Abstract

We present an intelligent, non-intrusive framework to enhance the performance of Symmetric Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics (SSPH) for elliptic partial differential equations, focusing on the linear and nonlinear Poisson equations. Classical Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics methods, while meshfree, suffer from discretization errors due to kernel truncation and irregular particle distributions. To address this, we employ a machine-learning-based residual correction, where a neural network learns the difference between the SSPH solution and a reference solution. The predicted residuals are added to the SSPH solution, yielding a corrected approximation with significantly reduced errors. The method preserves numerical stability and consistency while systematically reducing errors. Numerical results demonstrate that the proposed approach outperforms standard SSPH.

1. Introduction

Numerical solutions to partial differential equations (PDEs) are essential in various engineering and scientific applications [1,2,3]. Traditional mesh-based methods, such as the Finite Element Method (FEM), discretize the domain into elements connected by nodes, facilitating the approximation of solutions [4]. While FEM is highly effective for problems with well-defined geometries, it faces challenges when dealing with complex, evolving, or deforming domains. These challenges include difficulties in mesh generation in many cases, including for irregular or curved boundaries [5], in addition to the need for frequent remeshing when it comes to dynamic simulations [6]. To address these limitations, many meshless methods have been developed [7,8,9]. These methods do not rely on a predefined mesh and can naturally handle large deformations and complex geometries, making them particularly advantageous for problems involving free surfaces and moving boundaries [10,11].

Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics (SPH) is a fully meshfree particle method originally introduced in astrophysics and later extended to fluid mechanics, structural mechanics, electromagnetics, and biomedical applications [12,13,14,15]. SPH represents a physical domain using moving particles and employs kernel functions to approximate differential operators, which enable solving partial differential equations on complex or irregular domains without structured meshes. This construction technique makes SPH particularly suitable for problems involving free surfaces, large deformations, and fluid–structure interactions, where conventional finite difference or finite element methods face challenges [16,17]. In engineering practice, SPH has been successfully applied to impact dynamics, plasma simulations, and multiphase flows [18,19].

Classical SPH provides flexibility in handling complex domains, yet it exhibits notable drawbacks in the same way as other meshless approaches. The method suffers from numerical instabilities and reduced accuracy in derivative approximation and particularly near boundaries or when the particle distribution is coarse [7]. These instabilities primarily manifest as tensile instability (or particle clumping) and inconsistency errors, which arise from the use of truncated kernels and irregular particle positioning, leading to substantial discretization error and potentially spurious oscillations in the solution [20,21]. Several improved formulations have been developed in order to overcome some of these challenges. In [22], the Moving Least Squares Particle Hydrodynamics (MLSPH) method has been developed to improve accuracy in derivative approximations. The Symmetric Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics (SSPH) method improves numerical stability through the symmetrization of kernel gradients [23,24]. This approach guarantees consistency, suppresses spurious pressure oscillations, and removes the requirement for a differentiable kernel function [25]. Additional developments include the use of higher-order kernels, corrected SPH variants, and adaptive particle refinement strategies [26]. Despite these advances, discretization errors continue to present challenges in problems demanding high precision, such as elliptic partial differential equations and steady-state diffusion–reaction systems [27].

Machine learning (ML) has recently emerged as a promising tool to improve numerical methods. Data-driven corrections can complement numerical approximations by learning residual patterns between the numerical solution and any exact or reference solution [28]. ML models, including neural networks, can model highly nonlinear error distributions in ways that traditional correction formulas come short. For SPH, the use of ML enables the residual errors in particle-based approximations to be systematically reduced without modifying the underlying physics-based discretization. These techniques are especially useful for problems where errors propagate across the domain and strongly affect solution quality. One example is engineering problems that can be formulated in terms of elliptic PDEs [29,30]. Motivated by physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) [31] and hybrid solvers that combine data-driven corrections with traditional numerical schemes [32,33], the integration of machine-learned residual correction into SSPH provides a promising direction for improving the accuracy of meshfree solvers.

In this work, we propose and implement an intelligent SSPH framework based on machine-learned residual correction for elliptic PDEs. In particular, our proposed solution framework is applied to the Poisson equation, which serves as the primary model problem. The Poisson equation serves as the canonical model problem for evaluating discretization accuracy in both mesh-based and meshfree numerical methods [34,35,36,37]. Because it is a steady-state, purely elliptic PDE, the numerical error initially stems entirely from spatial discretization, making it an ideal setting to isolate and study the intrinsic inconsistency of the SSPH operator. We also include nonlinear Poisson equations, demonstrating that the residual correction mechanism remains effective even in the presence of nonlinear source terms. Moreover, the Laplacian operator is a fundamental building block in a wide class of physical and multiphysics models—including incompressible Navier–Stokes, diffusion–reaction systems, and thermal conduction. Thus, developing and validating a residual-correction mechanism for the discretized Laplacian in both linear and nonlinear settings provides a methodological proof-of-concept that naturally extends to more complex PDEs where the Laplacian term appears as a core component or is solved implicitly.

First, we use the standard SSPH approximation to construct the particle-based discretization of the Laplace operator and compute the numerical solution. Next, a neural network residual correction is applied, trained on the difference between the SSPH approximation and the known exact solution. By introducing the coordinates and coarse SSPH solution as inputs, the network learns to predict and correct residual errors at interior points. We apply the proposed approach to a number of numerical examples involving the Poisson equation and demonstrate that the method substantially reduces the relative error and achieves notable accuracy improvements compared with standard SSPH. The ML correction step is non-intrusive, since it leaves the SSPH formulation unchanged and operates as a post-processing layer. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents one of the first efforts to directly integrate SSPH with machine-learning-based residual correction for elliptic partial differential equations. The core idea of this work lies in the integration of a lightweight, non-intrusive ML-based correction layer directly on top of SSPH. Unlike intrusive kernel-correction schemes or physics-informed networks, the proposed approach preserves the original SSPH operator and augments it with a data-driven residual model. This hybridization is not present in existing SPH literature and provides a flexible path to improving particle-based solvers using modern ML tools. The proposed framework establishes a foundation for extending intelligent SPH solvers to different domains and adaptive refinement strategies, as well as to practical engineering simulations that demand both robustness and high accuracy.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews the theoretical background of the classical and symmetric SPH formulations, kernel functions, and presents the model problem that we will use throughout the paper. Section 3 describes the machine-learned residual correction procedure and presents the overall algorithmic framework. Section 4 reports several numerical examples that demonstrate the accuracy and robustness of the proposed approach. Finally, Section 5 provides concluding remarks and discusses possible future extensions.

