Abstract

Molybdenum oxide (MoOX) has been widely utilized as a hole transport layer (HTL) in crystalline silicon (c-Si) solar cells, owing to characteristics such as a wide bandgap and high work function. However, the relatively low conductivity of MoOX films and their poor contact performance at the MoOX-based hole-selective contact severely degrade device performance, particularly because they limit the fill factor (FF). Oxygen vacancies are of paramount importance in governing the conductivity of MoOX films. In this work, MoOX films were modified through ultraviolet irradiation (UV-MoOX), resulting in MoOX films with tunable oxygen vacancies. Compared to untreated MoOX films, UV-MoOX films contain a higher density of oxygen vacancies, leading to an enhancement in conductivity (2.124 × 10−3 S/m). In addition, the UV-MoOX rear contact exhibits excellent contact performance, with a contact resistance of 20.61 mΩ·cm2, which is significantly lower than that of the untreated device. Consequently, the application of UV-MoOX enables outstanding hole selectivity. The power conversion efficiency (PCE) of the solar cell with an n-Si/i-a-Si:H/UV-MoOX/Ag rear contact reaches 24.15%, with an excellent FF of 84.82%.

1. Introduction

Crystalline silicon (c-Si) solar cells continue to dominate the photovoltaic market, primarily owing to their abundant raw material resources, extended operational lifetime, and high power conversion efficiency (PCE) [1,2,3]. Silicon heterojunction (SHJ) cells attain superior passivation performance by employing double-sided i-a-Si:H passivation layers. Meanwhile, the doped silicon layers, namely n-type amorphous silicon (n-a-Si:H) and p-type nanocrystalline silicon (p-nc-Si:H), demonstrate excellent carrier selectivity, ultimately leading to a high PCE of 26.81% [4]. Notably, integrating heterojunction with back-contact (IBC) structures has further pushed certified cell efficiencies of 27.81% [5]. However, the utilization of doped silicon films in SHJ solar cells poses several challenges. Firstly, the fabrication of doped silicon films involves costly deposition processes and the use of toxic gas precursors [6]. Moreover, their narrow bandgap (Eg) leads to optical parasitic absorption and free carrier absorption losses, which can constrain the enhancement of the short circuit current density (Jsc) in solar cells [7,8,9]. To address these issues of parasitic absorption and process cost, researchers have used wide-bandgap materials instead of doped silicon layers, such as transition metal oxides (TMOs), alkali metal fluorides [10,11,12,13,14], and organic compounds [15,16,17]. Among these materials, easily fabricable TMOs with a high work function—such as MoOX [18,19], V2OX [20], WOX [21,22,23] and CrOX [24]—are considered to be promising hole transport layers (HTLs) and have attracted extensive research interest. High-WF TMOs in non-stoichiometric forms contain oxygen vacancies. The density of oxygen vacancies is closely related to the film’s properties, including work function and conductivity. As the valence state of the metal cation in TMOs decreases, attributed to an increase in oxygen vacancy density, the WF of these TMOs decreases [25]. On the other hand, the conductivity of high-WF TMOs originates from oxygen vacancies that donate electrons, resulting in n-type conductivity [26,27]. Among various TMO materials, MoOX demonstrates superior performance due to its higher work function and wider bandgap. Upon the deposition of MoOX via thermal evaporation for use as the HTL, the solar cell attains the highest device efficiency, at 23.83%; yet, it simultaneously exhibits a high contact resistance (ρc) of 177 mΩ·cm2 [28]. In addition, MoOX exhibits poor film conductivity [29]. The high ρc and low conductivity limit the transport of photogenerated holes, thereby limiting the improvement of fill factor (FF) and Jsc [30,31]. As predicted by Gao et al., an excellent FF (>83%) can be achieved when ρc is below 80 mΩ·cm2 and contact recombination current density (J0c) is less than 5 fA·cm−2 [32].

Enhancing the electrical performance of MoOX-based c-Si compound cells, including reducing contact resistance and improving conductivity, is an essential approach for achieving high-efficiency cells. Li et al. used MoO2 as the evaporation source to fabricate MoOX films with a low oxygen content. Compared to high-oxygen-content films, these low-oxygen-content films demonstrated superior contact performance, with ρc decreasing from 121.38 mΩ·cm2 to 15.06 mΩ·cm2 [33]. However, when MoO2 serves as an evaporation precursor, it undergoes disproportionation during the high-temperature, oxygen-free process, leading to the formation of products like MoO3 and consequently complicating the control of film composition [34]. Research has revealed that adopting a bilayer structure can effectively enhance the conductivity of the film. Li et al. found that a MoOX/NiOX bilayer HTL structure exhibits higher conductivity compared to a single layer (MoOX or NiOX). Moreover, the MoOX/NiOX bilayer optimizes the energy band structure, thereby promoting hole-elective transport and resulting in a high FF [35]. In a separate study by Lu et al., a MoOX/Au/MoOX (MAM) multilayer composite used as the HTL, effectively improved the device’s contact performance, as reflected by a lower ρc value of 62.42 mΩ·cm2. The incorporation of a Au interlayer promotes the generation of oxygen vacancies in MoOX, thereby increasing the conductivity of the MAM composite HTL, which ranges from 8.02 × 10−3 S/m to 7.592 × 10−2 S/m, facilitating hole extraction, and achieving a high FF of 85.2% [36]. However, introducing Au into the MoOX/Au/MoOX multilayer raises device costs. Although multilayer HTLs demonstrate significant promise for enhancing film conductivity and contact performance, the fabrication of bilayer or multilayer structures inevitably adds to the complexity of the manufacturing process.

