Abstract

To address the limitations of Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) systems in handling long policy documents, mitigating information dilution, and reducing hallucinations in engineering-oriented applications, this paper proposes SPR-RAG, a retrieval-augmented framework designed for knowledge-intensive vertical domains such as electric power policy analysis. With practicality and interpretability as core design goals, SPR-RAG introduces a Semantic Parsing Retriever (SPR), which integrates community detection–based entity disambiguation and transforms natural language queries into logical forms for structured querying over a domain knowledge graph, thereby retrieving verifiable triple-based evidence. To further resolve retrieval bias arising from diverse policy writing styles and inconsistencies between user queries and policy text expressions, a question-repository–based indirect retrieval mechanism is developed. By generating and matching latent questions, this module enables more robust retrieval of non-structured contextual evidence. The system then fuses structured and unstructured evidence into a unified dual-source context, providing the generator with an interpretable and reliable grounding signal. Experiments conducted on real electric power policy corpora demonstrate that SPR-RAG achieves 90.01% faithfulness—representing a 5.26% improvement over traditional RAG—and 76.77% context relevance, with a 5.96% gain. These results show that SPR-RAG effectively mitigates hallucinations caused by ambiguous entity names, textual redundancy, and irrelevant retrieved content, thereby improving the verifiability and factual grounding of generated answers. Overall, SPR-RAG demonstrates strong deployability and cross-domain transfer potential through its “Text → Knowledge Graph → RAG” engineering paradigm. The framework provides a practical and generalizable technical blueprint for building high-trust, industry-grade question–answering systems, offering substantial engineering value and real-world applicability.

1. Introduction

Large Language Models (LLMs) have fundamentally reshaped research paradigms in natural language processing (NLP) and transformed the way humans interact with textual information. Leveraging their strong capabilities in language understanding and generation, LLMs have achieved remarkable success in general-purpose tasks [1]. However, in specialized domains such as electric power policy, law, and medicine, their performance is often hindered by limited domain knowledge, misinterpretation of complex context, and the highly specialized nature of tasks, resulting in insufficient accuracy and unstable reliability [2,3].

To enhance LLM performance in domain-specific applications, two mainstream strategies are commonly adopted: (a) fine-tuning LLMs on domain corpora to adapt them to specialized contexts; and (b) improving QA capability through retrieval augmentation. While fine-tuning can effectively improve domain adaptability [1], it requires substantial computational resources, incurs high costs, and suffers from catastrophic forgetting [4,5,6,7], in which the model loses previously acquired knowledge when learning new tasks. In contrast, Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) retrieves external documents as grounding evidence without modifying model parameters, thereby improving correctness and robustness at a significantly lower cost [8,9,10].

Traditional RAG relies on vector-based retrieval: documents are encoded into embeddings and stored in a vector database, and similarity to a query embedding determines the retrieved context. However, this mechanism faces two major challenges: (a) Information dilution—vector retrieval may return passages that are lexically similar but semantically irrelevant, reducing answer precision; (b) Hallucinations—LLMs may generate fluent yet factually incorrect or irrelevant content [11,12].

Semantic parsing offers a promising direction for addressing structural information gaps and hallucination issues in RAG. By converting a query into a logical form and then into a knowledge base query, semantic parsing enables structured retrieval from a knowledge graph. Through the pipeline “Question Q → Logical Form → SPARQL Query → Triples T,” the system can extract semantically linked structured facts and verbalize the triples into natural language, which are then combined with unstructured text retrieved by the vector retriever to form a dual-source context. This enhances both interpretability and factual grounding.

However, query expansion methods such as HyDE [13], which generate hypothetical documents to aid retrieval, often fail in specialized domains like electric power policy. Since general-purpose LLMs lack professional domain knowledge, the generated hypothetical content may deviate from actual policy texts, weakening retrieval quality. To address this limitation and ensure stronger coupling between retrieval and domain semantics, we introduce a latent question expansion mechanism—the Question Bank (K module)—which generates and stores potential questions from each document to create a more domain-robust retrieval layer.

Against this backdrop, we propose SPR-RAG (Synergizing Semantic Parsing RAG), an enhanced RAG system with four major contributions: (a) Semantic Parsing Retriever (SPR), enabling interpretable structured retrieval and improving factual consistency. The SPR module follows the pipeline “query → logical form → knowledge graph query → triples,” providing verifiable structured evidence that complements vector-retrieved text. This significantly improves Faithfulness and Context Relevance while reducing hallucinations. The module is plug-and-play and can be integrated into any RAG framework. (b) A community-detection-based entity disambiguation weighting mechanism to improve structured retrieval accuracy. Given the prevalence of ambiguous entity names in policy documents, we refine prior disambiguation weights using Louvain community detection and degree centrality normalization, enhancing semantic consistency in entity linking and enabling SPR to retrieve more accurate triples. (c) A question-bank–based indirect retrieval module (K module) to enhance unstructured text recall quality. By generating latent questions for each text segment, we replace traditional vector retrieval with semantic question matching, substantially improving alignment between user queries and candidate passages, thereby increasing context quality and reducing noise. (d) A transferable engineering pipeline from “text → knowledge graph → RAG.” We implement a complete domain-to-RAG workflow including preprocessing, knowledge graph construction, triple extraction, community-based disambiguation, question bank generation, and RAG dataset creation. This pipeline is independent of public benchmarks and can be adapted to a wide range of domain-specific QA tasks.

To validate SPR-RAG, we conduct experiments on electric power policy documents provided by the State Grid Henan Electric Power Research Institute. Our study focuses on the following research question: “How does the improved SPR-RAG compare with traditional RAG baselines in terms of generation quality?” The experiments comprehensively evaluate SPR-RAG against standard RAG methods on domain data. This work is positioned as an engineering-oriented study, emphasizing reliability, interpretability, and system transferability rather than solely pursuing maximal numerical gains.

2. Related Work

The development of the Transformer architecture has driven the emergence of numerous high-performance LLMs, including OpenAI’s GPT series, Google’s PaLM, and Meta’s LLaMA family [14,15,16,17]. Such models, built upon decoder-only, encoder-only, or encoder–decoder structures, demonstrate strong adaptability across diverse language tasks. In recent years, generative question answering has gained significant attention [18,19,20,21,22], and research has gradually expanded from general-purpose QA to specialized domains such as law, medicine, and education [23]. However, in highly specialized fields such as policy interpretation, LLMs often underperform due to insufficient domain coverage in training corpora.

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) combines a retriever with an LLM generator to address knowledge-intensive QA tasks [9]. Although traditional RAG alleviates the problem of insufficient model knowledge, it still suffers from semantic drift in embedding space, lack of structured policy information, and limited verifiability of the results. To overcome these limitations, prior work has attempted hybrid retrieval, graph-assisted retrieval, or lightweight structural augmentation. For example, Blended RAG integrates semantic and sparse retrieval to improve recall quality [24]; GraphRAG incorporates knowledge graph structure to enhance reasoning capability [25]; LightRAG follows the RAG paradigm while improving inference speed and deployment efficiency through lightweight design [26]. However, these graph-augmented methods typically rely on LLM-generated pseudo-graphs, which may contain hallucinated entities or relations, making them unsuitable for domains such as electric power policy that require rigorous semantic structure.

Semantic parsing plays a crucial role in knowledge-driven QA by converting natural language questions into logical forms and executing knowledge base queries. Classical KBQA approaches—such as the knowledge retrieval framework proposed by Yao et al. [27]—retrieve relevant entities and relations to answer questions over knowledge bases. Zhang et al. and Oguz et al. further explored entity retrieval and multi-hop entity navigation [28,29], while additional improvements came from named entity recognition (NER) [30] and entity linking (EL) techniques [31], which enhance retrieval precision. Integrating semantic parsing into RAG provides a reliable complement to unstructured retrieval, significantly reducing hallucinations and improving factual verifiability.

HyDE (Hypothetical Document Embeddings) represents a typical query expansion method, where a “hypothetical answer” is generated and embedded to improve retrieval. However, in specialized domains such as electric power policy, the hypothetical content produced by general-purpose LLMs often deviates from actual policy semantics due to a lack of domain knowledge, resulting in weaker retrieval relevance. By contrast, the Question Bank (K module) proposed in this study constructs a domain-grounded latent question repository directly from policy documents. This design tightly couples query expansion with domain semantics, avoiding the risks introduced by hallucinated pseudo-documents and substantially improving retrieval robustness.

A review of the above studies reveals several engineering gaps in building deployable and highly reliable RAG systems for rigorously defined domains such as electric power policies. First, at the architectural level, existing frameworks lack standardized and pluggable modules that can seamlessly integrate structured knowledge retrieval with unstructured text retrieval, making it difficult to ensure both factual precision and semantic flexibility in the generated answers. Second, in terms of domain adaptation, most methods do not provide lightweight and efficient solutions to the widespread entity ambiguity problem inherent in specialized fields (e.g., power-sector regulations), resulting in reduced accuracy of knowledge retrieval. Third, regarding retrieval-augmentation strategies, general query expansion techniques such as HyDE often introduce semantic drift in domain-specific scenarios due to their disconnect from domain knowledge, highlighting the absence of an enhancement mechanism that derives from the domain corpus itself and preserves semantic consistency. Table 1 summarizes the core differences between SPR-RAG and existing RAG methods, demonstrating that SPR-RAG provides clear advantages in structured information utilization, entity disambiguation, and domain adaptability—particularly suitable for engineering-oriented applications such as electric power policy analysis.

Table 1.

Comparison Between SPR-RAG and Existing RAG Methods.

3. SPR-RAG Architecture and Design Principles

Before introducing the proposed framework, we briefly recall the definition of RAG: given a corpus C and a query Q, a RAG system retrieves relevant text segments from C and generates an answer A conditioned on both the retrieval results and the generative model.

The performance of a RAG system mainly depends on two factors: whether the retrieved context is highly relevant to the query, and whether the generator can maintain faithfulness while utilizing this context. In the domain of electric power policy analysis, traditional RAG faces several structural challenges: policy documents are long, semantically heterogeneous, and contain numerous entity homonyms, all of which contribute to retrieval errors, context mismatch, and factual hallucinations. To address these issues, we propose SPR-RAG (Semantic Parsing Retriever–RAG), an engineering-oriented and high-reliability QA system that integrates structured knowledge retrieval, latent-question–driven text matching, and entity-level semantic disambiguation.