2. Theoretical Background

In this section, we review the theoretical foundations and fundamental equations underlying the SPH and SSPH methods. Several radial basis functions (RBFs) that satisfy the essential conditions for use as kernel functions are introduced, and their role within the SPH formulation is emphasized. We also present the Poisson equation as the model problem employed in this study to serve as the PDE framework for numerical implementation.

2.1. Classical SPH Approximation

SPH is a meshfree particle-based method that represents a continuum as a collection of moving particles each carrying mass, position, and field variables [13,16]. Particles interact with their neighbors through a smoothing kernel, which provides a weighted approximation of field quantities and their derivatives. Only particles within the kernel’s compact support contribute to the local approximation. Unlike traditional grid-based methods, SPH does not require a fixed mesh and relies entirely on these interpolation kernels to evaluate the field variables and their derivatives.

The theoretical foundation of SPH is based on the integral representation of functions. Let be a sufficiently smooth scalar function defined over . The kernel approximation is expressed as:

where W denotes the smoothing kernel and is the smoothing length that determines the size of the support domain. The kernel is required to satisfy the following properties [23]:

- Normalization:.

- Compact support: for , where k is a small integer, typically 2.

- Positivity: within its support.

- Smoothness: W is continuous and possesses continuous derivatives up to the required order.

An illustration of SPH compact support for a reference particle is shown in Figure 1, where the reference particle is marked in red and only particles inside the dashed circle in green are considered neighbors. Building on the integral representation presented in Equation (1), the domain is discretized by N particles, leading to the particle approximation given by

where values are the particle positions, and are the scalar value mass and density of particle j, and N is the total number of particles. The SPH approximation replaces the continuous integral operator with a particle sum weighted by the kernel function.

Figure 1.

Visualization of SPH compact support for a reference particle. Only particles inside the dashed circle contribute to the summation in Equation (2), which represents the discrete particle approximation of the integral formulation.

Spatial derivatives can be obtained by applying differential operators to the kernel function. The gradient operator is approximated as

Despite its versatility, standard SPH suffers from several numerical drawbacks, including a lack of consistency, kernel deficiency near boundaries, and poor accuracy in derivative approximation [38]. To overcome these issues, improved formulations such as the SSPH scheme were introduced. SSPH enforces antisymmetry in discrete operators, thereby improving stability, conservation, and accuracy. Following, we present the basic concepts related to the SSPH method.

2.2. SSPH Formulation

The SSPH approach is introduced to improve the stability and conservation properties of the standard SPH method. The main idea is to enforce antisymmetry in the discretization of differential operators, which enhances numerical stability and ensures exact conservation of linear momentum in particle interactions [38].

For a scalar field f, the gradient at particle i is approximated in SSPH as

where and are the mass and density of particle j, W is the smoothing kernel, and ensures antisymmetry between particle pairs .

For elliptic PDEs, the Laplacian operator plays a crucial role. In SSPH, the Laplacian is commonly discretized using the “product-rule” formulation:

which is widely used in solving diffusion and Poisson-type problems due to its enhanced stability and accuracy.

2.3. Kernel Functions

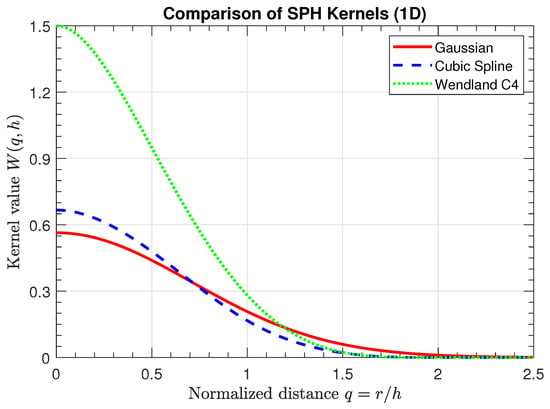

The kernel function plays a central role in determining the accuracy, stability, and convergence of SPH approximations. Various kernel functions have been proposed, and in this subsection, we focus on the most commonly adopted formulations.

The Gaussian kernel is one of the earliest and most widely recognized kernels in SPH, valued for its smoothness and analytical simplicity. The kernel function is given as

While infinitely smooth, the Gaussian kernel has infinite support, making it computationally expensive.

The cubic spline kernel is the most commonly adopted in SPH due to its compact support, computational efficiency, and good balance between accuracy and stability [39]. The kernel function is given as follows:

where and in the normalization constant for the cubic spline kernel is given as .

Now we move to introduce the Wendland kernels [24] for their advantages since they are compactly supported, strictly positive definite, and exhibit high smoothness. They are particularly effective in reducing particle clumping instabilities. In , the Wendland kernel is given by

with a normalization constant in . This kernel is used in the present study due to its favorable balance of stability and accuracy.

Figure 2 illustrates the shape of the three presented kernel functions in one dimension: Gaussian, cubic spline, and Wendland described by Equations (6), (7) and (8), respectively. For , the y-axis indicates that the Gaussian kernel attains the lowest peak value (≈0.56/h), the cubic spline peaks slightly higher (≈0.67/h), and the Wendland kernel reaches the highest value (1.5/h). The comparison highlights differences in smoothness and support size, which directly affect accuracy and computational cost in SPH formulations.

Figure 2.

Comparison of one-dimensional kernel functions (Gaussian, cubic spline, and Wendland ), showing their relative smoothness and compact support.

2.4. Model Problem

In this work, we use the Poisson equation with Dirichlet boundary conditions in as the model problem for elliptic PDEs since it represents a fundamental equation with well-understood analytical properties. The simplicity makes it an ideal test case for assessing the accuracy and efficiency of the proposed solution framework.

The linear Poisson equation can be given as

subject to Dirichlet boundary conditions

In the SSPH framework, the Laplacian in Equation (9) is discretized as in Equation (5), producing a system of linear equations of the form

where A is a coefficient matrix constructed from kernel-based particle interactions, is the vector of unknowns at particle positions, and incorporates the forcing term f and boundary conditions. Solving this system yields the discrete SSPH solution.

In addition to the linear Poisson problem, we also consider the nonlinear Poisson equation

subject to Dirichlet boundary conditions

Equation (12) is an elliptic, nonlinear PDE, since the highest-order operator is the Laplacian, and it appears with a positive coefficient. The lower-order nonlinear term does not affect ellipticity but introduces additional stiffness and nonlinearity into the solution process. Problems of this type arise frequently in reaction–diffusion systems, nonlinear electrostatics, heat sources proportional to the square of temperature, and various biological and chemical transport models.

