Abstract

HVAC (Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning) system in buildings is a major component of energy consumption, and realizing high-precision energy consumption prediction is of great significance for intelligent building management. Aiming at the problems of insufficient modeling ability of nonlinear features and insufficient portrayal of long time-series dependencies in prediction methods, this paper proposes an HVAC energy consumption prediction model that combines time-sequence convolutional network (TCN), bi-directional gated recurrent unit (BiGRU), and Attention mechanism. The model takes advantage of TCN’s parallel computing and multi-scale feature extraction, BiGRU’s bidirectional temporal dependency modeling, and Attention’s weight assignment of key features to effectively improve the prediction accuracy. In this work, the HVAC load is represented by the building-level electricity meter readings of office buildings equipped with centralized, electrically driven heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning systems. Therefore, the proposed method is mainly applicable to building-level HVAC energy consumption prediction scenarios where aggregated hourly electricity or cooling energy measurements are available, rather than to the control of individual terminal units. The experimental results show that the model in this paper achieves better performance compared to the method on ASHRAE dataset, the proposed model outperforms the baseline by 2.3%, 22.2%, and 34.7% in terms of MAE, RMSE, and MAPE, respectively, on the one-year time-by-time data of the office building, and meanwhile it is significant 54.1% on the MSE metrics.

1. Introduction

As the optimization of the global energy structure and the achievement of carbon-neutrality targets become increasingly urgent, the issue of building energy consumption has gradually become a core topic in smart city and green strategy. According to statistics, the energy consumption in the operation phase of a building accounts for about 30% to 40% of the total energy consumption, of which the proportion of energy consumption of the heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) system, as the key equipment for temperature regulation in the building, usually exceeds 50%. According to statistics, the operational phase of buildings accounts for approximately 30–40% of global final energy consumption, and HVAC systems commonly consume 30–40% or even more of the total building energy use [1,2,3]. Therefore, improving the accuracy of HVAC energy consumption prediction is crucial for enhancing building energy efficiency and supporting low-carbon operation strategies.

Therefore, how to achieve accurate modeling and prediction of HVAC system energy consumption is not only a key means to improve energy efficiency and operating costs, but also provides technical support for building intelligence and low-carbon operation.

Energy consumption prediction methods mainly include rule-based engineering models, Linear Regression (LR) [4], time series models (e.g., ARIMA) [5], and machine learning methods such as Support Vector Machines (SVMs) [6] and Random Forests [7]. These models have certain advantages in dealing with linear, univariate, and low-dimensional energy consumption data scenarios, but in the face of the highly nonlinear, multi-source heterogeneous, and strongly time-series-dependent characteristics that exist in real building systems, the models are often difficult to accurately capture the deep-seated laws, and the prediction results are biased and unstable. In-depth study of its characteristics can be understood, which is highly nonlinear from the equipment power law–saturation–step cascade, multi-source heterogeneity from the weather–structure–equipment–people–network of five heterogeneous spatial and temporal scales, strong timing dependence on the thermal inertia of the building, the state of the equipment memory and the personnel feed-forward together, and these three characteristics are not a flaw in the data, but rather a true depiction of the physical operation of the law of the HVAC, but also on the modeling structure. Therefore, it is necessary to introduce deep learning methods with strong feature expression and time-sequence modeling capabilities to improve prediction accuracy and generalization ability.

A number of studies have investigated building and HVAC energy consumption prediction from different perspectives. Zhao and Magoulès [8] provided a comprehensive review of building energy consumption prediction methods, covering engineering, statistical, and artificial intelligence-based models. More recently, Ciampi et al. [9] applied Bayesian Networks to industrial HVAC systems and demonstrated that probabilistic graphical models can effectively capture the complex dependencies between operating conditions and energy use. These works highlight both the importance and the difficulty of accurate HVAC energy prediction, especially under nonlinear and multi-factor coupling effects.

More recently, a variety of deep learning-based approaches have been proposed for building and HVAC energy prediction. For example, Wan et al. [10] developed a least-squares support vector machine-based framework for HVAC energy consumption prediction and demonstrated that nonlinear kernel methods can effectively handle multi-factor coupling effects. Liu et al. [11] proposed a dynamic prediction method for HVAC systems operating under different modes and seasons, highlighting the importance of capturing complex temporal patterns and mode transitions. Pan et al. [12] introduced a probabilistic HVAC load forecasting method based on TCN, showing that temporal convolutional architectures can effectively model long-term dependencies in HVAC load series. In addition, Chen et al. [13] presented a systematic review of building energy consumption prediction methods using artificial intelligence techniques, summarizing the current trends and challenges in this field.

In recent years, as deep learning has made breakthroughs in areas such as image, and natural language processing, its application in building energy prediction has become increasingly widespread. Typical Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) [14], Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) [15], Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) [16], Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) [17,18,19] and other structures have been widely used in energy consumption prediction tasks, showing good nonlinear modeling capabilities and the ability to capture temporal information. Chae et al. [20] developed an LSTM-based model for forecasting sub-hourly electricity usage in commercial buildings, and reported that the LSTM reduced the RMSE from 0.27 to 0.19 compared with SVR, corresponding to a performance improvement of approximately 29.63%; Zhao et al. [18] proposed a GRU-based approach for short-term heating load prediction. Their experimental results showed that the GRU model reduced the MAPE from 28.33% to 17.34% compared with traditional methods, and explicitly captured the cyclical variations between weekdays, weekends and holidays. Wan et al. [10] developed a least-squares support vector machine-based framework for HVAC energy consumption prediction and demonstrated that nonlinear kernel methods can effectively handle multi-factor coupling effects.

However, this type of network structure still suffers from two shortcomings: on the one hand, its unidirectional structure makes it difficult to fully utilize the complete contextual information, which restricts the model from modeling the alignment of historical and future information; on the other hand, its sequential processing restricts the efficiency of the training and the flexibility of the scaling of the modeling.

To overcome the above problems, scholars have tried to introduce more expressive and flexible model structures in recent years, such as Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN) [21] and Attention [22]. For temporal convolutional networks, previous studies have demonstrated that TCN can achieve lower prediction errors with fewer training epochs than RNN/LSTM models, e.g., reducing RMSE by about 20% while shortening the training time by 40% in time-series forecasting tasks [21,23]. Liu et al. [11] proposed a dynamic prediction method for HVAC systems operating under different modes and seasons, highlighting the importance of capturing complex temporal patterns and mode transitions. Pan et al. [12] introduced a probabilistic HVAC load forecasting method based on TCN, showing that temporal convolutional architectures can effectively model long-term dependencies in HVAC load series. In addition, Chen et al. [13] presented a systematic review of building energy consumption prediction methods using artificial intelligence techniques, summarizing the current trends and challenges in this field.

