Abstract

Providing memorable tourism experiences (MTEs) plays a crucial role in determining the competitiveness and sustainability of a destination for not only the business sector, but also the environment. Therefore, destination managers face a challenge in identifying, facilitating, and maintaining memorable tourism experiences among visitors. Although MTEs have been increasingly studied, research of the effects of MTEs on word-of-mouth and revisit behavior intentions is still at an early stage of development, particularly in the forest recreation context. The objectives of this study were twofold: To assess visitors’ MTEs in a selected forest recreation destination and to examine the effects of MTEs on word-of-mouth and revisit intentions. This study identified key memorable experiences of visitors in Xitou Nature Education Area (XNEA), Taiwan (R.O.C.), and examined the relevant relationships among MTEs and behavioral intentions. The results revealed that both refreshment and involvement experiences received the highest scores from the respondents, whereas perceived local culture received the lowest score. Refreshment, local culture, and involvement positively influenced the word-of-mouth intention of visitors. Additionally, hedonism, local culture, and involvement significantly positively influenced the revisit intention of visitors. This study provides additional insights into MTEs in nature-based tourism. The study results underline the importance of MTEs in forest recreation destinations that can encourage more word-of-mouth and revisit intentions of tourists.

1. Introduction

1.1. Memorable Tourism Experiences

Memorable tourism experiences (MTEs) refer to the positive tourism experiences that are memorized and recollected after the activity has finished [1]. This concept is concordant with Pine and Gilmore [2], who suggested that “experiences” form the fourth economic offering in addition to commodities, goods, and services. They suggested that providing quality experiences would have a sustainable competitive advantage. Therefore, understanding and improving the recollection of these positive memories of tourists is a suitable strategy for promoting the competitive advantage in the tourism marketplace [3,4,5,6]. Additionally, competitiveness is a key factor in tourism destination management and marketing [4]. From a competitive advantage perspective, managers can increase the value of existing resources through accessibility improvement, local people hospitality, and competitive pricing [7]. Adding services that are distinct and beyond expectation seems to facilitate the creation of memorable experiences [2,5,8,9,10]. Additionally, Kim et al. [11] highlighted that, from a tourism standpoint, delivering a highly meaningful experience to visitors is required.

Numerous initiatives that discuss the need for experience delivery have been proposed [12]. Recently, several scholars have investigated the essence and process of MTE formation. In order to understand the cognitive process using an in-depth interview, a four-dimension MTE (i.e., affect, expectations, consequentiality, and recollection) has been proposed [13], whereas for the senior travel market, a five-dimension MTE (i.e., identity formation, family milestones, relationship development, nostalgia reenactment, and freedom pursuits) has been identified [14]. Chandralal, Rindfleish, and Valenzuela [15] investigated and captured a seven-dimension MTE (i.e., authentic local experiences, personally significant experiences, shared experiences, perceived novelty, perceived serendipity, professional guides and tour operator services, and affective emotions) from two well-known travel blogs. Coelho, Gosling, and Almeida [16] proposed a three-dimension MTE (i.e., personal, relational, and environmental) and three stages of MTE formation (i.e., ambiance, socialization, and emotions and reflection). Recently, with respect to a psychological perspective, the MTE concept has been intertwined with long-term memory [17] that encompasses three stages of memory formation, namely encoding, consolidation, and retrieval [18].

To date, the seven-dimension MTE, which includes hedonism, refreshment, local culture, meaningfulness, knowledge, involvement, and novelty, is the most acknowledged [16,19,20]. In this case, MTE is defined as “a tourism experience positively remembered and recalled after the event has occurred” ([19], p.13) Each of the seven MTE dimensions are briefly discussed as follows:

- Hedonism: Hedonism has been recognized as a predominant component of tourism and leisure activities. Tourists primarily seek enjoyment (hedonism or pleasure) while “consuming” tourism products. Otto and Ritchie [21] reported that tourism products and services contributed to consumption for hedonic purposes and positive emotions associated with happiness experiences, essentially explaining the essence of MTEs. In an empirical study, hedonism was identified as a crucial factor of the perceived value in cruise travel [22].

- Refreshment: Cohen ([23], p.181) defined tourism activity as “essentially temporary reversal of everyday activities—it is a no-work, no-care, no-thrift situation”. Individuals seek solitude or relaxation during travel experiences to fulfill their psychological needs and to escape from boredom of daily life during a travel experience [23]. Empirical research highlighted the importance of escapism and refreshment in travel experiences; for example, Leblanc [24] found that tourists who attended special events and festivals had rest and relaxation as their major motivations. Kim [25] identified that a feeling of being refreshed enhanced the memorability of tourism experiences.

