Abstract

Air quality prediction is a critical challenge amid rising environmental and health risks from pollution. This study conducts a systematic literature review (SLR) to compare traditional statistical models and machine learning (ML) techniques applied to air quality forecasting. Following the PRISMA 2020 protocol, 412 peer-reviewed articles (2016–2025) were analyzed using thematic filters and bibliometric tools. Results show a marked shift toward ML methods, particularly in Asia (73.2%), with limited representation from Latin America and Africa. Statistical models focused mainly on MLR (88.6%) and ARIMA (11.4%), while ML approaches (n = 574) included Random Forest, LSTM, and SVM. Only 12% of studies conducted direct comparisons. A total of 1177 predictor variables and 307 performance metrics were systematized, highlighting PM2.5, NO2, and RMSE. Hybrid models like CNN-LSTM show strong potential but face challenges in implementation and interpretability. This review proposes a consolidated framework to guide future research toward more explainable, adaptive, and context-aware predictive models.

1. Introduction

Air quality prediction has become a crucial field of research due to its impact on public health, climate change, and environmental sustainability. Increasing urbanization and industrialization have significantly increased the emission of air pollutants, requiring the development of accurate and adaptive predictive models to mitigate their adverse effects [1,2,3]. In this context, artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) have shown significant potential in overcoming the limitations of traditional statistical approaches in air quality prediction [4,5,6].

The literature has shown that the use of hybrid models, combining machine learning and deep learning techniques, substantially improves prediction accuracy in urban and rural environments [7,8,9]. In particular, the integration of advanced architectures such as LSTM and CNN has made it possible to capture complex temporal and spatial patterns in air pollution dynamics [10,11]. In addition, the combination of ensemble approaches has been widely adopted to increase the robustness of predictive models and reduce variability in forecasts [12,13,14].

On the other hand, the incorporation of real-time data from IoT sensors and monitoring networks has optimized the ability to respond to critical pollution events [15,16,17]. Furthermore, the use of numerical models combined with ML has proven to be effective in reducing uncertainty in air quality predictions, facilitating environmental policy decisions [18,19,20]. Despite these advances, challenges remain in generalizing models to different geographical and climatic contexts, underscoring the need for increasingly adaptive and explainable approaches [21,22].

In this sense, accurate air quality prediction is not only a fundamental tool for environmental risk mitigation but also a key component in the formulation of sustainable development strategies. The consolidation of artificial intelligence-based approaches, combined with physical and statistical models, is positioned as a promising avenue for improving air pollution management and its impact on global health [23,24,25].

Air quality prediction faces multiple methodological and operational challenges due to the complexity of atmospheric systems and the variability of pollutants. One of the most critical problems lies in the uncertainty inherent in predictive models, where the lack of integration between meteorological data, anthropogenic emissions, and atmospheric dynamics limits the accuracy of forecasts [1,2,3]. Furthermore, overfitting in machine learning models, resulting from noisy or insufficient data, reduces generalizability in different geographical and climatic contexts [4,5,6].

The scarcity of real-time data represents another significant challenge, especially in areas with limited monitoring infrastructure. The lack of extensive and high-quality time series makes it difficult to calibrate hybrid models, affecting the reliability of predictions [7,8,9]. Also, traditional statistical models have limitations in capturing nonlinear interactions between environmental variables, which has prompted the use of deep learning architectures such as LSTM and CNN [10,11]. However, these approaches still face interpretability issues and high computational requirements, which hinder their implementation in real-time monitoring systems [12,13,14].

Another relevant obstacle is the adaptability of models to different regions and climates. Transferring models trained in a specific context to other geographies has shown reductions in accuracy, especially when emission sources and atmospheric conditions vary substantially [15,16,17]. Reliance on numerical models, such as computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and Eulerian models, also presents challenges, as they require high computational costs and adequate parameterization to capture local variations [18,19,20].

Despite these problems, strategies have been developed to address these limitations, such as the use of ensemble approaches, fusion of physical models with machine learning, and optimization of feature selection techniques [21,22]. However, the need to improve the interpretability, computational efficiency, and adaptability of models remains a priority challenge in air quality prediction research [23,24,25].

A key research gap lies in the lack of systematic reviews and comprehensive state-of-the-art analyses comparing the wide range of modeling approaches used in air quality prediction. Out of the 412 studies analyzed, only a few qualify as either systematic reviews or state-of-the-art evaluations. These include reviews on urban air quality prediction models [26], indoor air pollution control strategies [27], computational and simulation methods in air quality modeling [28], and integrated forecasting systems using IoT, big data, and ML [29]. These efforts highlight the strengths and weaknesses of specific algorithms but fail to provide a comprehensive synthesis comparing ML and statistical approaches across geographies, pollutants, and data infrastructures.

Recent studies have demonstrated that robust machine learning frameworks are increasingly central to improving the detection and forecasting of air pollutants across diverse geographies and temporal scales. Ref. [30] proposed a data-driven approach that incorporates parameter optimization, data harmonization, and augmentation to construct parsimonious models with enhanced generalizability and interpretability. Their method, applied to over 30,000 ground-level air pollution records in Southern China, highlighted the potential of ML in capturing spatio-temporal pollutant patterns while addressing randomness and non-orthogonalities within complex environmental datasets. Ref. [31] further identified overlooked yet critical issues such as feature engineering, class imbalance, and validation strategies in ML-based environmental modeling. Their findings reinforce the importance of explainable models and the need for robust validation schemes to ensure real-world applicability. Complementing these perspectives, ref. [32] conducted a comprehensive review comparing machine learning and deep learning models, emphasizing the role of spatiotemporal modeling and external features, such as meteorological data, traffic patterns, and land use, in enhancing model accuracy. Their analysis confirms that deep learning techniques, particularly those capable of representing feature dependencies and spatial dynamics, are especially suited for pollution forecasting tasks. Collectively, these contributions illustrate the evolution and refinement of AI-driven approaches in air quality modeling, while advocating for more integrative, explainable, and context-aware methodologies.

Table 1 compares eight key systematic reviews of air quality prediction models. In contrast to previous studies, which address fragmented or algorithm-centered approaches, the present work introduces an integrative perspective, combining multiscale, geo-referenced, and thematic analysis. In addition, it employs advanced scientific visualization tools to map epistemological trends and regional gaps. This innovative approach allows not only the assessment of the technical performance of models but also their contextual adequacy and explainability.

Table 1.

Comparison of relevant systematic reviews.

The limited availability of systematic reviews and state-of-the-art studies suggests the need for further structuring of knowledge in this field, allowing consolidation of findings scattered in the literature and guiding future research towards more integrated and explanatory approaches. Therefore, the main objective of this study is to systematically compare traditional statistical models and machine learning techniques used in air quality prediction, highlighting their performance, applicability, and limitations across different geographic and environmental contexts. Additionally, the study aims to identify critical challenges and emerging opportunities in the implementation of predictive models, particularly regarding interpretability, generalization, and data integration. To achieve this, the study addresses the following research questions:

- RQ1: What are the main anthropogenic and natural factors affecting air quality?

- RQ2: How do machine learning models compare with statistical approaches in terms of accuracy, generalizability, and interpretability in air quality prediction?

- RQ3: What are the main challenges in implementing predictive air quality models?

2. Methodology

The use of PRISMA guidelines has consolidated methodological standards in systematic reviews, bringing rigor, clarity, and reproducibility to the scientific process [40]. In complex areas such as modelling environmental phenomena using artificial intelligence, their application allows for a more coherent integration of heterogeneous evidence [41,42]. In addition, tools such as flowcharts and extraction tables have proven useful in reducing bias and improving the traceability of the analysis [43]. This methodological adaptability has favored its incorporation in recent studies addressing technical and contextual challenges in the evaluation of predictive models [44,45]. Consequently, PRISMA is positioned as an essential framework for ensuring consistency and quality in frontier research.

2.1. Identification Stage

A systematic search was conducted in Scopus and ScienceDirect, following the recommended completeness guidelines for high-quality reviews [40,41]. The search strategy was designed to capture scientific literature on air pollution and predictive modelling, considering both statistical and artificial intelligence approaches. The Boolean equation (“air: pollution” OR “air quality”) AND (“prediction models” OR “statistical models” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning”), optimized to encompass multiple dimensions of the problem, was used. This procedure identified a large corpus of publications: 43,014 in Scopus and 215,021 in ScienceDirect. Thus, a broad and rigorous coverage of the state of the art was ensured, in accordance with the principles of methodological integrity in systematic reviews [42].

