Abstract

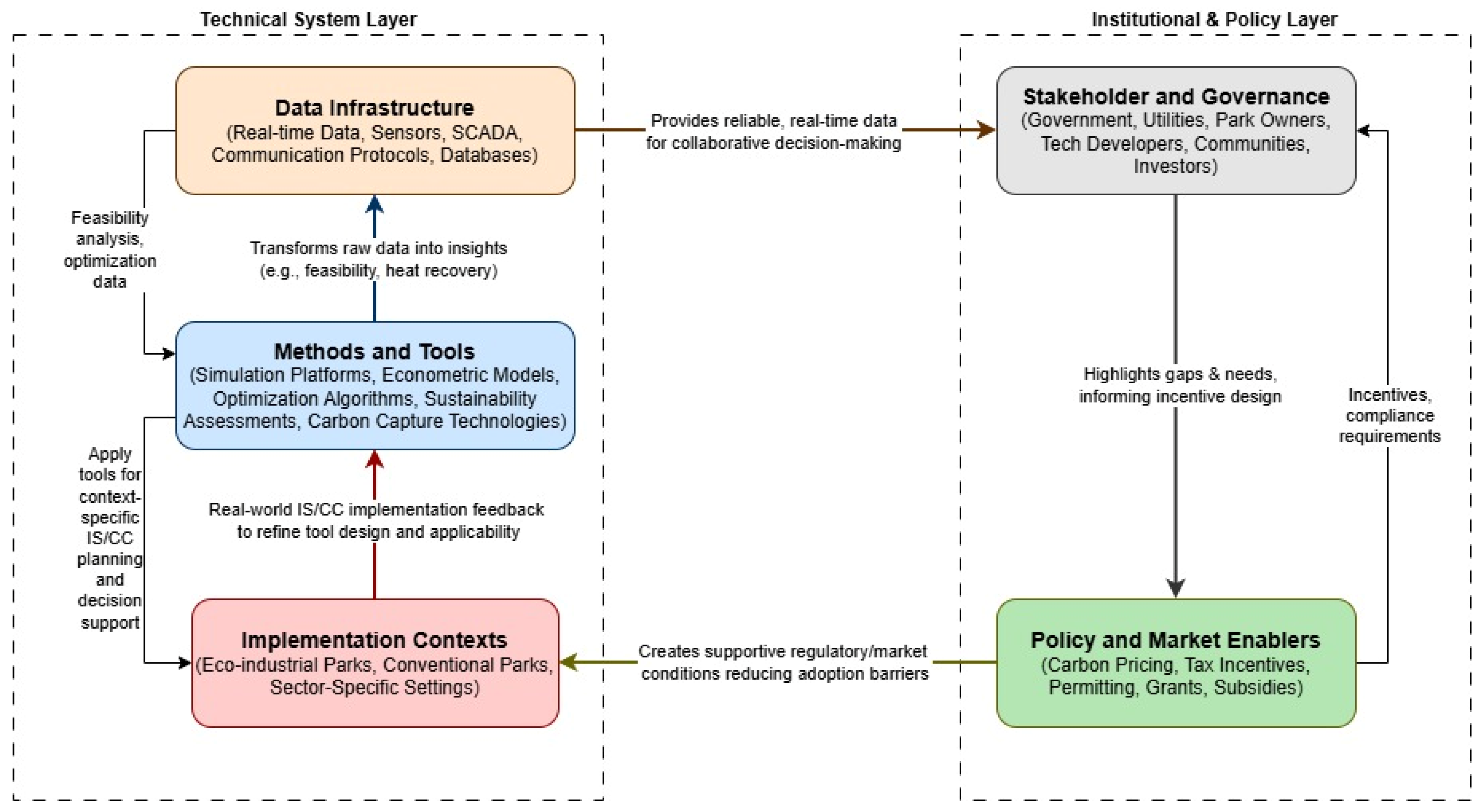

Industrial symbiosis and carbon capture are increasingly recognized as critical strategies for reducing emissions and resource consumption in industrial parks. However, existing research remains fragmented across tools, methods, and case-specific applications, providing limited guidance for effective real-world deployment of data-driven approaches. This study addresses this gap through a PRISMA-guided scoping review of 116 publications, complemented by a targeted practitioner survey conducted within the IEA IETS Task 21 initiative to assess practical relevance and adoption challenges. The review identifies a broad landscape of data-driven tools, ranging from high-technology-readiness simulation and optimization platforms to emerging visualization and matchmaking solutions. While the literature demonstrates substantial methodological maturity, the combined evidence reveals a persistent gap between tool availability and effective implementation. Key barriers include fragmented and non-standardized data infrastructures, confidentiality constraints, limited stakeholder coordination, and weak policy and market incentives. Based on the integrated analysis of literature and practitioner insights, the paper proposes a conceptual framework that links tools and methods with data infrastructure, stakeholder governance, policy, and market enablers, and implementation contexts. The findings highlight that improving data governance, interoperability, and collaborative implementation pathways is as critical as advancing analytical capabilities. The study concludes by outlining focused directions for future research, including AI-enabled optimization, standardized data-sharing frameworks, and coordinated pilot projects to support scalable low-carbon industrial transformation.

1. Introduction

Global climate change remains an urgent concern that demands innovative pathways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and manage finite natural resources [1]. As populations expand and economic activities intensify, energy, water, and raw materials become increasingly strained, driving the need for sustainable industrial solutions [2]. Recent estimates indicate that worldwide energy demand could reach 15,755 million tons by 2030, underscoring the gravity of the resource challenge [3]. In response, industrial parks and eco-industrial parks have gained increasing attention as system-level intervention points for coordinating industrial activities, minimizing waste, and enhancing collective competitiveness. By aligning with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, eco-industrial parks leverage industrial symbiosis, defined as data- and exchange-driven collaboration among co-located or networked industries, where materials, energy, water, and by-products are shared to establish more resilient and low-carbon production networks [4,5].

Despite the increasing global focus on eco-industrial parks, limited clarity remains regarding how industrial symbiosis and carbon capture tools are operationalized, integrated, and scaled in real-world industrial settings. Industrial symbiosis has proven effective in reducing pollution and resource dependency [6,7], yet its broader adoption, particularly for carbon mitigation, depends on the availability of robust, data-driven analytical tools and decision-support frameworks. While numerous advanced approaches, including combined heat and power optimization, hydrogen-based multi-energy systems [8], and integrated electricity–heat networks have been piloted in industrial zones worldwide, and guidance on tool selection, implementation pathways, and scalability across heterogeneous industrial contexts remains fragmented [9,10]. According to [11], existing industrial symbiosis tools tend to focus on individual resource streams, leaving a significant research gap in the integrated optimization of energy, water, power, carbon, and waste flows. As a result, practitioners and planners face persistent challenges in selecting appropriate tools that align with both technical requirements and organizational realities.

Recent review studies have contributed valuable classifications of industrial symbiosis tools and conceptual frameworks for eco-industrial parks, yet they predominantly emphasize technical feasibility, policy design, or resource-flow optimization in isolation. Comparatively limited attention has been given to how data-driven tools are adopted, combined, and governed across real-world industrial contexts, particularly when carbon capture is considered alongside industrial symbiosis. Building on prior classification-oriented reviews, such as a review by Lawal and Wan Alwi [11], this study advances the literature by explicitly integrating practitioner perspectives and by examining adoption feasibility, usability, and governance challenges associated with industrial symbiosis–carbon capture tools.

Similarly, research on the systematic integration of carbon capture within industrial symbiosis networks remains at an early stage, despite its potential to substantially reduce greenhouse gas emissions while strengthening economic viability [12,13]. Carbon capture refers to technologies that reduce carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from stationary sources through permanent storage or conversion into valuable products, as commonly framed within the Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage paradigm [14,15]. In this paper, carbon capture is understood not only as a set of process technologies, such as post-combustion CO2 removal and catalytic methanation, but also as a data-supported system function enabled through emissions monitoring, optimization, and heat recovery tools. This broader interpretation reflects the growing importance of digital and data-driven infrastructures in industrial decarbonization strategies. This broader interpretation reflects the increasing importance of digital and data-driven infrastructures in enabling integrated industrial decarbonization strategies rather than isolated technology deployment.

To address these gaps, this study adopts a dual-method approach. First, a PRISMA-guided scoping review is conducted to systematically map tools and methods that support the integration of industrial symbiosis and carbon capture in industrial and commercial parks. Second, the review is complemented by a targeted practitioner survey conducted within the International Energy Agency (IEA) Industrial Energy-Related Technologies and Systems (IETS) Task 21 initiative, capturing empirical insights from technology developers and users with direct experience in applying these tools. The scoping review encompasses data-driven simulation and modeling tools, statistical and econometric methods, optimization frameworks, data collection and management techniques, and decision-support platforms, while the survey provides practical perspectives on usability, maturity, and implementation barriers.

Specifically, this paper addresses the following research question: What data-driven tools and methods are employed to support the integration of industrial symbiosis and carbon capture in industrial and commercial parks, and which technical, organizational, and policy-related factors influence their effective deployment? By systematically synthesizing published evidence and practitioner experiences, this study offers both a structured analytical overview and an empirically grounded assessment of enabling conditions, technology readiness levels, persistent barriers, and real-world performance of industrial symbiosis and carbon capture interventions.

This scoping review helps fill a critical knowledge gap, as existing studies rarely connect tool development with adoption feasibility, despite the growing recognition of eco-industrial parks as key instruments for emissions reduction, economic resilience, and sustainable industrial transformation [16,17]. Moreover, prior research typically emphasizes either high-level policy frameworks or isolated technology case studies, without providing an integrated mapping of tools across data requirements, decision functions, and implementation contexts. By incorporating practitioner survey evidence, this study aligns theoretical potential with operational constraints, thereby offering actionable insights for policymakers, industrial park operators, and researchers seeking scalable pathways toward low-carbon industrial development.

The contributions of this study are threefold. From a theoretical perspective, the paper extends existing industrial symbiosis and carbon capture literature by conceptualizing these domains as an integrated, data-driven ecosystem rather than as parallel or loosely coupled strategies. From a methodological perspective, the study combines a PRISMA-guided scoping review with practitioner survey evidence to link tool development with adoption feasibility. From a practical perspective, the paper provides actionable insights for policymakers, industrial park operators, and technology developers by identifying governance, data, and implementation conditions that shape successful deployment.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 describes the review protocol and survey design, including eligibility criteria, data extraction, and analytical procedures. Section 3 presents the results of the study, with Section 3.1 reporting the literature review results derived from the PRISMA-guided scoping review and Section 3.2 presenting the practitioner survey results. Section 4 discusses the findings, introduces an integrated conceptual framework for industrial symbiosis and carbon capture deployment, and identifies key barriers and enablers. Section 5 concludes the paper by summarizing contributions, acknowledging limitations, and outlining directions for future research.

