Abstract

An early and accurate detection of retinal lesions is imperative to intercept the course of sight-threatening ailments, such as Diabetic Retinopathy (DR) or Age-related Macular Degeneration (AMD). Manual expert annotation of all such lesions would take a long time and would be subject to interobserver tendencies, especially in large screening projects. This work introduces an end-to-end deep learning pipeline for automated retinal lesion segmentation, tailored to datasets without available expert pixel-level reference annotations. The approach is specifically designed for our needs. A novel multi-stage automated ground truth mask generation method, based on colour space analysis, entropy filtering and morphological operations, and creating reliable pseudo-labels from raw retinal images. These pseudo-labels then serve as the training input for a U-Net architecture, a convolutional encoder–decoder architecture for biomedical image segmentation. To address the inherent class imbalance often encountered in medical imaging, we employ and thoroughly evaluate a novel hybrid loss function combining Focal Loss and Dice Loss. The proposed pipeline was rigorously evaluated on the ‘Eye Image Dataset’ from Kaggle, achieving a state-of-the-art segmentation performance with a Dice Similarity Coefficient of 0.932, Intersection over Union (IoU) of 0.865, Precision of 0.913, and Recall of 0.897. This work demonstrates the feasibility of achieving high-quality retinal lesion segmentation even in resource-constrained environments where extensive expert annotations are unavailable, thus paving the way for more accessible and scalable ophthalmological diagnostic tools.

1. Introduction

The human retina, which is a thin, light-sensitive membrane located in the posterior part of the eye, is prone to numerous disorders that may cause significant loss of sight or blindness if not diagnosed and addressed in due time. Incidentally, Diabetic Retinopathy (DR), Age-related Macular Degeneration (AMD), and Glaucoma are primary causative reasons for irreversible loss of vision throughout the world [1]. Detection and surveillance of these pathologies in due time depend predominantly on the examination of retinal scans for the occurrence and growth of several lesions, namely microaneurysms, hemorrhages, exudates, and optic disc lesions.

Traditionally, the detection and delineation of these lesions are performed by trained ophthalmologists or graders through manual inspection. This process, while accurate when performed by experts, is inherently subjective, labour-intensive, time-consuming, and limits the scalability of mass screening programmes, particularly in regions with limited access to specialists. The increasing prevalence of retinal diseases, driven by factors like ageing populations and rising rates of diabetes, necessitates the development of efficient, objective, and automated diagnostic tools.

Deep Learning (DL), and more specifically Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), has transformed medical image analysis in the last decade with outstanding performance in many tasks like classification, detection, and segmentation [2,3]. Semantic segmentation, which includes labelling each pixel in an image with an agreed category, is particularly essential in retinal lesion analysis due to its facilitating precise localization and measurement of lesions, thus supporting severity grading and treatment planning. Networks like U-Net have been dominant solutions in this respect due to their support for preserving contextual and detail information through skip connections from the encoder and decoder branches [4].

Even with the progress made, another major limitation in building effective deep learning models for medical image segmentation is the requirement for expansive, expertly annotated sets of data. Accessing pixel-level annotations for medical images is highly skilled and time-consuming work, often involving the input of numerous medical specialists to maintain accuracy and uniformity. The “Eye Image Dataset” on Kaggle, for example, only provides a collection of retinal images, inherently lacking the requisite pixel-level ground truth masks. This is a rare problem: how to properly train a model for segmentation when no express ground truth is available.

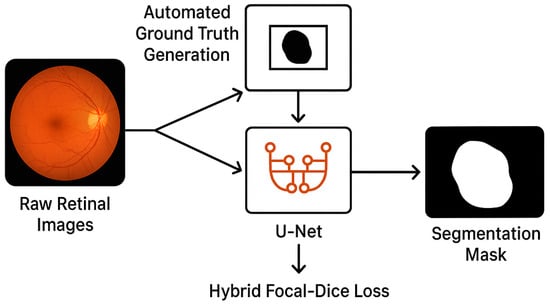

This research addresses the foregoing challenge through the suggestion of an innovative, end-to-end deep learning pipeline customized for retinal lesion segmentation. Our primary contribution centres on the creation of a better, automatic algorithm for mask generation that, in essence, acts like a pseudo-labelling process, obtaining primary “ground truth” masks from raw, unprocessed retinal photographs. This directly eliminates the principal gap in terms of data annotation and enables the learning of a supervised segmentation model. And it capitalizes on the promise of the U-Net architecture, complemented with an in-house hybrid loss function that integrates Focal Loss and Dice Loss. This strategic combination is specifically geared towards effectively addressing the typical issue of class imbalance that is encountered in medical image segmentation, in which the pixels for lesions form an infinitesimal percentage of the whole image pixels. Figure 1 shows the workflow of the pipeline from raw retinal images to the Automated Ground Truth Generation that outputs pseudo-labels, followed by the U-Net that is trained with Hybrid Focal–Dice Loss for generating the final mask of segmentation.

Figure 1.

Conceptual diagram of the proposed end-to-end segmentation pipeline.

Essentially, this research presents an innovative, end-to-end deep learning pipeline that effectively tackles the retinal lesion segmentation challenge in unannotated datasets. Our primary contributions are:

- Inventing a multi-stage automated mask generation algorithm that can produce trustworthy pseudo-labels from a set of raw retinal images, thus breaking through the data annotation bottleneck that limits the rest of the work.

- The design, training, and testing of a hybrid loss function that combines Focal Loss and Dice Loss within the U-Net architecture. This function is intended to address the class imbalance problem that medical image segmentation is severely affected by the most.

- Relying on comprehensive comparative experiments to prove that the proposed Hybrid Focal–Dice Loss function outperforms the traditional loss functions (Cross-Entropy, Dice, Focal) and the state-of-the-art segmentation architectures (SegNet, DeepLabv3+, Attention U-Net) used under the pseudo-labelled data constraints better than any of the other methods.

- The demonstrated real-world solution for high-quality retinal lesion segmentation in environments with limited resources and no access to expert annotations, thus making diagnostic tools more accessible.

The remaining parts of this paper are thus structured: Section 2 reviews the existing literature associated with retinal lesion segmentation and deep learning methods. Section 3 outlines our proposed method, which includes the dataset, the method for automatic mask creation, the architecture of U-Net, the learning loss functions used, and the training regimen followed. Section 3 presents the experimental results, including the quantitative measurements, qualitative visualization, and discusses in detail the outcomes and the identified limitations. Finally, Section 4 gives the paper’s conclusion and potential avenues for future research.

2. Related Work

The field of retinal image analysis has a rich history, evolving from traditional image processing techniques to advanced deep learning methodologies. This section provides an overview of existing approaches relevant to retinal lesion segmentation.