Compared with the classical SPH Laplacian, which often uses second derivatives of the smoothing kernel or finite-difference-like approximations, the SSPH Laplacian employs a symmetric pairwise formulation Equation (5). This antisymmetric structure enhances stability, avoids the need for differentiable kernels, and provides improved conservation properties. While SSPH improves stability and conservation compared to classical SPH, discretization errors still arise from kernel truncation, irregular particle distributions, and the choice of support size. These limitations motivate advanced strategies such as the one we present in this work, where an integration with machine learning methods for residual correction is proposed.

The Poisson equation is widely regarded as the canonical model for studying consistency, stability, and approximation properties of both meshfree and mesh-based discretizations. For the linear Poisson equation, a steady-state problem, the primary source of error stems from spatial discretization within the SSPH framework. This characteristic allows the machine learning model to focus solely on learning and correcting these errors, providing a clear assessment of the residual correction’s effectiveness. Furthermore, the Laplacian operator in the Poisson equation forms a central component of many complex PDEs, such as the Navier–Stokes and heat equations. By successfully correcting the discretized Laplacian in this relatively simple setting, we establish a methodological proof of concept that can be directly extended to more complex systems where the Laplacian term is decoupled or solved implicitly. Similarly, including the nonlinear Poisson equation introduces additional stiffness and spatial variability, enabling the evaluation of the proposed framework under more challenging conditions that mirror real-world nonlinear elliptic problems. Together, the linear and nonlinear Poisson problems provide a systematic and rigorous benchmark for assessing the accuracy, stability, and generalizability of the SSPH ML residual correction approach.

3. Machine-Learned Residual Correction for SSPH

In this section, we present the steps of the developed solution structure based on SSPH and the ML-based correction criteria. At the beginning, we review the basic equations used to build the residual correction. Then, we present the solver steps and the algorithmic build-up for the method.

3.1. ML-Based Residual Correction Basics

In this subsection, we review some of the basic equations that are used to produce the residual corrected solution. The interested reader may turn to [28,40] for more detailed explanations.

Let us first consider the Poisson equation presented by Equation (9):

where is the differential operator (here for Poisson’s equation). The SSPH approximation yields a numerical solution that satisfies a perturbed problem

where is the discretization error induced by kernel truncation, irregular particle distributions, and finite resolution.

The exact error at particle i is given as

or equivalently, the residual

The ML-residual correction approximates (or ) using a regression model :

Thus, the corrected solution becomes

The training objective is

where is the training set and is a regularization parameter. This framework acts as a replacement model for the local truncation error, improving global accuracy without modifying the SSPH discretization.

The training dataset is constructed from interior nodes only, since boundary values are fixed by Dirichlet condition. A randomized permutation (70% training, 15% validation, and 15% testing) is used to ensure unbiased sampling. The residual targets are computed using the manufactured analytical solution for each example.

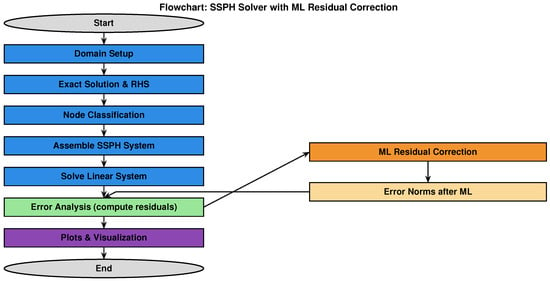

3.2. Framework Overview

In this subsection, we present the full construction of the proposed framework in a step-by-step manner. We start by building on the strengths of SSPH so that the approach incorporates a machine-learned residual correction to directly improve solution accuracy for elliptic partial differential equations. Unlike conventional stabilization or kernel-correction techniques, the ML component captures and compensates for complex, non-uniform numerical errors that standard methods cannot address. The correction is fully non-intrusive, preserving the physical fidelity and consistency of the SSPH solver. The framework is highly flexible, accommodating arbitrary particle distributions, adaptive refinement, and complex geometries. Figure 3 summarizes the workflow, with Steps 1–6 corresponding to Algorithms 1 and 2.

Figure 3.

Workflow of the SSPH solver with machine-learned residual correction.

The main steps are as follows.

- Discretize the computational domain into particles, defining spacing and support radius .

- Apply SSPH discretization: compute kernel weights, identify neighbors, and assemble the discrete Laplacian operator.

- Solve the sparse linear system for interior values, enforcing Dirichlet boundary conditions.

- Compute residuals at interior nodes (for supervised ML training).

- Train a feedforward neural network using as inputs and as targets. Normalize data to stabilize learning.

- Predict corrections and compute the corrected solution .

While the current methodology mostly relies on an analytical solution for validation of the results in Section 4, Section 4.1 demonstrates that the proposed framework remains fully applicable when no exact solution is available. In such cases, a high-fidelity numerical approximation, such as a fine-mesh FEM computation or a highly refined SSPH solution, serves as a practical surrogate for the true solution and provides the residual needed for training the correction model. This approach aligns with standard practices in numerical PDE research and ensures that the method can be applied to general problems encountered in scientific and engineering simulations.

For real-world applications, the framework may also be extended in a self-supervised manner, where the target residual is estimated using a physics-informed local error metric (e.g., higher-order differential approximations or residual-based indicators) without requiring any external reference solution. Unlike physics-informed neural networks, operator-learning models, or hybrid SPH–ML schemes that modify the particle formulation or replace the PDE operator, the present work introduces a strictly non-intrusive correction layer that preserves the SSPH discretization and learns only its residual defect. This SPH-specific defect-learning strategy does not appear in existing meshfree literature and offers a lightweight, reproducible pathway for improving classical particle methods.

3.3. Algorithmic Framework

The proposed framework consists of two main components: the SSPH solver and the ML-based residual correction. Algorithm 1 outlines the construction of the SSPH solver for the Poisson equation. Algorithm 2 introduces the machine-learned residual correction designed to enhance the accuracy of the SSPH approximation.

| Algorithm 1 SSPH Solver for the Poisson Equation |

|

| Algorithm 2 Machine-Learned Residual Correction for SSPH |

|

It should be noted that for the nonlinear Poisson equation, Algorithm 1 is slightly modified to incorporate a damped Newton iteration for solving the nonlinear system resulting from the discretized form of Equation (12). The damping ensures stable convergence while preserving the efficiency and accuracy advantages of Newton’s method for nonlinear PDEs. All other steps in both algorithms remain unchanged.