- Local culture: To understand the local culture, travelers interact with local people or residents at a tourist destination, and experiencing the local culture is considered a crucial motivational factor for traveling. Morgan and Xu [26] found student travelers construct memorable holiday experiences while they are interacting with local culture and people. Additionally, learning host communities’ way of life and their language enhanced MTEs [13]. In short, experiencing local culture makes travel more meaningful and memorable and significantly enhances MTEs [19,25].

- Meaningfulness: Considering the meaningful component of MTEs, travelers seek meaningful experiences, such as sense of physical, emotional, or spiritual fulfillment, through tourism [27,28]. Some visitors seek unique and meaningful travel experiences to satisfy their needs and desires, and they consider tourism experiences as an inner journey of personal growth or self-development [3,29,30]. Kim and Ritchie [3] found that meaningful tourism experiences lasted longer in human memory, with some of these experiences being the most memorable in a lifetime. This, in turn, influenced the decision-making process.

- Knowledge: Tourism literature also report that learning new things and developing new skills can result from tourism experiences [3]. Acquiring knowledge has been suggested as a psychological motivation to travel to areas with geographical, historical, language, and/or cultural importance [3,31,32]. Tung and Ritchie [13] identified that intellectual development was a significant component of memorable experiences in understanding the essence of MTEs. In other words, gaining new knowledge demonstrated strong impacts on memory.

- Involvement: Pine and Gilmore [2] suggested that individuals are more likely to have a memorable experience when they are involved in an activity. Tourists remember an experience closely related to their interests and develop involvement through active participation in tourism programs during the on-site phase of tourism experiences [3]. In other words, when visitors find themselves immersed in a leisure activity, they are more likely to have a memorable experience.

- Novelty: Novelty seeking is considered a significant component of the tourism experience [22,33]. Studies on MTEs have found that individuals recall and remember novel tourism experiences better than other experiences [19] and highlighted a strong causal connection between novelty and human memory [34].

It should be further noted that memory literature suggests memorable experiences can be both positive and negative, however, visitors tend to more easily recall positive experiences than negative ones [19]. Currently, the seven-dimension MTE comprehensively captures the important components of the tourism experience affecting visitors’ memory. This, in turn influences their behavior intention—for example, hedonism, which is considered an integral part of leisure experiences as well as an important factor in determining satisfaction and future destination choices [16,19,20]. Providing memorable experiences is important as it increases positive behavior intention. Destination managers can allocate their resources effectively to the seven dimensions of experiences when developing tourism programs; for example, including opportunities to experience local culture in tourism programs or providing meditation courses for personal relaxation.

1.2. MTEs and Loyalty Behavior

The MTEs represent the environment and achievement of performance of a tourism destination that contributes to visitors’ memory and then influences loyalty behavior [4,5,35]. In other words, if tourists perceive better memorable experiences at a tourism destination, this will presumably lead to higher word-of-mouth (WOM) and revisit intentions. Empirical research in tourism also reports the effect of positive MTEs on future destination choices. For instance, Wirtz [36] highlighted that recalled tourism experiences were the best predictors in the decision-making process for taking a similar vacation in the future. Additionally, former outdoor recreation activity participation was directly associated with a similar undertaking afterward [37,38]. Some studies [11,39] have revealed that MTEs significantly affect future behavioral intentions (i.e., revisit, re-practice, and WOM). Positive WOM from past visitors has been proven to be one of the most effective means of promotion to bring new visitors to a destination [11,40]. Thus, in the present study, we expected that MTE affected visitors’ WOM and revisit intention.

1.3. Study Significance

Apart from general mass tourism, nature-based tourism is a rapidly growing field [41] that encompasses sustainable tourism concepts, such as reducing unpleasant environmental and social impact, increasing economic impacts, and encouraging meaningful experiences [42]. To achieve these goals, information—such as feedback provided by tourists in a formal procedure—is necessary [42], which assists destination marketers and managers in monitoring their MTEs delivery power along with tourist loyalty [1]. The importance of nature-based tourism for marketing and developing tourism destinations, as well as for delivering memorable experiences, are crucial topics. It has been suggested that destination managers can use MTEs as a managerial tool to evaluate the performance of business and make an effort to create and design proper practices for delivering memorable tourism experiences, which are aimed at improving positive behavioral intentions [3,19]. From a managerial perspective, providing memorable experiences—as well as increasing visitation in Xitou Nature Education Area (XNEA)—is an important task for the management team. Thus, understanding visitors’ experiences and their loyalty to XNEA is essential. This research was supported by XNEA to identify, facilitate, and maintain visitors’ MTEs and, consequently, provide quality experiences and promote the tourist destination.

