Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Neutral O2 does not alter the emission or structure of CsPbBr3 QD films even under UV illumination.

- Reactive oxygen species (ROS) cause rapid PL quenching and lifetime shortening.

- ROS create Br vacancies and Pb–O bonds, generating deep nonradiative traps.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- Oxygen-induced degradation originates from activated oxygen, not molecular O2.

- Plasma processing conditions must be carefully controlled to avoid ROS damage.

- Strategies such as passivation and encapsulation can preserve perovskite stability.

Abstract

The chemical identity of oxygen species plays a decisive role in determining the optical stability of halide perovskite QD films. Here, real-time in situ spectroscopic monitoring, together with steady-state and time-resolved photoluminescence measurements, is utilized to differentiate the effects of molecular oxygen and plasma-activated oxygen species on CsPbBr3 QD films. The films maintain nearly unchanged emission intensity, spectral profile, and carrier lifetimes when stored in vacuum or exposed to molecular O2 even under UV illumination, demonstrating that neutral O2 exhibits minimal reactivity toward the [PbBr6]4− framework. In contrast, oxygen plasma generates highly reactive atomic and ionic oxygen species that induce rapid and spatially heterogeneous photoluminescence quenching. This degradation is attributed to Br− extraction, Br-vacancy formation, and subsequent Pb–O bond generation, which collectively introduce deep trap states and enhance nonradiative recombination. These findings clearly indicate that reactive oxygen species rather than molecular O2 are the dominant driver of oxygen-induced luminescence degradation, providing mechanistic insight and offering processing guidelines for the reliable integration of perovskite nanomaterials in optoelectronic devices.

1. Introduction

Lead halide perovskites have emerged as a new generation of optoelectronic semiconductors due to their exceptional carrier transport properties, high absorption coefficients, and defect-tolerant electronic structure, enabling rapid progress in light-emitting diodes, solar cells, and photodetectors over the past decade [1,2,3,4,5,6]. However, their practical application remains hindered by intrinsic instability that arises from their soft, ionic lattices. In hybrid perovskites such as MAPbI3, the volatility of organic cations (MA+ and FA+) under light, heat, moisture, and oxygen accelerates irreversible phase decomposition [7]. Compared with hybrid systems, all-inorganic cesium lead halide perovskites (CsPbX3, X = Cl, Br, I) show significantly improved thermal and structural stability due to the absence of volatile organic species. Nevertheless, their optical properties still deteriorate under UV illumination, heating, or polar environments [8,9,10]. Considerable efforts have therefore been devoted to improving the stability of CsPbX3 through interface engineering and encapsulation strategies, and encouraging progress has been achieved [11,12,13,14,15,16]. Despite these advances, the mechanistic role of oxygen in perovskite degradation remains a topic of debate.

Early studies suggested that molecular O2 alone exerts only a minimal effect on the stability of MAPbI3, with moisture identified as the dominant factor responsible for ionic loss and phase transformation [7]. In contrast, Bryant et al. observed rapid performance decay of CH3NH3PbI3 devices in dry oxygen under illumination [17]. Subsequent work revealed that oxygen can rapidly diffuse along grain boundaries and halide vacancy sites, where reactive oxygen species form preferentially and induce structural corrosion [18]. More recently, Hidalgo et al. demonstrated a cooperative degradation pathway in which H2O dissolves surface organic cations and I− while O2 oxidizes the exposed Pb–I framework into iodate species, further weakening the perovskite lattice [19]. In parallel, seemingly contradictory observations have been reported for CsPbBr3, where moderate oxygen exposure can temporarily enhance photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) [20]. This “photobrightening” has been attributed to weak molecular O2 adsorption that passivates deep traps at surface Pb-rich or Br-vacancy sites, reducing nonradiative recombination [21]. However, prolonged illumination drives electron transfer to adsorbed oxygen, generating reactive oxygen radicals that erode the Pb–Br framework, extract halides, and ultimately form deep trap states that accelerate optical degradation [21,22].

