Abstract

Bilevel modelling has been widely applied for the identification of genetic perturbations in metabolic engineering. However, most current approaches are based on a biased assumption that mutant strains always grow optimally. In addition, they are developed based on production rates, which may not meet yield requirements imposed on a production strain. This paper propose to design strains via multiobjective bilevel models that account for the tradeoff between cell growth and metabolic adjustments from the wild type strain. The proposed modelling frameworks can be used to identify design strategies that maximise rates and/or yields of target products, termed rate-based and yield-based modelling, respectively. We demonstrate, through in silico production of important chemicals in Escherichia coli, that our modelling approaches can generate growth-coupled designs in terms of rate and/or yield, and yield-based modelling identifies design strategies consistent with existing experimental studies as well as suggesting novel designs, thereby holding great promise for selecting targets for high-performance strain design. An important finding from this work that a growth rate coupled design is not necessarily growth yield coupled and vice versa suggests that growth-coupled designs should be analysed in both rate and yield spaces to determine their theoretical feasibility.

1. Introduction

Microbial metabolic engineering has achieved great success in using microbes as platforms to produce a variety of industrially relevant high-value biochemicals [1,2]. In metabolic engineering of a host microorganism, key steps involve a systematic understanding of the machinery of the host metabolic network and a rational redesign of the network to increase fluxes toward the pathway of target biochemicals. With the availability of large amounts of multi-omics data and the advance of data integration and network reconstruction techniques, well-curated genome-scale metabolic (GEM) models have been created for a large number of well studied microorganisms [3,4]. This significantly improves our knowledge of microbial metabolism and enables better predictions, such as cell growth and the production capability of biochemicals of interest.

Bilevel modelling has been popularly used in strain design algorithms for identifying manipulation targets in metabolic networks to achieve high production goals. It is built on reconstructed GEM models by formulating strain design as bilevel optimisation problems where the outer level pursues production maximisation, whereas the inner level simulates an assumed cellular objective to potentially achieve by cells [5,6]. This kind of modelling is biased because the assumed objective may be biologically incorrect, particularly in cases where mutants appear to have Pareto-optimal metabolism [7], i.e., engineered strains tend to strike a tradeoff among multiple objectives. Another limitation of this approach is that it focuses on production rates, and product yields have rarely been explored in this framework.

Despite that, progress has been made over the years. A study [8] implemented a bilevel framework, known as OptKnock, where a reaction knockout is considered to carry no flux. By using binary variables to represent the state of reactions and assuming mutant strains always grow optimally, OptKnock is able to identify the best combination of knockout targets for biochemical production [8]. OptKnock has been a baseline for other computational strain design tools since its establishment. An OptKnock derivative, RobustKnock, was proposed to avoid zero production caused by competing pathways [9]. Another OptKnock variant, OptReg, explored the idea of gene up/down regulation for metabolic engineering [10]. Later, OptORF extended the framework of OptKnock and OptReg to additionally account for transcriptional regulatory networks in search of regulatory perturbations for high bio-production [11]. Addition of heterologous pathways was investigated in OptStrain [12] and OptSimStrain [13]. OptForce [14] makes improvements on strain design via a two-step procedure. It first classifies reactions into different groups by comparing the flux distribution between the wide type strain and a desired overproduction mutant, then it uses bilevel modelling to identify the smallest number of interventions [14]. This approach has been very effective in many applications, particularly when there are sufficient flux measurements of the wide type. The framework of OptKnock has been further investigated in recent studies [15,16,17,18], leading to effective tools for growth-coupled design strategies [19].

There are also some studies that aim to remove the biased assumption in the above bilevel modelling frameworks. Minimum-cut-set (MCS)-based approaches have also been studied for computational strain design [20,21]. MCS methods were originally proposed for identifying a minimal number of reaction removals that can demolish a metabolic task [22]. This type of method has been applied to identify genetic interventions for biochemical overproduction [21]. MCS methods rely on enumeration of elementary modes of a given metabolic network. They can be computationally demanding for GEM models, but continued advance of efficient enumeration techniques helps alleviate this limitation [21]. MCS methods have a significant advantage over OptKnock-based tools, as they can design strains to meet yield requirements [21,23]. However, the resulting manipulation targets could be tens of reactions, which may pose challenges to experimental implementations.

Another research direction in computational strain design is to speed up the identification of the best design strategies. Exact solvers for OptKnock-based modelling can be computationally prohibitive for large GEM models and a high number of allowed knockouts [24]. In view of this, a wide range of approximate optimisation approaches have been proposed, including genetic algorithms [25,26,27], swarm intelligence [28,29], local search [30], or other heuristic methods [31,32,33].

In this work, we revisited bilevel modelling for strain design. We hypothesised that strain design is a multi-objective task that requires balancing growth and metabolic perturbations, and proper incorporation of the tradeoff into bilevel modelling not only alleviates biases in assumptions of cell metabolism but also improves design performance. We also made a hypothesis that optimising product yields should be different from optimising production rates. As a result, a multiobjective bilevel modelling framework, called M-OptKnock, was proposed to account for the tradeoff between metabolic adjustments and cell growth in mutants, alleviating the strong biased assumption that mutants grow optimally in OptKnock-based frameworks. We also proposed yield-based modelling, termed OptYield, to fill the gap that rate-based bilevel modelling neglects high product-yield design strategies. We showed, through in silico studies on E. coli production of several important biochemicals, that multiobjective modelling enhances the identification of growth rate coupled (GRC) or growth yield coupled (GYC) strain designs. It is also demonstrated that yield-based modelling provides novel design strategies missed by rate-based modelling, and that GRC strain design is not necessarily GYC, and vice versa. Given the fact different modelling frameworks have their own advantages as well as drawbacks, we suggest to use different modelling frameworks all together for strain design and make decisions based on a pool of design strategies.

