Abstract

The synergy between continuum robots and visual inspection technology provides an efficient automated solution for aero-engine blade defect detection. However, flexible end-effector instability and complex internal illumination conditions cause defect image blurring and defect feature loss, leading existing detection methods to fail in simultaneously achieving both high-precision and high-speed requirements. To address this, this study proposes the real-time defect detection algorithm FDC-YOLO, enabling precise and efficient identification of blurred defects. We design the dynamic subtractive attention sampling module (DSAS) to dynamically compensate for information discrepancies during sampling, which reduces critical information loss caused by multi-scale feature fusion. We design a high-frequency information processing module (HFM) to enhance defect feature representation in the frequency domain, which significantly improves the visibility of defect regions while mitigating blur-induced noise interference. Additionally, we design a classification domain detection head (CDH) to focus on domain-invariant features across categories. Finally, FDC-YOLO achieves 7.9% and 3.5% mAP improvements on the aero-engine blade defect dataset and low-resolution NEU-DET dataset, respectively, with only 2.68 M parameters and 7.0G FLOPs. These results validate the algorithm’s generalizability in addressing low-accuracy issues across diverse blur artifacts in defect detection. Furthermore, this algorithm is combined with the tensegrity continuum robot to jointly construct an automatic defect detection system for aircraft engines, providing an efficient and reliable innovative solution to the problem of internal damage detection in engines.

1. Introduction

Aero engines possess highly complex internal structures. During prolonged operation, engine blades and internal components may develop surface defects due to material fatigue, corrosion, or mechanical wear. If these defects are not detected and addressed in a timely manner, they can lead to performance degradation, production interruptions, or even serious safety incidents. Notably, damage to engine blades is one of the critical factors contributing to in-flight aircraft accidents [1]. Therefore, the efficient and accurate detection of engine blade defects is of paramount importance.

In situ inspection technology serves as a critical damage detection method within the maintenance processes of aero-engines, valued for its rapidity and convenience. The core advantage of this technology lies in its ability to inspect internal structures, such as blades, without necessitating the disassembly of the engine itself, thereby significantly enhancing maintenance efficiency [2]. Among these, industrial endoscopic inspection, as the most commonly used visual nondestructive testing method, performs visual inspections inside engines through manual operation [3,4]. Because the shape of an endoscope is passively altered according to surrounding contact, its detection range is limited and it is difficult to traverse multi-stage blades for inspection [5]. The development of slender continuum robot technology provides a more flexible and efficient solution for detecting internal defects in engines. Zhong et al. [5] proposed an innovative continuum robotic arm with a push-pull multi-segment structure, which significantly enhances flexibility and controllability in narrow spaces by combining ultra-fine tendon-driven design with real-time decoupling motion control algorithms. This provides an efficient alternative to industrial endoscopes for in situ inspection of multi-stage blades in aero-engines. Dong et al. [6] developed a 25-degree-of-freedom ultra-fine continuum robotic system based on a spool-feed mechanism, offering the first low-invasive maintenance solution with in situ machining capability for aero-engine low-pressure compressors.

In the process of using a tensegrity continuum robot for internal engine defect detection, new challenges persist: instability in the motion of the robot’s flexible end effector, movement during the detection process, and abnormal lighting conditions caused by the robot’s end effector illumination in the complex environment inside the engine (such as localized overexposure or underexposure). These factors collectively contribute to the blurring of defect images, specifically manifested as motion blur, overexposure blur, or underexposure blur. Such blurring effects result in the loss of defect feature information, thereby affecting the precision of defect measurement.

Although deep learning-based object recognition algorithms have achieved remarkable success in detecting damage on engine blades and other aerospace components [7], they still face substantial challenges when processing images containing the aforementioned defect blur. The resultant feature loss causes a significant drop in detection accuracy for lightweight models, while high-accuracy large models struggle to meet the stringent timeliness requirements for real-time detection. To overcome these limitations, this study proposes an innovative lightweight damage detection algorithm. This method integrates features from both the frequency domain and the spatial domain and introduces a Dynamic Subtraction Sampling Module to significantly mitigate information loss during the feature sampling process. Concurrently, this research constructs an engine blade damage detection system based on a tensegrity continuum robot. The ultimate goal is to achieve highly efficient, precise, and automated detection of damage on aero-engine blades. The specific improvements made are as follows:

- We propose a Dynamic Subtraction Attention Sampling Module (DSAS) to replace the original sampling module in the neck structure. Using the features of the target sampling structure as a reference, attention feature extraction is performed. During the upsampling process, channel masks are designed to extract important channel features for spatial structure expansion. During the downsampling process, spatial mask calculations are applied to extract essential spatial features for spatial structure compression. This design facilitates dynamic compensation in the sampling process by leveraging existing information discrepancies, effectively minimizing the loss of critical defect boundary features during sampling.

- We combined it with Fourier transform to design the High-Frequency Information Processing Module (HFM). The integration of high-frequency feature maps effectively enhances the representation capability of defect regions, providing more salient target features for the subsequent detection model. As a result, it significantly improves the detection performance for defect types characterized by blurred or indistinct features.

- We designed a Classification Domain Detection Head (CDH) aimed at capturing the shared features across different defect categories and extracting domain-specific representations. This module provides additional domain information for categories with fuzzy features or high detection difficulty, enabling object detection guided by domain characteristics. As a result, it improves the overall detection performance across the defect domain.

2. Related Work

2.1. Defect Detection Method Based on Deep Learning

Rapid development of deep learning-based object detection methods has also been applied to the field of defect detection. In recent years, the main detection methods have included CNN-based two-stage and single-stage detection algorithms, as well as Transformer-based methods.

Two-stage detection methods, such as Faster R-CNN [8], first generate candidate bounding boxes using a regional proposal network (RPN) and then classify and refine these bounding boxes using a classifier. Zhang et al. [9] enhanced the detection accuracy of the Faster R-CNN model by fusing detailed low-level features with high-level semantic features, improving the detection performance on a hot-rolled steel strip surface defect dataset. Haiyun et al. [10] employed a multi-level feature fusion network to merge feature maps extracted from VGG-16 into Faster R-CNN, producing fused feature maps with rich positional and semantic information to improve defect detection accuracy. While this method achieves high precision, it is relatively slow due to the multiple computational steps involved. It is particularly suitable for tasks that require precise defect localization, especially in industrial inspection scenarios with complex backgrounds.

