Abstract

This study tested the impacts of large language model (LLM) addiction on the mental health of university students, employing gender as a moderator. Data was collected from 750 university students from multiple fields of study (i.e., business, medical, education, and social sciences) using a self-administered questionnaire. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was employed to analyze the collected data; this study tested the impacts of three LLM addiction dimensions—withdrawal and health problems (W&HPs), time management and performance (TM&P), and social comfort (SC)—on stress, depression, and anxiety as dimensions of mental health disorders. Findings indicate that TM&P and SC had a significant positive impact on stress, depression, and anxiety, implying that overdependence (as an early-stage precursor and behavioral antecedent of LLM addiction) on LLMs for academic achievements and emotional reassurance contributed to higher levels of psychological distress. On the contrary, W&HP showed a weak but significant negative correlation with stress, signaling a probable self-regulatory coping approach. Furthermore, gender was found to successfully moderate several of the tested relationships, where male university students showed stronger relationships between LLM addiction dimensions and adverse mental health consequences, whereas female university students proved greater emotional constancy and resilience. Theoretically, this paper extends the digital addiction frameworks into the AI setting, highlighting gendered models of emotional exposure. Practically, this study highlights the urgent need for gender-sensitive digital well-being intervention programs that address the overuse of LLMs, a prominent category of generative AI. These outcomes emphasize the significance of balancing technological involvement with mental health protection, determining how LLM usage can specifically contribute to digital addiction and related psychological consequences among university students.

1. Introduction

The emergence of large language models (LLMs), particularly ChatGPT (GPT-4) OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA and Gemini 1.5, Google LLC, Mountain View, CA, USA, has substantially transformed the academic environment of university education. These artificial intelligence (AI) tools are frequently used by students on a daily basis for academic purposes, including assignment creation, as research assistants, and as emotional connections [1,2]. While those AI tools can improve accessibility and efficiency, empirical evidence argues that rigorous or intensive practice with them might cause patterns of addictive behavior and possibly harm university students’ mental health [3]. Prior research on electronics addiction has argued that extreme dependance on internet technologies—such as social media and online gaming—can cause higher levels of anxiety, stress, depression, and lower levels of psychological well-being [4,5]. At the same time, structured and pedagogically designed online tools, such as gamified learning platforms or interactive digital classrooms, have been demonstrated to enhance student cognition, engagement, and learning outcomes [6,7,8]. Nonetheless, the conversational aspects of LLMs can introduce new settings that distinguish them from earlier models of digital AI tools. University students may use LLMs as an intelligent tool that provide not only large amounts of information but also offer emotional reassurance and companionship [9]. These human-like AI interactions—where university students use LLMs as responsive, supportive, or companion-like tools—may foster emotional habits and bonds, theoretically contributing to addictive patterns of usage [10]. However, empirical evidence confirming this phenomenon remains incomplete and requires further investigation.

Previous research on digital AI addictions has found that excessive usage of internet-based platforms might have harmful influence on quality of life. In a study that covered more than 100 studies, the findings identified that the occurrence of internet addiction among higher education students is close to 42%, with significant associations with depression and anxiety signs [10]. In KSA settings, one research paper argued that more than 50% of medical students exhibited psychological distress due to extreme internet usage [11]. These results together claimed that students in higher education displayed a high-risk cluster for digital AI addiction and related mental health disorders. While previous research papers on smartphone or social media addiction are well-established, studies exploring LLM overuse are still in their initial phases. The interactional, human-like aspects of LLMs create a context where the link between operational usage and emotional reliance can blur. Despite these warnings, empirical evidence exploring addictive LLM overdependence (as an early-stage precursor of LLM addiction) and links to mental health disorders remain scarce, which is a gap the current study tried to fill.

The motivation for conducting such a study stems from the developing usage of LLMs in the higher education context and the lack of empirical evidence exploring their psychological and behavioral consequences. This study seeks to accomplish two major objectives. First, it investigates the relationships between LLM addiction and mental health outcomes (anxiety, depression, and stress). Second, it tests the moderating role of gender in these specific relationships. Therefore, this study is guided by the following two questions: (1) How is LLM addiction linked to mental health outcomes? (2) Can gender moderate the link from LLM addiction to mental health consequences, and if so, in what way? These two questions aim to extend and diversify the forms and mechanisms of digital addiction, thereby building upon—rather than replacing—the established body of literature, which has mainly focused on general AI attitudes and performance influences, but not on the psychological or gendered outcomes of addictive LLM correlations. Therefore, the contributions of this research paper are twofold. First, it offers empirical evidence linking LLM addiction to university students’ mental health outcomes. Second, it highlights gender as a moderating variable, contributing to the broader literature on gender differences in emotional consequences and digital behavior.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

From a theoretical standpoint, several frameworks can serve as the theoretical basis of the current study. The behavioral addiction framework introduced in [12] can offer the main conceptual framework, through which LLM addiction is defined as extreme usage causing withdrawal, conflict, and missing control. Likewise, the “Uses and Gratifications theory” introduced in [13] can be used to explain the motivational factors through which university students may engage with LLMs to satisfy and fulfill their emotional, cognitive, or social needs, such as learning, help, support, or friendship. Over a long time, continual gratification can strengthen habitual use and lead to dependency. These groundworks can jointly explain why several features that make LLMs helpful can also make them potentially addictive.

