Abstract

This paper proposes a novel methodology, based on machine learning and statistical models, for predicting hurricane-related losses to specific assets. Our approach uses three critical storm parameters typically tracked by meteorological agencies: maximum wind speed, minimum sea level pressure, and radius of maximum wind. The system categorizes potential damage events into three insurance-relevant classes: non-payable, partially payable, and fully payable. Three triggers for final payouts were designed: hybrid framework, standalone regression, and standalone non-linear regression. The hybrid framework combines two classification models and a non-linear regression model in an ensemble specifically designed to minimize the absolute differences between predicted and actual payouts (Total Absolute Error or TAE), addressing highly imbalanced and partially compensable events. Although this complex approach may not be suitable for all current contracts due to limited interpretability, it provides an approximate lower bound for the minimization of the absolute error. The standalone non-linear regression model is structurally simpler, yet it likewise offers limited transparency. This hybrid framework is not intended for direct deployment in parametric insurance contracts, but rather serves as a benchmarking and research tool to quantify the achievable reduction in basis risk under highly imbalanced conditions. The standalone linear regression provides an interpretable linear regression model optimized for feature selection and interaction terms, enabling direct deployment in parametric insurance contracts while maintaining transparency. These three approaches allow analysis of the trade-off between model complexity, predictive performance, and interpretability. The three approaches are compared using comprehensive hurricane simulation data from an industry-standard catastrophe model. The methodology is particularly valuable for parametric insurance applications, where rapid assessment and claims settlement are essential.

1. Introduction

Natural disasters pose significant risks to infrastructure, economies, and human lives [1]. Hurricanes are among the most devastating natural disasters, causing extensive damage through high winds, heavy rainfall, and storm surges after landfall, often leading to flooding, landslides, and infrastructure failures [2,3]. The financial consequences can be catastrophic and long-lasting, affecting both local communities and broader economic systems. Insurance services play a critical role in managing these financial risks by transferring potential losses to insurers. Among available risk transfer tools, parametric solutions have grown from limited use in the late 1990s to widespread global adoption [4,5]. These innovative products automatically trigger payouts based on predefined objective parameters, offering advantages over traditional indemnity insurance in terms of recovery speed, product design, and transaction costs [6,7,8]. Their importance has increased alongside the growing frequency and intensity of hurricanes, driven by natural climate variations and longer-term trends [9,10,11], creating a greater need for robust parametric triggers. Parametric solutions have become particularly important in catastrophe bonds (CAT bonds), a type of insurance-linked security that transfers catastrophic risk to capital markets [12]. These instruments allow insurers to manage financial exposure while offering investors attractive opportunities. When triggering events occur, bond payments cover insurer losses, providing crucial post-disaster liquidity [13].

However, the speed advantage of parametric solutions comes with basis risk, i.e., the potential mismatch between actual losses and parametric payouts [14,15,16,17]. This study addresses the need for more accurate loss predictions to reduce basis risk. Traditional methods relying on historical data and statistical models often fail to capture the complex dynamics of hurricanes, limited by data availability and modeling assumptions. Machine learning techniques can overcome these limitations by analyzing large datasets to identify non-obvious patterns. We propose a novel approach using machine learning to predict hurricane-induced financial impacts on specific assets like cities or facilities. Our methodology analyzes three key physical parameters monitored in near real-time by public agencies: maximum wind speed (MWS), minimum sea level pressure (MSLP), and radius of maximum wind (RMW). The insurance sector faces the structural challenge of uncertainty, especially with low-frequency, high-impact risks such as hurricanes. Basis risk, inherent in parametric products, is a concrete manifestation of the gap between actual losses and the indemnities estimated by the model. Our proposal seeks to reduce this uncertainty through a hybrid approach, while also recognizing the need for explicit communication and management of residual risk that remains in any predictive model [18,19]. The main contributions of this paper are described next. Firstly, we use a high-fidelity catastrophe model containing thousands of years of simulated hurricane activities and associated losses, providing a rich dataset that captures complex, non-linear relationships between storm parameters and asset damage. Secondly, we employ advanced data processing techniques to merge and enhance fragmented datasets, including the derivation of informative statistical features for machine learning models. Thirdly, we develop a two-track hybrid modeling framework that combines classification models to categorize events (non-payable, partially payable, or fully payable) with regression models to predict precise payouts for partially payable cases. The hybrid framework integrates two classification models and a non-linear regression model in an ensemble designed to approximate the lower bound of the TAE, maximizing predictive performance even for highly imbalanced events. The standalone non-linear regression models likewise offer limited transparency but are structurally simpler. The standalone linear regression model provides a fully transparent trigger optimized for feature selection and interaction terms, enabling direct deployment in parametric insurance contracts and offering clear interpretability. Finally, we perform a comprehensive experimental evaluation using industry-standard catastrophe model data and a synthetic dataset, comparing multiple classification and regression algorithms and highlighting the trade-off between prediction accuracy, model complexity, and model interpretability.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related work on machine learning applications in parametric insurance. Section 3 details our proposed framework, which includes an advanced hybrid model and standalone non-linear models. Section 4 demonstrates its application to a hotel in Kingston, Jamaica. Section 5 performs a SHAP analysis of the results. Section 6 compares our framework against an alternative linear model that offers greater interpretability (a property often requested by policy takers). Section 7 tests the previous approaches over a synthetic and publicly available dataset. Finally, Section 8 presents conclusions and future research directions.

2. The Imbalance Problem in Parametric Risk Transfer

Parametric insurance has been widely used in natural disaster risk management due to its advantages of fast claims settlement and reduced moral hazard, making it a promising alternative for natural event damage liability [20,21,22]. Many studies have explored approaches to designing effective parametric triggers for natural disasters, including hurricanes and earthquakes [8,14,23,24,25,26]. The United States Geological Survey and the Inter-American Development Bank have developed parametric triggers for contingency credit instruments that correlate earthquake magnitude, intensity, and population exposure with payments [27]. Calvet et al. [12] reviewed statistical and machine learning techniques for designing earthquake-triggered bond payments, while Chang and Feng [28] proposed a bond pricing model based on hurricane parameters.

Cat-in-a-box and cat-in-a-grid triggers are common for tropical cyclone risk transfer. Cat-in-a-grid solutions, which use multiple geographic domains, show potential for reducing basis risk compared to cat-in-a-box alternatives [8]. These solutions offer transparency and explainability: they use publicly available data and typically employ polynomial functions that are easily deployable in contracts. This aligns with the broader trend of enhancing parametric products through data-driven methods and catastrophe models.

In machine learning-based claim prediction, gradient boosting decision trees (GBDT) usually outperform traditional methods like generalized linear models [29,30]. GBDT algorithms capture non-linear relationships and complex variable interactions, making them valuable for risk management [30]. Implementations such as XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost provide powerful tools for actuarial tasks while maintaining computational efficiency [31,32]. These algorithms are particularly suited to hurricanes, given their unpredictable nature and variable impacts [33], and can improve loss prediction accuracy for parametric insurance.

A major challenge in designing parametric triggers is extreme class imbalance [34]. Catastrophic events with payouts are rare, often with return periods of decades or centuries. Accurate prediction of these events is critical since they directly determine insurance payouts. Resampling techniques, including under-sampling and over-sampling methods, have proven effective [35,36,37]. These methods adjust the target variable distribution to emphasize rare but critical cases. Approaches range from randomized sampling to criteria-based methods [38]. Synthetic data generation, such as SMOGN (combining undersampling with SmoteR and Gaussian noise oversampling), has also shown success [39]. Such strategies are widely applied in high-stakes domains like rare disease prediction and financial risk modeling [38]. Additional techniques modify the training process itself, such as specialized regression tree splitting criteria for rare events [40] and density-based sample weighting [41]. This paper makes use of these methods to improve hurricane risk transfer solutions.

Despite growing interest in machine learning and parametric insurance for natural catastrophe loss prediction, existing studies mainly rely on limited historical datasets and focus primarily on regional rather than single-asset loss modeling, where extreme class imbalance is particularly pronounced. Moreover, few frameworks effectively integrate multi-class classification of payment categories (non-payable, partial, full) with precise loss quantification, a crucial need for practical parametric insurance applications. This paper addresses these gaps by proposing a hybrid machine learning framework combining advanced classification and regression methods applied to high-fidelity catastrophe simulation data spanning thousands of years. Our approach improves prediction accuracy across payout categories while maintaining computational efficiency and robustness, thus providing a scalable and higher-accuracy solution that advances state-of-the-art parametric risk transfer modeling.

