Abstract

The built environment (BE) encompasses an enormous volume and substantial material mass. However, structures within it typically serve single, limited functions. Enhancing these structures with multifunctional capabilities holds significant potential for achieving broader sustainability goals and creating impactful environmental benefits. Among these potential multifunctional applications, carbon capture, reduction, and storage are especially critical, given the current built environment’s substantial contribution of approximately 40% of global energy and CO2 emissions. Keeping this potential in view, this comprehensive review critically evaluates carbon management strategies for the built environment via three interrelated approaches: carbon capture (via photosynthesis, passive concrete carbonation, and microbial biomineralization), carbon storage (employing carbonation curing, mineral carbonation, and valorization of construction and demolition waste), and carbon reduction (integrating industrial waste, alternative binders, and bio-based materials). The review also evaluates the potential of novel direct air-capture materials, assessing their feasibility for integration into construction processes and existing infrastructure. Key findings highlight significant advancements, quantify CO2 absorption potentials across various construction materials, and reveal critical knowledge gaps, thereby providing a strategic roadmap for future research direction toward a low-carbon, climate-resilient built environment.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

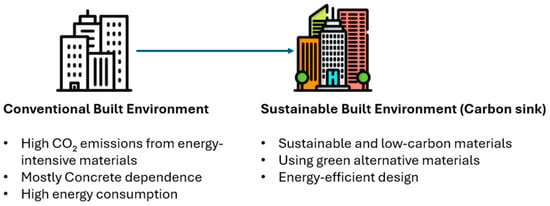

Climate change has become a significant topic of discussion in the 21st century, as it is linked to many types of extreme weather and natural disasters. The report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) stated that the temperature of the Earth had been raised by about 1.0 °C in comparison to pre-industrial levels, with suggestions that if the current trend persists, an increase of 0.2 °C per decade is assured to occur [1]. This warming has shifted extreme weather events, including rising sea levels and decreased biodiversity. There has been an estimated increase of 48% in emissions of greenhouse gases, especially carbon dioxide (CO2), since 1750, primarily due to human activities [2,3]. The built environment (BE) comprises all human-created surroundings, such as the buildings and infrastructure (Figure 1) has a significant bearing when it comes to the issue of climate change.

Figure 1.

The difference between the current BE and the sustainable BE.

BE accounts for almost 40% of global energy and process-related CO2 emissions [4,5]. Ordinary Portland cement (OPC) is among the major contributors, which emits nearly 1 ton of CO2 per ton produced [6]. 25 billion tons of concrete are consumed annually worldwide, making it the second most often utilized construction material today, behind water [7]. This situation brings to the forefront the importance of finding ways to enhance the environmental sustainability of the construction sector. There is a growing movement to turn the built environment into a carbon sink [8]. Over 1000 cities and 130 countries have committed to achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 [9,10,11], which means that the built environment would capture more carbon than it emits, creating a positive impact on our planet. Carbon capture and storage (CCS) is a process that captures CO2 emissions from significant sources such as power plants, natural gas processing facilities, and industrial operations.

There are three primary techniques for CO2 removal: post-combustion, where CO2 is separated from flue gases after fuel is burned; pre-combustion, which captures CO2 before combustion by converting fuel into hydrogen and CO2; and oxy-fuel combustion, which burns fuel in pure oxygen, producing a CO2-rich exhaust that is easier to capture [12]. Once captured, CO2 is transported and stored underground in depleted oil and gas reservoirs, deep saline aquifers, or coal seams to prevent its release into the atmosphere. However, long-term storage in deep rock formations carries risks, such as potential leakage due to crustal movements, which could undermine the effectiveness of CCS. Additionally, capture and storage technologies are expensive. Moreover, direct air capture (DAC) is a technology that removes CO2 from the atmosphere. The technology removes CO2 directly from ambient air using high-powered fans to draw air into a processing facility, where CO2 is separated through a series of chemical reactions before being compressed and stored [12]. Meanwhile, capturing CO2 from the air is the most expensive form of carbon capture due to its low concentration in the atmosphere compared to flue gases from power plants or industrial facilities.

As natural and cost-effective carbon-capturing and permanent storing methods, afforestation and reforestation offer a sustainable alternative to industrial carbon capture methods. Afforestation converts abandoned and degraded agricultural land into forests, while reforestation restores tree cover in deforested areas [13,14]. Statistics show that natural forest regrowth could absorb up to 8.9 billion metric tons of CO2 annually by 2050, offsetting approximately 23% of global emissions [15].

1.2. Research Gap and Objectives

Recent research has increasingly explored sustainable construction materials to mitigate climate change impacts. Meng et al. [16] provided an in-depth analysis of recent advancements in carbon sequestration within concrete materials, focusing on the role of carbonation curing technologies in conventional Portland cement (PC)-based materials. The CO2 absorption capacity of different binder compositions has been investigated [17], including Portland cement, pozzolanic materials, and alternative non-cementitious binders, to assess their potential for carbon sequestration. Also, Sangmesh et al. [18] explored agricultural waste as a sustainable alternative to reduce reliance on cement, indirectly contributing to CO2 reduction. Additionally, Bjånesøy et al. [11] offered valuable insights into biogenic carbon sequestration and storage (CSS) within urban built environments, though their focus was predominantly on biogenic materials, leaving significant gaps regarding the role and efficiency of non-biogenic materials in capturing, storing, and reducing CO2.

Furthermore, studies by Song et al. [6] and Ahmed et al. [19] have identified biochar, derived from biomass waste, as a sustainable additive for reducing carbon emissions in cement-based materials; however, broader applicability and integration strategies remain underexplored. Although Arehart et al. [8] provided a comprehensive review of carbon sequestration in buildings, particularly the concept of “buildings as carbon sinks” and quantification methodologies at varying scales, they did not sufficiently address detailed assessments of specific construction materials and their practical applications in carbon management. Consequently, despite the existing body of literature, substantial gaps persist, particularly concerning integrated studies that concurrently evaluate multiple construction materials and techniques capable of capturing, storing, and reducing CO2. Addressing these gaps through targeted research will be critical for advancing the development and implementation of multifunctional, low-carbon, climate-resilient built environments.

The study aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of methodologies and strategies applied in the built environment (BE) for capturing, storing, and reducing CO2 emissions. By focusing on methodological approaches rather than solely on specific materials, the review facilitates a holistic understanding of carbon management practices within the BE. The specific objectives of this review include:

Providing a state-of-the-art overview of the principles and mechanisms underlying carbon capture, storage, and reduction methodologies applicable to the built environment.

Critically evaluating existing methodologies and strategies employed in construction processes and built infrastructure to capture, store, and reduce CO2 emissions.

Systematically classifying practical implementations of carbon management strategies within various built environment applications.

Assessing the potential and feasibility of integrating novel methodologies, such as direct air capture, into construction processes and existing infrastructure.

Identifying critical knowledge gaps and proposing strategic research directions to guide future advancements and enhance the effectiveness of carbon management strategies in achieving sustainable, low-carbon built environments.

The study is structured as follows: Section 2 offers an overview of carbon classification principles in the BE, addressing carbon capture in Section 2.1, where various mechanisms such as photosynthesis, concrete passive carbonation, and microbial biomineralization are examined. Section 2.2 explores techniques, including carbonation curing, accelerated mineral carbonation, and using construction and demolition waste. Section 2.3 focuses on minimizing CO2 emissions using alternative materials. Section 3 dips into various materials with the potential for direct CO2 capture, although many are not yet widely adopted in construction. Section 4 identifies key research gaps and outlines future directions to promote a carbon-neutral built environment. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the key findings and provides concluding remarks on the role of sustainable materials in achieving a low-carbon built environment.

2. Carbon Capture, Storage, and Reduction Principles in the Built Environment

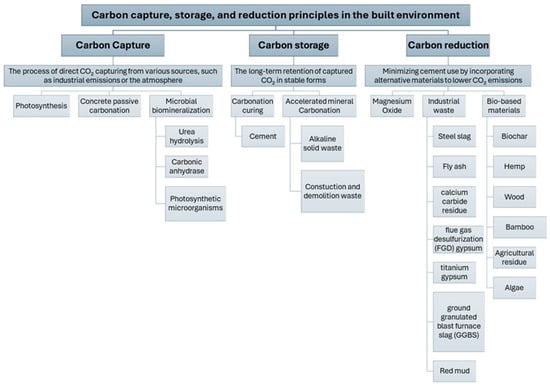

This section outlines the principles, mechanisms, and materials associated with carbon capture, storage, and reduction in the built environment. Figure 2 provides a visual summary of the processes under each strategy, and the following subsections provide a detailed discussion of each one.

Figure 2.

Overview of carbon capture, storage, and reduction pathways in the built environment. The figure illustrates key processes and materials involved in each strategy.

2.1. Carbon Capture

Carbon capture refers to trapping carbon dioxide (CO2) from various sources, such as industrial emissions or the atmosphere, to mitigate its impact on climate change. This process is crucial in reducing greenhouse gas concentrations and can be integrated into construction materials and environmental applications. Carbon capture can occur naturally through biological processes or be engineered using chemical and mineralization techniques. The following subsections delve into key mechanisms: photosynthesis in Section 2.1.1, where plants and bio-based materials absorb CO2; concrete passive carbonation, in Section 2.1.2, which involves CO2 reacting with cementitious materials to form stable carbonates; and microbial biomineralization in Section 2.1.3, where a microbial-induced process that converts CO2 into mineral deposits, enhancing durability and sustainability in construction materials.

