Abstract

The increasing integration of inverter-based resources in smart grid systems has deepened the necessity to understand the difference between grid-following and grid-forming inverters’ operational performance, particularly under abnormal conditions such as unintentional islanding events. This work provides a comparative assessment, showing that while grid-following inverters perform well under strong grids, their stability degrades under weak grids due to their dependence on the grid reference voltage. On the other hand, grid-forming inverters improve the system stability under weak grids, as they operate as an independent voltage source. However, the widespread misconception in academia and industry that grid-forming inverters are always good and grid-following inverters are generally bad is challenged by this work’s results. Despite the stability advantages of grid-forming inverters, they significantly increase the size of non-detected zones and extend the detection time of unintentional islanding events, with various cases failing to meet standards, while grid-following inverters offer quicker and more expectable responses. A Random Forest-based islanding detection scheme is proposed to address the protection difficulties allied with both inverter types. The findings prove that this model can reduce the size of the non-detected zone and the detection time, emphasizing the necessity of intelligent protection schemes in future microgrid applications and the significance of performance-based inverter selection.

1. Introduction

Over the past several years, the shift to renewable energy resources (RESs) has intensified globally due to the sharp rise in energy consumption and the pressing need to slow down climate change. As a result of this change, inverter-based resources (IBRs), such as PV and wind turbine systems, have significantly increased. Zero emissions can be attained by integrating IBRs into power grids. This integration provides effective and flexible power regulation since power electronic interfaces are completely programmable, increasing the operational flexibility and resilience of modern power grids [1,2,3].

However, additional difficulties with power system dynamics, control, stability, and protection have also been brought about by the widespread use of IBRs. The total system inertia reduces as traditional synchronous generators (SGs) are progressively moved, radically changing the grid’s behavior during disruptions and abnormal conditions. Islanding, a situation where a section of the grid continues to be powered by local sources even after being cut off from the main utility, is a significant worry brought on by this shift [4].

Islanding can be intentional, which is applied in case of grid operation for resilience development, or it can be unintentional, which may present serious threats to system safety and dependability. When unintentional islanding occurs, the voltage and frequency values greatly fluctuate from the rated values due to the absence of the utility grid reference, which leads to various dangerous consequences such as equipment damage, power quality degradation, and worker safety risks. Hence, guaranteeing safe grid functioning still depends on the prompt and precise identification of unintentional islanding [5].

Usually, most studies have concentrated on islanding detection for systems with grid-following (GFL) inverters. These inverters work as controlled current sources synchronized with the grid using a phase-locked loop (PLL), and when islanding happens, GFL inverters miss their voltage reference, causing their voltage and frequency to significantly deviate, making the detection much easier. Despite this, grid-forming inverters (GFM) have become a visible substitute as the integration of renewable energy resources rises. GFM inverters operate as voltage sources with their own voltage and frequency control schemes, which may enhance grid reliability and stability, particularly in islanded or weak networks [6,7,8].

In addition to the merits of GFM inverters, they raise additional difficulties, especially during unintentional islanding because the voltage and frequency regulation does not depend on the grid voltage reference, which leads to the power still being delivered to the local network without recognizing the grid disconnection. In this scenario, the non-detected zone can be larger because of maintaining the voltage and frequency level within the acceptable limits, which can delay the detection time significantly, causing various risky consequences for the network equipment and worker safety. Hence, unintentional islanding in the case of GFM inverters has emerged as a potential reliability problem in grid-connected systems in the future.

In this paper, the behaviors of grid-following and grid-forming sources under unintentional islanding conditions are investigated. A PV inverter and a synchronous generator present both the GFL and GFM sources, respectively. The comparative study highlights the dynamics of voltage and frequency after islanding, underlining how inverter performance impacts the system stability and the detectability of islanding conditions.

The main contributions of this work are briefly described below:

- An experimental-based study of unintentional islanding events in microgrid systems under different scenarios.

- A comparative assessment between grid-following (GFL) and grid-forming (GFM) inverters, stressing stability differences and response behavior during weak grid and unintentional islanding conditions.

- An examination of real restrictions of GFM inverters, including increased non-detection zones (NDZ) and prolonged detection times, challenging the misconception that GFM inverters control is universally superior and GFL inverters control is always bad.

- A performance-focused assessment, highlighting that inverter selection should be guided by operational response rather than control scheme’s philosophy only.

- A Random Forest-based technique for reliable and quick islanding detection using voltage, frequency, and ROCOF, accomplishing 99.29% accuracy and 0.2 s prediction time.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews weak grids and the description of unintentional islanding conditions. Section 3 discusses grid-following and grid-forming inverter behaviors. Section 4 depicts case study and corresponding investigation. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper and highlights the key findings.