To this end, the purposes of this study were to use Kim’s seven-dimensions MTE scale [19] in a new context and to assess visitors’ memorable tourism experiences in XNEA. In addition, the study aimed to develop a causal relationship model to investigate the way MTEs affect tourist WOM and revisit intentions. Validity and reliability of the MTE scale were previously confirmed in a Taiwanese sample and the scale could be applied to testing memory- and loyal behavior-related theories in a tourism setting ([3], p.331) The results of this study add knowledge to MTEs and their consequences in the new context, as well as allowing for better understanding of MTEs in the current context and their importance in determining destination competitiveness. In short, the current study assessed MTEs and examined memorable experiential factors on future behavior. Our findings may assist managers in more effectively allocating their resources and increasing tourism competitiveness when designing and planning programs in order to deliver MTEs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Hypotheses

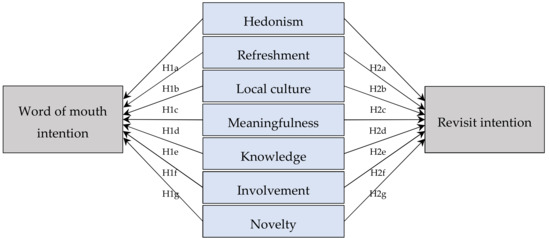

This research assessed visitor MTEs in a selected forest recreation area, which is a popular nature-based tourist destination. Additionally, a visitors’ MTEs and behavioral intentions formation model was developed based on the aforementioned tourism marketing literature. Research hypotheses specified the relationships among MTEs, WOM, and revisit intentions. The visitors’ MTEs and behavioral intentions formation model are described in Figure 1. This model suggests that MTEs positively affect behavioral intentions in the context of nature-based tourist destination. On the basis of the previous discussion, causal paths between the MTEs and future behavior were developed. The following hypotheses were identified:

Figure 1.

Model and hypotheses of memorable tourism experiences (MTEs) and behavioral intentions of visitors.

2.1.1. Hypothesis 1: MTEs Positively Influence WOM Intention

- Hypothesis 1a: Hedonism experience positively influences WOM intention.

- Hypothesis 1b: Refreshment experience positively influences WOM intention.

- Hypothesis 1c: Local culture experience positively influences WOM intention.

- Hypothesis 1d: Meaningfulness experience positively influences WOM intention.

- Hypothesis 1e: Knowledge experience positively influences WOM intention.

- Hypothesis 1f: Involvement experience positively influences WOM intention.

- Hypothesis 1g: Novelty experience positively influences WOM intention.

2.1.2. Hypothesis 2: MTEs Positively Influence Revisit Intention

- Hypothesis 2a: Hedonism experience positively influences revisit intention.

- Hypothesis 2b: Refreshment experience positively influences revisit intention.

- Hypothesis 2c: Local culture experience positively influences revisit intention.

- Hypothesis 2d: Meaningfulness experience positively influences revisit intention.

- Hypothesis 2e: Knowledge experience positively influences revisit intention.

- Hypothesis 2f: Involvement experience positively influences revisit intention.

- Hypothesis 2g: Novelty experience positively influences revisit intention.

