Abstract

Bounds for positive definite sets such as attractors of dynamic systems are typically characterized by Lyapunov-like functions. These Lyapunov functions and their time derivatives must satisfy certain definiteness conditions, whose verification usually requires considerable experience. If the system and a Lyapunov-like candidate function are polynomial, the definiteness conditions lead to Boolean combinations of polynomial equations and inequalities with quantifiers that can be formally solved using quantifier elimination. Unfortunately, the known algorithms for quantifier elimination require considerable computing power, meaning that many problems cannot be solved within a reasonable amount of time. In this context, it is particularly important to find a suitable mathematical formulation of the problem. This article develops a method that reduces the expected computational effort required for the necessary verification of definiteness conditions. The approach is illustrated using the example of the Chua system with cubic nonlinearity.

1. Introduction

Lyapunov’s direct method enables stability analysis without knowing the explicit solution of a (usually nonlinear) differential equation [1,2]. This method was originally introduced for the stability analysis of equilibrium points, but has been extended to numerous related problems in recent decades. In addition to control theory applications, e.g., with control Lyapunov functions, Lyapunov’s method can also be used to estimate basins of attraction, trapping regions and attractors [3,4,5].

If a nonlinear dynamic system has a chaotic attractor, then the geometry of this attractor usually cannot be described exactly in a straightforward manner. For many questions, such as estimating the attractor’s dimension [6,7], it is necessary or helpful to narrow down this attractor in the state space. Such a containment can be realized via positive invariant sets, which are described by sublevel sets of a Lyapunov-like function [3,4,5]. In this case, one starts from a positive definite Lyapunov-like candidate function and must show that its time derivative along the dynamic system in question is negative outside of the sublevel set. There are two difficulties here: firstly, choosing the correct candidate function, and secondly, showing that its total time derivative is negative for large values. In particular, the second step usually requires extensive experience and intuition [7].

The positive definiteness of the candidate function can usually be ensured or easily verified. The property of the time derivative of the candidate function being negative in certain regions can be described by combining inequalities with quantifiers. For polynomial systems with a polynomial Lyapunov candidate function, these inequalities are also polynomial, and the resulting formulas with quantifiers can be solved with a technique known as quantifier elimination (QE) [8,9,10,11].

The calculation of bounds for positively invariant sets using QE has already been successfully applied to the Lorenz system, the Lorenz–Haken system, the Lorenz family, and a system going back to Rössler [12,13,14]. This approach was successful because the Lyapunov candidate functions used were fairly simple. Minor generalizations of the Lyapunov candidate functions would quickly result in a situation where the required calculations could no longer be performed within a reasonable amount of time. For further applications of the proposed approach, it is therefore important to reduce the computational effort. In [15], a method was developed to simplify the underlying quantifier elimination problem when searching for suitable Lyapunov functions. This method was reduced to the two-dimensional case and focused on stability analysis of equilibrium points. This paper extends the approach to systems of arbitrary finite dimension. In addition to analyzing the stability of equilibrium points, it is also possible to determine bounds for positively invariant sets.

The paper is structured as follows. In Section 2 we provide mathematical preliminaries. The Lorenz system is discussed in Section 3 as a motivational example, where the choice of the Lyapunov-like candidate function has an impact on the computability. The main result is presented in Section 4. In Section 5 we illustrate the approach on Chua’s system with cubic nonlinearity. The results are discussed in Section 6.

2. Mathematical Preliminaries

2.1. Nonlinear Systems and Positive Invariant Sets

Consider a nonlinear autonomous system

of ordinary differential equations with the vector field with the state vector x. For the computational methods derived in the paper we assume that the vector field f is polynomial, i.e., its components are multivariate polynomials in the variables with rational coefficients (the restriction to rational numbers is for their simple exact representation in computer algebra systems; in principle, any real field with exact representation could be used for the coefficients, e.g., real algebraic numbers). From this it follows that f is smooth and locally Lipschitz. Consequently, for every initial value there exists an at least locally defined unique solution . The existence of a global solution will become apparent later, when the bounds of the solution have been shown.

A subset is called positive invariant with respect to (1) if every solution of (1) starting in stays in for all future times, i.e.,

Such sets are also called trapping regions [16]. Positive invariant sets can be approximated using Lyapunov-like candidate functions and a constant by

where the subset is bounded by the level set . If all solutions of (1) starting with initial values with tend to , the set contains an attractor. In this case, the solution of (1) is bounded by

Without explicit knowledge of the solution of (1), the bound describing the subset (3) can be computed by

using Lyapunov techniques, where the derivative is the directional derivative of V along the dynamics of system (1) see [17], Remark 10.1.2. The idea behind this condition is that for any trajectory starting outside , decreases, causing the trajectory at some point to enter the set and remain there. This derivative can be written as a Lie derivative of the scalar field V along the vector field f, i.e.,

see [2]. Alternatively, the bound can be calculated using the differential inequality

as suggested in [18]. This condition ensures for , so that (5) is satisfied. The result is a half-open interval for , from which the minimum is selected as the best bound.

Example 1.