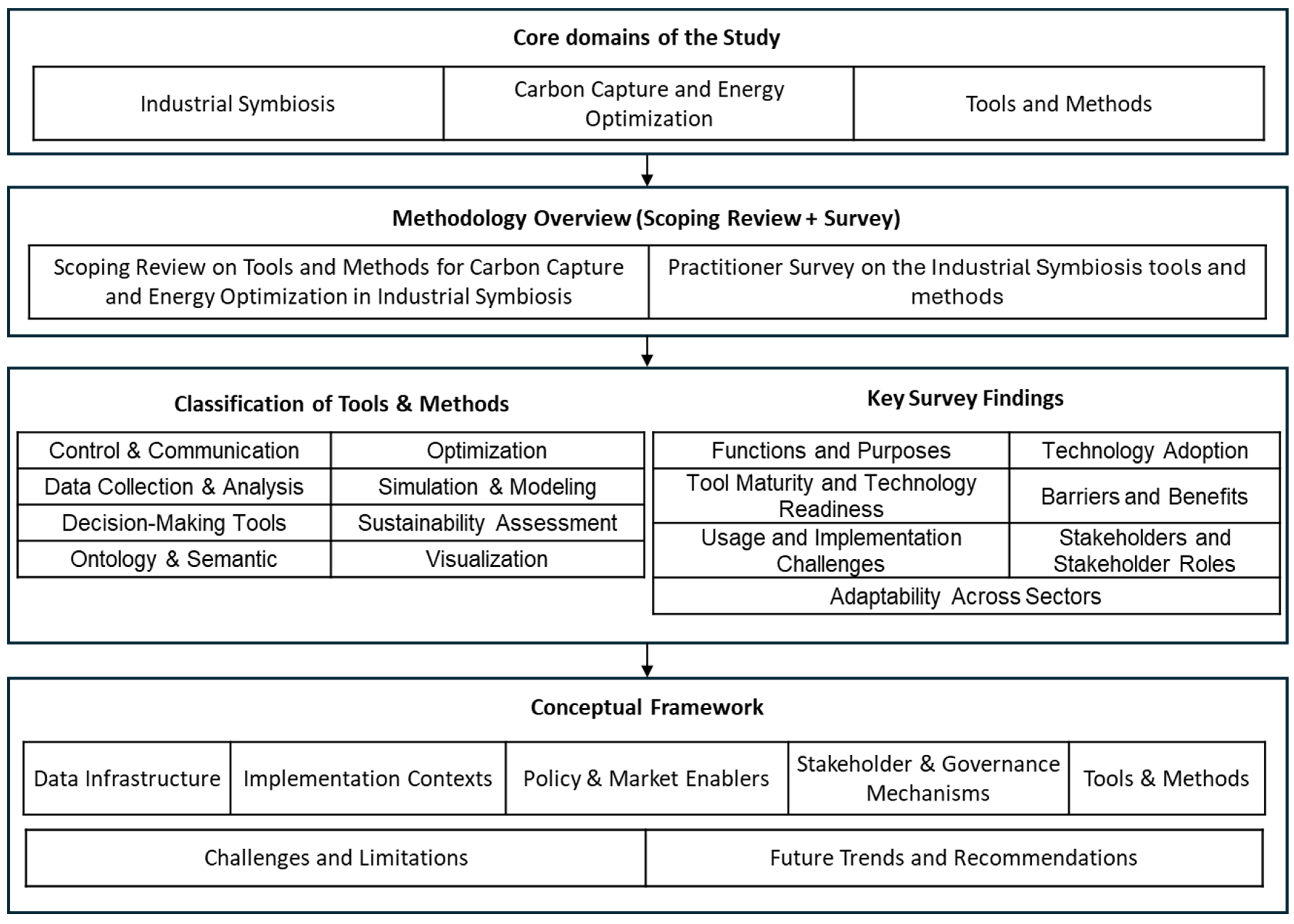

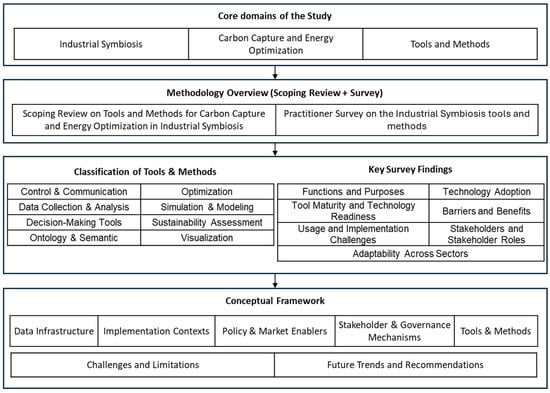

Figure 1, which illustrates the overall paper structure and research flow, is provided after the methodological description to support clarity and avoid interrupting the conceptual framing of the introduction.

Figure 1.

Paper structure and research flow.

2. Materials and Methods

This study employed a dual-methods approach consisting of (i) a structured literature review to examine existing research on industrial symbiosis tools and methods and (ii) a survey of technology providers and users to explore the practices, perceived effectiveness, and challenges in using and implementing these tools. A PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) approach was adopted because the objective is to comprehensively map concepts, tool types, and research characteristics across a heterogeneous literature base, rather than to estimate intervention effects or perform evidence grading as in a full systematic review. Accordingly, the review process followed elements of the PRISMA extension for scoping review guidelines [18], while the survey design was guided by best practices in mixed-methods research [19].

2.1. Literature Review Protocol

The scoping review aims to map the diverse methods and tools that support the integration of industrial symbiosis and carbon capture in industrial and commercial parks. A scoping review protocol was developed before initiating the review. Although it was not registered in a public database, the protocol was internally reviewed and approved by the research team. The protocol specified objectives, inclusion/exclusion criteria, search strategy, and data synthesis procedures, ensuring methodological rigor and reproducibility (see Table 1). Any modifications to the protocol were documented and justified.

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria.

Table 1 summarizes the eligibility criteria used during screening and final inclusion. To improve transparency of the inclusion logic, the criteria were operationalized as three sequential decision rules applied consistently across records:

- (1)

- Topical relevance. The study must address industrial symbiosis in industrial or commercial parks and must report a tool, method, or data-driven approach that supports analysis, design, optimization, decision making, assessment, or implementation. Studies focusing on industrial sustainability without an explicit industrial symbiosis focus in an industrial or commercial park context were excluded.

- (2)

- Evidence type. Empirical studies were included (quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods). Studies were excluded if they lacked original research content relevant to tools or methods, including editorials, opinion pieces, non-peer-reviewed reports, and abstract-only records.

- (3)

- Publication constraints. Peer-reviewed journal articles and conference papers written in English were included. Publications in other languages were excluded.

Carbon capture integration was treated as an inclusion-relevant scope element rather than a mandatory requirement. Specifically, studies were included if they addressed industrial symbiosis in parks and either (i) explicitly examined carbon capture or Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage integration, or (ii) addressed energy and carbon-related modeling, optimization, monitoring, or assessment functions that support carbon mitigation in industrial symbiosis contexts. This interpretation aligns with the paper’s objective of mapping data-driven tools supporting the integration of industrial symbiosis and carbon mitigation strategies.

A systematic search was conducted in Scopus, Web of Science, and IEEE Xplore, covering publications from database inception to January 2026. The final search was executed in January 2026 and includes all publications indexed up to 18 January 2026. The search string combined keywords related to industrial parks, energy/carbon, and symbiosis. Boolean operators (AND, OR) and filters (English language, peer-reviewed articles) were applied to refine the results. The draft search strategy was reviewed by experts in industrial symbiosis to ensure completeness.

The search string used was as follows:

TI = (energy OR electricity OR heat* OR carbon OR CO2) AND (“industrial park” OR “commercial park” OR “industrial area” OR “commercial park”) AND (symbiosis OR mutual* OR “eco-industrial” OR “industrial ecology” OR synerg* OR co-* OR integration OR sustainabl* OR ecosystem OR collaboration).

No additional automation tools were used to exclude studies. All records were screened manually based on the eligibility criteria.

Studies were imported into EndNote for reference management, where duplicates were removed. The study selection followed a PRISMA-consistent process comprising identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and inclusion. First, titles and abstracts were screened against the eligibility criteria. Second, full texts were assessed to confirm final inclusion. Third, reasons for exclusion at the full-text stage were documented and summarized in the PRISMA flow diagram categories. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion or by consulting a third reviewer.

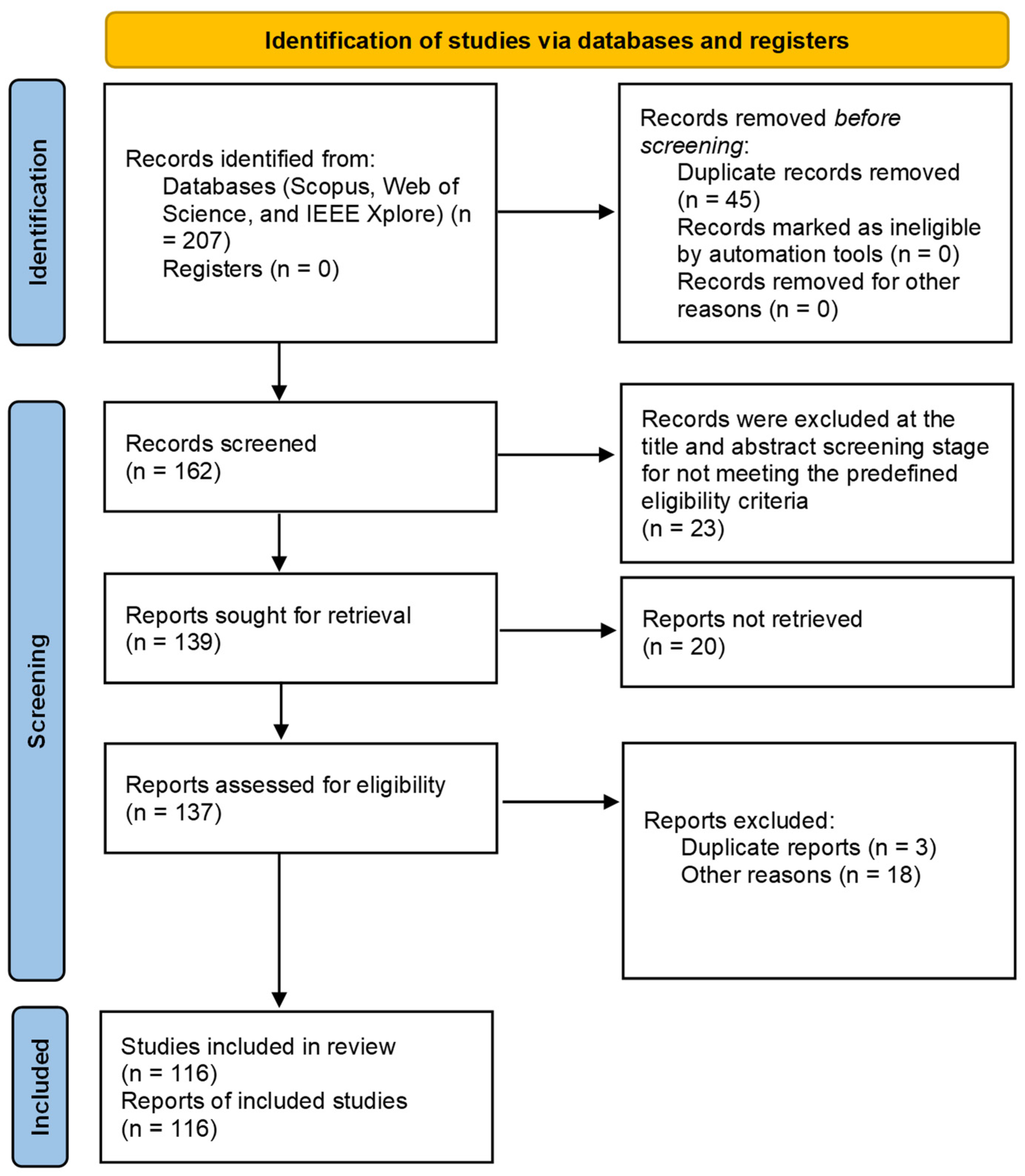

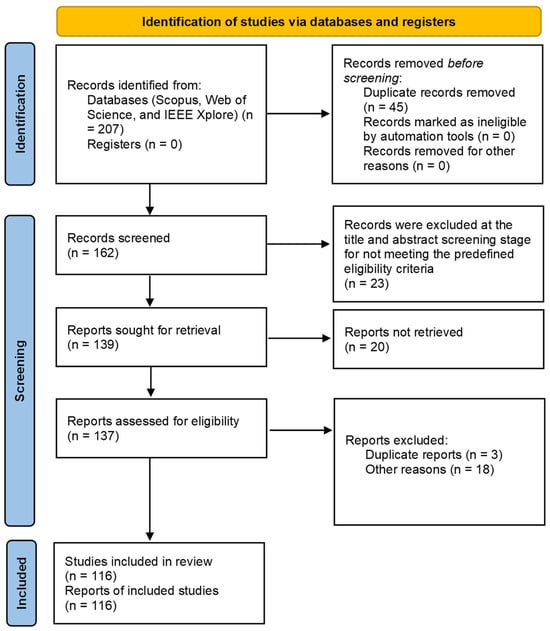

In total, 239 records were identified across the databases. After duplicate removal (n = 67), 172 unique records remained for title and abstract screening. Of these, 53 records were excluded for failing to meet the eligibility criteria. The remaining 119 records were subjected to full-text assessment, and all were confirmed as meeting the inclusion criteria. Therefore, the final dataset comprises 119 studies (as shown in Table A1 in the Appendix A), which form the basis of the scoping review. The identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and inclusion process are summarized in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The PRISMA flow diagram.

