Abstract

Museums open to the public must reconcile heritage preservation requirements with energy-conscious microclimate management and visitors’ environmental experience. In historic buildings, indoor conditions are typically controlled primarily for preventive conservation, while opportunities for detailed assessment of human comfort are often limited by existing monitoring systems and operational constraints. This study investigates visitors’ perceptions of thermal conditions and indoor air quality (IAQ) in two branches of the National Museum in Krakow (NMK) characterized by different microclimate-control strategies: the mechanically ventilated and air-conditioned Cloth Hall and the predominantly passively controlled Bishop Erazm Ciołek Palace. A pilot survey was conducted in spring 2023 to capture subjective assessments of thermal sensation and perceived IAQ. These perceptions were contextualized using long-term air temperature and relative humidity data (2013–2023) routinely monitored for conservation purposes. Environmental data were analyzed to assess the stability of indoor conditions and to provide background for interpreting survey responses, rather than to perform a normative evaluation of thermal comfort. The results indicate that visitors frequently perceived the indoor environment as slightly warm and reported lower air quality in the Palace, where air was often described as stale or stuffy. These perceptions occurred despite relatively small differences in monitored air temperature and relative humidity between the two buildings. The findings suggest that ventilation strategy, air exchange effectiveness, odor accumulation, room configuration, and lighting conditions may influence perceived environmental quality more strongly than temperature or humidity alone. Although limited in scope, this pilot study highlights the value of incorporating visitor perception into discussions of energy-conscious microclimate management in museums and indicates directions for further multidisciplinary research.

1. Introduction

Over the years, the perception of the museum’s function has evolved [1,2]. According to the ICOM Statutes [3], a museum is “a non-profit, permanent institution in the service of society and its development, open to the public, which acquires, conserves, researches, communicates and exhibits the tangible and intangible heritage of humanity and its environment for the purposes of education, study and enjoyment”. This broadened understanding, combined with the need to mitigate global climate change, has introduced new challenges related to heritage conservation, indoor environmental quality, visitor and staff comfort, energy efficiency, and operational safety of buildings and collections.

Although conservation, human comfort, and energy efficiency are closely interrelated [4], they frequently remain in tension with one another [5]. Systems designed primarily to enhance visitor comfort may adversely affect collections [6,7], whereas maintaining indoor conditions that simultaneously satisfy conservation requirements and thermal comfort expectations is often associated with increased energy demand and operational costs [4,5,8,9,10,11]. As a result, increasing attention has been directed toward energy-saving technologies and non-technological strategies, particularly in historic buildings where extensive refurbishment is restricted [1,12,13]. These approaches include the use of traditional materials and passive climate-control solutions [14,15,16]. In addition, recent research has focused on the gradual relaxation of strictly defined microclimatic parameters [1,2,11,17,18,19,20].

At the same time, it is well established that defining uniform temperature or humidity values capable of ensuring thermal comfort for all occupants is not feasible [21]. Thermal perception varies substantially with metabolic activity, age, gender, clothing insulation, and cultural background [22,23,24,25]. In recent years, an increasing number of studies have therefore examined the relationship between museum microclimates and perceived environmental comfort, often combining thermal aspects with indoor air quality considerations [26,27,28,29,30].

Nevertheless, it must be emphasized that in museum buildings the primary objective of microclimate control remains the protection of cultural heritage. Temperature and relative humidity requirements for conservation purposes have been widely investigated [5,31,32,33], resulting in numerous guidelines and recommendations, ranging from Thomson’s early proposals [34], through subsequent standards and policies [35,36,37,38], to institution-specific museum instructions. Moreover, due to the diversity of materials present and the typically enclosed nature of exhibition spaces, museums are particularly susceptible to biological contamination, which may pose risks to both collections and occupants and contribute to sick building syndrome (SBS) [39].

Because museum interiors generate highly specific microclimatic conditions, perceived indoor air quality depends on a complex interplay of chemical, physical, and biological factors [40,41,42]. These include pollutants, bioaerosols, volatile organic compounds, lighting conditions, temperature, relative humidity, and air movement. When thermal conditions or perceived air quality are inadequate, negative effects on health, well-being, and comfort may occur, which in the case of visitors can directly influence the reception and overall experience of exhibitions.

2. Aim of the Study

In recent years, several studies have explored the perception of environmental comfort in museum spaces using survey-based research methods. These studies often combine instrumental data on indoor environmental conditions with subjective assessments provided by visitors or staff. Survey-based investigations [28,43] have demonstrated that perceived thermal comfort, indoor air quality, and overall environmental satisfaction are influenced not only by measurable microclimatic parameters but also by individual factors such as age, clothing, expectations, and duration of stay. Visitor surveys further indicate that perceived indoor environmental conditions play a significant role in shaping visitor satisfaction and the overall evaluation of museum experiences.

At the same time, it should be noted that in many museum buildings—particularly historic ones—environmental monitoring systems are primarily designed to support preventive conservation rather than to enable detailed assessments of thermal comfort in the occupied zone. As a result, research opportunities are often constrained to the use of existing long-term monitoring data and simplified survey tools.

The National Museum in Krakow (NMK) maintains defined air temperature (T) and relative humidity (RH) ranges across its branches, reflecting long-established conservation requirements for diverse collections. However, these operational microclimate conditions have not previously been examined in relation to subjective environmental perception reported by visitors and staff.

Considering the above, as well as the limited availability of survey-based studies addressing environmental perception in Polish museums, the present research was conceived as an exploratory pilot study. Its objectives are to:

- (1)

- Explore whether different microclimate-control approaches—mechanical HVAC versus predominantly passive (gravitational) ventilation—are associated with differences in subjective perceptions of thermal conditions and indoor air quality.

- (2)

- Contextualize these subjective perceptions using long-term environmental monitoring data routinely collected for conservation purposes.

- (3)

- Identify architectural, operational, and sensory factors that may contribute to differences in environmental perception between museum spaces.

- (4)

- Indicate directions for future, more comprehensive investigations of environmental comfort and indoor air quality in museum environments.

The study was intentionally designed as a pilot investigation. Its aim was to test the applicability of a survey-based approach under real museum operating conditions and to identify key factors influencing perceived environmental quality, rather than to provide a normative assessment of thermal comfort.

3. Case Study

The NMK is the oldest and the largest museum in Poland in terms of the number of collections. The museum consists of twelve departments located in different buildings. Two of them were selected for pilot studies on shaping the microclimate in exhibition halls and conservation workshops, with a view to environmental comfort: upper hall of the Cloth Hall and Bishop Erazm Ciołek Palace. Both buildings, together with the oldest part of the Old Town of Krakow, are on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

3.1. The Cloth Hall

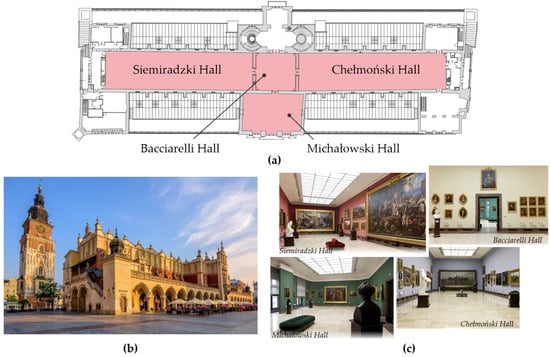

The Cloth Hall is one of the most recognizable buildings in Poland. Situated in the centre of Krakow’s Main Market Square. The building’s history dates back to 1257, when the first stalls were opened in Kraków’s market square. Over the centuries, it was repeatedly rebuilt and expanded, reaching its present form in 1879. In 2010 the building underwent a major renovation. The upper hall, which served as the first seat of the NMK in 1879, currently houses the largest permanent exhibition of 19th-century Polish painting and sculpture. The gallery consists of four interconnected halls named after Bacciarelli, Michałowski, Siemiradzki, and Chełmoński (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Case-study building—The Cloth Hall (Sukiennice) in Krakow: plan of the upper exhibition level with selected halls highlighted (a), exterior view from the Main Market Square (b), and representative interior views of the main exhibition rooms (c) (source of photos: National Museum in Krakow).