To ensure that the selected keywords were sufficiently comprehensive for capturing the scope of air pollution prediction using statistical and machine learning methods, a pilot search was conducted prior to the final query. This test phase included variations and synonyms such as “forecasting”, “air contaminants”, “AI-based models”, and “environmental modeling” to evaluate their relevance and retrieval volume. The final Boolean equation was refined based on this analysis to balance sensitivity (broad coverage) and specificity (topic relevance). Furthermore, keyword selection was cross-validated with descriptors used in existing systematic reviews and high-impact articles in the domain, confirming alignment with dominant terminologies in the field. This process helped minimize thematic omissions and improved the representativeness of the search corpus.

2.2. Filtering Stage

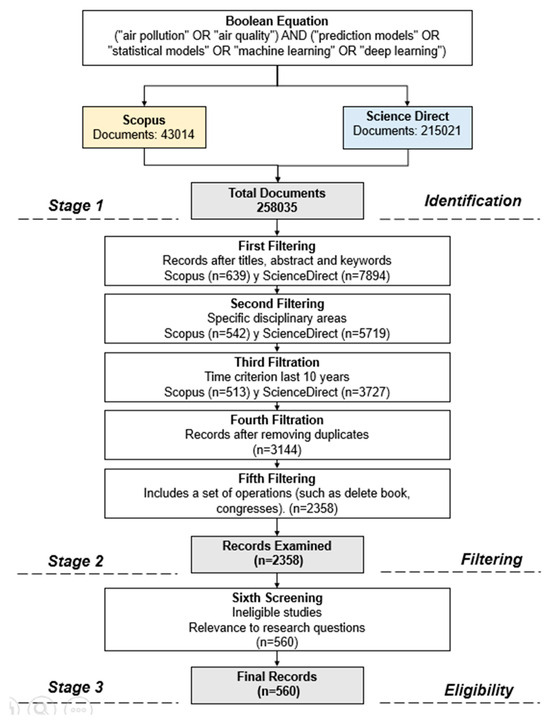

During the document selection process, a progressive filtering strategy was applied to ensure the thematic and scientific relevance of the included studies. Initially, 43,014 publications were identified in Scopus and 215,021 in ScienceDirect, representing 16.7% and 83.3% of the total, respectively. By restricting the search to titles, abstracts, and keywords, the corpus was reduced to 639 documents in Scopus (1.5% of the initial total) and 7894 in ScienceDirect (3.7%), which showed a first purification of 96.3%. Subsequently, the selection of specific disciplinary areas such as environmental science, environmental engineering, computer science, and multidisciplinary narrowed the sample to 542 records in Scopus (84.8% of the previous subset) and 5719 in ScienceDirect (72.5%). By incorporating the temporal criterion of the last 10 years, the documents were reduced to 513 in Scopus (94.6%) and 3727 in ScienceDirect (65.2%). Finally, after integrating both databases and applying a protocol for the elimination of exact duplicates (by title, author, and year), 354 redundant records were eliminated, consolidating a final corpus of 3144 unique publications, equivalent to 77.0% of the total filtered, suitable for systematic analysis and subsequent thematic coding (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Protocol of the systematic literature review (SLR).

2.3. Eligibility Stage: Analysis and Synthesis

This stage examined the relevance of each publication with respect to the research questions and specific inclusion criteria of the study. To this end, the titles, abstracts, keywords, and, where necessary, the full body of the articles were systematically reviewed. The detailed analysis led to the exclusion of 1946 studies that did not meet the established requirements, consolidating a total of 560 articles considered relevant for the analysis. The final phase of the PRISMA process consisted of a critical evaluation of the full content of the selected publications, applying rigorous filters focusing on air quality and predictive modelling. This procedure represented an 82.2% reduction of the corpus assessed in this phase, underlining both the methodological thoroughness and the thoroughness of the selection of studies that accurately address the key dimensions of this systematic review.

2.4. Quality Assessment Stage

As part of the methodological protocol, a rigorous quality assessment was implemented on the 560 preselected articles using the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) checklist. This tool provides a standardized framework for assessing completeness, clarity, and methodological rigor in systematic reviews with an exploratory approach [46]. The review was structured into 22 items distributed in seven key domains: title, abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion, and funding. Each publication was assessed on a binary basis (compliant/non-compliant), and compliant publications were classified according to their level of quality as high, medium, or low. Only studies with high scores were retained, reducing the final corpus to 412 articles. This refinement increased the internal reliability of the analysis, ensuring alignment with the principles of transparency and reproducibility promoted in the PRISMA 2020 statement [40], thus strengthening the scientific validity of the review.

Although air quality monitoring in opencast mining environments represents a critical subdomain due to its occupational and environmental health impacts, it was not included within the scope of this systematic review. The inclusion criteria were primarily focused on urban and regional air quality prediction models applied to ambient environments, using statistical and machine learning techniques. This thematic focus was selected to ensure coherence and comparability across the studies analyzed. Future reviews could specifically address industrial and extractive sectors, including mining operations, where different pollutant profiles, regulatory frameworks, and exposure conditions require dedicated modelling approaches.

- Registration statement

This systematic literature review was retrospectively registered in the Open Science Framework (OSF) under the title “Statistical and Machine Learning Models in Air Pollution Prediction: A Systematic Literature Review” (https://osf.io/2ce4y/) (accessed on 1 November 2025). The registration follows the PRISMA 2020 guidelines to ensure methodological transparency, traceability, and reproducibility throughout the identification, screening, and eligibility stages.

3. Results

From a temporal perspective, scientific production related to air quality prediction has shown a sustained upward trajectory over the last decade. Between 2016 and the first quarter of 2025, a steady growth in the number of publications is evident, from 2 papers in 2016 to a maximum of 106 in 2024. For the year 2025, as of March, 40 publications are recorded, which represents approximately 38% of the maximum value reached in the previous year, in line with the publication cycle still in progress. The linear trend, represented by the equation y = 9.7091x − 12.2, indicates an average growth of 9.7 papers per year, reflecting the growing interest of the scientific community in the development of predictive models applied to air pollution. This sustained behavior suggests that the topic has gone from being emerging to consolidating as a strategic line of research with a strong interdisciplinary component, integrating statistics, artificial intelligence, and environmental sciences.

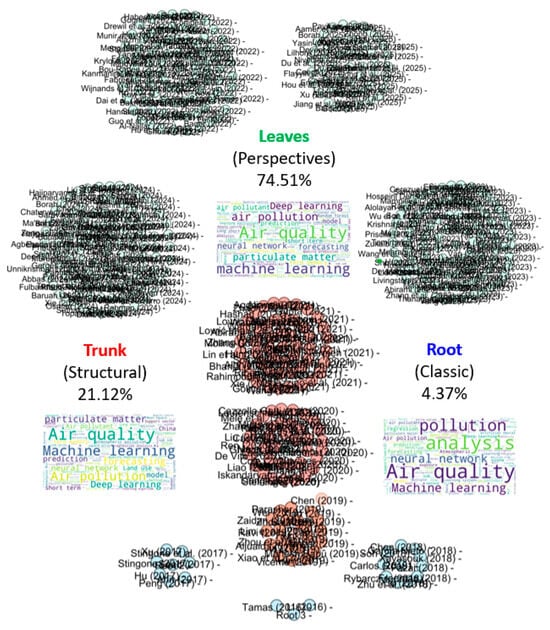

A taxonomic structural analysis of the scientific literature, based on the fields of author, year of publication, and keywords, using specialized computational tools, allows the academic contributions to be classified into three hierarchical levels of research maturity: roots (classics), trunk (structural), and leaves (perspectives), according to their methodological contribution and their position in the knowledge network. For the representation of the relationships between documents and the identification of thematic groupings, the Gephi software (v.0.10.0) was used, implementing the community detection algorithm proposed by [47] (Fast unfolding of communities in large networks), and the modular resolution was adjusted based on the principles of [48] on Laplacian Dynamics and Multiscale Modular Structure in Networks.

This methodological combination made it possible to visualize the structure of the co-citation network, identify nodes of high centrality, and map the hierarchical cohesion of disciplinary knowledge. In addition, the WordCloud text mining technique was applied to graphically represent the most recurrent terms in the keywords of each document group. This provided an additional semantic perspective that allowed us to recognize the thematic priorities and dominant conceptual frameworks at each level of maturity (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Science tree in the field of air quality prediction.

Based on this segmentation of the tree, the keywords were analyzed in three conceptual horizons:

- (i)

- Sheets—Perspectives (2022–2025, n = 307, 74.51%)

The documents from this period show a marked evolution towards advanced artificial intelligence, evidenced by the high frequency of terms such as machine learning, deep learning, LSTM, XGBoost, and real-time prediction. The prominent presence of air quality and PM2.5 indicates a strong alignment with international environmental monitoring standards. Also, concepts such as sensor networks, spatial resolution, and IoT emerge, reflecting a shift towards distributed, adaptive, and real-time operational capability architectures for air pollution prediction.