In this work, we resolve these conflicting interpretations by systematically examining the role of oxygen species in the luminescence stability of CsPbBr3 quantum dot (QD) films through real-time in situ spectroscopic monitoring, complemented by steady-state PL and time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) analyses. We find that neutral molecular O2 exhibits negligible reactivity toward the CsPbBr3 lattice even under UV illumination, while plasma activation generates reactive oxygen species that induce rapid PL quenching, carrier lifetime shortening, and lattice disruption. These results provide direct mechanistic evidence that chemically active oxygen species rather than molecular O2 are responsible for oxygen-induced degradation, offering clear guidance for maintaining optical integrity during materials processing and device fabrication.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of CsPbBr3 QD Films and Oxygen Treatments

A colloidal dispersion of CsPbBr3 QDs (10 mg mL−1 in hexane) was purchased from Nanjing MKNANO Tech. Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China. The QDs were synthesized following the hot-injection protocol developed by Protesescu et al. [1]. The QDs, partially capped with oleic acid and oleylamine ligands, exhibit a PLQY of ~75% and a particle size distribution of 9–11 nm. For film fabrication, the QD solution was spin-coated onto pre-cleaned quartz substrates at 4000 rpm for 30 s, yielding uniform emissive layers.

The as-prepared films were subsequently placed under different oxygen environments, including high vacuum, molecular O2, and oxygen plasma. The plasma treatment was conducted in a very-high-frequency plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (VHF-PECVD) system. During plasma exposure, chamber pressure, flow rate and substrate temperature were controlled at ~20 Pa, 20 SCCM and ~30 °C, respectively.

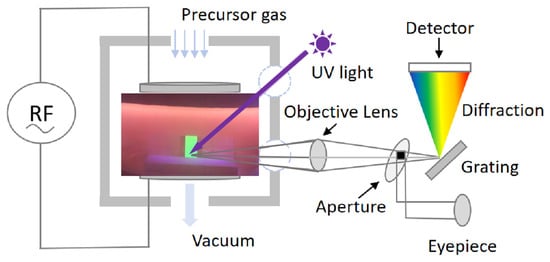

2.2. Real-Time In Situ Spectroscopic Monitoring

In situ luminescence evolution was recorded using a custom diagnostic configuration (schematic shown in Figure 1) in which the VHF-PECVD reactor (self-designed) was directly coupled to a Photo Research PR-655 SpectraScan spectroradiometer (Photo Research Inc., North Syracuse, New York, NY, USA). A 365 nm UV excitation lamp (8 W) was employed to excite the CsPbBr3 QD films during the monitoring process, and the optical emission was continuously collected at room temperature. This setup enabled real-time tracking of emission intensity and spectral changes throughout oxygen exposure.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the real-time and in situ spectroscopic monitoring setup used to record the optical emission of CsPbBr3 QD films in different plasma atmospheres.

2.3. Optical Characterization

Absorption spectra of the CsPbBr3 QD films were measured in transmission mode using a Shimadzu UV-3600 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). Steady-state PL and TRPL measurements were performed on an Edinburgh Instruments FLS1000 spectrometer (Edinburgh Instruments Ltd., Livingston, West Lothian, Scotland, UK) at 300 K. A pulsed 375 nm diode laser (pulse width ~70 ps) served as the excitation source. The emitted photons were detected using a photomultiplier tube (PMT) coupled to a monochromator and analyzed through a time-correlated single-photon counting (TCSPC) module, providing a temporal resolution of approximately 50 ± 4 ps. The steady-state PL excitation density (~0.1 mW cm−2) and TRPL pulse fluence (~0.05 μJ cm−2) were sufficiently low to avoid photobleaching or carrier-induced modification of surface chemistry.

