Abstract

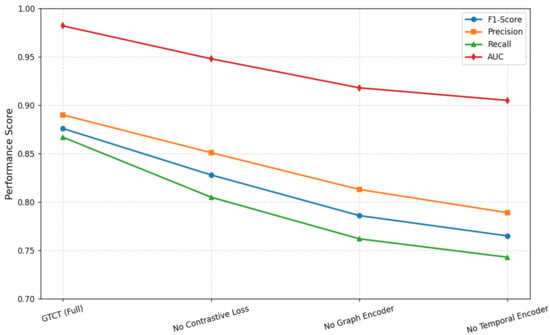

Detection of financial fraud remains a constant challenge due to the dynamic and highly imbalanced nature of transaction data. This paper proposes the Graph-Temporal Contrastive Transformer (GTCT) framework for modeling both structural dependencies between accounts and temporal evolution in transactional behaviors. We propose a model that combines three components: a graph encoder for modeling relationships between accounts, a temporal encoder for learning sequential patterns in transactions, and a contrastive learning objective that enhances the robustness of representations when supervision is limited. To assess the contribution of each component individually, we systematically remove one module at a time. As shown, an exclusion of the contrastive loss resulted in reduced recall and AUC from 0.867 and 0.982 to 0.805 and 0.948, respectively, indicating the importance of self-supervised learning of representations in fraud detection. Similarly, removing the graph encoder decreased the F1-score from 0.876 to 0.786, which confirmed that modeling transaction structures between accounts is crucial for the identification of complex fraud rings. The exclusion of the temporal encoder led to a more drastic drop in recall (0.743) and AUC (0.905), indicating that capturing the temporal dynamics of transactions is relevant. By comparing all variants, the full GTCT model attained the highest accuracy (0.975) and AUC (0.982), thus showing superior robustness in the detection of sophisticated and evolving financial fraud patterns.

1. Introduction

With the highly digitalized financial landscape of the modern era, the number and velocity of electronic payments have multiplied manifold with the surge in popularity of online banking, mobile payment platforms, and virtual financial forums [1,2]. The technological innovation, as convenient and accessible as it has made transactions, has correspondingly placed financial systems under threat from increasingly complex schemes of forgery [3,4,5]. As financial ecosystems grow more interdependent and user trends become more diverse, it has become a significant matter for financial institutions, regulatory authorities, and electronic trade platforms to detect money laundering in a timely and accurate fashion [6,7].

Conventional fraud detection methods, typically relying on rule-based heuristics and conventional machine learning models, are typically not sufficient in such a dynamic environment [3,8]. Conventional methods are often static in their approach and rely heavily on pre-specified patterns or past fraud patterns. They are also struggling to stay abreast of the ever-changing techniques employed by fraudsters, who repeatedly shift methodology to remain one step ahead [4,5]. Furthermore, such systems will more likely exhibit linear, uncorrelated, or temporally separated behaviors that are not indicative of the multi-dimensional, interconnected patterns found in modern financial activities [1,7].

In the real world, financial fraud is rarely an isolated event. Instead, it typically happens through sequences of transactions between many actors—e.g., users, merchants, accounts, and intermediaries—over time. Such activity produces complex, dynamic networks in which malicious intent may only be apparent when considered simultaneously along both axes of time and relation [9,10]. Therefore, effective fraud detection is motivated by models able to understand simultaneously structural patterns of transaction graphs and temporal dynamics characterizing user behavior and transaction sequences [11,12,13].

Rising advancements in graph neural networks (GNNs) and transformer models have opened up new possibilities to capture such complex interactions [14,15]. Transactions have the possibility to be modeled as graphs naturally, where entities such as users, merchants, and accounts are nodes and transaction flows are edges [16,17]. However, fraud detection must also be capable of recording temporal dependencies since fraud always emerges within a sequence of transactions [12,16]. Finally, labeled fraud cases are not common and heavily imbalanced, making supervised learning methods less potent in isolation [18,19].

This requires creating robust, flexible models that can learn from small volumes of marked data, generalize for unforeseen fraud schemes, and continuously evolve to accommodate changes in the transactional behavior of the network [20,21]. To meet these needs, this research explores a novel solution that integrates graph representation learning, temporal modeling, and contrastive self-supervised learning under one transformer-based approach [22,23] to detect hard-to-detect and dynamic fraudulent activities with improved accuracy and scalability.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 introduces the review of related studies about graph-based anomaly detection, temporal modeling, contrastive learning, and fraud detection systems. Section 3 illustrates the proposed Graph-Temporal Contrastive Transformer (GTCT) framework, including the graph representation module, the temporal dual-channel transformer, context transition encoder, and joint contrastive objective. Section 4 describes the experimental setting, datasets, evaluation metrics, baseline models, and implementation details. It analyzes the empirical results, with ablation studies that identify the contribution of each component in GTCT, provides discussions on model interpretability, offers practical implications for real-world financial fraud detection, and discusses possible deployment considerations. Lastly, Section 5 concludes this paper with identified future research directions.

2. Literature

Graph-based and temporal modeling approaches are central to modern fraud and anomaly detection as transactional data inherently contain both relational interac-tions and sequential behavioral patterns. Mubalaike and Adali [24] presented an early deep learning–based framework for intelligent financial fraud detection, demonstrat-ing that neural models can automatically extract discriminative features from raw transactional data and outperform traditional machine-learning baselines. Though not incorporating graph structures or temporal dependency modeling, their approach establishes an important foundation for end-to-end fraud detection, motivating a shift toward more expressive architectures that jointly capture both structural and temporal behavior, such as graph-temporal models and contrastive learning approaches leveraged in GTCT.

Building on this direction, graph-based methods explicitly model relational connections among accounts, merchants, and transactions. UzADL, proposed by Ugli Olimov et al. [25], utilizes an unsupervised graph learning framework using the Laplacian for anomaly detection and localization tasks. By constructing a graph representation of industrial data and performing spectral analysis on the graph, UzADL identifies anomalies through distortions in graph topology. While not targeted at financial fraud explicitly, demonstrating the way in which structural inconsistencies can reveal abnormal behavior provides conceptual grounding for graph-based reasoning in transactional fraud settings.

Cheng et al. [26] presented a spatial-temporal GNN for fraud detection and showed that incorporating both spatial and temporal attention improves detection performance. Their results clearly indicate that relational fraud signals often manifest only when structural dependencies and temporal dynamics are modeled jointly—strongly motivating hybrid graph-temporal architectures such as that proposed in this study. Likewise, Lu et al. [27] developed an AHIN-based fraud detection model for health-insurance data with hierarchical attention. Their efforts confirm the benefits of heterogeneous graph modeling: different node and edge types provide richer relational context, and indeed, there are close analogies between merchants, accounts, and terminals in financial ecosystems. Luo and Zhang [28] combined temporal behavioral profiling and transaction-network topology to analyze financial credit fraud and showed that fraudulent behavior is often reflected not only in suspicious structural linkages but also in subtle temporal drifts. Zioviris et al. [29] go one step further and demonstrate that long-range behavioral patterns are crucially important to distinguish fraudulent from valid users, which again underlines the importance of sequential modeling—that is, one of the key ingredients of GTCT.

