Abstract

Methods, algorithms, and models for the creation and practical application of digital twins (3D models) of agricultural crops are presented, illustrating their condition under different levels of atmospheric CO2 concentration, soil, and meteorological conditions. An algorithm for digital phenotyping using machine learning methods with the U2-Net architecture are proposed for segmenting plants into elements and assessing their condition. To obtain a dataset and conduct verification experiments, a prototype of a software and hardware complex has been developed that implements the process of cultivation and digital phenotyping without disturbing the microclimate inside the chamber and eliminating the subjectivity of measurements. In order to identify new data and confirm the data published in open scientific sources on the effects of CO2 on crop growth and development, plants (ten species) were grown at different CO2 concentrations (0.015–0.03% and 0.07–0.09%) with a 10-fold repetition. A model has been built and trained to distinguish between cases when plant segments need to be combined because they belong to the same leaf (p-value = 0.05), and when they belong to a separate leaf (p-value = 0.03). A knowledge base has been formed, including: 790 3D models of plants and data on their physiological characteristics.

1. Introduction

Modern monitoring, forecasting, and management systems for territories and facilities of various levels and purposes—including those used in agricultural production—are increasingly incorporating automation tools, mathematical and computer modeling, and intelligent data analysis. These systems not only perform traditional functions such as collecting, processing, and storing large and heterogeneous datasets, but also support intelligent decision-making. Such approaches are outlined, for example, in [1,2,3,4,5], as well as in previous studies by the authors, which present the results of developing management systems for complex dynamic agricultural objects [1,3,6,7].

At the same time, it is essential to address the complex challenge of balancing the economic and social interests of society with environmental protection: preserving natural resources, minimizing negative climate impacts, and advancing technologies and practices in the field under consideration [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13].

In this article, we focus on digital modeling as a means of addressing one of the most pressing and widely discussed global environmental problems of our time—the greenhouse effect. The primary driver of this phenomenon is the concentration of greenhouse gases (GHGs) in the atmosphere (mainly carbon dioxide, CO2), which trap thermal radiation and contribute to climate change, including rising temperatures, ozone depletion, and related effects [14]. As a result, recent years have seen a surge in scientific research that provides objective assessments of GHG concentrations from both anthropogenic and natural sources, evaluates their harmful impacts [15,16,17,18,19], and models climate change, among other aspects [2,4]. Some studies also examine climate security within the agricultural sector, such as the research presented in [20,21,22].

It is important to note that there remains a lack of studies that evaluate, forecast, and model agricultural conditions while considering the potential positive effects of GHGs—particularly CO2—on the growth and development of specific crops under certain environmental conditions [23]. However, several studies have demonstrated that in arid regions and risky farming zones in northern areas, increased CO2 concentrations can have a positive impact on the yields of crops such as wheat, barley, soybeans, sunflowers, cabbage, radishes, and beets [24,25]. On average, these studies report a 26% yield increase across all crop types and a 40% increase in the dry matter content of young plants. These effects are closely linked to enhanced photosynthesis, as well as indirect improvements to the humus layer of the soil, which plays a significant role in soil fertility and crop productivity [26].

Some models developed by various authors [26,27] can serve as a foundation for a comprehensive methodology to manage agricultural productivity, accounting for GHG dynamics and other natural and anthropogenic factors. Our research team has also developed a scientific framework that includes a situational model combining artificial neural network technologies with geographic information systems, along with its software implementation [16,17,18]. This model enables the automated visual assessment and forecasting of the dispersion and accumulation of GHGs (CO2, CH4, O3, N2O) in a given area, while also evaluating the concentrations of other atmospheric pollutants such as CO, NOx, SO2, and CxHγ [20,21]. These assessments take into account the characteristics of economic activities in the region, transportation flow parameters, air temperature, humidity, wind direction, and wind speed.

The next stage of our research involves creating a database of digital twins for agricultural crops. These digital twins will reflect the qualitative state of crops under various parameter combinations, including CO2 concentrations in the lower atmosphere, soil mineral composition, and meteorological factors [28]. When used in conjunction with the previously described models, these digital twins will enable farms and agricultural enterprises to perform timely and comprehensive assessments of crop growth and development under current and projected external conditions. This approach will support scientifically grounded decision-making for optimizing land use and achieving maximum economic returns.

Until the last decades of the 20th century, research on the impact of varying CO2 concentrations in the lower atmosphere on both the activity of the photosynthetic apparatus and the growth processes of plants—as well as on fruit quality—received insufficient attention. This was likely due to the technical challenges associated with conducting such experiments. However, to date, more than 300 species, including both cultivated and wild flora, have been studied in long-term experiments involving different atmospheric CO2 concentrations [20,21,22,28,29].

The most characteristic response among C3 plant species is a significant increase in leaf area, although the magnitude of this effect varies considerably across experiments and depends on factors such as plant density (cenotic interactions) and the dynamics of other natural, climatic, and anthropogenic influences. It is also noteworthy that C4 plants have been included in these studies. While their photosynthetic apparatus typically shows a weak response to elevated CO2 levels [30,31], there have been documented cases of significant productivity increases in these species [32]. In the context of agricultural production, such responses indicate the potential to enhance crop yields and improve the productivity of agricultural territories.

To identify reliable correlations between the morphological, physiological, and anatomical parameters of crop growth—both in individual plant parts and the whole plant—and technological cultivation parameters and external factors, it is essential to record these values simultaneously under various combinations of conditions. Particularly promising is the development and exploration of methods for constructing digital twins of plants in the form of volumetric three-dimensional reconstructions. A database of such 3D models, reflecting plant appearance under different meteorological, soil, and climatic conditions, will enable agricultural specialists to conduct predictive, objective, and visual assessments of crop development and cultivation outcomes. This will also support evaluations of potential yields and the overall productivity of a given area.

Creating a digital twin of a crop requires a detailed description of the plant’s developmental structure under artificially recreated environmental conditions. However, this is complicated by the structural diversity of branching processes, which are influenced by genotype, phenotypic plasticity, and various external factors. Therefore, the development of a specialized digital phenotyping method is required to record morphometric growth parameters of individual plant parts, organs, and plants as a whole under increased CO2 concentration. This is driven by the need for objective registration and processing of a large volume of data simultaneously, as well as reducing the influence of the human factor. This approach will foster a more comprehensive understanding of plant responses to environmental changes, ultimately aiding in the optimization of agricultural practices and increasing crop productivity.

The aim of this research is to develop a method for digital phenotyping based on intelligent technologies, allowing for the accurate 3D modeling and segmentation of plants with a precision of at least 95%. This will lead to the creation of a database of digital plant twins that visualize their condition under various combinations of cultivation parameters and natural environmental conditions. The use of crop models in conjunction with systems for assessing and forecasting the dispersion and accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere—while monitoring harmful impurities—will support scientifically grounded, adaptive decision-making for rational agro-ecological zoning. As a result, this approach will contribute to increased crop yields and improved overall productivity of agricultural areas.

To achieve these objectives, the following tasks were addressed: the development of hardware and software tools to enable the collection of crop parameters and images at various growth stages; the development of a digital phenotyping method for plants cultivated under increased CO2 concentrations; conducting experiments on plant cultivation under different conditions; and the development of an algorithm for applying digital twins of plants to perform agro-ecological zoning of agricultural regions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Approaches to the Formation of Adequate Digital Twins of Plants

The assessment of morphometric parameters of plants can be conducted based on two-dimensional images or through volumetric reconstruction of plants in three-dimensional space [33]. In the first case, measurements are taken in the image plane in pixels, which are then converted into a metric measurement system [34,35,36]. This approach has algorithmic and computational simplicity. However, the drawbacks of this method become evident when the anatomical structure of the plant becomes more complex. Dense branching, a large number of leaves, or leaves with large leaf blades can obscure the elements of the plant located behind them, making it difficult to accurately assess its structure. To overcome this issue, a series of photographs from different angles is utilized—top view, and a series of side views with a fixed rotational step. Parameters are calculated for each image, and then the obtained values are analyzed to derive the most accurate results [37]. However, even with this approach, it is challenging to obtain numerous parameters with high precision, such as leaf angles, surface areas, and volumes of leaves and stems. Currently, with the use of high-performance computers, portable cameras, and sensors, along with methods of intelligent modeling, it has become possible to apply various approaches to create accurate 3D models of plants. Different methods based on two-dimensional images are employed [38,39,40], as well as automated systems for collecting and assessing growth parameters and the condition of plants [41,42].