In real building operations, HVAC energy consumption exhibits complex temporal patterns, such as daily and weekly cycles, as well as slow seasonal trends, even when the data are sampled at an hourly resolution. Capturing such multi-scale temporal dependencies within a single time series is therefore a key challenge for accurate HVAC energy consumption prediction.

Although the above studies have significantly advanced HVAC and building energy consumption prediction, several limitations remain. First, many existing works focus on either purely statistical models or single deep learning architectures, which may struggle to simultaneously capture multi-scale temporal dependencies, bidirectional contextual information, and key time slices with large load changes. Second, a large portion of the literature evaluates the models on a limited number of buildings or in short-term test periods, and the cross-building generalization capability is still insufficiently explored. Third, the interpretability of deep learning models for HVAC load forecasting, especially regarding the contribution of different time steps and exogenous features, is often not explicitly analyzed. These limitations motivate the development of hybrid deep learning architectures that can integrate complementary temporal modeling modules and provide more interpretable predictions for building-level HVAC energy consumption.

To address these gaps, this paper proposes a hybrid TCN-BiGRU-Attention model that integrates three complementary temporal modeling components within a single framework, and performs a comprehensive evaluation on the ASHRAE public dataset, including ablation experiments, attention-based interpretability analysis, cross-building generalization tests, and comparisons with both deep-learning and non-deep-learning baselines. The model synthesizes the structural advantages of the three types of sub-modules and possesses several significant features as follows:

- (1)

- The convolutional structure of TCN is utilized to extend the sensory field without network depth and extract local to global temporal features, which enhances the ability of multi-scale temporal feature modeling;

- (2)

- Introducing BiGRU to construct bi-directional temporal dependencies, which enhances the model’s joint perception of trends and short-term fluctuations, and enhances the comprehensive modeling capability of contextual information;

- (3)

- Introducing the attention mechanism to identify key moments in energy consumption (e.g., equipment start/stop, drastic climate change, etc.), realizing weighted modeling of key time slices, and enhancing the ability of focusing on key time slices;

- (4)

- Modularized design facilitates deployment and iteration, and provides a certain degree of interpretability through Attention weighting analysis, which helps engineering landing application and improves scalability and interpretability.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the related work on HVAC and building energy consumption prediction. Section 3 presents the architecture and key components of the proposed TCN-BiGRU-Attention model. Section 4 describes the dataset, feature engineering steps, and evaluation setup. Section 5 reports and discusses the model performance, ablation studies, sensitivity analysis, and cross-building generalization results. Finally, Section 6 summarizes the main findings, discusses the limitations of this study, and outlines directions for future work and practical deployment.

2. Related Works

2.1. Application of TCN in Temporal Modeling

Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN) is a temporal modeling method based on convolutional structure, proposed by W Zhao et al. (2019) [24], for replacing RNN-like models. Its core includes the following structural design points:

- (1)

- Convolution (Dilated Convolution): by exponentially increasing the dilation rate, TCN is able to capture long-distance dependencies with limited convolutional layer depth;

- (2)

- Causal Convolution (Causal Convolution): to ensure that the current output is only related to the historical information to avoid future information leakage;

- (3)

- Residual Block: to alleviate the problem of gradient disappearance in deep networks and improve training stability.

It can be seen that TCN has parallel computing capability, faster training speed compared to RNN/LSTM, and can model dependence, has a stronger sense of the wild than GRU under a certain number of layers, and has good local feature extraction capability in the convolutional kernel structure to take into account the trend and fluctuations.

In energy prediction, TCN has been used for tasks such as wind power prediction, load decomposition, and HVAC energy modeling. SK Gautam et al. (2025) [23] achieved short- and medium-term prediction of building electrical loads based on a TCN model, which significantly improved robustness and prediction accuracy.

2.2. Advantages of BiGRU in Bidirectional Sequence Modeling

GRU is a recurrent neural network that is more concise and computationally efficient than LSTM structure, which uses two gating mechanisms (reset gate and update gate) to control the information flow. BiGRU, i.e., bi-directional GRU structure, is capable of learning context dependencies in sequences in both forward and backward directions, which is suitable for tasks that have dependencies on both the future and the history.

Compared with unidirectional GRU, BiGRU has a more comprehensive context modeling capability, improves the perception of turning points and cycle boundaries, and facilitates the model to consistently model trend changes and abrupt time points, and at the same time, performs more stably in small-sample or long-duration dependency tasks.

In recent years, BiGRU has been widely used in air prediction, building temperature control curve regression, etc., proving its reliability in time series regression.

2.3. Attention Mechanism and Its Introduction Value in Energy Consumption Prediction

Attention mechanism (Attention) proposed by A Vaswani et al. (2017) [25] for neural machine translation task. This mechanism achieves selective modeling of input information by calculating the importance weights of each part of the input sequence to the current task goal. The core idea is “resource focusing”, instead of processing all time steps equally, computational resources should be concentrated on more critical parts.

In energy consumption prediction, the introduction of Attention mechanism brings three benefits. First, it can automatically identify the intervals with large changes in energy consumption during key time periods such as peak hours and equipment start/stop hours; second, it can visualize the time weights and assist in the analysis of the causes of energy consumption, which enhances the interpretability of the model; and third, it has a certain filtering capability for anomalies and non-critical data, which improves the robustness of the prediction.

At present, Attention mechanism has been integrated into a variety of structures, such as Seq2Seq+Attention [26], TCN-Attention [27], Informer [28], etc., which are widely used in short-term load forecasting, smart grid scheduling, air conditioning system control and other tasks.

To provide a clearer comparison of representative HVAC and building energy prediction methods, Table 1 summarizes several typical models, their main characteristics, and limitations.

Table 1.

Summary of representative HVAC and building energy consumption prediction models.

As shown in Table 1, previous studies have extensively explored LSTM/GRU, SVM-based models, probabilistic graphical models, and TCN-based architectures for HVAC and building energy prediction. However, only a few works attempt to jointly integrate multi-scale temporal convolutions, bidirectional recurrent modeling and attention mechanisms, or to systematically evaluate hybrid models on publicly available datasets with cross-building validation. These observations further motivate the hybrid TCN-BiGRU-Attention framework proposed in this paper.