- (ii)

- Trunk—Structural (2019–2021, n = 87, 21.12%)

This set represents a methodological transition phase in which the performance of traditional statistical models is contrasted with machine learning-based approaches. Keywords such as regression, support vector machine, ensemble learning, and forecasting reveal a stage of experimentation and comparative validation. There is also a trend towards the integration of urban and meteorological data, aimed at improving accuracy and generalization in scenarios of high environmental complexity.

- (iii)

- Root—Classics (≤2018, n = 18, 4.37%)

Foundational papers, although scarce, provide the epistemological basis of the field. Terms such as air quality index, linear regression, exposure, and pollutant concentration predominate, evidencing a descriptive and deterministic approach. At this stage, predictive models are built with linear techniques and without the integration of dynamic variables or learning architectures. Although their predictive capacity was limited, these studies defined the metrics, indicators, and monitoring methodologies that are still in place as a starting point for subsequent developments.

From a review of 412 papers, 194 city-specific studies were identified. These were selected based on a manual screening of article titles, including only those that explicitly mentioned both a city and a country, indicating a clearly localized application of predictive modeling. The geographic classification was based on the city analyzed in each study, not the authors’ institutional affiliation. Although some cities, such as Beijing or New Delhi, appear multiple times, each record represents a unique study with different methodologies, datasets, or modeling frameworks.

The geographical distribution of these city-specific studies shows a clear dominance of Asia with 73.20% of the cases, followed by Europe and North America with 9.79% each. In contrast, Africa and South America have a significantly lower share, with only 5.15% and 1.03%, respectively, as does Oceania (1.03%). This distribution reveals a strong concentration of research in Asia and a notorious under-representation in regions such as Africa and South America, where, despite facing serious environmental challenges, applied scientific production in air quality through machine learning remains limited (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Geographical distribution of case studies on air quality.

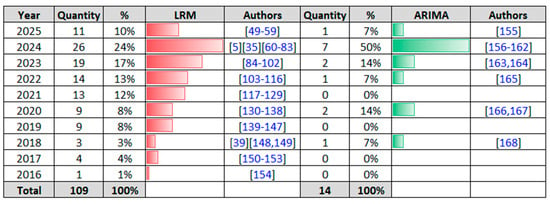

3.1. Typology of Applied Predictive Models

From the sample of 412 articles analyzed by a systematic review, 123 studies were identified that implement traditional statistical models in the prediction of air quality. Of these, 109 employed multiple linear regression (MLR), representing 88.6% of the total number of statistical models detected. In contrast, only 14 articles used ARIMA models (11.4%), mainly applied to time series with seasonal components. This distribution shows a strong preference for linear parametric approaches in the reviewed papers, despite the increasing demands of modeling in complex and nonlinear environments (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Traditional statistical models [5,35,39,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168].

The results suggest a structural dependence of the literature on multiple linear regression, even in contexts where the relationships between variables are clearly nonlinear. The prevalence of MLR could be attributed to its low computational threshold, its ease of interpretation, and its widespread integration in regulatory and policy environments. However, this methodological hegemony contrasts with the limited ability of MLR to capture dynamic interactions, multivariate dependencies, or non-stationary effects common in urban atmospheric environments. The low use of the ARIMA model is striking, given its natural fit to time series. However, its application is usually limited to contexts with strong seasonality and structured data. In sum, the findings expose a relevant methodological gap: a technical choice based on familiarity, rather than appropriateness to the phenomenon, persists. This tendency limits the exploration of emerging approaches with greater predictive and adaptive capacity, particularly in the face of the increasing complexity of contemporary environmental systems.

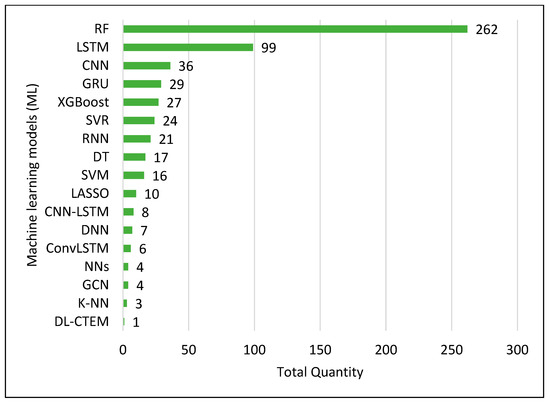

On the other hand, multiple machine learning (ML) models applied individually or in combination were identified, resulting in 574 records of ML model use. This figure reflects that several studies implemented more than one technique for comparative or complementary purposes. The most used models were Random Forest (RF) with 262 appearances (45.6%), followed by Support Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) with 99 mentions (17.2%) and Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) with 36 records (6.3%). Other models such as GRU, XGBoost, SVR, and RNN also showed a significant presence, although with lower relative frequency (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Machine learning models (ML).

The high recurrence of Random Forest (RF) in the literature reflects its position as a robust, versatile, and effective technique for noisy or unstructured datasets. Its ability to handle nonlinear relationships, together with its accessible implementation in languages such as Python and R, explains its relative dominance. The rise of LSTM models indicates a methodological transition towards architectures specialized in complex temporal sequences, aligned with the dynamic nature of air pollution.

However, the fact that many studies combine multiple algorithms reflects a key phenomenon: the field is no longer oriented towards finding an ‘optimal model’, but rather towards comparing performance by context, variable and scale. This pattern reveals a scientific maturation, but also exposes the urgent need for more standardized evaluation frameworks that allow replicable and generalizable comparisons between models of different natures.

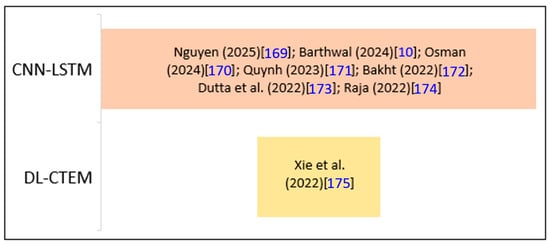

In the systematic review of the total number of articles, 11 applications of hybrid or advanced models were identified, defined by their ability to integrate spatial dynamics, temporal dynamics, or multiple deep learning techniques. The most representative model was CNN-LSTM, with 7 entries (87.5%), evidencing its acceptance as the dominant architecture in multivariate sequential prediction environments. Le and DL-CTEM with 1 occurrence (12.5%). Although their frequency is lower compared to other approaches, their structural sophistication positions them as a key methodological frontier in air quality modelling (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Hybrid or advanced models [10,169,170,171,172,173,174,175].

The presence of hybrid models such as CNN-LSTM in the analyzed literature confirms a trend towards architectures designed to simultaneously capture spatial patterns and temporal sequences, particularly relevant in urban environments with high atmospheric variability. Despite their computational complexity, these models demonstrate a high capacity for generalization and error reduction in multivariate pollution series.

The use of the DL-CTEM model, although sporadic, suggests an emerging interest in approaches capable of estimating latent multi-pollutant interactions by deep learning. However, the overall low proportion of hybrid models points to a persistent barrier in their adoption, probably linked to implementation challenges, lack of interpretability and need for advanced computational resources. This evidences a dissociation between the technical potential of these models and their practical application in regulatory and operational contexts.

3.2. Variables Used in Modeling

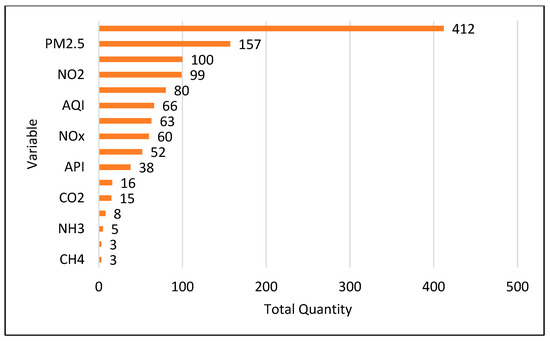

The systematic review identified 1177 individual records of variables used in predictive air quality models, indicating that many studies integrate multiple types of variables in the same architecture. The most used variable was CO with 412 mentions (35.0%), followed by PM2.5 (13.3%), PM10 (8.5%), NO2 (8.4%) and O3 (6.8%). Indicators such as AQI (5.61), SO2 (5.35), NOx (5.10), ozone (4.42) and complementary variables such as API, deaths and CO2 also stood out.

This wide diversity suggests a clear orientation towards multivariate models, which seek to capture not only the concentration of pollutants, but also their interactions with chemical, meteorological and health factors (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Types of variables.

