Abstract

The advancements in communication and information technologies have substantially enabled the extensive distribution and modification of high-resolution color images. Although this accessibility provides many advantages, it also presents risks related to security. Specifically, when image modification is conducted with malicious intent, exceeding typical artistic or enhancement objectives, it can cause significant moral or economic harm to the image owner. To address this security requirement, this study presents an innovative semi-fragile watermarking algorithm designed specifically for high-resolution color images. The proposed method utilizes Discrete Cosine Transform domain watermarking implemented via Quantization Index Modulation with Dither Modulation. It incorporates several elements, such as convolutional encoding, a denoising convolutional neural network, and a very deep super-resolution neural network. This comprehensive strategy aims to provide ownership verification using a logo watermark, in conjunction with tamper detection and content self-recovery mechanisms. The self-recovery criterion is determined using a thumbnail image, created by downscaling to standard definition and applying JPEG2000 lossy compression. The resultant multifunctional design enhances the overall security of the information. Experimental validation confirms the enhanced imperceptibility, robustness, and capacity of the proposed method. Its efficacy was additionally corroborated through comparative analyses using contemporary state-of-the-art algorithms.

1. Introduction

Currently, advances in communication and information technologies allow for generating, capturing, editing, storing, and sharing high-resolution color images in a massive and immediate manner. In this way, supported by software edition tools integrated into smartphones and personal computers, end users can perform image editing for artistic purposes or image enhancement. However, when image editing is done to alter the content maliciously, such as removing or adding non-existent elements to the original version, and the tampered version is shared, socialized, or transmitted without the image owner’s approval, it can result in moral or economic harm. Conventional informatics security tools cannot solve all information security issues related to tamper detection and ownership authentication of color images. Consequently, the field of data hiding has been extensively studied to embed logos or text within color images, thereby establishing a trustworthy link between the hidden information and the visual content. Within the scope of this paper and the spectrum of data hiding techniques, we identified a method known as digital watermarking, which, in general terms, involves embedding or concealing binary data associated with multimedia ownership to ensure copyright protection and safeguard intellectual property [1,2]. Digital watermarking algorithms typically need to address three fundamental requirements: imperceptibility, robustness, and payload capacity. They are often structured into three stages: embedding, detection or extraction, and watermark generation [3]. The imperceptibility criterion pertains to assessing the visual distortion produced during the embedding stage. Robustness denotes the watermark signal’s resilience to signal processing distortions beyond which recovery or detection becomes unfeasible. The payload denotes the quantity of data bits that can be incorporated during the embedding phase without compromising imperceptibility and robustness [4]. Digital watermarking is classified into different modalities, including fragile, semi-fragile, and robust, each providing a specific performance based on its design and the significance of the aforementioned requirements [5,6,7,8,9]. Fragile watermarking algorithms focus on imperceptibility and payload capacity but generally lack consideration for robustness, whereas robust techniques prioritize robustness but often at the expense of imperceptibility and payload. Conversely, semi-fragile watermarking schemes are explicitly engineered to withstand specified benign image processing operations without compromising the integrity of the watermark. These procedures frequently involve a range of distortions, including both lossy and lossless compression, noise interference, filtering, and file format transformation. Crucially, the essential criteria for imperceptibility (invisibility) and payload (data capacity) maintain the same critical level of importance as those defined for fragile watermarking techniques. Whether the design is fragile, semi-fragile, or robust, within the scope of digital image forgery and tampering, a primary challenge lies in developing a watermarking algorithm that not only effectively detects tampering but also possesses the capability to recover and restore as much of the tampered content as possible. Numerous watermarking methods for forgery and tamper detection have been documented in the scientific literature, categorized as fragile [10,11,12,13,14,15,16], semi-fragile [17,18,19,20,21,22], robust [23,24,25,26,27], and hybrid (robust/fragile) [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. This paper presents a semi-fragile watermarking algorithm for high-resolution color images that uses watermarking in the discrete cosine transform (DCT) domain through quantization index modulation by dither modulation (QIM-DM) [36,37]. This algorithm also incorporates convolutional encoding with Viterbi decoding [38,39], a denoising convolutional neural network (DnCNN) [40,41], and a very-deep super-resolution neural network (VDSR) [42,43], to facilitate ownership authentication via a binary logo watermark. To achieve tamper detection and self-recovery, a thumbnail image is created by rescaling the original color image to a standard VGA resolution [44] and compressing it using the JPEG2000 lossy algorithm [45,46]. By its design, the proposed method can increase the information security capabilities mentioned above by having a multipurpose watermarking algorithm. The results of the tests performed highlight the contribution of the proposed method.

This work’s primary contributions include the following:

- The development of an embedding strategy that maximizes payload capacity while maintaining visual quality and improving resilience against JPEG lossy compression. This approach employs 3 × 3 2D-DCT blocks to encapsulate two bits of data within a pair of designated AC coefficients via QIM-DM.

- The development of a specific criterion for generating thumbnail images that retains both the luminance and color fidelity of the source image. This criterion is based on the VGA standard resolution and utilizes the JPEG2000 lossy algorithm. The process enables us to minimize the payload required while simultaneously allowing for the restoration of the thumbnail image to its original spatial resolution. The DnCNN and VDSR neural network architectures support this approach, which aims to preserve an acceptable level of visual quality.

- Our proposal avoids implementing two separate watermarking algorithms, which is typical of hybrid methods that combine a robust watermarking algorithm with a fragile one to enhance their effectiveness. Instead, the proposed method utilizes a single semi-fragile watermarking technique to achieve ownership authentication, tamper detection, and self-recovery of content. This approach creates a unique watermark derived from the binary data of the logo and the binarization of the thumbnail image.

- The proposal employs convolutional encoding along with the Viterbi decoding algorithm to enhance robustness against cropping, copy–move, copy–paste, compression, filtering, and image noise corruption.

- The application is performed on high-resolution color images.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: Section 2 offers a concise review of pertinent related literature. Section 3 provides a detailed explanation of the proposed methodology. Section 4 includes the experimental results, a discussion of the findings, and a comparative analysis against existing state-of-the-art techniques. Lastly, Section 5 provides the concluding remarks derived from this research.

2. Related Works

Currently, several methods exist for detecting tampering and forgery in digital images. Table 1 provides a brief overview of the most recent and relevant works reported in the literature [17,18,19,21,22,25,27]. We have only included the relevant works in Table 1, as this paper does not aim to be a survey or exhaustive review. Section 4.7 offers an analysis and discussion.

Table 1.

Representative digital watermarking approaches to tamper and forgery detection.

3. Materials and Methods

The primary aim of the proposed semi-fragile watermarking technique is to utilize a thumbnail as a watermark, serving both as a backup for the original content and to illustrate the changes made to the watermarked image in the event of tampering. The localization of any tampered content occurs through two methods: the first involves visual inspection using the recovered thumbnail, which is then validated by the tamper detection mask. The architecture of the proposed scheme is detailed in the subsequent paragraphs. It is fundamentally organized into four sequential stages: watermark generation, embedding, extraction, and content reconstruction.