As per the “component model” of the behavioral addiction framework introduced in [14], the withdrawal dimension is a central element linking addiction to dysfunction and distress. When applied to digital tool addiction (i.e., LLM addiction), withdrawal signs may appear as anxiety, irritability, restlessness, loss of control, or health issues when connection is limited. Over a longer time, such withdrawal can foster greater craving and nonstop use, thus generating a vicious cycle that fosters the psychological distress [3]. This theoretical background can offer a logical explanation for expecting that withdrawal/health problems from LLM overuse can be positively correlated with stress, anxiety, and depression. Evidence in youth and student samples reveals that digital technology addictions are associated with higher odds of poor self-rated health issues, sleep complications, anxiety, and stress compared to non-addicted peers [15]. This argument is strengthened in the higher education environment, as university students frequently face several stressors (i.e., high level of academic workload) so when an LLM student faces withdrawal/health issues, it increases the aggregate burden, thereby making university students more vulnerable to depression, stress, and anxiety [16]. Thus, the context of university students amplifies the application of the hypotheses. Hence, we can propose the following hypotheses:

H1a.

Withdrawal symptoms as a dimension of LLM addiction are positively associated with stress (as a dimension of mental health disorder).

H1b.

Withdrawal symptoms as a dimension of LLM addiction are positively associated with depression (as a dimension of mental health disorder).

H1c.

Withdrawal symptoms as a dimension of LLM addiction are positively associated with anxiety (as a dimension of mental health disorder).

The extreme exploitation of digital technologies (such as LLMs) is likely to damage students’ time management and performance due to delayed academic tasks and degraded self-control [17,18]. When university students spend excessive time engaging with LLMs instead of committing to scheduled study, attending classes, or fulfilling academic obligations, they may face lower academic performance, missed deadlines, or reduced productivity [19]. Such failures in academic performance are then converted into stressors, leading to higher levels of stress, anxiety and depressive signs [20]. Drawing on the “Conservation of Resources” (COR) theory, extreme use of LLMs consumes time and cognitive energy, thus fostering feelings of loss and psychological stress [20,21]. Previous evidence studies confirmed the correlation between poor time management and technology misuse with adverse impacts on mental health disorders. Internet addiction among medical university students was found to be positively correlated with high levels of stress and negatively correlated with academic performance [17,22,23]. In the context of LLM usage, the improvement of “ease” and “immediacy” it offers might intensify a high level of risk as university students might depend on LLMs for obtaining speedy answers, decreasing their study engagement, or delaying assignments [24]. This avoidance of main academic practices can lead to performance shortages and scheduling disturbances [25]. When students recognize that their outcomes are compromised, they may feel stressed about future deadlines, nervous about falling behind, or depressed about potential academic failure [26]. Accordingly, we can propose the hypotheses below:

H2a.

Time management and performance (as a dimension of LLM addiction) are positively associated with stress (as a dimension of mental health disorder).

H2b.

Time management and performance (as a dimension of LLM addiction) are positively associated with depression (as a dimension of mental health disorder).

H2c.

Time management and performance (as a dimension of LLM addiction) are positively associated with anxiety (as a dimension of mental health disorder).

The social comfort aspect of the MEUS describes the level to which people rely on LLMs for emotional support, friendship, and social support. While LLMs can offer instant feedback and minimize feeling of loneliness, continued dependence on them as an alternative for actual human interaction can create social withdrawal, emotional separation, and eventually poorer mental health consequences [27,28]. People repeatedly engage with online networks or digital platforms to fulfill their unfulfilled or unmet social or psychological needs [29]. When employees use LLMs as a tool for comfort, endorsement, or avoidance of real-life challenges, this attitude may momentarily relieve distress but also strengthen the avoidance of genuine interpersonal relationships [16]. Over a longer time, this compensatory process fails to fulfill the underlying social needs and may instead worsen the feelings of stress, loneliness, and depression [30]. Previously available evidence confirmed this relationship. Lu et al. [27] found that people who repeatedly interacted with AI tools for emotional support reported heightened level of social dependency and reduced real-world relationships, both of which produce higher levels of stress and anxiety. Likewise, a longitudinal study conducted in [31] suggests that overdependence on AI-based tools for social interaction can lead increased depressive symptoms and higher levels of social isolation among higher education students. For university students, who are in the developmental phase for creating social identity and peer connections, dependence on LLMs for friendship can hinder adaptive coping and social incorporation, thereby worsening stress, anxiety, and depression symptoms [4]. Therefore, the assumption that social comfort (as a factor of LLM addiction) is positively correlated with higher levels of stress, anxiety, and depression is well adjusted empirically and theoretically and hypothesized below:

H3a.

Social comfort (as a dimension of LLM addiction) is positively associated with stress (as a dimension of mental health disorder).

H3b.

Social comfort (as a dimension of LLM addiction) is positively associated with depression (as a dimension of mental health disorder).

H3c.

Social comfort (as a dimension of LLM addiction) is positively associated with anxiety (as a dimension of mental health disorder).

Previous research has frequently argued that gender can moderate the link from digital addiction to the psychological consequences [27,28]. Males repeatedly show advanced levels of gaming and technology addiction, while females reported stronger correlations between communication or social use of technology and depression or anxiety [32]. Given that LLMs can offer a relational interface, female students could be at higher levels of risk of psychologically driven misuse and mental distress. Nonetheless, empirical evidence of gender moderation within LLM settings is still absent, marking a significant gap that the present study addresses. Accordingly, the hypotheses below can be tested:

H4-H5-H6.

Gender moderates the relationship between withdrawal symptoms and mental health disorders (stress–depression–anxiety).

H7-H8-H9.

Gender moderates the relationship between time management and performance and mental health disorders (stress–depression–anxiety).

H10-H11-H12.

Gender moderates the relationship between social comfort and mental health disorders (stress–depression–anxiety).