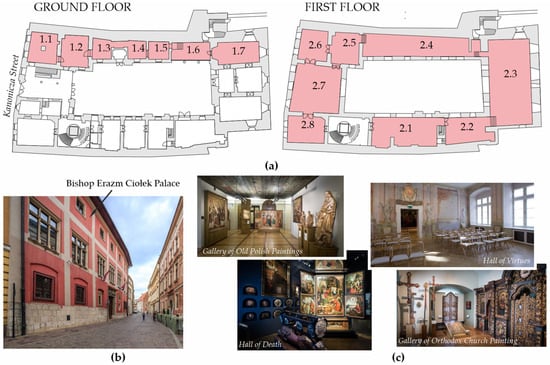

3.2. Bishop Erazm Ciołek Palace

Bishop Erazm Ciołek Palace (hereinafter referred to as the Palace) was built between 1501 and 1503. The building’s architecture reflects traditional Gothic features and Italian Renaissance influences. In 1996, the Palace was transferred to the National Museum in Krakow. Between 1999 and 2006, the building underwent a major renovation. There are a total of 15 exhibition halls on two floors (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Case-study building—Bishop Erazm Ciołek Palace: layout of exhibition rooms on the ground and first floors (a), exterior view from Kanonicza Street (b), and representative interior views of selected galleries (c) (source of photos: National Museum in Krakow).

3.3. Microclimate Control Strategies

According to the internal guidelines of the National Museum in Krakow (NMK), air temperature in exhibition rooms should be maintained within the range of 18–25 °C (18–21 °C during the heating season and below 25 °C outside the heating season). Relative humidity is required to remain within the range of 35–55% during the heating season and 40–60% outside the heating season. These target ranges are defined primarily by preventive conservation requirements and apply to all museum branches irrespective of differences in building technology or ventilation strategy. The air temperature ranges maintained in the museum do not correspond to extreme indoor conditions and fall within values commonly encountered in publicly accessible buildings.

In both investigated buildings, exhibition spaces are operated in accordance with these guidelines; however, the technical means used to achieve and stabilize the desired microclimatic conditions differ substantially.

In both buildings, conservation workshop rooms are equipped with dedicated local exhaust ventilation systems due to the use of chemical agents and materials that require targeted pollutant removal.

3.3.1. Microclimate Control in the Cloth Hall

The Cloth Hall is equipped with a centralized mechanical ventilation and air-conditioning system consisting of four supply and exhaust air-handling units. These units provide heating, cooling, humidification, and dehumidification as required. Two units serve the Chełmoński Hall (a small unit with average and maximum airflows of 1500 m3 h−1 and 8242.8 m3 h−1, respectively, and a large unit with average and maximum airflows of 3305.6 m3 h−1 and 9000 m3 h−1), while two units serve the Siemiradzki Hall (a large unit with average and maximum airflows of 1200 m3 h−1 and 6188.0 m3 h−1, and a small unit with average and maximum airflows of 2553.6 m3 h−1 and 5000 m3 h−1, respectively).

Conditioned outdoor air is supplied through wall-mounted air diffusers located above floor level, while exhaust air is removed via ceiling outlets. Additionally, underfloor heating can be activated when required to support thermal control during the heating season.

The ventilation system was previously evaluated within the framework of the Heriverde project (Energy efficiency of museums, archives and libraries), which focused on assessing different microclimate-control strategies in terms of energy performance [44]. As part of this project, air velocity was measured directly at the supply outlets and reached approximately 0.3 m·s−1. These measurements were performed using an anemometer with a measuring range of 0.1–20 m·s−1 and an accuracy of approximately ±(2–5%) of the reading. The reported value characterizes air velocity at the diffuser level and is provided here solely to describe system operation rather than to evaluate thermal comfort conditions in the occupied zone.

3.3.2. Microclimate Control in the Bishop Erazm Ciołek Palace

The Bishop Erazm Ciołek Palace is not equipped with a centralized air-conditioning system. During the summer period, when the risk of elevated relative humidity increases, portable dehumidifiers are used locally. In winter, space heating is provided by a conventional water-based heating system, which is typical for historic buildings in Kraków. To limit excessive air drying during the heating season, local humidifiers are operated as needed.

Previous investigations conducted by museum staff, including blower door testing, indicated an average air exchange rate of approximately 0.4 h−1 for the building. This value is reported to characterize the overall ventilation conditions of the Palace rather than to serve as a parameter for comfort assessment.

4. Materials and Methods

To investigate subjective environmental perceptions of visitors and employees in selected branches of the National Museum in Krakow (NMK), an exploratory, survey-based field study was conducted. The research combined subjective assessments of perceived thermal conditions and indoor air quality with an analysis of long-term air temperature and relative humidity data routinely monitored for conservation purposes. The environmental data were used exclusively to provide contextual background for the survey results rather than to perform a normative assessment of thermal comfort.

In parallel, semi-structured, informal interviews were carried out with museum staff, including employees working in exhibition rooms as well as conservators employed in conservation workshops (painting conservation in the Cloth Hall and wood conservation in the Palace). These interviews were intended to support the interpretation of survey findings and to identify recurring qualitative observations related to environmental perception. Selected interviews were repeated in June 2025 in order to verify the persistence of reported issues.

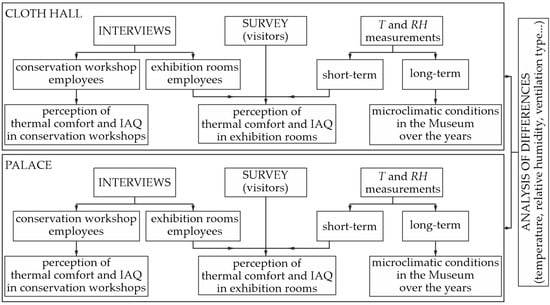

Figure 3 illustrates the logical structure of the study, emphasizing the exploratory nature of the research and the separation between subjective perception data and conservation-driven environmental monitoring.

Figure 3.

Conceptual flow chart of the exploratory research framework applied in the study. Subjective perceptions of thermal conditions and indoor air quality (IAQ) reported by visitors and museum staff were collected through surveys and interviews. Long-term air temperature (T) and relative humidity (RH) data routinely monitored for conservation purposes were analyzed separately to provide contextual background for the interpretation of survey results. The diagram illustrates the logical structure of the study rather than a causal or normative assessment of environmental comfort.

4.1. Survey Research

The surveys were administered on selected days in March, April, and May 2023. An analysis of ticket sales from previous years indicated that this period corresponds to the peak visitor season at NMK branches. Conducting the survey during this timeframe maximized the potential number and diversity of respondents.

The subjective assessment was conducted in situ under real museum visiting conditions using a convenience sampling approach. No a priori target sample size was defined. Participation was voluntary, and all valid questionnaires returned during the survey period were included in the analysis. This approach is consistent with the exploratory and descriptive character of the study and with the transient nature of museum occupancy.

To assess visitors’ subjective perceptions of the indoor environment, a concise questionnaire was developed, comprising the following components:

- General background questions, including:

- gender,

- age group (under 25 years, 25–50 years, over 50 years),

- size of the place of residence (less than 100,000 inhabitants; 100,000–500,000 inhabitants; over 500,000 inhabitants),

- whether the visit was the respondent’s first visit to NMK.

The last two questions were included at the request of NMK for institutional purposes and were not used in further analyses.

- 2.

- Target questions addressing perceived environmental comfort, including:

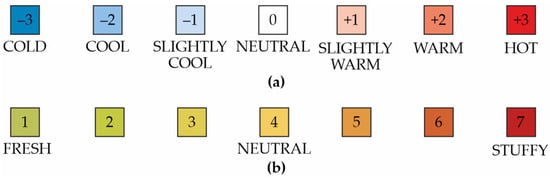

- assessment of thermal sensation using the ASHRAE seven-point thermal sensation scale (−3 cold; −2 cool; −1 slightly cool; 0 neutral; +1 slightly warm; +2 warm; +3 hot) (Figure 4a),

Figure 4. Seven-point subjective scales used in the survey: (a) thermal sensation scale based on the ASHRAE framework; (b) perceived indoor air quality scale ranging from fresh to stuffy. The scales were used to capture subjective perceptions under real museum visiting conditions and were not intended to support a normative evaluation of thermal comfort.