2. Weak Grids and Unintentional Islanding Conditions

A weak grid is defined as a grid that has a restricted capability to guarantee a stable level of both voltage and current during any changeable circumstances in generation or load. Usually, the weakness or strength of grid-connected systems is determined by measuring the short-circuit ratio (SCR) at the point of interconnection. The short-circuit ratio (SCR) is calculated according to the following equation:

where is the nominal apparent power of the connected inverter and is the short circuit apparent power of the grid. When SCR has a high level specifically more than 20, the grid is considered strong, but if the SCR value is low, typically less than 10, then the grid is weak, and it will act like a high impedance source with reduced stiffness. can be calculated using the rated grid voltage and the grid impedance as presented below:

The length of the transmission line affects the impedance value. Hence the impedance is high in the case of a long transmission line, which will lead to a low SCR according to Equation (3). In such cases, the system is weak to overcome disturbances or impose strong reference voltage and frequency amounts. The presence of large integration of grid-following inverters minimizes the SCR level due to the lack of overcurrent capability, which is very important for grid-connected systems operation, and they are located far from the grid. On the other hand, grid-forming inverters are capable of providing a significant overcurrent for a reasonably long time. Therefore, to maintain a strong grid, more consideration has to be given to control scheme coordination, especially in the case of grid-following inverters such as solar or wind energy resources. The difference between grid-following and grid-forming inverter operation is especially crucial, as stability and power-sharing grow more reliant on inverter control modes. The inverter control modes are disrupted basically due to weak grids, demanding more adaptive and sophisticated mechanisms that can offer stable operation.

Various research has presented that weak grid conditions exhibit different difficulties, such as system stability degradation due to grid impedance changes [9], control oscillations and potential instability [10], and compromised voltage synchronization and power delivery [11]. To address these issues, researchers have proposed several mitigation approaches, including impedance reshaping [10], advanced phase-locked loop (PLL) designs for improved synchronization [12], and enhanced voltage feedback control strategies [13]. The literature consistently indicates across more than a decade of work that renewable energy sources integrated into weak grids benefit most from multi-loop, adaptive control methods that dynamically respond to changing grid conditions. Researchers have suggested a number of mitigation strategies to address these problems, such as improved voltage feedback control techniques [13], advanced phase-locked loop (PLL) designs for better synchronization [12], and impedance reshaping [10]. The literature continually shows that renewable energy sources integrated into weak grids derive the greatest benefit from multi-loop, adaptive control strategies that respond dynamically to altering grid events.

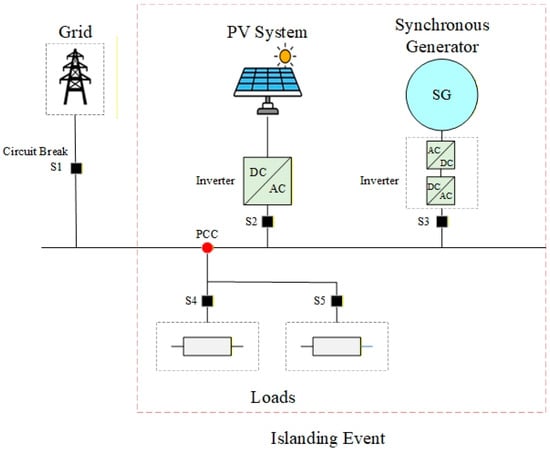

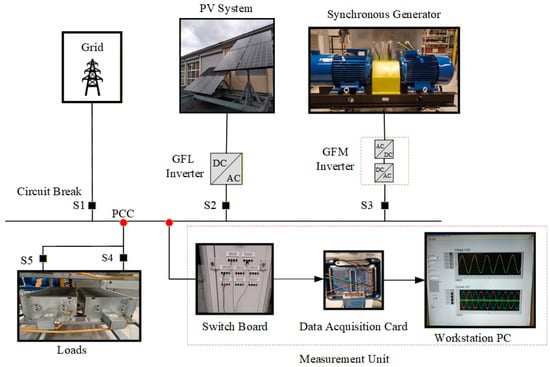

An islanding event is defined as a phenomenon when the main grid is disconnected from the inverter-based resources, while the connected inverters continue to deliver the power to the loads. As shown in Figure 1, the islanding occurs when circuit break S1 is open while the PV system and synchronous generator keep feeding the load with the required power via the point of common coupling (PCC). Islanding events are categorized as intentional and unintentional islanding events. Intentional islanding is a managed condition that is applied to allow some sections of the power grid to work individually during major faults, stopping blackouts and sustaining critical loads. But unintentional islanding happens when the connected inverters become isolated from the main grid due to disturbances or disconnections such as short circuits. Unintentional islanding has to be detected rapidly and accurately within less than 2 s according to IEEE 1547-2003 standards [14] this event can cause risky consequences to the network, such as losing the voltage and frequency control and endangering personnel and equipment, especially when the local generation and load are tightly matched.

Figure 1.

Unintentional islanding event.

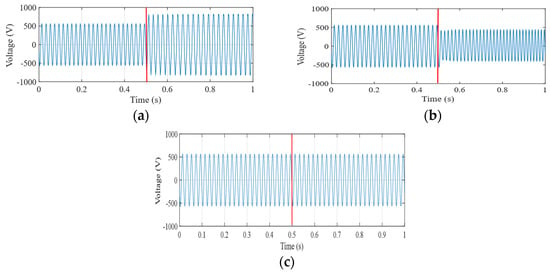

This closed match between the local generation and active and reactive power demand is known as the non-detected zone (NDZ). In this case, the voltage and frequency fluctuations are within the grid code limits, which complicates the detection of islanding, particularly if the method that is used depends on the network parameters, such as voltage and frequency deviations. Hence, NDZ size is an essential measure of performance for islanding detection methods, encouraging more studies intended to reduce NDZ size to improve the system’s safety and dependability. When the generation is bigger or smaller than the load power demand, the system will exhibit overvoltage or undervoltage, respectively, which requires less effort to detect the unintentional islanding event as presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Islanding event under different scenarios. (a) Islanding event when the inverter power is greater than load demand (over voltage). (b) Islanding event when the inverter power is smaller than load demand (under voltage). (c) Islanding event when the inverter power equals load demand (NDZ).

