Abstract

Parabolic dish collectors (PDCs) focus solar radiation onto a small area, minimizing the heat-loss area of the solar receiver and improving the heating of the working fluid. This fluid usually drives a Stirling-like or micro-gas turbine (Brayton-like) power generator. PDCs, initially intended for small-capacity applications, are well-suited for electricity and heat generation in remote rural areas, working alone and/or as parabolic dish arrays. PDCs have received considerable attention among solar thermal collectors due to their high concentration ratios and the high temperatures they achieve. However, nowadays, they are the least developed and least commissioned among concentrated solar power configurations, lacking a well-established technology. This review aims to compile the evolution of research on PDCs over recent years from a global perspective and is mainly focused on the subsystems constituting a PDC plant, their integration, and overall system optimisation, thereby addressing a gap in the current literature. Methodological tools used in the field are comprehensively revised, and recent related projects are summarized. Some innovative and promising applications are also highlighted.

1. Introduction

Swedish engineer and inventor John Ericsson (1803–1889) is considered the first person to couple a parabolic mirrored dish to a heat engine (see Figure 1, [1]) transforming solar energy into mechanical energy through a thermodynamic cycle (resembling the Stirling cycle) in the decade of 1880s and it was named ‘solar motor’. Nevertheless, this form of power production was more complex and more expensive than burning coal. The boom in vapor engines halted the development of this model for over a century. Due to the oil crisis of 1973, a renewed interest in dish collectors arose and countries as the United States, Australia, Germany, and France began their own research programs on the development of Concentrated Solar Power (CSP) technologies [2].

Figure 1.

Original Ericsson’s solar motor. Taken from [1].

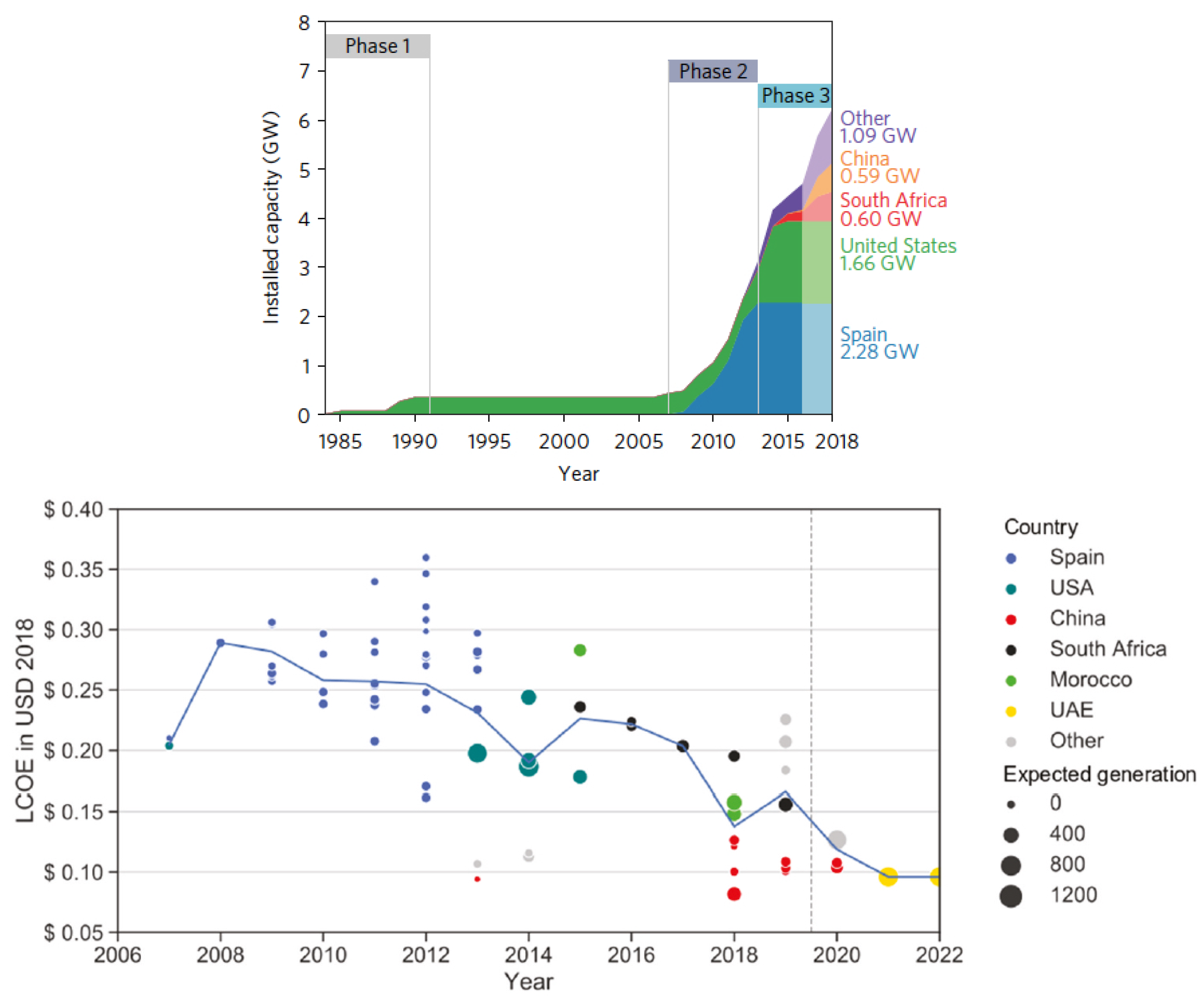

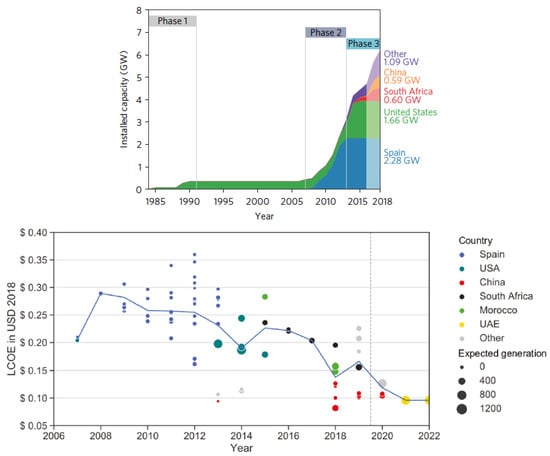

From the beginning of the 1990s to the present day, technological startups focused on renewable energy have sought to improve the commercialization of this technology. However, success has been limited due to competition and its technological immaturity. Nowadays, the need for clean, renewable, and controllable solutions for the production of heat and electricity, while avoiding the use of expensive and scarce raw materials, has driven the research and development of Concentrated Solar Thermal (CST) systems. Inside the renewable energy systems, CSP technology is particularly attractive when compared with hydropower systems (usually associated with environmental problems or social objections), with wind turbines (associated with higher emissions), and with photovoltaic facilities (associated with intermittencies and with less time-consuming services). Figure 2 shows an illustrative view of the evolution in both installed capacity and the corresponding Levelized Cost of Electricity (LCoE).

Figure 2.

(Top): Evolution of CSP capacity around the world up to 2018, countries share is also plotted [3]. Solid colors show existing capacity and transparent ones that capacity that was under construction. (Bottom): Levelized cost of electricity (in 2018 USD/kWh) for all the plants: the ones already existing and the ones that were under construction (up to 2018) [4].

Geometrical and physical characteristics of components that receive solar energy and convert it into useful heat or power output are key in CST and CSP. Currently, the most mature approach in thermosolar electricity production is the deployment of linear parabolic troughs. However, the most innovative and promising technologies are the parabolic dish and central tower configurations due to their capabilities to obtain high temperatures (largest concentration factor [1000–3000]) in a working fluid for heat and power facilities [5,6,7,8,9]. In particular, parabolic dish applications range from small-scale generation, in distributed generation of power or heat [0.01–0.4] MW up to the so-called parabolic dish arrays or farms [10] to produce power or heat in large-scale applications using its modular flexibility and adaptability [11,12,13,14,15].

On the other hand, most of the literature on CSP agrees that the lack of implementation of PDC compared to other technologies is mainly due to two unsolved generic problems: first, one associated with inherent problems of reliability, durability, and overall performance linked to the intricate parabolic dish design of Stirling and micro-gas turbine (MGT) systems and, second, another one regarding the difficulties of integrating them with thermal energy storage (TES) and/or hybridization systems. In more detail, the following four points about the main causes can be highlighted:

- (a)

- System complexity and lack of economic modularity: Each parabolic dish is an independent unit with its own collector, receiver, and power block (usually Stirling or micro-gas turbine). This prevents economies of scale from being achieved, unlike concentrated parabolic trough or central tower systems, where many heliostats feed a single receiver or power block. A direct consequence is the higher LCoE of electricity compared with other CSP technologies [16].

- (b)

- High manufacturing and high maintenance costs: PDCs require very high optical precision and a lightweight but rigid structure to maintain their shape under wind or thermal load. More efficient biaxial alignment and tracking are more expensive and mechanically more complex than the uniaxial tracking of cylindrical-parabolic collectors. This requires careful maintenance, high tightness, and expensive components as seals and high-temperature-resistant materials that play a key role [2,16].

- (c)

- Difficulties for integrating thermal storage: The simplest PDC configurations directly convert solar radiation into mechanical or electrical energy in each unit, without passing through a common working fluid (such as thermal oil, molten salts, steam, etc.). The incorporation of an effective thermal storage is still under evaluation. Indeed, this could be a competitive advantage of the PDCs over photovoltaics [16].

- (d)

- Limited maturity and industrial backing: Concentrated Trough and Tower technologies received considerable institutional and commercial support since the 2000s. In contrast, dish-Stirling systems were only developed in pilot or demonstration projects, many of which did not prosper due to bankruptcy or lack of investment. Well-known examples are the solar projects Sandia [17], Maricopa [18], Calico [19], and Imperial Valle [20] (this one eventually replaced by the Mount Signal Solar project, with photovoltaic panels).

A direct consequence is their high costs in comparison to large parabolic troughs with more technological maturity [3,4,9,21], as has been validated by neural network prediction models for the energy producibility in existing demo dish–Stirling solar concentrator [22]. PDCs remain potentially suitable for distributed installations and/or remote locations where storage and connection to a large grid are not required. But, as noted by the International Energy Agency (IEA) [23], even in this segment, they remain economically noncompetitive compared to PV systems. The same conclusion is highlighted by Awan et al. [24] under the energy and economic perspectives. A recent update on the status of CSP installed worldwide can be seen in ref. [25]: Figure 4 in this work shows the repartition of the CSP technologies in the period 1990–2022, including operational trough, tower, Fresnel, and dishes technologies, and the conclusion is that there is currently no dish solar power plant in operation.