2.2. Study Site

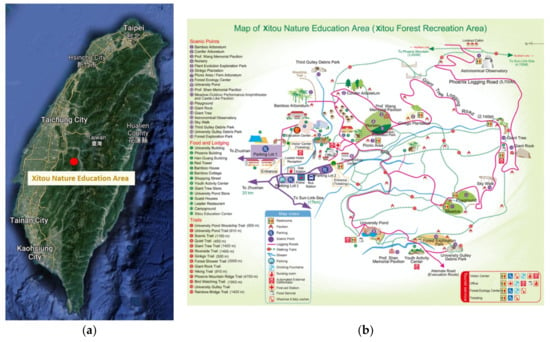

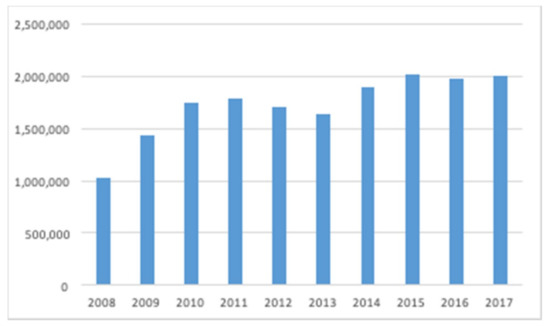

The field survey was conducted in Xitou Nature Education Area (XNEA), Taiwan (R.O.C.), which belongs to the Experimental Forest, College of Bio-Resources and Agriculture, National Taiwan University. The Experimental Forest was founded in 1901 during a period of Japanese occupation, and its four major objectives are as follows: Academic research, education, resources conservation, and forest management demonstration. XNEA is located in the Experimental Forest that was turned into a forest recreation area in 1970. Surrounded by Feng-Huang mountains in the east, west, and south sides, XNEA is a concave valley covering approximately 2200 hectares and ranging from 800 to 2000 meters in elevation [43]. The monthly average temperature at XNEA is 11–20.8 °C and the average annual temperature is 16.6 °C [44]. With high humidity and cool weather, XNEA is regularly covered with clouds and fog. Further, it is also a home to approximately 300 tree, 1300 herbaceous plant, 96 bird, and 20 reptile species. XNEA has scenic spots, such as the Forest Ecological Exhibition Center, University Pond, Memorial Pavilion, Giant Tree, Bamboo Cottage, and Astronomical Observatory, which are connected to hiking trails. Additionally, ecological interpretation service, environmental education, food, and accommodation services are provided (Figure 2) [45]. XNEA is a popular natural tourist destination for outdoor activities, nature sightseeing, and social interaction in Taiwan. Moreover, it is an important and popular forest recreation area in Taiwan with a well-organized landscape, including outdoor recreation facilities, with approximately 2 million visitors annually during 2015–2017 (Figure 3) [46].

Figure 2.

Xitou Nature Education Area (XNEA) location and site map (source: Google Earth (a); About the Nature Education Area (b, [45]).

Figure 3.

Annual tourist arrivals.

2.3. Measures

The seven-dimension MTE scale developed and cross-validated by Kim and his colleagues [3,19] was used. The scale has 24 items, loading four items for hedonism, four for refreshment, three for local culture, three for meaningfulness, three for knowledge, three for involvement and four for novelty. Memorable tourism experience was measured by asking participants about their memorable tourism experiences in XNEA and scored each of the tourism experience-related items on the 7-point Likert type scale ranging from 1 (I have not experienced at all) to 7 (I have experienced very much). Additionally, participants’ WOM and revisit intention were asked. Two items, “revisit Xitou in two years” and “recommend Xitou to friends”, were measured using a 5-point Likert type scale. Further, socio-demographics and travel patterns were collected.

2.4. Data Collection

A pilot test of the study questionnaire was conducted with 40 subjects for its readability. To ensure data accuracy and a favorable response rate, the face-to-face interview method was used for data collection, which allowed the interviewers to provide additional explanations and to answer questions. The data were collected using a convenient sampling approach during January 23, 2015 to January 26, 2015 between 10:00 to 17:00 h at XNEA. Five interviewers were randomly assigned to the popular tourist spots inside XNEA, such as the University Pond, visitor center, and Giant Tree. A total of 450 questionnaires were distributed, of which 24 invalid questionnaires and 426 valid questionnaires were returned in total, representing an overall response rate of 94.7%. The analyses included descriptive analysis, reliability tests, and multiple regression by using SPSS 21.0. (IBM Corporation, NY, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Respondent Profile

The analysis results of the respondent profile are presented in Table 1. The number of female respondents in this survey was slightly higher (52.5%) than that of male respondents (47.5%). In terms of age, young adults aged 21–30 years (30.8%) accounted for the highest proportion, followed by middle-aged adults aged 41–50 years (18.8%) and early-middle-aged adults aged 31–40 years (17.8%). Late-middle-aged adults (51–60 years), those aged <20 years, and older adults (>61 years) accounted for 14.3%, 11.3%, and 7.0% of the sample, respectively. Regarding the level of education, the majority of the respondents had a college degree (57.5%), and 21.9% of the respondents had a postgraduate degree. Regarding monthly income, the largest proportion of respondents (30%) earned a monthly income of NT$20,001–NT$40,000, followed by those who earned less than NT$20,000 (27.2%). Regarding marital status, the proportion of married (50.6%) and single (49.4%) respondents were approximately identical. Regarding area of residence, most visitors were from the adjacent area of Middle Taiwan, namely Taichung, Changhua, and Nantou counties (43.2%), followed by visitors from Northern Taiwan (23.2%), and those from Eastern Taiwan (0.5%). Regarding the visiting frequency in the year surveyed, 54.2% of the respondents visited XNEA for the first time, followed by those who have visited more than five times (25.9%) and those who have visited two–four times (19.8%). These data revealed that XNEA attracted numerous new visitors as well as substantial loyal customers. Regarding the size of trip group, groups of more than five people (37.3%) accounted for the greatest proportion, followed by groups of four (25%) and two (24.1%). Regarding the type of travel companion, family members and relatives accounted for the majority of combinations (51.7%), followed by friends (29%).