Temporal modeling from other domains also informs scalable handling of long-range dependencies. Zhao et al. [30] introduced the T-GCN for traffic prediction by combining GCNs with GRUs. Though developed for transportation networks, T-GCN well illustrates how temporal graph convolution may capture the evolving dynamics on dynamic graphs, thereby providing valuable insight for financial fraud detection. Zhou et al. [31], meanwhile, proposed the Informer architecture, addressing classical Transformer limitations on long sequences using ProbSparse self-attention and memory-efficient mechanisms. The ability of Informer to learn long-range temporal dependencies at scale provides foundational motivation for using temporal Transformers within GTCT. Finally, Deng et al. [32] adapted transformer architectures to real-time fraud detection in cloud-streaming environments, showing that Transformers outperform traditional RNNs when modeling irregular and non-stationary long-range behavioral patterns typical of financial fraud.

Self-supervised contrastive learning has also emerged as a powerful paradigm for label-efficient representation learning. You et al. [33] introduced a pioneering graph contrastive learning framework based on graph augmentations, showing that contrastive pretraining enhances graph representation robustness under limited labeled data—a condition common in fraud detection. Kong et al. [34] extended contrastive learning to federated anomaly detection on distributed graphs, which highlights its suitability for privacy-preserving financial ecosystems involving multiple institutions. Darban et al. [35] developed CARLA, a contrastive framework for time-series anomaly detection, showing that the contrastive augmentation improves the detection of rare temporal anomalies. Zhao et al. [36] proposed a dynamic GNN with self-distillation for multivariate anomaly detection, further emphasizing the importance of combining graph dynamics with temporal contrastive signals.

Most relevantly, Wang et al. [37] proposed the temporal heterogeneous graph contrastive learning framework for credit-card fraud detection by combining heterogeneous graph structures with temporal augmentations to capture evolving fraud behaviors. This has close alignment with the goals of GTCT, but also very clear architectural distinctions, such as our sequential graph → temporal pipeline and joint graph–temporal contrastive objectives. Meanwhile, Zheng et al. [38] explored interpretable contrastive learning for anomaly detection, showing that the contrastive models can remain transparent, an important implication for practical financial deployment and a potential future extension of GTCT. To further elucidate the novelty of GTCT, it is important to distinguish it from previous unified graph-temporal-contrastive models such as GCT-Net. While GCT-Net adopts a dual-branch architecture that processes graph and temporal features in parallel before concatenation, GTCT follows a sequential Graph → Temporal design whereby graph-refined embeddings feed into a dual-channel temporal Transformer. GTCT introduces a Context Transition Encoder to model relational drift across time, absent in GCT-Net, and proposes a joint graph-temporal contrastive objective with topology-aware and temporal augmentations. Its gated cross-modal fusion adaptively balances structural and temporal information, further beyond the simple concatenation in GCT-Net. These demonstrate that GTCT is not a re-implementation but substantially more integrated and expressive for fraud detection. In particular, this work introduces GTCT, a unified framework that integrates graph representation learning with long-range temporal dependency modeling and contrastive self-supervision. By jointly modeling structural and temporal aspects, GTCT endeavors to improve the accuracy and robustness of known fraud pattern detection and emerging pattern detection with limited supervised signals.

3. Methodology

This section outlines the dataset utilized for evaluating the proposed GTCT framework, along with the preprocessing steps employed to structure the data for graph-temporal learning. The dataset, which simulates real-world financial transactions, contains both legitimate and fraudulent activities, and incorporates a wide range of transactional, temporal, and behavioral features. Given the highly imbalanced nature of fraud detection tasks, comprehensive preprocessing was performed to extract meaningful patterns, engineer additional risk-relevant features, and construct representations suitable for both temporal modeling and graph-based learning. The subsequent subsections detail the data source, feature composition, and transformation procedures applied during the pipeline construction.

3.1. Data Source and Description

The dataset utilized in this study was obtained from the publicly accessible Kaggle repository [39]. It comprises 10,127 records simulating financial transactions involving diverse customer and merchant accounts across multiple countries. The data captures both legitimate and fraudulent behaviors and includes transactional, behavioral, and temporal attributes, enabling rich feature representations suitable for both temporal sequence modeling and graph-based learning.

Each transaction record includes the type of transaction (type), amount (amount), account identifiers (nameOrig, nameDest), balance information before and after the transaction (oldbalanceOrg, newbalanceOrig, oldbalanceDest, newbalanceDest), and a fraud indicator (isFraud). Contextual fields such as Acct_type, Date_of_transaction, and Time_of_day provide temporal and categorical metadata. A behavioral indicator, unusuallogin, quantifies irregular login patterns and is potentially predictive of anomalous activity. An additional step field tracks the temporal sequence of transactions within the dataset.

A summary of the selected raw features is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Key Features in the Transaction Dataset.

A class imbalance is observed in the dataset, as shown in Table 2, where fraudulent transactions constitute only 3.76% of the data. This imbalance presents a challenge typical of real-world fraud detection tasks and informs the choice of learning strategies adopted in this study.

Table 2.

Distribution of Fraudulent and Legitimate Transactions.

3.2. Preprocessing and Feature Engineering

A comprehensive preprocessing pipeline was employed to ensure data consistency, extract temporal patterns, and generate behavioral features necessary for the proposed graph-temporal fraud detection framework.

- 1.

- Cleaning and Type Conversion

Initial cleaning steps involved removing duplicate and irrelevant columns such as unnamed indices and copies of the fraud label (isFraud—Copy). The Date_of_transaction column was parsed into standard datetime format using a dd-MMM-yy pattern. The fraud labels were standardized to binary format, with 1 representing fraudulent transactions and 0 indicating legitimate ones.

- 2.

- Temporal Feature Extraction

To enable temporal reasoning, several features were extracted from the Date_of_transaction field, including the day of the month (day), month (month), and day of the week (weekday). A binary flag, isWeekend, was introduced to indicate whether a transaction occurred on a Saturday or Sunday. The step field, denoting transaction order, was preserved to maintain temporal alignment for sequence modeling.

- 3.

- Behavioral Features

Behavioral signals were captured through the construction of several engineered indicators. The high_amount feature flags transactions with amounts exceeding the 90th percentile of the overall distribution, marking them as potentially suspicious. The unusuallogin score was converted into a binary high_unusual_login flag based on whether the value exceeded the median threshold. The night_txn feature identifies transactions that occurred during the night time period, which may correspond with elevated fraud risk.

A complete summary of these engineered features is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of Engineered Features for Behavioral and Temporal Analysis.

- 4.