2.4. Summary

Recent reviews and application studies on building and HVAC energy prediction [8,9] further confirm that there is still room for improvement in terms of modeling nonlinear dynamics, temporal dependencies, and cross-feature interactions.

In summary, existing studies have explored multiple deep time-series modeling for HVAC energy consumption prediction. However, it is usually difficult for a single model structure to simultaneously meet the following three requirements: (i) multi-scale time-series modeling capability; (ii) context modeling capability; and (iii) time-slice criticality identification capability.

The multi-module structure introduced in this paper, which integrates TCN, BiGRU and Attention mechanism, is precisely an integrated innovation based on fully absorbing the advantages of the above three types of methods, which has stronger representation capability and practical value.

3. Research Methods

3.1. Overall Structure of the Model

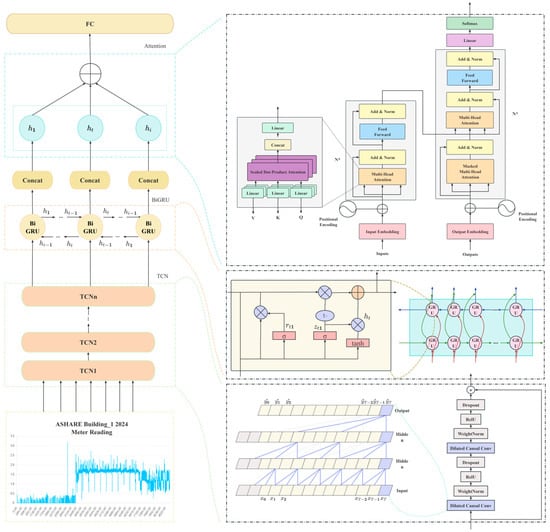

As shown in Figure 1, the HVAC energy consumption prediction model proposed in this paper adopts a hybrid deep neural network structure consisting of a temporal convolutional network (TCN), a bidirectional gated recurrent unit (BiGRU), and an attention mechanism (Attention). The model aims to synthesize the multi-scale modeling capability, temporal context-awareness capability, and critical moment focusing capability in order to enhance the modeling accuracy and generalization capability for building energy consumption.

Figure 1.

Overall architecture of the proposed TCN-BiGRU-Attention model for building-level HVAC energy consumption prediction.

The input to the model is a multivariate time series window , which contains the past L = 168 h of HVAC meter readings and related exogenous variables (e.g., air temperature, wind speed, and time features). First, the TCN module maps into a high-dimensional temporal representation by stacking several dilated causal convolutional layers, thereby enlarging the receptive field and capturing multi-scale temporal patterns. Then, is fed into a bidirectional GRU module to learn forward and backward temporal dependencies and produce a contextual hidden sequence . The additive Attention module computes the importance weights of each time step based on , aggregates them into a context vector, and finally a fully connected layer outputs the P = 24-step ahead HVAC energy consumption forecast .

Compared with single-model approaches (pure TCN, pure GRU, or TCN-GRU hybrids), the proposed TCN-BiGRU-Attention architecture is deliberately designed to integrate three complementary capabilities within a unified framework. Specifically, TCN focuses on multi-scale temporal feature extraction through dilated convolutions, BiGRU enhances the representation of bidirectional contextual dynamics, and the Attention mechanism provides a flexible way to emphasize those time steps that are most informative for future load prediction. This design increases the model complexity to some extent, but it also enables the model to better capture the heterogeneous temporal patterns and nonlinear interactions present in HVAC energy consumption. As shown in Section 5, this additional complexity is justified by consistent and significant performance gains over simpler models.

3.2. Input Design

(1) Let the current time be and the forecast target be the HVAC load in the next 24 h, (, , …, ), and input sequence is

where L denotes the length of the input history window; d denotes the feature dimension at each time step.

By stacking dilated convolutions with different receptive fields, the TCN module is able to capture short-term fluctuations (e.g., hourly variations) and longer-term cycles (e.g., daily and weekly patterns) simultaneously, which corresponds to different temporal scales in HVAC operation.

(2) The TCN module realizes long-range perception of historical information through convolution, and its core operation is

where is the temporal input sequence in the above, i.e., is the convolutional output; is the convolutional kernel size; is the coefficients, which are usually incremented by a power of 2; and is the convolutional kernel weight.

In addition, a form of Residual Connection (RC) is used in the TCN structure to enhance the stability of the deep structure:

By stacking multiple convolutional layers, the model can acquire a large sense of wildness while avoiding information leakage.

(3) BiGRU module, after obtaining the TCN output, enters the BiGRU module in order to model the contextual dynamic dependencies in the sequence. The core structure of the GRU consists of two gating mechanisms: the Reset Gate and the Update Gate:

The state update formula is

The bi-directional GRU structure extracts hidden states from both the forward and backward directions, and the final output is a splice in both directions:

where is the input vector at the current moment, i.e., the output obtained by TCN; is the hidden state at the previous moment; is the update gate vector, which controls the retention ratio of the previous state; rt is the reset gate vector, which controls the degree of the influence of the previous state on the candidate state; , denotes the weight matrix of the input gates; and, denotes the cyclic weight matrix of the hidden gates. This mechanism improves the perception of trends and sudden changes.

The BiGRU and Attention modules further complement TCN by enhancing context modeling and selectively emphasizing critical time slices, respectively, so that the overall architecture forms a multi-component, multi-scale temporal modeling pipeline.

(4) Attention module, in order to further improve the model’s ability to recognize key time segments (such as energy-saving control points, extreme weather moments, etc.), the additive attention mechanism is introduced. The specific process is as follows:

Calculate the attention score:

Normalized to probability weights:

Generate a weighted representation:

This mechanism dynamically influences the proportion of each time step on the final prediction, realizing data-driven temporal attention allocation.

(5) Fully connected layer and output, the weighted context vector output by the Attention module is passed into the fully connected layer and the predicted values are output using a linear activation function:

For multi-step prediction problems (e.g., 24 h in the future), the output dimension can be extended to

where is the prediction step.

4. Modelling and Evaluation

The TCN-BiGRU-Attention model proposed in this paper was tested under a unified platform, and a systematic experimental procedure was designed, including data source and preprocessing, feature construction, experimental parameter setting, and comparison model selection. It is found to be highly effective in the task of predicting energy consumption of HVAC systems, and multiple independent runs are performed to ensure the reproducibility and comparability of the results.