Figure 4. Seven-point subjective scales used in the survey: (a) thermal sensation scale based on the ASHRAE framework; (b) perceived indoor air quality scale ranging from fresh to stuffy. The scales were used to capture subjective perceptions under real museum visiting conditions and were not intended to support a normative evaluation of thermal comfort. - assessment of perceived indoor air quality using a seven-point scale (Figure 4b),

- assessment of air quality based on the perception of odorous substances, with the possibility to specify detected odors,

- perception of differences between individual exhibition rooms (YES/NO; if YES, specification),

- an open-ended question allowing respondents to provide general comments on thermal conditions and air quality.

A seven-point response scale was selected due to its widespread use in environmental perception studies and its ease of interpretation by respondents.

No questions related to respondents’ health status or psychophysical condition were included in order to maintain a concise, non-intrusive survey format suitable for museum visits. This limitation is acknowledged and discussed later in the paper.

In the Cloth Hall, the survey covered all exhibition rooms. In the Palace, due to the larger number of exhibition spaces, four representative rooms were selected after site inspections and preliminary consultations with museum staff (Figure 2):

- The Gallery of Orthodox Church Painting (room 1.7), located farthest from the entrance on the ground floor and characterized by microclimatic conditions reported by staff as differing from other spaces.

- The Gallery of Old Polish Paintings (room 2.4), selected as representative of typical exhibition rooms in the Palace.

- The Hall of Death (room 2.6), chosen due to its distinctive architectural design and reduced lighting levels, which may influence environmental perception.

- The Hall of Virtues (room 2.7), characterized by a spacious layout and access to natural light.

In addition to the visitor survey, interviews were conducted with employees working in the exhibition halls as well as with staff from the conservation workshops (painting in the Cloth Hall and wood in the Palace). These interviews were not formalized.

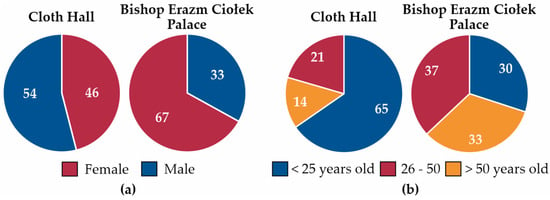

In the Cloth Hall, 78 people participated in the survey: 36 women (46%) and 42 men (54%). In the Palace, 70 people completed the survey: 47 women (67%) and 23 men (33%) (Figure 5a). The age structure for the visitors to the two buildings differed (Figure 5b):

Figure 5.

Percentage distribution of respondents by gender (a) and age categories (b) for the two investigated museum buildings.

- In the case of the Cloth Hall, the largest group of visitors were people under 25 years of age (20 women and 31 men), followed by visitors over 50 years of age (10 women and 6 men). The smallest group consisted of people aged 25–50 (6 women and 5 men).

- In the case of the Palace, the age distribution was relatively even, with the oldest visitors forming the largest group (19 women and 7 men) and the youngest forming the smallest (15 women and 6 men).

4.2. Microclimate Monitoring

Both investigated NMK branches continuously monitor air temperature (T) and relative humidity (RH) in exhibition rooms as part of their preventive conservation strategy. Measurements are recorded at five-minute intervals, with measurement uncertainties of ±0.3 °C for temperature and ±3% for relative humidity.

The monitoring system, supplied by Hanwell Instruments Ltd. (Letchworth, UK), is specifically designed for museum and heritage applications and is widely used in major international museums. Its primary function is the protection of collections rather than the assessment of human thermal comfort. To minimize visual impact and reduce risks to exhibits, sensors are installed outside the occupied zone, typically at a height of approximately 2.0 m and in proximity to the most sensitive objects.

For the purposes of this study, a simplified analysis of monitoring data from 2013 to 2023 was performed. Basic descriptive statistics were calculated, and correlations between individual exhibition rooms were examined using Spearman’s correlation coefficient. This analysis was intended solely to demonstrate the long-term stability and continuity of microclimatic conditions in the museum spaces and to provide contextual background for the interpretation of survey results. Accordingly, the monitoring data were not used to derive comfort indices or to evaluate compliance with thermal comfort standards.

Measured air temperature and relative humidity values were compared with reference ranges commonly applied in museum conservation practice, as defined in conservation-oriented guidelines and standards such as EN 15757 [44], which focuses on the assessment of climate suitability for the preservation of cultural heritage rather than on human thermal comfort. These references were used to verify the stability and acceptability of conservation conditions over time and to contextualize the environmental background in which the subjective survey was conducted.

It should be emphasized that conservation standards and guidelines address microclimatic parameters primarily from the perspective of material preservation and do not aim to characterize thermal comfort conditions experienced by occupants. In the present study, the term microclimate therefore refers exclusively to the parameters routinely monitored and controlled in museum practice for conservation purposes, namely air temperature and relative humidity. These parameters do not constitute a comprehensive description of thermal comfort, which would additionally require information on mean radiant temperature, air velocity, metabolic rate, and clothing insulation.

Although visitors in museum spaces are typically standing or walking, resulting in metabolic rates higher than those assumed for sedentary conditions, their activity is inherently variable and transient and does not correspond to the steady-state assumptions underlying standard thermal comfort models. For this reason, the application of comfort categories or fixed operative temperature ranges was intentionally avoided. Instead, the analysis focuses on air temperature as a reference environmental parameter consistently available from long-term conservation monitoring.

5. Results

5.1. Microclimate Analysis

A simplified analysis of data collected at both NMK branches between 2013 and 2023 was conducted. The aim of this analysis was to assess the stability of the microclimate and to identify differences between individual exhibition rooms. It also examined potential differences between the Cloth Hall and the Palace on the days when the survey was conducted.

5.1.1. Long-Term Measurements

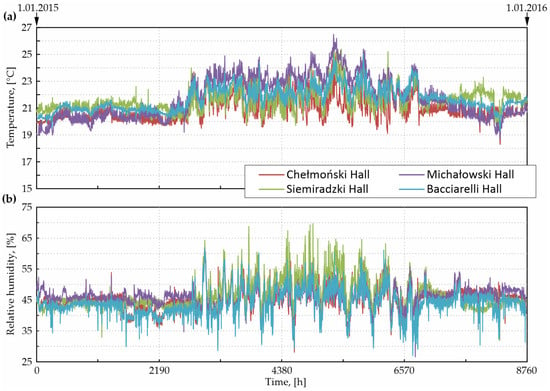

In the Cloth Hall, air temperatures recorded during the analysed period ranged from 17.4 to 27.5 °C. Although average temperature levels across the exhibition rooms were comparable, distinct patterns of temporal variation were observed between individual spaces. These differences persisted throughout the year, regardless of the season (Figure 6). The lowest temperatures were consistently recorded in the Chełmoński Hall, while the highest values occurred in the Michałowski Hall. The Bacciarelli Hall exhibited the smallest annual temperature amplitude (5.7 K), whereas the Michałowski Hall showed the largest amplitude (7.8 K); notably, it is the only exhibition room illuminated by daylight.

Figure 6.

Annual profiles of air temperature (a) and relative humidity (b) measured in 2015 in the exhibition halls of the Cloth Hall as part of conservation-oriented microclimate monitoring.

Over time, temperature differences between individual rooms have decreased as a result of improvements in air-conditioning control. In 2015, inter-room temperature differences reached up to 3 K, whereas in recent years they have not exceeded 1.3 K. A similar trend was observed for relative humidity: maximum differences between rooms reached 15% in 2015 and currently amount to approximately 8%.

Spearman’s correlation coefficients for air temperature ranged from 0.532 to 0.905. Given that all exhibition halls are interconnected and that doors between rooms remain open, a high degree of correlation between measurements is expected despite differences in local temperature profiles. Strong correlations were observed between the Chełmoński, Michałowski, and Bacciarelli Halls. In contrast, the Siemiradzki Hall exhibited only moderate correlation with the remaining spaces. For relative humidity, correlations were generally weaker, ranging from 0.357 to 0.827, with the lowest correlation again observed for the Siemiradzki Hall. This behaviour may be attributed to the presence of a door leading to a corridor with access to a balcony that is frequently used by employees, resulting in intermittent air exchange and local disturbances of microclimatic conditions.

Despite improved control of the air-conditioning system, minor and short-term exceedances of the microclimatic ranges adopted by NMK have occasionally occurred (Figure 7). From a preventive conservation perspective, these deviations are considered insignificant and do not pose an increased risk to the collections. The monitored temperature levels remained within moderate values and do not indicate the presence of extreme indoor thermal conditions.