A standardized data extraction form was piloted on a subset of studies to ensure consistency and comprehensiveness. Two independent reviewers used this form to extract relevant data, including study focus, methodology, key findings, and contextual details. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion, and a third reviewer was consulted when necessary. Consistent with PRISMA-ScR guidance, no formal risk-of-bias or quality assessment was conducted, as the purpose of the review was mapping and synthesis rather than evidence grading.

The final dataset captured multiple dimensions of industrial symbiosis tools and methods, such as simulation models, econometric analyses, optimization frameworks, data collection instruments, decision-making approaches, and sustainability assessments. Table 2 provides an overview of the data charted.

Table 2.

Data items chart.

A thematic analysis identified recurring patterns and trends in the literature, such as common simulation and optimization tools (e.g., Aspen Plus, Mixed-Integer Linear Programming), prevalent industrial settings (e.g., eco-industrial parks), and stakeholder considerations. Contextual analysis examined how these approaches applied to specific industrial scenarios, highlighting unique challenges (e.g., confidentiality in data sharing) and potential benefits (e.g., cost savings, emission reductions). These synthesized results form the basis of the literature review results reported in Section 3.1.

Furthermore, findings were mapped to the research question concerning the diversity of methods/tools for integrating industrial symbiosis and carbon capture, as well as the key factors influencing their success or challenges. The synthesis illuminates frequently used strategies (e.g., simulation models, optimization tools) that can enhance the environmental and economic performance of industrial parks.

2.2. Survey Design and Data Collection

To complement the scoping literature review, a structured practitioner survey was conducted under the IEA IETS Task 21 initiative to investigate the practical use, perceived effectiveness, scalability, and implementation challenges of industrial symbiosis and carbon capture tools. The survey was explicitly designed as an exploratory instrument to contextualize and validate literature-based findings, rather than as a statistically representative study. Its purpose is to capture practitioner perspectives that are typically underreported in academic publications, particularly regarding usability, adoption barriers, and governance-related constraints.

A survey-based approach was selected because industrial symbiosis and carbon capture tools are often developed, tested, and applied by a limited number of highly specialized actors. In such contexts, in-depth expert elicitation is more appropriate than large-sample surveys, as it enables the collection of experience-based insights across the full tool lifecycle, including development, application, and implementation. Therefore, the survey serves a complementary and explanatory role alongside the scoping review.

The survey instrument was developed after completion of the literature review to ensure alignment between the identified tool categories and the survey questions. The full set of survey questions is provided in the Supplementary Materials, and the survey structure closely mirrors the analytical dimensions used in the literature review, enabling systematic triangulation between literature and practitioner evidence.

The survey was structured into six sections:

- Respondent profile, capturing affiliation, position, expertise, years of experience, and role in relation to the tool or method.

- Basic information on tools and methods, including functionality, scope, licensing, and technology readiness level.

- Functions and purpose, covering analytical, modeling, simulation, optimization, and control capabilities.

- Application and implementation, addressing deployment contexts, operational scale, and managed resource types.

- Development and evolution, focusing on adaptability, future development plans, and stakeholder involvement.

- Familiarity and perception of industrial sustainability practices, including perceived benefits, barriers, and organizational priorities.

A summary of the questionnaire structure and question logic is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Structure and thematic focus of the practitioner survey questionnaire.

The survey was distributed online, targeting practitioners, researchers, and industry stakeholders with direct experience in industrial symbiosis and carbon capture tools. Participants were selected using purposive expert sampling, targeting individuals actively involved in tool development, application, or evaluation within research institutions and applied industrial projects associated with the IEA IETS Task 21 network. This sampling strategy prioritizes depth of expertise over breadth of representation and aligns with exploratory studies in emerging, highly specialized research domains.

A total of eight respondents completed the survey. Although numerically limited, the participant group demonstrates a high level of domain expertise and diverse roles. Respondents were primarily affiliated with academic and applied research institutions and included senior researchers, PhD researchers, and research associates. Their expertise spans software engineering, system innovation, industrial energy transformation, hydrogen technologies, carbon capture and utilization, methanation, energy optimization, and the facilitation of industrial symbiosis. Participants represent early-, mid-, and senior-career researchers, with experience ranging from less than 5 years to more than 10 years. A detailed demographic summary of respondents’ affiliations, positions, expertise, and experience is reported in Table 13 in Section 3.2.

The limited sample size is a recognized limitation of the survey and reflects the current concentration of expertise in industrial symbiosis and in the development of carbon capture tools. The survey is not intended to support statistical generalization; instead, it provides qualitative and descriptive quantitative insights that complement and contextualize the scoping review results.

Each survey required approximately 10–15 min to complete. Responses included a combination of structured multiple-choice questions and open-ended qualitative inputs. To enhance content validity, survey questions were derived directly from categories and gaps identified in the literature review, ensuring conceptual consistency between the two methods. The survey instrument was reviewed internally by domain experts prior to dissemination to ensure clarity, relevance, and completeness.

Given the exploratory nature of the survey and the small expert sample, formal statistical reliability testing was not performed. However, several measures were applied to enhance reliability and interpretive robustness. These include standardized question wording, consistent response scales, and cross-validation of practitioner responses against patterns identified in the literature review. Convergence between survey responses and literature findings is explicitly examined in Section 4, thereby strengthening analytical credibility through methodological triangulation.

Survey responses were coded and analyzed using descriptive statistics and thematic analysis. Quantitative responses were summarized using frequency counts and simple association tests where appropriate, while qualitative responses were analyzed to identify recurring themes related to tool usability, adoption barriers, data requirements, and governance challenges. The analytical focus is on pattern identification rather than hypothesis testing, consistent with the survey’s exploratory intent.

The survey analysis focuses on the following aspects:

- Alignment between tool functionality and industrial symbiosis and carbon capture objectives.

- Barriers related to data availability, confidentiality, regulation, cost, and interoperability.

- Perceived contributions to resource efficiency and carbon reduction.

- Opportunities for tool enhancement and supporting policy mechanisms.

The survey results are presented in Section 3.2 and interpreted in conjunction with the literature review in Section 4.

3. Results

This section presents the results of the study in two complementary parts, reflecting the dual-method research design. Section 3.1 reports the results of the PRISMA-guided scoping literature review, synthesizing publication trends, geographic distribution, tool and method classifications, implementation contexts, and stakeholder roles based on the analyzed corpus. Section 3.2 presents the practitioner survey results, providing empirical insights into tool usage, perceived maturity, implementation challenges, and adoption conditions in real-world industrial contexts.

3.1. Literature Review Results

Industrial symbiosis has emerged as a vital strategy for enhancing resource efficiency, reducing emissions, and fostering circular economy goals in industrial parks. This section synthesizes findings from a scoping review of 119 studies, capturing broad trends in publication outputs, technological developments, and stakeholder contributions from 2006 to 2025. To improve interpretability, key descriptive patterns are reported with explicit counts and percentages, and each table is accompanied by a short analytical interpretation of what the mapped methods imply for tool maturity, deployment readiness, and remaining research gaps. Emphasis is placed on the evolution of research, the geographic scope of industrial symbiosis initiatives, and the array of tools and methods employed for resource optimization, decision-making, and sustainability assessment.

