Abstract

Indonesia faces growing pressure to strengthen waste management while expanding renewable energy generation, particularly from high-moisture biomass such as palm oil mill effluent (POME) and the organic fraction of municipal solid waste (OFMSW). Anaerobic digestion technology (ADT) is technically suitable for both feedstocks; however, its deployment depends on broader operational, financial, social, and institutional conditions. This study evaluates ADT readiness for biomass waste-to-energy (BWTE) development in Indonesia using a multistakeholder Japanese Technology Readiness Assessment (J-TRA) framework. The results and discussion are supported by a literature review, secondary data analysis, and interviews with government agencies, industry actors, financiers, non-governmental organizations, and researchers. The results reveal a clear divergence in readiness outcomes. POME-based ADT reaches Technology Readiness Levels (TRLs) of 6–8, supported by a stable and homogeneous feedstock supply, established industrial operations, and corporate incentives to mitigate methane emissions. Key remaining constraints relate to high capital costs for smaller mills, low electricity purchase tariffs, and competing export incentives for untreated POME. In contrast, OFMSW-based ADT remains at TRL 2–4, constrained by inconsistent waste segregation, insufficient operation and maintenance capacity, limited municipal budgets, residential safety concerns, and fragmented governance across waste and energy institutions. Across both cases, readiness is shaped by five interacting forces. The first three are technical: feedstock characteristics, operations and maintenance (O&M) capability, and financial certainty. The remaining two are enabling conditions: social acceptance and institutional coordination. This study concludes that Indonesia’s BWTE transition requires integrated technological, behavioral, and policy interventions, supported by further research on hybrid valorization pathways and context-specific life-cycle and cost analyses.

1. Introduction

In the waste management category of the 2024 Yale Environmental Performance Index, Indonesia ranked 122nd out of 180 countries. In comparison, Singapore, as its closest neighbor, ranked first, followed by Japan and Sweden [1]. This index uses indicators such as municipal solid waste generated per capita, controlled solid waste, and the recovery of energy and materials from waste [1], making it a relevant measure of waste-to-energy (WTE) capacity. However, this index represents only one of many portrayals of Indonesia’s waste situation that indicate the need for improvement.

At the same time, clean and accessible energy presents another major challenge. Indonesia remains heavily reliant on fossil fuels. This reliance prompted the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources of Indonesia (Kementerian Energi dan Sumber Daya Mineral/KESDM) to mandate B40 biodiesel blending in 2025 and B50 in 2026 (40% and 50% biodiesel, respectively, with fossil-based fuel comprising the remainder). These mandates aim to support the 23% new and renewable energies target by 2030 [2] and the net-zero emissions target by 2060 [3]. The policy is also intended to mobilize Indonesia’s estimated 57 gigawatts (GW) of bioenergy potential. However, by the end of June 2025, only 5.5% of this potential had been realized, even when bioavtur, biodiesel, and bioethanol are included alongside biomass. Higher biodiesel blending also increases the production of carbon-rich glycerol. Such by-products are effective substrates for biogas generation using anaerobic digestion technology (ADT) [4,5], further optimizing the role of waste as an energy resource [4,5].

Indonesia has sought to address these challenges through successive policy initiatives. Law No 23/2014 on local government roles in waste management included provisions for electricity generation permits from waste through private sector support [1]. Presidential Regulation No 35/2018 formally introduced WTE as a policy concept and targeted engineering and implementation in 12 major cities [1]. However, only Solo and Surabaya realized this target. More recently, the 2045 Indonesia Long-Term National Development Plan (Rencana Pembangunan Jangka Panjang Nasional/RPJPN) set a target of treating 55% of national waste using material and energy recovery technologies [1], under the so-called ‘Golden Indonesia Vision’. Nevertheless, progress has been criticized as slow. In March 2025, President Prabowo identified the unreadiness of local governments as an urgent call to accelerate not only technological maturity but also human capacity, cost structures, and governance arrangements [1,2].

Institutionally, Danantara Indonesia (DI), the government’s sovereign wealth fund, now prioritizes WTE investments targeting facilities with a capacity of 1000 tons of waste per day [2,6]. These investments include biomass and biogas from both industrial and household sources. KESDM remains the permit-granting agency, while the State Electricity Company of Indonesia (Perusahaan Listrik Negara/PLN) serves as the offtaker [2]. These efforts are embedded within a broader circular bioeconomy agenda that seeks to convert biomass into bio-based products and fuels [7,8]. Such biomass-based waste systems help provide low-cost energy access and livelihoods for urban, rural, and coastal communities [7].

Technologically, Indonesia and much of Southeast Asia are characterized by organic waste with high moisture content and low calorific value [6], which makes thermal incineration relatively unsuitable. Instead, biochemical treatments such as anaerobic digestion technology (ADT) are more appropriate [9], particularly for liquid agricultural waste [3]. More than 30,000 ADT plants were established across 10 provinces between 2012 and 2018. This expansion was enabled by a 20-year feed-in tariff (FIT) scheme set below JPY 19 per kWh for biogas plants under 1 MW [8]. Nevertheless, deployment has fallen short of expectations, particularly when feedstock availability and system integration are considered [10]. The national target is to install at least 300,000 digesters under a multi-ministerial plan [10].

From a waste perspective, the Ministry of Environment of Indonesia (Kementerian Lingkungan Hidup/KLH) reported that Indonesia generated 33.8 million tons of waste in 2024. Half of this originated from households, and one-third consisted of food waste, usually termed the organic fraction of municipal solid waste (OFMSW) [1,2], of which 40% is untreated [2]. Wet organic food waste, including household kitchen residues and traditional market waste, has a moisture content of 60–80%, which is higher than that of other OFMSW types, such as yard or garden waste (30%) and paper or cardboard (20%). This is largely due to Indonesians’ tendency to mix solid and liquid household waste. As a result, OFMSW accounts for the largest share of Indonesia’s municipal solid waste (MSW), at 40–60%. Although highly contaminative if unmanaged, OFMSW is also a significant source of waste-based energy potential [11]. For instance, previous studies estimated an electricity production potential of 35.1 MWh/day for a 50-ton plant treating OFMSW [12,13]. Additionally, each ton of OFMSW has the potential to yield 82 Nm3 of biogas [12,13], equivalent to 586 Nm3 of methane per ton of volatile solids (VS) under ADT conditions [12,13]. However, a recent study by Yap et al. demonstrated that without pretreatment, VS reduction remains below 50% [14].

In parallel, Indonesia is the world’s largest palm oil producer, accounting for 57% of global output, with an export value of USD 25.6 billion and employing 16.2 million people [3]. However, only 25% of each palm fruit becomes oil; the remainder becomes waste, including palm oil mill effluent (POME), which represents one of the most methane-intensive industrial organic waste streams in Southeast Asia [15]. Untreated POME discharge is one of the largest contributors to the industry’s emission profile [2,3,8,11]. Along with empty fruit bunches (EFB) and palm kernel shells (PKS), POME is among the most common feedstocks used to generate biomass WTE [8]. By 2020, at least nine biomass energy projects from the palm oil sector had been identified [8].

This study therefore focuses on POME (not EFB or PKS) and OFMSW (excluding inorganic waste) as two high-moisture, socio-economically significant feedstocks that share biochemical suitability for ADT. However, this study considers differences in scale, governance, and institutional context. POME is treated by industrial-scale palm oil mills, whereas OFMSW is treated at the community scale, primarily by households. This contrast in outputs provides an opportunity to examine new insights, such as common factors differentiating their readiness despite identical ADT processes. This research investigates POME and OFMSW as separate systems due to their distinct socio-technical characteristics. Accordingly, two separate ADT readiness analyses are conducted to provide insights into linkages between POME and OFMSW feedstocks.

Against this backdrop, a systemic assessment of ADT deployability and scalability in Indonesia is deemed necessary. In a 2020 study, Pandyaswargo et al. [8] evaluated biomass energy technological readiness in Southeast Asia. Building on this work, the present study focuses on biomass waste-to-energy (BWTE) using ADT and compares two contrasting feedstocks in Indonesia, Southeast Asia’s largest economy. A multistakeholder approach is applied to analyze the readiness of technical-operational and systemic enabling conditions. In doing so, this study aims to clarify why ADT matures successfully in some contexts but remains constrained in others, and how policy, market, and social factors shape these outcomes.

2. Literature Review

In developing countries, waste-to-energy (WTE) is considered an integrated approach to managing municipal solid waste. It can address untreated waste while expanding access to locally sourced renewable energy. Across Asian, African, and Latin American regions, small- and medium-scale WTE systems include community-operated biogas digesters, agricultural residue gasification units, and modular ADT facilities. These systems have been deployed to generate heat, cooking fuel, and electricity from locally available organic waste streams [16,17,18]. They are often favored because they align with existing biomass practices and can be embedded in local waste chains [19,20,21]. In practice, they also involve more manageable operational requirements and investment levels than large-scale incineration facilities [19,20,21].

