Abstract

The surface smoothness of composite restorations affects not only their esthetic appearance but also other properties. Thus, rough surfaces can lead to staining, plaque accumulation, gingival irritation, recurrent caries, abrasiveness, wear kinetics, and tactile perception by the patient. The aim of this study was to evaluate the influence of irrigation during the finishing and polishing of composite resin restorations. A systematic search of the PubMed, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Clinical Trials databases was conducted. Papers published up to 11 February 2021 were considered. The quality of each study was assessed using the modified Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials checklist for reporting in vitro studies on dental materials. No clinical studies were identified. Six in vitro studies were included, reporting changes in physical and esthetic properties. After performing a methodological quality assessment of the studies, some limitations were identified, the main limitation being the heterogeneous methodology across studies. The evidence resulting from this systematic review did not favor either wet or dry finishing/polishing procedures. There is a clear need for well-designed studies focusing on the comparison of dry/wet finishing/polishing with standard protocols to evaluate the differences among different materials and methods.

1. Introduction

Composite resins have been increasingly used for direct restoration of both anterior and posterior teeth because of their optimal esthetics, improved physical and mechanical properties, availability of efficient bonding systems, and public concerns over amalgam use [1,2].

The esthetic appearance of the composite resin restorations is potentiated by finishing and polishing procedures. Finishing is related to the contouring, shaping, and smoothing of the restoration to give anatomical contours and remove excess material at the interface. After finishing, polishing is performed to achieve a surface with high luster and enamel-like texture [3].

The surface smoothness of the composite restorations affects not only their esthetic appearance but also other properties. Thus, rough surfaces can lead to staining, plaque accumulation, gingival irritation, recurrent caries, abrasiveness, wear kinetics, and tactile perception by the patient [4].

Finishing and polishing are frictional processes and thus produce heat. Excess heat may affect the interface between the tooth and adhesive bond [5], and also damage the pulp [6]. For this reason, the need for lubrication/coolant is a fundamental aspect.

Several studies have evaluated the effect of different finishing and polishing procedures on surface roughness, hardness, and temperature rise of composites [7,8,9]. However, there is no consensus in the literature about the difference between dry or wet finishing/polishing on the surface characteristics of composites.

Thus, the objective of this systematic review was to evaluate the influence of irrigation during the finishing and polishing of composite resin restorations, answering the following population, intervention, comparison, and outcome (PICO) question, “Does irrigation during the finishing and polishing steps influence the properties of composite resins?”, described in detail in Table 1.

Table 1.

Population, intervention, comparison, and outcome (PICO) question.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review was performed following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis protocol (PRISMA-P).

2.1. Search Strategy

The studies included in this systematic review were obtained from the MEDLINE (accessed through PubMed), Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Clinical Trials databases. Gray literature was not included in this review. No restrictions on the year of publication, region, or language were considered. Articles published between January 1977 and 11 February 2021 were retrieved. The search terms used for each database are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Search terms used in each one of the databases.

The duplicate references were removed automatically using Mendeley (RELX Group, London, UK) and then checked manually by two authors.

The initial selection of the articles to be included was accomplished by two independent authors reading the titles and abstracts. Afterwards, the full text of each potentially relevant study was retrieved and also independently analyzed by two authors. The opinion of a third author was consulted when necessary.

The references of the included studies were searched to identify additional relevant references.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

For this systematic review, only studies which met the following inclusion criteria were selected: (a) clinical studies or in vitro studies with resin blocks or extracted teeth; (b) evaluation on composite resins; (c) use of polishing systems with and/or without coolant; (d) studies that evaluated one or more of the following properties—color, roughness, microhardness, microleakage, gloss, temperature, and particle and substance release (e.g., bisphenol-A).

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) in vivo studies; (b) materials other than composite resins; (c) studies that did not evaluate the intended parameters; and (d) studies lacking the comparison of wet and dry finishing/polishing procedures using the same finishing/polishing system.

2.3. Data Extraction

The studies that fulfilled the inclusion criteria were processed for data extraction. The data were recorded as follows: first author and year of publication, groups and number of samples, materials, and time used per disc during polishing. The following outcomes were extracted: roughness (μm), microhardness, color change (ΔE), and temperature rise (°C).

The extraction of the information was done by two independent authors using a standard form. A consensus meeting was always held to confirm the agreement and to resolve any disagreement between the reviewers.

