Abstract

The workplace, as a promising location for Electric Vehicle Supply Equipment (EVSE), presents a particular challenge, as different user requirements (e.g., parking and charging durations) meet a spatially and quantitatively limited offer of EVSE. However, integrating electric vehicles synergistically into the energy system of the employer can increase the profitability of the system and, correspondingly, increase the number of EVSE. For this, a deep understanding of employees’ charging behavior is key. For providing some evidence of empirical charging patterns at the workplace, this work examined a dataset of 23.9 million observations on empirical charging processes at workplaces in 2023. To identify user groups, a probabilistic model (Gaussian Mixture Model) and a K-Means clustering approach were applied and the results compared. Eight groups were identified, including full-time and part-time employees, pool vehicle users, and opportunists. The group-specific probability distributions are used to publish a synthetic dataset of parking and charging patterns at workplaces. The openly provided dataset helps to identify the right composition of EVSE in the employee context and to optimize potential fields of action.

1. Introduction

The latest update of the Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Regulation by the European Commission (2023/1804) mandates the deployment of a sufficient network of charging and refueling stations across the trans-European transport (TEN-T) network to cut carbon emissions by 2030. Besides the requirement of installing fast-charging stations every 60 km along the TEN-T, the provision of decentral Electric Vehicle Supply Equipment (EVSE) is also addressed and its smartness (and even vehicle to grid) claimed.

Germany has transferred these European targets to national regulation by introducing the Climate Action Law and further measures. One national core target is to achieve 1 million publicly accessible charging points and 15 million registered Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs) by 2030 [1]. However, significant efforts seem to be required for achieving these goals as current numbers fall behind schedules [2]. Reasons for the delayed ramp-up include the current poor economic profitability of most EVSE [3] as well as high purchase prices for BEVs, a limited model range, and long delivery times for BEVs [4,5]. Market-related barriers are complemented by subjective, psychological obstacles [6]. The EVSE must be optimally aligned with the behavior and preferences of customers, focusing on range anxiety [6,7], and provide users the opportunity to charge at their immediate location [8]. Suitable locations include employers, shopping centers, supermarkets, leisure centers, sidewalks/curbsides, or homes [3].

Establishing a demand-driven charging infrastructure critically depends on acquiring a deep understanding of daily mobility habits, including the frequent locations of BEV users. Various studies provide clues for gathering this information, such as those based on national travel surveys. In Germany, e.g., the “Mobility in Germany 2023” (MiD), the “German Mobility Panel 2021/2022” (MOP), the “Survey on Mobility in Urban Areas–SrV 2018,” and the mobility survey by the Federal Environment Agency, which focuses particularly on the commuting paths of employees, provide an empirical basis for current mobility patterns of cars. These studies emphasize the central role of private cars as the predominant mode of transport in individual motorized traffic and highlight the relevance of location choice for charging infrastructure, noting that cars are parked on average for 23 h a day [9]. At the same time, the stationary time of cars is mainly concentrated at home or at the workplace. While charging at home is mainly characterized by a one-to-one relation of EVSE and BEV as well as very regular (overnight) patterns and long plug-in times, charging at the workplace is more heterogeneous, and the EVSE per BEV ratio is much lower.

From an employer’s perspective, the provision of EVSE is, on the one hand, an attractive asset for attracting diligent employees but, on the other hand, also costly. Consequently, a profound knowledge of concrete charging needs by employees is key for a cost-efficient provision of EVSE. In the literature, this data for charging demand by employers at workplaces is hardly available, and most studies lack sound empirical data on concrete charging processes (cf. Appendix A). Within this research challenge, the following two research questions arise:

- Which charging pattern clusters can be identified form empirical workplace charging patterns for providing a solid basis for providing optimal EVSE portfolios at workplaces?

- Do these empirically derived charging clusters support the predictability of load forecasting and identifying flexibility options for electricity markets?

For answering these research questions, the structure of the paper is as follows. Section 2 provides a literature overview and highlights the research gap. Afterwards, the collected and openly published data on charging at the workplace is explained in Section 3.1 before the clustering methods for identifying suitable charging patterns are introduced. The Section 4 highlights the identified eight charging clusters. Section 5 and Section 6 discuss the results and conclude the paper.

2. Literature Review

A thorough analysis of usage behavior of BEV charging is crucial to identify characteristic patterns and develop a deeper understanding of charging processes. These insights are fundamental for enhancing the accuracy of predictions regarding the cost-efficient provision of EVSE, as well as for identifying potential optimization opportunities for grid services. Several clustering studies are already available for identifying different BEV usage groups in terms of charging patterns.

Schäuble et al. [10] have been one of the first focusing on charging processes from empirical data at workspaces. However, they did not cluster their data and focused on early-stage BEV charging processes, which are not representative. Similarly, Schücking et al. [11] based their analysis on a specific environment and focused on the optimization of BEV mileage. Specifically, Märtz et al. [12] clustered user groups based on 2.6 million charging events by a broad BEV fleet, incorporating information such as location, plug-in and plug-out times, energy demand, as well as charging duration. The eight user groups identified in this study did not cover the specific context of employees and focused exclusively on one vehicle type, the BMW i3. Similarly, Friese et al. [13] explored usage patterns using clustering methods at 2409 charging points in and around Munich, without addressing the specific behavior of employees. Hecht et al. [14] expanded this research perspective by identifying different charging patterns through the analysis of data from 26,951 charging stations in Germany, thereby depicting a broader spectrum of usage behavior and charging events.

On the international level, the behaviors of BEV users have been investigated as well. Helmus et al. [15] and Straka & Buzna [16] focused on the clustering of user behaviors in the four largest cities and metropolitan areas of The Netherlands. Helmus et al. [15] used a dataset of more than 5.82 million charging transactions from January 2017 until March 2019 on public charging infrastructure from the Dutch metropolitan areas whereas Straka & Buzna [16] accesses the data from the Dutch company ElaadNL.

Crozier et al. [17] based their study on data from the National Travel Survey in the United Kingdom and identified the charging processes hypothetically based on specific assumptions. Although the studies occasionally recognized clusters indicative of employee behavior (charging throughout the day), no specific differentiation was made. Flammini et al. [18] modeled usage behaviors using multimodal probability distributions based on 400,000 charging transactions, and Wolbertus et al. [19] identified different charging patterns through a benchmark study. The detailed consideration of employee behaviors remained unaddressed as well. Currently, the trend of simulated charging profiles has become popular (e.g., Usmani & Morales-España [20]; Gaete-Morales et al. [21]).

In addition to direct analysis of charging processes, alternative approaches enable the simulation of load profiles for further investigation of mobility behavior. Pagani et al. [22] introduced an innovative agent-based simulation framework that takes into account the charging behavior of BEV users as well as the spatial distribution of vehicles, thereby presenting a stochastic approach to profiles and behaviors. Seddig et al. [23] based their analysis on empirical charging data from a parking lot, applied a clustering for separating three main user groups (including commuters), and implemented these findings in an optimization tool for electricity usage from photovoltaics.