However, the long-term sustainability of WTE adoption in developing contexts remains shaped by several interrelated challenges. The characteristics of high-organic, high-moisture municipal waste require additional preprocessing steps to maintain stable operation [22,23], which frequently leads to reduced conversion efficiency [22,23]. Economic feasibility is also influenced by electricity offtake agreement security, tariff structures, and the availability of reliable subsidy or incentive mechanisms [24,25]. Equally critical is community engagement. WTE projects tend to achieve greater operational persistence when local actors are involved in planning and derive clearly distributed benefits [26,27,28]. Conversely, projects introduced through top-down implementation often face resistance or fail to integrate into everyday waste practices [26,27,28].

Beyond technical and socio-economic considerations, the policy and institutional setting play a formative role in determining WTE outcomes. Countries that have successfully expanded WTE capacity typically exhibit coordinated governance arrangements between municipal waste authorities and national energy regulators [29,30]. Such alignment is lacking when municipal governments manage waste while national entities control electricity procurement, resulting in project delays, underutilization, or discontinuation [27,31].

These dynamics closely reflect the situation in Indonesia. On the one hand, municipal waste streams are dominated by high-moisture organics, with waste management responsibilities decentralized to local governments. On the other hand, electricity procurement is centrally administered by PLN [24,29]. This structural separation of responsibilities means that successful WTE adoption depends not only on technological maturity but also on the degree to which systems can be locally operated, financed, socially accepted, and institutionally supported [28,30].

The key developmental patterns identified in the literature are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key WTE adoption barriers in developing countries and their relevance to Indonesia.

The literature demonstrates that WTE deployment in Indonesia is shaped by interdependent technical, economic, social, and institutional conditions. In other words, adoption depends not only on technological performance but also on embedding systems within local operational practices, governance structures, and community expectations. Prior analyses of biogas and WTE programs in emerging Asia similarly emphasize that project sustainability hinges on implementation readiness rather than technology alone [32]. Related work on energy and mobility transitions in Indonesia shows that such readiness is multistakeholder and socio-institutional in nature, requiring alignment among government agencies, operators, private actors, and end-users [33]. Previous studies have sought to address these challenges, but a gap remains in comprehensively evaluating this multi-dimensional system from a multistakeholder perspective.

To address this, the Japanese Technology Readiness Assessment (J-TRA) framework is utilized due to its ability to evaluate technical maturity, operational feasibility, financial viability, governance structure, and social acceptance in deployment settings [34]. It accommodates different actor perspectives to provide a clearer picture of the systemic context. It is important to note that J-TRA is not a standalone tool; rather, its contextualization is strengthened through cross-referencing data with the literature [35]. Accordingly, this study applies the J-TRA framework to assess the readiness of selected BWTE pathways in Indonesia and to identify conditions for their context-appropriate and sustainable implementation.

3. Materials and Methods

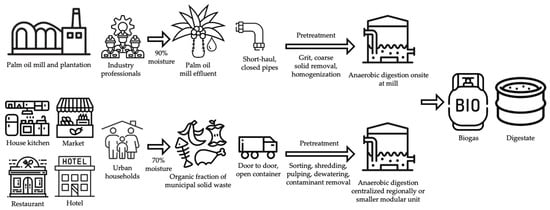

This section is divided into two parts. The first explains the operational processes of ADT for both feedstocks using a simple flow diagram showing source location, feedstock characteristics, transport, and ADT positioning. This clarifies the scope of the research. The second part describes the methodological framework and data required to analyze ADT maturity.

3.1. Operational Scope

Figure 1 shows the simplified ADT flow for both feedstocks, encompassing feedstock sources, feedstock generators, feedstock characteristics, material transportation, ADT positioning, and resulting products. The diagram illustrates the similar application of ADT across two contrasting feedstock cases. Despite similar waste moisture levels, these contrasts lead to different process performance and output efficiencies. This study collects and analyzes data from both cases while accounting for their unique challenges.

Figure 1.

ADT operational scope for POME and OFMSW feedstocks. Source: Created by the authors based on the literature review and interviews.

When waste materials such as biomass, plastics, and organic residues are subjected to high-temperature chemical processes to recover useful energy and resources, advanced waste valorization occurs [36,37]. Similarly, biochemical pathways represent an advanced form of valorization for organic waste streams by reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, producing renewable energy, and supporting circular economy transitions [36,37]. These biochemical processes rely on microorganisms and enzymes to break down complex organic molecules into biogas and biofuels [37].

Prior studies, such as Haldar et al. [38], emphasize that waste management systems should be understood as integrated techno-social systems to move beyond disposal-oriented approaches toward circular bioeconomy outcomes. Onoda [39] further notes that the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the re-examination of waste treatment practices, particularly for biomass and health-sensitive waste streams, while also prompting broader reflection on energy systems under increasing digitalization. Although implementation challenges remain, several waste-to-energy technologies are increasingly aligned with sustainability and circularity objectives [36,37].

ADT represents one such pathway. It operates under oxygen-deprived conditions, enabling microorganisms to convert organic matter into methane-rich biogas composed mainly of CH4 and CO2. Similarly to thermochemical processes such as pyrolysis, ADT functions without oxygen; however, it also produces digestate, which can be utilized as a biofertilizer to improve soil quality and crop yields [36,37,40]. ADT further contributes to reduced eutrophication and acidification impacts [41]. Its performance is strongly dependent on feedstock characteristics and microbial stability.

Biomass energy conversion differs conceptually from MSW incineration. Biomass-based pathways focus on forestry products, agricultural residues, and organic waste, whereas incineration mixes waste streams and remains inefficient for high-moisture organic materials [42,43].

3.2. Methodological Framework and Data

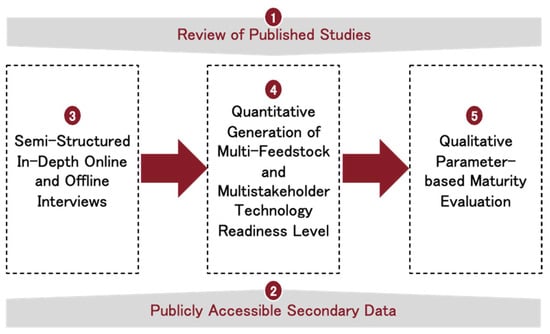

This research employs five interlinked methods, as summarized in Figure 2, which shows the overall stepwise framework.

Figure 2.

Stepwise research framework.

The first two methods constitute the continuously overarching component of the methodology, while the last three represent the dynamic component of data and insight collection. Through this framework, this study addresses the maturity of the technology in question. The following subsections describe the activities conducted at each step of the framework.

3.2.1. Review of Published Studies

More than 75 public academic and policy publications were reviewed to consolidate current knowledge on ADT applied to POME and OFMSW, particularly, though not exclusively, in Indonesia. Google Scholar, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, and IEEE Xplore platforms were used to identify relevant publications. Search keywords included “anaerobic digestion”, “biomass waste-to-energy”, “palm oil mill effluent”, “organic fraction of municipal solid waste”, “technology readiness”, and “Indonesia”.

Although ADT is one of the oldest biochemical technologies for BWTE processing [32], only papers published from 2015 onwards were included to reflect the relevance of the Paris Agreement in addressing sustainability and the climate crisis. Non-English and non-journal-based articles were excluded. While no journal-ranking filter was applied, some articles were excluded due to limited access. Abstracts were reviewed to assess relevance. Policy sources, regulatory documents, and official presentation materials were reviewed alongside peer-reviewed journal articles.

Key information synthesized from the literature forms the foundation of this research. Following Giordano et al., a partially automated approach was used to identify keywords [35], enhancing objectivity in processing the selected literature. This research aims to provide critical reasoning to support Indonesia’s continued expansion of WTE systems. In addition, it seeks to identify key barriers to acceleration and to clarify priority actors and roles required to improve WTE maturity in Indonesia.

3.2.2. Secondary Data

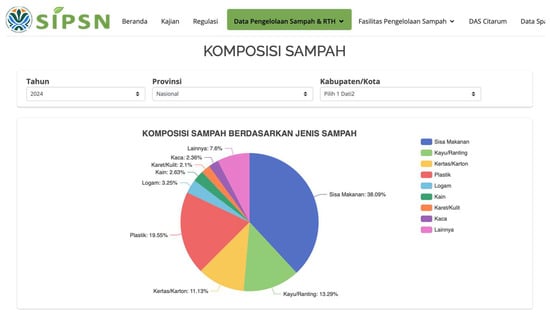

Secondary data were gathered from publicly accessible digital platforms and included data on energy and waste quantities, composition, and sources, as well as palm oil industry and household consumption statistics. An example of such secondary data is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Indonesia’s waste profile in 2024, based on KLH SIPSN data. Source: National municipal solid waste data obtained from the SIPSN database (accessed on 10 November 2025).

These data informed the design of interview questions for primary data collection. The full list of questions is provided in the Appendix A and Appendix C, where relevant, additional data were gathered to validate the primary data.