Quadratic forms

with a positive definite symmetric matrix are often used as a candidate function for V. When the matrix P contains free parameters, the definiteness can be ensured. For example, by Sylvester’s criterion or a Cholesky decomposition [19,20,21]. A construction method for more general candidate functions is based on sum of squares (SOS) decomposition [22], but leads to a purely numerical procedure. However, it is much more difficult to solve (5) or (7) for the bound γ. In particular, Formulas (5) or (7) are only solvable if for large .

2.2. Quantifier Elimination

The Formulas (5) and (7) specify the bound for the positive invariant set (3). These formulas contain quantifiers, namely the universal quantifier ∀ and the existential quantifier ∃. These formulas can be solved by quantifier elimination.

Let us briefly introduce some notations and concepts [9]. The starting point for our considerations are polynomial equations or inequalities over the reals of the form

called atomic formulas in the variables . A Boolean combination of finitely many atomic formulas using logical operators such as is called a quantifier-free formula. A quantifier-free formula describes a semi-algebraic set. Let be a quantifier-free formula in the variables X and the additional variables . A prenex formula has the form

with quantifiers . The variables Y are called quantified variables. The remaining variables not bound by a quantifier are called free variables. The Tarski–Seidenberg theorem [8,9,23] states that for every prenex formula there exists an equivalent quantifier-free formula solely depending on the free variables X. This transformation from a prenex formula to an equivalent quantifier-free formula is called quantifier elimination (QE).

Over the past half-century, a number of different methods for performing quantifier elimination have been developed. The best-known methods are cylindrical algebraic decomposition (CAD) [24,25], virtual substitution (VS) [26,27] and real root classification [28]. In general, all these methods are very computationally intensive [29]. More precisely, CAD is double exponential in the number of all occurring variables [30]. Later, it was shown that the computational effort for linear formulas is double exponential only in the number of quantifier alternations [26]. These considerations led to the development of the VS method, which has been successfully implemented for polynomials up to degree three [31]. In recent years, research has also been conducted into concepts for applying VS to polynomials of higher degrees [27,32,33]. For application to more complex problems with multiple quantifiers, one eliminates (depending on the polynomial degree) the first quantifiers and thus also variables with VS, and switches to CAD if the degree permitted for VS is exceeded. In order to apply QE to practical problems, it is very important to find an appropriate mathematical formulation with as few variables and quantifiers as possible and a low polynomial degree.

Several software packages are available for solving non-trivial QE problems. The open source package QEPCAD B [34] uses CAD and is available in the repositories of common Linux distributions. The package REDLOG [35] is based on the computer algebra system REDUCE and contains implementations of CAD as well as VS. The computed quantifier-free expressions can be simplified with SLFQ [36]. Commercial computer algebra systems such as Maple or Mathematica also have procedures and libraries for carrying out QE, e.g., [37,38].

Example 2.

Consider the real biquadratic polynomial

with the parameters p and q. The question of the existence of at least one real root can be described by the following prenex formula

where x is a quantified variable and are free variables. Applying QE to (12) leads to the equivalent quantifier-free formula

Similarly, one can ask under what conditions on the parameters the polynomial only takes positive function values:

Carrying out QE to (14) leads to the equivalent quantifier-free formula

3. Motivational Example

The Lorenz system is one of the most popular nonlinear systems exhibiting chaotic dynamics. The system is governed by the differential equations

with positive parameters . (Lorenz’s original work [39], as well as numerous studies based on it, assume positive parameter values. From 2010 onwards, there are publications that also take negative parameter values into account [40,41]. When using QE to calculate bounds, negative parameter values can generally be allowed. For the Lorenz system, however, most sign constellations of the parameters lead to divergent and thus unstable solutions, so that no attractor exists in these cases [40]. If the signs of the parameters are not restricted and the Lyapunov-like candidate function (17) is used, then QE leads to the condition .) To calculate bounds for the Lorenz attractor, numerous Lyapunov candidate functions were investigated [3,18,42,43]. Two well-known candidate functions were given in [4,5], Appendix C:

The level sets of these functions describe a sphere and an ellipsoid, respectively, both shifted with respect to the -axis. Another common feature is that the coefficients of the monomials and are the same within each equation. If we ignore this commonality for the time being, we can consider the functions (17) and (18) as special cases of the Lyapunov candidate function

with the coefficients and , cf. [12]. The time derivative of along (16) is given by

The free parameters should be chosen so that is possible for large . The cubic term is the one with the highest degree. However, the monomial has an odd degree. This monomial can be both positive and negative for large . However, if we choose , the derivative (20) can become negative for large due to the quadratic terms. This explains the above-mentioned commonality in the candidate functions (17) and (18).

If we now ignore the displacement along the -axis, then (19) represents a special case of a quadratic form (8), where the matrix P is a diagonal matrix. The question arises as to whether a better bound on the invariant set is possible with a dense matrix

The matrix P is positive definite if and only if

according to Sylvester’s criterion [19,20].

The Lie derivative of (8) with the generic matrix (21) is a polynomial in the variables , with total degree 3. The terms with the highest degree are

Since the highest degree is an odd number, the associated monomials

are indefinite with regard to their sign for large . If these monomials occur in , the condition for will not be fulfilled. Therefore, the entries of the matrix (21) have to be chosen such that the terms (23) vanish. This is achieved by choosing the coefficients as follows:

resulting in the diagonal matrix

with .