3. Framework General Overview

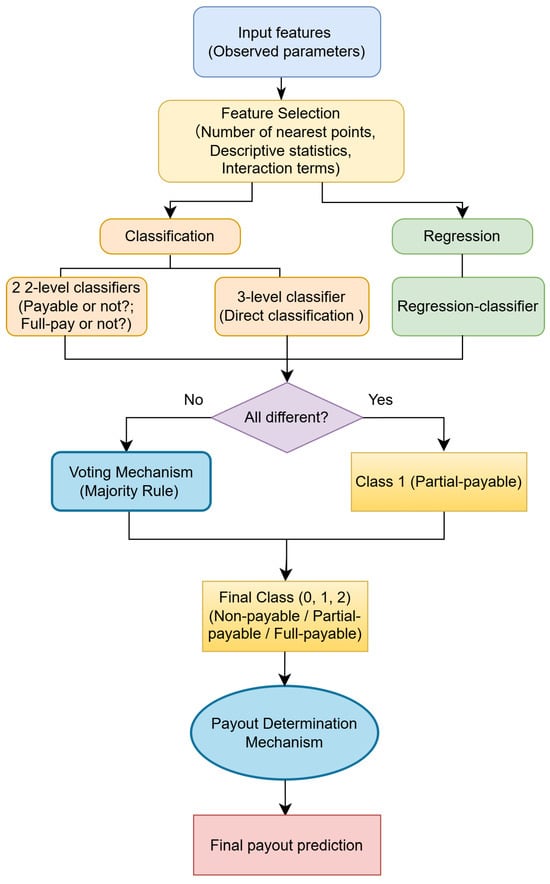

In order to address the extreme imbalance in the dataset and to predict catastrophe insurance payouts accurately, we propose a hybrid strategy. This framework implements two parallel modeling tracks that integrate classifiers and a regression model through an ensemble mechanism, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the proposed general framework.

The process begins with feature selection applied to input features consisting of physical observed parameters and geographical locations for simulated hurricane events across multiple timestamps (Section 4.1). These features are processed through the following two parallel tracks:

- Classification track, comprising three models: (i) one three-class classifier (non-payable , partially payable , fully payable ); and (ii) two binary classifiers (payout requirement determination and, if so, full-pay versus partial-pay assessment).

- Regression track: a regression model trained to predict losses, primarily focusing on partially payable events; its predictions also configure a tertiary classifier that categorizes outputs into classes 0, 1 or 2 based on payment bounds.

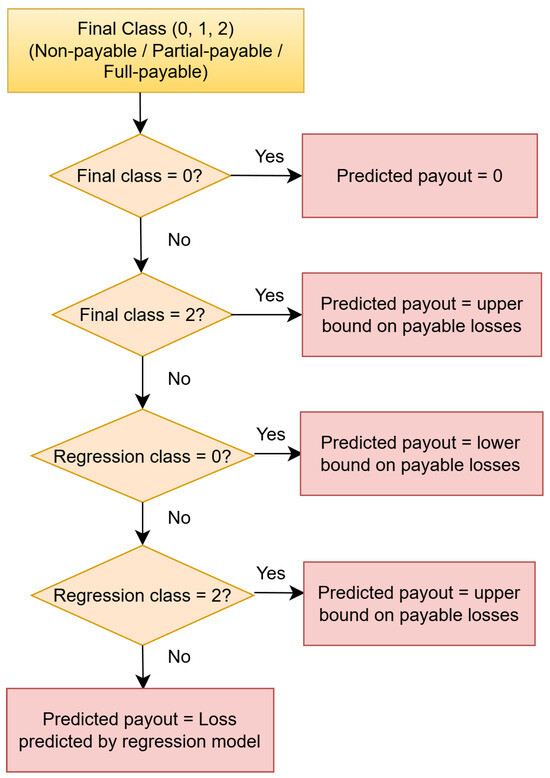

Detailed model specifications are provided in Section 4.3 and Section 4.4. The final event classification is determined by majority voting among the three classification models (the two classifiers and the regression model used as a classifier in combination with the payment bounds). Cases where all models disagree are classified as class 1 (partial payment). The payout determination mechanism shown in Figure 2 determines the final payout prediction.

Figure 2.

Payout determination mechanism for final prediction of payout.

Following standard insurance practice, the policy defines two critical thresholds for loss compensation: (i) a lower bound (), also known as the attachment level, which represents the minimum loss amount that triggers any policy payout (i.e., losses below are classified as non-payable or class 0); and (ii) an upper bound (), also called the exhaustion level, which is the maximum compensable amount (i.e., losses exceeding receive this maximum value since they belong to class 2, while intermediate losses between and are partially payable or class 1). Then, the predicted payout is formally defined as

where denotes the predicted class after voting and represents the regression-predicted loss. This integrated approach utilizes each model’s strengths: classifiers ensure accurate categorization, while the regression model provides precise loss estimates for critical events. All predictions remain within meaningful business thresholds, enhancing both interpretability and practical relevance.

4. Application to Tropical Cyclone Parametric Risk Transfer

The methodology introduced in Section 3 is general and can be applied to different assets, regions and perils, as long as the results of an underlying catastrophe model are made available. In this section we apply it to tropical cyclone parametric risk transfer for a hotel in Kingston, Jamaica.

4.1. Underlying Catastrophe Model and Description of the Problem

The proposed methodology relies on the results of the Risk Engineering + Development (RED) hurricane model for the Caribbean and its associated exposure database (www.redrisk.com). The loss computation module within the catastrophe model computes the losses that could be caused by both winds and storm surges at specific exposures. The stochastic catalog of hurricanes contains thousands of years of stochastic hurricane activity. Each hurricane track is associated with a variable number of observation points at 6 h time steps, logging the corresponding physical parameters or measures of the hurricane, such as the specific location of the cyclone eye, its MWS, MSLP and RMW. More details on the RED model can be found in [8].

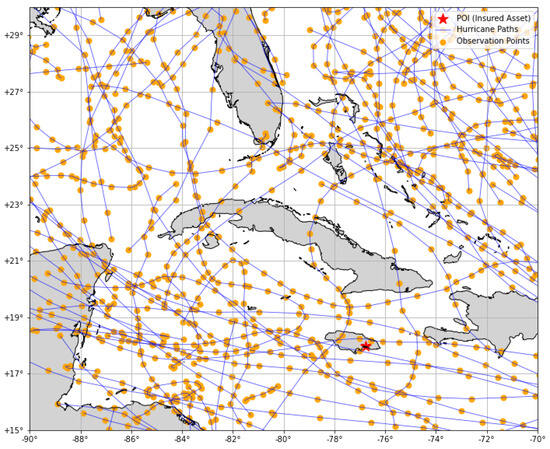

To define the parametric model, a single specific insured asset is considered. The location of the insured assets is designated with a star on the map in Figure 3 and overlaid with a sample set of hurricane paths simulated with the catastrophe risk model. These synthetic events have estimated losses associated with the considered exposure as well as physical parameters for multiple observations along the path over time. The dots in the figure represent observational points of the hurricanes at different times, with a time step of 6 h. Thus, each hurricane shown in the figure is associated with a data pair containing information on the losses of the insured asset caused by the hurricane and its physical parameters. These include, at each observation point, the longitude and latitude of the eye of the cyclone, its MWS in kt units, its MSLP in mbar units, and its RMW in km units.

Figure 3.

Map showing the insured asset and a sample set of simulated hurricane paths.

The payout y is defined in the context of a classical insurance policy, based on the loss l caused by the event, as follows:

The policy is only liable for losses above the lower bound (or attachment level) of payable losses, while losses above the upper bound (or exhaustion level) would disburse a payout limited by the policy limit of liability, reached at the exhaustion level.

