Abstract

The recycling of NdFeB magnets is essential to reduce reliance on critical rare earth elements and mitigate the environmental burden of virgin magnet production. Hydrogen Processing of Magnetic Scrap (HPMS) offers an efficient method to extract magnet powders from end-of-life (EOL) products, yet oxidation and microstructural degradation during powder preparation limit the magnetic performance of recycled magnets. In this work, rapid Radiation-Assisted Sintering (RAS) was systematically evaluated for the first time as a consolidation route for HPMS-derived powders. Magnets prepared via RAS exhibited performance comparable to those obtained by conventional sintering. When oxygen uptake during milling was prevented, the addition of 1 wt.% NdH3 to the already oxygen-burdened recycled powder improved the intrinsic coercivity and squareness of the demagnetization curve. The best-performing samples achieved Br = 1.18 T, (BH)max = 263 kJ/m3, and Hci = 742 kA/m at 100 °C, surpassing the properties of the original EOL magnets. Furthermore, the study revealed that, when the HPMS powder fragments preferentially break along grain boundaries, the resulting near-equilibrium powder particles exhibit limited growth, thereby restraining grain coarsening. These findings highlight the strong potential of RAS for more energy-efficient magnet-to-magnet recycling and provide new insight into optimizing HPMS powder processing to achieve enhanced magnetic performance.

1. Introduction

Permanent magnets based on neodymium–iron–boron (NdFeB) alloys are indispensable components in energy-efficient technologies, including electric vehicles, wind turbines, and a wide array of electronic devices [1,2,3,4]. Their superior magnetic performance makes them critical for achieving sustainability targets in energy conversion and storage. However, the production of NdFeB magnets is heavily dependent on rare –earth elements (REEs), which are subject to significant supply risks [5,6]. More than 85% of the global REE supply is currently sourced from China, often through energy- and chemically intensive processing routes with notable environmental and geopolitical implications [7]. In response to these vulnerabilities, the European Union has formally listed REEs as critical raw materials and introduced the 2024 Critical Raw Materials Act [5], emphasizing the importance of recycling and circular material strategies for these strategic elements.

Recycling of NdFeB magnets, particularly through closed-loop magnet-to-magnet routes, represents a promising solution to reduce both environmental impact and supply chain dependency. Recent life cycle assessments have shown that magnet-to-magnet recycling, i.e., crushing end-of-life (EOL) magnets into powders, followed by re-sintering, can reduce energy consumption by more than 45% compared to virgin magnet production [8]. Among the emerging recycling methods, Hydrogen Processing of Magnetic Scrap (HPMS), which was developed by the University of Birmingham [8,9,10,11], has proven to be an efficient and selective approach for extracting magnet powders from EOL products without extensive mechanical or chemical processing [11]. However, achieving magnetic properties in recycled magnets equivalent to virgin magnets remains a central challenge, particularly due to oxidation and suboptimal microstructures of HPMS-type powders, and limitations associated with traditional sintering processes. EOL magnets typically exhibit higher oxygen contents, ranging from 2000 to 5000 ppm, in contrast to the 300 to 400 ppm observed in newly cast magnets [12]. This increased oxygen content leads to the formation of high-melting-point oxides [12] in the RE-rich phase, primarily located at the grain boundaries [13]. These oxides subsequently inhibit the necessary melting of the RE-rich phase and therefore proper densification during sintering [12,14], resulting in severely degraded intrinsic coercivity [13].

Conventional sintering, i.e., the traditional method for consolidating magnet powders, is energy-intensive and time-consuming [12]. It also carries a high risk of grain coarsening and phase degradation, especially when applied to recycled powders with pre-existing structural or chemical inhomogeneities [13]. These challenges hinder the full realization of HPMS as a green scalable recycling pathway.

Radiation-Assisted Sintering (RAS) [12] is a novel rapid consolidation technique with strong potential to address these limitations. By employing intense thermal radiation to enable high heating rates and short dwell times, RAS minimizes processing time while achieving full densification. Recent work by Tomše et al. [12] demonstrated that RAS can produce fully dense NdFeB magnets from standard micron-sized powders within minutes, offering energy efficiency at least tenfold greater than slow conventional sintering methods at the lab scale [12,14].

To date, RAS has not been systematically evaluated for its applicability to recycled NdFeB powders. In this study, we examined the influence of RAS-specific conditions on the magnetic performance and microstructural evolution of magnets prepared from jet-milled HPMS powders. Both RAS and conventional sintering fully restored the performance of the original EOL magnets when oxygen contamination in the recycled material was compensated by adding 1 wt.% NdH3 and additional oxygen uptake during milling was avoided. Furthermore, the investigation showed that, when coarse HPMS material is fragmented preferentially by intergranular cracking, i.e., along grain boundaries, grain growth during re-sintering is suppressed, yielding a grain growth factor of approximately 1.2.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Powder Feedstocks and Green Compact Preparation

Wind turbine end-of-life (EOL) NdFeB permanent magnets were sourced through STENA Recycling, Gothenburg, Sweden. They were processed via Hydrogen Processing of Magnetic Scrap (HPMS) [9] in pure hydrogen atmosphere at 3 bar pressure. The reaction was terminated when no more drop in hydrogen pressure due to absorption was observed. Two powder feedstocks with reduced particle size were prepared from the same EOL material by milling the coarse HPMS material using two different jet mills.

To prepare the first powder feedstock (JM3X), the HPMS powder was milled using a laboratory-scale MC DecJet® 50 jet mill (Dec Group Dietrich Engineering Consultants, Ecublens, Switzerland). The DecJet® 50 jet mill was placed inside an argon-atmosphere glovebox. The HPMS powder was not degassed before jet milling to preserve its brittleness. Milling conditions in argon processing gas employed venturi and grinding ring pressures of 7 and 5 bar, respectively. Initially, the material underwent several milling cycles (JM1X = 1 milling cycle, JM2X = 2 milling cycles, etc.). However, the final powder was prepared with three milling cycles as no further particle size reduction was achieved with additional milling.