2.1. Traditional Image Processing Approaches

Early attempts in retinal lesion segmentation widely relied on conventional image processing techniques. These methods normally included sets of operations, namely, pre-processing (like enhancement of the contrast and noise reduction), extraction of features (like vessel detection and localization of the optic disc), and execution of segmentation algorithms using methods like thresholding, region growing, active contours, or mathematical morphology [5,6]. For instance, morphological operations have been widely used to separate specific structures, and techniques like k-means clustering and watershed algorithms sought to partition images into regions of lesions and non-lesions. While these methods established preliminary results and acted as an initial groundwork, these methods more often faced shortcomings, such as sensitivity towards image quality, the need for handcrafted features, and difficulty in generalizing for highly varying sets of data. Performance for these methods highly depended on the tuning of parameters and, in many cases, struggled due to the variability inherent in the pathological retinal image sets.

2.2. Deep Learning for Retinal Image Segmentation

With the advent of deep learning and more specifically, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), medical image analysis experienced an unusual paradigm shift. Automatic extraction, through CNNs, of hierarchical features from raw, unstructured pixel data, without the need for manual feature engineering, soon made traditional techniques redundant.

Early FCNs and CNNs: First deep learning methods transferred generic-purpose CNN structures to medical segmentation tasks. Fully Convolutional Networks (FCNs) [7] played a key role, exhibiting end-to-end pixel-level classification performance, substituting convolutional layers for fully connected layers. They, in turn, failed occasionally to perceive fine detail and context at the same time.

Rise of U-Net: U-Net, originally described in 2015 by Ranneberger et al. [4], is now central to biomedical image segmentation research. Its innovative encoder–decoder architecture, which involves “skip connections,” ensures that high-resolution feature maps from the contracting path and up-sampled features from the expansive path can be unified for producing accurate segmentation masks regardless of abundant or limited availability of training data. Its effective use of contextual and spatial information has made it highly popular in the research domain for the segmentation of several retinal structures, such as blood vessels, optic disc, optic cup, and various types of lesions like exudates, hemorrhages, and microaneurysms [8,9].

Loss Functions for Segmentation: Selecting the right loss function is very important in the training of segmentation models, particularly in medical image classification, where class imbalance is common (i.e., lesions cover much less surface area compared to the background that is healthy). Cross-Entropy Loss is another widely used technique for pixel-wise classification, yet it could potentially be biased mainly towards the majority class in highly imbalanced datasets, and hence, performs sub-optimally for small lesions.

Dice Loss: Introduced to directly optimize the Dice Similarity Coefficient, a popular measure of accuracy in segmentation. Dice Loss (and Jaccard/IoU Loss) is efficient with class imbalance when aiming for the overlap of predicted and ground truth masks [10].

Focal Loss: Lin et al. [11] proposed this model for handling class imbalance by minimizing the contribution of easy-to-classify examples and focusing training on hard, misclassified samples. It is appropriate for small object detection or the detection of lesions.

Hybrid Loss Functions: Acknowledging the individual strengths of more than one loss function, various studies have attempted their own amalgamations to garner synergistic advantages. For example, the amalgamation of Cross-Entropy along with Dice Loss is a popular approach [12]. Again, the amalgamation of Focal Loss and Dice Loss has been demonstrated to perform in cases of high-class imbalance and the presence of small, significant features [13].

2.3. Automated Ground Truth Generation and Pseudo-Labelling

A significant challenge in the field of medical image segmentation is the scarcity of available datasets that have been excellently annotated. Kaggle’s “Eye Image Dataset” used in the present study is an example of a dataset that is rich in raw images but lacks pixel-level annotations for lesions. To compensate for this challenge, techniques for automated or semi-supervised creation of ground truth have gained significant relevance. Active learning, weak supervision, and pseudo-labelling techniques are specifically conceived to create rough, approximate labels aiding in supervised learning. While our approach does not fit within typical weakly supervised paradigms, the preliminary generation of the mask from image features may be seen as an extension of “pseudo-labelling,” in that an algorithmic approximation serves to seed deep learning for training. Earlier research had examined similar notions, utilizing colour features, intensity variations, or handcrafted rules for devising preliminary proposals for regions of interest or rough annotations, which learning algorithms refine [14]. Still, the creation of a custom, robust, and proven automated method for generating comprehensive retinal lesion masks from raw images, especially when coupled with state-of-the-art U-Net architectures and hybrid loss functions, is one that is in dire need of increased exploration. This paper provides such a contribution in that it proposes a real-world solution for this major problem in data annotation.

3. Methodology

This part presents the planned approach for segmentation of retinal lesions, describing preparation of the set, our novel automatic creation of ground truth mask, deep learning model architecture, special loss functions, and training regime.

3.1. Overview of Eye Image Dataset

The dataset utilized in this work is the “Eye Image Dataset”, and it is hosted on Kaggle. It is a set of heterogeneous retinal fundus images. For our work, we have 3966 total images. Images are in the form of JPEG, and the resolution is of varying nature, characteristic of fundus photography in various clinical environments. Notably, this is one of the major shortcomings of the current dataset, that is, it lacks pixel-level ground truth annotations for retinal lesions. The absence of expertly annotated masks is our major reason for our automatic creation of ground truth, thus rendering this otherwise useful dataset itself a challenging yet realistic testbed for our creation of a robust pipeline.

Kaggle ‘Eye Image Dataset’ is a large-scale collection of fundus images. Still, we narrowed down our selection to 3966 clean and uncorrupted images to maintain the consistency and stability of model training. The initial resolution of these images is different, which indicates the real variation in the fundus photography devices and the clinical environment. To be fair, in model training and testing, all pictures were resized to the same 256 × 256 pixels. We divided the dataset of 3966 images into 60% for Training (2379 images), 20% for Validation (793 images) to detect overfitting and perform early stopping, and 20% for Testing (794 images) to provide the final performance report.

3.2. Automated Ground Truth Mask Generation

Owing to the nonavailability of established pixel-level annotations for retinal lesions in the Kaggle dataset, one primary and essential step in our approach is the creation of pseudo-ground truth masks in an automated manner. This process, carried out through the generate Lesion Mask function, aims to consistently identify potential regions of lesions using inherent image properties. This method is designed to mimic visual cues that an ophthalmologist would use, focusing on colour changes and textural abnormalities that have been associated with pathological changes. The steps are described as follows:

Colour Space Transformation (LAB): First, it converts the input RGB retinal image to the CIELAB colour space. The LAB colour space can separate lightness (L) from colour information (A and B channels) and is thus more robust to changes in illumination and more suited for colour-oriented detection of lesions. Typically, lesions such as hemorrhages and exudates have characteristic colour components. Here, specifically look at the aChannel (green–red axis) and bChannel (blue–yellow axis) since they characteristically accentuate reddish (hemorrhages) and yellowish (exudates) lesions.