The predominance of classical pollutant variables such as CO, PM2.5 and NO2 reveals the persistence of traditional criteria in air quality prediction. However, the increasing inclusion of health and contextual variables, such as mortality or CO2, suggests a progressive shift towards epidemiological and integrated models. This expansion in the use of variables poses new challenges, including the need for harmonization in the selection of predictors, imputation techniques for missing variables, and contextual cross-validation. Consequently, future research should move towards standardized comparative frameworks that not only optimize accuracy, but also ensure robustness and transferability between urban, industrial and rural contexts.

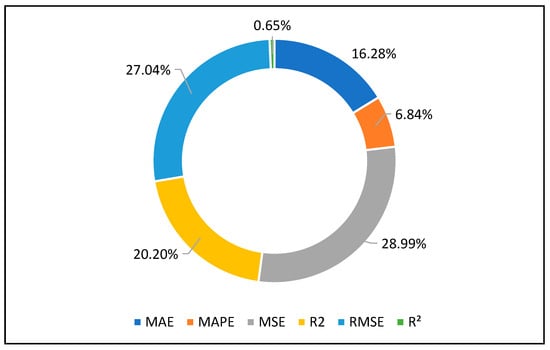

3.3. Performance Evaluation Indicators

Of the total sample, 307 records of predictive performance evaluation indicators were identified, evidencing a combined use of metrics in various studies. The most used indicator was the mean square error (MSE) with 89 mentions (28.99%), followed by the root mean square error (RMSE) with 83 (27.04%) and the coefficient of determination (R2/R2) with 64 combined records (20.85%). Other metrics such as mean absolute error (MAE) (16.28%) and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) (6.84%) also showed relevant presence. This distribution reveals a generalized preference for metrics focused on the precision of the fit, particularly those that penalize large deviations, such as RMSE and MSE (see Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Evaluative comparison of errors.

The dominant use of metrics such as MSE and RMSE in the studies reviewed reflects an inclination to assess overall model fit, albeit often at the expense of direct interpretations by decision-makers. The low adoption of standardized indicators such as MAPE or explanatory indicators such as R2 suggests a lack of methodological consensus on what constitutes “acceptable” or comparable performance across studies. This imbalance hinders the replicability of results and limits the portability of models across geographical and temporal contexts. Therefore, greater standardization in the use of metrics is recommended, with emphasis on their suitability to the type of variable, prediction horizon and practical application of the model.

3.4. Comparison Between Statistical and Machine Learning Models

Based on the 24 studies that explicitly compare traditional statistical models with machine learning techniques in air quality prediction, there is an emerging body of literature aimed at contrasting parametric and non-parametric approaches under standardized metrics. Most research adopts (MLR) as a benchmark, contrasted mainly with Random Forest (RF), due to its ability to handle nonlinear relationships and correlated variables [43,52,54,61,82,84,97,106,121,132,142,147,150,152]. Additional comparisons between MLR and SVR, LSTM, GRU, RNN and XGBoost reflect a trend towards hybrid and multilayer models, capable of capturing complex patterns and multivariate temporal sequences [5,55,56,57,61,65,68,69,74,79,99,112,117,120,123,125,144]. Despite the methodological heterogeneity, a common pattern is identified: machine learning models tend to outperform statistical models in dense or highly dynamic urban environments, particularly in non-stationary time series or data with structural noise. However, the limited interpretability of some advanced models and the absence of replicable comparative frameworks limit their applicability in public policy decisions. Therefore, the development of systematic comparative studies that integrate precision, explainability and contextual sensitivity as simultaneous evaluation criteria is urgently needed.

The comparative studies reviewed confirm that machine learning models tend to outperform traditional statistical approaches in accuracy and generalizability, especially in dense urban contexts, with high temporal variability or nonlinear data structures [52,55,97]. This advantage is more evident in models such as RF, SVR or LSTM, whose architecture allows handling complex relationships and multivariate time series [61,69,99]. Nevertheless, statistical models such as MLR maintain their relevance due to their low computational cost and high interpretability, being preferred in studies for normative or exploratory purposes [106,120,147]. The comparison reveals an unresolved methodological tension between accuracy and explainability, with advanced models offering better error metrics—RMSE and MSE—but poor causal tractability [74,112]. Given this trade-off, it is suggested to move towards comparative frameworks that simultaneously weight accuracy, explainability and contextual robustness, which would enable informed adoption of predictive models in environmental public policy decisions [117,125,152].

3.5. Factors, Performance, and Challenges in the Implementation of Predictive Air Quality Models

This section presents the key findings of the systematic review in terms of the factors affecting air quality, the performance comparison between statistical and machine learning models, and the main technical and operational challenges in their implementation. The empirical evidence allows us to answer the three research questions posed in a structured way.

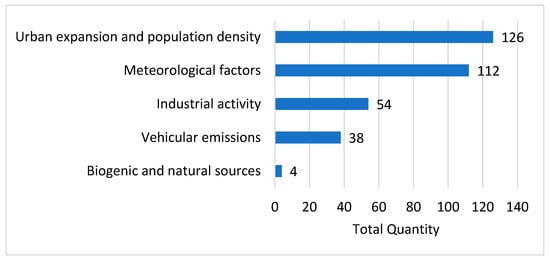

- RQ1: What are the main anthropogenic and natural factors affecting air quality?

From the analysis of 412 systematically reviewed scientific articles, 236 studies (57.28%) explicitly address factors affecting air quality, revealing a predominance of approaches to local, climatic and urban conditions. Meteorological factors (n = 112, 47.46%) represent the most addressed category, reflecting the sensitivity of air pollutant behavior to variables such as temperature, humidity, wind and precipitation, especially in monsoon regions or regions of high seasonal variability [143,176,177,178,179]. This is followed by urban sprawl and population density factors (n = 126, 53.39%), concentrated in dense urban environments where the combination of mobile and stationary sources exacerbates exposure levels to pollutants such as PM2.5 and NO2 [89,100,180,181,182].

Industrial activity appears in 54 studies (22.88%), with emphasis on geographic areas such as East Asia and highly industrialized regions of the global south, where continuous emissions of SO2, NOx and volatile organic compounds are identified [33,183,184]. For their part, vehicular emissions are highlighted in 38 articles (16.10%), mostly in urban contexts of developing countries, where the growth of the vehicle fleet and technological obsolescence aggravate pollution levels [185,186,187,188]. Finally, only 4 studies (1.69%) make explicit reference to biogenic or natural sources such as forest fires, dust storms, or volcanic eruptions, which highlights an important gap in the scientific literature regarding the interaction between natural processes and air quality, especially in regions vulnerable to extreme events [189,190,191,192] (see Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Factors affecting air quality.

These results evidence a predominantly anthropogenic approach in the current scientific literature, underscoring the need to more systematically integrate the natural and biogenic dimensions in future studies, particularly under scenarios of climate change and environmental vulnerability. Furthermore, the variation of factors according to geographical context-urban-industrial vs. natural-rural-suggests the urgency of adaptive predictive models that incorporate both sources and local conditions, thus improving the accuracy and relevance of air quality mitigation and management strategies [52,76].

- RQ2: How do machine learning models compare with statistical approaches?

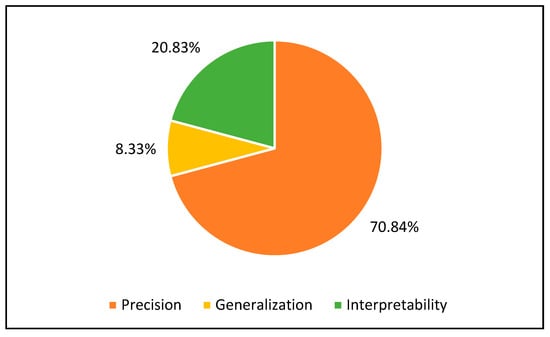

Analysis of the 24 studies comparing statistical and machine learning models reveals that accuracy has been the most explored axis, with 17 investigations (70.8%) focused on improving predictive fit [50,52,54,55,56,61,68,79,82,84,99,121,132,142,144]. In contrast, only 5 studies (20.8%) addressed interpretability as a main criterion [65,106,147,150,152], and 2 studies (8.3%) explicitly focused on the generalizability of the model [97,123,193].

This methodological imbalance suggests that, although advances in accuracy are remarkable, the scientific community still faces important challenges in the systematic integration of explanatory and adaptive dimensions. Consequently, it is urgent to promote comprehensive comparative evaluations that simultaneously weigh accuracy, causal tractability and contextual robustness as pillars for the selection and application of predictive models in air quality (see Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Model comparisons.

- RQ3: What are the main challenges in the implementation of predictive air quality models?

