Abstract

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is a leading cause of death worldwide. Unfortunately, due to various reasons, this disease is currently spreading rapidly. Many heart disease sufferers die due to the inaccuracy of diagnostic tools or the delay in seeing a doctor. Therefore, the correct and timely diagnosis of this disease plays an important role in preventing deaths. The method used in this research to diagnose coronary artery disease (CAD) is a combination of the following algorithms: Support Vector Machine, Naïve Bayes, Logistic Regression, Random Forest, K-Nearest Neighbors, and XGBoost with ANOVA feature selection method. The dataset was evaluated using two complementary validation strategies: a hold-out test set and 10-fold cross-validation. In the proposed method, the SHAP algorithm was implemented on the output of the XGBoost model. Using this algorithm makes the output of the model interpretable and brings the model out of black box status. With the hold-out method, the K-Nearest Neighbor model with the features selected by the ANOVA method obtained an accuracy of 93.33%. Then, the Support Vector Machine and XGBoost models obtained the best results with an accuracy of 91.66%. With the 10-fold cross-validation method of the model, XGBoost achieved 86.16% accuracy and 87.41% recall value, which increased the results obtained in both methods compared to the state-of-the-art methods.

1. Introduction

The heart is a vital organ that delivers blood throughout the human body. Impaired heart function can endanger other organs and may ultimately lead to death. Factors such as lifestyle changes, work-related stress, and unhealthy diets contribute to the increasing prevalence of heart diseases [1]. More than 80% of premature deaths are caused by four major non-communicable diseases: cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases, cancer, and diabetes [2]. According to the World Health Organization, cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of death worldwide, causing approximately 17.9 million deaths annually, and this number is expected to rise [3].

Many patients die due to inaccurate diagnostic tools or delays in seeking medical care. Therefore, accurate and timely diagnosis is critical in preventing fatalities [4]. Traditional diagnostic and treatment methods can be costly, time-consuming, and may have side effects. Machine learning and data mining technologies provide effective alternatives by uncovering hidden patterns and relationships in medical data, which can assist doctors in making faster and more accurate decisions [5].

Conventional diagnostic methods sometimes face challenges, such as overlapping symptoms with other diseases or human errors in diagnosis. Machine learning-based approaches can help overcome these limitations by improving prediction accuracy. Despite existing research, many studies do not apply feature selection, which can limit model performance.

To address this gap, this study employs multiple machine learning algorithms, including Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machine, Naïve Bayes, K-Nearest Neighbor, Random Forest, and XGBoost, along with ANOVA-based feature selection. XGBoost is also evaluated without feature selection. Additionally, SHAP is used to interpret XGBoost outputs, enhancing model transparency and identifying the contribution of each feature to predictions. This approach aims to improve diagnostic accuracy while reducing errors in heart disease detection.

The proposed approach presents an integrated and application-oriented framework that combines ANOVA-based feature selection with SHAP interpretability for heart disease prediction. This integration not only improves predictive accuracy and model transparency, but also demonstrates the practical utility of combining established techniques in clinical decision support systems. Therefore, the study emphasizes the value of applied explainable AI in enhancing both performance and interpretability.

2. Related Works

Articles that have been published in the field of using machine learning tools to predict heart attacks have been reviewed in this section. In the reviewed articles, various methods and datasets have been used to predict and diagnose various types of heart diseases.

Anita et al. [6] implemented the Support Vector Machine, Naïve Bayes, and K-Nearest Neighbor algorithms on the Cleveland cardiac patient dataset and divided the dataset into 70% for training and 30% for testing, respectively. In their proposed model, the Naïve Bayes classifier predicted the disease with an accuracy of 86.6% better than the other two models. Dwivedi [7] calculated the correlation between the parameters of the statlog cardiac patient dataset, available in the UCI source separately for positive and negative samples, and then used six classification techniques (Logistic Regression, Neural Networks, K-Nearest Neighbor, Decision Tree, Support Vector Machine, Naïve Bayes) to classify heart disease samples. He used the technique of 10-fold cross-validation for a more accurate evaluation. Logistic Regression classification with 85% and Neural Networks with 84% had the best accuracy, and in terms of sensitivity criteria, the two mentioned algorithms were the best. Al-Tai et al. [8] worked on the dataset of cardiac patients in Ibn al-Bitar Hospital and Baghdad Medical City. In their proposed model, four classification techniques were used, and the Bayesian Network achieved higher accuracy with 94.5% compared to other algorithms used, i.e., Sequential Minimum Optimization (SMO), Random Forest, and Multilayer Perceptron.

Some researchers used Ensemble Learning Methods to increase the accuracy of basic algorithms. In their proposed model, techniques such as Bagging, Boosting, and Stacking were used to increase the accuracy of some algorithms. As an example, Pouriyeh et al. [9] worked on the Cleveland dataset. They used the technique of 10-fold cross-validation. The accuracy of Decision Tree algorithms and Single Relational Rule Learners increased by using the Bagging and Boosting methods, and among the Bagging and Boosting methods, the Bagging method showed a greater increase. Using the accumulated method, an accuracy of 84.15% was achieved by using the combination of two Multilayer Perceptron models and a Support Vector Machine. Khan et al. [10] used two datasets related to heart and diabetes patients for their research. They used the Stacking method, which is a combination of algorithms: Dimension Reduction, Decision Tree, Naïve Bayes, K-Nearest Neighbor as a level one algorithm, and Support Vector Machine as the final decision maker on their dataset. They achieved higher accuracy than any of the cited methods individually, and as stated, this increase in accuracy is due to the use of Ensemble Learning algorithms, because these algorithms are often used to increase the power of the model in estimating the data output. Several models are used in combination and simultaneously for decision-making.