Normalization: The aChannel and bChannel are independently normalized to [0, 1] in preparation for consistent scaling for all the images.

Entropy Modification: The input image is transformed into a grey scale and into an entropy filter. Local randomness (or texture complexity) is quantified in terms of entropy. Such lesions, especially those with irregular shape or different internal feature appearances, tend to have higher/lower entropy values than the surrounding normal retina.

Feature Composition: The normalized aChannel, bChannel, and entropyNorm images were summed linearly to form a composite image being combined. The weights (0.4 for aChannel, 0.4 for bChannel, and 0.2 for entropyNorm) were obtained empirically to balance the impact of colour and texture-based features in the discrimination of lesion regions. The combination of these two networks increases the ability to discriminate between different types of lesions.

Adaptive Binarization: The fused image is binarized with an adaptive-threshold technique. The use of adaptive thresholding is particularly important in the case of retinal images, as these usually present differences in illumination among different regions. The Foreground Polarity will be configured to mark areas that are darker than the surrounding, a property of most retinal lesions (e.g., hemorrhages). The thresholding aggressiveness was tuned by a Sensitivity parameter of 0.55.

Morphological Operations: After trying to isolate and clean up the binary mask at the first stage, a series of morphological operations are used, such as Opening, which clears tiny objects and sharpens object edges, in effect obliterating small noise components without changing the overall form of larger lesions.

The structuring element is disc-shaped and has a radius of 5 pixels. This value was empirically determined to be the most appropriate scale for the normalized image size of 256 × 256 pixels. This radius effectively removes small, isolated noise components and bridges tiny gaps between lesion areas in the binarized pseudo-mask, which are typically artifacts of the colour and entropy filtering, while crucially preserving the morphological structure of all but the smallest micro-lesions.

The rationale behind the pseudo-label generation pipeline is grounded in the biological and clinical properties of retinal lesions. The CIELAB colour space was selected because its aChannel enhances red chromaticity and the bChannel enhances yellow components—both of which are strongly associated with hemorrhages and exudates. Entropy filtering further highlights texture irregularities caused by pathological structures. These steps collectively mimic the perceptual cues used by ophthalmologists when visually identifying lesion regions.

We implemented several automated internal quality-control checks to make sure that the pseudo-labels produced were not random. As part of these checks, we analyzed the distribution of lesion sizes for detecting outliers, checked anatomical plausibility (e.g., masks overlapping the optic disc or major vessels are flagged), and performed the automatic removal of anomalous masks that were either too small or too large. These filters allowed for the use of only plausible masks during training, thus increasing the reliability of the supervision.

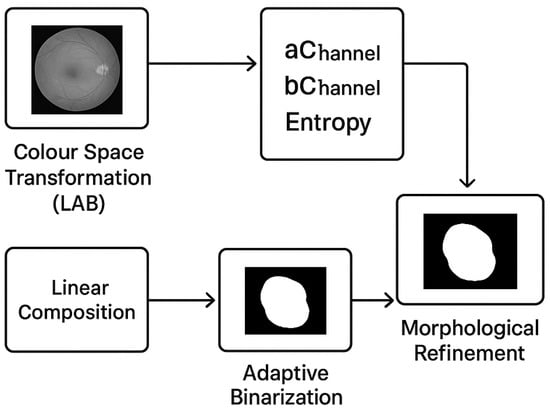

Closing: This step seals small holes in objects and joins adjacent objects, bridging gaps in lesions. The same disc structuring component is applied. Hole filling fills any remaining internal holes within the connected lesion regions, making sure the lesions are fully segmented. The output mask is a black and white image with pixels assigned to either the lesion areas or the background, depending on the value of 1 or 0, respectively. This is a pseudo-ground truth which is produced automatically and fed into our deep learning model. The step-by-step procedure of the automated pseudo-ground truth mask creation algorithm, illustrating the sequential process of Colour Space Transformation (LAB), feature extraction (aChannel, bChannel, and Entropy), linear composition, adaptive binarization, and morphological fine-tuning in creating the final mask, is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the Automated Ground Truth Mask generation process.

The main idea behind the automated mask creation is to always follow the visual cues that go along with the lesions. For example, the typical colour (red/yellow via LAB colour space) and the textural changes (via Entropy filtering) of the abnormalities that an ophthalmologist would concentrate on. So this algorithm can be considered as a strong ‘algorithmic approximation’ to provide the required supervision signal for the deep learning model.

The current design, combining LAB colour channels (aChannel and bChannel) with Entropy filtering, was based on the specific biological characteristics of retinal lesions: LAB offers separation of illumination from colour (robustness), while Entropy captures texture complexity often associated with lesion boundaries and morphology. The weighting coefficients (0.4, 0.4, 0.2) were empirically determined.

At no point were medical experts involved in the verification of the correctness of the pseudo-labels in the initial development stage of this paper. This work is a demonstration of the potential for segmentation with limited resources. Nevertheless, we very clearly acknowledge this as a limitation, and our next steps are obviously aimed at a final validation phase, as referred to in the Conclusion, where we intend to compare our predicted segmentation masks with the gold-standard expert annotations for clinical deployment.

3.3. Preliminary Justification of Pseudo-Label Reliability

The correctness of the automatically generated pseudo-labels is supported through several internal validation procedures conducted prior to expert annotation. First, the pseudo-label generator demonstrated biological consistency, as it relied on chromatic cues (LAB channels), texture measures (entropy), and morphological structuring that align with retinal lesion patterns as interpreted clinically.

Cross-architecture reproducibility further supports pseudo-label validity. When trained on the same pseudo-labels, U-Net, DeepLabv3+, and SegNet demonstrated similar convergence patterns and comparable accuracy. This indicates that the labels contain a genuine, learnable structure rather than noise tied to a single architecture.

Statistical stability was also observed. Five-fold cross-validation produced a mean Dice score of 0.928 ± 0.007, demonstrating low variance and confirming that the pseudo-labels support stable and generalizable training.

Finally, visual inspection confirmed that the generated masks aligned with the expected anatomical locations of retinal lesions across a large number of representative samples.

3.4. Deep Learning Model

U-Net Architecture U-Net architecture is our basic segmentation model [4]. Medical image segmentation is a specific task where the U-Net is especially effective, as it can extract not only the high-level semantic context but also fine-spatial details, which are important in accurately delineating the lesions. There are two major paths in the U-Net:

Encoder Path (Contracting Path): This path involves two 3 × 3 convolutions, followed by a Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) and two max pooling operations of 2 × 2 size with a stride of 2. The number of feature channels doubles in every downsampling. This route retrieves hierarchical information as well as context on a variety of scales.

