to manage forests can be roughly divided into three categories. The first category is policy and market factors, with policy mainly focusing on the impact of the collective forest tenure system and logging quotas on small-scale farmers’ forest management willingness. Among these, the former is considered to have a positive impact on small-scale farmers’ forest management [8,9], while the latter may reduce their investment in forest management [10]. In recent years, scholars have gradually begun to pay attention to the impacts of eco-certifications on forest management in the market. However, these impacts may be positive [11], or insignificant [12], depending on factors such as certification standards, market demand, and certification costs. The second category is the objective factors related to small-scale farmers’ personal and family characteristics, such as higher income from forest management, more available household labor, larger forest land area, easier access to loans, and more convenient transportation in the villages, which would make small-scale farmers more willing to invest in forest management [9,13,14]. In contrast, when small-scale farmers are older, have higher education levels, and have higher non-agricultural incomes, their willingness to invest in forest management would decrease [8,15]. The third category includes the subjective factors related to small-scale farmers’ perceptions of risk and their preferences for the time horizon of profit generation, which can affect their willingness to invest in forest management [16,17]. It is widely recognized in the scientific community that most small-scale farmers are risk-averse and prefer to obtain immediate returns rather than future ones, which makes them more inclined to choose tree species with short management cycles [18].

Overall, existing research has focused more on the impact of individual factors on forest management, but lacks studies that reveal the interactions between these factors, and has not yet established a systematic mechanism for the sustainable management of forests. To fill these academic gaps, we conducted a face-to-face survey in Fujian Province, China, to collect data on the willingness of small-scale farmers to manage bamboo forests. The potential contributions of this article are mainly reflected in two aspects. Firstly, on the basis of previous research, we constructed a theoretical model that integrates the theory of planned behavior and the technology acceptance model, which explains how the perceived property rights security, perceived bamboo forest certification, government support, group decision making, risk perception, perceived value, geographic conditions, and resource endowment affect the small-scale farmers’ willingness to reinvest in bamboo forest management. We then conducted an empirical analysis using survey data to achieve a systematic study from theory to practical application. Secondly, we explored the interactive mechanism between external factors such as policies and markets and the subjective influencing factors of small-scale farmers, and examined the mediating effect of risk perception in the paths through which perceived property rights security, perceived bamboo forest certification, government support, and group decision making affect the small-scale farmers’ willingness to reinvest in bamboo forest management. Our findings revealed how external factors influence the willingness of small-scale farmers to sustainably manage bamboo forests.

2. Conceptual and Theoretical Framework

The theory of planned behavior and the technology acceptance model are commonly used in the field of farmer decision making. However, these theories have limitations that require scholars to expand on them according to the characteristics of their own research in order to enhance their ability to explain practical problems. The prospect theory suggests that the transmission of information is influenced by various factors. Therefore, decision makers often cannot make decisions under conditions of complete information. Additionally, decision makers’ behavioral habits and cognitive abilities, as well as their personal preferences, can influence their decision-making process. As a result, decision making under uncertainty exhibits characteristics of bounded rationality [19]. The mindsponge theory posits that individuals, upon receiving external information, judge whether this information falls within their comfort zone based on their own values and core beliefs. They then filter and process the information to make decisions that are more aligned with their own values [20]. In this model, we integrate and improve upon existing theories by conceptualizing risk perception as a psychological factor that represents the compatibility judgment between external information and an individual’s cognitive comfort zone. Under the assumption that small-scale farmers maintain their managements, information that does not align with their comfort zone increases their risk perception, for example, frequent changes in property rights, reduced government support, the cessation of bamboo forest management by people around them, or the cancellation of bamboo forest certifications. Excessive risk perception may lead small-scale farmers to make decisions contrary to the premise of continuing managements.

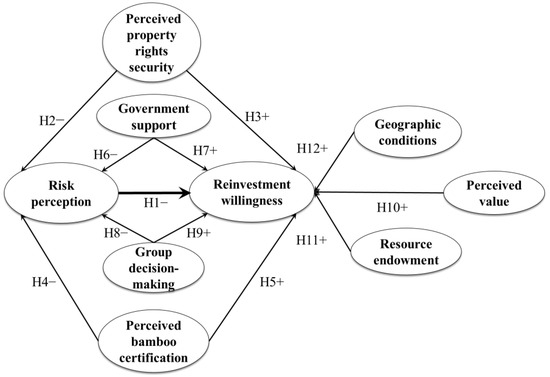

Based on references to the prospect theory, the mindsponge theory, the theory of planned behavior, and the technology acceptance model, this study constructed a theoretical model for the sustainable management of bamboo forests by small-scale farmers under the influence of external policies and market environments. This model combines small-scale farmers’ subjective perceptions and objective environmental factors, and includes nine latent variables: perceived property rights security, perceived bamboo forest certification, group decision making, government support, geographic conditions, perceived value, resource endowment, risk perception, and farmers’ intentions for the sustainable management of bamboo forests. The specific model construction is shown in Figure 1. Perceived property rights security and government support reflect the impact of policies on bamboo forest management. Perceived bamboo forest certification reflects the influence of international market demand on bamboo forest management in China. Group decision making reflects the influence of values held by relatives and friends in the immediate social circle of small-scale farmers. Geographical conditions and resource endowments are perceived behavioral control variables derived from the theory of planned behavior [21], reflecting the impact of objective constraints on the decision making of small-scale farmers. Perceived value is derived from the perceived usefulness variable of the technology acceptance model [22], which reflects the influence of the behavioral outcomes in the subjective cognition of small-scale farmers on their willingness. The impact logic of the remaining variables on the willingness of small-scale farmers to reinvest in bamboo forest management will be elaborated on in the following sections.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model of reinvestment in bamboo forest management by small-scale farmers.