The islanding occurs exactly at 0.5 s, as highlighted by the red vertical, line under different scenarios, as presented in parts (a) and (b) of Figure 2, where there is no match between the inverter power and load demand. In these cases, it is very easy to detect the islanding due to the significant voltage level deviation, either over or under voltage. While in part (c) the inverter power matches the demand, resulting in a steady voltage level even after islanding. This condition is known as NDZ and makes it more complex to detect the islanding within the allowed time.

Apart from the balance between the generation power and load demand, another key factor affecting the NDZ size and detection time is the type of integrated inverters with the grid, whether it is a grid-following or grid-forming inverter system. The impact of these inverter types on non-detected zones under unintentional islanding is discussed below.

3. Grid-Following and Grid-Forming Inverters

The interaction between inverter-based resources and the main grid during normal and abnormal conditions depended on the control schemes that are used in these inverters. Such kinds of control schemes have totally different concepts when it comes to being used either with grid-following or grid-forming inverters. Grid-following inverters, which are considered controlled current sources, depend on the grid reference voltage, though grid-forming inverters, which are acting as voltage sources, have the capability to provide and regulate their own voltage and frequency. Hence, having a detailed insight into these functioning differences is very important to analyze the system behavior, stability, and reliability, especially in the case of a weak grid or any abnormal condition such as islanding events. Below, a detailed description of the principles and performance of each scheme is provided.

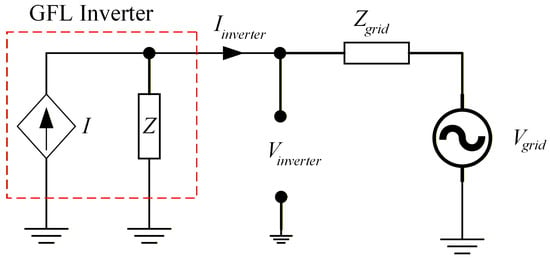

3.1. Grid-Following Inverters

GFL inverters are power electronic inverters that operate as controlled current sources, as shown in Figure 3. The output of GFL inverters totally depends on the grid reference voltage and it became synchronized with it by extracting the grid voltage phase angle using Phase-Locked Loops (PLLs) assisting them to inject current into the grid system. These inverters work by assuming a stable grid voltage when they are integrated with renewable energy resources. But, due to the increase in the implementation of inverter-based resources, the grid voltage stability decreases, possibly leading to a reduction in the inverters stability [15,16]. The major constraints of GFL inverters are relying on grid voltage for synchronization, their efficiency decline, especially in weak grids, and that they may face instability with high renewable energy integration [8].

Figure 3.

Representation of grid-following inverter.

GFL inverters mainly use PLL-based and PLL-less control methods to regulate and synchronize the power exchange with the grid. There are various control methods used with GFL inverters, such as PLL-based vector current control (VCC), which achieves synchronization with the grid frequency, but the stability may decline in weak grids and the voltage-modulated direct power control (VMDPC) method [17]. On the other hand, power-synchronized control without PLL provides more stability, especially in ultra-weak grids, by using the inverter output voltage for power control [18]. Furthermore, advanced current control methods combining lead compensation and active damping have been proposed to suppress filter resonance and improve grid stability [19]. In particular, it has been shown that the linear-parameter-varying power-synchronized control (LPV-PSC) is a viable technique for forthcoming grid-following inverters since it performs robustly and adaptively under a variety of grid scenarios [17].

The operation of GFL inverters under weak grids results in providing unstable voltage and frequency due to their dependency on PLL synchronization. Hence, GFL inverters offer less appropriate control architecture under weak grids, which negatively affects the system’s reliability and stability. However, the dynamic behavior of GFL inverters also has to be examined under unintentional islanding to find out their impact on the detection time accordingly.

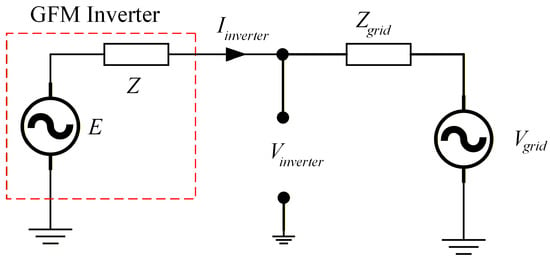

3.2. Grid-Forming Inverters

GFM inverters are advanced power electronics inverters that operate as a voltage source, as shown in Figure 4. The output of GFM inverters is totally independent from the grid reference voltage since these inverters are capable of regulating and forming the grid voltage and frequency individually by producing voltage phasors with inherent inertial behavior, unlike GFL inverters, which passively track the existing grid condition [20]. The major benefits of GFM are their capability to proactively control voltage and frequency, support power sharing among various generators, operate with or without rotating machines, balance between generation and demand, recover the voltage and frequency following power fluctuations, and efficiently operate under weak grids [21].

Figure 4.

Representation of grid-forming inverter.