With the success of Transformer architectures in the field of natural language processing, Transformer-based detection methods have gradually entered the domain of object detection. In particular, the detector transformer (DETR) framework has undergone extensive research exploration for surface defect inspection applications. Sun et al. [11] introduced DETR to the detection of aircraft engine blade defects and proposed the lightweight SDD-DETR detection model. Mao [12] replaced the BasicBlock module in RT-DETR with the lightweight MobileNetV3 module, improving the detection speed while maintaining precision. Although this method achieves high precision, it is relatively slow as a result of the multiple computational steps involved. It is particularly suitable for tasks that require precise defect localization, especially in industrial inspection scenarios with complex backgrounds.

Single-stage detection algorithms, such as YOLO [13] and Single Shot MultiBox Detector (SSD) [14], significantly improve detection efficiency by directly regressing the target’s location and category information, making them particularly suitable for real-time detection tasks. The YOLO algorithm has been widely deployed in various industrial defect detection scenarios [15], such as metal surfaces, circuit boards, and textiles, leveraging its high detection speed and excellent precision. Yuan et al. [16] proposed an improved YOLOv5-based network named YOLO-HMC, which enhances localization accuracy and contextual semantic aggregation capability in PCB substrate defect detection through the design of a multi-convolutional block attention module and content-aware reassembly of features. Meanwhile, Zifan Cao et al. [17] developed the PRC-Light YOLO model by optimizing YOLOv7’s feature extraction architecture, integrating novel convolutional operators, and refining feature fusion strategies with Receptive Field Blocks (RFB) and content-aware reassembly upsampling, achieving enhanced precision and efficiency in textile defect inspection. These algorithms have undergone iterative optimization processes, accumulating substantial research achievements in industrial defect detection applications.

As an efficient object detection framework, the YOLO algorithm demonstrates unique application potential in industrial defect detection due to its balanced performance in speed and accuracy [18,19], particularly suited to the requirements of continuum robotic dynamic inspection environments. We will further explore the application of the YOLO algorithm in the defect detection of aircraft engines.

2.2. YOLO Algorithm Is Applied to Aero-Engine Surface Defect Detection

Recent research on aero-engine blade defect detection has predominantly focused on deep learning-based in situ inspection methods, with the YOLO series algorithms constituting the most significant research direction. Li et al. [20] developed a coarse-to-fine visual detection framework that optimizes computational efficiency while enhancing accuracy, which has been successfully implemented in multiple aero-engine blade production lines. In subsequent work, Li et al. [21] enhanced YOLOv7 by integrating Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) and Complete Intersection over Union (CIoU) metrics, deploying endoscopic vision systems for automated internal inspection of aircraft engines. Further advancements by Li et al. [22] introduced a modified YOLOv5 architecture incorporating k-means clustering, efficient channel attention network, and bidirectional feature pyramid network modules to improve surface defect detection sensitivity. Recently, Li et al. [23] proposed a YOLOv5 variant utilizing deformable convolutional networks and depthwise separable convolution to detect five critical blade defects: cracks, dents, corrosion, material loss, and thermal barrier coating degradation. Shang et al. [24] extended these efforts through an enhanced Mask R-CNN framework integrating tripartite functionality—damage pattern classification, localization, and segmentation—significantly advancing intelligent endoscopic inspection capabilities.

2.3. Motivation and Novelty

Industrial endoscopes serve as a common tool for in situ inspection of aero engines. As an advanced robotic technology, continuum robots demonstrate significant advantages in the field of in situ aero-engine inspection by leveraging their multi-DOF flexible structures and adaptability to confined spaces. However, during practical application, the inherent end-effector tremor of continuum robots and the complex internal lighting conditions within engines collectively cause blurring in the defect images, leading to insufficient defect detection accuracy. In existing research, many aero-engine defect detection algorithms are based on endoscopic methods and aim to improve the detection sensitivity for surface defects; nevertheless, they fail to address the fundamental challenge of image blur.

Traditional defect detection methods typically adopt a two-stage sequential strategy when processing blurry images: first, an image restoration model (such as De-blurGAN [25] or blind deconvolution methods [26]) is used to recover the image, followed by object detection on the restored image [27]. However, this strategy faces fundamental challenges in industrial defect detection scenarios: General-purpose deblurring models are not designed to preserve defect features; their restoration process may introduce artifacts or smooth out critical defect information; Complex deblurring algorithms struggle to meet the real-time requirements of online industrial inspection.

In contrast to the aforementioned strategies, our proposed FDC-YOLO framework, built upon the YOLO architecture, adopts an integrated blur-resistant detection paradigm. Rather than attempting to explicitly "restore" a clear image, our approach reduces critical information loss during feature fusion by introducing frequency domain information and a cross-domain attention mechanism. This design directly enables the network to extract blur-invariant features from degraded inputs. Consequently, the method avoids time-consuming image preprocessing and potential error propagation, achieving efficient and robust end-to-end detection of defect locations directly from blurry images.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The Overall Framework of the FDC-YOLO

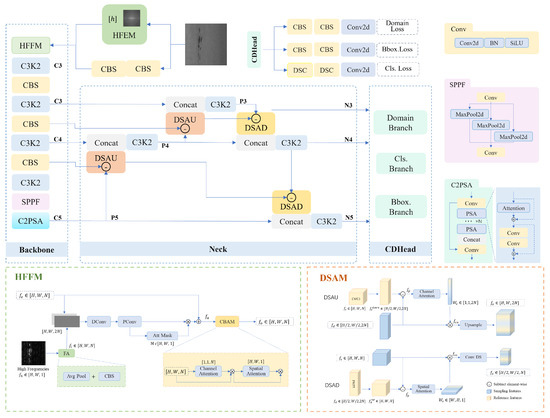

The proposed FDC-YOLO model is based on the YOLOv11 framework and primarily consists of the Backbone, Neck, and Head, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

FDC-YOLO Network architecture.The high-frequency information extraction module (HFEM), high-frequency information fusion Module (HFFM), dynamic subtractive attention sampling module (DSAS) and additional classification domain detection head (CDH) is the model proposed in this paper.

The backbone module includes the C3K2, CBS, SPPF, and C2PSA modules [28,29,30], along with our newly proposed High-Frequency Extraction Module (HFEM) and High-Frequency Fusion Module (HFFM). The C3K2 module, an advanced variant of CSP, enhances feature extraction through a three-layer convolutional configuration. The CBS module integrates convolution, batch normalization, and SiLU activation for better feature discriminability and learning efficiency. The SPPF module improves scale adaptability by capturing multi-scale features. The C2PSA module utilizes self-attention mechanisms to refine multi-level semantic features. Additionally, the HFEM and HFFM modules emphasize high-frequency features, crucial for accurate defect detection.