2. Methods

We start with a brief introduction of flux balance analysis, a popular mathematical approach to estimate flux configurations in metabolic networks, followed by presenting one of the earliest strain design approaches, OptKnock, upon which our approaches build to enhance design performances. Then, we present our proposal of a multi-objective formulation of OptKnock that accounts for the tradeoff between cellular growth and metabolic adjustments experienced by cells if imposed with modifications to cell metabolism. We then describe our proposal of yield-based bilevel modelling, i.e., OptYield, which focuses on identifying design strategies to maximise product yields over production rates. Finally, we present M-OptYield, an extension of OptYield similar to M-OptKnock that aims to design strains with balanced objectives.

2.1. Flux Balance Analysis

A metabolic network of m metabolites and n reactions has a stoichiometric matrix S that is formed by stoichiometric coefficients of the reactions. Let J be a set of n reactions and the reaction rate of , represents the concentration change rates of the m metabolites. FBA aims at optimising a linear biological objective when the system is at steady state (i.e., the concentration change rate is zero for all the metabolites), and v is subject to thermodynamic constraints:

where and are the lower and upper flux bounds of reaction j, respectively. c is a weight vector specifying the degree of importance of each reaction to the biological objective.

2.2. Bilevel Model: OptKnock

Established by the work [8], OptKnock is one of the early strain design tools for the identification of genetic targets for metabolic engineering. OptKnock adopts a bilevel framework, where the upper level maximises the production rate () of a chemical of interest, whereas the lower level is an FBA assuming optimal growth rate (). OptKnock takes the following form:

where , and indicates reaction j is inactive () if and active otherwise. K is the maximum allowable number of genetic knockouts. J contains all the reactions in a GEM model, and is a subset of J containing only candidate reactions for knockout. is the minimum threshold of growth. Reference [8] made use of strong duality theory to convert the bilevel problem into a standard MILP for exact solvers.

2.3. Proposed Modelling

2.3.1. M-OptKnock

It is reported that mutant strains prefers a flux redistribution that has the minimum metabolic adjustment from the wild type [34]. Metabolic adjustment and growth rate in mutants are somehow in conflict with each other. For example, a knockout strategy rendering a high production rate at an optimal growth rate of the mutant may require a significantly large metabolic adjustment. Therefore, we propose multiobjective modelling of mutants to deal with the tradeoff between cell growth and metabolic adjustments simultaneously. Consequently, M-OptKnock, a multiobjective OptKnock considering metabolic adjustments, is introduced to select knockout targets for target overproduction, as shown below:

where is the flux vector of the wild type and is the wild type growth rate. Note that, for linearisation purposes, metabolic adjustment uses the 1-norm distance rather than 2-norm distance in this work. The bi-objectivity of the inner level is resolved through scalarisation. To be specific, (3c) is cast into a scalar objective , where ( is recommended in this paper based on preliminary studies) represents a specific decision to balance the tradeoff between growth rate and metabolic adjustment in mutants. The scalarised objective function is further linearised with auxiliary variables and constraints. At the end, we have a bilevel binary linear programming problem that can be transformed into a solvable MILP using strong duality theory (Appendix A.1).

2.3.2. OptYield

In contrast to production rate (or productivity), yield measures the conversion efficiency from substrates to products. Product yield is a crucial feature in bioprocesses [24]. However, it is rarely considered in current computational strain design studies, and to our best knowledge, there is no work on identifying design strategies for optimal product yield. Here, we propose OptYield, a bilevel framework, to bridge this gap. OptYield is conceptually similar to OptKnock, except that the upper and lower levels are stated as product yield and growth yield maximisation, respectively, as mathematically described below:

where is the uptake rate of the substrate in question. OptYield is a nonlinear bilevel model and has to be reformulated in order to be solved efficiently. We applied some linearisation techniques and finally recast the model to a globally solvable MILP (Appendix A.2).

2.3.3. M-OptYield

OptYield can be extended to account for metabolic adjustments in a similar manner to M-OptKnock. Therefore, M-OptYield is modelled as:

Similar to M-OptKnock, the above mathematical model can be transformed to an MILP by fixing the tradeoff between growth yield and product yield to a certain level (same value as in M-OptKnock) and using linearisation techniques mentioned in OptYield.

2.4. Model Reduction and Candidate Selection

GEM models usually have at least thousands of metabolites and reactions, leading to considerably large stoichiometric matrices S involved in our bilevel modelling framework. The truncation of these models, together with rigorous selection of knockout candidates, has great computational benefits. GEM models can be significantly simplified by compressing linear reactions and removing dead end reactions (those carrying zero fluxes). Likewise, many reactions can be excluded from consideration with a priori knowledge that, for example, they are vital for cell growth or their knockout is not likely to improve target production. In this work, we focus on Escherichia coli (E. coli) production of several industrially relevant bioproducts. We chose the latest GEM iML1515 [35], which is the most comprehensive reconstruction of E. coli to date, downloaded from BIGG Models (http://bigg.ucsd.edu/), to investigate the effectiveness of the proposed modelling approaches. The iML1515 model has been frequently used to study computational approaches [17] with varied levels of success. It inherently provides values for all the parameters required in this work. In particular, we used a maximum uptake rate of 20 mmol/gDW/h for both glucose and oxygen, and other parameter settings remained the same as the original iML1515. We followed the model reduction procedure [30] and candidate selection procedure [24], resulting in a candidate set of 150∼300 reactions for different target products from the GEM iML1515.