In contrast to earlier clustering studies (e.g., Märtz et al., 2022 [12], Friese et al., 2021 [13]), which include heterogeneous public or mixed-use charging environments, our analysis focuses exclusively on workplace charging with more than 37,000 events. This results in employee-specific clusters that are not observable in public datasets. The openly provided synthetic data further enables reproducibility for workplace-specific modeling. To our knowledge, this is the largest empirically based dataset focused exclusively on workplace charging and the first to publish cluster-based synthetic profiles for this context. These research efforts make a significant contribution to expanding the understanding of usage and charging behavior, yet they omit a detailed analysis of charging behavior in the context of workplace charging.

3. Data and Methods

This section provides a rough overview of the methodological approach of this study and the derivation of the openly available dataset (synthetic profiles based on empirical data) and gives an introduction to the applied clustering methods (Section 3.2).

3.1. Empirical Data and Case Study

3.1.1. Data Records

This study is based on a comprehensive empirical dataset of workplace charging provided by the charging infrastructure manufacturer and operator ChargeHere (https://chargehere.de/) for three facilities of the company EnBW (www.enbw.com) located in southwestern state Baden-Württemberg, Germany. The dataset comprehends 23.9 million empirical charging data from the year 2023 including the time of plugging in and unplugging, the parking and charging duration, as well as the amount of energy charged. For identifying user groups characterized by specific parking and charging behavior, the data are processed, and a probabilistic model (Gaussian Mixture Model) and a K-Means clustering approach are applied. By providing the mean values and standard deviations, as well as a cluster-specific synthetic dataset of parking and charging patterns, the reproducibility of the different cluster groups for future research is ensured. It can be used for optimizing the portfolio of EVSE at workplaces and other research fields.

Based on the empirical data, synthetic profiles have been generated and stored. They are available for download on Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11506701.

The dataset can be downloaded as an Excel file (.xlsx) and contains eight individual files, one for each identified cluster. Each file includes 1000 synthetic observations generated using a Monte Carlo sampling procedure. For every cluster, synthetic parking start times and parking durations were drawn from the cluster-specific multivariate normal distribution, parameterized by the empirical mean vectors and covariance matrices reported in Appendix D. This procedure preserves the correlation structure between both variables. The synthetic datasets reproduce the main statistical properties of the empirical clusters, including means and variances, while serving as a reproducible representation of workplace-specific charging patterns. Additionally, cluster-level descriptive metrics such as mean, median, and standard deviation of parking start, parking duration, charged energy, and charging duration are provided.

To verify the adequacy of the synthetic profiles, we conducted a statistical validation comparing each synthetic cluster with its corresponding empirical GMM parameters. For every cluster, we examined the reproduction of (i) means, (ii) variances, and (iii) the empirical correlation between parking start time and parking duration. In addition, univariate Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests were performed for both variables. The synthetic datasets accurately reproduced the key statistical properties of the empirical clusters. Detailed results of the validation are provided in Appendix G.

3.1.2. Data Characteristics

The analyzed dataset includes empirical parking and charging data of electric vehicles (EV), i.e., BEV and plug-in hybrid vehicles (PHEV), during the whole year of 2023. The data were provided by ChargeHere, a charging infrastructure manufacturer and operator, which is a subsidiary of the EnBW Group. This data collection took place at three different facilities of EnBW, namely Stuttgart (STU), Karlsruhe (KAR), and the Neckarwestheim Power Plant (NWH). Access to the charging infrastructure is exclusively guaranteed for employees of EnBW.

At the STU and KAR locations, there were 100 EVSE available each, while at the NWH location, there were 20 EVSE available. While STU and KAR are dominated by office employers, shift workers dominated the parking at the NWH location. The dataset comprises the respective EVSE ID, the date and time of each charging process, the energy meter, the activity state of the EVSE (connected, not connected, charging, not charging, error), and the current per conductor in a 5 min interval. The original raw data were documented according to IEC 61851-1 [24], where states A (“No vehicle connected”), B (“Vehicle connected not charging”), and C (“Vehicle connected and charging”), which define the status of a connection between an EV and an EVSE, are given. Table 1 illustrates the format of the transmitted data. Each charging point had a maximum charging capacity of 11 kW. The arrival time is equated with the moment the charging cable is connected, while the departure time corresponds to the moment the charging cable is removed from the vehicle. The duration of the connection is determined by the difference between the arrival and departure time; thus, it can be equated to the parking duration. Consequently, the parking duration is divided into a charging and connection duration.

Table 1.

Overview of provided data structure.

The present charging data are anonymized and cannot be assigned to any specific user or vehicle. This dataset represents a significant contribution to the scientific literature, as it is the largest known dataset on charging behavior at the workplace.

3.1.3. Data Processing

The datasets from the STU, KAR, and NWH locations were time zone-adjusted, consolidated, and subjected to extensive data cleaning. The original dataset comprised 23,990,400 records, from which 41,700 parking and charging events were identified. Some of these events were erroneous and thus required systematic cleaning.

The cleaning was conducted based on specific criteria to ensure data quality. Only parking and charging events that started and ended within a 24 h period were considered. It was also ensured that charging demonstrably occurred during these events (charged energy > 0). Furthermore, only charging processes with a maximum charging time of no more than 18 h (charging duration ≤ 18) and at least 30 min (charging duration ≥ 0.5) were included.

Applying these criteria resulted in the exclusion of 3375 events with parking durations above 24 h, 384 events with zero charged energy, 47 events with charging durations above 18 h, and 656 events with charging durations below 30 min. In total, the filtering process reduced the dataset from 41,700 to 37,238 usable events. Of these 37,238 events, 625 occurred on a Saturday and 439 on a Sunday. Thus, 36,174 events (97%) took place on a weekday. In total, 141 charging events were initiated on a public holiday, with a significant portion at the NWH location. Table 2 and Table 3 display the charging events from Monday to Sunday and on holidays for the year 2023 at the various locations. Hence, the dataset highlights the conventional pattern of workplace charging from Monday to Friday.

Table 2.

Numbers and shares of charging events per week.

Table 3.

Charging events on public holidays.

Prior to cleaning, candidate events were identified from the EVSE state stream using the state-grouping procedure in Algorithm 1: contiguous segments of states bounded by the “A” state (“no vehicle connected”) are grouped to delineate individual parking and charging episodes; from these segments we derived start/end times, parking/charging durations, and charged energy, which are then fed into the filters above.

| Algorithm 1: State Grouping Algorithm |

| Require: DataFrame with column EVSE_State function IDENTIFY_GROUPS(df) 1. states ← df[‘EVSE_State’] 2. grouped_states ← [ ] 3. current_group ← [ ] 4. for each state in states do 1. if state == ‘A’ then 1. if current_group is not empty then 1. grouped_states.append(current_group) 2. current_group ← [ ] end if else 2. current_group.append(state) end if end for 5. if current_group is not empty then 1. grouped_states.append(current_group) end if 6. return grouped_states end function |

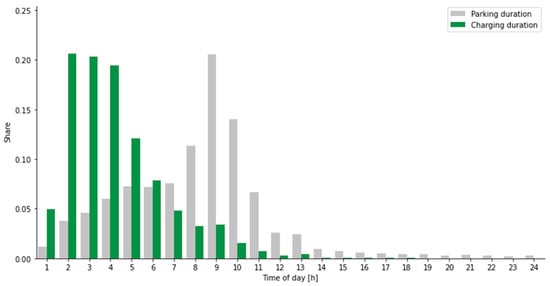

3.1.4. Charging Behavior

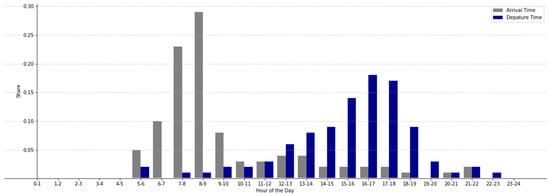

In the following subsection, the evaluation of the 37,238 parking and charging events for the STU, KAR, and NWH locations are presented and discussed. Figure 1 shows the percentage distribution of arrival and departure times within a day over the year 2023. The percentage values are depicted for each hour between 0 and 24 on the horizontal axis. Each hour starts on the hour and ends 59 min after the start of the hour. For example, the first hour begins at 0:00 and ends at 0:59.