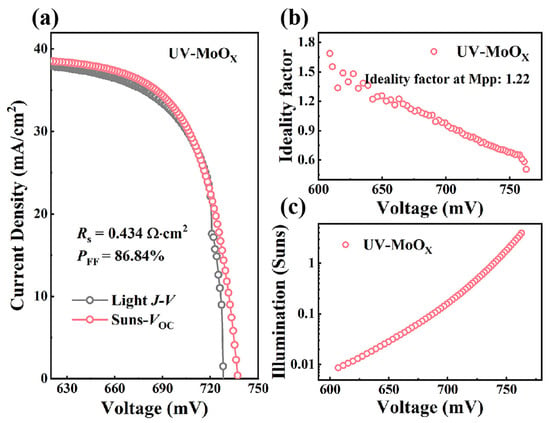

In this work, thermally evaporated MoOX was employed as the HTL for n-Si solar cells, and tunable oxygen vacancy density in MoOX films was achieved via ultraviolet (UV) irradiation for varying durations. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis revealed that as UV exposure time increased, both the Mo6+/Mo5+ ratio and O/Mo ratio gradually decreased. This trend clearly indicates that UV irradiation induces a reduction in MoOX, leading to a corresponding increase in oxygen vacancy density. By comparing the MoOX film with optimal UV exposure of 60 min, denoted as UV-MoOX, to the untreated MoOX film, the UV-MoOX film exhibited a higher conductivity of 2.124 × 10−3 S/m. Meanwhile, ultraviolet photo-electron spectroscopy (UPS) measurements showed that the WF of the UV-MoOX film was 5.05 eV, which is nearly comparable to that of the untreated MoOX film (WF = 5.10 eV). In essence, a MoOX film with both high conductivity and a high WF was achieved via 60 min of UV irradiation. Contact resistance measurements further confirmed superior contact performance when using the UV-MoOX film as HTL, with the ρc decreasing from 91.21 mΩ·cm2 to 20.61 mΩ·cm2. Moreover, by comparing the experimental current–voltage (I–V) curve and the pseudo-I–V curve derived from Suns-Voc measurements, we found that the device with UV-MoOX as the HTL exhibited a lower series resistance of 0.434 Ω·cm2 and a higher pseudo-fill factor (pFF) of 86.84%. This UV treatment strategy effectively enhanced the device’s electrical performance, resulting in an FF of 84.82% and an open circuit voltage (Voc) of 729 mV. The successful application of UV-MoOX in c-Si solar cells provides valuable new insights into the controllable modulation of properties in high-WF TMO materials.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Device Fabrication

n-type silicon compound heterojunction solar cells were fabricated using n-Si wafers with a resistivity and thickness of 1.2–1.5 Ω·cm and 130 μm, respectively. The n-Si wafers were first cleaned and textured via a wet chemical process. An 8 nm i-a-Si:H thin film was prepared using radio frequency plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD) on the front and back of the silicon wafer. After that, an n-nc-SiOx:H layer was deposited on the front and a SiNX layer on the back, using PECVD. On the front side of the cell, the TCO layer was deposited using magnetron sputtering, consisting of In2O3 doped with 10 wt% SnO2. The silver grid electrode was printed and then annealed at 190 °C for 30 min. Before depositing MoOX, the rear side was cleaned using HF at a concentration of 2%. MoOX (approximately 7 nm) and Ag (200 nm) were thermally evaporated onto the rear of the solar cell at rates of 0.1 Å/s and 1.5 Å/s, respectively. This structure served as the control group. Additionally, for the samples treated with ultraviolet lamp, an approximately 7 nm MoOX film was deposited on the rear of the solar cell via thermal evaporation, at a rate of 0.1 Å/s. The chamber was then opened, and the MoOX film was exposed to ultraviolet lamps (wavelength 365 nm, power 7 W) for various times (30 min, 60 min, and 120 min) in a glove box. The UV spot was configured as a circular area with a radius of 10 cm, while the sample size was 4 × 4 cm2. Since the spot size was larger than the sample, the entire device surface received uniform UV irradiation during treatment. Following this, a 200 nm Ag film was deposited using thermal evaporation at a rate of 1.5 Å/s. Throughout the thermal evaporation process, the pressure inside the chamber remained below 5 × 10−4 Pa. Both the thermal evaporation and ultraviolet treatment processes were conducted in a nitrogen environment. The brief vacuum interruption between the MoOX and Ag deposition did not adversely affect device performance. For detailed experimental data, please refer to Table S1. The detailed experimental flowchart is provided in Figure S1 of the Supporting Information.

2.2. Material Characterization

The work function, elemental composition, and chemical state of the film were characterized by UPS and XPS. These analyses utilized a monochromatic Al Kα X-ray source with a photon energy of 1486.7 eV, implemented on a ESCALab 250Xi measurement system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). All acquired XPS spectra were processed and deconvoluted using Advantage 5.99 software, employing a mixed Lorentz–Gaussian (GL) line shape for fitting. Additionally, all spectra were calibrated using the carbon C1s peak at 284.8 eV as a reference. The film conductivity was measured by the two-probe method using a 2450 digital source meter (Keithley, Beaverton, OR, USA) and computationally fitted. The test samples were composed of p-Si/Ag/MoOX/Ag and p-Si/Ag/UV-MoOX/Ag structures. A 200 nm layer of Ag was initially deposited onto a p-Si wafer. Subsequently, a mask with circular holes of different diameters was applied to define the area within which either MoOX or UV-MoOX was deposited. This was followed by another 200 nm of Ag through thermal evaporation deposition. The ρc measurements were performed using the ECSM. More details on the calculation methods are provided in Note S1, Supporting Information.

2.3. Solar Cell

The light and dark J–V characteristics of the solar cell (4 × 4 cm2) were recorded using a Class AAA Scisun solar simulator (Sciencetech, London, ON, Canada) and a Keithley 2450 source meter under standard 1 sun conditions (100 mW·cm−2, AM 1.5 G spectra, 25 °C), and the luminescence intensity was calibrated using a certified Fraunhofer Cal Lab reference cell. The EQE was obtained using a QE-R (Enlitech, Kaohsiung City, Taiwan) measurement system. The dark τeff and J0c values were evaluated using the QSSPC method. The device architectures used in the test were MoOX/i-a-Si:H/n-Si/i-a-Si:H/MoOX and UV-MoOX/i-a-Si:H/n-Si/i-a-Si:H/UV-MoOX, enabling the measurements of τeff with a lifetime tester (WCT-120MX) (Sinton Instruments, Boulder, CO, USA). The pseudo-light-J–V curves were extracted from a Suns-Voc measurement. The Suns-Voc module of a Sinton WCT-120 instrument (Sinton Instruments, Boulder, CO, USA) was used to collect changes in the voltage of the device by reducing the light intensity of the flashlight; these were computationally transformed into Suns-Voc curves.