2.5. Computational Implementation

First of all, all the bilevel models were transformed into MILPs using corresponding reformulation techniques (see Appendix A). Then, the resulting MILPs were implemented in MATLAB 2018b to be compatible with the Cobra Toolbox 3.0 [36] where we carried out simulations. All the MILPs were solved by Gurobi 8.5 [37] with both Heuristics and MIPFocus set to 1 as suggested by reference [38]. A time limit of 30,000 s was applied to each MILP while performing computations on Ubuntu 16.04 LTS with an Intel® CoreTM i5 Quad Core processor (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

3. Results

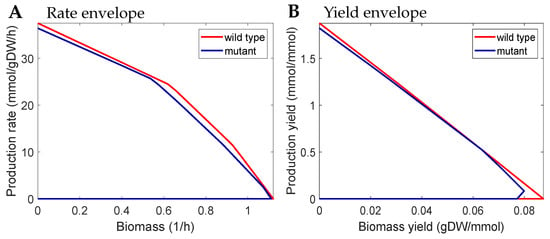

We conducted empirical studies on the effectiveness of the proposed approaches on the model organism E. coli for the production of several important biochemicals, including acetate, ethanol, and succinate. We used the most comprehensive reconstruction of E. coli metabolic networks, iML1515, and data were taken from BIGG Models (http://bigg.ucsd.edu/). In this paper, a design strategy is presented in the form of a set of abbreviated reaction names derived from iML1515, where, for convenience, abbreviations and associated reaction names are also provided in Supplementary Note Table S2. For example, a design strategy of {A, B, C} means that reactions A, B, and C are simultaneously knocked out for certain chemical production. We analysed the approaches from multiple aspects, including strains’ production performance with respect to rates and yields, and visualised production profiles. Particularly, for visualisation, production envelopes were employed. A production envelope describes the lower and upper bounds of target production at all possible growth rates [24]. It is widely used to analyse the potential of a strain design. It is rate based, but it can also be yield based if product yield is plotted against growth yield. For clarity, we call it rate envelope (RE) if it is rate based and yield envelope (YE) if it is yield based. In what follows, REs and YEs are used to assess the proposed modelling methods.

3.1. Multiobjective Modelling of Mutants Helps Achieve Growth-Coupled Design

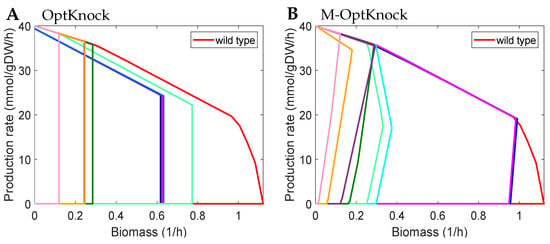

Multiobjective modelling of growth and metabolic adjustments in mutants means that mutants strains are not at optimal growth. Therefore, multiobjective modelling attempts to maximise mutants’ target production at suboptimal growth. In other words, M-OptKnock and M-OptYield identify GRC and GYC strain designs, respectively. This hypothesis is correct for many products; for example, for ethanol production (Figure 1), M-OptKnock overcomes the limitation of OptKnock. It found GRC strain designs by removing all completing pathways. For example, M-OptKnock suggested to maintain pyruvate for ethanol formation by blocking other pyruvate-consuming reactions, such as pyruvate secretion and lactate formation, which were not captured in OptKnock knockout sets. Similarly, some design strategies obtained by OptYield may be not GYC, but M-OptYield overcomes this limitation by identifying only GYC strategies (see ethanol production in Supplementary Note Figure S1). Interestingly, all the GYC strategies by M-OptYield suggested oxygen depletion, which is not included in non-GYC strategies of OptYield. Thus, M-OptYield predicts anaerobic ethanol fermentation well for high yield.

Figure 1.

Rate envelopes of design strategies (in colours other than red) identified by different methods with up to five knockouts for ethanol production. Each colored line represents a design strategy (excluding the red line). Each method calculated 8 best design strategies with 10 evenly spaced values from 0.1 to 0.5, then removed those with a maximum production rate of zero. (A) Design strategies (sets of abbreviated reaction names) of OptKnock represented by coloured lines from left to right: {O2tex, FORtex, XYLI2, TKT1, PGI}, {O2tex, FORtex, FE2tex, TKT2, PGI}, {O2tex, FORtex, FE3tex, TKT2, PGI}, {O2tex, FORtex, TKT2, FBA, TALA}, {FORtex, EDA/EDD, XYLI2, FBA, PGI}, {FORtex, EDA/EDD, XYLI2, PPM, PGI}, {FORtex, FE2tex, EDA/EDD, XYLI2, PGI}, {FORtex, F6PA, EDA/EDD, TALA, FBA}. (B) Design strategies of M-OptKnock represented by coloured lines from left to right: {O2tex, FORtex, FE2tex, FUM, D_LACt2pp}, {O2tex, FORtex, RPE, FUM, D_LACt2pp}, {O2tex, FORtex, FUM, D_LACt2pp, TKT2}, {O2tex, FORtex, D_LACt2pp, PSERT/PSP_L, TKT2}, {O2tex, PGI DHAtpp, PSERT/PSP_L, GLCtex_copy2}, {O2tex, PPM, XYLI2, TKT2, DOXRBCNtpp}, {FORtex, XYLI2, D_LACt2pp, TKT2}, {FORtex, PPC, D_LACt2pp, PSERT/PSP_L, TKT2}. All abbreviated reaction names are derived from the GEM iML1515 model [35] and listed in Supplementary Note Table S2.