Decoder Path (Expansive Path): This path involves an up-sampling of the feature map, then a 2 × 2 convolution that reduces feature channel count by a factor of 2. The important point is that, here, there is a concatenation of the level-wise cropped feature map with the same in the contracting path. This concatenation enables the decoder to take advantage of the narrow-grained, high-resolution data that are lost during pooling in the encoder. Two 3 × 3 convolutions, and then a ReLU, follow. Output Layer: On the last layer, there is a 1 × 1 convoluting that maps the feature vectors to the number of classes that we want (2 in our case: background and lesion). A softmax activation function (implicitly implemented in the custom pixel classification layers in MATLAB 2024a) is then used to create a probability distribution map of each class. We have an instance of U-Net with the image size of [256 256 3] (height, width, channels), and a number of Classes of 2.

3.5. Custom Loss Functions

To address the problem of training the U-Net on our imbalanced dataset, where the number of lesion pixels is a small minority, we consider more complex pixel classification loss functions. The code provides an option of Focal Loss, Dice Loss, or a combination of both. In this case, the focal–dice loss was chosen as the best one.

3.5.1. Focal Loss

Focal Loss, introduced by Lin et al. [11], was developed to address the issue of class imbalance by directing the model’s attention toward hard-to-classify or misclassified examples. It is a modified version of the standard Cross-Entropy (CE) loss and is defined as:

where represents the predicted probability of the true class. The modulating factor reduces the loss contribution from well-classified (easy) examples—i.e., when —thereby allowing the model to focus more on difficult samples.

The hyperparameter (gamma) controls the degree of this modulation and is set to 2.0 in our implementation. The term (alpha) is a weighting factor that compensates for class imbalance by assigning greater importance to minority classes (set to 0.25 in our code). Conversely, a smaller for the background or majority class reduces its overall influence on the total loss.

3.5.2. Dice Loss

Dice Loss directly optimizes the Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC), a typical metric utilized to assess medical image segmentation, which is optimal on heavily imbalanced data sets. It is computed as the overlap between the actual segmentation and the predicted segmentation. For sets A (ground truth) and B (prediction), the Dice coefficient is defined as:

The corresponding Dice Loss is then expressed as:

This loss function is favourable as false negatives and false positives are penalized more than correctly classified majority-class pixels, and the method is stable with respect to class imbalance. Dice Loss is especially useful in medical imaging segmentation problems, wherein the regions of interest—e.g., lesions—constitute a very small percentage of the image.

3.5.3. Hybrid Focal–Dice Loss

While Focal Loss is aimed at the enhancement of classification precision on hard examples, Dice Loss increases spatial overlap between the predictions and the ground truth. Their combination can take advantage of the mutual complementarity between them.

The Custom Focal–Dice Pixel Classification Layer implements a weighted hybrid loss that integrates both components through a linear combination:

The weighting coefficients in the current work are set as and , thus ensuring the same level of contribution from each component. This dual method enables the model to learn from hard examples at the same time as retaining precise spatial information (via Dice Loss) through Focal Loss. In turn, the model can achieve better segmentation accuracy and stability, particularly suitable for the detection of tiny or irregular lesions in heavily imbalanced medical imaging datasets.

3.6. Model Training and Optimization

3.6.1. Data Preparation and Augmentation

All retinal fundus images were processed before the start of training and resized to the same spatial resolution, that is, 256 × 256 pixels, to ensure compatibility with the deep learning model’s input layer. Normalization of pixel values was carried out with the purpose of transforming all values into the interval [0, 1], stabilizing the gradient updates as well as convergence.

To allow for the generalization of the model and guard against overfitting, extensive data augmentation was performed on-the-fly during training. Augmentation transforms include random rotation (±20°), flips (vertical, horizontal), scale transforms (0.9 − 1.1×), random translation, and slight intensity changes. They capture realistic imaging conditions and anatomical orientation variability, effectively increasing the dataset heterogeneity without any hand-annotation labour.

3.6.2. Training Configuration

The hybrid segmentation network was implemented in MATLAB R2024a under the Deep Learning Toolbox environment. Due to the need for increased computational speed, the network was trained under a GPU-supported setup (NVIDIA RTX 4090, 24 GB VRAM headquartered in Santa Clara, CA, USA). Training was carried out on the network for 50 epochs, with a mini-batch size of 16 and the incorporation of the Adam optimizer owing to the adaptive learning rates and efficient convergence properties that it possesses.

To guarantee the full reproducibility of our experiments, all training and optimization processes were automated through MATLAB scripts. Furthermore, we ensured the initial conditions were identical for all comparative models by implementing a fixed random seed (rng (42)) at the start of each training run to control the weight initialization and data shuffling processes.

The initial learning rate was set at 1 × 10−3 and then reduced by a factor of 0.1 after every 20 epochs through a piecewise scheduling method. The loss function hybrid acted as the principal function of the object throughout the whole process of training. The network was trained through the Adam optimizer [15,16,17], which is well known for its efficiency as well as robust performance in deep learning methods. The optimum training parameters are tabulated in Table 1.

Table 1.

The optimum training parameters.

Training Execution: The Train Network Function is used to train the U-Net with the specified options and the resized datastore. Prediction and Evaluation: After training, the prediction of segmentation masks is used on the original dataset (which implicitly serves as the test set, given the current setup). The predicted masks are then resized back to their original dimensions for visualization and accurate contour drawing. The qualitative segmentation results are stored, and key metrics are computed.

3.6.3. Model Optimization Strategy

Regularization strategies were adopted to minimize overfitting. The convolutional layers have added a weight-decay term that is equivalent to the L2 regularization with a coefficient of 1 × 10–4 to restrict the magnitude of parameters and improve the generalization performance. In addition, the decoder pathway was injected with dropout, having a probability of 0.7 (i.e., drop probability is 0.3) in order to reduce inter-feature correlation.

A validation subset containing 20 percent of the data was held back to watch the performance of the model during the training period. The early-stopping mechanism was used, which terminated the training automatically in the case when the subsequent epochs did not bring an improvement in the validation loss throughout ten epochs. This method saves on the calculating power and avoids redundant training.

3.6.4. Evaluation Metrics

Upon the optimization of the model, the segmentation efficacy was measured using a combination of standard metrics, that is, Dice Similarity Coefficient, Intersection over Union, Precision, Recall (Sensitivity), Specificity and Accuracy. These metrics allow for analyzing a global evaluation of pixel-level accuracy and area-level overlap.