Figure 1.

Distribution of arrival and departure time over the day.

The majority of employees, namely 62%, arrive at their workplace between 6:00 and 9:00 a.m. A subsequent increase is observed between 12:00 and 2:00 p.m. and between 9:00 and 10:00 p.m., accounting for 8% and 2% of the total volume, respectively. Similar patterns are evident in the departure of employees: 49% conclude their parking event between 3:00 and 6:00 p.m., while 2% leave the parking facility between 9:00 and 10:00 p.m. and between 5:00 and 6:00 a.m., respectively. Overall, the sequence of events reflects a typical pattern of employee behavior.

Appendix B illustrates the temporal distribution of charging and parking duration throughout a day over the year 2023. The charging duration runs counter to the parking duration. In the first four hours of the day, 64% of charging sessions are completed, while 85% of electric vehicles remain connected to the charging point for longer than four hours.

On average, an EVSE was used by 1.16 EVs per day, referring to the number of plug-in events per charging point rather than its temporal utilization. The value is obtained by dividing the total number of plug-in events by the length of the observation period (in days). For illustration, 29 sessions over 25 days yields 29 ÷ 25 = 1.16. The average amount of energy charged per workday was 25.03 kWh and was calculated as follows:

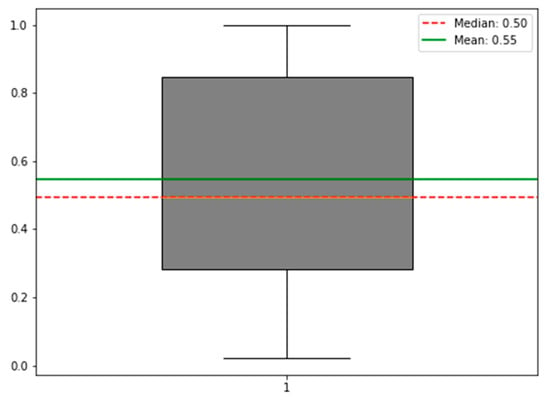

Overall, an energy demand of 932.25 MWh was identified for EV charging in 2023. On average, a charging process constituted 55% of the parking duration (cf. Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Charging to parking time ratio.

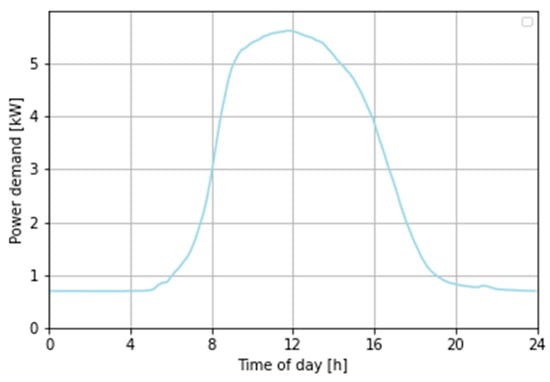

Appendix C illustrates the average power over an average day per EVSE throughout the year 2023 across all locations, presented in hourly resolution. The peak charging power is reached at 11:45 a.m., with an average power of 5.62 kW per EVSE.

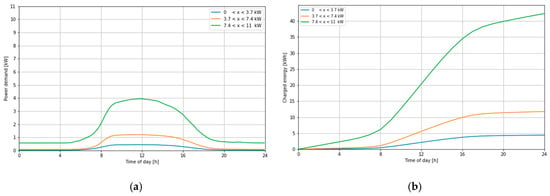

The proportional distribution of charging power per EVSE over all events and power class is graphically represented in Figure 3a. To identify the utilized charging power, the average charging power for each individual charging event was determined based on the information about the charged energy amount and charging duration. The proportionate average charging power across all charging events is listed in Table 4.

Figure 3.

(a) Distribution of average energy charged in each power class per EVSE over all charging events and days; (b) distribution of cumulated charged energy in each power class per EVSE over all charging events and days.

Table 4.

Distribution and average charging power of all charging events.

Throughout a day, single-phase charging (i.e., up to 3.7 kW) accounted for 4.4 kWh, two-phase charging (between 3.7 and 7.4 kW) for 11.8 kWh, and three-phase charging for 42.3 kWh (cf. Figure 3b) respectively.

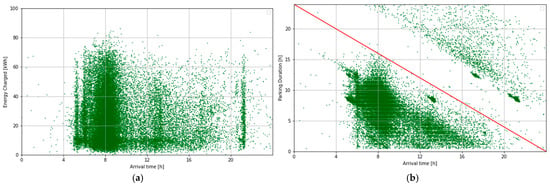

In Figure 4a, a scatter plot of the plug-in time (x-axis) and the charged amount of energy (y-axis) is given. It illustrates the respective peak arrival times and the corresponding recharged energy values of, on average, 29.2 kWh.

Figure 4.

Energy demand over arrival time (a) and parking duration over arrival time over the day (b).

Figure 4b visually relates the arrival time (x-axis) to the parking duration (y-axis). A dividing line identifies two clusters. All data points above the dividing line represent charging processes that ended on a different day. All points below represent charging processes that occurred on the same day.

3.2. Methods

In the following, distinct user groups are identified which differentiate according to arrival time and parking duration. For the segmentation and analysis of the user groups, two different approaches were used: the Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) and the K-Means clustering algorithm. The GMM and K-Means are established and proven clustering techniques widely used in scientific research (e.g., Ref. [12]). Both methods, part of the unsupervised learning domain, are adept at identifying patterns or structures within datasets. GMM, known as a soft-clustering method, assigns data points to clusters based on probabilities, taking into account the data’s density distribution for a probabilistic cluster assignment [25]. Conversely, K-Means, a hard-clustering approach, uses Euclidean distance to assign each data point to the cluster center it is closest to, without considering the density distribution or other geometric features within the dataset [26]. By integrating both methods, cluster formation can be validated, thereby enhancing the understanding of data structures. This combination leverages the strengths of both techniques to achieve meaningful and robust results.