Together, these two algorithms form an integrated framework in which the SSPH solver provides a robust numerical approximation, and the machine-learned correction systematically reduces the residual error. This combination illustrates the effectiveness of blending kernel-based discretization methods with modern data-driven techniques to achieve improved accuracy in solving elliptic partial differential equations.

4. Numerical Examples

In this section, we illustrate the performance of the proposed algorithmic framework through four representative numerical examples. The study focuses on the Poisson equation, as formulated in Equation (9) for the linear case and the nonlinear case given by Equation (12), solved under four geometric configurations. The first case is defined on a standard rectangular domain, the second is defined on a square domain, the third employs an L-shaped domain featuring re-entrant corners, and the fourth is a challenging crescent-shaped annular region with two inner holes. The first three examples are solved for the linear Poisson equation while the fourth example is based on the nonlinear equation.

To evaluate the numerical accuracy, one global error metric based on the norm is employed to compare the performance of the conventional SSPH solver and the ML-enhanced approach across multiple levels of mesh refinement. The global relative error, , is computed as the ratio between the norm of the absolute error and that of the exact solution:

In addition to global accuracy indicator, a pointwise absolute error is also evaluated at each computational node , defined as

This local metric forms the basis for heatmap plots of the error distribution.

We also report the CPU timings for the SSPH solver and the machine-learning-based residual correction across various particle resolutions to assess the computational overhead introduced by the ML enhancement. All experiments were conducted on a workstation equipped with an 11th Gen Intel® Core™ i7-1165G7 processor running at 2.80 GHz.

The use of exact solutions in the examples serves primarily to provide clean, interpretable residuals for benchmarking. In Section 4.1, we demonstrate that the ML residual correction can also be applied when an exact solution is unavailable by using a high-resolution SSPH solution on a finer grid as a reference. This keeps the workflow fully within the SSPH framework, ensuring consistency and simplicity, while achieving the same purpose as using a FEM reference. In practice, the ML correction can be trained using high-fidelity numerical solvers, adaptive SSPH solutions, or families of solutions parameterized by coefficients or boundary conditions. Therefore, the proposed framework is not limited to problems with closed-form analytical solutions and can be applied to general Poisson problems.

4.1. Example 1

We consider the Poisson equation presented by Equation (9) on a rectangular domain

with Dirichlet boundary conditions as in Equation (10):

Here, the right-hand side term is chosen as a smooth, manufactured function to represent a general problem without a closed-form solution:

where controls the spread of the Gaussian and is chosen to be 1.

A high-resolution SSPH solution on a finer grid () is computed and used as a reference solution .

The SSPH smoothing length is set as

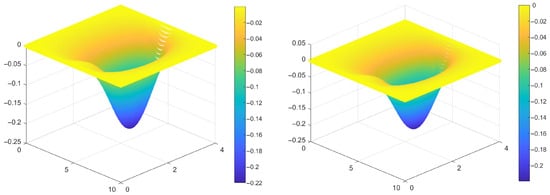

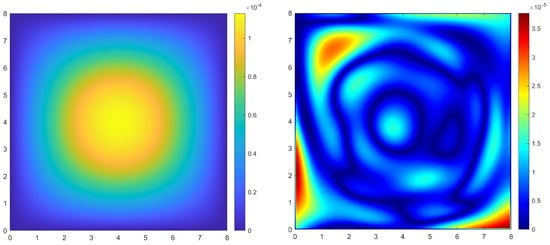

The Wendland kernel in is adopted and defined as in Equation (8). Figure 4 depicts the numerical solution for the classical SSPH method and the proposed SSPH-based ML residual correction.

Figure 4.

Numerical solution for the Poisson problem in Section 4.1 with grid points. Left: classical SSPH solution; Right: SSPH solution with ML residual correction.

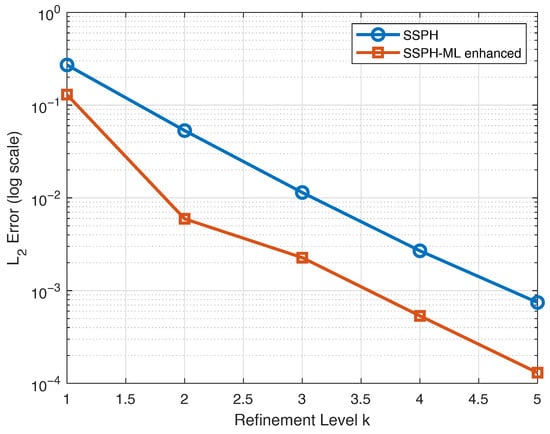

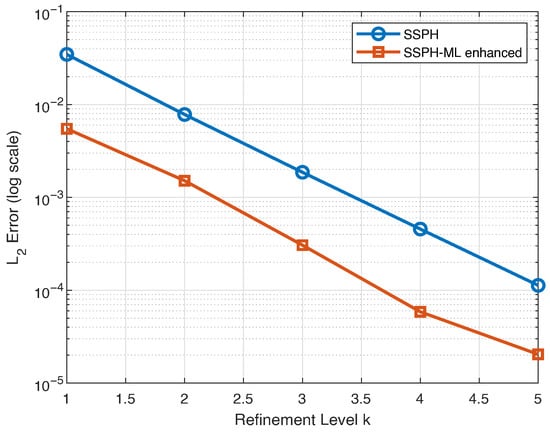

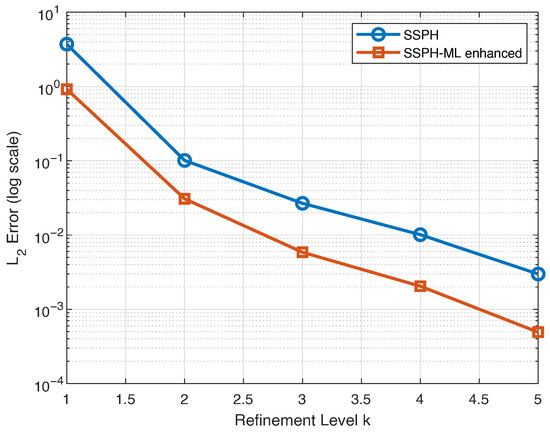

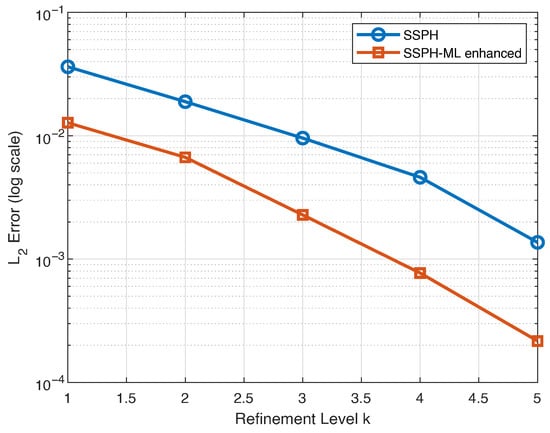

Figure 5 shows the relative error, , for both the standard SSPH and the proposed method across five levels of refinement, . These correspond to grid sizes of and grid points, respectively. The results indicate that the proposed method consistently reduces the relative error compared to SSPH at all resolutions. Furthermore, the error decreases steadily as the grid is refined, showing clear convergence and demonstrating the improved accuracy of the proposed approach.