Remark 1.

The choice (25) corresponds exactly to the coefficients in (19). This means that the dense matrix (21) does not provide any advantage for evaluating the global attraction of (3), i.e., for the behavior of the system for large . This does not rule out the possibility that a dense matrix P could also have advantages for the more precise determination of bounds for invariant sets for smaller .

Remark 2.

For the candidate Lyapunov functions (17), (18) and (19), as well as (8) with (21), bounds γ can theoretically be determined exactly (with reference to the respective candidate function) in finite time by applying QE to the formulas (5) and (7). For the candidate functions (17) and (18), symbolic expressions for the bound γ as a function of the symbolic parameters can be obtained with REDLOG on a standard PC in a few seconds, whereby case distinctions occur for different parameter ranges [12]. When using formula (5), there are four free and three quantified variables, respectively. If we use (7), there is an additional quantified variable and one quantifier alternation. When using the candidate function (19), the situation is different, because four further variables are added. Moreover, the polynomial degree of the time derivative increases from two to three, see (20). Neither with symbolic nor with numerically specified system parameters did QE deliver a solution, even after several days of computing time. Only when numerical values were specified for the parameters , thereby creating a decision problem, did QE deliver a result. This also meant that it was not possible to directly verify whether the more general approach (8) with (21) offers any advantages.

Problem 1.

Remark 2 implies that the candidate function must be selected in such a way that, on the one hand, there are enough degrees of freedom to meet the definiteness requirements, but on the other hand, there are not too many free parameters to be able to check these definiteness conditions with QE in reasonable time. When formulating the mathematical problem as a prenex formula, the number of variables and the number of quantifier alternations should therefore be as low as possible, and the polynomial degree should be as small, too.

4. Results

Section 4.1 deals with the use of QE to validate the local definiteness of functions, as used in the stability analysis of steady states. For this, Section 4.2 describes a necessary condition that requires significantly less computing power. In this process, the terms of lowest degree of a polynomial are evaluated consecutively. If one proceeds in a similar manner in reverse, starting with terms of the highest degree and working downwards, one obtains conditions for Lyapunov candidate functions that are suitable for estimating positive invariant sets, see Section 4.3.

4.1. Description of Local Positive Definiteness by Prenex Formulas

To formulate the stability conditions, we need the concept of positive definiteness of a Lyapunov candidate function V and negative definiteness or semi-definiteness of its time derivative . The algorithms refer to both V and , so we will use the designation in the following. Since we are dealing with polynomials in this paper, all functions are globally defined and continuously differentiable.

Definition 1.

A function is called locally positive definite or positive definite on a neighborhood around the origin if

If (26) holds on , the function is called globally positive definite.

In the same manner, we define positive semi-definite with , negative definite with and negative semi-definite with for all . Clearly, a function W is negative definite (semi-definite) if is positive definite (semi-definite). A function W is called indefinite if the function is neither positive semi-definite nor negative semi-definite, i.e., for every neighborhood there exists two points with and .

We assume that the function W is a multivariate polynomial without a constant term, which ensures . If we characterize the neighborhood with using the maximum norm (one could use any norm to define the neighborhood, but others than the one or infinity norm lead to higher-degree polynomials), the test for a given candidate function W regarding local positive definiteness on can be formulated with the following prenex formula:

If W is fully specified without free parameters, the prenex Formula (27) constitutes a decision problem, where QE leads either to true or false. If W contains free parameters (e.g., (8) with a symbolic matrix (21)), QE would result in a quantifier-free formula with conditions on the free parameters. In principle, after applying QE, the prenex Formula (27) would provide a conclusive test for positive definiteness or a characterization of the free parameter values required for it. However, it is not clear whether, for a given function, QE can be performed within a reasonable time due to the computational effort involved.

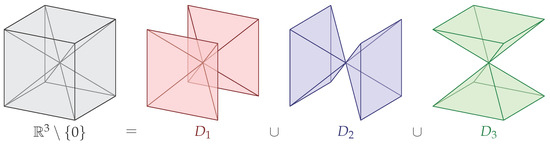

Consider a region of the state space defined by

In this region, the substitution

with defines the mapping

and describes a change of coordinates between and . The Lyapunov candidate function W can be written on in the new coordinates as follows:

The regions describe a decomposition of the state space , as depicted in Figure 1 for .

Figure 1.

Decomposition of the state space.

Remark 3.

This decomposition is not disjoint so that the boundaries are contained in multiple domains. These points on the boundary occur in the formulas for different index i. The decomposition is thus not disjoint.

Condition (27) can be tested for each region separately using the new coordinates by

for . Note that the prenex Formula (31) still has the same number of quantified variables as (27). The restriction to one sector could in some cases lead to a simplification of QE, but on the other hand, the degree of some terms will increase due to the multiplication of and x in (29), which can lead to a higher computational effort.

Remark 4.

If the auxiliary variables are fixed (or assumed to have already been eliminated), then the function is a univariate polynomial in the variable z. The definiteness of a single term of a univariate polynomial can be easily determined. For an even number k, the term is positive or negative definite if and only if or , respectively. For an odd number k, the term with is indefinite. Transforming a multivariate polynomial into a univariate polynomial therefore simplifies the definiteness test.