2.1.1. Photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is a natural carbon-capturing mechanism related to bio-based construction materials. It allows plants to convert carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere into biomass using sunlight as an energy source. This biological process supports plant growth and effectively sequesters carbon, locking it into its structure for extended periods. Materials derived from biomass, such as wood products, agricultural residues, and biomass waste, exhibit remarkable potential for incorporating photosynthetic carbon sequestration into sustainable construction practices. These bio-based materials serve as carbon sinks, storing CO2 captured during their growth phase. Biochar is a prime example of a material leveraging photosynthesis for carbon capture. As a carbon-rich byproduct of biomass pyrolysis under controlled oxygen conditions, biochar stabilizes atmospheric CO2 absorbed during photosynthesis, storing it long-term [19]. According to the IPCC, producing one ton of biochar offsets between −2.0 and −2.6 tons of CO2, underscoring its significant potential to combat climate change [20]. Hemp-based building materials further illustrate the power of photosynthesis in carbon sequestration. During growth, hemp sequesters substantial amounts of CO2, resulting in a negative carbon footprint when used in construction. A life cycle assessment (LCA) by Rivas-Aybar et al. [21] demonstrated that hemp-based boards achieve a carbon footprint of −2.302 kg CO2 eq/m2, significantly outperforming traditional gypsum plasterboards. Marine macroalgae, such as seaweed, also play a vital role in photosynthetic carbon sequestration, containing an average of 25–30% carbon by dry weight [22]. Their rapid growth in nutrient-rich environments makes seaweed biomass a renewable carbon-fixing resource. Scardifield et al. [23] demonstrated this potential by using residual biomass from Ulva ohnoi, a green seaweed, to develop sustainable bio-masonry products, showcasing the dual role of seaweed in sequestering CO2 during growth and its application as a sustainable construction material. Wheat straw is a biogenic material that has received significant attention. A cubic meter of straw stores 129.25 kgCO2 eq [24]. Furthermore, when used as an insulation material, it has been reported to have close to −60 kgCO2e per 1 square of material at a sufficient thickness to achieve a U value of 0.14 W/m2K. Detailed materials derived from bio-based materials captured CO2 by the photosynthesis mechanism and used in the built environment are illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Materials captured CO2 by photosynthesis mechanism.

2.1.2. Concrete Passive Carbonation

While concrete structures made of cementitious materials are a significant contributor to anthropogenic CO2 emissions, they are a potential carbon sink. Despite its slow nature, passive carbonation or weathering carbonation describes the process of carbon uptake in cementitious materials in which atmospheric carbon dioxide reacts with hydration products to form calcium carbonate. Alkaline compounds in cement, such as calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)2) and calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H), react with atmospheric CO2 over the material’s lifecycle [41]. Various national studies, for example, in Ireland and Sweden, have estimated carbon uptake by concrete structures to range from 75 to 125 kg of CO2 per ton of cement over a 100-year service life, potentially offsetting up to 16% of cement production emissions [42,43]. In China [44], carbon uptake in 2021 was estimated at 426.77 Mt CO2, contributing to national and global land sink estimates. While concrete structures can act as long-term carbon sinks through passive carbonation, global estimates of this effect vary widely. A key uncertainty lies in calculating the total exposed concrete surface area, which significantly influences uptake projections. Therefore, further research is needed to accurately assess the role of passive carbonation at scale [42,43,44,45,46].

Atmospheric CO2 reacts with calcium hydroxide (a by-product of the hydration process) to form calcium carbonate (calcite) (Equation (1)) [47], densifying the material and reducing porosity. However, excessive CO2 exposure can decompose C-S-H (Equation (2)), a critical component of cement’s binding matrix, leading to carbonation shrinkage and increased porosity.

Ca(OH)2 + CO2 → CaCO3 + H2O

C-S-H + CO2 → CaCO3 + SiO2 + H2O

2.1.3. Microbial Biomineralization

Microorganisms capable of performing mineral carbonation have emerged as powerful tools for sustainable applications, particularly in geoengineering and construction materials. In the presence of calcium or magnesium ions, carbon-capturing bacteria can adsorb and transform CO2 into carbonates, facilitating the environmentally friendly process of microbial carbonization. This process, often mediated by metabolic pathways like ureolysis [48], carbonic anhydrase activity [49,50,51], and photosynthetic bacteria such as cyanobacteria [52], has been widely studied for its potential to induce calcium carbonate precipitation (MICP). MICP offers innovative solutions for CO2 sequestration and creates valuable materials for soil improvement [49], durability enhancement in cementitious structures [50], and novel uses within the BE.

Urea Hydrolysis

The urea hydrolysis pathway is one of the most studied microbial metabolic processes for calcium carbonate (CaCO3) precipitation [51]. This pathway is primarily driven by urease, an enzyme produced by ureolytic bacteria such as Sporosarcina pasteurii. Urease catalyzes the breakdown of urea (CO(NH2)2) into ammonia (NH3) and carbamate (NH2COO−) in an aqueous environment. The production of hydroxide ions (OH−) raises the pH, creating conditions favorable for CaCO3 precipitation, while the negatively charged cell surface of bacteria helps attract calcium ions, further promoting mineralization. A series of natural reactions then occurs. Finally, the carbonate ions (CO32−) react with calcium ions (Ca2+) in the environment, leading to the precipitation of calcium carbonate (CaCO3), which can take forms such as calcite or vaterite. However, the high cost of urea and calcium sources presents a significant challenge to the practical application of urease-based calcite precipitation in field settings. Additionally, the release of ammonia (NH3) during the process raises environmental concerns due to its potential impact on pollution.

Carbonic Anhydrase

In contrast, bacteria that produce carbonic anhydrase can efficiently capture CO2, helping to reduce atmospheric CO2 levels. The carbonic anhydrase (CA) activity pathway is an enzymatic process that plays a critical role in CO2 sequestration and calcium carbonate (CaCO3) precipitation. Carbonic anhydrase is a highly efficient metalloenzyme found in various microorganisms, including bacteria like Bacillus subtilis, and it catalyzes the reversible hydration of carbon dioxide (CO2) into bicarbonate ions (HCO3−). This reaction is crucial in environments with calcium or magnesium ions, as it enables the formation of carbonate minerals under alkaline conditions.

Photosynthetic Microorganisms

Photosynthetic microorganisms, such as cyanobacteria and microalgae, can promote carbonate precipitation through their unique metabolic processes [52]. During photosynthesis, CO2 is consumed to produce organic compounds and oxygen, which re-establishes the carbonate equilibrium. This promotes the conversion of bicarbonate into CO2 and hydroxide ions, increasing alkalinity and enabling calcium carbonate precipitation. The coupling of photosynthesis with carbonate precipitation significantly enhances the CO2 fixation efficiency of these microorganisms, making them a promising solution for carbon sequestration and mineralization. Microbial-induced calcium carbonate precipitation (MICP) has been extensively studied and applied across various fields, as highlighted by notable studies [53]. Gilmour et al. [51] developed an innovative approach to carbon capture by genetically engineering Bacillus subtilis to express previously uncharacterized carbonic anhydrase (CA) enzymes from Bacillus megaterium. This engineered bacterium successfully sequestered CO2 and converted it into calcium carbonate (CaCO3), a key material for sustainable construction. The process demonstrated a significant reduction in CO2 levels (from 3800 ppm to 820 ppm) and produced calcite and vaterite minerals, confirmed via X-ray diffraction and scanning electron microscopy. By incorporating the bacterium SAML2018, capable of both ureolysis and CO2 hydration via urease and carbonic anhydrase enzymes, the study demonstrated significant improvements in CO2 capture and material performance [50]. The compressive strength value of carbonation-cured specimens was higher than that of water-cured specimens. This is attributed to promoting the hydration of stable C2S under carbonation conditions and a large amount of CaCO3 in a stable state. The obtained results implied the ability of MICP to repair concrete cracks. Yu et al. [49] focused on microbial carbonization for dust control, using Streptomyces microflavus to transform CO2 into stable calcite that binds sand particles, outperforming Paenibacillus mucilaginosus in terms of efficiency and mechanical strength. Together, these studies showcase the diverse potential of microbial processes in CO2 capture, environmental remediation, and the development of sustainable construction materials. Table 2 provides a summary of CO2 capture by microbial biomineralization.

Table 2.

Different microbial approaches to form CaCO3.

2.2. Carbon Storage

Carbon storage refers to the long-term retention of captured CO2 in various forms to prevent its release into the atmosphere. In the built environment, carbon storage is integrated into construction materials through carbonation curing, where CO2 is absorbed into the concrete, and accelerated mineral carbonation converts CO2 into stable carbonates. The following subsections explore key storage mechanisms, including Section 2.2.1, where CO2 is absorbed during the early setting of concrete to improve strength and store carbon; accelerated mineral carbonation, in Section 2.2.2, where CO2 reacts with alkaline industrial waste to form stable carbonates; and the use of construction and demolition waste (CDW), in Section 2.2.3, which offers a dual benefit of waste valorization and permanent CO2 sequestration through mineral reactions.