As anticipated in Section 2, this type of prediction problem is inherently complex and imbalanced. Events were categorized into non-payable, partially payable, and fully payable by the determination of the stated lower and upper bounds of payable losses. As insurance policies typically target catastrophic, rare events, the majority of the stochastic events result in no payout, while a small subset leads to partial or full compensation. Thus, it is critical to correctly categorize the payout type of events as well as to accurately predict the numerical losses for partially payable events. Our approach combines classification and regression models within a hybrid track to address this imbalance, aiming to minimize the gap between predicted and actual payouts for each specific event. Table 1 summarizes the distribution of three payout classes for all events. The very clear imbalanced distribution is reflected in the fact that only of the events reach a compensable loss.

Table 1.

Distribution of payout categories under all events.

4.2. Feature Selection: Pre-Processing with Data Analytics

Algorithm 1 begins by initializing parameters, setting the number of closest observations, and enabling or disabling descriptive statistics and geodesic distance calculations. It then prints the settings. Next, it defines the point of interest (POI) with specific coordinates and sets the lower and upper bounds on the losses that can be insured, thus also determining the basic information of a specific insurance policy.

| Algorithm 1 Processing and Analysis of Event Losses. |

|

Using Python 3.12.3, it loads a CSV file containing loss data for each event with real losses and computes new columns for the payout type. Ordinal encoding of the three categories according to the stated lower and upper bounds, i.e., 0 for events where the loss of the event does not reach the lower bound of payable losses (USD 15,000); 1 for events where the loss of the event reaches the lower bound of payable losses, but does not reach the upper bound (USD 115,000); and 2 for events where the loss of the event exceeds the upper bound of payable losses, but can be paid out only at the upper bound amount. Then, a function is defined to compute and return the counts and percentages of non-payable, partially payable, and fully payable events. Table 2 presents the distribution of loss-producing events.

Table 2.

Distribution of payout categories under events with modeled losses.

The algorithm proceeds then to load and process a stochastic catalog from another CSV file, computing distances (Euclidean and optionally geodesic) and sorting the events by code and distance to the POI. Unnecessary columns are dropped. The computation of descriptive statistics for each of the observational parameters (distance, MWS, MSLP, and RMW) for each event is based on all available observation points, including count, mean, standard deviation, median, minimum, maximum, first quartile, and third quartile of each indicator corresponding to the event. These results are later decided to be merged into a data frame as needed for model training since these contain information of all observational points. According to the subsequent model training described in Section 4.3 and Section 4.4, the algorithm keeps only the specified number of closest observations for each event as the basic and necessary features. The catalog was performed with the same event row-to-column transformation so that each row represents a unique event with physical parameters information from each observation. Some events come in and dissipate fast, lacking a specific number of observations near to the POI. Differences in the duration of each hurricanes imply the number of observations varies and thus generates NaNs after transformation. To maintain feature consistency across all events, missing values in distances were imputed by forward-filling the last observed value and multiplying it by two, assuming that the hurricane had moved further away from the POI. Other physical parameters, including MWS, RMW and MSLP, were forward-filled to reflect persistence in physical conditions. Using this simple but physically motivated approximation to simulate continued storm movement after the last observation. If chosen, descriptive statistics on each event are merged with the basic features consisting of parameters of a specific number of closest observed points. Finally, the algorithm merges the processed event data with the loss data on event codes and fills NaN values in the losses with zero.

4.3. First Modeling Track: Classification Models

The goal of this track is to train models that classify all events as precisely as possible. As explained before, two classification methods were implemented on this dataset. One consists of two two-level classifiers that first decide whether the event needs to be paid or not and, in the former case, decide whether the event needs to be fully paid using the upper bound value. Another approach is to build a three-level classifier that directly categorizes events into the three payout types. Algorithm 2 begins by setting several initial parameters, including the number of closest observations to consider, whether to use feature importance, the maximum number of important features, and whether to add interaction terms. Next, it loads a dataset from a CSV file and analyzes the distribution of different event categories, such as non-payable, partially payable, and fully payable events. For feature importance, an XGBRegressor model is trained on the training data. If the flag for using feature importance is enabled, only the important features are selected for training. If interaction terms are enabled, the algorithm adds ‘distance-parameter’ interaction features by weighting each physical parameter of the n closest observations by the inverse of their distance to the insured asset, thereby capturing the joint effect of storm parameters and spatial proximity. The dataset is then split into features (inputs) and targets (outputs). The data is further divided into training, validation, and testing sets, which are used to train the model, tune hyperparameters, and report final performance, respectively. Notice that this test set remains strictly held out throughout the entire study, with no exposure during training, validation, or model selection in any track. The algorithm calculates the absolute frequency and relative frequency of each class in both the training&validation set and test set, then combines these frequencies into a summary for analysis. Table 3 shows this summary, where the overall training and validation sets and the test set are evenly split across different categories.

| Algorithm 2 Classification Analysis. |

|

Table 3.

Splitting of the dataset.

For the classification model, both approaches follow similar steps. The data is converted into a format suitable for the XGBoost (2.1.3) algorithm. The algorithm sets the parameters for the XGBoost model, specifying that it is a binary classification problem with two classes or a multi-class classification problem with three classes. To mitigate class imbalance, XGBoost’s built-in weighting mechanism was set to the ratio of majority (class 0) and minority (class 1 and 2). This re-weights the loss function such that errors on the minority class have a proportionally higher impact during training. Early stopping is performed to determine the optimal number of boosting rounds, and the final model is trained using this optimal number. If feature importance is enabled, the algorithm retrieves and plots the feature importance scores from the trained model. The trained model is then used to make predictions on the testing set. The algorithm evaluates the models’ performance using various metrics and computes confusion matrices to visualize the classification results. It should be noted that both classification methods are based on the specific initial set of features here. Specifically, the number of recent observations is specified as 15, without activating the only use of important features and the addition of interaction terms. The classification results of the trained classifiers are reported on the same test set.

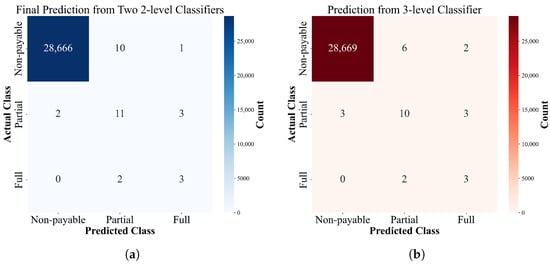

Table 4 shows the performance of the trained two two-level classifiers and three-level classifier on the same dataset, respectively. Both methods are better at classifying ‘non-payable’ events than at ‘partially payable’ and ‘fully payable’ events. In terms of F1-score, the way of training two two-level classifiers and then summarizing the results is slightly better for ‘partially payable’ events, while training a three-level classifier directly is slightly better for ‘fully payable’ events. However, in terms of recall of ‘partially payable’ and ‘fully payable’ events, two two-level classifiers detects ‘partially payable’ events relatively well.

Table 4.

Performance comparison of 2-level and 3-level classifiers.