Extensive research has been conducted in this area. For example, Ali et al. [4] presented an intelligent care system for predicting heart disease using Deep Learning algorithms and feature selection methods. The dataset they used was collected from two sources, including wearable sensors and electronic patient files. In their proposed model, feature selection was performed using Information Gain, feature weighting using a probabilistic approach, and then the Deep Learning algorithm was implemented. Their method achieved an accuracy of 98.5%, which was higher than other methods used.

Kavitha et al. [11] divided the dataset of Cleveland cardiac patients into 70% and 30% for training and testing. They achieved 88.7% accuracy using a hybrid method, including a Random Forest and a Decision Tree algorithm. Hossein et al. [12] worked on a dataset of heart patients with 14 features and 899 rows to predict heart disease. They used J48, Naïve Bayes, One Rule, Zero Rule, Support Vector Machine, and Weighted Average Voting algorithm for prediction. Among the mentioned algorithms, the best model, the method mentioned last, was reported with 89% accuracy, which is a result that was predictable due to the weighted average. Shah et al. [13] applied four different algorithms to the previous dataset, and the accuracy obtained in their method was 90/78%, which was obtained by K-Nearest Neighbor. Ishaq et al. [14] used various techniques, such as Adaboost, etc. To solve the problem of class imbalance, the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) was used, and for feature selection, the Random Forest technique was used. The dataset used was heart failure-clinical, and the Extra Tree Classifier achieved an accuracy of 92.62%. Reddy et al. [15] achieved 90% accuracy using Rough sets and classification based on Fuzzy Rules with an Adaptive Genetic Algorithm on the Cleveland dataset. In the method proposed by Musa et al. [16], the Cleveland dataset was divided into different ratios and evaluated using an embedded feature selection algorithm, Bayesian Networks, and other algorithms. Bayesian Networks managed to achieve 88% accuracy by dividing the dataset into 80:20 ratios.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Dataset

The dataset used in this study is the Cleveland Coronary Heart Disease dataset from the UCI repository [17]. This dataset has 76 features and includes medical records of 303 patients with different features. After examining the features, it was determined that 62 features were removed due to a high percentage of missing data or lack of biological/clinical or pathophysiological relevance to heart disease. The remaining 14 features (Table 1) were selected based on data quality and clinical significance. These features were also used in previous studies.

Table 1.

Description of Cleveland dataset variables.

3.2. Data Preprocessing

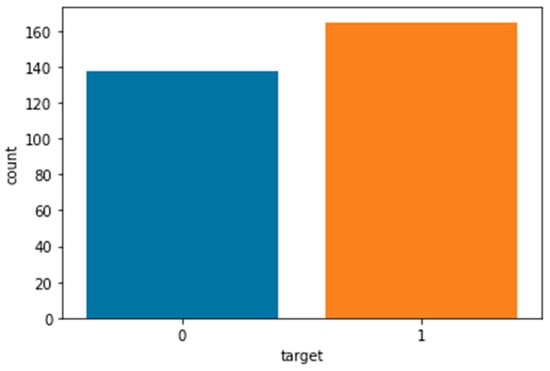

After introducing the dataset, the next step is to prepare the data for training. Data preprocessing includes managing missing values, standardizing data, converting the data into an understandable format for algorithms, and feature selection. In this dataset, rows containing missing values, which are only 6 rows, were deleted, and finally, the number of records was reduced from 303 to 297. The target variable, which had 4 values (0 meaning the absence of cardiovascular disease and 1–4 meaning the presence of heart disease of varying severity), was changed to a 2-value variable (0 meaning the absence of disease and 1 meaning the presence of disease). The distribution of the target variable based on the number of sick and non-sick individuals is also shown in Figure 1. According to Figure 1, among the 297 available records, 160 records correspond to healthy individuals (without disease), and 137 records have a value of 1 (indicating the presence of disease), which demonstrates a relatively balanced dataset. The results of the normality test showed that most variables were not normally distributed; therefore, standardization was applied to normalize the data.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the target variable. Among the 297 records, 160 correspond to healthy individuals (non-diseased) and 137 correspond to patients (diseased).

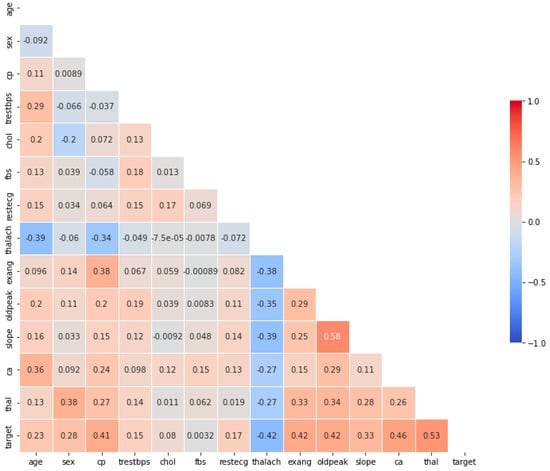

Figure 2 illustrates the Pearson correlation coefficients of the dataset variables. As shown in Figure 2, the highest correlation coefficient with the target variable belongs to the heart condition feature, while the lowest correlation is related to the fasting blood sugar feature. The correlation coefficients of the other features are also less than 0.53. In this study, the ANOVA feature selection method was used, and the features selected by this method were employed in the modeling process.

