Abstract

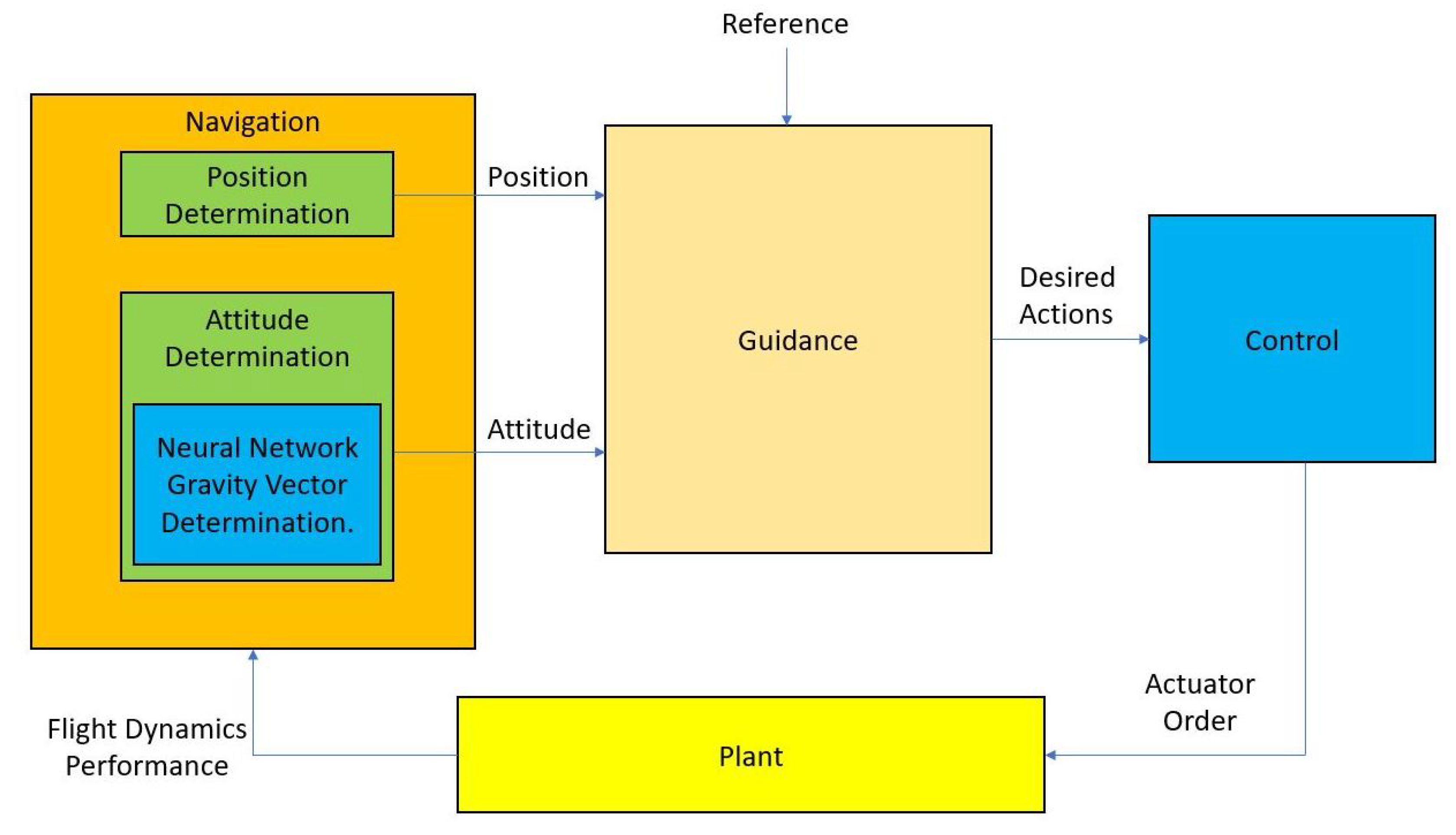

The Guidance, Navigation and Control (GNC) of air and space vehicles has been one of the spearheads of research in the aerospace field in recent times. Using Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) and inertial navigation systems, accuracy may be detached from range. However, these sensor-based GNC systems may cause significant errors in determining attitude and position. These effects can be ameliorated using additional sensors, independent of cumulative errors. The quadrant photodetector semiactive laser is a good candidate for such a purpose. However, GNC systems’ development and construction costs are high. Reducing costs, while maintaining safety and accuracy standards, is key for development in aerospace engineering. Advanced algorithms for getting such standards while eliminating sensors are cornerstone. The development and application of machine learning techniques to GNC poses an innovative path for reducing complexity and costs. Here, a new nonlinear hybridization algorithm, which is based on neural networks, to estimate the gravity vector is presented. Using a neural network means that once it is trained, the physical-mathematical foundations of flight are not relevant; it is the network that returns dynamics to be fed to the GNC algorithm. The gravity vector, which can be accurately predicted, is used to determine vehicle attitude without calling for gyroscopes. Nonlinear simulations based on real flight dynamics are used to train the neural networks. Then, the approach is tested and simulated together with a GNC system. Monte Carlo analysis is conducted to determine performance when uncertainty arises. Simulation results prove that the performance of the presented approach is robust and precise in a six-degree-of-freedom simulation environment.

1. Introduction

Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) signals are widely utilized for aerospace applications. However, reliability decreases as the requirement of the application for which it is designed increases. The main cause producing this effect is the reduced signal/noise relationship caused by the attenuation and loss of the GNSS signal. This basically means that independent sources of data for navigation are needed to ameliorate these negative effects and reduce interference. Inertial Navigation Systems (INS) are a good example of devices which are independent of external perturbations. Particularly, an inertial estimation unit (IMU) is an electronic gadget that measures and reports a body’s specific force, angular rate, and orientation, utilizing a blend of accelerometers, gyroscopes, and sometimes magnetometers. IMUs are normally used in airplanes, including unmanned aeronautical vehicles (UAVs), and spacecraft. However, these systems also feature important lacks, such as frequent incorrect initialization, accelerometer and gyroscope imperfections, which are trigger for cumulative errors and imperfections in implemented dynamics model. Despite of this fact, Inertial Navigation Systems, when hybridized with GNSS receivers to minimize drift, are excellent for GNC data acquisition [1,2].

However, precision and cost are counterposed objectives. Reducing costs, while maintaining safety and accuracy standards, is key for development in aerospace engineering. Advanced algorithms for getting such standards while cutting down costs are are cornerstone. For example, to maintain an acceptable precision level while reducing costs, less precise devices may substitute expensive systems as long as GNSS signal is reachable and persistent to update the inertial system. However, many scenarios feature high uncertainty and alternatives are needed. An option to satisfy accuracy needs and budget limitations is to merge data of a few low cost sensors, which makes possible increases in accuracy levels.