3.1. Watermark Generation

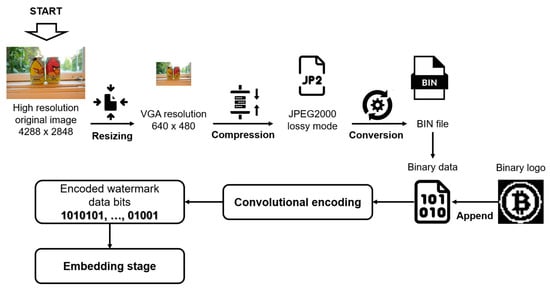

The primary goal of this stage is to develop a robust criterion for generating thumbnail images that effectively retain the essential luminance and color characteristics of the original image content. This section aims to minimize the payload required by the watermarking algorithm as much as possible. The necessary steps are as follows:

Step 1. The original color image I is read, with high spatial resolution of M × N pixels in size, and resized to a VGA (640 × 480) resolution [44]. The resultant image of this step is denoted as IVGA. Resizing to another low resolution reduces the payload, and at the same time, the imperceptibility of the watermarking algorithm is increased. However, applying DnCNN and VSDR severely affects the visual quality of the restored image. On the other hand, resizing to another high-resolution image benefits the visual quality of the restored image after applying DnCNN and VSDR. However, the payload of the watermarking algorithm overflows. The result is a trade-off between the payload and visual quality of the restored image. Based on this behavior and considering the spatial resolution analysis of [47], we decided to adopt the VGA resolution to perform this procedure. Section 4.2.2 illustrate and discuss this behavior.

Step 2. The image IVGA is compressed using the JPEG2000 algorithm in lossy compression mode [45,46]. This algorithm has demonstrated effectiveness recently for watermark payload reduction in data hiding methods, enhancing the protection of color images [48,49]. This approach differs from conventional digital watermarking methods, which typically compress only the image data pixel array. The resulting image from this step is referred to as IJP2. Section 4.2.2 illustrate and discuss the influence of the use of the JPEG2000 algorithm.

Step 3. The file of the image IJP2 is converted to a BIN file format and transformed to a binary string Sb.

Step 4. The binary logo Lb is read with a 32 × 32 pixel size, and the 1024 bits are appended to the beginning of the binary string Sb.

Step 5. For error correction of Sb, we use one of the best-known, non-recursive, and non-systematic convolutional codes over the Galois Field GF(2) with coding rate R given by (1):

where k0 is the length of a window of data bits entering a cycle of the convolutional encoder clock, n0 is the corresponding length of the window at the output in that clock cycle, constraint length K = 5, free distance dfree = 12, with sub-generators written in octal notation: 37, 33, 25. The error-correcting capability t is then

where means the largest integer no greater than . Thus, the code can, with maximum likelihood decoding, correct errors within 3 to 5 constraint lengths; the exact length depends on the error pattern distribution [38,39]. The encoded watermark data bits are denoted as We and are concealed in the frequency domain of the luminance of the color image I via the embedding stage, explained in the following section. Figure 1 shows the procedure mentioned in the above paragraphs.

Figure 1.

Watermark generation procedure.

3.2. Watermark Embedding

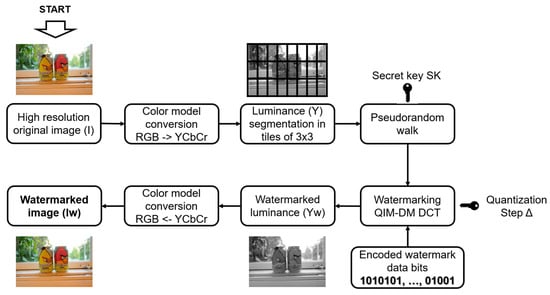

Designing an embedding procedure that maximizes payload preservation while maintaining imperceptibility and ensuring robustness against signal processing distortions presents a challenge in the semi-fragile watermarking research field. The proposed embedding procedure allows for the concealment of the two watermark data bits within 3 × 3 blocks by utilizing quantization index modulation with dither modulation (QIM-DM) [36,37] in the 2D-DCT frequency domain. Figure 2 illustrates the embedding procedure, which is detailed as follows:

Figure 2.

Watermark embedding procedure.

Step 1. Read the original color image I with M × N pixels in size and convert its original RGB to the YCbCr color model. Isolate the luminance information denoted as Y.

Step 2. Segment the luminance Y in blocks of size 3 × 3 pixels.

Step 3. To increase the security of the algorithm, supported by a secret key SK, it generates a pseudorandom walk through all bi blocks. The total number of A blocks required to embed 2 bits of the codified signal We within the color image I is given by (3):

Step 4. Segment We in sequences Sqi, where i = 1, … A, and each one contains 2 data bits. The bidimensional DCT transform is used to process each bi block. Subsequently, each Sqi is embedded into the two alternating current (AC) coefficients of low frequency for each bi in the 2D-DCT domain, utilizing the QIM-DM technique and applying the decision rule (4):

where c is the original and c’ is the watermarked coefficient in the bi block, i = 1, … A, the term z = {1,2}, and Δ denotes the quantization step. The variables dt(z,0) and dt(z,1) denote the dither signals, which are defined by (5) and (6), respectively:

where ps denotes a pseudo-random signal with a uniform distribution generated using a secret key k1, the length of ps corresponds to that of z. Once We is embedded within the DCT coefficients of every bi, the watermarked coefficients are transformed back to the spatial domain using the inverse two-dimensional IDCT, resulting in the watermarked luminance Yw.

Step 5. Using the watermarked luminance Yw and the original chrominances, convert from the YCbCr to the RGB color model to obtain the watermarked color image Iw.

3.3. Watermark Extraction

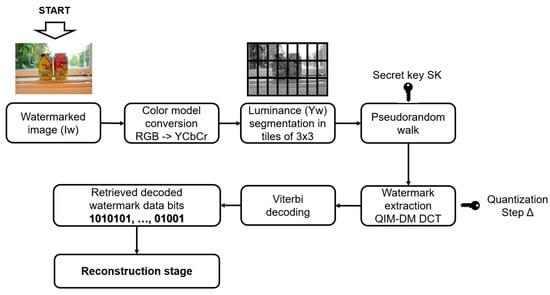

Once the watermarked color image Iw is obtained, extracting the hidden information from its pixels is compulsory to perform ownership authentication, tamper detection, and self-recovery of content. Figure 3 shows the extraction procedure.

Figure 3.

Watermark extraction procedure.

This approach outlines the necessary steps for completing this task:

Step 1. Given the watermarked color image Iw, convert its original RGB to the YCbCr color model. Isolate the watermarked luminance information denoted as Yw.

Step 2. Segment Yw in blocks of size 3 × 3 pixels.

Step 3. The bi blocks, each sized 3 × 3 pixels, are retrieved from Iw utilizing the secret key SK. The encoded data is retrieved from all bi blocks in the 2D-DCT domain via the QIM-DM extraction method specified by (7):

where D1 and D2 represent a pair of distances, z = 1, 2, c’ denotes the watermarked DCT coefficients, and q1 and q2 refer to a pair of quantizers as defined in (8):

where Δ, dt(z,0), dt(z,1), and the secret key k1 have the same values used in the embedding stage. Upon acquiring D1 and D2, the extraction of an encoded watermark data bit is conducted using the decision rule specified in (9):

Iteratively apply this step for each bi in the bidimensional DCT domain, where i = 1, … A, and retrieve the encoded watermark We’.