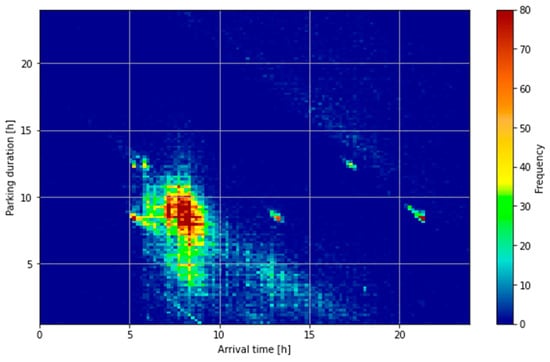

In the initial step of the analysis, the distribution and density of the data points were examined using a heatmap. This method allows for a visual representation of the frequency or intensity of the data within a given spatial context. By applying this technique, five central clusters within the data cloud could be identified, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Heat map of parking duration over arrival time.

3.2.1. Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM)

GMM is a significant method in the field of unsupervised learning in data science. Unsupervised learning focuses on discovering patterns or structures in datasets without requiring prior labeling or classification [25]. The method postulates that data in a dataset represent a mixture of several normal distributions. Unlike the K-Means algorithm, where clusters are represented by centroids, GMM uses normal distributions to characterize clusters. The main goals of GMM are to accurately model the data distribution, probabilistically assign data points to clusters (as opposed to hard assignment), and estimate model parameters such as means, variances, and mixture coefficients.

Formally expressed, the GMM can be described by the following probability density function:

Here, K represents the number of components (clusters), represents the mixture coefficients, represents the means, and represents the covariance matrices of the normal distributions. Overall, the Gaussian Mixture Model provides a powerful way to model complex data structures and tackle clustering tasks in a more flexible manner [26].

The number of components was determined by evaluating Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) [27] and Aikaki Information Criterion (AIC) [28] values for GMMs with up to fourteen components. Both criteria exhibited their lowest values around eight components, indicating that this specification provides the most appropriate balance between model fit and complexity. This result was stable across repeated model runs and consistent with the visually observable separation of temporal usage patterns.

In the empirical implementation, the GMM was applied to two continuous variables describing the temporal characteristics of each charging event: the parking start time (in hours) and the total parking duration (in hours). Both variables were converted to a consistent hour-based scale, ensuring smooth density estimation within the model. This two-dimensional representation captures the structure of arrival and stay behavior and allows the GMM to utilize its full covariance specification to identify potential correlations between these variables. Parameter estimation was performed via maximum-likelihood using the expectation–maximization algorithm. The resulting component means, covariance matrices, and mixture weights form the basis for characterizing the temporal patterns in the identified user groups. A detailed explanation of all symbols and units used in the GMM formulation is provided in Appendix F. The clustering was intentionally based solely on arrival time and parking duration, as these temporal variables directly capture user presence behavior and align with the study’s focus on temporal flexibility. Energy- and power-related variables were not included, as they partly reflect outcomes of vehicle- and infrastructure-specific constraints rather than underlying temporal patterns.

3.2.2. K-Means Clustering

The K-Means algorithm is another method of unsupervised learning in data science, characterized by its analysis of unlabeled data. At the core of the K-Means algorithm is the grouping of data into a predefined number of clusters, where “K” represents the number of these clusters. A cluster is a collection of data points that are grouped together based on specific similarity criteria, such as spatial proximity. The function of the K-Means algorithm is to group a set of data points {} into K clusters, minimizing the sum of squared distances between the data points and their assigned centroids. Formally, the algorithm aims to minimize the following cost function J:

Here, J represents the total variance within the clusters that is to be minimized. The variable represents an individual data point, represents the centroid (center) of cluster j, and represents the set of data points assigned to cluster j. The number of clusters is denoted by K [29].

For the empirical application of the K-Means algorithm, the parking start time and the total parking duration, both expressed in hours, were used as input variables. These two temporal characteristics capture the arrival structure and length of stay of each charging event and therefore reflect the behavioral patterns that are central to the research objective. The model was run with eight clusters, and the centroids were iteratively updated until convergence. Each data point was then assigned to the nearest centroid, and the resulting cluster centers and cluster sizes were used to describe the dominant temporal usage patterns in the dataset. A comprehensive description of all variables and units appearing in the K-Means objective function can be found in Appendix F.

4. Results

In the following, the identified eight clusters are presented (cf. Section 4.1) before the Charging-to-Parking Ratios Across Clusters (cf. Section 4.2) and a first concept of how to use this flexibility for arbitrage on electricity markets (cf. Section 4.3) are illustrated.

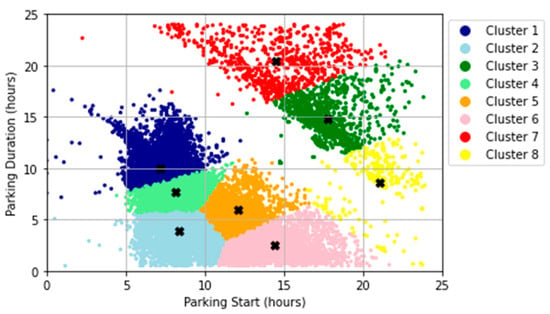

4.1. Identified Clusters

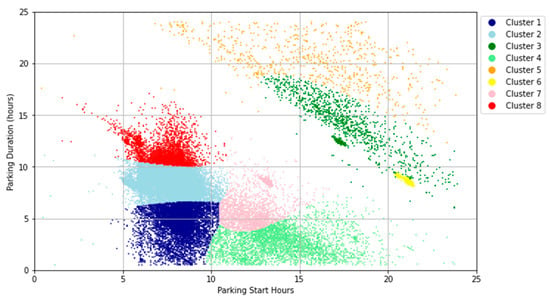

In the following section, the examination and categorization of the eight identified clusters are presented, as illustrated in Figure 6. The number of clusters confirms the diverse utilization of the charging infrastructure in the context of the employers. The detailed data for each cluster can be found in Appendix D.

Figure 6.

Results of the GMM clustering.

Table 5 shows that Cluster 2 accounts for the highest percentage of all clusters at 38%, followed by Clusters 1, 4, 8, 7, 3, 5, and 6 in descending order. With a combined share of 76%, Clusters 2, 1, and 4 represent a significant portion of the employees, highlighting their arrival time in the early morning. For 5% of the employees (Cluster groups 3 and 6), the parking and charging process begins in the (early) evening, while 19% of the employees arrive between 12:20 p.m. and 3:43 p.m.

Table 5.

Cluster overview.

The clusters can be divided into three groups based on the parking duration: short-term, medium-term, and long-term parkers. Long-term parkers are characterized by Clusters 3 and 5 but represent only a small percentage of the total at 5%. Medium-term parkers, representing 58% of the total, are connected to the charging point for an average of 9 h and 1 min. Clusters 7, 1, and 4, representing 37% of the employees, are connected for an average of 4 h and 23 min.

The longest charging durations are dominated by the relatively smallest Cluster groups 6 and 3 (on average 05:15 and 04:48 h, respectively). On average, 65% of charging operations (charging duration) are completed in 3 h and 57 min for Cluster groups 8, 5, 2, and 7. Cluster groups 1 and 4 represent the group with the shortest average charging duration, which is 2 h and 31 min. Table 5 illustrates the average charging time () alongside the standard deviations () and medians ().

A similar distribution arises in terms of the recharged energy quantity. In Cluster groups 5 and 3, the most energy is recharged, with 28.85 kWh and 28.10 kWh, respectively. Cluster groups 2, 7, and 6 constitute the middle group, representing 47% and recharging an average energy quantity of 27.15 kWh. Cluster group 1 (10%) recharges the least energy, with 17.42 kWh, followed by Cluster 1 with 22.44 kWh and Cluster 8 with 24.76 kWh.