3.2.3. Primary Data and Interviews

Primary data were collected through semi-structured, in-depth offline and online interviews with relevant Indonesian government, business, and research stakeholders [8]. Respondents were carefully selected based on expertise alignment and direct accessibility. Current occupational relevance was also considered to ensure the credibility of information and to minimize potential biases.

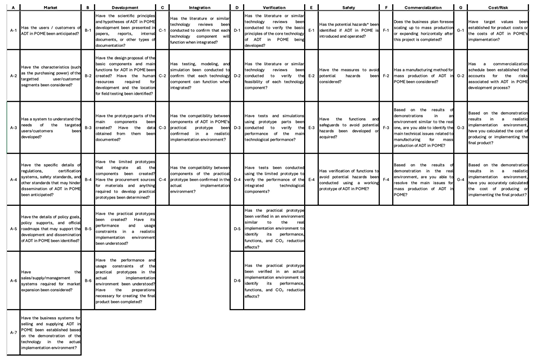

TRA was originally developed in the United States and later adapted in Japan as J-TRA. J-TRA was selected because it is suitable for evaluating technologies in Indonesia and Southeast Asia [33,34]. Interviews followed J-TRA guidelines and involved 7 parameters: market, (technology) development, (technology) integration, verification, safety, commercialization, and cost/risk. Each parameter comprised a distinct set of interview questions. To evaluate these parameters, a total of 35 binary questions were asked of each respondent [8]. Respondents were required to answer either yes or no. Each yes response led to the next question within the same parameter until all questions were completed, whereas each no response led to the first question of the subsequent parameter. Unclear or conflicting responses were clarified with respondents when necessary to minimize uncertainty. Throughout the interviews, questions validating respondents’ backgrounds and their relevance to BWTE were also included. Interviews were concluded only after missing data points had been addressed.

To minimize the risk of losing insights through oversimplified interpretation, respondents’ nuanced views are discussed in Section 4, where relevant. Each respondent was anonymized, and following verbal consent, most interviews were audio-recorded. Limited datasets are shareable upon verification request.

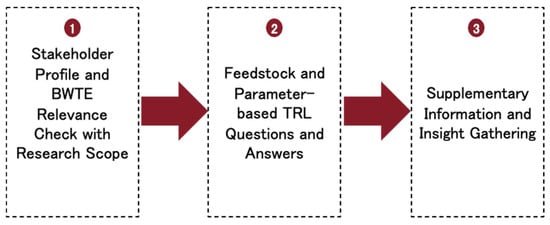

Figure 4 illustrates the interview flow.

Figure 4.

Interview process for ADT TRL readiness.

Table 2 presents the profiles of J-TRA respondents for the POME feedstock, including stakeholder type, relevance to the study, interview date, and duration. The second column describes position titles, years of related experience, and topic-relevant work. Each respondent type is assigned a “response code,” where “S” stands for stakeholder, “PE” represents POME, and the final letter (R, N, F, B, G, or L) represents the stakeholder type. For instance, “SPE-R” represents a researcher stakeholder for the POME feedstock, while “SPE-N” represents an NGO stakeholder.

Table 2.

Profiles of J-TRA respondents for POME-based ADT in Indonesia.

Using the same principle, similar information is presented in Table 3 for the OFMSW feedstock. The only differences are the second and third letters in the response code, where “OM” represents OFMSW. For example, “SOM-R” represents a researcher stakeholder for the OFMSW feedstock, while “SOM-N” represents an NGO stakeholder.

Table 3.

Profiles of J-TRA respondents for OFMSW-based ADT in Indonesia.

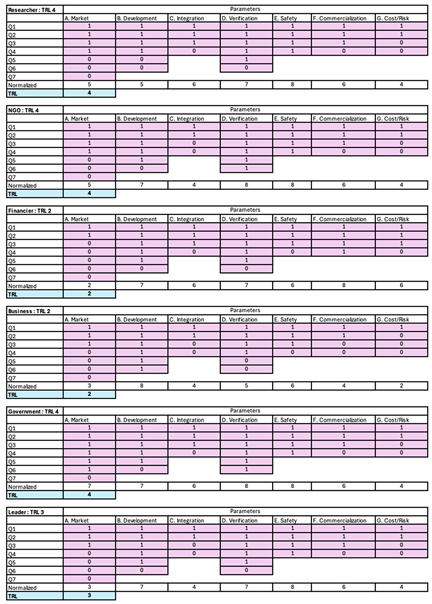

3.2.4. Coding and TRL Calculation

Responses were translated into binary (yes = 1, no = 0) values for each parameter in the J-TRA tool by the same interviewer. Because the respondents did not fill out written questionnaires, all binary values were derived from the content of the in-depth discussion with the interviewer. This process produced two Technology Readiness Level (TRL) radar charts, ranging from level 1 (least ready) to level 8 (most ready), for POME and OFMSW feedstocks. Each chart incorporated data from multiple respondents; therefore, multistakeholder TRLs were represented using color-coded lines for different stakeholder groups. Normalization was conducted by summing values for each parameter and multiplying them by the proportion of questions relative to the 8 TRLs [8,33,34]. The final TRL for each stakeholder was determined using the minimum function in Microsoft Excel. The full interview questions, data entry process, and chart-generation tool are shown in the Appendix A, Appendix B, Appendix C and Appendix D.

3.2.5. Analysis and Synthesis

The TRL results were analyzed across feedstocks and stakeholder perspectives and are presented in Section 4. In addition to stakeholder attribution, Section 4 also draws on the existing literature discussed in Section 2 and secondary national databases. This is intended to inform TRL interpretation and support empirical analysis. Section 5 then discusses the meaning of such technological readiness and introduces a refined framing, implications for decision makers, and recommended scenarios. Section 6 concludes the technological readiness evaluation.

Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) was used primarily to support keyword identification in the literature review. This aligns with the 2024 study by Giordano et al. on the automated extraction and validation of keywords during secondary data collection [35]. During the writing process, GenAI was also occasionally used to support the correction of grammatical errors.

4. Results

This section presents an empirical assessment of TRLs for ADT treating POME and OFMSW in Indonesia. TRL scores were derived from observed technical–operational conditions and systemic enablers identified through interviews and document analysis. Interpretive analysis of the drivers, barriers, and implications for technological readiness is presented in Section 5.

4.1. Technology Readiness of Anaerobic Digestion for POME

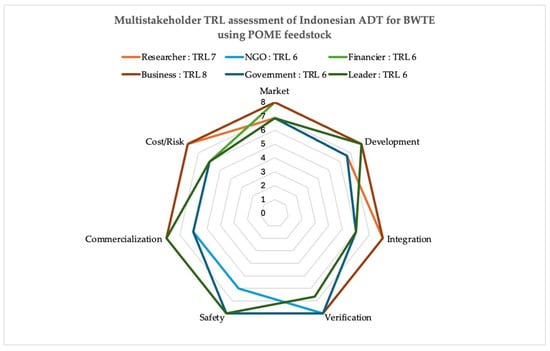

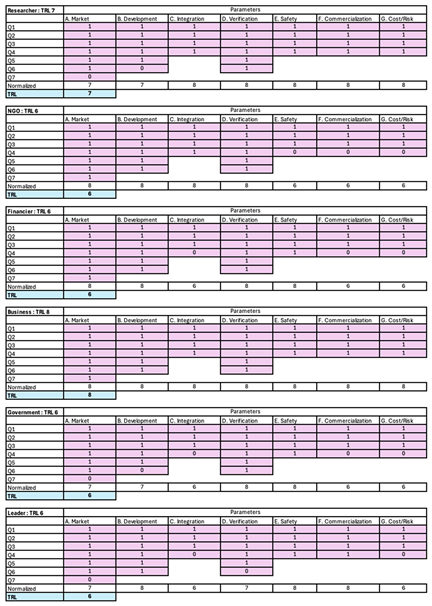

Figure 5 presents the TRL assessment results for ADT applied to POME in Indonesia, as derived from the J-TRA-based interviews described in Section 3. Six stakeholder groups were involved: researcher (SPE-R), NGO (SPE-N), financier (SPE-F), business (SPE-B), government (SPE-G), and sector leader (SPE-L). Differences in perceived readiness across parameters reflect each stakeholder’s institutional role, exposure to risk, and level of operational involvement.

Figure 5.

Multistakeholder TRL assessment of Indonesian ADT for BWTE using POME feedstock.

In normalized TRL terms, Figure 5 shows that the median scores for the verification and safety parameters are close to the maximum TRL of 8, with only two respondents assigning a TRL of 6 for each parameter. Similarly, for the development parameter, only two respondents assigned a TRL of 7. For the integration and commercialization parameters, respondents were evenly split between TRL 6 and TRL 8. A similar pattern is observed for the market parameter, but with scores distributed between TRL 7 and TRL 8. The cost/risk parameter exhibits the lowest overall normalized readiness, with four respondents assigning a TRL of 6.

4.1.1. Technical–Operational Readiness of ADT for POME

Across interviews, stakeholders consistently identified three dominant sources of GHG emissions in palm oil operations: land-use change, palm cultivation on peatlands, and untreated POME. Compared with the first two sources, POME treatment through ADT was repeatedly described as the most technically and operationally tractable decarbonization option. This is reflected in high verification-related TRL scores, as GHG monitoring and reporting methods for ADT systems are well established.