Systematic analysis of 412 studies identified a number of persistent challenges and emerging opportunities in the implementation of predictive air quality models. Key challenges include heterogeneity in data quality and resolution [123,193], low coverage of monitoring networks in critical regions [160,184], and limited interpretability of complex models [105,194]. Despite this, the literature also evidences promising opportunities such as the integration of satellite sensors and IoT, the advancement of robust spatiotemporal models, and the use of explainable interpretation techniques such as SHAP or LIME [184,195]. This duality highlights the urgency of methodological frameworks that not only prioritize accuracy but also traceability and contextual adaptability. Table 2 synthesizes these elements, providing a structured view of the current tensions and possibilities in the development of applicable, replicable, and sustainable predictive systems.

Table 2.

Challenges and opportunities.

These opportunities are already being implemented in recent studies. For example, refs. [123,193] applied a combination of satellite imagery and IoT sensors to enhance air quality monitoring in data-scarce regions, significantly improving spatial resolution. In terms of model generalizability, refs. [69,74] successfully applied transfer learning techniques to adapt deep learning models trained in Asia for use in African urban environments with minimal data, demonstrating substantial improvements in performance. To address complexity and computational cost, ref. [52] implemented autoencoders for dimensionality reduction, enabling faster real-time predictions with lower resource consumption. Furthermore, refs. [105,195] utilized SHAP and LIME to provide explainability in deep learning models, helping researchers and policymakers better understand model decisions. These cases highlight how current research is actively transforming the challenges in predictive air quality modeling into actionable and scalable innovations.

4. Discussion

4.1. Models Used and Overall Performance

The systematic review of 412 studies on air quality prediction reveals a field in methodological evolution, marked by a transition from conventional statistical approaches to advanced machine learning (ML) architectures. Multiple linear regression (MLR), present in 88.6% of the studies with statistical models, remains predominant due to its interpretative simplicity and low computational cost. However, its predictive capacity is limited in the face of nonlinear phenomena and complex urban dynamics. In contrast, ML techniques such as Random Forest (45.6%) and Long Short-Term Memory networks (LSTM) (17.2%) demonstrate superior performance in handling noisy data and multivariate temporal sequences. Comparative analysis of 24 selected studies reveals that 70.8% emphasize predictive accuracy, while only 20.8% address interpretability and 8.3% consider generalization. These figures reflect a methodological bias favoring performance over transparency and transferability. In general, deep learning models tend to outperform traditional models in terms of accuracy, especially in urban scenarios with complex temporal dynamics. However, this advantage is often offset by increased computational demand and reduced interpretability, creating a gap between model sophistication and practical implementation.

4.2. Specific Applications of ML Models

Recent research shows that different ML models excel in specific prediction tasks: (i) Random Forest and Gradient Boosting Machines have been effective for short-term AQI forecasting and identifying variable importance in urban environments. (ii) LSTM and GRU models are better suited for long-term and sequential predictions where pollutant levels exhibit temporal dependencies. (iii) Hybrid models, such as CNN-LSTM and GAN-based ensembles, offer robust results in scenarios with high variability and missing data. (iv) Transfer learning has proven particularly useful in applying models trained in data-rich regions to data-scarce areas, with studies showing successful adaptation across continents [69,74].

These differentiated strengths suggest that no single model universally outperforms others; rather, model selection should be aligned with the data characteristics and intended prediction horizon.

4.3. Guidelines for Model Selection

To enhance the practical utility of this review, we propose the following model selection criteria based on the findings: (i) Data availability: Use deep learning models (e.g., LSTM, CNN) when large labeled datasets are available. In contrast, opt for ensemble models (e.g., RF, XGBoost) when working with medium-sized datasets or heterogeneous data. (ii) Interpretability needs: For applications requiring transparency (e.g., public health policy), models with interpretable outputs or enhanced with SHAP/LIME should be prioritized. (iii) Geographical transferability: When applying models in under-monitored or developing regions, hybrid or transfer learning models offer superior adaptability. (iv) Temporal vs. spatial resolution: Spatiotemporal models combining CNNs with RNNs are more appropriate when both dimensions must be modeled simultaneously.

By applying these guidelines, researchers and practitioners can better align their model choice with specific goals, data constraints, and operational contexts.

4.4. Integration of Diverse Data and Emerging Opportunities

Recent contributions emphasize the increasing importance of integrating heterogeneous data sources, such as traffic patterns, meteorological conditions, satellite imagery, land use information, and mobile sensor data, to enhance the robustness and spatiotemporal resolution of air quality models.

- Smart Cities and Data Openness: Studies by [178,197] demonstrate that open-access urban sensing platforms and automated AI-based systems (e.g., AI-Air) significantly improve model responsiveness and real-time forecasting accuracy. These platforms enable continuous updates, increase model efficiency, and reduce systematic biases when compared to traditional deterministic models.

- Sustainable Development Synergies: Studies by [198,199] illustrate how machine learning frameworks can better capture complex, nonlinear relationships among environmental, social, and economic dimensions of sustainability. This integration contributes to more context-sensitive and operationally relevant decision-making tools.

- Citizen Science and Community Engagement: Studies by [199,200] show how participatory data collection using low-cost mobile sensors empowers communities and enhances spatial granularity. These approaches allow detection of localized pollution episodes, particularly in under-monitored regions, and foster co-creation of air sensing schemes through inclusive citizen engagement.

- Algorithmic Innovations and Explainability: ref. [178] present an automated ML system that improves forecasting accuracy for both inland and coastal urban areas. This work highlights the role of AI-enhanced methods in identifying key meteorological drivers of pollution and correcting overestimation or underestimation errors. Furthermore, the use of explainability tools such as SHAP and LIME ensures transparency in predictive outputs.

Together, these findings point toward a methodological evolution in air quality prediction, where the convergence of data openness, citizen participation, and algorithmic sophistication leads to more inclusive, adaptive, and operationally viable models. This transition supports not only scientific advancement but also equitable access to environmental knowledge and data-driven public policy.

4.5. Regulatory Considerations and Industry Standards

While this study focuses primarily on modeling techniques and computational performance, it is essential to recognize that national and international air quality standards (e.g., WHO, EPA, EU directives) are critical in interpreting predictions and guiding intervention strategies. Given the heterogeneity of regulatory thresholds across countries and industries, a comprehensive analysis of such frameworks falls beyond the scope of this methodological review. However, future work could explore how predictive models align with these standards and support compliance strategies in sectors such as transportation, mining, and urban planning.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review, structured under the PRISMA 2020 guidelines, provides a comprehensive overview of the state of the art in air quality prediction, consolidating scattered empirical evidence into a rigorous and replicable body of knowledge. The analysis of 412 articles demonstrates a clear methodological transition from traditional statistical models, dominated by multiple linear regression (MLR), to machine learning approaches such as Random Forest and LSTM, valued for their ability to model nonlinear relationships and complex patterns. However, this technical evolution has not been accompanied by proportional advances in interpretability and generalization, dimensions that continue to be underexplored, as revealed by the fact that only 20.8% of the studies focus on explainability and only 8.3% on contextual robustness. At the variable level, a focus on classical pollutants persists, with little incorporation of biogenic or health factors. The challenges identified—data heterogeneity, low standardization of metrics, and computational barriers—coexist with significant opportunities such as the adoption of hybrid architectures, use of remote sensing, and advanced interpretation techniques. In this sense, it is proposed that future lines of research prioritize integrative comparative frameworks, capable of balancing precision, explainability, and transferability between diverse geographic contexts. In addition, it is recommended to promote studies focused on underrepresented regions such as Latin America and Africa, promoting the development of adaptive models that respond to the environmental and social complexity of these territories.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.B.P., T.G., G.H.-V. and C.M.; Formal Analysis, G.H.-V. and J.R.C.-H.; Funding Acquisition, T.G.; Investigation, L.B.P., T.G., G.H.-V., C.M. and J.R.C.-H.; Methodology, T.G., G.H.-V. and J.R.C.-H.; Project Administration, G.H.-V. and J.R.C.-H.; Resources, T.G. and J.R.C.-H.; Software, L.B.P., C.M. and G.H.-V.; Supervision, G.H.-V. and J.R.C.-H.; Validation, C.M., G.H.-V. and J.R.C.-H.; Visualization, G.H.-V.; Writing—Original Draft, L.B.P. and G.H.-V.; Writing—Review and Editing, L.B.P. and G.H.-V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We are thankful for the grants from projects Universidad Estatal Peninsula Santa Elena, Ecuador, provided to researcher T.G.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the grants awarded to researcher T.G. by the projects of the Universidad Estatal Península Santa Elena, Main Campus, Av. La Libertad, 240204, Ecuador.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| List of Machine Learning Acronyms | |