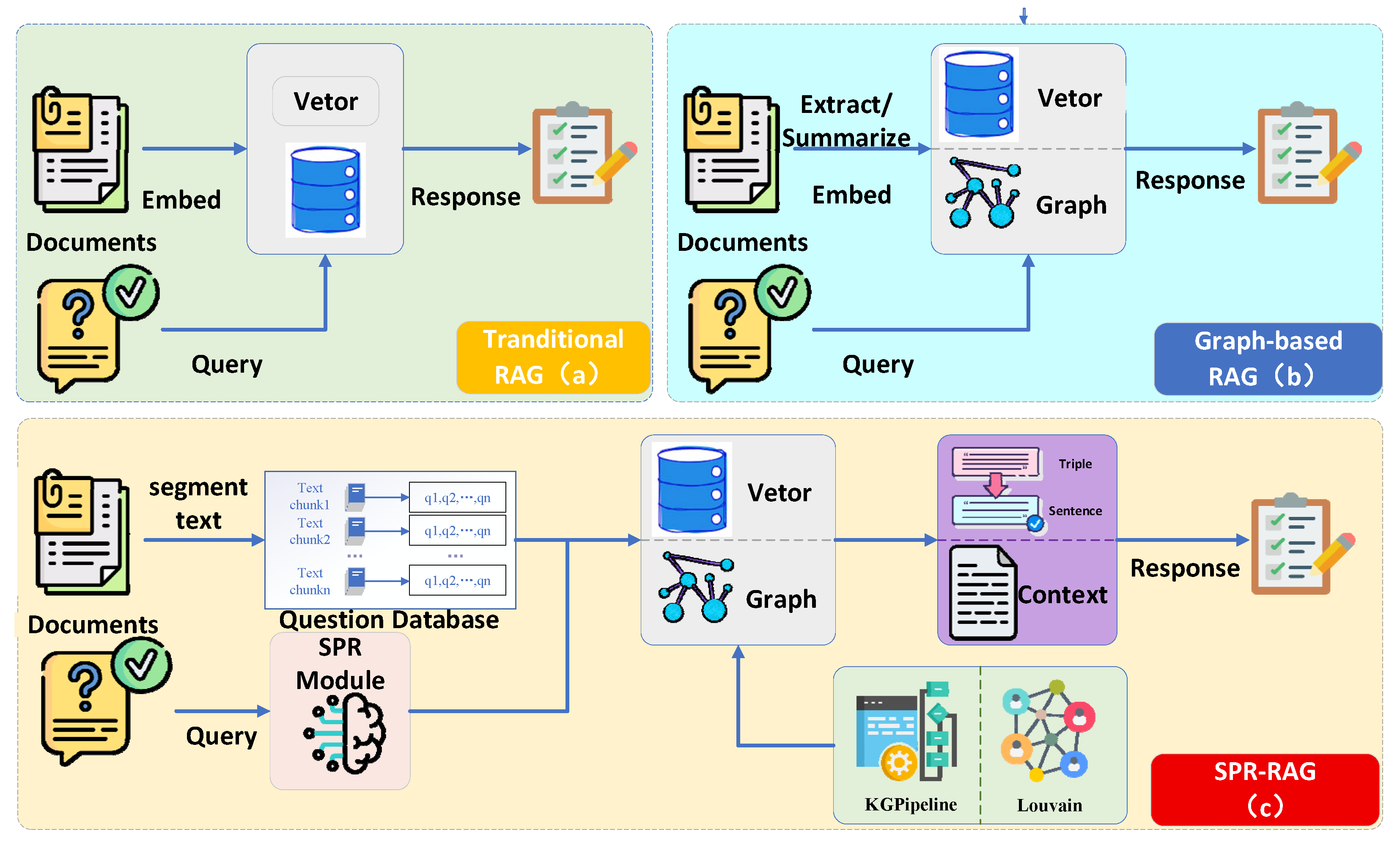

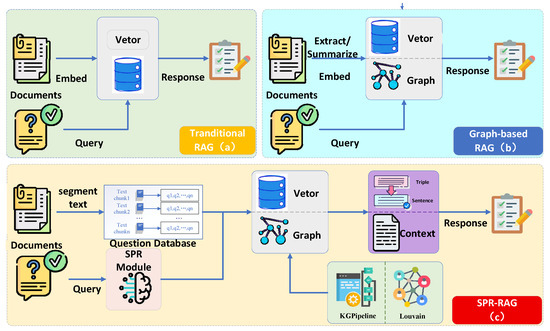

SPR-RAG consists of four core modules: (a) KGPipeline, which constructs a domain knowledge graph and provides the structured foundation for semantic parsing retrieval; (b) Community-based Entity Disambiguation, which optimizes entity weights based on graph structure to improve entity resolution accuracy; (c) Question Bank (K) Module, which retrieves unstructured context through latent question matching to achieve high semantic alignment; and (d) Semantic Parsing Retriever (SPR), which performs logical-form–driven structured retrieval to obtain precise factual triples. The overall architecture of SPR-RAG and its comparison with mainstream RAG paradigms are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Unified Comparison of SPR-RAG and Mainstream RAG Frameworks (a) Traditional RAG, which performs single-source vector retrieval. (b) Graph-based RAG, which constructs static knowledge graphs and retrieves from them. (c) SPR-RAG, which introduces semantic parsing retrieval (“question → logical form → knowledge graph query”) and a question-bank-based mechanism to enhance semantic alignment in unstructured retrieval, forming a dual-source evidence fusion framework.

The foundation of SPR-RAG lies in its KGPipeline, which constructs a high-quality knowledge graph tailored to the electric power policy domain. Unlike vector-based RAG systems that struggle with the structural characteristics and relational complexity of policy documents, the knowledge graph provides structured entity–relation–entity triples, a well-organized semantic hierarchy, and interpretable, queryable, and verifiable knowledge. The pipeline converts raw policy documents into a knowledge graph through preprocessing, document segmentation, ontology-guided extraction of entities and relations, validation, and graph writing. This structured representation enables downstream logical-form–based semantic parsing and query execution.

Entity ambiguity is especially prominent in policy texts, where many entities share identical surface forms (e.g., “Energy Bureau”, “Planning Office”, “Standardization Center”). Without proper disambiguation, structured retrieval would return incorrect triples and exacerbate hallucinations. To mitigate this, SPR-RAG incorporates a community-structure–aware disambiguation mechanism that leverages graph community detection and degree centrality to refine entity weighting. By integrating surface-level priors with graph-derived structural information, the system produces more accurate disambiguation scores before executing a KG query, essentially acting as a quality filter to ensure that the semantic parsing module retrieves the correct entity rather than a surface-similar but semantically unrelated one.

Because policy documents contain rich descriptive details beyond what a knowledge graph alone can capture, SPR-RAG introduces the question bank K as a second retrieval path. Traditional vector retrieval is highly sensitive to lexical similarity and can easily be misled by long or noisy policy text; in contrast, the K module converts each text chunk into a set of latent questions that better mirror QA semantics. This design bridges the gap between policy writing style and natural user queries, enhances robustness against irrelevant matches, and significantly improves semantic alignment. When a user submits a query, the system retrieves the most semantically similar latent question from the question bank and maps it back to the originating text chunk, thus obtaining unstructured context that best matches the user’s intent.

Structured retrieval is handled by the semantic parsing retriever (SPR), which translates the natural language query into a logical form, aligns entities and relations using the optimized disambiguation weights, and executes knowledge graph queries to extract accurate and verifiable triples such as ⟨Issuing Authority—publish—Policy⟩ or ⟨Policy—support—Project⟩. The structured evidence produced by SPR provides high factual reliability, strong interpretability, and inherent resistance to hallucination, making it central to the trustworthy operation of SPR-RAG.

Rather than relying on a single retrieval path, SPR-RAG fuses the structured triples obtained through SPR with the semantically aligned text chunks retrieved via the K module. This dual-source evidence—structured for verifiability and unstructured for contextual richness—overcomes the limitations of traditional RAG systems that either lack structural knowledge or suffer from insufficient semantic depth. Structured knowledge constrains the generator and enhances factual faithfulness, while unstructured text preserves contextual completeness, jointly forming the core advantage of SPR-RAG.

4. System Implementation

4.1. Domain Knowledge Graph Construction

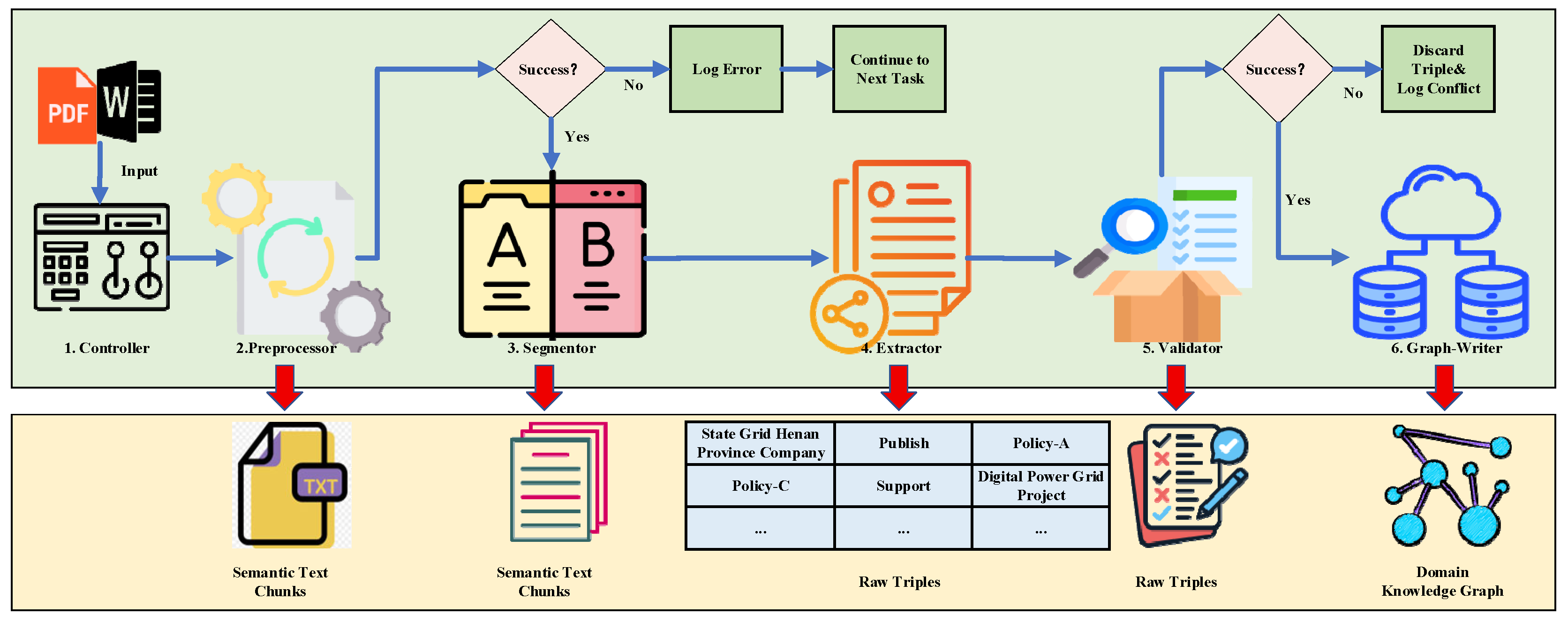

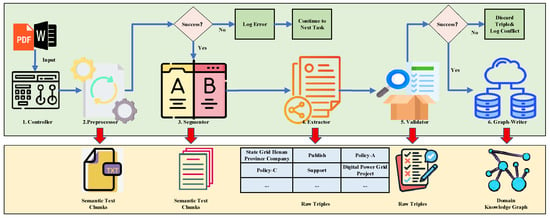

This study designs and implements a large-language-model–assisted pipeline architecture, termed KGPipeline, for constructing a domain-specific knowledge graph for electric power policies. Inspired by the workflow of a human expert team, KGPipeline adopts a “central controller + specialist modules” paradigm. It consists of one controller and five functional modules—Preprocessor, Segmentor, Extractor, Validator, and Graph-Writer—which together enable automated transformation of raw policy documents into a high-quality knowledge graph. The overall architecture is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Architecture of the KGPipeline system.