The advantages of coordinated combination of information have appeared in numerous air applications [3]. For example, information combination strategies for six degrees of freedom rockets are depicted in [4]. The main issues in using various sorts of INS augmented with GNSS updates have been considered by [5]. Notwithstanding INS/GNSS hybridization, a set of nonlinear observers are presented by [6]. Note that, in case there are various sensors available, they may be additional contributions to a filter, e.g., the Kalman filter [1,2].

As it is shown in [1,2], the need to develop new Guidance, Navigation and Control (GNC) frameworks has fostered research on stability and controllability of aerospace vehicles. A novel guidance law is presented in [7], where only observations of line-of-sight angle and its rate of change coming from a seeker are employed. Ref. [8,9] present GNC cooperative techniques based on the conventional Proportional Navigation (PN). In [10] a target-follower engagement is considered, in which the target is followed while it tries to prevent interception. An attitude control-framework device for a spinning sounding rocket, which depends on a proportional, integral, and derivative (PID) controller, is created in [11]. Proportional-derivative GNC laws for the terminal phases of flight are proposed in [12,13]. In [14], a limited time concurrent sliding-mode GNC law is introduced. An overall scheme concerning the guidance and autopilot modules for a class of spin-stabilized balance controlled devices is introduced in [15].

Yet, even in GNSS/IMU hybrid devices, there exist negative influences, such as irregular estimations, which might be predominant during terminal guidance. Other methods, which are based on image recognition using multispectral cameras and other sensors, may be used in navigation for aerospace applications [16]. However, they usually feature high costs. Hence, advancement on new algorithms which may easily fulfill the required precision levels and budget limitations is a foundation in research. For instance, there are recent advances which consist of incorporating IMU, GPS, and laser guidance capacity, offering high accuracy and all-weather capacity [17,18].

Laser guidance may be provided by means of Semi Active Laser Kits (SAL). These devices are applied in many designing areas, such as calculating rotational speed of objects and estimating dynamics of laser spots [19,20]. The bonus of these kits is their favorable position during the last periods of the guidance, when they can provide high precision for GNC systems.

Therefore, it can be stated that sensor hybridization techniques [16,21] for viable and robust estimations are a current need when autonomy, accuracy, and minimal cost are to be achieved. However, also note that as the number of sensors to employed increases, the cost of system also increases. In this sense, Machine Learning (ML) techniques come onto the scene. They offer multitudinous options and innovative solutions of particular interest for GNC applications, where their foray is still latter and shallow, yet with no doubt promising. The utilization of ML strategies for the estimation of parameters dependent on the dynamics of aerial vehicles presents the bit of leeway that once the algorithm is calibrated or trained, it is not important to know the physical-mathematical establishments that rule the flight mechanics. Given the input signals, ML algorithms may restore the data that can later be utilized within the GNC system, such that the subsequent solutions will fit the genuine output [22,23]. Taking benefit of these facts, a reduced set of sensors may be selected to work together with ML algorithms, all while safety and accuracy standards are matched, and complexity and costs are decreased.

However, the application of these strategies to a wide set of scenarios, which may also include uncertain conditions, depends largely on the representativity and amount of input and output data employed for training ML algorithms. This fact implies that desired performance stability and convergence is to be restricted to the trained mission envelope. Other approaches, which could ensure convergence and stability parameters under the proposed uncertain conditions, might also be employed for this type of application. For instance, adaptive control that uses adaptation laws to online estimate unknown system parameter variations for various mission envelopes [24,25,26].

Altogether, the objective of this paper is to improve current guidance strategies applying a powerful hybridization approach, which also introduces ML to enable attitude determination with a reduced availability of sensors, namely GNSS, accelerometer and semiactive laser quadrant photo-detectors. In particular, neural networks (NN) are implemented to precisely estimate the gravity vector to be combined with velocity and line of sight vectors in order to determine the attitude or rotation of the vehicle without needing gyroscopes. Note that the mentioned vectors need to be obtained in two different reference frames because otherwise the attitude determination problem cannot be solved.

Contributions

The main contribution of this scientific research is the application of Machine Learning techniques, i.e., neural network (NN) algorithms, to hybridize GNSS, accelerometer and semiactive laser quadrant photo-detectors signals. The role of the neural networks is to predict the gravity vector to estimate the attitude of the vehicle. Consequently, the advantage of such a hybrid system over the traditional ones, which are usually based on GNSS and IMUs, is the capability of eliminating gyros, which may be expensive and too sensitive for high demanding maneuvers and not reliable at all during some stages of flight.

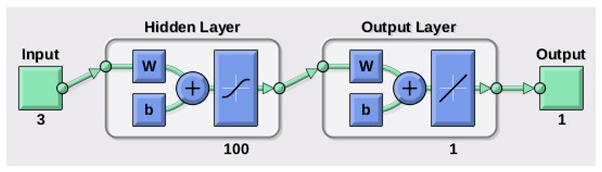

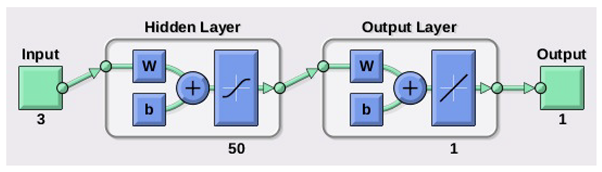

The presented approach relies on neural networks and training algorithms to predict the gravity vector in body fixed axes while the vehicle is flying. The three components of the acceleration of the vehicle in body fixed axes are the inputs for the NN. After that, the predicted gravity vector is processed together, by means of a hybridisation algorithm, with velocity and line of sight vector to determine body rotation or attitude.

To reproduce the flight dynamics of an aerial vehicle, a nonlinear mathematical model is proposed, which considers nonlinear aerodynamic forces and moments and that has been validated to build up realistic conditions for simulation experiments [1,2]. On top of that, a robust double-input double-output control algorithm is employed to manage coupling among the normal and lateral nonlinear dynamics.

Note that the presented approach depends on the amount of available data for training, which means stability and convergence may be restricted to the trained mission envelope. However, note that training has been performed for a wide variety of launching, flight, and destination point conditions to resemble realistic settings, i.e., for a comprehensive set of missions. Overall, the methodology results in good enough quality results, even including good response to uncertainty in several conditions and characteristics, i.e., showing good GNC performance. Therefore, the presented research poses a path for a generalized and systematic application of NN/Machine Learning in GNC systems.