SPE-N emphasized that ADT for POME is already well known within the industry, with key system components largely in place. This assessment is reflected in Figure 5, where four stakeholder groups converge around an average TRL of 6, while SPE-R and SPE-B assess higher readiness levels at TRL 7 and TRL 8, respectively. Several large palm oil companies operating in regions such as Belitung and West Sumatra have deployed ADT systems since approximately 2012. Some of these projects were previously registered under the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), indicating relatively high market-related readiness.

One notable issue raised by SPE-R with respect to development-related readiness concerned the improvement of cover lagoon systems, specifically the transition from open, less controllable designs to closed systems. Such improvements would also enhance integration-related readiness by aligning ADT implementation with the latest Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) certification standards, as described later in Table 4.

4.1.2. Systemic Enablers Affecting ADT Readiness for POME

Despite this relatively high level of technological maturity, gaps remain across several readiness parameters, most notably commercialization and safety. High upfront investment costs were the most frequently cited constraint, indicating gaps in the cost- and risk-related readiness. SPE-N noted that commonly deployed ADT systems are supplied by technology providers from Germany and China, with capital expenditures typically ranging from IDR 20 to 30 billion. SPE-F stressed that while these costs are manageable for medium and large companies, they remain prohibitive for smaller mills, thereby limiting widespread replication across Indonesia’s more than 1,500 palm oil mills.

In certain remote areas, such as Belitung, SPE-R reported cases in which surplus electricity generated from biogas has been sold to PLN. However, low purchase prices were widely viewed as a weak incentive, reinforcing SPE-R’s observation that PLN prioritizes lowest-cost electricity procurement. SPE-L further noted early-stage exploration of selling biogas to the State Gas Company of Indonesia (Perusahaan Gas Negara/PGN), although the economic feasibility of this option remains uncertain despite its technical viability. These alternative utilization pathways nonetheless strengthen the circularity potential of ADT applied to POME.

From an institutional perspective, stakeholders highlighted that although ISPO certification and several Ministerial Regulations mandated POME treatment, no specific treatment technologies, including ADT, are explicitly required or recommended. Beyond the risk of inconsistent compliance by palm oil companies, stakeholders also raised concerns regarding weak regulatory enforcement. Although empirical studies assessing enforcement effectiveness remain limited, Lim and Biswas demonstrated that regulatory requirements related to ADT, together with implementation barriers, significantly influence actual compliance and POME-related environmental performance [44]. Table 4 summarizes the influence of national regulations and international standards on POME management, distinguishing mandatory policy instruments from voluntary, market-based mechanisms.

Table 4.

International and national standards affecting POME management in Indonesia [45,46,47,48].

Table 4.

International and national standards affecting POME management in Indonesia [45,46,47,48].

| Name of Standard | POME Treatment Requirements | Country of Origin |

|---|---|---|

| Voluntary, market-based. Its Principles and Criteria (P&C) in 2018 asked for better POME management to reduce GHG and recycle water nutrients. This includes improved use of ADT or lagoon and monitoring impacts. | Malaysia |

| Mandatory, policy-driven. POME managed to meet legal wastewater and land-application needs. It shifts from uncontrolled open to closed covered lagoons. Law enforcement must consistently be stressed. | Indonesia |

| Mandatory, policy-driven. Focuses on pollutant discharge nuisance and POME quality following available technology and control. Failure to comply leads to administrative fines. | Indonesia |

| Voluntary, market-based. Guides mill residues, GHG accounting, and sustainable use. Stricter traceability applied with a focus on auditing to ensure no double-counting. | Germany |

| Mandatory only for EU importers. POME limits are not set; it instead focuses on due diligence, traceability information, and regulatory checks. Indirectly affects POME management. | European Union |

Complementary incentive schemes, such as the Ministry of Environment (KLH)’s corporate-focused Public Disclosure Program for Environmental Compliance (Program Penilaian Peringkat Kinerja Perusahaan dalam Pengelolaan Lingkungan Hidup/PROPER), follow a similar non-mandatory approach. While climate finance opportunities exist to alleviate capital constraints, SPE-F emphasized that access conditions, financing structures, and payback periods remain decisive factors shaping adoption decisions.

Regarding the safety parameter, stakeholders generally agreed that ADT, as a technology, is mature. However, SPE-N acknowledged isolated incidents involving operational failure, human error, or sabotage that resulted in untreated POME discharge and posed risks to surrounding communities. This, in turn, reinforces the research focus of SPE-R, which has shifted from basic implementation toward improving biogas conversion efficiency and accelerating the transition from open lagoons to closed or covered systems. SPE-R interpreted this shift as evidence of TRL 7-level maturity, supported by patented components, standardized safety procedures, and the on-site availability of feedstock, which minimizes transportation-related risks.

Commercialization prospects were considered closely linked to policy and market design. SPE-R and SPE-F both pointed to the potential role of carbon credit mechanisms in improving ADT value propositions, although the minimum investment threshold of IDR 20–30 billion effectively confines economic viability to medium and large operations. SPE-B reinforced this assessment. SPE-N therefore argued that ADT for POME is no longer constrained by technical readiness but rather by corporate willingness and alignment with broader decarbonization incentives.

SPE-B stated that low feed-in tariffs (FITs) continue to discourage grid export, reinforcing a preference for internal energy utilization. Listiningrum et al. found that uncertain regulatory frameworks and unstable FIT or power-purchase agreement (PPA) incentives inadequately support the economic viability of POME-based biogas systems [49]. Improving these incentives relative to fossil-based and other renewable alternatives is therefore required. Such adjustments could attract greater private investment and improve commercialization and cost/risk readiness by scaling up POME-based ADT deployment for electricity exports [49,50].

SPE-L and SPE-F cautioned that overseas markets, such as the European Union, have projected increased demand for untreated POME feedstocks to meet regional sustainable aviation fuel production targets. When priced attractively, exports of untreated POME or POME-derived products from Indonesia could weaken incentives to invest in domestic ADT deployment. Hayyat et al. highlighted that exporting organic residues without prior methane stabilization risks shifting emissions across borders rather than achieving genuine mitigation [15]. Moreover, recent increases in European Union POME imports have not always been accompanied by robust traceability, regulatory classification, or sustainability criteria. This suggests that policy uncertainty also originates at the international level, not solely at the national level [51]. Such dynamics further constrain market, commercialization, and cost/risk readiness.

SPE-G noted that national development plans (RPJPN and its medium-term components) target a reduction in untreated waste to 10% but do not prescribe specific treatment technologies. Compared with OFMSW, as described in a later section, ADT for POME faces lower barriers due to relatively stable feedstock availability and established operational capacity. Social pressure from surrounding communities and regulatory oversight further incentivize POME treatment. However, SPE-G raised concerns regarding data consistency and reporting quality, underscoring the need for stronger evaluation and reporting mechanisms.

Overall, stakeholders converged on the conclusion that ADT for POME in Indonesia has reached a high level of technological maturity and social acceptance. Consistent with the methodological framework established in Section 3, the primary challenge facing POME-based ADT is therefore not technological readiness itself but the optimization of governance arrangements and policy alignment.

4.2. Technology Readiness of Anaerobic Digestion for OFMSW

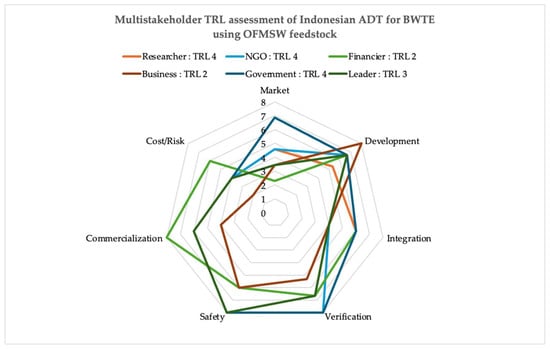

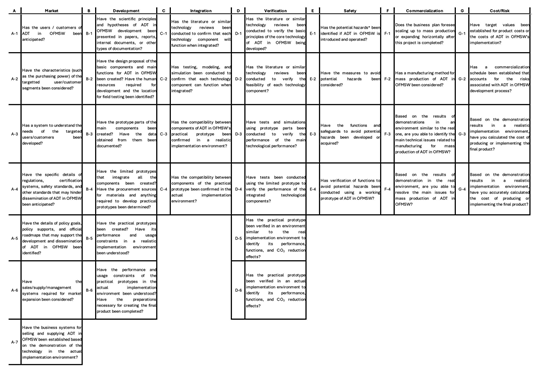

Figure 6 presents the TRL assessment of ADT applied to OFMSW in Indonesia, drawing on the same J-TRA framework and response-code approach introduced in Section 3. Similarly to the POME case, the assessment reflects perspectives from six stakeholder groups (SOM-R, SOM-N, SOM-F, SOM-B, SOM-G, and SOM-L). Compared with the POME case discussed in Section 4.1, Figure 6 shows greater divergence across readiness parameters, indicating higher uncertainty and weaker systemic alignment for OFMSW-based ADT.