3. Results and Discussion

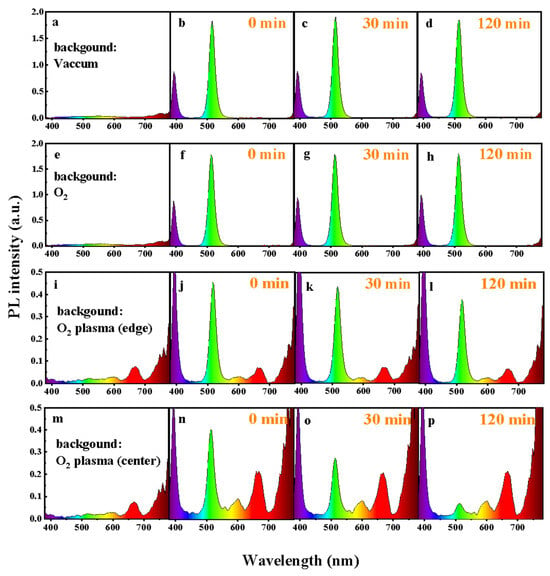

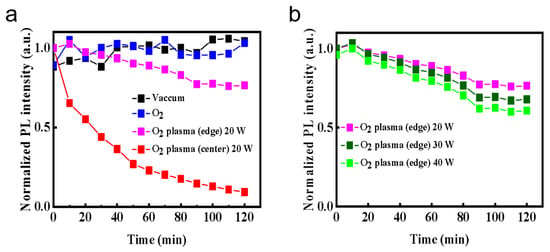

Figure 1 shows the real-time in situ spectroscopic monitoring system equipped with an optical emission detector. Using this setup, we continuously recorded the PL evolution of CsPbBr3 QD films under 365 nm UV excitation, as displayed in Figure 2. The films were measured either in vacuum or in controlled oxygen environments, including molecular O2 and O2 plasma. For the plasma condition, two regions within the discharge zone were selected: the plasma edge and the plasma center, referred to as “O2 plasma (edge)” and “O2 plasma (center),” respectively. In addition to in situ PL tracking, optical emission spectra of the oxygen plasma were recorded under the same VHF conditions. As shown in Figure 2i,m, the discharge exhibits clear emission at ~526 nm (O2+ ionic emission), ~679 nm (excited O*), and ~777 nm (atomic oxygen O, O I transition) [23], confirming that both molecular ionic and atomic oxygen species are present in the plasma at the plasma edge and plasma center. Moreover, under VHF-PECVD conditions, the spatial distribution of reactive oxygen species is expected to vary significantly across the plasma region. At the plasma center, the locally enhanced electron density and strong sheath electric field facilitate electron-impact dissociation of O2, leading to elevated generation of O, O*, and O2+ species. In contrast, at the plasma edge, the sheath potential and ion bombardment are substantially reduced, while neutral ROS efficiently diffuse outward from the plasma bulk, resulting in a lower but still chemically active concentration of reactive oxygen species [24]. As shown in Figure 2, all films exhibit a characteristic CsPbBr3 emission peak at ~515 nm. However, the PL stability varies markedly depending on the chemical state of oxygen. Under vacuum, the PL spectra remain nearly unchanged for over 120 min (Figure 2d), confirming the excellent intrinsic stability of the QDs in the absence of reactive species. Similarly, exposure to molecular O2 results in negligible changes in PL intensity or spectral shape even under UV illumination (Figure 2f–h), indicating that neutral O2 molecules interact weakly with the film surface and do not induce observable degradation. This behavior arises from the absence of moisture, which suppresses the formation of O2− species [22]. These results contrast with previous reports showing transient PL enhancement followed by slow oxidative degradation under prolonged illumination, where photoexcited electrons activate adsorbed O2 into reactive O2− species that attack the Pb–Br framework and create deep trap states [19,20,21,22]. In sharp contrast, exposure to O2 plasma causes conspicuous and rapid PL degradation. When the film is positioned at the plasma center (Figure 2n–p), the PL intensity drops by more than 50% within 30 min (Figure 3a). This severe quenching arises from the combined action of chemically active oxygen radicals and physical ion bombardment [22,25,26,27,28], which together induce surface etching, and lattice distortion. These processes create deep nonradiative trap states, leading to significant emission loss. To decouple the chemical oxidation effects from the physical ion-induced damage, the films were also examined at the plasma edge, where ion energy is greatly reduced while reactive oxygen radicals are still present. In this region, the PL decay proceeds much more gradually (Figure 2j–l). As shown in Figure 3a, the PL decreases by ~10% after 30 min and by ~25% after 120 min, confirming that reactive oxygen species alone can drive degradation, though at a slower rate. Moreover, increasing the plasma power at the plasma edge accelerates PL quenching (Figure 3b), further demonstrating that the concentration of reactive oxygen species rather than ion bombardment is the dominant factor governing luminescence degradation. As shown in Figure 2i,m, the oxygen plasma generates species such as O* and O via electron-impact dissociation and excitation. These highly reactive species can extract Br− and oxidize the Pb–Br framework, leading to the formation of Pb–O bonds and deep-level defects that promote nonradiative recombination and accelerate emission decay [8,19]. Collectively, these results clarify that CsPbBr3 QD films exhibit long-term luminescence stability in vacuum and molecular O2 even under UV illumination, whereas reactive oxygen species are the primary drivers of degradation, with the extent of damage directly correlated to their concentration and activity.