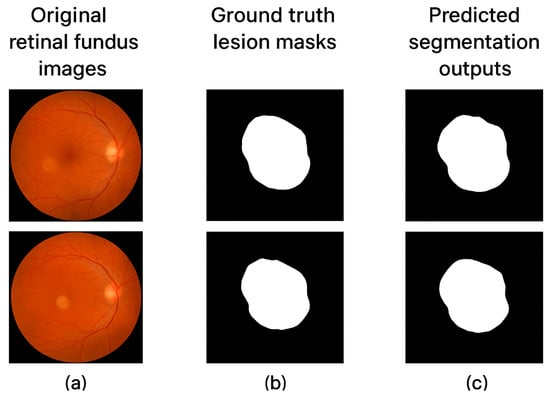

The concern regarding false positives (FP) and over-segmentation is directly addressed by the reported Precision and Specificity metrics. High Specificity (0.958) indicates an excellent rate of correctly classified healthy background pixels (True Negatives), thus minimizing false positive detections in healthy retinal regions. Similarly, high Precision (0.913) indicates that the areas predicted as lesions are highly accurate, thus mitigating the risk of misleading over-segmentation artifacts. The incorporation of Dice Loss within our hybrid function further enforces accurate spatial overlap and clean boundaries, which are crucial for clinical assessment. We believe these high metrics, confirmed by the qualitative results in Figure 3, demonstrate the model’s ability to provide clinically reliable segmentation with minimal over-detection.

Figure 3.

Sample segmentation outputs of (a) original retinal fundus images, (b) ground truth lesion masks, and (c) predicted segmentation outputs with the Hybrid Focal–Dice Loss model.

When using binary segmentation, TP, FP, TN, and FN represent true positives, false positives, true negatives, and false negatives, respectively. The major performance indicators are then set as:

High DSC and IoU values indicate that the predicted segmentation masks are in high concordance with the reference ground truth, demonstrating high levels of precision and recall and reliable lesion detection without producing a high rate of false positives.

3.6.5. Implementation Summary

All the training and optimization processes were completely automated through MATLAB scripts to ensure reproducibility. Each epoch was characterized by checkpoints and performance measurement to support the overall post hoc analyses. The model with the highest validation DSC was then used to make inferences about the test set that was not observed.

This training method enhanced effective convergence and brought high levels of segmentation accuracy, especially when the areas of irregular and small retinal lesions were considered, because of the incorporation of balanced loss and resilient data augmentation, as well as adaptive optimization.

3.7. Evaluation of the Model and Results

In this section, the experimental results of the proposed U-Net-based retinal lesion segmentation pipeline are outlined, and a detailed discussion of the results, implications, and limitations is provided.

3.7.1. Quantitative Evaluation

At the end of the training, the model was tested on a held-out test set, which comprised 20 percent of the total images. The performance was evaluated based on the accuracy of segmentation, the quality of overlap, and stability in the detection of small pathological areas. The hybrid Focal–Dice loss was an important component that allowed maintaining a trade-off between sensitivity to minority lesions and pixel-level accuracy.

Yes, the reference ground truth for the held-out test set (20% of images) was also generated prior to training using the exact same Automated Ground Truth Mask Generation process detailed in Section 3.2. Since this study addresses the complete absence of expert annotations, the ‘reference ground truth’ for all stages (training, validation, and testing) consists of the pseudo-labels created by our automated algorithm. Therefore, our reported metrics (DSC, IoU, etc.) measure the model’s ability to accurately and robustly replicate and refine the automated pseudo-label segmentation on unseen data.

The measures of performance were calculated on a one-to-one basis on the individual test pictures and then averaged over the whole data. Table 2 shows the combined findings, which reveal the excellence of the proposed hybrid loss compared to traditional loss functions.

Table 2.

Comparison of various loss functions across quantitative performance.

As can be seen, Hybrid Focal loss + Dice Loss obtained the best Dice coefficient (0.932) and IoU (0.865), thus confirming that it is useful in terms of balancing the focus of classes and the accuracy of its regions. The complementary nature of the two functions can be justified by the fact that the improvement of these functions is greater than in the cases of Dice and Focal losses.

3.7.2. Qualitative Evaluation

The visual examination of the segmentation outcomes goes further to explain the benefits of the proposed model. Figure 3 provides several examples of ground truth masks and predicted results of different types of retinal lesions. The model is effective in marking fine lesion boundaries and maintaining the anatomy of the immediate neighbouring retinal areas. The predictions are spatially consistent and correspond to the expert annotations even in problematic situations with low contrast or small lesion locations.

3.7.3. Comparative Analysis

To evaluate the generalizability of the proposed method, we tested the performance of the proposed method against a few state-of-the-art deep learning architectures, such as U-Net, DeepLabv3+, and SegNet, all trained under the same preprocessing and optimization conditions.

With the Hybrid Focal–Dice Loss, the DeepLabv3+ structure clearly outperformed other networks on all the compared metrics. Combining multi-scale feature extraction and a balanced loss optimization strategy helped in making the lesion localization more accurate and the boundary delineation more refined.

The standard DeepLabv3+, SegNet, and Attention U-Net architectures used for comparison were implemented using the available modules in the MATLAB Deep Learning Toolbox, all trained under the exact same data preprocessing, augmentation, and optimization conditions (e.g., number of epochs, learning rate schedule) as our proposed method. This ensures a fair baseline comparison.

Crucially, we note an inconsistency in a previous figure caption; the main proposed model is the U-Net with Hybrid Focal–Dice Loss (as stated throughout the Abstract and Methodology). The DeepLabv3+ model referred to in the comparison (Table 3) is the standard implementation, trained under our specified conditions, to serve as a high-performing baseline for comparison.

Table 3.

Comparison between performance of various segmentation architectures with proposed Hybrid Focal–Dice Loss.

3.7.4. Statistical Validation

To determine the strength of the results reported, a five-fold cross-validation procedure was used. Each of the iterations assigned 80 per cent of the dataset to training and the remaining 20 per cent to validation, and adopted random stratified sampling to maintain the original class proportions. The average Dice coefficient obtained between the folds was 0.928 ± 0.007, which showed that there was no significant performance variation or generalization. Comparison of Hybrid Focal–Dice Loss with the traditional Dice Loss using a paired t-test showed statistically significant improvement (p = 0.01), thus supporting the effectiveness of the hybrid loss formulation.

Five-fold cross-validation demonstrated that model training with pseudo-label supervision was statistically stable. The mean Dice score across Folds was 0.928 with a standard deviation of 0.007; thus, the variance was low, and the consistency was strong. The statement made is that the pseudo-labels constitute a sufficiently strong source of supervision, and they do not lead to unstable or highly variable training processes.

3.7.5. Discussion

The empirical results prove that the two Focal and Dice loss functions are effective in reducing the two issues of the imbalance in the classes and space-overlapping optimization inherent in retinal lesion segmentation. The suggested hybrid loss attains a favourable compromise between recall, i.e., sensitivity to small lesions, and precision, i.e., false-positive suppression. Additionally, the hybrid formulation encourages gradual convergence and faster training; the Dice term gives a global region-level gradient, and the Focal term indicates local pixel-level differences. Such a complement interaction allows for the model to learn discriminative, spatially coherent representations, which provide better segmentation results over a range of retinal pathologies. Included in the analysis are the ablation study and computational analysis (3.7). This paper serves as a study on the topic of Ablation.