2.2.1. Carbonation Curing

Various carbonation procedures have been developed to enhance carbonation efficiency, particularly given the low atmospheric CO2 concentration (~0.041%) [54]. Early-age carbonation treatment has demonstrated a positive impact on the strength development of concrete by densifying its microstructure [55,56]. Carbonation curing, typically conducted shortly after casting, involves exposing early-age concrete to high concentrations of CO2. During this process, calcium hydroxide reacts with dissolved CO2 in the pore solution, precipitating calcium carbonate. Carbonation curing utilizes high-concentration CO2 sources, including pure CO2 and flue gas. While pure CO2 offers a significantly higher concentration (e.g., 99% compared to 20% in flue gas), flue gas is often more economical. This process, generally completed within the first 24 h of concrete mixing, enables CO2 to react with cement phases and hydration products, forming stable minerals such as calcium carbonate (CaCO3) and silica (SiO2), thus contributing to carbon sequestration. Although both weathering carbonation and carbonation curing facilitate carbon sequestration, they are fundamentally different. Weathering carbonation is a passive, long-term process, whereas carbonation curing is an active, short-term approach, typically completed within a day. Furthermore, the reactions in weathering carbonation predominantly involve calcium hydroxide (portlandite), which reacts with atmospheric CO2 to produce calcium carbonate, as described in Equation (1).

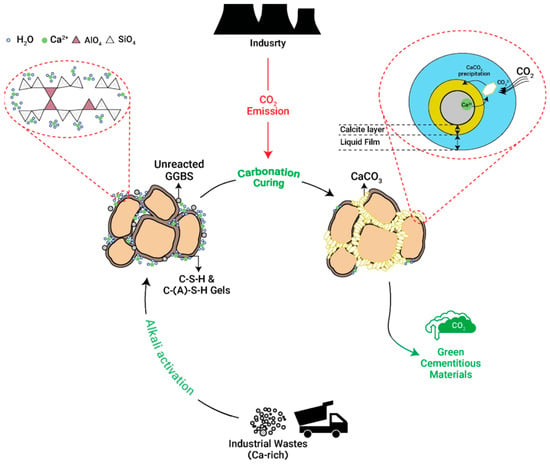

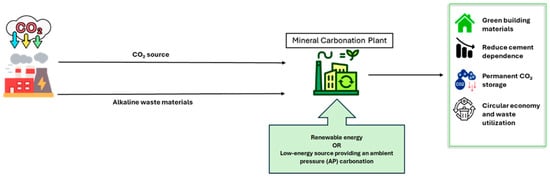

2.2.2. Accelerated Mineral Carbonation

Mineral carbonation is a promising method for CO2 storage that involves the fixation of CO2 through reactions with alkaline and alkaline-earth oxides, such as magnesium oxide (MgO) and calcium oxide (CaO) [57], as shown in Figure 3. These chemical reactions create stable carbonates, including magnesium carbonate (MgCO3) and calcium carbonate (CaCO3). This process mimics and accelerates the natural geological process of rock weathering, providing a means for long-term carbon storage [54]. In addition to naturally occurring oxides and magnesium, iron, and calcium silicates, alkaline solid wastes from industrial processes such as municipal waste incineration ash, coal combustion by-products, cement production residues, and steel slag are suitable feedstocks for mineral carbonation. These materials offer a faster reaction rate and higher carbonate conversion efficiency than natural minerals and require minimal energy input, making them highly practical for CO2 sequestration [58].

Using industrial by-products and construction and demolition waste materials in mineral carbonation provides dual benefits: effective waste management and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Numerous studies have demonstrated the feasibility of carbonating a wide range of industrial wastes, including fly ash [59,60,61,62,63], Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag [64,65,66], steel slag [57,67,68,69,70], calcium carbide residue [71], red mud [72], FGD-gypsum [73], titanium gypsum waste [74], and construction and demolition waste [75,76,77,78,79,80,81], further highlighting the potential of this approach for creating sustainable construction materials while addressing CO2 emissions. Furthermore, Magnesium oxide (MgO) cement binders are gaining attention as sustainable alternatives to traditional Portland cement due to their ability to store CO2 through mineral carbonation [82,83,84,85,86,87,88].

Equations (3) and (4) summarize the general carbonation reaction of Ca and Mg-rich silicates and oxides, respectively.

where X corresponds to either Ca or Mg.

XSiO3 + CO2 → XCO3 + SiO2

This Mineral carbonation process can be categorized into direct carbonation, aqueous carbonation, and carbonation during mixing, each offering distinct advantages based on reaction conditions and material composition.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of the accelerated carbonation process applied to alkali-activated industrial wastes. The process involves the dissolution of CO2 into pore water, forming carbonate ions that react with calcium and magnesium oxides present in the waste materials to precipitate stable carbonates such as calcite [65].

Direct Carbonation

Direct carbonation involves alkaline-rich materials, such as steel slag and fly ash, to concentrated CO2 at elevated pressures and concentration under controlled environments, expediting the conversion of oxides into stable carbonates. Various studies have explored direct carbonation for CO2 sequestration and material enhancement, differing in curing conditions, CO2 exposure settings, and pressure levels. Razeghi et al. [65] applied carbonation to alkali-activated slag-stabilized soil after 7 days of initial curing, exposing it to 100, 200, and 300 kPa CO2 for 1 h in a sealed chamber, finding that excessive pressure reduced strength. In contrast, Kravchenko et al. [68] carbonated steel slag samples without prior extended curing, placing them on a plastic grid in a sealed chamber at 0.15 MPa CO2 for 24 h, with polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) improving CO2 retention. Feng et al. [89] investigated carbonation resistance in geopolymers, sealing five out of six surfaces to ensure that CO2 could only diffuse into the interior of the specimen from the exposed face and exposing the samples to 20% CO2 at 70% humidity and 20 °C, with exposure durations ranging from 12 h to 28 days. Lastly, Xian et al. [57] studied early-age carbonation curing in cement-free concrete made from steel slag, applying carbonation immediately after casting in either a near-ambient pressure (1.4 kPa) inflatable enclosure or a high-pressure (500 kPa) sealed chamber, both for 24 h before transferring the samples to a moisture room for further hydration curing.

Aqueous Carbonation

Aqueous carbonation process where a constant flow of CO2 is bubbled into an aqueous solution containing alkaline, leading to carbonate precipitates. Compared to direct carbonation, aqueous carbonation enhances CO2 uptake by improving ion mobility in liquid media, eliminating diffusion limitations, and significantly accelerating the reaction. Martos et al. [83] developed a magnesium carbonate trihydrate (MgCO3·3H2O) material by bubbling CO2 (10%) into a NaOH solution, which then reacted with Mg-rich brines, achieving an 85–90% Mg precipitation yield at room temperature in ~3 h. In contrast, Lin et al. [74] applied an indirect aqueous carbonation method to titanium gypsum, first extracting Ca2+ using ammonium acetate before bubbling CO2 at 100 mL/min, resulting in 97.28% vaterite CaCO3 conversion within 20 min. Han et al. [64] dissolved CO2 in a 3M NaOH solution, producing a CO2-activated alkali solution that instantly carbonated alkali-activated slag (AAS). Other alkaline materials, such as FGD gypsum [73] and CFBC ash [90], have high Ca2+ availability, making them practical for CO2 sequestration through aqueous carbonation.

Carbonation During Mixing

Luo et al. [62] explored CO2 injection during the mixing stage of fly ash (FA) blended cement pastes to enhance early hydration and mechanical properties. High-purity CO2 (99%) was injected into fresh cement pastes during the final 60 s of mixing at varying doses (0.3%, 0.6%, 0.9%, and 1.2% by cement weight). The study found that lower CO2 doses (0.3–0.6%) promoted early-age strength (3.3–8.2% increase at 1–3 days) by forming CaCO3, which acted as a nucleation site for hydration.

2.2.3. Construction and Demolition Waste

As discussed in Section 2.2.2, construction and demolition waste (CDW) is highly suitable for mineral carbonation due to its abundant alkaline materials, such as calcium, which react with CO2 to form stable carbonates, enabling waste valorization and carbon sequestration. In 2020, global solid waste generation reached 2.24 billion tons, with CDW comprising at least 30% of this total [91]. Recent research highlights its potential as a sustainable resource in construction, particularly for cement replacement and CO2 storage [76,77].

Kravchenko et al. [76] explored waste concrete powder (WCP) as a carbon storage material and cement substitute, evaluating different scenarios through life cycle assessment (LCA). The findings showed that 8 h carbonation at 0.15 MPa CO2 achieved an optimal uptake of 42.7 kg CO2-e per tonne, resulting in a carbon-negative global warming potential (GWP) of −4.22 kg CO2-e. While carbonated WCP had limited CO2 uptake as a cement replacement, uncarbonated WCP reduced the carbon footprint by 16% when replacing 20% of cement in concrete mixes. Similarly, the accelerated carbonation process developed a zero-cement hollow block with 75% recycled concrete fines [77]. The carbonation of the hollow blocks resulted in a CO2 uptake of approximately 100 kg CO2/ton of product, with an average compressive strength of 15.4 MPa at the lab scale and 6.4 ± 0.2 MPa at pilot production, meeting the minimum compressive strength of 5 MPa needed for hollow blocks that can be used as non-bearing separation walls.