Figure 2.

Pearson correlation coefficients among the variables of the Cleveland coronary artery disease dataset. The heart condition (Thal) feature shows the highest positive correlation with the target variable, while fasting blood sugar (fbs) exhibits the weakest correlation.

3.3. Modeling/Machine Learning Algorithms

3.3.1. Support Vector Machine (SVM)

SVM is a kernel-based algorithm used for classification and regression. It selects a hyperplane that maximizes the margin between classes in the feature space. Common kernels, such as RBF and sigmoid, map data to higher-dimensional spaces to improve separability [18,19,20,21,22,23]. Equation (1) shows the RBF kernel, in which the Euclidean distance between two points , is multiplied by the gamma parameter γ as follows:

Equation (2) shows the sigmoid kernel function. In this equation, the parameters γ and show the slope and the constant term, respectively [23].

3.3.2. Logistic Regression (LR)

Logistic Regression (LR) predicts the probability of a binary outcome using a sigmoid function [24]. The Logistic Regression hypothesis is defined in Equation (3):

where g is a sigmoid function, and this hypothesis is defined as Equation (4):

The sigmoid function has special properties that create values in the range [0, 1] [25].

3.3.3. K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN)

K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) is a non-parametric algorithm for classification. The class of a sample is determined by the majority vote of its K-nearest neighbors [1,21,26]. To measure the distance, the Euclidean distance is used, and the method of its calculation is shown in Equation (5). To achieve the minimum error, the appropriate value of K should be selected [21,26].

3.3.4. Naïve Bayes (NB)

Naïve Bayes (NB) calculates posterior probabilities assuming independence of features using Bayes’ theorem, as shown in Equation (6):

In Equation (6), the desired class is indicated by and the features are indicated by , each of which must be calculated separately. The posterior probability of class having a predictor (feature) is represented by . and and are, respectively, the class probability and the predictor probability of having class and the prior probability of predictor [27,28,29].

3.3.5. Random Forest (RF)

Random Forest (RF) is an ensemble of decision trees. The final output is obtained by majority voting (classification) or averaging (regression) [30,31,32,33]. Equation (7) is the formula for calculating the output of the Random Forest model for the given input feature vector.

In Equation (7), shows the number of trees, and also shows the forecast provided by the tree [33].

3.3.6. Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost)

Since its introduction by Tianqi Chen and Carlos Guestrin in 2016, XGBoost has been continuously improved [34]. In this algorithm, weights are assigned to features and fed into decision trees. Misclassified variables have their weights increased and are passed to subsequent trees, aggregating individual predictors for a more accurate model [35]. Equation (8) shows the predicted values .

where is the hypothesis space and is a weak learner. represents the number of weak learners. is the prediction score of each leaf node after entering [34,36,37].

3.3.7. ANOVA

Using feature selection algorithms is a suitable solution for saving execution time and computing resources and improving prediction results [38]. ANOVA is used to compare the mean values of several groups. In other words, this method is used to check the existence of a significant difference between the average values of several classes [39]. For Equation (9), which shows how to calculate the variance between classes, and are, respectively, the average number of observations in the class and the average of all observations, and is the number of observations in the class [40].

3.3.8. Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP)

SHAP explains how machine learning models make predictions based on game theory. It evaluates the contribution of each feature to the model output [41,42,43]. The explanatory model in the case of a model with a number of input variables and simplified input for the main model is expressed as Equation (10).

In Equation (10), represents a fixed amount, and represents the number of input properties. specifies whether the properties are considered or not. The and inputs are linked by a nine-point function, [40,44,45].

3.4. Proposed Method

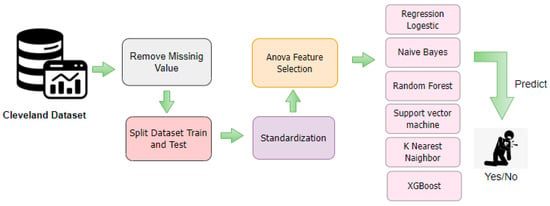

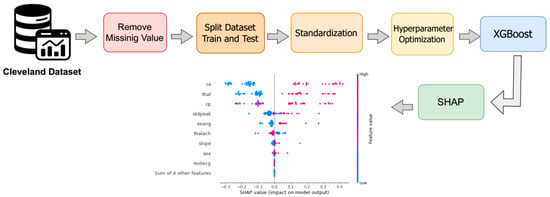

After preparing the data, the algorithms introduced in Section 3.2, along with the ANOVA feature selection method, were applied to the dataset obtained in the previous steps. Figure 3 provides an overview of the proposed method.

Figure 3.

Detailed workflow of the proposed coronary artery disease (CAD) prediction model. The framework starts with data cleaning by removing missing values, followed by dataset splitting and standardization. ANOVA-based feature selection identifies the most significant attributes, which are then used to train multiple classifiers including Logistic Regression, Naïve Bayes, Random Forest, SVM, KNN, and XGBoost.