Figure 5.

Convergence comparison of the for the standard SSPH and SSPH-ML enhanced methods across multiple grid refinement levels k for Section 4.1.

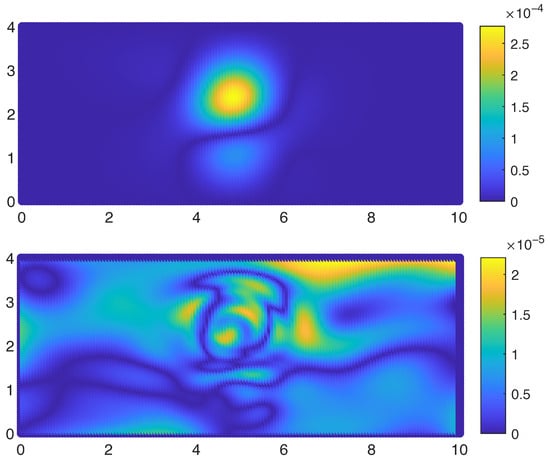

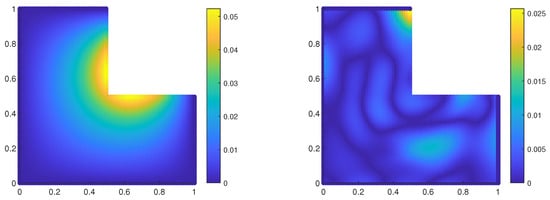

The pointwise absolute error distributions on the grid for both the SSPH and the proposed method are shown in Figure 6. The proposed method clearly achieves a lower overall error, while the SSPH solution produces a smoother error field. This is expected for SSPH schemes enhanced with ML-based residual correction: the correction mainly focuses on regions with high local error. As a result, the absolute error field may appear slightly less smooth, but the global error is significantly reduced. The smoothness difference becomes less pronounced at higher grid resolutions.

Figure 6.

Absolute error distribution for the Poisson problem in Section 4.1 with grid points. Top: classical SSPH solution; Bottom: SSPH solution with ML residual correction.

To evaluate the computational overhead introduced by the machine-learned residual correction stage, a systematic timing analysis was conducted across multiple particle resolutions. The results are summarized in Table 1. As expected for meshfree particle methods, the computational effort of the SSPH solver increases with the total number of particles due to the higher cost of neighbor searches and local MLS reconstructions. In contrast, the ML correction remains relatively inexpensive because the network is lightweight (40 hidden neurons) and is trained only once per simulation. Across all resolutions tested, the ML overhead decreases with the increase in particles, indicating an efficient computational time. The ML correction significantly improves the accuracy of the SSPH solution while adding only a modest computational cost.

Table 1.

CPU timings for the SSPH solver and ML residual correction at different particle resolutions for Section 4.1.

The purpose of this example is to demonstrate that our ML-enhanced SSPH framework performs effectively even when an exact analytical solution is not available, provided that a high-fidelity reference solution is used. In many practical applications, closed-form solutions simply do not exist, and numerical analysts routinely rely on FEM with a fine mesh, high-resolution SSPH, or other accurate solvers as surrogates for the true solution. Our modification follows this well-established practice: the ML module is trained to correct coarse-grid SSPH errors using a numerically generated reference field rather than an analytical benchmark. This not only shows that the method generalizes to realistic problems, but also confirms that the framework is inherently designed to work with reference solutions, making the approach more practical, more flexible, and more aligned with real-world usage where exact solutions are rarely available.

4.2. Example 2

In this example, we consider the model problem described by Equation (9) on a square domain

with the homogeneous Dirichlet boundary conditions

The analytical solution is given as

which automatically satisfies the boundary conditions along all domain boundaries.

The right-hand side (RHS) is given as

The SSPH smoothing length is set as

The Wendland kernel in presented by Equation (8) is adopted as the kernel function.

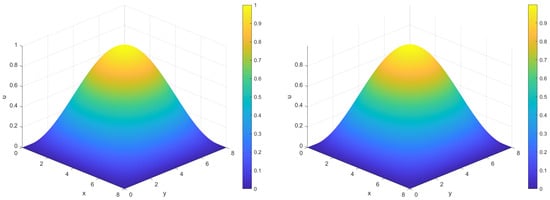

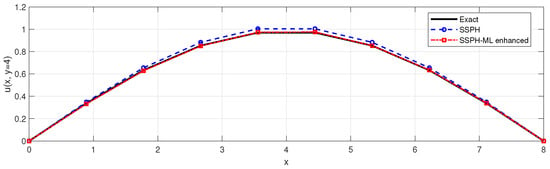

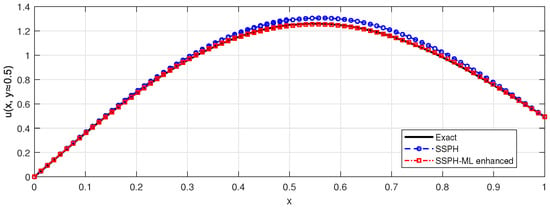

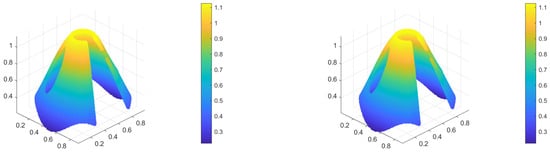

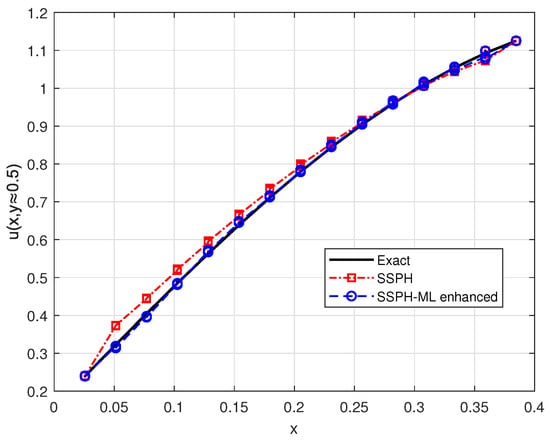

This configuration provides a smooth sinusoidal field on a symmetric square domain with a problem that contains homogeneous Dirichlet boundary conditions, making it suitable for evaluating both the accuracy and stability of the SSPH discretization and the performance of the proposed machine-learned residual correction. The numerical solution for the classical SSPH method and the proposed SSPH-based ML residual correction are presented in Figure 7. Figure 8 depicts a cross-sectional plot along the domain midline, comparing the exact, SSPH, and SSPH-ML enhanced solutions.