Step 4. Perform the decoding of We’ using the Viterbi algorithm with a hard decision approach. We employ the Viterbi decoding algorithm [38,39] on the trellis diagram associated with the convolutional code, which has 2K−1 states. This approach involves utilizing the Hamming distance between the received sequence and the retained paths. It is well known that for a binary symmetric channel with crossover probability p < 0.5, selecting the path with the highest log-likelihood function is equivalent to choosing the path that is closest in Hamming distance to the received sequence [38,39].

Once the recovered watermark data bits are decoded Wd, reconstruction of the binary logo and thumbnail image is performed as described in the following procedure.

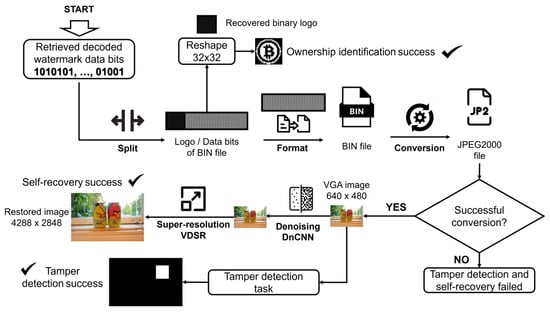

3.4. Reconstruction of Watermark’s Information: Ownership Authentication, Tamper Detection, and Self-Recovery

The reconstruction procedure of the watermark’s information is shown in Figure 4 and explained in the following paragraphs.

Figure 4.

Reconstruction of the watermark’s information procedure.

Step 1. Once the recovered watermark data bits are decoded Wd via the procedure described in Section 3.3, reconstruction of the binary logo is performed to prove the ownership authentication. To recover the binary logo Lb’, extract the first L = 1024 bits from Wd and reshape it to 32 × 32 pixels in size. To measure the robustness, the Bit Correct Rate (BCR) between the original Lb and retrieved Lb’ is computed employing (10):

Step 2. Retrieve the data bits from the location L + 1 to the length of Wd, and format to obtain a BIN file.

Step 3. Convert the BIN file to JPEG2000 image format [45,46]. The resulting image file of this step is denoted as I’JP2-VGA.

Step 4. Since tamper detection and self-recovery are directly dependent on the image file I’JP2-VGA, if this can be opened and read, then the procedure can be continued; otherwise, the procedure is ended, and tamper detection and self-recovery fail.

Step 5. Once the image file I’JP2-VGA is reconstructed, opened, and read, it has a VGA resolution (640 × 480), which is used for the tamper detection task. To perform this, we compute the difference between the luminance of the possible tampered image, rescaled to a VGA resolution denoted as YWT-VGA, and the luminance Y’JP2-VGA extracted from the YCbCr color model of I’JP2-VGA, as follows (11):

where the difference Td is binarized by thresholding and rescaled using nearest neighbor interpolation to a high spatial resolution of M × N pixels in size to get the tampered mask.

Step 6. Once the tamper detection has been performed, the final process is restoring the image file I’JP2-VGA to as high a visual fidelity as possible to the original spatial resolution of M × N pixels in size to view the lost content from the tampered watermarked version with the naked eye. To accomplish this aim, we are supported by two deep learning pretrained models: a denoising convolutional neural network (DnCNN) [40,41] and a very-deep super-resolution neural network (VDSR) [42,43]. Since both models are well-known and established, details of the architecture can refer to [40,41,42,43]. In this way, to diminish the effect of rippling and blocking artifacts caused by the JPEG2000 lossy compression, the model DnCNN is applied to I’JP2-VGA. Finally, the denoised version is rescaled to M × N via the model VDSR, obtaining the restored image I’r.

4. Experimental Results

This section presents the evaluation results of the proposed semi-fragile watermarking algorithm for high-resolution color images.

4.1. Experimental Setup

We consider a set of 1735 high resolution color images extracted from the RAISE dataset [50] in TIFF format with 4288 × 2848 pixels in size and 24 bits/pixel of color bit depth, which includes content of “outdoor,” “indoor,” “landscape,” “nature,” “people,” “objects,” and “buildings.” Some test images are shown in Figure 5. All experiments were conducted on a personal computer equipped with the Microsoft Windows 11 © operating system, an Intel © Core i7 processor, 16 GB RAM, and MATLAB © R2025a (25.1), Windows 64 bits.

Figure 5.

Sample test images used in the experimental results.

4.2. Parameter Settings

4.2.1. Setting the Size of DCT-Blocks and Selecting AC Coefficients

Conventionally, digital image watermarking using the QIM-DM [36,37] technique employs block segmentation of 8 × 8 pixels, aligning with the JPEG image compression standard. This method typically embeds four watermark data bits into the AC coefficients corresponding to low to middle frequencies in the DCT domain, achieving a balance between imperceptibility and robustness. To meet the objectives of this study, however, it is essential to maximize capacity without compromising other watermarking requirements, which necessitates reducing the block segmentation size. In this context, considering a high-resolution color image with dimensions of 4288 × 2848 pixels, Table 2 presents the total capacity offered when a) the block segmentation is 8 × 8 pixels, embedding four watermark data bits per DCT block, and b) the block segmentation is 3 × 3 pixels, embedding two watermark data bits per DCT block. The total amount of encoded watermark data bits, denoted as We, is derived from the procedure outlined in Section 3.1, Watermark Generation, incorporating the following features: resizing the image from 4288 × 2848 to 640 × 480, applying JPEG2000 lossy compression with a ratio of 1:10, and employing convolutional encoding as described in Section 3.1.

Table 2.

Setting of size of DCT blocks.

As shown in Table 2, various combinations exist to adjust capacity by modifying block segmentation and the number of bits concealed per block. The choice of the appropriate pair of values depends on the objectives of the watermarking algorithm’s design. To maintain a balance between imperceptibility and robustness, we opt for 3 × 3 block segmentation and conceal two bits per block. Consequently, we enhance the capacity of the proposed method by using a 3 × 3 segmentation and embedding two bits, instead of the conventional settings of 8 × 8 and four bits [36,37].

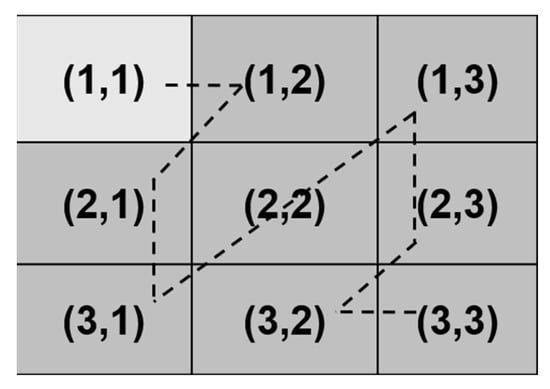

Once the values for block segmentation and the amount of data to be embedded in the DCT domain are established, the next step is to select two AC coefficients from the 3 × 3 DCT block for the embedding procedure. To accomplish this, we utilize a zig-zag scan, as illustrated in Figure 6, which represents a truncated version of the traditional zig-zag scan.