Figure 2.

Optical emission spectra for different gas atmosphere and CsPbBr3 QD films modified in: (a–d) vacuum, (e–h) O2, (i–l) the edge of O2 plasma, and (m–p) the center of O2 plasma. During plasma exposure, the RF power, chamber pressure, flow rate and substrate temperature were controlled at 30 W, ~20 Pa, 20 SCCM and ~30 °C, respectively.

Figure 3.

Time-dependent evolution of the normalized PL intensity of CsPbBr3 QD films under different oxygen environments (a) and O2 plasma with different RF powers (b).

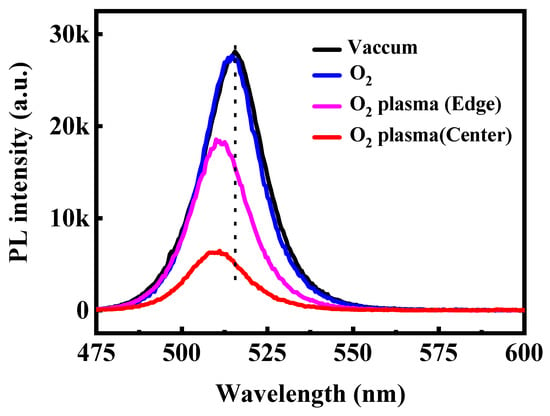

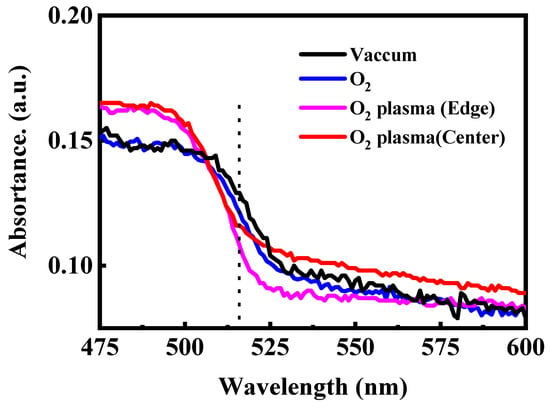

To further verify the impact of oxygen species on the optical stability of CsPbBr3 QD films, steady-state PL and UV–vis absorption spectra were recorded after 120 min of exposure to different oxygen atmospheres. As shown in Figure 4, when maintained in vacuum or placed in molecular O2, the films retain nearly identical PL intensity and spectral shape, with the emission peak remaining at ~515 nm. The absence of peak shift or intensity loss confirms that neutral O2 molecules exert negligible influence on the emissive behavior of CsPbBr3 QDs in the absence of activation pathways such as light-driven charge transfer or humidity-assisted reactions. In contrast, O2 plasma leads to pronounced PL attenuation. The film located at the plasma edge exhibits a moderate reduction in emission intensity, while the film placed at the plasma center shows severe quenching, with more than two-thirds of the PL intensity lost after 120 min. This spatially dependent degradation reflects the varying densities of reactive oxygen species and energetic ions across the plasma region. We note that the PL quenching induced by O2 plasma is irreversible, indicating that the CsPbBr3 QD degradation arises from permanent structural and chemical modifications. A noticeable blue shift in the PL peak emerges upon plasma exposure, likely arising from plasma-induced surface etching, which reduces the average particle size and thereby enhances quantum confinement. The UV–vis absorption spectra shown in Figure 5 exhibit a consistent trend. Films preserved in vacuum or exposed to molecular O2 show nearly unchanged absorption edges, indicating stable crystal and electronic structures. Conversely, films treated with O2 plasma show a shift of the absorption edge toward shorter wavelengths accompanied by a decrease in absorbance intensity. This effect is most prominent at the plasma center, where the flux of reactive oxygen and ions is highest. The coincident blue shift in both PL emission and absorption confirms that reactive oxygen species produced by O2 plasma not only induces chemical oxidation but also physically erodes the QD surface, narrowing the effective particle size and widening the optical bandgap.