Grid-forming inverters use sophisticated control techniques, namely droop control, virtual synchronous generator (VSG), and predictive algorithms, to independently set grid voltage and frequency. Many studies proposed different control methods, such as a combination of basic strategies such as droop control, and voltage and frequency regulation with enhanced methods such as adaptive and predictive control [22,23]. Four control methods, which are droop-based GFM inverters, virtual synchronous generator (VSG)-based GFM inverters, compensated generalized VSG (CGVSG)-based GFM inverters, and adaptive VSG (AVSG)-based GFM inverters, and remarkable differences in behavior under various grid scenarios were confirmed [22]. However, researchers suggest that the selection of control methods should be made according to grid characteristics and specific operational needs.

Under weak grid conditions, GFM inverters provide a capable solution for maintaining operational stability by using advanced control methods that can minimize the challenges of conventional grid integration. Different studies prove that GFM inverters are capable of addressing the system instability under weak grids using advanced control methods. GFM inverters offer vital grid support tasks and sustain the system stability, particularly under weak grids where GFL inverters fail to achieve the same [24,25]. However, this stable behavior of GFM inverters has to be analyzed under different abnormal conditions, specifically under unintentional islanding, to observe their influence on the detection time consequently.

The significant comparison findings between grid-forming and grid-following inverters under weak grid conditions are summarized as presented in Table 1. This table shows how different control techniques react when grid strength drops, providing for a clear comparison of the stability, dynamic responsiveness, and overall resilience of grid-forming and grid-following inverters.

Table 1.

Grid-following vs. grid-forming inverters performance under weak-grids.

The evaluated research largely confirms the feasibility of grid-forming (GFM) inverters for weak grid applications, particularly as renewable energy penetration rises. Yet, the majority of these conclusions are qualitative and stem mostly from simulation-based analysis. Additionally, due to the vast range of control mechanisms, system sizes, and grid strength definitions in the literature, the findings must be evaluated with caution, especially when considering other scenarios that were not covered by the aforementioned studies, such as unintentional islanding.

Many studies have compared the behavior of GFL and GFM inverters under intentional islanding modes and consistently show that GFM inverters improve voltage and frequency stability under such conditions. GFM inverters prevent under-frequency load shedding and provide improved transient response compared to GFL inverters under islanded distribution systems [32], and increased integration of GFM inverters can enhance inertia emulation and damping [20,33]. However, much less research has studied how GFL and GFM inverters perform under unintentional islanding scenarios. From a dynamic stability perspective, GFL inverters are highly sensitive to grid impedance due to PLL-based synchronization; as the short-circuit ratio (SCR) decreases, the phase margin of the current control loop degrades, often resulting in oscillations or loss of synchronization, particularly for SCR values below 10. In contrast, GFM inverters regulate voltage and frequency internally and can remain stable even under very weak grid conditions, with stable operation reported for SCR values below 3 in the literature and experimental studies. The post-islanding frequency and voltage deviations can be approximated by and , where and are active and reactive power mismatches, is equivalent inertia, is nominal frequency, and is a voltage–reactive power coefficient. Under small and , GFM inverters maintain voltage and frequency close to nominal, reducing observable islanding signatures and enlarging the non-detected zone (NDZ), whereas GFL inverters immediately lose the grid reference, producing faster and larger deviations, leading to smaller NDZ and shorter detection times. This enhanced robustness of GFM inverters directly impacts unintentional islanding detection. By maintaining near-nominal voltage and frequency following grid disconnection, GFM inverters suppress post-islanding transients, which enlarges the NDZ. Detecting unintentional islanding rapidly and precisely often requires reactive power or negative-sequence current injections. In contrast, GFL inverters exhibit rapid voltage and frequency deviations after islanding, resulting in smaller NDZ and more reliable islanding detection [34,35]. This analytical perspective aligns closely with the experimental results in Table 2, providing a quantitative explanation of why GFM inverters improve weak-grid stability but degrade islanding detectability, while GFL inverters behave inversely.

Table 2.

Investigated cases inspecting GFL and GFM inverters response under unintentional islanding event.

4. Case Study

In this work, a low-voltage AC microgrid-connected system was utilized for carrying out the experiment. The microgrid-connected system consists of a utility power supply, a 3.2 kW grid-following inverter (PV system), a 20 kW grid-forming inverter (synchronous generator system), a measurement unit, and 1.5 kW linear (resistive) and non-linear loads, as presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Experimental setup.

The voltage and frequency at PCC were measured before and after unintentional islanding events. In this experiment, various cases were considered to analyze the difference between GFL and GFM inverter behavior under unintentional islanding conditions, as presented in Table 2. In these scenarios, the GFL inverter is connected alone with the main utility power grid, the GFM inverter is connected with the main utility power grid, and both of the GFL and GFM inverters are connected to the system. The load also is linear, non-linear, and both linear and non-linear, respectively.

When the circuit breaker S1 opens, an unintentional islanding condition occurs. The voltage is measured using a National Instruments NI6040E card connected to a computer, and the voltage waveforms were displayed through LabVIEW 2025 Q3 software.

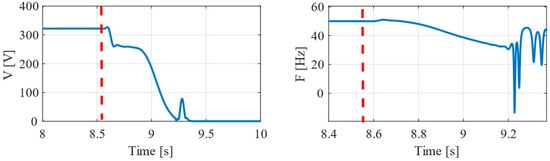

In the first case, the grid-following (GFL) inverter is connected alone to the grid with an output power of 1 kW. The voltage and frequency amplitudes are recorded before and after the unintentional islanding condition, as presented in Figure 6. When islanding occurs exactly at 8.54 s, highlighted by the dashed red line, the GFL inverter loses its voltage reference, causing a significant disturbance in the measured voltage. This makes the islanding condition easy to detect, and the GFL inverter shuts down after approximately 0.83 s, which is well within the required detection time based on standards (less than 2 s). Also, the non-detection zone (NDZ) in this case is null.