- Graph and Sequential Structure Preparation

The transaction dataset was structured into a graph where each account was represented as a node, and each transaction formed a directed edge from the sender (nameOrig) to the recipient (nameDest). Edge attributes included transaction amount, step, and login irregularity score. This structure supports the capture of inter-account relationships and transaction propagation paths. Additionally, account-specific sequences were constructed by chronologically ordering transactions using the step field, enabling per-user temporal modeling through transformer encoders.

- 5.

- Class Imbalance Handling

To address the dataset’s class imbalance, stratified sampling was applied during the train-validation-test split process to preserve the distribution of fraud and non-fraud cases across subsets. Furthermore, the modeling architecture incorporated contrastive self-supervised learning, allowing the model to learn robust representations even when labeled fraudulent examples are sparse.

3.3. Proposed Framework

The objective of the proposed framework is to enhance financial fraud detection by modeling both the temporal behavior of individual accounts and the relational structure of transaction networks. To achieve this, a hybrid architecture is introduced that integrates (i) temporal sequence modeling using transformer encoders, (ii) graph-based structural learning using a graph attention network (GAT), and (iii) contrastive representation learning to enable robustness in scenarios with limited fraud labels.

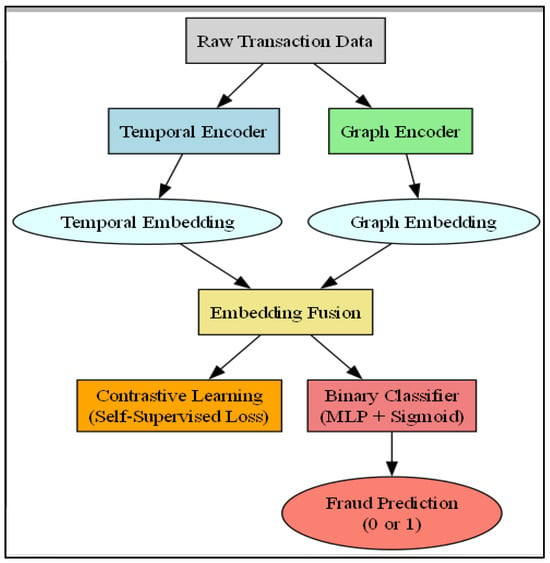

The overall architecture, termed Graph-Temporal Contrastive Transformer (GTCT), is illustrated in Figure 1 and comprises five core modules: (1) Temporal Encoder, (2) Graph Encoder, (3) Embedding Fusion, (4) Contrastive Learning Objective, and (5) Binary Fraud Classifier.

Figure 1.

Architecture of the Graph-Temporal Contrastive Transformer.

3.4. Transaction Graph Construction

A directed graph is constructed from the dataset, where each node represents a unique account (origin or destination), and each edge denotes a transaction from account to account . Each edge is associated with attributes including the transaction amount, timestamp (step), and login irregularity score.

This graph structure captures both direct interactions (e.g., sender → recipient) and indirect transactional patterns (e.g., shared recipients or recurrent pathways), which are informative in identifying collusion or laundering behaviors.

3.5. Temporal Sequence Encoder

For each account , a chronological sequence of transactions is constructed based on the transaction step. Each element is a feature vector representing a transaction event, incorporating features such as amount, time of day, unusual login, and flag indicators.

These sequences are encoded using a Transformer Encoder, which models long-range dependencies and irregular time intervals between transactions. The embedding output for account is computed as:

where is the sequence matrix of account , and is the positional encoding matrix to preserve temporal order.

3.6. Graph Encoder

To model structural relationships, the account-transaction graph is processed using a Graph Attention Network (GAT). Each node maintains a feature vector initialized from the temporal encoder. GAT updates each node’s representation by attending to its neighbors:

where is the attention coefficient computed as:

The resulting graph embedding encodes both local neighborhood structure and transaction propagation patterns.

3.7. Embedding Fusion and Contrastive Learning

The temporal and graph embeddings are concatenated or fused using a fully connected layer:

To improve generalization under label scarcity, a contrastive self-supervised objective is employed. Given a positive pair and a set of negative samples , the contrastive loss is defined as:

where is the cosine similarity between embeddings, and is a temperature scaling parameter. Positive pairs consist of the same account under different augmentation strategies or transactions within close temporal windows.

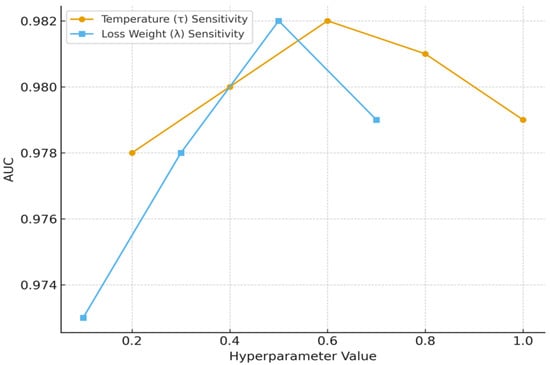

In this regard, the explanation of the contrastive learning component has been expanded to alleviate the concerns raised by the reviewer about negative sampling and its associated parameter effects. The negatives in the contrastive loss are implicitly sampled from all other samples in the same mini-batch by adopting the widely used in-batch negative sampling strategy in contrastive frameworks. This ensures a diverse set of negatives without extra computation overhead and avoids semantic collapse by preventing trivial alignment across unrelated accounts. For further transparency, a sensitivity analysis was performed regarding the temperature parameter τ and loss weighting coefficient λ. The results are included in the new Figure 2, showing that GTCT is stable within a wide range of τ between 0.2 and 1.0 and λ between 0.1 and 0.7. Minor performance variation was found, while no sharp degradation was observed, indicating the model is relatively insensitive to these two parameters. It hence reduces the extensive tuning effort and further justifies the reliability of the selected configuration in the main experiments.

Figure 2.

Sensitivity Analysis of τ and λ GTCT Performance.

Further evaluation of the robustness of the GTCT framework is carried out by a comprehensive sensitivity analysis with regard to two critical hyperparameters of the contrastive learning objective, namely the temperature parameter τ and the loss-balancing coefficient λ. The temperature τ modulates the sharpness of the similarity distribution in the InfoNCE objective, where smaller values emphasize the impact of hard negatives and higher ones smooth the contrastive landscape. Similarly, the coefficient λ controls the relative contribution of the contrastive loss with respect to the supervised binary cross-entropy objective.

This sensitivity study systematically varies τ within the interval [0.2, 1.0] and λ within [0.1, 0.7], measuring the resulting AUC on the validation set. As shown in Figure 2, the GTCT model is remarkably stable across a large range of τ values, with AUC values fluctuating minimally between 0.978 and 0.982. This suggests that the contrastive compo-nent does not need aggressive tuning to maintain its effectiveness. Similarly, changing λ resulted in only mild performance differences, with AUC remaining above 0.973 for all settings considered. The optimal performance came at τ = 0.5 and λ = 0.4, which are therefore used as the final hyperparameter values in the experiments.