2.1. Risk Perception (RP) and Reinvestment Willingness (RW)

Risk perception refers to the psychological state in which individuals perceive external risks and reflect their intuitive judgment, subjective feelings, and responses to the external environment. Numerous studies have previously demonstrated that risk perception is an important factor that influences individual decision-making behavior [23,24,25], and according to the planned behavior theory and the technology acceptance theory, behavioral intention is a key determinant of behavior occurrence, whereby risk perception equally influences the subject’s behavioral intention [26,27,28]. Small-scale farmers are subject to various influences from external policy, market, and natural environments while managing their bamboo forests. Frequent policy changes, market price fluctuations, and natural disasters result in uncertainty for small-scale farmers, and are the primary sources of risk perception in their management of bamboo forests. In this study, the willingness to reinvest reflects the initiative of small-scale farmers in managing their bamboo forests, including inputs such as land, capital, and labor. When perceiving higher levels of risk, small-scale farmers may reduce their willingness to sustainably manage their bamboo forests in order to avoid risks. Based on this, the following research hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

The higher the perceived risks among small-scale farmers, the lower their willingness to reinvest in the enterprise.

2.2. Perceived Property Rights Security (PPRS)

In this study, land property rights refer specifically to the forest land property rights held by small-scale farmers. The perceived forest land property rights of small-scale farmers consist of two main components: their subjective evaluation of the property rights environment they are situated in and their apprehension of potential losses of forest property in the future [29]. Land property rights security comprises three levels: perceptual security, actual security, and legal security. Actual and legal property rights security ultimately affect small-scale farmers’ land utilization behavior by impacting their perceived land property rights security. The perceived security level of land property rights is a fundamental prerequisite for small-scale farmers’ actual land utilization behavior. If they perceive a risk to their land property rights, they may reduce or cease their development and utilization of the land. Conversely, if they perceive that their land property rights are adequately protected, they will be more actively engaged in developing and utilizing the land. Therefore, influencing small-scale farmers’ perceived land property rights security level is essential for ultimately affecting their land utilization behavior [29,30,31]. In essence, the higher the perceived sense of security in land ownership among small-scale farmers, implying their belief that their own forestland will remain under their possession in the future, the more assurance they have regarding their investments in the forestland. Consequently, their perception of risks associated with bamboo management decreases, leading to an increased willingness to reinvest. Therefore, risk perception can be considered as a mediating variable in the pathway where “perceived property rights security” influences “reinvestment willingness”. Based on this, the following research hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

The perceived property rights security among small-scale farmers has a negative influence on their risk perception in bamboo forest management.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

The perceived property rights security among small-scale farmers has a positive impact on their willingness to reinvest in bamboo forest management.

2.3. Perceived Bamboo Forest Certification (PBFC)

Bamboo forest certification (BFC) is a type of ecological certification that promotes sustainable bamboo forest management through market mechanisms. The implementation of BFC is mainly achieved through the process of the supervision of bamboo planting and harvesting and product traceability systems. This approach helps consumers gain a better understanding of production process, and ensures the quality of certified products, and hence increases their preference for BFC products and ultimately contributes to the income of small-scale farmers. Perceived bamboo forest certification refers to the subjective evaluation of BFC by small-scale farmers, including their perceptions of the potential benefits that BFC could bring to bamboo forest management both currently and in the future. This includes a subjective evaluation of the practical benefits of BFC such as eco-premium for bamboo product sales, stable market demand, and improved quality, as well as an evaluation of the future development of the bamboo industry. The enhancement of small-scale farmers’ perceptions of BFC will correspondingly reduce their perception of risk in bamboo forest management, whether it stems from practical benefits or positive expectations for the future development of the bamboo industry. This, in turn, will promote their willingness to reinvest in bamboo forests management. Therefore, risk perception can be considered as a mediating variable in the pathway where “perceived bamboo forest certification” influences “reinvestment willingness”. Based on this, the following research hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Small-scale farmers’ perception of bamboo forest certification will have a negative impact on their perception of risk in bamboo forest management.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Small-scale farmers’ perception of bamboo forest certification will have a positive impact on their willingness to reinvest in bamboo forest management.

2.4. Government Support (GS)

Government support refers to the assistance and help provided by the government to bamboo forest management households, including subsidies, loan assistance, relevant technical training, and market information, among others. These supportive behaviors can effectively mitigate the level of information asymmetry among small-scale farmers, government, and market. Government support plays a promotional role in small-scale farmers’ production decision-making behavior [32,33], and also effectively reduces their perception of risk in bamboo forest management, thereby enhancing their confidence in bamboo forest management and making them more willing to reinvest in it. Lu et al. [34] found that the policies of forest land contracting, forestry financial subsidies, and forestry insurance have varying degrees of impact on farmers’ forestry investment and income. Among them, forestry insurance primarily enhances farmers’ investment in forest land by reducing their perceived risks. Therefore, risk perception can be considered as a mediating variable in the pathway where “government support” influences “reinvestment willingness”. Based on this, the following research hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Government support has a negative impact on small-scale farmers’ perception of risk in bamboo forest management.