3. Methods

This study used a cross-sectional method, with a self-structured survey developed to assess the proposed hypotheses. This cross-sectional method is deemed adequate as it permits the collection of a large amount of data within a short time and allows for the evaluation of the assumed relationships using the PLS-SEM data analysis technique [33]. LLM addiction was operationalized using Huo et al.’s [34] Microblog Excessive Use Scale (MEUS). The scale has 10 variables and three dimensions. The first dimension is named withdrawal and health problems (W&HPs) and has four reflective items; a sample item says, “How often do you choose to spend more time on LLMs over going out with others”. The second dimension is time management and performance (TM&P) and it has three reflective variables; a sample variable is “How often do you neglect your daily responsibilities because of your use of LLMs”.

The third dimension of the MEUS is social comfort and it has three reflective variables; a sample question is “How often do you feel comfortable interacting with LLMs?” The respondents were asked to answer the questions on a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 indicated “never” and 5 indicated “always”. Likewise, mental health disorder was operationalized by three dimensions (stress, depression, and anxiety) based on the work of Lovibond and Lovibond’s short-version DASS-21 scale [35]. DASS-21 is recognized as one of the most widely employed scales to evaluate mental health disorders correlated with the addiction’s behavior [36,37,38]. The first dimension of the DASS scale has 7 items measuring stress symptoms; an example item is “I found it difficult to relax”. Likewise, the second DASS dimension is depression, and it has 7 reflective items measuring depression symptoms; an example variable is “I felt that I had nothing to look forward to”. The last and third dimension of the DASS scale is anxiety, and it has 7 items; an example item is “I felt I was close to panic”. DASS-21’s scale enables scholars to measure the psychological states that may result from extreme LLM usage. University students were asked to evaluate the level of agreement with each question using a 4-item Likert scoring method, where 0 indicated “no agreement” and 3 indicated “a high level of agreement”. The data were collected from several SA universities that represent the country’s five main regions: Northern Border University (north); Jazan University (south); King Faisal University (east); Umm Al-Qura University (west); and Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (center). A total of 920 questionnaires were distributed, and 750 were retained for further analysis. Exclusion criteria were applied to answers that were incomplete or responses with a high number of missing answers. Additionally, students who declared that they were not regular users of LLMs (i.e., reporting minimal or no engagement with LLMs in academic or daily tasks) were excluded to safeguard that the final sample accurately reflected students with relevant and meaningful exposure to LLM. The demographic statistics of participants covered students’ gender, age level, academic level, and discipline of study. The majority of participants were undergraduate students (90%), while a smaller proportion (10%) were postgraduate students. The age level was mostly within the normal age range of 18–25 years for university students. Both male (48%) and female (52%) students were represented in the study sample, ensuring equal gender representation. The inclusion of respondents was from multiple fields of study (i.e., business, medical, education, and social sciences), further strengthening the generalizability of the findings.

4. Results

The main employed data analysis technique was PLS-SEM with the SmartPLS v4 program. PLS-SEM is broadly suggested over the traditional CB-SEM under conditions where (1) the research main objective is prediction rather than theory confirmation [36]; (2) the model has multiple latent constructs, multidimensional factors, or hierarchical structures [37]; and (3) the data may show non-normally distributions [36]—all of which apply to the current study. Our model has several latent unobserved variables measured by reflective items (LLM addiction in four dimensions and three dimensions of mental health), along with the moderating variables (gender). Additionally, PLS-SEM is more adequate when the main aim is to explore the explained variance (predictive approach) rather than testing a well-established theory: LLM addiction.

We followed Henseler and Sarstedt’s [39] instructions for the two-tier process in analyzing the data using the PLS-SEM approach. The first tier was conducted to assess the outer measurement model in terms of scale validity and reliability, followed by the second tier to evaluate the path analysis in the inner structural model for hypothesis testing, where a p value less than 0.05 indicates an accepted hypothesis.

4.1. Tier One: Measurement Model Evaluation

We calculated the model reliability and validity through the evaluation of the measurement model in PLS-SEM, following the criteria introduced in [40]. These criteria include “composite reliability” (CR) and the “average variance extracted” (AVE) for each dimension. Table 1 depicts the factor loadings (FLs), C.R., “Cronbach’s α”, and the AVE. The measurement scale reliability exhibited a satisfactory results as all FLs were above the threshold score of 0.5 [41]. According to the CR values, all values exceed the lowest recommended score of 0.70, as suggested by Hair et al. [42]. As a result, the model meets the criteria for construct reliability. Regarding the scale convergent validity, the AVE scores shown in Table 1 are found to be above the recommended score of 0.50, as suggested in [43]. To confirm the scale discriminant validity, two criteria were assessed [44]: (1) the HTMT “heterotrait–monotrait ratio of correlations” (Table 2), which should be under the value of 0.90 [45]; (2) the Fornell–Larcker criterion (Table 3), where all AVE square roots (diagonal values) exceed their intercorrelations with any other factors in the model (below the diagonal values), supporting the discriminate validity of the measurement model.

Table 1.

Convergent and discriminant validity results.

Table 2.

Discriminant validity matrix—heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT).

Table 3.

Discriminant validity—Fornell–Larcker criterion.