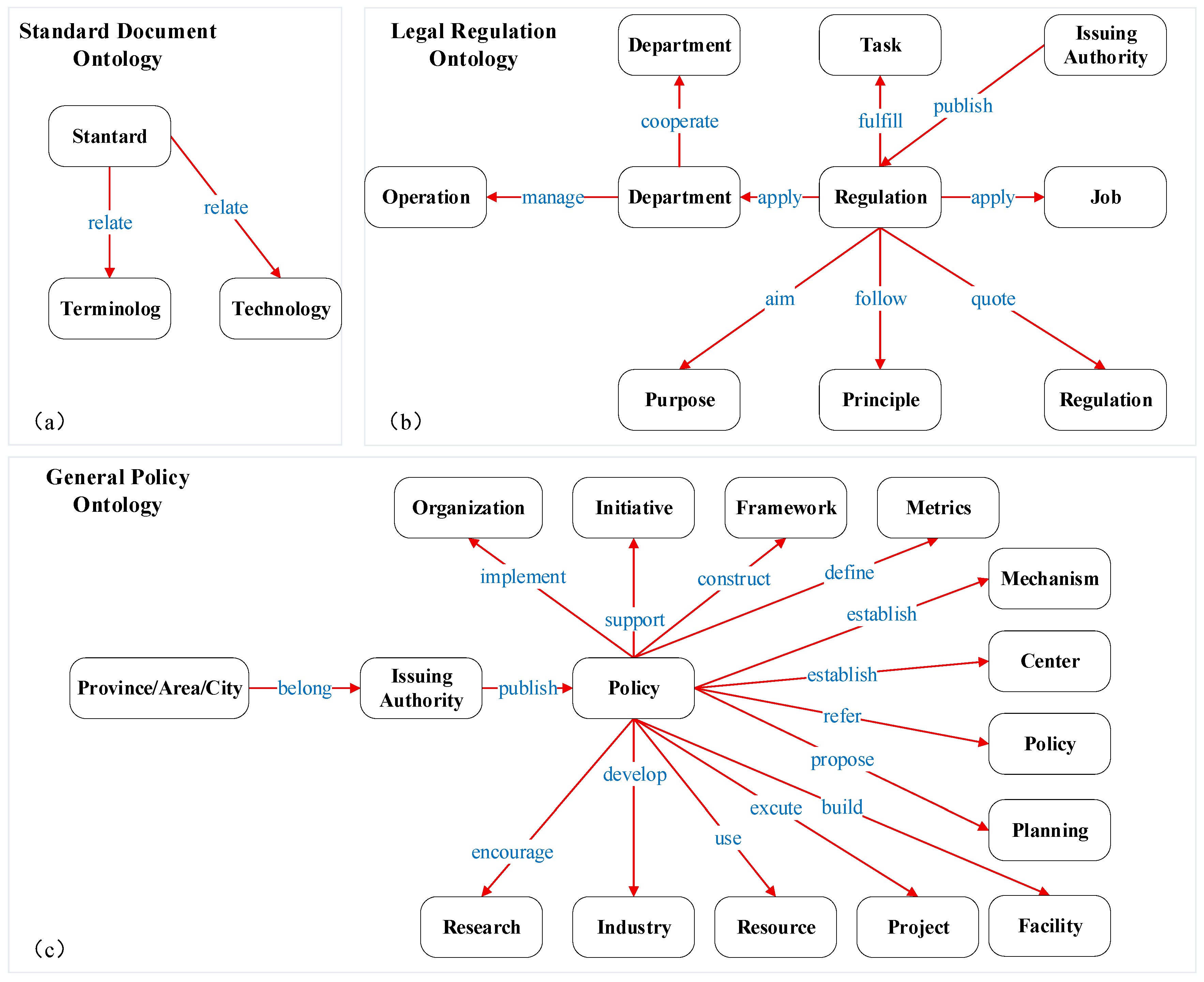

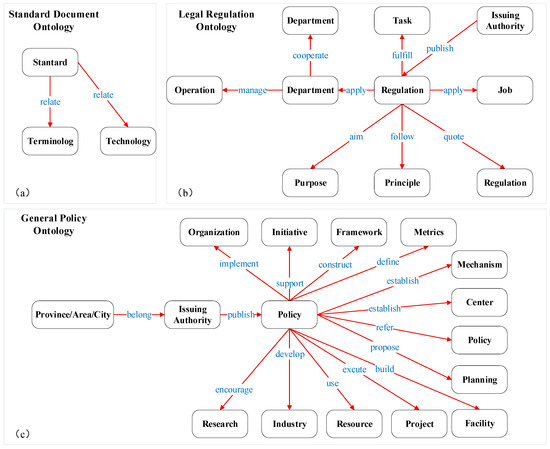

4.1.1. Ontology Design

Ontology-based modeling provides the structural foundation for defining domain-specific entities, relations, and attributes. Existing systems such as GraphRAG generally adopt a bottom-up approach, directly constructing graphs from text without considering domain-specific conceptual structures. As a result, the produced knowledge graphs often contain overly long node names, missing information, or inconsistent semantics. To overcome these limitations, this study adopts a top-down ontology-driven approach for constructing the knowledge graph of electric power policy documents. Policy documents in this domain involve hierarchical issuing authorities (national, provincial, corporate levels) and diverse document types (regulations, notices, standards, guidelines). Through domain analysis, we identify three distinct semantic categories—General Policies, Legal Regulations, and Standard Documents—each exhibiting different knowledge structures. For each category, a dedicated ontology is designed, defining its core entities, relations, and structural constraints.

General Policies include notices, guidelines, opinions, announcements, etc. These documents typically specify planning goals, institutional arrangements, construction tasks, or industrial development measures. They contain entities such as indicators, mechanisms, centers, plans, and infrastructure, with relations such as establish, propose, construct, and implement. The ontology is shown in Figure 3a.

Figure 3.

Ontology models of Standard Documents, Legal Regulations, and General Policies.

Legal Regulations include laws, regulations, rules, and administrative measures. Their semantic structure centers on principles, tasks, purposes, and responsibilities, with relations such as apply to, comply with, achieve, and implement, as shown in Figure 3b.

Standard Documents mainly consist of national or industry standards, describing terminology definitions and technical requirements. The ontology is relatively simple and is shown in Figure 3c. Table 2 presents representative entity–relation patterns from the ontology.

Table 2.

“Entity-Relationship-Entity” Table (Partial).

4.1.2. KGPipeline Implementation

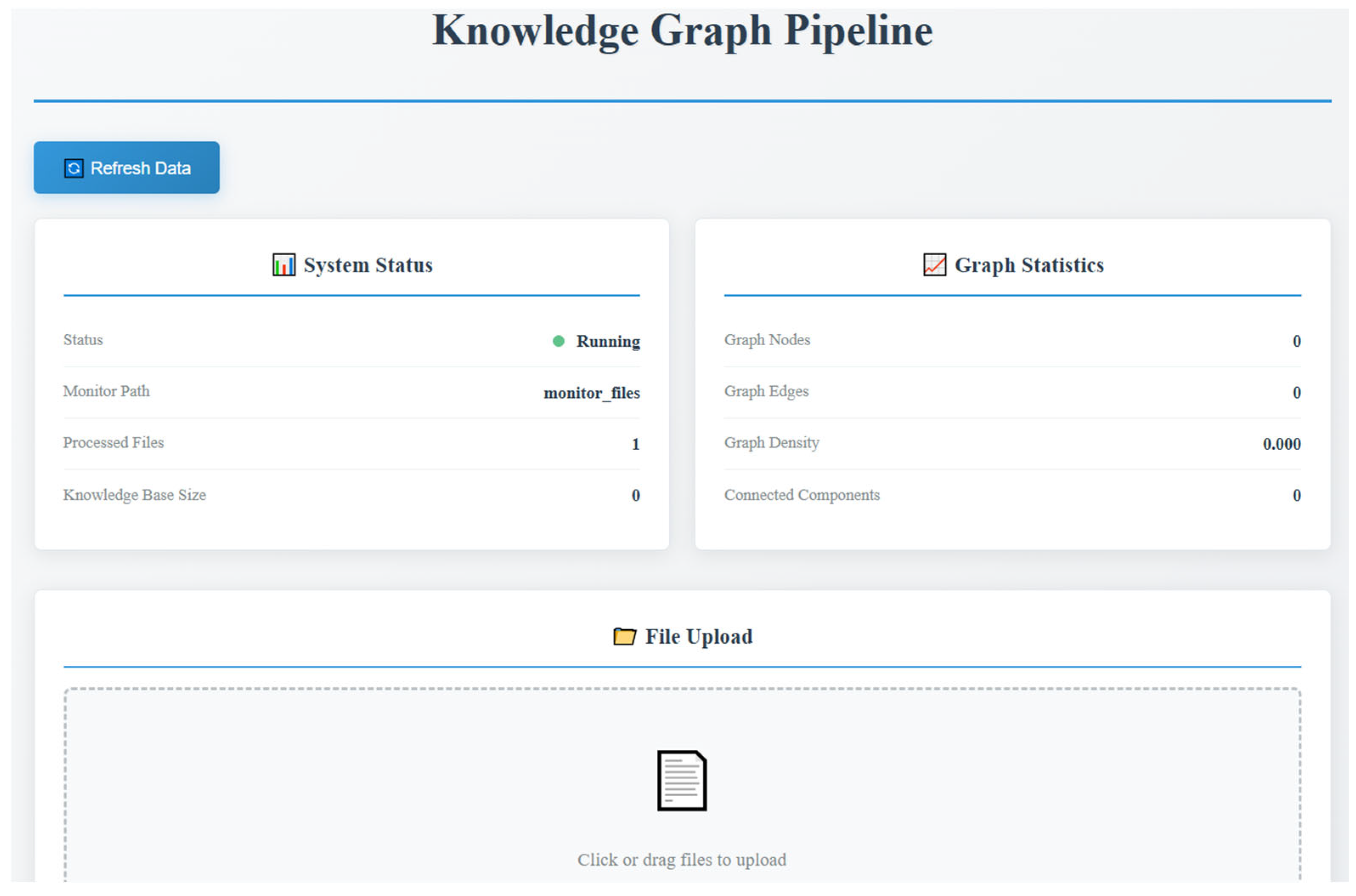

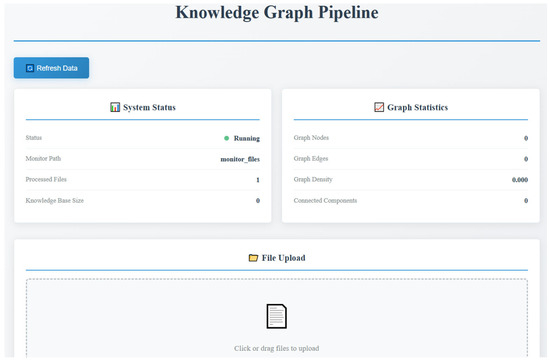

KGPipeline consists of a controller and five expert modules: preprocessing, text segmentation, information extraction, quality validation, and graph writing. The graphical interface of KGPipeline is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Visualization of the KGPipeline Interface.

- Controller Module, the controller ensures stable pipeline execution by maintaining a global task queue. When a component fails (e.g., parsing errors), the controller decides whether to retry (for recoverable errors such as timeouts) or skip the document (for unrecoverable errors such as corrupted files). This prevents failure of a single document from affecting the entire batch processing task.