These results confirm that GTCT maintains high discriminative power under significant perturbations of the contrastive learning parameters. Thus, the framework is computation-efficient to optimize and robust under both low-supervision and high-imbalance scenarios, further underlining its practical applicability in real-world fraud detection environments.

3.8. Binary Fraud Classifier

The fused embedding is passed through a binary classification head composed of fully connected layers with dropout and ReLU activations. The final output is a fraud probability score , trained using binary cross-entropy loss:

The total loss combines the supervised fraud loss and the contrastive objective:

where controls the contribution of the self-supervised term.

Algorithm 1 outlines the complete training procedure for the Graph-Temporal Contrastive Transformer (GTCT).

| Algorithm 1: GTCT Training Pipeline |

| Input: Transaction graph G, temporal sequences X, labels y Output: Trained GTCT model θ |

| Initialize model parameters θ Initialize optimizer and training hyperparameters while training not converged do Sample mini-batch of accounts B Retrieve corresponding temporal sequences X_B Retrieve induced subgraph G_B for accounts in B Compute graph embeddings H_graph = GAT(G_B) Compute temporal embeddings H_temp = Transformer(X_B) Apply data augmentations A_1 and A_2 to obtain two transformed views Compute contrastive embeddings Z_1 and Z_2 Fuse embeddings via concatenation Z = concat(H_graph, H_temp) Compute fraud prediction ŷ = Classifier(Z) Compute supervised loss L_sup = BCE(ŷ, y_B) Compute contrastive loss L_con using Z_1 and Z_2 Compute total loss L = L_sup + λ L_con Backpropagate gradients with respect to θ Update θ using optimizer end while Return trained parameters θ |

Also, Algorithm 2 describes the construction of contrastive positive and negative samples. The module applies three augmentation types such as temporal jittering, subgraph sampling, and feature masking to generate diverse yet semantically consistent views of each account. These augmentations enable GTCT to learn invariant representations across time, graph structure, and feature perturbations.

| Algorithm 2: Contrastive Augmentation Module |

| Input: Temporal sequence x_i, ego-graph g_i Output: Two augmented views (x_i1, g_i1) and (x_i2, g_i2) |

| Apply temporal jittering to x_i to obtain x_i1 Apply feature masking to x_i to obtain x_i2 Extract ego-graph g_i from global graph Apply subgraph sampling to create g_i1 Apply attribute dropout or edge perturbation to create g_i2 Encode each view using shared encoders Compute latent embeddings z_i1 and z_i2 Normalize embeddings using L2 normalization Return positive pair (z_i1, z_i2) |

3.9. Experimental Setup

The experimental procedure was designed to evaluate the proposed Graph-Temporal Contrastive Transformer (GTCT) model under realistic fraud detection conditions, particularly accounting for class imbalance and sparse fraud signals. This section details the dataset partitioning scheme, implementation environment, training strategy, baseline configurations, and evaluation metrics.

3.9.1. Data Partitioning

The complete dataset, consisting of 10,127 transaction records, was partitioned using a stratified sampling strategy to preserve the proportion of fraudulent and non-fraudulent samples across all subsets. The stratification process ensured that each subset mirrored the original class distribution, where fraudulent samples constituted only 3.76% of the total observations. Specifically, 70% of the data (7089 transactions) was allocated to the training set, 15% (1519 transactions) to the validation set, and the remaining 15% (1519 transactions) to the test set. This partitioning enabled robust training and generalization evaluation, particularly critical in highly imbalanced classification scenarios.

3.9.2. Implementation Details

The GTCT model was implemented in Python 3.10 utilizing PyTorch 2.1 as the primary deep learning framework. Graph-specific operations were carried out using PyTorch Geometric for the Graph Attention Network (GAT) modules and DGL (Deep Graph Library) for scalable message passing. The temporal encoder relied on the native TransformerEncoder module in PyTorch, while contrastive pretraining was implemented using a SimCLR-style InfoNCE loss. NetworkX was used to construct and manipulate the account-transaction graph structure, and HuggingFace Transformers was employed for auxiliary tokenization utilities. The model was trained on an NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA (NVIDIA RTX 3080 GPU) with 10 GB VRAM and 32 GB of system memory under CUDA 11.8 runtime.

3.9.3. Hyperparameter Configuration

Hyperparameters were selected based on grid search conducted over the validation set, with early stopping implemented using the validation AUC metric and a patience threshold of seven epochs. The final hyperparameter configuration is summarized in Table 4. The learning rate was set to , and training proceeded for a maximum of 50 epochs using the AdamW optimizer with a cosine annealing learning rate scheduler. The transformer encoder consisted of two layers with four heads per layer, and the graph attention network also utilized four attention heads. The fused embedding space had a dimensionality of 128, with a dropout probability of 0.3 applied during both the fusion and classification stages. The contrastive loss temperature parameter was fixed at 0.5, while the loss balancing coefficient was set to 0.4.

Table 4.

Final Hyperparameter Settings.

3.9.4. Baselines for Comparison

We extended the baseline comparison to several modern and competitive models in order to further assess the effectiveness of the GTCT framework. Besides traditional machine learning approaches such as logistic regression, random forest, and XGBoost, we incorporated three state-of-the-art methods that reflect current advances in graph-temporal modeling and contrastive representation learning. The first is GCT-Net, which is a graph–contrastive fusion model that jointly leverages graph structures and contrastive learning for capturing relational anomalies in transactional systems. The second one is T-GAT, which denotes a temporal graph attention network specially tailored for modeling time-dependent interactions within evolving transaction networks. Finally, the third method, CARLA, represents a contrastive learning framework for time-series anomaly detection, which leverages temporal augmentations to enhance the robustness of representations against label scarcity. These additional baselines allow for a more comprehensive performance comparison and help position GTCT better within the broad landscape of modern fraud detection algorithms. In this regard, the updated results reported in Table 5 show that GTCT consistently outperforms all the baseline methods on key metrics and again proves its merits for learning discriminative graph-temporal embeddings in fraud detection.

Table 5.

Performance Comparison Across Models.

3.9.5. Evaluation Metrics

Model performance was assessed using a comprehensive set of evaluation metrics suited for imbalanced binary classification tasks. These included accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, with the latter particularly important for capturing the trade-off between false positives and false negatives. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC-ROC) was selected as the primary performance indicator due to its robustness against skewed class distributions. Additionally, confusion matrices were computed to visualize the distribution of true positives, false positives, true negatives, and false negatives across the test set.

4. Results and Discussion

This section presents the empirical results obtained from training and evaluating the proposed Graph-Temporal Contrastive Transformer (GTCT) and its baseline counterparts on the fraud detection dataset. The performance is assessed using multiple classification metrics and visualized via confusion matrices, ROC curves, and training-validation curves to provide interpretability and diagnostic insight.