4.2. Tier-Two: Hypothesis Testing

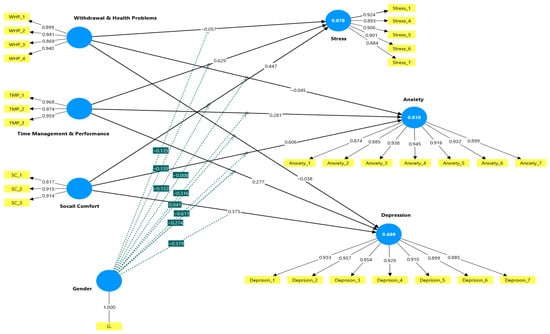

Before testing the research hypotheses in PLS-SEM, the structural model was assessed in terms of its explanatory and predictive power, using several criteria as suggested in [46,47]. First, the “coefficient of determination” (R2) was inspected to evaluate the model’s explanatory power of the endogenous (dependent) variables caused by the exogenous (independent) variables. All endogenous variables, as shown in Figure 1, have high R-squared values (stress, R-squared = 0.878; depression, R-squared = 0.689; and anxiety, R-squared = 0.81), indicating a stronger explanatory power of the model. Second, the model’s “predictive relevance” (Q2) was calculated employing the “Stone–Geisser test” by running the blindfolding procedure. A Q2 score greater than zero for an endogenous variable indicates that the model has sufficient predictive relevance for that variable (stress, Q2 = 0.873; depression, Q2 = 0.549; and anxiety, Q2 = 0.764). Furthermore, the collinearity issue was tested by inspecting the values of VIF to ensure that multicollinearity among the study predictors is within acceptable limits (VIF < 5). As depicted in Table 1, all VIF values are below 5.

Figure 1.

The research model of LLM addiction, mental health, and gender moderation. Note: WHP_1–WHP_4: items that measure withdrawal and health problems; TMP_1–TMP3: items that measure time management and performance; SC_1–SC-3: items that measure social comfort;  direct effects;

direct effects;  moderating effects.

moderating effects.

direct effects;

direct effects;  moderating effects.

moderating effects.

After confirming the model’s explanatory and predictive power, the path coefficients and their related significance p-values were examined by running the bootstrapping option in PLS-SEM to support or reject the study hypotheses. The PLS-SEM report indicated that W&HP (as a dimension of LLM addiction) has a weak, negative, and significant impact on stress (β = −0.057, t = 4.513, p < 0.01), rejecting H1a. Similarly, W&HP failed to significantly impact depression (β = −0.038, t = 1.360, p = 0.174) and anxiety (β = −0.045, t = 1.780, p = 0.075) as dimensions of mental health disorder, rejecting H1b and H1c, as seen in Table 4

Table 4.

Results of research hypotheses.

Furthermore, the PLS-SEM results indicate that TM&P (as a dimension of LLM addiction) has a significant positive impact on stress (β = 0.629, t = 15.008, p < 0.001), depression β = 0.277, t = 4.337, p < 0.01), and anxiety (β = 0.281, t = 6.509, p < 0.001), supporting H2a, H2b, and H2c. Similarly, SC (as a dimension of LLM addiction) was found to have a significant positive impact on stress (β = 0.447, t = 12.150, p < 0.001), depression (β = 0.375, t = 5.820, p < 0.001), and anxiety (β = 0.606, t = 15.768, p < 0.001), supporting H3a, H3b, and H3c.

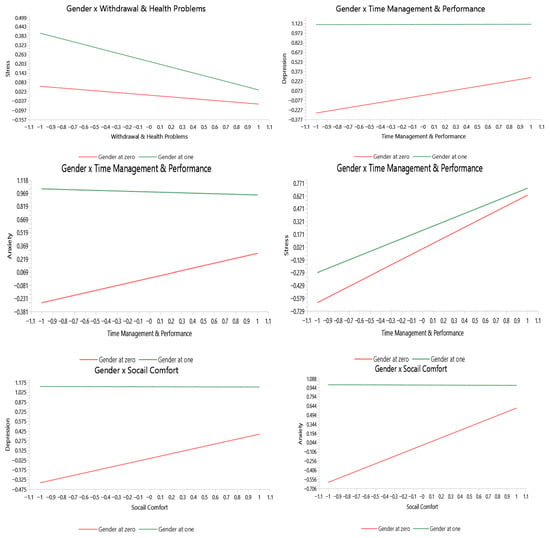

Gender (coded as 0 = male, 1 = female) was employed in this study as a moderator (see Figure 2). As shown in Table 4 and Figure 2, several significant differences between males and females were observed across the tested relationships. The findings indicate that gender did not moderate the effect of W&HP (as a dimension of LLM addiction) on depression and anxiety (dimensions of mental health disorder). Similarly, gender failed to moderate the impact of social comfort on stress. However, as seen in Figure 2, for females (green line), there is a negative slope, indicating that as withdrawal and health problems decrease, stress also decreases. This suggests that, among female university students, greater signs of W&HP (from LLM interactions) are correlated with lower levels of stress. For males (red line), the slope line is almost flat, signaling no significant association. In other words, changes in W&HP appear to have little or no impact on male students’ stress levels. This pattern signals a significant moderate effect of gender on the relationship between W&HP and stress.

Figure 2.

Simple slope for moderating impacts.

Slope analysis of the moderation effects revealed that gender can moderate the impact of TM&P (as a dimension of LLM addiction) on the three dimensions of mental health disorder (stress, depression, and anxiety). These moderation effects suggest that male students may experience higher levels (compared to females) of stress, depression, and anxiety as their time management and performance demands increase (because of the dependence on LLM-based interactions). Similarly, gender was found to have a significant moderating effect on the impact of social comfort on depression and anxiety. In particular, the positive impacts of social comfort on depression and anxiety are substantial and strong among males, but non-significant or weak among females. Conversely, female students showed more emotional stability, declaring that their depression and anxiety levels stayed relatively constant regardless of the changes in social comfort derived from LLM overuse.