Figure 4.

PL spectra of the CsPbBr3 QDs treated in the different conditions excited by the 365 nm line from Xe lamp.

Figure 5.

UV–vis absorption spectra of the CsPbBr3 QDs treated in the different conditions.

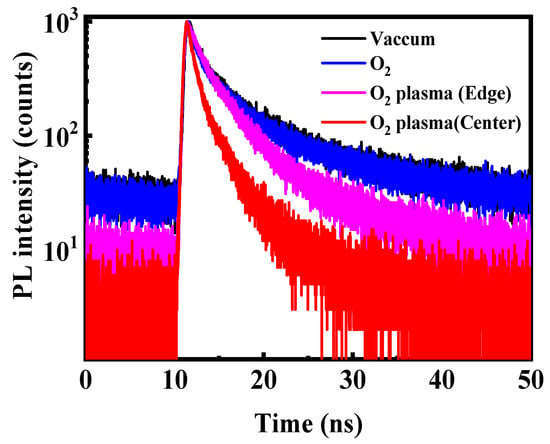

To further resolve the carrier recombination pathways associated with oxygen-induced degradation, TRPL measurements were conducted on CsPbBr3 QD films after exposure to different oxygen environments (Figure 6). All decay curves were well described by a bi-exponential function [29]:

where K1 and K2 represent the fractional contributions of fast and slow decay components, and τ1 and τ2 correspond to their respective lifetimes. The fast component (τ1) reflects trap-assisted nonradiative recombination, while the slow component (τ2) corresponds to intrinsic radiative recombination within well-passivated domains [30]. The fitted parameters are summarized in Table 1, and the average PL lifetime (τave) was calculated according to the method described in Ref. [29]. For films stored in vacuum or exposed to molecular O2, the decay dynamics remain dominated by the slow radiative component (K2 ≈ 86%), with τ2 ≈ 7.5–7.6 ns and an average lifetime of ~6.7 ns. The nearly unchanged τ1, τ2, and K1/K2 ratios indicate that neutral O2 molecules do not introduce additional trap states nor disrupt the lattice, consistent with the steady-state PL and absorption results. This stability originates from the chemical inertness of ground-state O2, whose strong O=O bond prevents spontaneous halide abstraction or Pb2+ oxidation in the absence of activation energy. In contrast, O2 plasma treatment leads to a pronounced acceleration of carrier decay. The film located at the plasma center exhibits the shortest τ1 (0.8 ns) and the highest contribution of the fast component (K1 = 49.0%), signifying the emergence of abundant nonradiative recombination sites. Such behavior results from the combined chemical and physical impact of reactive oxygen radicals and energetic ions, which disrupt surface passivation, remove ligands, and distort the Pb–Br framework. At the plasma edge, where ion bombardment is significantly mitigated but reactive oxygen radicals remain present, τ1 increases to 1.3 ns and K1 decreases to 23.5%. This intermediate behavior confirms that reactive oxygen species alone are sufficient to form trap states, albeit more slowly.