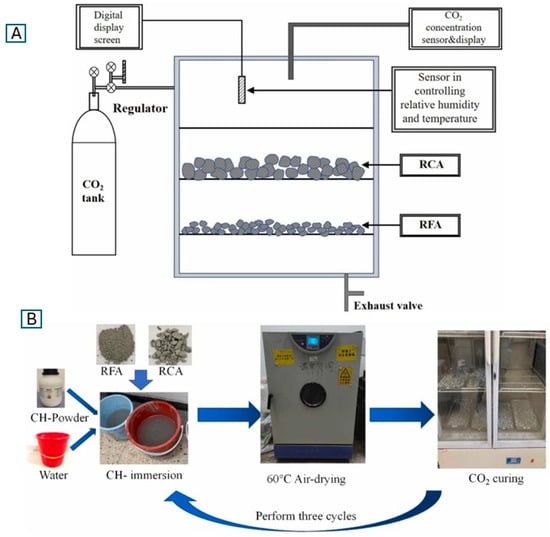

CDW can also be used to produce carbonated recycled concrete aggregates (RCA) [75,77,78,79,80], offering permanent CO2 storage while reducing reliance on natural aggregates, which are increasingly scarce. The research [77] demonstrated that carbonating RCA with size range from 4 to 16 mm at atmospheric pressure, with CO2 concentrations as low as 10% and temperatures of 60 °C, significantly reduced water absorption and increased aggregate hardness, enabling up to 50% replacement of natural aggregates without compromising concrete strength. Recycled brick powder (RBP) was also investigated as a partial sand replacement, where carbonation improved lime reactivity, accelerated hydration by 4–5 h, and enhanced compressive strength by 19–21% compared to non-carbonated RBP [75]. The CO2 uptake of pre-carbonated RBP (16–17%) was significantly higher than the 10.7% observed in control samples. To improve recycled aggregate concrete (RAC) durability, particularly under freeze–thaw conditions, Liang et al. [78] compared three CO2 curing methods: standard curing, pre-saturated calcium hydroxide Ca(OH)2 immersion, and whole-specimen CO2 curing in Figure 4. All methods enhanced peak stress and elastic modulus (12.3–13.7% and 19.2–31.5%, respectively), with Ca(OH)2 immersion achieving the best performance. Fernández et al. [80] further demonstrated that carbonated water as kneading water in cement-based materials (CBMs) improved early-age strength retention and long-term durability, particularly when combined with recycled masonry aggregates (RMA).

Figure 4.

Illustration of the CO2 curing procedures applied to recycled aggregates in this study [78]. (A) Schematic diagram of the standard CO2 curing chamber setup, where recycled coarse aggregates (RCA) and recycled fine aggregates (RFA) are exposed to controlled CO2 concentration, temperature, and relative humidity using an airtight system equipped with sensors and a digital display. (B) Process flow of the Ca(OH)2 immersion-assisted CO2 curing method (HH group): recycled aggregates are first soaked in a saturated calcium hydroxide solution, followed by air-drying at 60 °C and then CO2 curing. This cycle is repeated three times to enhance the carbonation potential.

Beyond structural applications, CDW can enhance urban ecosystems. Fan et al. [92] evaluated waste building material substrates (WBMS) in green roofs over a year-long study, showing superior carbon sequestration (12.8 kg C/m2/year), 1.1 times higher than local natural soil (LNS). WBMS recycled CDW and improved urban ecosystem services, highlighting its dual role in waste management and climate change mitigation.

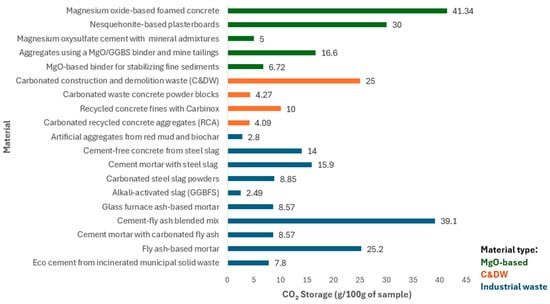

To provide a comparative perspective on CO2 storage performance, Figure 5 shows the CO2 uptake capacities of various construction materials discussed throughout Section 2.2. The materials are grouped into three categories based on their origin: MgO-based materials, construction and demolition waste (C&DW), and industrial waste-derived materials. The reported values reflect results obtained under varying carbonation methods and conditions, including direct carbonation, aqueous carbonation, and carbonation during mixing. These differences in process, pressure, duration, and CO2 concentration contribute to the observed variation in uptake performance across materials.

Figure 5.

CO2 storage capacity (g per 100 g of sample) of various materials used in the BE. Materials are grouped by type: MgO-based materials (green), construction and demolition waste (C&DW) (orange), and industrial waste-derived materials (blue). References for each material corresponding to the order of materials shown in the figure, from top to bottom, within each category: (MgO-based: refs. [82,83,84,85,86]), (C&DW: refs. [60,75,76,77]), (Industrial waste: refs. [57,59,60,61,63,64,67,69,72,93]).

2.3. Carbon Reduction

Carbon reduction in construction primarily focuses on minimizing the use of traditional cement products, which are major contributors to CO2 emissions. Alternative materials include Magnesium oxide binders Section 2.3.1, industrial waste materials Section 2.3.2, and bio-based materials Section 2.3.3, which promote recycling and sustainable resource use. The following subsections explore these approaches in detail, highlighting their potential to drive sustainable construction practices.

2.3.1. Magnesium Oxide

Another alternative approach towards sustainable construction materials is through MgO incorporation. The production of MgO requires lower temperatures than the conversion of CaCO3 into ordinary Portland cement (OPC), resulting in significant energy savings and positioning MgO-based cement as a promising option for sustainable cement production [94]. Additionally, MgO’s capacity to absorb CO2 from the atmosphere and form various carbonates and hydroxy carbonates aligns with the concept of “carbon-neutral” cement, capable of offsetting nearly the same amount of CO2 emitted during its manufacturing process. Magnesia (MgO) can be produced not only through the calcination of magnesia-based minerals (e.g., magnesite, dolomite, or serpentine) but also via the alkaline precipitation of brucite (Mg(OH)2) from seawater or magnesium-rich brine [83]. Additionally, MgO obtained from seawater/brine has been proven to outperform MgO obtained from the magnesite calcination with higher purities and reactivities because of the larger specific area (SSA) [95].

Li et al. [84] investigated oxysulfate (MOS) cement, which integrates fly ash (FA) and ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBFS) to enhance sustainability. When subjected to accelerated carbonation for 24 h, the material achieved 5% CO2 uptake, improving early-age compressive strength due to the formation of hydrated magnesium carbonates (HMCs). The study showed that the CO2 curing treatment improved compressive and flexural strength. However, excessive FA and GGBFS additions were found to reduce compressive strength, likely due to the diminished formation of the 5·1·7 phase (Mg(OH)2·MgSO4·7H2O). This highlights the need for an optimal balance in the composition of MgO-based cementitious materials. Similarly, Gonçalves et al. [87] explored MgO as a partial OPC replacement in cementitious mortars, demonstrating that MgO promotes the formation of magnesium hydroxide Mg(OH)2, which reduces shrinkage strain by up to 80% due to its expansive properties.

Martos et al. [83] developed a carbon capture and utilization (CCU) process that effectively captures CO2 from power plant flue gas (~10% CO2 concentration) and converts it into nesquehonite (MgCO3·3H2O)-based materials. This sustainable alternative to gypsum plasterboard has a CO2 capture efficiency of over 99%, demonstrating its potential for large-scale application. This material, containing over 30% CO2 by weight, can be hardened into plasterboard-like products using thermal activation or forced conversion, further enhancing its eco-efficiency. Additionally, precipitated calcium carbonate (PCC) by-products from the process can be used as aggregates or fillers, improving material sustainability.

A novel MgO-based material, Magnesium Oxide Carbon Sequestration Foamed Concrete (MCFC), was introduced by [82] as an innovative approach to reducing carbon emissions and enhancing CO2 capture. Unlike conventional concrete, foamed concrete contains air foam, which improves thermal insulation, lightweight properties, and fluidity. In MCFC, reactive MgO replaces OPC, and CO2 foam replaces conventional air foam, resulting in a material with superior carbon sequestration capacity. A Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) revealed that MCFC reduces carbon emissions by 50% compared to traditional foamed concrete, with a Global Warming Potential (GWP) of 246.18 kg CO2 eq/m3, significantly lower than 505.6 kg CO2 eq/m3 for OPC-based foamed concrete. Field applications in a road widening project in Suzhou, China, demonstrated that replacing PC-based foamed concrete with MCFC reduced CO2 emissions from 1000 to 470 tons, reinforcing its feasibility for large-scale infrastructure applications, particularly in non-structural components such as road embankments and lightweight concrete elements.

Beyond structural materials, MgO-based binders have been developed for environmental remediation and soil stabilization. Hwang et al. [85] designed a binder of 50% MgO, 5% Lime, 18% FA, and 27% BFS, which achieved a compressive strength of 11.9 MPa, comparable to OPC (12.2 MPa). This binder was used to stabilize dredged sediments, where it not only enhanced compressive strength to 4.78 MPa after 365 days but also sequestered 67.2 kg CO2 per ton of sediment over a year. These results highlight MgO’s effectiveness in carbon storage and environmental stabilization applications. Kim et al. [86] investigated MgO-GGBS binders for stabilizing mine tailings and heavy metals, a crucial area given the high carbon footprint of traditional Portland cement (PC) in mining applications. A binder composition of 50% MgO and 50% GGBS was found to be the most effective, with granules cured under 20% CO2 achieving a compressive strength of 4.71 MPa after 28 days and a CO2 sequestration capacity of 0.159 kg CO2/kg binder, outperforming other mixtures.