Figure 7.

Air temperature (a) and relative humidity (b) recorded in the Chełmoński Hall between 2021 and 2023, shown against the background of the microclimatic target ranges adopted by the National Museum in Krakow for preventive conservation (grey shading).

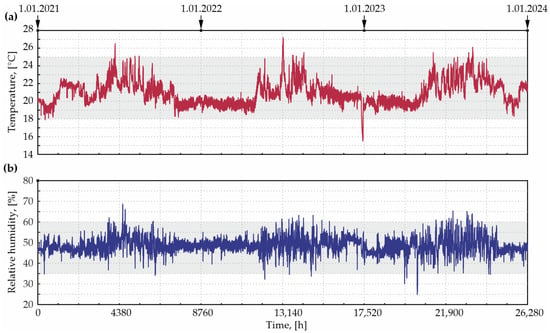

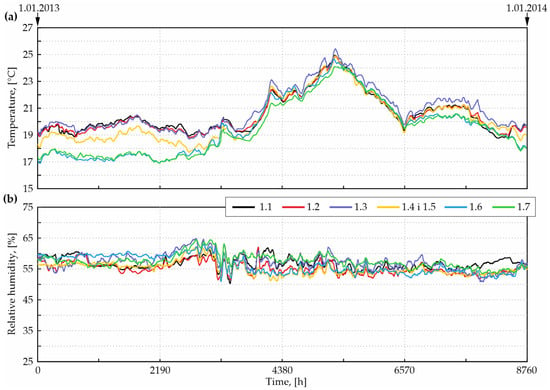

Analysis of long-term monitoring data indicates that the microclimate in the Palace has remained generally stable since 2013, despite the absence of active climate-control systems during the summer months. Nevertheless, clear differences in air parameters were observed between the ground-floor and first-floor galleries. On the ground floor, air temperatures ranged from 13.2 to 26.0 °C and relative humidity from 31.8% to 75.1%. On the first floor, temperatures ranged from 13.2 to 30.5 °C and relative humidity from 26.5% to 71.3%. Temperatures below 16 °C occurred only sporadically and were limited to 2016; in all other years, the minimum recorded temperature on both floors was 16.6 °C.

Statistical analysis revealed substantial convergence in temperature variability across the rooms. Spearman’s correlation coefficients indicated strong or very strong correlations for air temperature, ranging from 0.821 to 0.966 on the ground floor and from 0.868 to 0.995 on the first floor. In contrast, correlations for relative humidity were considerably lower, ranging from 0.327 to 0.768 on the ground floor and from 0.150 to 0.852 on the first floor. On the first floor, the Death Room (room 2.6) exhibited the weakest correlation with the remaining rooms in terms of relative humidity.

Despite high correlation coefficients, notable differences in absolute temperature values were observed, particularly on the ground floor during the heating season. This effect was especially pronounced in room 1.7, where the temperature difference relative to the warmest room periodically reached 8.5 K, compared with an average inter-room difference of approximately 1.2 K for the remaining spaces. Variability in relative humidity was lower, with the maximum observed difference amounting to 18.7%.

As illustrated in Figure 8 and Figure 9, the microclimatic ranges adopted by NMK were periodically exceeded, particularly during summer periods. However, these exceedances are considered acceptable from the perspective of preventive conservation. It should be emphasized that short-term fluctuations in air temperature generally pose a lower risk to museum collections than comparable fluctuations in relative humidity.

Figure 8.

Long-term monitoring data for the Bishop Erazm Ciołek Palace (ground floor) in 2013: air temperature (a) and relative humidity (b) recorded in selected exhibition rooms.

Figure 9.

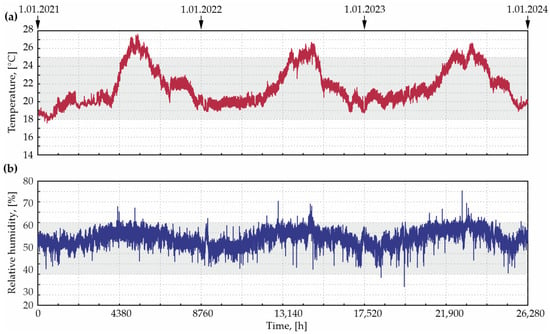

Air temperature (a) and relative humidity (b) recorded in the Palace between 2021 and 2023, shown against the background of the microclimatic target ranges adopted by the National Museum in Krakow for preventive conservation (grey shading).

In recent years, rising outdoor temperatures associated with climate change have contributed to higher summer indoor temperatures, extending the duration of periods during which the adopted microclimatic limits are exceeded (Figure 9). These observations provide important contextual background for the interpretation of subjective survey results but are not intended to constitute an assessment of thermal comfort conditions.

5.1.2. Microclimate During Survey Research

On the days when the surveys were conducted, air temperature in the exhibition rooms varied from 19.8 to 23.8 °C in the Cloth Hall and from 19.6 to 22.2 °C in the Palace. During museum opening hours, these ranges were narrower, amounting to 20.1–22.5 °C in the Cloth Hall and 20.2–22.2 °C in the Palace.

Relative humidity during the same period ranged from 38.3% to 75.1% in the Cloth Hall and from 49.9% to 59.2% in the Palace. As observed for air temperature, relative humidity exhibited smaller fluctuations during opening hours, ranging from 44.4% to 54.5% in the Cloth Hall and from 48.7% to 57.4% in the Palace.

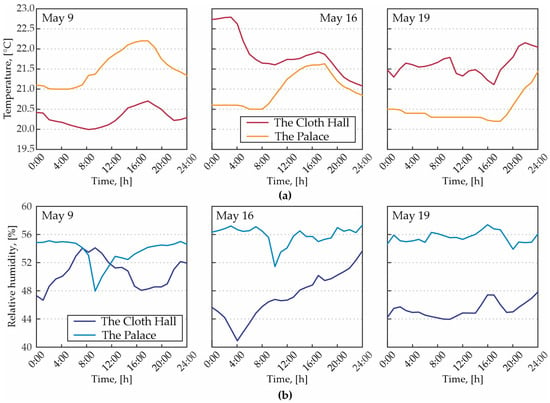

Figure 10 presents the variability of air temperature and relative humidity for the selected days on which the surveys were conducted. The recorded values correspond to moderate indoor environmental conditions and do not indicate the presence of extreme thermal or hygrometric situations during visitor occupancy. These conditions provide a consistent environmental background for interpreting the survey results. They suggest that observed differences in perceived comfort and indoor air quality are unlikely to be driven by pronounced variations in air temperature or relative humidity alone.

Figure 10.

Mean hourly air temperature (a) and relative humidity (b) in the Cloth Hall and the Bishop Erazm Ciołek Palace for selected survey days in May 2023.

The indoor climate did not differ significantly between individual rooms on the survey days. In the Cloth Hall, the maximum temperature difference was 1.3 K. In the Palace, the maximum ground-floor temperature difference (depending on the day) ranged from 0.6 to 1.1 K, while on the first floor the differences were even smaller, reaching approximately 0.5 K. The daily temperature amplitude in all rooms did not exceed 1.5 K.

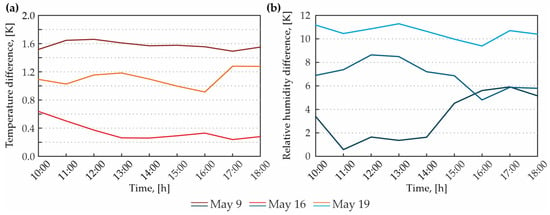

From the perspective of comparing the survey results, it is necessary to consider the microclimatic conditions in both buildings. The maximum temperature difference between the Cloth Hall and the Palace on the days when the surveys were conducted was 2.2 K, while the maximum difference in relative humidity reached 15.8%. However, during opening hours the differences were smaller, with temperature differences not exceeding 2 K and relative humidity differences not exceeding 12% (Figure 11). The average temperature difference was 1 K, and the average difference in relative humidity was 6.9%.

Figure 11.

Differences in mean air temperature (a) and mean relative humidity (b) between the Cloth Hall and the Bishop Erazm Ciołek Palace during selected survey days in May 2023.