| RF | Random Forest: ensemble of decision trees for classification or regression |

| K-NN | K-Nearest Neighbors: classification based on proximity to k closest neighbors |

| LASSO | Linear regression with L1 penalty for feature selection |

| DT | Decision Tree: sequential decision-making structure |

| SVR | Support Vector Regression: regression using support vector machines |

| XGBoost | Extreme Gradient Boosting: optimized and efficient boosting algorithm |

| DNN | Deep Neural Network: multilayered neural architecture |

| Stacked-BDLSTM | Bidirectional LSTM stacked for time series modeling |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory: RNN specialized in long temporal sequences |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network: neural network with memory of prior states |

| GRU | Gated Recurrent Unit: efficient LSTM variant |

| DTMC | Discrete Time Markov Chain: stochastic prediction using transition probabilities |

| EML | Extreme Machine Learning: single-layer fast neural network |

| NNs | Classical Neural Networks |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine: margin-based classifier |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network: spatial pattern extraction in time series |

| Bayesian LSTM | LSTM with Bayesian inference optimization |

| CNN-LSTM | Combined CNN and LSTM model |

| DL-CTEM | Deep Learning Complex Trait Estimation Model for industrial gas prediction |

| ConvLSTM | Convolutional LSTM: LSTM with spatial convolution layers |

| GCN | Graph Convolutional Network: graph-based deep learning for spatial dependencies |

| List of Target Variables and Air Pollutants | |

| PM2.5 | Fine particulate matter (≤2.5 µm), highly penetrative and harmful |

| PM10 | Coarse particulate matter (≤10 µm), affects upper respiratory tract |

| AQI | Air Quality Index: composite air quality score |

| Ozone/O3 | Tropospheric ozone, a secondary pollutant causing respiratory irritation |

| NO2 | Nitrogen dioxide, from traffic and industrial combustion |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide, greenhouse gas |

| H2S | Hydrogen sulfide, toxic industrial gas |

| NH3 | Ammonia, emitted from fertilizers and waste |

| SO2 | Sulfur dioxide, from fossil fuel combustion |

| CO | Carbon monoxide, from incomplete combustion |

| NOx | Nitrogen oxides, precursors to ozone and smog |

| CFCs | Chlorofluorocarbons, ozone-depleting substances |

| Propylene | Volatile organic compound from industrial sources |

| CH4 | Methane, powerful greenhouse gas |

| HC | Hydrocarbons, ozone and smog precursors |

| Deaths | Deaths attributable to poor air quality |

| API | Air Pollution Index: alternative pollution index used in some regions |

References

- Pak, A.; Rad, A.K.; Nematollahi, M.J.; Mahmoudi, M. Application of the Lasso regularisation technique in mitigating overfitting in air quality prediction models. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dongre, P.K.; Patel, V.; Bhoi, U.; Maltare, N.N. An outlier detection framework for Air Quality Index prediction using linear and ensemble models. Decis. Anal. J. 2025, 14, 100546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindiran, G.; Karthick, K.; Rajamanickam, S.; Datta, D.; Das, B.; Shyamala, G.; Hayder, G.; Maria, A. Ensemble stacking of machine learning models for air quality prediction for Hyderabad City in India. iScience 2025, 28, 111894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omer, M.; Ali, S.J.; Raza, S.M.; Le, D.-T.; Choo, H. Integrating Temporal Analysis with Hybrid Machine Learning and Deep Learning Models for Enhanced Air Quality Prediction. In Proceedings of the 2025 19th International Conference on Ubiquitous Information Management and Communication (IMCOM), Bangkok, Thailand, 3–5 January 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi, P. Air Quality Prediction System Using Machine Learning Models. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2024, 235, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadriddin, Z.; Mekuria, R.R.; Gaso, M.S. Machine Learning Models for Advanced Air Quality Prediction. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Systems and Technologies 2024, Ruse, Bulgaria, 14–15 June 2024; pp. 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, H.K.; Patel, P.K.; Singh, S. Evaluation of Predictive Models for Air Quality Index Prediction in an Indian Urban Area. J. Indian Assoc. Environ. Manag. (JIAEM) 2024, 42, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Dawar, I.; Singal, M.; Singh, V.; Lamba, S.; Jain, S. Air Quality Prediction Using Machine Learning Models: A Predictive Study in the Himalayan City of Rishikesh. SN Comput. Sci. 2024, 5, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pande, C.B.; Radhadevi, L.; Satyanarayana, M.B. Evaluation of machine learning and deep learning models for daily air quality index prediction in Delhi city, India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthwal, A.; Goel, A.K. Advancing air quality prediction models in urban India: A deep learning approach integrating DCNN and LSTM architectures for AQI time-series classification. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2024, 10, 2935–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-H.; Chen, P.-H.; Yang, C.-S.; Chuang, L.-Y. Analysis and Forecasting of Air Pollution on Nitrogen Dioxide and Sulfur Dioxide using Deep Learning. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 165236–165252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochadiani, T.H. Prediction of Air Quality Index Using Ensemble Models. J. Appl. Inform. Comput. 2024, 8, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B. Comparative Investigation of Machine Learning and Deep Learning Approaches for Air Quality Prediction. ITM Web Conf. 2024, 73, 02002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutar, A.; Rane, K.P.; Bansal, R.P.; Srivastava, V.; Prasad, P.V.; Lakshmi, T.R. A Legal Optimized Hybrid Deep Learning Models for Enhanced Real-Time Air Quality Prediction and Environmental Monitoring Using LSTM and CNN Architectures. Libr. Prog.-Libr. Sci. Inf. Technol. Comput. 2024, 44, 22091. [Google Scholar]

- Vonitsanos, G.; Panagiotakopoulos, T.; Kameas, A. Comparative Analysis of Time Series and Machine Learning Models for Air Quality Prediction Utilizing IoT Data. In IFIP International Conference on Artificial Intelligence Applications and Innovations; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 221–235. [Google Scholar]

- Aldape-Pérez, M.; Argüelles-Cruz, A.J.; Rodríguez-Molina, A.; Villarreal-Cervantes, M.G. Air Quality Prediction in Smart Cities Using Wireless Sensor Network and Associative Models. In International Congress of Telematics and Computing; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 216–240. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.; Han, H.; Wang, W.; Kang, Y.; Lee, H.; Kim, H.S. Application of deep learning models and network method for comprehensive air-quality index prediction. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X. Construction of Air Pollutant Monitoring and Air Quality Prediction Models based on Optimized Random Forests. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Integrated Intelligence and Communication Systems (ICIICS), Kalaburagi, India, 24–25 November 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, F.; Amanollahi, J.; Reisi, M.; Darand, M. Prediction of air quality using vertical atmospheric condition and developing hybrid models. Adv. Space Res. 2023, 72, 1172–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehshiri, S.S.H.; Firoozabadi, B. A multi-objective framework to select numerical options in air quality prediction models: A case study on dust storm modeling. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 863, 160681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Chau, L.; Miao, Y.; Lee, P.U.S. Prediction of Indoor Bioaerosol Concentrations from Indoor Air Quality Sensor Data by Artificial Intelligence Models. Patent Application No. 17/992,232, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fathi, S.; Makar, P.; Gong, W.; Gordon, M.; Zhang, J.; Hayden, K. A New Plume Rise Algorithm—Incorporating the Thermodynamic Effects of Water for Plume Rise Prediction in Air Quality Models. In Proceedings of the 25th EGU General Assembly, Vienna, Austria, 23–28 April 2023; p. EGU-7984. [Google Scholar]