The Neck component is based on an improved Path Aggregation Network (PANet) [31] architecture, which facilitates multi-level feature fusion through a bidirectional path aggregation mechanism. The bottom-up pathway employs dynamic subtractive attention upsampling (DSAU) to propagate high-level semantic information to lower-level features, while the top-down pathway utilizes dynamic subtractive attention downsampling (DSAD) to transfer low-level detailed information to higher-level features.

The Head section of the model employs a decoupled head design [32], which separates the prediction of different tasks, such as classification, bounding box regression, and objectness score estimation, into distinct sub-heads. On this basis, we add the classification domain sub-heads. Each sub-heads consists of multiple convolution layers and is primarily used for regression on each grid cell to predict the position, category, confidence, and domain probability of the target, mapping the feature map to an output space containing prediction information.

3.2. Dynamic Subtractive Attention Sampling Module (DSAS)

To mitigate the loss of edge features during the sampling process, we propose the Dynamic Subtractive Attention Sampling (DSAS) module, designed to preserve critical feature information more effectively. This module exploits the information discrepancy between the target fused features and the sampled features, selectively retaining and enhancing rare yet essential features.

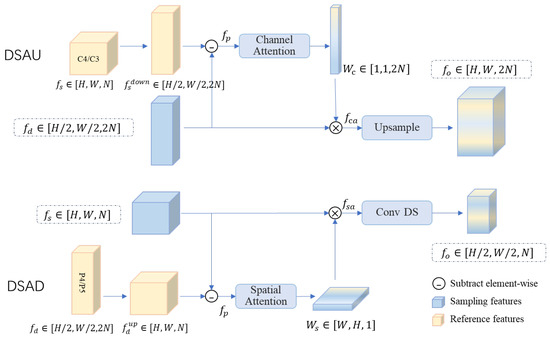

Each layer of the multi-scale input captures distinct characteristics. Shallow features are rich in edge details, textures, and local structural information, while deep features offer a larger receptive field and stronger semantic representation capabilities. The feature pyramid structure within the neck component first progressively upsamples deep features, integrating them with shallow features, and subsequently downsamples the shallow features to generate multi-scale outputs. During the upsampling process of deep features, the focus is on enhancing global information that is inherently lacking in shallow features. Conversely, during the downsampling of shallow features, preserving fine-grained details is prioritized to maintain critical spatial information. Based on this principle, we propose the DSAS module, which consists of the Dynamic Subtractive Attention Upsampling (DSAU) module and the Dynamic Subtractive Attention Downsampling (DSAD) module. The structural design of this module is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the Dynamic Subtractive Attention Sampling (DSAS) module, which performs adaptive feature resampling via upsampling (DSAU) and downsampling (DSAD) paths. and use pre-generated feature layers and do not perform sampling transformations within these modules. : Feature to be upsampled or downsampled. : Sampling reference feature. : Interpolation feature. : Channel attention weight. : Spatial attention weight. : Output feature.

During the progressive upsampling of deep features (e.g., C5) using the DSAU module, shallow features (C4 or C3) serve as reference features. As illustrated in Figure 2, represents the deep features extracted by the backbone network, while denotes the reference features after downsampling (where the reference features are taken from the output of the layer immediately following the feature layer). The difference operation between and generates the difference feature , which encapsulates the semantic disparity between deep and intermediate features. The feature effectively captures the semantic differences, emphasizing the richer global information inherent in high-level features. Given that most contextual semantic information is encoded within the channel dimension, is subsequently processed through a channel attention mechanism to derive the channel attention mask :

The channel attention mechanism is implemented using the Squeeze-and-Excitation block (SE) [33], which explicitly models the inter-channel dependencies within the difference feature. This attention mask quantifies the distribution characteristics of the additional global semantic information captured by deep features in relation to shallow features across different channels. Subsequently, the deep feature is multiplied by the channel attention mask along the channel dimension:

The final output of the module is obtained by rescaling using pooling-based upsampling, ensuring the alignment and fusion of deep semantic information with shallow detail information.

In the top-down pathway enhancement framework of the Neck, we design the DSAD module to perform downsampling. The feature set generated during the progressive upsampling and fusion of deep features C5 is denoted as (P5, P4, P3). Throughout the top-down process, the shallow feature P3 undergoes progressive downsampling, using deeper features (P4, P5) as reference features to generate multi-scale feature maps. As illustrated in Figure 2, represents the shallow features, while denotes the deep features after upsampling. The difference operation between and yields the difference feature . Given that shallow features benefit from higher resolution and thus preserve richer fine-grained details, they exhibit superior spatial feature representation. To fully exploit this advantage, we utilize the spatial relationships within to generate the spatial attention map :

Referring to the spatial attention module in [34], a spatial attention map is generated, aiming to highlight the fine-grained details that are missing in deep features compared to shallow features at the spatial level. Subsequently, the shallow features are element-wise multiplied with the spatial attention map:

The final output of the module is obtained by rescaling using convolutional downsampling, ensuring the alignment and fusion of shallow semantic information with deep feature details.

3.3. High-Frequency Information Processing Module (HFM)

In visual features, defects generally have characteristics that stand out from the background information. While the human eye may not always be able to determine the defect category, it can capture most of the defect locations through this distinguishing feature. In the frequency domain, low-frequency information represents regular distributions, while high-frequency information represents anomalies, making it inherently easier to differentiate between regular backgrounds and abnormalities. Based on the characteristics of defect detection and frequency domain information, this paper applies frequency domain information to the defect detection process.The input part of feature extraction is enhanced with image frequency domain information, emphasizing the high-frequency features of the image. By utilizing high-frequency information, the edge features of defects in the image are strengthened. This results in the extracted features containing richer semantic information about the defects, thereby improving the model’s ability to detect blurred defects.

3.3.1. High-Frequency Information Extraction Module (HFEM)

The Fourier Transform is a widely used technique for converting images from the spatial domain to the frequency domain. To enhance the visibility of defect regions, this study applies a two-dimensional Fourier Transform to decompose the image into low-frequency and high-frequency components. Subsequently, a zero-order Butterworth high-pass filter is employed to attenuate low-frequency components while preserving high-frequency ones, thereby enhancing details and accentuating defect features. The transfer function of this filter is defined in the frequency domain as follows:

In this equation, represents the Euclidean distance from the point in the frequency domain to the center of the frequency plane , whose physical meaning is the radius of the frequency component from the center. is the filter’s cutoff radius, which controls the range of preserved high-frequency components. In implementation, is defined as a learnable parameter h. This parameter is initialized to an empirical value (e.g., 5 pixels) at the start of training and is subsequently optimized via the backpropagation algorithm, allowing the network to automatically learn the cutoff frequency most conducive to defect detection from the data.