2. Vehicle Modeling

This section is dedicated to the vehicle description, the flight dynamics model, and sensor and actuation models.

2.1. Definition of the Vehicle

The proposed GNC approach is applied to an aerial vehicle which features a maneuvering system composed of four canard surfaces, which is roll-decoupled from the main body of the vehicle. The motivation for this aerodynamic configuration is deeply explained in [1]. Note a canard is a small winglike surface attached to an aircraft forward of the main wing to provide extra stability or control, usually replacing the tail. Here, canards are decoupled 2 by 2, to produce control force and its related torque (see [1] for more details on this).

Table 1 shows some characteristic parameters of the vehicle, including thrust typical parameter values, vehicle and fuel mass, inertia, and aerodynamic parameters. These parameters are obtained from fluid dynamics numerical simulations, experimental measurements, and wind tunnel verification (see [1] for clarifications). Note that, to keep continuity and derivability on aerodynamic coefficients and thrust, a cubic splines based interpolation method has been employed at intermediate points. According to the shown moments of inertia, the vehicle features planes of symmetry.

Table 1.

Aerial vehicle parameters.

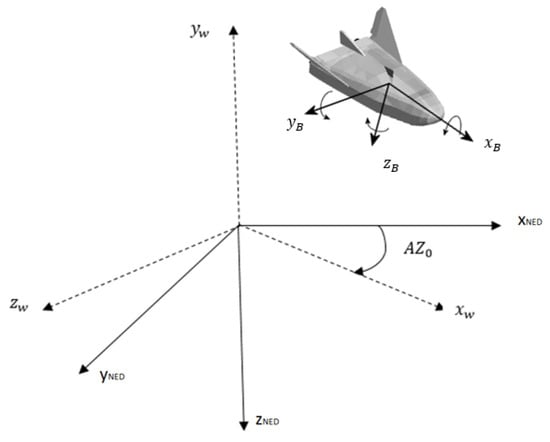

2.2. Equations of Flight Mechanics

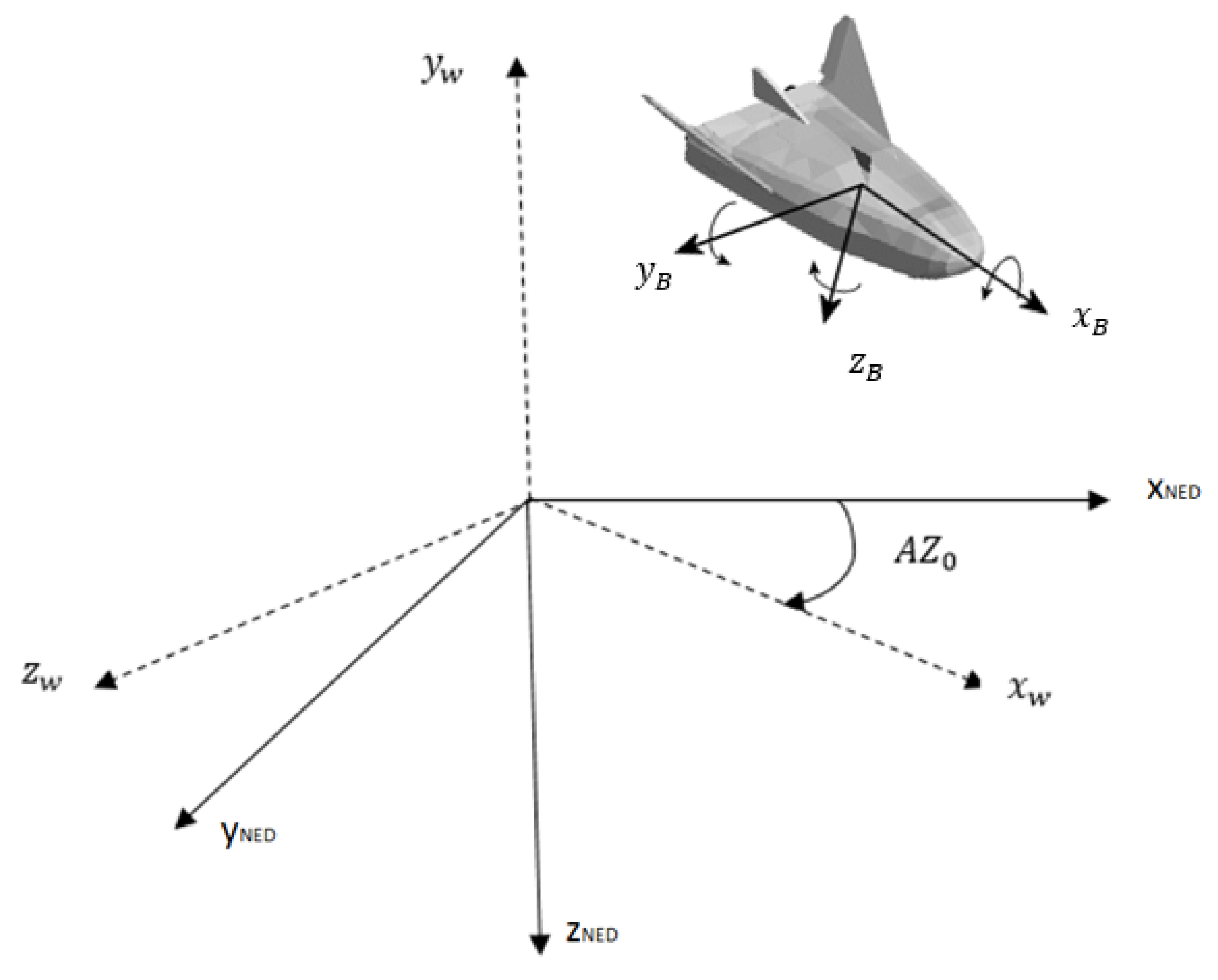

To construct the equations of flight, three reference frames are defined to project forces and moments: NED axes, working axes and body axes. NED axes, which are ground axes, are depicted by sub index . They are defined by pointing north, orthogonal to and pointing nadir, and yielding a clockwise trihedron. Working axes are represented by sub index w. They are given by pointing to the destination point, orthogonal to and pointing apex, and forming a clockwise trihedron. is the initial azimuth, i.e., the azimuth between and . Body axes are depicted by sub index b. pointing forward and contained in the plane of symmetry of the vehicle, orthogonal to pointing down and contained in the plane of symmetry of the vehicle, and shaping a clockwise trihedron. The origin of body axes is located at the gravity center of the vehicle and they are rigid coupled to the roll-decoupled control device. Figure 1 shows the previously defined axes systems.