Table 1.

Respondent profile.

3.2. Descriptive Analysis and Reliability of the MTE Dimensions

As shown in Table 2, as a rule of thumb, Cronbach’s alpha values greater than 0.7 confirmed the internal reliability of the MTE dimensions. For the descriptive analyses, “refreshment” obtained the highest level of respondent perception, with an average score of 5.81, followed by “involvement,” which attained an average score of 5.33. “Local culture” received the lowest level of respondent perception, obtaining a significantly lower score of 4.64. The items that generated the highest levels of perceived MTE were in the order of “enjoyed sense of freedom” (6.04) and “liberating” (6.00) in the “refreshment” dimension and “really enjoyed this tourism experience” (5.66) in the “hedonism” dimension. By comparison, the items that created the lowest levels of perceived MTE were in the order of “closely experienced the local culture” (4.28) in the “local culture” dimension and “thrilled about having a new experience” (4.32) in the “hedonism” dimension.

Table 2.

Descriptive analysis and reliability of the MTE dimensions.

3.3. Hypothesis Testing

Table 3 presents the results of regression analysis of hypothesis testing. The regression model overall had an explanatory power of 22.1% for the relationship between MTEs and visitor WOM. The results indicated that “refreshment,” “local culture,” and “involvement” all exerted significantly positive effects on visitor WOM intention. However, “hedonism” and “novelty” did not significantly influence visitor WOM intention. In addition, the “knowledge” dimension had a significantly negative influence on visitor WOM intention, indicating that tourists receiving more knowledge are less likely to recommend to friends. Regarding the regression analysis of the relationship between MTEs and visitor revisit intention, the overall model exhibited an explanatory power of 19.4%. In terms of the effects of MTE dimensions on visitor revisit intention, “hedonism,” “local culture,” and “involvement” exerted significantly positive influences. “Refreshment” exerted a positive but nonsignificant effect. By contrast, the remaining MTE dimensions, namely “meaningfulness,” “knowledge,” and “novelty” exerted a negative but nonsignificant effects (see Table 3). The results of hypothesis testing are summarized and illustrated in Table 4.

Table 3.

Influences of memorable tourism experiences on word-of-mouth intention and revisit intention.

Table 4.

Results of hypothesis testing.

4. Discussion

4.1. Assessment of MTEs in XNEA

The study demonstrated that, in sequence, the most to least memorable tourism experiences of visitors in XNEA were those associated with the dimensions of refreshment, involvement, hedonism, knowledge, novelty, meaningfulness, and local culture. Refreshment seems to be the most prominent dimension at forest recreation settings, such as XNEA, where the majority of tourists are at the family stage. This finding is consistent with that of a previous study [47], which mentioned that people in this life stage prefer to use their vacation for the purposes of relaxation, peace of mind, and obtaining nature experiences. At XNEA, visitors felt at ease, relaxed, relieved, and became revitalized. Involvement and hedonism were also rated by the XNEA visitors as major memorable experiences. A previous study on XNEA reported that visitors participated in and greatly enjoyed various activities related to eco-tourism that were provided on-site [48], such as breathing fresh air, hiking, and strolling around. However, because the type of tourism at XNEA is nature- and relaxation-oriented, visitors experienced relatively less in novelty- and meaningfulness-related experiences. In addition, visitors do not have much opportunity to experience the local culture because XNEA is a semi-enclosed educational forest park. Consequently, the respondents’ perceived level of cultural experience was relatively low.

4.2. Effects of MTEs on WOM and Revisit Intention

Studies have shown that MTE dimensions affect tourist WOM and revisit intentions. Furthermore, the present study conducted separate regression analyses of the relationships between the MTE dimensions and visitor WOM intentions, as well as between the MTE dimensions and visitor revisit intentions. A detailed examination based on regression analyses of the effect of each MTE dimension on visitor WOM and revisit intentions indicated that refreshment, local culture, and involvement dimensions positively influenced visitor WOM intentions, whereas hedonism, local culture, and involvement dimensions significantly positively influenced visitor revisit intentions. Apparently, local culture and involvement dimensions are significant factors contributing to the willingness of a visitor to recommend the place to their friends and to visit again. This is consistent with previous reports, which suggest that the most memorable holiday experiences include social interaction (e.g., local culture) [26]. Additionally, the results of an outdoor recreation experience model implied that an on-site experience stage was an authentic participation experience due to the environment [49]. Moreover, developing tourism products that encourage tourists to further connect with local communities or immerse in natural surroundings is essential to creating a memorable impression [42].