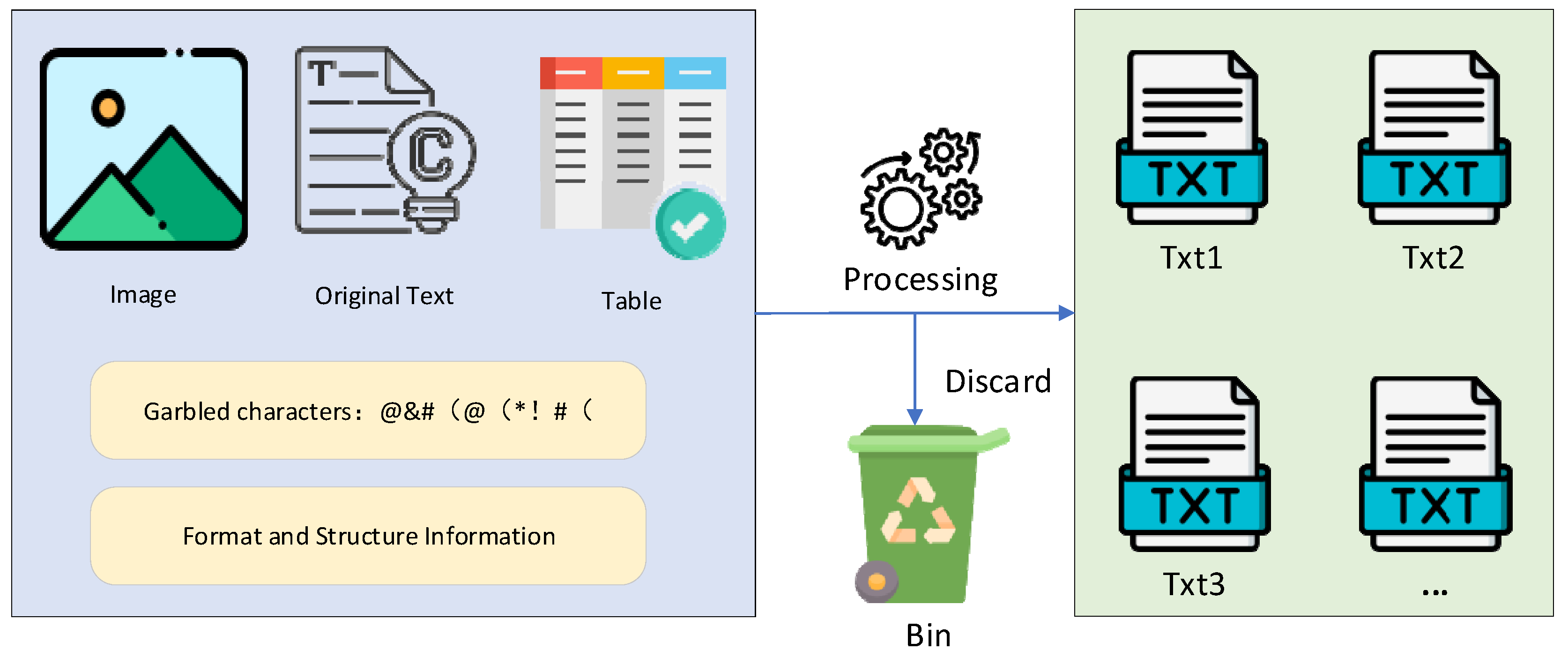

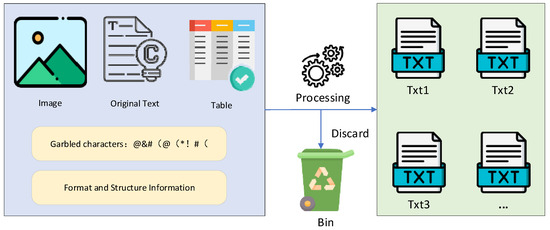

- Preprocessor Module, this module performs document format detection, text extraction, page number removal, figure/table caption filtering, and corrupted-line cleaning. The output is a normalized UTF-8 plain text file suitable for further processing. Figure 5 shows a before-and-after comparison of preprocessing.

Figure 5. Preprocessing Workflow.

Figure 5. Preprocessing Workflow. - Text segmentation follows a two-stage strategy—structural probing → semantic chunking → length compensation: Detect multi-level headings via regex pattern matching. If hierarchical headings exist, use the deepest level to segment content semantically. Otherwise fall back to a recursive token-based character segmentation method (chunk size: 512 tokens; overlap: 50 tokens; depth limit: 6; minimal segment length: 32 tokens). Post-processing merges fragments containing fewer than two sentences. Each segment is assigned a globally unique chunk-id.

- Information Extraction Module, this module extracts triples from segmented text chunks using LLMs. Prompts are designed according to the three ontology categories to guide domain-specific extraction. We evaluate three LLMs (Table 3): Qwen1.5-32B, ChatGLM3-6B, and DeepSeek-MoE-16B. Qwen1.5-32B achieves the highest accuracy, recall, and F1, and is therefore adopted for triple extraction. Table 4 illustrates typical triple extraction examples.

Table 3. Performance of LLMs in triple extraction.

Table 3. Performance of LLMs in triple extraction. Table 4. Examples of Triple Extraction.

Table 4. Examples of Triple Extraction. - Quality Validation Module, his component ensures that all extracted triples strictly comply with the ontology constraints. For each triple, the module checks whether the entity types and relation match the ontology (e.g., Issuing Agency → issues → Policy Clause is valid, while Policy Clause → issues → Issuing Agency is not). Invalid triples are marked as Conflict, logged with detailed error messages, and discarded. Table 5 shows examples of correct and incorrect triples. This module significantly improves the logical consistency and reliability of the final knowledge graph.

Table 5. Examples of valid and invalid triples.

Table 5. Examples of valid and invalid triples. - Graph-Writer Module, validated triples are stored in a locally deployed Freebase-compatible RDF store as the backend of the SPR module for SPARQL-based structured retrieval.

4.2. Community-Based Entity Disambiguation Weighting

4.2.1. Computing Prior Disambiguation Weights

In the energy-policy domain, many entities exhibit ambiguous surface forms (e.g., “development plan” may refer to a national plan or an industry-specific plan). Entity disambiguation is essential for accurately identifying and aligning the entities mentioned in user queries, thereby improving the accuracy and robustness of downstream question answering. However, due to the lack of large-scale manually annotated ⟨surface form, entity⟩ pairs in this domain, training deep neural disambiguation models—which require tens of thousands of labels and multi-day GPU computation—is impractical.

To address this, we first perform a reverse scan over all triples to collect a mapping of [surface form → candidate entity IDs], generating an initial dictionary in which each surface form may correspond to multiple entity IDs (heteronym candidates). Next, manual synonym inspection is conducted: for each group of candidates sharing the same surface form, two annotators independently determine whether the entities refer to the same real-world object. If so, only one ID is retained; otherwise, distinct IDs are preserved with disambiguating suffixes (e.g., Electricity Subsidy–Provincial, Electricity Subsidy–Municipal). This produces an unambiguous entity-ID inventory.

Subsequently, GPT-3.5-turbo-16k is used for entity linking over the policy corpus. The unambiguous entity-ID table is provided as context, and the model is constrained to match only surface forms appearing in the table. The resulting surface-form frequency is used to compute prior weights:

Here, count(s, e) denotes the number of times surface form s is linked to entity e in the full text, and the denominator is the total count of all entities linked to the same surface form s.

4.2.2. Community-Based Optimization of Disambiguation Weights

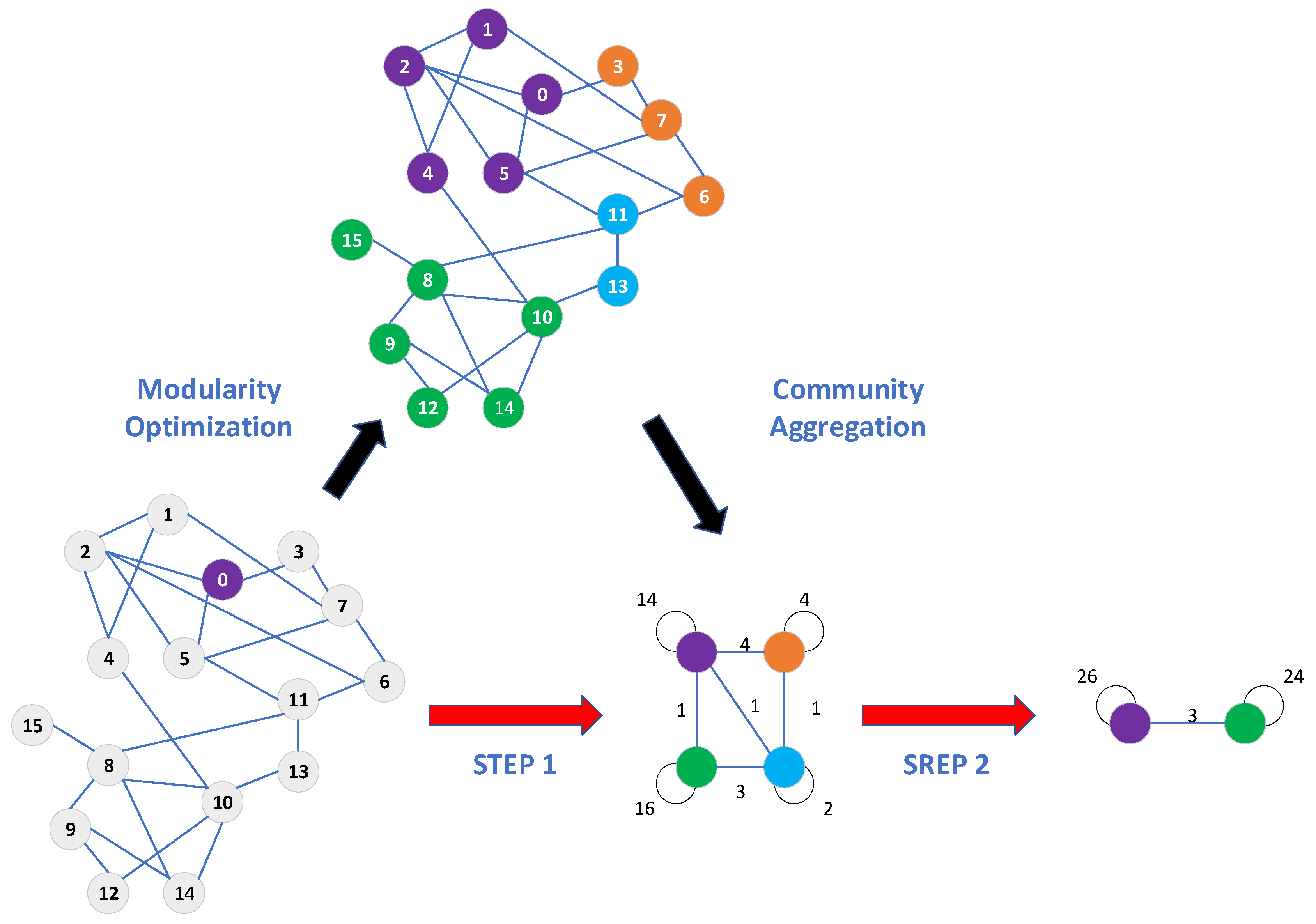

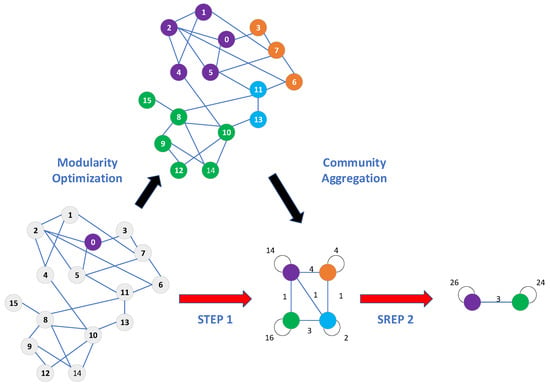

Frequency-based prior weights wf alone cannot capture the semantic and structural role of an entity within the knowledge graph. To enhance disambiguation accuracy, we integrate graph-structural information by applying the Louvain community detection algorithm to the domain knowledge graph. Louvain is selected due to its advantages—no need to predefine the number of clusters, capability to handle large graphs, and high computational efficiency. A schematic of the Louvain algorithm is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Community Detection Algorithm Principle.

Modularity maximization: Louvain partitions the graph by maximizing modularity:

where Aij is the adjacency matrix element; ki is the degree of node i, and m is the total number of edges in the graph. ci is the community label of node i, and is the Kronecker delta. Higher modularity indicates stronger intra-community cohesion.

After obtaining community structures, we compute degree centrality:

where deg(vi) represents the degree of node vi, i.e., the number of connections to other nodes, and N is the total number of nodes in the community.

Based on the community structure, we normalize the degree centrality for each node in a community so that the central node’s normalized score is 1, and the other nodes are scaled within the range [0, 1]. This normalization ensures that the relative importance of nodes within the community is preserved while giving core nodes a higher weight in the allocation process.

where wi is the normalized weight of node vi, and represents the maximum degree centrality value of the node in community Ck. The degree centrality of nodes is then geometrically averaged with the original entity disambiguation weight to obtain the new weight. The fusion formula is as follows:

This fused weighting mechanism incorporates both textual co-occurrence evidence (prior) and topological significance (graph structure), enabling more accurate entity matching during structured retrieval.