The second powder feedstock (JMIndustrial) was produced using an industrial-scale spiral jet mill (LabPilot M-Jet 10 with an M Class 5 classifier, NETZSCH GmbH, Selb, Germany). The HPMS powder was milled in nitrogen gas under 6.8 bar of pressure. A classifier was used to control the final particle size. The classifier speed was set to 5000 rpm.

The powders were magnetically aligned under a 6 T pulse field and compacted into cylindrical green compacts, with a diameter of ~17 mm and a height of ~15 mm, using cold isostatic pressing (CIP RP 2000 QC/LC, Recherches & Réalisations REMY SAS, Montauban, France) in a silicon mold contained in a vacuum/argon-sealed bag at 800 MPa. Selected samples were prepared with the addition of 1 wt.% of jet-milled NdH3 (Dv50 = 3.3 µm). For powder blends, the milled NdFeB and NdH3 powders were mixed with mortar and pestle inside an argon glovebox until fully homogenized.

2.2. Conventional Sintering (CS), Radiation-Assisted Sintering (RAS), and Annealing

Fully dense sintered samples were prepared from the NdFeB powders and NdFeB/NdH3 powder blends using either conventional vacuum sintering (CS) or Radiation-Assisted Sintering (RAS) followed by post-sinter annealing. In all cases, the green compacts were loaded into the sintering furnace inertly in argon gas, and the systems were flushed three times with additional argon to ensure the complete removal of any oxygen trapped in the system.

CS was performed in a custom-built high vacuum furnace at 1∙10−5 mbar pressure using single-stage heating at 3 °C/min to 1100 °C with a dwell time (tDWELL) of 2 h. For CS, the samples were placed in an alumina crucible (boat-shaped) to ensure that they were located at the center of the heating zone.

RAS employed a modified spark-plasma sintering furnace (SPS-632LxEx, Dr. SINTER SPS Syntex Inc., Kawasaki, Japan) with dynamic vacuum conditions. A schematic illustration of the setup can be found in [12]. The green compacts were placed in a cylindrical graphite crucible electrically insulated at the bottom by graphite felt (Sigatherm GFA5, SGL Carbon GmbH, Wiesbaden, Germany) coated with boron nitride. The crucible dimensions were 38.4 mm inner diameter and 23.4 mm height, with a wall thickness of 4.2 mm. Under such noncontact conditions, the electric current flows through the crucible, which heats up and acts as a heat source, i.e., radiator. The heating was current-controlled from room temperature to 570 °C, and temperature-controlled from 570 °C to the sintering temperature (TSINT) of 1100 °C using a pyrometer. For the first powder feedstock (JM3X), the heating rate was 25 °C/min, and the dwell time (tDWELL) at TSINT was 5 min, following the procedure published previously [12]. For the second powder feedstock (JMIndustrial), tDWELL was increased to 30 min to achieve full density due to higher oxygen content than in the JM3X powder. The NdFeB powders contained interstitial and bonded hydrogen from the HPMS process, which was progressively desorbed during the heating stage up to ~600 °C [15]. Chamber pressures during the heating ranged initially from approximately 0.03 mbar to 1 mbar on average with a maximum of 7 mbar (desorption of hydrogen). After sintering, natural cooling under vacuum occurred.

Single-stage post-sinter annealing was carried out for all samples in the custom-built vacuum furnace, heating samples at 5 °C/min to 520 °C (TANNEAL) with a tDWELL of 2 h, followed by natural cooling.

2.3. Characterization of Powders and Bulk Samples

Particle size distributions of the NdFeB jet-milled powders and NdH3 powder were measured using laser diffraction (HELOS/BR, Sympatec GmbH, Clausthal-Zellerfeld, Germany) with R1 (0.18–35 µm) and R3 (0.9–175 µm) lenses. All powders were oxidized before measurement and dispersed using the ASPIROS dry disperser with an applied pressure of 1 bar of compressed air. The results were analyzed using the Fraunhofer (FREE) method.

Chemical analysis of the EOL magnet was conducted via inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP–OES, iCAP 7400, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). ICP samples were digested in aqua regia containing 5% nitric acid using microwave-assisted digestion (MARS6, CEM Corporation, Matthews, NC, USA) at 200 °C, diluted, and analyzed against a custom-prepared tuning solution.

Magnetic properties of the EOL magnet and sintered samples were measured using a permeameter (EP2 Permagraph, Magnetphysik Dr. Steingroever GmbH, Cologne, Germany), with heated coils allowing for measurements up to 250 °C. Owing to the measurement apparatus and the high coercivity of the samples, demagnetization curves were obtained at 100 °C to achieve full demagnetization. The samples were heated by the coils of the permeameter, and, once the coils reached 100 °C, the samples were held for 5 min at this temperature to ensure that, due to the thermal lag, the sample’s core could reach the desired temperature. This temperature is also representative of the typical operating conditions of permanent magnet-based electric motors, providing insights into the actual performance of the recycled materials.

Bulk density was measured using Archimedes’ principle with silicon oil infiltration (Densitec, Exelia AG, Zürich, Switzerland). Oxygen contents were determined using the LECO ONH836 (LECO Corporation, St. Joseph, MI, USA) via hot gas extraction, infrared detection of CO, and calibration against certified reference materials.