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Government support has a positive impact on small-scale farmers’ willingness to reinvest in bamboo forest management.

2.5. Group Decision Making (GD)

Within the theoretical framework of behavioral economics, individual behavior is typically influenced by various psychological factors. In reality, small-scale farmers do not exist as entirely independent individuals; rather, they live within densely connected networks of relationships. The information generated by frequent communication and interaction within these networks can often impact the decision making of the individual [35,36], which is an effect known as herding behavior. The theory of planned behavior refers to the subjective influence that people surrounding an individual have on their adoption of a certain behavior as subjective norms, which has a direct positive impact on the individual’s behavioral intentions [21]. In this study, group decision making was used to represent the subjective positive influence that the surrounding villagers, relatives, and friends have on the small-scale farmer’s willingness to reinvest in bamboo forest management. Group decision making may have two effects on small-scale farmers’ reinvestment in bamboo forest management. On the one hand, when people around them engage in reinvestment in bamboo forest management, small-scale farmers may also engage in such reinvestment due to the phenomenon of herd behavior. On the other hand, through information exchange with people around them, small-scale farmers acquire more information about bamboo forest management, including but not limited to market information and management techniques. Such exchange weakens their perceived risks associated with bamboo forest management and hence increases their willingness to reinvest in it. Therefore, risk perception can be considered as a mediating variable in the pathway where “group decision-making” influences “reinvestment willingness”. Based on this, the following research hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 8 (H8).

Group decision making has a negative impact on small-scale farmers’ perceived risk of bamboo forest management.

Hypothesis 9 (H9).

Group decision making has a positive impact on small-scale farmers’ willingness to reinvest in bamboo forest management.

2.6. Perceived Value (PV)

The theory of perceived value was originally developed to study consumers’ attitudes and behaviors. According to this theory, consumers’ attitudes and behaviors are led by their perceptions of the value of consumption activities [22]. In this study, perceived value refers to the subjective evaluation of the benefits that small-scale farmers perceive they might obtain from bamboo plantation management. The core dependent variable of this study is the small-scale farmers’ willingness to reinvest in bamboo forest management, which differs from their initial participation willingness in that the former is built upon a certain level of familiarity with bamboo forest management. Therefore, in the model that examines the factors influencing small-scale farmers’ willingness to continue investing in bamboo forest management, it is important to include their perceived value of bamboo forest management. This value is based on the experience gained from their previous investment in bamboo forest management, and can help small-scale farmers form positive or negative evaluations of the management practices. Based on these evaluations, they can decide whether to increase or decrease their reinvestment in bamboo forest management. Thus, the higher the perceived value small-scale farmers attribute to bamboo forest management, the more willing they are to engage in bamboo forest regeneration, indicating a direct causal relationship between the two factors. Based on this, the following research hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 10 (H10).

Perceived value has a positive impact on small-scale farmers’ willingness to reinvest in bamboo forest management.

2.7. Geographic Conditions (GC) and Resource Endowment (RE)

The perceived behavioral control variable in the theory of planned behavior and the perceived ease of use variable in the technology acceptance model have similar meanings, both referring to the subjective judgment of the behavioral subject on the difficulty or ease of performing the behavior. In this study, the variable is disaggregated into two more refined and objective variables. Geographic conditions are used to reflect the influence of external environmental factors on the willingness of bamboo forest management reinvestment, such as local environmental conditions including roads, climate, topography, and precipitation. Resource endowment is used to reflect the impact of small-scale farmers’ own conditions on their willingness to reinvest in bamboo forest management, including personal characteristics such as their own forestland resources, labor resources, and operating capital. These two variables are objective factors that small-scale farmers take into consideration when making production decisions. Based on this, the following research hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 11 (H11).

Resource endowment has a positive effect on small-scale farmers’ willingness to reinvest in bamboo forest management.

Hypothesis 12 (H12).

Geographic conditions have a positive effect on small-scale farmers’ willingness to reinvest in bamboo forest management.

3. Methods

3.1. Questionnaire Design

The questionnaire consists of three parts. The first part involves the introduction of the questionnaire where, in the actual research process, we would provide an explanation of the purpose of the questionnaire to the respondents and obtain their consent. The second part encompasses the demographic information of the respondents, such as gender, age, educational level, and occupation. The final part constitutes the core of the questionnaire, which is designed for the empirical testing of the theoretical model. In this section, a set of questions was designed based on the needs, covering nine themes including perceived property rights security, perceived bamboo forest certification, government support, group decision making, risk perception, perceived value, geographic conditions, resource endowment, and willingness for reinvestment in bamboo forest management. Responses were provided on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). During the preliminary survey, a total of 50 relevant items were designed for this study. Exploratory factor analysis was conducted on the initial scale to test its reliability and validity. After removing unsuitable items, the observed variables in the formal survey’s scale were ensured to have factor loadings greater than 0.5 on their corresponding latent variable’s principal components [37], ensuring the reliability and validity of the questionnaire. The specific scale used in the final survey can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Questionnaire items.