3.1.1. Evolution of Industrial Symbiosis Research

- Publication Trends

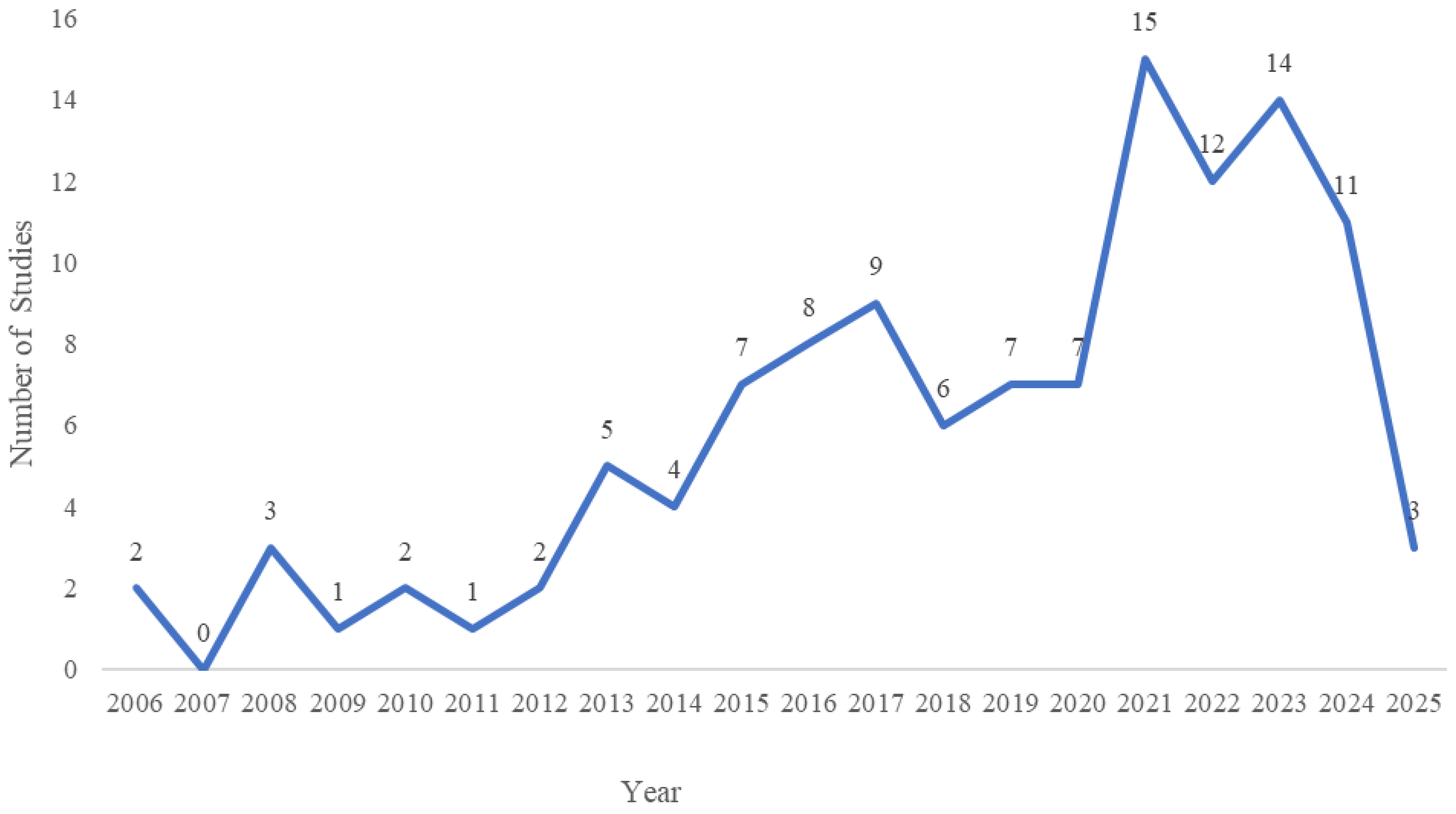

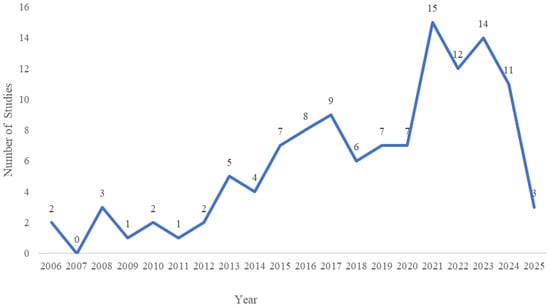

The scoping review indicates a generally upward trajectory in industrial symbiosis publications from 2006 to 2025 (Figure 3). The trend is characterized by a low-volume early phase from 2006 to 2012, followed by accelerated growth after 2013 and a peak in 2021 with 15 studies. This increase reflects the growing recognition of industrial symbiosis as a key approach to mitigating resource scarcity and climate change, while advancing circular economy principles [1]. Notably, the period 2021–2025 accounts for 55 of 119 studies, representing approximately 46.2 percent of the included literature, indicating that the evidence base is recent and rapidly expanding. The scoping review result also shows the following fields that have been prioritized over the years: inter-firm collaborations, waste valorization, and integrated energy solutions that lower environmental impacts and promote economic gains within industrial parks. However, the year-by-year pattern shows fluctuations rather than linear growth, implying sensitivity to policy cycles, demonstration funding, and national decarbonization programs that tend to drive bursts of applied research.

Figure 3.

Number of included studies per year, 2006–2025, based on the 119-study scoping review dataset.

Figure 3 shows that annual publications remain low before 2013, then increase markedly, reaching 15 studies in 2021, followed by 12 studies in 2022, 14 studies in 2023, 11 studies in 2024, and 3 studies in 2025. The lower count in 2025 reflects partial-year coverage up to January 2026 rather than a substantive decline in research activity. This concentration of output in recent years suggests that industrial symbiosis tool development has shifted from conceptual framing toward implementation-oriented modeling and assessment, likely influenced by national net-zero targets and eco-industrial park programs. At the same time, the post-2021 fluctuation indicates that the evidence base is shaped by program cycles and case-study availability rather than steady linear growth, which has implications for the transferability of reported results across regions and sectors.

- Geographic Distribution

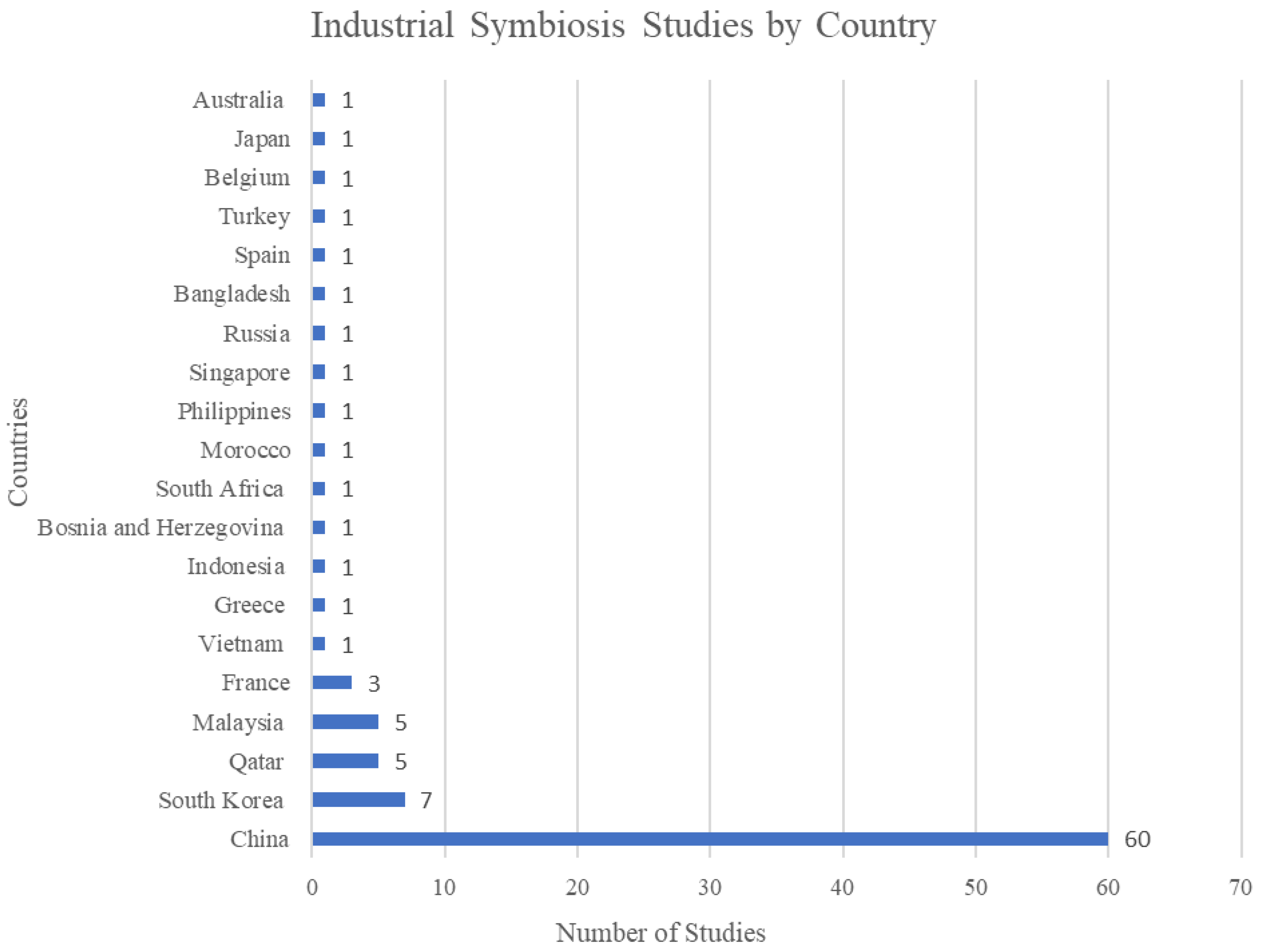

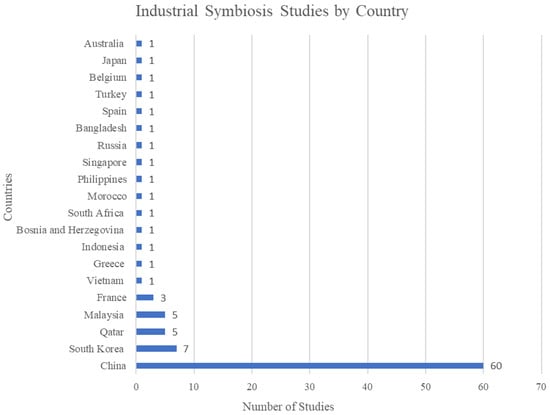

Analysis of the 119 selected studies revealed that 95 reported specific locations. Figure 4 illustrates how China leads in the number of publications. Among the location-reported studies, China accounts for 60, indicating a highly skewed geographic evidence base. This concentration implies that reported tool usage patterns, data availability assumptions, and governance models may disproportionately reflect contexts with stronger state-led eco-industrial park programs and more mature industrial data infrastructures. As highlighted by [2], such systemic conditions—particularly integrated governance structures and coordinated data management—are critical enablers for energy–water–food–carbon nexus implementation in eco-industrial parks, and are not uniformly present across regions. Consequently, evidence on tool deployment barriers in regions with weaker institutional capacity or limited data-sharing mechanisms may be underrepresented in the current literature.

Figure 4.

Distribution of included studies by country for the subset of studies reporting a specific study location, n equals 95.

However, industrial symbiosis has also attracted considerable interest across Asia (South Korea, Malaysia, Qatar, Singapore, the Philippines, Japan, Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Vietnam) and Europe (France, Russia, Turkey, Greece, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Belgium, and Spain), with additional initiatives reported in Australia and Morocco. This geographic concentration suggests that the literature is shaped not only by technical need but also by institutional capacity, availability of industrial data, and sustained public programs that support eco-industrial park experimentation. A further implication is that evidence on tool adoption and governance may be overrepresented in regions with mature park programs and underrepresented in contexts where data access, investment, or institutional coordination are weaker.

3.1.2. Classification of Tools and Methods Supporting Industrial Symbiosis

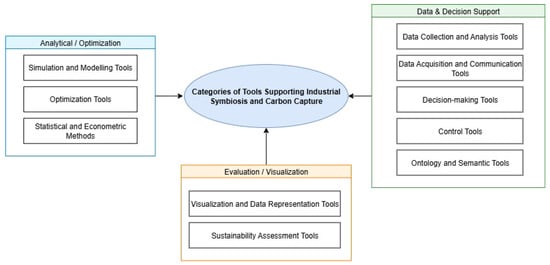

The reviewed literature reveals a diverse range of tools and methods aimed at facilitating resource sharing, optimizing energy use, managing data, and informing decision-making in industrial symbiosis. These technologies span from simulation platforms and econometric models to optimization frameworks, data analysis instruments, decision-support systems, and sustainability assessment techniques. Where the included studies explicitly report software, solvers, or named methods, frequency patterns are synthesized qualitatively in the narrative to distinguish dominant tool families from underrepresented capabilities, rather than treating all tools as equally prevalent. Across the mapped tool landscape, two cross-cutting patterns are apparent. First, a substantial share of methods emphasize planning, optimization, and performance assessment. Second, comparatively fewer studies operationalize interoperability, semantic integration, or governance-oriented digital mechanisms, even though these factors are repeatedly identified as barriers to real-world implementation. This imbalance indicates that methodological maturity in analytical optimization has advanced more rapidly than the socio-technical mechanisms required for large-scale deployment.