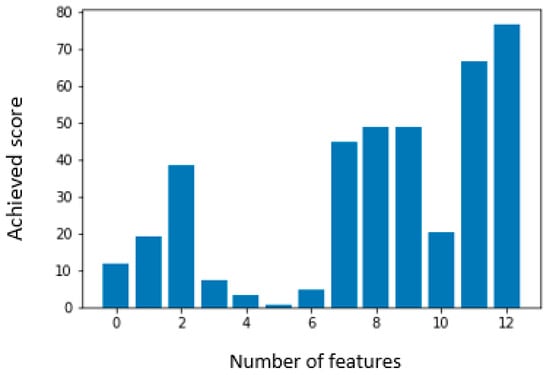

For training and evaluation, the dataset was split into training and testing subsets with an 80:20 ratio, meaning 80% of the data was used for training and 20% for testing. Figure 4 shows the feature importance scores calculated using the ANOVA method. ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) helps identify which features contribute most significantly to predicting the target variable.

Figure 4.

Feature selection using the ANOVA method on the Cleveland dataset. The chart ranks features by F-value, highlighting chest pain type (cp), maximum heart rate (thalach), ST depression (oldpeak), and exercise-induced angina (exang) as the most significant predictors of heart disease.

In this study, a minimum of four and a maximum of thirteen features were selected based on their statistical significance, as specified in Table S1 of the Supplementary Section. Among these features, heart condition (Thal) achieved the highest F-score, indicating the strongest predictive power for heart disease, while fasting blood sugar (FBS) received the lowest score, suggesting a relatively minor contribution. After selecting the most relevant features, the dataset was used to train machine learning algorithms. The hyperparameters of the models were manually tuned using a trial-and-error approach due to computational constraints. Despite its simplicity, this method yielded satisfactory performance. Model performance was evaluated using accuracy, recall, precision, and F1-score.

Table 2 shows the parameters used for each model. Default parameters are used for any models or parameters not listed in the table.

Table 2.

Parameter setting for machine learning algorithms.

Table 2 presents the parameters used for each model. For models or parameters not listed in the table, default values were applied. In the first approach, the accuracy of the algorithms was improved using the ANOVA feature selection method, and the results of this approach will be discussed in Section 4. In the second approach, the XGBoost algorithm was implemented in two ways. In the first way, as mentioned, the algorithm was applied to the features selected by the ANOVA method. In the second way, the hyperparameters of the XGBoost model were tuned, and the model’s performance on the dataset was evaluated. Afterwards, the SHAP algorithm was applied to the output. The implementation process of this approach is illustrated in Figure 5. The hyperparameters of the XGBoost model were manually tuned using a trial-and-error approach due to computational and time constraints. Despite the simplicity of this method, it yielded satisfactory performance, and the optimized parameters are presented in Table 3. The results obtained from this approach will also be discussed in Section 4.

Figure 5.

Workflow of the proposed second approach using the XGBoost model on the Cleveland Coronary Heart Disease dataset. The process includes handling missing values, data splitting and standardization, tuning XGBoost hyperparameters, model execution, and applying SHAP for result interpretation.

Table 3.

Parameter setting for XGBoost.

4. Results and Discussion

In this section, the results of training and evaluating the proposed methods described in Section 3.4 are presented, and the performance of each model is analyzed. The models were compared using the evaluation metrics accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, and the effect of feature selection using the ANOVA method was also investigated. Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, and Table 7, respectively, show the results of the four evaluation criteria accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score for the considered algorithms with the features selected by the ANOVA method. Table 2 presents the parameters used for each model. In the mentioned tables, the letter K represents the number of neighbors in the K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) algorithm.

Table 4.

Accuracy results of the first proposed method evaluated with feature subsets selected using the ANOVA approach, across 4 to 13 features. The results indicate that model accuracy generally improves with the number of selected features, reaching the highest value of 0.9333 for the KNN model (K = 3) with 10 selected features. Bold values indicate the best performance.

Table 5.

Recall results of the first proposed method with ANOVA-based feature subsets ranging from 4 to 13 features. The results reveal that recall generally improves with feature expansion, with the highest sensitivity (0.9166) obtained for Logistic Regression and Naïve Bayes when more than eight features are used. Bold values indicate the best performance.

Table 6.

Precision results of the first proposed method using the ANOVA-based feature selection with 4 to 13 selected features. The precision values show that most models maintain a relatively stable performance, while the KNN (K = 3) and Naïve Bayes models achieve the highest precision (0.9166) with 9 and 10 features, respectively. Bold values indicate the best performance.

Table 7.

F1-score results of the first proposed method based on the ANOVA feature selection with 4 to 13 selected features. The F1-score values remain consistent across models, reaching the highest value of 0.9230 for the KNN model (K = 3) with 10 selected features. Bold values indicate the best performance.