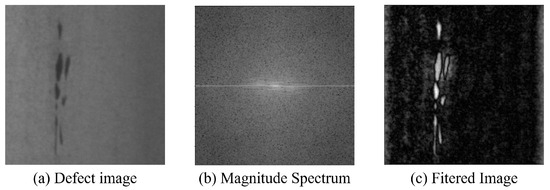

Through the aforementioned fourier transform and high-pass filtering operations, it is possible to effectively eliminate low-frequency interference in the image caused by background or lighting conditions while simultaneously accentuating detailed regions and defect characteristics. The effect diagram after extracting high-frequency features is shown in Figure 3. This preprocessing step aids in enhancing the model’s perceptual ability towards defect regions, demonstrating higher robustness especially in detecting small defects or texture anomalies.

Figure 3.

Renderings of high-frequency features.

3.3.2. High-Frequency Information Fusion Module (HFFM)

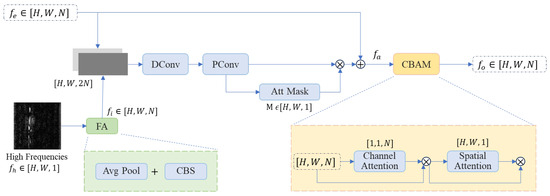

Incorporating high-frequency information directly into the image does not lead to optimal detection performance. As demonstrated through experiments in Section 4.4, integrating high-frequency information at the C2 layer yields the best detection results. To address the challenges of aligning and fusing high-frequency features with image features, we take inspiration from the edge-aware attention module used for segmentation in [35] and propose the High-Frequency Feature Fusion Module (FHFM). The primary goal of FHFM is to enhance the image’s edge information, thereby effectively mitigating the issue of blurred defect boundaries.

The high-frequency information fusion Module has two inputs: the high-frequency feature map obtained from the FHEM module, and the visual feature encoded from the original image. The FHFM module processes the input information and and generates an output feature denoted as . A schematic diagram of the FHFM module is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

High-frequency information fusion module.

The original image undergoes feature extraction and enhancement through two consecutive CBS modules, generating a multi-channel visual feature representation . To ensure effective alignment between the high-frequency feature map and the visual feature encoding , we introduce a feature alignment module (FA). First, the high-frequency feature map is downsampled using average pooling to ensure its spatial dimensions match those of . The advantage of average pooling lies in its ability to effectively preserve global information and spatial distribution characteristics without introducing the potential loss of local features that can occur with max pooling. The downsampled high-frequency feature map is further enhanced at the semantic level through the CBS module, aligning its feature representation capability more closely with the visual feature encoding generated by the CBS module. The FA module addresses the spatial resolution alignment issue while striving to retain the detailed information of the high-frequency feature map, effectively reducing the semantic gap between the high-frequency features and , and minimizing conflicts in the subsequent information fusion process.

By performing a channel concatenation operation to combine the aligned high-frequency features with the visual feature encoding, followed by the Depthwise Separable Convolution strategy for efficient multidimensional feature fusion. First, Depthwise Convolution (DConv) is applied to capture spatial contextual information while reducing the computational complexity of convolution operations. Subsequently, Pointwise Convolution (PConv) is employed to facilitate inter-channel information interaction, effectively integrating feature representations across different dimensions.The final fused feature is denoted as :

The resulting fused feature retains the detailed advantages of high-frequency features and integrates the global semantic information of the visual feature encoding, providing enhanced expressive power for subsequent detection tasks.

Since high-frequency information may include background texture information and superfluous details, an attention mask layer named M is introduced following feature fusion. The purpose of this mask is to guide the model to focus on defect edge information that is beneficial for detection while disregarding background noise and redundant information. The attention feature map is defined as follows:

The attention feature is integrated into the CBAM (Convolutional Block Attention Module) to recalibrate the feature map that incorporates the visual feature , facilitating the capture of feature correlations between boundary and background regions. CBAM consists of two sequential blocks: channel attention, which focuses on the channel dimension, and spatial attention, centered on the spatial dimension. The convolution kernel sizes used for channel attention and spatial attention are and , respectively. The configuration of this module is illustrated in Figure 4. Consequently, this process yields the refined decoded feature :

3.4. Classification Domain Detection Head (CDH)

The concept of a “Domain” is often used to denote a collection of data with specific distributions or characteristics. In defect detection tasks, unlike general object detection, all defect targets belong to a unified “defect domain,” which possesses its unique statistical patterns and representational features. Specifically, defect targets exhibit many common domain features across dimensions such as space, texture, and shape, for example, shape anomalies, local texture differences, and color mutations. These domain features not only help distinguish defect regions from background regions but also provide a basis for modeling defect targets from a global unified perspective.

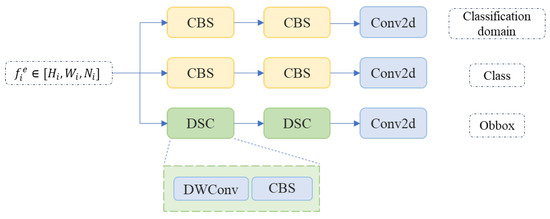

Traditional models’ detection heads overlook the shared features across different categories. To enhance the model’s ability to extract defect domain features, this paper proposes an improved method based on a classification domain head (CDH).We add a classification domain branch to the original decoupled head, with the structure shown in Figure 5. This branch is similar in structure to the classification branch, using a CBS module to filter bias features and an MLP to output domain probabilities, which range between 0 and 1, indicating the likelihood of the predicted box belonging to the defect domain.

Figure 5.

Classification domain detection head.

Simultaneously, domain loss is introduced for backpropagation optimization, guiding the model to focus on the common characteristics of defect classes. The domain loss is calculated using Binary Cross Entropy Loss (BCE Loss), which quantifies the difference between the model’s output domain probability and the true labels.

where the predicted value , the true label , and N is the number of samples. It quantifies the accuracy of the model’s output by calculating the cross-entropy between the predicted values and the true labels. During the training process of this branch, all truly annotated samples are defined as positive samples, with their labels set to 1, indicating that these samples unequivocally belong to the “defect domain”. Conversely, samples that are falsely detected in other processes are considered negative samples.

The classification domain branch encourages the model to focus on domain features, providing more contextual information and reference for recognizing small and blurred defect targets. This enables the detection of more targets within the “defect domain” and reduces the likelihood of false negatives. Therefore, the inclusion of the classification domain branch not only improves detection accuracy but also enhances the model’s robustness in complex environments.