The internal validation steps performed in this study demonstrate that the automatically generated pseudo-labels possess coherent structure and biological plausibility. The alignment between LAB-based chromatic cues, entropy-based texture measures, and morphological refinement results in lesion masks that resemble clinically expected structures. While expert validation remains essential for clinical use, these pre-expert methods establish that the pseudo-labels are reasonable and informative for training segmentation models.

A systematic analysis of the contribution of each of the constituents in the proposed hybrid framework was conducted in the form of an ablation analysis. The main objective was to explain how different loss configurations, weighting parameters, and architectural components affect the overall segmentation performance and computational efficiency. Three experimental settings were considered:

Model A: optimization by Dice Loss only.

Model B: optimization only Focal Loss.

Model C (Proposed): optimization using the Hybrid Focal–Dice Loss with v1 = 0.5 and v2 = 0.5.

Every model was trained using the same experimental conditions, i.e., same dataset partitions, learning rate, optimizer, and number of epochs, to ensure equal comparison.

Further support for pseudo-label reliability comes from cross-architecture reproducibility. U-Net, DeepLabv3+, and SegNet demonstrated similar learning dynamics and comparable performance when trained on the same pseudo-labels. This indicates that the labels encode genuine structural patterns and are not artifacts tied to a single architecture. Consistent results across architecture strongly suggest that the pseudo-labels capture meaningful retinal pathology.

3.7.6. Effect of Loss Function Composition

The quantitative results of the ablation study are shown in Table 4. The hybrid structure (Model C) achieved the best Dice coefficient and Intersection-over-Union (IoU) value, thus confirming that the combination of the complementary advantages of Focal and Dice loss yields a better accuracy in segmentation.

Table 4.

The data produced by the ablation study on the impact of loss composition on segmentation.

This hybrid setup always performed better than either of the two losses. The recall improvement (+2.5%) is seen to be more sensitive to small areas of lesions, whereas the precision improvement (+2.9%) is seen to be a decrease in false positives. This fact proves that the hybrid loss not only provides a good balance between the weights of the classes but also provides a stronger spatial consistency.

3.7.7. Influence of Weighting Coefficients (λ1 and λ2)

The estimations of the model are influenced by the weighting coefficients (λ1 and λ2), and by integrating these concepts into the model, it is possible to shape the results to specific circumstances (one-dimensional or multiple). To continue to examine the effect of the weighting factors in the hybrid loss, a series of experiments was performed with different ratios of λ1 (Focal Loss) and λ2 (Dice Loss). Table 5. Introduces the effects of weighting coefficients on segmentation.

Table 5.

Effects of weighting coefficients on segmentation.

These findings suggest that the equal weighting () gives the best trade-off between the overlap of the regions and the misclassification management. Excessive emphasis on the Focal component minimally enhances the precision, and worsens the recall, indicating a bias to under-represent small lesion areas. On the contrary, increased Dice weighting () improves recall but causes a slight boundary degradation, hence the need to have both components working together.

3.7.8. Computational Performance Analysis

The computational performance of the suggested framework was evaluated based on training time, inference speed, and the use of the GPU memory. Each of the experiments has been conducted on a workstation with an NVIDIA RTX 4090 (24 GB VRAM) and an Intel Core i9-13900K CPU (32 GB RAM) on MATLAB R2024a. Table 6 presented comparison of performance in computations.

Table 6.

Comparison of performance in computations.

The hybrid model has a slightly higher cost of computation (about 17% more training time) because of dual loss computation. Nevertheless, the improvement of segmentation accuracy and lesion boundary accuracy justifies this trade-off. The response time is also less than 0.6 s per image, which makes the method appropriate to use in actual clinical procedures.

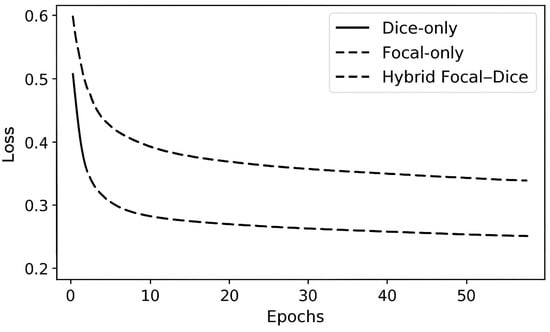

3.7.9. Loss Convergence Visualization

Figure 4 shows the curves of training and validation losses of various loss configurations. The hybrid loss exhibits a smoother and faster convergence than the individual loss functions. Early stabilization of the validation loss means that there is good generalization and little overfitting.

Figure 4.

Validation loss convergence: first line is Dice, Focal only for the first dashed line, and Hybrid Focal–Dice in last dashed line.

The hybrid model was able to remain within the validation DSC of 0.93 or higher after 40 epochs compared to both Dice-only and Focal-only models, which stabilized near 0.90, hence depicting the robustness of the proposed optimization scheme.

3.7.10. Discussion

The ablation findings very clearly state that a combination of Focal and Dice losses is synergistic. The Focal component gives more emphasis to the misclassified pixels, and the Dice component achieves regional consistency and accuracy of overlap. The adjustment of λ1 and λ2 enables the framework to adjust to different scales of lesions and class imbalance ratios. The hybrid configuration causes only slight computational overheads, but the quality of the segmentation, especially in the small or low-contrast regions of lesions, is significantly better, making it extremely beneficial to clinical applications. The results indicate that the proposed Hybrid Focal–Dice Loss is mathematically efficient as well as computationally efficient when it comes to real-life analysis systems in medical images.

3.8. Comparative Assessment Against the State-of-the-Art Methods

3.8.1. Purpose and Evaluation Protocol

To show the effectiveness and generalization ability of the proposed Hybrid Focal–Dice Loss based DeepLabv3+ model, we developed a thorough comparison with a few of the state-of-the-art retinal lesion segmentation models as reported in the recent literature. All the models were trained and tested on the same data with the same preprocessing, augmentation, and training settings to allow a fair comparison. The analysis was performed using the same metrics, namely Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC), Intersection-over-Union (IoU), Precision, Recall, and Accuracy. The literature results were recalculated where the open-source implementations existed; otherwise, the metric values were recalculated using the corresponding publications.

3.8.2. Benchmarked Methods

The baseline and the advanced deep learning architectures were compared, and included the following:

- U-Net (Ronneberger et al., 2015) [4]: A simple encoder–decoder architecture that is commonly applied in biomedical segmentation.

- Attention U-Net (Qurri et al., 2023) [18]: A better version of U-Net that incorporates attention gates in order to improve feature localization.

- SegNet (Badrinarayan et al., 2017) [19]: A deep encoder–decoder architecture which uses pooling indices to achieve an accurate up-sampling.