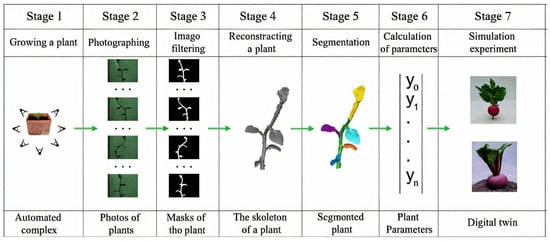

To conduct the research within the set objective, we proposed a scheme consisting of seven stages, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Stages of developing a digital twin of a plant.

At stages 1–3 of the proposed scheme, non-invasive monitoring of plant growth and development parameters is performed through the collection of photographs taken from various angles. From these images, bit masks are extracted, which are essential for constructing the 3D model. Stages 4–7 involve the process of plant model reconstruction.

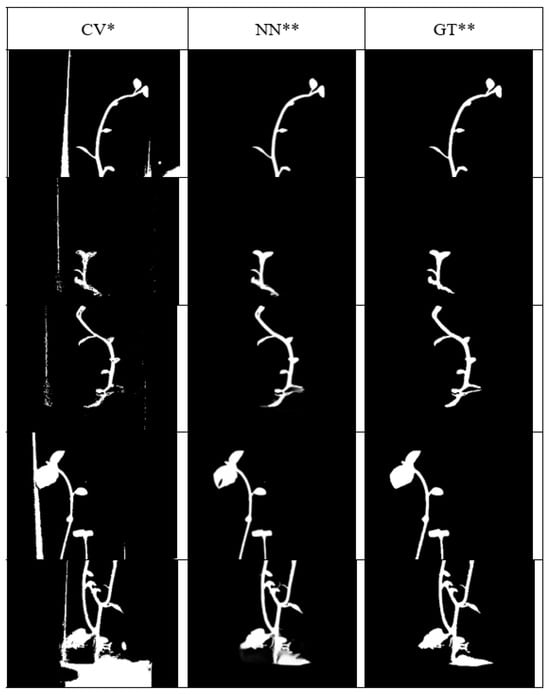

We tested several approaches using classical computer vision methods and identified two primary drawbacks: while segmentation performs well at the center of the image, accuracy significantly degrades near the edges. To address this, various neural network (NN) architectures were analyzed [13]. As a result, the U2-Net architecture was selected for plant segmentation, as it effectively overcomes the limitations observed in classical methods. This neural network is notable for its ability to learn from small datasets and for its high segmentation performance. Its application significantly reduces the number of contour gaps that typically occur when using traditional computer vision techniques.

Examples of plant image segmentation using different methods are shown in Figure 2, where *CV represents the bit mask obtained via classical computer vision, **NN denotes the bit mask generated using the U2-Net neural network, and **GT refers to the manually annotated ground truth mask.

Figure 2.

Visualization of the iterative process in image segmentation.

A comparison of results for the metrics—precision, recall, and F1 score—was conducted for both methods (Table 1). The analysis clearly demonstrates the advantages of using machine learning based on the U2-Net architecture.

Table 1.

Comparison of plant segmentation methods on images.

In constructing a digital twin of a plant based on processing a series of images using the selected neural network (NN), an iterative Space Carving method is proposed, incorporating an additional input parameter to control the allowable reconstruction error, denoted as thresh3D. This parameter enables the inclusion of voxels in the model that are projected onto images of the plant, provided that the projected voxel box contains at least one non-zero pixel in no fewer than n × thresh3D images, where n is the total number of processed images. This approach partially mitigates the effects of various distortions present in the images.

Following this, Stage 5 of the scheme shown in Figure 1 is carried out. During this stage, the following actions are performed: segmentation is applied to the reconstructed 3D model of the plant to distinguish between different organs, such as the stem and leaves. A graph representation of the plant is constructed based on the 3D model; the base vertex of the stem is identified, and segments are iteratively extracted. These segments consist of the shortest path from the beginning to the end of each segment, along with the vertices belonging to that path. Each segment is then classified according to its organ type.

In the final stages of the proposed scheme, the plant’s growth parameters are recorded (Stage 6), and the final digital twin of the plant is generated with visualization as a 3D model (Stage 7). This model can subsequently be used in simulation experiments to determine optimal growth conditions and to achieve the desired yield.

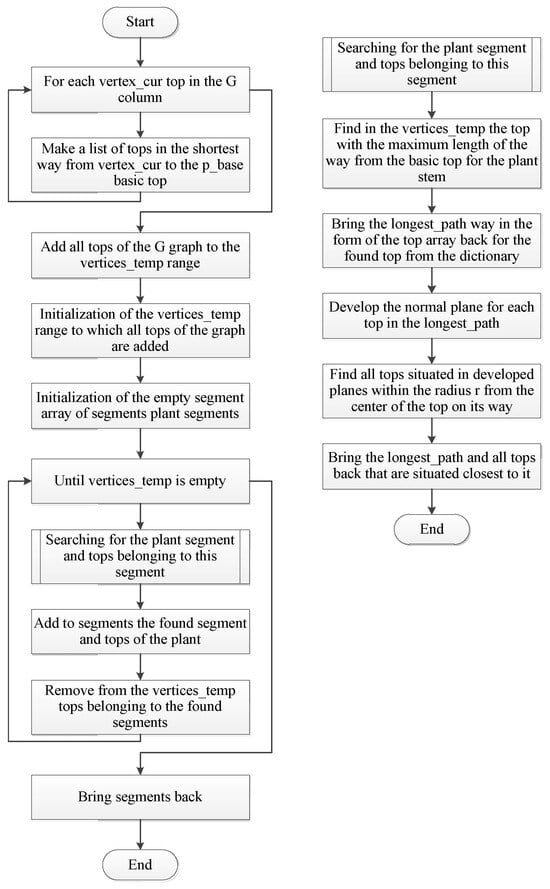

2.2. The Algorithm of Digital Plant Phenotyping

Based on the approaches proposed in Section 3, we have developed a method for determining the morphometric traits of the studied plant, regardless of its structural complexity. This method is presented as an algorithm in Figure 3. A total of 10 parameters of the plants are considered, namely: volume, coordinates of the starting point, coordinates of the endpoint, height, length, surface area of the plant or its parts; as well as maximum and average width, azimuth, and inclination of the plant parts. The volume of the plant or its segments is determined by raising to the third power the product of the number of voxels in a given segment and the size of the voxel:

where thresh3D—the number of voxels in a given segment or in the plant model as a whole; vbase_size—the size of the voxel.

Figure 3.

Prototype of the software and hardware complex for conducting experimental research, development, and updating of digital models.

The coordinates of the point of origin of the plant or its parts correspond to the first element in the shortest path spathi:

The coordinates of the end point of the plant or its parts correspond to the last element in the shortest path spathi:

The height of a plant or its parts is defined as the difference between the maximum and minimum value of the coordinate z in spathi:

The length of a plant or its parts is defined as the sum of the Euclidean distances between successively connected vertices of the shortest path spathi from the two most distant points of the segment:

The maximum width of the plant parts is defined as the maximum value in the vector:

The average width of plant parts is calculated as the sum of all elements of the vector width_slices divided by their number:

To calculate the area of a sheet, any of the numerical integration methods is used for values of widthslicesi with intervals of lengthslicesi. The doubled value of the integral is the surface area of the sheet on both sides.