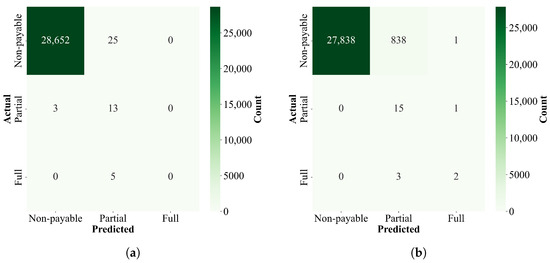

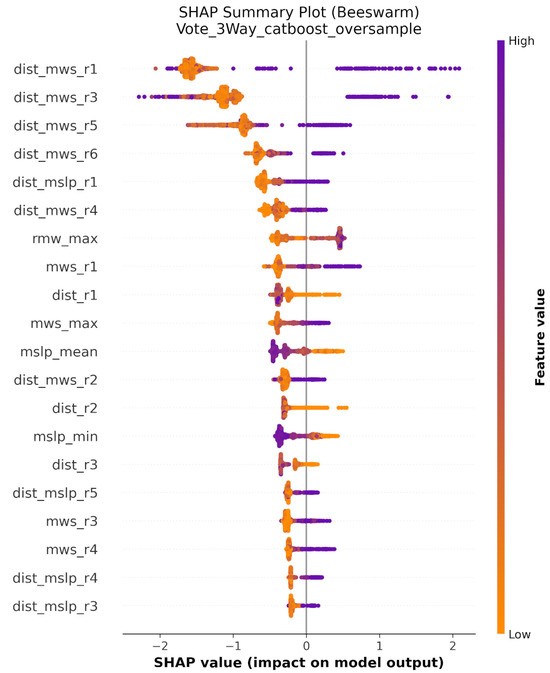

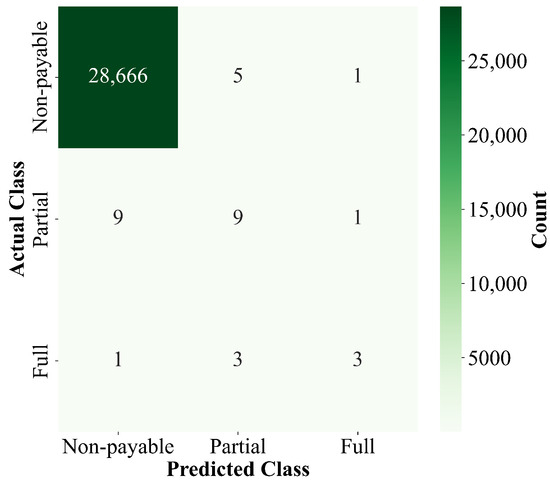

Figure 4 shows the performance on each class through their respective confusion matrices. It is interesting to note that the direct three-class classifier yields fewer misclassifications on ’non-payable’ events, yet it tends to make the more significant mistake of misclassifying ’non-payable’ events as ’fully payable’.

Figure 4.

Comparison of confusion matrices for the two classification approaches. (a) Confusion matrix for two 2-level classifiers on the test dataset. (b) Confusion matrix for 3-level classifier on the test dataset.

For the predictions given by the two classification methods, Table 5 demonstrates the agreement between the classification results of the two classification methods. There was 99.96% agreement on the results, while predictions differed on very few events. According to the description in Section 3, these non-agreement events will have waited to vote on the final classification along with the 3rd classifier defined based on the values predicted by the regression model and the lower and upper bounds.

Table 5.

Summary of classifier agreement results.

4.4. Second Modeling Track: Regression Algorithms

The goal of this track is to train the model to predict the events that cause actual losses as accurately as possible, so that its predicted payments do not deviate too much from the amount that should be paid. Algorithm 3 starts by setting several initial parameters, including the lower and upper bounds for losses, the number of closest observations to consider, and various flags for adding interaction features, removing rows with zero or extreme losses, and using feature importance. Next, the dataset is loaded from a CSV file, and the algorithm checks for any missing values. If the flag for adding interactions is enabled, interaction terms are added to the dataset for each distance-parameter combination. The algorithm then filters the data for regression analysis. It computes descriptive statistics for the total losses and, if specified, removes rows with zero or extreme losses. The regression track adheres to the same strict data partition established in Section 4.3, and the held-out test set remains frozen to wait for reporting the final results of hybrid models on it at the end. Another dataset that contains other events is further divided into training and validation sets. Horizontal box-plots are created to visualize the distribution of the training and validation sets.

| Algorithm 3 Regression Analysis and Models Ensemble. |

|

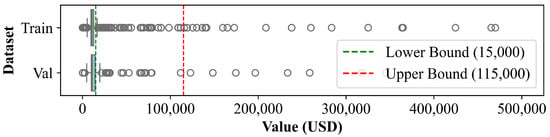

To prevent a large number of zeros from interfering with model training, events with zero losses were removed from the training set for the regression model. For feature selection, two types of feature selection are implemented separately: using the first 15 nearest observations or using the first 6 nearest observations and the descriptive statistics of each physical parameter among all observations. It is worth noting that the addition of the interaction term is also enabled here, extending the input features of the regression model. Figure 5 shows the box plots of the original training and validation sets filtered for the regression model with the stated lower bound and upper bound as reference lines. Events that are payable (i.e., reach the lower losses bound for payout) are essentially identified as outliers.

Figure 5.

Boxplots of original train and validation datasets for regression.

To address the challenge of highly imbalanced data distribution, some pre-processing approaches mentioned in Section 2 were implemented to systematically reduce the number of common cases or augment the rare samples (where the original output target is larger than the specific lower bound for payable losses) for the training set. In particular, random undersampling [42,43], random oversampling [44,45], and SMOGN, which stands for the combined method based on undersampling, oversampling and introduction of noise [39], were implemented. Unlike non-heuristic random undersampling and oversampling for classification tasks, random undersampling and oversampling for regression require user-defined thresholds to identify the most common or less important observations for the values of the target variables [38]. Here all samples that have losses below the lower bound of compensability (class 0) are considered the most common. Table 6 presents the distribution of the most common and rare significant cases for the original training set and after processing by these three methods. For SMOGN, due to the variation in the feature space affecting the similarity measure between the samples; thus, the post-processing distributions are slightly different under different feature choices.

Table 6.

Comparison of class distributions under different sampling strategies.

Various gradient boosting decision tree models (GBDTs), such as XGBoost (2.1.3), LightGBM (4.6.0), and CatBoost (1.2.8), are initialized as well as trained on the enhanced training data. A weight adjustment policy was also employed during model training. Aligns with the general principle of weighted machine learning as discussed in [41,46], where more important but rare samples are emphasized by modifying the model’s cost function.

After the models were trained, the three GBDTs can be used individually or in an ensemble with their median for prediction. The performance of each prediction way was reported on the validation set. Following the concept of basis risk, the total error is defined as the sum of the absolute differences between the predicted payout (adjusting the predicted loss to the predicted payout based on the predefined lower and upper bounds) and the actual payment (adjusting the actual loss according to the stated lower and upper bounds). Table 7 summarizes the best performance on the validation set and the corresponding model or prediction method of the models trained by the three pre-processing methods under the two types of feature choices, where ‘best performance’ means that the minimum TAE is achieved for the prediction of the actual class 1.

Table 7.

Summarize the ‘best performance’ of each model.

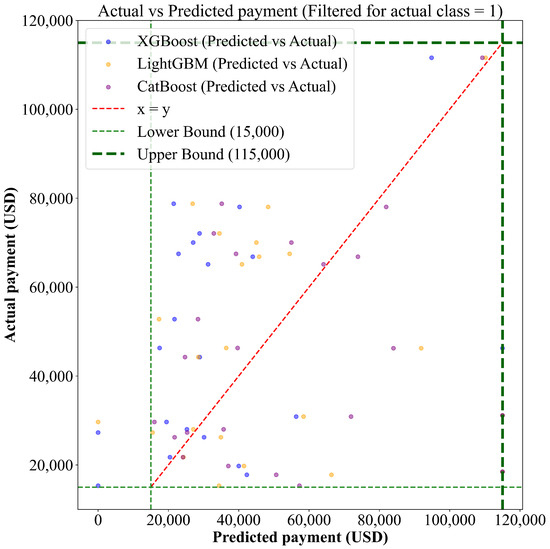

The total error in the validation set is smallest when the pre-processing is simple random oversampling and the model is trained with CatBoost, especially when the feature selection is the parameter information of the 6 nearest observational points and descriptive statistics of all observations for each parameter and interaction term. The scatter plots in Figure 6 visualize the actual payment versus predicted payout from the different regression models for the events with the category of partial payment, i.e., the actual class equals 1, under this kind of pre-processing and feature selection. The purple points are the prediction performance of the best CatBoost-trained model.

Figure 6.

Scatter plot of predicted vs. actual payment for actual partial payment events on the validation set.

4.5. Models Ensemble and Final Prediction

The final prediction results are reported on the entire original test set used for the classification model in Section 4.3, containing those with zero loss for a total of 28,698 events. Since Section 4.4 shows that the CatBoost model trained with specific feature selection and simple random oversampling pre-processing performed best on key payout events (partially payable). This model was used to predict the entire test set and classify all events based on the stated lower and upper limits of the payouts to report the generalizability of the overall prediction model.