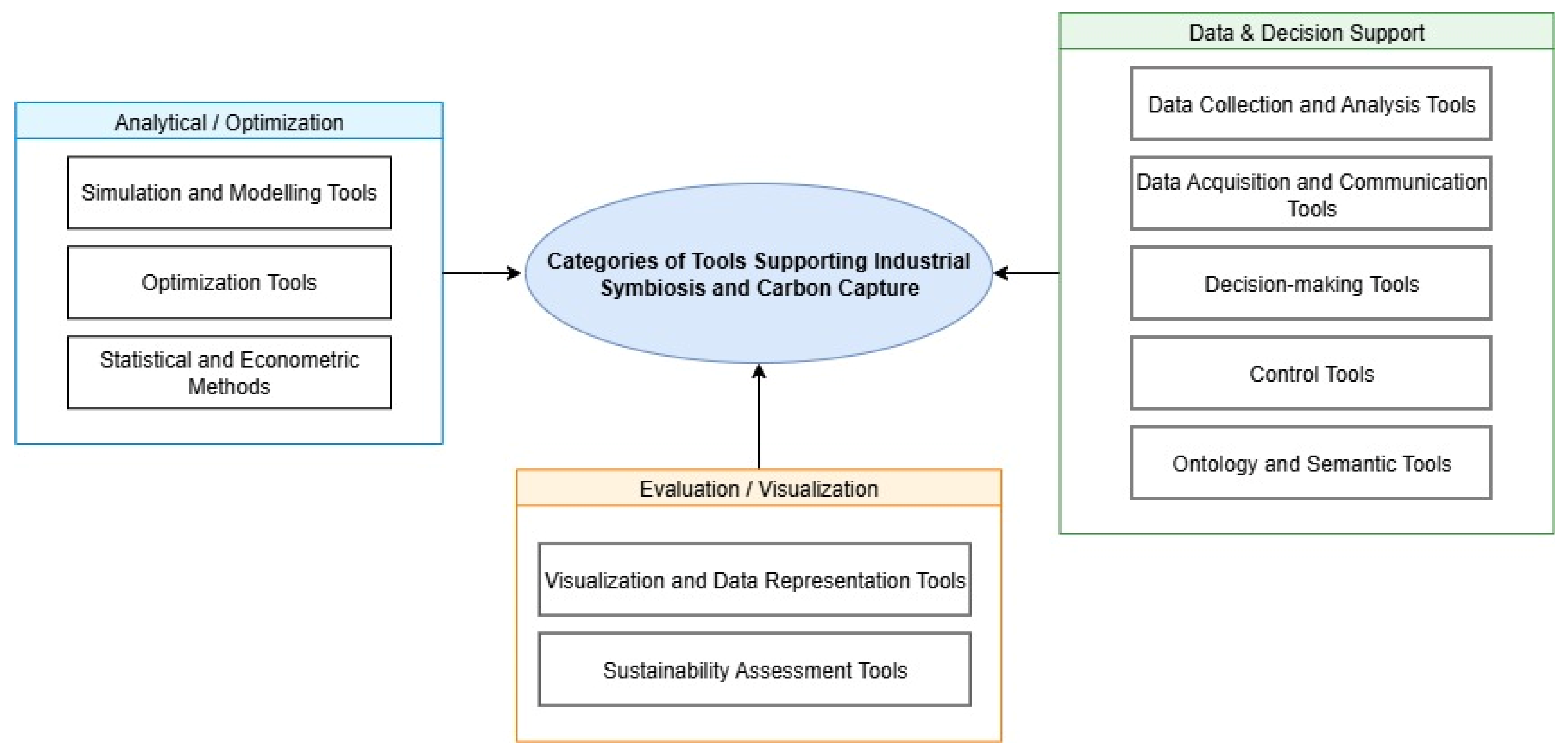

To provide a clearer conceptual overview, Figure 5 groups these methods into three overarching clusters. Analytical and Optimization tools include simulation and modeling platforms, optimization frameworks, and econometric approaches that help design and optimize industrial symbiosis systems. Data and Decision Support tools encompass data collection and communication techniques, decision-making frameworks, control tools, and ontology-based approaches that ensure real-time monitoring, coordination, and structured knowledge management. Evaluation and Visualization tools include sustainability assessment and visualization techniques that quantify environmental, social, and economic impacts while illustrating flows and synergies across actors. References to each table (Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8, Table 9, Table 10 and Table 11) in this section offer an overview of methodologies and their industrial applications. Across the optimization-oriented literature summarized in Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5, MILP and related mathematical programming formulations recur across multiple case studies as the dominant family of approaches for park-level coordination, whereas ontology-based and semantic interoperability methods appear only sporadically, highlighting a structural gap between analytical tool development and deployment-oriented data integration.

Figure 5.

Classification of Data-Driven Tool Categories Supporting Industrial Symbiosis and Carbon Capture in Industrial Parks.

Table 4.

Simulation and modeling tools used to analyze energy, material, and carbon flows in industrial symbiosis and eco-industrial park studies.

Table 5.

Statistical and econometric methods applied to evaluate policy impacts and performance of industrial symbiosis and eco-industrial parks.

Table 6.

Optimization methods and tools used for resource allocation, energy integration, and emission reduction in industrial symbiosis systems.

Table 7.

Data collection and analysis tools supporting monitoring, modeling, and decision-making in industrial symbiosis and carbon-related applications.

Table 8.

Decision-making methods used for scenario analysis, stakeholder coordination, and planning in industrial symbiosis contexts.

Table 9.

Visualization and data representation tools used to communicate resource flows and system interactions in industrial symbiosis.

Table 10.

Ontology-based and semantic tools supporting data interoperability and knowledge representation in industrial symbiosis systems.

Table 11.

Sustainability assessment methods used to evaluate environmental, economic, and social performance of industrial symbiosis and carbon-related systems.

- Simulation and Modeling Tools

Simulation and modeling platforms enable the design and validation of industrial symbiosis scenarios under realistic conditions [12]. Table 4 provides a list of commonly adopted tools, such as HOMER [20,21,22]. Other energy simulation and modeling tools identified in studies include EnergyPLAN [23] and EMB3Rs [24], which addresses microgrids, energy planning, and waste-heat recovery.

Mathematical models capture multi-energy systems, allowing users to explore constraints, optimize resource allocation, and simulate real-time operations [25,26]. These models also address the interactions within energy–water–food–carbon (EWFC) systems [2] and industrial parks, including energy generation, storage, demand, and balance [27]. They are crucial for integrating renewable energy sources into energy systems [28], analyzing energy consumption and savings in industrial chains [29]. Additionally, they play a key role in evaluating resource utilization and economic benefits in industrial symbiosis [30,31].

Recent studies also applied simulation environments such as AnyLogic to test energy–production scheduling in eco-industrial parks [32], while life cycle tools such as SimaPro (ReCiPe) were used to evaluate pollution–carbon synergies [33]. Similarly, LEAP was employed to simulate decarbonisation pathways in Zhejiang and Shandong eco-industrial parks [34,35].

Process simulators optimize industrial and energy systems. For example, Aspen Plus is employed to simulate biorefinery scenarios [36], optimize energy conversion systems (ECR) [37], analyze system performance [38], and simulate chemical processes to obtain data on waste heat and heating demand for plants and communities [39]. Aspen HYSYS is used to simulate various industrial processes, collect data on mass and energy flows, contaminant concentrations, and economic parameters, and monitor water usage and contaminants in processes like GTL and ammonia production [40]. Meanwhile, ProSimTM analyzes the performance of thermal systems, focusing on thermal efficiency and heat recovery [41], while AVEVA PRO/II is a steady-state simulator used to optimize process performance, like modeling the ALPG system [42].

Programming environments like MATLAB and Vensim support dynamic or real-time validations [43]. MATLAB, for example, is used to simplify complex models, such as fitting transportation costs into a simplified formulation [37], and to simulate power flow forecasting and charging processes using MATLAB/Simulink [44]. Additionally, MATLAB supports optimization techniques like the Generalized Reduced Gradient (GRG) algorithm [39] and is applied in the simulation and analysis of park-level microgrids [45]. On the other hand, Vensim simulates and analyzes the dynamic behavior of systems over time [43]. Moreover, Monte Carlo simulation approaches [8], RTDS Simulation Platforms [12], and Digsilent PowerFactory handle uncertainties and grid complexities [46].

Collectively, the simulation and modeling tools listed in Table 3 reflect a strong emphasis on engineering feasibility and performance estimation. Their value lies in enabling scenario exploration and techno-economic assessment, but they typically assume that high-quality process and energy flow data are available and shareable across firms. This assumption becomes a limiting condition for adoption in industrial symbiosis settings where data confidentiality and heterogeneous data formats are common.

Carbon capture modeling gap. Despite the prominence of process simulation tools for emissions and material-flow modeling, relatively few studies explicitly simulate carbon capture technology pathways, such as absorption, adsorption, amine scrubbing, membrane separation, or oxy-fuel combustion, as integrated subsystems within industrial symbiosis networks. Catalytic methanation appears as a carbon capture-related pathway, but other capture options are rarely modeled in industrial symbiosis contexts. This gap suggests that future tool development and review synthesis should more systematically connect carbon capture technology representation to industrial symbiosis toolchains and data requirements.

- Statistical and Econometric Methods

Statistical and econometric methods are used to evaluate initiatives like eco-industrial parks (EIPs) and their impact on emissions and environmental outcomes (as shown in Table 5). Studies employ econometric software to support statistical and econometric analysis [47], while tools like Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) incorporate climate change data for augmentation [42]. Methods such as Welch’s t-test (95% confidence interval) validate models like CC-VRES [42], while linearity tests justify the use of nonlinear models by assessing variable relationships [47]. J-tests ensure appropriate model specifications [47], and Significance Tests determine the reliability of model coefficients [47].

Difference-in-Differences (DID) methods, including multi-period [48], staggered [49], and spatial approaches, measure the causal effects of eco-industrial parks on emissions and their spillover impacts [50]. These methods deliver statistically robust evidence on how and whether eco-industrial park policies meet greenhouse gas reduction objectives. Consistent with this, spatial DID and DID have been applied to assess the effect of China’s National Demonstration Eco-Industrial Parks on urban carbon-emission efficiency across 282 cities [51], while Tobit regression has been used (with DDF-DEA) to examine green-development efficiency and policy drivers at park and enterprise levels [34].

The econometric toolset indicates that a policy-evaluation stream has matured alongside the development of engineering tools. Unlike simulation-based studies, which often focus on technical feasibility, econometric studies can support causal inference into the effects of eco-industrial park designation and related policies. However, these studies typically operate at aggregated spatial or sectoral levels and therefore provide limited operational guidance on tool selection, system integration design, or data governance mechanisms required for firm-level adoption.

- Optimization Tools

Linear Programming (LP) and Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) are optimization methods for solving complex problems, especially in energy systems (shown in Table 6). Multi-period and successive MILP models address time-dependent operational and utility decisions [5]. MILP is widely used to minimize energy costs, design sustainable clusters, optimize energy networks, and reduce GHG emissions through energy symbiosis [52]. It also evaluates the economic benefits of energy exchanges in eco-industrial parks and integrates renewable energy, achieving up to 97% potential emission reduction [53]. Furthermore, MILP supports the design of cost-efficient hybrid power systems and enhances both economic and environmental performance [54]. MILP is also applied to determine optimal solutions and operating strategies for multi-energy systems [55]. These models are commonly solved using GAMS, IBM ILOG CPLEX, and LINGO [56]. For MINLP problems, GAMS combined with the BARON solver is frequently employed [57]. AIMMS provides solvers such as CONOPT for NLP and MILP optimization [58,59]. Meanwhile, What’s Best! by LINDO Systems integrates with Microsoft Excel to handle objectives such as profit maximization, cost minimization, and energy/CO2 integration in eco-industrial parks [60].