In the present study, nonsignificant relationships between meaningfulness and WOM, as well as revisit intention, were found. This concurs with Kim and Ritchie’s study concerning a Taiwanese sample, wherein their results demonstrated that the relationship between meaningfulness and loyal behavior intention was nonsignificant [3]. The respondents in the present study preferred to have stress-relieving experiences in the current tourism context rather than seeking personal growth or self-development. The novelty dimension exerted nonsignificant influences on both visitor WOM and revisit intentions. Interestingly, this influence was rated oppositely; that is, novelty positively affected the WOM intention and negatively affected the revisit intention. This finding implies that when visitors are merely seeking novelty-related experiences, the higher levels of novelty they experience in a place, the less likely they are to revisit it. This was consistent with previous studies, which reported that tourists whose main purpose was to experience novelty were less likely to revisit a place; however, they would recommend that place to others [14,50]. Further, the knowledge dimension exerted a significantly negative effect on visitors’ WOM intention. This was similar to a finding reported by Kim et al. [3], who found knowledge negatively affected loyal behavior intentions. A plausible explanation for the current result is that acquiring new knowledge in XNEA is not worth recommending a visit to the destination to friends, as visitors may believe their friends already know the destination well (since XNEA is a popular forest recreation destination) and thus may have already familiarized themselves with the destination’s information. Additionally, visitors’ major purposes of visiting XNEA were to relax and to have fun, while acquiring knowledge seemed to cause pressure. Kim and Ritchie [3] proposed a similar idea and inferred that because of differences in governmental policies, social structure, and resource distribution, Asians typically experience greater competitive pressure than Westerners do. Consequently, Asian tourists tend to show greater eagerness in stress release and refreshment during traveling and, therefore, exhibit little enthusiasm in absorbing new knowledge. Therefore, visitors who rate higher knowledge are less likely to tell others to visit.

4.3. Managerial Implications

Providing tourists with memorable experiences can bridge tourism with competitiveness and sustainability, which must be monitored by managers to ensure tourism competitiveness [6]. From a managerial perspective, the major objectives of the XNEA management team are to provide memorable recreational experiences and increase visitation. Thus, understanding visitors’ experiences and their loyalty to XNEA is essential. To this end, considering the local culture dimension rated the lowest—but significantly influenced WOM and revisit intentions—the XNEA management team should firstly allocate resources to increasing local culture experiences. For example, tea and bamboo production are strong industries, as well as a prominent culture in the region. Thus, holding tea and bamboo festivals in XNEA could improve tourist memorable experiences and, consequently, significantly affect tourist WOM and revisit intentions. Additionally, the Bunun tribe, located near XNEA, has culture and artistry which are unique worldwide. Introducing indigenous cultural activities to XNEA, such as those associated with the Bunan tribe, may help visitors have a better understanding of local culture and increase their hedonism. It should be further acknowledged that new and more opportunities of local culture experiences contribute to WOM and revisit intentions, as well as increasing visitation. Moreover, bringing in the local culture can enhance the connection between XNEA and local communities that builds tourism competitiveness and sustains tourism business.

Second, an interesting finding illustrated that knowledge negatively influenced the WOM element. This result highlights the fact that delivering knowledge may hurt visitation; however, one of the major purposes of XNEA is education. A practical application for managers could be re-designing environmental education programs for delivering more enjoyable, refreshing, actively participating and exciting experiences, as well as embedding forest and nature knowledge in these programs. Moreover, providing more forest recreation programs, such as tree climbing and forest bathing, could contribute to visitor refreshment, hedonism and involvement experiences. In other words, a wide variety tourism program with a focus on refreshment, involvement and hedonism can strengthen visitors’ memorable experiences.