Apart from growth coupling, it is interesting to see that multiobjective modelling (though scalarised eventually for easing computation) competes well, achieving similar values, with single-objective modelling in terms of maximum production rate/yield, as indicated by the results displayed in Table 1 and the corresponding production envelopes provided in Supplementary Note Figure S2. In the case that single-objective modelling finds growth-coupled design strategies, multiobjective modelling is not only able to find them but also identifies additional design strategies with interesting REs/YEs (Supplementary Note Figure S2). This gives metabolic engineers broader choices for decision making.

Table 1.

Product yield values of strains designed by four methods with at most five knockouts. Each approach shows the minimal and maximal product yields that it can have while reaching the maximal growth yield.

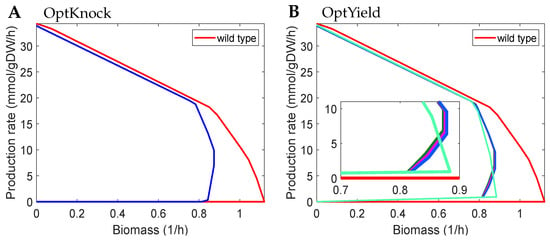

3.2. Yield-Based Modelling Can Identify Design Strategies That Are Different from Rate-Based Modelling

Yield- and rate-based modelling approaches have the same bilevel framework, except our yield-based modelling uses an additional term at both levels. In some cases, the rate- and yield-based modelling approaches identify same design strategies (Supplementary Note Figure S2). In other cases, however, the tiny difference between the two approaches (M-OptKnock and M-OptYield) leads to distinct performances in the identification of high-producing strain designs (Figure 2 and Supplementary Note Figure S3). OptKnock obtained 10 highest production design strategies with the same RE for succinate production, but all of them were very weak GRC (Figure 2A). That is, mutants with a small growth deviation (∼3%) from the optimal growth rate were likely to have zero overproduction of succinate. In contrast, mutants from OptYield in this case were more robust, as there was always an amount of overproduced succinate for living cells, although the amount was small for slow growth. It is also noticed that design strategies from OptYield have slightly different REs. In fact, all the ten solutions by OptKnock have a identical four-knockout subset, i.e., {ACtex, TKT1, FUM, PSERT}, with the fifth knockout being different. OptKnock can easily fail if any of the subsets are in vivo infeasible or difficult to implement. In contrast, the OptYield-based solutions have a diverse distribution of knockouts, with which decision making on the selection of designs can be further conducted. The difference in the RE of mutants between the two modelling approaches increases with the maximum allowable number of knockouts (Supplementary Note Figure S4).

Figure 2.

Rate envelopes of design strategies identified by different methods with at most five knockouts for succinate production with constrained growth rate . OptKnock identified only one, whereas OptYield identified four unique design strategies. (A) Design strategy identified by OptKnock in blue: {ACtex, TKT1, FBA, FUM, PSERT/PSP_L}. (B) Design strategy (sets of abbreviated reaction names) of OptYield represented in coloured lines from left to right: {ACtex, TKT1, FUM, ABTA, PSERT/PSP_L}, {ACtex, FE2tex, TKT1, FUM, PSERT/PSP_L}, {ACtex, TKT1, FUM, F6PP, PSERT/PSP_L}, {ACtex, PYRtex, FUM, ICL, PSERT/PSP_L}. All abbreviated reaction names are derived from the GEM iML1515 model [35] and listed in Supplementary Note Table S2.

3.3. GRC Design Strategies Are Not Necessarily GYC, and Vice Versa

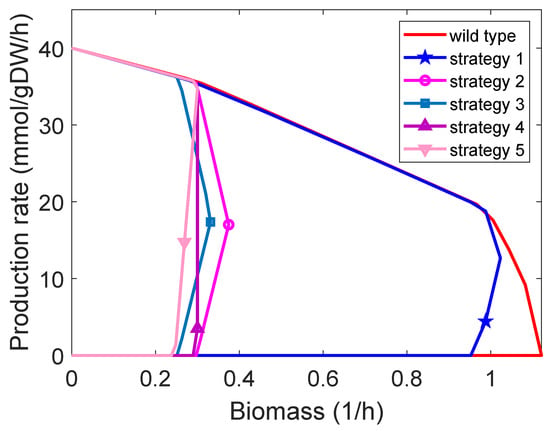

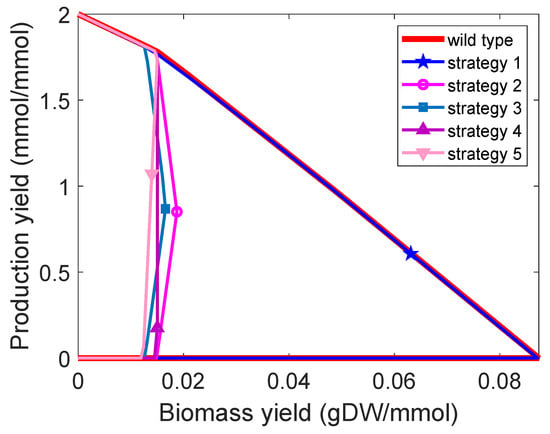

Many computational strain design methods focus on the identification of GRC design strategies. Are GRC design strategies also GYC, and vice versa? Here, we investigate the relationship between them. We found that many design strategies can be GRC and GYC simultaneously (Supplementary Note Figure S5), but there are exceptions. For example, as shown in Table 1, with zero values for growth/product yield, it is noticed that, in the case of acetate production, rate-based modelling (i.e., OptKnock and M-OptKnock) is incapable of generating GYC design strategies. Similar observations are obtained for succinate production. This suggests that rate-based modelling may not achieve GYC strategies. In addition, when at most three knockouts are allowed in M-OptKnock for ethanol production, four of five GRC design strategies (Table 2) are GYC, and the one with a higher growth rate and also a good production rate is not GYC until the biomass is near 1/h (Figure 3 and Figure 4). More GRC design strategies that are not GYC were identified for a higher number of knockouts (Supplementary Note Figure S6). We also noticed that GRC (driven by M-OptKnock) and GYR (driven by M-OptYield) design strategies could share common manipulation targets as well as distinct ones to achieve their intrinsic characteristics, as indicated by a comparison between Table 2 and Table 3 in the case of ethanol production. Interestingly, in the worst case, M-OptYield-derived design strategies tended to have higher minimum production rates of ethanol than M-OptYield, implying that M-OptYield could be an effective approach to generate high-quality design strategies that are both GRC and GYC.