To calculate the area of the plant trunk, we will represent the trunk in the form of sequentially connected cylinders and sum up the areas of their lateral surfaces:

The surface area of the entire plant is the sum of the surface areas of the leaves and the stem:

The azimuth of the plant elements is calculated as the arctangent of the y and x projections of the average value of the sum of the vectors along the shortest path spathi from the two most distant points in the segment si:

The slope of the plant elements relative to the vertical axis is calculated as the average value of the sum of the scalar products between the normalized values of the vectors in v̂0Z, directed along the 0Z:

2.3. Software and Hardware Complex for Conducting Laboratory Experiments, Data Collection, and Forming Training and Test Samples

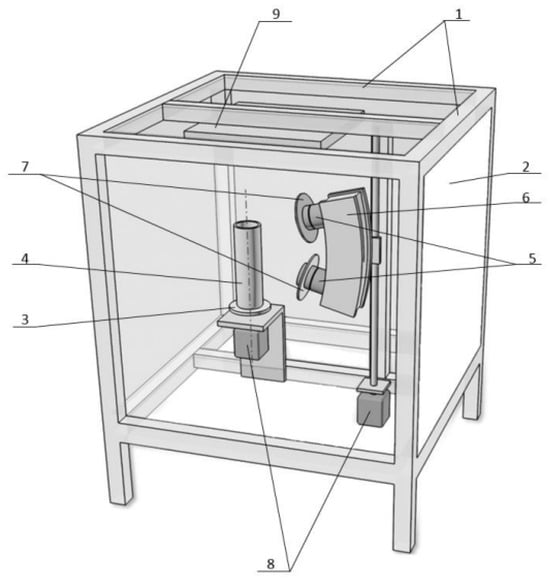

As mentioned earlier, to develop digital twins of plants under various combinations of parameters such as CO2 concentration in the atmospheric boundary layer, meteorological conditions, and soil mineral composition, it is essential to obtain corresponding images of real samples while recording their quantitative and qualitative characteristics at different stages of growth. Thus, conducting laboratory experiments is necessary. The authors have proposed an original software and hardware complex that includes all the necessary components for experimental research, as well as for the development and updating of digital models. Its prototype is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Prototype of the software and hardware complex for conducting experimental research, development, and updating of digital models. 1—Frame; 2—Removable panels; 3—Rotating platform; 4—Container; 5—Photographic and video cameras; 6—Movable platform; 7—Multispectral light sources; 8—Drives; 9—Lighting lamp.

The software and hardware complex includes equipment for the simultaneous collection of essential data on the studied technological process, for simulating various external plant growth conditions that resemble real environments, for photographing plants from multiple angles and in different spectra, as well as a personal computer equipped with the necessary software and models for processing the images to create digital twins of plants.

In Figure 4, the following components are identified:

- Frame—a hollow parallelepiped welded from sheet stainless steel, with a ceiling made of organic glass and a sealed hatch, having a total volume of 3 m3;

- Removable panels—light-blocking panels;

- Rotating platform—located inside the enclosure, designed to hold container 4 with the plant sample under analysis;

- Container—holds the analyzed plant sample;

- Photographic and video cameras (at least two)—mounted on a movable platform (6), ensuring synchronized video capture of the plant;

- Movable platform—designed for vertical movement via a screw drive, in a plane parallel to the axis of rotation of the rotating platform (3);

- Multispectral light sources—installed on the photographic and video cameras (5), providing radiation of adjustable spectrum to illuminate the plant;

- Drives—installed inside the enclosure to control the positions of platforms (3) and (6).

To minimize optical distortions, a proprietary multispectral lighting module, MS0119, was developed. Five types of optical sensors, two types of container mounts, and nine types of lighting configurations have been researched and tested.

The software and hardware complex also includes a continuously operating LI-820 infrared gas analyzer, which measures carbon dioxide concentration on a scale of 0–10,000 ppm (0–1% CO2) and supports automated data processing. Changes in air pressure resulting from CO2 addition are balanced by a variable-volume compensator. Excess oxygen produced during photosynthesis is removed every four days through depressurization and ventilation of the phytotron. The light intensity for the age-diverse plant community is manually adjusted by altering the height of the light fixtures. The chamber’s air temperature is automatically maintained by an electronic control system, with heating provided by both radiant heat from the lamps and an electric heater. Air circulation and mixing are ensured by two fans.

The developed complex enables research to be conducted without disrupting the internal microclimate. It significantly accelerates the data registration process and eliminates human error and subjectivity in measurements.

Importantly, this installation enables experimental research on real plants in artificially simulated conditions that closely approximate natural environments. This facilitates the assessment of the influence of various natural, climatic, technological, and anthropogenic factors on plant growth and development. Additionally, it supports the collection of a comprehensive range of data for the development of corresponding digital models. These models can then be effectively used for predicting agroecological situations and making informed ecological and economic decisions aimed at sustainable territorial development.

In line with the objectives and tasks of this work, we selected two ranges of carbon dioxide concentrations for study: 0.015–0.03% and 0.07–0.09%. The first range is normal for the photosynthesis process in C3 plant species under natural lighting conditions, while the second corresponds to elevated CO2 levels in the atmosphere due to the dynamics of the greenhouse effect influenced by various natural and anthropogenic factors. Depending on the research goals and the simulated growth conditions for plants in agricultural areas, the values of temperature and humidity for both air and soil, as well as the mineral composition of the soil, were varied.

The following criteria were defined to assess the response of the studied plant samples to changes in CO2 concentration while keeping other optimal factors fixed:

K1—the growth rate of raw and dry biomass of plant organs [43,44];

K2—the content of mineral elements in plants (N, P, S, K, Ca, Mg) [45].

The analytical determination of the criteria K1 and K2 was conducted by researchers from the International Scientific Research Laboratory of Ecological Engineering at Belgorod State National Research University and Satbayev University using the following methods and instruments: K-method of flame photometry on the Flapho-4 device, Ca- and Mg-method of atomic absorption spectroscopy on the AAS-IN spectrometer, N-method of photocolorimetry according to Kjudal, P-method of photocolorimetry, and S-method of titrimetry.

2.4. Studied Ecosystems

In this study, we selected four agricultural crops significant for the phototrophic component of the ecosystem, specifically vegetables, for examination:

- Radish (Raphanus sativus L.) variety “Virovsky White”—an annual plant from the cruciferous family, which is moisture-loving and light-loving.

- Carrot (Daucus carota L.) variety “Vitamin 6”—a biennial plant from the umbrella family with finely dissected leaves, classified as a mid-season variety.

- Beet (Beta vulgaris L.) variety “Egyptian”—a biennial plant from the amaranth family.

- Kohlrabi (Brassica caulorapa L.)—a biennial plant from the cruciferous family.

The raw mass and dry residue mass of all vegetable crops (indicator K1) were determined for carrot, beet, and kohlrabi plants at 26, 52, and 78 days of vegetation, while for radish plants, measurements were taken at 13 and 26 days.

Due to the complex structure of these crops, as the root vegetables are located underground and are inaccessible for phenotyping through camera images during growth, a decision was made to expand the training and testing samples to verify the method of forming digital twins of various plants. The study included species where all leaves grow from the main stem, namely:

- 5.

- Rye (Secale cereale L.)—an annual cereal plant from the grass family, an important agricultural crop.

- 6.

- Pea (Pisum sativum L.)—an annual leguminous plant, an important agricultural crop.

- 7.

- Broadleaf Cress (Barbarea vulgaris L.)—a biennial plant from the cabbage family, used as a forage plant and in homeopathy.

- 8.

- Peach-leaved Bellflower (Campanula persicifolia L.)—a perennial herbaceous plant from the bellflower family, used as a forage plant and in homeopathy.

- 9.

- Soybean (Glycine max L.)—an annual leguminous plant belonging to the legume family, an important agricultural crop widely used as a source of protein and oil.

- 10.

- Fiddle Leaf (Ficus lyrata)—a popular houseplant from the mulberry family, an evergreen tree or shrub.

All the presented plant species have different structures and vary in the sizes of their stems and leaves, which is crucial for developing an adequate method of digital phenotyping.

2.5. The Algorithm of Using Digital Twins for Agroecological Zoning of Territories

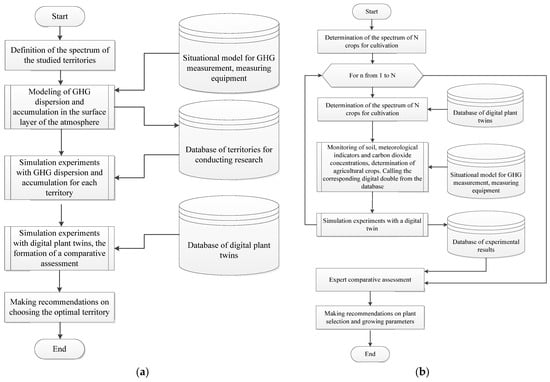

We have developed a methodology for utilizing the established bank of digital twins of plants to conduct predictive simulation experiments and effective zoning of agricultural territories to enhance their productivity. In this aspect, two tasks can be addressed:

- −

- For a specific studied area, evaluate the yield of all agricultural crops used by the producer for cultivation, based on existing or forecasted values of CO2 concentrations, soil mineral composition, and meteorological parameters. Conduct a comparative analysis to identify the crops with the highest yield (algorithm shown in Figure 5a).