Figure 7.

Numerical solution for the Poisson problem in Section 4.2 with grid points. Left: classical SSPH solution; Right: SSPH solution with ML residual correction.

Figure 8.

One-dimensional cross-section of the exact, SSPH, and ML-corrected SSPH solutions along the midline of the square domain . The SSPH-ML enhanced curve closely matches the exact solution and eliminates most of the residual numerical error observed in the plain SSPH solution. This cross-sectional view highlights the accuracy gain achieved through the ML residual-correction stage for Section 4.2.

Figure 9 illustrates the relative error, , for both the conventional SSPH and the proposed approach across five refinement levels, , corresponding to grid sizes of and . It can be seen that the proposed method consistently outperforms SSPH, maintaining lower errors at every resolution. Moreover, the error diminishes progressively as the grid is refined, indicating convergence and confirming the enhanced accuracy offered by the proposed scheme.

Figure 9.

Convergence comparison of the for the standard SSPH and SSPH-ML enhanced methods across multiple grid refinement levels k for Section 4.2.

Figure 10 depicts the pointwise absolute error distribution on the grid for both the standard SSPH and the proposed method. As in Section 4.1, the proposed approach achieves a noticeably lower overall error, whereas the SSPH solution exhibits a smoother error pattern. The absolute error field of the proposed method may appear slightly less uniform and concentrated close to the homogeneous boundary conditions, but the total error is substantially reduced. The difference in smoothness diminishes at finer grid resolutions.

Figure 10.

Absolute error distribution for the Poisson problem in Section 4.2 with grid points. Left: classical SSPH solution; Right: SSPH solution with ML residual correction.

Table 2 summarizes the CPU times required for the SSPH solver and the subsequent ML-based residual correction across a range of particle resolutions. As expected, the SSPH assembly and linear solve dominate the computational cost, and their runtime increases rapidly as the total number of particles grows. In contrast, the ML correction remains extremely lightweight for all resolutions. These results confirm that the accuracy improvements obtained from the ML residual correction come at an extremely modest computational cost, reinforcing the practicality and efficiency of the proposed hybrid method.

Table 2.

CPU timings for the SSPH solver and ML residual correction at different particle resolutions for Section 4.2.

Although fixed hyperparameters are used for consistency across examples, additional tests indicate that the ML-enhanced SSPH method remains stable for smoothing-length factors between , hidden-layer sizes between neurons, and different compactly supported kernels. Extreme values (e.g., excessively small h) reduce performance, highlighting the importance of maintaining sufficient neighbor overlap in SSPH.

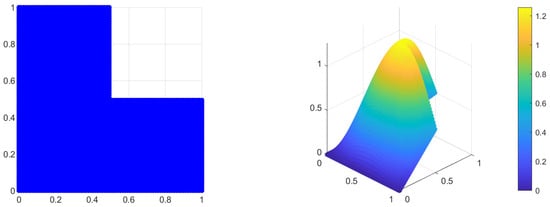

4.3. Example 3

In this example, we consider the Poisson equation presented in Equation (9) on an L-shaped domain, which is chosen due to its geometric complexity and the presence of a singularity at the reentrant corner. This makes it a challenging test case to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed approach. The domain is defined as

with Dirichlet boundary conditions imposed on all sides, manufactured to match the exact solution on the boundaries. The right-hand side is derived from the Laplacian of the exact solution:

where the exact solution is chosen as

which is smooth in the interior but exhibits nontrivial behavior near the reentrant corner. The SSPH smoothing length is set as

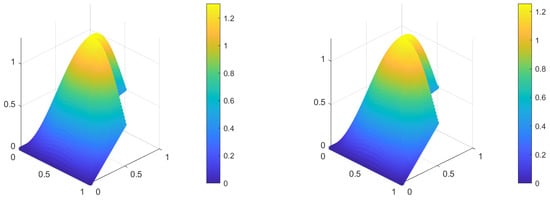

and the Wendland kernel in is adopted as defined in Equation (8). The computational domain and the exact solution are presented in Figure 11. Figure 12 shows the numerical solution obtained using the classical SSPH method and the proposed SSPH enhanced with ML-based residual correction using grid points. Figure 13 depicts a cross-sectional plot along the domain midline, comparing the exact, SSPH, and SSPH-ML enhanced solutions.

Figure 11.

Left: L-shaped domain for the Poisson problem in Section 4.3; Right: Exact solution presented by grid points.

Figure 12.

Numerical solution for the Poisson problem in Section 4.3 with grid points. Left: classical SSPH solution; Right: SSPH solution with ML residual correction.

Figure 13.

One-dimensional cross-section of the exact, SSPH, and ML-corrected SSPH solutions along the midline of the L-shaped domain . The SSPH-ML enhanced curve closely matches the exact solution and eliminates most of the residual numerical error observed in the plain SSPH solution. This cross-sectional view highlights the accuracy gain achieved through the ML residual-correction stage for Section 4.3.

Figure 14 shows the relative error, , for both the standard SSPH and the proposed method over five refinement levels, (grid sizes to ). The proposed approach consistently yields lower errors at all resolutions, and the error decreases steadily with grid refinement, demonstrating convergence and improved accuracy despite the presence of a singularity in the computational domain.

Figure 14.

Convergence comparison of the for the standard SSPH and SSPH-ML enhanced methods across multiple grid refinement levels k for Section 4.3.

Figure 15 presents the pointwise absolute error for the grid, comparing the SSPH and the proposed method.

Figure 15.

Absolute error distribution for the Poisson problem in Section 4.3 with grid points. Left: classical SSPH solution; Right: SSPH solution with ML residual correction.

Table 3 reports the CPU timings for the SSPH solver and the ML residual correction across increasing particle resolutions. As the grid becomes finer, the SSPH computation time grows significantly, while the ML correction remains extremely inexpensive. Consequently, although the ML stage represents about of the total runtime at the coarsest grid, its relative overhead rapidly decreases below for resolutions of and higher. This confirms that the proposed ML correction introduces only a negligible computational cost at practical problem sizes.