Table 2.

Design strategies (sets of abbreviated reaction names) identified by M-OptKnock with at most three knockouts for ethanol production.

Figure 3.

Rate envelopes of five design strategies (Table 2) identified by M-OptKnock with three knockouts for ethanol production.

Figure 4.

Yield envelopes of five design strategies (Table 2) identified by M-OptKnock with three knockouts for ethanol production.

Table 3.

Design strategies (sets of abbreviated reaction names) identified by M-OptYield with at most three knockouts for ethanol production.

Next, we wondered whether a GYC design strategy can be GRC. We observed that many GYC design strategies are also GRC. However, there do exist a few exceptions. For example, a design strategy identified by M-OptYield is GYC for fumarate overproduction, but it is not GRC at all (Figure 5). This means GYC design strategies are not necessarily GRC. Therefore, we can conclude that design strategies are not always GRC and GYC all the same time. This conclusion is important because when many design strategies can achieve similar GRC phenotypes for target production, investigating their GRC phenotypes may help to identify the best one for implementation.

Figure 5.

Rate and yield envelopes of a strain design by M-OptYiled with a knockout set of {FUM, LGTHL, GLBRAN2, SERD_D} for fumarate production. (A) Yield envelope. (B) Rate envelope. The resulting mutant is (weak) GYC but not GRC.

4. Discussion

Bilevel modelling of genome-scale metabolic networks has shown to be an effective approach to identify genetic modification targets for metabolic engineering [8,9]. When this approach is used, strain design is largely dependent of specific bilevel frameworks, and different frameworks can lead to distinct strain performances. In this paper, we have revisited the bilevel modelling frameworks for predicting genetic knockouts. We argued that the tradeoff observed in previous studies [34] between cellular growth and metabolic adjustments could improve strain design if it is incorporated into computational modelling. With this in mind, a multiobjective modelling framework considering this tradeoff has therefore been introduced, called M-OptKnock. In addition, in view of the fact that existing computational design approaches focus mainly on production rates and may not satisfy industrial yield requirements, we also have proposed OptYield, a yield-based bilevel framework, to achieve high production yield. Similar to M-OptKnock, metabolic adjustments were also incorporated into OptYield, forming another multiobjective model M-OptYield. Our empirical studies on E. coli production of several industrially relevant products have showed that models embedded with the tradeoff between growth and metabolic adjustments could improve strain design, i.e., they are more likely to find growth-coupled designs than those without tradeoff embedded. In addition, we also concluded an interesting finding that a growth-coupled design in pursuit of production rates is not necessarily a growth-coupled one for product yields, and vice versa, in spite of similar modelling solutions from a mathematical point of view.

While all the bilevel models in this work have been effective in identifying rational strain designs, we recognise that each model has its own strengths. OptKnock seems to always achieve the highest upper bound of production rate at optimal growth, and M-OptKnock prefers GRC design strategies, whereas the upper bound of production rate is no larger than that of OptKnock. OptYield is yield based, and therefore the product yield of mutants by OptYield is the highest. M-OptYield avoids non-GYC design strategies, but the yield is not larger than OptYield. Therefore, it is a good idea to use all these models together to obtain a pool of design strategies and select the best one with additional preferences.

The proposed approaches successfully predicted several reaction deletions that were verified already by existing experimental studies for ethanol production. To be specific, M-OptYield suggested oxygen depletion to improve ethanol production, agreeing well with the fact that ethanol fermentation is a preferred strategy in anaerobic conditions. The reaction LDH_D, catalysed by lactate dehydrogenase, is a common knockout target in experimental data [39]. This important manipulation was captured by M-OptYield. Deletion of phosphoglucose isomerase (PGI), predicted by M-OptYield, was also found effective to improve ethanol production in the study [40]. M-OptYield suggested to divert acetate to ethanol by removing the acetate biosynthetic pathway through deletion of ACtex. This was found to be in good agreement with reference [41]. For succinate production, OptYield also suggested knockout of ACtex to channel flux into the Kreb cycle, which was experimentally confirmed in the succinate-producing study [42]. In addition, the deactivation of FUM, through fumarase isozymes fumA and fumB genes, is a frequent manipulation suggested by Opt-Yield. Indeed, this modification was found effective to increase succinate from pyruvate in the experimental study [43]. The agreement with experimental data mentioned above implies that the proposed approaches have great potential to aid metabolic engineering.