Figure 6.

Behavior of GFL inverter under unintentional islanding.

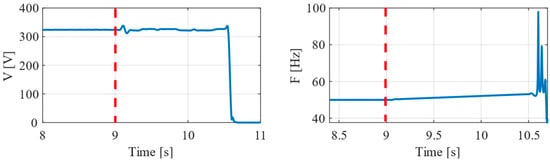

In the second case, the grid-forming (GFM) inverter is connected alone to the grid with an output power of 10 kW. The voltage and frequency amplitudes are recorded before and after the unintentional islanding condition, as presented in Figure 7. When islanding occurs exactly at 8.81 s, indicated by the dashed red line, the GFM inverter has stable behavior, causing no disturbance in the measured voltage. This makes the islanding condition hard to detect, and the GFM inverter shuts down after approximately 1.86 s, which is relatively long but still within the required detection time based on standards. Also, the non-detection zone (NDZ) in this case is large.

Figure 7.

Behavior of GFM inverter under unintentional islanding.

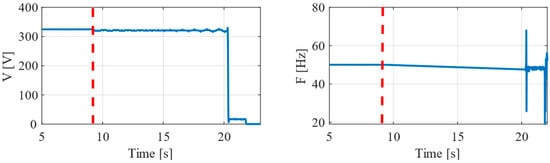

In the third case, both GFL and GFM inverters are connected to the grid system simultaneously, establishing a multi-inverter system. Similarly, both voltage and frequency amplitudes are captured pre- and post- the unintentional islanding event, as shown in Figure 8. In this case, as islanding starts at 9.15 s, highlighted by the dashed red line, the GFM inverter dominates the system and maintains significant stable voltage and frequency, which greatly enlarges the NDZ. As a result, the system needs 12.72 s to shut down, which is far longer than the standard acceptable detection time which leads to serious risky consequences if not appropriately and accurately addressed.

Figure 8.

Behavior of multiple inverters under unintentional islanding.

In order to observe the behavior of GFL and GFM inverters widely, more scenarios were examined for different combinations of inverters and loads under unintentional islanding conditions. Across linear, non-linear, and mixed load scenarios, the GFL inverter reliably shows fast detection times and null NDZ, which results in complete conformity with standards. GFM inverters, despite passing the required standards, have longer detection times and larger NDZ sizes, which is due to their dependency on the grid voltage and capability to form and regulate the voltage and frequency independently. When both GFL and GFM inverters are running at the same time, the system has a much larger NDZ and longer detection time, which does not meet the standards.

Table 2 highlights the stark differences between inverter types, showing that GFM inverters increase NDZ and detection time for all loads, with the greatest impact seen in mixed inverter setups.

When the GFL inverter operates individually, it reliably detects islanding for all load types, with a null NDZ and shutdown times of 0.39–0.84 s, well below the IEEE 1547 limit. Its fast response stems from loss of grid synchronization, which quickly triggers voltage and frequency deviations.

In contrast, the GFM inverter shows large NDZs for all load types. By actively regulating voltage and frequency after grid loss, it delays islanding detection, with shutdown times of 1.86 s (linear), 1.68 s (non-linear), and 1.66 s (mixed loads). While still within standards, these times are 2–4 times longer than the GFL inverter, reflecting the protection challenge of grid-forming control.

The most critical case occurs when GFL and GFM inverters operate together. Across all load types, this setup produces very large NDZs and shutdown times exceeding IEEE 1547 limits, which are 12.72 s (linear), 3.3 s (non-linear), and 5.06 s (mixed), indicating a clear failure of conventional islanding detection approaches.

The extended detection time is due to the GFM inverter’s dominant voltage-forming action, which stabilizes voltage and frequency at the PCC and masks islanding signatures. This effect is strongest under linear loads, where power balance is easily maintained, producing the longest NDZ.

Unintentional islanding severity is governed by the active and reactive power mismatch between generation and load, expressed as ΔP and ΔQ. The most critical condition occurs near zero mismatch, where |ΔP| ≈ 0 and |ΔQ| ≈ 0, defining the NDZ. Although load type influences detectability, with linear loads yielding the largest NDZs, inverter control strategy has a stronger impact. GFM inverters maintain voltage and frequency under small power mismatches, significantly enlarging the NDZ and increasing detection time by over 120% compared to GFL inverters, while mixed GFL–GFM configurations further extended detection time beyond standard limits, exceeding 12 s in some cases.

Additionally, for GFM inverters, droop control coefficients critically influence the balance between grid support and islanding detectability. Stiffer droop improves voltage and frequency regulation under unintentional islanding but enlarges the NDZ, while more aggressive settings enhance detection sensitivity at the cost of stability. This work used fixed industrial droop values, though adaptive tuning could optimize the balance between weak-grid stability and rapid islanding detection, representing a key direction for future work.

These results highlight the compromise between stability and protection. GFM inverters improve voltage and frequency stability, especially in weak grids, but reduce islanding detectability, whereas GFL inverters provide faster, more reliable detection despite low-SCR limitations, as presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Quantitative comparison of GFL and GFM inverters under weak grid and unintentional islanding conditions.