2.4. Quality Assessment

The evaluation of the methodological quality of the included studies is essential for understanding the results. Therefore, the quality of each in vitro study was assessed using the modified Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) checklist [10] for reporting in vitro studies on dental materials. When applying this checklist, items 5 to 9 could not be evaluated since these are designed to evaluate sample standardization (no author assessed this parameter). Two independent authors assessed the quality of the studies independently, and any disagreement was solved through discussion and consensus. The opinion of a third author was consulted when necessary.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

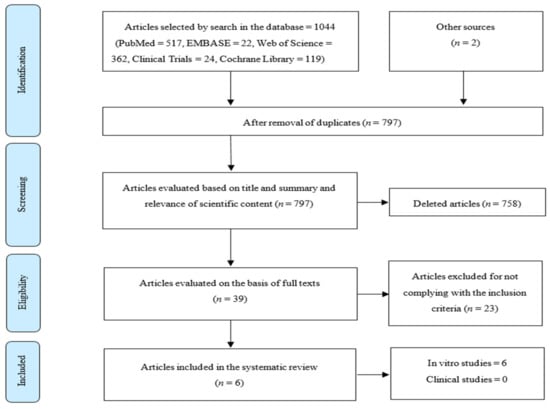

The PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) flow diagram of the study selection process.

A total of 1044 studies were identified through the search in the referred databases. After the removal of duplicates, a total of 797 articles were obtained, of which 39 were selected after reading the titles and abstracts. The full-text reading led to the exclusion of 23 articles when submitted to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Two articles were included after analysis of the reference lists of the selected studies. No clinical studies were identified. Six in vitro studies were considered for analysis (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of the included studies.

3.2. Study Characteristics

Regarding the year of publication, the oldest study was published in 1991 [11], and the most recent one was published in 2019 [15].

All studies evaluated the finishing/polishing under both wet and dry conditions. Kaminedi et al. [13] also studied the differences between immediate and delayed finishing/polishing.

Regarding the finishing/polishing system, Sof-Lex™ discs (3M ESPE, Minneapolis, MN, USA) were used in five studies [11,12,13,14,15], and Super-Snap® discs (Shofu Dental, San Marcos, CA, USA) were used by Jones et al. [9]. Kaminedi et al. [13] used diamond finishing burs (Diatech, Coltene, Geneve, Switzerland) in the finishing procedures and de Freitas et al. [15] employed a multilaminated carbide bur (48L-010: Angelus, Londrina, Brazil) and Sof-Lex™ spirals in the finishing/polishing procedures. The time spent using each disc varied widely among studies (10–30 s).

The included studies reported results on different types of materials including macrofilled [11], microfilled [11], hybrid [9,11,13], microhybrid [12,14], nanofilled [12], and nanohybrid [13,14,15] composites.

A summary of conclusions from the included studies can be found in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of conclusions from the included studies.

3.3. Quality Assessment

Methodological quality assessment outcomes are presented in Table 5. All studies presented results for each experimental group; however, none of them referred to confidence intervals. Only one study [15] reported study limitations and sources of potential bias (item 12).

Table 5.

Modified Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) checklist for reporting in vitro studies of dental materials.

4. Discussion

High-quality finishing and polishing of dental restorations are essential aspects of clinical restorative procedures that enhance both esthetics and longevity of restored teeth [3]. Aiming to have the best finishing and polishing technique, it is vital to know not only if the irrigation improves the quality of the final result or not but also if it changes the material properties or damages the tooth (e.g., triggered by temperature rise).

The surface roughness of composite resins depends not only on intrinsic but also on extrinsic factors. Intrinsic factors include the type of material, type of filler, shape, size, and distribution of filler particles, degree of polymerization, resin matrix composition, and durability of filler/matrix bond [16]. Extrinsic factors are related to the finishing and polishing techniques and include the flexibility and geometrical shape of polishing tools, the hardness of abrasive particles, operator skills, and the way each technique is carried out [17]. Regarding the intrinsic factors and by following the general belief that composites with smaller filler particles prevent the wear of the resin matrix and minimize the surface alteration deriving from the particles’ detachment, it was expected that nanofilled and nanohybrid composites allowed for better surface smoothness. However, there is a low-level evidence attesting it [18]. As an extrinsic factor, different finishing and polishing tools (Sof-Lex™ discs [11,12,13,14,15], Super Snap® discs [9], spirals [15], and burs [13,15]) and their manipulation (including the time per disc) may have contributed to the different results across studies.