Figure 6.

Multistakeholder TRL assessment of Indonesian ADT for BWTE using OFMSW feedstock.

Unlike POME, normalized TRL scores for OFMSW vary more widely across stakeholders. Figure 6 shows that, for the market parameter alone, stakeholders are divided across TRL 2, 3, 5, and 7. Only for the integration parameter are respondents evenly split between TRL 4 and TRL 6. Most respondents assessed the development parameter at TRL 7, with one indicating TRL 5 and another TRL 8. Similarly, for the commercialization parameter, most respondents reported TRL 6, with one reporting TRL 4 and another TRL 8. For the verification parameter, half of the respondents indicated TRL 7, while the remainder reported TRL 5 or TRL 8. The safety parameter also shows divergence between TRL 6 and TRL 8. Finally, for the cost/risk parameter, four respondents reported TRL 4, one reported TRL 2, and one reported TRL 6.

4.2.1. Technical–Operational Readiness of ADT for OFMSW

Although Tiong et al. [11] regard ADT for OFMSW as technically mature, stakeholders emphasized the distinction between engineering maturity and system readiness. SOM-R highlighted that OFMSW exhibits high variability in composition, moisture content, and contamination, resulting in less stable digestion performance. These feedstock characteristics require different operational and institutional arrangements, contributing to lower readiness in the integration, verification, and commercialization parameters.

SOM-R viewed ADT as readily deployable and demonstrated its feasibility in small-scale, closed-loop household systems, indicating medium-to-high readiness in the development parameter, a view shared by other respondents. However, replication remains difficult due to governance and market barriers. Used cooking oil (UCO) was cited as an often-overlooked OFMSW stream, despite its consistent generation. Similarly to raw POME, UCO is often diverted for export as a raw material due to external demand. Without adequate control, challenges related to pretreatment efficiency, air pollution, toxic residues, and overall environmental impacts and costs may persist [52]. These impacts are best assessed through comprehensive life-cycle assessment (LCA) and life-cycle costing (LCC) approaches [7,9].

Innovation therefore focuses less on digestion processes and more on downstream applications, including digestate valorization as liquid organic fertilizer, as well as biogas storage and distribution within the wider community. Verification of emissions reductions from such decentralized systems remains limited, as most operate outside formal monitoring frameworks. According to SPE-R, these unverified emissions reductions represent a lost opportunity when carbon crediting mechanisms are considered. Although private sector and government financing instruments exist, including one implementation case in the Ciliwung River area, commercialization challenges persist due to limited market access and sales capacity.

4.2.2. Systemic Enablers Affecting ADT Readiness for OFMSW

Replication at the community level was described as technically straightforward but socially fragile. SOM-R and SOM-N noted that declining waste separation practices undermine feedstock quality and system stability, constraining the integration and verification parameters. SOM-G and SOM-N further stated that emissions accounting requires nationally standardized food waste data and treatment methodologies, with consistent implementation at the local level. Poor waste segregation leads to higher contamination, resulting in more severe system instability and further constraining integration and verification readiness.

SOM-N emphasized that socio-economic status does not reliably predict improved waste behavior, as households often externalize responsibility once collection fees are paid. This phenomenon is commonly described as a not-in-my-backyard (NIMBY) attitude. Such dynamics weaken integration and market readiness.

From a financial perspective, SOM-F described ADT as economically risky due to limited public budgets, weak waste retribution mechanisms, and non-prescriptive policy frameworks. The Ministry of Public Works, through Regulation No 3/2013, was also noted as explicitly promoting refuse-derived fuel (RDF) as a “silver bullet” for managing combustible municipal solid waste through co-firing in coal- and steam-based electricity generation. However, this approach is problematic due to inconsistent waste sorting, substandard feedstock quality, and cost concerns, which collectively result in lower fuel effectiveness and stability [53,54]. Limonti et al. showed that the inclusion of partially stabilized substrates leads to a measurable methane yield reduction compared with segregated OFMSW [55]. The same study also highlighted that, even with reduced methane yields under co-digestion, higher profitability may still be achieved due to treatment revenues and incentive structures [55].

SOM-F viewed RDF as an easier alternative given its mixed, high-moisture waste characteristics, but one that leads to low energy conversion efficiency. ADT is perceived as more difficult to implement than RDF and is therefore often deprioritized. SOM-F further noted that ADT is perceived as operationally complex and risky at the community scale, particularly where technical capacity and safety oversight are limited. Similar observations were reported by Aromolaran et al. [56,57]. Unlike ADT for POME, which is typically located at remote palm oil mills, ADT for OFMSW is often located close to residential areas for accessibility reasons, thereby posing higher safety risks. This aligns with findings by Franchitti et al., who reported that mesophilic ADT achieves only a limited reduction in antibiotic-resistant genes [57]. Such limitations imply the need for enhanced monitoring and post-treatment to mitigate health risks [57], translating into lower readiness across market, commercialization, safety, and cost/risk parameters.

Budget constraints further reinforce these perceptions. SOM-F noted that only approximately 1.5% of local government budgets is allocated to waste management, with an even smaller share directed toward ADT. Although OFMSW-based ADT requires significantly lower capital investment (IDR 3–5 billion, due to simpler pipe materials) than POME-based systems, community-level waste retribution contributes only around 2%, undermining adoption. As a result, SOM-F assessed the cost/risk readiness of OFMSW-based ADT as remaining at a pilot-stage level.

Business stakeholders expressed similar concerns. SOM-B argued that Indonesia’s primary constraint lies in weak socio-institutional innovation. Poor enforcement, fragmented governance, and limited financing undermine incentives for waste containment, thereby weakening integration and verification readiness. In the absence of sustained government support, ADT projects face financial risks that communities are ill-equipped to absorb. SOM-B emphasized that progress requires low-cost ADT models that preserve economic viability while allowing room for social experimentation. Many respondents also agreed that insufficient incentives and weak implementation of the polluter pays principle (PPP) further constrain adoption.

According to both SOM-B and SOM-G, one potential pathway is to scale up local OFMSW treatment practices through more industrialized ADT systems. This approach remains limited for OFMSW but is evident in the POME case, as also noted by SPE-F. SOM-G repeatedly stressed the importance of at-source waste separation, while acknowledging that this approach is slow and likely feasible only in small communities. Only through improved separation can verification and integration readiness be substantially enhanced. SOM-G also highlighted the Free Nutritious Lunch (Makan Bergizi Gratis/MBG) program for school children, which is expected to generate approximately 100–200 grams of food waste per person per day. With millions of children in the country, this program is likely to add further pressure to OFMSW management systems.

SOM-L emphasized governance strategies most strongly. SOM-L cautioned against fragmented, context-specific OFMSW technologies at the local level, advocating instead for a nationally coordinated system that balances top-down policy direction with local adaptability. Drawing parallels with Indonesia’s electric vehicle adoption, SOM-L argued that while targeted municipal leadership can accelerate learning, sustained impact requires broader cultural change in household waste behavior.

Overall, compared with POME, OFMSW-based ADT exhibits lower readiness across market, commercialization, cost/risk, verification, and integration parameters due to combined behavioral, institutional, and economic constraints.

5. Discussion and Analysis

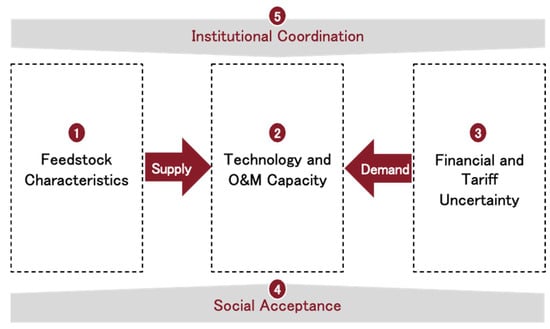

This section synthesizes the findings from Section 4 by examining how the observed TRL outcomes for ADT applied to POME and OFMSW are shaped by interacting systemic forces. Using the five-force framework illustrated in Figure 7 and informed by the discussion in Section 2, this analysis moves beyond technology-specific assessments to explain why readiness outcomes differ between the two feedstocks, despite reliance on the same core technology.

Figure 7.

Interaction of five systemic forces shaping BWTE readiness [52].

Figure 7 conceptualizes biomass waste-to-energy (BWTE) deployment as an interconnected system influenced by feedstock characteristics, technology and operations and maintenance (O&M) capacity, financial and market conditions, social acceptance, and institutional coordination. The stakeholder-based J-TRA results demonstrate that these forces do not operate independently; rather, weaknesses in one domain can propagate through the system and constrain overall readiness. This interaction explains the divergence between the relatively high readiness of ADT for POME and the lower, more fragmented readiness observed for OFMSW.