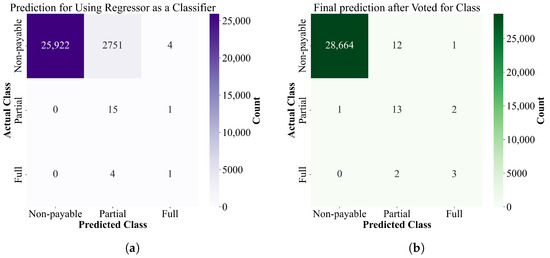

Figure 7a illustrates the performance of the regression model as a classifier. It is interesting to note that for ‘partially payable’ events, the recall of the regression as a classifier is 1, which is significantly higher than the two classifiers dedicated to event classification. The classifications predicted by the regression model are aggregated with the classifications predicted by the two previous classifiers and voted on. The one with the highest number of votes was taken as the final class. As provided in Section 3, if an extreme case occurs where the three classifiers give completely different classifications, the final class will be the intermediate class, i.e., class 1, ‘partially payable’ event. Even though this did not happen in the whole test set here, the possibility cannot be ruled out. Figure 7b shows the performance of the voted classifiers. Compared to the two specialized classifiers in Section 4.3, the recognition of ‘partially payable’ is significantly improved.

Figure 7.

Confusion matrices for single regressor and the voted final prediction. (a) Confusion matrix for using regression as a classifier on the test dataset. (b) Confusion matrix for the final classification using the votes of the three classifiers.

In the end, following the mechanism of model ensembles set in Section 3, the final payment amount was predicted on the basis of the final classification after the vote and numerical predictions of a regression model. If the agreed class is 0, i.e., ‘non-payable’, the final payout is 0; if the agreed class is 2, i.e., ‘fully payable’, the final payout is the upper bound of the payable loss. The rest are considered as class 1, i.e., ‘partially payable’, and the regression as a classifier is also classified as 1; the predicted payout is the loss predicted by the best regression model referred to in Section 4.4. In other cases (including cases with different classifications for each of the three classifications), if the regression is classified as 0, then the final payout amount is the lower bound of the payable loss. If the regression classification is 2, the final payment amount is the upper bound of the payable loss.

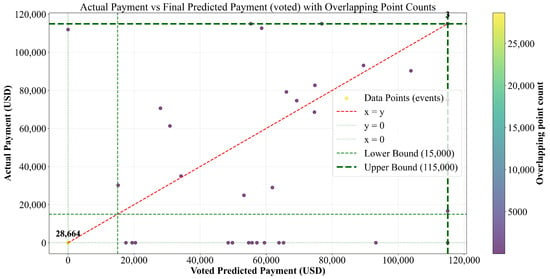

The final predicted payment can be compared to the actual payout adjusted by the lower and upper bounds of the actual loss. Figure 8 visually illustrates the final prediction performance on the whole test set. The color of the dots close to light yellow means that they overlap a lot; specific numbers have been marked above the corresponding points. Out of test events, except for a few large deviations, the overall predictions were in good agreement with the actual values.

Figure 8.

Scatter plot of final predicted vs. actual payment on the whole training set.

Table 8 also records some performance metrics calculated from the final predictions.

Table 8.

Performance metrics of final prediction.

For validation purposes, the method was tested against a linear regression baseline model (see Section 6) and against a CatBoost regression that was improved through both the oversampling technique and the parameter settings. It required careful tuning of the best single regression method to obtain close results to the hybrid framework results. Still, the method proposed in this paper outperforms them when looking at both the test set reported metrics and the k-fold cross-validation with five folds. The hybrid framework method is also much more robust in terms of classification performance. Both CatBoost models were kept because they show different strengths in the classification task. CatBoost 2 learned to classify all three classes correctly, while CatBoost 1, even though it got better overall error metrics, could only identify Class 0 and Class 1.

As shown from the results in Figure 9 the CatBoost configurations also show important differences between the two methods. The CatBoost 1 uses a Tweedie loss function with a variance power of 1.5, which is designed for insurance data that often has many zero values and some very large values. This loss function helps the model handle the skewed distribution of insurance claims. The CatBoost 1 version runs for 1000 iterations with a learning rate of 0.05 and a tree depth of 5. In contrast, the CatBoost 2 uses the RMSE loss function, which is a simpler approach that minimizes the squared differences between predictions and actual values. The CatBoost 2 version only runs for 100 iterations, which is ten times fewer than the standard version. Both versions use the same learning rate of 0.05 and depth of 5, so these parameters stay constant across the two approaches. The shorter training time in the custom version makes it faster to train, but the standard version with more iterations may capture more complex patterns in the data because it has more time to learn.

Figure 9.

Confusion matrices for two standalone CatBoost regressors on the test dataset. (a) Confusion matrix for using standalone CatBoost1 as a classifier. (b) Confusion matrix for using standalone CatBoost2 as a classifier.

Both CatBoost-based methods keep the actual loss values unchanged during oversampling. They only copy complete rows of data, including all features and the target loss amount. The difference between them is that the CatBoost 2 method has a stricter limit on how many copies it makes, while the CatBoost 1 method allows more copies but still maintains a reasonable upper bound. The CatBoost 2 method may stop at 500 total Class 1 examples, while the CatBoost 1 method could go higher if the data allows it without exceeding the 20x duplication limit per example. The changes in the CatBoost method also affected how the training sample was selected. Both CatBoost methods were trained on a careful selection that includes the same quantity of true zero losses and non-zero small losses together from Class 0. Then the method tries to balance the combined sum of Class 1 and Class 2 samples so they match as closely as possible to Class 0 training samples.

Figure 9, Table 8 and Table 9 show that the hybrid method outperforms the standalone regression methods in multiple aspects. The test set results demonstrate that the hybrid framework achieves lower error compared to both CatBoost models across all measured metrics. The k-fold cross-validation results (with 95% confidence intervals) confirm this pattern across all five folds, where the hybrid method maintains consistently better performance with smaller variations between folds. This indicates that the hybrid framework is not only more accurate but also more stable across different data splits. The classification performance also shows the robustness of the hybrid method, matching the best CatBoost model while keeping lower error. The confusion matrices reveal important differences in how each method classifies the three payment classes, with the hybrid framework showing balanced performance across all classes, achieving the smallest error of false payouts and missed payouts. These results from both the test set and cross-validation suggest that the hybrid approach provides more reliable predictions for insurance payout estimation than using a single regression model alone.

Table 9.

K-fold performance metrics with 95% confidence intervals on the original dataset (5 Fold).

Table 10 summarizes the recommended model choices for different use cases. While the hybrid framework provides the best overall accuracy and robustness for deployment and policy design, CatBoost models can be used for rapid prototyping or benchmarking due to their simpler setup and faster training. Linear regression offers a fully transparent and interpretable alternative for explainable analysis, though with reduced predictive performance.

Table 10.

Recommended use of models by context.

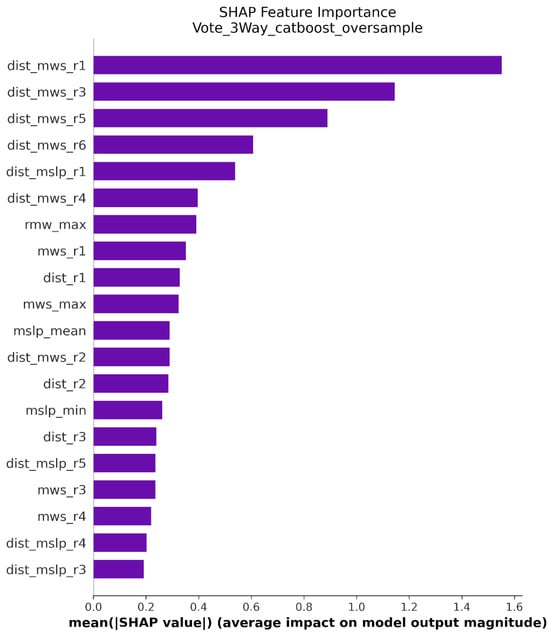

5. SHAP Analysis

The feature importance chart in Figure 10 shows that the interaction between distance and maximum wind speed at the first nearest observation (dist_mwsr1) has the strongest impact on model predictions. This variable combines two measurements: the distance from the insured asset to the first nearest cyclone eye and the maximum wind speed recorded at that point. The hybrid model gives this feature much more weight than any other input. Beyond the interaction terms, the feature importance chart shows that dist_mslpr1 (the interaction between distance and minimum sea level pressure at the first observation) also contributes meaningfully to predictions. Lower sea level pressure indicates stronger hurricanes, so this interaction captures another aspect of storm intensity combined with proximity. The model also considers rmw_max (maximum radius of maximum winds), mws_r1 (maximum wind speed at first observation), and dist_r1 (simple distance at first observation) as important, though with smaller effects than the interaction terms.