- Gradišar, D.; Shao, H.; Grašič, B. Evaluation of Delta Tool for comparison of different Air Quality Prediction models. Sci. Eng. Educ. 2018, 3, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, S. Assessment of prediction accuracy in autonomous air quality models. Desalin. Water Treat. 2016, 57, 1322–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatram, A.; Tripathi, A.; France, F. Comparison and Performance Evaluation of CFD based Numerical Model and Gaussian based Models for Urban Air Quality Prediction. In Proceedings of the Conference of the Air and Waster Management Association, San Diego, CA, USA, 22–26 June 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Croitoru, C.; Nastase, I. A state of the art regarding urban air quality prediction models. E3S Web Conf. 2018, 32, 01010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Martín, J.; Kraakman, N.J.R.; Pérez, C.; Lebrero, R.; Muñoz, R. A state–of–the-art review on indoor air pollution and strategies for indoor air pollution control. Chemosphere 2021, 262, 128376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Harbawi, M. Air quality modelling, simulation, and computational methods: A review. Environ. Rev. 2013, 21, 149–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwar, A.; Singh, S.; Mishra, R.; Prakash, S. The state-of-the-art in air pollution monitoring and forecasting systems using IoT, big data, and machine learning. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2023, 130, 1699–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwitondi, K.; Mak, H.W.L. Robust Machine Learning Algorithmic Rules for Detecting Air Pollution in the Lower Parts of the Atmosphere. Data Sci. J. 2025, 24, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Zhan, Y.; Yang, F. A review of machine learning for modeling air quality: Overlooked but important issues. Atmos. Res. 2024, 300, 107261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbagna, L.; Saheer, L.B.; Oghaz, M.M.D. AI-driven approaches for air pollution modelling: A comprehensive systematic review. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 373, 125937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Z.; Li, H.; Chen, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y. Advancements in machine learning for spatiotemporal urban on-road traffic-air quality study: A review. Atmos. Environ. 2025, 346, 121054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbehadji, I.E.; Obagbuwa, I.C. Systematic Review of Machine Learning and Deep Learning Techniques for Spatiotemporal Air Quality Prediction. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essamlali, I.; Nhaila, H.; El Khaili, M. Supervised machine learning approaches for predicting key pollutants and for the sustainable enhancement of urban air quality: A systematic review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houdou, A.; El Badisy, I.; Khomsi, K.; Abdala, S.A.; Abdulla, F.; Najmi, H.; Obtel, M.; Belyamani, L.; Ibrahimi, A.; Khalis, M. Interpretable machine learning approaches for forecasting and predicting air pollution: A systematic review. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2024, 24, 230151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, J.; Dutta, M.; Marques, G. Machine Learning for Indoor Air Quality Assessment: A Systematic Review and Analysis. Environ. Model. Assess. 2024, 30, 417–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaini, N.; Ean, L.W.; Ahmed, A.N.; Malek, M.A. A systematic literature review of deep learning neural network for time series air quality forecasting. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 4958–4990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybarczyk, Y.; Zalakeviciute, R. Machine learning approaches for outdoor air quality modelling: A systematic review. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Moher, D. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: Development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 134, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Page, M.J.; Pritchard, C.C.; McGuinness, L.A. PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rethlefsen, M.L.; Page, M.J. PRISMA 2020 and PRISMA-S: Common questions on tracking records and the flow diagram. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2022, 110, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tugwell, P.; Tovey, D. PRISMA 2020. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 134, A5–A6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastidas-Orrego, L.M.; Jaramillo, N.; Castillo-Grisales, J.A.; Ceballos, Y.F. A systematic review of the evaluation of agricultural policies: Using prisma. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taneja, S.; Jaggi, P.; Jewandah, S.; Ozen, E. Role of social inclusion in sustainable urban developments: An analyse by PRISMA technique. Int. J. Des. Nat. Ecodynamics 2022, 17, 937–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondel, V.D.; Guillaume, J.L.; Lambiotte, R.; Lefebvre, E. Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2008, 2008, 10008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambiotte, R.; Delvenne, J.C.; Barahona, M. Laplacian dynamics and multiscale modular structure in networks. arXiv 2009, arXiv:0812.1770. Available online: http://arxiv.org/pdf/0812.1770v3.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Ordenshiya, K.; Revathi, G. A comparative study of traditional machine learning and hybrid fuzzy inference system machine learning models for air quality index forecasting. Int. J. Data Sci. Anal. 2025, 20, 4321–4342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emeç, M.; Yurtsever, M. A novel ensemble machine learning method for accurate air quality prediction. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 22, 459–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, A.; Quaff, A.R. Advanced machine learning techniques for precise hourly air quality index (AQI) prediction in Azamgarh, India. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2025, 19, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousan, S.; Wu, R.; Popoviciu, C.; Fresquez, S.; Park, Y.M. Advancing Low-cost Air Quality Monitor Calibration with Machine Learning Methods. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 374, 126191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, T.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, X.; Wu, Q.; Meng, C.; Deng, Q. Air pollution and prostate cancer: Unraveling the connection through network toxicology and machine learning. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 292, 117966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colléaux, Y.; Willaume, C.; Mohandes, B.; Nebel, J.-C.; Rahman, F. Air pollution monitoring using cost-effective devices enhanced by machine learning. Sensors 2025, 25, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pande, C.B.; Radwan, N.; Heddam, S.; Ahmed, K.O.; Alshehri, F.; Pal, S.C.; Pramanik, M. Forecasting of monthly air quality index and understanding the air pollution in the urban city, India based on machine learning models and cross-validation. J. Atmos. Chem. 2025, 82, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Wang, K.; Yang, W.; Wang, P.; Ao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qiao, J. Mechanism Model Combined with Deep Learning Models for Accurate Prediction of Indoor Air Pollution in Residential and Commercial Spaces. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 103, 112008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Chen, D.; Wang, P.; Wang, W.; Shen, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, M. Predicting On-Road Air Pollution Coupling Street View Images and Machine Learning: A Quantitative Analysis of the Optimal Strategy. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 3582–3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deveer, L.; Minet, L. Real-time air quality prediction using traffic videos and machine learning. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2025, 142, 104688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cengil, E. The Power of Machine Learning Methods and PSO in Air Quality Prediction. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binbusayyis, A.; Khan, M.A.; Ahmed A, M.M.; Emmanuel, W.R.S. A deep learning approach for prediction of air quality index in smart city. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Geng, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, D.; Yoo, C.; Liu, H. A novel deep learning framework with variational auto-encoder for indoor air quality prediction. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2024, 18, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruah, A.; Bousiotis, D.; Damayanti, S.; Bigi, A.; Ghermandi, G.; Ghaffarpasand, O.; Harrison, R.M.; Pope, F.D. A novel spatiotemporal prediction approach to fill air pollution data gaps using mobile sensors, machine learning and citizen science techniques. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2024, 7, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Shakil, S.U.P.; Nayan, N.M.; Kashem, M.A.; Uddin, J. Air Pollution Monitoring Using IoT and Machine Learning in the Perspective of Bangladesh. Ann. Emerg. Technol. Comput. (AETiC) 2024, 8, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Nayeem, M.E.H.; Ahmed, M.S.; Tanha, K.A.; Sakib, M.S.A.; Uddin, K.M.M.; Babu, H.M.H. AirNet: Predictive machine learning model for air quality forecasting using web interface. Environ. Syst. Res. 2024, 13, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deo, A.; Khan, S.S.; Doohan, N.V.; Jain, A.; Nighoskar, M.; Dandawate, A. Analysis for Predicting Respiratory Diseases from Air Quality Attributes Using Recurrent Neural Networks and Other Deep Learning Techniques. Ing. Syst. d’Information 2024, 29, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahrari, P.; Khaledi, S.; Keikhosravi, G.; Alavi, S.J. Application of machine learning and deep learning techniques in modeling the associations between air pollution and meteorological parameters in urban areas of Tehran metropolis. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Sharma, R. Enhancing Air Pollution Monitoring and Prediction using African Vulture Optimization Algorithm with Machine Learning Model on Internet of Things Environment. J. Intell. Syst. Internet Things 2024, 13, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, P.S.G.; Puthussery, J.V.; Mao, Y.; Salana, S.; Nguyen, T.H.; Newell, T.; Verma, V. Influence of human activities and occupancy on the emission of indoor particles from respiratory and nonrespiratory sources. ACS ES&T Air 2024, 1, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, T.M.T.; Cai, J.; Molla, A.H.; Kurniawan, T.A.; Kong, S.S.-K. Evaluation of Machine Learning Models in Air Pollution Prediction for a Case Study of Macau as an Effort to Comply with UN Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, M.W.; Saritha; Kallapu, B.; Hejamadi, R.M.; Jijo, J.; Ramesh, R.K.; Aslam, M.; Jilani, S.F. Exploring the Influence of Tropical Cyclones on Regional Air Quality Using Multimodal Deep Learning Techniques. Sensors 2024, 24, 6983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Son, J.Y.; Junger, W.; Bell, M.L. Exposure to particulate matter and ozone, locations of regulatory monitors, and sociodemographic disparities in the city of Rio de Janeiro: Based on local air pollution estimates generated from machine learning models. Atmos. Environ. 2024, 322, 120374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasudevan, P.; Ekambaram, C. HYAQP: A Hybrid Meta-Heuristic Optimization Model for Air Quality Prediction Using Unsupervised Machine Learning Paradigms. Int. Arab J. Inf. Technol. 2024, 21, 953–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folifack Signing, V.R.; Taamté, J.M.; Noube, M.K.; Yerima, A.H.; Azzopardi, J.; Tchuente Siaka, Y.F.; Saïdou. IoT-based monitoring system and air quality prediction using machine learning for a healthy environment in Cameroon. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaberi, A.H.M.; Hamzah, A.; Dzulkifly, S.; Li, W.S.; Gaus, Y.F.A. Machine Learning Approaches for Predicting Occupancy Patterns and its Influence on Indoor Air Quality in Office Environments. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2024, 15, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareba, M.; Cogiel, S.; Danek, T.; Weglinska, E. Machine Learning Techniques for Spatio-Temporal Air Pollution Prediction to Drive Sustainable Urban Development in the Era of Energy and Data Transformation. Energies 2024, 17, 2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathnayake, L.R.S.D.; Sakura, G.B.; Weerasekara, N.A.; Sandaruwan, P.D. Machine Learning-based Calibration Approach for Low-cost Air Pollution Sensors MQ-7 and MQ-131. Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 2024, 23, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anggraini, T.S.; Irie, H.; Sakti, A.D.; Wikantika, K. Machine learning-based global air quality index development using remote sensing and ground-based stations. Environ. Adv. 2024, 15, 100456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aram, S.A.; Nketiah, E.A.; Saalidong, B.M.; Wang, H.; Afitiri, A.-R.; Akoto, A.B.; Lartey, P.O. Machine learning-based prediction of air quality index and air quality grade: A comparative analysis. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 21, 1345–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthar, G.; Kaul, N.; Khandelwal, S.; Singh, S. Predicting land surface temperature and examining its relationship with air pollution and urban parameters in Bengaluru: A machine learning approach. Urban Clim. 2024, 53, 101830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Photsathian, T.; Suttikul, T.; Tangsrirat, W. Prediction of air pollution from power generation using machine learning. EUREKA Phys. Eng. 2024, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhope, T.S.; Shaikh, A.; Simunic, D.; Patil, P.P.; Wagh, K.S.; Wagh, S.K. Real Time Air Quality Surveillance & Forecasting System (Rtaqsfs) in Pune City Using Machine Learning-Based Predictive Model. Proc. Eng. 2024, 6, 505–512. [Google Scholar]