5.1. Synthesis

5.1.1. Feedstock Characteristics

At the foundation of the system lies feedstock certainty. Stakeholders consistently emphasized that moisture content, contamination levels, seasonality, and reliability of supply directly affect digestion stability and biogas yield. A bench-scale optimization study by Yap et al. indicated that electrochemical pretreatment can triple methane yields from POME to 11.47 mL CH4/gram of chemical oxygen demand (COD) [14]. These methane production benefits outweigh the required pretreatment energy of 2505 kJ/kg of total solids (TS) [14]. POME feedstock is centrally generated, relatively homogeneous, and continuously available at mill sites, supporting stable operation and higher integration and commercialization readiness, alongside most other parameters.

In contrast, OFMSW is decentralized and highly variable, with quality strongly dependent on household behavior and collection practices. This variability introduces uncertainty into system design and operation, which in turn constrains technological performance and investment confidence, resulting in low TRL outcomes across nearly all parameters.

5.1.2. Technology and O&M Capacity

Feedstock conditions directly influence technology design and O&M capacity, forming the second force illustrated in Figure 7. Stakeholders noted that Indonesia’s decentralized waste landscape amplifies the importance of adaptive system design, skilled operators, and reliable O&M support services. However, this does not imply that operators alone are responsible for the limited maturity of OFMSW-based ADT. Rather, the challenge is systemic and extends beyond individual operational capacity [56]. For POME-based ADT, co-location at palm oil mills enables tighter control over process conditions and facilitates operator learning, contributing to higher perceived safety and integration readiness.

For OFMSW, however, weaknesses in waste segregation and preprocessing increase operational complexity and raise the risk of process instability, even where digestion technology itself is technically mature. Experimental studies demonstrate that ADT for OFMSW is sensitive to elevated organic loading rates (OLRs) and substrate variability [56]. These conditions lead to volatile fatty acid accumulation and reduced methane yields, even under controlled environments [56]. Such O&M challenges help explain why OFMSW-based systems often remain at pilot or niche scales.

5.1.3. Financial and Market Conditions

On the demand side, financial viability and market conditions emerged as critical determinants of readiness. Across stakeholder groups, uncertainty surrounding tariffs, power-purchase agreements, and long-term revenue streams was identified as a major barrier to investment. In the POME context, internal utilization of biogas and electricity provides a relatively clear economic rationale, partially insulating projects from external market volatility. This is consistent with Hayyat et al.’s (2024) finding that persistent emissions from POME are increasingly linked to institutional and market misalignment rather than technological limitations [15].

In contrast, OFMSW-based projects are more dependent on public budgets, tipping fees, or externally determined tariffs, making them particularly sensitive to policy inconsistency and fiscal constraints. As a result, market and commercialization readiness for OFMSW remains comparatively low.

5.1.4. Social Acceptance

Surrounding these core supply- and demand-side forces are two cross-cutting enablers: social acceptance and institutional coordination. Social acceptance was repeatedly highlighted as a decisive factor, particularly for OFMSW-based ADT. Public perceptions of risk, trust in government, transparency, and NIMBY concerns shape both community willingness to host facilities and everyday behaviors such as at-source waste separation [38,52,58]. Poor waste segregation directly degrades feedstock quality, thereby increasing preprocessing costs and reducing biogas yields. In this sense, social acceptance affects not only project legitimacy but also the physical performance of the technology.

For POME, social acceptance operates differently. ADT facilities are typically located within industrial estates, reducing direct community opposition [59]. However, acceptance still influences corporate decision-making through reputational risk, regulatory scrutiny, and relationships with surrounding communities. Stakeholders emphasized that incidents involving untreated POME discharge can rapidly undermine a company’s social license to operate, reinforcing the importance of reliable ADT performance [36,43].

5.1.5. Institutional Coordination

Institutional coordination constitutes the fifth force shaping BWTE readiness. Stakeholders pointed to fragmented governance, overlapping mandates, and weak inter-agency coordination as persistent constraints. The absence of prescriptive policy instruments for ADT deployment means that technology choices are often shaped by short-term considerations rather than system-wide optimization. Current governance arrangements rely heavily on private developers and ad hoc partnerships, with limited mechanisms for structured public participation or consistent waste retribution incentives. These institutional gaps disproportionately affect OFMSW-based systems, which require coordinated action across households, municipalities, operators, and regulators.

5.1.6. Synthesis Across Forces

Taken together, the analysis indicates that differences in TRL outcomes between ADT applied to POME and OFMSW are not primarily driven by technological limitations. Instead, they reflect the interaction of feedstock characteristics with O&M capacity, market conditions, social behavior, and governance structures. Consistent with prior studies, technical solutions alone are insufficient without aligned incentives, behavioral engagement, and institutional support.

From a broader sustainability perspective, stakeholders emphasized that BWTE technologies should be evaluated not only by the problems they solve but also by the value they create across economic, environmental, and social dimensions. Resource valorization through cross-chain approaches—such as integrating ADT with composting, fermentation, or other bio-conversion pathways—offers opportunities to enhance overall system performance [36,37,38]. Hybrid configurations can improve resource recovery, reduce costs, and increase resilience, provided they are supported by appropriate regulatory and market frameworks. Giordano et al. (2024) also demonstrated that ADT combined with valorization in hybrid approaches features prominently in circular economy-related debates and literature [35].

Ultimately, the findings underline the importance of transitioning from a linear to a circular economy model in Indonesia’s waste and energy sectors [7,37,52]. At-source waste segregation emerges as a foundational requirement for improving both environmental outcomes and energy recovery rates, particularly for OFMSW [36,38]. When combined with economic incentives, capacity building, and regulatory strengthening, ADT-based BWTE systems have the potential to move beyond pilot applications and contribute meaningfully to Indonesia’s long-term waste management and energy security goals.

5.2. Implications

5.2.1. Policy Implications

The results indicate that Indonesia’s BWTE policy should be explicitly differentiated by feedstock type rather than framed as a single technology deployment agenda. For POME-based ADT, which has already reached relatively high readiness, policymakers should shift from generic promotion toward strengthening enforcement, performance monitoring, and market integration. This includes tightening compliance checks under existing mandatory regulations and improving the quality of emissions reporting. Additionally, grid access and tariff mechanisms should avoid penalizing biogas utilization relative to fossil energy. Linking ADT more explicitly to national methane mitigation and circular economy targets would also strengthen incentives for optimization rather than minimal compliance.

For OFMSW-based ADT, the priority should not be rapid technological scaling but the establishment of systematic enabling conditions. Policymakers should invest in standardized waste data systems, enforceable waste-segregation-at-source requirements, behavioral change programs, and clearer coordination across waste, energy, and local governance institutions. Without these foundations, financial incentives and pilot projects are unlikely to translate into sustained system maturity. ADT should therefore be embedded within broader waste management and service provision strategies rather than treated primarily as an energy technology. This sequencing is essential to avoid technology–policy mismatches and inefficient allocation of public resources.

5.2.2. Managerial Implications

For business leaders and project developers, the findings highlight the importance of aligning ADT investment strategies with feedstock-specific readiness conditions. In POME-based systems, stable feedstock supply and higher TRLs justify moving beyond feasibility assessment toward operational excellence. Managers should prioritize process optimization, safety management, emissions monitoring, and long-term risk mitigation. These factors increasingly influence regulatory exposure, reputational risk, and financial performance. ADT should be treated as a strategic asset for compliance, cost control, and corporate sustainability positioning, rather than as a technical add-on.

In OFMSW contexts, managers should adopt a more cautious, system-oriented approach. High technological maturity does not imply low operational or financial risk, given the strong dependence on social behavior, feedstock quality, and institutional coordination. Successful projects are therefore more likely to scale gradually, integrate with existing waste services, and invest in organizational capacity and stakeholder engagement alongside physical infrastructure. Managers should frame ADT less as a stand-alone energy business and more as part of an integrated environmental service offering. Its value proposition centers on reliability, risk reduction, and public service outcomes rather than short-term energy revenues.

6. Conclusions

This study evaluated the readiness of ADT for BWTE development in Indonesia using two high-moisture feedstocks—POME and OFMSW. It integrated a literature review, multistakeholder interviews, and a structured J-TRA-based assessment. This study demonstrates that technological maturity alone does not determine deployment outcomes. Instead, readiness is shaped by the interaction between technology performance and broader system conditions, including feedstock characteristics, social behavior, financial incentives, and institutional coordination.

The comparative analysis reveals distinct readiness trajectories. Indonesia’s waste profile, decentralized waste governance, and centralized electricity procurement system produce uneven readiness outcomes across feedstocks. POME-based ADT benefits from consistent, homogeneous feedstock supply, established industrial operating practices, and alignment with corporate decarbonization strategies. It has already reached relatively high maturity at TRL 6–8. Remaining barriers are primarily economic and institutional, including capital requirements, tariff structures, and competing incentives such as export demand for untreated POME. In contrast, OFMSW-based ADT is constrained by feedstock contamination, low waste segregation rates, limited O&M capacity, residential safety concerns, weak commercialization concepts, limited municipal budgets, and fragmented governance. It has only reached lower maturity at TRL 2–4. The application of J-TRA proved effective in capturing these contextual differences and in revealing how identical technologies perform differently when embedded within industrial versus community-managed waste systems. These findings highlight that ADT is not a context-neutral or “plug-and-play” solution across waste systems.