2.4. Simulation

Quokka2 was utilized for the PLA of the solar cells with MoOX and UV-MoOX. For the Quokka2 simulation, the unit cell was modeled in two dimensions to calculate the power loss in the transversal transport of carriers. The input parameters were primarily obtained from the measurements described in Section 2.2. The line resistance of the finger and the contact resistivity of the heterojunction were considered to be series resistance in an external circuit. The optical path-length factor (Z) was set as 4n2: the simulated Jsc to that of actual cells. Richter’s Auger mode was chosen, and the value of radiation recombination was changed to 0.4 × Brad, with a photon recycling probability of 0.6. Other parameters employed in the simulation are listed in Table S2.

3. Results and Discussion

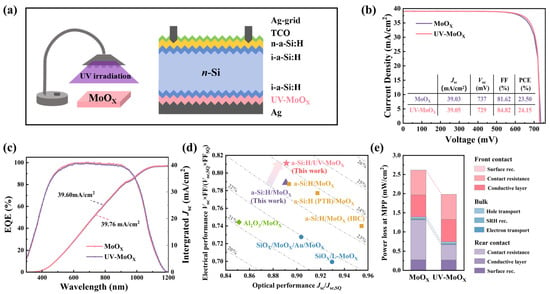

Figure 1a illustrates the process of treating MoOX films with UV irradiation, alongside the structure of a n-Si solar cell featuring a full rear contact geometry of UV-MoOX/i-a-Si:H/Ag. The cross-sectional TEM image of the rear-side structure of the solar cell is shown in Figure S2. First, we optimized the UV irradiation time and compared the solar cells’ current density–voltage (J–V) parameters at different processing times (0 min, 30 min, 60 min, and 120 min) (Figure S3, Supporting Information). When the UV irradiation time was 30 min, the solar cell FF showed a slight improvement. When the UV irradiation time was 60 min, the devices with UV-MoOX film as the HTL performed the best, with the most significant improvement observed in the FF. However, when the irradiation time exceeded 60 min, the FF decreased, leading to a reduction in overall device performance. Figure 1b shows the J–V characteristics of n-Si solar cells, using MoOX and UV-MoOX as the HTL. When MoOX is used as the HTL, the efficiency reaches 23.5%. In comparison with MoOX-based devices, when UV-MoOX serves as the HTL, Voc exhibits a slight decrease; however, the FF is significantly enhanced from 81.62% to 84.82%, leading to an improved device PCE of 24.15%. As shown in Figure 1c, the integrated Jsc values calculated from the external quantum efficiency (EQE) response of MoOX and UV-MoOX solar cells are 39.60 and 39.76 mA/cm2, respectively. EQE curves demonstrate subtle differences in the Jsc of the UV-MoOX and MoOX devices, but changes in optical performance are not the key factor contributing to improved device performance. Figure 1d presents a comparison of the optical and electrical performance between different solar cells, including this work and previous studies conducted by others. The figure further highlights the substantial improvement in the electrical performance of UV-MoOX devices, relative to MoOX. Notably, the UV-MoOX devices in this study exhibit superior PCE in comparison to that of other MoOX-based HTL devices featured in previous studies, which can be primarily attributed to the significant improvement in electrical performance. To analyze the reasons for the improvement in the device’s electrical performance, simulations were conducted using quokka 2 under the free energy loss analysis (FELA) method to study the power loss of the devices. As shown in Figure 1e, the power loss is divided into three regions: the front electron-selective contact structure (ESC), the bulk silicon (bulk), and the rear hole-selective contact structure (HSC). Figure 1e also shows that, from the MoOX to the UV-MoOX device, the total power loss at the rear HSC alone decreased from 1.31 to 0.66 mW/cm2, while the total power loss in the front ESC and bulk region showed no significant change. The total power loss at the rear HSC was almost equivalent to a reduction in total power loss, which indicates that the improvement in the solar cell’s electrical performance was primarily due to the rear HSC [4]. The contact resistance loss was reduced most significantly, from 1.03 to 0.39 mW/cm2, which facilitates excellent contact performance.

Figure 1.

(a) The process of UV treatment MoOX and the cross-sectional schematics of the solar cell with n-Si/i-a-Si:H/UV-MoOX rear contact. (b) J–V parameters of solar cells with MoOX and UV-MoOX. (c) EQE responses and integrated Jsc values of champion solar cells, with MoOX and UV-MoOX as the HTL. (d) Comparison of optical and electrical performance of solar cells in this work with previous works [18,28,33,36,37,38]. (e) Free energy loss analysis of solar cells with MoOX and UV-MoOX.

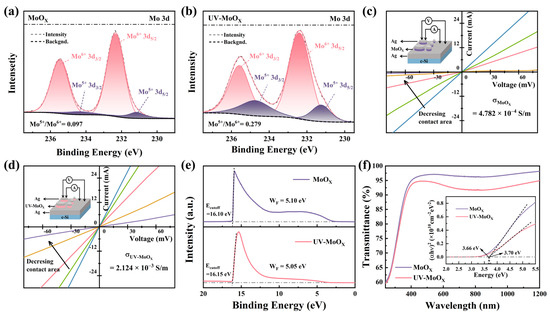

To evaluate the performance differences between MoOX and UV-MoOX devices, first, the properties of the two films were compared. XPS analysis was employed to investigate the chemical bonding of MoOX and UV-MoOX films deposited onto silicon substrates, as depicted in Figure 2a,b. Both films evaporated by MoO3 sources, with a thickness of approximately 7 nm, exhibited Mo5+ and Mo6+ components in the Mo 3d core level, respectively. The Mo6+ 3d5/2 and Mo5+ 3d5/2 peaks were centered at 232.35 and 231.15 eV, respectively, in rigorous agreement with previous works [36,39,40]. In Figure 2a, the Mo5+/Mo6+ ratio was calculated as 0.097, indicating Mo6+ to be the predominant component. In contrast, the Mo5+/Mo6+ ratio was 0.279 for the UV-MoOX film, as shown in Figure 2b. The different Mo5+/Mo6+ ratios between the two films indicate that UV irradiation has a reducing effect on MoOX film, which increases Mo5+/Mo6+ in UV-MoOX. Specifically, MoOX generates electron–hole pairs under UV irradiation, according to the following Equation (1):