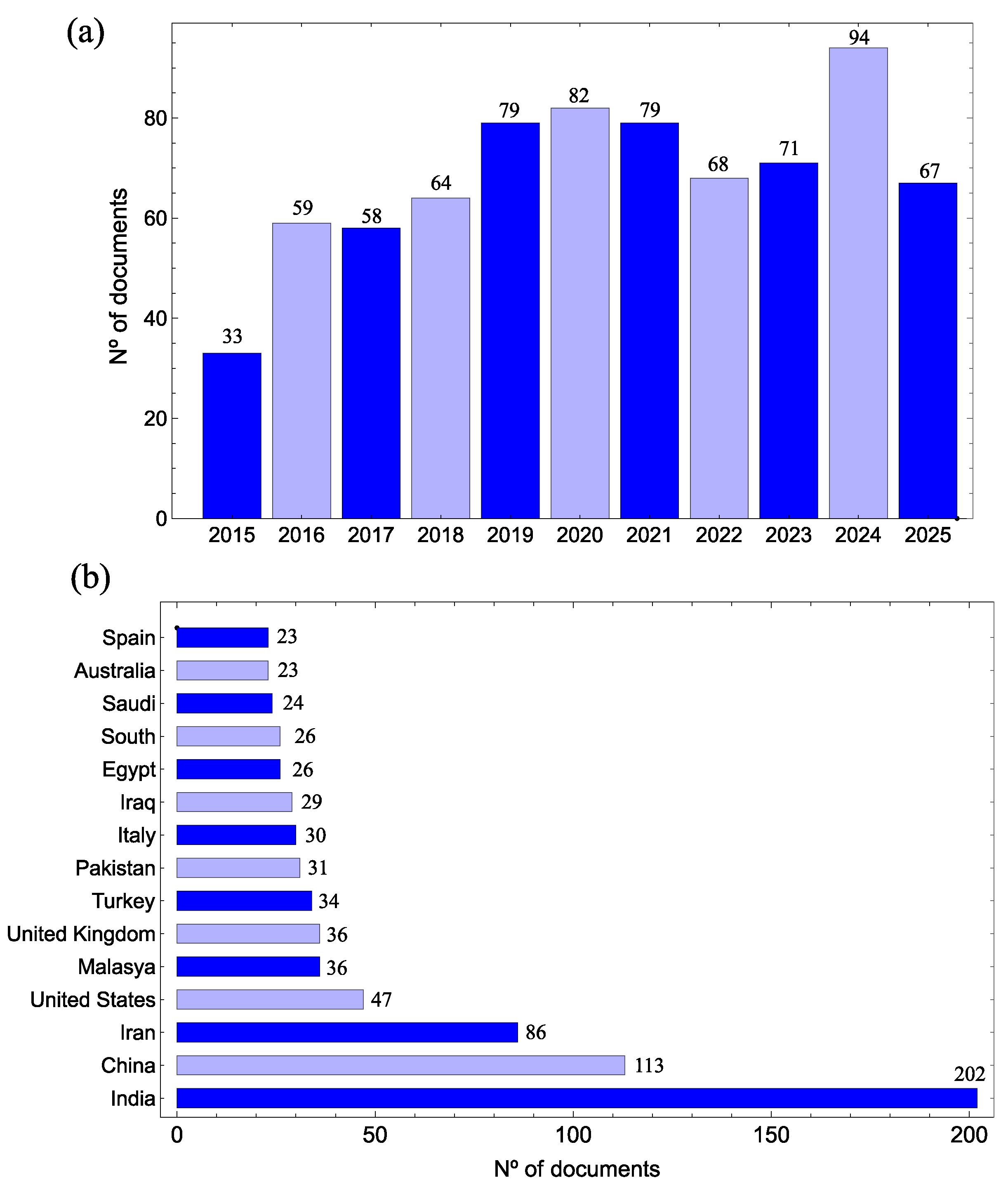

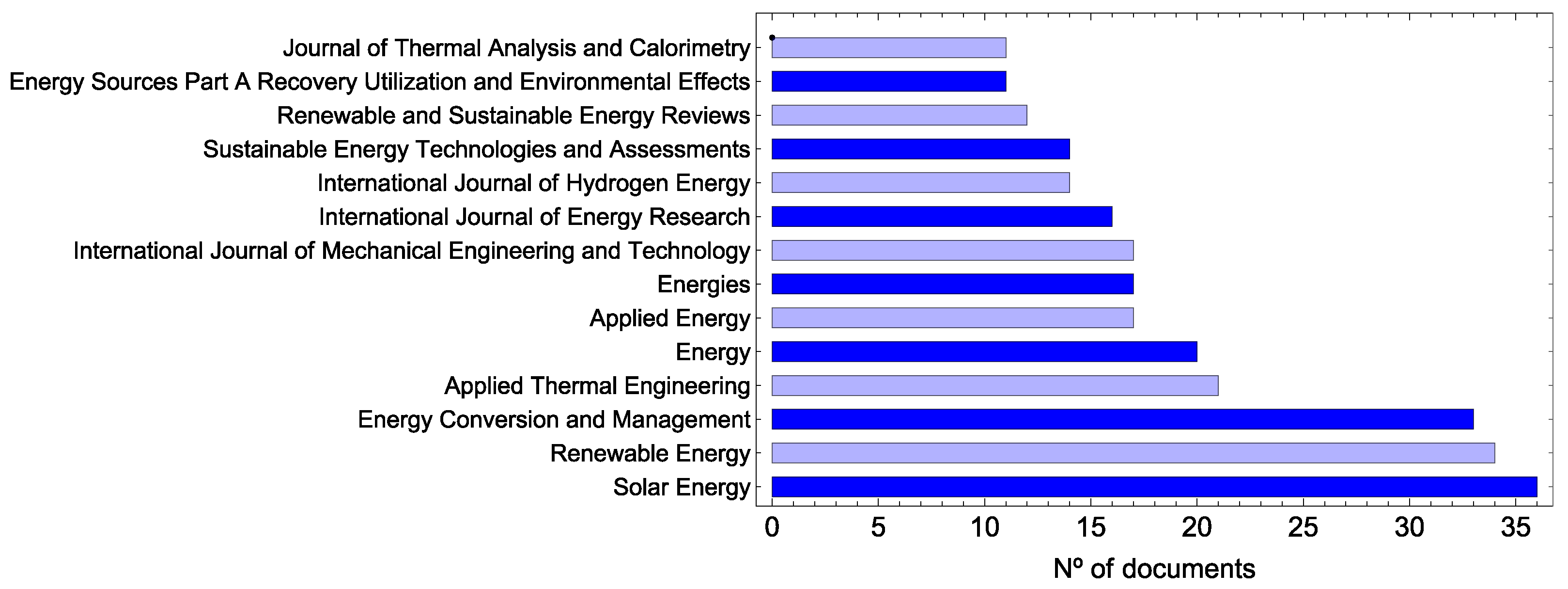

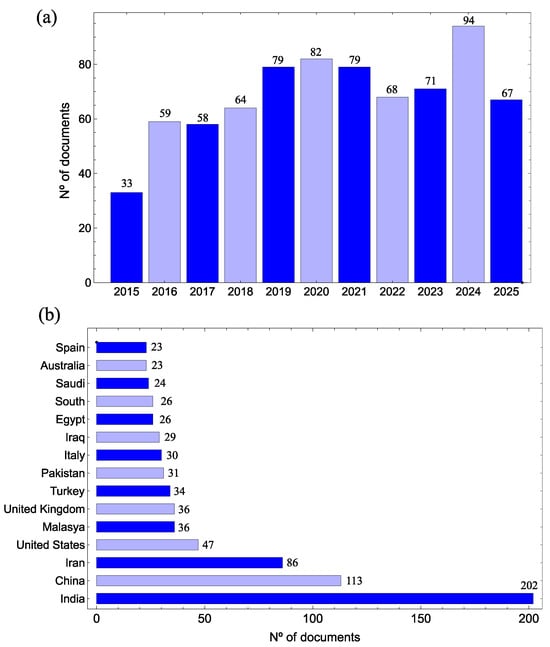

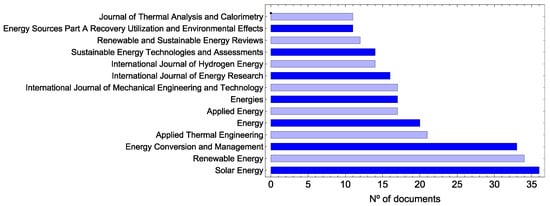

Compared with other topics, there is a scarcity of PDC publications in the available literature. In Figure 3 and Figure 4, the number of documents published on the PDC topic is presented. Data is taken from the Scopus database. The document selection criteria include “Parabolic Dish” as a keyword to perform a general search on the topic. Only “article” and “review” document types have been selected and all of them are included within “journal” sources. The target span time is 11 years, from 2015 to 2025 (2 December), as presented in Figure 3a. The total number of documents found is 754. In the last 10 years, the number of documents published worldwide per year is 72, which is relatively low. Regarding the geographical distribution of the analyzed documents, India and China lead the ranking, with 202 and 113 published documents in the last decade, respectively (see Figure 3b). The PDC topic is distributed across different journals as shown in Figure 4. Although Solar Energy, Renewable Energy and Energy Conversion and Management stand out among the other journals, they only include 13.66% of the total number of published documents. After this brief bibliographic search, partially based on Vishnu et al.’s [26] work and to the author’s knowledge, it can be stated that there is even stronger scarcity of exclusive PDC reviews in the surveyed literature [2,5,6,7,8,26,27,28].

Figure 3.

Number of documents published on the “Parabolic dish” topic within the period 2015–2025, according to the Scopus database. (a) Publications per year and (b) publications per country.

Figure 4.

Number of documents published on the “Parabolic dish” topic per journal within the period 2015–2025. Data are taken from the Scopus database.

For further detailed information, the review performed by Vishnu et al. [26] contains a very recent and comprehensive update of the bibliographic evolution on PDCs. The present work is specially oriented in a broader context and aimed at a wide range of specialist and non-specialist readers. The first part analyzes the main elements of a PDC-based plant (solar collectors, solar receivers and heat transfer fluids, dish-Stirling or Brayton-like thermodynamic cycles and working fluids), emphasizing methodological tools, their integration, and overall system optimization. The second part summarizes some related research projects. Next, some future prospects for the most critical components (as the solar collector and the solar receiver) are detailed, including the main promising applications derived from the potentially high temperatures that can be reached: solarized fuels, hybridization and Combined Heat and Power (CHP) applications including domestic heat and water treatment, as well as the storage capabilities with Phase-Change Materials (PCM).

2. Main Elements of a PDC-Based Plant

A standard PDC system is the resulting device of the coupling of three main elements: concentrator, receiver and a power block or energy conversion unit. A paraboloidal collector reflects and concentrates incoming solar radiation onto the (idealized) focal point by using a bi-axial solar tracking system that is able to align the focal axis with the direction of sunrays by following the solar position throughout the day. The receiver provides heat to the power block to keep the necessary initial high temperature in the expansion step before the unavoidable dissipation into the environment. The conversion of the solar radiation is realized by the power block, or an energy converter unit (typically a Stirling engine or a micro-turbine), and an electrical generator for the final step of converting mechanical energy into electricity. Next, the main subsystems that comprise a typical PDC are reviewed, together with the available resources for their modeling.