- Topalović, D.B.; Tasić, V.M.; Petrović, J.S.S.; Vlahović, J.L.; Radenković, M.B.; Smičiklas, I.D. Unveiling the potential of a novel portable air quality platform for assessment of fine and coarse particulate matter: In-field testing, calibration, and machine learning insights. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerges, F.; Llaguno-Munitxa, M.; Zondlo, M.A.; Boufadel, M.C.; Bou-Zeid, E. Weather and the City: Machine learning for predicting and attributing fine scale air quality to meteorological and urban determinants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 6313–6325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morapedi, T.D.; Obagbuwa, I.C. Air pollution particulate matter (PM2.5) prediction in South African cities using machine learning techniques. Front. Artif. Intell. 2023, 6, 1230087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, A.; Garuda, S.; Vogt, U.; Yang, B. Air pollution prediction using machine learning techniques—An approach to replace existing monitoring stations with virtual monitoring stations. Atmos. Environ. 2023, 310, 119987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; Fahad, S.; Han, M.S.; Naeem, M.R.; Room, S. Air quality index prediction via multi-task machine learning technique: Spatial analysis for human capital and intensive air quality monitoring stations. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2023, 16, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindra, K.; Bahadur, S.S.; Katoch, V.; Bhardwaj, S.; Kaur-Sidhu, M.; Gupta, M.; Mor, S. Application of machine learning approaches to predict the impact of ambient air pollution on outpatient visits for acute respiratory infections. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, 159509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Xu, X.; Ma, X.; Wang, Z.; You, Q.; Shan, W.; Yang, Y.; Bo, X.; Yin, C. Application of machine learning to predict hospital visits for respiratory diseases using meteorological and air pollution factors in Linyi, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 88431–88443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhang, Q.; Peng, Y.; Guan, X.; Li, L.; Mu, J.; Wang, X.; Yin, X.; Wang, Q. Contributions of various driving factors to air pollution events: Interpretability analysis from Machine learning perspective. Environ. Int. 2023, 173, 107861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, R.; Amin, A.; Khan, M.A.; Asif, M.D.A.; Anwar, Z.; Bashir, M.J. Impact of Green Energy Transportation Systems on Urban Air Quality: A predictive analysis using spatiotemporal deep learning techniques. Energies 2023, 16, 6087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alolayan, M.A.; Almutairi, A.; Aladwani, S.M.; Alkhamees, S. Investigating major sources of air pollution and improving spatiotemporal forecast accuracy using supervised machine learning and a proxy. J. Eng. Res. 2023, 11, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, M.; Merayo, M.G.; Núñez, M. Machine learning algorithms to forecast air quality: A survey. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 10031–10066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mogaraju, J.K. Machine learning strengthened prediction of tracheal, bronchus, and lung cancer deaths due to air pollution. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 100539–100551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamei, M.; Ali, M.; Jun, C.; Bateni, S.M.; Karbasi, M.; Farooque, A.A.; Yaseen, Z.M. Multi-step ahead hourly forecasting of air quality indices in Australia: Application of an optimal time-varying decomposition-based ensemble deep learning algorithm. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2023, 14, 101752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanalakshmi, M.; Radha, V. Novel Regression and Least Square Support Vector Machine Learning Technique for Air Pollution Forecasting. Int. J. Eng. Trends Technol. 2023, 71, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Li, J.; Sulaiman, R.; Alotaibi, B.S.; Elattar, S.; Abuhussain, M. Air Quality Prediction and Multi-Task Offloading based on Deep Learning Methods in Edge Computing. J. Grid Comput. 2023, 21, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devasekhar, V.; Natarajan, P. Prediction of air quality and pollution using statistical methods and machine learning techniques. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2023, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abirami, S.; Chitra, P. Probabilistic air quality forecasting using deep learning spatial–temporal neural network. GeoInformatica 2023, 27, 199–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Baek, K.; So, H. Rapid monitoring of indoor air quality for efficient HVAC systems using fully convolutional network deep learning model. Build. Environ. 2023, 234, 110191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Tian, H.; Luo, L.; Liu, S.; Bai, X.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, K.; Lin, S.; Zhao, S.; Guo, Z.; et al. Understanding and revealing the intrinsic impacts of the COVID-19 lockdown on air quality and public health in North China using machine learning. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 857, 159339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Cai, W.; Tao, Y.; Sun, Q.C.; Wong, P.P.Y.; Huang, X.; Liu, Y. Unpacking the inter- and intra-urban differences of the association between health and exposure to heat and air quality in Australia using global and local machine learning models. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 871, 162005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Graham, D.J.; Stettler, M.E.J. Using explainable machine learning to interpret the effects of policies on air pollution: COVID-19 lockdown in london. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 18271–18281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorek-Hamer, M.; Von Pohle, M.; Sahasrabhojanee, A.; Asanjan, A.A.; Deardorff, E.; Suel, E.; Lingenfelter, V.; Das, K.; Oza, N.C.; Ezzati, M.; et al. A deep learning approach for meter-scale air quality estimation in urban environments using very high-spatial-resolution satellite imagery. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.; Sharma, S.; Chowdhury, K.R.; Sharma, P. A novel seasonal index–based machine learning approach for air pollution forecasting. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agibayeva, A.; Khalikhan, R.; Guney, M.; Karaca, F.; Torezhan, A.; Avcu, E. An Air Quality Modeling and Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALY) Risk Assessment Case Study: Comparing Statistical and Machine Learning Approaches for PM2.5 Forecasting. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazmi, A.; Rakha, H. Assessing and validating the ability of machine learning to handle unrefined particle air pollution mobile monitoring data randomly, spatially, and spatiotemporally. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partheeban, P.; Balamurali, R.; Elamparithi, P.N.; Rohith, K.; Gupta, R.; Somasundaram, K. Deep Learning Models to Predict COVID-19 Cases in India Using Air Pollution and Meteorological Data. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2022, 21, 1171–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Najjar, D.; Al-Najjar, H.; Al-Rousan, N.; Assous, H.F. Developing machine learning techniques to investigate the impact of air quality indices on tadawul exchange index. Complexity 2022, 2022, 4079524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baqer, N.S.; Albahri, A.S.; Mohammed, H.A.; Zaidan, A.A.; Amjed, R.A.; Al-Bakry, A.M.; Albahri, O.S.; Alsattar, H.A.; Alnoor, A.; Alamoodi, A.H.; et al. Indoor air quality pollutants predicting approach using unified labelling process-based multi-criteria decision making and machine learning techniques. Telecommun. Syst. 2022, 81, 591–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthivel, S.; Chidambaranathan, M. Machine learning approaches used for air quality forecast: A review. Rev. d’Intelligence Artif. 2022, 36, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]