where h is Planck’s constant; v is the frequency of UV radiation; and e− and h+ denote an electron and a hole, respectively. The photo-induced electrons in the conduction band are trapped by Mo6+ ions, which are thereby transformed into Mo5+ ions [41,42]. Furthermore, the O/Mo ratio of MoOX and UV-MoOX films was determined to be 2.955 and 2.890, respectively (calculated by Figure S3, Supporting Information). The O/Mo ratio of MoOX was similar to that observed in MoO3 films [43]. The lower O/Mo ratio in UV-MoOX indicates that there are more oxygen vacancies in MoOX film after UV irradiation. In order to verify the effect of UV irradiation time on the composition of MoOX film, we measured the Mo 3d core level of MoOX film with a 120 min UV treatment (Figure S4, Supporting Information). As UV irradiation time grew, the Mo5+/Mo6+ ratio rose, while the O/Mo ratio decreased, indicating that increasing the UV irradiation time enhances the concentration of oxygen vacancies. In MoOX, oxygen vacancies function as shallow-level donors, boosting carrier concentration and serving as the source of conductivity in the thin films [44,45]. The conductivity of MoOX and UV-MoOX films is shown in Figure 2c,d. The conductivity of MoOX was 4.782 × 10−4 S/m, whereas that of UV-MoOX was 2.124 × 10−3 S/m, which is almost an order of magnitude higher than that of MoOX. The improvement in UV-MoOX conductivity is attributed to the increased carrier concentration induced by oxygen vacancies. The detailed calculation data are shown in Figure S5, Supporting Information. In addition, Figure 2e shows that the WF values of MoOX and UV-MoOX obtained from UPS spectra are 5.10 eV and 5.05 eV, respectively. The WF of UV-MoOX fell by 0.05 eV compared to that of MoOX, which was the reason for the decrease in Voc. Additionally, MoOX treated by UV irradiation for 120 min exhibited a lower WF (Figure S6, Supporting Information). The UV-vis transmittance spectra of MoOX and UV-MoOX films are presented in Figure 2f. UV-MoOX exhibited lower transmittance in the 400–1200 nm range, attributed to free carrier absorption induced by oxygen vacancies [46]. The Eg of MoOX and UV-MoOX films was determined by Tauc’s equation. The Eg values were found to be 3.70 and 3.66 eV, respectively, as shown in the inset of Figure 2f. UV-MoOX shows almost the same Eg as that of MoOX, at only 0.04 eV lower. In addition, we tested the transmittance and absorption of MoOX with different irradiation times. The transmittance of MoOX treated with UV irradiation was lower than that of untreated MoOX, but it remained almost unchanged with different irradiation times. Additionally, there was no significant change in Eg (Figure S6, Supporting Information). In conclusion, the UV-MoOX film exhibits excellent properties when utilized as an HTL, with both high conductivity and an appropriate WF.

Figure 2.

The physical characterization of the MoOX and UV-MoOX films. (a,b) The Mo 3d XPS spectra of MoOX and UV-MoOX. (c,d) The conductivities of MoOX and UV-MoOX films are extracted by I–V curves with different contact area. (e) WF of MoOX and UV-MoOX films from UPS spectra. (f) UV-vis absorption spectra and transmittance of MoOX and UV-MoOX films. The inset showed the variation in (αhν)2 with the photon energy hν.

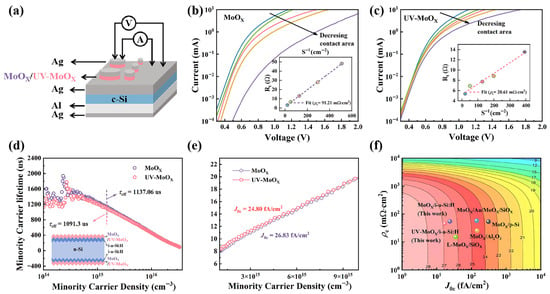

In order to evaluate the hole selectivity of the HSCs, the electrical contact performance of n-Si solar cells modified with MoOX and UV-MoOX was measured. The Expanded Cox and Streak method (ECSM) was utilized to extract the ρc of n-Si/i-a-Si:H/MoOX and n-Si/i-a-Si:H/UV-MoOX devices, as shown in Figure 3a. As shown in Figure 3b,c, the colored lines are the dark I–V curves of the ECSM disks with different contact areas. The inset in Figure 3b,c shows the total series resistance (Rt) from different disks, plotted against an inverse area (S−1). The ρc value of n-Si/i-a-Si:H/UV-MoOX (20.61 mΩ·cm2) demonstrated a significant reduction compared to n-Si/i-a-Si:H/MoOX (91.21 mΩ·cm2). UV-MoOX produced more oxygen vacancies, which increased the carrier concentration and achieved better contact performance. The low ρc values of devices using UV-MoOX as the HTL are highly recommended for achieving high FF and PCE for c-Si solar cells. A symmetric structure, shown in the inset of Figure 3d, was used to characterize the minority carrier lifetime (τeff) for the HTL, based on MoOX and UV-MoOX using the quasi-steady-state-photoconductance (QSSPC) method. At an injection level of 1.5 × 1015 cm−3, the τeff value of the MoOX-based device was 1137.06 μs. Replacing the MoOX layer with a UV-MoOX layer results in a similar τeff of 1091.3 μs, indicating that MoOX and UV-MoOX possess comparable field passivation ability. It is further demonstrated that a slight decrease in the WF hardly weakens the field passivation effect of the UV-MoOX layer. Meanwhile, the J0c was extracted from the τeff measurement, representing the flux of non-collected charge carriers to the contact. It is noteworthy that the wafer passivated solely with the i-a-Si:H layer also exhibiting excellent surface passivation performance, with an effective carrier lifetime reaching 1.12 ms (Figure S7): a level comparable to that observed in devices with deposited MoOX or UV-MoOX. This result confirms that the prepared 8 nm-thick i-a-Si:H film provides high-quality interface passivation. Furthermore, it indicates that subsequent processing steps, including deposition and ultraviolet treatment, introduced almost no adverse effects on the initial passivation quality. Figure 3e shows the Auger-corrected inverse effective lifetime (1/τcorr) as a function of minority carrier concentration, where 1/τcorr = 1/τeff − 1/τAuger [47]. The specific calculation process is described in detail in Section 2. The J0c value of the n-Si/i-a-Si:H/MoOX contact was approximately 24.80 fA/cm2, while n-Si/i-a-Si:H/UV-MoOX has a J0c value of 26.83 fA/cm2. The results show that the presence of more defects (vacancy oxygen) in UV-MoOX contacts leads to an increase in carrier recombination and J0c. In summary, although the replacement of the MoOX layer with a UV-MoOX layer leads to a slight increase in the J0c, it greatly reduces the ρc, which improves the carrier selectivity. In addition, a low ρc most likely suggests a high FF [48]. Figure 3f plots the ideal PCE as a function of ρc and J0c for MoOX and UV-MoOX contacts, as well as the ρc and J0c values from previous works. First, compared with other passivation layers (SiOX or Al2O3), i-a-Si:H exhibits a better passivation effect, reducing carrier recombination, and thus resulting in a smaller J0c. Furthermore, UV-MoOX achieves a lower ρc while maintaining a small J0c. Due to its excellent carrier selectivity, UV-MoOX has as great potential as an HTL.