4.1. Dataset Source

The modelling and evaluation in this paper are based on the building energy consumption dataset published by the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE). This dataset includes energy consumption data of HVAC systems from multiple commercial buildings across various climate zones, along with corresponding environmental, equipment, and temporal information.

According to the dataset description, the analyzed buildings are commercial facilities equipped with centralized, electrically driven HVAC systems (e.g., chillers, pumps, air-handling units, and ventilation fans). The publicly released ASHRAE dataset provides aggregated meter readings at the building level and does not disclose detailed device-level specifications such as manufacturer, rated capacity, or control strategy. Consequently, the proposed model targets building-level HVAC energy consumption prediction for such centralized systems, rather than the performance of individual air-conditioning units.

In this study, two office buildings from the ASHRAE dataset are selected and denoted as Building 1 (B1) and Building 2 (B2):

- (1)

- Building 1 (B1) is used for model development, including training, validation, and primary testing. It is an office building located in a temperate climate region and equipped with a centralized, electrically driven HVAC system. Unless otherwise specified, all model comparisons in Section 4 and Section 5 are conducted on B1.

- (2)

- Building 2 (B2) is another office building with different floor area and climatic conditions. It is reserved for cross-building generalization experiments in Section 5.5, where the model trained on B1 is directly applied to B2 without retraining.

Throughout this paper, we consistently use the notation “Building 1 (B1)” and “Building 2 (B2)” to avoid ambiguity.

To avoid information leakage, the dataset was split chronologically rather than randomly. For B1, the first 70% of the hourly records in the 12-month period were used as the training set, the subsequent 10% as the validation set for hyperparameter tuning and early stopping, and the final 20% as the test set for performance evaluation. The same chronological splitting strategy was adopted for Building-2 in the generalization experiment.

In particular, this study uses the publicly available “ASHRAE—Great Energy Predictor III” dataset released by the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers on the Kaggle platform [29].

Each building contains approximately 8784 annual data records (365 × 24), resulting in hundreds of thousands of samples in total. In this study, a representative building (denoted as Building-1) was selected as the primary experimental subject. All data were standardized, cleaned, and preprocessed to ensure the stability and consistency of the input features.

In the official metadata of the ASHRAE dataset, the building selected as Building-1 in this study is labeled as an office building located in a temperate climate region. The building is served by a centralized HVAC system and is representative of medium-to-large commercial office buildings. For the cross-building generalization experiment in Section 5.5, Building-2 is another office building with different floor area and climatic conditions. The dataset anonymizes the exact geographical locations and detailed architectural characteristics for privacy reasons; therefore, this study focuses on the building type (office) and climatic context rather than on specific addresses.

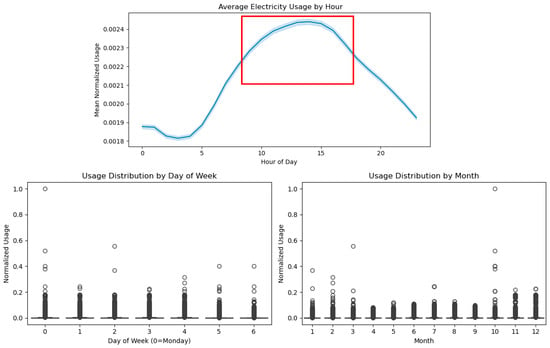

As shown in Figure 2, the dataset records electricity consumption readings over a continuous 12-month period, exhibiting a clear seasonal pattern. During the late spring to autumn months (from late May to October), electricity consumption significantly increases.

Figure 2.

Annual HVAC energy consumption profiles of B1 and B2 from the ASHRAE dataset. The plots illustrate the seasonal variations and typical daily patterns observed in the two office buildings. The red box highlights the data segment that is affected by seasonal factors, showing a noticeable increase in summer.

The data were sampled on an hourly basis over 12 consecutive months. As illustrated in Figure 3, after normalization, the data reveal the daily, weekly, and monthly electricity consumption of the HVAC system. The peak consumption period occurs between 10:00 and 19:00 each day.

Figure 3.

Electricity consumption data. The red box highlights the data segment that is affected by human activity, with the values increasing noticeably at noon and in the afternoon.

Additionally, the dataset includes meteorological and climatic attributes such as temperature and wind speed. As depicted in Figure 4, the statistical relationship between electricity consumption and climatic factors shows that energy usage peaks when the ambient temperature ranges between 20 °C and 30 °C, and similarly, when the wind speed is within levels 3 to 6 (on the Beaufort scale).

Figure 4.

Normalized Air Temperature and Wind Speed Data. The red box highlights the data segment that is affected by temperature and wind speed.

4.2. Data Preprocessing and Feature Construction

To enhance the model’s learning performance and generalization capability, the following preprocessing steps were applied to the raw data:

- (1)

- Handling Missing Values

For the missing meteorological and meter data, linear interpolation and forward fill methods were employed.

Outliers were handled using the 3σ (three-sigma) rule for truncation, with the following value range limits applied:

where μ and σ represent the mean and standard deviation of the corresponding feature, respectively.

- (2)

- Temporal Feature Extraction

To capture the temporal periodic structure, the following time-based features were extracted from the timestamp:

Hour ∈{0, 1, …, 23}, Day of the week ∈{0, 1, …, 6}, holiday (binary: 0/1)

where both the hour and day of the week were encoded cyclically using sine-cosine functions, constructing continuous features as follows:

- (3)

- Feature Normalization

All continuous numerical features were standardized using Z-score normalization to eliminate dimensionality effects:

where μ and σ are the mean and standard deviation computed from the training dataset.

- (4)

- Input-Output Window Setup

The input sequence consists of the feature set from the past T = 168 h (i.e., 7 days), and the prediction target is the HVAC energy consumption for the next P = 24 h.

The input-output format is as follows:

where and represent the feature and target values, respectively, for each time step.

In summary, the input feature vector at each time step consists of the following attributes:

- (1)

- meter_reading_norm: normalized electricity consumption of the HVAC system;

- (2)

- air_temperature (°C);

- (3)

- wind_speed (m/s);

- (4)

- Hour_sin and Hour_cos: sine–cosine encodings of the hour of day;

- (5)

- Week_sin and Week_cos: sine–cosine encodings of the day of week;

- (6)

- holiday: binary indicator (0/1) denoting whether the current time falls on a weekend or public holiday.