- −

- For a specific crop required for cultivation, assess its yield across different territories belonging to various farms or agricultural holdings, based on existing or forecasted values of CO2 concentrations, soil mineral composition, and meteorological parameters. Identify the territories with the highest yield indicators for this crop (algorithm shown in Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

(a) Algorithm for selecting agricultural crops with high yield potential for the studied area; (b) Selection of territories with high yield indicators for the required agricultural crop.

In the proposed methodology, the solution to the outlined tasks is linked to conducting simulation experiments using both the developed bank of digital twins of plants and models for assessing and forecasting the dispersion and accumulation of greenhouse gases in the studied area, along with monitoring the environmental situation [6].

The implementation of the presented algorithms will enable scientifically justified adaptive agro-ecological zoning of territories in the context of the dynamics of natural-climatic and technological parameters, aimed at ensuring high productivity. The expansion and utilization of the bank of digital twins of plants, along with conducting a series of simulation experiments under modeled conditions, will optimize the growth and development conditions of plants, including important agricultural crops. This approach will also allow for timely responses to natural-climatic and technogenic changes, enabling effective operational measures to alter the ecological and economic characteristics of territories, thereby increasing their productivity and overall economic benefits.

3. Results

3.1. Results of Experimental Studies on the Impact of Carbon Dioxide Dynamics on Plant Growth and Development

The software-hardware complex developed by the authors enabled simultaneous experimentation to assess the influence of varying carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations on the parameters K1 and K2, as introduced in Section 3.2, across the studied plant species. In parallel, the system supported the formation of a comprehensive image-based database capturing plant development at various growth stages and under different combinations of natural-climatic and technological growth parameters, including stages of fruit ripening (for vegetable ecosystems).

Each experimental setup included 10 biological replicates, with 5–6 sampling intervals per replicate. For each measurement, mean values and relative errors were calculated. A 95% confidence level (p = 0.05) was used to evaluate statistical significance. The reported data, unless otherwise noted, represent arithmetic means from two independent experiments. These were derived from continuous computerized monitoring of gas exchange indicators under varied CO2 concentrations.

All plant samples were cultivated in a controlled environment with a fixed mineral nutrient composition (N = 23, P2O5 = 36, K2O = 84 mmol/100 g). Seeds were planted at a uniform depth of 2.0–2.5 cm. The air temperature inside the phytotron was maintained at 24 °C, while relative humidity fluctuated between 70 and 80%. Plants were grown under two CO2 concentration ranges: 0.015–0.03% and 0.07–0.09%.

3.1.1. Effects of Carbon Dioxide on Radish Growth and Development

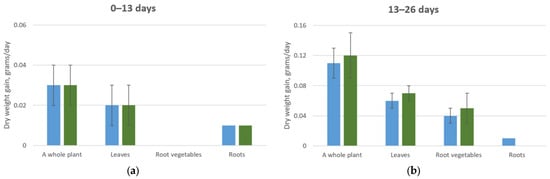

In the case of vegetable ecosystems, the results reveal non-uniform patterns in plant responses to elevated CO2 levels. For example, radish plants grown under different CO2 concentrations showed minimal variation in the rate of dry matter accumulation and in the total dry biomass (both whole plant and individual organs), particularly during the early stages of development, as illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Assessment of criterion K1 for radish.

Specifically, within the first 13 days of vegetation, radish plants accumulated comparable amounts of dry matter across all treatment groups, irrespective of CO2 levels. This consistency was observed both in overall biomass and in organ-specific accumulation (leaves and roots). However, it is noteworthy that plants exposed to elevated CO2 concentrations (0.07–0.09%) exhibited an approximate 40% reduction in the raw leaf mass compared to those grown under ambient CO2 conditions (0.015–0.03%).

It was noted that there was a weak influence of elevated CO2 concentrations on the ratio of the relative increase in root mass compared to the shoot in radishes throughout the entire study period. Additionally, with the increase in atmospheric CO2 concentrations, the experimental plants exhibited a decrease in the content of certain mineral elements in their leaves and roots compared to plants grown at concentrations of 0.015-0.03%. This likely indicates changes in the absorption and transport of these ions by the root system (Table 3 and Figure 6).

Table 3.

Assessment of criterion K2 for radishes, %.

Figure 6.

Average daily dry biomass increase of a radish plant. (a) Plant development from 0 to 13 days under CO2 concentrations of 0.015–0.03% (blue column) and 0.07–0.09% (green column); (b) Plant development from 13 to 26 days under CO2 concentrations of 0.015–0.03% (blue column) and 0.07–0.09% (green column).

3.1.2. Effects of Carbon Dioxide on Cabbage Growth and Development

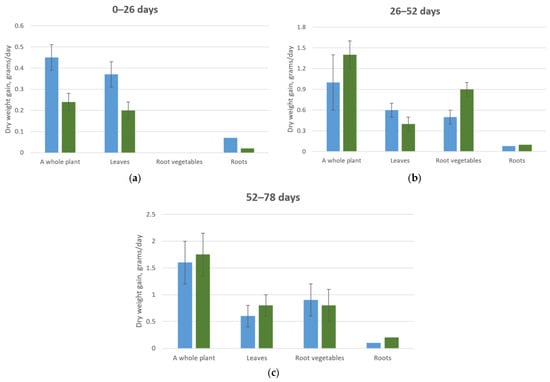

A different response to elevated CO2 concentrations was observed in cabbage plants, which experienced an inhibitory effect from the increased levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere during the early stages of their growth. However, with continued cultivation, these samples accumulated greater dry and fresh weight compared to plants grown at standard CO2 concentrations (0.015–0.03%), as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Assessment of criterion K1 for cabbage, g.

Data on the mineral composition of 52-day-old cabbage plants indicate that plants grown at CO2 concentrations of 0.015–0.03% show a decrease in the percentage of potassium, calcium, and magnesium in the roots, averaging 53.4% compared to 26-day-old plants. Meanwhile, the levels of these minerals in other plant organs remain relatively high, even when compared to plants grown at CO2 concentrations of 0.07–0.09% (Table 5, Figure 7).

Table 5.

Assessment of K2 criterion for cabbage, %.

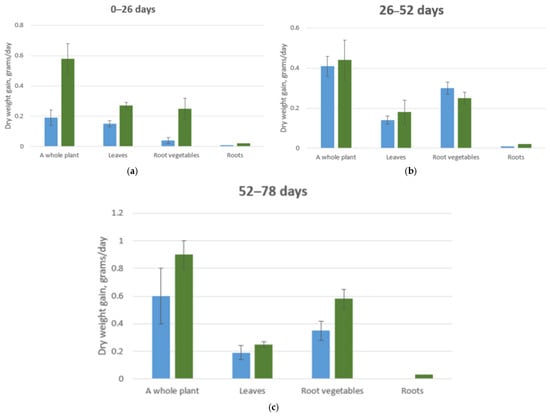

Figure 7.

Average daily dry biomass increase of a cabbage plant. (a) Plant development from 0 to 13 days under CO2 concentrations of 0.015–0.03% (blue column) and 0.07–0.09% (green column); (b) Plant development from 13 to 26 days under CO2 concentrations of 0.015–0.03% (blue column) and 0.07–0.09% (green column); (c) Plant development from 13 to 26 days under CO2 concentrations of 0.015–0.03% (blue column) and 0.07–0.09% (green column).

3.1.3. Effects of Carbon Dioxide on Carrots Growth and Development

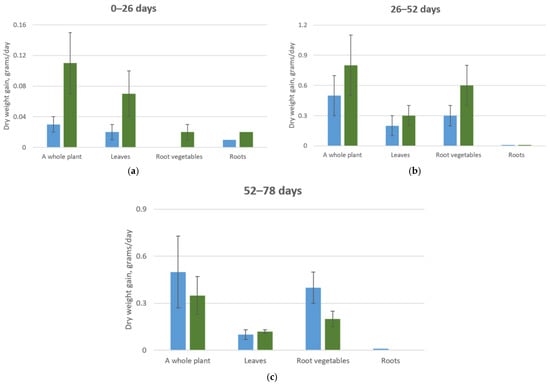

Growing carrot plants at elevated CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere revealed that those at CO2 levels of 0.07–0.09% accumulated more dry and fresh biomass throughout the entire growing period compared to plants at standard CO2 concentrations (Table 6).

Table 6.

Assessment of criterion K1 for carrots, g.