Across both cases, ADT readiness is shaped by five interrelated forces: feedstock characteristics, O&M capacity, financial certainty, social acceptance, and institutional coordination. For OFMSW, social behavior, starting with waste segregation, emerges as the dominant constraint, as it directly influences feedstock quality, operational efficiency, and investment viability. For POME, institutional and financial alignment—rather than public behavior—play a more decisive role in whether technically mature systems are optimized and scaled.

Overall, the results point to a dual maturity pathway. POME-based ADT is technically and operationally ready for further expansion, subject to improved policy alignment and market integration. OFMSW-based ADT requires more fundamental interventions in governance, behavioral norms, municipal capacity, and financing before industrial or large-scale deployment is feasible. Advancing OFMSW applications therefore depends less on improving digestion technology and more on strengthening waste management systems, improving capacity and behaviors, enhancing retribution and incentive schemes, and establishing a standardized national data infrastructure.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. The analysis focused on ADT and does not fully compare alternative BWTE pathways. A limited sample size and geographic generalizability, alongside the absence of post-interview validation, introduce potential interpretive bias. In addition, TRL-based assessment cannot fully capture dynamic policy, cultural, or market changes over time.

Future research could examine hybrid and complementary pathways, such as integrating ADT with composting, biohydrogen production, insect bioconversion, or thermochemical processes. Expanding LCA and LCC analyses could further quantify environmental and economic performance. Lastly, adopting longitudinal and regionally expanded research designs could improve our understanding of how institutional learning and behavioral change influence readiness. Such efforts can support the co-evolution of technical, social, and institutional systems, enabling ADT to contribute more effectively to methane mitigation, resource recovery, and the advancement of Indonesia’s circular bioeconomy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.A.N. and A.H.P.; methodology, A.H.P. and N.A.N.; software, N.A.N. and A.H.P.; validation, N.A.N. and A.H.P.; formal analysis, N.A.N.; investigation, N.A.N. and A.H.P.; resources, N.A.N.; data curation, N.A.N. and A.H.P.; writing—original draft preparation, N.A.N., A.H.P. and M.R.; writing—review and editing, N.A.N., A.H.P. and M.R.; visualization, N.A.N.; supervision, A.H.P. and H.O.; project administration, N.A.N. and A.H.P.; funding acquisition, A.H.P. and H.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Japan Science and Technology Agency: Strategic International Collaborative Research Program (SICORP) e-Asia Joint Research Program (JRP) Alternative Energy Field (grant number JPMJSC24E1), alongside Research and Innovation for Advanced Indonesia (RIIM), Indonesia National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), and Indonesian Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP) (grant number 69/IV/KS/04/2025 and 1867/UN1/DITLIT/Dit-Lit/PT.01.03/2025).

Data Availability Statement

The anonymized data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to project restrictions and confidentiality agreements.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used GenAI to assist in identifying keywords during the literature review. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The research partial funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADT | Anaerobic Digestion Technology |

| APBD | Provincial Income-Expenditure Budget/Anggaran Pendapatan Belanja Daerah |

| BAU | Business-as-Usual |

| BSF | Black Soldier Fly |

| BUPP | Private Developer and Management Company/Badan Usaha Pengelola dan Pengembang |

| BWTE | Biomass Waste-to-Energy |

| CAPEX | Capital Expenditure |

| CE | Circular Economy |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| COD | Chemical Oxygen Demand |

| DI | Danantara Indonesia |

| EFB | Empty Fruit Bunch |

| FIT | Feed-in Tariff |

| GOI | Government of Indonesia |

| GW | Gigawatt |

| GWP | Global Warming Potential |

| IRR | Internal Rate of Return |

| JPY | Japanese Yen |

| J-TRA | Japanese Technology Readiness Assessment |

| KESDM | Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources/Kementerian Energi dan Sumber Daya Mineral |

| KLH | Ministry of Environment/Kementerian Lingkungan Hidup |

| KWh | Kilowatt Hours |

| LCA | Life-Cycle Assessment |

| LCC | Life-Cycle Costing |

| LCOE | Levelized Cost of Electricity |

| LFGTE | Landfill Gas-to-Energy |

| LPG | Liquefied Petroleum Gas |

| MBG MSW | Free Nutritious Lunch/Makan Bergizi Gratis Municipal Solid Waste |

| NIMBY | Not-in-my-backyard |

| OFMSW | Organic Fraction of Municipal Solid Waste |

| OLR | Organic loading rates |

| PGN PKS | State Gas Company/Perusahaan Gas Negara Palm Kernel Shells |

| PLN | State Electricity Company/Perusahaan Listrik Negara |

| PLTSa | Waste Energy Generator Facility/Pembangkit Listrik Tenaga Sampah |

| POME PROPER | Palm Oil Mill Effluent Public Disclosure Program for Environmental Compliance/Program Penilaian Peringkat Kinerja Perusahaan dalam Pengelolaan Lingkungan Hidup |

| RDF | Refuse-Derived Fuel |

| RPJPN | Long-Term National Development Plan/Rencana Pembangunan Jangka Panjang Nasional |

| SEE | Social–Environmental–Economic |

| SIPSN | National Waste Management Information System/Sistem Informasi Pengelolaan Sampah Nasional |