We noticed that some knockout targets suggested by the proposed approaches were also recommended by other bilevel methods like OptForce [14] and unbiased methods like MCS [21]. For example, in the case of succinate production, the knockout of ACtex and FUM was predicted by both OptYield and OptForce. For ethanol production, both M-OptKnock and MCS identified PPC, PGI, and EDA as potential knockout targets, showing great agreement in rational design. However, we would like to stress that our approaches cannot be directly compared with OptForce and MCS due to the inherent difference between the problems addressed by these methods. OptForce aims to identify a combination of different kinds of genetic modifications for biochemical production, including gene up/down-regulation and knockout. In contrast, our approaches just focus on knockouts as the only type of manipulation to metabolic networks. On the other hand, our approaches are different from MCS, in that the former optimises production rates/yields directly within a limited number of knockouts. However, the latter minimises the number of knockouts such that the requirements of predefined rates or yields are met. For these reasons, it is challenging to quantitatively compare these methods, aside from the similarity analysis of proposed knockout targets.

All approaches considered in this paper have a parameter K to limit the number of manipulations that can be realised in experimental implementation. We wondered about the scalability of the approaches with K and how K interacts with another parameter to affect production capabilities; thus, we tested several K values for two growth conditions, i.e., and . The results presented in Table 4 and Table 5 show that all the approaches scale well with K, i.e., minimum/maximum production rates increase monotonically with K, regardless of . It is noticed that, for a larger value, finding growth-coupled designs (i.e., minimum production above zero) becomes more difficult. Despite that, the proposed approaches found growth-coupled designs with larger K values, showing better performance than OptKnock, which could not find any growth-coupled designs across all tested K settings in two growth requirements. In addition, we analysed how different growth media affect the performance of the proposed approaches (see Supplementary Note Table S1). It was noticed that the approaches are quite robust in growth media with glycerol or xylose as the sole carbon source. All proposed approaches identified growth-coupled designs for ethanol and acetate production, whereas OptKnock failed to do so for ethanol production from xylose. This further enhanced our conclusion that the proposed modelling frameworks improved strain design.

Table 4.

Comparison of succinate production capabilities (min~max production rates in mmol/gDW/h) of best design strategies identified by different approaches with a growth rate over 0.1.

Table 5.

Comparison of succinate production capabilities (min~max production rates in mmol/gDW/h) of best design strategies identified by different approaches with a growth rate over 0.5.

This work has some limitations. First, the tradeoff considered here only covers cellular growth and metabolic adjustments. Other metabolic objectives observed in the literature [7], including energy optimality and enzymatic efficiency, may also play a critical role in shaping the metabolism of production strains. It requires significant effort to have them included in our current modelling frameworks. Second, our modelling frameworks may not produce designs that are both GRC and GYC from a single bilevel model. As a result, designs from a single bilevel model may be of little use if both rate and yield requirements are imposed. One remedy to this limitation could be the use of both rate- and yield-based models from which the intersection of designs is identified. This is, however, computationally intensive, as it involves solving multiple large-scale MILPs. It is therefore demanding to develop a novel unified framework that can identify both GRC and GYC design designs simultaneously. This could be however challenging because simultaneous optimisation of rates and yields is a multiobjective problem that requires appropriate formulation of the tradeoff between two parties during modelling. It could also face computational difficulties because the two properties are mathematically different, which may not be possible to take the advantage of (mixed-integer) linear programs to solve efficiently.

Furthermore, all the proposed methods suggest knockouts at a reaction level, but they can be easily applied to modified metabolic networks, where each reaction is only related to a single gene, to identify gene knockouts. For example, recent studies show that a metabolic network can be modified to have a one-to-one mapping between genes and reactions by adding pseudo reactions [44] or by adding each enzyme subunit as a species [45] in the corresponding stoichiometry. Applying the proposed methods to the modified GEM model for gene knockout is straightforward, but this increases computational demands significantly, as the model becomes much larger after modification.

The tradeoff between optimal cell growth and maximal target production is very helpful for decision makers to choose design strategies. Bilevel frameworks are often solved by an exact MILP solver, resulting in a single solution for each MILP. The tradeoff can be achieved by using a number of minimum growth (or ) values in the bilevel models. However, this approach does not always work, as design strategies for different values may have the same RE/PE phenotypes. Approximate solvers, such as a multiobjective genetic algorithm [46], are of great use in this case, but the solutions obtained may be locally optimal. Therefore, we would like to investigate other types of optimisation approaches, such as Benders decomposition [47], for identifying multiple tradeoff design strategies in a single run in future work.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/a18120786/s1, Figure S1:Yield envelopes of design strategies identified by different methods with up to five knockouts for ethanol production; Figure S2: Rate envelopes of design strategies identified by different methods with up to five knockouts for ethanol production; Figure S3: Rate envelopes of four design strategies identified by different methods with five knockouts for succinate production; Figure S4: Rate envelopes of design strategies identified by different methods with at most eight knockouts for succinate production; Figure S5: Rate and yield envelopes of six design strategies identified by M-OptYield with three knockouts for ethanol production; Figure S6: Rate and yield envelopes of five design strategies identified by M-OptKnock with five knockouts for ethanol production; Table S1: Comparison of minimum/maximum production rates (mmol/gDW/h) of best design strategies identified by different approaches in two growth media; Table S2: Reaction name and abbreviations derived from iML1515 and BIGG Database.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.J. and J.L.; methodology, S.J.; software, B.W.; validation, B.W.; formal analysis, B.W.; investigation, B.W.; resources, B.W.; data curation, B.W.; writing—original draft preparation, B.W., S.X., and S.J.; writing—review and editing, B.W., S.J., S.X., and J.L.; visualization, B.W. and S.X.; supervision, SJ; project administration, S.J.; funding acquisition, S.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62376288, 2022HWYQ10), in part by Provincial Natural Science Foundation of Hunan (Grant No. 2024JJ5441), and in part by the High Performance Computing Center of Central South University.