Table 3 quantitatively illustrates that GFM inverters provide superior weak-grid stability by keeping voltage and frequency close to nominal, even under low SCR conditions. At the same time, their strong regulation reduces the magnitude of post-islanding transients, resulting in larger non-detected zones (NDZ) and longer detection times, particularly in mixed-inverter configurations, while GFL inverters show faster deviations and more effective unintentional islanding detection.

Therefore, during the presence of GFM inverters in the grid, designers have to carefully consider the correct selection of islanding detection method that can detect the unintentional islanding accurately and rapidly. Islanding detection methods are classified into traditional and modern techniques. Modern techniques that depend on feature extraction, data training, and pattern recognition are the best solution for such abnormal conditions, especially when response time and NDZ criteria are considered [36,37].

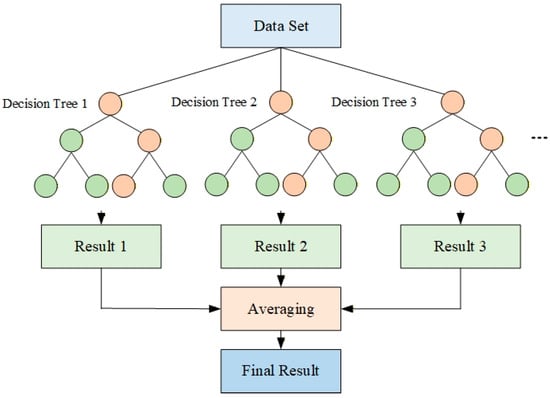

Accordingly, an islanding detection method based on the Random Forest (RF) approach is proposed and compared with the inverters used in our work. RF is a supervised machine learning method that builds various decision trees during the training process and harvests the classification mode and the prediction mean of each tree, as presented in Figure 9. RF has many significant advantages, such as the ability to decrease overfitting, built-in feature importance measurement, and high prediction accuracy [38,39].

Figure 9.

Random Forest structure.

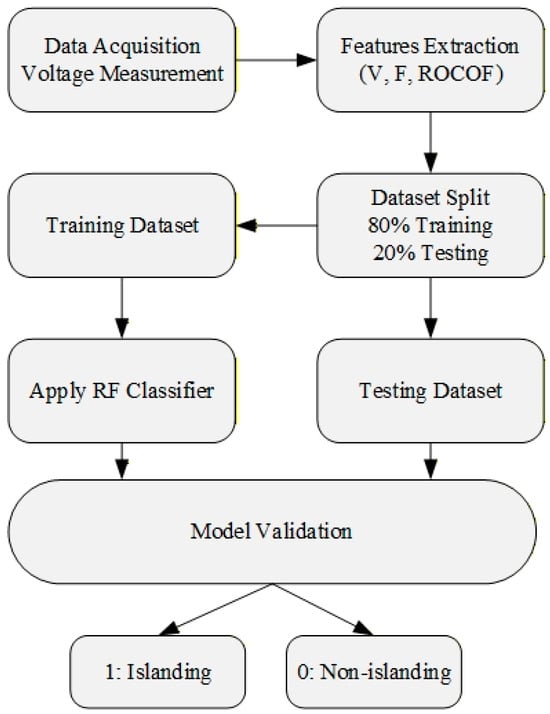

In this work, the RF model was designed to accomplish a binary classification of 0 or 1 for non-islanding and islanding, respectively, using three input features: voltage amplitude, voltage frequency, and rate of change in frequency (ROCOF). The dataset consists of 33,865 samples gathered from the experimental measurements and had been split utilizing an 80/20 hold-out technique applied with MATLAB’s cvpartition, providing 27,092 samples for training and 6773 samples for testing, as shown in Figure 10. The model was developed using the TreeBagger function with 100 decision trees. Every tree was trained using a bootstrap-resampled subset of the training data and grew to its greatest depth without trimming. Random feature selection was employed at each node to establish the appropriate split, hence improving ensemble diversity. Out-of-bag (OOB) prediction was enabled to offer an internal assessment of the model’s generalization error irrespective of the test data set. Training and prediction were subsequently performed on the different subgroups to create the final model utilized in assessment.

Figure 10.

Random Forest model flowchart.

The confusion matrix of the RF model validated its efficacy, with 4495 true positives, 2230 true negatives, 7 false positives, and 41 false negatives, as presented in Table 4. Also, this model displayed outstanding prediction performance throughout all measures, obtaining an accuracy of 99.29%, precision of 99.84%, recall of 99.10%, and an F1-score of 99.47%, demonstrating very trustworthy classification, as shown in Table 5. The model detects the unintentional islanding condition regardless of NDZ size in around 0.2 s, which is quicker than the islanding detection time of all inverters employed in our studies. These findings demonstrate the model’s resilience and appropriateness for accurate microgrid measurement classification based on voltage, frequency, and ROCOF characteristics.

Table 4.

RF model contingency table.

Table 5.

RF model performance metrics.

Also, this proposed model is suitable for real-time protection, as it uses low-frequency measurements already available in digital relays and microgrid controllers. The average prediction time of about 0.2 s complies with IEEE 1547 requirements and practical protection constraints. Owing to its low computational burden, the classifier can be efficiently implemented on embedded processors, digital signal processors (DSPs), or field-programmable gate array (FPGA) platforms, enabling decentralized protection without reliance on communication links and avoiding associated latency and reliability issues.