Figure 1.

The three employed reference frames.

Next, flight dynamics equations are described. Note that these equations are compliant with the standard convention in [27]. Because the vehicle is assumed to be rigid, classical mechanics theory is employed. The Newton–Euler equations describe the combined translational and rotational dynamics of a rigid body. These laws, which are given by six equations, relate the motion of the center of gravity of a rigid body with the sum of forces and moments acting on the rigid body.

Equation (1) shows total external forces and moments acting on the vehicle: is the lift force, is the drag force, is the pitch damping force, is the Magnus force, is the thrust force, is the weight force, is the Coriolis force, the is pitch damping moment, is the overturn moment, is the Magnus moment, and is the spin damping moment.

For the computational experiments in this paper, the external forces in working axes are shown in expression (2), where is the lift force linear coefficient, is the lift force cubic coefficient, is the total angle of attack, is the drag force linear coefficient, is the drag force square coefficient, is the vehicle angular momentum in working axes, are the vehicle inertia moments in body axes, is the pitch damping force coefficient, is the Magnus force coefficient, is vehicle pointing vector in working axes, is the gravity vector in working axes, is earth’s angular speed vector, is vehicle velocity in working axes, d is the reference surface of the vehicle, is the air density, and m is the mass of the vehicle. Note that, is the unitary vector of the axis, and is the gravity vector in working axes. Be aware they are nonlinear functions of the variables describing the movement of the vehicle, such as aerodynamic speed, total angle of attack, Mach number, and aerodynamic parameters.

Similarly, the equations in (3) show the mathematical expressions for the moments, including overturning, pitch damping, Magnus, spin damping, and variables and parameters. Here, is the pitch damping moment coefficient, is the overturning moment linear coefficient, is the overturning moment cubic coefficient, is the Magnus moment coefficient and is the spin damping moment coefficient.

Control forces () and moments () are obtained from the maneuvering system, which is composed of four canard surfaces. Therefore, the contribution of each of them is summed to obtain the total control forces and moments.

The expressions in (4) show the mathematical functions for control forces and moments, where and are the force and moments coefficients of the canard surface respectively, is the normal vector of each canard, and is the deflection angle of the canard surface. Here, is vehicle velocity in body axes.

As stated before, a Newton-Euler approach is used to formulate the equations of motion of the aerial vehicle. These equations are in (5). Note that the body-fixed coordinate system (denoted by frame b) and the flat-Earth coordinate system (denoted by frame e) are related by Euler yaw (), pitch (), and roll () angles.

In Equations (5), stands for vehicle speed expressed in body axes, for angular speed of the vehicle in body axes, and for the angular momentum also in body axes. Recall that control and external forces and control and external moments must be expressed in body axes also to be employed in Equations (5).

2.3. Sensors Models

As exposed in the introduction, this research aims at simplifying navigation systems. Here, this means reducing the need for complex and/or expensive sensors. A gyroscope is a device used for measuring orientation and angular velocity, and it is widely employed in navigation systems. However, their precision downgrades for high-dynamics aerial platforms meanwhile costs increase if performance is to be maintained. Therefore, the objective is to avoid them by fusing information from GNSS sensors, accelerometers, and photo-detector signals to improve vehicle navigation performance in terms of accuracy. This section aims at describing the employed models for these sensors.

2.3.1. Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS)

The GNSS sensor is modeled as a random noise and a bias added to the model calculated position. Note that these systems have typical accuracy of 3 m; therefore, the random noise and bias parameters have been adjusted to satisfy that performance. Because it is not the objective of this paper to model such a sensor, the reader is referred to [2,28] for more details on this.

These kind of sensors provide good performance during intermediate phases of flight and are employed to determine the line of sight vector expressed in NED axes. Note that GNSS sensors also provide velocity vector in NED axes. This vector is also modeled as a random noise and a bias of 0.1 ms, which resembles real performance of these sensors.

2.3.2. Accelerometers

An accelerometer is a device that measures acceleration, i.e., the rate of change of velocity of the vehicle in its own instantaneous reference frame. They are modeled as a random noise and bias of 0.001 ms which resembles real performance of these sensors. Because they provide the acceleration vector expressed in body axes, velocity vector expressed in body triad can be obtained after integration of each of its components along time.

In addition, the magnitudes obtained from accelerometers will be used in the gravity vector estimation approach. As it is explained in the following sections, the velocity vector module is required to estimate it.

2.3.3. Semiactive Laser Kit

Laser guidance may be used to guide a vehicle to a target by means of a laser beam. With this method, a laser is kept pointed at the objective and the laser radiation bobs off the objective and is dispersed every which way. At the point when the vehicle is close enough for a portion of the reflected laser energy from the objective to arrive at it, a laser seeker detects which direction this energy is coming from and provides a signal to correct the trajectory towards the source. The device seeking the laser and providing the signal is a semiactive laser kit.

The signal provided by this sensor features the centroid of the laser footprint in the photo-detector of the kit, which is composed of four photodiodes that convert light into an electrical current. To estimate its coordinates, the produced electrical intensities in the photodiodes ( and ) are employed, which rely upon the illuminated area. These coordinates can be determined as [17], and from them, it is possible to obtain the measured radial distance, . Notwithstanding, real coordinates differ from those calculated, although the transformation is conformal [17]. To obtain the real radial distance, , the following mathematical functional relationship may be employed: . Then, cubic splines based interpolation is applied to obtain a continuous relationship. Equations (6) are utilized to estimate and (see [17] fore more details on this), which are the real spot center coordinates:

where the physical radius of the photo-detector of the kit is given by . Consequently, the line of sight vector projected in body axes may be calculated from and and also from the distance of the photo-detector of the kit to the center of mass of the vehicle.

Note that the signal of this sensor is only available during the terminal phase of the flight. However, it is during final stages of flight when errors of 3 m in positioning target and vehicle induces enormous errors. In this way, an accurate terminal guidance sensor, for example, a semiactive laser kit, is suggested for these last flight stages. This semiactive laser sensor, in combination with GNSS and accelerometers, will provide an accurate determination of the line of sight, especially in the terminal phase. For that purpose, the signals of these sensors’ must be hybridized.