4.2. Necessary Condition

If the order of consecutive quantified variables of the same quantifier is swapped, the logical statement in question does not change. Changing the order of variables with different quantifiers, on the other hand, changes the statement. Swapping the existential quantifier with the universal quantifier results in the following implication:

Now we apply this implication to (31) and obtain the following necessary condition

with the prenex formula H. The function can be written as a polynomial

in the variable z with coefficients from the ring of real polynomials in . Without loss of generality we assume that the constant term vanishes, i.e., . For fixed values , the prenex formula H simply states the local positive definiteness of the function , i.e., has a local minimum at . For univariate polynomials, this means that the term of lowest degree is even with a positive coefficient. From (33), the formula

is obtained. Formula (35) is therefore a necessary condition for to be locally positive definite. The necessary conditions for to be locally negative definite as well as locally positive or negative semi-definite can be formulated similarly.

Remark 5.

For practical implementation, it would be useful to check the various conditions for the coefficients step by step:

If the first condition is fulfilled, then the function is locally positive definite and the algorithm is terminated. Otherwise, the subsequent conditions must be checked.

Example 3.

Consider the function given by

Clearly, W is not positive definite, as its zero-set contains the curve through the origin. Thus, (27) is . If we write this function in the domain with , we obtain

The prenex formula, (31) is for , too. However, if we switch the quantifiers and consider as a function of z only with parameter λ, (33) is .

Remark 6.

Although relation (35) is only necessary for (31), it can be used to restrict the degrees of freedom in the choice of parameters for the Lyapunov candidate function and thus possibly eliminate superfluous terms. From a computational point of view, the formulation (35) has several advantages compared to (26). On the one hand, the number of quantified variables has been reduced by two. In addition, there is no change between different quantifier types, which is particularly advantageous for performing QE with VS [27]. On the other hand, formulation (35) is based only on polynomials in λ, so that omitting z results in terms of lower degree and thus allows for faster computation.

4.3. Description of Definiteness at Large Values

To check the stability of an equilibrium (typically at the origin), local definiteness conditions must be checked in the neighborhood of this equilibrium. These conditions apply to small values of . For determining bounds for positively invariant sets, however, the behavior for large is of interest. The following form of definiteness is essentially complementary to local definiteness [44].

Definition 2.

A function is called positive definite at infinity or positive definite at large values if there exists a number with

A function is called (positive) coercive [45] if for .

In a similar way, the terms positive semi-definite, negative definite and negative semi-definite at infinity can be introduced. Clearly, a polynomial coercive function is positive definite at infinity. The use of a coercive function is recommended in itself, since the sets (3) defined by the preimages of such a function are compact.

Example 4.

The function with is positive definite at infinity, but not coercive.

A minor modification of (27) leads to a test of a given candidate function W regarding positive definiteness at infinity with the following prenex formula:

As in Section 4.1, the Lyapunov-like candidate function W can be rewritten on a region according to (30). Then, condition (37) leads to

for . Applying the implication (32) yields the necessary condition

with the prenex formula J. The prenex formula J simply states the positive definiteness of the function at infinity. As before, we consider as an univariate polynomial (34) of degree M in the variable z. For an even degree M, the prenex formula

is a necessary condition for to be positive definite at infinity. For an odd degree M, the prenex formula

is a necessary condition for to be positive definite at infinity.

Example 5.

Consider the function given by

from Example 3 again. As the zero-set contains the unbounded curve , W is not positive definite at infinity as well. Thus, (37) is . We write this function in the domain with :

The prenex Formula (38) is for , too. However, if we switch the quantifiers and consider as a function of z only with parameter λ, (39) is . This is because restricted to any line through the origin is positive definite at infinity.

Remark 7.

As stated in Remark 5, it may be useful for practical implementation to check the conditions on the coefficients step by step. If M is even, the conditions are obtained from (40) as follows:

If the first condition is met, the algorithm can be terminated. Otherwise, the subsequent conditions would need to be examined.

5. Chua’s Circuit with Cubic Nonlinearity

In Section 5.1, we derive a model for Chua’s circuit, in which the piecewise-linear nonlinearity is replaced by a cubic polynomial. The conditions for the definiteness of functions at infinity derived in Section 4.3 are applied in Section 5.2 to derive conditions on the structure of a Lyapunov-like candidate function for the Chua system. Admissible ranges for the parameter values of the Lyapunov-like candidate function are determined in Section 5.3. The computation of bounds for the containment of positively invariant sets is performed in Section 5.4.

5.1. System Model

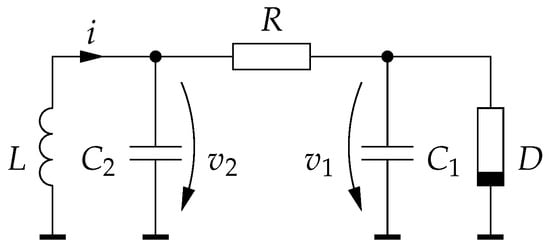

Chua’s circuit is an electronic circuit that can generate a chaotic attractor known as double scroll when appropriate parameter values are used [46,47]. The circuit diagram is shown in Figure 2. Kirchhoff’s circuit laws yield the following differential equations:

with and the conductance and . In [46,48], the authors used the normalized parameter values , , and .