When finishing and polishing procedures are performed without lubrication, a rise in materials temperature due to frictional forces is expected. When a sample is dry finished, a temperature rise at the surface level may cause localized softening and melting (exceeded glass transition point). This may lead to smearing of the resin over any exposed particles, making the particle-like appearance not so noticeable, and the surface smoother [9,11,12], which supports the results of Dodge et al. [11], Cardoso et al. [12], and Jones et al. [9]. However, dry finishing and polishing were revealed to be less successful (higher surface roughness) in other studies [13,14,15] and this can be supported by the fact that the abrasive particles separated from the polishing tool may be embedded into the composite’s surface. Furthermore, accumulation of separated particles on the surface of polishing tools can decrease its efficiency when attempting to smooth the surface [11]. On the other hand, the heat generated during dry finishing and polishing is high and can degrade the filler/matrix bond and result in separation of filler particles from the matrix and subsequently increase the surface roughness [5]. Moreover, other factors could explain these variable results, such as the application time and the variability among different operators regarding the applied load and speed of finishing and polishing [19]. The grit size of the polishing discs may also contribute to the changes in surface temperature, since when the disc is switched from one with a greater grit size to another one with a smaller grit, the temperature does not decrease, in fact, there is a temperature rise [9]. However, according to Lloyd et al. [20], this temperature rise is not hazardous for dental pulp because composites are heat insulators, and the generated heat during dry finishing and polishing is confined to the composite surface such that at 0.2 mm depth from the composite surface, the temperature does not exceed 10 °C.

Surface hardness is another important material property which correlates well with compressive strength, resistance to intra-oral softening, and conversion degree [21,22]. Low surface hardness values are largely related to inadequate wear resistance and can lead to failure of the restoration [23]. Composite hardness depends on several factors such as type and shape of filler particles, their composition and distribution, percentage of filler particles, and resin type. Reduction in the hardness of filler particles directly decreases the hardness of composite [24]. Kaminedi et al. [13] reported that although the finishing under coolant resulted in the highest surface hardness for micro hybrid resin (Filtek™ Z250), dry finishing groups showed a significant increase in surface hardness of the nano-composite resin material and a non-significant increase of hardness of the surfaces of hybrid composite materials. Furthermore, Nasoohi et al. [14] reported that hardness of all composite samples also increased when performing dry finishing. These results can be explained by the fact that hardness of composite increases by raising the temperature up to 60 °C, which is due to increased cross-linking between polymer chains [25]. Moreover, infrared tomography assessments have shown that the temperature at the surface of composites submitted to dry finishing and polishing is 140 °C or higher [14]. That temperature rise increases cross-linking and hardness because the temperature is higher than the glass-transition temperature of resin content [26].

Color change over time represents a problem for composite resin restorations. It depends on several factors, such as oral beverage and food colorant ingestion, poor hygiene, type of composite resin, the restorative technique used, as well as the finishing and polishing technique (surface roughness) [15,27,28]. Despite having only studied the Filtek™ Z-350 XT, de Freitas et al. [15] observed variations depending on the type of finishing and polishing technique, showing the importance of using irrigation to reduce color change, mainly when spirals are used.

Even though in vitro research cannot accurately reproduce the oral environment, only these experiments are able to provide information on the tribological properties of composite surfaces, which is why only in vitro studies were considered for inclusion in this review. However, after performing a methodological quality assessment of the included studies, some limitations were identified, the main limitation being the heterogeneous methodology across studies. Not all of them evaluated the same type of composite resin, there were different finishing/polishing materials and methods, and only four [11,12,13,14] and two [11,15] of them studied microhardness and color change, respectively. Furthermore, the majority of the studies evaluated a small number of samples in each group (n)—Jones et al. [9] had several experimental groups with a sample size of just one sample per group. Thus, this methodological variability observed among the included studies prevents us from drawing conclusions, making it vital to conduct further experiments with clear and established protocols in order to allow future comparison among a wider range of studies. As such, there is a clear need for researchers to conduct well-designed studies focusing on the comparison of dry vs. wet finishing/polishing with standard protocols to evaluate the differences among different materials and methods.