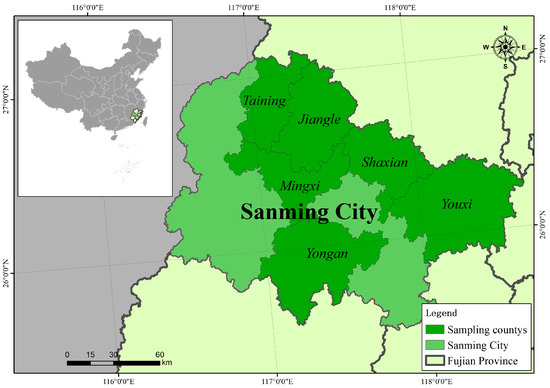

3.2. Data Source

We conducted a field questionnaire survey in Sanming City, Fujian Province (the province with the largest bamboo forest area in China), from June to July 2021 (Figure 2). A total of 1200 questionnaires were distributed to small-scale farmers engaged in bamboo forest management using a combination of stratified sampling and convenience sampling methods. In terms of spatial distribution, the number of small-scale farmers to be sampled in each county was determined based on the proportion of the bamboo forest management population in that county. Similarly, the number of samples to be taken from each village was determined following the same criteria. All members of the research team received appropriate training to effectively respond to inquiries raised by respondents, ensuring the quality of data. After excluding incomplete responses and invalid questionnaires with consistent ratings across all options, we retained a total of 1090 questionnaires, resulting in an effective response rate of 90.83%. Following the recommendation by Kline [38], we adhered to the guideline of having a sample size of at least 10 times the number of observed variables. Considering that our study involves 30 observed variables, a minimum of 300 samples were required. Therefore, sample size of 1090 is more than sufficient for conducting this research.

Figure 2.

Study area.

3.3. Research Method

Structural equation modeling (SEM) is a method used to establish, estimate, and examine causal relationships between variables. It overcomes the limitations of traditional statistical methods in handling unmeasured independent variables. The purpose of SEM is to measure the relationships and their strengths between multiple measured variables and latent variables. It is commonly used in academia to test theoretical models related to mechanisms [38]. The structural equation modeling comprises two components: the structural model, which is used to describe the causal relationships between latent independent variables and latent dependent variables, and the measurement model, which is used to describe the linear relationships between latent variables and observed variables.

The measurement equation can be represented as follows:

where x are the column vectors of the exogenous variables; are the factor loading matrices that associate the latent exogenous variables and observed variables; y are the column vectors of the endogenous variables; and are the factor-loading matrices that correlate the latent endogenous variables and observed variables. ξ and represent the latent exogenous and latent endogenous variables, respectively. and are error terms.

The structural equation can be represented as follows:

where B represents the relationship between endogenous latent variables η1 and η2. denotes the influence of exogenous latent variables on endogenous latent variable . is the error term, which reflects the unexplained portion of endogenous latent variable in the equation. This could be due to measurement errors or other unknown factors.

SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and AMOS 24.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) were used to analyze the questionnaire data for reliability and validity. More details are given in Section 4. The normality test of the sample indicates that the skewness and kurtosis coefficients of each variable are close to 0 (p < 0.05), suggesting that the multivariate data of the sample conform to a normal distribution. Therefore, it is feasible to use maximum likelihood estimation in the model estimation.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Characteristics

The demographic characteristics of the data collected this study are presented in Table 2. They mainly have the following characteristics: (1) Small-scale farmers are predominantly male. (2) The majority of small-scale farmers are aged 50 and above. (3) Over half of small-scale farmers have an educational background below primary school level. (4) The number of married individuals is relatively high among small-scale farmers. (5) Over half of small-scale farmers primarily engage in farming activities. (6) The majority of small-scale farmers have a family labor force ranging from 3 to 5 individuals. (7) Most small-scale farmers consider themselves in good physical health. Overall, the respondents in this survey align with the general characteristics of rural China, indicating a strong representativeness of the sample and its usability for future research.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of the respondents.

4.2. Reliability and Validity Testing

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to assess the reliability and validity of the scale. Composite reliability (CR) and Cronbach’s α were used as indicators of reliability [39]. Table 3 shows that the Cronbach’s α for all latent variables ranged from 0.840 to 0.973, exceeding the standard of 0.70 [40]. Moreover, removing any item from the scale did not significantly increase the overall Cronbach’s α, indicating internal consistency and reliability among all latent variables in the questionnaire. Complementing the reliability test, the construct reliability (CR) values for all latent variables ranged from 0.857 to 0.983, surpassing the standard of 0.70 [41], indicating a high level of internal consistency among the latent variables and overall good scale reliability.

Table 3.

Reliability and validity test results.

Convergent and discriminant validity were assessed for each latent variable in the scale. Convergent validity was evaluated using factor loadings and average variance extraction (AVE). As shown in Table 3, the standardized factor loadings of all items exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.50 [37] and are statistically significant (p < 0.001). The AVE values ranged from 0.606 to 0.949, which were higher than the suggested threshold of 0.50 [41], indicating good convergent validity of the scale, with each observed variable having a high explanatory power for its corresponding latent variable. Regarding discriminant validity, the square root of AVE exceeded the correlations between latent variables (Table 4), while the low correlations between latent variables (r < 0.85) [42] are indicative of great discriminant validity between different latent variables. In conclusion, these values indicate that the final scale used in this study has high validity and reliability.

Table 4.

Correlations between the latent variables.

4.3. Common Method Bias Testing

Common method bias (CMB) is commonly used in psychology, and refers to the artificial covariation between independent and dependent variables caused by the same data source, respondents, measurement environment, the contextual setting of items, and the characteristics of the items themselves [43]. CMB is considered a systematic error that can lead to significant biases in research results. If CMB exists in the research data, spurious relationships between latent variables may be observed. The Harman’s single-factor test was conducted on the model using SPSS 26.0. The variance contribution of the first common factor extracted without rotation was found to be 24.76%, which is below the recommended threshold of 50% [44]. This suggests that the level is within an acceptable range.