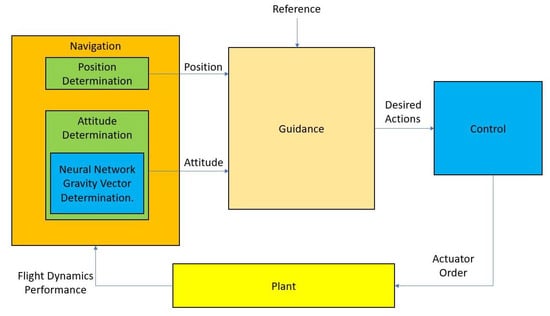

Next, GNC algorithms are presented. At their kernel, neural networks are implemented to determine gravity vector in two reference frames in order to determine vehicle attitude. In addition, hybridization algorithms are applied to sensors’ signals to improve precision.

4. Numerical Simulations

The described nonlinear dynamics are integrated forward in time utilizing a fixed time step Runge–Kutta method of fourth grade to get a single flight path. [1] shows the validation of this modeling and solving approach for aerial platforms. To demonstrate the precision of the novel methodology introduced in this research, which is based on neural networks, the obtained results are compared to the obtained outcomes in [29]. The methodology in [29] features a Kalman based hybridization [43,44] of GNSS, IMU and semiactive laser quadrant photo-detector sensors. To integrate the equations of motion and their interactions with GNC system and environment, MATLAB/Simulink R2020a on a personal computer with a processor of 2.8 Ghz and 32 GB RAM is used.

The remainder of this section is separated in two subsections. The first one presents the noncontrolled trajectories to which the developed navigation, guidance, and control algorithms will be applied. The second one performs Monte Carlo simulations of ballistic flights, Kalman hybridization based controlled flights, and neural networks based controlled flights. Moreover, an ideal controller without induced errors in the line of sight is also developed to compare results with ideal results.

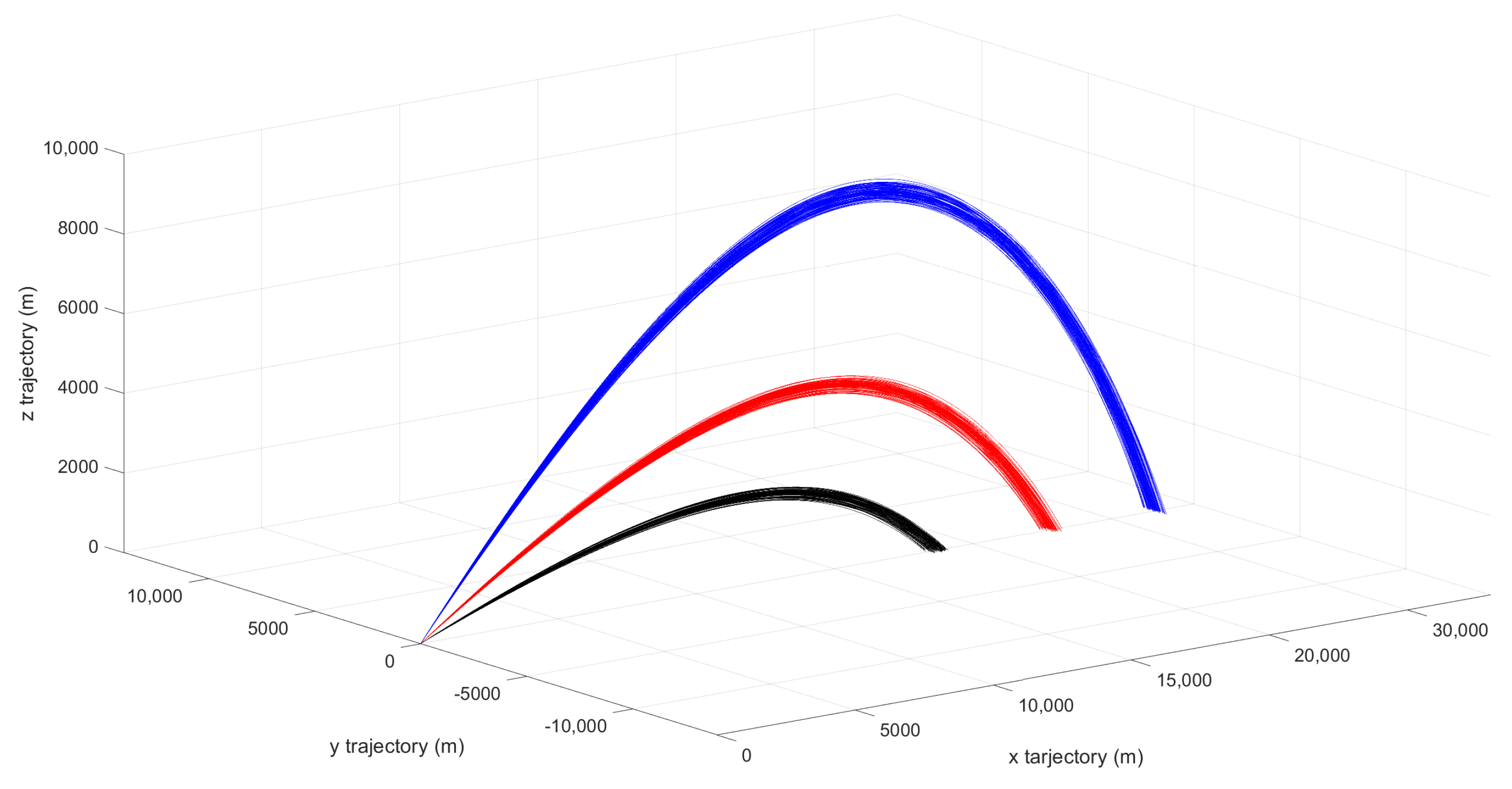

4.1. Noncontrolled Trajectories

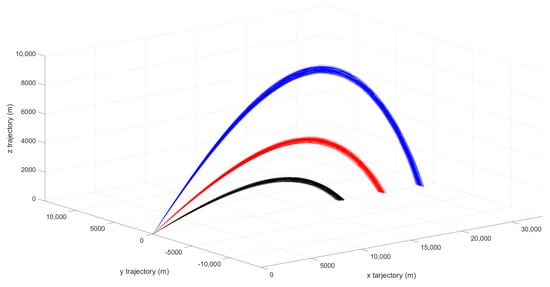

Three nominal trajectories are established to test the developed approach. Each one differs in its initial pitch angle: 20, 30 and 45. Destination points are at 18,790 m, 23,007 m, and 26,979 m, respectively. In order to compensate Coriolis and gyroscopic forces, initial lateral correction is set to 0.15, 0.19 and 0.31, respectively. Figure 3 shows many of these trajectories in a 3D setting for different settings.

Figure 3.

Noncontrolled flights for 20 (black), 30 (red) and 45 (blue) initial pitch angles.