2.3.2. Industrial Waste

Industrial by-products play a critical role in both carbon storage and reduction, providing sustainable alternatives to conventional cementitious materials while significantly lowering CO2 emissions. As discussed in Section 2.2.2, many industrial wastes such as steel slag, calcium carbide residue (CCR), ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBS), and fly ash are rich in calcium oxide (CaO) and magnesium oxide (MgO). These oxides facilitate mineral carbonation to form stable carbonates, ensuring permanent carbon sequestration within construction materials.

Beyond their role in carbon storage, industrial by-products contribute to carbon reduction by replacing traditional clinker-based cement [96]. They are widely utilized as Supplementary Cementitious Materials (SCMs), Alkali-Activated Materials (AAMs), geopolymers, and aggregates, reducing reliance on energy-intensive cement production and enhancing the environmental performance of concrete. The following subsections will examine the specific applications of industrial by-products in carbon reduction.

Li et al. [59] examined municipal solid waste incineration (MSWI) fly ash (50%) as SCM, demonstrating that CO2 curing at 0.5 MPa for 2 h increased compressive strength to 12.3 MPa, 3.43 times higher than untreated mortars. CO2 capturing has also improved, rising from 17.2% to 25.2% at 2.5 MPa. Similarly, carbonation-treated circulating fluidized bed combustion (CFBC) ash enabled its use as a cement substitute, with 20% replacement maintaining strength and 25% replacement producing suitable foam concrete with optimal thermal conductivity and density [90]. Huseien et al. [97] explored high-volume fly ash (60%) combined with bottle glass waste nanoparticles (BGWNPs, 2–10%), resulting in reductions of 61.9% in CO2 emissions, 54.3% in energy consumption, and 50.6% in binder cost compared to OPC. High-calcium fly ash (HFA) has also been studied for carbonation curing, with Su et al. [61] achieving a CO2 uptake of 8.24%, alongside improved resistance to freeze–thaw cycles and sulfate attack. Similarly, Li et al. [67] found that reducing steel slag particle size from 112.6 μm to 22.4 μm doubled CO2 uptake (from 37.9 kg CO2/t to 88.5 kg CO2/t), as higher surface area facilitated ion leaching and carbonation efficiency.

Beyond SCMs, Alkali-Activated Materials (AAMs) or geopolymers provide low-carbon cement alternatives using aluminosilicate precursors activated with alkaline solutions. Alkali-activated slag binders using GGBFS have been shown to stabilize soil, with 20% binder content improving mechanical properties under accelerated curing [65]. Coffetti et al. [98] demonstrated that AAMs derived from GGBFS achieved compressive strength targets while reducing Global Warming Potential (GWP) by up to 75% in applications like structural plaster and pervious concrete. Similarly, reference [66] developed an eco-friendly cement binder using fly ash, blast furnace slag, rice husk ash, and aluminum foil, leading to a 55% CO2 emission reduction and 35% cost savings compared to OPC. In addition to fly ash and slag, other industrial residues such as waste glass and red mud are gaining traction as promising precursors for geopolymer-based construction materials. Red-mud-based geopolymers (RM-GM) convert industrial waste into low-carbon binders, achieving up to ~80 MPa compressive strength and 60–64% lower CO2 emissions than cement [99]. They also immobilize heavy metals (>80%) and are applicable in construction, soil stabilization, and environmental remediation. Additionally, waste glass is emerging as a viable alternative precursor for low-carbon geopolymer systems. Xiao et al. [100] propose a Portland cement-free, high-volume waste glass geopolymer composite, in which both glass powder (GP) and glass cullet aggregates are used to achieve up to ∼83 wt% waste glass in the total solid content.

Other industrial by-products, such as red mud from bauxite refining, offer additional applications, including artificial aggregates. Liu et al. [72] investigated artificial lightweight cold-bonded aggregates (ALCBAs) made from red mud and biochar, achieving CO2 uptake of 26.0–29.1 kg/ton under natural carbonation. The process involved CO2 reacting with alkaline minerals (calcium silicate, portlandite) to form stable carbonates, while biochar enhanced CO2 storage due to its porous structure. In infrastructure applications, red mud (RM) based cementitious materials were developed for semi-flexible pavement (SFP) as an eco-friendly alternative to traditional grouting materials [101]. Two types were evaluated: red mud-slag powder composite (RSCM) with 50% RM and 50% slag powder, and red mud-cement composite (RCCM) with 10% RM and 90% cement. RCCM exhibited superior properties that met the standards for asphalt pavement in heavy traffic. A Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) indicated significant reductions in energy consumption and Global Warming Potential (GWP) compared to conventional materials.

Several key factors governing the carbonation behavior of industrial wastes such as CO2 pressure, reaction duration, temperature, particle size, and w/b ratio. With respect to CO2 pressure, most studies show that moderate pressures enhance early carbonation by increasing CO2 dissolution, as seen in Li et al. [59] and Razeghi et al. [65]; however, excessively high pressures often reduce efficiency by causing rapid CaCO3 precipitation that blocks pores and limits further reaction, a trend also observed in Xian et al. [70] where ambient-pressure carbonation performed as well as high-pressure curing. Regarding temperature, moderate heating promotes ion dissolution and accelerates carbonation; however, temperatures above ~30–40 °C decrease CO2 solubility and weaken later-stage reactions [59]. Particle size plays a central role in governing the reactivity and carbonation efficiency of industrial wastes used as binder components. Finer particles offer a greater specific surface area, which enhances the dissolution of reactive Ca- and Mg-bearing phases and accelerates the formation of carbonates. However, excessively fine fractions can slow CO2 transport by reducing pore connectivity. For example, Li et al. [67] found that aqueous-carbonated steel slag with particle sizes ranging from 22.4 to 112.6 μm exhibits CO2 sequestration of 88.5–37.9 kg CO2/t, with finer particles showing ~25% higher Ca2+ release. Similarly, in converter-slag mortars cured under ambient CO2, optimal performance occurs at intermediate sizes (21.75–24.13 μm), which maximize strength (≈31 MPa) and CO2 uptake (15.9%) [69]. Moisture availability, reflected through water-to-binder ratio, curing humidity, or aqueous conditions, also follows a consistent trend as sufficient pore water is essential for CO2 hydration and ion transport, yet excessive water blocks gas pathways, while insufficient water limits dissolution [65,89].

A comprehensive summary of industrial wastes in carbon reduction, including their application, carbonation conditions, and mechanical performance, is presented in Table 3.

2.3.3. Bio-Based Materials

Bio-based materials contribute to carbon reduction by capturing and storing atmospheric CO2 through photosynthesis while serving as low-carbon alternatives to conventional construction materials. This section explores the role of biochar, hemp, wood, bamboo, agricultural residues, and algae in carbon reduction and long-term CO2 storage, highlighting their potential in sustainable built environments.

Biochar

Biochar, which is produced through the pyrolysis of biomass such as crop residues, livestock manure, and sewage sludge, is a carbon-negative material that offers two main benefits. First, it sequesters carbon that is captured during photosynthesis. Second, it can be utilized as a construction material in the BE. Additionally, biochar is an effective carbon dioxide adsorbent due to its high porosity. Biochar has different applications, a, including the application in cementitious mortars and concrete [25,36], fillers [19,30], aggregates [20,34,72], and wastewater treatment absorbents [74].

Table 3.

Comprehensive summary of industrial wastes in carbon reduction.

Table 3.

Comprehensive summary of industrial wastes in carbon reduction.

| Material Mix | Waste Source | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Carbonation Condition | CO2 Uptake/Reduction | Application | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| >18 |

|

|

| [71] |

|

|

|

|

| [68] | |

|

|

| Soil stabilization | [65] | ||

|

| 6.1 ± 0.6 |

| Gypsum Panels | [73] | |

|

|

|

| Low carbon Semi-flexible pavement (SFP) | [101] | |

|

| At FA/GGBS ratio 40/60, 6% alkali content, W/B ratio 0.36, and 2% fiber:

|

| Engineering geopolymer composites (EGC) | [89] | |

|

| 1.37 to 1.95 at 28 days |

|

| Artificial lightweight cold-bonded aggregates (ALCBAs) | [72] |

|

|

|

| Alkali-activated slag (AAS) as a Sustainable binder for Pervious Concrete and Structural Plaster | [98] | |

|

|

|

|

| Sustainable alkali-activated slag mortar | [64] |

Eight mortar mixtures:

|

| 94 at 28 days |

| Steel slags as binder compounds and aggregates in alkali-activated systems | [102] | |

|

|

|

|

| SCM | [59] |

|

|

|

|

| [74] | |

|

|

|

|

| Steel slag concrete slabs and pipes | [57] |

|

|

|

| Sustainable concrete repair materials | [97] | |

|

|

|

| Concrete SCM and cement replacement in foam concrete | [90] | |

|

|

|

|

| SCM in concrete | [67] |

|

|

|

| SCM | [60] | |

|

|

|

| SCM in mortar suitable for Freeze–Thaw and sulfate attack | [61] | |

|

|

|

|

| Green Non-Cementitious Binder | [66] |

|

| Up to 31.21 MPa | Ambient CO2 curing at:

|

| SCM in mortars | [69] |

|

|

| SCM in cement paste | [62] | ||

|

|

| Aqueous carbonation process:

|

| SCMs in cement mortar | [63] |

|

|

|

|

| Non-Cementitious Binder | [70] |

|

| 33 MPa at 28 days |

|

| Non-Cementitious concrete blocks | [93] |

As a soil amendment, biochar improves nutrient retention, water absorption, and microbial activity [103]. A global meta-analysis showed that biochar alone reduced global warming potential by 27.1%, while its combination with chemical fertilizers reduced net greenhouse gas emissions by 14.3% [104]. Study shows the impacts of biochar on soil evaporation and shrinkage. Biochar from wheat, corn, and rice straw increased soil water content by up to 132.3% and reduced cracking by up to 16.57% compared to untreated soil [105]. These improvements support long-term plant growth and enhance carbon dioxide uptake through sustained photosynthesis.