Table 3.

CPU timings for the SSPH solver and ML residual correction at different particle resolutions for Section 4.3.

The results of this example demonstrate that the ML-enhanced SSPH performs robustly, even in the presence of singularities at the reentrant corner. The method consistently reduces errors compared to the standard SSPH, particularly near regions of high local error. This confirms the effectiveness of the proposed approach for complex geometries.

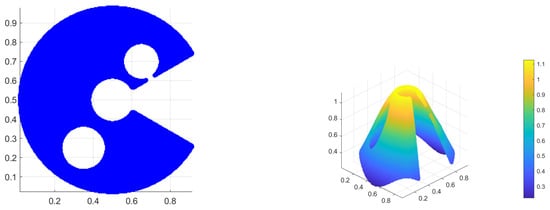

4.4. Example 4

In this example, we consider a highly nontrivial curved domain to assess the robustness of the SSPH method under severe geometric distortion. The computational domain is a crescent-shaped annular region centered at , with an inner radius , an outer radius , and an angular extent . Two circular interior holes are removed from the domain: one with radius centered at and another with radius centered at . This geometry introduces curved outer boundaries, concave regions, and multiply-connected topology, all of which are known to challenge meshfree Laplacian operators.

We solve the nonlinear elliptic problem presented in Equation (12):

with Dirichlet boundary conditions taken from a manufactured exact solution

The source term f is computed by substituting into the PDE, ensuring that is the analytical solution on this complex domain. This configuration serves as a demanding test of the proposed method. The combination of curved boundaries, non-convex regions, and internal voids makes this example significantly more challenging than the standard rectangular or L-shaped tests and is therefore well-suited for demonstrating the stability of the operators and the benefit of the ML-enhanced post-processing.

The SSPH smoothing length is selected as

and the Wendland kernel given in Equation (8) is employed throughout the computation. The curved crescent-shaped computational domain and the manufactured exact solution are shown in Figure 16. The corresponding numerical approximations obtained using the classical SSPH method and the ML-enhanced SSPH formulation are presented in Figure 17 for a resolution of background grid points. To further demonstrate the improvement introduced by the ML correction, Figure 18 provides a cross-sectional profile extracted along the geometric midline of the domain, comparing the exact, SSPH, and ML-enhanced SSPH solutions.

Figure 16.

Left: Computational domain for the nonlinear Poisson problem in Section 4.4; Right: Exact solution presented by grid points.

Figure 17.

Numerical solution for the nonlinear Poisson problem in Section 4.4 with grid points. Left: classical SSPH solution; Right: SSPH solution with ML residual correction.

Figure 18.

One-dimensional cross-section of the exact, SSPH, and ML-corrected SSPH solutions along the midline of the computational domain . The SSPH-ML-enhanced curve closely matches the exact solution and eliminates most of the residual numerical error observed in the plain SSPH solution. This cross-sectional view highlights the accuracy gain achieved through the ML residual-correction stage for Section 4.4.

Figure 19 presents the relative error, , for both the standard SSPH method and the proposed ML enhanced formulation over five refinement levels, (corresponding to grid sizes , , , and ). The proposed approach consistently achieves lower errors at all resolutions, and the error decreases monotonically with grid refinement, demonstrating both convergence and the improved accuracy of the method, even in the presence of problem nonlinearity and geometrical challenges within the computational domain.

Figure 19.

Convergence comparison of the for the standard SSPH and SSPH-ML enhanced methods across multiple grid refinement levels k for Section 4.4.

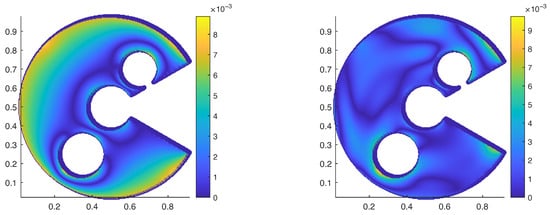

Figure 20 presents the pointwise absolute error for the grid, comparing the standard SSPH solution with the proposed ML-enhanced formulation.

Figure 20.

Absolute error distribution for the nonlinear Poisson problem in Section 4.4 with grid points. Left: classical SSPH solution; Right: SSPH solution with ML residual correction.

Table 4 reports the CPU timings for the SSPH solver and the ML residual correction across increasing particle resolutions. As the grid becomes finer, the SSPH computation time increases substantially, whereas the ML correction remains extremely inexpensive. Consequently, although the ML stage represents about of the total runtime of the coarsest grid, its relative overhead rapidly decreases to below for resolutions of and higher. This demonstrates that the proposed ML correction introduces only a negligible computational cost at practically relevant problem sizes.

Table 4.

CPU timings for the SSPH solver and ML residual correction at different particle resolutions for Section 4.4.

The results of this example demonstrate that the proposed method performs robustly on a highly irregular curved domain containing multiple holes and geometric discontinuities. The proposed correction consistently reduces the numerical error compared to the standard SSPH formulation, with the most pronounced improvements observed in regions where the nonlinear term and geometric complexity induce larger local inaccuracies. These findings confirm the effectiveness and stability of the ML-based residual correction when applied to challenging nonlinear elliptic problems on complex geometries.

Although Wendland is used in all reported experiments, additional internal tests with the cubic spline and Gaussian kernels show that the ML residual correction consistently reduces the SSPH error across all kernel types. The Wendland kernel provides the most stable neighbor distribution and lowest baseline error, but the correction mechanism itself is kernel-agnostic.

5. Conclusions

This work introduced an intelligent SSPH framework enhanced by machine-learned residual correction for solving elliptic partial differential equations. By integrating a data-driven correction layer into the classical SSPH discretization, the proposed method significantly improved solution accuracy without altering the underlying physics-based formulation. Numerical experiments for linear and nonlinear Poisson equations on different domains demonstrated consistent error reduction and stable convergence behavior, even in the presence of geometric singularities. The approach remains fully non-intrusive, making it adaptable to other meshfree formulations and PDE classes. Future extensions may include adaptive retraining strategies, incorporation of Neumann boundary conditions, and application to time-dependent problems.

Author Contributions

A.Q.: conceptualization, formal analysis, Methodology, funding acquisition, writing and editing draft manuscript; T.Y.: conceptualization, visualization, validation, writing, review and editing; F.D.: conceptualization, validation, visualization, writing, review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Internal Research Grant #(IRG/2025/002) from Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Bethlehem University, Palestine. Tianhui Yang is also supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 12401502) and Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. ZR2022QA060).