Microstructural analysis utilized scanning electron microscope (FEG-SEM, JEOL JSM 7600F, JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) combined with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (INCA 350 EDS, Oxford Instruments, Abingdon, UK). Grain size analysis was performed on four bulk samples: an EOL reference magnet, two samples composed of JM3X jet-milled powder using RAS and CS, and a sample prepared from JMIndustrial powder using RAS. All sintered samples, except the EOL reference, contained 1 wt.% of NdH3. For each sample, three SEM micrographs were acquired at a magnification of 1000x at different positions of each polished and etched sample. The microstructures were etched for 2 min using a mixture of Cyphos 101 IL and HCl. In the SEM micrographs, the grains were manually traced (digitally) to create a binary outline mask, and the average grain diameter was determined using Feret’s diameter in ImageJ (Version 1.54g) [16,17], following the methodology outlined in [18].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. EOL Magnet Characterization

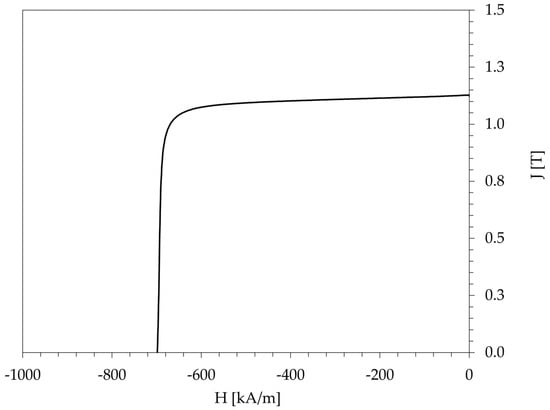

The EOL magnet was characterized before recycling to establish the baseline properties at the end of the life cycle. Its chemical composition, density, and key magnetic properties are compiled in Table 1. Chemical analysis using ICP–OES revealed a dysprosium content of approximately 4.2 wt.%, among other alloying elements. At 100 °C, the magnet exhibited a remanence (Br) of 1.13 T, an intrinsic coercivity (Hci) of 699 kA/m, and a maximum energy product ((BH)max) of 241 kJ/m3. The demagnetization curve obtained at 100 °C has a squareness factor, defined as Hk/Hci, where Hk is the knee point field at 0.9 Br and Hci is the intrinsic coercivity of 0.95. The curve is shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Chemical composition, density, and magnetic properties (measured with a permeameter at 100 °C) of the end-of-life NdFeB magnet: remanence (Br), intrinsic coercivity (Hci), maximum energy product ((BH)max), and the squareness factor of the demagnetization curve.

Figure 1.

Demagnetization curve (measured with a permeameter at 100 °C) for the end-of-life (EOL) magnet.

3.2. NdFeB Powder Feedstock Characterization

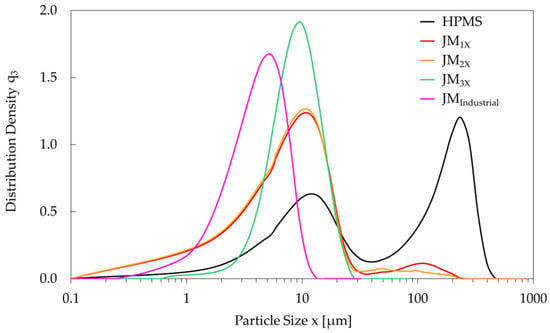

The oxygen content and particle size distribution for the HPMS and milled powders are listed in Table 2. The HPMS powder had an oxygen content of 0.47 wt.% and a Dv50 value of 71.9 µm. Three consecutive milling steps using a laboratory-scale MC DecJet® 50 jet mill (powder JM3X) reduced the DV50 to 8.9 µm. This value is slightly higher than the DV50 of the twice-milled powder JM2X (8.0 µm), which is attributed to the increased Dv10 value of the JM3X powder due to the removal of a fraction of small particles during the third milling cycle, which are filtered out in the cyclone separator of the jet mill. Moreover, the Dv90/10 ratio decreased from 9.6 (JM1X) to 9.0 (JM2X) and finally 3.6 (JM3X), revealing a narrow size distribution in the thrice-milled powder. This is also seen in the particle size distribution density curves shown in Figure 2. After the third jet-milling cycle (JM3X), the curve is significantly narrower due to the disappearance of the secondary peaks observed for powders JM1X and JM2X (reduction in Dv90) and the removal of small particles (increase in Dv10). The oxygen content initially increased from 0.47 wt.% (HPMS) to 0.56 wt.% (JM1X powder) and later decreased to 0.42 wt.% for the final JM3X powder. This reduction is in agreement with the removal of small particles of oxidized RE-rich phase, which is a common occurrence in inert atmosphere jet milling [19].

Table 2.

Oxygen content [wt.%] and laser-diffraction particle size distribution parameters Dv10, Dv50, and Dv90 [µm] with calculated Dv90/10 ratio for the HPMS material, powders prepared using a laboratory-scale MC DecJet® 50 jet mill with consecutive milling (JM1X, JM2X, and JM3X), and a powder prepared using an industrial-scale spiral jet mill LabPilot M-Jet 10 (JMIndustrial). Powders JM3X and JMIndustrial were used as feedstocks for new sintered magnets.

Figure 2.

Particle size distribution density (q3) curves for the HPMS powder (black) and consecutive milling stages (JM1X—red, JM2X—orange, and JM3X—green) for the laboratory-scale MC DecJet® 50 jet mill, showing how repeated milling narrows the particle size range. A curve for a powder milled on an industrial-scale jet mill (JMIndustrial—magenta) reveals a smaller average particle size.

The JMIndustrial powder, prepared using an industrial spiral jet mill LabPilot M-Jet 10, had a Dv50 value of 4.3 µm (see Table 2), approximately half that of the JM3X powder. This particle size reduction is also evident in Figure 2, where the particle size distribution density curve corresponding to JMIndustrial powder is shifted to the left relative to the JM3X powder. It is attributed to the difference in particle-on-particle collision impact during milling, evidencing superior efficiency of the industrial jet mill. Nevertheless, both powders have narrow size distributions with nearly identical Dv90/10 ratios (3.6 and 3.5 for JM3X and JMIndustrial, respectively; see Table 2), necessary to ensure a homogeneous microstructure in bulk sintered magnets.

The oxygen content in powders JM3X and JMIndustrial was significantly different. While a reduction in the oxygen content for the JM3X powder confirmed that jet milling inside an argon glovebox prevented additional oxygen uptake, the industrial jet mill did not offer the same protection against oxidation as the oxygen content increased to 0.59 wt.% upon milling. Considering its more favorable oxygen level, powder JM3X was used as a feedstock material for further sintering trials (Section 3.3).