2.1. Solar Collector

The solar collector generally comprises a parabolic reflective surface, a supporting structure able to withstand the weight and variable wind loads, and a tracking system, which aligns the dish axis with the Sun’s rays [13]. The tracking system with a two-axis structure that follows the elevation and azimuth Sun coordinates is the usual and more efficient device [2].

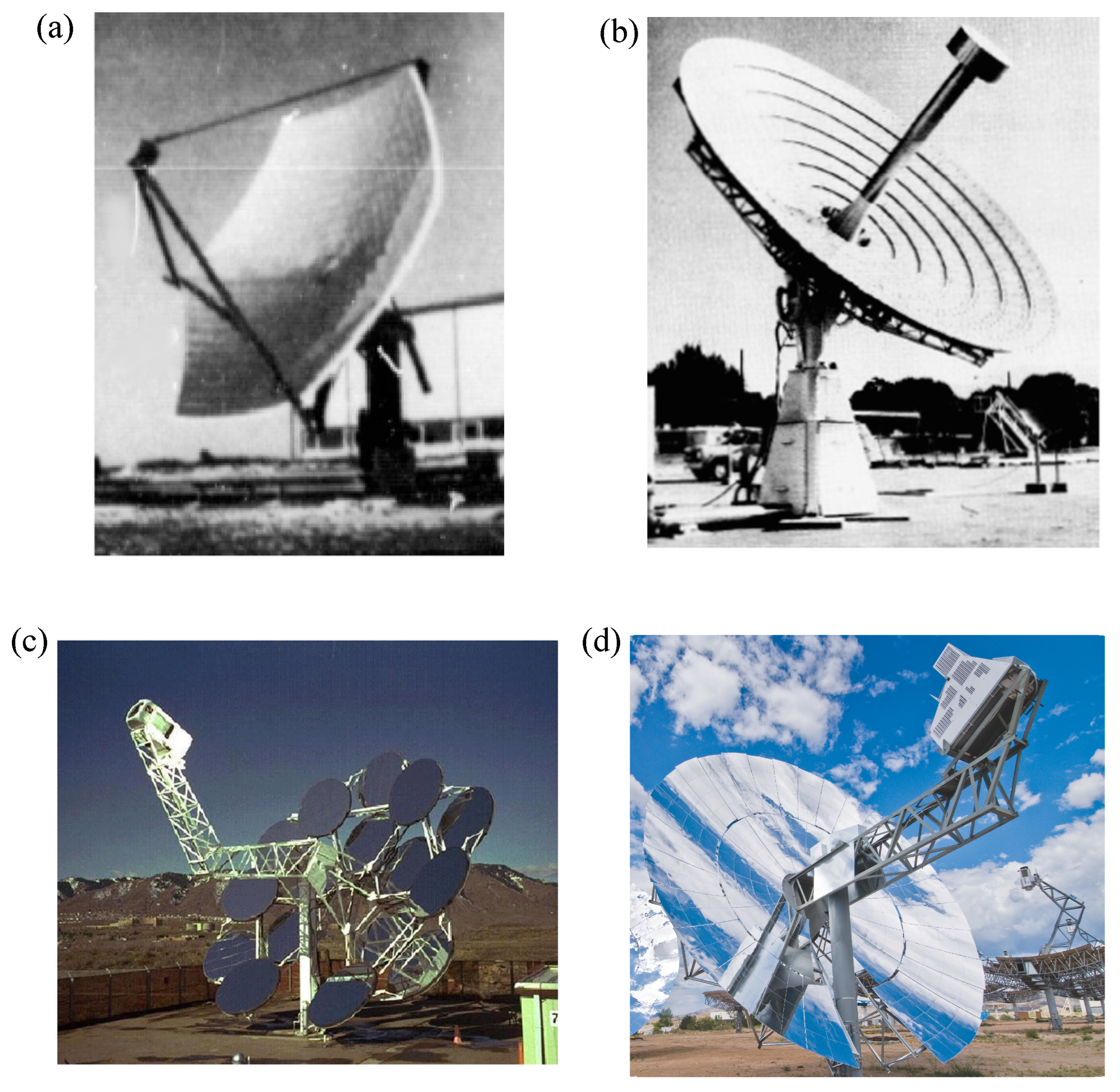

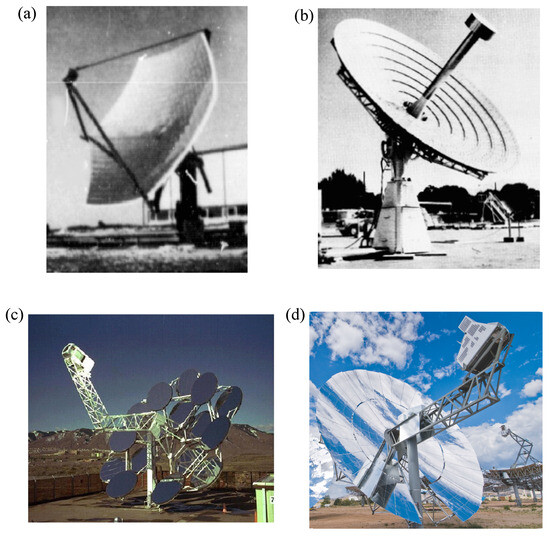

Real collectors aim to approximate the ideal parabolic shape using multiple reflective facets mounted on a truss structure [6,29]. THEK 2 (thermo-helio-electricity-kW), one of the first PDCs proven in the early 1980s, counted with triangular glass mirrors (Figure 5a), as well as SG3 Big Dish, constructed at the Australian National University (ANU) in 1994 [2]. The circumscribing shapes of both systems were hexagons, not circles. Another particular type of solar collector, recently known as discretized solar dish collector (DSDC) [7], was first implemented in the Raytheon dish by 1985 [2]. The collector consisted of spherical concentric mirror segments (see Figure 5b) that, according to the optimization study performed by Yan et al. [30], could achieve an optical efficiency of 92%. The “SunDish” dish-Stirling system, developed by the Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC) between 1997 and 1999, presented a new configuration of the mirror facets. They were placed in a staggered arrangement aiming to reduce the wind loads due to the increased porosity [2] (see Figure 5c). Finally, the most modern collectors (for example, the SunCatcher system, designed by Sandia National Laboratories in 2009) are made of stamped panels arranged in a “petal” (trapezoidal-shaped facets) arrangement (Figure 5d).

Figure 5.

Different types of solar collectors [2]: (a) THEK 2, triangular mirrored facets, (b) Raytheon dish, spherical concentric mirror segments; (c) SunDish, staggered facets arrangement, and (d) SunCatcher, trapezoidal shape facets.

To obtain the highest share of reflected radiation, different combinations of glass, silvered surfaces, and aluminum can be found among the reflective materials. The most common configuration is to cover the front or the back surface of glass or plastic with aluminum or silver [6]. Vanguard and Schlaich Bergermann und Partner (SBP) 7.5 project, whose surface was a combination of glass and silver, reported reflectivities of 93.5% and 94%, respectively. Some of the first prototypes, such as THEK 1 and 2, counted with glass mirror facets bonded to fiberglass [2]. The reflective surface of the Omnium-G dish was made of polished aluminum facets. Sandwich panels made of fiberglass and covered by aluminized polyester film were employed in PDC like PDC-1. Two aluminum face sheets, aluminum honeycomb core, and a thin glass mirror bonded to the front are other examples of the sandwich configuration (used in Stirling Energy System and Advanced Dish Development System prototypes) [2].

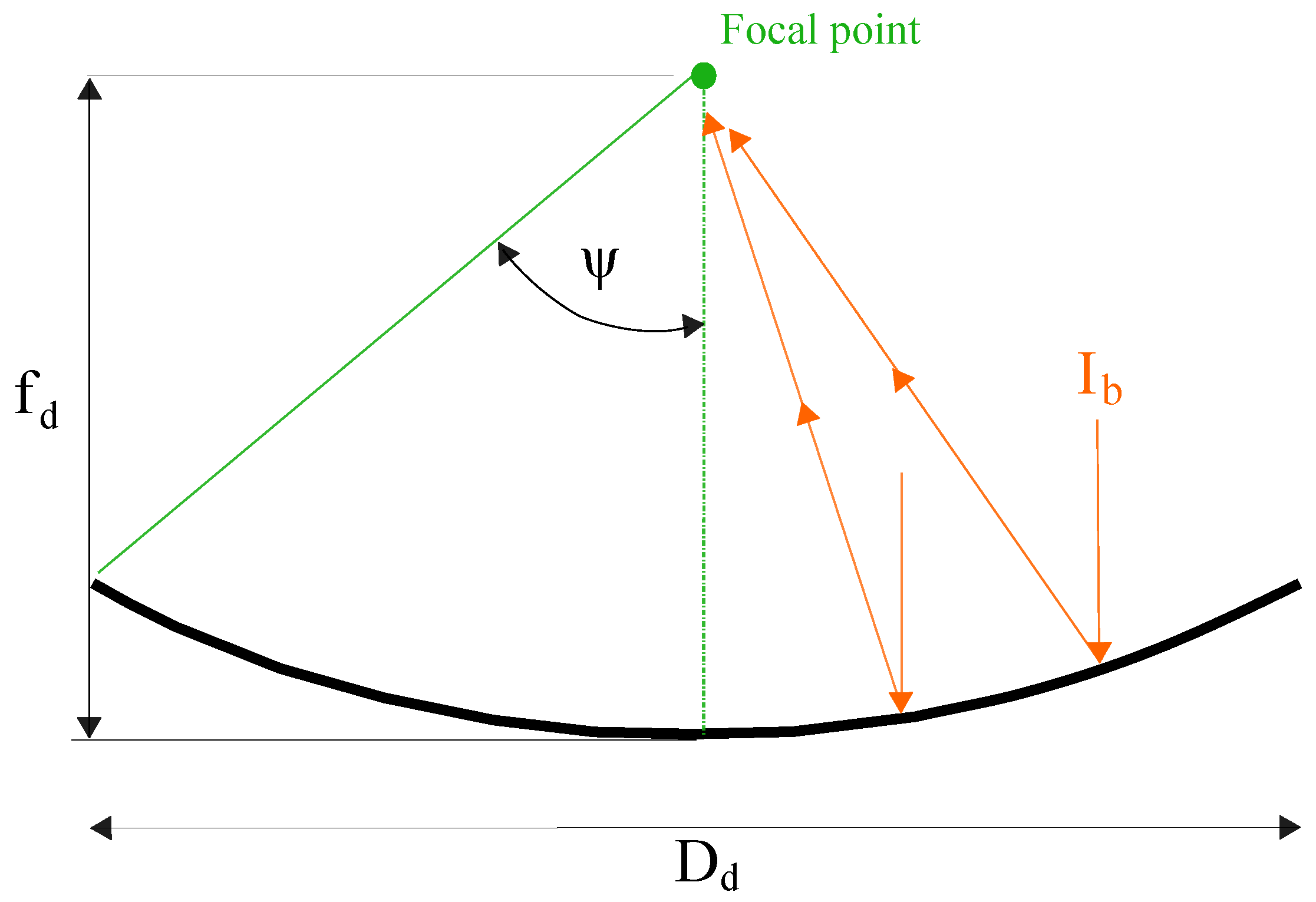

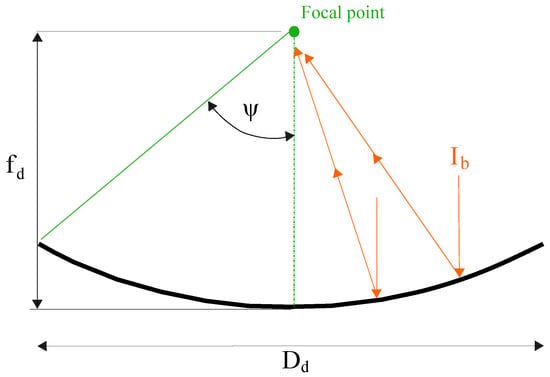

From a geometrical viewpoint, just a few parameters are needed to characterize the solar collector: the aperture diameter, , and the rim angle, (see Figure 6). Both of them serve to determine the focal length, , through the following expression [7,31]:

Theoretically, the ideal rim angle is 45° [31,32]. The aperture diameter, , should be chosen according to the power cycle and power output desired, with typical values ranging between 3 to 10 m [6,29]. Stine and Harrigan [32] provide a differential equation to calculate the radiant flux, , reflected by the parabolic collector towards the receiver:

where is the impinging photon intensity and l is the length of each differential circumference over the parabolic dish surface, along the focal axis direction.