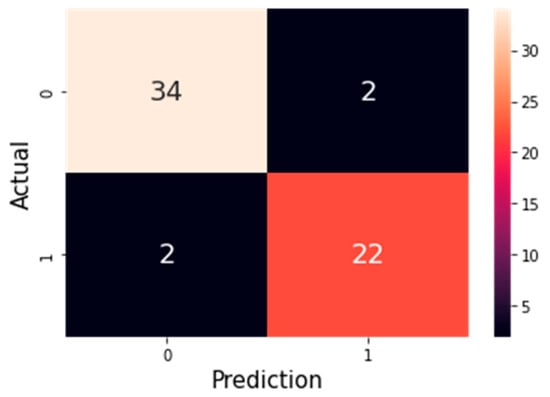

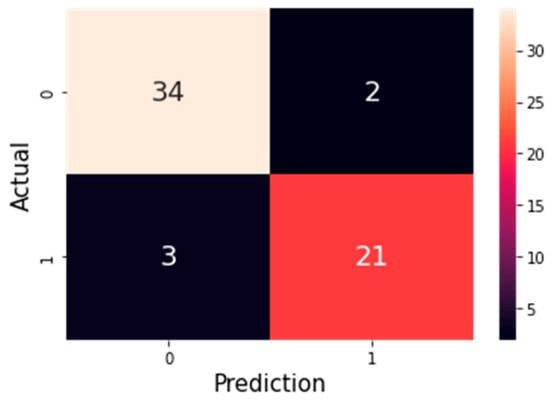

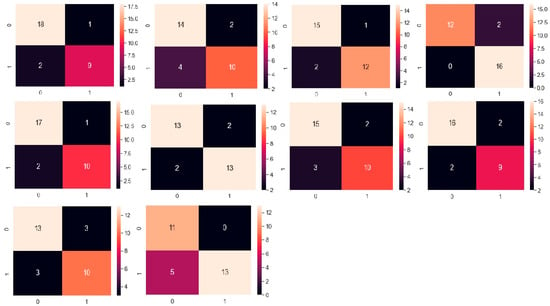

The confusion matrix for the two algorithms K-Nearest Neighbor and the support vector machine, which has the highest accuracy, is shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7. According to Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7, the overall performance of the models generally improves with an increasing number of selected features. The highest accuracy was achieved by the K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) model with K = 3 and 10 selected features, reaching 0.9333. The accuracy of the other evaluated models also shows an upward or stable trend with increasing features, although minor fluctuations are observed. The highest recall (0.9166) was obtained by Logistic Regression and Naïve Bayes when more than eight features were selected, while KNN with K = 3 also demonstrated high recall with 10 features. These results highlight the critical role of selecting an appropriate number of features in optimizing model accuracy and correctly identifying positive cases. The highest precision values were observed for KNN (K = 3) with 8 features and Naïve Bayes with 13 features (0.9166), indicating that in addition to the number of features, the choice of model is also important for maintaining a balance between positive predictions and actual positive instances. The highest F1-score (0.9166) was achieved by KNN (K = 3) with 10 features, emphasizing that KNN with an optimal number of features can effectively balance both precision and recall.

Figure 6.

Confusion matrix of the K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) model with 9 selected features using the ANOVA method. The value 0 represents healthy (non-disease) cases, and 1 represents patients diagnosed with heart disease. The matrix shows that the model correctly identified 34 healthy individuals and 22 patients, while only 2 samples in each class were misclassified.

Figure 7.

Confusion matrix of the Support Vector Machine (SVM) model with 9 selected features using the ANOVA method. In this matrix, 0 represents non-disease (healthy) cases and 1 represents patients with heart disease. The model correctly classified 34 healthy cases and 21 patients, while 3 healthy cases were misclassified as patients and 2 patients were misclassified as healthy.

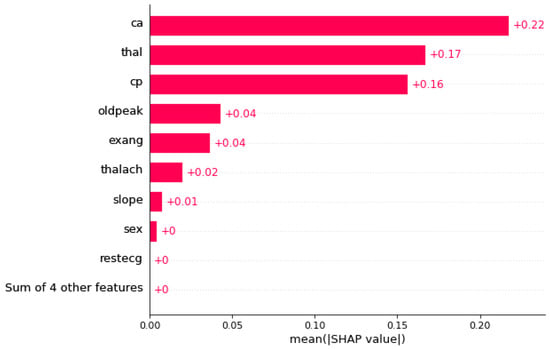

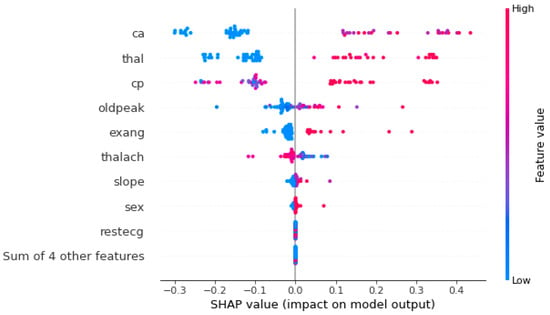

The SHAP algorithm was applied to the output of the constructed model. Figure 8 illustrates the feature importance. The length of each bar represents the overall impact of the feature on the model’s prediction. In this plot, the most important features are listed in descending order. Features with higher bars contribute more to the model’s decision-making and can help identify key factors related to heart disease, thus possessing high predictive power. In this diagram, the features number of major vessels colored by fluoroscopy (Ca), heart condition (Thal) and chest pain (Cp) have the greatest effect on the output. Figure 8 shows the corresponding Beeswarm plot.

Figure 8.

SHAP feature importance bar plot for the XGBoost model applied to the Cleveland Coronary Heart Disease dataset. The length of each bar represents the overall impact of a feature on the model’s predictions. As shown, the features Ca, Thal, and Cp have the highest influence on the model’s decision-making and are the most important for predicting the presence of heart disease.

Each point in Figure 9 summarizes a Shapley value for one feature and one data instance, indicating both the magnitude and direction of the feature’s impact on the model’s prediction. The color of each point represents the actual value of the feature in that instance (higher values in red and lower values in blue). According to Figure 8, the feature Ca, which represents the number of major vessels, has the strongest effect on the model’s output. As shown, higher values of this feature increase the probability of heart disease. The heart condition (Thal) and chest pain (Cp) features follow in importance. Like Ca, higher values of these features increase the likelihood of heart disease, while lower values decrease it.