Figure 6.

Zig-zag scanning utilized in the DCT domain.

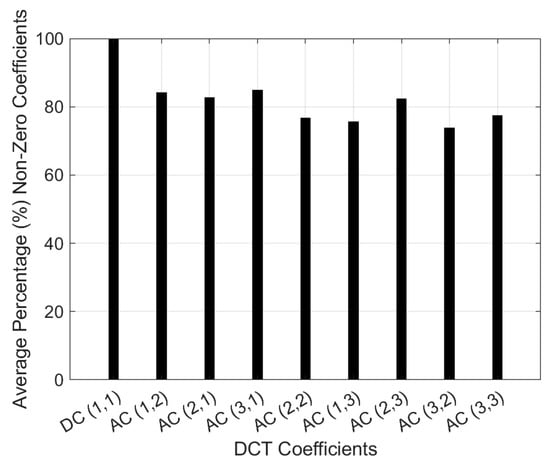

Experimentally, we applied JPEG lossy compression with a quality factor of 70 and utilized 3 × 3 block segmentation in the DCT domain. We then compressed all images in the dataset and calculated the average percentage of non-zero direct current (DC) and AC coefficients, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Average percentage of non-zero coefficients obtained for all images in the dataset.

The analysis in Figure 7 indicates that the optimal candidates for embedding watermark data bits, excluding the DC coefficient, are the coefficients with the highest average percentages. AC (1, 2) and AC (3, 1) have values of 84.11% and 84.92%, respectively. While these AC coefficients fall within the low-frequency band, alterations to lower frequencies can lead to visual distortions. However, by appropriately adjusting the quantization step (Δ) during the embedding process, it is possible to minimize distortions in the image content while simultaneously enhancing robustness against various signal processing distortions.

4.2.2. Setting of Image Resolution and JPEG2000 Compression Ratio to Thumbnail Image Design

To determine the optimal image resolution and JPEG2000 compression ratio for generating the thumbnail image, we conduct the following experimental tests. First, we consider the procedure outlined in Section 3.1, Watermark Generation, along with image resolutions of HD (1280 × 720), VGA (640 × 480), and CIF (352 × 288). We also examine a JPEG2000 compression ratio of 1:10, the self-reconstruction procedure described in Section 3.4, and the Weighted Peak Signal to Noise Ratio (WPSNR) [51], as given in (12):

where NVF is the Noise Visibility Function given by (13):

σx2(x,y) is the local variance in a window of width wh [51]. Table 3 shows the results of the first experiment to select the proper image resolution to build the thumbnail image.

Table 3.

Setting of optimal image resolution for thumbnail image design.

The analysis presented in Table 3 indicates that HD resolution yields a high WPSR value following the reconstruction procedure outlined in Section 4.4. However, the total amount of encoded watermark data bits (We) exceeds the total capacity of the proposed method. Conversely, CIF resolution demonstrates a contrasting behavior compared to HD resolution, resulting in a lower amount of We data bits but a decrease in visual quality as measured by WPSNR. The experimental results show that VGA resolution strikes an appropriate balance between the number of We data bits and visual quality in terms of WPSNR after the reconstruction procedure described in Section 3.4. Consequently, based on these findings, we have selected VGA resolution for our semi-fragile watermarking design.

The second experiment examines the procedure outlined in Section 3.1, Watermark generation. It uses a fixed image resolution of VGA and evaluates JPEG2000 compression ratios of 1:5, 1:10, and 1:15. Additionally, it incorporates the self-reconstruction procedure described in Section 3.4 and utilizes the WPSNR metric. The results of this experiment are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Setting of optimal JPEG2000 compression ratio for thumbnail image design.

From Table 4, we observe that the three JPEG2000 compression ratios of 1:5, 1:10, and 1:15 provide advantages by reducing the total amount of encoded data bits (We), while maintaining WPSNR values close to 34 dB. However, selecting a compression ratio of 1:5 is not optimal, as the total amount of encoded watermark data bits (We) exceeds the capacity of the proposed method. In contrast, the ratios of 1:10 and 1:15 yield an appropriate total amount of We, with a minor WPSNR difference of 0.3178 dB between them. Although this WPSNR difference may seem negligible, our experimental results indicate that as the JPEG2000 compression ratio increases, the resulting images show perceptual distortions in the edges and flat regions due to a blurring effect. Therefore, we have chosen the JPEG2000 compression ratio of 1:10 for the proposed method to achieve the highest possible visual quality in the reconstructed image derived from the thumbnail version.

4.2.3. Set of Quantization Step Δ

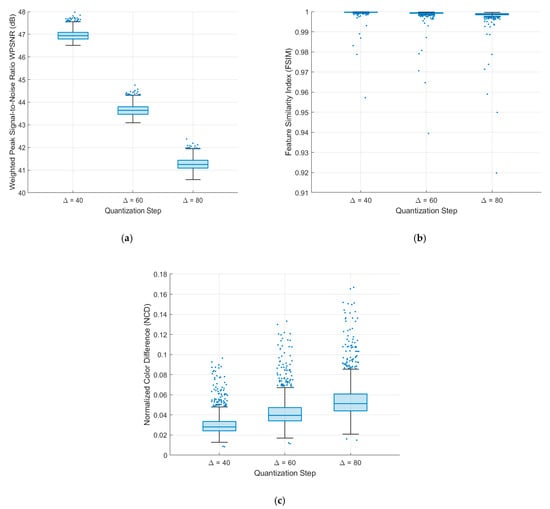

To determine the appropriate quantization step ∆ used in QIM-DM [36,37] within the 2D-DCT frequency domain, we examine the parameter settings detailed in Section 4.2.1 and Section 4.2.2. We will also consider a variable range for ∆, specifically from 40 to 80.

This test evaluates how the quantization step ∆ affects the imperceptibility requirement by analyzing the watermarked color image Iw. It computes the visual distortion using the WPSNR metric specified in (13) and assesses visual quality through the Feature Similarity Index Method (FSIM) [52], which ranges from 0 to 1, where an FSIM value of 1 signifies that the original and reference images are identical, and values closer to 0 indicate poor visual quality. Additionally, it measures color differences using the Normalized Color Difference (NCD) [53], where an NCD value of 0 denotes that the original and reference images are the same, and values further from 0 indicate significant color differences. For brevity, readers can refer to [52,53] for the mathematical definitions of FSIM and NCD, respectively. Figure 8 illustrates the experimental results regarding WPSNR, FSIM, and NCD for quantization step ∆ values of 40, 60, and 80 across each trial. Table 5 presents the results of these experiments, detailing the median value, quartiles, whiskers, and the number of outliers, which facilitates a comprehensive analysis of the results shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

(a) WPSNR, (b) FSIM, and (c) NCD values for quantization steps ∆ 40, 60, and 80, obtained in all images in the dataset.

Table 5.