5. Conclusions

Different finishing and polishing protocols influence microhardness, roughness, color, and surface temperature of resin composites. However, the evidence resulting from this systematic review did not favor either wet or dry finishing/polishing procedures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C., A.P., I.A., C.M.M., and E.C.; methodology, A.C., A.P., C.M.M., M.M.F., E.C.; software: J.P.S., A.C., and C.M.M.; validation, A.C., A.P., I.A., and C.M.M.; data curation, J.P.S., A.C., A.P., I.A., and C.M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.P.S. and J.S.; writing—review and editing, A.C., A.P., M.M.F., C.M.M., and E.C.; supervision, A.C., A.P., C.M.M., M.M.F., and E.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lee, I.B.; Chang, J.; Ferracane, J. Slumping resistance and viscoelasticity prior to setting of dental composites. Dent. Mater. 2008, 24, 1586–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senawongse, P.; Pongprueksa, P. Surface roughness of nanofill and nanohybrid resin composites after polishing and brushing. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2007, 19, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jefferies, S.R. Abrasive Finishing and Polishing in Restorative Dentistry: A State-of-the-Art Review. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2007, 51, 379–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Roeder, L.B.; Lei, L.; Powers, J.M. Effect of surface roughness on stain resistance of dental resin composites. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2005, 17, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, G.C.; Franke, M.; Maia, H.P. Effect of finishing time and techniques on marginal sealing ability of two composite restorative materials. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2002, 88, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zach, L.; Cohen, G. Pulp response to externally applied heat. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1965, 19, 515–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başeren, M. Surface roughness of nanofill and nanohybrid composite resin and ormocer-based tooth-colored restorative materials after several finishing and polishing procedures. J. Biomater. Appl. 2004, 19, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, M.; Sehr, K.; Klimek, J. Surface texture of four nanofilled and one hybrid composite after finishing. Oper. Dent. 2007, 32, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.S.; Billington, R.W.; Pearson, G.J. The effects of lubrication on the temperature rise and surface finish of amalgam and composite resin. J. Dent. 2007, 35, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faggion, C.M. Guidelines for reporting pre-clinical in vitro studies on dental materials. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2012, 12, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodge, W.W.; Dale, R.A.; Cooley, R.L.; Duke, E.S. Comparison of wet and dry finishing of resin composites with aluminum oxide discs. Dent. Mater 1991, 7, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, P.D.C.; Araújo, A.; Lopes, G.C. Influence of the cooling on the surface roughness and hardness of composite resins during polishing procedure. R Dent. Press Estét. 2005, 2, 104–112. [Google Scholar]

- Kaminedi, R.; Penumatsa, N.; Priya, T.; Baroudi, K. The influence of finishing/polishing time and cooling system on surface roughness and microhardness of two different types of composite resin restorations. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2014, 4, 99. [Google Scholar]

- Nasoohi, N.; Hoorizad, M.; Tabatabaei, S.F. Effects of Wet and Dry Finishing and Polishing on Surface Roughness and Microhardness of Composite Resins. J. Dent. 2017, 14, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- de Freitas, M.; de Freitas, D.; de Almeida, L.; Magalhães, A.; Cardoso, P.; Decurcio, R. Influence of wet finishing and polishing on composite resins: Surface roughness, color stability and surface morphology. Rev. Odontológica Bras. Cent. 2019, 28, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marghalani, H.Y. Effect of finishing/polishing systems on the surface roughness of novel posterior composites. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2010, 22, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchgraber, B.; Kqiku, L.; Allmer, N.; Jakopic, G.; Stätler, P. Surface roughness of one nanofill and one silorane composite after polishing. Coll. Antropol. 2011, 35, 879–883. [Google Scholar]

- Angerame, D.; de Biasi, M. Do nanofilled/nanohybrid composites allow for better clinical performance of direct restorations than traditional microhybrid composites? A systematic review. Oper. Dent. 2018, 43, 191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, C.S.; Billington, R.W.; Pearson, G.J. Interoperator variability during polishing. Quintessence Int. 2006, 37, 183–190. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, B.A.; Rich, J.A.; Brown, W.S. Effect of Cooling Techniques on Temperature Control and Cutting Rate for High-Speed Dental Drills. J. Dent. Res. 1978, 57, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badra, V.V.; Faraoni, J.J.; Ramos, R.P.; Palma-Dibb, R.G. Influence of different beverages on the microhardness and surface roughness of resin composites. Oper. Dent. 2005, 30, 213–219. [Google Scholar]

- Uhl, A.; Mills, R.W.; Jandt, K.D. Photoinitiator dependent composite depth of cure and Knoop hardness with halogen and LED light curing units. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 1787–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Say, E.C.; Civelek, A.; Nobecourt, A.; Ersoy, M.; Guleryuz, C. Wear and microhardness of different resin composite materials. Oper. Dent. 2003, 28, 628–634. [Google Scholar]

- Marghalani, H.Y. Post-irradiation Vickers microhardness development of novel resin composites. Mater. Res. 2010, 13, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, C.L.; Duysters, P.P.E.; de Lange, C.; Bausch, J.R. Structural changes in composite surface material after dry polishing. J. Oral Rehabil. 1981, 8, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bausch, J.R.; Delange, C.; Davidson, C.L. The influence of temperature on some physical properties of dental composites. J. Oral Rehabil. 1981, 8, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrami, R.; Ceci, M.; de Pani, G.; Vialba, L.; Federico, R.; Poggio, C.; Colombo, M. Eur. J. Dent. 2018, 12, 49–56.

- Kumari, R.V.; Nagaraj, H.; Siddaraju, K.; Poluri, R.K. Evaluation of the Effect of Surface Polishing, Oral Beverages and Food Colorants on Color Stability and Surface Roughness of Nanocomposite Resins. J. Int. Oral Health 2015, 7, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).