These attributes are used consistently in all models and experiments described in this paper.

4.3. Model Parameter Settings

During the experimental process, the main model parameters and their configurations were set in Table 2.

Table 2.

Parameter and value/setting.

To prevent model overfitting, an early stopping mechanism was introduced during training (Patience = 7). Specifically, training was terminated if the validation loss did not decrease for seven consecutive epochs.

All models in this study were implemented in Python 3.10 using the PyTorch 2.1 deep learning framework. The experiments were conducted on a workstation equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 3080 GPU (10 GB memory; NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA), an Intel Core i7-12700 CPU (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and 32 GB of RAM, running the Windows 11 operating system (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). The optimization was performed using the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 1 × 10−3 and a batch size of 64, unless otherwise specified.

To ensure fair comparison, all baseline models were implemented within the same framework and trained using the same training–validation–test splits and early stopping strategy. The main code structure follows an open-source implementation for time-series forecasting, and can be made available upon request to facilitate reproducibility.

4.4. Comparison of Models

To verify the effectiveness of the model, several commonly used forecasting models were selected as baseline models for comparison.

In addition to the deep learning baselines, we also implemented two classical machine-learning models—multiple linear regression (LR) and random forest regression (RF)—as non-deep-learning benchmarks. Both models use the same input features and training/validation splits as the proposed method.

As observed in Table 3, each model was trained and tested on the same input features and sequence lengths to ensure a fair comparison. The Transformer model and other architectures were implemented based on publicly available implementations, and the input format was adjusted to match the format of the data in this study.

Table 3.

Comparison Model Configuration.

4.5. Evaluation Metrics

This paper uses the following four standard metrics to evaluate the forecasting performance:

Mean Absolute Error (MAE):

Mean Squared Error (MSE):

Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE):

Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE):

where denotes the actual energy consumption, represents the predicted value, and N is the number of samples. MAE reflects the overall magnitude of prediction errors, while MSE and RMSE are more sensitive to outliers and thus better suited for evaluating model robustness. MAPE measures the average percentage deviation of predictions from the actual values, providing an interpretable indicator of relative prediction accuracy.

5. Results and Discussion

To comprehensively evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed model in HVAC energy consumption forecasting, this section presents a multi-perspective discussion covering model performance, ablation study analysis, attention visualization, sensitivity analysis, and generalization testing.

5.1. Model Performance Results

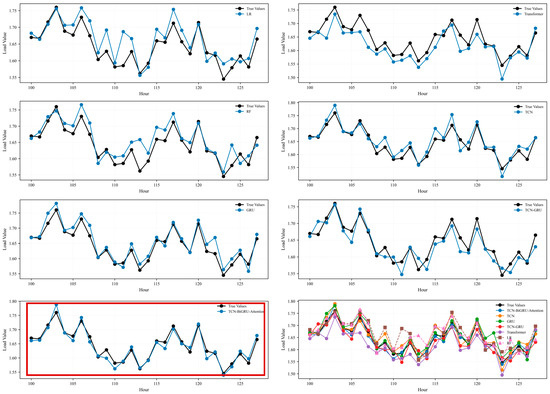

Using the ASHRAE B1 dataset, the proposed model and seven comparative models were trained and tested under identical model evaluation settings.

As shown in Figure 5, the prediction curve of the TCN-BiGRU-Attention model aligns more closely with the actual energy consumption curve. Compared with single or simpler hybrid models such as TCN, BiGRU, and TCN-BiGRU, the proposed architecture effectively integrates the advantages of each component. It achieves synergistic effects in temporal feature extraction, bidirectional information utilization, and key information focusing. Consequently, the proposed model demonstrates superior accuracy and stability in energy forecasting tasks, providing a promising architecture reference for deep learning–based energy prediction research.

Figure 5.

Comparison between the actual HVAC energy consumption and the predictions of different models for a representative one-week period in B1. The red box highlights the experimental results obtained in this study.

The evaluation results are summarized as Table 4.

Table 4.

Quantitative comparison of prediction performance for different models on B1 in terms of MAE, RMSE, MSE, and MAPE. The best results for each metric are highlighted in bold.

As observed in Table 4, the proposed model outperforms mainstream deep learning models across all evaluation metrics. Compared with the Transformer model, the TCN-BiGRU-Attention model achieves reductions of 2.3% in MAE, 22.2% in RMSE, and 34.7% in MAPE, while the MSE is significantly reduced by 54.1%.

Given that MSE is more sensitive to outliers, these results indicate that the proposed model exhibits stronger robustness in mitigating large prediction deviations.

Computational Cost Comparison

In addition to predictive accuracy, computational efficiency is also an important factor for practical deployment. Table 5 is therefore extended with the average training time per epoch and the inference time per 1000 prediction windows for each model, measured on the same hardware platform (GPU configuration).

Table 5.

Computational cost of different models.

Table 5 summarizes the computational costs of different models for HVAC load forecasting and shows that these costs are consistent with their structural characteristics, while highlighting the favorable accuracy–efficiency trade-off of the proposed TCN-BiGRU-Attention model. Linear Regression (LR) achieves the highest efficiency (4.2 s/epoch training, 8.7 ms per thousand windows inference) due to its minimal parameter size and simple linear operations, and thus serves as an efficient baseline. Random Forest (RF) requires more training time (18.5 s/epoch) because multiple decision trees must be constructed, yet it still avoids the higher complexity of attention-based architectures. Overall, the computational cost follows the clear pattern LR < TCN < GRU < TCN-GRU < TCN-BiGRU-Attention < RF < Transformer, which aligns with the common hierarchy from linear to complex attention-based models. Although TCN-BiGRU-Attention slightly increases training time compared with single TCN/GRU, it maintains acceptable inference latency (25.3 ms per thousand windows) and achieves a 22.2% RMSE and 54.1% MSE reduction relative to the Transformer, while LR shows over 40% higher RMSE and RF yields moderate accuracy with higher cost, confirming the practical deployment advantages of TCN-BiGRU-Attention for HVAC load forecasting.

From a physical and operational perspective, the superiority of the TCN-BiGRU-Attention model can be interpreted as follows. The TCN module effectively captures daily and weekly cycles, as well as smoother seasonal trends, which correspond to typical operation schedules and outdoor weather variations. The BiGRU module exploits bidirectional information to better represent the gradual ramp-up and ramp-down behaviors before and after peak periods. The Attention mechanism highlights those time steps that are most informative for forecasting upcoming loads, such as morning start-up hours and midday peaks. This combination allows the model to produce forecasts that are not only numerically more accurate but also more consistent with HVAC operation patterns observed in practice.