Based on the arrival time and the duration of parking and charging, Cluster 1 and Cluster 4 were assigned to part-time employees who visit the workplace in the morning or afternoon. Both cluster groups account for 30% of the charging processes (Cluster 1: 20%, Cluster 4: 10%), thus representing an important group of employees.

Clusters 2, 7, and 6 represent both employees working in an eight-hour 3-shift system, arriving at the workplace in the morning, noon, and evening, and those following a 40 h workweek. Together, these clusters account for 47% of the total (Cluster 2: 38%, Cluster 7: 7%, Cluster 6: 2%), thus representing another important group of employees.

Clusters 7 and 4 also include users of pool vehicles who visit the site around noon and depart in the afternoon (e.g., STU ⇔ KAR, i.e. about 75 km). Their return to the original location, supplemented by pool vehicle users who were away on business during the day, is reflected in Cluster 5 (2%). Cluster 5 is further supplemented by employees who take advantage of an available charging point to charge their vehicle overnight and unplug it the following day (before the start of work).

Clusters 3 and 8 are characterized by longer dwell times compared to the other clusters and represent the group of 12 h shift workers. Cluster 3 is supplemented by pool vehicles that are plugged to EVSE upon returning from a business trip. On the other hand, Cluster 8 is supplemented by full-time employees who, like those in a 12 h system, leave the workplace after 10 h. These two clusters, 3 and 8, contain 3% and 18% of the employees, respectively. The cluster groups were validated using the K-Means clustering method (see Appendix E).

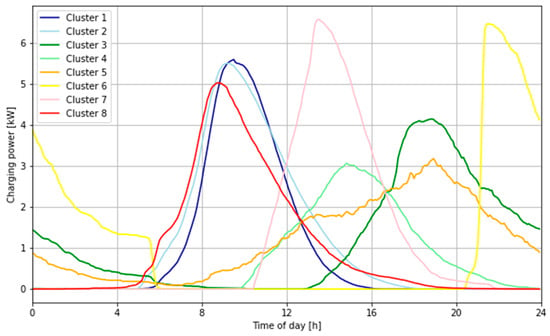

Figure 7 illustrates the charging power per cluster per charging session. The respective maximum values can be found in Table 6. The peak power per cluster follows the average arrival time. The peak power time for Clusters 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, and 8 is, on average, 1:34 h after the average connection time. Clusters 3 and 6, however, represent exceptions, with 0:39 h and 0:22 h, respectively.

Figure 7.

Average charging power per EVSE and cluster over a day.

Table 6.

Maximum average charging power per charging event per cluster and corresponding time.

The temporal distribution of the average charging power differs notably across the eight clusters. Figure 7 shows that the time at which the maximum power is reached is closely linked to the characteristic arrival times of each group. Clusters with morning arrivals (Clusters 1, 2, and 8) exhibit their peak charging power in the first hours after plug-in, which contributes to the typical morning load increase observed in workplace charging. In contrast, clusters with midday or afternoon arrivals (Clusters 4, 5, and 7) shift their power peaks accordingly, resulting in a broader distribution of charging activity over the day.

Clusters 3 and 6 represent a distinct pattern. Both groups reach their maximum average charging power shortly after arrival, within less than one hour. These clusters are associated with evening or late evening arrivals and are likely characterized by lower state-of-charge levels at plug-in, which leads to an immediate increase in charging power. The early peak in these groups contrasts with the more gradual increase observed in clusters with morning arrivals, where differences in arrival times and battery states spread the charging power over a longer period.

Taken together, these temporal variations moderate the overall aggregated load profile across all users, as the distribution of arrival times prevents a single, sharply defined power peak. The differences across clusters also indicate that load shifting strategies may benefit from the natural temporal dispersion of charging activity. This provides a link to Section 4.3, where the potential use of these temporal patterns for flexibility provision in electricity markets is examined.

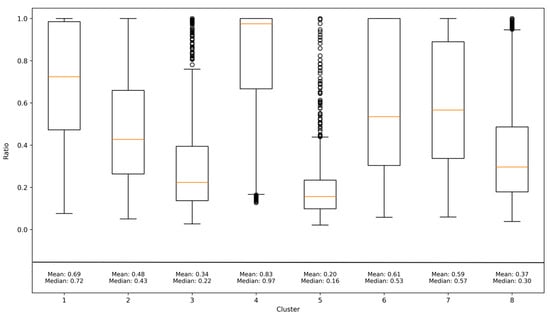

4.2. Charging-to-Parking Ratios Across Clusters

In addition to the arrival times, parking durations, and charged energy, the ratio between charging duration and parking duration provides further insight into the use of the charging infrastructure. Figure 8 shows the distribution of this ratio for all eight clusters.

Figure 8.

Box plots of all charging–parking ratios for all clusters.

The results indicate clear differences between the user groups. Clusters 1 and 4, which represent part-time employees with comparatively short parking durations, show the highest ratios. In these clusters, a large share of the connection time is actively used for charging. By contrast, clusters with long dwell times, such as Cluster 3 and Cluster 5, exhibit substantially lower ratios. Vehicles in these groups remain connected to the charging point for extended periods after charging has finished.

Clusters 2, 6, 7, and 8, associated with full-time employees and shift systems, occupy an intermediate position. Here, the charging phase typically represents between one-third and one half of the total parking duration. This reflects the common pattern that charging is completed well before the end of the stay.

Overall, the ratio highlights the heterogeneity in charging behavior across the eight identified clusters. It supports the interpretation of the user groups by illustrating how actively the installed charging infrastructure is used during the connection period. In particular, low ratios in several clusters show that a considerable share of the connection time is not associated with active charging, which is relevant when assessing the utilization of the charging system and interpreting cluster-specific charging characteristics. The ratio shows that a substantial part of the connection time is not used for charging, especially in clusters with long parking durations. As the total parking duration largely determines availability, the observed differences across clusters illustrate inherent limitations of a first-come-first-serve allocation, as prolonged non-charging periods occur even though the charging process has already been completed. At the same time, these extended dwell times expand the temporal window during which a vehicle remains technically accessible for automatically controlled charging actions. This aspect connects to the subsequent analysis in Section 4.3, where the potential use of these longer connection periods for load shifting and the provision of flexibility to electricity markets is examined.

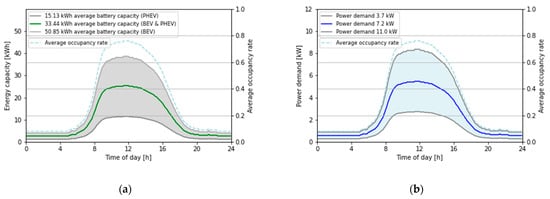

4.3. Potential Usage of Charging Flexibility: Arbitrage in the Wholesale Electricity Market

For providing a first concept about the profitability of the available load flexibility for electricity market integration, the charging data by BEV and PHEV are analyzed in terms of the overall available battery capacity and maximum charging power. Figure 9a illustrates the average available energy capacity per plugged-in BEV and PHEV during an average working day. The volume is mainly dependent on the assumed battery capacity, which in our case is set to the average capacity of registered vehicles in Germany, i.e., 50.85 kWh for BEV and 15.13 kWh for PHEV, respectively [30]. Comparing the BEV-only battery capacity, it is obvious that the flexibility is rather constant during the night at around 4 kWh per vehicle, while between 9 a.m. and about 4 p.m. the connected battery capacity is significantly higher by about 38.6 kWh.