The oxygen content of the JMIndustrial powder was found to be too high to achieve satisfactory magnetic performance in new magnets after re-sintering, and the material was used only to study the effect of particle size and shape on the grain-growth dynamics (Section 3.4).

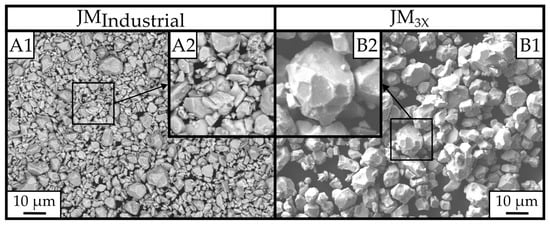

In Figure 3, the powder morphologies of the jet-milled powders are shown. The JMIndustrial powder morphology (Figure 3(A1)) is fine and contains fractured particles, typical for high-impact jet milling. Some larger particles on the order of ~10 µm appear to be more rounded and similar in size to the JM3X powder. In the laboratory-scale JM3X powder (Figure 3(B1)), on the other hand, the majority of grains show a rounded and faceted morphology, with particles significantly larger than in the JMIndustrial powder. Figure 3(B2) particularly highlights the faceted morphology of the particles.

Figure 3.

Powder morphology images by SEM microscopy at a magnification of 1000x. (A1) represents the finely milled JMIndustrial powder, and (B1) represents the JM3X laboratory-scale jet-milled powder. (A2) shows a magnified section, highlighting the fractured shape morphology of the powder, compared to the faceted and more rounded morphology of the larger JM3X powder shown in (B2).

3.3. Performance of Bulk Samples Prepared from JM3X Powder

Bulk samples were prepared from the JM3X jet-milled powder by Radiation-Assisted Sintering (RAS) and conventional sintering (CS), followed by post-sinter annealing. Due to the increased oxygen content of 0.42 wt.% in the powder feedstock compared to conventional NdFeB materials at <0.30 wt.% [20], two samples were prepared with the addition of 1 wt.% NdH3 to compensate for the loss of liquid phase.

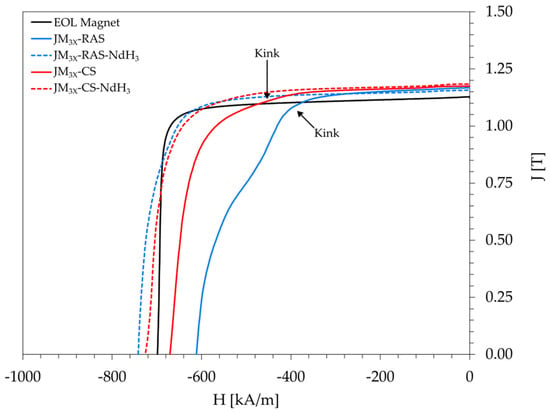

The magnetic properties, obtained at 100 °C, are listed in Table 3, and the correlating demagnetization curves for all the samples are shown in Figure 4. The measured densities of the samples prepared by RAS and CS range between 7.58 and 7.64 g/cm3, and the samples are considered fully dense.

Table 3.

Densities and magnetic properties (measured at 100 °C) for the EOL magnet and bulk samples prepared from the JM3X powder with or without addition of 1 wt.% NdH3 by RAS and CS, followed by post-sinter annealing.

Figure 4.

Demagnetization curves (measured at 100 °C) for bulk samples prepared from the JM3X powder by RAS or CS, followed by post-sinter annealing: EOL reference (solid black), JM3X-RAS sample without additive (solid blue), JM3X-RAS-NdH3 sample prepared with 1 wt.% NdH3 (dashed blue), JM3X-CS sample without additive (solid red), and JM3X-RAS-NdH3 sample prepared with 1 wt.% NdH3 (dashed red).

For the JM3X-RAS sample prepared without the additive, the remanence (Br) reached 1.17 T at 100 °C, slightly exceeding the EOL magnet’s value of 1.13 T. However, the squareness factor of its demagnetization curve, Hk/Hci, was only 0.68. The corresponding curve (Figure 4, solid blue curve) displayed a notable kink and was significantly less squared compared to the EOL magnet (solid black curve), with a squareness ratio of 0.95. The remanence of a conventionally sintered sample JM3X-CS prepared without the additive was 1.17 T, i.e., identical to RAS sample JM3X-RAS. On the other hand, the kink in its demagnetization curve (solid red curve) is notably less pronounced than the kink observed for sample JM3X-RAS. In turn, the squareness factor was improved from 0.68 (JM3X-RAS) to 0.78 (JM3X-CS).

For sample JM3X-RAS-NdH3, the addition of 1 wt.% NdH3 improved the curve’s shape (dashed blue curve) and increased its squareness factor to 0.86. Moreover, while the remanence remained almost unchanged at 1.16 T, the coercivity increased from 611 kA/m (no addition) to 742 kA/m. For sample JM3X-CS-NdH3, the NdH3 addition increased the coercivity from 671 kA/m (no addition) to 726 kA/m without reducing the remanence. In summary, the magnetic properties of samples prepared by RAS or CS with the addition of NdH3 are comparable. Their Br values (1.16 and 1.18 T), Hci values (742 and 726 kA/m), and (BH)max values (254 and 263 kJ/m3) exceeded the properties of the initial EOL magnet by ≈2–4% (Br), ≈3–6% (Hci), and ≈5–9% ((BH)max). These results confirm that the RAS process is a viable alternative to conventional sintering in the short-loop recycling strategies for end-of-life NdFeB magnets, ensuring comparable magnetic performance while significantly reducing sintering time.