4.4. Hypothesis Testing and Fitting RESULTS

Indices such as χ2/df, RMSEA, SRMR, PGFI, PGFI, TLI, CFI, and IFI were selected to test the goodness of fit. The results are as follows: 1 < χ2/df = 2.733 < 3 (suggested threshold), RMSEA = 0.065 < 0.08, SRMR = 0.025 <0.08, PGFI = 0.679 > 0.5, PGFI = 0.679 > 0.5, TLI = 0.96 > 0.9, CFI = 0.968 > 0.9, and IFI = 0.967 > 0.9 [45]. These indices are all within the recommended values, indicating that the model fits the data well.

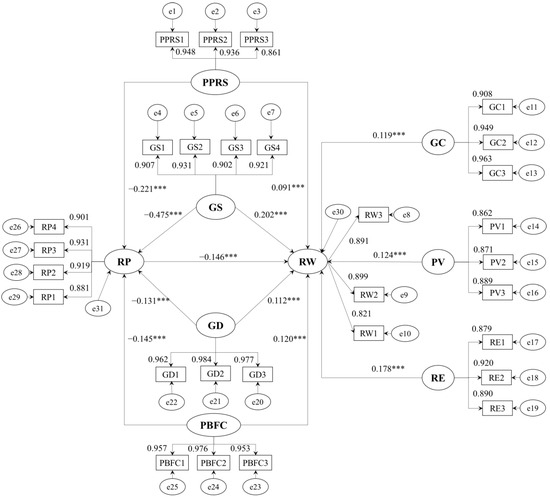

The results of the path coefficient test for the structural model of this study are presented in Table 5 and Figure 3. In the model of this study, all hypotheses have been validated. Specifically, when considering only direct effects, government support has the highest positive promoting effect on increasing small-scale farmers’ willingness to reinvest in bamboo forest management (β = 0.202, t = 4.124; p < 0.001). Following that, resource endowment has a positive promoting effect on small-scale farmers’ willingness to reinvest in bamboo forest management (β = 0.178, t = 3.221; p < 0.001). Perceived value, the perception of bamboo forest certification, and geographical conditions have similar positive promoting effects on small-scale farmers’ willingness to reinvest, with standardized coefficients around 0.120. The impact of perceived property rights security and group decision making on small-scale farmers’ willingness to reinvest in bamboo forest management is relatively small.

Table 5.

Hypotheses test results.

Figure 3.

Fitting results of structural equation model (significance level *** p ≤ 0.001).

Among the four independent variables that potentially have mediating effects, government support has the greatest weakening effect on risk perception (β = −0.475, t = −7.522; p < 0.001), followed by perceived property rights security, perceived bamboo forest certification, and group decision making. In general, government support has the greatest impact in this model, with a strong positive direct effect on small-scale farmers’ willingness to reinvest in bamboo forest management. Moreover, it effectively reduces small-scale farmers’ risk perception to a significant extent, thereby weakening the negative impact on their reinvestment intentions. Therefore, enhancing government support can be an effective strategy to promote small-scale farmers’ willingness to reinvest in bamboo forest management.

4.5. Mediation Effects Testing

Bootstrap was used to test the mediation effect of the theoretical model; the confidence interval was set to 95%, and the sample size was 5000. The experimental results indicate that, in the mediation model, perceived property rights security has a significant indirect impact on small-scale farmers’ willingness to reinvest in bamboo forest management. The 95% confidence interval of the indirect effect of standardization is (0.011, 0.098), and the 95% confidence interval of the direct effect of standardization is (0.035, 0.215). These findings suggest the presence of partial mediating effects in the “perceived property rights security—risk perception—reinvestment willingness” pathway. Perceived bamboo forest certification has a significant indirect impact on reinvestment willingness. The 95% confidence interval for the standardized indirect effect is (0.003, 0.073), and the 95% confidence interval for the standardized direct effect is (0.143, 0.316). This indicates that the “perceived bamboo forest certification—risk perception—reinvestment willingness” pathway has partial mediating effects in the model. Group decision making has an indirect impact on small-scale farmers’ willingness to reinvest in bamboo forest management. The 95% confidence interval for the standardized indirect effect is (0.005, 0.059), and the 95% confidence interval for the standardized direct effect is (0.117, 0.254). This indicates that the “group decision-making—risk perception— reinvestment willingness “pathway has partial mediating effects in the model.

5. Discussion

This study developed a theoretical model for small-scale farmers’ reinvestment in bamboo forest management. All hypotheses were empirically validated. Despite the considerable differences in conditions (e.g., Vietnam, Africa, Ireland), other researchers have found similar results. Perceived property rights security [46], group decision making [47], and government support [48] showed significant positive relationships with reinvestment willingness. Conversely, risk perception exhibited a significant negative relationship with reinvestment willingness [49]. Perceived property rights security, group decision making, and government support effectively mitigate small-scale farmers’ risk perception in bamboo forest management and directly stimulate their reinvestment willingness. Perceived bamboo forest certification reflects small-scale farmers’ perception of the current and potential benefits that certification can bring to bamboo forest management, including a comprehensive subjective evaluation of both psychological and actual outcomes. This study found that perceived bamboo forest certification also diminishes small-scale farmers’ risk perception in bamboo forest management and directly motivates their reinvestment willingness.