4.4. Limitations and Future Research

In this study, MTE assessment questionnaires were distributed to visitors on site. In contrast to previous studies [3,13,50] that asked respondents to recall their most memorable recent tourism experience, the present study asked the respondents to answer the questionnaire immediately after their visit to a specific tourist destination. A similar research method was applied by previous studies [51,52] to examine the relation between visitor memory and loyalty to a specific leisure destination. This approach likely enabled the respondents to have a vivid memory of their tourism experience, which, consequently, led to a higher rating of the memorable level of each dimension compared with the approach that asked respondents to recall more distant past experiences. The notion regarding alteration or distortion of behaviors, experiences, and memories of a tourist with time [17] led Jang and Feng [53] to suggest that tourist revisit intention is continuously varied. To obtain more instinctive data that reflects memorable elements of travel experiences without any cues at the study site, future studies must include participants who return to the destination and actual WOM spreading, while measuring the memorable level not immediately after the tourism experience, but after a period of time. This can yield more accurate results and reflect the memorable elements of travel experiences more realistically. Furthermore, the present MTE questionnaire did not reflect negative MTE dimensions, such as unpleasantness and anger. Although these tourism experiences are different from some studies that mainly focused on positive experiences [1,11,13,19,54], negative experiences, such as pain, hardship, and limitation, can also generate distinct and memorable experiences [38]. These were the limitations of this study questionnaire. A questionnaire that covers dimensions related to negative experiences can solve this problem and researchers can use it to explore the relationship of negative MTE dimensions with tourist behaviors, as well as negative MTE dimensions with service failure.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study revealed that both refreshment and involvement experiences received the highest score from the respondents, whereas perceived local culture received the lowest score. The seven dimensions of experiences influencing WOM and revisit intentions may not be always the case. In the context of nature-based tourism at XNEA, refreshment, local culture, and involvement positively influenced the visitor WOM intention; hedonism, local culture, and involvement produced significantly positive influences on revisit intentions of the visitor. Our results suggest that local culture should be integrated into the offered tourist experiences. Additionally, providing tourism programs focusing on refreshment, involvement and hedonism can strengthen visitors’ memorable experiences.

Author Contributions

Funding acquisition, conceptualization, supervision and manuscript writing, reviewing and editing was performed by C.-P.Y.; W.-C.C. performed field investigation and data analysis; and draft preparation, reviewing, and editing was performed by J.R.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (grant number 105-2628-H-002-004-MY2) and the National Taiwan University Experiment Forest (grant number 2019-A03-2).

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the staff of Xitou Nature Education Area (XNEA) for their help. Additionally, special thanks to reviewers for their careful review and constructive comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kim, J.-H. The Impact of Memorable Tourism Experiences on Loyalty Behaviors: The Mediating Effects of Destination Image and Satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 856–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy; Harvard Business School Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.-H.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Cross-Cultural Validation of a Memorable Tourism Experience Scale (MTES). J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M. Repeaters’ behavior at two distinct destinations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 784–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehto, X.Y.; O’Leary, J.T.; Morrison, A.M. The effect of prior experience on vacation behavior. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 801–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.R.B.; Crouch, G.I. The Competitive Destination: A Sustainable Tourism Perspective; Cabi: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch, G.I.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Tourism, Competitiveness, and Societal Prosperity. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 44, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, J.H.; Pine, B.J. Differentiating hospitality operations via experiences: Why selling services is not enough. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 2002, 43, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthiou, A.; Kang, J.; Chiang, L.; Tang, L. Investigating the Effects of Memorable Experiences: An Extended Model of Script Theory. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 362–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, L.L.; Carbone, L.P.; Haeckel, S.H. Managing the Total Customer Experience. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2002, 43, 85–89. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.-H.; Ritchie, J.R.B.; Tung, V.W.S. The Effect of Memorable Experience on Behavioral Intentions in Tourism: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Tour. Anal. 2010, 15, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M. Making space for experiences. J. Retail Leis. Prop. 2006, 5, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, V.W.S.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Exploring the essence of memorable tourism experiences. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 1367–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, V.W.S.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Investigating the Memorable Experiences of the Senior Travel Market: An Examination of the Reminiscence Bump. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2011, 28, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandralal, L.; Rindfleish, J.; Valenzuela, F. An Application of Travel Blog Narratives to Explore Memorable Tourism Experiences. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 20, 680–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas Coelho, M.; de Sevilha Gosling, M.; de Almeida, A.S.A. Tourism experiences: Core processes of memorable trips. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 37, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, V.W.S.; Lin, P.; Qiu Zhang, H.; Zhao, A. A framework of memory management and tourism experiences. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 853–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadel, L.; Hupbach, A.; Gomez, R.; Newman-Smith, K. Memory formation, consolidation and transformation. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2012, 36, 1640–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Ritchie, J.R.B.; McCormick, B. Development of a Scale to Measure Memorable Tourism Experiences. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Hallab, Z.; Kim, J.N. The Moderating Effect of Travel Experience in a Destination on the Relationship between the Destination Image and the Intention to Revisit. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2012, 21, 486–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, J.E.; Ritchie, J.R.B. The service experience in tourism. Tour. Manag. 1996, 17, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, T.; Mattila, A.S. The role of affective factors on perceived cruise vacation value. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. A Phenomenology of Tourist Experiences. Sociology 1979, 13, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leblanc, M. Tourist characteristics and their interest in attending festivals and events: An Anglophone/francophone case study of New Brunswick, Canada. Event Manag. 2003, 8, 203–212. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.-H. Determining the Factors Affecting the Memorable Nature of Travel Experiences. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2010, 27, 780–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.; Xu, F. Student Travel Experiences: Memories and Dreams. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2009, 18, 216–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callanan, M.; Thomas, S. Chapter 15—Volunteer tourism: Deconstructing volunteer activities within a dynamic environment. In Niche tourism: contemporary issues, trends and cases; Novelli, M., Ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 183–200. [Google Scholar]