In the study by Zou et al. [20], a novel core–shell aggregate (CSA) was developed using biochar as the lightweight core, and a cementitious shell was formed through cold bonding. The optimized mix, MG80, replaced 80% of the cement with ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBS), significantly lowering carbon emissions. In another study, artificial lightweight cold-bonded aggregates (ALCBAs) were developed using a high volume of red mud (90%) combined with varying dosages of biochar (0%, 5%, 10%, 15%) [72]. The aggregates demonstrated promising carbon sequestration potential, with CO2 uptake ranging from 26.0 to 29.1 kg per ton under accelerated carbonation conditions following 28 days of sealed curing.

In natural environments, the carbonation of cement is typically slow due to low atmospheric CO2 concentrations. However, biochar enhances carbonation efficiency in cementitious materials by promoting the production of hydration products and increasing carbon dioxide and water diffusion [38]. The carbonation process, primarily influenced by the cement matrix’s total surface area of pores, benefits from biochar’s abundant micropores and high specific surface area [37]. These properties improve biochar-cement composites’ water adsorption and retention. Additionally, biochar accelerates carbonation reactions by providing more reaction sites for CO2 and calcium hydroxide (CH) interaction, leading to increased CO2 absorption. Agarwal et al. [25] found that 5% biochar replacement in cementitious pastes achieved 11.3% CO2 uptake under accelerated carbonation curing (ACC) while increasing compressive strength by 37% and enhancing thermal insulation. Similarly, Ahmed et al. [19] reported that biochar derived from rice husk-coal blends absorbed 70% more CO2 than control samples, emphasizing its role in carbonation enhancement. In lightweight concrete, biochar contributes to carbon sequestration and environmental remediation. Biochar derived from peanut shells sequestered 541–980 kg CO2-e per ton while improving water resistance and heavy metal immobilization [36]. Additionally, nano-biochar from apricot kernel shells refined pore structures, increasing flexural fracture energy by 98% at 0.04% dosage, demonstrating its scalability for high-performance applications [30].

Beyond cement, biochar-plastic composites (PB composites) also exhibit high CO2 sequestration capacity. A study found that a 50:50 biochar-to-PET ratio sequestered 550 g CO2-e/kg of composite, while cement-based tiles emitted 152.96 g CO2/kg [28]. Similarly, biochar-magnesium oxysulfate cement (MOSC) particleboards achieved CO2 sequestration of 137 kg/ton, although mechanical strength remained challenging due to biochar’s high porosity [34].

Despite its advantages, higher biochar dosages (15–20%) can reduce material strength due to particle agglomeration and increased porosity [38]. In another study [37], biochar from corn straw (1–5%) improved compressive strength, refined pore structure, and increased internal CO2 uptake, reaching 5.05–6.19% CO2 absorption within 40 mm of the surface.

Hemp

Hemp-based materials are key in reducing carbon, offering high CO2 sequestration potential and sustainable construction applications. Industrial hemp absorbs 0.445 tons of CO2 per ton of dry stems during cultivation [106], which is permanently stored in lime-hemp concrete (LHC), hempcrete blocks, and hemp fiber composites, resulting in a negative carbon footprint.

Hemp fibers are valued for their hygrothermal and acoustic insulation properties, making them suitable for biodegradable insulation mats, fiber-reinforced concrete, cement paste, and mortars [107].

Hempcrete, a composite of hemp hurds, lime, and water, is recognized for its thermal insulation and coating applications. Rivas-Aybar et al. [21] found that hemp-based boards achieve a negative carbon footprint of −2.302 kg CO2 eq/m2, outperforming gypsum plasterboards, which release 10.59 kg CO2 eq/m2. Similarly, hemp-lime concrete walls exhibited emissions ranging from +10.165 kg CO2 eq/m2 in pessimistic scenarios to −9.696 kg CO2 eq/m2 under optimal conditions, with carbon sequestration in hemp shives and binder carbonation as critical factors [31]. Isopescu et al. [106] demonstrated that hempcrete masonry blocks can achieve a negative carbon footprint of −20.3168 kg CO2 eq, due to CO2 uptake during plant growth and carbonation over time, making them ideal for thermal insulation layers. Heidari et al. [40] further confirmed that untreated hempcrete sequesters −15.27 to −8.92 kg CO2-eq/m2, while sol–gel coated hempcrete exhibited a higher footprint (22.51 to 28.77 kg CO2-eq/m2). However, this remains significantly lower than traditional cavity walls, which have a footprint of 122.71 kg CO2-eq/m2.

Hempstone, a composite made from hemp stalks, artificial stone scraps, and resin, further demonstrates hemp’s versatility. Studies show that Hempstone reduces environmental impact by 60% compared to artificial stones, with a carbon sequestration rate of 1.67 kg CO2 eq per kg [108].

Wood

Wood and its byproducts play a significant role in carbon reduction, serving as low-carbon construction materials that store CO2 while replacing energy-intensive concrete and steel.

Gao et al. [109] developed mineralized nano-wood, integrating in situ CO2 capture with CaCO3 growth in delignified wood. The production methods include the fabrication of delignified wood by removing hemicellulose and lignin using an aqueous solution containing sodium hydroxide (2.5 M) and sodium sulfite (0.4 M). Then, the delignified wood (DW) was immersed in Ca(OH)2 solution for 4 h at room temperature and continuously passed through CO2 for 4 h to grow and accumulate micro-nano solid particles of CaCO3. The process achieved a high mineralization rate (39%), improved compressive strength (45.4 MPa), and thermal insulation (0.13 W/m·K), enhancing fire resistance and durability. This innovation highlights wood’s potential as a multifunctional, carbon-sequestering material.

Lignin, a complex aromatic biopolymer, provides structural integrity and rigidity to plants by binding cellulose and hemicellulose fibers [110]. As the second most abundant biopolymer on Earth after cellulose, lignin constitutes approximately 30% of wood by weight and contributes to its stiffness, rigidity, and natural antimicrobial properties [111].

Miao et al. [26] developed LignoBlock, a lignin-based biopolymer soil composite (BSC) for non-load-bearing applications such as partition walls and facades. This material achieved a net-negative carbon footprint (−0.14 to −0.23 kg CO2/kg), significantly outperforming lightweight concretes (0.17–0.34 kg CO2/kg) and OPC (0.21 kg CO2/kg).

Integrating wood waste into cementitious materials offers additional carbon reduction benefits. Kuoribo et al. [112] combined wood powder (WP) and glass powder (GP) in cement panels, achieving 18% cost savings, 3.3% CO2 reduction, and 70% annual energy savings compared to conventional panels. Ohenoja et al. [39] introduced a carbon capture and utilization (CCU) method using peat-wood fly ash, leveraging self-hardening properties to produce fly ash tiles while sequestering up to 150 kg CO2 per ton of ash.

Sustainably managed harvested wood products (HWPs) act as long-term carbon sinks while replacing high-emission materials. Chen et al. [113] demonstrated that structural panels and lumber significantly reduce GHG emissions, with 112 Mt CO2eq reductions over 100 years for panels and 93 Mt CO2eq for lumber. Non-structural panels required 39 years to achieve sequestration parity, while pulp and paper products contributed to emissions due to short lifespans and landfill decomposition.

Bamboo

Bamboo significantly contributes to carbon reduction thanks to its rapid growth, high carbon sequestration capacity, and increasing use as an alternative in sustainable construction materials. Species such as Moso bamboo can sequester up to 7.19 tons of CO2 per hectare annually [114], storing more carbon per unit than traditional timber.

With a long history as a construction material, modern advancements in industrial techniques have refined bamboo into engineered products like Glued Laminated Bamboo (GluBam), laminated bamboo lumber (LBL), and parallel strand bamboo (PSB) [115]. Among these, GluBam stands out for its mechanical properties and low carbon footprint, driving its adoption in structural applications and civil engineering projects. Liu et al. [114] demonstrated that engineered bamboo (GluBam) used in rural residential buildings reduces life cycle carbon emissions by 30.4% compared to reinforced concrete (RC) structures with superior thermal insulation properties. Similarly, Zhang et al. [33] conducted a comprehensive life cycle assessment (LCA) of a steel-glued Laminated Bamboo (GluBam) hybrid truss to evaluate its environmental and economic performance compared to an all-steel truss. The results revealed that the hybrid truss reduced carbon emissions to (4572.5 kgCO2eq) and energy consumption by (71.15 GJ) compared to steel. However, these benefits could be further optimized by including end-of-life energy recovery from bamboo combustion in life cycle assessments. A study [115] compared reinforced concrete (RC) and laminated bamboo lumber (LBL) in six-story residential buildings across five cities in China’s cold and severe cold regions demonstrated that substituting RC with bamboo reduces energy consumption by 3–5% and CO2 emissions by 7–20%.