Figure 6.

Scheme of a PDC geometrical parameters. Focal distance (), rim angle (), and aperture diameter (Dd). stands for the photon intensity. Adapted from [12].

At the time of designing a real parabolic dish collector, its efficiency is not only influenced by geometrical parameters, Equations (1) and (2), but also by others such as the surface reflectivity or the possible slope errors, denoted by . Reflectivity is a parameter determined by the material properties of the mirrored surface, while slope error is associated with the deviation of the surface from a true parabolic shape. Other sources of errors at the reflective surface are non-specular reflection (), tracking errors (), and receiver alignment () [32]. Since those sources of errors are generally random, they are assumed to follow a Gaussian distribution, with a standard deviation [32,33]. Finally, another error to consider is the Sun’s shape. Since the Sun has a finite angular size, the rays arriving at the collector are not completely parallel. If a standard distribution is assumed for the solar disk, the error associated with the Sun’s shape () is 2.8 mrad [32]. In addition, those errors can be classified as 1D errors, which are those that affect the beam path in the plane of curvature ( and ) and 2D errors, which affect the ray bidirectionally ( and ) [32]. All those errors can be combined as follows:

where stands for the total error and is the incidence angle. Note that is multiplied by 2 because a deviation of radians on the normal surface causes a deviation of radians on the reflected ray hitting the receiver (Snell’s law).

The ideal optical efficiency would be equal to 1 if all the rays impinging on the parabolic surface were perfectly reflected to the receiver. Nonetheless, all the errors previously introduced affect the optical performance. The typical values reported in the literature for the optical efficiency range between 88% and 90% [11,31].

Methodologies

There exist some diverse tools for effectively modeling the parabolic surface and obtaining a good approximation to the optical efficiency. Ray-tracing software has been widely used in the last decade for the optical design of CSP systems. This type of software can evaluate optical performance based on the selected material, Sun shape, shading effects, surface errors, receiver shape and size, etc. Osorio et al. [33] performed a review analysis on the most relevant ray-tracing software commonly used. In Table 1, a summary of Osorio’s review is presented. Most software (Tonatiuh, SolTrace, OTSun, etc.) uses the Monte Carlo method, so it can be denominated Monte Carlo Ray Tracer (MCRT) software. This method works by virtually launching random rays towards the established surfaces. The photon energy is equally distributed among all the rays, and it will depend on the number of rays and the considered Direct Normal Irradiance (DNI). The way in which rays interact with surfaces depends on the optical properties assigned to them (reflectivity, specularity, slope error, etc.).

Table 1.

Summary of the ray-tracing software analysed in [33]. UIB refers to Universitat de les Illes Balears, ISE is the Fraunhofer-Institut für Solare Energiesysteme and DLR is the Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt. MCRT = Monte-Carlo Ray Tracer.

The Sun model and surface errors reported in Table 1 refer to the statistical distribution of the sunlight and superficial errors, respectively. Pillbox refers to a 2D step-function distribution [34] and Lambertian distribution represents how diffusely is light reflected [35]. Those two distributions, together with Gaussian and “ideal” ones, could be applied both to the Sun shape and surface errors. A more realistic distribution for simulating the Sun shape is the Buie distribution [36] which considers the share of energy contained in the circumsolar aureole through the introduction of a parameter called circumsolar ratio (CSR). Apart from the software exposed in Table 1, there are other computer programs devoted to CSP optical simulations: COMSOL [37], TracePro [38], which combines MCRT, CAD import/export and optimization methods, or SolarPILOTTM [39], devoted to simulate Solar Tower CSP systems.

Table 2 summarizes the main results above. The studies considered suggest the need for more accurate methods, based on geometric and ray tracing, to evaluate the specific function of each parameter involved, together with rapid calculations, and the development of simplified but accurate models. The influence of the material and shape of the reflector, the variable DNI in the concentrator, the diameter of the parabolic concentrator, and the size of the aperture should be the main objective of these studies. It is particularly important to incorporate dynamic models in the evaluation of the DNI (and related factors such as ambient temperature, wind speed, and mirror cleanliness) from the site location, going beyond the average (or quasi-average) conditions that are usually considered in some models [28,40,41].

Table 2.

Summary of the solar collectors and their main characteristics. ORC refers to Organic Rankine Cycle.

2.2. Solar Receiver and Heat Transfer Fluids

Solar receiver is one of the most crucial elements within CST systems as it sets the maximum temperature achievable in the system and, for CSP installations, the maximum power cycle temperature [42] and, so, the system efficiency. The solar receiver function is to turn the solar irradiance from the collector into usable heat. However, this is not a simple task. Several heat losses occur during the heat transfer, affecting the receiver efficiency. The emerging applications of CST systems, such as the production of “solar fuels”, require high outlet temperatures from the receiver [43]. Therefore, the challenging issues for boosting the solar receiver performance are focused, among others, on geometry, for minimizing heat losses, and materials, which eventually have to withstand increasingly larger temperatures (and so, steeper temperature gradients) [13,44]. Solar receivers can be classified according to various aspects (geometry, operating pressure and temperature operation levels, heat transfer fluid, etc.).

Regarding geometry, solar receivers can be classified as external or cavity type. External receivers have been mainly used in Central Tower Systems [44,45,46], where the absorber material consists of a vertical, cylindrical arrangement of pipes that transport a liquid or gas Heat Transfer Fluid (HTF). Stirling parabolic dishes, using direct illumination receivers, can also be included here [12,29] because the absorbing material is directly located on the exterior of the Stirling engine. The main drawbacks of external receivers relate to re-radiation effects, which are intensified with high temperatures (650–750 °C). Convection phenomena also contribute to removing heat from the receiver surfaces [13,44]. That is why a number of studies center their research on the “cavity” concept [42,43,47,48,49], where solar irradiance enters a cavity through an aperture area, thereby minimizing convective and radiative losses. Next, a summary of the main cavity receiver configurations is presented.

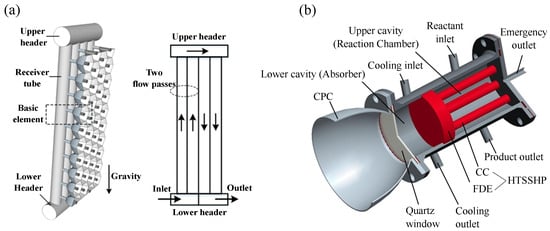

2.2.1. Tubular Receivers

This type of receiver can be either placed in a cavity to reduce heat losses or be external (as mentioned above for central-tower systems). Concentrating solar irradiance arrives onto the external walls of the tubes, which are usually made of stainless steel or other alloys [44]. In addition, they are the most economically feasible solar receivers and they can be built with low-cost materials [50].

The HTF, which can be liquid or gas phase, receives thermal energy from the tube’s inner walls, increasing its temperature via convection. Tubular liquid receivers have been studied since the 1970s, including HTFs such as water/steam, which can be directly used in power cycles; nitrate salts, which are also suitable for thermal energy storage; and sodium. However, nitrate salts decompose above 600 °C, and sodium is likely to react with oxygen. As high-temperature applications are increasing, other HTF options have been considered, such as fluorides, chlorides, or carbonated salts [44].