Figure 2.

Circuit diagram of Chua’s circuit.

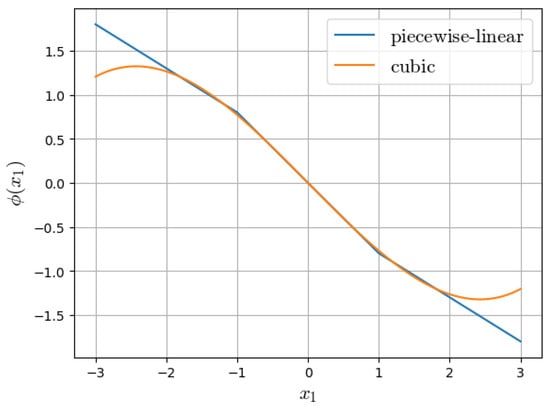

The nonlinearity of the circuit is a voltage controlled current source known as Chua’s diode and labeled D in the circuit diagram. Typically, the nonlinearity is a three-segment piecewise-linear function

In [48], the parameter values and were used. The replacement of the non-smooth function (43) by cubic polynomial

was suggested in [49]. In [50], p. 143, the parameters a and b were chosen such that the functions (43) and (44) assume the smallest distance in the sense of quadratically integrable functions on the interval :

Figure 3 shows both characteristics, which are in very good agreement over the interval , but diverge outside this range.

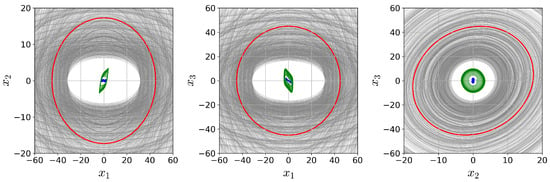

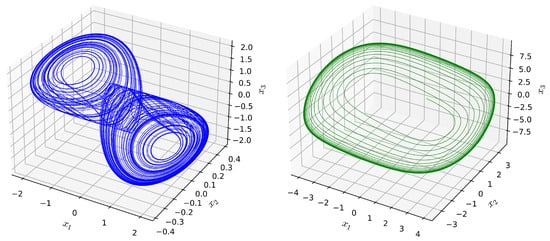

To illustrate the system’s behavior we carried out a numerical simulation with SageMath [51] using the parameters given above. Using the initial conditions , the transients seem to converge to the chaotic attractor, as shown in Figure 4 (left). With the initial conditions , the solution, however, converges towards a limit cycle. This transient response is shown in Figure 4 (right). The axes scalings in Figure 4 show that the limit cycle lies further out in the state space than the chaotic attractor.

Figure 4.

Numerical simulation results, chaotic attractor (left), settling into a limit cycle (right).

5.2. Structure of the Quadratic Lyapunov-like Candidate Function

Consider the Chua system (42) with the cubic nonlinearity (44) and the additional constraints

on the parameters. To derive bounds on a positive invariant set we use a Lyapunov-like candidate function V as a quadratic form (8) with the matrix (21). The function V is positive definite if and only if (22) holds. The positive definiteness of V can thus be easily ensured. The question of whether or how the entries of the matrix P can or should be chosen so that the time derivative becomes negative definite or at least semi-definite for large values is much more difficult.

The time derivative of the Lyapunov-like candidate function V has the form

where the numerator is a multivariate polynomial W in the variables and the parameters. The denominator is a positive constant. The definiteness of can therefore be determined by the definiteness of W. The expression for W is very extensive and is therefore not given here.

Now, we will decompose the state space into three regions , as already depicted in Figure 1. Since the vector field f is a polynomial of degree 3 and V is quadratic in the variables , the Lie derivative (6) is a polynomial of degree 4. Therefore, the functions defined by (30) on the three regions are polynomials of the degree 4 in the variable z with the form

with and .

For large , only the terms of degree 4 are relevant. Therefore, the terms of degree 4 should not be positive for all . This corresponds to the property of positive semi-definiteness of at infinity. According to Remark 7, one would therefore check the leading coefficient with regard to its sign first. Together with (46), we therefore obtain the prenex formulas

for similar to (40). The QE was carried out with REDLOG using VS for its usually superior performance, with fallback to CAD if VS is not possible. The resulting quantifier-free expressions were combined using conjunction (AND) and subsequently simplified with SLFQ, leading to

Note that if we replace the condition in (49) by the strict inequality , QE would lead to the result .