Agricultural Residues

Using agricultural residues in the built environment presents an innovative solution for reducing carbon emissions while effectively utilizing waste.

Straw, the stem of cereal crops such as wheat and rice, has been used in construction for thousands of years. Straw has been used as a building material since the first settlements of ancient Egypt were constructed [116]. Various construction methods use straw as the structure and primary building enclosure material. Li et al. [35] demonstrated the potential of straw bale houses as a scalable low-carbon construction solution, particularly in rural areas. Among the structural forms analyzed, the wood frame straw bale house exhibited the lowest net embodied carbon emissions (ECE) of 19.09 kgCO2e/m2, achieving near carbon neutrality due to straw bales and wood’s high carbon storage potential. In contrast, masonry-concrete straw bale houses showed significantly higher ECE due to the reliance on high-carbon materials like cement and concrete. Di Luigi et al. [29] explored the development of sustainable insulation materials using wheat straw in advanced applications. By employing innovative additive manufacturing techniques, they transformed wheat straw into cellulose fibrils (CF) and combined them with silica aerogels to create high-performance insulation panels. These materials exhibited excellent thermal conductivity (0.036 W/m·K), enhanced structural integrity, and superior moisture resistance through in situ hydrophobic treatments.

Sugarcane bagasse ash (SCBA), a by-product of the sugar industry, has gained attention as a potential alternative to sand in crack repair mortar for rigid pavements [32]. The authors in their study showed that SCBA-based mortars improved compressive strength and reduced environmental impacts, with carbon footprint reductions of up to 24%. Including zeolite and recycled polypropylene fibers further enhanced carbon capture and reduced emissions by 50%.

Sisal fiber, one of the most utilized natural fibers, is easy to cultivate and highly accessible. With a global production of approximately 4.5 million tons annually, sisal fibers play a significant role in construction, where they are widely used as reinforcement in houses [117]. Hu et al. [118] explored innovative low carbon Engineered Cementitious Composites (ECC) incorporating sisal fibers and waste polyethylene fibers derived from discarded fishing nets. Using sisal fibers improved CO2 diffusion and uptake during carbonation curing, increasing compressive strength and tensile performance while reducing CO2 emissions by 50% compared to traditional ECCs.

Algae

Algae are recognized as highly effective in capturing atmospheric CO2. After marine macroalgae (seaweed) is processed to produce high-value products, the leftover biomass can be repurposed for construction materials. Collaboration between designers and scientists has developed innovative marine macroalgae-based biomasonary products using a biorefinery approach [23]. The study optimized the material composition across four phases. Seaweed Ulva powder and carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) emerged as the most effective binder, while crushed oyster shells were used as aggregates to improve stability and reduce shrinkage. A total of 95 bricks were used to construct a 2.6 m high column with a 900 mm diameter, showcased at an exhibition in Australia (Figure 6F). The research highlights the need for future work to compare the production embodied energy of seaweed bricks against commercially available clay bricks to assess their greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction potential. Additionally, algae-derived bio-oils have shown promise in enhancing asphalt pavement durability within the BioPave system [27]. Produced via hydrothermal liquefaction of algal biomass, these bio-oils improve thermal stability, UV resistance, and adhesive properties at optimal concentrations. For instance, bio-oils like Algae-1 (lake-harvested algal biomass) demonstrated high thermal stability, making them more suitable for applications in environments with high-temperature fluctuations. These findings emphasize algae’s versatility in decarbonizing the built environment sector, from biomasonry to infrastructure applications.

Figure 6.

Developing and demonstrating seaweed-based biomasonry using macroalgae (Ulva) and waste oyster shell aggregate. (A) Cleaning, sorting, and sun-drying of oyster shells collected from oyster farms for use as a bio-aggregate. (B) Partially dried Ulva based cube prototype showing material shrinkage and layered composite texture. (C–E) Modular brick prototypes shaped in varying geometries: (C) curved bricks with hollow cores; (D) interlocking ring structure using zigzag-edge bricks; and (E) vertically fluted angular brick units for dry-stacking applications. (F) Full-scale demonstrator column (~2.6 m tall) constructed without mortar using 95 pressed bricks, exhibited at the Art Gallery of South Australia to showcase the architectural potential of seaweed biomaterials [23].

3. Direct CO2 Capturing Materials for the Built Environment

The built environment holds significant potential to shift from a passive to an active role in carbon mitigation. This section explores emerging materials and technologies capable of direct CO2 capture, suggesting their integration into construction materials. Although not yet widely applied, these innovations offer promising pathways for embedding carbon-capturing functions within the built environment.

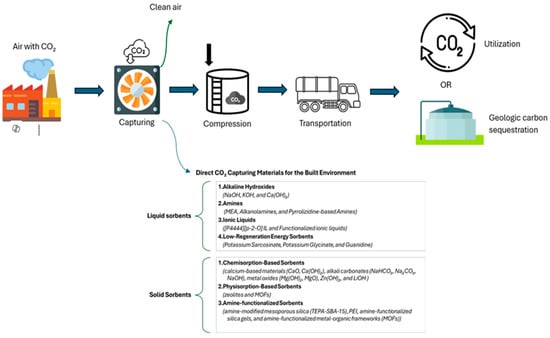

Direct Air Capture (DAC) is an advanced technology designed to remove CO2 directly from the atmosphere, offering a scalable solution for climate change mitigation. Unlike conventional carbon capture methods focusing on industrial emissions, DAC can be deployed anywhere, making it highly adaptable for integration into the built environment. At the core of DAC technology are sorbent materials, specialized substances that selectively capture CO2 from the air. These materials capture CO2 from the air and release it during regeneration for reuse, storage, or industrial applications. Since CO2 is an acidic gas, sorbents are typically basic materials that efficiently bind with CO. Sorbents can be categorized into liquid sorbents, such as alkaline hydroxide solutions and amine-based solvents, and solid sorbents, including metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) and zeolites for example. The efficiency of DAC depends on the performance of these sorbents, which must offer high selectivity, fast CO2 uptake, low energy consumption for regeneration, and long-term stability. Figure 7 illustrates a comprehensive summary of all DAC sorbents found in this review. The following sections will explore each sorbent type in detail, beginning with liquid sorbents and then solid sorbents.

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of the DAC technology and materials used for direct CO2 capture, including liquid and solid sorbents. These materials are being investigated for integration into construction materials to enable carbon-negative buildings.

3.1. Liquid Sorbents

3.1.1. Alkaline Hydroxides

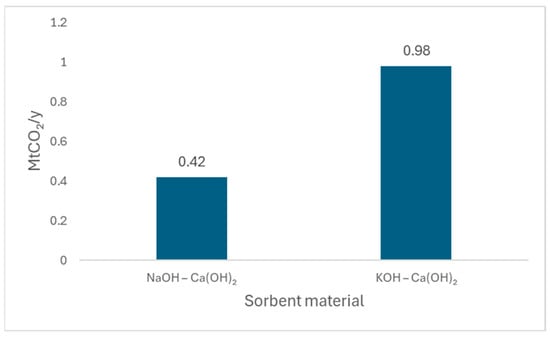

Alkaline hydroxides, including sodium hydroxide NaOH, potassium hydroxide KOH, and calcium hydroxide Ca(OH)2, are among the most widely studied liquid sorbents for Direct Air Capture (DAC) due to their strong chemical reactivity with CO2. These hydroxides absorb CO2 from the atmosphere and convert it into stable carbonate or bicarbonate compounds, effectively removing it from the air. NaOH and KOH are common alkaline sorbents that react efficiently with CO2 to form sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) and potassium carbonate (K2CO3) [119,120]. Figure 8 compares the CO2 capture capacity of two direct air capture (DAC) systems based on alkaline sorbents paired with calcium hydroxide recovery. The NaOH–Ca(OH)2 system, as modeled by Baciocchi et al. [121], achieves a capture rate of 0.42 MtCO2/year under modeled ambient conditions. In contrast, the KOH–Ca(OH)2 system, developed by Carbon Engineering and detailed by Keith et al. [122], demonstrates a significantly higher capture capacity of 0.98 MtCO2/year in a continuous, pilot-validated design. This improvement is attributed to optimized process integration and sorbent regeneration efficiency.

Figure 8.

Comparison of annual CO2 capture capacities for two DAC systems using alkaline sorbents and calcium hydroxide. The NaOH–Ca(OH)2 system, based on the model by Baciocchi et al. [121], captures approximately 0.42 MtCO2 per year, while the KOH–Ca(OH)2 system, developed by Keith et al. [122], achieves a higher capture rate of 0.98 MtCO2 per year.

The primary limitation of NaOH and KOH-based systems is their high-temperature regeneration requirement (>900 °C), where the carbonate compounds must be decomposed in a calcination process to release pure CO2 and regenerate the hydroxide for reuse.