Figure 10.

Feature importance of the Hybrid framework.

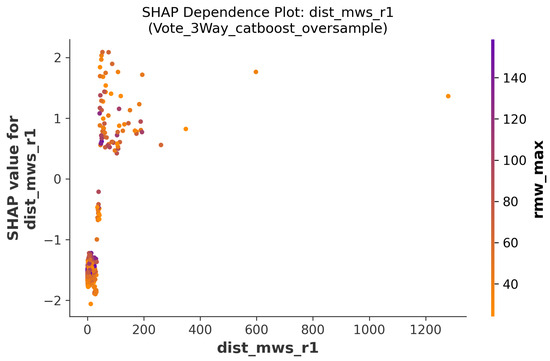

The second most important feature is dist_mwsr3, which represents the same type of interaction but at the third nearest observation point. Following this are dist_mwsr5 and dist_mwsr6, continuing the pattern at the fifth and sixth observation points. These interaction terms capture how the combined effect of storm intensity and proximity affects potential losses. When a hurricane with high wind speeds passes close to the insured property, the risk of damage increases greatly. Looking at the dependence plots reveals more specific patterns. For dist_mwsr1 in Figure 11, the relationship shows clear groupings. When this value is very low (near zero), the SHAP values are strongly negative, meaning the model predicts lower payouts. As dist_mwsr1 increases, the SHAP values rise sharply, reaching positive values around 2.0. The color coding shows that higher maximum wind speeds (indicated by darker purple and orange colors) tend to produce higher SHAP values, especially when combined with smaller distances.

Figure 11.

Dependence plot showing the interaction term between distance and maximum wind speed for first closest measurement point to the location of interest (Section 4.3).

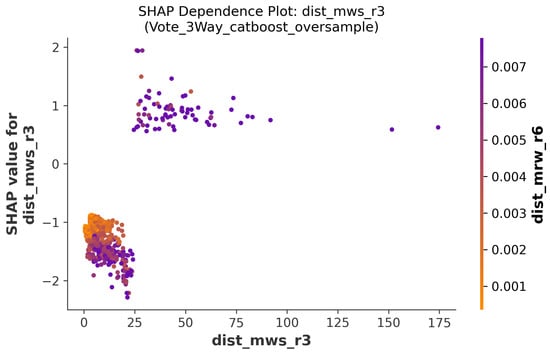

The dist_mwsr3 plot in Figure 12 shows a similar but less clear pattern. Most data points cluster in the lower range, with SHAP values mostly negative. Some points with higher dist_mwsr3 values show positive SHAP contributions, though the effect is smaller than for the first observation. This makes sense because hurricanes that are further away (third nearest point versus first nearest point) generally pose less immediate threat to the insured asset.

Figure 12.

Dependence plot showing the interaction term between distance and maximum wind speed for third closest measurement point to the location of interest (Section 4.3).

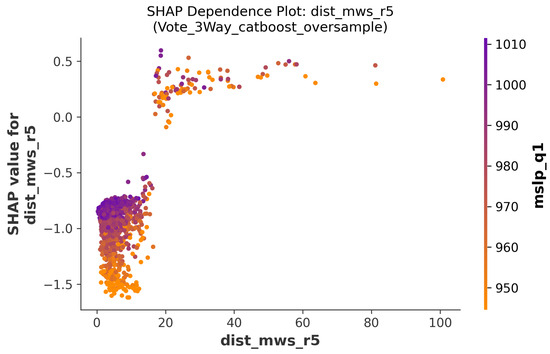

For dist_mws_r5, Figure 13 displays an interesting distribution. There is a dense cluster of points with low dist_mwsr5 values and negative SHAP values, representing hurricanes that stay far from the property. A smaller group of points with higher values shows positive SHAP contributions, indicating situations where the hurricane’s fifth observation point still matters for loss prediction. The pressure measurements (mslp) shown in the color scale reveal that lower pressure systems (darker colors) often connect to higher predicted losses.

Figure 13.

Dependence plot showing the interaction term between distance and maximum wind speed for fifth closest measurement point to the location of interest (Section 4.3).

The dist_mwsr6 dependence plot of Figure 14 shows more scattered behavior than the earlier observation points. The majority of points cluster at low values with negative SHAP contributions. However, there is a notable group of points at higher dist_mwsr6 values showing positive SHAP effects. This suggests that even at the sixth nearest observation, the model still considers certain hurricane configurations as relevant for loss prediction, though with less consistency than earlier points.

Figure 14.

Dependence plot showing the interaction term between distance and maximum wind speed for sixth closest measurement point to the location of interest (Section 4.3).

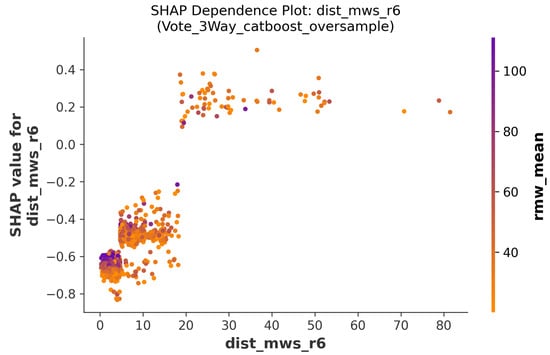

The summary plot in Figure 15 confirms these patterns across all features. For dist_mwsr1, there is a wide spread of SHAP values, with many points pushing predictions higher (positive values) and others pushing them lower (negative values). The color coding indicates that high feature values (purple/orange) generally increase predictions, while low values (yellow) decrease them. This pattern holds for most distance-wind speed interactions, though the effect weakens for observations further from the property. Single-variable features like mwsr1, distr1, and rmw_max show more concentrated distributions in the plot. Their SHAP values cluster closer to zero, meaning they have smaller individual effects. This explains why the model learns more from interaction terms than from individual measurements. A hurricane’s maximum wind speed matters less on its own than when considered together with how close the storm passes to the insured location. The minimum sea level pressure variables (mslp_mean, mslp_min) show moderate importance. Lower pressures (lighter colors) tend to increase predicted losses, though not as strongly as the distance-wind interactions. This suggests that while pressure measurements help the model understand storm intensity, the spatial relationship between the hurricane path and the insured asset matters more for accurate loss prediction. Looking at the overall distribution in the plot, most features show asymmetric effects. Features like dist_mwsr1 and dist_mwsr3 have long tails extending into positive SHAP values, indicating they strongly affect the model’s high-loss predictions. This asymmetry reflects the nature of hurricane risk: while many storms cause no damage (producing negative SHAP values that push predictions toward zero), a few dangerous storms produce very high losses (creating large positive SHAP values).

Figure 15.

Beeswarm plot from SHAP Analysis.

The analysis reveals that the model has learned physically meaningful patterns. Hurricanes that pass close to the insured property with high wind speeds create the highest risk. The model tracks multiple observation points along each hurricane’s path, with nearer observations (closer to the insured asset) mattering more than farther ones. This makes intuitive sense because the closest approach of a storm determines the worst conditions experienced at the property. The SHAP analysis also shows that the model uses information from multiple observation points, not just the closest one. This helps capture the full trajectory of each hurricane and accounts for storms that might intensify or change course.

6. Comparative Analysis with a Linear Regression Model

The scientific literature consistently highlights that linear modeling approaches offer clear advantages in parametric insurance compared to other less explainable models. Linear models are widely used in parametric insurance due to their interpretability, transparency, and regulatory compliance, which are critical in the highly regulated insurance industry as they could be easily transposed in (re)insurance contracts [47]. These models allow all the stakeholders (insurers, insureds, brokers, markets, investors and capital providers) to clearly understand and communicate how specified input variables (the parameters of a parametric policy) influence premium calculations, facilitating both internal validation and external justification to regulators and policy-holders. Despite their enhanced predictive power, more complex “black-box” models (i.e., relying on machine learning algorithms) might face limited adoption in the parametric insurance arena, because their complex and less transparent nature would make it more difficult to explain, and hence justify to the stakeholders, their response in the aftermath of a natural catastrophe, especially if the resulting payout is not aligned with the expectations [48]. Furthermore, linear models are computationally efficient and enable straightforward diagnostics and adjustments, which are essential for maintaining robust, examinable, and adaptable pricing frameworks in insurance operations.