Data Availability Statement

Source code implemented in the MATLAB Cobratoolbox is freely available at https://github.com/chang88ye/Knock-Tools (accessed on 3 December 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GEM | Genome-scale metabolic model |

| MCS | Minimum-cut set |

| GYC | Growth yield coupled |

| GRC | Growth rate coupled |

| MILP | Mixed-integer linear program |

Appendix A. Linear Reformulation of Bilevel Models

Appendix A.1. Linear Reformulation of M-OptKnock

M-OptKnock is modelled as follows:

The lower level has two objectives to be optimised, which represent a tradeoff between cell growth and metabolic adjustments. The objective vector (A1c) is scalarised into a single objective function:

where denotes the importance of metabolic adjustments in mutants. should be much smaller than one ( is used in this work), as the metabolic adjustment term is much larger than the growth rate . With the aid of additional constraints, (A2) can be further linearised into:

Therefore, a complete linear bilevel model of M-OptKnock is given as follows:

The linear bilevel model (A5) is recast to a standard mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) problem using the strong duality theory. The resulting MILP is well suited to many modern commercial solvers.

Appendix A.2. Linear Reformulation of OptYield

OptYield is modelled as follows:

In order to always keep the divisions in OptYield legal, a small positive value is added to the denominators in both the upper and lower levels. For simplicity, a value of one is used in this work. Let ; then, holds since takes non-positive flux values in GEM models. Let () and (); OptYield (A6) is reformulated as follows:

where are dual variables for the constraints of the inner level problem. This model is reformulated as the following single-level problem by applying the strong duality theory to the lower-level problem:

where (A8d) are new constraints derived to guarantee the strong duality for the inner level problem. Both and in (A8) are the product of a continuous and a binary variable, and they can be linearised using the Big-M approach. That is, any product where C is a continuous variable and B a binary variable can be cast to a few linear constraints:

where M is sufficiently large to have C included.

Let ; the above linearisation technique results in a standard MILP for OptYield:

References

- Chae, T.U.; Choi, S.Y.; Kim, J.W.; Ko, Y.S.; Lee, S.Y. Recent advances in systems metabolic engineering tools and strategies. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2017, 47, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, P.; Kumar, R.; Karn, S.; Patel, P.; Gosai, H. Recent trends in metabolic engineering for microbial production of value-added natural products. Biochem. Eng. J. 2025, 213, 109537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Z.A.; Lu, J.; Dräger, A.; Miller, P.; Federowicz, S.; Lerman, J.A.; Ebrahim, A.; Palsson, B.N.; Lewis, N.E. BiGG Models: A platform for integrating, standardizing and sharing genome-scale models. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 44, D515–D522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarzi, C.; Zampieri, G.; Sullivan, N.; Angione, C. Emerging methods for genome-scale metabolic modeling of microbial communities. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 35, 533–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, P.; Rocha, M.; Rocha, I. In silico constraint-based strain optimization methods: The quest for optimal cell factories. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2016, 80, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Bi, X.; Liu, Y.; Lv, X.; Li, J.; Du, G.; Liu, L. In silico cell factory design driven by comprehensive genome-scale metabolic models: Development and challenges. Syst. Microbiol. Biomanuf. 2023, 3, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuetz, R.; Zamboni, N.; Zampieri, M.; Heinemann, M.; Sauer, U. Multidimensional optimality of microbial metabolism. Science 2012, 336, 601–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgard, A.P.; Pharkya, P.; Maranas, C.D. Optknock: A bilevel programming framework for identifying gene knockout strategies for microbial strain optimization. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2003, 84, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, N.; Shlomi, T. Predicting metabolic engineering knockout strategies for chemical production: Accounting for competing pathways. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pharkya, P.; Maranas, C.D. An optimization framework for identifying reaction activation/inhibition or elimination candidates for overproduction in microbial systems. Metab. Eng. 2006, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Reed, J.L. OptORF: Optimal metabolic and regulatory perturbations for metabolic engineering of microbial strains. BMC Syst. Biol. 2010, 4, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pharkya, P.; Burgard, A.P.; Maranas, C.D. OptStrain: A computational framework for redesign of microbial production systems. Genome Res. 2004, 14, 2367–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Reed, J.L.; Maravelias, C.T. Large-Scale bi-Level strain design approaches and mixed-integer programming solution techniques. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranganathan, S.; Suthers, P.F.; Maranas, C.D. OptForce: An optimization procedure for identifying all genetic manipulations leading to targeted overproductions. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2010, 6, e1000744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alter, T.B.; Ebert, B.E. Determination of growth-coupling strategies and their underlying principles. BMC Bioinform. 2019, 20, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, K.; Broeken, V.; Hansen, A.S.L.; Sonnenschein, N.; Herrgård, M.J. OptCouple: Joint simulation of gene knockouts, insertions and medium modifications for prediction of growth-coupled strain designs. Metab. Eng. Commun. 2019, 8, e00087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Otero-Muras, I.; Banga, J.R.; Wang, Y.; Kaiser, M.; Krasnogor, N. OptDesign: Identifying optimum design strategies in strain engineering for biochemical production. ACS Synth. Biol. 2022, 11, 1531–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Wang, Y.; Kaiser, M.; Krasnogor, N. NIHBA: A network interdiction approach for metabolic engineering design. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 3482–3492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, P.; Mahadevan, R.; Klamt, S. Systematizing the different notions of growth-coupled product synthesis and a single framework for computing corresponding strain designs. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 16, 2100236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apaolaza, I.; Valcarcel, L.V.; Planes, F.J. gMCS: Fast computation of genetic minimal cut sets in large networks. Bioinformatics 2018, 35, 535–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Kamp, A.; Klamt, S. Enumeration of smallest intervention strategies in genome-scale metabolic networks. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2014, 10, e1003378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klamt, S.; Gilles, E.D. Minimal cut sets in biochemical reaction networks. Bioinformatics 2004, 20, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, D.; Eng, T.; Lau, A.K.; Sasaki, Y.; Wang, B.; Chen, Y.; Prahl, J.P.; Singan, V.R.; Herbert, R.A.; Liu, Y.; et al. Genome-scale metabolic rewiring improves titers rates and yields of the non-native product indigoidine at scale. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feist, A.M.; Zielinski, D.C.; Orth, J.D.; Schellenberger, J.; Herrgard, M.J.; Palsson, B.N. Model-driven evaluation of the production potential for growth-coupled products of Escherichia coli. Metab. Eng. 2010, 12, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, F.; Sun, R.; Yao, J.; Li, J.; Liu, Q.; Price, N.D.; Liu, C.; Wang, Z. OptRAM: In-silico strain design via integrative regulatory-metabolic network modeling. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2019, 15, e1006835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, K.R.; Rocha, I.; Förster, J.; Nielsen, J. Evolutionary programming as a platform for in silico metabolic engineering. BMC Bioinform. 2005, 6, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briones-Báez, M.F.; Aguilera-Vázquez, L.; Rangel-Valdez, N.; Zuñiga, C.; Martínez-Salazar, A.L.; Gomez-Santillan, C. Pitfalls in metaheuristics solving stoichiometric-based optimization models for metabolic networks. Algorithms 2024, 17, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choon, Y.W.; Mohamad, M.S.; Deris, S.; Chong, C.K.; Omatu, S.; Corchado, J.M. Gene knockout identification using an extension of bees hill flux balance analysis. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 124537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; You, Q.; Zhang, C.; Sun, J.; Liu, L.; Lu, H.; Chen, Q. Advances and applications of machine learning and intelligent optimization algorithms in genome-scale metabolic network models. Syst. Microbiol. Biomanuf. 2023, 3, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lun, D.S.; Rockwell, G.; Guido, N.J.; Baym, M.; Kelner, J.A.; Berger, B.; Galagan, J.E.; Church, G.M. Large-scale identification of genetic design strategies using local search. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2009, 5, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, S.; Wei, L.; Hua, Q. IdealKnock: A framework for efficiently identifying knockout strategies leading to targeted overproduction. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2016, 61, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohno, S.; Shimizu, H.; Furusawa, C. FastPros: Screening of reaction knockout strategies for metabolic engineering. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 981–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, W.; Gao, G.; Fan, X.; Wang, H.; He, S.; Xiang, G.; Yan, X.; Lu, H. Efficient cell factory design by combining meta-heuristic algorithm with enzyme constrained metabolic models. bioRxiv 2025, bioRxiv:12.659423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segrè, D.; Vitkup, D.; Church, G.M. Analysis of optimality in natural and perturbed metabolic networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 15112–15117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monk, J.M.; Lloyd, C.J.; Brunk, E.; Mih, N.; Sastry, A.; King, Z.; Takeuchi, R.; Nomura, W.; Zhang, Z.; Mori, H.; et al. iML1515, a knowledgebase that computes Escherichia coli traits. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 904–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heirendt, L.; Arreckx, S.; Pfau, T.; Mendoza, S.N.; Richelle, A.; Heinken, A.; Haraldsdóttir, H.S.; Wachowiak, J.; Keating, S.M.; Vlasov, V.; et al. Creation and analysis of biochemical constraint-based models: The COBRA Toolbox v3. 0. Nat. Protoc. 2018, 14, 639–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurobi Optimization, L. Gurobi Optimizer Reference Manual, 2018. Available online: https://docs.gurobi.com/projects/optimizer/en/current/index.html (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Egen, D.; Lun, D.S. Truncated branch and bound achieves efficient constraint-based genetic design. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1619–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCloskey, D.; Palsson, B.Ø.; Feist, A.M. Basic and applied uses of genome-scale metabolic network reconstructions of Escherichia coli. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2013, 9, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundara Sekar, B.; Seol, E.; Park, S. Co-production of hydrogen and ethanol from glucose in Escherichia coli by activation of pentose-phosphate pathway through deletion of phosphoglucose isomerase (pgi) and overexpression of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (zwf) and 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (gnd). Biotechnol. Biofuels 2017, 10, 85. [Google Scholar]

- Seol, E.; Ainala, S.K.; Sekar, B.S.; Park, S. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli strains for co-production of hydrogen and ethanol from glucose. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2014, 39, 19323–19330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantama, K.; Zhang, X.; Moore, J.C.; Shanmugam, K.T.; Svoronos, S.; Ingram, L.O. Eliminating side products and increasing succinate yields in engineered strains of Escherichia coli C. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2008, 101, 881–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derbikov, D.; Novikov, A.; Gubanova, T.; Tarutina, M.; Gvilava, I.; Bubnov, D.; Yanenko, A. Aspartic acid synthesis by Escherichia coli strains with deleted fumarase genes as biocatalysts. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2017, 53, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Ji, B.; Mardinoglu, A.; Nielsen, J.; Hua, Q. Logical transformation of genome-scale metabolic models for gene level applications and analysis. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 2324–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Machado, D.; Herrgård, M.J.; Rocha, I. Stoichiometric representation of gene–protein–reaction associations leverages constraint-based analysis from reaction to gene-Level phenotype prediction. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2016, 12, e1005140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patanè, A.; Santoro, A.; Costanza, J.; Carapezza, G.; Nicosia, G. Pareto optimal design for synthetic biology. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2015, 9, 555–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taşkin, Z.C. Benders Decomposition. In Wiley Encyclopedia of Operations Research and Management Science; American Cancer Society: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).