Alternative hydroxide regeneration cycles have been proposed to address this challenge, such as the NaOH–Na2O·3TiO2 cycle, significantly reducing energy consumption by nearly half [122].

Lackner implemented the Ca(OH)2 solution in DAC technology in 1999 [123]. While calcium hydroxide offers strong CO2 capture efficiency, its use in DAC is challenged by high energy requirements for calcination (179.2 kJ per mole of CO2), exceeding the theoretical minimum of 109.4 kJ per mole of CO2. Additionally, drying the precipitated CaCO3 further increases energy demand, making the process more resource-intensive. Another limitation is the low solubility of Ca(OH)2 in water, which restricts its concentration and overall CO2 uptake capacity.

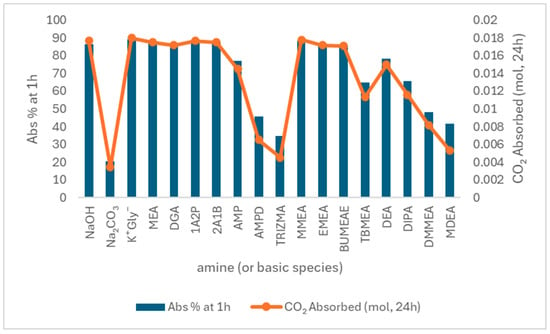

3.1.2. Amines

Amines, particularly alkanolamines, are a widely studied class of sorbents for Direct Air Capture (DAC). Aqueous monoethanolamine (MEA) has long been the benchmark for CO2 capture at industrial point sources. Still, it has proven inefficient for DAC, as its absorption rate drops significantly at low CO2 concentrations (~400 ppm) [124]. Additionally, alkanolamines exhibit lower absorption rates than alkaline hydroxide solutions, undergo oxidative degradation when exposed to oxygen, and require high regeneration energy due to water absorption, making them less favorable in their traditional form [125,126]. However, a recent screening study of different alkanolamines under DAC conditions (0.044% CO2 in air) showed that several amines reached CO2 absorption levels comparable to NaOH after 24 h, with similar absorption rates observed within the first hour [127]. These amines offer the added benefit of potentially lower regeneration energy requirements compared to aqueous alkali hydroxides. As shown in Figure 9, MEA, 1A2P, and 2A1B exhibited both high initial absorption and total uptake, while others, like MDEA, performed significantly lower, highlighting structural and chemical differences in capture efficiency.

Figure 9.

Comparison of CO2 Absorption Efficiency and Uptake by Alkanolamines Under Direct Air Capture Conditions (0.044% CO2 in Air) [127].

Further advancements have been made in pyrrolizidine-based amine sorbents, which demonstrated stable CO2 absorption at 400 ppm over a nine-day period with no signs of oxidative degradation. However, the optimal absorption temperature was not specified [128]. Additionally, researchers have explored incorporating hydrophobic phenyl groups into alkylamines to eliminate water absorption, a major limitation of conventional amine-based systems. It was found that OXDA, MXDA, and PXDA did not absorb any water while still maintaining effective CO2 capture under DAC conditions [129]. While amines offer potential benefits such as lower regeneration temperatures and selective CO2 binding, challenges related to oxidative degradation, sorbent longevity, and environmental concerns remain significant hurdles.

3.1.3. Ionic Liquids

Ionic liquids (ILs) are a promising type of sorbent for Direct Air Capture (DAC) because of their low melting points, high stability, and ability to be customized for better CO2 absorption [130,131]. Unlike traditional amine-based sorbents, ILs have low volatility and require less energy for regeneration, making them attractive for CO2 removal [132]. For DAC applications, Chen et al. [133] developed a pyrene-based polymer with [P4444] [p-2-O] IL, achieving 98.8% CO2 selectivity and enabling CO2 release using visible light, reducing the need for heat-based regeneration. Additionally, functionalized ILs containing amines can interact with CO2 physically and chemically, improving absorption at low CO2 concentrations [134,135]. However, ILs face challenges such as high production costs and difficulties in scaling up.

3.1.4. Low-Regeneration Energy Sorbents

To overcome the high energy demands of conventional DAC systems, researchers have explored low-regeneration energy sorbents that operate at significantly lower temperatures while maintaining effective CO2 capture and release cycles. Custelcean et al. [136] introduced a DAC system using aqueous amino acid salts (potassium sarcosinate and potassium glycinate), where CO2 was captured and later crystallized into hydrated meta-benzene-bis(aminoguanidine) (m-BBIG) carbonate salts at room temperature. The carbonate crystals were then mildly heated (60–120 °C) to release CO2, regenerating the solid m-BBIG sorbent. Unlike alkaline hydroxide systems that require ~900 °C for regeneration, this approach significantly reduces oxidative and thermal degradation and can utilize low-grade waste heat sources. Another promising low-temperature sorbent was developed by Seipp et al. [137], utilizing an aqueous guanidine-based system for DAC. CO2 binds to guanidine, forming carbonate salts stabilized by weak guanidinium–hydrogen bonding, allowing for easy separation via filtration, eliminating the need for energy-intensive evaporation. The sorbent is regenerated at 80–120 °C, making it a more energy-efficient alternative to traditional amine or hydroxide-based DAC systems. The high energy demand for regeneration remains a significant challenge for liquid sorbents, making solid sorbents a more appealing option for Direct Air Capture (DAC). Unlike liquid sorbents, solid sorbents can be regenerated at lower temperatures (below 400 °C), reducing energy consumption. A detailed comparison of all liquid sorbents can be found in Table 4.

Table 4.

Different Liquid Sorbent Types.

3.2. Solid Sorbents

3.2.1. Chemisorption-Based Sorbents

Chemisorption sorbents are materials that capture CO2 through strong chemical bonds, typically offering high selectivity and capacity. Inorganic chemisorption sorbents, such as calcium-based materials (CaO, Ca(OH)2), alkali carbonates (NaHCO3, Na2CO3, NaOH), and metal oxides (Mg(OH)2, MgO), have demonstrated high CO2 adsorption capacities. However, NaHCO3 (Sodium Bicarbonate), Na2CO3 (Sodium Carbonate), and NaOH (Sodium Hydroxide) materials face challenges such as low adsorption rates and high regeneration temperatures (over 927 °C) [138], making them less practical for DAC applications. Additionally, calcium-based sorbents have shown higher adsorption rates than other inorganic sorbents but require elevated temperatures (above 400 °C) for optimal performance.

Although many face performance or scalability challenges, several metal hydroxides and oxides have been evaluated for CO2 capture from ambient air. Magnesium-based sorbents such as Mg(OH)2 and MgO exhibit slow adsorption kinetics, limiting their effectiveness in DAC applications [139]. Zn(OH)2 and LiOH have also been investigated, with Zn(OH)2 showing promising adsorption rates but failing to regenerate efficiently [140,141]. At the same time, LiOH has been used in submarine applications but is not regenerable. AgOH has shown low regeneration energy requirements, but its high cost makes it impractical for large-scale deployment [142].

3.2.2. Physisorption-Based Sorbents

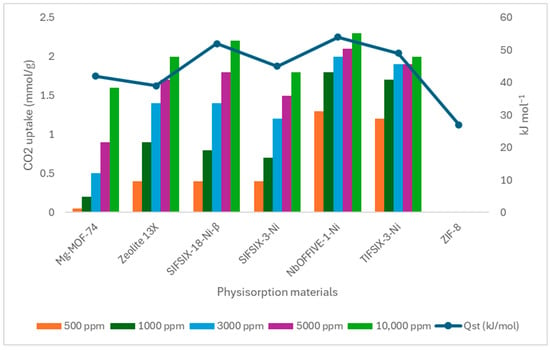

Physisorption sorbents are materials that capture CO2 through weak, reversible physical interactions, primarily van der Waals forces, rather than forming chemical bonds. Inorganic physisorption sorbents, such as zeolites (e.g., Faujasite X, Y, Zeolite 13X, K-LSX, Li-LSX, Na-LSX) and metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) (e.g., Mg-MOF-74, HKUST-1, SIFSIX-3-Ni), rely on these physical adsorption mechanisms. Zeolites, crystalline aluminosilicates, have high surface areas and tunable pore structures that enable selective CO2 adsorption. However, their performance declines in humid environments due to the competition between water vapor and CO2 for adsorption sites, which reduces CO2 selectivity [143,144]. Similarly, MOFs, highly porous hybrid materials composed of metal ions coordinated with organic linkers, have been extensively studied for DAC applications due to their tunable pore sizes and high CO2 selectivity. While MOFs exhibit promising selectivity, they also face challenges related to humidity, as water adsorption can block CO2 uptake. Compared to chemisorption materials, MOFs typically exhibit lower CO2 adsorption capacities [143,145]. Figure 10 presents the CO2 uptake capacities of various physisorbent materials at different concentrations (500–10,000 ppm) under DAC-relevant conditions (298 K). The ultramicroporous material SIFSIX-18-Ni-β, introduced by Mukherjee et al. [145], demonstrates a unique combination of moderate CO2 uptake (0.4 mmol/g at 500 ppm), high isosteric heat of adsorption (52 kJ/mol), fast kinetics, and low water affinity.

Figure 10.

Comparative CO2 uptake and isosteric heat of adsorption for physisorbents at 298 K [145].

3.2.3. Amine-Functionalized Sorbents