Figure 9.

(a) Average connected battery capacity per vehicle during a working day; (b) average connected power per vehicle during a working day.

With regard to connected power, Figure 9b shows a similar pattern. Here, we differentiate by charging infrastructure and provide, correspondingly, one curve for one-phase charging (i.e., <3.7 kW), for two-phase (<7.2 kW), and three-phase charging (<11 kW). These curves represent upper bounds as most vehicles may charge individually at lower charging rates. Again, the provided flexibility in load changes is identified between the main parking times, i.e., 9 a.m. until 4 p.m., ranging from 0.6 kW to 5.5 kW. This flexibility is rather negligible during the night.

While the identified load flexibilities per vehicle in a vehicle-to-grid (V2G) scenario (i.e. we assume that electricity can be charged to and discharged from the vehicle) seem low, it sums up to about 6.8 MWh and 1.84 MW in our BEV-only case study with 220 EVSE, which is quite suitable energy storage. If it is, e.g., applied in the German day-ahead electricity market by providing arbitrage services, the resulting revenues between 9 a.m. and 4 p.m. might sum up to 1.22 EUR on average per car and day by assuming significantly simplified estimations: The average spread (i.e., difference between minimal and maximum price) on working days between 9 a.m. and 4 p.m. in 2023 has been 111.2 EUR/MWh (www.energy-charts.info). Hence, we assume that in the hour of the lowest price, all cars charge at the maximum load, i.e., 11 kWh within one hour, and discharge the same amount in the most expensive hour. As the overall battery capacity and discharging power is higher than 11 kWh, respectively, 11 kW, this is a rather conservative estimate. Consequently, this simplified estimation leads to an average revenue per vehicle of about 1.22 EUR/day (i.e., 11 kWh multiplied by 111.2 EUR/MWh), which is a rather optimistic calculation assuming a suitable grid connection. In our case study of 220 EVSE, this equals about 188 EUR per working day for the whole site or close to 46,812 EUR/year. These revenues may change in the future when daily price spreads on wholesale markets increase due to higher shares of intermittent electricity generation by wind and solar energy [31,32].

The presented flexibility and revenue values represent an idealized upper-bound scenario that is based on simplified assumptions regarding battery capacities and state-of-charge levels. The numbers should be taken with care and give a first indication of potential revenues from flexible workplace charging. In the real world operational, technical, and market-related constraints might reduce the achievable potential significantly. Nevertheless, the qualitative interpretation of the results is unaffected.

5. Discussion and Limitations

The analysis was concentrated on data collected from EnBW AG’s facilities, with 100 EVSE designated for each location in Stuttgart (STU) and Karlsruhe (KAR). However, the site in Neckarwestheim (NWH) had only 20 EVSE. This discrepancy may have limited the representation of shift workers, potentially impacting the outcomes of the cluster analysis.

This investigation also did not differentiate between BEV and PHEV, incorporating both categories within its scope. Concurrently, the potential influence of employee tariffs on charging behavior (recharged energy amount) emerges as a significant consideration. Preferential charging rates may serve as a compelling incentive, encouraging employees to predominantly utilize workplace charging infrastructure for their vehicles. This observed behavior underscores the need for a critical examination of the average quantity of energy replenished, considering the diversity of the vehicle fleet and the nuanced implications of the charging tariffs.

Regarding sample size and its implications for wider applicability, it is crucial to recognize that our calculations use data from specific German workplace charging sites. This might not accurately reflect charging behaviors in different environments or geographical areas. To generalize the findings to a broader audience, it would be necessary to include data from a variety of locations. Workplaces in other countries or with fleet-dominated mobility (logistics hubs), irregular attendance (craft companies), or public-sector institutions may exhibit fundamentally different parking routines and incentive structures. Therefore, transferring the identified clusters to such workplace types requires cautious validation.

The quality of the charging data depended on how well the information was gathered from the charging infrastructure. Problems such as missing or incorrect data might have compromised the integrity of this study’s conclusions.

The approach to clustering analysis was founded on certain assumptions and oversimplifications. This includes the selection of clustering algorithms and the determination of the number of clusters. Choosing different methodologies or adjusting the parameters could yield varying outcomes.

External influences like weather conditions, traffic congestion, and personal preferences might affect charging habits. These elements were not accounted for in the study, which could lead to biased results.

Lastly, this study’s focus was on examining charging patterns over a defined period, such as a year. This limited scope might overlook broader trends or seasonal fluctuations in charging behavior.

6. Conclusions

In the course of this research, the charging behavior of employees was analyzed using an empirical dataset containing charging data from three locations of EnBW AG, totaling 23,990,400 entries, from which 37,238 charging events could be identified.

In summary, nine key findings emerged from the analysis:

- The employees under consideration can be divided into three main groups: shift workers, part-time workers, and full-time workers. Shift workers are divided into 8 or 12 h shift systems.

- The group of full-time employees and shift workers (early) dominates and contributes mainly to peak power demand due to their typical arrival time and charging behavior.

- The ratio of charging duration to parking duration, across all parking and charging events, is 55%, indicating that parking duration is significantly longer than charging duration.

- A charging point is used, on average, only 1.16 times per day in the context of employee charging.

- During a charging event, an average of 25.03 kWh is consumed.

- The utilization rate and charging power of a charging point play a significant role in the economic efficiency of charging stations.

- First estimates of potential revenues from bidding charging flexibility into electricity markets attract further analyses on V2G applications. Potential uses such as bidirectional charging or market-oriented operation, therefore, represent future research fields rather than validated outcomes of this study, as the underlying flexibility estimates are indicative and derived from an idealized assessment framework.

This leads to the following recommendations:

- Optimization of Charging Infrastructure: Employers should consider optimizing charging infrastructure to accommodate peak charging demands during typical arrival times of employees. This may involve increasing the number of charging stations or implementing smart charging solutions to manage charging load efficiently.

- Tailored Charging Solutions: Employers could offer tailored charging solutions to different user groups based on their charging patterns and requirements. This could include incentives for off-peak charging or reserved charging spaces for employees with longer charging needs, e.g., for Clusters 2, 3, 5, 6, and 8 (i.e., 63% of employers), single-phase charging operation per charging point is sufficient to adequately charge the vehicle. This results in economic potential for the establishment of charging stations while ensuring customer satisfaction.

These insights—and especially the provided open data—provide valuable starting points for future research. They enable the exploration of flexibilities in charging processes, adjustment of charging capacities as needed, and investigation of the potential of bidirectional charging given the long parking durations. For example, the identified patterns also support broader V2X concepts such as vehicle-to-building (V2B), where workplace-connected EVs could temporarily support building energy management during peak demand or grid constraints. The reproducible data and distributions of clusters identified through the Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) can serve as a basis for further scientific studies and analyses. In this way, the sustainable integration of electric vehicles can be systematically advanced to meet customer demands while enhancing the efficiency of electric vehicle charging.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, visualization, and writing—original draft preparation, R.O.; Conceptualization, writing—review and editing, and supervision, P.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received funding by the German Aerospace Center and by the EU Research & Innovation Project, DriVe2X, funded by the European Union under Grant agreement ID: 101056934.