The fit of a “black-box” model is typically better than that of a linear model, because “black-box” models have greater flexibility to capture complex patterns and non-linear relationships in the data. This section attempts to find a simplified, more explainable, linear parametric model for the tropical cyclone parametric risk transfer policy described in this paper, that minimizes the TAE. Firstly, the variables that had the greatest influence on the total loss were selected using the Elastic Net technique (EN). This technique enables effective variable selection by combining L1 and L2 penalties, resulting in sparse and robust models even in the presence of highly correlated predictors, which enhances both interpretability and model stability [49]. From a total of 76 variables, EN selected 8 variables as the most relevant for the model, assigning them non-zero coefficients after applying the combined L1 and L2 regularization, which indicates their greater predictive contribution and their importance compared to the other 68 predictors considered. These variables are the following:

- distr1, which is the distance from the insured asset to the hurricane center at the 1st nearest observation.

- mwsri, which are the Maximum Wind Speed values at observation point i, with i being 1, 3, 4, 5 and 6.

- dist_mwsr2, which is the interaction between the two previous variables at the 2nd nearest observation.

- dist_mwsr3, which is the interaction between the first two variables at the 3rd nearest observation.

The resulting model obtained via linear regression is as follows (please note that the logarithm was applied to the total losses variable due to its strong asymmetry):

When the model described in Equation (1) is applied to the same test data considered in this paper, it yields a TAE USD 4,852,145, achieving the lowest TAE compared to other parametric linear model, such as generalized linear models, where the error was around USD 7 million. As expected, this linear model results in a higher TAE than those resulting from the hybrid model described in this paper (USD 1,140,187), as it relies on a predefined functional form that restricts its flexibility and limits its capacity to capture complex or non-linear patterns in the data, reiterating the trade-off between accuracy and explainability, which is at the core of any parametric design.

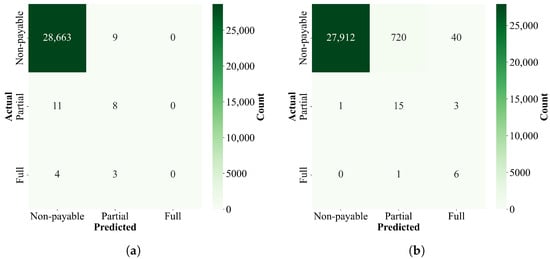

7. Experiments on a Distribution-Equivalent Dataset

The creation of synthetic data [50] required a mix of Gaussian and lognormal distribution fits to reproduce the characteristics of the real dataset. These distributions were fitted to capture different patterns present in the data. The Gaussian distribution helped model features that follow a normal pattern, while the lognormal distribution was better for features with positive skewness, which are common in insurance loss data. After fitting these distributions to the original dataset, synthetic values were generated and then clipped to match the main statistics of the real data. Once all the synthetic hurricane records were created, we checked if the new data matched the real data. Average values, spread of values, and quartile positions were compared for every measurement. The differences between real and synthetic data distributions were very small for most cases. This shows that the generation process worked correctly. The final dataset has the same number of records as the original data, keeping the same balance between hurricanes with damage and hurricanes without damage. For the regressor within the hybrid framework and as a standalone model, we adopted the oversampling strategy and CatBoost model identified in Section 4.4 as the best-performing configuration. Figure 16 and Figure 17, Table 11 and Table 12 report the final classification performance and TAE metrics. The results remain consistent with the original findings. The standalone CatBoost approach performs substantially worse than the hybrid framework in terms of prediction errors and overall balance between missed and false payouts. These results show that our hybrid framework offers superior performance in highly imbalanced data, achieving a better balance between class detection and accurate loss prediction.

Figure 16.

CatBoost 1 and 2 confusion matrices on the synthetic test set. (a) Confusion matrix for using standalone CatBoost1 as a classifier on the test dataset. (b) Confusion matrix for using standalone CatBoost2 as a classifier on the test dataset.

Figure 17.

Hybrid framework confusion matrix on the synthetic test set. Confusion matrix for using Hybrid framework as a classifier on the test dataset.

Table 11.

K-fold performance metrics with 95% confidence intervals on the synthetic dataset (5 Fold).

Table 12.

Performance metrics of final prediction.

8. Conclusions and Future Developments

In this paper, we presented a novel, hybrid approach to predicting hurricane-induced losses for specific points of interest using a combination of data analytics and machine learning techniques. By analyzing key physical parameters of hurricanes monitored at various timestamps, we proposed a methodology to develop parametric models capable of classifying new hurricane events into non-payable, partially payable, and fully payable categories. Our methodology incorporated high-fidelity simulations of stochastic hurricanes and associated losses, advanced data analytics techniques, and a two-track predictive modeling approach. The results demonstrate that our models could effectively classify hurricane events and predict payout amounts for partially payable events. The use of modeled data from a catastrophe model and synthetic data that are similar in the highly imbalanced sense, as well as the comparison of various classification and regression algorithms, ensures the robustness and adaptability of our approach. The hybrid approach described in this paper shows promising predictive performance, and the inclusion of the regression model as a classifier in the voting makes the resulting model less likely to miss potential payable events. Relatively small deviations between the predicted payout and the expected payment based on the actual losses from the underlying catastrophe model suggests reduction in basis risk, which is especially valuable for parametric insurance applications. Differently than more traditionally used cat-in-a-box methods, the proposed approach is not constrained by a fixed predefined ‘domain of interest’, and can be generalized to broader impact zones, reducing the chances to miss loss-inducing events. Moreover, it directly learns from the losses associated with each stochastic hurricane event, preserving event-level heterogeneity.

This data-driven model provides a more nuanced understanding of potential losses, enabling insurers to more accurately quantify potential payouts under extreme events, while also providing insured parties with greater clarity and fairness in the expected compensation. Whereas the proposed approach is not as interpretable as some methods like box-based or grid-based rules, it can still provide a valuable baseline to calibrate or validate auditable triggers intended for policy deployment. This helps reduce basis risk while preserving actuarial transparency. The study is also subject to certain limitations: (i) the synthetic dataset retains the same severe imbalance properties as the original data, but cannot secure the intricate feature relationships present in the private catastrophe model outputs; (ii) the framework developed contributes to reducing uncertainty in the estimation of insured losses but does not eliminate the inherent risk related to the variability of extreme events nor the uncertainty associated with decision-making under imperfect information.

Several areas for future research remain, among them: (i) to explore the inclusion of additional physical parameters and environmental factors, such as sea surface temperature, humidity, and landfall characteristics, in order to enhance the predictive power of the models; (ii) to improve the quality and completeness of the input data provided by the simulation stage; (iii) the methodology has been applied to the peril of hurricane, but it could be adapted and tested for predicting losses from other types of natural disasters, such as earthquakes, floods, and wildfires; and (iv) to analyze the broader economic and social impacts of improved loss prediction models, including their effects on insurance premiums, policyholder satisfaction, and overall financial resilience.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.G. and G.F.; methodology, A.A.J., Y.M., P.C. and J.A.C.-M.; validation, R.G. and G.F.; data curation, L.L.-V.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.M. and J.A.C.-M.; writing—review and editing, A.A.J., P.C. and R.G.; supervision, R.G. and A.A.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Risk Engineering + Development (www.redrisk.com), and, in particular, to Paolo Bazzurro and Gianbattista Bussi, for granting access to the modeling results for the case study discussed in this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Roberto Guidotti, Guillermo Franco and Laura Lemke-Verderme were employed by the company Guy Carpenter. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Dilley, M. Natural Disaster Hotspots: A Global Risk Analysis; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Jerry, R.H. Managing hurricane (and other natural disaster) risk. Tex. A M Law Rev. 2018, 6, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abtew, W. Hurricanes: Wind, rain, and storm surge. In Extreme Hydrology and Climate Variability; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 367–378. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, G.; Beer, M.; Kougioumtzoglou, I.; Patelli, E. Earthquake mitigation strategies through insurance. In Encyclopedia of Earthquake Engineering; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Y.; Ding, L.; Lai, K.h. How does index-based insurance support marine disaster risk reduction in China? Evolution, challenges and policy responses. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2023, 235, 106477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nostrand, J.M.; Nevius, J.G. Parametric insurance: Using objective measures to address the impacts of natural disasters and climate change. Environ. Claims J. 2011, 23, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Kwon, W.J. Application of parametric insurance in principle-compliant and innovative ways. Risk Manag. Insur. Rev. 2020, 23, 121–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, G.; Lemke-Verderame, L.; Guidotti, R.; Yuan, Y.; Bussi, G.; Lohmann, D.; Bazzurro, P. Typology and design of parametric cat-in-a-box and cat-in-a-grid triggers for tropical cyclone risk transfer. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.; Scaioni, M.; Marani, M. On the influence of global warming on Atlantic hurricane frequency. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2018, 42, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Tejeda, R.; Hernández-Ayala, J.J. Links between climate change and hurricanes in the North Atlantic. PLoS Clim. 2023, 2, e0000186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monerie, P.A.; Feng, X.; Hodges, K.; Toumi, R. High prediction skill of decadal tropical cyclone variability in the North Atlantic and East Pacific in the met office decadal prediction system DePreSys4. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2025, 8, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvet, L.; Lopeman, M.; de Armas, J.; Franco, G.; Juan, A.A. Statistical and machine learning approaches for the minimization of trigger errors in parametric earthquake catastrophe bonds. SORT-Stat. Oper. Res. Trans. 2017, 41, 373–392. [Google Scholar]