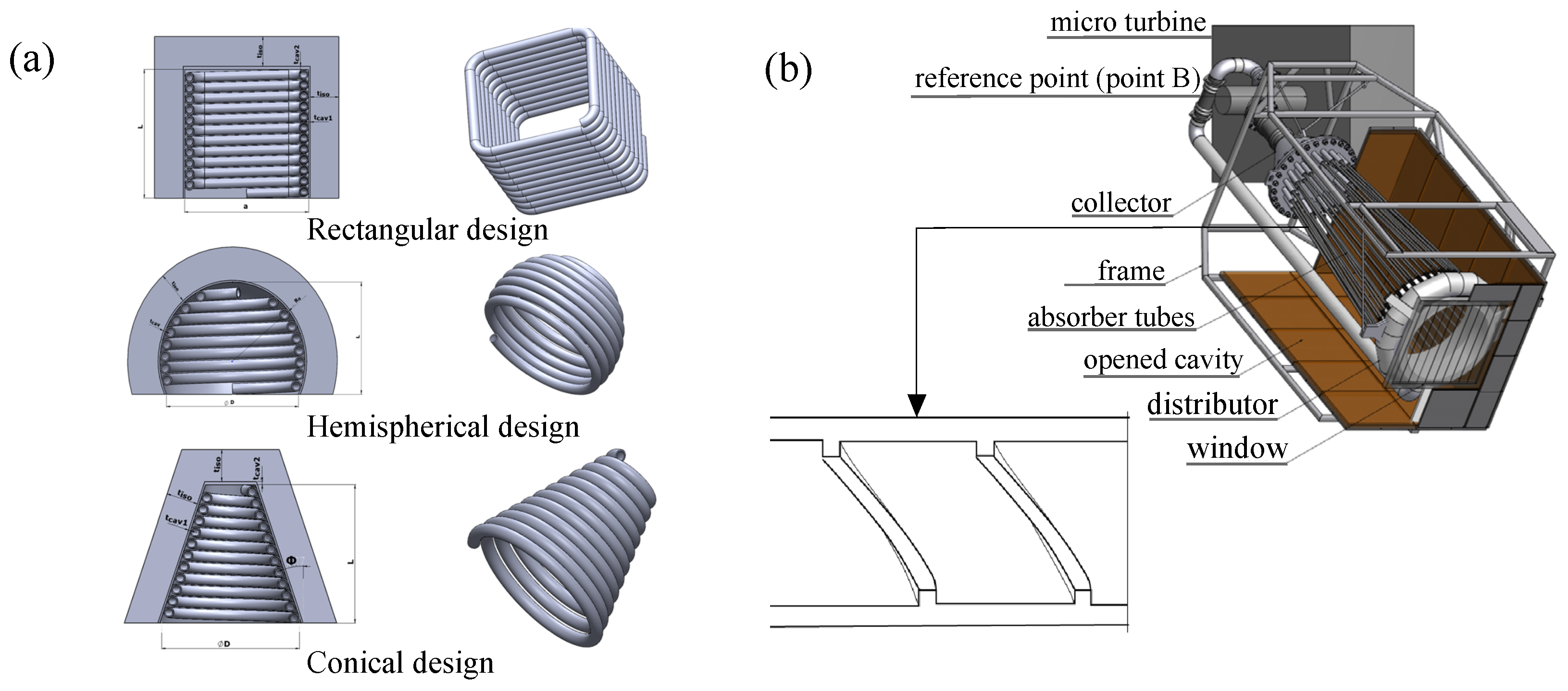

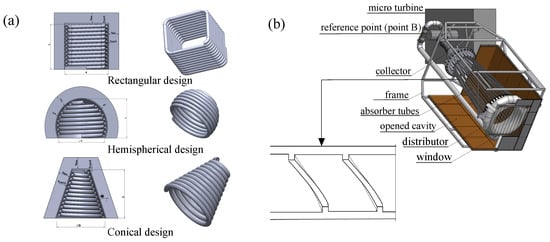

More compact geometries for tubular receivers have been developed (see Figure 7). Bellos et al. [48] and Kaesian et al. [51] performed a review of the different geometries applied to these receivers (cylindrical, hemispherical, conical, and flat sides—squared) (Figure 7a). Diameter, number of loops, HTF, and inclination [52] will affect the thermal efficiency of these receivers. Besides the traditional thermal oils (Cu, SiO2, TiO2, etc.), the addition of nanofluids to an HTF was employed and investigated, reporting an improvement in the cavity thermal efficiency up to 12.9% for hemispherical geometry [53]. Nanofluid analysis is a topic of increasing interest because of their improvements in heat transfer and energy efficiency [26,53,54,55]. However, some drawbacks must also be considered regarding their high production costs (up to 5320$ for 4 ℓ of TiO2 nanofluid) and/or their associated environmental impact [26,54].

Figure 7.

Tubular receivers: (a) Different geometries for molten salt tubular receivers integrated into a PDC [48], (b) SolHyCo tubular receiver and wire-coiled tube [43,56].

Gas-phase receivers with higher operating temperatures are gaining interest [43] due to the increasing need for very high temperatures in the power block. Air is the predominant HTF because of its versatility: it can be used directly as a working fluid in the power cycle. Moreover, gaseous HTFs are non-toxic, exhibit no high-temperature phase change, and are low-cost [49]. Gas-phase tubular receivers exhibit low heat transfer rates due to pressure drops and thermal resistance of the tube material. Some solutions include increasing the heat transfer area or enhancing the heat transfer rate. The latter was the objective of the SolHyCo (SOLar-HYbrid power and COgeneration plants) [56] project because it was the cheapest option. The SolHyCo receiver tubes count with a wire-coil (see Figure 7b) inserted inside the tubes to destroy the boundary layer and mix the HTF. The coiled tubular receivers integrated into solar dish collectors also employ gases such as helium for Stirling engine applications or pressurized air, achieving efficiencies between 53.16% [57] (conical geometry) and 70% [58] (cylindrical geometry).

2.2.2. Heat Pipe Receivers

Heat pipe receivers are suitable for heating working fluids, such as air (Brayton cycles) or helium (Stirling cycles) [59] and they are based on a liquid-to-vapor phase change. Solar irradiation will evaporate a liquid, turning it into vapor. Because of the pressure difference, the vapor is forced to enter into a condenser, where the working fluid absorbs the heat and the HTF returns to the liquid phase [59]. The employed HTFs are liquid metals, as they can effectively withstand high radiation fluxes due to their large heat transfer coefficients (30 kW/m2 K). Moreover, since thermal energy is transferred as latent heat, the process occurs (almost) isothermally. Most modern heat pipe receivers have employed molten salts as HTF (Figure 8a) [60], reporting efficiencies ranging from 88.5% to 91.5%. Ma et al. [61], although using a traditional HTF as sodium, proposed a novel geometry for a “solar thermochemical coupling phase change reactor” (STCPCR). The evaporator is a flat disk shape, aiming to minimize the heat dissipation area, while the condenser comprise cylindrical pipes for transporting thermal energy over relatively long distances (Figure 8b). The efficiency of the STCPCR depends strongly on the nitrogen cooling gas mass flow rate. For a mass flow of 33 m3/h, the thermal efficiency could achieve 90%.

Figure 8.

Heat pipe receivers: (a) Molten salts [60]; (b) STCPCR receiver configuration [61].

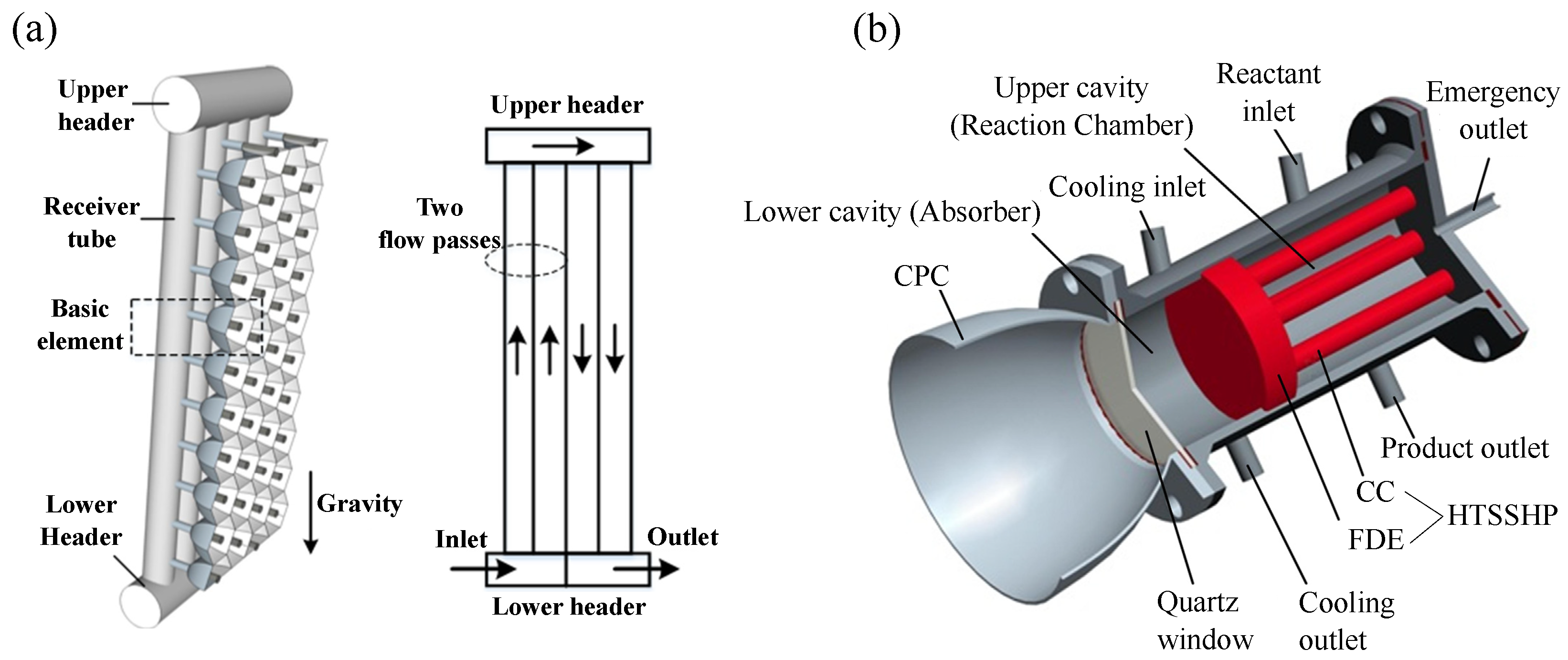

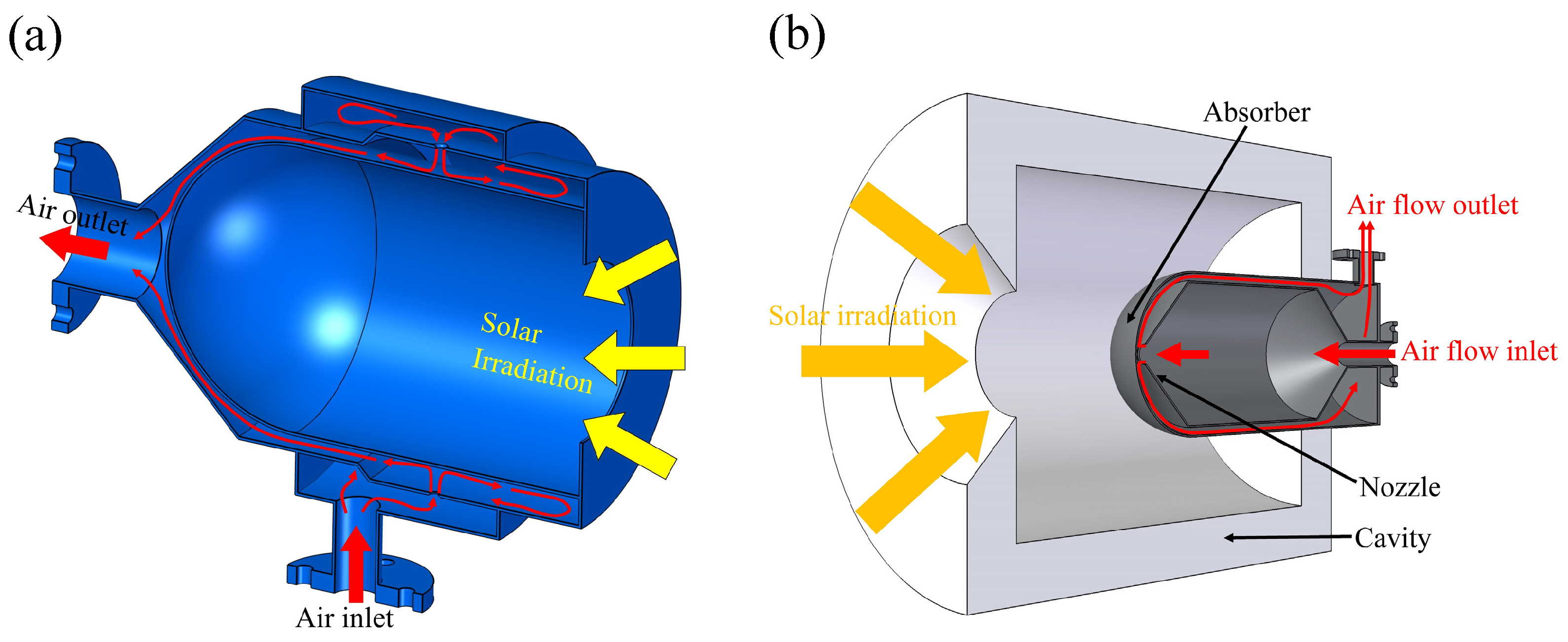

2.2.3. Impinging Receivers

This kind of solar receiver is conformed of a metallic cavity where the sunbeams arrive to heat up the surface. The thermal energy is transferred by conduction to the cavity’s inner wall, where a fluid is forced to flow. At the time that the fluid is absorbing the heat, the cavity inner wall is cooled down, avoiding damage (Figure 9a). Wang et al. [42] carefully analyzed the performance of an impinging solar receiver whose internal cavity was made of stainless steel. The receiver withstands temperatures up to 1150 °C under atmospheric conditions. The measured thermal efficiency ranged from 81.5% to almost 88%, depending on the radiative flux and the effective cavity diameter. Later, a new concept of impinging receivers was developed. Instead of following a radial configuration, where the absorbing fluid cylindrically surrounded the impingement cavity, an axial configuration was proposed [62] and geometrically optimized [63] (Figure 9b). This axial geometry consists of a refractive cavity that traps solar radiation, acting as a secondary concentrator. In the center of the cavity, a solar absorber made of alloy is placed coaxially. The radiation strikes it, heating it and transferring the thermal energy to the compressed air flowing inside. Some of the advantages of this last configuration include significant cost savings from reducing the amount of high-heat-resistant absorbing material. Furthermore, a simpler configuration reduces manufacturing complexity, thereby further reducing costs [63].