Data Availability Statement

The underlying raw data contains personal and/or proprietary information and therefore cannot be shared publicly. Processed/aggregated datasets and synthetic profiles supporting the findings are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11506701. Additional de-identified excerpts may be provided upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank ChargeHere (an EnBW Group subsidiary) for providing the 2023 workplace-charging dataset and for operational support at the EnBW facilities in Stuttgart (STU), Karlsruhe (KAR), and the Neckarwestheim power plant (NWH).

Conflicts of Interest

Author Ronald Opoku was employed by EnBW AG and is now working with the Mercedes-Benz Mobility AG. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Mobility survey overview.

Table A1.

Mobility survey overview.

| Mobility in Germany 2016 | German Mobility Panel 2022 | SrV | Mobility Survey of the Federal Environment Agency | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | GER | GER | GER | GER (Berlin, Dessau-Roßlau, Bad-Elster, Langen, Messstellen) |

| Participants | No age restriction | Persons aged 10 years and older | No age restriction | Employees of the Federal Environment Agency |

| Time period | May 2016 until October 2017 | September 2021 until March 2022 | February 2018 until March 2020 | Between September and October 2017 |

| Survey period | Diary of journeys on a specific date | Route diary for one week (7 days) | Journeys on a specific key date (working day) | Online survey over the measurement period |

| Study design | Cross-sectional study | Longitudinal survey | Cross-sectional study | Cross-sectional study |

| Number of participants | 316,000 | 3906 | 186,832 | 805 |

| Number of trips per day and person | 3.1 | 2.94 | 3.0–3.8 | 1.82 (Commuting—5 day week) |

| Traffic volumes MIV (absolute count) | 1.77 | 1.53 | 0.9–2.34 (2.7–3.4 passenger cars only) | 0.58 |

| Traffic volume (%) MIV | 57% | 52% | 25.9–73.3% | 32.1% |

| Average daily distance per person and day | 39 km | 36 km | 20.4–43.7 km | - |

| Traffic performance MIV | 29 km | 26.6 km | 8.4–37.5 km | - |

| Traffic performance (%) MIV | 75% | 73% | 41.2–90.9% | - |

| Average path length | 12 km | 12.4 km | 5.3–13.7 km (6.4–19.5 km passenger cars only) | - |

| Average distance traveled to work | 16 km | 17 km | 7.3–28.8 km | 33.3 km |

| Activity duration per day | 6 h 12 min | - | - | - |

Appendix B

Figure A1.

Distribution of charging and parking duration over the day.

Appendix C

Figure A2.

Average charging power per EVSE over a day.

Appendix D

Table A2.

Cluster information.

Table A2.

Cluster information.

| Cluster | Mean Parking Start Hours (Decimal Hours) | Mean Parking Duration Hours (Decimal Hours) | Covariance Matrix | Group Size | Cluster Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8.23 | 4.83 | [0.9712881 0.1067833] | 7287 | 0.20 |

| [0.1067833 3.04631808] | |||||

| 2 | 7.67 | 8.47 | [1.29978141 −0.23482241] | 17,330 | 0.38 |

| [−0.23482241 1.12172684] | |||||

| 3 | 17.60 | 14.06 | [5.13208749 −5.14764533] | 1174 | 0.03 |

| [−5.14764533 7.19472071] | |||||

| 4 | 13.75 | 2.81 | [6.81292893 −0.36802233] | 3912 | 0.10 |

| [−0.36802233 1.77298274] | |||||

| 5 | 15.72 | 19.97 | [13.36962643 −4.27822762] | 734 | 0.02 |

| [−4.27822762 5.8774549] | |||||

| 6 | 21.13 | 8.54 | [0.04726944 −0.04947566] | 718 | 0.02 |

| [−0.04947566 0.06546445] | |||||

| 7 | 12.33 | 5.50 | [1.32665871 0.47643928] | 2334 | 0.07 |

| [0.47643928 4.3962794] | |||||

| 8 | 7.65 | 10.03 | [1.25573887 −0.90669518] | 3749 | 0.18 |

| [−0.90669518 3.43151423] |

Appendix E

Figure A3.

K-Means clustering (with x indicating the centroids).

Appendix F

Table A3.

Symbols and units used in GMM.

Table A3.

Symbols and units used in GMM.

| Symbol | Meaning | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| x | Observation vector containing parking start time and parking duration | [h], [h] |

| K | Number of GMM components (“clusters”) | - |

| Mixture weight of component i | - | |

| Mean vector of component i | [h], [h] | |

| Covariance matrix of component i | [h2] | |

| Multivariate normal distribution of component i | - | |

| Modeled probability density for observation x | - |

Table A4.

Symbols and units used in the K-Means model.

Table A4.

Symbols and units used in the K-Means model.

| Symbol | Meaning | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| J | Total variance (cost function) to be minimized | [h2] |

| K | Number of clusters | - |

| Data point (parking start time, parking duration) | [h], [h] | |

| Set of data points assigned to cluster j | - | |

| Centroid of cluster j | [h], [h] | |

| Squared distance between data point i and its centroid j | [h2] |

Appendix G

Table A5.

Resulting statistical differences between the empirical (confidential) data and the synthetic data after Monte Carlo simulation on zenodo for each GMM cluster.

Table A5.

Resulting statistical differences between the empirical (confidential) data and the synthetic data after Monte Carlo simulation on zenodo for each GMM cluster.

| Cluster | emp_mean_ start [decimal hours] | syn_mean_ start [decimal hours] | emp_mean_ duration [decimal hours] | syn_mean_ duration [decimal hours] | emp_var_start [decimal hours] | syn_var_start [decimal hours] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8.231 | 8.231 | 4.827 | 4.776 | 0.971 | 0.993 |

| 2 | 7.674 | 7.680 | 8.468 | 8.487 | 1.300 | 1.304 |

| 3 | 17.599 | 17.572 | 14.065 | 14.073 | 5.132 | 5.174 |

| 4 | 13.754 | 13.669 | 2.815 | 2.793 | 6.813 | 7.307 |

| 5 | 15.719 | 15.625 | 19.975 | 19.909 | 13.370 | 13.341 |

| 6 | 21.131 | 21.127 | 8.544 | 8.551 | 0.047 | 0.047 |

| 7 | 12.327 | 12.306 | 5.505 | 5.399 | 1.327 | 1.310 |

| 8 | 7.649 | 7.597 | 10.027 | 10.108 | 1.256 | 1.490 |

Table A6.

Resulting statistical differences between the empirical (confidential) data and the synthetic data after Monte Carlo simulation on zenodo for each GMM cluster.

Table A6.