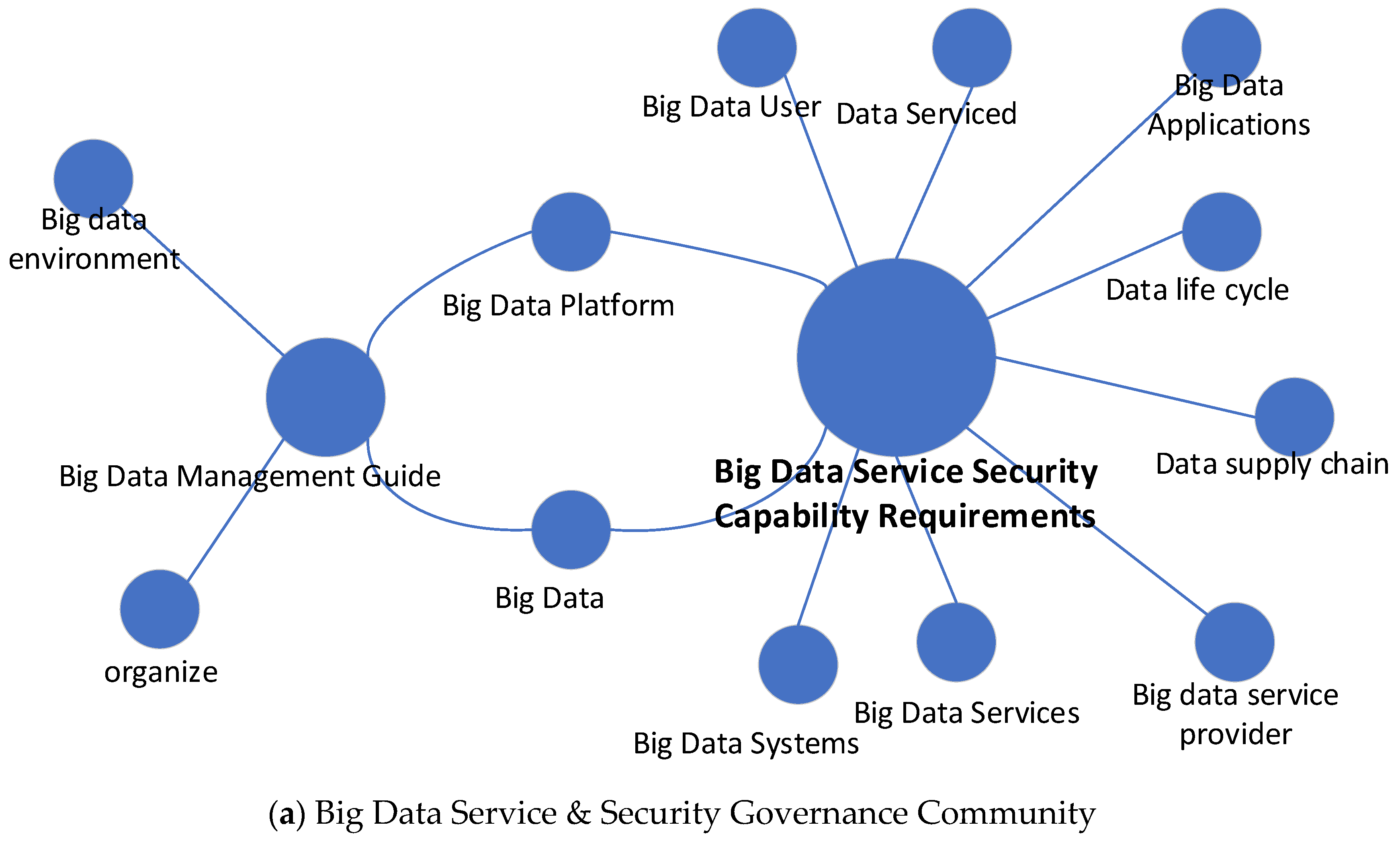

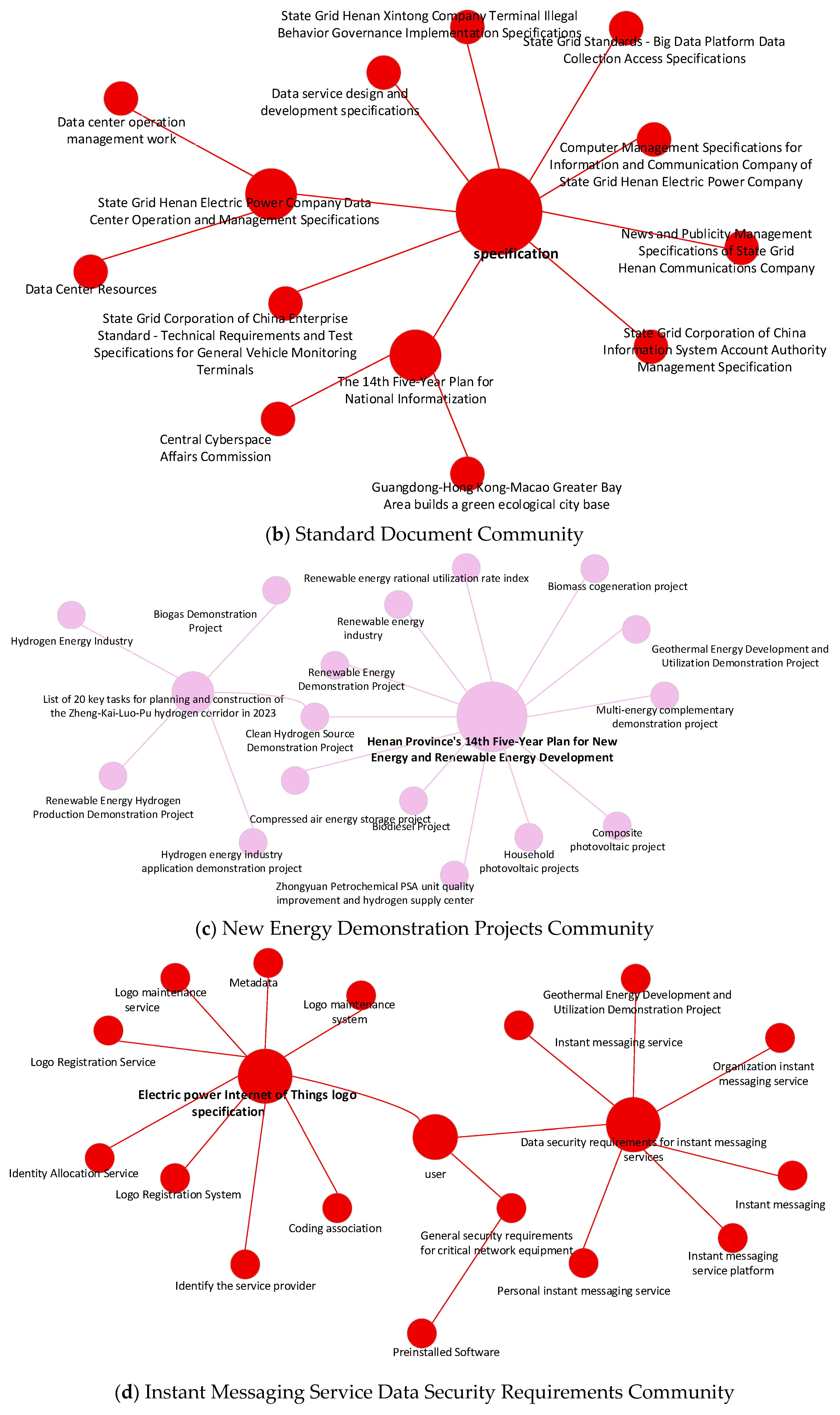

4.2.3. Community Detection Results

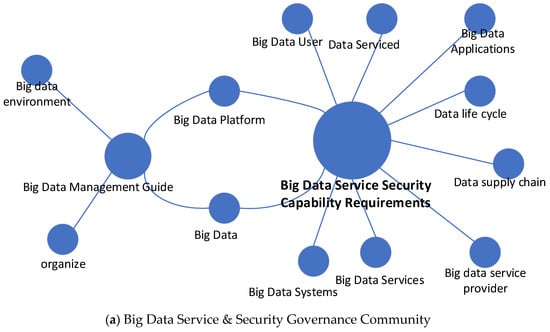

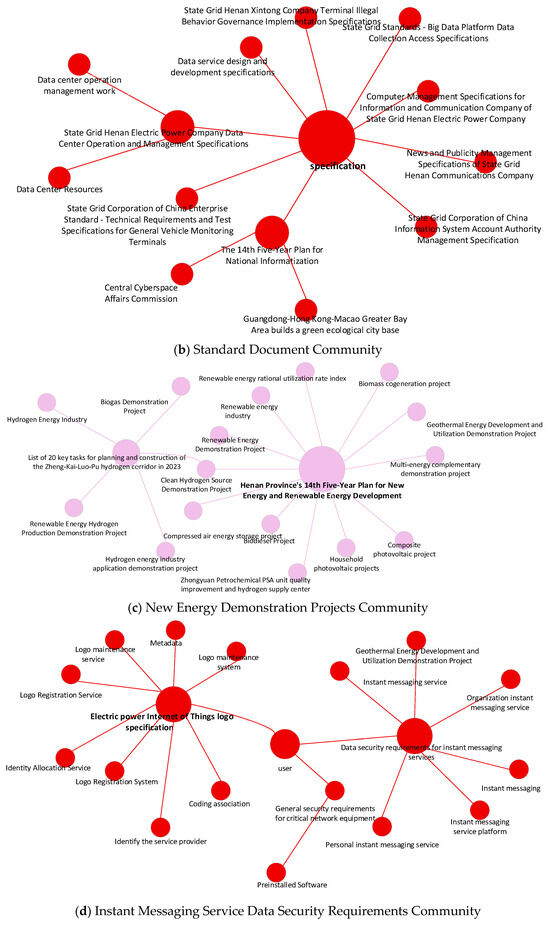

To verify the structural validity of Louvain-based community detection in the energy-policy knowledge graph, we visualize several representative communities in Figure 7. Different colors represent distinct communities, and node size encodes normalized degree centrality. The visualization demonstrates clearly clustered structures: key policy clauses, regulatory departments, and major regulations consistently appear near the community centers, community centers correspond to semantically important entities, entities with strong structural importance in the graph tend to play significant roles in downstream question answering.

Figure 7.

Partial Community Partitioning. Node color denotes community assignment and node size denotes normalized degree centrality. (a) Big Data Service & Security Governance Community. (b) Standard Document Community. (c) New Energy Demonstration Projects Community. (d) Instant Messaging Service Data Security Requirements Community.

The community structure revealed by the Louvain algorithm provides meaningful insights into the semantic organization of the knowledge graph. As shown in Figure 7a, the large-scale big-data knowledge graph is clustered into two major communities. The first community is centered around “Big Data Services Requirements”, bringing together nodes such as “Data Supply Chain,” “Big Data Users,” and “Big Data Applications,” which collectively reflect the domain’s emphasis on service demands and application-driven requirements. The second community is organized around “Big Data Security Requirement Guide,” connecting nodes such as “Big Data Environment” and “Organize,” highlighting themes related to security standards and environmental constraints in big-data systems. Notably, “Big Data Platform” lies at the intersection of these two communities, indicating its bridging role between service-oriented requirements and security governance. This community structure reveals two primary thematic directions in big-data research and their inherent connections, providing structural support for downstream semantic parsing and knowledge-base construction.