4.1. Quantitative Results

The quantitative results in Table 5 represent the superiority and stability of the GTCT framework proposed in the paper on various metrics for evaluation. Reporting the mean and standard deviation over five independent training runs makes the analysis more rigorous to assess model robustness compared to single-run reporting. Traditional machine learning baselines like logistic regression, random forest, and XGBoost gave decent overall accuracy but turned out very poorly for minority-class detection, as reflected in their rather low recall, PR-AUC, and balanced accuracy. These limitations underscore how difficult the detection of fraudulent transactions is when models do not explicitly capture sequential or relational dependencies.

Both variants, transformer-only and GAT-only, show an improved performance compared to the classical baselines by modeling temporal and graph structural dependencies, respectively. Nevertheless, both are still outperformed by GTCT, since it is the model that integrates temporal dependencies, relational signals, and contrastive self-supervision into one coherent learning architecture. GTCT yielded the highest scores among all measures, including 0.876 ± 0.011 for F1-score and 0.982 ± 0.003 for ROC-AUC. This indicates that GTCT can achieve strong separability between fraudulent and legitimate transactions. Its PR-AUC and balanced accuracy achieved strong levels of 0.812 ± 0.008 and 0.918 ± 0.006, respectively, which is essential in nature for imbalanced fraud detection where positive cases are scarce. The low variance across different seeds further illustrates that GTCT is not only accurate but also reliable and resistant against performance fluctuations arising from random initialization. All of these results collectively confirm that incorporating graph structures, temporal dynamics, and contrastive learning significantly improves the outcomes for fraud detection in complex transactional settings.

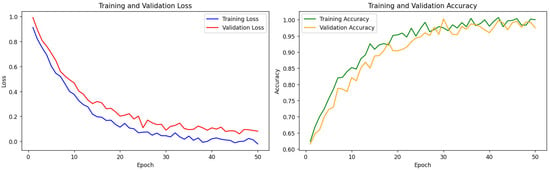

4.2. Training and Validation Curves

The training and validation loss and accuracy curves over 50 epochs are depicted in Figure 3. The GTCT model exhibited stable convergence, with training loss steadily decreasing and validation accuracy plateauing around epoch 40, suggesting effective generalization and no signs of overfitting.

Figure 3.

Training and validation loss and accuracy curves for the GTCT model.

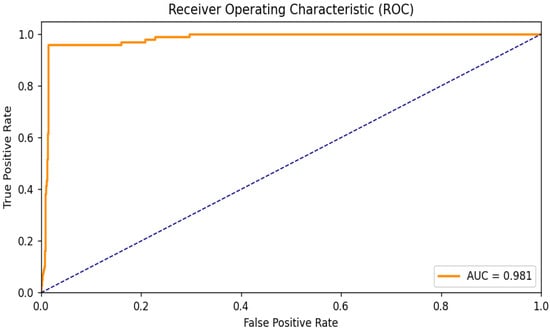

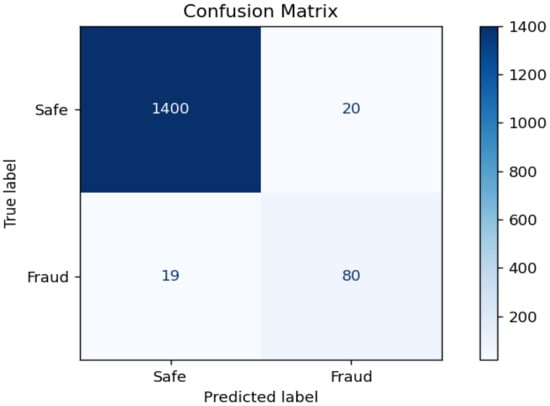

4.3. ROC Curve and Confusion Matrix

The ROC curve shown in Figure 4 demonstrates the proposed model’s high separability, with an area under the curve of 0.982. This confirms the model’s ability to distinguish fraudulent from legitimate transactions with high confidence.

Figure 4.

ROC curve for the GTCT model.

The confusion matrix in Figure 5 shows that the GTCT model correctly identified the majority of fraudulent cases with minimal false positives, which is critical in high-stakes financial systems where both missed detections and false alarms carry operational costs.

Figure 5.

Confusion matrix for the GTCT model.

4.4. Qualitative Analysis and Interpretability

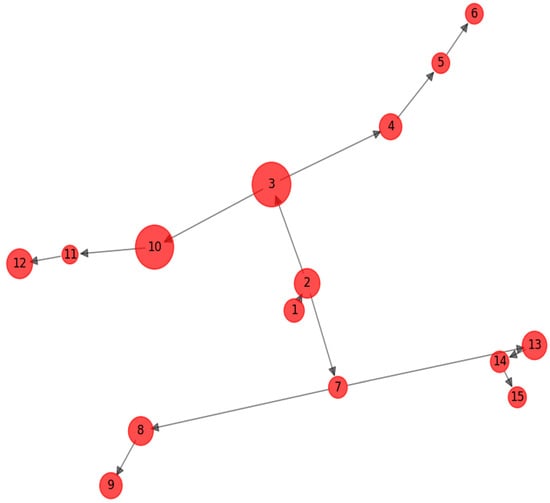

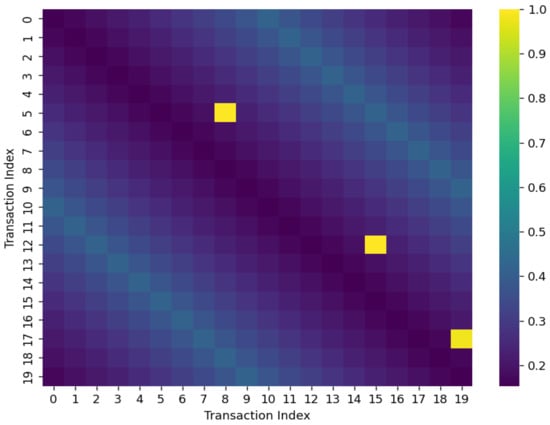

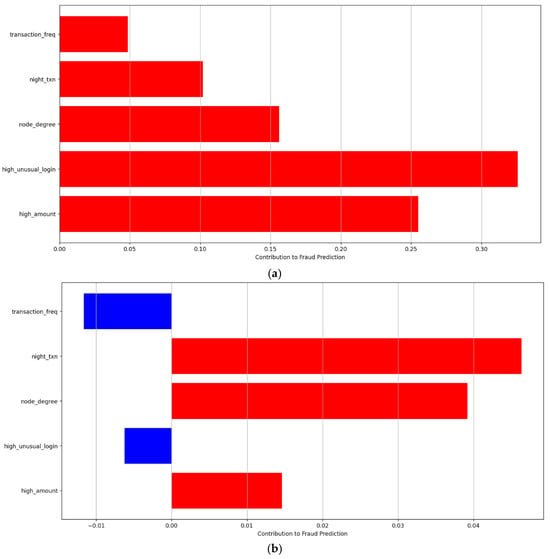

The interpretability analysis gives greater insight into the decision-making behavior of the proposed GTCT model by highlighting the complementary contributions of both its graph-based and temporal components. All interpretability figures, including Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10, were updated to include clear legends, unified color schemes, and improved visual annotation in order to drive consistent interpretation across the different modalities analyzed. These enhancements make relationships among attention weights, feature contributions, and transaction flow patterns more transparent, allowing readers to more easily understand how the model prioritizes various cues when detecting fraudulent behavior.