- Nobanee, H.; Nghiem, X.H. Climate catastrophe insurance for climate change: What do we know and what lies ahead? Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2024, 66, 101395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, G. Minimization of trigger error in cat-in-a-box parametric earthquake catastrophe bonds with an application to Costa Rica. Earthq. Spectra 2010, 26, 983–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goda, K.; Franco, G.; Song, J.; Radu, A. Parametric catastrophe bonds for tsunamis: CAT-in-a-Box trigger and intensity-based index trigger methods. Earthq. Spectra 2019, 35, 113–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margan, S.K. Overcoming basis risk in parametric insurance. Bimaquest 2021, 21, 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Steinmann, C.B.; Guillod, B.P.; Fairless, C.; Bresch, D.N. A generalized framework for designing open-source natural hazard parametric insurance. Environ. Syst. Decis. 2023, 43, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, J.D.; Mahul, O. Catastrophe Risk Financing in Developing Countries: Principles for Public Intervention; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zweifel, P. Bridging the gap between risk and uncertainty in insurance. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur.-Issues Pract. 2021, 46, 200–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wald, D.J.; Franco, G. Money Matters: Rapid Post-Earthquake Financial Decision-Making. Nat. Hazards Obs. 2016, 40, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Wald, D.J.; Franco, G. Financial Decision-Making based on Near-Real-Time Earthquake Information. In Proceedings of the 16th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Santiago de Chile, Chile, 9–13 January 2017; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Horton, J.B. Parametric insurance as an alternative to liability for compensating climate harms. Carbon Clim. Law Rev. 2018, 12, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, G. Construction of customized payment tables for cat-in-a-box earthquake triggers as a basis risk reduction device. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Structural Safety and Reliability (ICOSSAR), New York, NY, USA, 16–20 June 2013; pp. 5455–5462. [Google Scholar]

- Goda, K. Basis Risk of Earthquake Catastrophe Bond Trigger Using Scenario-Based versus Station Intensity–Based Approaches: A Case Study for Southwestern British Columbia. Earthq. Spectra 2013, 29, 757–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goda, K. Seismic Risk Management of Insurance Portfolio Using Catastrophe Bonds. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2015, 30, 570–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayliss, C.; Guidotti, R.; Estrada-Moreno, A.; Franco, G.; Juan, A.A. A biased-randomized algorithm for optimizing efficiency in parametric earthquake (Re) insurance solutions. Comput. Oper. Res. 2020, 123, 105033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collich, G.; Rosillo, R.; Martínez, J.; Wald, D.J.; Durante, J.J. Financial risk innovation: Development of earthquake parametric triggers for contingent credit instruments. In Natural Disasters and Climate Change: Innovative Solutions in Financial Risk Management; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.W.; Feng, Y. Hurricane Bond Price Dependency on Underlying Hurricane Parameters. Asia-Pac. J. Risk Insur. 2020, 15, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guelman, L. Gradient boosting trees for auto insurance loss cost modeling and prediction. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 3659–3667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, C.; Guerreiro, G.R.; Bravo, J.M. Gradient Boosting in Motor Insurance Claim Frequency Modelling. 2023. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/capsi2023/5/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- So, B. Enhanced gradient boosting for zero-inflated insurance claims and comparative analysis of CatBoost, XGBoost, and LightGBM. Scand. Actuar. J. 2024, 2024, 1013–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, D.; Côté, M.P. From Point to probabilistic gradient boosting for claim frequency and severity prediction. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.14916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordhaus, W.D. The Economics of Hurricanes in the United States. 2006. Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w12813 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Branco, P.; Torgo, L. A study on the impact of data characteristics in imbalanced regression tasks. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Data Science and Advanced Analytics (DSAA), Washington, DC, USA, 5–8 October 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 193–202. [Google Scholar]

- Avelino, J.G.; Cavalcanti, G.D.; Cruz, R.M. Resampling strategies for imbalanced regression: A survey and empirical analysis. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, P.; Torgo, L.; Ribeiro, R.P. Exploring resampling with neighborhood bias on imbalanced regression problems. In Proceedings of the Progress in Artificial Intelligence: 18th EPIA Conference on Artificial Intelligence, EPIA 2017, Porto, Portugal, 5–8 September 2017; Proceedings 18. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 513–524. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; Kunz, N.; Branco, P. Imbalancedlearningregression-a python package to tackle the imbalanced regression problem. In Proceedings of the Joint European Conference on Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases, Grenoble, France, 19–23 September 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 645–648. [Google Scholar]

- Branco, P.; Torgo, L.; Ribeiro, R.P. Pre-processing approaches for imbalanced distributions in regression. Neurocomputing 2019, 343, 76–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, P.; Torgo, L.; Ribeiro, R.P. SMOGN: A pre-processing approach for imbalanced regression. In Proceedings of the First International Workshop on Learning with Imbalanced Domains: Theory and Applications, Skopje, Macedonia, 22 September 2017; PMLR: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 36–50. [Google Scholar]

- Torgo, L.; Ribeiro, R. Predicting outliers. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Principles of Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, Cavtat/Dubrovnik, Croatia, 22–26 September 2003; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 447–458. [Google Scholar]

- Steininger, M.; Kobs, K.; Davidson, P.; Krause, A.; Hotho, A. Density-based weighting for imbalanced regression. Mach. Learn. 2021, 110, 2187–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgo, L.; Branco, P.; Ribeiro, R.P.; Pfahringer, B. Resampling strategies for regression. Expert Syst. 2015, 32, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubat, M.; Matwin, S. Addressing the curse of imbalanced training sets: One-sided selection. In Proceedings of the Icml. Citeseer, Nashville, TN, USA, 8–12 July 1997; Volume 97, p. 179. [Google Scholar]

- Kamalov, F.; Leung, H.H.; Cherukuri, A.K. Keep it simple: Random oversampling for imbalanced data. In Proceedings of the 2023 Advances in Science and Engineering Technology International Conferences (ASET), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 20–23 February 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Batista, G.E.; Prati, R.C.; Monard, M.C. A study of the behavior of several methods for balancing machine learning training data. ACM SIGKDD Explor. Newsl. 2004, 6, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, M.; Karimi, H. Weighted machine learning. Stat. Optim. Inf. Comput. 2018, 6, 497–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G.; Menon, S.; Ru, H.; Wright, R.; Hunt, X.; Abbey, R. Interpretation methods for black-box machine learning models in insurance rating-type applications. In Proceedings of the SAS Global Forum, Washington, DC, USA, 29 March–1 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Richman, R.; Wüthrich, M.V. LocalGLMnet: Interpretable deep learning for tabular data. Scand. Actuar. J. 2023, 2023, 71–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Hastie, T. Regularization and variable selection via the elastic net. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 2005, 67, 301–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, Y.; Guidotti, R.; Cuartas-Micieces, J.A.; Juan, A.A.; Franco, G.; Carracedo, P.; Lemke-Verderame, L. [Synthetic Dataset] a Hybrid Machine Learning Framework for Highly Imbalanced Data Predicting Hurricane Losses (Version 1); ResearchGate: Berlin, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.