The results in Table 6 indicate that the distribution of communities and degree centrality is highly consistent with the underlying semantics of energy-policy documents: important policy clauses and key institutions tend to occupy central positions within their communities. These central nodes play a more critical role in question answering, providing strong evidence for determining the semantic consistency of entities. By leveraging both community structure and centrality information, the proposed weighting strategy effectively highlights core entities in the knowledge graph, thereby improving entity disambiguation accuracy and enhancing the precision of structured retrieval.

Table 6.

Degree Centrality of Some Community Nodes.

4.3. Question Repository

To address noise issues common in energy-policy text retrieval—such as long text chunks, inconsistent keyword usage, and large discrepancies between users’ queries and policy wording—this study introduces a Question Repository K as an intermediate retrieval layer to achieve more robust text retrieval. The core workflow is as follows:

- Latent Question Generation

Given a corpus C = {D1, D2, …, Dn}, where each text chunk Di contains a paragraph of content with a unique identifier Mi, an instruction-following large language model is used to generate a set of latent questions{q1, q2, …, qn} for each text chunk Di. These generated questions capture the key semantics of the text chunk and can be viewed as “the most likely questions that one could ask about this content.”

Semantic deduplication is then applied to remove paraphrased variants while retaining semantically representative questions.

- 2.

- Constructing the Question Repository K

All latent questions are aggregated into the Question Repository K = {q1, q2, …, qn}. Each question qi is encoded into an embedding vector vi ∈ Rd using a unified pretrained encoder. These embeddings capture semantic meaning in high-dimensional space and allow for content-based similarity matching. A key–value index is then constructed: key: embedding vector vi, value: the identifier Mi of the corresponding text chunk

- 3.

- Query-to-Block Retrieval via Question Matching

The user query Q is encoded using the same encoder to obtain vector V. Retrieval is performed via cosine similarity:

Using a Top-k strategy, the top three most similar latent question embeddings vi are selected. Through the reverse index mapping, these embeddings are mapped back to their corresponding text chunks vi→Di. The resulting text chunks are treated as the non-structured contextual evidence for subsequent answer generation.

4.4. Semantic Parsing Retriever

The SPR module converts a natural-language question into a structured query form and retrieves relevant triples from the domain knowledge graph, providing structured evidence for the RAG system. It consists of four stages: logical form generation, entity linking, relation matching, and triple retrieval.

When a question Q is submitted, it is passed to the SPR module, which contains a LoRA-fine-tuned LlaMa2-7b model. After fine-tuning, the model partially acquires the ability to perform semantic parsing, converting natural language questions into logical forms. In this study, the fine-tuned LlaMa2-7b model parses the question Q into a logical form S (S-expression), where S represents a structured mapping of entities e and relations r in Q. This is followed by entity linking and relation matching.

First, entity linking is performed. Entities e are extracted from the logical form S. SimCSE is used to compute the semantic similarity between e and each entity ei in the entity set E = {e1, e2, …, en}. This similarity is multiplied by the corresponding entity disambiguation weight to obtain a score. The top k1 scores are selected to form a candidate entity set E’ = {e’1, e’2, …, e’k1}. The entities e in the logical form S are then replaced by the identifiers ID of the candidate entities e’i, linking them to the knowledge base.

Next, relation retrieval is conducted. For each candidate entity e’i the knowledge base is queried to retrieve a set of candidate relations R = {r1, r2, …, rn}. SimCSE computes the semantic similarity between the relation r in S and each ri ∈ R. The top k2 relations are selected to form a candidate relation set R’ = {r’1, r’2, …, r’k2}. The relations r in S are replaced by the candidate relations r’j, producing multiple new logical forms S″.

Finally, each S′′ is converted into an executable SPARQL query to retrieve entities x from the knowledge base that are relevant to question Q. The associated triples T= ⟨e’i, r’j, x⟩ are output. During execution, only the first matching entity is considered; if no results are found, the triple T is set to empty. See for Algorithm 1 the detailed process.

The triples T = ⟨e’i, r’j, x⟩ obtained from the SPR module are first converted into natural language text S_KG. This text is then concatenated with the context (text chunks Di), producing a dual-source context. Finally, the newly generated context along with the question Q is fed into the generator (large language model) to produce the response.

| Algorithm 1. SPR Module for Retrieving Related Triples. |

| Input: Natural-language question Q Output: List of associated triples T = {<e’i,r’j,x>} function SEMANTICPARSE(Q) S ← LLaMA2-7BLoRA(Q) return S end function function ENTITYLINK(S) Extract entity e from S for each candidate entity ek ∈ E do scorek ← SimCSE(e, ek) * disambig-weightk end for Select top-k1 entities to form E’= {e’1, …, e’k1} return E’ end function function RELATIONRETRIEVE(e’i) Fetch relation set R = {r1, …, rn} linked to e’i from KB for each rm ∈ R do simm ← SimCSE(r, rm) end for Select top-k2 relations to form R’= {r’1, …, r’k2} return R’ end function function BUILDSPARQL(S,e’i,r’j) Replace e with ID of e’i and r with r’j in S to obtain S’’ q ← ConvertToSPARQL(S’’) return q end function function EXECUTEONESHOT(q) x ← SPARQLfirst-hit(q, KB) return x end function Main: S ← SEMANTICPARSE(Q) E’ ← ENTITYLINK(S) Initialize empty list T for each e’i ∈ E’ do R’ ← RELATIONRETRIEVE(e’i) for each r’j ∈ R’ do q ← BUILDSPARQL(S,e’i,r’j) x← EXECUTEONESHOT(q) Append< e’i,r’j,x> to T end for end for return T |

5. System Evaluation

5.1. Dataset and System Configuration

Existing public RAG datasets—such as HotpotQA, MuSiQue, and MS-MARCO—typically follow a “question–answer pair + original documents” format. They do not include queryable triples and lack structured knowledge suitable for semantic parsing retrieval (SPR). Therefore, they cannot support our experimental requirements for the electricity-policy domain + dual-source retrieval (text retrieval + KG retrieval). Moreover, no large-scale public dataset or domain knowledge graph exists for electricity-policy documents. To address this gap, we construct a complete experimental dataset from policies to knowledge graphs and then to QA pairs, enabling full-spectrum evaluation of SPR-RAG.

The dataset is provided by the Economic and Technical Research Institute of State Grid Henan Electric Power Company, containing more than 1200 electricity-policy documents. These documents are used both to build the domain knowledge graph and to generate the RAG dataset.

To obtain high-quality QA pairs, we adopt a dual-channel strategy combining real-world queries and expert-assisted generation: (1) Real QA collection: Approximately 1000 real questions were collected from domain experts to ensure authenticity and domain fidelity. (2) Expert-assisted QA generation: Based on the 1200 policy documents, researchers and LLMs collaboratively created ~4000 high-quality additional QA pairs to expand coverage of policy clauses and operational scenarios. Together, these two parts form a domain-specific electricity-policy RAG dataset with broad coverage and strong professional relevance, suitable for industrial-level evaluation.

For retrieval, we adopt the pretrained embedding model dpr-ctx_encoder-single-nq-base from HuggingFace due to its strong performance in the MTEB benchmark. For triple extraction within the KGPipeline, we use Qwen1.5-32B. For semantic parsing within SPR, we use a LoRA-fine-tuned Llama2-7B. Finally, the answer generator is the open-source Llama3-8B-Instruct, chosen for its robust instruction-following ability and generalization to policy QA tasks.

These components together form the complete experimental environment for evaluating SPR-RAG.

5.2. Evaluation Metrics

To comprehensively assess SPR-RAG’s performance in electricity-policy QA, we adopt two complementary evaluation systems: RAGAS, a dedicated evaluation framework for retrieval-augmented generation [32], and ROUGE, a widely used text-generation quality metric. Together, they evaluate retrieval quality, factual grounding, semantic correctness, and linguistic coherence.

- RAGAS Evaluation

RAGAS is one of the most representative evaluation frameworks for RAG systems. It evaluates model performance along three dimensions: answer relevance, context quality, and factual faithfulness. In this study, we use three core metrics: Faithfulness, Answer Relevance, and Context Relevance.

Faithfulness measures whether the generated answer is strictly grounded in the retrieved context without introducing hallucinated content. Higher scores indicate better factual consistency and more reliable grounding.

Answer Relevance measures the semantic alignment between the generated answer and the user question. It reflects whether the answer is truly addressing the question rather than drifting into irrelevant content.

Context Relevance evaluates how well the retrieved context aligns with the question and how effectively the model uses the retrieved information. Higher scores suggest more precise and relevant retrieval inputs for generation.

- 2.

- ROUGE Score

ROUGE (Recall-Oriented Understudy for Gisting Evaluation) measures the overlap between generated text and reference text. It is widely used in summarization and QA tasks. We adopt ROUGE-1, ROUGE-2, and ROUGE-L.

ROUGE-1 evaluates unigram overlap between generated answers and references. Higher scores reflect better information coverage.

ROUGE-2 measures bigram overlap, reflecting the model’s ability to generate coherent phrases and locally consistent linguistic structures.

ROUGE-L evaluates the longest common subsequence between generated and reference answers. Compared with ROUGE-1/2, it better captures global semantic structure and the logical organization of the generated content.

Although ROUGE is not specifically designed for RAG tasks, it complements RAGAS by assessing linguistic fluency, semantic organization, and text quality—providing a comprehensive evaluation when combined with the grounding-focused RAGAS metrics.