The analysis of the mineral composition at 52 days of growth indicated that for plants at CO2 concentrations of 0.07–0.09%, there was a decrease in the phosphorus and potassium content in the root tissues, similar to the observations made at 26 days of growth. However, no significant differences were noted for other biogenic elements, except for calcium in the root tissues and magnesium in the leaves (Table 7, Figure 8).

Table 7.

Assessment of the criterion K2 for carrots, %.

Figure 8.

Average daily dry biomass growth of a cabbage plant. (a) Plant development from 0 to 13 days at CO2 concentrations of 0.015–0.03% (blue column) and 0.07–0.09% (green column); (b) Plant development from 13 to 26 days at CO2 concentrations of 0.015–0.03% (blue column) and 0.07–0.09% (green column); (c) Plant development from 13 to 26 days at CO2 concentrations of 0.015–0.03% (blue column) and 0.07–0.09% (green column).

3.1.4. Effects of Carbon Dioxide on Beetroot Growth and Development

From the data presented in Table 8, it is evident that beet plants grown at CO2 concentrations of 0.07–0.09% accumulated more fresh and dry biomass, both for the whole plant and its individual organs, throughout the entire growing period. The rates of organic matter accumulation in various plant organs at this range of CO2 concentrations were higher, especially during the early growth stages, with the exception of the root crops at 52 days of growth, where their growth rate decreased by 7%.

Table 8.

Assessment of criterion K1 for beetroot, g.

In beets, as well as in other studied vegetable crops, an increase in the relative content of total nitrogen was observed in all plant organs. For the other mineral elements, the differences were less significant and showed only slight variations between the control and experimental plants throughout the growing period (Table 9, Figure 9), with the exception of potassium ions (in the root tissues), calcium, and magnesium (in the photosynthetic tissues).

Table 9.

Assessment of the K2 criterion for beetroot, %.

Figure 9.

Average daily dry biomass increase of a cabbage plant. (a) Plant development from 0 to 13 days at CO2 concentrations of 0.015–0.03% (blue column) and 0.07–0.09% (green column); (b) Plant development from 13 to 26 days at CO2 concentrations of 0.015–0.03% (blue column) and 0.07–0.09% (green column); (c) Plant development from 13 to 26 days at CO2 concentrations of 0.015–0.03% (blue column) and 0.07–0.09% (green column).

3.2. Modeling Metrics and Their Analysis

For plant segmentation using machine learning methods, a U2-Net architecture-based neural network was employed. In this work, training images of plants obtained under various growing conditions were used. The training set consists of 298 images, while the validation and test sets each contain 57 images, corresponding to a 5:1:1 ratio, totaling 412 images. Additionally, to address lighting issues captured by the camera, 130 images in the training set were enhanced—along with mirror reflections—by adjusting contrast and brightness. This process expands the dataset, providing more comprehensive data support for training the model and improving its generalization.

To evaluate the qualitative and quantitative indicators of plant modeling at growth stages from day 3 to day 26, with a modeling interval of Tn—2 days, the following experiments were conducted:

- −

- Analysis of the influence of the parameter thresh3D on the quality of the generated 3D models;

- −

- Analysis of the influence of the parameter vbase_size on the quality of the generated 3D models;

- −

- Analysis of the influence of the parameter thresh3D on the time required to create a 3D model;

- −

- Analysis of the influence of the parameter vbase_size on the time required to create a 3D model.

3.2.1. Analysis of the Influence of the Parameter thresh3D on the Quality of the Generated 3D Models

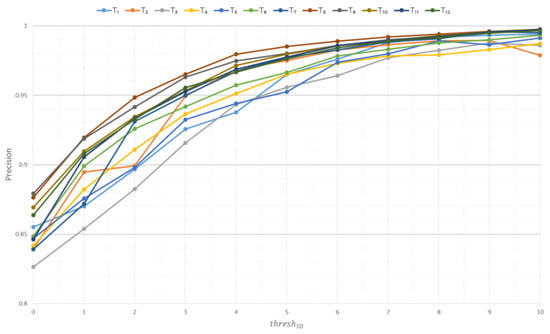

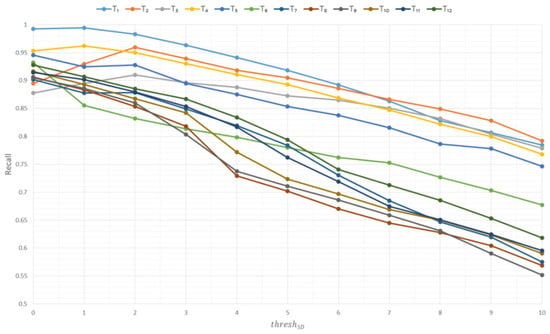

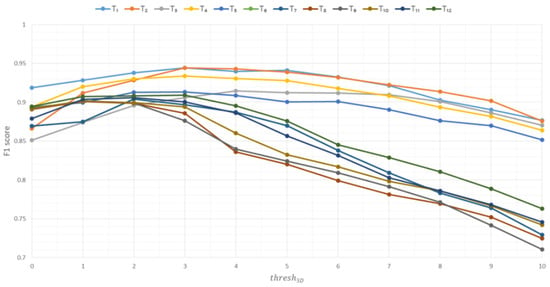

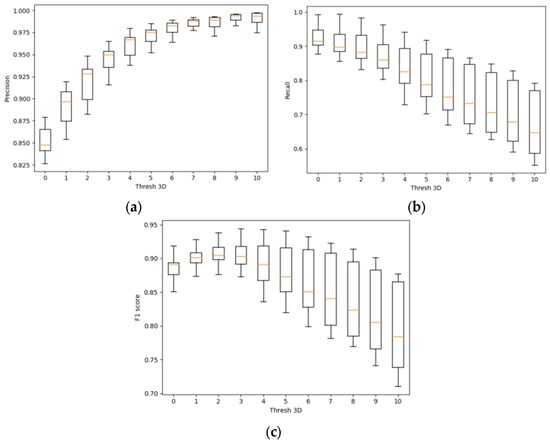

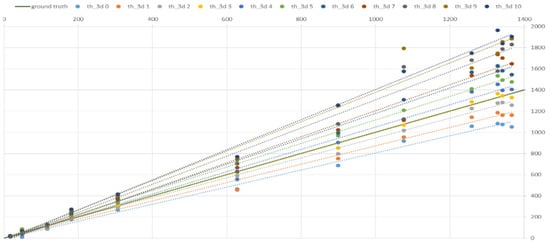

Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12 show the graphs of the influence of the parameter thresh3D on the metrics precision, recall, and F1 score based on the Soy plant model for growth stages T1–T12, respectively.

Figure 10.

Influence of the thresh3D parameter on the precision metric based on Soy plant models.

Figure 11.

Influence of the thresh3D parameter on the recall metric based on Soy plant models.

Figure 12.

Influence of the thresh3D parameter on the F1 score metric based on Soy plant models.

Figure 13 shows box plots of the metrics precision, recall, and F1 score based on Soy plant models for the parameter thresh3D.

Figure 13.

Box plots of the metrics (a) precision; (b) recall; (c) F1 score for various parameters thresh3D.

Based on the experimental data, the following conclusions can be drawn:

- −

- As the thresh3D parameter increases, the precision metric also increases, indicating that the constructed model encompasses more voxels belonging to the original model.

- −

- As the thresh3D parameter increases, the recall metric decreases, indicating that the constructed model includes more voxels not belonging to the original model.

- −

- As the thresh3D parameter increases, the F1 score metric initially rises, then declines. The optimal thresh3D value for plants modeled under current conditions is the maximum median value on the box plot for the F1 score metric. This corresponds to thresh3D = 3.