5.1. Main Findings of Government Support

In the model of this study, the variable with the highest direct effect coefficient on small-scale farmers’ reinvestment willingness is government support (β = 0.202, t = 4.124; p < 0.001). Furthermore, government support has the most pronounced effect in reducing small-scale farmers’ risk perception in bamboo forest management (β = −0.475, t = −7.522; p < 0.001). This highlights the crucial role of government support in enhancing small-scale farmers’ reinvestment willingness. However, based on the data from this survey, the mean values for the four items related to government subsidies, technical training, loans, and access to the latest market information are all below 3. This indicates that the current level of support provided by the government in these four aspects is insufficient. Providing support to small-scale farmers in these areas could greatly assist them in maintaining and increasing their investment in bamboo forest management.

5.2. Main Findings of Perceived Property Rights Security

Several studies conducted by scholars have indicated that property rights security needs to influence the perceived land tenure security of small-scale farmers in order to ultimately affect their land use behavior [29,50]. According to the model fit results, the ratio of the indirect effect to the total effect of perceived property rights security on small-scale farmers’ reinvestment willingness is 0.257. Among the variables exhibiting mediation effects in the model, perceived property rights security has the highest proportion of indirect effects, indicating that it relies more on the indirect impact of risk perception on small-scale farmers’ reinvestment willingness compared to the other three core variables. Based on the data from this survey, the average value of perceived property rights security among small-scale farmers ranges from 3.71 to 3.74, suggesting that the majority of small-scale farmers perceive property rights security above an average level. Since the distribution of forest land rights to small-scale farmers through collective forest tenure reform, there have been no significant adjustments to land tenure for a considerable period. Therefore, small-scale farmers hold a positive and optimistic attitude towards the future ownership of their forest land, believing that there will be no major adjustments in land rights. It can be anticipated that, if the government makes future adjustments to land tenure, it is likely to increase small-scale farmers’ perception of risks in land management, thus weakening their willingness to engage in land-based activities.

5.3. Main Findings of Perceived Bamboo Forest Certification

Among the four variables exhibiting mediation effects, perceived bamboo forest certification has the lowest proportion of indirect effects. By comparing the total effects, it is found that government support has the highest total effect on small-scale farmers’ willingness to invest (0.417), followed by perceived bamboo forest certification (0.258). This suggests that, despite the current limited extent of bamboo forest certification promotion and awareness, the majority of small-scale farmers still have a positive outlook on the future prospects of bamboo forest certification. Based on the data from this survey, the average value of perceived bamboo forest certification among bamboo forest management households ranges from 4.02 to 4.05, indicating that most small-scale farmers recognize the benefits that bamboo forest certification can bring to their management practices. It can be inferred that, as the promotion and dissemination of bamboo forest certification intensify and deepen, the impact of perceived bamboo forest certification on small-scale farmers’ reinvestment willingness will likely increase to some extent.

5.4. Main Findings of Group Decision Making

The total effect of group decision making on small-scale farmers’ reinvestment willingness in bamboo forest management is 0.209, and the ratio of indirect effect to direct effect is 0.124. This indicates that group decision making is more inclined to directly influence small-scale farmers’ reinvestment willingness in bamboo forest management. Based on the data from this survey, the average value of group decision making among bamboo forest management households ranges from 3.69 to 3.74. This suggests that the majority of small-scale farmers have fellow villagers or acquaintances involved in bamboo forest management. However, since small-scale farmers are making decisions regarding the reproduction of bamboo forest management, they can rely on the accumulated experience from the previous production cycle to make judgments. Therefore, the degree of influence from others may be diminished to some extent.

5.5. Main Findings of Risk Perception

Risk perception is a crucial mediating variable in the model of this study. Based on the data from this survey, the average value of risk perception among bamboo forest management households ranges from 3.04 to 3.53. This indicates that small-scale farmers still perceive certain risks in bamboo forest management. Among them, the highest perceived risk is market price fluctuations, followed by unstable product demand and susceptibility to natural disasters. Due to the high perception of property rights security, small-scale farmers have relatively lower risk perception regarding current forestry policy changes. Overall, despite the risk perception associated with bamboo plantation management, the combined influence of government support, perceived property rights security, perceived bamboo forest certification, and group decision making helps to control the impact of operational risks on small-scale farmers’ willingness to reinvest in their management within a reasonable range. Therefore, enhancing small-scale farmers’ reinvestment willingness in bamboo forest management can be achieved through increased government support, maintaining stable land tenure policies, promoting and disseminating bamboo forest certification, and strengthening information exchange among small-scale farmers.

5.6. Reinvestment Willingness, Perceived Value, and Market Influence

In our research model, we employed the variable of perceived value to assess the influence of market prices on bamboo forest management. Through on-site investigations and conversations with small-scale farmers, we discovered that, in years with higher bamboo, farmers tend to exhibit a higher inclination towards harvesting; in years with lower bamboo prices, they often display a more negative attitude towards harvesting. In China, the typical harvest cycle for bamboo is 3–5 years, which is shorter than most tree species but longer than conventional agricultural crops.

During the third year of the bamboo plantation cycle, if the market price for that particular year fails to meet the satisfaction of small-scale farmers, they may choose to refrain from harvesting bamboo until the price becomes satisfactory. This implies that, although small-scale farmers’ perceived value of bamboo plantations may fluctuate frequently in response to market price changes, the short-term controllability of harvest years mitigates the impact of short-term market price fluctuations (1–2 years) on bamboo plantation management. However, longer-term market price volatility (3 years or more) is likely to prompt farmers to reconsider the necessity of participating in the next cycle of bamboo plantation management.