- Digance, J. Pilgrimage at contested sites. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiler, B.; Hall, C.M. Special Interest Tourism; Belhaven Press: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, M.; Novelli, M. Niche tourism: An introduction. In Niche tourism: contemporary issues, trends and cases; Novelli, M., Ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Poria, Y.; Reichel, A.; Biran, A. Heritage site management: Motivations and Expectations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 162–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R.; Sundaram, P. Tourism: A sacred journey? The case of ashram tourism, India. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2005, 7, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farber, M.E.; Hall, T.E. Emotion and Environment: Visitors’ Extraordinary Experiences along the Dalton Highway in Alaska. J. Leis. Res. 2007, 39, 248–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reder, L.M.; Donavos, D.K.; Erickson, M.A. Perceptual match effects in direct tests of memory: The role of contextual fan. Mem. Cognit. 2002, 30, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H. The antecedents of memorable tourism experiences: The development of a scale to measure the destination attributes associated with memorable experiences. Tour. Manag. 2014, 44, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, D.; Kruger, J.; Scollon, C.N.; Diener, E. What to Do on Spring Break? The Role of Predicted, On-Line, and Remembered Experience in Future Choice. Psychol. Sci. 2003, 14, 520–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plummer, R. Outdoor Recreation: An Interdisciplinary Perspective; Kendall/Hunt: Dubuque, IA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan Cutler, S.; Carmichael, B.; Doherty, S. The Inca Trail experience: Does the journey matter? Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 45, 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-T. Memorable Tourist Experiences and Place Attachment When Consuming Local Food. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 536–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, P.L.; Lee, U.-I. Developing the Travel Career Approach to Tourist Motivation. J. Travel Res. 2005, 43, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyaupane, G.P.; Morais, D.B.; Graefe, A.R. Nature Tourism Constraints: A Cross-Activity Comparison. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 540–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, C. Sustainable Tourism: Business Development, Operations and Management; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chiou, C.-R.; Huang, M.-Y.; Tsai, W.-L.; Lin, L.-C.; Yu, C.-P. Assessing impact of Natural Disasters on Tourist Arrivals: The Case of Xitou Nature Education Area (XNEA), Taiwan. Int. J. Tour. Sci. 2013, 13, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.P.; Lin, C.M.; Tsai, M.J.; Tsai, Y.C.; Chen, C.Y. Effects of short forest bathing program on autonomic nervous system activity and mood states in middle-aged and elderly individuals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- About the Nature Education Area. Available online: https://www.exfo.ntu.edu.tw/sitou/eng/01about/default.aspx (accessed on 28 May 2019).

- The Experimental Forest, College of Bio-Resources and Agriculture, N.T.U. The Experimental Forest, College of Bio-Resources and Agriculture, National Taiwan University; The Experimental Forest, College of Bio-Resources and Agriculture, National Taiwan University: Nantou County, Taiwan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Blichfeldt, B.S. A nice vacation: Variations in experience aspirations and travel careers. J. Vacat. Mark. 2007, 13, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.N.; Lin, L.C.; Chang, P.C.; Huang, Y.R.; Wang, C.T. Preliminary investigation of visitor arrivals and management implication in Xitou Nature Education Area. J. Exp. For. Natl. Taiwan Univ. 2011, 25, 181–191. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, R.L.; Driver, B.L. Introduction to Outdoor Recreation: Providing and Managing Natural Resource Based Opportunities; Venture Pub.: State College, PA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chandralal, L.; Valenzuela, F.-R. Exploring memorable tourism experiences: Antecedents and behavioural outcomes. J. Econ. Bus. Manag. 2013, 1, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Hussain, K.; Ragavan, N.A. Memorable Customer Experience: Examining the Effects of Customers Experience on Memories and Loyalty in Malaysian Resort Hotels. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 144, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, Y.; Buhalis, D. A model of perceived image, memorable tourism experiences and revisit intention. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 8, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Feng, R. Temporal destination revisit intention: The effects of novelty seeking and satisfaction. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 580–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H. A cross-cultural comparison of memorable tourism experiences of American and Taiwanese college students. Anatolia 2013, 24, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).