4. Results

4.1. Experimental Environment and Evaluation Indicators

Hardware Configuration Used in the Experiments: The system is equipped with an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3080 Ti GPU. The software configuration includes the Windows 10 operating system, CUDA 10.1 environment, PyTorch 3.8.19 as the learning framework, and Python 3.7 as the programming language. The input image size is 640 × 640, with a batch size of 36 and 200 training epochs. Warm-up training is conducted in the first three epochs, with the learning rate dynamically adjusted via linear interpolation. Subsequently, every ten epochs, the learning rate is reduced to 20% of its original value, with a weight decay of 0.0005 and a momentum of 0.949. During the training process, the official pre-trained weight file is loaded, and automatic mixed precision training is utilized. This method effectively reduces memory usage and accelerates the training speed.

Evaluation metrics: The model’s detection performance is evaluated using standard object detection metrics, including mAP50 and mAP50-95. In addition, precision and recall are employed to assess the accuracy and completeness of defect localization. The model’s size and computational complexity are reflected by the number of parameters and the floating point operations (FLOPs).

4.2. Datasets

4.2.1. Aero-Engine Blade Defect Detection Dataset (AEB-DET)

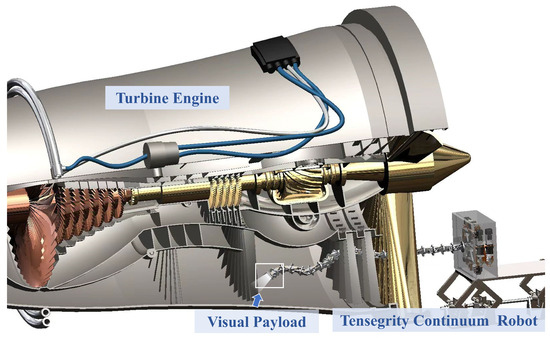

To evaluate the model’s defect detection performance in real-world applications, this study employs a tensioned continuum robot visual inspection system to capture images of defects on aviation engine blades and constructs a corresponding aero-engine blade defect detection (AEB-DET) dataset.

The structure of this visual inspection system is shown in Figure 6, and it primarily consists of two core components: the continuum robot body structure and the visual payload. The optical acquisition module is integrated with a WiFi wireless communication unit and a ring-array lighting system, enabling efficient defect image capture even under low-light conditions.

Figure 6.

The tensegrity continuum robot vision inspection system.

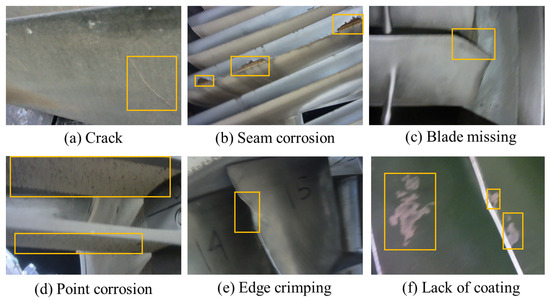

The AEB-DET dataset contains 432 defect images, each with a resolution of 640 × 480 pixels. The distribution of defect types is shown in Table 1. The dataset includes six common types of blade defects: crack, seam corrosion, blade missing, pitting corrosion, edge curling, and lack of coating. To enhance the model’s generalization capability, the images were augmented through rotation, flipping, and scaling. Subsequently, the dataset was split into training and validation sets in an 8:2 ratio. Figure 7 presents example images for each defect category in the dataset.

Table 1.

The distribution of defect types of AEB-DET dataset.

Figure 7.

Typical labeled defects in AEB-DET dataset. The yellow box is the defect annotation box.

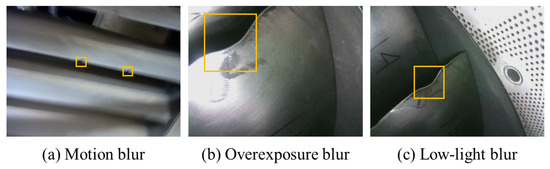

To accurately replicate real-world aero-engine blade inspection scenarios, all defect images were acquired by an imaging payload mounted on a tendon-driven continuum robot during locomotion. The dataset intentionally retains artifacts including motion blur, overexposure blur, and low-light blur (Figure 8), comprehensively representing challenging conditions encountered in practical defect detection applications.

Figure 8.

Three types of blurry images in the AEB-DET dataset. The yellow box is the defect annotation box.

4.2.2. Public Metal Surface Defect Dataset (NEU-DET and GC10-DET)

To validate the advantages of the FDC-YOLO model in metal surface defect detection, we selected the hot-rolled strip steel surface defect detection dataset published by Northeastern University (NEU-DET) [36]. This dataset contains 1800 grayscale images with a resolution of 200 × 200 pixels. The images include six different types of typical surface defects: Cracks (Cr), Pitting Surface (PS), Rolled-in Scales (RS), Patches (Pa), Inclusions (In), and Scratches (Sc), with 300 samples for each defect type. For the defect detection task, annotations are provided, indicating the defect categories and locations in each image.

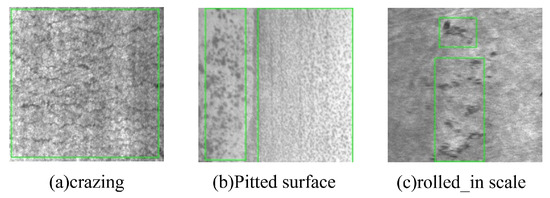

The NEU-DET dataset contains three typical types of blurred feature defects. Additionally, the low image resolution of the dataset exacerbates the blurring of defect boundaries, which can be used to validate the detection performance of the proposed model on defects with blurred features. As shown in Figure 9, the crazing category is characterized by a high degree of overlap between the defects and the background rolling texture, resulting in indistinct defect features. The pitted surface defect consists of irregular, spot-like clusters with no clear clustering boundaries, and the annotation standards are not consistent. The rolled-in scale defect includes characteristics of both the previous defects.

Figure 9.

Three typical fuzzy defects in NEU-DET dataset.

In order to verify the generality of the model, we choose the GC10 defect detection dataset (GC10-DET). The GC10-DET dataset is available on github (Website: https://github.com/lvxiaoming2019/GC10-DET-Metallic-Surface-Defect-Datasets, accessed on 18 December 2024). The GC10-DET dataset is a publicly available dataset focused on steel surface defect detection, containing 10 common types of defects such as crease, water spot, and crescent gap, with a total of approximately 1800 high-resolution images (2048 × 1000), suitable for fine defect detection and analysis. The distribution of sample quantities for defect types in this dataset is very uneven, with the samples for rolled pit and crease defects being the fewest, only one-tenth of the number of silk spot defects.