Figure 9.

Two different impinging receivers: (a) radial type; (b) axial type [62].

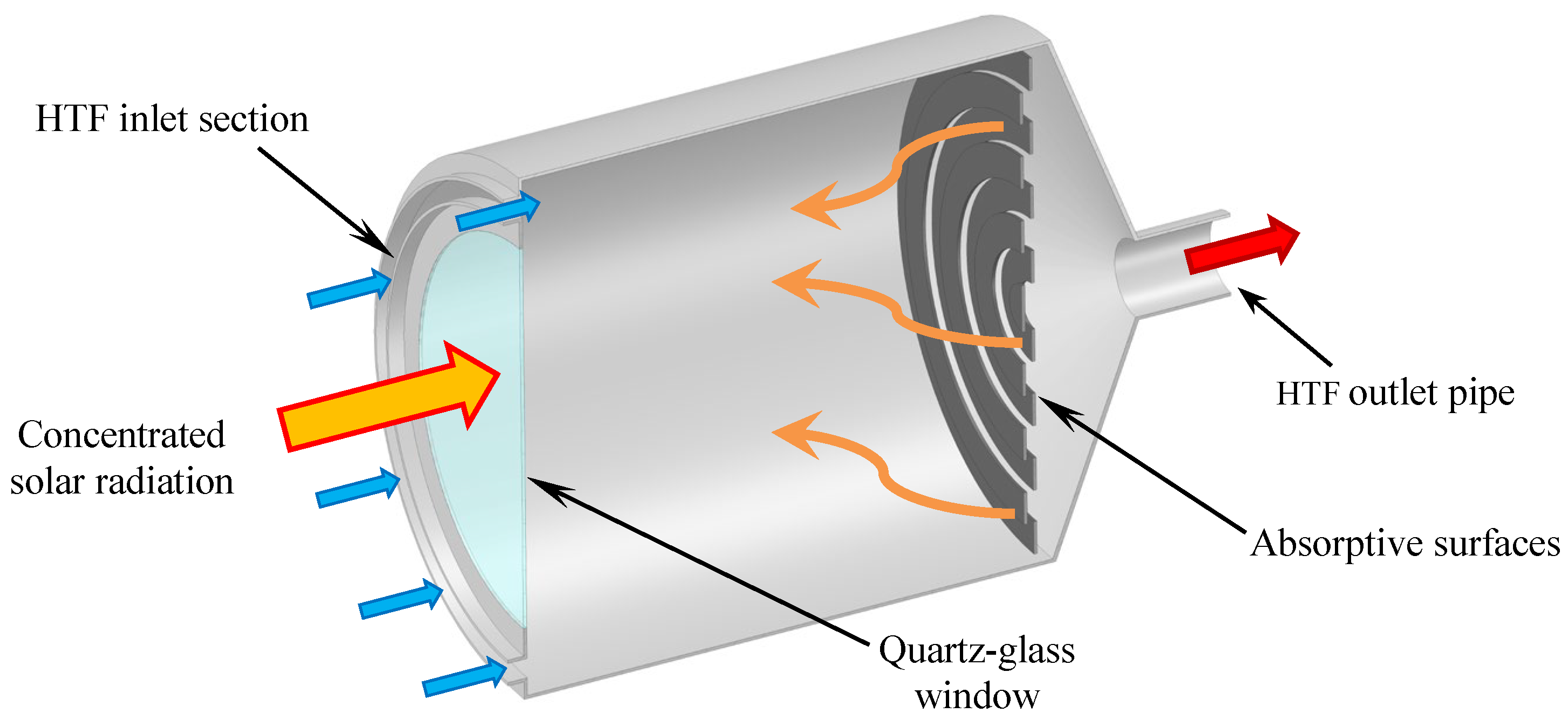

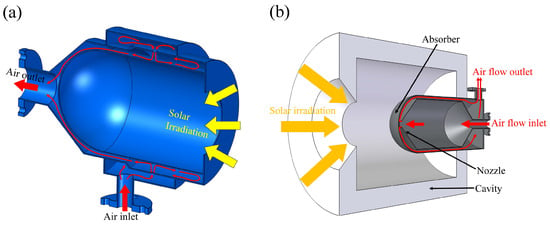

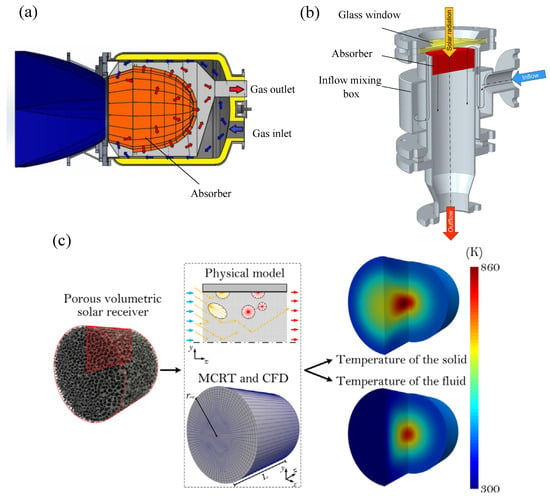

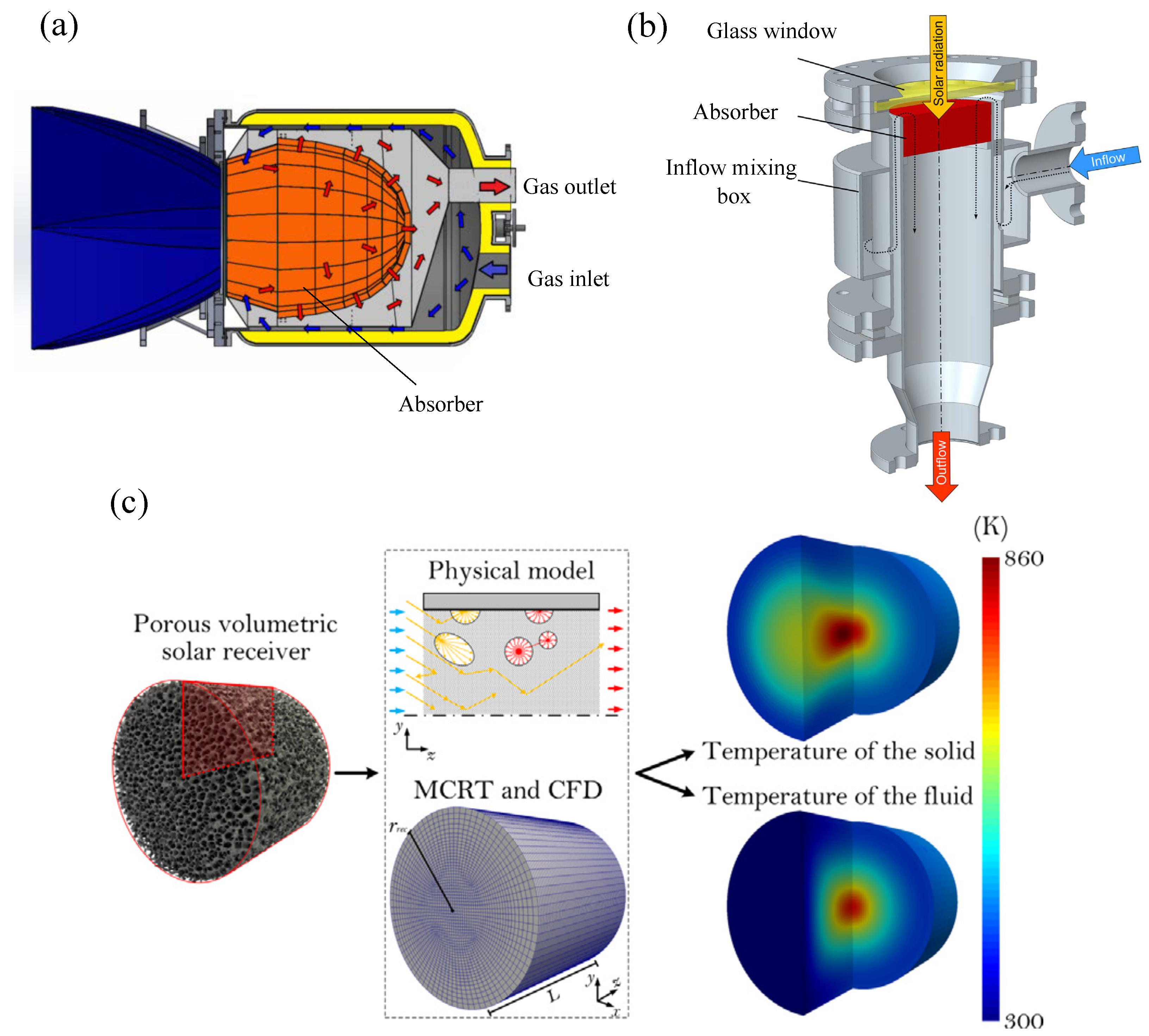

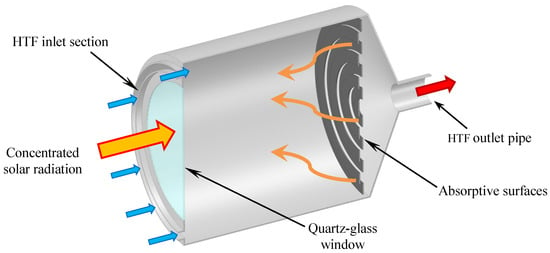

2.2.4. Volumetric Receivers

This type of receiver is characterized by a volumetric medium (usually a metallic reticle or a ceramic porous foam) that absorbs radiation from the Sun. The HTF flows through the pores and absorbs thermal energy, reaching temperatures between 800 °C and 1500 °C [44], depending on the porous foam material. The HTF, which is typically air, can be used either to provide thermal energy to the working fluid (for example, in Rankine cycles) or directly as the working fluid in a gas turbine. This type of receiver has been reported as the best option for Brayton cycle applications, mainly due to its ability to reach high temperatures [14,29,44]. In the latter application, because Brayton cycles are quite sensitive to pressure drops [29,49], the volumetric receiver is pressurized and closed by means of a window [44,64,65]. This receiver concept has been investigated for integration into gas-turbine solar towers, such as SOLUGAS [66]. The Soltrec [67] project is a successful demonstration of high-temperature pressurized volumetric receivers (see Figure 10a).