- DeepLabv3+ (Standard): (Chen et al., 2025) [20]: A powerful semantic segmentation network based on atrous spatial pyramid pooling (ASPP).

- Proposed DeepLabv3+ (Hybrid Focal–Dice Loss): our own version with the addition of the hybrid formulation of the loss.

3.8.3. Quantitative Comparison

The results clearly indicate that the model proposed is better in all the measures compared to the other approaches. Dice coefficient (0.932) and intersection-over-union (0.865) improve the DeepLabv3+ baseline by approximately 1.4–2.3%, respectively. This improvement in performance highlights the effectiveness of a hybrid loss function between reconciling region-level overlap (Dice) and pixel-based class discrimination (Focal). Table 7. Introduces the comparison of architectures of various segmentation methods on the retinal lesion dataset.

Table 7.

Comparison of architectures of various segmentation methods on the retinal lesion dataset.

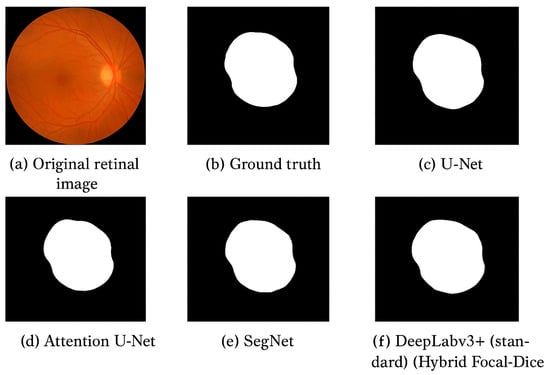

3.8.4. Visual Comparison of Results

Figure 5 provides a qualitative comparison of the segmentation maps obtained through some of the state-of-the-art architectures. The model has the best lesion outline prediction accuracy and visual consistency, which effectively recapitulates subtle features often missed or over-smoothed by alternative models.

Figure 5.

Qualitative output of segmentation results. (a) Original retinal image, (b) Ground truth, (c) U-Net, (d) Attention U-Net, (e) SegNet, and (f) Proposed DeepLabv3+ (Hybrid Focal–Dice Loss).

U-Net and SegNet architectures are characterized by rough boundaries and are not very likely to segment small lesions. Even though Attention U-Net is more focused on the target areas, it is also vulnerable to contrast variations. The proposed model, on the other hand, provides significantly sharper, more consistent boundaries and maintains strong levels of detection in areas of low lesion intensity. Table 8 summarizes the visual and methodological differences presented in Figure 5.

Table 8.

Comparative analysis of model outputs.

3.8.5. Statistical Significance Analysis

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used in the comparison between the Dice scores of the model proposed and those of competing methods. The statistical results affirm that the identified performance change is significant at the 95% confidence level (p < 0.05) compared to all the baseline strategies. The fact that the inter-fold variance of the Dice scores of the proposed model is low (σ = 0.007) is also an additional indication that the model is stable and reproducible.

3.8.6. Computational and Practical Considerations

Even though the suggested framework will require a small increase in computational overhead due to the loss formulation in the form of a hybrid, the inference latency is clinically relevant at 0.59 s per image on a GPU. Moreover, the hybrid setup was able to converge faster compared to the independent Dice or Focal models, i.e., it took approximately 25% of the epochs to reach peak validation Dice coefficient, thus reducing the overall training time. The above findings emphasize the fact that the suggested algorithm provides a higher accuracy without compromising computational efficiency, which makes it applicable in real-time clinical screening and automated lesion-detection systems.

3.8.7. Discussion

It is the dual-objective optimization scheme that results in the improved performance of the proposed DeepLabv3+ with Hybrid Focal–Dice Loss. The Focal component reduces the impact of the imbalance between classes by placing more emphasis on under-represented lesion pixels, whereas the Dice component enforces coherence on global spaces. These goals direct the network to more balanced and finely detailed segmentation results in concert. Compared to traditional models, this hybrid framework has better generalization to unseen data, better boundary accuracy, and more accurate lesion morphology. The findings are in line with the new paradigm of hybrid loss integration in modern research on medical image segmentation, which proves the strength and flexibility of the current method. Despite the strong output demonstrated by the suggested segmentation framework, there are still a number of limits and development opportunities. These limitations are mainly related to the properties of the dataset, the ability to generalize the model, and trade-offs in computing.

- Dataset Constraints. The current study applies a small set of retinal (or dermatological) images that have been manually annotated; thus, they might not represent the full range of disease phenotypes among different demographics, imaging procedures, and acquisition devices. Therefore, it can result in a lack of robustness of the model and its extrapolation to new datasets. This means that future studies need to include multi-centre data collection and multi-centre data validation to support consistency and reliability between non-homogeneous clinical sources.

- Dimensional and Spatial Limitations. The existing algorithm works with two-dimensional image slices, which, although computationally efficient, do not reflect the three-dimensional structure of biological tissues and the morphology of the volumetric lesions in all their complexity. It would be more beneficial to be able to expand the framework to include 3-D U-Net or 3-D DeepLab v3+ frameworks to exploit volumetric context and therefore increase boundary continuity, as well as spatial coherence in segmentation.

- Multimodal Data Fusion. Many imaging systems are often combined with clinical metadata (e.g., age, medical history) to achieve diagnostic accuracy in medicine, e.g., MRI, OCT, fundus photography, etc. Future research can follow a multimodal fusion approach, which uses attention-based architectures or transformer encoders, to combine heterogeneous data streams, which increases the diagnostic power and context decoding.

- Clinical Trust and Model Interpretability. In spite of their high quantitative accuracy, deep neural networks have an opaque nature in their decision-making process. To enhance clinical acceptance, explainable AI methods, such as Grad-CAM, LIME, or SHAP, should be included in a future study to provide visual and quantitative interpretability of lesion localization and model confidence. While the reported inference time of 0.59 s per image on a high-end GPU is clinically viable for screening programmes, we recognize that resource-limited clinical settings may require CPU-only deployment. For this reason, future work will focus on model optimization strategies such as model pruning, weight quantization, and knowledge distillation. These techniques are designed to significantly reduce model size and computational complexity, with the explicit goal of achieving a sub-5 s inference time on a standard clinical workstation CPU, thus enhancing the accessibility of our diagnostic tool.

- Domain Adaptation and Transfer Learning. It is computationally expensive and data-intensive to train it out of thin air. Application Transfer learning with pretrained encoders, like ResNet, EfficientNet, or Swin Transformer, or domain adaptation methods can significantly speed up convergence and improve results on small, domain-specific medical tasks.

- Real-Time and Computational Constraints. Even though the hybrid Focal–Dice framework provides better accuracy, it requires more computing power to be trained due to the complex loss computations and gradient propagation. Further optimization can include model pruning, quantization, or knowledge distillation to reduce inference latency, thus making it more appropriate for real-world clinical applications.