Median values, quartiles, whiskers, and the number of outliers for WPSNR, FSIM, and NCD metrics to a variable quantization step ∆, obtained in all images in the dataset.

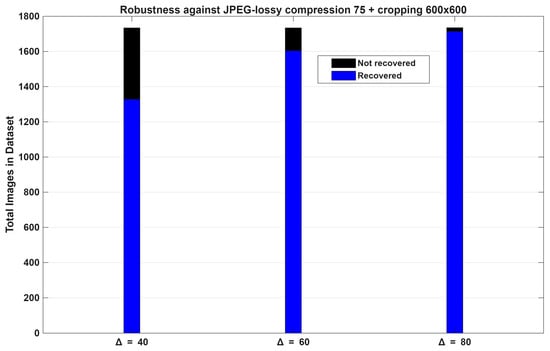

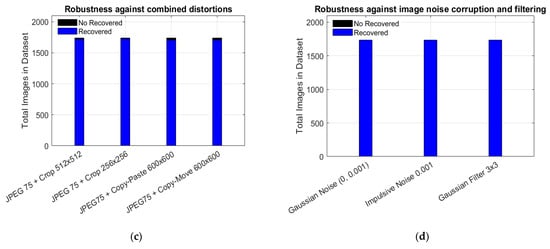

In Table 5 and Figure 8, we observe that visual distortion, visual quality, and color changes decrease as the quantization step ∆ increases. A higher value of ∆ enhances the robustness of the encoded watermark; however, we find that imperceptibility is compromised. This illustrates a trade-off between robustness and imperceptibility. To determine the appropriate quantization step ∆, we conducted an additional experiment measuring robustness against a rigorous attack, specifically JPEG lossy compression at a quality factor of 75 combined with random cropping of 600 × 600 pixels. This attack was applied to all watermarked color images in the dataset. The results are presented in Figure 9, which considers quantization step ∆ values of 40, 60, and 80 for each trial.

Figure 9.

Robustness results of thumbnail recovery capability against aggressive combined distortion.

In Figure 9, we show that a high value of ∆ increases the robustness of the encoded watermark (We); however, as shown in Table 5 and Figure 8, the imperceptibility is diminished. As stated above, the result is a trade-off between the robustness and imperceptibility requirements. From Figure 9, for ∆ = 40, the proposed scheme can correctly recover the thumbnail image of 1328 color images, while 407 thumbnails cannot be recovered. For ∆ = 60, 1605 thumbnails were recovered correctly, and 130 could not be recovered. Finally, for ∆ = 80, 1715 thumbnails were recovered correctly, and 20 could not be recovered. After this analysis, we determine that ∆ = 60 is a suitable value for the quantization step of the proposed watermarking algorithm, preserving as much as possible a proper balance between imperceptibility and robustness.

Table 6 shows the final values of all parameters that compose the proposed semi-fragile watermarking algorithm for high-resolution color images.

Table 6.

Final values of all parameters of the proposed method.

4.3. Imperceptibility Analysis

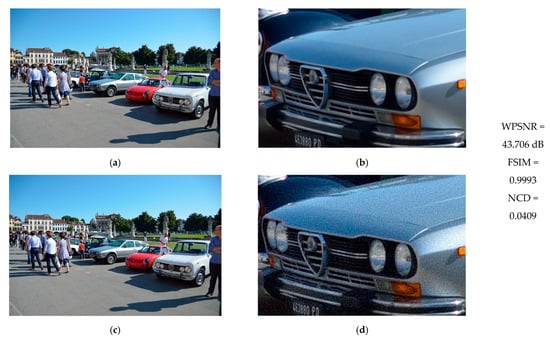

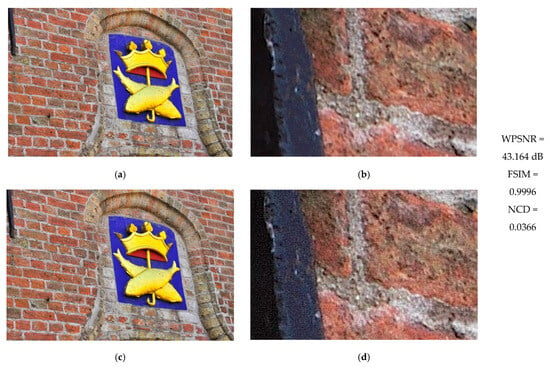

To evaluate the imperceptibility of the watermark provided by the proposed method, Figure 10 and Figure 11 present two test images: the first featuring weak textures and the second showcasing strong textures. These images are used to assess visual quality alongside their respective results in terms of WPSNR, FSIM, and NCD. Typically, electronic devices like laptops display high-resolution image previews based on a predetermined percentage, enabling users to zoom in on specific areas using available software options. Accordingly, Figure 10 and Figure 11 also include a 300% zoom of a small region from both the original and watermarked images, facilitating an evaluation of the degree of visual distortion caused by the proposed method.

Figure 10.

(a) Original image with weak textures. (b) Zoom at 300% of a small portion of the content of (a). (c) Watermarked image. (d) Zoom at 300% of a small portion of the content of (c). WPSNR, FSIM, and NCD results are in the last column.

Figure 11.

(a) Original image with strong textures. (b) Zoom at 300% of a small portion of the content of (a). (c) Watermarked image. (d) Zoom at 300% of a small portion of the content of (c). WPSNR, FSIM, and NCD results are in the last column.

As demonstrated in Figure 10a,c and Figure 11a,c, the watermark remains imperceptible under predefined viewing conditions on electronic devices such as laptops or smartphones, as confirmed by the WPSNR, FSIM, and NCD results. Conversely, Figure 10 and Figure 11d illustrate the visual degradation that occurs when the image is zoomed in to 300% or more. This test is intended for illustrative purposes only, given that it is uncommon to zoom in beyond 100% on digital images displayed on devices like laptops, tablets, or smartphones.

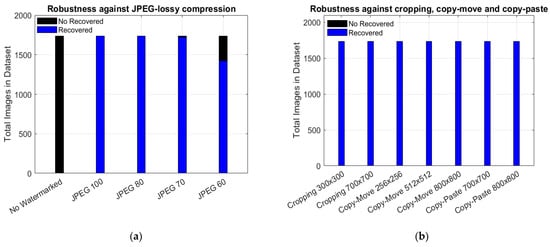

4.4. Robustness Analysis

To evaluate the robustness of the proposed method, we divide this test into two categories. The first category evaluates the robustness of the proposed semi-fragile watermarking algorithm in terms of its ability to recover the image thumbnail when the watermarked image is distorted by several image processing operations. The second one considers the capability to recover the binary logo after the watermarked image is attacked by a set of signal processing operations. Thus, Figure 12 illustrates the performance of the proposed algorithm regarding its robustness and its ability to recover the image thumbnail. In this sense, for non-watermarked images, no thumbnail has been recovered, confirming the non-ambiguity of the proposed method. Table 7 complements the results presented in Figure 12 for the rest of the distortions, with detailed purposes.

Figure 12.

Robustness against: (a) Unwatermarked and JPEG lossy compression, (b) Cropping, copy–move and copy–paste, (c) combined distortions and, (d) image noise corruption and filtering.

Table 7.