5.3. Parametrization of the Quadratic Lyapunov-like Candidate Function

Consider the matrix P with the special structure according to (51). The matrix P is positive definite if and only if

With the simplification resulting from the structure (51), the numerator polynomial of (47) can be written as

This polynomial function has no terms of degree 3. For the function W to be negative definite at infinity, the monomials , , must have negative coefficients:

These coefficients are negative if

The second order mixed terms could also have an impact on the definiteness:

The calculation of a bound for the delimitation of positively invariant sets would be simplified if these terms could be set to zero. Because of , according to (52) the coefficient in (57) cannot become zero. Because after (56), the coefficient in (58) cannot become zero either. The coefficient in (59) becomes zero if and only if

which leads to a further simplification of W:

For we used the parameter values given in Section 5.1. In addition, we normalized . The conditions (52), (56), and (60) lead to

If we add existence quantifiers for and to the expression, then after QE we obtain the condition . For further calculation, we choose . Eliminating yields the condition

on . This means that lies in the (relatively small) interval

For the parameter, we choose the arithmetic mean of the two limits:

With specified, we obtain the condition

on the remaining parameter, resulting in

In summary, the following parameters are used for the matrix (51):

5.4. Computation of the Bounds

After specifying the Lyapunov-like candidate function V according to (8) with (51) and (62), an attempt can be made to calculate the bound for a positive invariant set (3). Similarly to (7), we use the prenex formula

where only the denominator W of was used to obtain a polynomial formulation (see (47)). Applying QE to (63) should provide conditions for in the form of a quantifier-free formula. Unfortunately, even after several days of computing time, the attempt with QE was unable to deliver a result, so the calculation was aborted.

However, if we replace the symbolic variable with a specific positive number, the prenex Formula (63) becomes a decision problem with the possible results true or false, which could be solved on a standard PC in a few hundred milliseconds. In combination with a bisection method, the bound can therefore be calculated with arbitrary precision. Carrying out QE on (63) with yields true, whereas yields false. The levels sets of this bound are ellipses shown in Figure 5 in red. In addition, the transients already depicted in Figure 4 are also shown, using blue and green colors for the chaotic attractor and the stable limit cycle, respectively. When specifying the elements of the matrix P, arbitrary decisions were also made to determine and . Therefore, other parameter values for the admissible ranges were generated using a random number generator, and we attempted to find a bound using the prenex Formula (63). The levels resulting from these bounds are shown in gray in Figure 5.

6. Discussion

Although the quantifier elimination is a powerful tool to compute definite bounds for attractors, its high computational effort restricts the applicability to rather simple systems and Lyapunov candidates. A slight simplification or reformulation of the problem can reduce the computation time significantly. Therefore, the construction of appropriate quantified formulas is an important topic. In this contribution we have shown a state transformation that is particularly useful for the proof of bounds on positive invariant sets using Lyapunov functions.

By changing the order of the quantifiers, necessary conditions for the ansatz parameters can be found much more easily, that is, with less computational effort. Every such reduction for the parameter space in return simplifies the original problem. That the quantifier elimination problem must be solved for each region , separately is of minor importance.

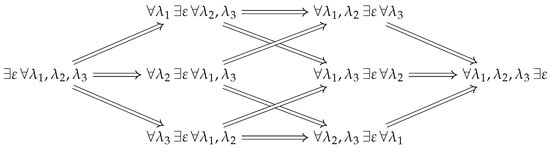

From (31) to (33) or from (38) to (39), the existential quantifier for was swapped several times with the universal quantifiers for . There are a lot of intermediate steps, precisely, one for each partition of the set into two, of gradually changing difficulty that could be considered: Let be disjoint sets such that

Then, according to (32),

Applying this implication to (31) (or (38)) reduces to the problem of positive definiteness (at infinity) in dimension .

All these partitions and implications are shown in Figure 6 for . For the example in Section 5 we have only used the quantified formulas, with quantifiers shown on the left corresponding to (38) and on the right corresponding to (39). In general, one could obtain additional restrictions on the parameter space for the Lyapunov candidate function by traversing the graph from right to left.

Figure 6.

Swapping the order of quantifiers and the implications of the resulting statements. Shown are all combinations for three universal quantifiers.

It should be noted that there are, in general, still a lot of Lyapunov functions that are positive definite (at infinity) with a negative definite (at infinity) derivative along the system dynamics for a particular parametric ansatz. This could also be observed for the example in Section 5. Each of these Lyapunov-like functions yields a positive invariant set, where one candidate function may lead to a better bound than the other. In principle, one could compute the intersection of all these bounds, which is, however, an even more sophisticated semi-algebraic problem.

The calculation of bounds for positive invariant sets has so far mostly been performed manually and involves considerable effort, e.g., see [6,7]. Although several example systems with chaotic attractors are polynomial [52,53,54], the use of QE has been severely limited to date due to the exceptionally high computational effort involved. For the two example systems discussed in the article, the Lorenz system and the cubic Chua system, Formulas (5) and (7) cannot be converted into a quantifier-free formula, even with several days of computing time using a quadratic Lyapunov candidate function with a dense matrix P. The method presented allows for conditions to be generated for the Lyapunov candidate function, enabling certain decisions to be made regarding the structure of the function. This makes it possible to exclude certain terms that are not helpful for the required definiteness. By eliminating redundant terms, one is then led to a calculable reduced problem. Future work could investigate the potential of using the described method to locate hidden attractors [55,56].

In control engineering, there are approaches for the step-by-step construction of Lyapunov functions [57]. A typical example is the recursive design by backstepping or a cascade design. Decomposing the given system into smaller subsystems could be one way of applying the developed method for calculating barriers to higher-dimensional systems.