R(t) = K1exp(−t∕τ1) + K2exp(−t∕τ2)

Figure 6.

Time-resolved PL decay curves of the CsPbBr3 QD films treated in the different conditions excited by the 372 nm pulse laser.

Table 1.

Summary of the fitting parameters for the PL decay traces of the CsPbBr3 QD films treated in the different conditions.

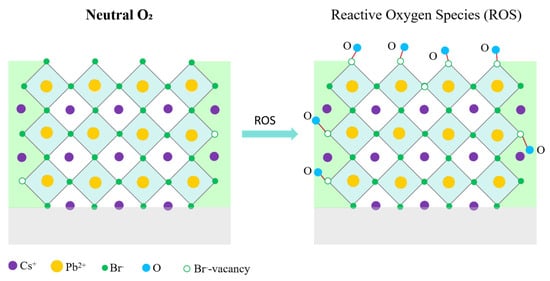

Thus, the collective TRPL, steady-state PL, and absorption results establish a clear mechanistic distinction between neutral O2 molecules and activated oxygen species in determining the optical stability of CsPbBr3 QDs, as is shown in Figure 7. Molecular O2, possessing a strong O=O bond and limited surface reactivity, does not disrupt the [PbBr6]4− coordination environment even under photoactivated conditions and therefore preserves long-lived radiative recombination. In contrast, oxygen plasma produces highly reactive species (O, O*, and O2+) capable of abstracting Br− and creating Br vacancies (VBr), which in turn facilitate the formation of Pb–O bonds and lattice distortion [8,19]. These structural perturbations introduce deep trap states and significantly increase nonradiative recombination pathways, consistent with the accelerated τ1 and increased K1 components observed in TRPL analysis. Thus, the luminescence degradation of CsPbBr3 QDs originates from chemically active oxygen species rather than neutral molecular oxygen even under photoactivated conditions.

Figure 7.

Schematic mechanism distinguishing the inert effect of molecular O2 and the degradative role of reactive oxygen species in CsPbBr3 QD films.

4. Conclusions

In summary, we have elucidated the distinct roles of neutral molecular oxygen and plasma-activated reactive oxygen species in governing the optical stability of CsPbBr3 QD films through real-time in situ monitoring combined with steady-state and time-resolved spectroscopies. Under illumination, neutral O2 shows negligible interaction with the [PbBr6]4− lattice, and both photoluminescence intensity and carrier lifetime remain stable. In contrast, oxygen plasma generates reactive oxygen species (O, O*, and O2+) that extract Br−, create halide vacancies, and induce Pb–O bond formation, leading to an increase in deep trap states and enhanced nonradiative recombination. These processes result in rapid luminescence degradation. This work identifies activated oxygen species rather than molecular O2 as the true origin of oxygen-induced instability. We note that the current experimental setup does not permit quantitative determination of ROS concentration or flux at different plasma positions. Developing calibrated ROS profiling to distinguish chemical oxidation from ion-induced effects, and extending these insights to device-relevant environments and other perovskite compositions, will be important directions for future work. Overall, the mechanistic insights gained here offer practical implications for plasma processing, surface passivation, and encapsulation strategies to enhance the reliability of halide perovskite-based optoelectronic devices.