| SSF | Solid-State Fermentation |

| TPA | Final Disposal Spot/Tempat Pembuangan Akhir |

| TRL | Technology Readiness Level |

| TS | Total solids |

| UCO | Used cooking oil |

| VS | Volatile solids |

| WTE | Waste-to-Energy |

| 3R | Reduce, Reuse, Recycle |

Appendix A

J-TRA Interview Questions for Multistakeholder ADT TRL Using POME Feedstock

Appendix B

Data Points for Multistakeholder Indonesian ADT TRL Using POME Feedstock

Appendix C

J-TRA Interview Questions for Multistakeholder ADT TRL Using OFMSW Feedstock

Appendix D

Data Points for Multistakeholder Indonesian ADT TRL Using OFMSW Feedstock

References

- Karnavian, M.T. Keynote Speaker: Koordinasi Nasional dan Peran Pemerintah dalam Pengelolaan Sampah. PowerPoint Presentation, Kementerian Dalam Negeri Republik Indonesia, Jakarta, September 2025. Available online: https://kemenlh.go.id/news/detail/wamen-lh-saatnya-indonesia-perang-lawan-sampah-lewat-teknologi-waste-to-energy (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Yuliot. Konversi Sampah Menuju Kemandirian Energi. PowerPoint Presentation, Kementerian Energi dan Sumber Daya Mineral Republik Indonesia, Jakarta, September 2025. Available online: https://kemenlh.go.id/news/detail/wamen-lh-saatnya-indonesia-perang-lawan-sampah-lewat-teknologi-waste-to-energy (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Aprilianto, H.C.; Rau, H. A Multi-Objective Optimization Approach for Generating Energy from Palm Oil Wastes. Energies 2025, 18, 2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mello, B.S.; Pozzi, A.; Rodrigues, B.C.G.; Costa, M.A.M.; Sarti, A. Anaerobic digestion of crude glycerol from biodiesel production for biogas generation: Process optimization and pilot scale operation. Environ. Res. 2023, 244, 117938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomczak, W.; Żak, S.; Kujawska, A.; Szwast, M. The Use of Crude Glycerol as a Co-Substrate for Anaerobic Digestion. Molecules 2025, 30, 3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratiwi, N.A.; Desmawati, N.N.; Jamaluddin, A.F.; Fitri, A.; Limbong, A.M. Biomass Energy Potential from Agricultural Waste in Indonesia: A Review of National Statistical Data. J. Nat. Plants Anim. Stud. 2025, 1, 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Harb, T.B.; Chow, F. An overview of beach-cast seaweeds: Potential and opportunities for the valorization of underused waste biomass. Algal Res. 2022, 62, 102643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandyaswargo, A.H.; Pang, D.; Ihara, I.; Onoda, H. Japan-Supported Biomass Energy Projects Technology Readiness and Distribution in the Emerging Southeast Asian Countries: Exercising the J-TRA Methodology and GIS. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Dev. 2020, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandyaswargo, A.H.; Onoda, H.; Nagata, K. Energy recovery potential and life cycle impact assessment of municipal solid waste management technologies in Asian countries using ELP model. Int. J. Energy Environ. Eng. 2012, 3, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budiman, I. The complexity of barriers to biogas digester dissemination in Indonesia: Challenges for agriculture waste management. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2021, 23, 1918–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiong, J.S.M.; Chan, Y.J.; Lim, J.W.; Mohamad, M.; Ho, C.-D.; Rahmah, A.U.; Kiatkittipong, W.; Sriseubsai, W.; Kumakiri, I. Simulation and Optimization of Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Food Waste with Palm Oil Mill Effluent for Biogas Production. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Lower, L.; Berrio, V.R.; Cunniffe, J.; Kolar, P.; Cheng, J.; Sagues, W.J. Impacts of Municipal and Industrial Organic Waste Components on the Kinetics and Potentials of Biomethane Production via Anaerobic Digestion. Waste Biomass-Valorization 2025, 16, 5019–5035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaya-Reza, O.; Altamirano-Corona, M.F.; Basurto-García, G.; Patricio-Fabián, H.; García-González, S.A.; Martinez-Hernandez, E.; Durán-Moreno, A. Wet anaerobic digestion of organic fraction of municipal solid waste: Experience with long-term pilot plant operation and industrial scale-up. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 47, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yap, B.J.T.; Heng, G.C.; Ng, C.A.; Bashir, M.J.K.; Lock, S.S.M. Enhancement of Electrochemical–Anaerobic Digested Palm Oil Mill Effluent Waste Activated Sludge in Solids Minimization and Biogas Production: Bench–Scale Verification. Processes 2023, 11, 1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayyat, U.; Khan, M.U.; Sultan, M.; Zahid, U.; Bhat, S.A.; Muzamil, M. A Review on Dry Anaerobic Digestion: Existing Technologies, Performance Factors, Challenges, and Recommendations. Methane 2024, 3, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Chowdhury, S.; Techato, K. Waste to Energy in Developing Countries—A Rapid Review: Opportunities, Challenges, and Policies in Selected Countries of Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia towards Sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, Z.J.; Bashir, M.J.; Ng, C.A.; Sethupathi, S.; Lim, J.W.; Show, P.L. Sustainable Waste-to-Energy Development in Malaysia: Appraisal of Environmental, Financial, and Public Issues Related with Energy Recovery from Municipal Solid Waste. Processes 2019, 7, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Huang, G.; Xu, Y.; Gong, Q. Waste-to-Energy in China: Key Challenges and Opportunities. Energies 2015, 8, 14182–14196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, A.; Haputta, P.; Silalertruksa, T.; Gheewala, S.H. A Framework for the Selection of Suitable Waste to Energy Technologies for a Sustainable Municipal Solid Waste Management System. Front. Sustain. 2021, 2, 681690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, H.; Alam, S.R.; Bin-Masud, R.; Prantika, T.R.; Pervez, N.; Islam, S.; Naddeo, V. A Review on Characteristics, Techniques, and Waste-to-Energy Aspects of Municipal Solid Waste Management: Bangladesh Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Li, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, B.; Zhang, G. A Review on the Management of Municipal Solid Waste Fly Ash in American. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2016, 31, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alao, M.A.; Popoola, O.M.; Ayodele, T.R. Waste-to-energy nexus: An overview of technologies and implementation for sustainable development. Clean. Energy Syst. 2022, 3, 100034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escamilla-García, P.E.; Camarillo-López, R.H.; Carrasco-Hernández, R.; Fernández-Rodríguez, E.; Legal-Hernández, J.M. Technical and economic analysis of energy generation from waste incineration in Mexico. Energy Strat. Rev. 2020, 31, 100542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agaton, C.B.; Guno, C.S.; Villanueva, R.O. Economic analysis of waste-to-energy investment in the Philippines: A real options approach. Appl. Energy 2020, 275, 115265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, A.; Daftari, T.; K, S.; Chandan, M.R.; Shaik, A.H.; Kiran, B.; Chakraborty, S. A comprehensive insight into Waste to Energy conversion strategies in India and its associated air pollution hazard. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 29, 103017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demaria, F.; Schindler, S. Contesting Urban Metabolism: Struggles Over Waste-to-Energy in Delhi, India. Antipode 2015, 48, 293–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, C.; Xia, B.; Liu, S.; Skitmore, M. Identification of Risk Factors Affecting PPP Waste-to-Energy Incineration Projects in China: A Multiple Case Study. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2018, 2018, 4983523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Fan, X.; Liang, J.; Liu, M.; Teng, Y.; Ma, Q.; Wang, Q.; Mu, R.; Zuo, J. Public Perception towards Waste-to-Energy as a Waste Management Strategy: A Case from Shandong, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2019, 16, 2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeleke, O.; Akinlabi, S.A.; Jen, T.-C.; Dunmade, I. Sustainable utilization of energy from waste: A review of potentials and challenges of Waste-to-energy in South Africa. Int. J. Green Energy 2021, 18, 1550–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Liu, Y.; Xia, B.; Jiang, X.; Skitmore, M. Overview of public-private partnerships in the waste-to-energy incineration industry in China: Status, opportunities, and challenges. Energy Strat. Rev. 2020, 32, 100584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaggs, R.L.; Coleman, A.M.; Seiple, T.E.; Milbrandt, A.R. Waste-to-Energy biofuel production potential for selected feedstocks in the conterminous United States. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 2640–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandyaswargo, A.H.; Gamaralalage, P.J.D.; Liu, C.; Knaus, M.; Onoda, H.; Mahichi, F.; Guo, Y. Challenges and an Implementation Framework for Sustainable Municipal Organic Waste Management Using Biogas Technology in Emerging Asian Countries. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghfiroh, M.F.N.; Pandyaswargo, A.H.; Onoda, H. Current Readiness Status of Electric Vehicles in Indonesia: Multistakeholder Perceptions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihara, I.; Pandyaswargo, A.H.; Onoda, H. Development and the Effectiveness of the J-TRA: A Methodology to Assess Energy Technology R&D Programs in Japan. In Proceedings of the EcoDePS 2018, Tokyo, Japan, 5 December 2018; pp. 109–117. Available online: https://researchmap.jp/?action=cv_download_main&upload_id=219915 (accessed on 5 April 2019).

- Giordano, V.; Castagnoli, A.; Pecorini, I.; Chiarello, F. Identifying technologies in circular economy paradigm through text mining on scientific literature. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0312709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vianna, L.M.C.; de Oliveira, L.; Mühl, D.D. Waste valorization in agribusiness value chains. Waste Manag. Bull. 2023, 1, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preethi, B.; Karmegam, N.; Manikandan, S.; Vickram, S.; Subbaiya, R.; Rajeshkumar, S.; Gomadurai, C.; Govarthanan, M. Nanotechnology-powered innovations for agricultural and food waste valorization: A critical appraisal in the context of circular economy implementation in developing nations. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 184, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldar, D.; Shabbirahmed, A.M.; Singhania, R.R.; Chen, C.-W.; Dong, C.-D.; Ponnusamy, V.K.; Patel, A.K. Understanding the management of household food waste and its engineering for sustainable valorization- A state-of-the-art review. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 358, 127390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onoda, H. Smart approaches to waste management for post-COVID-19 smart cities in Japan. IET Smart Cities 2020, 2, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demichelis, F.; Tommasi, T.; Deorsola, F.; Marchisio, D.; Mancini, G.; Fino, D. Life cycle assessment and life cycle costing of advanced anaerobic digestion of organic fraction municipal solid waste. Chemosphere 2022, 289, 133058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istrate, I.-R.; Iribarren, D.; Gálvez-Martos, J.-L.; Dufour, J. Review of life-cycle environmental consequences of waste-to-energy solutions on the municipal solid waste management system. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 157, 104778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamasb, T.; Nepal, R. Issues and options in waste management: A social cost–benefit analysis of waste-to-energy in the UK. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2010, 54, 1341–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Shafy, H.I.; Mansour, M.S.M. Solid waste issue: Sources, composition, disposal, recycling, and valorization. Egypt. J. Pet. 2018, 27, 1275–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.I.; Biswas, W.K. Sustainability Implications of the Incorporation of a Biogas Trapping System into a Conventional Crude Palm Oil Supply Chain. Sustainability 2019, 11, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasution, M.A.; Wulandari, A.; Ahamed, T.; Noguchi, R. Alternative POME Treatment Technology in the Implementation of Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO), and Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) Standards Using LCA and AHP Methods. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukisno; Arianto, W.; Sukisno, S. The impact of land application of palm oil mill effluents on some soil chemical characteristics in the District Karang Tinggi, Bengkulu Tengah Regency, Province of Bengkulu. BIO Web Conf. 2024, 123, 01023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskandar, M.J.; Baharum, A.; Anuar, F.H.; Othaman, R. Palm oil industry in South East Asia and the effluent treatment technology—A review. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2018, 9, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Peñaranda, R.; Gasparatos, A.; Stromberg, P.; Suwa, A.; Pandyaswargo, A.H.; de Oliveira, J.A.P. Sustainable production and consumption of palm oil in Indonesia: What can stakeholder perceptions offer to the debate? Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2015, 4, 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Listiningrum, P.; Idris, S.H.; Suhartini, S.; Vilandamargin, D.; Nurosidah, S. Regulating Biogas Power Plant From Palm Oil Mill Effluent (POME): A Challenge to Indonesia’s Just Energy Transition. Yust. J. Huk. 2022, 11, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodri, A.; Septriana, F.E. Biogas Power Generation from Palm Oil Mill Effluent (POME): Techno-Economic and Environmental Impact Evaluation. Energies 2022, 15, 7265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]