Number of thumbnail images recovered and not recovered when watermarked images are distorted by several image processing operations.

The proposal, which is a semi-fragile watermarking scheme, is illustrated in Figure 12 and Table 7. It demonstrates that thumbnail images can be recovered in nearly all attack scenarios; however, performance declines when the watermarked image undergoes JPEG 60 compression. These experimental results indicate that increasing the tolerance for each attack reduces the robustness of the proposed fragile watermarking algorithm. Additionally, it is important to note that the encoded watermark data bits, referred to as We, contain information from the entire JPEG2000 file that includes the thumbnail image, which makes recovery sensitive to any alterations.

On the other hand, Table 8 demonstrates the robustness of the proposed method, specifically in terms of the BCR defined previously in Equation (11). This metric evaluates the method’s ability to recover the binary logo Lb, which has a pixel size of 32 × 32. The average BCR for images that are not watermarked is 0.4994. In the other attack scenarios, Lb remains visible to the unaided eye and is nearly fully recoverable.

Table 8.

BCR of the recovered binary logo Lb when watermarked images are distorted by several image processing operations.

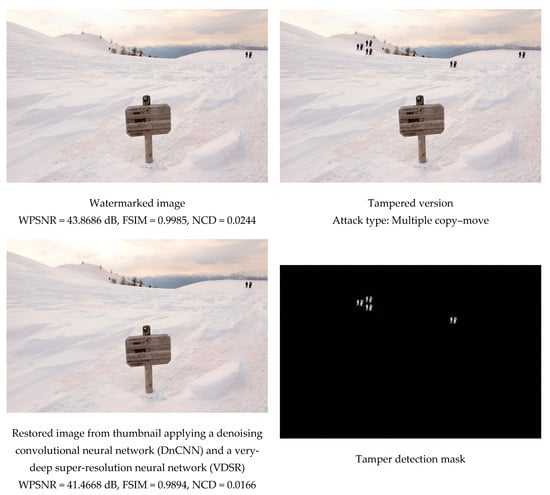

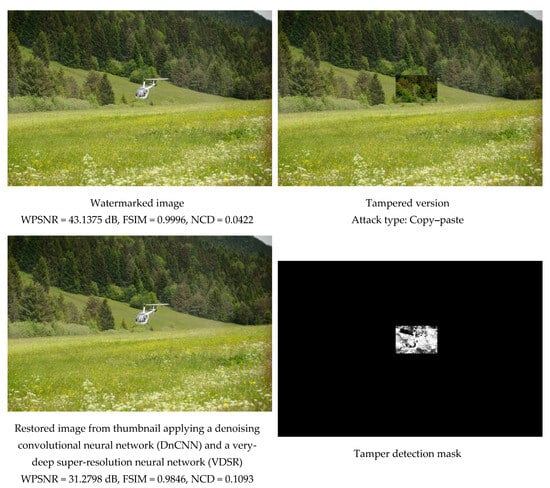

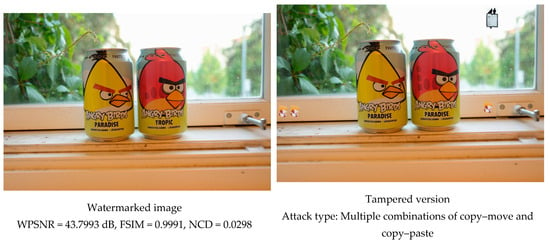

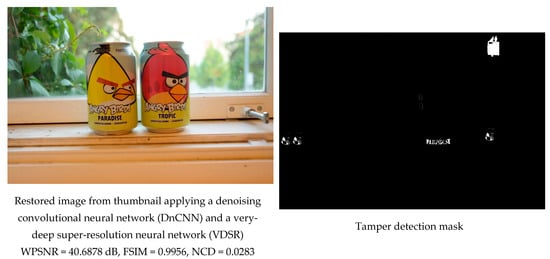

4.5. Self-Recovery and Tamper Detection Analysis

The goal of this experiment is to visualize the performance of the proposed semi-fragile watermarking technique concerning self-recovery and tamper detection. For brevity, Figure 13, Figure 14 and Figure 15 present the experimental results when the watermarked image undergoes manipulation through multiple copy–moves, extensive copy–pasting, and various combinations of both techniques. It is important to note that the color images used have a resolution of 4288 × 2848 pixels and a color bit depth of 24 bits per pixel. Based on the experimental findings, we would like to emphasize several key aspects of our proposal: (a) The proposed method extends beyond simply generating a tamper detection mask. (b) It possesses self-recovery capabilities that include color information, maintaining the original spatial and bit depth resolutions. (c) The visual quality of the restored color image is preserved to the greatest extent possible, as indicated by the WPSNR, FSIM, and NCD metrics. These metrics demonstrate the advantages of employing a denoising convolutional neural network (DnCNN) and a very deep super-resolution neural network (VDSR). Although Figure 13, Figure 14 and Figure 15 indicate that the tamper detection mask exhibits low precision, the primary aim of this work is to identify tampered regions, even with low accuracy. The mask serves primarily for illustrative purposes and as an additional feature. The restored color image allows the naked eye to discern the forgery content, which is a notable highlight of the proposed method.

Figure 13.

Self-recovery and tamper detection performance against multiple copy–move.

Figure 14.

Self-recovery and tamper detection performance against multiple copy–paste.

Figure 15.

Self-recovery and tamper detection performance against multiple combinations of copy–move and copy–paste.

4.6. Security Analysis

The proposed semi-fragile watermarking algorithm consists of several components necessary for extracting all data bits required to recover and restore the thumbnail image. Key elements include the frequency domain used to embed the watermark, the size of the DCT blocks, the modulated AC coefficients, and the configuration of the convolutional encoder. The secret key (SK) enhances the security of the method by facilitating a pseudorandom walk through all bi blocks, where i = 1, … A. Thus, the total number of A blocks needed to embed two bits of the codified signal We within the color image I is indicated by Equation (3), as described in Section 3.2. The size of A varies depending on the image. For instance, if the minimum value of A in the dataset is approximately 995,000 and the maximum is approximately 1,103,000, there exists a difference of 108,000 options for the size of A, assuming the total number of DCT blocks for a 4288 × 2848 image resolution is 1,356,121. Given that the seed SK for generating each pseudorandom walk sequence falls within the range of [0, 232 − 1], [54], there are numerous possible combinations () to estimate the correct sequence to the pseudorandom walk. Additionally, it is important to note that even if an adversary estimates SK, all the aforementioned configuration parameters must be known and properly configured to successfully recover and reconstruct the thumbnail image.