5.2. Survey Results

5.2.1. Thermal Comfort

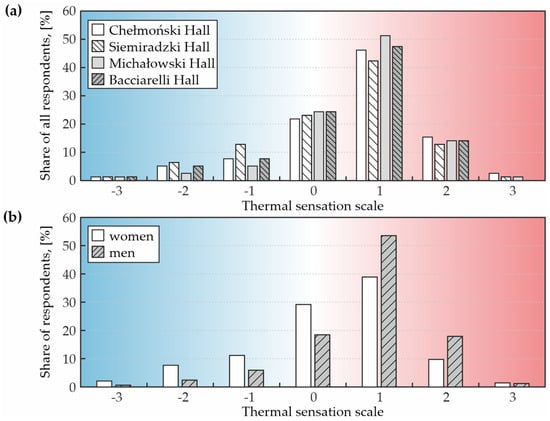

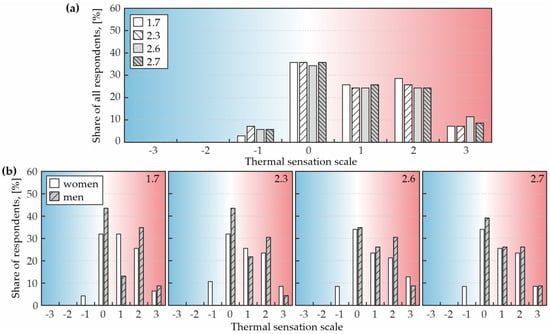

In the Cloth Hall, more than 20% of respondents rated the climate as neutral. Depending on the room, this share ranged from 21.8% to 24.4% (Figure 12a). The majority assessed it as warm:

Figure 12.

Subjective thermal sensation votes recorded in the Cloth Hall during the survey period, presented by exhibition room (a) and by gender (b).

- as slightly warm (+1 on the scale)—42.3–51.3% depending on the room,

- as warm (+2 on the scale)—12.8–15.4% depending on the room.

Significantly fewer people rated it as cool:

- as slightly cool (–1 on the scale)—5.1–12.8% depending on the room,

- as cool (–2 on the scale)—2.6–6.4% depending on the room.

The microclimate was assessed as either cold or hot only by individual respondents. At the same time, none of the surveyed individuals indicated significant differences in thermal sensations between the rooms. It should be noted that the majority of men (over 50%, regardless of the room) assessed the microclimate as slightly warm, while about 20% rated it as neutral or warm. Among women, approximately 40% assessed the microclimate as slightly warm, around 30% as neutral, and about 10% each as warm or slightly cool (Figure 12b). The differences between individual rooms were small, allowing the use of average values.

In the case of the Palace, none of the respondents assessed the microclimate in the rooms as cold or cool (–3 and –2 on the scale) (Figure 13a). Depending on the room, slightly cool (–1 on the scale) was indicated by 2.9–7.1% of respondents, neutral (0 on the scale) by 34.3–35.7%, slightly warm (+1 on the scale) by 24.3–25.7%, warm (+2 on the scale) by 24.3–28.6%, and hot (+3 on the scale) by 7.1–11.4%. Overall, women rated the microclimate as cooler than men (Figure 13b). Only women rated it as “slightly cool” (–1 on the scale). Older respondents tended to rate the climate as warmer (for example, only men in the highest age group rated it as hot, and none of the women in the same age group rated it as slightly cool).

Figure 13.

Subjective thermal sensation votes recorded in the Palace during the survey period, presented by exhibition room (a) and by gender (b).

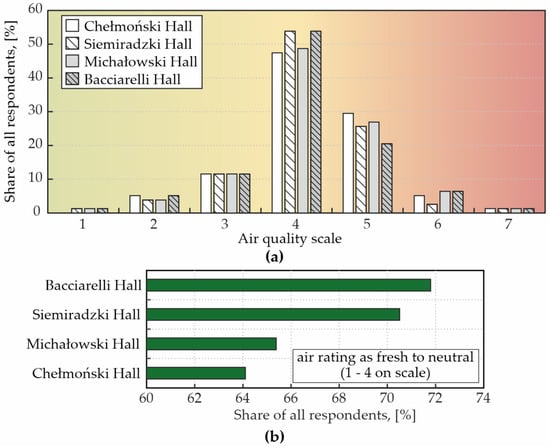

5.2.2. Air Quality

Air quality in the exhibition rooms of the NMK in the Cloth Hall can be assessed, based on the surveys, as average. Overall, positive impressions (ratings from 1 to 4 on the scale), depending on the room, were reported by 64.1–71.8% of respondents (Figure 14a). However, only one person described the air quality as unequivocally “fresh.” The vast majority rated it as “neutral.” The air quality in the Bacciarelli Hall was considered the best, while that in the Chełmoński Hall was considered the worst. No significant differences were observed between the ratings given by women and men. Only one respondent reported an unpleasant odor, describing it as the smell of paint in the Chełmoński Hall. This same respondent was also the only person to indicate a noticeable difference in air quality between rooms.

Figure 14.

Distribution of subjective indoor air quality ratings reported by visitors in the Cloth Hall: results for individual exhibition rooms (a) and the share of respondents reporting air quality rated from fresh to neutral (ratings 1–4 on the applied scale) (b).

The sample size is relatively small, so the results are uncertain. Therefore, it is not possible to clearly determine which room has the best air-quality rating. However, comparing the percentage of people who rated the air quality in individual rooms as satisfactory (Figure 14b), it can be concluded that the Bacciarelli Hall (71.8%) received the highest rating, while the Chełmoński Hall (64.1%) received the lowest.

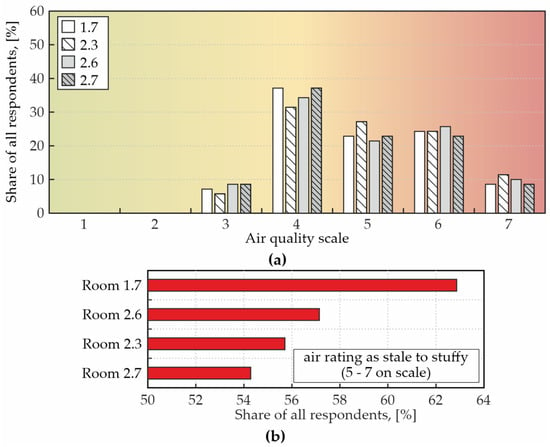

In the case of the Palace, only 37.1–45.7% of respondents (depending on the room) assessed the air quality as satisfactory (ratings from 1 to 4 on the scale) (Figure 15a). However, none of the respondents selected levels 1 or 2, which characterize the air as fresh. This means that, according to the respondents, the air in the Palace is perceived as stale. Additionally, about 10% of respondents described the air as stuffy (stagnant, poorly ventilated, and lacking freshness).

Figure 15.

Distribution of subjective indoor air quality ratings reported by visitors in selected exhibition rooms of the Palace: full distribution of ratings (a) and the share of respondents reporting unsatisfactory air quality (ratings 5–7 on the applied scale) (b).

A preliminary assessment does not clearly indicate which room has the highest or lowest air quality. However, based on Figure 15b, it can be concluded that room 1.7 (Gallery of Orthodox Church Painting) received the lowest rating (61.4% of respondents assessed the air as unsatisfactory, 11.4% of whom described it as stuffy). The best rating was given to room 2.7 (Hall of Virtues), with 54% of respondents dissatisfied with the air quality (8.6% rated it as stuffy).

More than 30% of respondents reported the presence of undesirable odors, describing them primarily as the smell of old and damp wood. Fewer than 5% of those surveyed noted significant differences in perceived air quality between rooms.

5.3. Interviews with Employees

Interviews were conducted during the survey and repeated in June 2025. They involved exhibition staff, conservation workshop employees, and members of the museum prevention department.

5.3.1. Exhibition Rooms

According to the interviews conducted, employees did not report any negative sensations, in connection with their own feelings, related to temperature or air humidity in any of the surveyed branches. However, in the case of the Palace, they noted frequent feelings of stuffiness in the rooms—particularly in room 1.7. In the Cloth Hall, staff reported recurring episodes of unpleasant odors originating from the restaurant kitchen located beneath the museum rooms.