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to sincerely thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and constructive feedback, which have significantly contributed to improving the quality of this manuscript. The first author, Ammar Qarariyah, would like to thank the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research and his group members at Bethlehem University for their continuous support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ames, W.F. Nonlinear Partial Differential Equations in Engineering: Mathematics in Science and Engineering: A Series of Monographs and Textbooks; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 18. [Google Scholar]

- Qarariyah, A.; Yang, T.; Deng, F. A Solution-Structure B-Spline-Based Framework for Hybrid Boundary Problems on Implicit Domains. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Hernandez, A.; Brambila-Paz, F.; Torres-Martínez, C. Numerical solution using radial basis functions for multidimensional fractional partial differential equations of type Black–Scholes. Comput. Appl. Math. 2021, 40, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.K.; Li, S.; Park, H.S. Eighty years of the finite element method: Birth, evolution, and future. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2022, 29, 4431–4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinkovic, D.; Zehn, M. Survey of finite element method-based real-time simulations. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicke, M.; Ritchie, D.; Klingner, B.M.; Burke, S.; Shewchuk, J.R.; O’Brien, J.F. Dynamic local remeshing for elastoplastic simulation. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 2010, 29, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belytschko, T.; Krongauz, Y.; Organ, D.; Fleming, M.; Krysl, P. Meshless methods: An overview and recent developments. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 1996, 139, 3–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Qarariyah, A.; Deng, J. Spline R-function and applications in FEM. Numer. Math. Theory Methods Appl. 2019, 13, 150–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, F. A novel semi-analytical meshless method for the thickness optimization of porous material distributed on sound barriers. Appl. Math. Lett. 2024, 147, 108844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qarariyah, A.; Yang, T.; Deng, J. Solving higher order PDEs with isogeometric analysis on implicit domains using weighted extended THB-splines. Comput. Aided Geom. Des. 2019, 71, 202–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, X.; Zhao, H.; Liu, Y. A novel meshless method based on the virtual construction of node control domains for porous flow problems. Eng. Comput. 2024, 40, 171–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gingold, R.A.; Monaghan, J.J. Smoothed particle hydrodynamics: Theory and application to non-spherical stars. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1977, 181, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Liu, G. Smoothed particle hydrodynamics (SPH): An overview and recent developments. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2010, 17, 25–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geara, S.; Martin, S.; Adami, S.; Petry, W.; Allenou, J.; Stepnik, B.; Bonnefoy, O. A new SPH density formulation for 3D free-surface flows. Comput. Fluids 2022, 232, 105193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Xie, J.; Jiang, M. A coupled peridynamics–smoothed particle hydrodynamics model for fracture analysis of fluid–structure interactions. Ocean Eng. 2023, 279, 114582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.R.; Liu, M.B. Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics: A Meshfree Particle Method; World Scientific: Singapore, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bagheri, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Riazi, M. A review of smoothed particle hydrodynamics. Comput. Part. Mech. 2024, 11, 1163–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Violeau, D.; Rogers, B.D. Smoothed particle hydrodynamics (SPH) for free-surface flows: Past, present and future. J. Hydraul. Res. 2016, 54, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, D.J. Smoothed particle hydrodynamics and magnetohydrodynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 2012, 231, 759–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meleán, Y.; Sigalotti, L.D.G.; Hasmy, A. On the SPH tensile instability in forming viscous liquid drops. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2004, 157, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigalotti, L.D.G.; López, H. Adaptive kernel estimation and SPH tensile instability. Comput. Math. Appl. 2008, 55, 23–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilts, G.A. Moving-least-squares-particle hydrodynamics—I. Consistency and stability. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 1999, 44, 1115–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randles, P.; Libersky, L. Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics: Some recent improvements and applications. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 1996, 139, 375–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendland, H. Piecewise polynomial, positive definite and compactly supported radial functions of minimal degree. Adv. Comput. Math. 1995, 4, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Batra, R. Symmetric smoothed particle hydrodynamics (SSPH) method and its application to elastic problems. Comput. Mech. 2009, 43, 321–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcarolo, D.A.; Le Touzé, D.; Oger, G.; De Vuyst, F. Adaptive particle refinement and derefinement applied to the smoothed particle hydrodynamics method. J. Comput. Phys. 2014, 273, 640–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatehi, R.; Manzari, M.T. Error estimation in smoothed particle hydrodynamics and a new scheme for second derivatives. Comput. Math. Appl. 2011, 61, 482–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunton, S.L.; Kutz, J.N. Data-Driven Science and Engineering: Machine Learning, Dynamical Systems, and Control; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, J.; Kurzawski, A.; Templeton, J. Reynolds averaged turbulence modelling using deep neural networks with embedded invariance. J. Fluid Mech. 2016, 807, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grohs, P.; Herrmann, L. Deep neural network approximation for high-dimensional elliptic PDEs with boundary conditions. IMA J. Numer. Anal. 2022, 42, 2055–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raissi, M.; Perdikaris, P.; Karniadakis, G.E. Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 2019, 378, 686–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunton, S.L.; Kutz, J.N. Promising directions of machine learning for partial differential equations. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2024, 4, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Jiang, S.W.; Harlim, J.; Yang, H. Solving pdes on unknown manifolds with machine learning. Appl. Comput. Harmon. Anal. 2024, 71, 101652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, J.; Chen, L.; Guan, Y.; Zhang, C.; Gao, F.; Lin, J. Solving 2D Poisson-type equations using meshless SPH method. Results Phys. 2019, 13, 102260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özbay, A.G.; Hamzehloo, A.; Laizet, S.; Tzirakis, P.; Rizos, G.; Schuller, B. Poisson CNN: Convolutional neural networks for the solution of the Poisson equation on a Cartesian mesh. Data-Centric Eng. 2021, 2, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qarariyah, A.; Deng, F.; Yang, T.; Liu, Y.; Deng, J. Isogeometric analysis on implicit domains using weighted extended PHT-splines. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2019, 350, 353–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koric, S.; Abueidda, D.W. Data-driven and physics-informed deep learning operators for solution of heat conduction equation with parametric heat source. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 203, 123809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, H.; Miyama, S.M.; Sekiya, M. Numerical simulation of viscous flow by smoothed particle hydrodynamics. Prog. Theor. Phys. 1994, 92, 939–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaghan, J. Smoothed particle hydrodynamics. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2005, 68, 1703–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; O’Leary-Roseberry, T.; Jha, P.K.; Oden, J.T.; Ghattas, O. Residual-based error correction for neural operator accelerated infinite-dimensional Bayesian inverse problems. J. Comput. Phys. 2023, 486, 112104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).