4.7. Performance Comparison

Table 9 presents a performance comparison that includes both the previously reported works in the state-of-the-art from [17,18,19,21,22,25,27] as well as our proposed method. This compendium was considered because it is the most relevant to our proposed semi-fragile watermarking algorithm. Then, the development of a homologated comparative analysis may facilitate a fair and equitable comparison. Thus, the comparison is constructed solely based on common criteria evaluated in a semi-fragile manner. When a criterion is not applicable, the designation “N/A” is assigned. Subsequently, we conduct a precise comparison based on Table 9. Obtaining an equitable comparison is difficult since, to the best of our knowledge, and according to an exhaustive literature review, we found that few methods of semi-fragile watermarking applied to color imaging; the majority focus their efforts on grayscale images with small spatial resolution. If there are several approaches to forgery and tamper detection designed as fragile [10,11,12,13,14,15,16], robust [23,24,25,26,27], and hybrid (robust/fragile) [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35], in some cases, their aims are different from those of our proposal. In this way, a comparison with fragile algorithms [10,11,12,13,14,15,16] is not suitable by convention due to their absence of robustness against the image processing distortions investigated in this proposal. Conversely, a comparison with hybrid methods (robust/fragile) [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35] is not appropriate because these works primarily aim to enhance the robustness of ownership authentication, while tamper detection and self-recovery are still handled by a fragile method. Comparatively, the robust modality [23,24,25,26,27] is unsuitable in terms of capabilities and design criteria when contrasting robust and semi-fragile watermarking modalities. However, we consider the related works reported in [25,27] because they focus on color images and are among the closest to our proposed method. From Table 8, we demonstrate that the proposals in [17,18,21] exhibit robustness against various signal processing distortions and possess the capability to detect alterations and recover lost content; however, these works are limited to grayscale images with a small spatial resolution of 512 × 512. The study in [19] is applicable to color images and shows robustness against a broad range of image processing distortions, including combined attacks; however, it primarily focuses on tamper detection with high accuracy. The works in [22,25] may align closely with our objectives and surpass our proposed method regarding robustness against common signal processing distortions; however, our proposal excels over [22] in its application to high-resolution color imaging, featuring color images relevant to real scenarios. Additionally, we outperform [25] in self-recovery, as [25] can only restore a halftone version of the luminance information, while our proposal recovers color images at the same resolution as the original. Finally, comparing our method with that of [27] indicates that our proposed method demonstrates greater robustness; furthermore, the method in [27] is restricted to RGBA images in Portable Network Graphics (PNG) format.

Table 9.

Performance comparison.