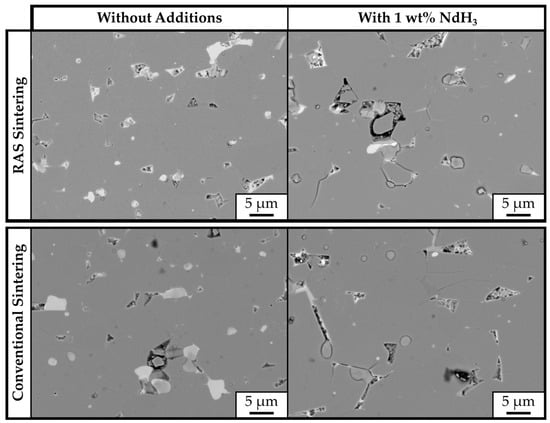

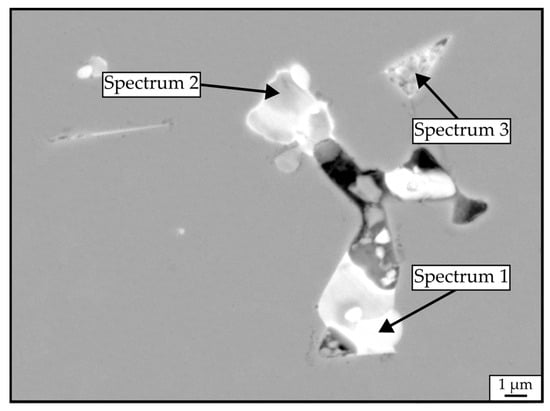

The backscattered-electron (BSE) SEM images, taken on the polished cross-sections of RAS and CS samples, are shown in Figure 5. The samples’ microstructures are comparable, consisting of a gray Nd2Fe14B matrix phase and brighter RE-rich phases located in the triple pockets. Figure 6 shows a higher-magnification BSE-SEM image of sample JM3X-RAS with marked secondary phases analyzed with EDS. Their compositions are shown in Table 4. All three analyzed areas contain significant amounts of oxygen, ranging between 54.5 and 63.3 at.%, showing compositions close to Nd2O3.

Figure 5.

SEM micrographs of bulk samples prepared from powder JM3X. Top left: RAS sample without additive (JM3X-RAS); top right: RAS sample prepared with 1 wt.% NdH3 (JM3X-RAS-NdH3); bottom left: CS sample without additive (JM3X-CS); and bottom right: CS sample prepared with 1 wt.% NdH3 (JM3X-CS-NdH3).

Figure 6.

Representative SEM micrograph in BSE mode of a JM3X-RAS sample prepared without the addition of NdH3. Compositions of the bright Nd-rich phases were quantified by EDS, and the results are displayed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Compositions of the phases outlined in Figure 6, quantified by EDS.

The origin of the kink in the demagnetization curves of samples JM3X-RAS and JM3X-CS is attributed to the presence of oxides. Vasilenko et al. [21] reported that oxides, such as NdOx and Nd2O3, impede the development of continuous thin layers of the Nd-rich phase along the grain boundaries, leading to incomplete magnetic insulation of the Nd2Fe14B grains. This hinders coercivity development by reducing the effective exchange decoupling between the Nd2Fe14B grains. Moreover, poor grain-boundary wetting and oxide grains create weak spots in the microstructure, with a locally reduced nucleation barrier for reversal, leading to a multi-step reversal process [21].

What distinguishes rapid RAS from slow conventional sintering is the duration of the sintering cycle, i.e., the heating rate and dwell time at the sintering temperature of 1100 °C. The heating rates for RAS and CS were 25 and 3 °C/min, and the dwell times were 5 and 120 min, respectively. In RAS, the time during which liquid-phase sintering occurs may be too short to facilitate homogeneous redistribution of the liquid RE-rich phase along the grain boundaries, leaving grains with incomplete magnetic insulation that act as reverse-domain nucleation sites. Consequently, the kink in the curve was more pronounced for the RAS sample.

The positive effect of NdH3 on the magnetic properties, i.e., the coercivity increase and kink elimination, is attributed to an increased volume fraction of the liquid phase during sintering, leading to better magnetic insulation of hard-magnetic grains with the RE-rich grain-boundary phase in the final samples. For the JM3X powder, which has a moderate oxygen content of 0.42 wt.%, the addition of 1 wt.% NdH3 was sufficient to compensate for the absence of a metallic Nd-rich phase in the recycled NdFeB material caused by oxidation. At the same time, this amount was low enough to avoid a reduction in remanence, which might not be achievable with HPMS-based powders with higher oxygen content.

3.4. Effect of Particle Shape on Grain Growth

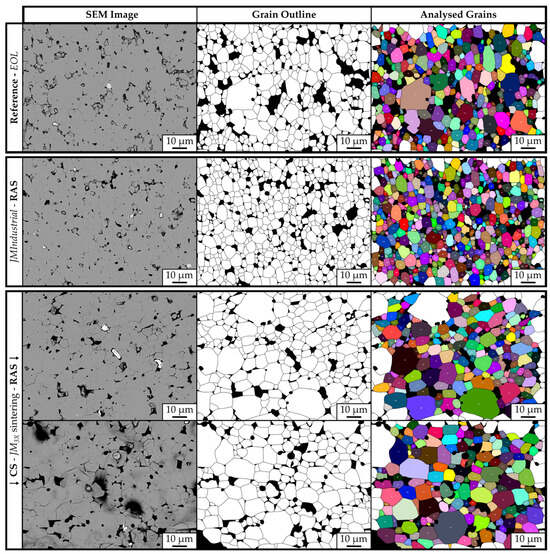

To investigate the grain-growth dynamics for samples prepared with RAS or CS, the polished cross-sections of bulk samples were etched to expose the grain boundaries, and their grain size was analyzed through SEM imaging. Figure 7 shows the etched microstructures with the corresponding traced binary outline masks of the grains and the overlay maps generated by ImageJ for four samples: the EOL magnet (top row), the RAS sample prepared from JMIndustrial powder with the addition of 1 wt.% NdH3 (JMIndustrial-RAS-NdH3) (middle row), and the RAS and CS samples prepared with 1 wt.% NdH3 (JM3X-RAS-NdH3 and JM3X-CS-NdH3) (bottom row). The Dv10, Dv50, and Dv90 values obtained with ImageJ are displayed in Table 5. Unlike powder particle size analysis, where laser diffraction yields true diameters, microstructural grain size measurements reflect random two-dimensional cross-sections of grains. To approximate true grain dimensions, a section-correction factor of 1.5 was applied [12].