Figure 9.

Beeswarm plot of SHAP values for the XGBoost model applied to the Cleveland Coronary Heart Disease dataset. Each point represents the SHAP value of a feature for an individual sample, indicating both the magnitude and direction of its effect on the model output. Features such as Ca, Thal, and Cp show the highest contribution to the prediction of heart disease presence, demonstrating their strong influence on the model’s decision-making process.

By examining the results obtained in SHAP and the Pearson correlation diagram in Figure 2 and the scores obtained for each feature by the ANOVA method, it can be seen that the results are completely consistent with each other.

The results of implementing the basic algorithms, along with the ANOVA feature selection method and the ten-fold cross-validation technique, are presented in Table 8, Table 9, Table 10 and Table 11. In this section, the value of K was set to 7, as it yielded the best results compared to other K values. Furthermore, the stability of the model’s performance across different folds was examined to ensure the reliability of the obtained results. The average accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score were calculated for each algorithm to provide a more comprehensive comparison. Overall, these analyses helped confirm the robustness and consistency of the proposed approach.

Table 8.

Accuracy of the basic classification models (LR, NB, RF, SVM, and KNN) using the ANOVA feature selection method with ten-fold cross-validation. The table shows how accuracy varies with different numbers of selected features (from 4 to 13), highlighting the models’ performance trends and indicating that some models achieve higher stability and accuracy with a specific number of features.

Table 9.

Recall of the basic classification models (LR, NB, RF, SVM, and KNN) using the ANOVA feature selection method with ten-fold cross-validation. This table shows how recall varies with different numbers of selected features (from 4 to 13) and highlights each model’s ability to correctly identify positive cases.

Table 10.

Precision of the basic classification models (LR, NB, RF, SVM, and KNN) using the ANOVA feature selection method with ten-fold cross-validation. The table illustrates how precision varies across different numbers of selected features (from 4 to 13), highlighting each model’s ability to correctly identify positive predictions.

Table 11.

F1-score of the basic classification models (LR, NB, RF, SVM, and KNN) using the ANOVA feature selection method with ten-fold cross-validation. The table shows how the F1-score varies across different numbers of selected features (from 4 to 13), reflecting the balance between precision and recall for each model.

According to Table 8, the Logistic Regression model with 13 features was able to obtain the best accuracy and the Naïve Bayes model obtained the lowest accuracy with 79.83%. The highest accuracy, recall, and F1-score were obtained by K-Nearest Neighbor models with 8 features, support vector machines with 13 features, and Logistic Regression with 13 features, with values of 82%, 86.21%, and 83.10%, respectively. The results presented in Table 8, Table 9, Table 10 and Table 11 emphasize the importance of selecting an appropriate number of features and their optimal combination to enhance model performance. They demonstrate that the proposed method using ANOVA can optimize key evaluation metrics and deliver stable performance.

When evaluating the XGBoost model using the 10-fold cross-validation technique, the model parameters were re-tuned. The values of these parameters are presented in Table 12, and the results of the model execution are shown in Table 13.

Table 12.

Hyperparameter settings used for the XGBoost model during evaluation. The table lists each parameter along with its corresponding value, which were adjusted to optimize the model performance under the ten-fold cross-validation scheme.

Table 13.

Performance metrics of the XGBoost model evaluated using the 10-fold cross-validation technique. The table summarizes evaluation measures including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score to provide a comprehensive view of the model’s performance.

According to Table 13, the accuracy increases to 86.16%. In addition to accuracy, the recall criteria and F1-score increased to 87/41% and 84.18%, respectively, which is higher than all the models that have been investigated by this method. The improvement in accuracy, recall, and F1-score compared to other models indicates that this approach is highly effective for identifying positive samples and making precise predictions.

Figure 10 shows the confusion matrix of the XGBoost model with hyperparameter setting and the 10-fold cross-validation technique. The proposed method in this paper was compared with other articles that used the same dataset.

Figure 10.

Confusion matrix of the XGBoost model evaluated using the 10-fold cross-validation technique. The matrix illustrates the number of true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives, providing a detailed view of the model’s classification performance.

In Table 14, the methods proposed in this paper are compared with other articles that used the same dataset as this paper, and the observations show that the methods proposed in this article are better. The proposed model achieved higher accuracy and stability compared to previously published approaches. This improvement demonstrates the effectiveness of the applied feature selection techniques and the interpretability of the developed model in heart disease prediction.

Table 14.

Comparison of the method proposed in this paper with the reviewed articles.

Computational Cost and Interpretability Review

The proposed framework for diagnosing coronary artery disease (CAD) combines multiple machine learning algorithms with the ANOVA feature selection method. This approach reduces data dimensionality, thereby lowering computational cost and accelerating model training. Furthermore, by applying the SHAP algorithm to complex models such as XGBoost, the model predictions become interpretable, allowing the rationale behind decisions to be understood. Overall, the proposed method achieves an effective balance between predictive accuracy, computational efficiency, and clinical interpretability.

5. Conclusions

As mentioned earlier, heart disease is one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide; therefore, its accurate and early diagnosis can save many lives. In this study, an intelligent system was designed to accurately detect heart disease using patients’ medical records and simple, low-cost clinical tests. To enhance model performance, several machine learning algorithms—including Logistic Regression (LR), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and other methods—were applied to the features selected by the ANOVA feature selection technique. The dataset was also divided and evaluated using the hold-out validation method.