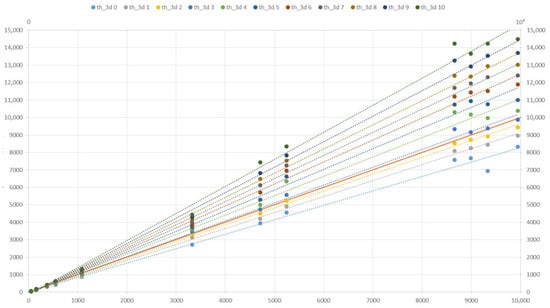

3.2.2. Analysis of the Influence of the vbase_size Parameter on the Quality of the Generated 3D Models

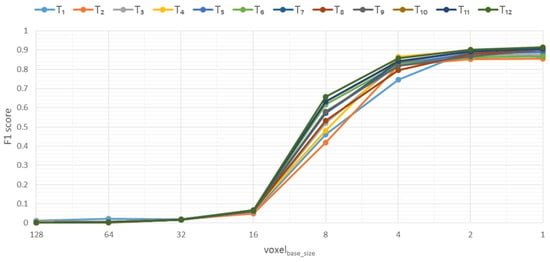

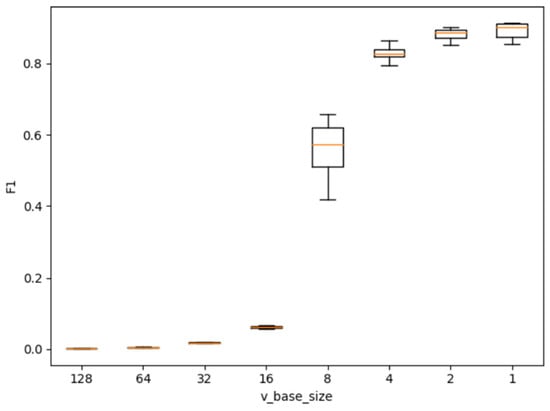

The study of the influence of the vbase_size parameter on the quality of the generated 3D models showed that when the voxel size is halved, the F1 score metric’s growth curve takes on an S-shape (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Influence of the parameter vbase_size to the F1 score metric based on Soy plant models.

Figure 15 shows a diagram of the range of the F1 score metric for the parameter vbase_size based on Soy plant model.

Figure 15.

The range diagram of the F1 score metric for the parameter vbase_size based on Soy plant models.

Based on the experimental data, the following conclusions can be drawn:

- −

- When vbase_size ≥ 16, the resulting plant model cannot be used for further calculations due to the extremely low construction accuracy.

- −

- When 2 < vbase_size < 16, the accuracy of the resulting models increases significantly;

- −

- vbase_size ≤ 2, the graph of model accuracy reaches a plateau;

- −

- The optimal vbase_size is equal to 4 or 2. When selecting vbase_size = 1, the accuracy of the resulting model almost does not increase, but the time to create the model is much longer, which will be shown below.

3.2.3. Investigation of the Effect of the Parameter thresh3D on the Creation Time of a 3D Model of a Plant

A study of the effect of the parameter thresh3D on the creation time of the 3D model showed that with an increase in the parameter thresh3D, the creation time of the model increases (Table 10). Thus, changing the parameter thresh3D from 0 to 10 leads to an increase in the average model creation time by 71.79%, changing the parameter thresh3D from 0 to the best 3 leads to an increase in the model creation time by 23.46%.

Table 10.

Dependence of the model creation time in seconds on the parameter thresh3D for growth stages T1–T12.

3.2.4. Investigation of the Influence of the Parameter vbase_size at the Time of Creating the 3D Model of the Plant

Investigation of the influence of the parameter vbase_size at the time of creation of the 3D model, it was shown that with a decrease in the voxel size, the graph of growth in simulation time increases significantly (Table 11).

Table 11.

Dependence of the model creation time in seconds on the parameter vbase_size for growth stages T1–T12.

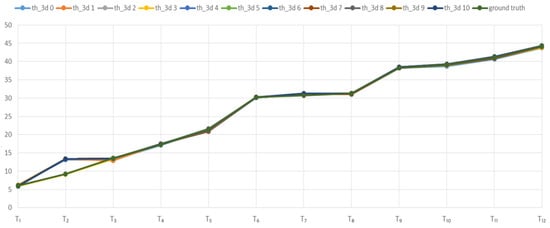

3.3. Phenotyping Metrics

A study of the dependence of the accuracy of determining the height of plants on the parameter thresh3D showed that this parameter has no significant effect (Figure 16).

Figure 16.

The effect of the parameter thresh3D on the height of the model (mm.) based on models of the Soy plant at the stages of development T1–T12.

A study of the dependence of the accuracy of determining the height of plants on the parameter thresh3D showed that this parameter has no significant effect (Figure 17).

Figure 17.

The effect of the parameter thresh3D on the value of the surface area (mm2) based on Soy plant models relative to the original (mm2).

A study of the dependence of the accuracy of determining the volume of plants on the parameter thresh3D showed that the most accurate result is achievable at thresh3D [3,4] (Figure 18).

Figure 18.

The effect of the parameter thresh3D on the volume of the model (mm3) based on the Soy plant models relative to the original (mm3).

Metrics of Plant Segmentation Quality by Species

The diverse spectrum of plants presented allows for the adequacy of the method when using various plant structures. The verification of the method was carried out based on the calculation of metric values such as MAE (Mean Absolute Error), MSE (Mean Square Error), MAPE (Mean Absolute Percentage Error), and MPE (Mean Percentage Error) [45] for each plant species (Table 12).

Table 12.

Metrics of plant segmentation quality by species and on average.

For the plants Pea and the peach-leaved bell, the lowest MAE values (0.078 and 0.056, respectively) are observed, along with very small MAPE (1%). This indicates high prediction accuracy for these crops. MAE values above 0.75 (for example, for Cabbage) demonstrate that the model is less accurate for these plants. An error deviation of up to 10% from the plant’s true value can be considered acceptable.

4. Discussion

4.1. Results of Experiments with Crop Cultivation

To date, over 300 species, representatives of not only cultural but also wild flora, have been studied in experiments with growing plants in an atmosphere with different CO2 content [20]. This number of studied species often includes C4 plants, although their weak photosynthetic response to an increase in CO2 concentration is known [29]. Not all of the completed works are equivalent. Thus, in many works, the main attention was paid to establishing the final effect of enriching the atmosphere with carbon dioxide—its effect on general and economic productivity, often in poorly controlled greenhouse conditions. Many physiological studies were performed when plants were exposed to specified CO2 concentrations during the growing season [31]. However, with such a variety of studies, the main mechanisms of plant adaptive reactions and their changes occurring at elevated CO2 concentrations have been identified.

The most unambiguous reactions of plants to prolonged cultivation in an atmosphere with a high CO2 content are an increase in their leaf surface area, a decrease in the ratio of leaf area to the dry weight of the plant and the value of the net productivity of photosynthesis [33]. However, the magnitude of the effect varies significantly in different experiments and depends on the degree of plant density and environmental factors.

Thus, in our opinion, vegetable crops responded positively to increased CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere up to 0.07–0.09%, primarily during the first 26 days of growth. The subsequent differences in the accumulation of dry and fresh biomass between plants at different CO2 concentrations were likely related to the fact that plants at 0.07–0.09% CO2 had already developed a sufficient assimilating leaf mass necessary to sustain intense growth compared to plants at traditional CO2 concentration ranges (0.015–0.03%).

Agricultural crops from different types of ecosystems and structures, such as Rye, Peas, and Soy, showed a positive response to increased CO2 concentrations in the range of 0.07–0.09%. For rye, there was an observed increase in plant height and mass, along with active development of the root system and leaves. In the case of soybeans and peas, an increase in dry and fresh biomass was noted at CO2 concentrations of 0.07–0.09%, ranging from 10% to 20% during the first 26 days of growth.

In experiments with forage plants, the following results were obtained. For yellow clover and bellflower, at CO2 concentrations of 0.07–0.09%, an increase in photosynthetic activity of 20–30% was observed compared to levels of 0.015–0.03%. This manifests as an intensification of growth and respiration processes in these plants, leading to an increase in biomass by 5–15%. In contrast, for the fiddle-leaf fig, only a negligible increase in biomass was noted at CO2 concentrations of 0.07–0.09%.

As mentioned above, the use of a software-hardware complex allowed for the collection of an excessive number of photographs of plants of all species at various CO2 concentrations for the creation of their digital twins. However, this stage, according to the proposed research methodology in Section 2.1, requires the development of a specialized method for digital phenotyping. This method should effectively address the identified issues related to the structure and size of the plants.

4.2. Results of Experiments with Plant Models

The evaluation of plant parameters based on two-dimensional images has been repeatedly performed by various engineering teams [3,4,5,6,15,16,17,18,19,20]. The parameters are measured in the image plane in pixels, which are then converted into a metric measurement system. This approach is algorithmically and computationally simple compared to methods working with 3D models of plants, and is capable of making a very accurate assessment of plant parameters with a relatively simple anatomical structure.

The disadvantages of the method appear when the anatomical structure of the plant becomes more complicated. Thus, the strong bushiness of plants, a large number of leaves or leaves with a large leaf plate can hide the plant elements located behind them, thereby making it impossible to correctly assess the structure of the plant and, as a result, make correct calculations. To overcome this problem, a series of photographs from various angles is used—a top view and a series of side views with a fixed rotation step—and then parameters are calculated on each image, and the values obtained are analyzed in order to obtain the most reliable [22].