5.3. Performance Comparison and Discussion

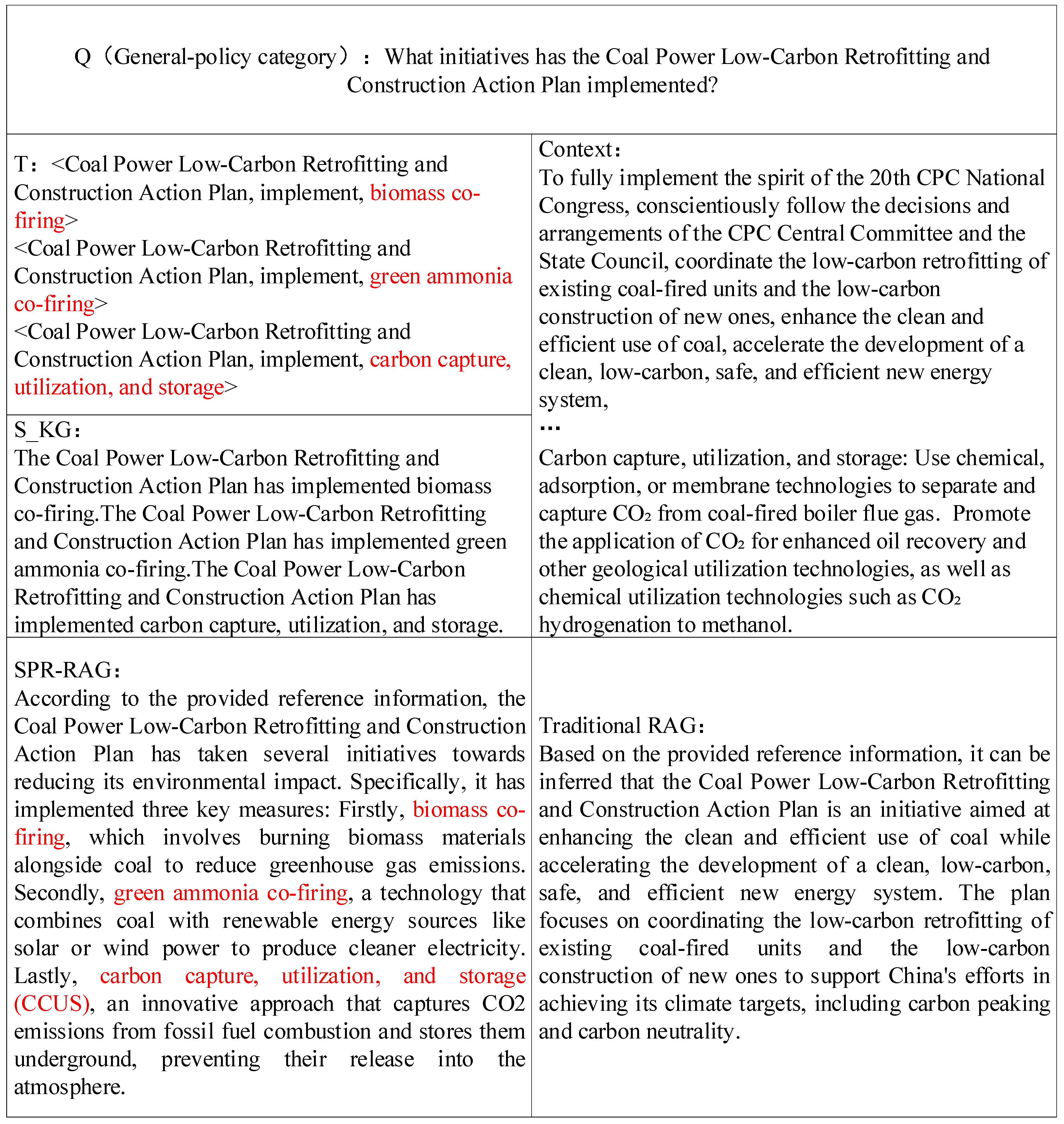

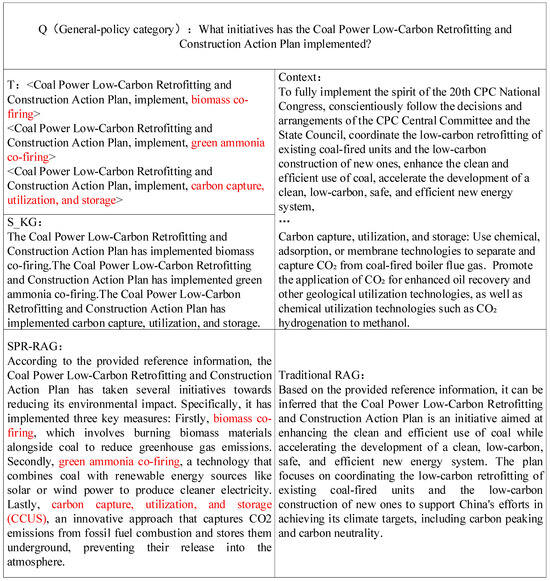

To objectively evaluate the performance of SPR-RAG in electricity-policy question answering, we compare it with four baseline systems: GraphRAG, LightRAG, Traditional-RAG, and Naive-KG-RAG. Traditional-RAG adopts standard vector-based text retrieval. Naive-KG-RAG augments Traditional-RAG by converting all triples into natural-language sentences and performing vector retrieval over these textualized triples. GraphRAG and LightRAG rely on LLM-generated graph structures for retrieval. The experimental results are presented in Table 7, and Figure 8 demonstrates a qualitative comparison between SPR-RAG and Traditional-RAG.

Table 7.

Performance Metrics of SPR-RAG vs. Baseline RAG Models.

Figure 8.

Comparison of SPR-RAG and Traditional RAG Results.

SPR-RAG achieves the best performance across most evaluation metrics, with especially significant improvements in Faithfulness and Context Relevance, two metrics crucial for high-stakes policy QA. These improvements indicate that SPR-RAG delivers superior text generation quality, semantic matching, and factual accuracy. In terms of Faithfulness, SPR-RAG outperforms the best-performing baseline, LightRAG, by 1.44%, and exceeds Traditional-RAG by 5.26%, demonstrating a substantial reduction in hallucination and stronger grounding on verifiable evidence. For Context Relevance, SPR-RAG surpasses GraphRAG by 1.50% and outperforms Traditional-RAG by 5.96%, indicating that SPR-RAG retrieves text chunks that are more semantically aligned with the user query Q, resulting in more accurate contextual grounding. Regarding Answer Relevance, SPR-RAG exhibits performance similar to that of other baselines. This outcome is expected because all systems use the same generator (Llama3-8B-Instruct), which ensures consistent answer style and quality. Although different architectures retrieve different contexts, they all provide essential key information, resulting in minimal variation in answer–question alignment. On ROUGE metrics, SPR-RAG and GraphRAG perform comparably, while both significantly outperform LightRAG and Traditional-RAG. This highlights SPR-RAG’s advantage in linguistic accuracy and information coverage during answer generation.

Electricity-policy documents contain numerous surface-identical but semantically distinct entities. For example, the term “Electricity Bureau” may refer to municipal, provincial, or national agencies. While these entities differ significantly in meaning, they share highly similar surface forms. When Naive-KG-RAG converts all triples into natural-language text and performs vector retrieval, the model becomes overly dependent on surface similarity. For instance: National Electricity Bureau—issued—Policy A”, “Municipal Electricity Bureau—issued—Policy B”. Although semantically unrelated, these sentences have near-identical lexical patterns. Their embeddings therefore become extremely close in vector space, causing incorrect retrieval and introducing noise. This greatly increases the likelihood of hallucination during answer generation. In contrast, SPR-RAG’s semantic parsing retrieval employs logic-form analysis, entity linking, relation matching, and graph-structured disambiguation, allowing it to distinguish among semantically different entities that share similar textual forms. The experimental results confirm this: SPR-RAG improves Faithfulness by 5.56% over Naive-KG-RAG and achieves higher performance across all ROUGE metrics, demonstrating stronger robustness in environments with dense homonymous entities.

Overall, SPR-RAG integrates structured triple retrieval, graph-based entity disambiguation, and question-repository-driven semantic matching to build a dual-source (structured + unstructured) contextual retrieval framework. This design substantially enhances factual accuracy, semantic relevance, and generation quality compared with mainstream RAG models. In particular, the advantage becomes more pronounced in: Hallucination suppression, Semantic understanding of policy clauses, Handling homonymous entities, Retrieving context aligned with real administrative hierarchies.

These strengths position SPR-RAG as an effective and reliable solution for high-stakes, domain-specific electricity-policy question answering.

5.4. Ablation Study

This section discusses the following questions:

Q1: Are the core components of SPR-RAG—namely the SPR module and the question-repository module K—effective?

Q2: Does the community-based optimization strategy improve the accuracy of the structured triple retrieval performed by SPR?

To address Q1, four configurations are evaluated: Baseline RAG (vector retrieval only), SPR-RAG w/o K (only the SPR module), SPR-RAG w/o SPR (only the question-repository module K), and Full SPR-RAG.

Table 8 reports the performance under different settings. The results show that adding either SPR or K alone yields substantial improvements over the baseline RAG. Specifically, ROUGE-1 increases by 2.9–4.2 points, ROUGE-2 by 4.3–5.0 points, Faithfulness by 3–5 points, and Context Relevance by 4–5 points. This demonstrates that SPR and K independently contribute to better generation quality, semantic coverage, and factual consistency. The full model achieves the highest scores across ROUGE-1/2/L, Faithfulness, and Context Relevance, showing that the two components are complementary rather than interchangeable.

Table 8.

Comparison of the Impact of Different SPR-RAG Components on Performance Metrics.

From the ablation results, when the SPR module is removed and only the question-repository module K is retained, Faithfulness increases significantly by 4.7% and Context Relevance increases by 4.6%. This indicates that the primary contribution of the K module lies in enabling the model to better utilize the retrieved documents, thereby reducing hallucinations and improving factual accuracy. In essence, the K module enhances the model’s ability to “retrieve the correct information and use it correctly,” reinforcing factual consistency and context utilization while reducing off-topic responses and fabricated content. Therefore, the K module mainly improves Faithfulness, making it a key mechanism for hallucination suppression. When the question-repository module K is removed and only the SPR module is retained, ROUGE-1/2/L all show substantial improvements (especially ROUGE-2). Although Faithfulness also improves, the gain is slightly lower than that achieved by the K module. This suggests that the SPR module mainly functions to “organize the answer structure, increase information coverage, and make the generation more tightly grounded in the retrieved context.” By injecting structured knowledge-graph triples during generation, SPR enhances the model’s understanding and reasoning over policy background information. Consequently, the SPR module primarily improves generation quality and structural completeness (as reflected in the ROUGE metrics). The complete model achieves the highest scores across all metrics, indicating that SPR and K are not redundant but rather complementary. The K module provides highly relevant text, while SPR supplies precise structured knowledge. Together, they jointly reduce hallucinations and improve semantic alignment and context coherence.

For Q2, to verify whether the community-based optimization strategy truly improves the accuracy of structured retrieval, we compare it with the traditional semantic-parsing retrieval method. As shown in Table 9, the SPR module enhanced by the community-detection algorithm achieves improvements of 3.8% in F1 score, 3.9% in Hits@1, and 3.8% in Accuracy compared with the unoptimized SPR module. These results indicate that community detection successfully identifies high-impact central nodes in the knowledge graph; the degree-centrality–based weight update significantly enhances the stability of entity linking; and the optimized SPR module more easily retrieves semantically correct triples, especially in challenging scenarios involving homonymous entities or divergent relations. Therefore, the community-based optimization mechanism effectively strengthens the structured retrieval component and constitutes an important source of performance improvement for SPR-RAG.

Table 9.

Comparison of SPR with Other Retrieval Methods.

5.5. Significance Analysis

To examine whether the performance improvements in SPR-RAG over baseline models and its ablated variants are statistically significant—and given that the metric distributions do not satisfy normality assumptions—we conducted Wilcoxon signed-rank tests on the generated outputs for all systems using the same set of questions. The Benjamini–Hochberg (BH) procedure was applied for multiple-hypothesis correction to control the overall false discovery rate. The significance threshold was set at padj < 0.05, where padj denotes the Benjamini–Hochberg (BH) adjusted p-value. The statistical results are presented in Table 10.

Table 10.

Summary of Statistical Significance (Wilcoxon + BH correction, padj < 0.05).

For Faithfulness, SPR-RAG shows significant improvements over GraphRAG, LightRAG, and SPR-RAG (w/o K), while the difference with SPR-RAG (w/o SPR) is not significant. This indicates that the question-repository module (K) is the primary contributor to Faithfulness improvements, mainly by reducing erroneous retrievals and increasing the accuracy of evidence. Although the SPR module also improves Faithfulness, its effect is partially dominated by the K module; thus, the difference becomes non-significant when SPR alone is removed.

For Context Relevance, SPR-RAG achieves significant improvements over all models except LightRAG. This suggests that both the SPR module and the K module effectively enhance the system’s ability to utilize retrieved documents. LightRAG benefits from its graph-structured representation, which explains the absence of significant difference on this metric.

For Answer Relevance, SPR-RAG does not exhibit statistically significant differences against any comparison system. This indicates that SPR-RAG’s advantage does not lie in “whether the model answers the question,” but rather in how truthful and context-aligned the answer is.

For the ROUGE metrics, SPR-RAG shows significant improvements over LightRAG (ROUGE-1/2/L all significant), and over SPR-RAG (w/o SPR) and SPR-RAG (w/o K). The differences with GraphRAG and SPR-RAG (w/o K) are not significant. Combined with the ablation results, this suggests that the SPR module is the main contributor to improvements in generation quality (coverage, phrase-level coherence, and global structural organization), whereas the K module has limited influence on linguistic structure and mainly contributes to factuality and context alignment rather than content organization.

Overall, the statistical analysis clearly validates the functional roles of the two modules: The K module primarily improves Faithfulness and Context Relevance by reducing hallucinations and strengthening the system’s ability to use retrieved evidence correctly. The SPR module primarily improves the ROUGE family of metrics by enhancing answer completeness, fluency, and structural coherence. With both modules combined, SPR-RAG achieves statistically significant improvements over baseline systems on multiple dimensions, demonstrating that the full system provides the best overall performance and stability.