To improve model interpretability, the SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) algorithm was applied to the output of the XGBoost model. The resulting SHAP plots effectively illustrated the impact of each feature on the model’s final predictions. In this study, interpretability was assessed solely using SHAP, which provides a comprehensive and theoretically grounded framework for quantifying the contribution of each feature to the model’s output. Although SHAP enhances model transparency, it does not alter predictive performance; therefore, the claim of improved interpretability is based on SHAP’s explanatory power, not on any change in accuracy. Future studies may explore multiple interpretability techniques, conduct comparative analyses of their explanations, and validate SHAP-derived insights with clinical expertise to ensure alignment with domain knowledge. In the proposed approach, the K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) algorithm achieved the highest accuracy of 93.33%, while under 10-fold cross-validation, the XGBoost model also demonstrated promising results with an accuracy of 86.16% and a recall of 87.41%.

Overall, employing ANOVA-based feature selection and SHAP-based interpretability significantly improved both the predictive performance and decision transparency of the models. The primary objective of this study was to develop and evaluate an integrated, application-oriented framework for heart disease prediction. By combining ANOVA-based feature selection with SHAP interpretability, the framework enhances both predictive accuracy and model transparency, while demonstrating the practical benefits of leveraging established techniques in clinical decision support systems. Accordingly, the main contribution of this work lies in the applied use of explainable AI to improve performance and interpretability, rather than in methodological innovation. These results indicate that combining feature selection techniques with interpretable models not only enhances diagnostic accuracy but also increases clinical trust in intelligent decision support systems. However, one of the limitations of the present study is the relatively small size of the Cleveland dataset (303 samples), which may restrict the generalizability of the model to larger and more diverse populations. Although 10-fold cross-validation provides a reliable estimate of model performance, external validation on other datasets is necessary to assess true generalizability. In future studies, we plan to test the proposed approach on larger and more diverse datasets and, where possible, integrate data from multiple sources to better evaluate the robustness and applicability of the model in real-world clinical settings.

Due to the relatively small sample size and the potential for violation of statistical assumptions, formal statistical tests were not performed in this study. However, 10-fold cross-validation and repeated evaluations provide reasonable confidence in the reliability of the results, indicating that the observed improvements, such as the approximately 2% higher accuracy of XGBoost + ANOVA compared to baseline XGBoost, reflect genuine performance differences. In future studies, we plan to perform appropriate statistical tests or report the variance across repetitions to validate these results more rigorously.

Although the hyperparameters in this study were tuned manually and the models achieved satisfactory performance, this approach does not guarantee obtaining the optimal configuration. For future research, it is recommended to use Bayesian Optimization and Grid Search for hyperparameter tuning and to explore more advanced feature selection methods to further improve the diagnostic accuracy and computational efficiency of the models.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/a18120771/s1, Table S1: List of selected features for different numbers of features used in model training.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.E. and H.N.; methodology, H.A., S.E. and H.N.; software, H.A.; validation, H.A., S.E. and H.N.; writing—original draft, H.A., S.E. and H.N.; writing—review and editing, H.A., S.E. and H.N.; visualization, H.A.; supervision, S.E. and H.N.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this study is publicly available from the UCI Machine Learning Repository at: https://archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/45/heart+disease (accessed on 1 December 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ramalingam, V.V.; Dandapath, A.; Raja, M.K. Heart disease prediction using machine learning techniques: A survey. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7, 684–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, J.; Kundu, S. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) and its associated risk factors among older adults in India: Evidence from LASI Wave 1. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2022, 13, 100937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- Ali, F.; El-Sappagh, S.; Islam, S.R.; Kwak, D.; Ali, A.; Imran, M.; Kwak, K.S. A smart healthcare monitoring system for heart disease prediction based on ensemble deep learning and feature fusion. Inf. Fusion 2020, 63, 208–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.M.; Paul, B.K.; Ahmed, K.; Bui, F.M.; Quinn, J.M.; Moni, M.A. Heart disease prediction using supervised machine learning algorithms: Performance analysis and comparison. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 136, 104672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitha, S.; Sridevi, N. Heart disease prediction using data mining techniques. J. Anal. Comput. 2019, 13, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi, A.K. Performance evaluation of different machine learning techniques for prediction of heart disease. Neural Comput. Appl. 2018, 29, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Taie, R.R.K.; Saleh, B.J.; Saedi, A.Y.F.; Salman, L.A. Analysis of WEKA data mining algorithms Bayes net, random forest, MLP and SMO for heart disease prediction system: A case study in Iraq. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2021, 11, 5229. [Google Scholar]