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

In this paper, we propose a semi-fragile watermarking scheme for high-resolution color images. This scheme enhances conventional watermarking techniques, specifically the Quantization Index Modulation with Distortion Minimization (QIM-DM) in the Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT) domain, by improving payload capacity while maintaining a balance between imperceptibility and robustness. Our approach, in conjunction with the efficient JPEG2000 image compression algorithm, convolutional encoding, and supported by the DnCNN and VDSR neural networks, results in an effective multipurpose watermarking method. Tamper and forgery detection, along with recovery capabilities, present significant challenges in the field of digital image forensics and related areas. It is crucial to design algorithms that facilitate the recovery of forged content in real-world scenarios, and testing should extend beyond datasets with low spatial resolution. Additionally, assessing imperceptibility should involve metrics that reflect human visual system behavior, such as WPSNR and FISM, rather than relying solely on traditional PSNR and SSIM metrics. We evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed method by comparing its performance against existing state-of-the-art techniques. Our proposal preserves the original format and color resolution of the image dataset utilized. Future work will aim to further enhance the capacity, imperceptibility, and robustness achieved thus far, with a focus on significantly higher spatial resolutions and the development of a hybrid solution that combines both active and passive methodologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.-H., A.C.-H. and J.C.S.-G.; methodology, M.C.-H. and A.C.-H.; software, M.C.-H. and A.C.-H.; validation, M.C.-H., A.C.-H., J.C.S.-G. and F.J.G.-U.; formal analysis, J.C.S.-G. and F.J.G.-U.; investigation, M.C.-H., A.C.-H. and F.J.G.-U.; resources, M.C.-H., F.J.G.-U. and J.C.S.-G.; data curation, M.C.-H.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.-H.; writing—review and editing, A.C.-H., J.C.S.-G. and F.J.G.-U.; visualization, J.C.S.-G. and F.J.G.-U.; supervision, F.J.G.-U.; project administration, M.C.-H. and A.C.-H.; funding acquisition, M.C.-H., J.C.S.-G. and F.J.G.-U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Instituto Politecnico Nacional (IPN), the Tecnologico de Monterrey, the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de México (UNAM), and the Secretaria de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnologia e Innovacion (SECIHTI) for their support during this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Barni, M.; Bartolini, F. Applications. In Watermarking Systems Engineering: Enabling Digital Assets Security and Other Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bas, P.; Furon, T.; Cayre, F.; Doërr, G.; Mathon, B. A quick tour of watermarking techniques. In Watermarking Security Fundamentals, Secure Design and Attacks; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, I.J.; Miller, M.L.; Bloom, J.A.; Fridrich, J.; Kalker, T. Digital Watermarking and Steganography, 2nd ed; Morgan Kaufmann Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.; Kumar, S. Robust digital watermarking techniques for protecting copyright applied to digital data: A survey. Turk. J. Comput. Math. Educ. 2021, 12, 3819–3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chennamma, H.R.; Madhushree, B. A comprehensive survey on image authentication for tamper detection with localization. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 1873–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhushree, B.; Basanth Kumar, H.B.; Chennamma, H.R. An exhaustive review of authentication, tamper detection with localization and recovery techniques for medical images. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 39779–39821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Thing, V.L. A survey on image tampering and its detection in real-world photos. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2019, 58, 380–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melman, A.; Evsutin, O. Methods for countering attacks on image watermarking schemes: Overview. J. Vis. Commun. Image 2024, 99, 104073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, D.; Tiwari, A.; Khare, P.; Srivastava, V.K. A comprehensive review on optimization-based image watermarking techniques for copyright protection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 242, 122830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminuddin, A.; Ernawan, F. AuSR1: Authentication and self-recovery using a new image inpainting technique with LSB shifting in fragile image watermarking. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 2022, 34, 5822–5840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeroual, A.; Afdel, K. Real-time image tamper localization based on fragile watermarking and Faber-Schauder wavelet. AEU-Int. J. Electron. Commun. 2017, 79, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adi, P.W.; Sugiharto, A.; Hakim, M.M.; Setiadi, D.R.I.M.; Winarno, E. Efficient fragile watermarking for image tampering detection using adaptive matrix on chaotic sequencing. Intell. Syst. Appl. 2025, 26, 200530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalerao, S.; Ansari, I.A.; Kumar, A. A secure image watermarking for tamper detection and localization. J. Ambient Intell. Hum. Comput. 2021, 12, 1057–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouarroudj, R.; Souami, F.; Bellala, F.Z.; Zerrouki, N.; Harrou, F.; Sun, Y. Secure and reversible fragile watermarking for accurate authentication and tamper localization in medical images. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2025, 123, 110072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Singh, S.K.; Udmale, S.S. An efficient self-embedding fragile watermarking scheme for image authentication with two chances for recovery capability. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 1045–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, K.; Gao, T. A novel color image tampering detection and self-recovery based on fragile watermarking. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2023, 78, 103619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivasubramanian, N.; Konganathan, G. A novel semi fragile watermarking technique for tamper detection and recovery using IWT and DCT. Computing 2020, 102, 1365–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benrhouma, O. Cryptanalysis and improvement of a semi-fragile watermarking technique for tamper detection and recovery. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 22149–22174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, J.; Huang, J.; Wen, X.; Shao, Z. A semi-fragile watermarking tamper localization method based on QDFT and multi-view fusion. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 15113–15141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanammal, V.; Rajalakshmi, S.; Remya, V.; Ranjith, S. ViTU-net: A hybrid deep learning model with patch-based LSB approach for medical image watermarking and authentication using a hybrid metaheuristic algorithm. Comput. Biol. Med. 2025, 194, 110393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrullah, A.; Ernawan, F.; Raffei, A.F.M.; Chuin, L.S. TDSF: Two-phase tamper detection in semi-fragile watermarking using two-level integer wavelet transform. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2025, 61, 101909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, S.P.; Kandala, R.N.V.P.S.; Chandra Mouli, P.V.S.S.R.; Zaini, H.G.; Jaffar, A.; Paramasivam, P.; Ghoneim, S.S.M. A robust fragile watermarking approach for image tampering detection and restoration utilizing hybrid transforms. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahaoglu, G.; Ustubioglu, B.; Ulutas, G.; Ulutas, M.; Nabiyev, V.V. Robust Copy-Move Forgery Detection Technique Against Image Degradation and Geometric Distortion Attacks. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2023, 131, 2919–2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Q.; Hu, X.; Zhang, X.; Qian, Z.; Li, S.; Zhang, X. RWN: Robust Watermarking Network for Image Cropping Localization. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Bordeaux, France, 16–19 October 2022; pp. 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arevalo-Ancona, R.E.; Cedillo-Hernandez, M. Robust zero-watermarking based on dual branch neural network for ownership authentication, auxiliary information delivery and tamper detection. Egypt. Inform. J. 2025, 30, 100650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Rodriguez, A.E.; Arevalo-Ancona, R.E.; Perez-Meana, H.; Cedillo-Hernandez, M.; Nakano-Miyatake, M. AISMSNet: Advanced Image Splicing Manipulation Identification Based on Siamese Networks. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-W. A distortion-free authentication method for color images with tampering localization and self-recovery. Signal Process. Image Commun. 2024, 124, 117116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yue, Y. Security Analysis and Improvement of Dual Watermarking Framework for Multimedia Privacy Protection and Content Authentication. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Otum, H.M.; Ellubani, A.A.A. Secure and effective color image tampering detection and self restoration using a dual watermarking approach. Optik 2022, 262, 169280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laishram, D.; Manglem Singh, K. A watermarking scheme for source authentication, ownership identification, tamper detection and restoration for color medical images. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 23815–23875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, P.; Jana, B.; Bhaumik, J. An Image Authentication and Tampered Detection Scheme Exploiting Local Binary Pattern Along with Hamming Error Correcting Code. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2021, 121, 939–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Zou, J.J.; Fang, G. A Novel Multipurpose Watermarking Scheme Capable of Protecting and Authenticating Images with Tamper Detection and Localisation Abilities. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 85677–85700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinhal, R.; Ansari, I.A. Multipurpose Image Watermarking: Ownership Check, Tamper Detection and Self-recovery. Circuits Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 41, 3199–3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bei, Y.-L.; Zhu, X.-R.; Zhang, Q.; Qiao, S. A Robust Image Watermarking Algorithm Based on Content Authentication and Intelligent Optimization. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Control and Computer Vision (ICCCV 2022), New York, NY, USA, 19–21 August 2022; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Yuan, X. Robust and fragile watermarking for medical imaging. In Proceedings of the Sixteenth International Conference on Signal Processing Systems (ICSPS 2024), Kunming, China, 15–17 November 2024; SPIE: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; p. 135595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Wornell, G.W. Quantization index modulation: A class of provably good method for digital watermarking and information embedding. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theor. 2001, 47, 1423–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedillo-Hernandez, M.; Cedillo-Hernandez, A.; Nakano-Miyatake, M.; Perez-Meana, H. Improving the management of medical imaging by using robust and secure dual watermarking. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2020, 56, 101695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odenwalder, J.P. Optimal Decoding of Convolutional Codes. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Viterbi, A. Error bounds for convolutional codes and an asymptotically optimum decoding algorithm. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1967, 13, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zuo, W.; Chen, Y.; Meng, D.; Zhang, L. Beyond a Gaussian Denoiser: Residual Learning of Deep CNN for Image Denoising. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2017, 26, 3142–3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubinger, M.; Clough, P.; Müller, H.; Deselaers, T. The IAPR TC-12 Benchmark: A New Evaluation Resource for Visual Information Systems. In Proceedings of the OntoImage 2006 Language Resources for Content-Based Image Retrieval, Genoa, Italy, 22 May 2006; Volume 5, p. 10. Available online: http://www.lrec-conf.org/proceedings/lrec2006/workshops/W02/RealFinalOntoImage2006-2.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Kim, J.; Lee, J.K.; Lee, K.M. Accurate Image Super-Resolution Using Very Deep Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 1646–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Delving Deep into Rectifiers: Surpassing Human-Level Performance on ImageNet Classification. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Santiago, Chile, 13–16 December 2015; pp. 1026–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Board, C.A. IEEE Standard for Camera Phone Image Quality. In IEEE Stdandard 1858-2016 (Incorporating IEEE Stdandard 1858-2016/Cor. 1-2017); IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taubman, D.S.; Marcellin, M.W. JPEG2000: Standard for interactive imaging. Proc. IEEE 2002, 90, 1336–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taubman, D.S.; Marcellin, M.W. Image Compression Fundamentals, Standards and Practice. In The Springer International Series in Engineering and Computer Science; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-0-7923-7519-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, R.C.; Woods, R.E. Digital Image Processing, 4th ed.; Pearson Education: New York, NY, USA, 2018; p. 1022p. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Q.; Xiang, S. Invertible Color-to-Grayscale Conversion Using Lossy Compression and High-Capacity Data Hiding. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2022, 32, 7373–7385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragoso-Navarro, E.; Garcia-Ugalde, F.; Cedillo-Hernandez, M. Improved protection for colour images via invertible colour-to-grey, image distortion, and visible-imperceptible watermarking. IET Image Process. 2024, 18, 3854–3863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang-Nguyen, D.-T.; Pasquini, C.; Conotter, V.; Boato, G. RAISE—A Raw Images Dataset for Digital Image Forensics; ACM Multimedia Systems; MMSys ’15. In Proceedings of the 6th ACM Multimedia Systems Conference, Portland, OR, USA, 18–20 March 2015; pp. 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldovanu, S.; Michis, F.A.; Moraru, L. An invisible DWT watermarking algorithm using noise removal with application to dermoscopic images. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1730, 012010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sara, U.; Akter, M.; Uddin, M.S. Image Quality Assessment through FSIM, SSIM, MSE and PSNR—A Comparative Study. J. Comput. Commun. 2019, 7, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.-A.; Chen, H.H. Stochastic Color Interpolation for Digital Cameras. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2007, 17, 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Control Random Number Generator, Matlab Help Center. Available online: https://mathworks.com/help/matlab/ref/rng.html (accessed on 17 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.