Figure 7.

Representative SEM images (1000x magnification) of polished and etched cross-sections of four samples. Top row: EOL magnet. Middle row: RAS sample prepared from JMIndustrial powder with the addition of 1 wt.% NdH3 (JMIndustrial-RAS-NdH3). Bottom row: RAS and CS samples prepared with 1 wt.% NdH3 (JM3X-RAS-NdH3 and JM3X-CS-NdH3). Left column: etched microstructures showing grain morphology. Middle column: binary outline masks with grain boundaries traced (grains in white; pores and secondary phases in black). Right column: ImageJ overlay maps with individual grains colored and numbered. Only fully enclosed grains were included in the analysis.

Table 5.

Grain size statistics (Dv10, Dv50, and Dv90) for the EOL reference magnet and samples JMIndustrial-RAS-NdH3, JM3X-RAS-NdH3, and JM3X-CS-NdH3, showing both the raw measurements from ImageJ and section-corrected values (adjusted by a factor of 1.5).

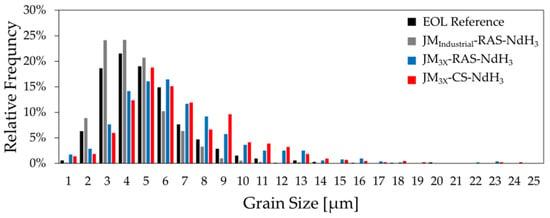

The contrast between the grain sizes of sintered samples prepared from the JMIndustrial and JM3X powders is seen in the relative-frequency distributions in Figure 8. Here, the section-corrected Feret diameters measured by ImageJ were binned (categorized) into 1 µm intervals. The histogram highlights the differences in the grain-size distributions between the samples, revealing that the grains were smaller in the EOL reference magnet and sample JMIndustrial-RAS-NdH3 than in the RAS and CS samples prepared from powder JM3X.

Figure 8.

Relative frequency histograms of grain sizes (after correction) for EOL reference (n = 1046), JMIndustrial-RAS-NdH3 (n = 1496), JM3X-RAS-NdH3 (n = 523), and JM3X-CS-NdH3 (n = 438) samples. Grain diameters were measured from three polished and etched SEM micrographs per sample (1000x magnification) and binned in 1 µm intervals.

The EOL magnet’s section-corrected Dv50 grain size value of 8.2 µm (Table 5) closely matches the Dv50 of the thrice-jet-milled JM3X powder (8.9 µm; see Table 2). This shows that jet milling using a laboratory-scale MC DecJet® 50 jet mill fragmented the HPMS material via intergranular cracking, i.e., along the grain boundaries of the initial EOL magnet. In contrast, the lower Dv50 value of 4.3 µm measured for the JMIndustrial powder prepared with industrial-scale spiral jet mill LabPilot M-Jet 10 confirms that the particle size was further reduced to approximately half the grain size of the EOL magnet via intragranular fracturing. The Dv50 value of 4.3 µm is in the range of industrially used particle sizes of 3–5 µm in the production of sintered NdFeB magnets [22].

During sintering, whether by conventional sintering or the faster RAS method, grain growth beyond the jet-milled particle size was anticipated. Prior studies have shown that sintered (RAS and CS) NdFeB magnets produced from fresh jet-milled powders exhibit grain growth factors of approximately two [12,23]. The grain size analysis of sample JMIndustrial-RAS-NdH3 revealed a Dv50 value of ~7.3 µm, exhibiting a growth factor of 1.71, i.e., lower than previously reported. The reduced grain growth compared to fresh powders can be attributed to the high oxygen content in the JMIndustrial powder (0.59 wt.%) and consequently the presence of RE oxides in the grain boundary phase, which was previously argued to reduce the mobility of the liquid fraction during liquid-phase sintering and consequently the mobility of the solid/liquid interface [24].

The Dv50 values measured for samples JM3X-RAS-NdH3 and JM3X-CS- NdH3 were 10.9 and 11.2 µm, respectively, meaning that the grains grew by factors of 1.23 (RAS) and 1.26 (CS) for powder JM3X. These values are significantly lower than the growth factor reported in the literature (≈2) and the value calculated for powder JMIndustrial (1.71).

A likely explanation for the reduced grain growth factor is related to the morphological specifics of powder JM3X. The intergranular cracking during jet milling preserved the shape of the EOL magnets’ grains (see Figure 3), which have previously undergone sintering followed by post-sinter annealing and are therefore in a near-equilibrated state to accommodate high density in re-sintered magnets. During liquid-phase sintering, grain growth is governed by Ostwald ripening, with the driving force originating in the chemical potential of atoms in grains of different sizes [25,26,27]. The growth driving force ∆g of a particular grain of size 2r, with r being the radius from the center of the grain to the nearest facet, is expressed in Equation (1) [28,29]:

where

- γ is the solid–liquid interfacial energy;

- Vm is the molar volume;

- 2r* is the critical grain size (a grain that is neither growing nor shrinking).

In a liquid-phase sintering system, as is applicable here, a range of ∆g will be found, ranging from negative values for grains smaller than the critical grain size of 2r* to positive values for grains larger than the critical grain size. Grains with positive ∆g will grow during sintering, and grains with negative ∆g will shrink. It is assumed that a fully thermodynamically equilibrated grain will have a growth driving force of ∆g = 0. Fisher and Kang [30] described the behavior of stagnant grain growth (SGG), where the critical driving force for appreciable growth ∆gc is much greater than the maximum driving force for the largest grain in the system ∆gmax. In this scenario, all grains with a positive driving force ∆g > 0 grow very slowly as their growth is controlled by the interface reaction (typically 2D nucleation), resulting in an essentially slow to stagnant growth rate. Combining the theoretical principle of SGG with the assumption of nearly thermodynamically equilibrated grains, the critical driving force is predicted to be significantly higher than the maximum driving force of the largest particle (∆gc >> ∆gmax). The nearly thermodynamically equilibrated grains would exhibit ∆g values just slightly above 0. In summary, the grain growth that occurred in the RAS and CS samples prepared from JM3X powder was stagnant and/or slowed down compared to Normal Grain Growth (NGG) due to the nearly thermodynamically equilibrated grains.