Resulting statistical differences between the empirical (confidential) data and the synthetic data after Monte Carlo simulation on zenodo for each GMM cluster.

| Cluster | emp_var_duration [decimal hours] | syn_var_duration [decimal hours] | emp_corr [decimal hours] | syn_corr [decimal hours] | KS_p_start [decimal hours] | KS_p_duration [decimal hours] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.046 | 3.053 | 0.062 | 0.104 | 0.915 | 0.221 |

| 2 | 1.122 | 1.085 | −0.194 | −0.132 | 0.371 | 0.553 |

| 3 | 7.195 | 7.098 | −0.847 | −0.845 | 0.293 | 0.313 |

| 4 | 1.773 | 1.694 | −0.106 | −0.175 | 0.826 | 0.964 |

| 5 | 5.877 | 6.401 | −0.483 | −0.480 | 0.678 | 0.610 |

| 6 | 0.065 | 0.067 | −0.889 | −0.889 | 0.562 | 0.306 |

| 7 | 4.396 | 4.032 | 0.197 | 0.179 | 0.639 | 0.306 |

| 8 | 3.432 | 3.613 | 0.605 | −0.132 | 0.007 | 0.707 |

References

- Press and Information Office of the Federal Government. Nachhaltige Mobilität. Available online: https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/schwerpunkte/klimaschutz/nachhaltige-mobilitaet-2044132 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- International Energy Agency. Global EV Outlook 2025. Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/7ea38b60-3033-42a6-9589-71134f4229f4/GlobalEVOutlook2025.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Jochem, P.; Gnann, T.; Anderson, J.E.; Bergfeld, M.; Plötz, P. Where Should Electric Vehicle Users Without Home Charging Charge Their Vehicle? Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 2022, 113, 103526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zugehör, D. E-Mobilität BDEW Warnt: 15-Millionen-Ziel Wird Verfehlt; Energate GmbH: Essen, Germany, 2023; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Heinen, R.-D. DIW-Studie Ampel-Ziele für E-Autos und Elektrolyseure Weit Entfernt. Available online: https://www.energate-messenger.de/news/238697/ampel-ziele-fuer-e-autos-und-elektrolyseure-weit-entfernt (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Guo, F.; Yang, J.; Lu, J. The Battery Charging Station Location Problem: Impact of Users’ Range Anxiety and Distance Convenience. Transp. Res. E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2018, 114, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Liu, C.; Lin, Z. Charging Infrastructure Planning for Promoting Battery Electric Vehicles: An Activity-Based Approach Using Multiday Travel Data. Transp. Res. C Emerg. Technol. 2014, 38, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The National Centre for Charging Infrastructure. Einfach Laden Das Ladeerlebnis als User Journey an Öffentlichen Ladestationen für Elektrofahrzeuge Jetzt und 2025. Available online: https://nationale-leitstelle.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Thesenpapier_Einfach-laden.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Nobis, C.; Kuhnimhof, T. Mobilität in Deutschland—MiD Ergebnisbericht; Bundesministers für Verkehr und digitale Infrastruktur: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 1–136. [Google Scholar]

- Schaeuble, J.; Kaschub, T.; Ensslen, A.; Jochem, P.; Fichtner, W. Generating Electric Vehicle Load Profiles from Empirical Data of Three EV Fleets in Southwest Germany. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 150, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schücking, M.; Jochem, P.; Fichtner, W.; Wollersheim, O.; Stella, K. Charging Strategies for Economic Operations of Electric Vehicles in Commercial Applications. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 2017, 51, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Märtz, A.; Langenmayr, U.; Ried, S.; Seddig, K.; Jochem, P. Charging Behavior of Electric Vehicles: Temporal Clustering Based on Real-World Data. Energies 2022, 15, 6575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friese, P.A.; Michalk, W.; Fischer, M.; Hardt, C.; Bogenberger, K. Charging Point Usage in Germany—Automated Retrieval, Analysis, and Usage Types Explained. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, C.; Das, S.; Bussar, C.; Sauer, D.U. Representative, Empirical, Real-World Charging Station Usage Characteristics and Data in Germany. eTransportation 2020, 6, 100079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmus, J.R.; Lees, M.H.; Van Den Hoed, R. A Data Driven Typology of Electric Vehicle User Types and Charging Sessions. Transp. Res. C Emerg. Technol. 2020, 115, 102637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straka, M.; Buzna, L. Clustering Algorithms Applied to Usage Related Segments of Electric Vehicle Charging Stations. Transp. Res. Procedia 2019, 40, 1576–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crozier, C.; Apostolopoulou, D.; McCulloch, M. Clustering of Usage Profiles for Electric Vehicle Behaviour Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference Europe (ISGT-Europe), Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 21–25 October 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Flammini, M.G.; Prettico, G.; Julea, A.; Fulli, G.; Mazza, A.; Chicco, G. Statistical Characterisation of the Real Transaction Data Gathered from Electric Vehicle Charging Stations. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2019, 166, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolbertus, R.; Van Den Hoed, R.; Maase, S. Benchmarking Charging Infrastructure Utilization. World Electr. Veh. J. 2016, 8, 754–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usmani, O.A.; Morales-España, G. ChaProEV: Generating Charging Profiles for Electric Vehicles. SSRN 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaete-Morales, C.; Kramer, H.; Schill, W.-P.; Zerrahn, A. An Open Tool for Creating Battery-Electric Vehicle Time Series from Empirical Data, Emobpy. Sci. Data 2021, 8, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagani, M.; Korosec, W.; Chokani, N.; Abhari, R.S. User Behaviour and Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure: An Agent-Based Model Assessment. Appl. Energy 2019, 254, 113680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddig, K.; Jochem, P.; Fichtner, W. Two-Stage Stochastic Optimization for Cost-Minimal Charging of Electric Vehicles at Public Charging Stations with Photovoltaics. Appl. Energy 2019, 242, 769–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 61851-1; Electric Vehicle Conductive Charging System—Part 1: General Requirements (Publication No. 33644). IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. Available online: https://webstore.iec.ch/publication/33644 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Santoso, H.A.; Haw, S.-C. Improvement of K-Means Clustering Performance on Disease Clustering Using Gaussian Mixture Model. J. Syst. Manag. Sci. 2023, 13, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, E.; Kushwaha, D.S. Clustering Cloud Workloads: K-Means vs Gaussian Mixture Model. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 171, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, T.; Tao, X.; Li, L.; Higgins, N.; Gururajan, R.; Zhou, X.; Yong, J. Clustered FedStack: Intermediate Global Models with Bayesian Information Criterion. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2024, 177, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonakdari, H.; Zeynoddin, M. Goodness-of-Fit & Precision Criteria. In Stochastic Modeling; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 187–264. ISBN 978-0-323-91748-3. [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro De Amorim, R.; Makarenkov, V. On K-Means Iterations and Gaussian Clusters. Neurocomputing 2023, 553, 126547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Motor Transport Authority. Bestand an Kraftfahrzeugen und Kraftfahrzeuganhängern nach Herstellern und Handelsnamen, 1. Januar 2023 (FZ 2). Available online: https://www.kba.de/DE/Statistik/Fahrzeuge/Bestand/MarkenHersteller/marken_hersteller_node.html (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Ballester, C.; Furió, D. Effects of Renewables on the Stylized Facts of Electricity Prices. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 52, 1596–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rintamäki, T.; Siddiqui, A.S.; Salo, A. Does Renewable Energy Generation Decrease the Volatility of Electricity Prices? An Analysis of Denmark and Germany. Energy Econ. 2017, 62, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.