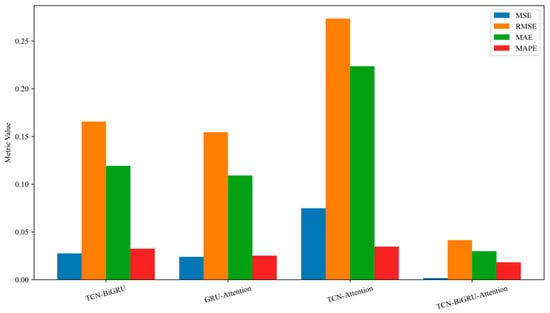

5.2. Ablation Study Analysis

As shown in Figure 6, removing any individual module leads to degraded performance, indicating that the TCN, BiGRU, and Attention modules work collaboratively in temporal modeling. Notably, the introduction of the Attention mechanism substantially enhances the model’s responsiveness to key temporal moments, as depicted in Figure 7.

Figure 6.

Ablation experiment diagram.

Figure 7.

Ablation evaluation index chart.

To further validate the effectiveness of each submodule, four variant models were designed for ablation experiments, as summarized below Table 6:

Table 6.

Ablation Study results.

Ablation experiments were conducted to verify the contributions of key components (Attention mechanism, BiGRU module, TCN module) in the TCN-BiGRU-Attention model, with performance evaluated by MAE, MSE, RMSE, and MAPE.

The results show that when the Attention mechanism is removed (No-Attention), the MAE increases to 0.1192, MSE to 0.0275, RMSE to 0.1657, and MAPE to 0.0325. The significant rise in error indicators indicates that the Attention mechanism can effectively capture long-range dependencies of sequence features and improve prediction accuracy. When the BiGRU module is removed (No-BiGRU), MAE, MSE, and RMSE surge to 0.2236, 0.0748, and 0.2735 respectively, with MAPE at 0.0346. The most severe error deterioration confirms the irreplaceable role of BiGRU in modeling temporal information of sequences. When the TCN module is removed (No-TCN), MAE is 0.1091, MSE is 0.0239, RMSE is 0.1546, and MAPE is 0.0252. Although it outperforms No-Attention and No-BiGRU, it is still much worse than the complete model, demonstrating the critical value of TCN in local feature extraction.

In contrast, the complete TCN-BiGRU-Attention model achieves MAE of 0.0299, MSE of 0.0414, RMSE as low as 0.0017, and MAPE of 0.0182. All indicators are significantly better than those of the ablated models, fully verifying the synergistic advantages of the integration of TCN, BiGRU, and the Attention mechanism. This proves that the model architecture has efficient feature extraction and temporal modeling capabilities in sequence prediction tasks.

From the ablation study, it can be seen that each submodule—TCN, BiGRU, and Attention—plays a distinct and complementary role. TCN mainly contributes to multi-scale temporal feature extraction, BiGRU enhances bidirectional context modeling, and Attention focuses the model on key time slices with large load changes. The complete TCN-BiGRU-Attention model therefore integrates these three capabilities and achieves the best overall performance, which directly supports the effectiveness of the proposed combination.

5.3. Attention Visualization Analysis

To verify the interpretability of the attention mechanism, a random 24-h input sequence was selected, and the corresponding attention weights were visualized, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Attention visualization.

Figure 8 reveals that the model assigns higher attention weights to the preceding 1–2 h and to typical HVAC operation peaks (e.g., around 8:00 AM and 1:00 PM). This demonstrates that the model effectively captures critical time segments corresponding to HVAC activity patterns.

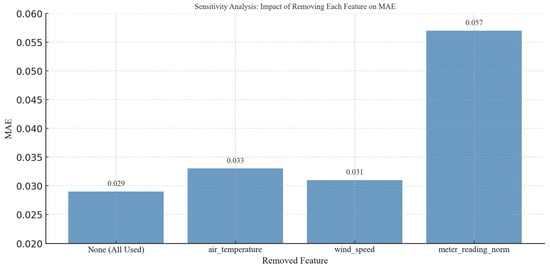

5.4. Sensitivity Analysis

To evaluate the influence of individual input features on model performance, a sensitivity analysis was conducted. Specifically, while keeping the model architecture and parameters unchanged, each input feature was removed in turn, and performance metrics on the test set were recorded. The comparative results quantify the relative importance of each feature.

As shown in Figure 9, the model achieves the lowest error (MAE = 0.0299) when all features are included. Removing air_temperature or wind_speed results in performance degradation, with air_temperature removal increasing MAE to 0.0334, indicating its substantial contribution to prediction accuracy. Excluding meter_reading_norm (i.e., historical target values) causes a sharp performance drop (MAE = 0.0574), confirming its critical role as a predictive feature.

Figure 9.

Sensitivity Analysis.

In addition to feature-level sensitivity, it is also important to consider the measurement uncertainty of the underlying sensors. The ASHRAE dataset does not explicitly provide detailed accuracy specifications for individual meters and environmental sensors. However, typical commercial-grade electricity meters and temperature sensors used in building energy monitoring often have accuracy levels within ±0.5–1.0% of full scale and ±0.3–0.5 °C, respectively. Therefore, even an ideal model cannot be expected to achieve arbitrarily small prediction errors, since part of the observed deviation originates from measurement noise. The reported MAE and RMSE values in this study are of the same order of magnitude as the plausible sensor uncertainty, suggesting that a non-negligible portion of the residual error is likely due to data-level uncertainty rather than purely model deficiencies.

5.5. Generalization Ability Test

To assess the generalization capability of the proposed model, the trained model was transferred and tested on the ASHRAE B2 dataset. Compared with B1, B2 differs in its floor area and climatic conditions, which allows us to preliminarily examine the robustness of the proposed model across office buildings with different scales and environmental contexts.

It should be noted that both B1 and B2 are office buildings, but they are located at different sites in the ASHRAE dataset, which correspond to different climatic conditions (e.g., different distributions of outdoor temperature and humidity) and building scales. To obtain an initial insight into the influence of climate and building characteristics on generalization, we compare the mean and variance of the outdoor temperature and HVAC energy consumption between B1 and B2. B2 exhibits higher temperature variability and a larger peak-to-average load ratio, indicating more pronounced seasonal and peak-load behaviours.