In contrast, the observed grain growth factor of the finer JMIndustrial powder is in line with the NGG behavior described in [30]. The fine powder particles (Dv50 of 4.3 µm) are morphologically rough and not faceted (see Figure 3), leading to high grain-boundary energy and a stronger driving force for grain growth (∆g > 0) during sintering.

Although finer particle sizes are often associated with enhanced intrinsic coercivity (Hci) due to improved domain isolation and reduced defect density [26], the present results show that this correlation is not universal. The JMIndustrial powder, with a smaller initial particle size (Dv50 = 4.3 µm), did not achieve the same refinement effect as the JM3X powder (Dv50 = 8.9 µm) despite its finer particle size. Instead, the superior magnetic performance of the JM3X samples is explained by the interaction between microstructural evolution and the underlying magnetic reversal mechanism.

In sintered NdFeB magnets, coercivity is thought to be primarily nucleation-controlled [24,25]. This process is highly sensitive to grain boundary quality as magnetic insulation between Nd2Fe14B grains must be maintained to ensure effective exchange decoupling. Oxide inclusions or incomplete wetting of the RE-rich phase generate weak spots with locally reduced nucleation barriers, promoting premature reversal and reducing Hci [24]. The JM3X particle morphology, originating from intergranular cracking and preserving near-equilibrium grain facets, facilitates stagnant grain growth (SGG) during sintering. This morphology suppresses grain coarsening (growth factor ~1.2) and helps to maintain a uniform microstructure. The combined effects of SGG and NdH3 addition, which increases the liquid RE-rich phase and improves magnetic insulation, eliminate easy domain-wall nucleation sites, leading to a more homogeneous reversal process. Consequently, the resulting magnets exhibit both high coercivity (up to 742 kA/m at 100 °C) and good squareness (up to 0.86).

4. Conclusions

This work demonstrates that Radiation-Assisted Sintering (RAS) is a viable consolidation route for recycled NdFeB powders obtained through Hydrogen Processing of Magnetic Scrap (HPMS). It enables the production of magnets with magnetic performance comparable to that achieved by conventional sintering. Combined with its previously demonstrated potential for energy-efficient sintering cycles, RAS emerges as a promising method for short-loop magnet-to-magnet recycling.

The grain size analysis of fully dense samples prepared via RAS and conventional sintering revealed that grain growth during liquid-phase sintering is strongly influenced by the initial powder morphology. When jet milling preserves the original grain shape and size of the EOL magnet, the resulting near-equilibrium powder particles exhibit stagnant growth behavior, effectively slowing grain coarsening. This shows that optimized milling conditions, which minimize intragranular fracture, can reduce grain growth during re-sintering by lowering the thermodynamic driving force.

The results also underscore the importance of minimizing additional oxygen uptake during the milling of HPMS-type materials. For an optimally milled powder with an oxygen content of 0.42 wt.%, the addition of 1 wt.% NdH3 fully restored—and even improved—the magnetic performance of the end-of-life (EOL) magnets. In this study, the best-performing samples achieved Br = 1.18 T, (BH)max = 263 kJ/m3, and Hci = 742 kA/m (all measured at 100 °C), surpassing the original EOL magnet by approximately 4% in remanence, 9% in maximum energy product, and 6% in coercivity. The high coercivity of the samples is attributed to the combined effect of an acceptable oxidation level in the milled powder and a low grain growth factor of approximately 1.2, providing new insight for advancing short-loop magnet recycling technologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.B. and T.T.; methodology, F.B., A.B., L.K. and T.T.; validation, F.B., B.P. and T.T.; formal analysis, F.B.; investigation, F.B., A.B., L.G., L.K. and M.K.; resources, L.G. and C.B.; data curation, F.B., A.B. and L.G.; writing—original draft preparation, F.B. and A.B.; writing—review and editing, K.Ž., A.Q. and T.T.; visualization, F.B.; supervision, K.Ž., C.B., A.Q. and T.T.; project administration, C.B., S.K. and A.Q.; funding acquisition, C.B., S.K. and A.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been supported by EIT RawMaterials and co-funded by the European Union under the EIT Regional Innovation Scheme project INSPIRES, Grant No. 20090. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the authors only. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Nelson Brito, Laurence Schieren, and Julian Mastel for providing material data on the industrial jet milling, the end-of-life (EOL) magnet, and the HPMS-derived NdFeB powder.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CS | Conventional Sintering |

| EDS | Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy |

| EOL | End –of Life |

| HPMS | Hydrogen Processing or Magnet Scrap |

| ICP–OES | Inductively Coupled Plasma–Optical Emission Spectroscopy |

| JM | Jet Mill/Jet-Milled, etc. |

| NGG | Normal Grain Growth |

| RAS | Radiation-Assisted Sintering |

| RE | Rare Earth |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscope |

| SGG | Stagnant Grain Growth |

References

- Walton, A.; Anderson, P.; McGuiness, P.; Ogrin, R. Securing Technology-Critical Metals for Britain—Ensuring the United Kingdom’s Supply of Strategic Elements & Critical Materials for a Clean Future; University of Birmingham: Birmingham, UK, 2021; ISBN 9780704429697. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt, C.; Gonzalez-Guiterrez, J.; Hampel, S.; Mitteramskogler, G.; Schlauf, T.; Müller, O.; Degri, M.; Jones, W.; Harmon, S.; Jacques, R.; et al. REProMag—Resource Efficient Production of Magnets, 1st ed.; Steinbeis-Edition: Stuttgart, Germany, 2018; ISBN 978-3-95663-162-7. [Google Scholar]