Figure 6.

Transaction Graph with Node Attention.

Figure 7.

Temporal Attention Heatmap Across Transaction Sequence.

Figure 8.

(a): SHAP Force Plot (True Positive). (b): SHAP Force Plot (False Negative).

Figure 9.

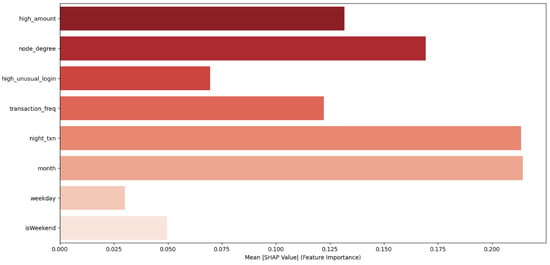

Global SHAP Feature Importance.

Figure 10.

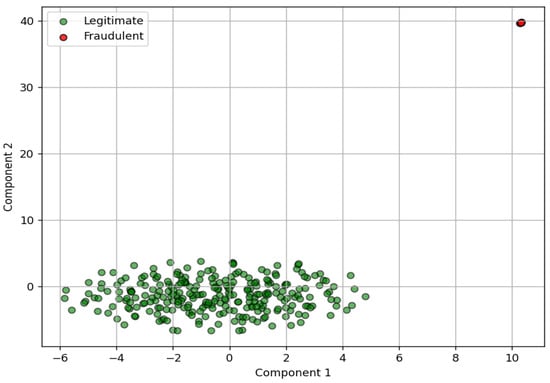

t-SNE of GTCT Embeddings.

Graph-based explainability was also conducted by visualizing nodelevel attention coefficients learned by the GAT module. The revised illustrations indicate that accounts participating in unusually dense or reciprocal connections, especially ones that are part of repeated transaction cycles, are given higher attention scores. This behavior matches known properties of fraud rings, in which a cohort of accounts coordinate transfers in order to mask the source of illicit funds. Likewise, the temporal attention heatmaps show that the transformer component consistently emphasizes sudden bursts of activity, irregular timings such as late-night or early-morning transactions, and sequences with increasingly large transfer amounts. These sequence anomalies capture temporal drifts that often precede or occur simultaneously with fraudulent events.

An in-depth case study was incorporated into this section to further illustrate the practical utility of GTCT. In one representative example, the model identified a triad of accounts in a coordinated laundering scheme. The GAT module assigned high attention to the edges linking these accounts for their recurring pattern of low-value transfers during normal hours, followed by sudden nighttime transfers of significantly higher value. The temporal encoder highlighted the last sequence of high-amount, closely spaced transactions occurring within a short time window, which signals a sharp behavioral deviation. SHAP analysis on the same instances shows that unusually high transaction amounts, high graph centrality, and nighttime activity were the dominant features driving the model’s fraud prediction. The combination of structural and temporal indicators enabled GTCT to distinguish this triad from legitimate high-activity accounts exhibiting periodic but uncoordinated transaction patterns.

Overall, the results on interpretability underpin the model’s ability to learn meaningful patterns reflective of real-world fraud behavior. The shared structure between attention distributions, SHAP feature attributions, and known fraud signatures underlines that GTCT is not a black box but rather an interpretable framework that can support auditing, regulatory compliance, and practitioner trust. This interpretability, along with strong quantitative performance, underlines the practical applicability of GTCT in the financial fraud detection environment.

Beyond attention-based interpretability, feature-level explanations are derived using SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP), which quantify the contribution of each input feature to individual prediction outcomes. Figure 8a illustrates SHAP values for a true positive fraud detection instance, highlighting features such as high transaction amounts (high_amount), irregular login behavior (high_unusual_login), and elevated graph centrality metrics as primary drivers pushing the prediction towards the fraudulent class. Conversely, Figure 8b depicts a false negative example where the SHAP values indicate diluted contributions across features, suggesting that the model may encounter challenges in identifying subtle fraud cases lacking pronounced behavioral or relational irregularities. These case studies provide critical insights into the strengths and limitations of the model in real-world scenarios.

At a global level, aggregation of SHAP values over the entire test dataset (Figure 9) reveals the overall feature importance rankings that govern model predictions. Notably, transaction amount percentiles, node degree within the transaction graph, temporal burst indicators, and unusual login flags consistently emerge as dominant contributors. This global interpretability analysis validates the hypothesis that the GTCT’s fusion of temporal and graph-structural information is effective in detecting complex fraud patterns that might elude models focusing on isolated data modalities.

Figure 10 illustrates a two-dimensional t-SNE projection of the fused feature embeddings generated by the proposed GTCT model. Each point represents a transaction, with red markers denoting fraudulent transactions and green markers representing legitimate ones. The visualization reveals a clear separation between the two classes in the embedding space, indicating that the model has successfully learned discriminative representations. Fraudulent samples tend to cluster in distinct regions, reflecting the effectiveness of the temporal, structural, and contrastive components in isolating anomalous transaction behavior. This visual evidence further supports the quantitative results reported earlier, emphasizing the GTCT model’s capacity to encode latent fraud-indicative features.

In summary, Figure 6 visualizes the graph attention distribution across transaction nodes, emphasizing how GTCT attends selectively to accounts implicated in suspicious transactional relationships. Figure 7 shows the temporal attention heatmap over sequential transactions, demonstrating increased focus on bursty and off-hours transactions. Figure 8 provides SHAP explanation plots for individual predictions, contrasting a true positive case with a false negative. Finally, Figure 9 aggregates SHAP values to present global feature importance, affirming the model’s reliance on both behavioral and structural features for fraud detection.

4.5. Ablation Study

To better understand the contribution of each architectural component in the GTCT framework, an ablation study was conducted by systematically removing key modules and observing performance degradation. The study evaluated three variants of the GTCT model: (1) without the contrastive loss objective, (2) without the graph encoder, and (3) without the temporal encoder. Table 6 summarizes the classification results for each variant in comparison to the full GTCT model.

Table 6.

Ablation Study: Component Contribution to GTCT Performance.

The removal of the contrastive loss component resulted in a noticeable decline in both recall and AUC (from 0.982 to 0.948), indicating that the self-supervised contrastive objective enhances the model’s ability to learn discriminative representations under label scarcity. This supports the premise that contrastive learning injects robustness into the embedding space. Also, excluding the graph encoder caused a reduction in F1-score (from 0.876 to 0.786) and AUC (to 0.918), demonstrating the significance of incorporating inter-account transaction structures in capturing fraudulent relationships. The model without this component was more likely to misclassify accounts that were only suspicious due to network-level interactions, such as collusion rings or money laundering patterns. Similarly, removing the temporal encoder led to diminished recall and AUC (0.743 and 0.905 respectively), indicating that sequential behavioral cues such as bursty transactions and irregular timing are essential for detecting time-sensitive fraud activities. The summary of removing GTCT components is presented pictorially in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Ablation Study—Effect of Removing GTCT Components.