Exhibition hall staff reported numerous visitor complaints regarding temperature and perceived air quality. These concerns were noted in both departments and were particularly frequent during the summer period. In the Cloth Hall, complaints most frequently concerned temperatures perceived as too low, whereas in the Palace they pertained to temperatures perceived as too high. According to staff, however, the primary issue reported by visitors relates to the perceived air quality in the Palace.

5.3.2. Conservation Workshops

Microclimatic conditions in conservation workshops were assessed positively. Employees expressed overall satisfaction with both thermal comfort and air quality. However, in the Palace, they noted occasional days when temperatures exceeded thermal comfort limits.

All employees noted that their expectations regarding air quality are lowered. This is attributed to their awareness of the necessity of using chemical agents and their familiarity with the associated odors. In the conservation workshops, employees are exposed to intense and often irritating odors originating from solvents (e.g., acetone, toluene), resins (e.g., turpentine), aldehydes (with fruity, marine, or floral notes), as well as pigments containing metals such as cadmium and cobalt, and various additives, including essential oils and aromatic resins. Together, these substances create a complex, sometimes strongly chemical mixture that may pose health risks. Due to the above mechanical exhaust ventilation is necessary. The only concern raised by employees of both workshops related to the method of controlling individual exhaust systems.

5.3.3. Museum Prevention Department

The interview with the Museum Prevention Department aimed to define the strategy for microclimate control in the exhibition halls. It also sought to identify issues associated with both active and passive management methods. The Museum’s microclimate control strategy was developed on the basis of contemporary research on the relationship between material degradation and microclimate parameters. The strategy also takes into account the energy demand of the control mechanisms used. It was emphasized that permissible ranges of temperature and relative humidity fluctuations should be individually determined according to the specific conservation requirements of the exhibited and stored objects. All branches of the Museum are located in historic buildings, several of which form part of the UNESCO-listed historic center of Krakow. As a result, any proposed thermal-modernization measures are subject to rigorous conservation oversight. So, each case is presented as an independent case study:

- Preservation of the historical microclimate, whenever feasible, constitutes a fundamental priority. This encompasses the environmental conditions (mean values, seasonal cycles, and short-term fluctuations) under which the objects have historically existed without exhibiting signs of deterioration. In order to determine the historical climate, the EN 15757 standard [44] recommends monitoring ambient temperature and relative humidity for a minimum of 12 months to capture annual variability, including heating and cooling seasons. The standard does not prescribe fixed temperature or humidity setpoints; instead, it defines acceptable fluctuation ranges—referred to as “proven fluctuations”—derived from the historical microclimatic record.

- In buildings where the indoor climate is predominantly passive, organizing temporary exhibitions that include works borrowed from other institutions is virtually impossible. In such situations, it is necessary to adapt the exhibition environment to the climatic conditions prevailing in the lending institutions.

- The potential need for regulating visitor numbers should be taken into consideration.

6. Discussion

Museums operate in environments that require a multi-objective approach in which heritage preservation, indoor environmental management, and energy performance must be considered simultaneously. The cultural and historical value of museum collections necessitates stable environmental conditions primarily defined by preventive conservation requirements. At the same time, climate change and the ongoing energy crisis intensify the need to reduce energy consumption associated with indoor climate control, particularly in historic buildings where extensive technical interventions are limited.

In this context, one recognised strategy for improving energy efficiency is the careful relaxation of overly strict microclimatic setpoints, provided that such adjustments remain compatible with conservation requirements and do not increase the risk of damage to collections. This approach has been widely discussed as a means of reducing dependence on fully mechanical air-conditioning systems and enabling a greater role for passive or hybrid solutions in heritage buildings.

The National Museum in Krakow applies relatively broad acceptable ranges for air temperature and relative humidity (18–25 °C and 35–60%), which were defined on the basis of historical microclimate analyses and established conservation requirements. Based on previous studies—including analyses of system performance [45] and investigations into the potential impact of relaxed microclimate requirements on energy use [2,46,47]—it can be cautiously suggested that the Museum’s microclimate-control strategy may contribute to improved energy efficiency. However, confirming this hypothesis would require a dedicated and comprehensive energy assessment, which was beyond the scope of the present study.

Environmental conditions in the investigated buildings are maintained through a combination of central technical systems and local devices. Short-term and minor exceedances of the adopted microclimatic limits are considered unlikely to pose immediate risks to the collections, although the present study did not assess their possible long-term cumulative effects. While the adopted ranges appear reasonable in light of current conservation practice, they may benefit from further refinement as additional monitoring data and conservation evidence accumulate.

Against this background, it should be emphasized that the purpose of this article is not to evaluate conservation thresholds, thermal comfort criteria, or energy performance in a normative manner. Instead, the study focuses on exploring how visitors perceive indoor environmental conditions that are primarily managed according to conservation-driven requirements, within the broader context of energy-conscious museum operation.

6.1. Limitations of the Study

A key limitation of this study is the relatively small number of completed questionnaires collected in both investigated buildings. Participation among international visitors was limited because the surveys were available only in Polish, and some visitors chose not to respond. As a result, the obtained sample may be unbalanced and may underrepresent certain visitor groups, which restricts the generalisability of the observed trends. This limitation is inherent to the pilot character of the study, which was not intended to produce statistically representative results but rather to explore preliminary patterns in visitor perception under real museum operating conditions.

Despite the limited sample size, the survey provided valuable qualitative insights, particularly with regard to the differing frequency and nature of air-quality-related complaints reported in the two buildings. These preliminary findings helped identify potential problem areas and informed methodological adjustments planned for subsequent research stages, including the extension of the survey period and the use of multilingual questionnaires.

Another important limitation concerns the scope of environmental data analysis. In the present study, only air temperature and relative humidity were examined, using long-term monitoring data collected for preventive conservation purposes. This simplified approach reflects the exploratory nature of the project and the practical constraints of conducting research in operational museum spaces, where researchers have no control over sensor placement or monitoring strategies. The intention was not to provide a comprehensive physical characterisation of the indoor environment, but rather to contextualise subjective survey responses and verify whether reported perceptions occurred under moderate and stable environmental conditions.

Consequently, the analysis does not capture all aspects of microclimatic variability, including local effects within the occupied zone or seasonal differences beyond the monitored parameters. Future studies should therefore expand the range of environmental indicators and incorporate more detailed spatial and temporal analyses to support a more robust interpretation of visitor perceptions.

6.2. Thermal Perception

The principal operational difference between the two investigated buildings is the presence of year-round mechanical air conditioning in the Cloth Hall, whereas the Palace relies predominantly on passive microclimate control outside the heating season. During the survey period, however, relatively low outdoor temperatures (10–16 °C) resulted in active heating in both buildings. As a result, although the temporal patterns of temperature variation differed, the air temperature ranges recorded during survey days were comparable in both locations.

Despite these similarities, visitors reported differences in thermal perception between the buildings and between individual rooms. In both NMK branches, respondents tended to assess the indoor environment as slightly warm or warm rather than neutral. In the Palace, perceptions appeared somewhat less favourable, particularly in the Death Hall, where a noticeable share of respondents reported feeling hot. These findings suggest that subjective thermal perception may vary even under relatively stable and moderate air temperature conditions.

Measurement data indicate that temperature differences between rooms were generally small; however, previous research has shown that occupants can perceive temperature differences well below 2 K, and under controlled conditions even differences of 0.5–1.0 K may be detectable [48,49]. Whether such differences translate into discomfort depends strongly on contextual factors, including exposure time, clothing, metabolic activity, and recent thermal history [50,51,52]. In the present case, the Death Hall differs markedly from other rooms in terms of spatial scale, lighting conditions, and exhibition design. Reduced lighting levels and smaller room dimensions may influence thermal sensation, either directly or through psychological and perceptual mechanisms [53,54,55,56].

It should also be noted that air temperature alone is insufficient to explain thermal perception. Although relative humidity can influence comfort, numerous studies indicate that at moderate indoor temperatures its effect on thermal sensation is limited, even across a broad humidity range [57,58]. Given that relative humidity levels in both buildings remained within moderate values during the survey period, the observed differences in perception are unlikely to be driven primarily by humidity.

Overall, the results suggest a tendency for visitors to perceive the museum environment as warmer than might be expected based on air temperature data alone. This tendency should be interpreted cautiously, given the limited scope of the survey, but it is consistent with the activity patterns typical of museum visits. Visitors are predominantly standing and walking, which implies higher and more variable metabolic activity than that assumed in steady-state reference scenarios. Under such conditions, even moderate air temperatures may be perceived as warm, particularly when opportunities for adaptation are limited.