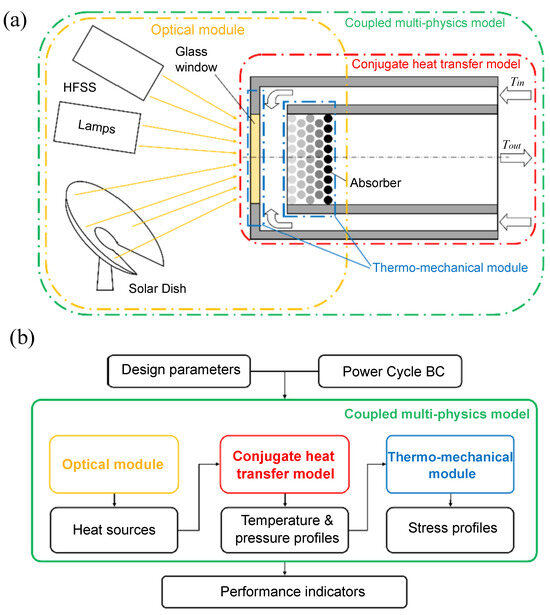

Aichmayer et al. [64,68] devoted several studies to the evaluation of pressurized volumetric receivers integrated into PDC micro-gas turbines (see Figure 10b). The objective was to couple the receiver into the OMSoP (Optimized Microturbine Solar Power) project, developed between 2013 and 2017, in which different European partners collaborated [69]. These authors compared different receiver scales with respect to the reference OMSoP receiver, which reported a thermal efficiency of 86.2%. After scaling and optimization analyses, varying not only geometric but also thermodynamic parameters, such as pressure and temperature, the thermal efficiency ranged from 87.20% to 87.32%. It was concluded that both glass window and absorber stresses and temperatures are the most critical performance indicators related to the materials.

Figure 10.

Volumetric receivers: (a) Soltrec solar receiver; (b) OMSoP solar receiver concept [64,67]; (c) CFD analysis of a porous ceramic medium [70].

Figure 10.

Volumetric receivers: (a) Soltrec solar receiver; (b) OMSoP solar receiver concept [64,67]; (c) CFD analysis of a porous ceramic medium [70].

Zhu et al. [71] tested a volumetric receiver with a metallic porous absorber linked to a PDC, developing later from [65] a simple receiver model able to replicate the experimental results. The receiver consisted of a concentric cylindrical cavity made of stainless steel, a quartz-glass window, and a nickel porous absorber. Air is the HTF tested, entering the receiver through three inlet pipes. The cold air flows throughout the cylinder’s external radius and returns across the center, achieving the highest temperature at the porous medium. The reported receiver thermal efficiency ranged from 74% to 82%, depending on the mean receiver temperature. Recently, García-Ferrero et al. [72] have presented and validated a detailed simulation scheme to account for all realistic losses in the receiver, yielding temperature profiles during receiver operation and all heat flows with relatively low computational effort. A metallic absorber was considered.

Significant efforts have been made to optimize the porous medium to increase receiver efficiency. Barreto et al. [70] measured and modeled the thermal performance of a SiC ceramic porous medium by means of Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) (see Figure 10c). They considered phenomena including the concentration of solar radiation, its propagation and absorption, and the flow of the HTF through the porous structure, along with heat exchange between the solid structure and the HTF. The study showed that thermal efficiency (reported in 85%) strongly depends on the porosity and pore diameter.

Ávila-Marín et al. [73] studied the concept of a “gradual decreasing porosity absorber”, which allows solar radiation to travel deeper inside the absorber. Therefore, the maximum temperature occurs farther from the porous medium’s nucleus. Another advantage of this gradual porosity is the potential to reduce the frontal surface, thereby decreasing front thermal losses. A set of meshes with different porosities was placed in series, acting as a single volumetric absorber. Alloy 310 was selected because of its high-temperature resistance. The results reported absorbing efficiencies of 78–89% for the different combinations of meshes. The simpler design, lower weight, and reduced thickness were claimed as the main advantages of this gradual porosity absorber.

Zaversky et al. [74] introduced a dimensionless number to easily describe the volumetric effect. This phenomenon relates to steady-state heat transfer: although the frontal part of the solar receiver faces the solar radiation, it has a lower temperature than the gas at the outlet of the absorber. This is due to the predominant radiative and convective (HTF flow) cooling mechanisms accounting within the porous medium. The dimensionless number Z is the ratio of the solar power absorbed to the total absorber cooling power. It can also be viewed as an indicator of the temperature profile along the absorber length. If , it means that, locally, the power from solar radiation and the heat dissipation are equal, with the porous medium temperature constant along the depth axis. However, if , then the cooling of the solid medium is faster than the solar power absorption, allowing the solar radiation to go deeper into the absorber for compensating the energy balance (the solar energy must be completely dissipated within the absorber volume). Zaversky et al. [74] concluded that a Z indicator below 1 is a necessary condition to achieve maximum thermal efficiency, but it is not sufficient by itself. It only provides information on the relationship between the specific flux density and the outlet temperature; however, geometrical parameters (porosity, pore size, etc.) should also be considered when designing volumetric receivers. However, it must be mentioned that other authors [75] deny that the volumetric effect is achievable under real-world conditions. Zaversky et al. [74] claims that the issue is to design a suitable experimental setup with non-invasive temperature measurements.

2.2.5. Absorbing Gas Receivers

Absorbing gas receivers constitute a new concept, based on the properties of certain molecular gases that absorb a large share of infrared thermal radiation. This principle is similar to the “greenhouse effect”. A black surface inside the cavity is stroked by sunbeam radiation that is re-emitted and absorbed by the gas. Thus, the gas is heated up because of the absorption, acting as the HTF (see Figure 11). Ambrosetti et al. [49] proposed that concept within their work, modeling the receiver by using the spectral line-by-line Monte-Carlo Ray Tracer method. The geometry analyzed was a 2D cylindrical cavity, with the HTF treated as inviscid and free of buoyancy effects. Conduction and convection are neglected, and radiation is the primary heat transfer mechanism considered. Ambrosetti et al. simulated two receiver sizes (16 m diameter, operating at 1 bar and 1.6 m diameter, operating at 10 bar). The large-scale windowless receiver reported thermal efficiencies between 0.90 and 0.78 at outlet temperatures of 1100 to 2000 K. When comparing the windowed cases, although they are always 2.5% below the windowless case, higher-pressure operating conditions lead to an increase of about 1% in thermal efficiency. The authors conclude that, compared with volumetric receivers employing a ceramic porous medium, the receiver concept they proposed is generally simpler in architecture. Some of the challenging issues would be the windowed configuration for shielding, the use of adequate materials able to withstand up to 2000 K, and the oxidation by steam and CO2. Moreover, this kind of receiver could be difficult to integrate into a PDC due to the large volume of gas necessary for operation.

Figure 11.

Scheme of the absorbing gas receiver working principle [49,76].

2.2.6. Methodologies

Regarding the methodologies employed for simulating the receivers, Ávila-Marín et al. [75] reviewed the techniques for simulating volumetric absorbers. Nonetheless, such techniques, although with some modifications, can also be employed in other receiver configurations (impinging and tubular receivers [42,48]). The methods, according to [75], can be classified into “detailed simulation” or “homogeneous equivalent”. The first approach is the most realistic, since the governing equations are solved precisely in each region of the selected mesh (at a high computational cost). It always employs CFD. The “homogeneous equivalent” method employs semi-empirical terms to simulate heat transfer processes within a porous medium assumed to have homogeneous properties. Moreover, the model can be one-dimensional (low computational cost) and consider only changes in the axial direction, or CFD-based, which requires specialized software. Some examples of CFD software are ANSYS FLUENT® [77] or SolidWorks Flow Simulation [78]. To account for thermal equilibrium, the model can consider a Local Thermal Equilibrium, where the solid and HTF have the same temperature, or a Local Non-Thermal Equilibrium, where heat transfer coefficients are used to model thermal exchange between the HTF and the solid medium.

Table 3 summarizes the main results of this subsection. Concerning the receiver, existing studies suggest that its design must be adjusted mainly to the geometric configuration of the concentrator and, in particular, to the temperatures involved in the overall system. These high temperatures are closely related to significant heat losses due to convection and radiation. To avoid this problem, the incorporation of a TES (at least in the short term) with high-temperature phase change materials (PCMs) inside the receiver appears to be an effective solution [2], but at the expense of the complexity and cost of the hybrid system. Regarding the HTFs, water is the most widely used due to its low cost and availability, and air, thermal oil, and molten salts are also commonly considered. The most recent studies have analyzed the influence of nanofluids as promising HTFs due to their advantageous thermophysical properties. Their use improves the overall thermal efficiency of the system but presents additional problems associated with synthesis and environmental costs linked to possible toxicity risks. An excellent summary and very valuable and detailed information on the effect of different HTFs on various receiver geometries and the influence of the mass flow rates are shown in the work by Vishnu [26] (see Tables 3 and 4 of this work, respectively).

Table 3.

Summary of the solar receivers reviewed in this work. PCU refers to Power Conversion Unit and CTS to Central Tower System.

2.3. Thermodynamic Cycles and Working Fluids

As mentioned in Section 1, the first concept of a “solar engine” worked with the Stirling cycle for generating mechanical energy. However, in the last decade, MGTs operating in a Brayton-like cycle have also been considered a promising option due to their versatility for hybrid configurations, storage options or lower mechanical complexity.