5.7. Limitations and Future Research

Although our study has made significant contributions, it is important to consider some limitations. Previous research has found that risk preferences may influence farmers’ willingness to engage in land management activities. However, this aspect was not included in our model. To maintain a more concise and policy-relevant model, we chose to focus on risk perception, which is more easily influenced at the policy level. Compared to farmers’ risk preference characteristics, risk perception can be more effectively regulated from a policy standpoint. Additionally, it is commonly understood that most small-scale farmers are risk-averse individuals. Therefore, their decisions are more likely to be influenced by risk perception. Considering these factors, we selected risk perception as a representative variable for the risk factors in our study.

Furthermore, a limitation of this study is that it did not fully capture the impact of bamboo shoots on small-scale farmers’ reinvestment willingness. Due to the different production cycles of bamboo shoots and bamboo timber, bamboo shoots can be harvested twice a year. As a result, the variable of perceived property rights security in the model has a smaller impact on bamboo shoot production. Additionally, the current scope of bamboo forest certification only encompasses bamboo timber, excluding bamboo shoots. These factors may lead to insufficient explanatory power in the model for small-scale farmers primarily engaged in bamboo shoot production. In future research, it would be valuable to appropriately incorporate the dynamics of bamboo shoot production into the model to further enhance the theoretical framework of small-scale farmers’ reinvestment in bamboo forest management.

6. Conclusions

The aim of this study is to explore how to enhance small-scale farmers’ reinvestment willingness in bamboo forest management within the context of the current policy and market environment. It also aims to reveal the underlying mechanisms between subjective and objective influencing factors, which has not been systematically explored in the previous literature. This study employed structural equation modeling to test the proposed hypotheses in the theoretical model. The results demonstrate that, in the current policy and market environment, government support is found to be crucial in enhancing small-scale farmers’ reinvestment willingness in bamboo forest management. Additionally, perceived ecological certification has a positive effect on small-scale farmers’ reinvestment willingness, while risk perception played a significant mediating role. The findings of this study contribute to the improvement of the theoretical framework related to reinvestment in bamboo forest management and provide scientific insights for the government to develop effective and actionable policies.

Author Contributions

Y.H. (Yuan Huang): Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—original draft preparation. Y.H. (Yilei Hou): Writing—reviewing and editing. J.R. and J.Y.: Software, Investigation. Y.W.: Supervision, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Humanities and Social Sciences Youth Foundation, Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (19YJC630055) and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation Project (2023M743714).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the involvement of personal identity information in the data.