Figure 3.

Evaluation of the carrier selectivity of i-a-Si:H/MoOX and i-a-Si:H/UV-MoOX contacts. (a) Schematic diagram of the test structure of ρc. (b,c) Experimental measurements of ρc by ECSM for MoOX and UV-MoOX as HTL. The inset showed the total series resistances (Rt) from different contact area plotted against inverse area (1 S−1). (d) Injection level-dependent minority carrier lifetime, where the τeff at a Δn of 1.5 × 1015 cm−3. The inset: the passivated sample with a symmetrical structure for τeff measurement. (e) The J0c of i-a-Si:H/MoOX and i-a-Si:H/UV-MoOX contacts are extracted by 1/τcorr of n-Si passivated by symmetric structure. (f) Plot of ideal PCE as a function of contact resistivity ρc and recombination current density J0c for different HSCs [33,36,49,50].

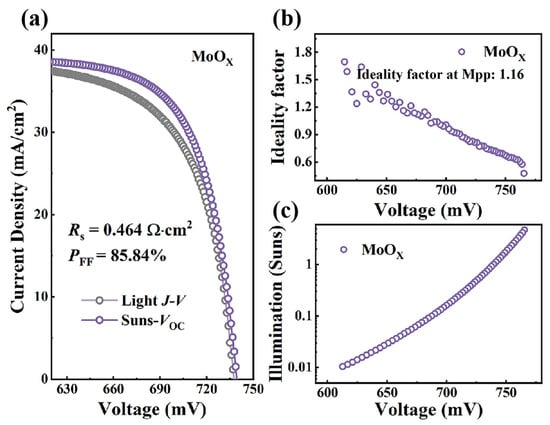

To explore the main contribution to the improvement in FF, Suns-Voc measurements of solar cells with MoOX and UV-MoOX were performed. The Suns-Voc pseudo-J–V curve, constructed from Voc measurements at different incident light intensities (Suns), is unaffected by the voltage drop due to series resistance (Rs) [51]. The experimental curves include the real J–V curve (purple-colored curve) and the pseudo-J–V curve obtained by a Suns-Voc measurement (pink-colored curve). By comparing the real J–V curves and pseudo-J–V curves in Figure 4a and Figure 5a, the device with UV-MoOX demonstrates a significantly reduced Rs of 0.434 Ω·cm2 compared to the MoOX-based device, with a value of 0.464 Ω·cm2, indicating that the UV-MoOX device exhibits lower resistance loss. Pseudo-FF (pFF: FF excluding Rs power loss) values of 85.84% and 86.84% are extracted from the pseudo-J–V curves of MoOX and UV-MoOX solar cells. Compared with the FF, the pFF of MoOX and UV-MoOX solar cells increase by 4.22% and 2.02%, respectively, which also indicates the variation trend of Rs. Next, to evaluate the impact of additional recombination pathways in the different cells, the ideality factor was calculated from the Suns-Voc data. The ideality factors of MoOX and UV-MoOX devices from the Suns-Voc measurement are shown in Figure 4b and Figure 5b. Typically, the ideality factor ranges from one to two for real devices. A value of n > 1 indicates that traps are involved in the carrier recombination mechanism in solar cells [52,53]. In contrast, when the value of n < 1, it may be attributed to the enhanced Auger recombination mechanism [54]. Thus, the ideality factor reflects the impact of traps on carrier recombination within photovoltaic devices. The ideality factor around the MPP (V = 664 mV) for the MoOX cells is approximately 1.16. Correspondingly, the ideality factor of the UV-MoOX device at the MPP (V = 660 mV) is similar to that of the MoOX device, with a value of 1.22. The slight difference in the ideality factor at the MPP indicates that the UV-MoOX device exhibits more carrier recombination; however, the discrepancy is negligible, which is consistent with the previous analysis of J0c. In addition, Figure 4c and Figure 5c show a transition from a low to high injection level, as the voltage shifts from the low-voltage to the high-voltage region. Both the MoOX and UV-MoOX devices exhibit a decrease in the ideality factor in the high-voltage region. This is due to the increasing role of Auger recombination in the high-voltage region.

Figure 4.

Electrical performance of solar cells with MoOX as HTL. (a) Experimental J–V curves and the Suns-Voc curves for the MoOX cell. The pseudo-J–V curves are constructed by a Voc-Jsc (Suns) plot at different intensities. The illumination intensity is monitored by a calibrated reference cell. (b) Ideality factor calculated from the Suns-Voc curve for the solar cell with MoOX. (c) Illumination–voltage curve of solar cells with MoOX.

Figure 5.

Electrical performance of solar cells with UV-MoOX as HTL. (a) Experimental J–V curves and the Suns-Voc curves for the UV-MoOX cell. The pseudo-J–V curves are constructed by a Voc-Jsc (Suns) plot at different intensities. The illumination intensity is monitored by a calibrated reference cell. (b) Ideality factor calculated from the Suns-Voc curve for the solar cell with UV-MoOX. (c) Illumination–voltage curve of solar cells with UV-MoOX.

To further validate the reliability of our results, we have now supplemented the study with additional data from devices subjected to 180 °C thermal annealing (see Figure S8). Minority carrier lifetime test samples with a MoOX/i-a-Si:H/n-Si/i-a-Si:H/MoOX symmetric structure were prepared and annealed at 180 °C for 10 min in a nitrogen atmosphere. The measured minority carrier lifetimes were 1091.3 μs for the as-processed sample and 1148.42 μs for the annealed sample, revealing nearly identical performance between the two. This result confirms that the UV treatment employed in this work caused only minimal damage to the Si–HX bonds.