Author Contributions

Z.L.: investigation, formal analysis, writing—original draft. J.S.: investigation. H.W.: formal analysis. H.L.: investigation, formal analysis. R.H.: writing—review and editing, formal analysis, funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 62504066), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation, Research Projects of the Department of Education of Guangdong Province (2024ZDZX1026), and Program of Hanshan Normal University (XTP202402).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Protesescu, L.; Yakunin, S.; Bodnarchuk, M.I.; Krieg, F.; Caputo, R.; Hendon, C.H.; Yang, R.X.; Walsh, A.; Kovalenko, M.V. Nanocrystals of Cesium Lead Halide Perovskites (CsPbX3, X = Cl, Br, and I): Novel Optoelectronic Materials Showing Bright Emission with Wide Color Gamut. Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 3692–3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Yan, M.; Zhou, L.; Xu, L.; Fang, Y.; Yang, D. Efficient and High-Radiance Silicon-Based Perovskite Light-Emitting Diodes through Phase Segregation Control. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2024, 6, 2003–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhu, T.; Xiao, K.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, D.; Xu, L.; Xu, J.; Chen, K. High-Efficiency Air-Processed Si-Based Perovskite Light-Emitting Devices via PMMA-TBAPF6 Co-Doping. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2022, 10, 2102848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Li, J.; Grater, L.; Guo, R.; bin Mohd Yusoff, A.R.; Sargent, E.; Tang, J. Vapour-Deposited Perovskite Light-Emitting Diodes. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2024, 21, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Di Stasio, F.; Bi, C.; Zhang, J.; Xia, Z.; Shi, Z.; Manna, L. Near-Infrared Light Emitting Metal Halides: Materials, Mechanisms, and Applications. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2312482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Lin, Z.; Wu, H.; Huang, R.; Song, J.; Chen, K.; Xia, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Hou, D.; et al. Plasma-Enhanced Grain Growth and Non-Radiative Recombination Mitigation in CsSnBr3 Perovskite Films for High-Performance, Lead-Free Photodetectors. Small 2025, 21, 2411086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, C.; Xie, F.; Yang, J.; Gao, Y. Degradation by Exposure of Coevaporated CH3NH3PbI3 Thin Films. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 23996–24002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Li, Z.; Wang, B.; Zhu, N.; Zhang, C.; Kong, L.; Zhang, Q.; Shan, A.; Li, L. Morphology Evolution and Degradation of CsPbBr3 Nanocrystals under Blue Light-Emitting Diode Illumination. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 7249–7258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Hou, X.; Li, J.; Qu, C.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, J.; Li, H. Thermal Degradation of Luminescence in Inorganic Perovskite CsPbBr3 Nanocrystals. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 8934–8940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loiudice, A.; Saris, S.; Oveisi, E.; Alexander, D.T.L.; Buonsanti, R. CsPbBr3 QD/AlOx Inorganic Nanocomposites with Exceptional Stability in Water, Light and Heat. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 10696–10701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Huang, R.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Song, J.; Li, H.; Hou, D.; Guo, Y.; Song, C.; Wan, N.; et al. Highly Luminescent and Stable Si-Based CsPbBr3 Quantum-Dot Thin Films Prepared by Glow-Discharge Plasma with Real-Time and In Situ Diagnosis. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1805214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarnkar, A.; Mir, W.J.; Nag, A. Can B-Site Doping or Alloying Improve Thermal- and Phase-Stability of All-Inorganic CsPbX3 (X = Cl, Br, I) Perovskites? ACS Energy Lett. 2018, 3, 286–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Zeng, Y.-J.; Steele, J.A.; Roeffaers, M.B.J.; Hofkens, J.; Debroye, E. Phase Stabilization of Cesium Lead Iodide Perovskites for Use in Efficient Optoelectronic Devices. NPG Asia Mater. 2024, 16, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chhillar, P.; Dhamaniya, B.P.; Pathak, S.K.; Karak, S. The Compound Effect of Mg and Tris(2-aminoethyl)amine for Long-Term Phase Stability in the γ-CsPbI3 Perovskite Film. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2023, 5, 4984–4995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-M.; Jeong, E.