5. Conclusions

In this work, a comparison between grid-following and grid-forming inverters is made, with special attention paid to how they behave particularly under weak grid scenarios and unintentional islanding conditions. Most research demonstrates that although GFL inverters perform well in strong grids, their dependence on the grid reference voltage for synchronization causes them to lose stability in weak grids. GFM inverters, on the other hand, operate as independent voltage sources that can maintain grid conditions without relying on the grid voltage, which demonstrates their higher stability in such circumstances.

Nonetheless, the experimental results indicate that the commonly held assumption of the universal superiority of grid-forming inverters should be carefully reconsidered, particularly for unintentional islanding detection. While GFM inverters are often viewed as inherently better, our findings reveal significant practical drawbacks, such as the increase in the non-detected zone and prolongation of detection times, sometimes failing to meet standards. In contrast, GFL inverters responded to unintentional islanding conditions more quickly and dependably, highlighting that the choice and implementation of technology in contemporary grid applications should be based on inverter performance rather than only control philosophy.

In order to overcome the difficulties presented by both types of inverters, particularly under unintentional islanding scenarios, sophisticated data-driven methods present a potential path. In this work, a Random Forest-based approach for detecting unintentional islanding using voltage, amplitude, frequency, and ROCF as input features is proposed. The RF model accomplished an accuracy of 99.29% and an average prediction time of around 0.2 s, which outperforms both GFL and GFM inverters, especially in terms of detection time. These findings show how machine learning can significantly lower NDZ and increase detection reliability.

This study is based on laboratory-scale experiments on a low-voltage microgrid with inverter ratings of 3.2 kW (GFL) and 20 kW (GFM), where the observed trends are primarily driven by inverter control philosophy rather than absolute power ratings. The qualitative behavior, including NDZ enlargement and prolonged detection time for GFM inverters under close power matching, is expected to persist across different power scales, although quantitative metrics may vary with system inertia and network characteristics. Therefore, while the conclusions are directly applicable to low- and medium-voltage microgrids with similar control structures, further validation on larger, higher-power systems is required to fully generalize the findings.