4. Conclusions

In summary, we demonstrated that UV irradiation enables the modulation of oxygen vacancy density in MoOX films to improve the electrical performance of c-Si solar cells. At a UV treatment time of 60 min, the MoOX film exhibits both a relatively high work function of 5.05 eV and high conductivity of 2.124 × 10−3 S/m, which effectively balances the influence of film properties on Voc and FF. Additionally, UV-MoOX films still have a comparable τeff to MoOX films, indicating that UV-MoOX provides a field passivation effect that is similar to that of MoOX. The key improvement lies in the significant reduction in the ρc of UV-MoOX compared to MoOX. A ρc of 20.61 mΩ·cm2 indicates that UV-MoOX films possess superior contact characteristics, facilitating the selective transport of carriers. Further analysis comparing the J–V curve and the pseudo-light-J–V curve from Suns-Voc measurements demonstrates that UV-MoOX has a smaller Rs of 0.434 Ω·cm2 and an excellent pFF of 86.84%. These advantages contribute to the enhanced performance of solar cells employing UV-MoOX as the HTL, as evidenced by the state-of-the-art PCE of 24.15%. This work lays the foundation for attaining the highest PCE in c-Si solar cells using UV-MoOX as the HTLs. Furthermore, the successful application of UV-MoOX in c-Si solar cells provides valuable new insights into the controllable modulation of properties in high-WF TMOs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ma18225167/s1. Figure S1: Fabrication flowchart of a crystalline silicon solar cell with UV-MoOX HTL; Figure S2: Cross-sectional AC-TEM images of the n-Si/a-Si:H(i)/UV-MoOX/Ag, i-a-Si:H ~8 nm, MoOx ~7 nm, Ag ~200 nm; Figure S3: J-V parameters of devices with different UV irradiation time (0 min, 30 min, 60 min and 120 min); Figure S4: (a) The XPS spectra of MoOX film with different UV irradiation time (0 min, 60 min and 120 min), Where MoOX and UV-MoOX represent 0 min and 60 min, respectively. (b) The Mo 3d XPS spectra of MoOX film with 120 min UV irradiation. (c) O/Mo ratios of MoOX film with different UV irradiation time (0 min, 60 min and 120 min); Figure S5: Plots of total resistance (Rt) versus 1/S (fitted by dashed curves) of (a) p-Si/Ag/MoOX/Ag and b) p-Si/Ag/UV-MoOX/Ag structures; Figure S6: (a) UPS spectra of MoOX film with 120 min UV irradiation. (b) UV-vis absorption spectra and transmittance of MoOX film with 120 min UV irradiation. The inset showed the variation of (αhν)2 with the photon energy hν; Figure S7: Injection level-dependent minority carrier lifetime with i-a-Si:H/n-Si/i-a-Si:H structures, where the τeff at a Δn of 1.5 × 1015 cm−3; Figure S8: Injection level-dependent minority carrier lifetime with annealed UV-MoOX/i-a-Si:H/n-Si/i-a-Si:H/UV-MoOX structures, where the τeff at a Δn of 1.5 × 1015 cm−3; Table S1: J-V parameters of solar cells fabricated with continuous deposition and interrupted deposition.; Table S2: Input parameters of Quokka2 simulation for MoOX cell and UV-MoOX cell. Note S1: Expanded Cox-Strack Method. References [26,55,56,57] are cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Y., W.L. and J.L.; methodology, L.Y., W.L. and S.C.; software, L.Y., T.L., and D.Y.; validation, Y.W. and J.Z.; investigation, L.Y. and W.L.; data curation, L.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, L.Y.; writing—review and editing, L.Y., Q.K., and W.L.; supervision, H.Y., Q.K., and Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant no. 2022YFB4200202), the State Key Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 62034001), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 52303218).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; Yang, G.; Mazzarella, L.; Procel-Moya, P.; Tamboli, A.C.; Weber, K.; Boccard, M.; Isabella, O.; et al. High-Efficiency Silicon Heterojunction Solar Cells: Materials, Devices and Applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2020, 142, 100579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.T.; Li, L.; Yang, X.; Lu, L.; Li, D. Dopant-free passivating contacts for crystalline silicon solar cells: Progress and prospects. EcoMat 2022, 5, e12292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Xu, X.; Li, J.; Lu, W.; Yuan, D.; Liu, T.; Yan, H.; Kang, Q.; Zhang, Y. Transition metal oxide as hole transport layer for crystalline silicon solar cells: Progress and prospects. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2025, 290, 113682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Yang, M.; Ru, X.; Wang, G.; Yin, S.; Peng, F.; Hong, C.; Qu, M.; Lu, J.; Fang, L.; et al. Silicon heterojunction solar cells with up to 26.81% efficiency achieved by electrically optimized nanocrystalline-silicon hole contact layers. Nat. Energy 2023, 8, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longi Green Energy Technology Co., Ltd. Longi Sets New World Record with 27.81% Conversion Efficiency for Its Heterojunction Back-Contact Cells. Available online: https://www.longi.com/cn/news/isfh-hibc-conversion-efficiency/ (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Yang, X.; Bi, Q.; Ali, H.; Davis, K.; Schoenfeld, W.V.; Weber, K. High-Performance TiO2-Based Electron-Selective Contacts for Crystalline Silicon Solar Cells. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 5891–5897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, Z.C.; Descoeudres, A.; Barraud, L.; Fernandez, F.Z.; Seif, J.P.; De Wolf, S.; Ballif, C. Current Losses at the Front of Silicon Heterojunction Solar Cells. IEEE J. Photovolt. 2012, 2, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, A.; Müller, R.; Benick, J.; Feldmann, F.; Steinhauser, B.; Reichel, C.; Fell, A.; Bivour, M.; Hermle, M.; Glunz, S.W. Design rules for high-efficiency both-sides-contacted silicon solar cells with balanced charge carrier transport and recombination losses. Nat. Energy 2021, 6, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurgin, J.; Bykov, A.Y.; Zayats, A.V. Hot-electron dynamics in plasmonic nanostructures: Fundamentals, applications and overlooked aspects. eLight 2024, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, J.; Zheng, P.; Jeangros, Q.; Tosun, M.; Hettick, M.; Sutter-Fella, C.M.; Wan, Y.; Allen, T.; Yan, D.; Macdonald, D.; et al. Lithium Fluoride Based Electron Contacts for High Efficiency n-Type Crystalline Silicon Solar Cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2016, 6, 1600241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Xing, C.; Xu, D.; Lou, X.; Wang, X.; Li, K.; Li, W.; Mao, J.; Zheng, P.; Zhang, X.; et al. Aluminum Halide-Based Electron-Selective Passivating Contacts for Crystalline Silicon Solar Cells. Small 2024, 20, 2310352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, J.; Hettick, M.; Geissbühler, J.; Ong, A.J.; Allen, T.; Sutter-Fella, C.M.; Chen, T.; Ota, H.; Schaler, E.W.; De Wolf, S.; et al. Efficient silicon solar cells with dopant-free asymmetric heterocontacts. Nat. Energy 2016, 1, 15031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchikova, Y.; Nazarovets, S.; Konuhova, M.; Popov, A.I. Binary Oxide Ceramics (TiO2, ZnO, Al2O3, SiO2, CeO2, Fe2O3, and WO3) for Solar Cell Applications: A Comparative and Bibliometric Analysis. Ceramics 2025, 8, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusuma, J.; Balakrishna, R.G. Ceramic grains: Highly promising hole transport material for solid state QDSSC. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2020, 209, 110445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielke, D.; Niehaves, C.; Lövenich, W.; Elschner, A.; Hörteis, M.; Schmidt, J. Organic-silicon Solar Cells Exceeding 20% Efficiency. Energy Procedia 2015, 77, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ashouri, A.; Magomedov, A.; Roß, M.; Jošt, M.; Talaikis, M.; Chistiakova, G.; Bertram, T.; Márquez, J.A.; Köhnen, E.; Kasparavičius, E.; et al. Conformal monolayer contacts with lossless interfaces for perovskite single junction and monolithic tandem solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 3356–3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, X.; Bi, Q.; Diao, Y.; Wu, Z.; Gao, K.; Wang, X.; Xu, D.; Wang, J.; Lin, H.; Xie, J.; et al. High-efficiency organic–silicon heterojunction solar cells with high work function PEDOT:F-based hole-selective contacts. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 7777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dréon, J.; Jeangros, Q.; Cattin, J.; Haschke, J.; Antognini, L.; Ballif, C.; Boccard, M. 23.5%-efficient silicon heterojunction silicon solar cell using molybdenum oxide as hole-selective contact. Nano Energy 2020, 70, 104495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissbühler, J.; Werner, J.; Martin de Nicolas, S.; Barraud, L.; Hessler-Wyser, A.; Despeisse, M.; Nicolay, S.; Tomasi, A.; Niesen, B.; De Wolf, S.; et al. 22.5% efficient silicon heterojunction solar cell with molybdenum oxide hole collector. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015, 107, 081601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, A.; Nong, Q.; Shang, K.; Sun, Y.; He, J.; Gao, P. In-Situ Hydrogenation Strategies on Vanadium Oxide Hole-Selective Contact for Efficiency Crystalline Silicon Solar Cells. Small 2025, 21, 2410492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Ren, P.; Zhao, D.; Li, S.; Wang, J.; Zhou, H.; Liu, W.; Zeng, Y.; Yu, X.; Wang, P.; et al. Solution-processed tungsten oxide with Ta5+ doping enhances the hole selective transport for crystalline silicon solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. C 2024, 12, 17925–17934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhai, Z.; Li, L. Rapid Fabrication of Tungsten Oxide-Based Electrochromic Devices through Femtosecond Laser Processing. Micromachines 2024, 15, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldirham, S.H.; Helal, A.; Shkir, M.; Sayed, M.A.; Ali, A.M. Enhancement Study of the Photoactivity of TiO2 Photocatalysts during the Increase of the WO3 Ratio in the Presence of Ag Metal. Catalysts 2024, 14, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Wu, W.; Liu, Z.; Qiu, K.; Cai, L.; Yao, Z.; Ai, B.; Liang, Z.; Shen, H. Chromium Trioxide Hole-Selective Heterocontacts for Silicon Solar Cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 13645–13651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, M.T.; Chai, L.; Helander, M.G.; Tang, W.M.; Lu, Z.H. Transition Metal Oxide Work Functions: The Influence of Cation Oxidation State and Oxygen Vacancies. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012, 22, 4557–4568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Pan, T.; Wang, J.; Cao, S.; Lin, Y.; Hoex, B.; Ma, Z.; Lu, L.; Yang, L.; Sun, B.; et al. Bilayer MoOX/CrOX Passivating Contact Targeting Highly Stable Silicon Heterojunction Solar Cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 36778–36786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, J.; Wan, Y.; Cui, J.; Lim, S.; Song, N.; Lennon, A. Solution-processed molybdenum oxide for hole-selective contacts on crystalline silicon solar cells. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 423, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Procel, P.; Alcañiz, A.; Yan, J.; Tichelaar, F.; Özkol, E.; Zhao, Y.; Han, C.; Yang, G.; Yao, Z.; et al. Achieving 23.83% conversion efficiency in silicon heterojunction solar cell with ultra-thin MoOx hole collector layer via tailoring (i)a-Si:H/MoOx interface. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2022, 31, 1245–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Chen, Y.; Cui, Y.; Liu, D.; Xu, B.; Hou, J. Over 100-nm-Thick MoOx Films with Superior Hole Collection and Transport Properties for Organic Solar Cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1800698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayogi, S.; Cahyono, Y.; Darminto. Fabrication of solar cells based on a-Si: H layer of intrinsic double (P-ix-iy-N) with PECVD and Efficiency analysis. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1951, 012015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, T.; McNab, S.; Bonilla, R.S.; Sai, H. Full-Area Passivating Hole Contact in Silicon Solar Cells Enabled by a TiOx/Metal Bilayer. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 5, 12782–12789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Bi, Q.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Xing, C.; Li, K.; Xu, D.; Su, Z.; Zhang, C.; Yu, J.; et al. Progress and Future Prospects of Wide-Bandgap Metal-Compound-Based Passivating Contacts for Silicon Solar Cells. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2200344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Kang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, H.; Lu, W.; Tao, X.; Zhang, S.T.; Chen, X.; et al. Low Oxygen Content MoOx and SiOx Tunnel Layer Based Heterocontacts for Efficient and Stable Crystalline Silicon Solar Cells Approaching 22% Efficiency. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 34, 2310619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Zhan, Y.; Xu, X.; Xie, Y. Experimental study on an evaporation process to deposit MoO2 microflakes. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2017, 687, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Du, G.; Lin, Y.; Zhou, X.; Gu, Z.; Lu, L.; Liu, W.; Huang, J.; Wang, J.; Yang, L.; et al. NiOx/MoOx bilayer as an efficient hole-selective contact in crystalline silicon solar cells. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2021, 2, 100684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Kang, Q.; Li, J.; Xu, X.; Yuan, D.; Yang, L.; Liu, S.; Liu, T.; Yan, H.; Wu, Z.; et al. MoOX/Au/MoOX-Based Composite Heterocontacts for Crystalline Silicon Solar Cells Achieving 22.0% Efficiency. Small Struct. 2025, 6, 2400559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, H.; Wang, Z.; Chen, L.; Wu, T.; Pang, Y.; Cai, L.; He, J.; Peng, S.; Shen, H.; et al. Dual Functional Dopant-Free Contacts with Titanium Protecting Layer: Boosting Stability while Balancing Electron Transport and Recombination Losses. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2202240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, M.T.S.K.A.; Melskens, J.; Weeber, A. Effects of a post deposition anneal on a tunneling Al2O3 interlayer for thermally stable MoOx hole selective contacts. AIP Conf. Proc. 2022, 2487, 020001. [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia, C.; Yin, X.; Zheng, M.; Sharp, I.D.; Chen, T.; McDonnell, S.; Azcatl, A.; Carraro, C.; Ma, B.; Maboudian, R.; et al. Hole Selective MoOx Contact for Silicon Solar Cells. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 967–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Wang, R.; Liu, R.; Wu, C.; Zhong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Han, Y.; Xia, Z.; Zou, Y.; et al. Investigation of MoOx/n-Si strong inversion layer interfaces via dopant-free heterocontact. Phys. Status Solidi Rapid Res. Lett. 2017, 11, 1700107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kuhaili, M.F.; Mekki, M.B. Laser-induced photocoloration in molybdenum oxide thin films. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 885, 161043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJournett, T.J.; Spicer, J.B. The influence of oxygen on the microstructural, optical and photochromic properties of polymer-matrix, tungsten-oxide nanocomposite films. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2014, 120, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Li, J.; Lin, Y.; Pan, T.; Du, G.; Zhang, J.; Yang, L.; Chen, X.; Lu, L.; Min, N.; et al. Interfacial Behavior and Stability Analysis of p-Type Crystalline Silicon Solar Cells Based on Hole-Selective MoOX/Metal Contacts. Sol. RRL 2019, 3, 1900274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuzheng Guo, J.R. Origin of the high work function and high conductivity of MoO3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 105, 222110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, R.A.; Essig, S.; De Wolf, S.; Ramanathan, B.G.; Loper, P.; Ballif, C.; Varadharajaperumal, M. Hole-Collection Mechanism in Passivating Metal-Oxide Contacts on Si Solar Cells: Insights from Numerical Simulations. IEEE J. Photovolt. 2018, 8, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Cao, S.; Lu, L.; Du, G.; Lin, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, L.; Zhu, W.; Li, D. Post-annealing Effect on Optical and Electronic Properties of Thermally Evaporated MoOX Thin Films as Hole-Selective Contacts for p-Si Solar Cells. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Du, G.; Zhou, X.; Lin, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Gao, X.; Lu, L.; Li, G.; Zhang, W.; Feng, Q.; et al. Interfacial Engineering of Cu2O Passivating Contact for Efficient Crystalline Silicon Solar Cells with an Al2O3 Passivation Layer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 28415–28423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.G.; Bullock, J.; Yang, X.; Javey, A.; De Wolf, S. Passivating contacts for crystalline silicon solar cells. Nat. Energy 2019, 4, 914–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, G.; Feit, C.; Gao, Z.; Banerjee, P.; Jurca, T.; Davis, K.O. Improving the Passivation of Molybdenum Oxide Hole-Selective Contacts with 1 nm Hydrogenated Aluminum Oxide Films for Silicon Solar Cells. Phys. Status Solidi (a) 2020, 217, 2000093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, H.; Es, F.; Zolfaghari Borra, M.; Semiz, E.; Kökbudak, G.; Orhan, E.; Turan, R. On the application of hole-selective MoOx as full-area rear contact for industrial scale p-type c-Si solar cells. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2020, 29, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinton, R.A. Andres Cuevas, A quasi-steady-state open-circuit voltage method for solar cell characterization. In Proceedings of the 16th European Photovoltaic Solar Energy Conference, Glasgow, UK, 1–5 May 2000; Volume 25, pp. 1152–1155. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, L.; Yi, H.; Xu, C.; Upama, M.B.; Mahmud, M.A.; Wang, D.; Shabab, F.H.; Uddin, A. Relationship Between the Diode Ideality Factor and the Carrier Recombination Resistance in Organic Solar Cells. IEEE J. Photovolt. 2018, 8, 1701–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchartz, T.; Nelson, J. Meaning of reaction orders in polymer:fullerene solar cells. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 86, 165201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Wang, G.; Su, Q.; Han, C.; Xue, C.; Yin, S.; Fang, L.; Xu, X.; Gao, P. Unveiling the mechanism of attaining high fill factor in silicon solar cells. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2024, 32, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Lin, H.; Liu, Z.; Wu, T.; Pang, Y.; Gao, P.; Shen, W. Realization of a General Method for Extracting Specific Contact Resistance of Silicon-Based Dopant-Free Heterojunctions. Sol. RRL 2021, 6, 2100394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Lin, H.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Liao, M.; Zeng, Y.; Gao, P.; Yan, B.; et al. An Expanded Cox and Strack Method for Precise Extraction of Specific Contact Resistance of Transition Metal Oxide/n-Silicon Heterojunction. IEEE J. Photovolt. 2019, 9, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, S.K.; Cheung, N.W. Extraction of Schottky diode parameters from forward current-voltage characteristics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1986, 49, 85–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).