4.2. Monte Carlo Simulations

Noncontrolled flights have been validated against real data provided by the Spanish air force. Monte Carlo simulations are performed to calculate closed-loop performance over a full range of uncertainty settings, which have been defined with the support of the Spanish air force. These settings model the potential uncertainty that can arise in aspects such as initial conditions, sensor information procurement, weather conditions, and thrust properties. Note that, details on uncertainty models for sensors are given in the previous sections. Table 6 shows mean and standard deviation for the rest of the considered uncertain parameters.

Table 6.

Monte Carlo simulation parameters.

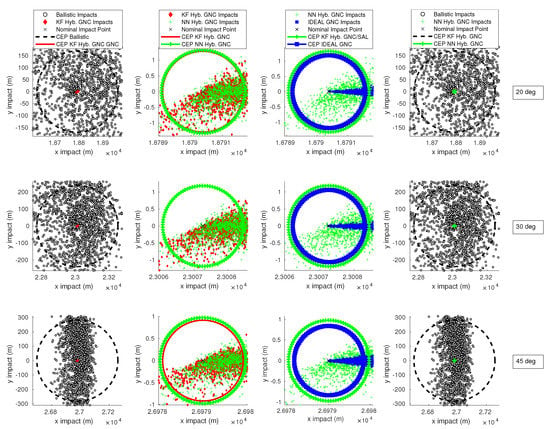

A set of 2000 flights is performed for each of the following approaches: noncontrolled flights, Kalman hybridization based controlled flights, neural network based controlled flights, and ideally controlled flights. Simulations are run for each of the initial pitch angles. Note that the previously used data for neural network training is different from the data employed in the simulations in this section.

4.3. Discussion

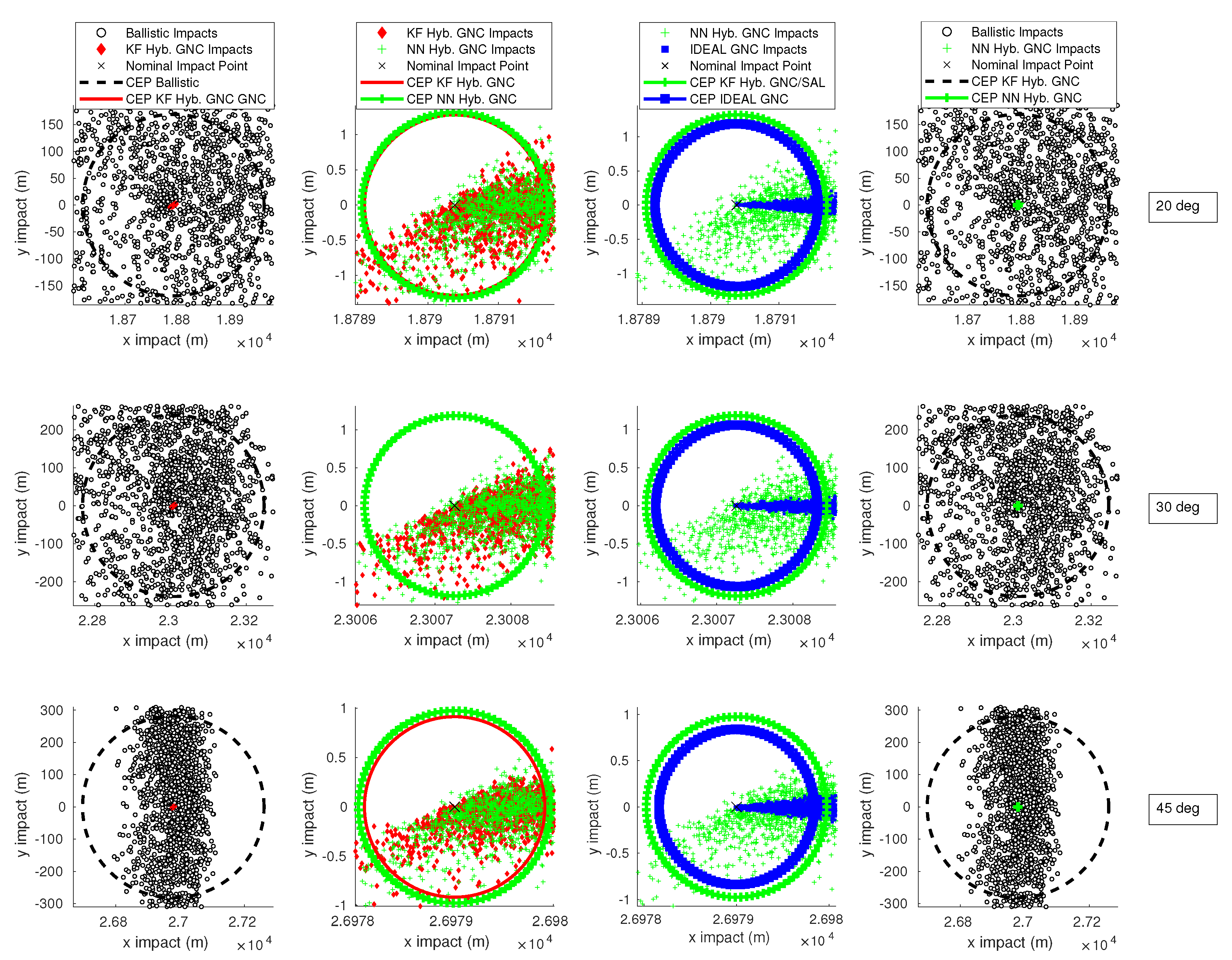

Results for noncontrolled trajectories are shown in Figure 3, which depicts destination point dispersion patterns. This figure shows the ballistic trajectory that the vehicle follows for three different launch angles without using the control system at all, that is, it shows the flight of the system before implementing the improvements provided by the GNC system. The circular error probable (CEP), which is defined as the radius of a circle, centered on the mean, whose boundary is expected to include the landing points of 50% of the flights. The CEP is employed as a quality check parameter at the final step of the simulation as it is a valid reference for any utilized method. Indeed, the lower the CEP is the better the global GNC device is.

Table 7 displays the CEP for noncontrolled flights, Kalman hybridization based controlled flights and ideally controlled flights for each of the initial pitch angles.

Table 7.

The CEP for noncontrolled flights, Kalman hybridization based controlled flights and ideally controlled flights for 20, 30 and 45 initial pitch angles.