As illustrated in Figure 10, four independent experiments were conducted. From the cross-building experiments, the prediction errors on B2 are slightly higher than those on B1, which suggests that differences in climatic conditions and building operation patterns do affect the generalization performance. Nevertheless, the TCN-BiGRU-Attention model maintains a lower RMSE and MAPE than the baseline models on both buildings, indicating that the hybrid architecture retains a certain robustness across office buildings with varying climates. A more systematic sensitivity analysis across multiple building types (e.g., residential, retail, hospitals) and climate zones would be required to draw stronger conclusions, and this is left as an important direction for future work.

Figure 10.

Cross-Building Generalization.

5.6. Model Validation

Model validation in this study is conducted at two levels. First, an internal validation is performed by splitting the time series chronologically into training, validation, and test sets, and by using the validation set to tune hyperparameters and prevent overfitting through early stopping. Multiple independent runs with different random seeds are carried out, and the average performance on the test set is reported to reduce the influence of randomness.

Second, an external validation is carried out by transferring the model trained on Building 1 to Building 2, which has different floor area and climatic conditions. The results show that the TCN-BiGRU-Attention model maintains a competitive performance on Building 2, achieving an RMSE and MAPE comparable to those obtained on Building 1, which indicates that the model has a certain generalization capability across office buildings.

Moreover, the magnitude of the error metrics observed in this study is broadly consistent with the performance reported in recent HVAC energy prediction works using data-driven models, where MAPE values typically fall in the range of about 5–10% for similar hourly load forecasting tasks [XX–YY]. Although direct numerical comparison is limited by differences in building types, climates, and feature sets, this consistency suggests that the proposed model reaches a realistic level of predictive accuracy in line with the current state of the art.

6. Limitations and Future Work

Despite these achievements, there remain several directions for further improvement:

- (1)

- Validation and Optimization on Proprietary Datasets:

Considering the complexity of HVAC systems in real-world deployment, future research can focus on collecting and refining proprietary building energy datasets to validate and optimize the proposed model’s forecasting reliability under practical conditions.

- (2)

- Multimodal Feature Fusion and Climate Adaptability:

Future work could integrate multimodal data sources—such as thermal infrared imagery, semantic sensor data, and Building Information Modeling (BIM) information—to enhance the model’s adaptability to diverse building types and varying climatic environments.

It should be emphasized that the experiments in this paper were conducted at an hourly sampling resolution. Extending the evaluation to multiple temporal granularities (e.g., 15-min, half-hourly, or daily series) and explicitly modeling cross-granularity interactions will be considered in future work.

From a practical perspective, the proposed TCN-BiGRU-Attention model is suitable for deployment in both day-ahead and intra-day HVAC load forecasting scenarios. In an online application, the model can be used to generate rolling 24-h forecasts every hour based on the most recent 168 h of measurements, providing decision support for optimal operation scheduling and demand-side management.

Since the statistical characteristics of building loads may gradually drift due to equipment aging, occupancy pattern changes and retrofits, periodic model retraining with newly collected field data (e.g., on a weekly or monthly basis) is recommended to maintain long-term accuracy. In future work, we plan to investigate lightweight online update and transfer learning strategies to further reduce the maintenance cost. In addition, integrating the proposed model into building energy management systems (BEMS) to drive rule-based or optimization-based control actions will be an important direction towards real-time energy-efficient HVAC control.

Furthermore, the cross-building validation in this study is limited to two office buildings in different climate contexts. The generalization of the proposed model to other building types and climate zones has not yet been fully assessed.

7. Conclusions

This paper proposes a hybrid TCN-BiGRU-Attention model for building-level HVAC energy consumption prediction based on the ASHRAE public dataset. The model is designed to jointly exploit multi-scale temporal patterns through TCN, bidirectional contextual information through BiGRU, and key time slices through an Attention mechanism.

The evaluation results on B1 show that the proposed model outperforms several representative baseline methods, including GRU, TCN, TCN-GRU, Transformer, linear regression, and random forest. Specifically, the TCN-BiGRU-Attention model achieves the lowest MAE, RMSE, MSE and MAPE among all models, reducing the RMSE and MSE by approximately 22.2% and 54.1%, respectively, compared with the best-performing baseline. The visualization of prediction curves indicates that the proposed model can more accurately track both the overall trend and most of the peak loads, which is crucial for reliable HVAC operation and demand-side management.

Ablation experiments further confirm the effectiveness of the hybrid architecture. Removing any submodule (TCN, BiGRU, or Attention) leads to a noticeable degradation in prediction accuracy, showing that each component plays a distinct and complementary role in multi-scale temporal feature extraction, bidirectional context modeling, and time-step weighting. The Attention visualization provides additional interpretability by highlighting the time periods that contribute most to the prediction, such as typical start-up and peak operation hours.

The cross-building generalization experiment using B2 demonstrates that the model maintains satisfactory performance when transferred to another office building with different floor area and climatic conditions, suggesting that the proposed approach has a certain degree of robustness across buildings. Combined with the analysis of measurement uncertainty, these results indicate that a substantial portion of the residual error may be attributed to data-level noise rather than purely model deficiencies.

From a practical perspective, the proposed model is suitable for day-ahead and intra-day HVAC load forecasting applications. With its relatively low inference cost and improved predictive accuracy, the model can be embedded into building energy management systems to support proactive scheduling, peak shaving, and energy-saving strategies. Periodic retraining with newly collected field data is recommended to maintain long-term accuracy.

In summary, this work contributes a hybrid, interpretable deep learning framework for HVAC energy consumption prediction, together with a comprehensive evaluation on a publicly available dataset. Future work will focus on extending the model to more building types and temporal granularities, integrating it with advanced control strategies, and developing online updating mechanisms for long-term deployment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.D. and L.W.; methodology, J.D.; software, L.W.; validation, J.D., L.W., J.Z. and W.G.; formal analysis, L.W., J.Z. and W.G.; investigation, L.W. and W.G.; resources, D.L. and L.W.; data curation, D.L., J.Z. and L.W.; writing—original draft preparation, J.D.; writing—review and editing, J.D., L.W. and W.G.; visualization, J.Z. and W.G.; supervision, L.W. and W.G.; project administration, J.Z. and W.G.; funding acquisition, D.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the following projects: Shanxi Provincial Key Research and Development Program (202302010101005): Research, Application, and Demonstration of Big Data Key Technologies for Cultural Relic Protection and Monitoring. State Grid Shanxi Electric Power Company Science and Technology Project (52051C24000H): Research on Intelligent Distribution Network Operation Optimization Based on Deep Learning and Big Data Simulation Technologies. Shanxi Province Open Bidding for Selecting the Best Candidates Project (202401020101003). National Natural Science Foundation of China (U25A20433).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. They are restricted to experimental results.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments, which helped improve the quality of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Limin Wang was employed by the company Shanxi Construction Investment Group Co., Ltd. Author Wei Gao was employed by the company Shanxi Institution Group Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HVAC | Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning |

| TCN | Temporal Convolutional Network |

| GRU | Gated Recurrent Unit |

| BiGRU | Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| LR | Linear Regression |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| MAPE | Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

| BEMS | Building Energy Management System |

| Nomenclature | |

| Parameters | |

| t | Current time index |

| L | Length of the input time window |

| P | Length of the prediction horizon |

| d | Dimension of the input feature vector |

| Input multivariate time series window at time t, ∈ | |

| Predicted HVAC energy consumption sequence | |

| Actual HVAC energy consumption at time t | |

| η | Learning rate |

| θ | Model parameters |

| Error metrics | |

| MAE | Mean absolute error (kW) |

| RMSE | Root mean square error (kW) |

| MAPE | Mean absolute percentage error (%) |

| R2 | Coefficient of determination (-) |

References

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Energy Efficiency 2025–Buildings; IEA: Paris, France, 2025. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-efficiency-2025/buildings (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- U.S. Department of Energy; Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE). Energy-Saving Homes, Buildings, and Manufacturing: Fact Sheet. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/eere/articles/energy-saving-homes-buildings-manufacturing-fact-sheet-office-energy-efficiency-and (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Whole Building Design Guide. High-Performance HVAC; National Institute of Building Sciences: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.wbdg.org/resources/high-performance-hvac (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Chen, S.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, G.; Fan, C.; Ding, P.; Chen, Q. An online physical-based multiple linear regression model for building’s hourly cooling load prediction. Energy Build. 2022, 254, 111574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabdulrazzaq, H.; Alenezi, M.N.; Rawajfih, Y.; Alghannam, B.A.; Al-Hassan, A.A.; Al-Anzi, F.S. On the accuracy of ARIMA based prediction of COVID-19 spread. Results Phys. 2021, 27, 104509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otchere, D.A.; Ganat, T.O.A.; Gholami, R.; Ridha, S. Application of supervised machine learning paradigms in the prediction of petroleum reservoir properties: Comparative analysis of ANN and SVM models. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 200, 108182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speiser, J.L.; Miller, M.E.; Tooze, J.; Ip, E. A comparison of random forest variable selection methods for classification prediction modeling. Expert Syst. Appl. 2019, 134, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Magoulès, F. A review on the prediction of building energy consumption. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 3586–3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciampi, F.G.; Rega, A.; Diallo, T.M.; Pelella, F.; Choley, J.-Y.; Patalano, S. Energy consumption prediction of industrial HVAC systems using Bayesian Networks. Energy Build. 2024, 302, 113663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Cai, X.; Dai, L. Prediction of building HVAC energy consumption based on least squares support vector machines. Energy Inform. 2024, 7, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Huang, H.; Wu, H.; Huang, Y. Energy consumption dynamic prediction for HVAC systems based on feature clustering deconstruction and model training adaptation. In Building Simulation; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 2024; Volume 17, pp. 1439–1460. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, T.; Zhu, Z.; Luo, H.; Li, C.; Jin, X.; Meng, Z.; Cai, X. Probabilistic HVAC Load Forecasting Method Based on Transformer Network Considering Multiscale and Multivariable Correlation. Energies 2025, 18, 5073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Lu, S.; Zhou, S.; Tian, Z.; Kim, M.K.; Liu, J.; Liu, X. A Systematic Review of Building Energy Consumption Prediction: From Perspectives of Load Classification, Data-Driven Frameworks, and Future Directions. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Chen, Y.; Xue, Q. Survey on research of RNN-based spatio-temporal sequence prediction algorithms. J. Big Data 2021, 3, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, L.; Lin, Y.; Tan, J. Cross-sectional performance prediction of metal tubes bending with tangential variable boosting based on parameters-weight-adaptive CNN. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 237, 121465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Wei, C.; Wang, B.; Yang, J.; Xu, X.; Wu, S.; Huang, S. Well performance prediction based on Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) neural network. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 208, 109686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, U.; Bhattacharjee, V.; Bishnu, P.S. StockNet—GRU based stock index prediction. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 207, 117986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Yun, S.; Jia, L.; Guo, J.; Meng, Y.; He, N.; Li, N.; Shi, J.; Liu, Y. Hybrid VMD-CNN-GRU-based model for short-term forecasting of wind power considering spatio-temporal features. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 121, 105982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, D.; Jia, M. A BiGRU method for remaining useful life prediction of machinery. Measurement 2021, 167, 108277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, S.; Shin, J.; Kwon, S.; Lee, S.; Kang, S.; Lee, D. PM10 and PM2. 5 real-time prediction models using an interpolated convolutional neural network. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Zhang, K.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, B. Parallel spatio-temporal attention-based TCN for multivariate time series prediction. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 13109–13118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Shen, J. Deep visual attention prediction. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2017, 27, 2368–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, S.K.; Shrivastava, V.; Udmale, S.S. Enhanced Electricity Forecasting for Smart Buildings Using a TCN-Bi-LSTM Deep Learning Model. Expert Syst. 2025, 42, e70000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Gao, Y.; Ji, T.; Wan, X.; Ye, F.; Bai, G. Deep temporal convolutional networks for short-term traffic flow forecasting. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 114496–114507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 261–272. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Cai, Z.; Luo, Y.; Wen, Z.; Ying, S. Long time series deep forecasting with multiscale feature extraction and Seq2seq attention mechanism. Neural Process. Lett. 2022, 54, 3443–3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Wang, Z. TCN-attention-HAR: Human activity recognition based on attention mechanism time convolutional network. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Pan, F.; Li, D.; He, H.; Zhang, T.; Yang, S. Prediction of photovoltaic power by the informer model based on convolutional neural network. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE. ASHRAE—Great Energy Predictor III. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/c/ashrae-energy-prediction (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Huang, W.; Xu, J. A Proposed Recursive TCN-GRU for the Time-Series Forecast of Engineering Vibration. J. Vib. Acoust. 2025, 147, 61008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).