However, even with this approach, it is not possible to obtain many parameters with high accuracy, such as leaf angles, surface areas, and volumes of leaves and stems. To obtain more accurate data and more parameters, a 3D model of the plant is created, on the basis of which further calculations are performed. This approach is a more difficult task from an engineering and computational point of view, but it allows us to obtain a larger number of plant parameters, as well as more accurate results, since the plant model retains the dimension of the space of a real object [22].

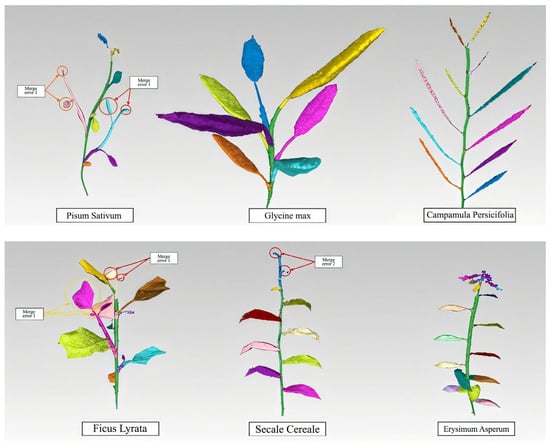

The analysis of the obtained data allows us to conclude that the segmentation algorithm performs better with plants that have a simple branching system, where all leaves grow from the main stem, such as Ficus lyrata, Cabbage, and Carrot. In plants with a complex branched system, segmentation errors are more common due to the fact that the total number of points in some neighboring segments is greater than the threshold and such segments are combined into one.

The resulting model, trained on a sample of photographs of plants that grew in conditions with different CO2 concentrations, makes it possible to distinguish between cases when plant segments need to be combined because they belong to one leaf (p-value = 0.05), and when they do not need to be combined because each segment belongs to a separate leaf (p-value = 0.03). Figure 19 provides examples of plant segmentation into elements, where errors occur only during the segmentation of young leaves, which have a biomass that is small compared to other leaves, such as in Secale cereale.

Figure 19.

Three-dimensional models of plants segmented into elements.

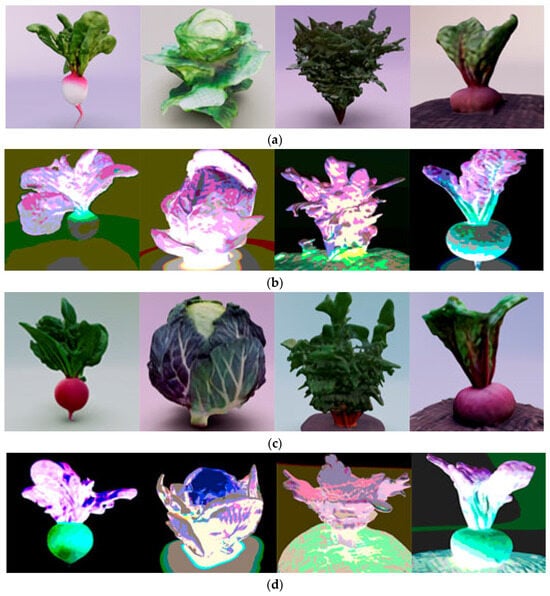

The visualization of the growth and development of root and stem crops is shown in Figure 20 at different CO2 concentrations of 0.015–0.03% (Figure 20a) and 0.07–0.09% (Figure 20b). The 3D models are presented in raster format with overlaid textures. Figure 20c,d also display images of the crops in the visible spectrum at the investigated CO2 concentrations.

Figure 20.

(a) Visualization of plant growth and development at CO2 concentrations ranging from 0.015 to 0.03%; (b) Photo of the crop in the visible spectrum at concentrations of 0.015–0.03% on the 26th day of growth; (c) Visualization of plant growth and development at CO2 concentrations ranging from 0.07 to 0.09%; (d) Photo of the crop in the visible spectrum at concentrations of 0.07–0.09% on the 26th day of growth.

Based on the conducted research and experimental work in the aforementioned international laboratory with other plant species, we obtained approximately 720 3D visualizations of 10 plant species used in both the agricultural sector and for decorative purposes. These visualizations were created while growing the plants at CO2 concentrations in different ranges: 0.015–0.03% and 0.07–0.09%, and for various soil types: leached chernozem and gray forest soils.

The results of the study can be used by scientific research laboratories of plant biotechnology, commercial enterprises for breeding or growing planting material in industrial volumes. Methods and algorithms of segmentation of plant models into organs, determination of morphometric features can be applied to make decisions on agroecological zoning of agricultural territories in conditions of external anthropogenic impact.

5. Conclusions

To carry out such scientifically justified zoning, especially under projected ecological and economic conditions, it is essential to enable expert specialists to perform a visual operational assessment of plant conditions under various combinations of natural-climatic, meteorological, and technological parameters.

We proposed an approach to the formation of digital twins of plants that accurately represent real ones, which includes 7 main stages and allows for the creation of precise 3D models. The crucial stages—reconstruction and segmentation of plants—are based on the functioning of an artificial neural network with a U2-Net architecture. Based on the proposed approach, we have developed an algorithm for digital phenotyping of plants with structures of any complexity. A total of 10 plant parameters were considered, namely: volume, coordinates of the starting point, coordinates of the endpoint, height, length, surface area of the plant or its parts; as well as maximum and average width, azimuth, and inclination of the plant parts. Based on the obtained data, quality metrics such as MAE, MSE, MAPE, and MPE were calculated, and the adequacy of the method was assessed.

To conduct laboratory experiments for assessing the growth and development of plants under the dynamics of the greenhouse effect, as well as for data collection and the formation of training and testing datasets for digital modeling, an original software-hardware complex has been proposed. It includes all the necessary components for conducting experimental research and also allows for non-invasive monitoring of the required parameters of the technological process under investigation. This setup enables experimental studies with plants in any artificially simulated conditions that are analogous to real ones.

The use of the software-hardware complex has allowed for the collection of an excessive number of photographs for constructing digital twins of the selected plants (20 species used in both the agricultural sector and for decorative purposes) under various combinations of CO2 concentrations, soil mineral composition, and meteorological parameters. A database has been created, including 720 3D models.

Algorithms for the use of digital twins of plants, which accurately reflect the structure and shape of all organs of the studied specimen in simulated conditions, are presented for the purpose of automated agroecological zoning of territories. Specifically, these algorithms facilitate simulation experiments to address two main tasks:

- −

- To identify the crop with the highest yield for a specific agricultural area;

- −

- To determine the territory with parameters that ensure the highest yield for a specific desired crop.

The implementation of the proposed algorithms contributes to ensuring high productivity of agricultural territories and supports the adoption of effective ecological and economic decisions for their sustainable development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.I.; methodology, B.Y.; software, D.G.; validation, D.G. and O.I.; writing—review and editing, O.I.; visualization, D.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science Committee of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. AP23489999) “Development of intelligent technology and digital platform for adaptive zoning of territories in the context of climate dynamics”.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GHGs | Greenhouse gases |

References

- Akilan, T.; Baalamurugan, K.M. Automated weather forecasting and field monitoring using GRU-CNN model along with IoT to support precision agriculture. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 249, 123468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharipova, L.; Khusenov, M. Creation of environmental pollution monitoring systems using digital educational technologies. AIP Conf. Proc. 2025, 3268, 70013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logachev, M.; Simonov, V. Information system as used to monitor sowing, care and harvesting on agricultural lands. BIO Web Conf.–EDP Sci. 2024, 83, 03002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolomiiets, S.; Khrutba, V.; Kobzysta, O.; Kolomiiets, A.; Shevchenko, V. Management of an Automated Air Quality Monitoring System to Achieve Sustainable Development Goals. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference Intelligent Transport Systems: Ecology, Safety, Quality, Comfort, Kyiv, Ukraine, 26–27 November 2024; pp. 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satpathy, I.; Nayak, A.; Jain, V. The green city: Sustainable and smart urban living through artificial intelligence. In Utilizing Technology to Manage Territories; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; Volume 1, pp. 273–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivashchuk, O.A.; Fedorov, V.I.; Goncharov, D.V. Approaches to the development of an automated control system for the adaptation of agricultural areas under the changing greenhouse effect. Math. Stat. Eng. Appl. 2022, 71, 948–956. [Google Scholar]