5.6. Cost Analysis

Table 11 summarizes the average computational cost of the four systems under identical hardware conditions (single RTX 3090Ti-24GB and Llama3-8B). The GPU memory usage during inference is nearly identical across all methods (approximately 16.5 GB), as it is primarily dominated by the Llama3-8B model; thus, the four systems are essentially in the same memory class.

Table 11.

Cost comparison among different RAG systems.

However, the index construction (offline preprocessing) exhibits substantial differences. GraphRAG relies on large language models for entity extraction, relation extraction, and community-level summarization, resulting in the highest indexing cost (approximately 10 h). Similarly, LightRAG constructs pseudo-graphs using LLMs and requires several hours (approximately 3 h). In contrast, SPR-RAG relies on a pre-constructed ontology-guided knowledge graph. The knowledge graph is generated once offline and does not require large model inference during deployment; therefore, SPR-RAG introduces nearly zero online indexing cost.

During inference, LightRAG achieves the shortest response time (2.58 s) due to its lightweight vector-retrieval pipeline. GraphRAG requires graph-based community retrieval and contextual aggregation, resulting in slightly longer time (4.18 s). SPR-RAG incurs additional latency from the semantic parsing retrieval step, leading to a marginally higher inference time (4.98 s). Nonetheless, this overhead is substantially lower than the improvements it yields in Faithfulness and Context Relevance.

Overall, SPR-RAG improves the final answer quality without increasing GPU memory consumption, and avoids the heavy indexing cost associated with GraphRAG and LightRAG. This demonstrates its superior engineering deployability and domain adaptability.

6. Conclusions

It is important to emphasize that the design goal of SPR-RAG is not to pursue extreme performance on open-domain benchmarks, but to develop an interpretable, transferable, and practically deployable RAG system for high-risk, long-document, and strongly structured vertical domains such as power-policy analysis. Accordingly, the primary contribution of this work lies in proposing a complete “Text → Knowledge Graph → RAG” engineering workflow and validating its applicability and reliability on real industrial data, rather than pursuing large numerical gains alone. From the perspective of the experimental results and system implementation, the main conclusions of this paper are as follows:

- The SPR module significantly improves the truthfulness and relevance of RAG systems. By retrieving structured triples from the knowledge graph, SPR-RAG achieves notable improvements in Faithfulness and Context Relevance: +1.44% over the best-performing baseline and +5.26% over Traditional RAG for Faithfulness; +1.50% over the best baseline and +5.96% over Traditional RAG for Context Relevance. This demonstrates that structured evidence effectively suppresses hallucinations and strengthens verifiability. In addition, the SPR module is plug-and-play and can be combined with knowledge graphs from different domains.

- Community-based entity disambiguation effectively improves the accuracy of structured retrieval. The community detection algorithm identifies influential nodes in the knowledge graph and, combined with degree-centrality normalization, produces more robust entity weights.

- The question-repository module (K) substantially enhances the quality of unstructured retrieval. By transforming document chunks into latent questions, the K module enables retrieval via semantic question matching rather than surface-level vector similarity.

- This work implements a transferable “Text → KG → RAG” engineering paradigm. Starting from raw policy documents, a complete knowledge-processing pipeline is constructed, including KG building, disambiguation optimization, question-repository generation, and RAG dataset construction. The workflow is independent of public datasets and can be adapted to any knowledge-intensive domain.

In summary, SPR-RAG combines structured and unstructured evidence to deliver a robust and highly trustworthy solution for complex domain-specific QA tasks. It effectively reduces hallucinations, demonstrating strong practical value for industrial applications.

7. Limitations and Future Work

Despite its strong performance in Faithfulness and Context Relevance and its ability to mitigate information dilution and hallucination in the power-policy domain, SPR-RAG still has several limitations. First, the SPR module depends on a predefined ontology and a high-quality domain knowledge graph. This dependency may reduce model applicability in domains where ontology resources are incomplete or unavailable. The semantic parser may also produce imperfect logical forms when handling complex or ambiguous queries, which could degrade structured retrieval performance. Second, as the knowledge graph grows in scale or requires frequent incremental updates, the cost of logical querying and triple-to-text conversion may increase, posing higher efficiency requirements for real-world deployment. Third, the current dual-source context (structured triples + unstructured text chunks) adopts a static concatenation strategy, without dynamically weighting or optimizing the fusion for different tasks.

Future work will focus on automated ontology extension, improved semantic parsing robustness, dynamic KG update mechanisms, more efficient triple indexing structures, and adaptive multi-source context fusion. Additionally, we plan to integrate SPR-RAG with multi-agent systems to support more advanced reasoning tasks such as policy comparison, contradiction detection, and fact verification, further enhancing its generalizability, robustness, and engineering applicability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W.; methodology, Y.W. and T.X.; software, T.X.; validation; writing—original draft preparation, T.X.; writing—review and editing, Y.W.; supervision, Y.Z.; funding acquisition, Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2024M751481), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12202210), the Startup Foundation for Introducing Talent of Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology (Grant No. 2022r095), and the Open Fund Program of State Key Laboratory of Trauma and Chemical Poisoning (Grant No. SKL0202403).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this study, the authors used OpenAI GPT-3.5 (March 2024 version) to generate potential questions from the corpus and build question bank K, and Alibaba Qwen1.5-32B to extract triples from the text. The authors reviewed, validated, and edited all AI-generated outputs and take full responsibility for the final content of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language models are few-shot learners. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Virtual, 6–12 December 2020; Volume 33, pp. 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F.; Zhao, P.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Garg, M.; Lin, Q.; Rajmohan, S.; Zhang, D. Empower large language model to perform better on industrial domain-specific question answering. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.11541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandpal, N.; Deng, H.; Roberts, A.; Wallace, E.; Raffel, C. Large language models struggle to learn long-tail knowledge. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; PMLR: 2023. pp. 15696–15707. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Yang, Z.; Meng, F.; Li, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y. An empirical study of catastrophic forgetting in large language models during continual fine-tuning. IEEE Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2025, 33, 9459–9474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Garner, P.N. Bayesian parameter-efficient fine-tuning for overcoming catastrophic forgetting. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2024, 18, 1509–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koloski, B.; Škrlj, B.; Robnik-Šikonja, M.; Pollak, S. Measuring Catastrophic Forgetting in Cross-Lingual Classification: Transfer Paradigms and Tuning Strategies. IEEE Access 2025, 10, 3473–3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wu, H.; Cheung, Y.; Cao, J.; Yu, H.; Zhang, Y. Mitigating Forgetting in Adapting Pre-trained Language Models to Text Processing Tasks via Consistency Alignment. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference, Sydney, Australia, 28 April–2 May 2025; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 3492–3504. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, B.; Saha, U. Enhancing International Graduate Student Experience through AI-Driven Support Systems: A LLM and RAG-Based Approach. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Data Science and Its Applications (ICoDSA), Bali, Indonesia, 10–11 July 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, P.; Perez, E.; Piktus, A.; Petroni, F.; Karpukhin, V.; Goyal, N.; Küttler, H.; Lewis, M.; Yih, W.-T.; Rocktäschel, T.; et al. Retrieval-augmented generation for knowledge-intensive NLP tasks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Virtual, 6–12 December 2020; Volume 33, pp. 9459–9474. [Google Scholar]

- Neelakantan, A.; Xu, T.; Puri, R.; Radford, A.; Han, J.M.; Tworek, J.; Yuan, Q.; Tezak, N.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; et al. Text and code embeddings by contrastive pre-training. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.10005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Gao, X.; Jia, K.; Pan, J.; Bi, Y.; Dai, Y.; Sun, J.; Wang, H. Retrieval-augmented generation for large language models: A survey. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.10997. [Google Scholar]

- Bender, E.M.; Gebru, T.; McMillan-Major, A.; Shmitchell, S. On the dangers of stochastic parrots: Can language models be too big? In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Virtual, 3–10 March 2021; pp. 610–623. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, L.; Ma, X.; Lin, J.; Callan, J. Precise Zero-Shot Dense Retrieval without Relevance Labels. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Toronto, ON, Canada, 9–14 July 2023; Association for Computational Linguistics: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2023; pp. 4401–4414. [Google Scholar]

- Ghojogh, B.; Ghodsi, A. Attention Mechanism, Transformers, BERT, and GPT: Tutorial and Survey. HAL Preprint, 2020, hal-04637647. Available online: https://hal.science/hal-04637647/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Qin, H.; Gong, C.; Li, Y.; Gao, X.; El-Yacoubi, M.A. Label enhancement-based multiscale transformer for palm-vein recognition. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Han, J.; Liu, C.; Zhou, A.; Lu, P.; Qiao, Y.; Gao, P. LLaMA-adapter: Efficient fine-tuning of large language models with zero-initialized attention. In Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, Vienna, Austria, 7–11 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Ruan, S.; Qin, H.; Deng, S.; El-Yacoubi, M.A. Transformer-based defense GAN against palm-vein adversarial attacks. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2023, 18, 1509–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröhling, L.; Zubiaga, A. Feature-based detection of automated language models: Tackling GPT-2, GPT-3, and Grover. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2021, 7, e443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briskilal, J.; Subalalitha, C.N. An ensemble model for classifying idioms and literal texts using BERT and RoBERTa. Inf. Process. Manag. 2022, 59, 102756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkurt, C. Comparative Analysis of State-of-the-Art Q&A Models: BERT, RoBERTa, DistilBERT, and ALBERT on SQuAD v2 Dataset. Chaos Fractals 2024, 1, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.; Liu, Y.; Goyal, N.; Ghazvininejad, M.; Mohamed, A.; Levy, O.; Stoyanov, V.; Zettlemoyer, L. BART: Denoising sequence-to-sequence pre-training for natural language generation, translation, and comprehension. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.13461. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Ruder, S.; Sil, A. Multi-domain multilingual question answering. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing: Tutorial Abstracts, Punta Cana, Dominican Republic & Online, 10–11 November 2021; pp. 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Muennighoff, N.; Tazi, N.; Magne, L.; Reimers, N. MTEB: Massive text embedding benchmark. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.07316. [Google Scholar]

- Edge, D.; Trinh, H.; Cheng, N.; Bradley, J.; Chao, A.; Mody, A.; Truitt, S.; Metropolitansky, D.; Ness, R.O.; Larson, J. From local to global: A graph RAG approach to query-focused summarization. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.16130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Xia, L.; Yu, Y.; Ao, T.; Huang, C. Lightrag: Simple and fast retrieval-augmented generation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.05779. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Zhong, N.; Huang, X. Knowledge retrieval (KR). In Proceedings of the IEEE/WIC/ACM International Conference on Web Intelligence (WI’07), Fremont, CA, USA, 2–5 November 2007; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 729–735. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Yu, J.; Tang, J.; Tang, J.; Li, C.; Chen, H. Subgraph retrieval enhanced model for multi-hop knowledge base question answering. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.13296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguz, B.; Chen, X.; Karpukhin, V.; Peshterliev, S.; Okhonko, D.; Schlichtkrull, M.; Gupta, S.; Mehdad, Y.; Yih, S. Unik-QA: Unified representations of structured and unstructured knowledge for open-domain question answering. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2012.14610. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.Z.; Min, S.; Iyer, S.; Mehdad, Y.; Yih, W.-T. Efficient one-pass end-to-end entity linking for questions. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.02413. [Google Scholar]

- Es, S.; James, J.; Espinosa-Anke, L.; Schockaert, S. Ragas: Automated Evaluation of Retrieval Augmented Generation. In Proceedings of the 18th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: System Demonstrations, St. Julian’s, Malta, 17–22 March 2024; Association for Computational Linguistics: St. Julian’s, Malta, 2024; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).