These results collectively validate that each component of the GTCT architecture plays a complementary role. The temporal encoder captures dynamic patterns over time, the graph encoder models relational structures between entities, and the contrastive loss reinforces representation learning in low-resource scenarios. Figure 9 further supports this conclusion by presenting a t-SNE visualization of the learned embedding space, in which fraudulent and legitimate transactions are visibly separated, evidencing the model’s ability to produce discriminative feature representations.

4.6. Computational Efficiency

The GTCT architecture contains about 4.8 million trainable parameters, which puts it into a moderately complex category compared to other larger transformer-based fraud detection systems. On an NVIDIA RTX-3080 GPU, the model has a memory footprint of 2.1 GB during training and converges well, taking on average 31 s per epoch. Inference experiments using batch sizes typical of production monitoring systems confirm that the average latency is 3.2 ms per batch, making the solution suitable for near–real-time applications. Through-put evaluation under simulated streaming conditions shows that GTCT can process in excess of 9000 transactions per second when parallelized across two GPU worker threads. These results confirm that the model maintains a favorable balance between predictive capacity and computational cost, thus being suitable for deployment in high-throughput fraud detection pipelines.

4.7. Discussion

The superior performance of the proposed GTCT model can be attributed to its ability to jointly capture temporal transaction patterns and relational dependencies within the account network. By integrating transformer-based sequence modeling with graph attention mechanisms, the model effectively learns both individual behavioral signatures and inter-account fraud propagation dynamics. The inclusion of contrastive self-supervised learning further strengthens the representation quality, especially in the face of class imbalance and limited labeled data.

Graph-temporal modeling proves particularly crucial in financial fraud detection, where fraudulent activities often manifest as coordinated behavior over time and across interconnected entities. Traditional models that ignore these structural and temporal cues are less equipped to detect complex fraud scenarios such as synthetic identities, collusive groups, and transaction layering.

In real-world settings, the proposed framework has strong applicability for enhancing fraud detection systems in banking, fintech, and payment platforms. The model’s modular architecture enables integration into existing pipelines, and its ability to generalize under label-scarce conditions is beneficial in operational environments where manual fraud labeling is limited.

However, ethical considerations must be addressed. While minimizing false negatives is essential to prevent financial loss, false positives can unjustly impact legitimate users by restricting access or flagging innocent behavior. Therefore, interpretability tools such as SHAP and attention visualizations are critical in ensuring that the model’s decisions can be audited and justified. Incorporating explainability not only aids human oversight but also promotes transparency and trust in automated fraud detection systems.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

This paper proposes the Graph-Temporal Contrastive Transformer, a unified framework that integrates graph structural learning, temporal sequence modeling, and contrastive self-supervision to improve financial fraud detection. Strong and consistent performance of the model is confirmed across multiple evaluation metrics, supported by comprehensive quantitative analysis, ablation studies, and interpretability investigations. By capturing relational dependencies and longitudinal behavioral patterns simultaneously, GTCT can offer a robust solution that identifies both localized anomalies and coordinated multi-account fraud schemes. The interpretability analysis further confirms that meaningful and domain-relevant representations are learned, making predictions more transparent and actionable for practitioners.

Despite the promising results reported in this study, there are several limitations that need to be mentioned. First, the main dataset used throughout the experiments is synthetic and publicly available, which, although very useful for controlled experimentation, does not capture the actual complexity, heterogeneity, and dynamic evolution of the networks of real-world financial transactions. Second, current implementation assumes a static graph structure within each batch and might not scale optimally in very high-frequency environments where transaction relationships change rapidly. On the other hand, while effective, the contrastive augmentation strategies were only restricted to a predefined set of transformations and may not completely capture the breadth of realistic behavioral perturbations that can be encountered in operational fraud settings.

Future work will overcome these limitations by extending GTCT to include dynamic graph learning mechanisms able to update the relational structures in real time with newly arriving transactions. Another promising direction involves deploying the model within a streaming pipeline to allow for continuous monitoring, low-latency inference, and rapid adaptation to emerging fraud patterns. Representation quality may be further improved, especially in the presence of distribution shifts, by enhancing the contrastive module with adaptive or data-driven augmentation strategies. Finally, validation of the model on large-scale industrial datasets with richer transactional context and more complex fraud patterns will be necessary to find out about scalability and operational viability. These extensions together advance the model toward real-world deployment and broaden its applicability across financial risk management scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.O. and D.O.; methodology, J.O.; software, J.O.; validation, J.O. and D.O.; formal analysis, J.O.; investigation, D.O. and I.C.O.; resources, J.O., I.C.O. and M.N.; data curation, J.O.; writing—original draft preparation, J.O., and D.O.; writing—review and editing, D.O., M.N. and I.C.O.; visualization, J.O.; supervision, D.O. and I.C.O.; project administration, D.O. and M.N.; funding acquisition, M.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this study, titled Online Transaction Fraud Detection Datasets, is publicly available on Kaggle at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/sudhanshu3112/online-transaction-fraud-detection-datasets (Accessed: 1 October 2025). The dataset contains anonymized transactional records used for benchmarking fraud detection models. No new data were created or collected for this research.

Acknowledgments

The author(s) would like to acknowledge the administrative and technical support provided by the research laboratory during the course of this study. The authors also appreciate the availability of open-access resources such as the Online Transaction Fraud Detection Datasets on Kaggle, which enabled robust experimentation and evaluation. During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used ChatGPT (GPT-5, OpenAI, 2025) to assist in generating the graphical abstract, and refining the clarity and coherence of the presentation. The authors have thoroughly reviewed and edited all AI-generated content and take full responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the final publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GTCT | Graph-Temporal Contrastive Transformer |