5. Discussion and Implications

This study explored how different aspects of large language model (LLM) addiction can impact various aspects of students’ mental health disorders (stress, depression, and anxiety). Employing the PLS-SEM approach, this study’s findings reveal that W&HP (as a dimension of LLM addiction) were not positively related to stress, depression, or anxiety as initially proposed. These results might reflect contextual factors specific to university students rather than a fundamental weakness of the theoretical framework or incorrect operationalization. University students often develop self-regulation approaches to handle their academic pressure, social commitments, and digital involvement. Such adaptive strategies may alleviate the psychological impact of LLM withdrawal symptoms, leading to the negative or non-significant associations detected. This aligns with social cognitive theory, which posits that self-regulatory capabilities can safeguard adverse consequences in the presence of potentially stressful behaviors.

More specifically, the findings indicate that the withdrawal and health problem (W&HP) dimension of LLM addiction had a significant but weak negative impact on stress. However, W&HP failed to impact depression or anxiety significantly. This negative and weak relationship suggests that university students with higher levels of W&HP toward LLM may experience slightly lower stress levels, possibly due to superior awareness or self-regulation in managing their digital experiences. Comparable evidence was confirmed by Shen et al. [48], who argued that self-regulatory systems might mitigate the stress levels caused from digital abuse. In contrast, the insignificant relationship with depression and anxiety indicators might exhibit that W&HP is not a strong predictor of chronic mental health symptoms. Previous evidence (e.g., [22,49]) also highlighted that while digital AI addiction is correlated with reduced mental health, the direction of effects varies across different aspects and coping strategies.

The findings further show that the TM&P aspect of LLM addiction had a significant positive influence on stress, depression, and anxiety. These outcomes advocate that higher levels of TM&P are linked with extreme involvement with LLMs and can worsen the psychological distress status among university students. When academic responsibilities are delayed due to overdependence (as an early-stage precursor antecedent of LLM addiction) on AI technologies, university students may encounter heightened levels of stress caused by skipped important deadlines or decreased academic productivity. These results align with a prior argument that poor TM&P are a significant predictor of stress and burnout among university students [18,50]. Furthermore, the positive association between TM&P with anxiety and depression revealed that overreliance on LLMs for cognitive adjustment might result in a maladaptive behavior. A study conducted by Elhai et al. [51] argued that problematic digital AI use is positively correlated with anxiety and depressive symptoms due to intensified social loneliness and cognitive burden.

The PLS-SEM results also report that SC as a dimension of LLM addiction had a significantly positive influence on stress, depression, and anxiety. These findings advocate that students’ cumulative overdependence on LLMs for social connections and emotional reassurance is associated with greater levels of psychological distress. These outcomes suggest that as higher education students seek more social comfort through LLM-based platforms, they may unintentionally lessen their involvement in real human interactions and social coping mechanisms. This claim is consistent with the displacement assumption, which implies that digital interactions can substitute (eventually erode) meaningful offline connectedness, causing loneliness, depression, and stress signs [52,53]. Moreover, the high coefficient between social comfort and anxiety revealed that while LLM tools might offer short-term emotional reprieve, they can strengthen avoidance behaviors. These avoidance attitudes are related to higher levels of anxiety in the context of digital relationships [32,54,55]. LLM tools, even with their sympathetic conversational capacities, lack real emotional and reciprocity aspects. Furthermore, the noted link with stress suggests that continuous digital involvement may generate psychological exhaustion due to the constant accessibility of non-human interactions [56].

The PLS-SEM report presented the results of the moderating role of gender on the tested relationships and revealed a significant moderating impact of gender (male–female) on the relationship between W&HP and stress. The moderating analysis report showed that for female students (the green line in Figure 2, above the left corner), there is a negative slope, indicating that as W&HP increases, stress levels decrease. This slope suggests that among female university students, higher signs of W&HP symptoms (caused by extreme LLM usage) are unexpectedly related to lower levels of stress. On the contrary, for male university students (red line), the slope is almost flat, indicating no significant correlation between W&HP and stress. Specifically, the variation in W&HP is shown to have no or little impact on stress levels among male students. This unexpected relationship among females’ students revealed that those who exhibit stronger W&HP signs have already achieved an adaptation phase toward the stressors associated with LLM overuse. Previous research has shown that in some circumstances, people with higher digital involvement may experience temporary emotional release or distraction from daily stress through online experiences, thus experiencing low stress in the short term [4,29,57]. For male university students, the insignificant relationship indicated that their stress levels are generally unaffected by W&HP symptoms from extreme LLM use. This might exhibit different coping mechanisms, as males often participate with digital technology in a more task-focused ways, making them less emotionally responsive to W&HP symptoms [3,58,59].

Furthermore, the slope analysis in the PLS-SEM report revealed that gender can significantly moderate the impact of TM&P (a dimension of LLM addiction) on the three factors of mental health disorder (stress, depression, and anxiety). These findings reveal that male university students have higher levels of stress, anxiety, and depression than female university students as their TM&P increases, mainly when these challenges resulted from cumulative reliance on LLM-based tools. This is in alignment with previous research suggesting that males tend to identify self-worth more strongly than females through task attainment and performance consequences, making them more vulnerable to stress, anxiety, and depressive signs when performance expectations are unfulfilled [59,60].

The PLS-SEM slope report further indicated that gender can significantly moderate the influence of SC (the third dimension of LLM addiction) on depression and anxiety among university students. In other words, the positive correlations between SC and both anxiety and depression were found to be significant and strong among male university students, but non-significant or weak among female university students. These findings suggest that for males, increased dependence on LLMs for SC tends to foster the feeling of depressive and anxious symptoms, whereas females appear to sustain higher emotional stability in the perceived SC resulting from excessive LLM usage. When male university students employ LLMs as substitutes for real social connections, they may face social disconnection, causing heightened emotional distress such as anxiety and depression [61]. Conversely, female university students are more likely to pursue emotional reassurance and relational bonds through multiple interpersonal methods, including family and peers, which safeguards them from overdependence on LLMs for emotional support [59,62].