The two datasets are all divided into training and validation sets at an 8:2 ratio, and data augmentation methods are used to expand the training set to four times its original size. Ultimately, the NEU-DET dataset contains 6120 training images and 270 validation images; the GC10-DET dataset contains 7340 training images and 459 validation images.

4.3. Comparative Experiment

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of different models on defect detection tasks, Table 2 presents the experimental results of the YOLO series algorithms [29,30,37,38,39,40] as well as the Transformer-based object detection method RT-DETR [12] across three datasets: AEB-DET, NEU-DET, and GC10-DET.

Table 2.

Performance comparison on different datasets. -: Owing to the limited size of the AEB-DET dataset, the RT-DETR model failed to achieve applicable performance levels during inference. The bolded parts in the table represent the optimal results.

The YOLO series models, with their end-to-end architectural design, are capable of directly outputting both object categories and locations, achieving a well-balanced trade-off between detection accuracy and model complexity. Among them, the latest version, YOLOv11, demonstrates outstanding performance across all three datasets (mAP@50 scores: AEB-DET: 69.8%, NEU-DET: 78.1%, GC10-DET: 66.0%). It significantly outperforms most existing methods in terms of detection accuracy while maintaining exceptional cost-efficiency with respect to parameter count—adding only 0.01 M parameters compared to the smallest YOLOv5 model.

In contrast, although the YOLOv9e further improve detection accuracy on some metrics (mAP@50 scores: AEB-DET: 71.6%, NEU-DET: 78.8%), their significantly larger parameter sizes and higher computational overhead make them less suitable for industrial applications where real-time performance and resource efficiency are critical. In addition, given that the data size of the three defect datasets is relatively small, the RT-DETR model has not achieved any improvement in detection accuracy. Particularly for the AEB-DET dataset, due to the extremely limited amount of data, the loss function fails to converge effectively during the model training process, ultimately resulting in the inability to obtain practically valuable outcomes.

Notably, the proposed FDC-YOLO model surpasses existing methods in detection performance across all three datasets (mAP@50 scores: AEB-DET: 77.7%, NEU-DET: 81.6%, GC10-DET: 67.9%). Meanwhile, its parameter count is only 3% higher than that of YOLOv11, and it has reduced by 95% compared to YOLOv9e. Therefore, FDC-YOLO achieves an optimal balance between detection accuracy and model complexity, making it highly promising for engineering applications.

To further compare the performance differences between the baseline model YOLOv11 and the proposed FDC-YOLO model across various defect detection tasks, Table 3 presents a detailed comparison of their detection precision (mAP), recall, and mean Average Precision at IoU = 0.50 (mAP@50) for different defect categories on the AEB-DET and NEU-DET datasets.

Table 3.

Comparison of detection performance for various defects on the AEB-DET and NEU-DET.

On the AEB-DET dataset, FDC-YOLO improves the overall mAP@50 by 7.9% compared to YOLOv11, demonstrating a more comprehensive performance advantage in detecting defects on engine blades under complex backgrounds. Particularly for subtle defects such as “Cracking,” FDC-YOLO increases the recall by 7.5%, indicating a stronger capability in perceiving small and ambiguous features. Moreover, for the three defect types with relatively low baseline detection performance—Cracking, Edge Crimping, and Lack of Coating—FDC-YOLO achieves significant mAP improvements of 12.6%, 5.6%, and 16.7%, respectively. This highlights the model’s notable gains when dealing with challenging defect categories.

It is worth noting that the images in the AEB-DET dataset were acquired using a continuum robot, resulting in noticeable image blur, motion artifacts. FDC-YOLO exhibits substantial improvements in detection accuracy across all defect categories within this dataset, further confirming its capability to effectively identify blurry defects. These results highlight the model’s exceptional robustness and practicality in complex industrial applications, particularly in scenarios involving engine blade defect detection using continuum robot vision systems.

On the low-resolution NEU-DET dataset, FDC-YOLO achieves a 3.5% improvement in overall mAP@50 over YOLOv11. For the most challenging defect type, Crazing, FDC-YOLO improves the mAP by 5.3%. In addition, for two other typical blurry defect categories—Pitted Surface and Rolled-in Scale—it achieves gains of 7.9% and 4.4%, respectively. These results suggest that FDC-YOLO possesses a stronger discriminative capability for defects with fuzzy boundaries and high background integration.

In summary, FDC-YOLO outperforms YOLOv11 on both the AEB-DET and NEU-DET datasets, which are representative of real-world conditions. Its particularly notable advantages in detecting difficult and blurry defect types indicate its strong potential for deployment in practical industrial defect detection applications.

4.4. Ablation Experiment

4.4.1. Ablation Experiment on AEB-DET Dataset

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed modules in the task of engine blade defect detection, we conducted a series of ablation studies on the AEB-DET dataset. The experimental results are presented in Table 4. This study focuses on three key modules: the high-frequency information processing module (HFM), the dynamic subtraction attention sampling module (DSAS), and the classification domain detection head (CDH).

Table 4.

Results of ablation experiments on the AEB-DET dataset. The check mark ‘✓’ indicates that the corresponding module is enabled during both model training and testing. The bolded parts in the table represent the optimal results.

First, each of the HFM, DSAS, and CDH modules was independently evaluated. The results show that the inclusion of HFM, DSAS, and CDH individually leads to mAP@50 improvements of 3.6%, 5.5%, and 3.0%, respectively, demonstrating the significant contribution of each module to overall model performance.

Specifically, integrating HFM into the baseline model yields a 3.6% increase in mAP@50, indicating that high-frequency feature enhancement plays a positive role in strengthening defect edge representations. Further adding the DSAS module results in a 6.6% gain in mAP@50 and a 2.5% improvement in mAP@50–95, confirming that dynamic attention-based sampling effectively enhances the localization of blurry defect regions. Finally, incorporating the CDH module introduces domain-specific defect features, enhancing the model’s decoding capability. This leads to the highest observed recall of 78.8% (+8.3), and peak performance in both mAP@50 and mAP@50–95, reaching 77.7% and 37.1%, respectively.

These results strongly validate the effectiveness of the proposed modular design and confirm the rationality of the overall architecture, especially in handling complex and fuzzy defects.

4.4.2. Ablation Experiment on NEU-DET

Table 5 presents the mAP50 results for the six defect types in NEU-DET, demonstrating a progressive enhancement in overall detection accuracy through sequential integration of core modules. The module incorporation culminates in a 3.5% performance improvement over the baseline model. For the defect type with the poorest detection performance, Cracks (Cr), FDC-YOLO achieves a 5.3% higher mAP value compared to the baseline model YOLOv11. For the other two typical fuzzy defects(Ps + 7.9%, Rs + 4.4%), FDC-YOLO model achieves the best detection accuracy. This result suggests that the FDC-YOLO model substantially enhances detection performance for defect types with high background fusion and blurred boundary features.The data in the table demonstrate that FDC-YOLO exhibits improved detection performance for all defect types.