Analyzing Table 7, it may be concluded that the CEP increases with target distance for noncontrolled flights, as expected. However, it almost remains constant for either Kalman based or ideally controlled flights, which means the use of an appropriate GNC device eliminates the correlation between the CEP and the distance to the objective. Recall, the main purpose is to show that these results are reproducible when employing machine learning and when reducing the availability of sensors.

Table 8 shows again the CEP for different trajectories, now as obtained by the novel presented approach. Each row, excluding the first one, which shows the headings of the columns, displays the resulting CEPs for every combination of trajectory and NN training algorithm. The first column in the table identifies the trajectory, the second one the training algorithm, the third one the CEP for the NN architecture in method 1, and the last one the CEP for the NN architecture in method 2. One of the main conclusions drawn from Table 8 is that the results for the SCG training algorithm present an unacceptable big CEP, which means low accuracy when reaching destination. Consequently, this training algorithm should be discarded in this case. Indeed, we recover results equivalent to a defective GNC system, even showing worse performance than ballistic flights. Several tests and a hyperparametric analysis were conducted, and it is observed that these kinds of errors were systematic, concluding that this training algorithm does not match well with the fed data to the NN. However, the results from BR and LM training algorithms show a good behavior throughout the trajectory, which means level of accuracy at destination is high. Diving into the numerical results in Table 8, it can be stated that the presented novel approach, which relaxes sensor requirements, is even able of outperforming the Kalman hybridization based approach. It can also be observed that the results are coherent with the training results depicted in Table 4. For example, the poor MSE and R values for the SCG training algorithm are reflected in the unacceptable GNC device results. Comparing the obtained CEPs to what it was obtained in [1,22,29], it can be concluded that the results here are of the same order of magnitude and that the NN algorithms are viable for these type of applications.

Table 8.

The CEP in neural network based controlled flights for the different methods and training algorithms for 20, 30 and 45 initial pitch angles.

As a summary, results for ballistic trajectories and comparisons between different approaches are shown in Figure 4. It is composed of four columns and three rows of subfigures. Each row features a different initial pitch angle. The first column of subfigures compares ballistic flights against Kalman hybridization assisted flights, the second one compares Kalman hybridization against neural network hybridization, the third one neural network hybridization against ideal controller, and the last one ballistic flights against neural network hybridization assisted flights. Note that, even with an ideal controller, which features perfect information on the attitude angles, there are still errors associated to the aerodynamic response of the vehicle.

Figure 4.

Detailed shots for different algorithms.

5. Conclusions

A novel methodology, which depends on an innovative hybridization among several sensor signals, has been proposed. At the core of the approach, neural networks are employed to get estimations of the gravity vector, which allows avoiding the use of gyroscopes. Traditional GNSS/IMU frameworks feature little errors of up to one meter, which may imply huge mistakes in line of sight vector computation when separation to the objective is small. With the proposed approach the exactness of line of sight calculation can be improved during the terminal GNC, enhancing the accuracy at the destination point, while sensor needs are lowered.

The proposed approach employs information gathered from GNSS, acceloremeters, and a semiactive laser kit. With that information, two different neural network architectures are applied to estimate the gravity vector in order to determine the attitude of the vehicle. Three training algorithms have been addressed to tune the parameters in the neural networks. In total, six different strategies are developed for estimating the gravity vector along the trajectory. In addition, because the methodology allows for determining attitude in two ways, the information is hybridized with the aim of augmenting precision.

This innovative methodology is integrated into a two-phase guidance algorithm for aerial vehicles, which provides the required input data for the GNC system. The guidance law is founded on a constant glide angle and on a modified proportional law. The control algorithm is based on a robust and effective but simple double-input double-output device. Overall, the resulting GNC system presents excellent values regarding dispersion at the destination objective, significantly increasing the precision for noncontrolled flights, as expected, but also matching accuracy as provided by other GNC systems requiring more sensors on-board. Note that results also show good behavior of the system under uncertainty conditions. Summarizing, the developed approach, which is based on neural networks, shows that precision levels can be matched or improved as compared to other methodologies.

Future research will address the increase of the use of neural networks in other modules of GNC algorithms to further simplify the overall architecture.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.d.C.; methodology, R.d.C. and L.C.; software, L.C.; validation, R.d.C.; formal analysis, R.d.C. and P.S.; investigation, R.d.C. and P.S.; resources, L.C.; data curation, R.d.C. and P.S.; writing–original draft preparation, L.C.; writing–review and editing, R.d.C.; visualization, R.d.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Project Grant F663—AAGNCS by the “Dirección General de Investigación e Innovación Tecnológica, Consejería de Ciencia, Universidades e Innovación, Comunidad de Madrid” and “Universidad Rey Juan Carlos”.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Lieutenant Colonel Jesús Sánchez (NMT) of the National Institute for Aerospace Technology (INTA) for the solid modeling of the concept.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- De Celis, R.; Cadarso, L.; Sánchez, J. Guidance and control for high dynamic rotating artillery rockets. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2017, 64, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Celis, R.; Cadarso, L. Hybridized attitude determination techniques to improve ballistic projectile navigation, guidance and control. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2018, 77, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltz, E.L.; Buede, D.M. Data fusion and decision support for command and control. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1986, 16, 865–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.V.; Tyan, M.; Lee, J.W. Efficient Framework for Missile Design and 6DoF Simulation using Multi-fidelity Analysis and Data Fusion. In Proceedings of the 17th AIAA/ISSMO Multidisciplinary Analysis and Optimization Conference, Washington, DC, USA, 13–17 June 2016; p. 3365. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, G.T.; Phillips, R.E. INS/GPS Integration Architecture Performance Comparisons. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/INS%2FGPS-Integration-Architecture-Performance-Schmidt-Phillips/1cb8e282e25d90048c1232778f3fbb21eb4c9de8 (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Bryne, T.H.; Hansen, J.M.; Rogne, R.H.; Sokolova, N.; Fossen, T.I.; Johansen, T.A. Nonlinear observers for integrated INS∖/GNSS navigation: Implementation aspects. IEEE Control Syst. Mag. 2017, 37, 59–86. [Google Scholar]