This paper offered several eminent contributions to the evolving literature on LLM addiction and mental health disorders among university students. First, the positive significant correlations between LLM addiction dimensions (TM&P and SC) and mental health outcomes (stress, depression, and anxiety) extend previous theories of digital addiction [3,63] to the novel setting of AI-based interactional instruments. Unlike the traditional tools of digital reliance such as gaming addiction or social media, LLM addiction involves cognitive and emotional dependence on generative AI for academic reassurance, emotional support, and problem solving. Second, this study contributed to a gender-based framework of AI technology usage and emotional vulnerability [9,62,64] by empirically confirming gender as a significant moderating dimension. The findings show that male university students are more emotionally sensitive than female university students to changes in TM&P and SC, indicating higher stress, depression, and anxiety symptoms when their academic performance or SC needs rely heavily on LLM engagement. Third, by linking the factors of LLM addiction with specific mental health outcomes, this study strengthens the dual-path model of digital involvement [14], indicating that while LLMs can improve efficiency and learning outcomes, excessive usage may have detrimental psychological impacts. From a practical perspective, these findings underscore the crucial need for educational managers, mental health consultants, and policymakers to address the psychological challenges associated with overreliance on LLM usage. University leaders should incorporate digital AI well-being education program into their courses, facilitating students’ recognition of the early indicators of cognitive overreliance and emotional dislocation linked with LLM overuse. For mental health specialists, these results can offer a framework for advancing gender-sensitive interventions. Since male university students were found to be more psychologically vulnerable to performance and SC dependencies on LLMs, this paper ultimately calls for the constant monitoring of AI-associated psychological influences. As generative AI tools progress rapidly, recognizing their social, behavioral, and emotional, outcomes are necessary for sustainable adoption in higher education.

6. Conclusions

This paper sought to test how different aspects of LLM addiction (W&HP, TM&P and SC) can impact the mental health (stress, depression, and anxiety) of university students. Based on PLS-SEM, the findings reveal that TM&P and SC had positive and significant impacts on stress, depression, and anxiety. These results highlight that university students who over-depend on LLM usage to accomplish their academic duties or meet social and emotional needs are inclined to practice higher levels of mental distress. However, W&HP exposed significant but weak negative relationships with stress, indicating that self-awareness and restrained withdrawal from overreliance on LLMs may play a protective role against stress escalation. Remarkably, gender was found to be a main moderating variable, showing different emotional reactions to LLM addiction. Male university students exhibited higher emotional responses to both performance-connected and socially reassuring uses of LLMs, with a stronger association with depression and anxiety. Female university students, on the other hand, showed greater emotional stability, reflecting more resilience and adaptive coping strategies when experiencing AI-driven technologies. These findings expand our understanding of how AI dependence interrelates with human emotional techniques and highlight the need to integrate gender-informed variables in future psychological and educational research on AI adoption.

7. Limitations and Future Research

Similarly to other studies, the current one has some limitations. First, the cross-sectional quantitative approach and the self-reported survey methods can limit the causal inference and social desirability bias. Future research can conduct a longitudinal research design to trace the influence of LLM addiction on mental health over a long period of time. Second, while this paper successfully measured the structural interrelationships among the study constructs, numerical results alone cannot fully explain why users engaged with LLMs, how they emotionally experience these interactions, or what contextual factors influence their behaviors. Future research should therefore incorporate qualitative methods, such as interviews or focus groups or adopt mixed-method approaches to offer richer interpretations. This would allow scholars to better explore the psychological, affective, and situational drivers behind over-dependence on LLMs (LLM addiction), thereby complementing quantitative findings. Third, this study collected data from students enrolled in KSA universities, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings to other contexts. Future research papers can implement a multigroup analysis approach to explore the relationships between LLM addiction and mental health in different samples. Third, this study used gender as a single moderator. Future studies could employ more moderate variables such as study discipline or type of study. Finally, although this study tested LLMs as an AI tool, it did not distinguish between academic load, social reassurance, and emotional status. Future studies may use mixed research methods to explore more qualitative dimensions, such as students’ motivations, LLMS trust, and emotional experience with AI-based systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.A.E. and A.M.S.A.A.; methodology, I.A.E.; software, I.A.E. and A.M.S.A.A.; validation, I.A.E.; formal analysis, I.A.E.; investigation, I.A.E.; resources, I.A.E.; data curation, I.A.E.; writing—original draft preparation, I.A.E. and A.M.S.A.A.; writing—review and editing, I.A.E.; visualization, I.A.E.; supervision, I.A.E.; project administration, I.A.E.; funding acquisition, I.A.E. and A.M.S.A.A., All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia [Project No. KFU254495].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the deanship of the scientific research ethical committee, King Faisal University (KFU-254495, date of approval: 25 April 2025).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Hughes, L.; Baabdullah, A.M.; Rana, N.P. The Impact of Generative Artificial Intelligence on Higher Education: Opportunities and Challenges. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2024, 75, 102789. [Google Scholar]

- Jogezai, N.A.; Koroleva, D.; Ivanov, I. Generative Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education: Challenges, Opportunities and Future Course of Actions to Achieve Sustainable Development Goals. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2025, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuss, D.J.; Griffiths, M.D. Social Networking Sites and Addiction: Ten Lessons Learned. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banjanin, N.; Banjanin, N.; Dimitrijevic, I.; Pantic, I. Relationship between Internet Use and Depression: Focus on Physiological Mood Oscillations, Social Networking and Online Addictive Behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 43, 308–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseem, A.; Hashmi, Z.; Arif, S.; Razzaq, T.; Shahzadi, N. Correlation of Internet Addiction with Academic Performance and General Health in Undergraduate Physiotherapy Students: Internet Addiction with Academic Performance and General Health. Pak. Biomed. J. 2021, 4, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dichev, C.; Dicheva, D. Gamifying Education: What Is Known, What Is Believed and What Remains Uncertain: A Critical Review. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2017, 14, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J.; Koivisto, J.; Sarsa, H. Does Gamification Work?–A Literature Review of Empirical Studies on Gamification. In Proceedings of the 2014 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 6–9 January 2014; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 3025–3034. [Google Scholar]