Overall, the results emphasize the need for a thorough understanding of inverter behavior and the importance of hybrid approaches that combine appropriate control schemes with intelligent detection methods to ensure reliable, standards-compliant microgrid operation under diverse conditions.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to institutional restrictions and confidentiality agreements.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sarhan, M.; Bien, A.; Barczentewicz, S.; Hassan, R. Global Maximum Power Point Tracking (GMPPT) Control Method of Solar Photovoltaic System Under Partially Shaded Conditions. In Proceedings of the 2022 8th International Conference on Automation, Robotics and Applications (ICARA), Prague, Czech Republic, 18–20 February 2022; pp. 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavus, M. Advancing Power Systems with Renewable Energy and Intelligent Technologies: A Comprehensive Review on Grid Transformation and Integration. Electronics 2025, 14, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerch, T.; Barczentewicz, S.; Abu Sarhan, M.; Feng, Z.; Burt, G. Grid tie converters aided rapid grid voltage fluctuation compensation with power hardware-in-the-loop experimental validation. e+i Elektrotechnik Informationstechnik 2025, 142, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Sarhan, M. An extensive review and analysis of islanding detection techniques in DG systems connected to power grids. Energies 2023, 16, 3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Sarhan, M.; Barczentewicz, S.; Lerch, T. Hybrid islanding detection method using PMU-ANN approach for inverter-based distributed generation systems. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2024, 18, 4453–4464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbe, S.C.; Shigenobu, R.; Ito, M. Comparative Study of GFM-grid and GFL-grid in Islanded Operation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies-Asia (ISGT Asia), Brisbane, Australia, 5–8 December 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirmohammad, M.; Azad, S.P. Control and stability of grid-forming inverters: A comprehensive review. Energies 2024, 17, 3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, V.V.; Roselyn, J.P.; Nithya, C.; Sundaravadivel, P. Development of grid-forming and grid-following inverter control in microgrid network ensuring grid stability and frequency response. Electronics 2024, 13, 1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midtsund, T.; Suul, J.A.; Undeland, T. Evaluation of current controller performance and stability for voltage source converters connected to a weak grid. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Symposium on Power Electronics for Distributed Generation Systems, Hefei, China, 16–18 June 2010; pp. 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, X.; Guo, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Lib, F.; Zhao, W. The control strategy for the grid-connected inverter through impedance reshaping in q-axis and its stability analysis under a weak grid. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2020, 9, 3229–3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fan, L.; Miao, Z. Stability control for wind in weak grids. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2018, 10, 2094–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdiyousef, M.; Hoseinizadeh, S.M.; Karimi, H. A Robust Control Strategy in Stationary Frame for Grid-Supporting Voltage Source Converters Under Weak Grid Conditions. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM), Seattle, WA, USA, 21–25 July 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanam, V.; Chowdhury, A.; Ram, T.K.; Namboodiri, A.V.; Singam, B. An Enhanced Control Strategy to Alleviate Weak Grid Oscillations in Type-4 Wind Farms. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress & Exposition Asia (ECCE-Asia), Bengaluru, India, 11–14 May 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE Standards Association. 1547-2003-IEEE Standard for Interconnecting Distributed Resources with Electric Power Systems; IEEE Standards: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liserre, M.; Wang, X. Guest editorial: Special section on modeling, topology, and control of grid-forming inverters. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2020, 8, 923–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluščević, J.; Janda, Ž.; Dragosavac, J.; Ristić, L. Enhancing Stability of Grid-Following Inverter for Renewables. In Proceedings of the 2023 22nd International Symposium on Power Electronics (Ee), Novi Sad, Serbia, 25–28 October 2023; Volume 1, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, N.; Zhou, W.; Bahrani, B. Comparison of PLL-based and PLL-less control strategies for grid-following inverters considering time and frequency domain analysis. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 80518–80538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrani, B. Power-synchronized grid-following inverter without a phase-locked loop. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 112163–112176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, A.W.D.S.; Ribeiro, L.A.d.S.; Savaghebi, M. An Improved Control for Grid-Following Inverter with Active Damping and Capacitor Voltage Decoupling. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), Phoenix, AZ, USA, 20–24 October 2024; pp. 3678–3684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unruh, P.; Nuschke, M.; Strauß, P.; Welck, F. Overview on grid-forming inverter control methods. Energies 2020, 13, 2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasseter, R.H.; Chen, Z.; Pattabiraman, D. Grid-forming inverters: A critical asset for the power grid. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2019, 8, 925–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, N.; Udawatte, H.; Zhou, W.; Hill, D.J.; Bahrani, B. Grid-forming inverters: A comparative study of different control strategies in frequency and time domains. IEEE Open J. Ind. Electron. Soc. 2024, 5, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, K.; Hashimoto, J.; Orihara, D.; Ustun, T.S.; Otani, K.; Kikusato, H.; Kodama, Y. Reviewing control paradigms and emerging trends of grid-forming inverters—A comparative study. Energies 2024, 17, 2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.O.; Li, Z.S.; Luo, X.; Zhang, Q.; Maslennikov, S.; Tbaileh, A. An overview of industry-related grid forming inverter controls. In Proceedings of the 2023 Global Reliability and Prognostics and Health Management Conference (PHM-Hangzhou), Hangzhou, China, 12–15 October 2023; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwan, A.; Elshenawy, M.A.; Mohamed, Y.A.-R.I.; El-Saadany, E.F. Grid-forming voltage-source inverter for hybrid wind-solar systems interfacing weak grids. IEEE Open J. Power Electron. 2024, 5, 956–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zhou, D.; Anvari-Moghaddam, A.; Blaabjerg, F. Stability analysis of grid-following and grid-forming converters based on state-space modelling. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2024, 60, 4910–4920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Meng, K.; Yu, L.; Yuan, L.; Liang, Z. Comparative fault ride through assessment between grid-following and grid-forming control for weak grids integration. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Global Conference on Computing, Power and Communication Technologies (GlobConPT), New Delhi, India, 23–25 September 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Sun, J.; Huang, M.; Tian, Z.; Yan, H.; Iu, H.H.-C.; Hu, P.; Zha, X. Large-signal stability of grid-forming and grid-following controls in voltage source converter: A comparative study. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 36, 7832–7840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, A.; Zhixin, M.; Lingling, F. Stability analysis of two types of grid-forming converters for weak grids. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 2021, 31, e13136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z. From Grid-Following to Grid-Forming: A Review of Converter Technology Paradigm Shift and Its Applications in Renewable-Rich Power Systems. Adv. Eng. Res. Possibilities Chall. 2025, 2, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.A.; Akter, F.; Khaled, S.; Akter, P.; Ullah, K.R. Design of grid forming inverter for integration of large-scale wind farm in weak grid. In Proceedings of the 2022 4th International Conference on Sustainable Technologies for Industry 4.0 (STI), Dhaka, Bangladesh, 17–18 December 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Tuffner, F.K.; Schneider, K.P.; Lasseter, R.H.; Xie, J.; Chen, Z.; Bhattarai, B. Modeling of grid-forming and grid-following inverters for dynamic simulation of large-scale distribution systems. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2020, 36, 2035–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quedan, A.; Wang, W.; Ramasubramanian, D.; Farantatos, E.; Asgarpoor, S. Behavior of a high inverter-based resources distribution network with different participation ratios of grid-forming and grid-following inverters. In Proceedings of the 2021 North American Power Symposium (NAPS), College Station, TX, USA, 14–16 November 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Lee, E.S. Islanding detection method for grid-forming inverter by reactive power injection. In IET Conference Proceedings CP880; The Institution of Engineering and Technology: Stevenage, UK, 2024; Volume 2024, pp. 962–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Kim, M.S.; Lee, E.S. Enhanced Islanding Detection for GFM and GFL Inverters Using Negative Sequence Current Injection. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2025, 72, 10119–10129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Sarhan, M.; Bien, A.; Barczentewicz, S. Use of analytical hierarchy process for selecting and prioritizing islanding detection methods in power grids. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2024, 14, 2422–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngamroo, I.; Surinkaew, T.; Mitani, Y. Intelligence-Driven Grid-Forming Converter Control for Islanding Microgrids. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2025, 13, 1310–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J. New machine learning algorithm: Random forest. In International Conference on Information Computing and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pious, I.K.; Rajalakshmi, A.; Kumar, P.; CM, V.; Nalini, M. Enhancing Prediction Accuracy Through Random Forest in Classification and Regression. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Smart Technologies for Sustainable Development Goals (ICSTSDG), Chennai, India, 6–8 November 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.