- Pouriyeh, S.; Vahid, S.; Sannino, G.; De Pietro, G.; Arabnia, H.; Gutierrez, J. A comprehensive investigation and comparison of machine learning techniques in the domain of heart disease. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC), Heraklion, Greece, 3–6 July 2017; pp. 204–207. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.; Khan, A.; Khan, M.M.; Farid, K.; Alam, M.M.; Su’ud, M.B.M. Cardiovascular and Diabetes Diseases Classification Using Ensemble Stacking Classifiers with SVM as a Meta Classifier. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavitha, M.; Gnaneswar, G.; Dinesh, R.; Sai, Y.R.; Suraj, R.S. Heart disease prediction using hybrid machine learning model. In Proceedings of the 2021 6th International Conference on Inventive Computation Technologies (ICICT), Coimbatore, India, 20–22 January 2021; pp. 1329–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.M.; Khurshid, S.; Fatema, K.; Hasan, M.Z.; Kamal Hossain, M. Analysis and Prediction of Heart Disease Using Machine Learning and Data Mining Techniques. Can. J. Med. 2021, 3, 36–44. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, D.; Patel, S.; Bharti, S.K. Heart disease prediction using machine learning techniques. SN Comput. Sci. 2020, 1, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishaq, A.; Sadiq, S.; Umer, M.; Ullah, S.; Mirjalili, S.; Rupapara, V.; Nappi, M. Improving the prediction of heart failure patients’ survival using SMOTE and effective data mining techniques. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 39707–39716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, G.T.; Reddy, M.P.K.; Lakshmanna, K.; Rajput, D.S.; Kaluri, R.; Srivastava, G. Hybrid genetic algorithm and a fuzzy logic classifier for heart disease diagnosis. Evol. Intell. 2020, 13, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, U.A.; Muhammad, S.A. Enhancing the Performance of Heart Disease Prediction from Collecting Cleveland Heart Dataset using Bayesian Network. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. 2022, 26, 1093–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UCI Repository. Available online: https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/datasets/heart+disease (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthaharan, S.; Suthaharan, S. Support vector machine. In Machine Learning Models and Algorithms for Big Data Classification: Thinking with Examples for Effective Learning; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 207–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Jia, L. Research on SVM environment performance of parallel computing based on large dataset of machine learning. J. Supercomput. 2019, 75, 5966–5983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binbusayyis, A.; Alaskar, H.; Vaiyapuri, T.; Dinesh, M. An investigation and comparison of machine learning approaches for intrusion detection in IoMT network. J. Supercomput. 2022, 78, 17403–17422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hajjar, A.L.N.; Al-Qurabat, A.K.M. An overview of machine learning methods in enabling IoMT-based epileptic seizure detection. J. Supercomput. 2023, 79, 16017–16064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes, J.; Garcia-Lamont, F.; Rodríguez-Mazahua, L.; Lopez, A. A comprehensive survey on support vector machine classification: Applications, challenges, and trends. Neurocomputing 2020, 408, 189–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaValley, M.P. Logistic regression. Circulation 2008, 117, 2395–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasteski, V. An overview of the supervised machine learning methods. Horizons B 2017, 4, 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, T.M. Machine Learning; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mahesh, B. Machine learning algorithms-a review. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2020, 9, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackins, V.; Vimal, S.; Kaliappan, M.; Lee, M.Y. AI-based smart prediction of clinical disease using random forest classifier and Naive Bayes. J. Supercomput. 2021, 77, 5198–5219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Moon, J.; Naeem, H.; Jabbar, S. Explainable artificial intelligence approach in combating real-time surveillance of COVID19 pandemic from CT scan and X-ray images using ensemble model. J. Supercomput. 2022, 78, 19246–19271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabha, A.; Yadav, J.; Rani, A.; Singh, V. Design of intelligent diabetes mellitus detection system using hybrid feature selection based XGBoost classifier. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 136, 104664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewole, K.S.; Han, T.; Wu, W.; Song, H.; Sangaiah, A.K. Twitter spam account detection based on clustering and classification methods. J. Supercomput. 2020, 76, 4802–4837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzipour, A.; Elmi, R.; Nasiri, H. Detection of Monkeypox cases based on symptoms using XGBoost and Shapley additive explanations methods. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasniya, M.R.; Sheikholeslamzadeh, S.A.; Nasiri, H.; Emami, S. Classification of breast tumors based on histopathology images using deep features and ensemble of gradient boosting methods. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2022, 103, 108382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, A.; Zhang, H.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J.; Fan, D.; Chen, P.; Wang, B. Developing computational model to predict protein-protein interaction sites based on the XGBoost algorithm. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, A.; Raahemi, M.; Nasiri, H. Breast cancer diagnosis from histopathology images using deep neural network and XGBoost. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2023, 86, 105152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennasar, M.; Hicks, Y.; Setchi, R. Feature selection using joint mutual information maximization. Expert Syst. Appl. 2015, 42, 8520–8532. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, M.; Rath, N.K.; Swain, A.; Rath, S.K. Feature selection and classification of microarray data using MapReduce based ANOVA and K-nearest neighbor. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 54, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.J.; Synovec, R.E. Pattern recognition of jet fuels: Comprehensive GC× GC with ANOVA-based feature selection and principal component analysis. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2002, 60, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangalathu, S.; Hwang, S.H.; Jeon, J.S. Failure mode and effects analysis of RC members based on machine-learning-based SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) approach. Eng. Struct. 2020, 219, 110927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 4768–4777. [Google Scholar]

- Parsa, A.B.; Movahedi, A.; Taghipour, H.; Derrible, S.; Mohammadian, A.K. Toward safer highways, application of XGBoost and SHAP for real-time accident detection and feature analysis. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2020, 136, 105405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatahi, R.; Nasiri, H.; Homafar, A.; Khosravi, R.; Siavoshi, H.; Chehreh Chelgani, S. Modeling operational cement rotary kiln variables with explainable artificial intelligence methods—A “conscious lab” development. Part. Sci. Technol. 2023, 41, 715–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Sultana, M.; Bhattacharya, S.; Sengupta, D.; De, D. XAI–reduct: Accuracy preservation despite dimensionality reduction for heart disease classification using explainable AI. J. Supercomput. 2023, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).