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous reviewers for their very useful comments that substantially improved the paper. As well as all respondents participating in the questionnaire survey.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interest or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Nath, A.J.; Lal, R.; Das, A.K. Managing woody bamboos for carbon farming and carbon trading. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2015, 3, 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Forestry Administration (SFA). China Forestry Statistical Yearbook 2014; China Forestry Press: Beijing, China, 2014. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sudhakara, K.; Jijeesh, C.M. Bamboos: Emerging carbon sink for global climate change mitigation. In Proceedings of the National Workshop on Carbon Sequestration in Forest and Non-Forest Ecosystems, Jabalpur, India, 16–17 February 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Paudyal, K.; Yanxia, L.; Long, T.T.; Adhikari, S.; Lama, S.; Bhatta, K.P. Ecosystem Services from Bamboo Forests. Key Findings, Lessons Learnt and Call for Actions from Global Synthesi; INBAR Working Paper; CGIAR System Organization: Montpellier, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yen, T.-M.; Lee, J.-S. Comparing aboveground carbon sequestration between moso bamboo (Phyllostachys heterocycla) and China fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata) forests based on the allometric model. For. Ecol. Manag. 2011, 261, 995–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. World Bamboo Resources: A Thematic Study Prepared in the Framework of the Global Forest Resources Assessment 2005; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2010: Main Report; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X. Impact of property rights reform on household forest management investment: An empirical study of southern China. For. Policy Econ. 2013, 34, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Gong, P.; Han, X.; Wen, Y. The effect of collective forestland tenure reform in China: Does land parcelization reduce forest management intensity? J. For. Econ. 2014, 20, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xia, J. Forest harvesting restriction and forest restoration in China. For. Policy Econ. 2021, 129, 102516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degnet, M.B.; van der Werf, E.; Ingram, V.; Wesseler, J. Forest plantations’ investments in social services and local infrastructure: An analysis of private, FSC certified and state-owned, non-certified plantations in rural Tanzania. Land Use Policy 2018, 79, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico-Straffon, J.; Wang, Z.; Panlasigui, S.; Loucks, C.J.; Swenson, J.; Pfaff, A. Forest concessions and eco-certifications in the Peruvian Amazon: Deforestation impacts of logging rights and logging restrictions. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2023, 118, 102780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, T.; Teklay, G.; Mulatu, D.W.; Rannestad, M.M.; Meresa, T.M.; Woldelibanos, D. Forest benefits and willingness to pay for sustainable forest management. For. Policy Econ. 2022, 138, 102721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Zhu, S.; Cao, M.; Kang, X.; Du, J. Does rural labor outward migration reduce household forest investment? The experience of Jiangxi, China. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 101, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Xu, Z.; Shen, Y.; Huang, C.; Zhang, Y. How off-farm work drives the intensity of rural households’ investment in forest management: The case from Zhejiang, China. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 98, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M.; Gong, P. Risk preferences, risk perceptions and timber harvest decisions—An empirical study of nonindustrial private forest owners in northern Sweden. For. Policy Econ. 2010, 12, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Ning, Z.; Chang, W.-Y.; Chang, S.J.; Yang, H. Optimal harvest decisions for the management of carbon sequestration forests under price uncertainty and risk preferences. For. Policy Econ. 2023, 151, 102957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julia Ihli, H.; Chiputwa, B.; Winter, E.; Gassner, A. Risk and time preferences for participating in forest landscape restoration: The case of coffee farmers in Uganda. World Dev. 2022, 150, 105713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica 1979, 47, 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuong, Q.H. Mindsponge Theory; Walter de Gruyter GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valarie, A. Zeithaml, Consumer Perceptions of Price, Quality, and Value: A Means-End Model and Synthesis of Evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummeneje, A.-M.; Rundmo, T. Attitudes, risk perception and risk-taking behaviour among regular cyclists in Norway. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2020, 69, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahesh, G.; Abdulsattar, H.; Abou Zeid, M.; Chen, C. Risk perception and travel behavior under short-lead evacuation: Post disaster analysis of 2020 Beirut Port Explosion. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 89, 103603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, K.; Cao, S.; Liu, Y.; Xu, D.; Liu, S. Disaster-risk communication, perceptions and relocation decisions of rural residents in a multi-disaster environment: Evidence from Sichuan, China. Habitat Int. 2022, 127, 102646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Brewer, M.B.; Hayes, B.K.; McDonald, R.I.; Newell, B.R. Predicting climate change risk perception and willingness to act. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 65, 101331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Ntim-Amo, G.; Xu, D.; Gamboc, V.K.; Ran, R.; Hu, J.; Tang, H. Flood disaster risk perception and evacuation willingness of urban households: The case of Accra, Ghana. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 78, 103126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Xiao, G.; Ye, B.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, M.; Wang, X.; Yang, Q. The relationship between risk perception of COVID-19 and willingness to help: A moderated mediation model. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2022, 137, 106493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broegaard, R.J. Land tenure insecurity and inequality in Nicaragua. Dev. Chang. 2005, 36, 845–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Du, J.; Ye, C.; Zhang, Q. Your misfortune is also mine: Land expropriation, property rights insecurity, and household behaviors in rural China. J. Comp. Econ. 2022, 50, 1068–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muyeba, S. Banking on receipts and political declarations: Perceived tenure security and housing investments in Luanda, Angola. Habitat Int. 2023, 138, 102866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasibuan, A.M.; Wulandari, S.; Ardana, I.K.; Wahyudi, A. Understanding climate adaptation practices among small-scale sugarcane farmers in Indonesia: The role of climate risk behaviors, farmers’ support systems, and crop-cattle integration. Resour. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 13, 100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ding, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhao, M. How far are green products from the Chinese dinner table?—Chinese farmers’ acceptance of green planting technology. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 410, 137141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Sun, H.; Zhou, Y.; Qin, F.; Guan, X. Examining the impact of forestry policy on poor and non-poor farmers’ income and production input in collective forest areas in china. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 276, 123784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.V. A Simple Model of Herd Behavior. Q. J. Econ. 1992, 107, 797–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikhchandani, S.; Welch, H.I. A Theory of Fads, Fashion, Custom, and Cultural Change as Informational Cascades. J. Polit. Econ. 1992, 100, 992–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. Commentary: Issues and Opinion on Structural Equation Modeling. MIS Q. 1998, 22, vii–xvi. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; The Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, L.; Sun, Z.; Zha, L.; Liu, F.; He, L.; Sun, X.; Jing, X. Environmental awareness and pro-environmental behavior within China’s road freight transportation industry: Moderating role of perceived policy effectiveness. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 252, 119796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Thiele, K.O. Mirror, mirror on the wall: A comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, F.; Berbekova, A.; Assaf, A.G. Understanding and managing the threat of common method bias: Detection, prevention and control. Tour. Manag. 2021, 86, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, C.M.; Simmering, M.J.; Atinc, G.; Atinc, Y.; Babin, B.J. Common methods variance detection in business research. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3192–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Du, H.; Southworth, F.; Ma, S. The influence of social-psychological factors on the intention to choose low-carbon travel modes in Tianjin, China. Transp. Res. Part Policy Pract. 2017, 105, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aha, B.; Ayitey, J.Z. Biofuels and the hazards of land grabbing: Tenure (in)security and indigenous farmers’ investment decisions in Ghana. Land Use Policy 2017, 60, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran-Nam, Q.; Tiet, T. The role of peer influence and norms in organic farming adoption: Accounting for farmers’ heterogeneity. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 320, 115909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrahill, K.; Macken-Walsh, Á.; O’Neill, E. Prospects for the bioeconomy in achieving a Just Transition: Perspectives from Irish beef farmers on future pathways. J. Rural Stud. 2023, 100, 103020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinda, J.A.; Williams, L.B.; Kay, D.L.; Alexander, S.M. Flood risk perception and responses among urban residents in the northeastern United States. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 64, 102528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelder, J.-L. van Feeling and thinking: Quantifying the relationship between perceived tenure security and housing improvement in an informal neighbourhood in Buenos Aires. Habitat Int. 2007, 31, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).