Table 5.

Results of ablation experiments in NEU-DET dataset. Cr, Ps, etc. are abbreviations corresponding to the six defect category names in the NEU-DET dataset described in Section 4.4.2. The check mark ‘✓’ indicates that the corresponding module is enabled during both model training and testing. The bolded parts in the table represent the optimal results.

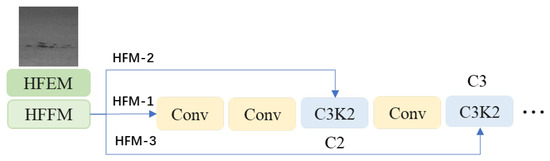

4.4.3. Ablation Experiment of High-Frequency Information Processing Module

We design an ablation experiment to verify the optimal insertion position for high-frequency information. As illustrated in the Figure 10, high-frequency information is introduced at three different locations within the model’s backbone: the input position(HFM1), before the C2 feature layer (HFM2), and before the C3 feature layer(HFM3). We validate the results in NEU-DET dataset, the experimental results are presented in Table 6. The results indicate that introducing high-frequency information before the C2 feature layer (HFM2) maximizes the model’s detection performance.

Figure 10.

Schematic of where high-frequency information is introduced. HFM-n represents n different introduction positions.

Table 6.

Ablation experiment of high-frequency information processing module (HFM). The bolded parts in the table represent the optimal results.

The analysis of the reasons primarily includes the following two aspects: The first aspect is the recognition and utilization of high-frequency information. When high-frequency information is introduced together with the original image at the input stage, subsequent convolution and downsampling modules may not effectively recognize and utilize it. This is because high-frequency details, such as edges and textures, are prone to being smoothed or lost during convolution and downsampling, preventing high-frequency information from fully playing its intended role. The second aspect is the feature alignment issue. If high-frequency information is introduced before a deeper feature layer (such as C3), the original image features have already undergone multiple convolution and downsampling operations, making it difficult to achieve spatial and semantic alignment between high-frequency information and image features. This misalignment not only reduces the effectiveness of high-frequency information but may also introduce noise, thereby affecting the model’s detection performance.

4.4.4. Visualization of Detection Results

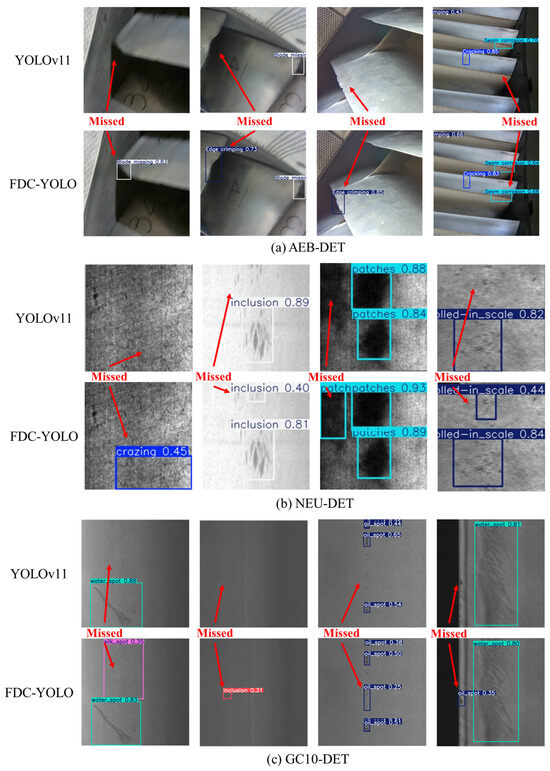

The defects missed by the YOLOv11 model primarily fall into three categories: (1) severe motion blur, which leads to indistinct defect boundaries, (2) high similarity between defects and the background, making them difficult to distinguish using conventional detection models, and (3) small-sized defects with weak local features, which are challenging to extract and recognize effectively. The visual comparison of the detection results of FDC-YOLO and YOLO11 is shown in Figure 11. The visualized detection results across three datasets clearly demonstrate that the proposed FDC-YOLO model successfully identifies defects that YOLOv11 fails to detect.

Figure 11.

Visual comparison of detection results on three data sets.

These characteristics are typical of blurred defect patterns, where YOLOv11 exhibits significant limitations in detection performance. In contrast, FDC-YOLO improves defect detection by optimizing the sampling process, integrating high-frequency information, and enhancing defect-domain features. The model demonstrates robust performance in complex backgrounds and low-contrast conditions, effectively identifying blurred defects. These findings indicate that FDC-YOLO exhibits superior robustness and adaptability for blurred defect detection tasks, significantly outperforming YOLOv11.

5. Conclusions

This paper focuses on defect detection algorithms for blurred images, aiming to address the challenges encountered during aircraft engine inspection using a tensegrity continuum robot. A lightweight network, FDC-YOLO, with anti-blur capabilities is proposed. By incorporating frequency domain information (HFM), defect domain information (CDH), and designing modules to reduce the loss of critical features during the sampling process (DSAS), the proposed method effectively addresses the issues of sparse defect features and critical feature loss in blurred defect images. A tensegrity continuum robot-based engine blade defect detection system is developed, enabling efficient and accurate detection of engine blade defects. In experiments, the model was validated using publicly available datasets and engine defect dataset collected by tensegrity continuum robot. The results show that FDC-YOLO achieves 7.9% and 3.5% mAP improvements on the aero-engine blade defect dataset and low-resolution NEU-DET dataset, respectively, with only 2.68 M parameters and 7.0G FLOPs. This method demonstrates great potential application value in fully automated defect detection within confined spaces of equipment interiors.