Mixed-Integer Nonlinear Programming (MINLP) extends optimization capabilities to highly complex energy systems, including renewable integration in eco-industrial parks [4] and sustainable energy–water–food–carbon networks [2]. MINLP applications include optimizing heat and material stream integration in a natural gas industrial park—achieving a 30.5% reduction in hot utility consumption [53], and minimizing total annualized costs in trigeneration and heat exchanger networks where fuel input deviations significantly increased costs [3].

Multi-agent Energy Management Systems (EMS) and consensus-based algorithms optimize Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) in DC microgrids within industrial parks [61]. Bi-level optimization frameworks model decision-making processes involving two levels with conflicting objectives [13], while the Bi-level Fuzzy Programming Model incorporates flexibility and uncertainty into these objectives [10].

Heuristic and metaheuristic methods address complex energy optimization problems. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) is used for energy dispatch [62], storage allocation [63], and management strategies for large users [64]. Variants like the Improved Second-Order Oscillating PSO [26] and Adaptive Modified PSO (AMPSO) [65] enhance microgrid operation planning. Genetic algorithms (GA), including improved GA (IGA) [66] and NSGA-II for multi-objective problems [67], optimize operating schedules and tackle multi-objective energy challenges. Recent 2025 evidence further illustrates the continued relevance of multi-objective optimization for eco-industrial park restructuring. In particular, an NSGA-II-based multi-objective optimization framework was applied in [68] to evaluate trade-offs between economic output, carbon mitigation, and pollution reduction in a real eco-industrial park, demonstrating how optimization supports simultaneous decarbonization and waste-management strategies at the park scale.

Stochastic and decomposition-based methods handle uncertainty and boost efficiency: stochastic programming manages renewable and demand variability, dual decomposition simplifies problems, and FISTA speeds up real-time optimization [27]. Meanwhile, the electricity pricing strategies include peak–valley and time-of-use models, which reduce microgrid costs in industrial parks [69,70]. An optimal sizing scheme further determines equipment parameters for new energy islands [1].

Total Site Analysis (TSA) improves park-wide systems by assessing energy use, savings, and cross-process heat integration [15]. Analysis optimizes energy efficiency, heat exchange, and resource use, supporting carbon planning, thermal management, and waste-to-resource strategies [71]. Additionally, park-level integrated energy systems determine economical and environmentally sustainable energy plans for industrial parks [17].

In line with these trends, IBM ILOG CPLEX has been applied as a constraint programming solver for mixed energy production scheduling in eco-industrial parks [32], Gurobi has been used to optimize integrated electricity–heat systems [72], Excel Solver has supported multi-objective structural adjustment under pollution–carbon constraints [73], and ACTA (Automated Composite Table Algorithm) has enabled CO2 allocation network design [74]. Complementing these solver-centered approaches, [75] develops a nonlinear programming model in Python for peer-to-peer multi-energy trading in an eco-industrial park and implements ADMM as a decentralized coordination mechanism to clear the thermal energy market under network and storage constraints, highlighting the role of distributed optimization in preserving privacy while improving overall system performance.

The dominance of MILP and related optimization formulations indicates that industrial symbiosis research strongly prioritizes optimal resource allocation and cost minimization under constraints. However, optimization models typically embed strong assumptions about coordination, centralized decision authority, and data availability. In practice, adoption depends on governance arrangements that enable data sharing and agreement on objective functions, which are rarely modeled explicitly. This gap implies that future work should integrate optimization formulations with interoperability and governance mechanisms, especially when carbon capture is introduced as an additional coupled subsystem.

- Data Collection and Analysis Tools

Effective industrial symbiosis depends on rich and reliable datasets. Table 7 reveals how surveys, interviews, and literature reviews capture both quantitative and qualitative dimensions of energy consumption, environmental performance, and operational efficiency [76]. Least squares regression quantifies load-curve impacts [69], while correlation and regression analyses map the relationship between eco-industrial park policies and enterprise competitiveness [77].

Some studies employ sensor-based monitoring, EV data logging [44], and SCADA measurements to facilitate real-time optimization [78] thereby enabling continuous improvements in eco-industrial strategies. In addition, multi-source industrial and pollutant datasets have been collected and preprocessed to calibrate optimization models for pollution–carbon synergy pathways [73].

Data collection and monitoring tools highlight that industrial symbiosis tools are conditional on data accessibility and standardization. The literature increasingly recognizes the role of real-time monitoring and integrated datasets, yet many studies treat data as an available input rather than as a governance and interoperability challenge. This pattern strengthens the interpretation that data infrastructure is not a secondary implementation detail but a central determinant of whether advanced modeling and optimization tools can be deployed in practice.

- Decision-Making Tools

Decision-making tools use data as input but are primarily designed for modeling scenarios or decision-making (as shown in Table 8). For instance, performance metrics assess key factors (e.g., energy costs, electricity exchange, storage levels, and emissions) to determine the effectiveness of optimization approaches [8]. Eco-industrial park studies have also applied performance metrics such as energy-utilization ratio and scheduled-job ratio to compare scheduling strategies [32]. Sensitivity analysis is conducted to understand how changes in parameters like electricity prices, energy storage usage, and investment costs impact the economic performance of different scenarios [79]. Sensitivity analysis has also been used to test the effect of storage investment ratios on integrated energy systems in the eco-industrial parks [72]. Scenario analysis explores the effects of varying assumptions and conditions on energy consumption, economic growth, and network design [80,81]. Furthermore, scenario analysis has also been used to evaluate different load-ratio cases, external waste-heat utilization, and decarbonization pathways at the park scale [35,82].

Additionally, Game Theory [64] and Cooperative Game Theory (Maali’s Method) [83] are utilized to analyze strategic decision-making among agents and determine fair cost allocations in scenarios involving multiple stakeholders. The Shapley value calculation is also used in cooperative game theory to allocate cost savings among participating companies [59]. Furthermore, the WAR GUI and Inherent Safety Index (ISI) calculation assess the environmental impact and safety of processes [36], while steam system composite curves offer insights into steam generation and recovery opportunities within utility systems [15].

Decision-oriented methods represent a bridge between technical optimization and stakeholder negotiation because they explicitly surface trade-offs, uncertainty, and fairness. However, their practical impact depends on whether stakeholders accept shared metrics and whether decision authority is sufficiently coordinated. This suggests that decision-support value is highest when combined with governance mechanisms that legitimize data sharing and collective action.

- Data Acquisition and Communication Tools

Data acquisition systems gather live information from industrial assets, including PV inverters and storage modules [25,62]. Communication networks allow real-time feedback to optimize algorithms, yielding coordinated energy flows that minimize operational costs and lessen ecological footprints. These systems underscore the transition toward digitalized, interconnected industrial frameworks necessary for comprehensive symbiosis [25,62].

- Control Tools

Control solutions handle real-time dispatch, load balancing, and energy flow coordination. Model Predictive Control (MPC) forecasts near-future demand to refine plant scheduling [62], and multi-agent systems (MAS) distribute control intelligence among autonomous components [84]. Such approaches to safeguard grid stability and resilience when intermittent renewables supply a significant share of the industrial park’s energy [84,85].

- Visualization and Data Representation Tools

GIS-based tools are widely used in the reviewed literature to map renewable energy potential [86], analyze eco-industrial park distribution [49], and link energy consumption with spatial data [87]. In the reviewed studies, ArcGIS is commonly employed to identify PV-suitable roofs, analyze network data [46], assesses heat sources and industrial–urban symbiosis configurations [88], and evaluates industrial parks’ water and solar potential [76]. GIS-based visualization is also used to illustrate supplier–customer energy exchanges [58]. Tools such as e!Sankey are applied to depict carbon flows in industrial symbiosis systems [16]. IIn addition, spatial maps are used to show eco-industrial park locations and energy infrastructure [89], while network diagrams illustrate sectoral interconnections [31].

Advanced tools like Grassman and Energy Utilization Diagrams (EUDs) analyze energy/exergy flows [38], while Grand Composite Curves (GCCs) and Site Source–Sink Profiles (SSSPs) visualize heat integration for Total Site Analysis (TSA) [15,53]. GEPHI visualizes IS networks [90], and Network Allocation Diagrams (NADs) optimize carbon distribution [71]. Park-wide multi-energy flows have also been represented with Sankey-style energy-flow diagrams to compare cases and communicate system operation [82].

Visualization tools shown in Table 9 are essential for stakeholder engagement and early-stage opportunity identification because they make exchange relationships intelligible. Their limitation is that visualization alone rarely resolves confidentiality constraints or produces implementable operating strategies. This suggests a need for hybrid toolchains that connect visualization to optimization and to secure data-sharing mechanisms.

- Ontology and Semantic Tools

Ontology-based approaches (shown in Table 10) build a shared vocabulary and data structure for eco-industrial systems. Protégé is used for creating, visualizing, and editing domain and application ontologies [91,92]. Apache Jena Fuseki serves as a local host for publishing and storing these ontologies, while the SPARQL Protocol and RDF Query Language enable efficient data retrieval from RDF-formatted ontology databases [91]. Additionally, Agent Communication Language (ACL) supports communication and information exchange between agents in decentralized Energy Management Systems (EnMS) [84].

Ontology and semantic tools directly address interoperability and structured data exchange, yet they remain less prominent in the overall tool landscape than simulation and optimization. This imbalance indicates that the literature may overinvest in analytical sophistication relative to the socio-technical prerequisites for tool integration, particularly common data models and governance for shared semantics.

- Sustainability Assessment Tools

Sustainability assessment tools/methods (shown in Table 11) cover the environmental, social, and economic impacts of industrial symbiosis projects. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) quantifies the environmental impacts of supply chain stages and evaluates the benefits of industrial symbiosis systems compared to non-symbiotic baselines [7] and has also been extended through life-cycle-based synergy evaluation (LCA-SE) to measure joint pollution–carbon effects at the industrial-park scale [33].

Meanwhile, Material Flow Analysis (MFA) maps material flows, identifies industrial symbiosis opportunities, and measures resource savings and waste reduction [81]. Social dimensions are addressed through Social Impact Assessments (SIA), which evaluate the consequences of supply chain options, including job creation and community health impacts [93]. Sustainability Metrics, including the Sustainability Weighted Return on Investment Metric (SWROIM), assess economic, environmental, and social performance [40].

Advanced analysis methods include the Logarithmic Mean Divisia Index (LMDI) for decomposing carbon emission changes [94,95], and Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) to measure the efficiency of industrial entities [96]. Recent applications combine DDF-DEA with Tobit regression to evaluate green-development efficiency and to identify structural and policy determinants, while Tapio decoupling and coupling-coordination degree (CCD) models have been applied to assess coordination between economic growth, pollution reduction, and carbon mitigation at the park scale [34].

Recent 2025 studies further extend sustainability assessment from retrospective evaluation toward implementation-relevant quantification. In particular, [97] proposes an evaluation framework to quantify the carbon emission reduction potential of industrial symbiosis in industrial parks by distinguishing different symbiosis modes, such as waste reuse, energy cascade, and infrastructure sharing, and validating their approach through a real industrial park case study. This work illustrates how sustainability assessment methods can support prioritization of industrial symbiosis pathways rather than only ex-post performance comparison.

Moreover, Ward’s Hierarchical Clustering Method groups industrial parks with similar industrial structures to analyze eco-efficiency patterns [98]. Social Network Analysis (SNA) identifies key nodes and vulnerabilities in industrial symbiosis networks [90], often supported by tools like UCINET 6 Software. Remote sensing aids in identifying renewable energy potential, such as wind and solar resources [42]. Steam System Composite Curves visualize steam generation, consumption, and recovery [52]. Specialized software such as SimaPro for LCA modeling [52] and the Slack-Based DEA Model for eco-efficiency analysis [98] enhances precision and depth in evaluating eco-industrial park systems.