- Ivashchuk, O.A.; Goncharov, D.V.; Fedorov, V.I. Digital Technologies for Assessing and Predicting the Impact of the Spatiotemporal Distribution of Greenhouse Gases on the Photosynthetic Activity of Crops. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Russian Smart Industry Conference (SmartIndustryCon), Sochi, Russia, 25–29 March 2024; pp. 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinov, I.S.; Ivaschuk, O.A. Approaches to creating environment safety automation control system of the industrial complex. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE 7th International Conference on Intelligent Data Acquisition and Advanced Computing Systems (IDAACS), Berlin, Germany, 12–14 September 2013; pp. 828–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivashchuk, O.A.; Konstantinov, I.S.; Udovenko, I.V. Smart control system of human resources potential of the region. In Smart Education and Smart e-Learning; Springer International Publishing: Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncharov, D.V.; Ivashchuk, O.A.; Kaliuzhnaya, E.V. Development of a Mobile Robotic Complex for Automated Monitoring and Harvesting of Agricultural Crops. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Russian Automation Conference (RusAutoCon), Sochi, Russia, 8–14 September 2024; pp. 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncharov, D.V.; Ivashchuk, O.A.; Reznikov, N.G. Method for modeling and visualization of agricultural crops growth based on augmented reality technology in terms of the greenhouse effect dynamics. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Russian Smart Industry Conference (SmartIndustryCon), Sochi, Russia, 27–31 March 2023; pp. 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncharov, D.V.; Fedorov, V.I.; Ivashchuk, O.O. Methods, Models and Hardware-Software Complex of Distributed Monitoring Based on Iot and Blockchain Technology. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Russian Smart Industry Conference (SmartIndustryCon), Sochi, Russia, 25–29 March 2024; pp. 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Liu, X.; He, X. A global meta-analysis of crop yield and agricultural greenhouse gas emissions under nitrogen fertilizer application. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 831, 154982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Geng, L. Carbon emissions calculation from municipal solid waste and the influencing factors analysis in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 104, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschmann, K.; Zallinger, M.; Fellendorf, M.; Hausberger, S. A new method to calculate emissions with simulated traffic conditions. In Proceedings of the 13th International IEEE Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems, Funchal, Portugal, 19–22 September 2010; pp. 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Beecher, N.; Carpenter, A. Calculator tool for determining greenhouse gas emissions for biosolids processing and end use. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 24, 9509–9515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Suarez, F.; Gentine, P.; Solino-Fernandez, B.; Beucler, T.; Pritchard, M.; Runge, J.; Eyring, V. Causally-informed deep learning to improve climate models and projections. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2024, 129, e2023JD039202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazić, I.; Djurdjević, V.; Tošić, I.; Tošić, M. Impact of soil texture in coupled regional climate model on land-atmosphere interactions. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2025, 156, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyring, V.; Collins, W.D.; Gentine, P.; Barnes, E.A.; Barreiro, M.; Beucler, T.; Zanna, L. Pushing the frontiers in climate modelling and analysis with machine learning. Nat. Clim. Change 2024, 14, 916–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mott, K.A. Sensing of atmospheric CO2 by plants. Plant Cell Environ. 1990, 13, 731–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, K.L.; Seemann, J.R. Plants, CO2 and photosynthesis in the 21st century. Chem. Biol. 1996, 3, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timlin, D.; Paff, K.; Han, E. The role of crop simulation modeling in assessing potential climate change impacts. Agrosys. Geosci. Environ. 2024, 7, e20453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagi, M. Climate change impacts on wheat production: Reviewing challenges and adaptation strategies. Adv. Resour. Res. 2024, 4, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, A.; Hoogenboom, G. Assessing crop management options with crop simulation models based on generated weather data. Agrosyst. Geosci. Environ. 2007, 3, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Zhang, X.; Khanal, S.; Wilson, R.; Leng, G.; Toman, E.M.; Zhao, K. Climate change impacts on crop yields: A review of empirical findings, statistical crop models, and machine learning methods. Environ. Model. Softw. 2024, 179, 106119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petito, M.; Cantalamessa, S.; Pagnani, G.; Pisante, M. Modelling and mapping Soil Organic Carbon in annual cropland under different farm management systems in the Apulia region of Southern Italy. Soil Tillage Res. 2024, 235, 105916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Karimi, M.S.; Mohammed, K.S.; Shahzadi, I.; Dai, J. Nexus between climate change, agricultural output, fertilizer use, agriculture soil emissions: Novel implications in the context of environmental management. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 450, 141801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Chen, Y.; Li, Z.; Duan, W.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y. Optimisation model for sustainable agricultural development based on water-energy-food nexus and CO2 emissions: A case study in Tarim river basin. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 303, 118174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monson, R.K.; Li, S.; Ainsworth, E.A.; Fan, Y.; Hodge, J.G.; Knapp, A.K.; Way, D.A. C4 photosynthesis, trait spectra, and the fast-efficient phenotype. New Phytol. 2025, 246, 879–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, M.; Kordrostami, M.; Ghasemi-Soloklui, A.A.; Eaton-Rye, J.J.; Pashkovskiy, P.; Kuznetsov, V.; Allakhverdiev, S.I. Enhancing photosynthesis and plant productivity through genetic modification. Cells 2024, 16, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubien, D.S.; Von Caemmerer, S.; Furbank, R.T.; Sage, R.F. C4 photosynthesis at low temperature. A study using transgenic plants with reduced amounts of Rubisco. Plant Physiol. 2003, 3, 1577–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, D.; Painter, J.; Potter, M. Automatic Plant Leaf Classification for a Mobile Field Guide. Rapport Technique. Université de Stanford. 2010. Available online: https://stacks.stanford.edu/file/druid:bj600br8916/Knight_Painter_Potter_PlantLeafClassification.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Gélard, W.; Herbulot, A.; Devy, M.; Casadebaig, P. 3D leaf tracking for plant growth monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2018 25th IEEE International Conference on Image Processing, ICIP, Athens, Greece, 7–10 October 2018; IEEE Systems, Man, and Cybernetics Society. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/8451553 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Zhang, S.; Huang, W.; Huang, Y.A. Plant Species Recognition Methods using Leaf Image: Overview. Neurocomputing 2020, 408, 246–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Tsai, P.S.; Cryer, J.E.; Shah, M. Shape-from-shading: A survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1999, 21, 690–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.; Kanade, T. Shape-from-silhouette across time part i: Theory and algorithms. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2005, 62, 221–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chéné, Y.; Rousseau, D.; Lucidarme, P.; Bertheloot, J.; Caffier, V.; Morel, P.; Chapeau-Blondeau, F. On the use of depth camera for 3D phenotyping of entire plants. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2012, 82, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhury, A.; Ward, C.; Talasaz, A.; Ivanov, A.G.; Brophy, M.; Grodzinski, B.; Barron, J.L. Machine vision system for 3D plant phenotyping. ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2018, 16, 2009–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, S.; Behmann, J.; Mahlein, A.K.; Plümer, L.; Kuhlmann, H. Low-cost 3D systems: Suitable tools for plant phenotyping. Sensors 2014, 14, 3001–3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pound, M.P.; French, A.P.; Murchie, E.H.; Pridmore, T.P. Automated recovery of three-dimensional models of plant shoots from multiple color images. Plant Physiol. 2014, 166, 1688–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschalis, A.; Katul, G.G.; Fatichi, S.; Palmroth, S.; Way, D. On the variability of the ecosystem response to elevated atmospheric CO2 across spatial and temporal scales at the Duke Forest FACE experiment. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2017, 232, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangana Gowdra, V.M.; Lalitha, B.S.; Halli, H.M.; Senthamil, E.; Negi, P.; Jayadeva, H.M.; Reddy, K.S. Root growth, yield and stress tolerance of soybean to transient waterlogging under different climatic regimes. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Z.; Zhang, G.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Luo, S.; Zhang, B.; Liu, Z. Comparative study of the quality indices, antioxidant substances, and mineral elements in different forms of cabbage. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwaszenko, S.; Smolinski, A.; Grzanka, M.; Skowronek, T. Airborne particulate matter measurement and prediction with machine learning techniques. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomicheva, D.V.; Zhidkin, A.P.; Komissarov, M.A. Multiscale estimates of soil erodibility variation under conditions of high soil cover heterogeneity in the northern forest-steppe of the Central Russian Upland. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2024, 57, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).