- Gauß, R.; Burkhardt, C.; Carencotte, F.; Gasparon, M.; Gutfleisch, O.; Higgins, I.; Karajić, M.; Klossek, A.; Mäkinen, M.; Schäfer, B.; et al. Rare Earth Magnet and Motors: A European Call for Action. 2021. Available online: https://www.eit.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2021_09-24_ree_cluster_report2.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Gutfleisch, O.; Willard, M.A.; Brück, E.; Chen, C.H.; Sankar, S.G.; Liu, J.P. Magnetic Materials and Devices for the 21st Century: Stronger, Lighter, and More Energy Efficient. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 821–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Publications Office of the European Union. Regulation (EU) 2024/1252 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 April 2024 Establishing a Framework for Ensuring a Secure and Sustainable Supply of Critical Raw Materials and Amending Regulations (EU) No 168/2013, (EU) 2018/858, (EU) 2018/1724 and (EU) 2019/1020; Official Journal of the European Union, EU: Luxembourg, 2024; pp. 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, H.; Afiuny, P.; McIntyre, T.; Yih, Y.; Sutherland, J.W. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of NdFeB Magnets: Virgin Production versus Magnet-to-Magnet Recycling. Procedia CIRP 2016, 48, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, J.; Schreiber, A.; Zapp, P.; Walachowicz, F. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of NdFeB Permanent Magnet Production from Different Rare Earth Deposits. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 5858–5867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakotnik, M.; Tudor, C.O.; Peiró, L.T.; Afiuny, P.; Skomski, R.; Hatch, G.P. Analysis of Energy Usage in Nd–Fe–B Magnet to Magnet Recycling. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2016, 5, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, I.R.; Williams, A.; Walton, A.; Speight, J. Magnet Recycling. U.S. Patent 8734714, 27 May 2014. pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt, C.; van Nielen, S.; Awais, M.; Bartolozzi, F.; Blomgren, J.; Ortiz, P.; Xicotencatl, M.B.; Degri, M.; Nayebossadri, S.; Walton, A. An Overview of Hydrogen Assisted (Direct) Recycling of Rare Earth Permanent Magnets. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2023, 588, 171475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, A.; Yi, H.; Rowson, N.A.; Speight, J.D.; Mann, V.S.J.; Sheridan, R.S.; Bradshaw, A.; Harris, I.R.; Williams, A.J. The Use of Hydrogen to Separate and Recycle Neodymium–Iron–Boron-Type Magnets from Electronic Waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 104, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomše, T.; Ivekovič, A.; Kocjan, A.; Šturm, S.; Žužek, K. A Rapid Thermal-Radiation-Assisted Sintering Strategy for Nd–Fe–B-Type Magnets. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2024, 26, 2401404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooroshy, J.; Tiess, G.; Tukker, A.; Walton, A. Strengthening the European Rare Earths Supply-Chain. 2015. Available online: https://www.mawi.tu-darmstadt.de/media/fm/homepage/news_seite/ERECON_Report_v05.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Sohrabi Baba Heidary, D.; Lanagan, M.; Randall, C.A. Contrasting Energy Efficiency in Various Ceramic Sintering Processes. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2018, 38, 1018–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.J.; McGuiness, P.J.; Harris, I.R. Mass Spectrometer Hydrogen Desorption Studies on Some Hydrided NdFeB-Type Alloys. J. Less Common Met. 1991, 171, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramoff, M.D.; Magalhaes, P.J.; Ram, S.J. Image Processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics Int. 2004, 1–7. Available online: https://imagescience.org/meijering/publications/download/bio2004.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 Years of Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhardt, F. ImageJ Tutorial—Quantitative Image Analysis and Grain Size Analysis (V1.2). 2025. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/15534807 (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Nakamura, M.; Matsuura, M.; Tezuka, N.; Sugimoto, S.; Une, Y.; Kubo, H.; Sagawa, M. Effect of Annealing on Magnetic Properties of Ultrafine Jet-Milled Nd-Fe-B Powders. Mater. Trans. 2014, 55, 1582–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, O.; Schönfeldt, M.; Brouwer, E.; Dirks, A.; Rachut, K.; Gassmann, J.; Güth, K.; Buckow, A.; Gauß, R.; Stauber, R.; et al. Towards an Alloy Recycling of Nd–Fe–B Permanent Magnets in a Circular Economy. J. Sustain. Metall. 2018, 4, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilenko, D.Y.; Shitov, A.V.; Bratushev, D.Y.; Podkorytov, K.I.; Gaviko, V.S.; Golovnya, O.A.; Popov, A.G. Magnetics Hysteresis Properties and Microstructure of High-Energy (Nd,Dy)–Fe–B Magnets with Low Oxygen Content. Phys. Met. Metallogr. 2021, 122, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagawa, M.; Une, Y. The Status of Sintered NdFeB Magnets. In Modern Permanent Magnets; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 135–168. [Google Scholar]

- Uestuener, K.; Katter, M.; Rodewald, W. Dependence of the Mean Grain Size and Coercivity of Sintered Nd–Fe–B Magnets on the Initial Powder Particle Size. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2006, 42, 2897–2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarriegui, G.; Martín, J.M.; Burgos, N.; Ipatov, M.; Zhukov, A.P.; Gonzalez, J. Effect of Particle Size on Grain Growth of Nd-Fe-B Powders Produced by Gas Atomization. Mater. Charact. 2022, 187, 111824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.-J.L. Sintering; Butterworth Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lifshitz, I.M.; Slyozov, V. The kinetics of precipitation from supersaturated solid solutions *. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 1961, 19, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, C.; Wagner, C. Theorie Der Alterung von Niederschliigen Durch Umlosen (Ostwald-Reifung). Z. für Elektrochem. 1961, 65, 581–591. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Y.-I.; Kang, S.-J.L.; Yoon, D.Y. Coarsening of Polyhedral Grains in a Liquid Matrix. J. Mater. Res. 2009, 24, 2949–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, W.; Kim, D.; Hwang, N. Effect of Interface Structure on the Microstructural Evolution of Ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2006, 89, 2369–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J.G.; Kang, S.L. Strategies and Practices for Suppressing Abnormal Grain Growth during Liquid Phase Sintering. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2019, 102, 717–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).