From a methodological perspective, these findings highlight the challenges of applying standard thermal comfort concepts to heritage buildings. Such buildings are characterized by transient occupancy, conservation-driven environmental control, and strong contextual cues. Rather than indicating deficiencies in existing comfort models, the results underscore the need to consider adaptive, behavioural, and psychological factors when interpreting thermal perception in museum environments.

6.3. Indoor Air Quality

Regarding IAQ, the exhibition halls in the Palace received lower ratings than those in the Cloth Hall. In the Palace, the Gallery of Orthodox Church Painting (room 1.7) was evaluated particularly poorly. The survey results appear to align with staff observations suggesting worse environmental comfort in this hall compared to the rest of the building, although the exact causes were not determined. As with thermal comfort, the Hall of Virtues (room 2.7) received the highest air quality rating, while its adjacent room—the Hall of Death (room 2.6)—was rated significantly lower. It may be worth considering whether these differences are partly related to interior design characteristics. A brighter, more spacious room with identical microclimate parameters may be perceived as offering better environmental comfort. A similar situation may occur in room 1.7, which visitors enter from a brighter, more open gallery with fewer exhibits.

As with thermal comfort, summertime brings more complaints about air quality, particularly regarding stuffiness and odors. Staff interviews indicate that visitors sometimes report “basement smells” or the scent of “old, wet wood.” It should also be noted that repeated interviews with the Cloth Hall employees revealed occasional odor-related complaints in that building as well—particularly in the Siemiradzki Hall. The nature of these odors differs; on some days, visitors perceive smells originating from the restaurant located beneath the gallery. During an on-site visit by ventilation and air-conditioning specialists, it was observed that the fresh-air intake for one of the air-conditioning units was positioned too close to the restaurant’s exhaust outlet.

In many studies, levels of indoor pollutants (CO2, VOCs, PM10, PM2.5) in older buildings are significantly higher than in newer structures [59,60]. However, both historic buildings discussed here have undergone recent comprehensive renovations and have been adapted to contemporary standards. The age of the buildings can likely be ruled out as the primary cause of negative air quality assessments, although the influence of other factors remains possible.

Despite ongoing complaints about air quality in the Palace and visible fungal growth on a wall in the exhibition room, two microbiological surveys were conducted in 2016 and 2017, as detailed in [61]. Samples from the affected wall revealed several fungal species, including Aspergillus fumigatus and Parengyodontium album. Air samples contained spores from 45 species, some capable of damaging exhibits and the building, as well as posing health risks. Identified fungi included A. fumigatus, P. album, and Bjerkandera adusta. A. fumigatus, Rhizomucor sp., and Scopulariopsis brevicaulis fall into Biosafety Level 2, meaning they can cause disease but are unlikely to spread widely [62,63].

Laboratory cultures taken from museum air confirmed that airborne spores were viable [62,63]. However, long-term temperature and humidity data, as well as simulations performed with WUFIplus and WUFIbio, indicated no risk of fungal growth [59]. The observed mycelial growth appears inconsistent with these predictions, suggesting that the situation is more complex and warrants further investigation [61].

In museums with diverse collections—especially those without mechanical ventilation—air is often perceived as stale due to the accumulation of odors. This may also apply to the Palace. The reduced air exchange rate, combined with the lack of mechanical ventilation, could contribute to poor air quality and the perception of unpleasant smells. Many studies recommend reducing air exchange rates. This strategy helps limit temperature and humidity fluctuations, which is crucial for preventive conservation [64]. Achieving the highest buffering effect requires buildings to be relatively airtight, with air exchange rates of ≤0.5 h−1. Under such conditions, the building can rely solely on natural ventilation [63,64]. Such conditions, however, are generally considered appropriate for storage facilities rather than spaces intended for public use [63].

7. Conclusions

This study investigated visitors’ perceptions of thermal conditions and indoor air quality in two historic museum buildings characterized by different microclimate-control strategies. By combining a pilot survey with long-term environmental data routinely collected for preventive conservation, the research aimed to explore how conservation-driven indoor conditions are perceived by users under real museum operating conditions.

The results indicate that subjective perceptions of both thermal conditions and indoor air quality may differ substantially between buildings, even when air temperature and relative humidity remain within moderate and stable ranges. In particular, the findings suggest that ventilation strategy, air freshness, odor accumulation, spatial configuration, and lighting conditions can play a significant role in shaping visitor experience. These factors may influence perceived environmental quality independently of the basic parameters typically monitored in museum practice.

From an energy and operational perspective, the study highlights the complexity of balancing conservation requirements with energy-conscious microclimate management in historic buildings open to the public. Strategies aimed at reducing energy demand—such as limiting mechanical ventilation or relying more strongly on passive control—may support conservation goals and climate-change mitigation but can simultaneously affect perceived indoor air quality and thermal sensations in exhibition spaces.

It should be emphasized that the present research was designed as an exploratory pilot study. Its objective was not to provide a comprehensive assessment of thermal comfort or indoor air quality, nor to evaluate compliance with comfort standards, but rather to identify recurring perception patterns and potential problem areas that may warrant further investigation. Despite its limitations, the study demonstrates the value of incorporating visitor perception into discussions of sustainable museum operation.

Future research should extend the survey campaign across different seasons, incorporate a broader range of environmental indicators, and further examine the interaction between conservation-driven climate control, energy performance, and human perception. Such an integrated approach may support the development of museum microclimate strategies that are both energy-efficient and responsive to visitor experience, without compromising the long-term protection of cultural heritage.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.S.-S.; methodology: A.S.-S.; formal analysis: A.S.-S., W.B. and K.M.; conducting a survey: W.B. and K.M.; data curation: A.S.-S., W.B. and K.M.; writing—original draft preparation: A.S.-S.; writing—review and editing: A.S.-S.; visualization: A.S.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. Data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical reasons.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the management of the National Museum in Krakow for making this research possible. They also thank Joanna Sobczyk, for her invaluable support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Schito, E.; Conti, P.; Testi, D. Multi-objective optimization of microclimate in museums for concurrent reduction of energy needs, visitors’ discomfort and artwork preservation risks. Appl. Energy 2018, 224, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, H.E.; Henriques, F.M.A. Energy efficiency in historic museums: The interplay between thermal rehabilitation, climate control strategies and regional climates. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Council of Museums (ICOM). ICOM Statutes; ICOM: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lucchi, E. Simplified assessment method for environmental and energy quality in museum buildings. Energy Build. 2016, 117, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camuffo, D. Microclimate for Cultural Heritage; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Camuffo, D.; Brimblecombe, P.; Van Grieken, R.; Busse, H.-J.; Sturaro, G.; Valentino, A.; Bernardi, A.; Blades, N.; Shooter, D.; De Bock, L.; et al. Indoor air quality at the Correr Museum, Venice, Italy. Sci. Total Environ. 1999, 235, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camuffo, D.; Van Grieken, R.; Busse, H.-J.; Sturaro, G.; Valentino, A.; Bernardi, A.; Blades, N.; Shooter, D.; Gysels, K.; Deutsch, F.; et al. Environmental monitoring in four European museums. Atmos. Environ. 2001, 35, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, D. Our environment ruined? Environmental control reconsidered as a strategy for conservation. J. Conserv. Mus. Stud. 1996, 1, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassar, M. Environmental Management: Guidelines for Museums and Galleries; Routledge: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlogeorgatos, G. Environmental parameters in museums. Build. Environ. 2003, 38, 1457–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdyn-Grygierek, J. HVAC control methods for drastically improved hygrothermal museum microclimates in warm season. Build. Environ. 2019, 149, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzarella, L. Energy retrofit of historic and existing buildings: The legislative and regulatory point of view. Build. Environ. 2015, 95, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisello, A.L.; Petrozzi, A.; Castaldo, V.L.; Cotana, F. On an innovative integrated technique for energy refurbishment of historical buildings. Appl. Energy 2014, 95, 1313–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Molina, A.; Boarin, P.; Tort-Ausina, I.; Vivancos, J.-L. Assessing visitors’ thermal comfort in historic museum buildings. Build. Environ. 2018, 132, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, K.; Pretelli, M. Heritage buildings and historic microclimate without HVAC technology: Malatestiana Library in Cesena, Italy. Energy Build. 2014, 76, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živković, V.; Džikić, V. Return to basics—Environmental management for museum collections and historic houses. Energy Build. 2015, 95, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratasz, Ł. Allowable microclimatic variations in museums and historic buildings: Reviewing guidelines in climate-for-collections standards. In Proceedings of the Postprints of the Munich Climate Conference, Munich, Germany, 7–9 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ascione, F. Energy saving strategies in air-conditioning for museums. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2009, 29, 676–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdyn-Grygierek, J. Indoor environment quality in the museum building and its effect on heating and cooling demand. Energy Build. 2014, 85, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascione, F.; De Rossi, F.; Vanoli, G.P. Energy retrofit of historical buildings: Theoretical and experimental investigations for modelling reliable performance scenarios. Energy Build. 2011, 43, 1925–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanger, P.O. Thermal Comfort; R.E. Krieger Publishing Company: Malabar, FL, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; Yu, H.; Mao, H.; Zhang, K.; Wang, M. Indoor thermal comfort and ageing: A systematic review. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 100, 111714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enescu, D. A review of thermal comfort models and indicators for indoor environments. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 79, 1353–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djamila, H. Indoor thermal comfort predictions: Selected issues and trends. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 74, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draganova, V.Y.; Yokose, H.; Tsuzuki, K.; Nabeshima, Y. Field study on nationality differences in adaptive thermal comfort. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.H.; Lee, K.H. The physical environment in museums and its effects on visitors’ satisfaction. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 963–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchi, E. Environmental risk management for museums in historic buildings: A case study of the Pinacoteca di Brera. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, R.; Schellen, L.; Schellen, H. Adaptive temperature limits for air-conditioned museums in temperate climates. Build. Res. Inf. 2017, 46, 686–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, H.S.; Altan, H. Museum indoor environments and their effect on human health, comfort, performance and productivity. In Proceedings of the SEEP 2014 Conference, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 23–25 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ankersmit, B.; Stappers, M.H.L. Managing Indoor Climate Risks in Museums; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shiner, J. Trends in microclimate control of museum display cases. In Museum Microclimates; Padfield, T., Borchersen, K., Eds.; National Museum of Denmark: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2007; pp. 267–275. [Google Scholar]