-H.; Kim, H.-S.; Choi, S.-Y.; Park, M.-H. Photoluminescence Enhancement in Perovskite Nanocrystals via Compositional, Ligand, and Surface Engineering. Materials 2025, 18, 4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Que, J.; He, J.; Peng, C.; Jiao, Y.; Zhao, D.; Liu, D.; Li, H.; Tang, Z.; et al. Enhanced Stability and Luminescence Efficiency of CsPbBr3 PQDs via In Situ Growth and SiO2 Encapsulation in Surface-Functionalized Mesoporous Silica Nanospheres. Small 2025, 21, 2412581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, D.; Aristidou, N.; Pont, S.; Sanchez-Molina, I.; Chotchunangatchaval, T.; Wheeler, S.; Durrant, J.R.; Haque, S.A. Light and Oxygen Induced Degradation Limits the Operational Stability of Methylammonium Lead Triiodide Perovskite Solar Cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 1655–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristidou, N.; Eames, C.; Sanchez-Molina, I.; Bu, X.; Kosco, J.; Islam, M.S.; Haque, S.A. Fast Oxygen Diffusion and Iodide Defects Mediate Oxygen-Induced Degradation of Perovskite Solar Cells. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, J.; Kaiser, W.; An, Y.; Li, R.; Oh, Z.; Castro-Méndez, A.-F.; LaFollette, D.K.; Kim, S.; Lai, B.; Breternitz, J.; et al. Synergistic Role of Water and Oxygen Leads to Degradation in Formamidinium-Based Halide Perovskites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 24549–24557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, M.; Yi, Z.; Reichert, S.; Luo, X.; Lin, W.; Zhang, Z.; Bao, C.; Zhang, R.; Bai, S.; Zheng, G.; et al. Mixed Halide Perovskites for Spectrally Stable and High-Efficiency Blue Light-Emitting Diodes. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangguan, Z.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, J.; Lin, W.; Guo, W.; Li, C.; Wu, T.; Lin, Y.; Chen, Z. The Stability of Metal Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals—A Key Issue for the Application on Quantum-Dot-Based Micro Light-Emitting Diodes Display. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaya, M.; Galisteo-López, J.F.; Calvo, M.E.; Espinos, J.P.; Miguez, H. Origin of Light Induced Photophysical Effects in Organic Metal Halide Perovskites in the Presence of Oxygen. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 3891–3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, F.; Abbasi-Firouzjah, M.; Shokri, B. Investigation of antibacterial and wettability behaviours of plasma-modified PMMA films for application in ophthalmology. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2014, 47, 085401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, V.V.; Klopovsky, K.S.; Lopaev, D.V.; Rakhimov, A.T.; Rakhimova, T.V. Experimental and theoretical investigation of oxygen glow discharge structure at low pressures. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 1999, 27, 1279–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrotta, A.; Covella, S.; Russo, F.; Palumbo, F.; Milella, A.; Armenise, V.; Fracassi, F.; Rizzo, A.; Colella, S.; Kaiser, W.; et al. Plasma-Driven Atomic-Scale Tuning of Metal Halide Perovskite Surfaces: Rationale and Photovoltaic Application. Sol. RRL 2023, 7, 2300345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zheng, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Xiao, J.; Pang, S.; Dong, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, K.; et al. Plasma Sputtering Halide Perovskite for Photovoltaic Applications. ACS Mater. Lett. 2024, 6, 5076–5092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Lin, Z.; Song, J.; Huang, R.; Wu, H.; Chen, K.; Xia, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Guo, Y.; et al. High-Performance Ammonia Plasma-Processed CsPbBr3 Perovskite Photodetectors. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2025, 7, 5404–5411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, M.A.; Lichtenberg, A.J. Principles of Plasma Discharges and Materials Processing, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, K.-H.; Liou, S.-C.; Chen, W.-L.; Wu, C.-L.; Lin, G.-R.; Chang, Y.-M. Tunable and Stable UV-NIR Photoluminescence from Annealed SiOx with Si Nanoparticles. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 23416–23424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-H.; Kim, J.S.; Lee, T.-W. Strategies to Improve Luminescence Efficiency of Metal-Halide Perovskites and Light-Emitting Diodes. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1804595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).