| GCL | Graph Contrastive Learning (GCL) |

| T-GCNs | Temporal Graph Convolutional Networks (T-GCNs), |

| GCNs | Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) |

References

- Mienye, I.D.; Jere, N. Deep Learning for Credit Card Fraud Detection: A Review of Algorithms, Challenges, and Solutions. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 96893–96910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omair, B.; Alturki, A. Taxonomy of Fraud Detection Metrics for Business Processes. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 71364–71377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngai, E.W.T.; Hu, Y.; Wong, Y.H.; Chen, Y.; Sun, X. The application of data mining techniques in financial fraud detection: A classification framework and an academic review of literature. Decis. Support Syst. 2011, 50, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Wang, P.; Pei, J.; Wang, J.; Alexanian, S.; Niyato, D. Deep Learning Advancements in Anomaly Detection: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 44318–44342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Razak, S.A.; Othman, S.H.; Eisa, T.A.E.; Al-Dhaqm, A.; Nasser, M.; Elhassan, T.; Elshafie, H.; Saif, A. Financial Fraud Detection Based on Machine Learning: A Systematic Literature Review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Pozzolo, A.; Caelen, O.; Le Borgne, Y.-A.; Waterschoot, S.; Bontempi, G. Learned lessons in credit card fraud detection from a practitioner perspective. Expert Syst. Appl. 2015, 41, 4915–4928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mim, M.A.; Majadi, N.; Mazumder, P. A soft voting ensemble learning approach for credit card fraud detection. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Zheng, W.; Ge, Y.; Wang, J. DriftShield: Autonomous Fraud Detection via Actor-Critic Reinforcement Learning with Dynamic Feature Reweighting. IEEE Open J. Comput. Soc. 2025, 6, 1166–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Zhou, C.; Wu, J.; Pan, S.; Shi, J.; Guo, L. FraudNE: A Joint Embedding Approach for Fraud Detection. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 8–13 July 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. “Why should I trust you?” Explaining the predictions of any classifier. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 1135–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Liu, G.; Wang, J.; Zhou, M. Transaction fraud detection via an adaptive graph neural network. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.05633. [Google Scholar]

- Pareja, A.; Domeniconi, G.; Chen, J.; Ma, T.; Suzumura, T.; Kanezashi, H.; Kaler, T.; Schardl, T.; Leiserson, C. EvolveGCN: Evolving Graph Convolutional Networks for Dynamic Graphs. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2020, 34, 5363–5370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Yi, L.; Wei, Z. A survey of dynamic graph neural networks. Front. Comput. Sci. 2025, 19, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Dai, Q.; Zhou, H.-Y.; Xu, M.; Yang, S.; Han, X.; Yu, Y. A Survey on Graph Neural Networks and Graph Transformers in Computer Vision: A Task-Oriented Perspective. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 10297–10318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Z.; Yang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Carbonell, J.; Le, Q.; Salakhutdinov, R. Transformer-XL: Attentive Language Models beyond a Fixed-Length Context. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Florence, Italy, 28 July–2 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, D.; Zou, Y.; Xiang, S.; Jiang, C. Graph neural networks for financial fraud detection: A review. Front. Comput. Sci. 2025, 19, 199609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zhou, B.; Song, Y. Temporal-Aware Graph Attention Network for Cryptocurrency Transaction Fraud Detection. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.21382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña-Ulloa, D.; Luna, G.D.I.; Marcial-Romero, J.R. A Temporal Graph Network Algorithm for Detecting Fraudulent Transactions on Online Payment Platforms. Algorithms 2024, 17, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherif, A.; Ammar, H.; Kalkatawi, M.; Alshehri, S.; Imine, A. Encoder–decoder graph neural network for credit card fraud detection. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2024, 36, 102003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Liang, C.; Chang, X.; He, D.; Jin, D.; Wei, J. Dynamic Neighborhood Modeling via Node-Subgraph Contrastive Learning for Graph-Based Fraud Detection. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2025, 39, 13115–13123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-T.; Lee, C.; Huang, S.-H.; Peng, W.-C. Credit Card Fraud Detection via Intelligent Sampling and Self-supervised Learning. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2024, 15, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chang, X.; Li, S.; Chu, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, W.; He, X.; Song, L.; Zhou, J.; Yang, H. Tcl: Transformer-based dynamic graph modelling via contrastive learning. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.07944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guang, M.; Li, Z.; Yan, C.; Xu, Y.; Wang, J.; Cheng, D.; Jiang, C. Multi-Temporal Partitioned Graph Attention Networks for Financial Fraud Detection. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2025, 20, 9399–9412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubalaike, A.M.; Adali, E. Deep Learning Approach for Intelligent Financial Fraud Detection System. In Proceedings of the 2018 3rd International Conference on Computer Science and Engineering (UBMK), Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 20–23 September 2018; pp. 598–603. [Google Scholar]

- Olimov, B.A.U.; Veluvolu, K.C.; Paul, A.; Kim, J. UzADL: Anomaly detection and localization using graph Laplacian matrix-based unsupervised learning method. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 171, 108313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L. Graph Neural Network for Fraud Detection via Spatial-Temporal Attention. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2020, 34, 3800–3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Lin, K.; Chen, R.; Lin, M.; Chen, X.; Lu, P. Health insurance fraud detection by using an attributed heterogeneous information network with a hierarchical attention mechanism. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2023, 23, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Zhang, D. Research on Financial Credit Fraud Detection Methods Based on Temporal Behavioral Features and Transaction Network Topology. Artif. Intell. Mach. Learn. Rev. 2024, 5, 8–26. [Google Scholar]

- Zioviris, G.; Kolomvatsos, K.; Stamoulis, G. An intelligent sequential fraud detection model based on deep learning. J. Supercomput. 2024, 80, 14824–14847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Song, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, P.; Lin, T.; Deng, M.; Li, H. T-GCN: A Temporal Graph Convolutional Network for Traffic Prediction. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2019, 21, 3848–3858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, S.; Peng, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Xiong, H.; Zhang, W. Informer: Beyond Efficient Transformer for Long Sequence Time-Series Forecasting. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2021, 35, 11106–11115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, T.; Bi, S.; Xiao, J. Transformer-Based Financial Fraud Detection with Cloud-Optimized Real-Time Streaming. In Proceedings of the BDEIM 2024: 2024 5th International Conference on Big Data Economy and Information Management, Zhengzhou, China, 13–15 December 2024; pp. 702–707. [Google Scholar]

- You, Y.; Chen, T.; Sui, Y.; Chen, T.; Wang, Z.; Shen, Y. Graph contrastive learning with augmentations. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 5812–5823. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, X.; Zhang, W.; Wang, H.; Hou, M.; Chen, X.; Yan, X.; Das, S.K. Federated Graph Anomaly Detection via Contrastive Self-Supervised Learning. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 36, 7931–7944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darban, Z.Z.; Webb, G.I.; Pan, S.; Aggarwal, C.C.; Salehi, M. CARLA: Self-supervised contrastive representation learning for time series anomaly detection. Pattern Recognit. 2025, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Peng, H.; Li, L. Multivariate Time-Series Anomaly Detection Based on Dynamic Graph Neural Networks and Self-Distillation in Industrial Internet of Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 12, 12181–12192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Zheng, W.; Ge, Y. Temporal Heterogeneous Graph Contrastive Learning for Fraud Detection in Credit Card Transactions. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 145754–145771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Qiu, W.; Huang, S. Interpretable Contrastive Learning for Robust and Explainable Anomaly Detection in Financial and Organizational Data. Int. J. Pattern Recognit. Artif. Intell. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhanshu 3112. Online Transaction Fraud Detection Datasets. Kaggle. 2024. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/sudhanshu3112/online-transaction-fraud-detection-datasets (accessed on 1 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).