- Corgnati, S.P.; Fabi, V.; Filippi, M. A methodology for microclimatic quality evaluation in museums. Build. Environ. 2009, 44, 1253–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalski, S. Double the life for each five-degree drop. In Proceedings of the ICOM-CC 13th Triennial Meeting, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 22–27 September 2002; pp. 66–72. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, G. The Museum Environment; Butterworths: London, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- ICCROM. Teamwork for Preventive Conservation; ICCROM: Rome, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Michalski, S.; Grattan, D. Environmental Guidelines for Museums; Canadian Conservation Institute: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- ASHRAE. Museums, libraries and archives. In ASHRAE Handbook—HVAC Applications; ASHRAE: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2003; pp. 21.1–21.23. [Google Scholar]

- CEN. Conservation of Cultural Property—Specifications for Temperature and Relative Humidity (EN 15757); CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Baldan, M.; Manente, S.; Izzo, F.C. The role of bio-pollutants in the indoor air quality of old museum buildings: Artworks biodeterioration as preview of human diseases. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arar, M.; Jung, C. Analyzing the perception of indoor air quality among townhouse residents in Dubai. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Qu, M.; Sun, L.; Wang, X.; Yin, Y. IAQ and PAQ: A review and case analysis in China. Energy Built Environ. 2024, 5, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuang, G.W.; Kamaruzzaman, S.N.; Zulkifli, N. Occupants’ perception of indoor performance of historical museums. In Proceedings of the ICRSET 2014, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 21–22 March 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ferdyn-Grygierek, J.; Kaczmarczyk, J.; Blaszczok, M.; Lubina, P.; Koper, P.; Bulińska, A. Hygrothermal risk in museum buildings located in moderate climate. Energies 2020, 13, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadłowska-Sałęga, A.; Radoń, J.; Sobczyk, J.; Wąs, K. Influence of microclimate control scenarios on energy consumption in the Gallery of the 19th-Century Polish Art in the Sukiennice (the former Cloth Hall) of The National Museum in Krakow. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 415, 012026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnaggar, A.; Said, M.; Kraševec, I.; Said, A.; Grau-Bove, J.; Moubarak, H. Risk analysis for preventive conservation of heritage collections in Mediterranean museums: Case study of the museum of fine arts in Alexandria (Egypt). Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadłowska-Sałęga, A.; Sobczyk, J.; del Hoyo-Meléndez, J.M.; Wąs, K.; Radoń, J. Preservation Strategy and Optimization of the Microclimate Management System for the Chapel of the Holy Trinity in Lublin. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Energy Efficiency in Historic Buildings, Visby, Sweden, 26–27 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Battistel, L.; Vilardi, A.; Zampini, M.; Parin, R. An investigation on humans’ sensitivity to environmental temperature. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Li, B.; Liu, H.; Yang, D.; Yu, W.; Liao, J.; Huang, Z.; Xia, K. The Response of Human Thermal Sensation and Its Prediction to Temperature Step-Change (Cool-Neutral-Cool). PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobas, B.; Koth, S.C.; Nkurikiyeyezu, K.; Giannakakis, G.; Auer, T. Effect of Exposure Time on Thermal Behaviour: A Psychophysiological Approach. Signals 2021, 2, 863–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Foged, I.W.; Moeslund, T.B. Clothing insulation rate and metabolic rate estimation for individual thermal comfort assessment in real life. Sensors 2022, 22, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowkar, M.; de Dear, R.; Brusey, J. Influence of long-term thermal history on comfort and preference. Build. Environ. 2020, 168, 106491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, A.; Kayaci, N.; Kanbur, B.B.; Demir, H. Experimental Investigation of Mean Radiant Temperature Trends for a Ground Source Heat Pump-Integrated Radiant Wall and Ceiling Heating System. Buildings 2023, 13, 2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmár, F. Interrelation between mean radiant temperature and room geometry. Energy Build. 2012, 55, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- te Kulve, M.; Schlangen, L.; van Marken Lichtenbelt, W. Interactions between perception of light and temperature. Indoor Air 2018, 28, 881–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, C.; Luo, L.; Liu, W. Effects of increased humidity on physiological responses, thermal comfort, perceived air quality, and Sick Building Syndrome symptoms at elevated indoor temperatures for subjects in a hot-humid climate. Indoor Air 2021, 31, 524–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsutsumi, H.; Tanabe, S.; Harigaya, J.; Iguchi, Y.; Nakamura, G. Effect of humidity on human comfort and productivity after step changes from warm and humid environment. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 4034–4042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Mimi, H.H. Assessment of indoor air quality level and sick building syndrome according to the ages of building in Universiti Teknologi Malaysia. J. Technol. 2015, 76, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, M.E.; Jalaludin, J.; Shaharom, N. Indoor Air Quality and Prevalence of Sick Building Syndrome Among Office Workers in Two Different Offices in Selangor. Am. J. Appl. Sci. 2013, 10, 1140–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobczyk, J. Verification of Methods for Analysis of Microclimate in Historic Museum Buildings. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Agriculture in Krakow, Krakow, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mallo, A.C.; Elíades, L.A.; Nitiu, D.S.; Saparrat, M.C.N. Fungal monitoring of the indoor air of the Museo de La Plata Herbarium, Argentina. Rev. Iberoam. De Micol. 2017, 34, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsivela, E.; Raisi, L.; Lazaridis, M. Viable airborne and deposited microorganisms inside the historical Museum of Crete. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2021, 21, 200527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strebel, M. Passive Climate Control: How Air Conditioning in the Storage Rooms of Archives, Libraries and Museums can be Replaced with Passive Systems. J. Conserv. Sci. 2012, 13, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryhl-Svendsen, M. The role of air exchange rate and surface reaction rates on the air quality in museum storage buildings. In Museum Microclimates; National Museum of Denmark: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Padfield, T. Potential and limits of passive air conditioning in museums and archives. In Museum Microclimates; National Museum of Denmark: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2007. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.