- Gaudet, B.; Furfaro, R.; Linares, R. Reinforcement learning for angle-only intercept guidance of maneuvering targets. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2020, 99, 105746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhou, R. Unified approach to cooperative guidance laws against stationary and maneuvering targets. Nonlinear Dyn. 2015, 81, 1635–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creagh, M.A.; Mee, D.J. Attitude guidance for spinning vehicles with independent pitch and yaw control. J. Guid. Control. Dyn. 2010, 33, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalumov, V. Cooperative Online Guide-Launch-Guide Policy in a Target-Missile-Defender Engagement using Deep Reinforcement Learning. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2020, 104, 105996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.I.; Sun, B.C.; Tahk, M.J.; Lee, H. Control design of spinning rockets based on co-evolutionary optimization. Control Eng. Pract. 2001, 9, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechevin, N.; Rabbath, C.A. Robust discrete-time proportional-derivative navigation guidance. J. Guid. Control. Dyn. 2012, 35, 1007–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Gao, G. Partial integrated missile guidance and control with state observer. Nonlinear Dyn. 2015, 79, 2497–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, M.; Chen, Z. Finite-time convergent guidance law with impact angle constraint based on sliding-mode control. Nonlinear Dyn. 2012, 70, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoulis, S.; Gassmann, V.; Wernert, P.; Dritsas, L.; Kitsios, I.; Tzes, A. Guidance and control design for a class of spin-stabilized fin-controlled projectiles. J. Guid. Control. Dyn. 2013, 36, 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, S.; Shabani, F.; Simon, D. Multirate multisensor data fusion for linear systems using Kalman filters and a neural network. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2014, 39, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Celis, R.; Cadarso, L. Spot-Centroid Determination Algorithms in Semiactive Laser Photodiodes for Artillery Applications. J. Sens. 2019, 2019, 7938415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, Z.; Sun, T.; Yang, H.; Han, K.; Hu, B. Optical system design with common aperture for mid-infrared and laser composite guidance. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Photonics and Optical Engineering, Xi’an, China, 14–17 October 2016; International Society for Optics and Photonics: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2017; Volume 10256, p. 102560S. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, X.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, Y. Remote evaluation of rotational velocity using a quadrant photo-detector and a DSC algorithm. Sensors 2016, 16, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esper-Chaín, R.; Escuela, A.M.; Fariña, D.; Sendra, J.R. Configurable quadrant photodetector: An improved position sensitive device. IEEE Sens. J. 2015, 16, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razmi, H.; Afshinfar, S. Neural network-based adaptive sliding mode control design for position and attitude control of a quadrotor UAV. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2019, 91, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano-López, P.; de Celis, R.; Fuentes, M.; Cadarso, L.; Barea, A. Strategies for high performance GNSS/IMU Guidance, Navigation and Control of Rocketry. In Proceedings of the 8th European Conference for Aeronautics and Space Sciences, Madrid, Spain, 1–4 July 2019; Volume 1, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.; Dongare, V. Aircraft neural modeling and parameter estimation using neural partial differentiation. Aircr. Eng. Aerosp. Technol. 2018, 90, 764–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreres, G.; Hardier, G.; Seren, C. Adaptive control of a civil aircraft through on-line parameter estimation. In Proceedings of the 2016 3rd Conference on Control and Fault-Tolerant Systems (SysTol), Barcelona, Spain, 7–9 September 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 798–804. [Google Scholar]

- Hardier, G.; Ferreres, G.; Sato, M. On-line parameter estimation for indirect adaptive flight control: A practical evaluation of several techniques. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Conference on Control Technology and Applications (CCTA), Montreal, QC, Canada, 24–26 August 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 180–187. [Google Scholar]

- Ignatyev, D.I.; Shin, H.S.; Tsourdos, A. Two-layer adaptive augmentation for incremental backstepping flight control of transport aircraft in uncertain conditions. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2020, 105, 106051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North Atlantic Treaty Organization, N. Standardization Agreement (STANAG 4355). In The Modified Point Mass Trajectory Model; NATO Headquarters: Brussels, Belgium, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- De Celis, R.; Cadarso, L. Attitude determination algorithms through accelerometers, GNSS sensors, and gravity vector estimator. Int. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2018, 2018, 5394057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Celis, R.; Cadarso, L. GNSS/IMU laser quadrant detector hybridization techniques for artillery rocket guidance. Nonlinear Dyn. 2018, 91, 2683–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britting, K.R. Inertial Navigation Systems Analysis; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.Y.; Zhang, Y.A.; Gu, W.J. An approach to integrated guidance/autopilot design for missiles based on terminal sliding mode control. In Proceedings of the 2004 International Conference on Machine Learning and Cybernetics (IEEE Cat. No. 04EX826), Shanghai, China, 26–29 August 2004; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2004; Volume 1, pp. 610–615. [Google Scholar]

- Jankovic, M.; Paul, J.; Kirchner, F. GNC architecture for autonomous robotic capture of a non-cooperative target: Preliminary concept design. Adv. Space Res. 2016, 57, 1715–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yao, H.; Liu, Y. Aircraft dynamics simulation using a novel physics-based learning method. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2019, 87, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, J.; Taipalmaa, J.; Gerasimenko, M.; Pyattaev, A.; Ukonaho, M.; Zhang, H.; Raitoharju, J.; Passalis, N.; Perttula, A.; Aaltonen, J.; et al. aColor: Mechatronics, Machine Learning, and Communications in an Unmanned Surface Vehicle. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.00745. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, N.; Yadav, A.; Kumar, M. An Introduction to Neural Network Methods for Differential Equations; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tatar, M.; Masdari, M. Investigation of pitch damping derivatives for the Standard Dynamic Model at high angles of attack using neural network. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2019, 92, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, M.F. A Scaled Conjugate Gradient Algorithm for Fast Supervised Learning; Aarhus University, Computer Science Department: Aarhus, Denmark, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- MacKay, D.J. Bayesian interpolation. Neural Comput. 1992, 4, 415–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foresee, F.D.; Hagan, M.T. Gauss-Newton approximation to Bayesian learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Neural Networks (ICNN’97), Houston, TX, USA, 12 June 1997; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1997; Volume 3, pp. 1930–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moré, J.J. The Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm: Implementation and theory. In Numerical Analysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1978; pp. 105–116. [Google Scholar]

- Kanzow, C.; Yamashita, N.; Fukushima, M. Withdrawn: Levenberg–marquardt methods with strong local convergence properties for solving nonlinear equations with convex constraints. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2005, 173, 321–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahba, G. A least squares estimate of satellite attitude. SIAM Rev. 1965, 7, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkowski, P.; Pietrzykowski, Z.; Magaj, J.; Mąka, M. Fusion of data from GPS receivers based on a multi-sensor Kalman filter. Transp. Probl. 2008, 3, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Jaroś, K.; Witkowska, A.; Śmierzchalski, R. Data fusion of GPS sensors using particle Kalman filter for ship dynamic positioning system. In Proceedings of the 2017 22nd International Conference on Methods and Models in Automation and Robotics (MMAR), Miedzyzdroje, Poland, 28–31 August 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 89–94. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).