Sustainability assessment methods strengthen claims of environmental and economic value, but they often remain retrospective or evaluative rather than prescriptive. This limits their direct utility for tool selection and operational deployment. A practical implication is that assessment methods should be increasingly coupled with decision-support pipelines that translate evaluation outputs into implementable investments and operating strategies under real-world governance constraints.

- Additional Methods and Tools

Other tools and methodologies applied to industrial symbiosis studies are identified (shown in Table 12). Java-based applets, for example, provide user interfaces for interacting with systems like J-Park Simulator (JPS), while sensor and actuator networks collect real-time data and implement decisions [91]. Advanced programming tools, such as the Digsilent Programming Language (DPL), enable custom algorithm development for simulation automation [46]. Geographic insights are obtained through GIS tools like ArcGIS for mapping plants and communities [39]. Material analysis is enhanced by Thermo-Gravimetric/Differential Thermal Analysis (TG/DTA) to measure CO2 content in fly ash and X-ray Powder Diffraction (XRD) to identify mineral transformations [99]. Energy system models, such as the gas turbine combined system and thermodynamic property equations (Peng-Robinson, Steam Table, Redlich–Kwong), assess efficiency and working fluid properties [38]. Data storage and processing are facilitated by a central database for company data management [6] and Big Cloud Moving Smart Technologies for advanced analysis [100]. Real-time operations leverage an IoT Management Platform connected via Power Optical Fiber and 5G networks [100]. Interfaces such as human–machine systems allow operators to monitor and control microgrid performance [25]. Decision support tools include Multi-Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) for evaluating trade-offs among solutions [5], and Adversarial Autoencoders (AAE) and SHAP explanations for analyzing energy models and reducing data dimensionality [42].

Table 12.

Supporting computational and digital tools complementing core modeling and optimization methods in industrial symbiosis research.

3.1.3. Implementation Contexts in Industrial Symbiosis

The successful implementation of industrial symbiosis depends on diverse operational contexts, ranging from eco-industrial parks and conventional industrial parks to specialized sectors such as petrochemicals, agriculture, and fisheries. Each of these contexts presents unique opportunities and challenges, influencing the effectiveness, scalability, and adaptability of industrial symbiosis frameworks.

- Eco-Industrial Parks

Eco-industrial parks [101,102,103] incorporate collaborative waste management, shared utilities, and synergy-based optimization to reduce emissions. Empirical research employs scenario-based modeling, DID analyses, and cooperative game theory to affirm the effectiveness of eco-industrial parks in reducing CO2 and SO2 while fostering economic growth [47,104]. Studies also highlight that CO2 reduction incentives in algae-based eco-industrial parks can enhance both environmental performance and cost savings through improved cooperation and optimization [10].

- Industrial Parks

Studies in industrial parks, for instance, Refs. [105,106,107] are increasingly incorporating symbiosis-driven frameworks. Relevant case studies in industrial parks involve multi-energy system optimization [5], carbon mitigation programs, and integrated energy systems [70]. Multi-objective approaches combine renewables with energy storage to cut costs and emissions [67]. Simulation tools like HOMER or Aspen Plus, as well as MILP-based methods, help design feasible system architectures that align with regulatory and financial constraints.

- Other Industrial Sectors

Industrial symbiosis principles are adapted to other industrial areas [108,109] such as agriculture, petrochemicals, fisheries, and beyond [26]. Tools such as Catalytic methanation, for instance, utilize CO2-rich off-gases for green fuel production [42], while electrocoagulation of industrial effluents demonstrates synergy potential in fish processing [110]. Such applications confirm that industrial symbiosis can be tailored to different sectoral challenges, from specialized chemical routes to wastewater valorization.

The literature indicates that tool choice is shaped by the maturity of park infrastructure, the availability of shared utility systems, and the feasibility of data sharing across firms, which jointly influence whether advanced optimization and simulation can move beyond feasibility analysis toward deployment.

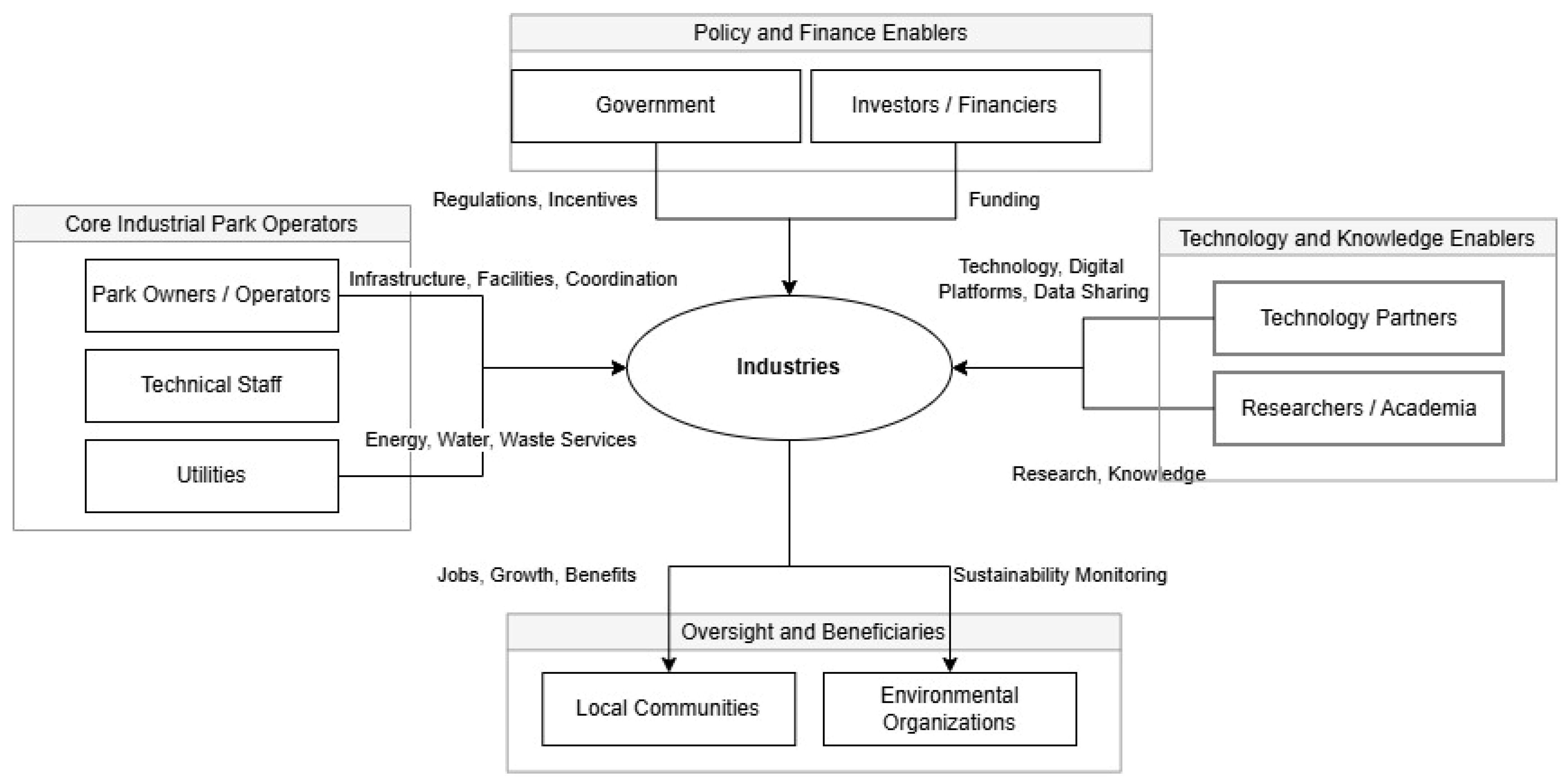

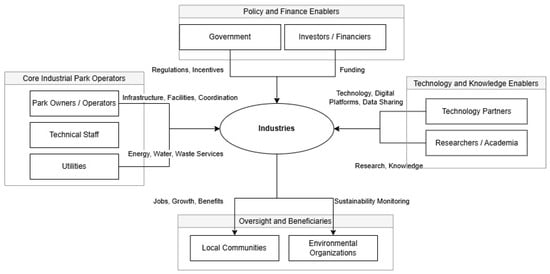

3.1.4. Key Stakeholders in Industrial and Eco-Industrial Parks

The successful deployment of industrial symbiosis relies on the involvement of numerous stakeholders. While not always explicitly stated in the literature, they are key contributors to the development and operation of sustainable, innovative industrial ecosystems. Figure 6 illustrates these stakeholder groups, clustered into Core Industrial Park Operators, Policy and Finance Enablers, Technology and Knowledge Enablers, and Oversight and Beneficiaries, with industries positioned at the center as the hub of exchanges. Each group contributes distinct resources, incentives, or oversight to collective resource management and innovation [1,15].

Figure 6.

Key relationships among stakeholders in industrial and eco-industrial parks.

Government agencies establish environmental standards and offer incentives, while utilities ensure the provision of consistent service. Industrial park owners and operators provide infrastructure, facilities, and coordination, enabling industries to function and exchange resources. Technology partners deliver digital platforms, technologies, and data-sharing solutions, supporting innovation and monitoring. Investors and financiers advance funding for park development, while researchers and academia contribute knowledge and pilot new industrial symbiosis and carbon capture technologies. Environmental groups and local communities emphasize sustainability outcomes, accountability, and shared benefits, including job creation and economic growth. Technical staff (e.g., engineers, technicians, energy managers, consultants) build and maintain systems to ensure efficient park operations.

These stakeholders operate in a highly interconnected ecosystem. For example, government bodies influence industries and park operators through environmental policies and financial incentives, while utilities and technology developers provide essential services and digital infrastructures for monitoring and coordination. Researchers often collaborate with companies and park owners to test innovative symbiosis or carbon capture solutions, while communities and environmental groups exert legitimacy and social pressure, shaping public perception and adoption. These layered and reciprocal relationships highlight that effective industrial symbiosis depends not only on individual stakeholder actions but also on structured collaboration across clusters where infrastructure, finance, technology, and societal oversight converge.

3.2. Survey Results

To complement the findings from the literature review, a survey was conducted to capture real-world experiences and practitioner insights on industrial symbiosis and carbon capture tool adoption. This section presents key results from the survey, focusing on how industry professionals perceive, use, and evaluate these tools in operational contexts.

3.2.1. Practitioner Background and Perceptions of Industrial Symbiosis and Carbon Capture

A total of eight participants with diverse professional backgrounds participated in the survey, providing both quantitative and qualitative input. Although the sample size is limited, the respondents represent highly specialized expertise directly involved in tool development, evaluation, or application, which aligns with the exploratory objective of the survey. Respondent backgrounds are summarized in Table 13.

Of the eight respondents, three are senior researchers with more than ten years of experience, two are mid-career researchers with five to ten years of experience, and three are early-career researchers with less than five years of experience. This distribution indicates that the survey captures perspectives across different career stages rather than being dominated by a single experience group.

Regarding carbon capture, six out of eight respondents identified regulatory compliance, carbon credits or carbon pricing, and market reputation as key motivations for adoption, while four respondents also referenced financial support mechanisms such as subsidies or grants. At the same time, three respondents expressed uncertainty about the relevance of carbon capture to their current organizational context. This divergence suggests that while carbon capture is recognized as strategically important, its perceived applicability remains uneven across organizations, reflecting differences in regulatory exposure, investment capacity, and technology readiness. These patterns are consistent with prior studies highlighting the role of economic and regulatory drivers in adoption [42], as well as the inhibiting effects of cost and technical uncertainty [49].