In addition to the exact or symbolic calculation of barriers, there are also numerical methods [58] and probabilistic approaches [59]. In [60], control Lyapunov functions are approximated by neural networks. This method can undoubtedly also be adapted to Lyapunov functions for calculating bounds for positively invariant sets. This raises the question of the extent to which such numerical methods can be combined with the formal approaches described here.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.R. and D.G.; methodology, D.G.; software, K.R.; validation, K.R.; formal analysis, K.R. and D.G.; writing—original draft preparation, K.R.; writing—review and editing, D.G.; visualization, K.R. and D.G.; project administration, K.R.; funding acquisition, K.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation)—417698841.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The source files will be available on Github [61] under the GNU General Public License v3.0.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| QE | quantifier elimination |

| CAD | cylindrical algebraic decomposition |

| VS | virtual substitution |

| SOS | sum of squares |

References

- Slotine, J.J.E.; Li, W. Applied Nonlinear Control; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, H.K. Nonlinear Control; Pearson: Essex, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Leonov, G.A.; Bunin, A.I.; Koksch, N. Attraktorlokalisierung des Lorenz-Systems. ZAMM-Appl. Math. Mech. 1987, 67, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparrow, C. The Lorenz Equations: Birfucations, Chaos, and Strange Atractors; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; an Lu, J.; Wu, X.; Chen, G. Estimating the bounds for the Lorenz family of chaotic systems. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2005, 23, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitmann, V.; Leonov, G.A. Attraktoreingrenzung für nichtlineare Systeme. In Teubner-Texte zur Mathematik; BSB Teubner: Leipzig, Germany, 1987; Volume 97. [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsov, N.; Reitmann, V. Attractor Dimension Estimates for Dynamical Systems: Theory and Computation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tarski, A. A Decision Method for Elementary Algebra and Geometry; Project rand; Rand Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Caviness, B.F.; Johnson, J.R. (Eds.) Quantifier Elimination and Cylindical Algebraic Decomposition; Springer: Wien, Austria, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- She, Z.; Xia, B.; Xiao, R.; Zheng, Z. A semi-algebraic approach for asymptotic stability analysis. Nonlinear Anal. Hybrid Syst. 2009, 3, 588–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, J.; Bajcinca, N. Computation of Feasible Parametric Regions for Common Quadratic Lyapunov Functions. In Proceedings of the European Control Conference (ECC), Limassol, Cyprus, 12–15 June 2018; pp. 807–812. [Google Scholar]

- Röbenack, K.; Voßwinkel, R.; Richter, H. Automatic Generation of Bounds for Polynomial Systems with Application to the Lorenz System. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2018, 113C, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röbenack, K.; Voßwinkel, R.; Richter, H. Calculating Positive Invariant Sets: A Quantifier Elimination Approach. J. Comput. Nonlinear Dyn. 2019, 14, 074502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röbenack, K. Formal Calculation of Positive Invariant Sets for the Lorenz Family Combining Lyapunov Approaches and Quantifier Elimination. Proc. Appl. Math. Mech. 2021, 20, e202000161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natkowski, L.; Gerbet, D.; Röbenack, K. On the Systematic Construction of Lyapunov Functions for Polynomial Systems. Proc. Appl. Math. Mech. 2023, 23, e202200197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogromsky, A.Y.; Santoboni, G.; Nijmeijer, H. An ultimate bound on the trajectories of the Lorenz system and its applications. Nonlinearity 2003, 16, 1597–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isidori, A. Nonlinear Control Systems II; Springer: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Krishchenko, A.P. Localization of invariant compact sets of dynamical systems. Differ. Equ. 2005, 41, 1669–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, G.T. Positive definite matrices and Sylvester’s criterion. Am. Math. Mon. 1991, 98, 44–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, M.; Minc, H. A Survey of Matrix Theory and Matrix Inequalities; Dover: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Tibken, B.; Dilaver, K.F. Computation of subsets of the domain of attraction for polynomial systems. In Proceedings of the 41st IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 10–13 December 2002; Volume 3, pp. 2651–2656. [Google Scholar]