Furthermore, concerning the improvement in the Classification Domain Head, this paper also suggests further research directions. We plan to introduce more advanced neural network architectures to explore their effectiveness in open-set recognition, enhancing the model’s generalization ability and enabling it to handle more types of defects and anomalies in more complex environments. These improvements are expected to drive the further development of defect detection technology and provide stronger technological support for industrial automation detection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.X. and G.S.; methodology, X.X.; software, X.X.; validation, X.X., F.L. and C.H.; formal analysis, G.S. and H.P.; investigation, X.X.; resources, G.S. and H.P.; data curation, X.X. and L.X.; writing—original draft preparation, X.X.; writing—review and editing, G.S., Y.Z. and X.X.; visualization, X.X. and C.H.; supervision, G.S. and H.P.; project administration, G.S. and F.L.; funding acquisition, G.S. and H.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Youth Innovation Promotion Association of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant Number Y2023058) and the Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (Grant Number 2025JH6/101100020).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors with to thanks all who supported this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, X.; Romli, F.I.; Azrad, S.; Zhahir, M.A.M. An Overview of Civil Aviation Accidents and Risk Analysis. Proc. Aerosp. Soc. Malays. 2023, 1, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Gail, J.; Kruse, F.; Gu-Stoppel, S.; Schmedemann, O.; Leder, G.; Reinert, W.; Wysocki, L.; Burmeister, N.; Ratzmann, L.; Giese, T.; et al. Advancements in Aircraft Engine Inspection: A MEMS-Based 3D Measuring Borescope. Aerospace 2025, 12, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y. Aero-engine blade detection and tracking using networked borescopes. Int. J. Sens. Netw. 2025, 47, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidzgorska, A. The role of endoscopic inspection in managing the risk of aircraft engine maintenance. J. KONBiN 2024, 54, 111–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Huang, Y.; Hong, D.; Shao, N. Design and Control of an Ultra-Slender Push-Pull Multisection Continuum Manipulator for In-Situ Inspection of Aeroengine. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 14–18 October 2024; pp. 11394–11401. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, X.; Axinte, D.; Palmer, D.; Cobos, S.; Raffles, M.; Rabani, A.; Kell, J. Development of a slender continuum robotic system for on-wing inspection/repair of gas turbine engines. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2017, 44, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Li, H.; Luo, X.; Hu, L.; Yang, R.; Zeng, N. From data analysis to intelligent maintenance: A survey on visual defect detection in aero-engines. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2025, 36, 062001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, S.; Miao, Q.; Fang, R.; Xue, S.; Hu, Q.; Hu, J.; Chan, S. Surface defect detection of hot rolled steel based on multi-scale feature fusion and attention mechanism residual block. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haiyun, W.; Jianping, W.; Fuhua, L. Study on surface defect detection of metal sheet and strip using faster R-CNN with multilevel feature. Mech. Sci. Technol. Aerosp. Eng. 2021, 40, 262–269. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Song, K.; Wen, X.; Wang, Y.; Yan, Y. SDD-DETR: Surface Defect Detection for No-Service Aero-Engine Blades with Detection Transformer. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2024, 22, 6984–6997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Gong, Y. Steel surface defect detection based on the lightweight improved RT-DETR algorithm. J. Real-Time Image Process. 2025, 22, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single shot multibox detector. In Proceedings of the 14th European Conference on Computer Vision—ECCV 2016, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.; Wang, L.; Xu, X.; Su, L.; He, W.; Wang, X. An intelligent fault detection algorithm for power transmission lines based on multi-scale fusion. Intell. Robot. 2025, 5, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Zhou, Y.; Ren, X.; Zhi, H.; Zhang, J.; Chen, H. YOLO-HMC: An improved method for PCB surface defect detection. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 2001611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wang, H.; Cao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Tao, L.; Yang, J.; Zhang, K. PRC-Light YOLO: An efficient lightweight model for fabric defect detection. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Xue, X.; Li, Q.; Gao, H.; Wang, R.; Jiang, R.; Ren, Z.; Meng, R.; Li, M.; Guo, Y.; et al. Pig-ear detection from the thermal infrared image based on improved YOLOv8n. Intell. Robot. 2024, 4, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Q.; Gao, R.; Li, Q.; Wang, R.; Zhang, H. Recognition of the behaviors of dairy cows by an improved YOLO. Intell. Robot. 2024, 4, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Li, Y.; Xie, Q.; Wu, Y.; Yu, Z.; Wang, J. Tiny defect detection in high-resolution aero-engine blade images via a coarse-to-fine framework. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 3512712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yu, J.; Wang, H. Damages detection of aeroengine blades via deep learning algorithms. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 5009111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, C.; Ju, H.; Li, Z. Surface Defect Detection Model for Aero-Engine Components Based on Improved YOLOv5. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, W.; Sun, L.; Hu, B.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, J. Deep learning-based defects detection of certain aero-engine blades and vanes with DDSC-YOLOv5s. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, H.; Sun, C.; Liu, J.; Chen, X.; Yan, R. Deep learning-based borescope image processing for aero-engine blade in-situ damage detection. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2022, 123, 107473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupyn, O.; Martyniuk, T.; Wu, J.; Wang, Z. Deblurgan-v2: Deblurring (orders-of-magnitude) faster and better. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 8878–8887. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.; Yan, Z.; Zhang, K.; Zuo, W.; Zhang, L. Toward convolutional blind denoising of real photographs. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 1712–1722. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Hu, C.; Qian, W.; Wang, Q. RT-Deblur: Real-time image deblurring for object detection. Vis. Comput. 2024, 40, 2873–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Mark Liao, H.Y.; Wu, Y.H.; Chen, P.Y.; Hsieh, J.W.; Yeh, I.H. CSPNet: A New Backbone that can Enhance Learning Capability of CNN. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 1571–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochkovskiy, A.; Wang, C.Y.; Liao, H.Y.M. Yolov4: Optimal speed and accuracy of object detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.10934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M. YOLOv11: An Overview of the Key Architectural Enhancements. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.17725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Qi, L.; Qin, H.; Shi, J.; Jia, J. Path Aggregation Network for Instance Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 8759–8768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.; Liu, S.; Wang, F.; Li, Z.; Sun, J. Yolox: Exceeding yolo series in 2021. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.08430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module. In Proceedings of the 15th European Conference on Computer Vision—ECCV 2018, Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bui, N.T.; Hoang, D.H.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Tran, M.T.; Le, N. Meganet: Multi-scale edge-guided attention network for weak boundary polyp segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2024; pp. 7985–7994. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Song, K.; Meng, Q.; Yan, Y. An End-to-End Steel Surface Defect Detection Approach via Fusing Multiple Hierarchical Features. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2020, 69, 1493–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. YOLOv3: An Incremental Improvement. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.02767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, B.; Li, L.; Li, L.; Geng, Y.; Cheng, M.; Xiaoming, X.; Chu, X.; Wei, X. YOLOV6: A Single-Stage Object Detection Framework for Industrial Applications. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2209.02976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Yeh, I.H.; Mark Liao, H.Y. Yolov9: Learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, W.; Xu, S.; Wei, J.; Wang, G.; Dang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. DETRs Beat YOLOs on Real-time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 16965–16974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).