In addition to carbon capture, the survey explored each respondent’s perceptions of industrial symbiosis (as shown in Table 14). Six respondents (75 percent) identified cost savings and resource sharing as primary benefits, and four respondents (50 percent) highlighted new revenue from by-products. Several respondents referenced established cases such as Kalundborg Symbiosis, indicating that concrete examples play an important role in legitimizing industrial symbiosis practices. Conversely, five respondents (62.5 percent) identified high initial costs and limited awareness as significant barriers. This pattern reinforces the literature’s emphasis on trust-building, demonstrable benefits, and supportive policy environments as prerequisites for wider adoption [8].

These findings indicate that practitioner support for industrial symbiosis and carbon capture is strongly conditioned by tangible economic incentives and visible success cases, rather than by abstract sustainability goals alone. The coexistence of strong perceived benefits and persistent uncertainty highlights a gap between conceptual attractiveness and operational readiness, which mirrors patterns observed in the literature review.

Table 13.

Professional background, expertise, and experience of practitioner survey respondents (N = 8).

Table 13.

Professional background, expertise, and experience of practitioner survey respondents (N = 8).

| Category | Expertise Areas | Years of Experience | Involvement with Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software and Systems | Software Engineering (2 respondents) | <5 years | Main developers |

| System Innovation for Transformative Change | >10 years | Heavy user | |

| Energy and Processes | Hydrogen, CCU, Industrial Energy Transformation | 5–10 years | Some experience |

| Energy Optimization, Process Integration | >10 years | Some experience | |

| Carbon Capture and Storage | Carbon Capture and Storage, Energy Systems, Economics | <5 years | Heavy user |

| Methanation, CCU, Carbon Capture | >10 years | Main developer | |

| Sustainability and Industrial Symbiosis | Industrial Symbiosis, Renewables in Processes | <5 years | Some experience |

Table 14.

Familiarity with and perceived benefits of industrial symbiosis and carbon capture among survey respondents (N = 8).

Table 14.

Familiarity with and perceived benefits of industrial symbiosis and carbon capture among survey respondents (N = 8).

| Respondent ID | Familiarity with CC | Importance of CC | Benefits of CC | Familiarity with IS | Importance of IS | Benefits of IS | Barriers to IS | Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Somewhat familiar | Unknown | Carbon credits/pricing; Compliance | Unsure | Unknown | Cost savings; Revenue from by-products | Lack of knowledge/awareness | – |

| 2 | Somewhat familiar | Unknown | Credits/pricing; Compliance; Market reputation; Tax incentives; Subsidies | High | High | Cost savings; By-products; Shared resources; Tax incentives; Subsidies | Technological limitations | Kalundborg Symbiosis |

| 3 | Very familiar | Not relevant | Subsidies; Market reputation; Grants | Not relevant | Not relevant | Grants; Technical assistance; Shared resources; By-products | Government research institute context | – |

| 4 | Very familiar | High | Credits/pricing; Compliance; Grants; Technical assistance | High | High | Cost savings; By-products; Shared resources; Technical assistance | Technological limitations; Lack of awareness | – |

| 5 | Very familiar | High | Credits/pricing; Compliance; Market reputation; Grants | High | High | By-products; Cost savings; Shared resources; Grants | Lack of awareness; High initial costs | – |

| 6 | Somewhat familiar | Not relevant | Credits/pricing; Compliance; Tax incentives | Not relevant | Not relevant | Cost savings; Shared resources; Technical assistance | High initial costs | ICEIS project |

| 7 | Very familiar | Very high | Credits/pricing; Compliance; Operational efficiency; Reputation; Tax/Subsidies… | Unsure | Unknown | Cost savings; By-products; Shared resources; Tax, Subsidies; Grants… | Not specified | – |

| 8 | Somewhat familiar | Moderate | Credits/pricing; Compliance; Market reputation; Tax incentives; Subsidies | High | High | Cost savings; By-products; Shared resources; Tax incentives; Tech. assist. | High costs; Lack of awareness; Insufficient network | Conceptual studies only |

Note: CC: carbon capture; IS: industrial symbiosis (Source: survey data).

3.2.2. Tools and Methods Overview

Survey participants reported the functions, maturity levels (TRLs), and usage contexts of tools they develop or use for industrial symbiosis and carbon capture. Among the eight respondents, two reported using tools at TRL 9, two reported tools at TRL 6, one reported TRL 4, one reported TRL 5, and two selected “other” or were uncertain. These results indicate that practitioners engage with tools across a wide maturity spectrum rather than converging on a single readiness level.

Table 15 summarizes each tool’s purpose, strengths, limitations, TRL, and tested regions. Tools such as System Dynamics and Aspen Plus are well-established and widely cited in the literature (TRL 9), while others, such as the Symbiosis Tool and Zukunftsbild Oberösterreich, remain at pilot or demonstration stages (TRL 4–6). Only one respondent (12.5 percent) described a specific carbon capture technology (catalytic methanation), whereas the remaining respondents focused on modeling, planning, or visualization tools. This imbalance suggests that, in practice, methodological and planning tools are more commonly used than dedicated carbon capture technologies at the industrial park level, reflecting the early deployment stage of CC technologies in symbiosis contexts.

Table 15.

Functions, technology readiness levels, and reported limitations of industrial symbiosis and carbon capture tools based on practitioner input (N = 8).

The distribution of TRLs and tool types indicates a clear usability–depth trade-off. High-TRL tools such as Aspen Plus and System Dynamics offer analytical rigor but require specialized expertise and extensive data, which constrains accessibility. In contrast, lower-TRL tools such as the Symbiosis Tool and Fact Sheets lower entry barriers but provide limited analytical depth. This trade-off explains why practitioners often combine multiple tools rather than relying on a single integrated solution.

Several respondents noted plans to expand tool functionality, including extending modeled flow types, enabling automated facility comparisons, and incorporating sustainability metrics beyond energy balances [63]. This forward-looking orientation suggests that practitioners recognize current tool limitations and actively seek hybrid solutions that balance usability and analytical capability, consistent with prior findings that industrial symbiosis tools must remain adaptable to heterogeneous sectoral and organizational contexts [46]. The diversity of tools corroborates literature findings that industrial symbiosis implementation typically relies on a combination of detailed simulation and simpler, entry-level instruments for early-stage data collection and matchmaking [36,90].

3.3. Application and Implementation Contexts

Most surveyed tools address multiple scales in industrial parks, from individual processes to entire facilities, integrating external networks. Table 16 also describes the entities that developed each tool and the typical user profiles. Many participants stated that universities or research institutions initiate the tools’ development, reflecting a strong research-driven impetus behind these solutions [53]. However, successful adoption often depends on collaboration between diverse stakeholders (industrial park operators, technology providers, and local authorities) who must collectively resolve technical, social, and economic constraints, consistent with prior findings on stakeholder coordination and governance in industrial symbiosis systems [9].

Table 16.

Overview of industrial symbiosis and carbon capture tools reported in the practitioner survey, including developers, users, and application contexts (N = 8).

Table 17 below details the specific barriers that survey respondents face when using or implementing the tools. Data confidentiality, limited standardization, and user acceptance were identified as the most frequently cited constraints, reported by at least five respondents. In contrast, purely technical limitations were mentioned less consistently. In some cases, tool outputs may require significant operational changes (e.g., rescheduling machine operations), prompting reluctance or skepticism among facility owners [56]. Participants also noted that certain tools remain largely illustrative, lacking in actionable detail if sufficient or reliable data are unavailable. These survey-based observations align with earlier studies emphasizing that data-sharing frameworks, trust among stakeholders, and practical feasibility are decisive factors in scaling industrial symbiosis beyond pilot or demonstration stages [54].

Table 17.

Reported utilization and implementation challenges of industrial symbiosis and carbon capture tools from the practitioner survey (N = 8).

The predominance of organizational and data-related barriers over purely technical ones reinforces the conclusion that tool maturity alone is insufficient for successful deployment. Even high-TRL tools may remain underutilized when governance arrangements, data-sharing agreements, and incentive structures are weak, a pattern consistently reported in the industrial symbiosis literature. This finding underscores that industrial symbiosis tools operate at the intersection of technical optimization and organizational change, and their effectiveness depends on both dimensions.

The mixed-methods survey reveals that industrial symbiosis and carbon capture tools vary in maturity, ranging from early-stage (TRL 4–6) platforms focused on visualization or data gathering, to advanced simulators (TRL 9) capable of rigorous process optimization. Despite strong practitioner interest in decarbonization and resource efficiency, adoption remains uneven due to cost constraints, data confidentiality, and the need for cross-organizational coordination, echoing patterns identified in earlier empirical and review-based studies. These insights reflect a tension between the promise of industrial symbiosis, highlighted by established examples like Kalundborg, and the real-world complexities of adopting tools that require extensive data inputs and cross-functional collaboration.

4. Discussion

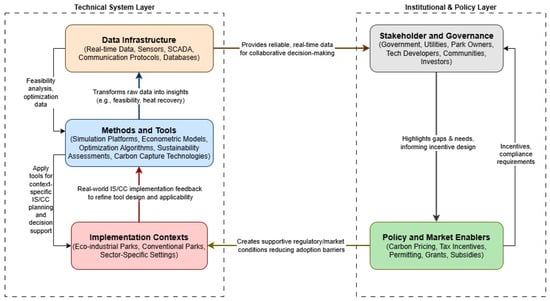

This section interprets and synthesizes the findings presented in Section 3, moving beyond descriptive results to examine their implications for tool adoption, integration, and governance in industrial symbiosis and carbon capture. Section 4.1 compares practitioner survey evidence with literature-based findings, highlighting convergences, divergences, and adoption gaps across tools and methods. Section 4.2 develops an integrated conceptual framework that explains how tools, data infrastructure, stakeholder governance, policy and market enablers, as well as implementation contexts interact as a socio-technical system. Section 4.3 translates these insights into future research directions and actionable recommendations, focusing on data governance, policy support, technological integration, and long-term system evolution.

4.1. Comparison Between Surveyed Tools and Literature

The literature review highlights a wide spectrum of tools and methods used to advance industrial symbiosis and carbon capture initiatives—ranging from visualization platforms (e.g., Symbiosis Tool, Zukunftsbild Oberösterreich) to process-level simulations (e.g., Aspen Plus) and systemic modeling approaches (e.g., System Dynamics, Total Site Heat Integration). Survey insights, though derived from a small sample, illuminate adoption-related and organizational challenges that are only weakly reflected in the predominantly technology-oriented academic literature.

4.1.1. Tool Maturity Versus Adoption Feasibility

As shown in Table 18, tools like Aspen Plus and System Dynamics are consistently rated at TRL 9 in both literature and practice. However, survey respondents flagged challenges related to complexity and usability. Aspen Plus, while widely used for modeling CO2 absorption and process-level emissions, remains only weakly integrated with broader industrial symbiosis networks, largely due to its specialization and high data requirements. This suggests that high TRL alone is not a sufficient indicator of deployment readiness in multi-actor industrial symbiosis contexts. Similarly, System Dynamics offers strong capabilities for simulating long-term feedback and stakeholder behaviors but requires conceptual expertise and user engagement, which can hinder practical uptake.

Table 18.

Overview of the tools/methods.