- Ichihara, H. Sum of Squares Based Input-to-State Stability Analysis of Polynomial Nonlinear Systems. SICE J. Control. Meas. Syst. Integr. 2012, 5, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidenberg, A. A New Decision Method for Elementary Algebra. Ann. Math. 1954, 60, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, G.E. Quantifier elimination for real closed fields by cylindrical algebraic decompostion. In Proceedings of the Automata Theory and Formal Languages 2nd GI Conference Kaiserslautern, Kaiserslautern, Germany, 20–23 May 1975; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1975; pp. 134–183. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, G.E.; Hong, H. Partial Cylindrical Algebraic Decomposition for Quantifier Elimination. J. Symb. Comput. 1991, 12, 299–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weispfenning, V. The complexity of linear problems in fields. J. Symb. Comput. 1988, 5, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, T. Thirty Years of Virtual Substitution: Foundations, Techniques, Applications. In Proceedings of the 2018 ACM on International Symposium on Symbolic and Algebraic Computation; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Vega, L.; Lombardi, H.; Recio, T.; Roy, M.F. Sturm-Habicht Sequence. In Proceedings of the ACM-SIGSAM 1989 International Symposium on Symbolic and Algebraic Computation, Portland, OR, USA, 17–19 July 1989; pp. 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, J.H.; Heintz, J. Real quantifier elimination is doubly exponential. J. Symb. Comput. 1988, 5, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.W.; Davenport, J.H. The complexity of quantifier elimination and cylindrical algebraic decomposition. In Proceedings of the 2007 International Symposium on Symbolic and Algebraic Computation, Waterloo, ON, Canada, 28 July–1 August 2007; pp. 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weispfenning, V. Quantifier Elimination for Real Algebra – the Cubic Case. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Symbolic and Algebraic Computation (ISSAC), Oxford, UK, 20–22 July 1994; pp. 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Košta, M.; Sturm, T. A Generalized Framework for Virtual Substitution. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1501.05826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Košta, M. New Concepts for Real Quantifier Elimination by Virtual Substitution. Ph.D. Thesis, Universität des Saarlandes, Fakultät für Mathematik und Informatik, Saarbrücken, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.W. QEPCAD B: A program for computing with semi-algebraic sets using CADs. ACM SIGSAM Bull. 2003, 37, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolzmann, A.; Sturm, T. Redlog: Computer algebra meets computer logic. ACM SIGSAM Bull. 1997, 31, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.W.; Gross, C. Efficient preprocessing methods for quantifier elimination. In Proceedings of the CASC. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; Volume 4194, pp. 89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Iwane, H.; Yanami, H.; Anai, H. SyNRAC: A Toolbox for Solving Real Algebraic Constraints. In Proceedings of the Mathematical Software—ICMS 2014, Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Hong, H., Yap, C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; Volume 8592, pp. 518–522. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Maza, M.M. Quantifier elimination by cylindrical algebraic decomposition based on regular chains. J. Symb. Comput. 2016, 75, 74–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, E.N. Deterministic non-periodic flow. J. Atmos. Sci. 1963, 20, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.M.; Li, S.Y. Yang and Yin parameters in the Lorenz system. Nonlinear Dyn. 2010, 62, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algaba, A.; Domínguez-Moreno, M.; Merino, M.; Rodríguez-Luis, A.J. Takens–Bogdanov bifurcations of equilibria and periodic orbits in the Lorenz system. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2016, 30, 328–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishchenko, A.P.; Starkov, K.E. Localization of compact invariant sets of the Lorenz system. Phys. Lett. A 2006, 353, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; an Lu, J.; Wu, X.; Chen, G. Estimating the ultimate bound and positively invariant set for the Lorenz system and a unified chaotic system. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2006, 323, 844–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaffrey, D. Geometric existence theory for the control-affine H∞ problem. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2006, 324, 682–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Kandil, H.; Freiling, G.; Ionescu, V.; Jank, G. Symmetric differential Riccati equations: An operator based approach. In Matrix Riccati Equations in Control and Systems Theory; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 411–466. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, T. A chaotic attractor from Chua’s circuit. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. 1984, 31, 1055–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, L.O. The genesis of Chua’s circuit. Arch. Elektron. Übertragungstechnik (AEÜ) 1992, 46, 250–257. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, M.P. Robust OP AMP realization of Chua’s circuit. Frequenz 1992, 3–4, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, G.Q. Implementation of Chua’s Circuit with a Cubic Nonlinearity. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I 1994, 41, 934–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röbenack, K. Regler- und Beobachterentwurf für nichtlineare Systeme mit Hilfe des Automatischen Differenzierens; Shaker Verlag: Aachen, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- The Sage Developers. SageMath, the Sage Mathematics Software System, Version 10.2. 2024. Available online: https://www.sagemath.org.

- Rössler, O.E. Continuous Chaos — Four Prototyp Equations. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1979, 316, 376–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprott, J.C. Some simple chaotic flows. Phys. Rev. E 1994, 50, R647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprott, J.C. Simple chaotic systems and circuits. Am. J. Phys. 2000, 68, 758–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonov, G.A.; Kuznetsov, N.V. Hidden attractors in dynamical systems. From hidden oscillations in Hilbert–Kolmogorov, Aizerman, and Kalman problems to hidden chaotic attractor in Chua circuits. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2013, 23, 1330002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, N.; Leonov, G. Hidden attractors in dynamical systems: Systems with no equilibria, multistability and coexisting attractors. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2014, 47, 5445–5454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepulchre, R.; Janković, M.; Kokotović, P. Constructive Nonlinear Control; Springer: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Yegorov, I.; Dower, P.M.; Grüne, L. Synthesis of control Lyapunov functions and stabilizing feedback strategies using exit-time optimal control Part II: Numerical approach. Optim. Control Appl. Methods 2021, 42, 1410–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froyland, G.; Padberg, K. Almost-invariant sets and invariant manifolds – Connecting probabilistic and geometric descriptions of coherent structures in flows. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2009, 238, 1507–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grüne, L.; Sperl, M. Examples for separable control Lyapunov functions and their neural network approximation. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2023, 56, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Computation of Bounds for Polynomial Dynamic Systems, Source Files. Available online: https://github.com/TUD-RST/computation-bounds-polynomial-systems (accessed on 1 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).