- Sailer, M.; Hense, J.; Mandl, H.; Klevers, M. Psychological Perspectives on Motivation through Gamification. Interact. Des. Arch. 2013, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroczek, L.O.; May, A.; Hettenkofer, S.; Ruider, A.; Ludwig, B.; Mühlberger, A. The Influence of Persona and Conversational Task on Social Interactions with a LLM-Controlled Embodied Conversational Agent. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2025, 172, 108759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Yin, M.; Zhang, M.; Li, Z.; Chen, Z. Investigating AI Chatbot Dependence: Associations with Internet and Smartphone Dependence, Mental Health Outcomes, and the Moderating Role of Usage Purposes. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, M.H.; Shehzad, K.; Alamro, A.S.; Wadi, M. Internet Use and Addiction among Medical Students in Qassim University, Saudi Arabia. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2019, 19, e142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M.D. The Evolution of the’components Model of Addiction’and the Need for a Confirmatory Approach in Conceptualizing Behavioral Addictions. Düşünen Adam J. Psychiatry Neurol. Sci. 2019, 32, 179–184. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, E.; Blumler, J.G.; Gurevitch, M. Uses and Gratifications Research. Public Opin. Q. 1973, 37, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M. A ‘Components’ Model of Addiction within a Biopsychosocial Framework. J. Subst. Use 2005, 10, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibben, G.O.; Martin, A.; Shore, C.B.; Johnstone, A.; McMellon, C.; Palmer, V.; Pugmire, J.; Riddell, J.; Skivington, K.; Wells, V.; et al. Adolescents’ Interactive Electronic Device Use, Sleep and Mental Health: A Systematic Review of Prospective Studies. J. Sleep Res. 2023, 32, e13899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liu, R.-D.; Ding, Y.; Hong, W.; Ding, Z. Interpersonal Relationships Moderate the Relation between Academic Stress and Mobile Phone Addiction via Depression among Chinese Adolescents: A Three-Wave Longitudinal Study. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 19076–19086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukarromah, L.A.; Hakim, G.R.U. The Influence of Time Management and Social Media Addiction on Academic Procrastination in Undergraduate Students. J. Sains Psikol. 2023, 12, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, R.; McKean, M. College Students’ Academic Stress and Its Relation to Their Anxiety, Time Management, and Leisure Satisfaction. Am. J. Health Stud. 2000, 16, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Xu, Y.; Yang, T.; Li, Z.; Dong, Y.; Chen, L.; Sun, X. The Mediating Roles of Time Management and Learning Strategic Approach in the Relationship Between Smartphone Addiction and Academic Procrastination. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 2639–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Hassan, N.C.; Hassan, S.A.; Ismail, N.; Gu, X.; Dong, J. The Relationship between Internet Addiction and Academic Burnout in Undergraduates: A Chain Mediation Model. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of Resources: A New Attempt at Conceptualizing Stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, N.; Khan, S.F.; Qatoon, S.S.; Siddiqui, M. Zainab Associations between Internet Addiction, Grit, Perceived Stress and Academic Performance in Medical Students. Int. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2024, 12, 4152–4156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, M.; Chemnad, K.; Al-Harahsheh, S.; Abdelmoneium, A.O.; Baghdady, A.; Ali, R. Depression, Stress, and Anxiety versus Internet Addiction in Early and Middle Adolescent Groups: The Mediating Roles of Family and School Environments. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaRose, R.; Lin, C.A.; Eastin, M.S. Unregulated Internet Usage: Addiction, Habit, or Deficient Self-Regulation? Media Psychol. 2003, 5, 225–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmela-Aro, K.; Upadyaya, K.; Hakkarainen, K.; Lonka, K.; Alho, K. The Dark Side of Internet Use: Two Longitudinal Studies of Excessive Internet Use, Depressive Symptoms, School Burnout and Engagement Among Finnish Early and Late Adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2017, 46, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Su, X.; Zhang, X.; Deng, X. Association between Internet Addiction and Insomnia among College Freshmen: The Chain Mediation Effect of Emotion Regulation and Anxiety and the Moderating Role of Gender. BMC Psychiatry 2025, 25, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, J. The Relationship between Social Support and Internet Addiction among Chinese College Freshmen: A Mediated Moderation Model. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1031566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alosaimi, F.D.; Alyahya, H.; Alshahwan, H.; Al Mahyijari, N.; Shaik, S.A. Smartphone Addiction among University Students in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2016, 37, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardefelt-Winther, D. A Conceptual and Methodological Critique of Internet Addiction Research: Towards a Model of Compensatory Internet Use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, S.E. Preference for Online Social Interaction: A Theory of Problematic Internet Use and Psychosocial Well-Being. Commun. Res. 2003, 30, 625–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, D.; Tian, Y.; Xu, B.; Wu, X. Gender Differences in Symptom Structure of Adolescent Problematic Internet Use: A Network Analysis. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2023, 17, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, H.; Elhai, J.D. Are There Gender Differences in Comorbidity Symptoms Networks of Problematic Social Media Use, Anxiety and Depression Symptoms? Evidence from Network Analysis. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2022, 195, 111705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, S.K.; Elshaer, I.A. Organizational Politics and Validity of Layoff Decisions: Mediating Role of Distributive Justice of Performance Appraisal. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2017, 26, 805–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Huang, Z.; Li, H.; Liu, M.; Zhang, W.; Ma, N.; Yang, L.; Gu, F.; Liu, Y.; Jin, S. Is the Excessive Use of Microblogs an Internet Addiction? Developing a Scale for Assessing the Excessive Use of Microblogs in Chinese College Students. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e110960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovibond, P.F.; Lovibond, S.H. The Structure of Negative Emotional States: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 1995, 33, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, J.D.; Crawford, J.R. The Short-form Version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct Validity and Normative Data in a Large Non-clinical Sample. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 44, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.-H.; Chen, C.-Y.; Liao, X.; Chen, X.; Zheng, X.; Tsai, Y.-C.; Lin, C.-Y.; Griffiths, M.D.; Pakpour, A.H. Psychometric Properties of the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21) among Different Chinese Populations: A Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Analysis. Acta Psychol. 2023, 240, 104042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.-H.; Liao, X.-L.; Jiang, X.-Y.; Li, X.-D.; Chen, I.-H.; Lin, C.-Y. Psychometric Evaluation of the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21) among Chinese Primary and Middle School Teachers. BMC Psychol. 2023, 11, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Sarstedt, M. Goodness-of-Fit Indices for Partial Least Squares Path Modeling. Comput. Stat. 2013, 28, 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Homburg, C., Klarmann, M., Vomberg, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 587–632. ISBN 978-3-319-57413-4. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. The Partial Least Squares Approach to Structural Equation Modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Leguina, A. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Int. J. Res. Method. Educ. 2015, 38, 220–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Cheah, J.-H.; Becker, J.-M.; Ringle, C.M. How to Specify, Estimate, and Validate Higher-Order Constructs in PLS-SEM. Australas. Mark. J. 2019, 27, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Müller, H. Evaluating the Fit of Structural Equation Models: Tests of Significance and Descriptive Goodness-of-Fit Measures. Methods Psychol. Res. Online 2003, 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Monecke, A.; Leisch, F. semPLS: Structural Equation Modeling Using Partial Least Squares. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Wang, C.; Chen, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, H. Stress and Internet Addiction: Mediated by Anxiety and Moderated by Self-Control. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2023, 16, 1975–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavurova, B.; Khouri, S.; Ivankova, V.; Rigelsky, M.; Mudarri, T. Internet Addiction, Symptoms of Anxiety, Depressive Symptoms, Stress among Higher Education Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 893845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panisoara, I.O.; Lazar, I.; Panisoara, G.; Chirca, R.; Ursu, A.S. Motivation and Continuance Intention towards Online Instruction among Teachers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mediating Effect of Burnout and Technostress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhai, J.D.; Dvorak, R.D.; Levine, J.C.; Hall, B.J. Problematic Smartphone Use: A Conceptual Overview and Systematic Review of Relations with Anxiety and Depression Psychopathology. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 207, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraut, R.; Patterson, M.; Lundmark, V.; Kiesler, S.; Mukophadhyay, T.; Scherlis, W. Internet Paradox: A Social Technology That Reduces Social Involvement and Psychological Well-Being? Am. Psychol. 1998, 53, 1017–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Campbell, W.K. Associations between Screen Time and Lower Psychological Well-Being among Children and Adolescents: Evidence from a Population-Based Study. Prev. Med. Rep. 2018, 12, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, P.; Wang, B.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ni, C.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Bu, Y. The Applications of Large Language Models in Mental Health: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e69284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiferaw, B.D.; Tang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Mackay, L.E.; Luo, Y.; Yan, N.; Shen, X.; Zhou, T. Impact of Digital Addiction on Youth Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Behav. Addict. 2025, 14, 1129–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adedia, D.; Konlan, K.D.; Tsogbe, D.; Kugbey, N.; Kale, E.R.; Gmayinaam, V.U.; Anaman, J.; Ayanore, M. Digital Addiction and Emotional Exhaustion as Mediators between Problematic Internet Use and Mental Well-Being in University Students. SSRN 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błachnio, A.; Przepiórka, A. Facebook Intrusion, Fear of Missing out, Narcissism, and Life Satisfaction: A Cross-Sectional Study. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 259, 514–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Fernandez, O.; Kuss, D.J.; Griffiths, M.D.; Billieux, J. The Conceptualization and Assessment of Problematic Mobile Phone Use. Encycl. Mob. Phone Behav. 2015, 591–606. [Google Scholar]

- Matud, M.P. Gender Differences in Stress and Coping Styles. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2004, 37, 1401–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derks, D.; Van Duin, D.; Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B. Smartphone Use and Work–Home Interference: The Moderating Role of Social Norms and Employee Work Engagement. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 88, 155–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primack, B.A.; Shensa, A.; Sidani, J.E.; Whaite, E.O.; Lin, L.Y.; Rosen, D.; Colditz, J.B.; Radovic, A.; Miller, E. Social Media Use and Perceived Social Isolation Among Young Adults in the U.S. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 53, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Emotion Regulation and Psychopathology: The Role of Gender. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 8, 161–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozgonjuk, D.; Blinka, L.; Löchner, N.; Faltýnková, A.; Husarova, D.; Montag, C. Differences between Problematic Internet and Smartphone Use and Their Psychological Risk Factors in Boys and Girls: A Network Analysis. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2023, 17, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, R.; Basu, A.; Anto, A.; Foscht, T.; Eisingerich, A.B. Effects of Large Language Model–Based Offerings on the Well-Being of Students: Qualitative Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2024, 8, e64081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).