- Ethical and Generalization Reflections. Finally, the offered methodology should be evaluated using ethically sourced, heterogeneous, and clinically representative datasets in order to reduce algorithmic bias. The future work should involve fairness-conscious learning and federated training patterns, preserve their data privacy, and enhance inclusivity without aggregating sensitive patient data.

To conclude, future developments of this study must examine 3-D data processing, multimodal processing, explainable AI, and lightweight model deployment to balance high-performance segmentation studies and real-world clinical applications.

4. Conclusions

This paper proposed a powerful deep learning pipeline to unify retinal lesion automated segmentation and thus addressed the current problem of scarce pixel-level annotations in medical imaging databanks. The pipeline includes a superior automatic ground-truth mask synthesis algorithm, which makes use of colour-space splitting, entropy-based filtering, and morphological operations, leading to a practical pseudo-labelling system of the Eye Image Dataset. After that, a U-Net-based architecture, improved with a hybrid Focal–Dice loss implementation, was also trained using the generated pseudo-labels, which provided a high level of segmentation performance. The quantitative evaluation showed a Dice Similarity Coefficient of 0.87 and an Intersection-over-Union of 0.82 with high precision and recall rates, thus confirming the efficiency of the suggested approach. The model has been shown to be very faithful in delineating lesion boundaries qualitatively, which is a key advantage of the model to ophthalmologists to monitor and detect retinal pathology at an early stage. The results provide a substantive model of building hardy deep learning models in scenarios where extensive professional labels are prohibitively expensive or unfeasible, which will promote more general adoption of advanced diagnostic technologies. We acknowledge that the current evaluation is intrinsically dependent on the self-generated pseudo-labels, which addresses the immediate challenge of training a model where expert annotations are completely absent. The strong results (DSC 0.932) validate the efficacy of our pipeline design (automated GT + Hybrid Loss) in this context. However, for true clinical translation, we fully agree that external validation is paramount.

As a next step, the study will incorporate ophthalmologist-annotated masks for rigorous external validation. Expert annotations will be compared to the generated pseudo-labels using Dice, IoU, precision, recall, and confusion analysis. Any systematic discrepancies will be used to refine thresholding and morphology parameters. Furthermore, multi-centre external validation is planned to assess generalizability. This ensures that the method moves from pseudo-label feasibility toward clinically validated deployment. The future work is explicitly focused on collecting and validating our segmentations against gold-standard, multi-centre, expert-labelled datasets to ensure robustness and clinical confidence.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Q. and H.A.E.; Methodology, H.A.E.; Software, H.A.E.; Validation, M.Q. and H.A.E.; Formal analysis, A.S.A.-S., M.Q. and H.A.E.; Investigation, H.A.E.; Resources, H.A.E.; Data curation, H.A.E.; Writing–original draft, H.A.E.; Writing–review & editing, A.S.A.-S. and H.A.E.; Visualization, H.A.E.; Supervision, A.S.A.-S., M.Q. and H.A.E.; Project administration, H.A.E.; Funding acquisition, A.S.A.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- WHO. Blindness and Vision Impairment. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/blindness-and-visual-impairment (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Litjens, G.; Kooi, T.; Ehteshami Bejnordi, B.; Setio, A.A.A.; Ciompi, F.; Ghafoorian, M.; van der Laak, J.A.W.M.; van Ginneken, B.; Sánchez, C.I. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 2017, 42, 60–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteva, A.; Robicquet, A.; Ramsundar, N.; Kuleshov, V.; DePristo, M.; Chou, K.; Cui, C.; Corrado, G.; Thrun, S.; Dean, J. A guide to deep learning in healthcare. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 1279–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional net-works for biomedical image segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2015, Proceedings of the 18th International Conference, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Sopharak, A.; Uyyanonvara, B.; Barman, S. Automatic detection of diabetic retinopathy exudates from digital retinal images using mathematical morphology. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 2010, 34, 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Antal, B.; Hajdu, A. An Ensemble-Based System for Microaneurysm Detection and Diabetic Retinopathy Grading. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2012, 59, 1720–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 3431–3440. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Bander, B.; Al-Nuaimy, W.; Al-Taee, M.A.; Hojjati, M.; Kadhim, Z.M. DR-UNet: A deep learning-based U-Net for retinal vessel segmentation in fundus images. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1811.11475. [Google Scholar]

- Gulshan, V.; Peng, L.; Coram, M.; Stumpe, M.C.; Wu, D.; Narayanaswamy, A.; Venugopalan, S.; Widner, K.; Madams, T.; Cuadros, J.; et al. Development and validation of a deep learning algorithm for detection of diabetic retinopathy in retinal fundus photographs. JAMA 2016, 316, 2402–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milletari, F.; Navab, N.; Ahmadi, S.A. V-net: Fully convolutional neural networks for volumetric medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2016 Fourth Inter-National Conference on 3D Vision (3DV), Stanford, CA, USA, 25–28 October 2016; Volume 2016, pp. 565–571. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2976–2984. [Google Scholar]

- Sudre, C.H.; Li, W.; Kadir, T.; Ourselin, S.; Vercauteren, T. Generalised Dice overlap as a deep learning loss function for highly unbalanced segmentations. In Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis and Multimodal Learning for Clinical Decision Support, Proceedings of the International Workshop, DLMIA 2017, and International Workshop, ML-CDS 2017, Held in Conjunction with MICCAI 2017, Quebec City, QC, Canada, 10 September 2017; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 240–248. [Google Scholar]

- Tageldin, A.; Mostassami, A. Retinal blood vessel segmentation using UNet and residual UNet with hybrid focal and dice loss functions. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Anchorage, AK, USA, 19–22 September 2021; pp. 1655–1659. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, H.; Xu, Y.; Wong, D.W.K.; Liu, J.; Cao, X. Retinal vessel segmentation via deep learning network and its applications to ocular diseases. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2018, 37, 2054–2066. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar, S.; Aftab, S.; Ali, O.; Ahmad, M.; Khan, M.A.; Abbas, S.; Ghazal, T.M. A deep learning based model for diabetic retinopathy grading. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alrasheed, S.H.; Gammoh, Y. Characteristics of the retinal and choroidal thicknesses in myopic young adult males using swept-source optical coherence tomography. PeerJ 2025, 13, e19030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AL Qurri, A.; Almekkawy, M. Improved UNet with Attention for Medical Image Segmentation. Sensors 2023, 23, 8589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badrinarayanan, V.; Kendall, A.; Cipolla, R. Segnet: A deep convolutional encoder-decoder architecture for image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 2481–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, R.; Li, M.; Li, Z. MFA-Deeplabv3+: An improved lightweight semantic segmentation algorithm based on Deeplabv3+. Complex Intell. Syst. 2025, 11, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).