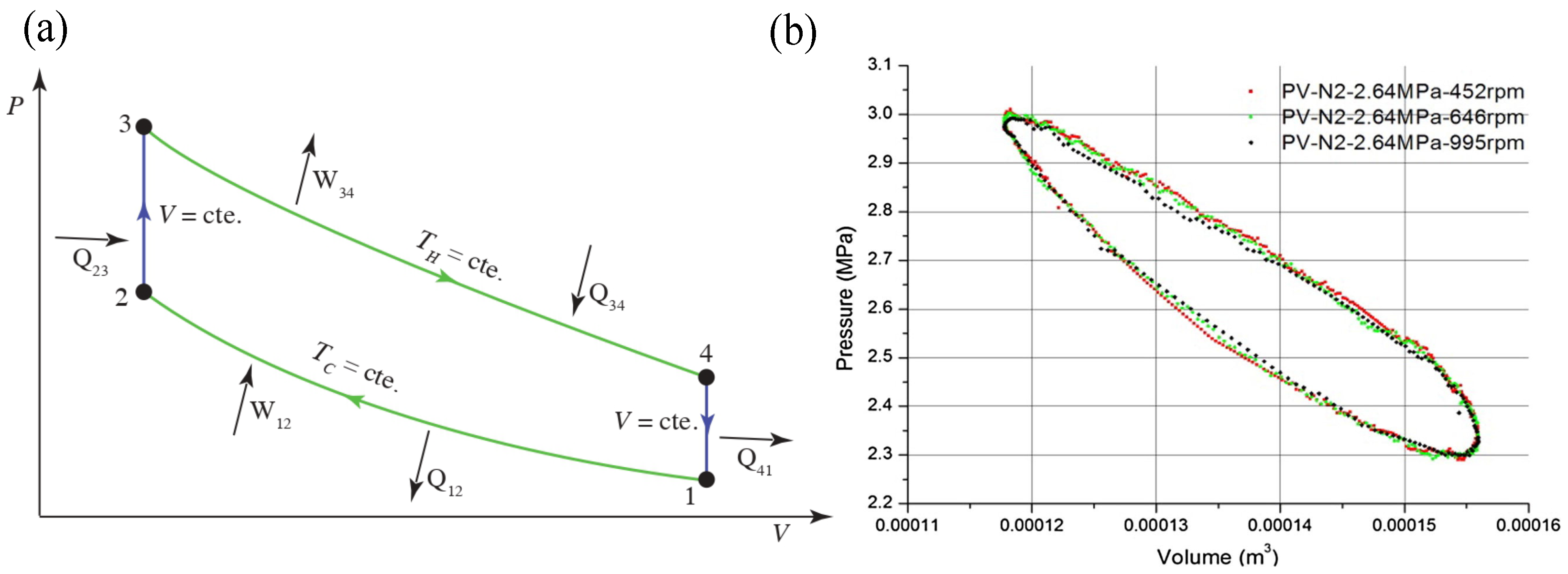

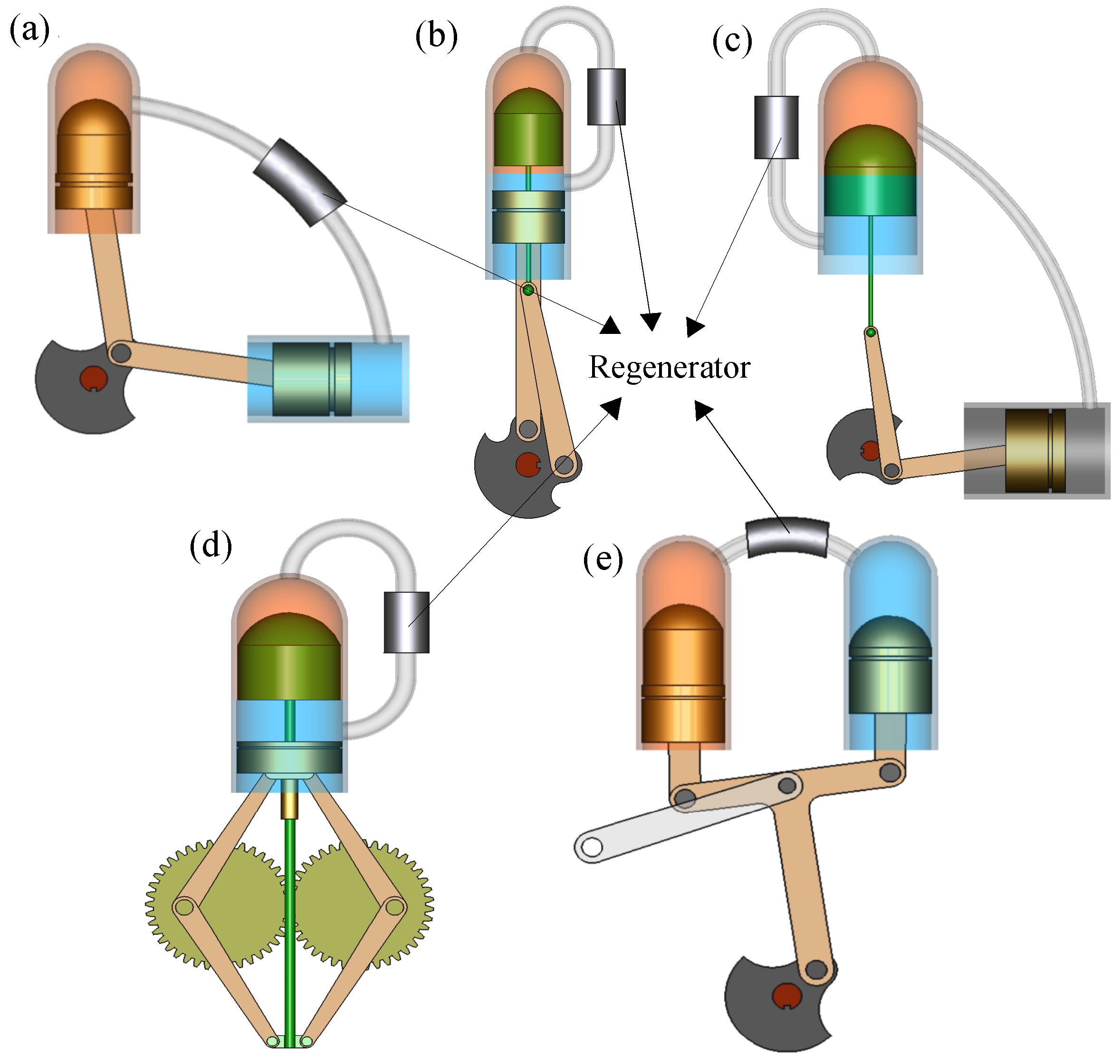

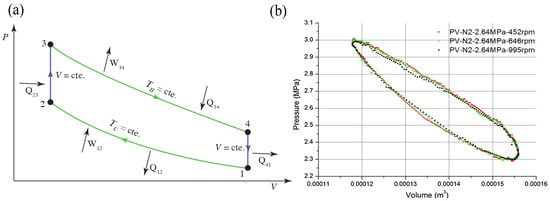

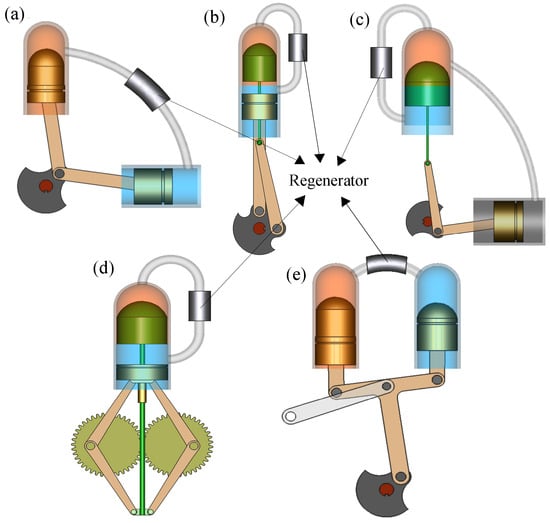

2.3.1. Stirling Power Cycles

The working principle of a Stirling engine relies on the cyclic expansion and compression of a gas, between two thermal sources at different temperatures, to turn thermal energy into mechanical work [79]. Theoretically, the thermal efficiency of a Stirling cycle is quite close to Carnot efficiency, but the actual Stirling cycle presents energy losses, heat transfer resistance or gas leakage that deviates the cycle from the ideal one [80]. The diagrams corresponding to ideal and real cycles are presented in Figure 12. The Stirling cycle (see Figure 12a) consists of two isochoric processes (process 2–3, heat input, and process 4–1, heat release) and two isothermal processes (process 1–2, compression, and process 3–4, expansion of the working piston). The cycle can include a regenerator, which helps to keep the high temperature of the expanded gas and returns it after the compression phase. There exist different kinds of Stirling engines, depending on the arrangement of the expansion chambers and the working gas flow configuration (see Figure 13) [12,81]. , and types count with a crank drive. While and configurations have two pistons, the -type has just one piston integrated with the displacer within the same cylinder. There is another version of -type Stirling engine in which the crank is replaced by a rhombic drive (see Figure 13d), which provides lower side thrust and more silent operation [82]. Finally, Ross yoke -type configuration (see Figure 13e) allows a more efficient and compact design because it minimizes the lateral forces acting on the piston and corrects the phase difference between the moving parts [83].

Figure 12.

Stirling cycle diagram: (a) Ideal cycle, (b) Real cycle using N2 as working fluid [80].

Figure 13.

Different kinetic Stirling engines: (a) -type, (b) -type, (c) -type, (d) Rhombic drive -type and (e) Ross yoke -type. Adapted from [81].

Those previous examples are considered “kinetic” Stirling engines since they are driven by a kinetic mechanism. However, there exist other variants beyond kinetic models: thermoacoustic Stirling engines, where the resonance of the acoustic tubes drives the working fluid to make it flow through the regenerator; free-piston Stirling engines, where appropriate springs are linked to the working piston being self-adapted to the required conditions, and finally, liquid pistons Stirling engines, where the pistons are replaced by a liquid column, displacing the working gas between the hot and cold zones [5].

As for working fluids, air, helium, and hydrogen are the most commonly used gases in Stirling cycles [82]. Ni et al. [80] performed a comparison between helium and nitrogen, working under the same conditions, concluding that helium presented slightly higher power output and efficiency (8.94% compared to 8.63% efficiency reported by nitrogen). However, helium had larger heat transfer losses at the regenerator and larger leakage losses, which were compensated by its higher heat conductivity and lower viscosity compared to nitrogen. Stirling engines have the capability to use a wide range of heat sources: fuel, geothermal, waste heat, biomass, and of course solar power [5,12].

In Stirling solar dishes, the heat source is the concentrated radiation on the focal point, where the Stirling engine is placed. The hot space of the Stirling engine is usually surrounded by tubular pipes carrying the HTF to heat up the working gas [80]. Stirling engines have been preferred for solar dish application because of their high efficiencies (approximately 40% of thermal-to-mechanical efficiency) and potential for long-term operation [79]. Some of the main drawbacks Stirling engines have when being applied to solar dishes are the moderate temperatures they can achieve (ranging between 600 °C and 800 °C for helium and nitrogen) and the limitations regarding hybridization [79]. The mechanical complexity and maintenance that Stirling engines require represent another shortcoming when compared with gas turbines [84,85].

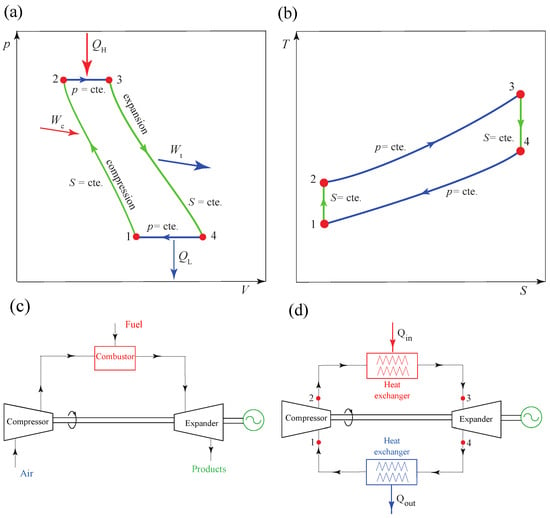

2.3.2. Brayton Cycles–Micro-Gas Turbines (MGTs)

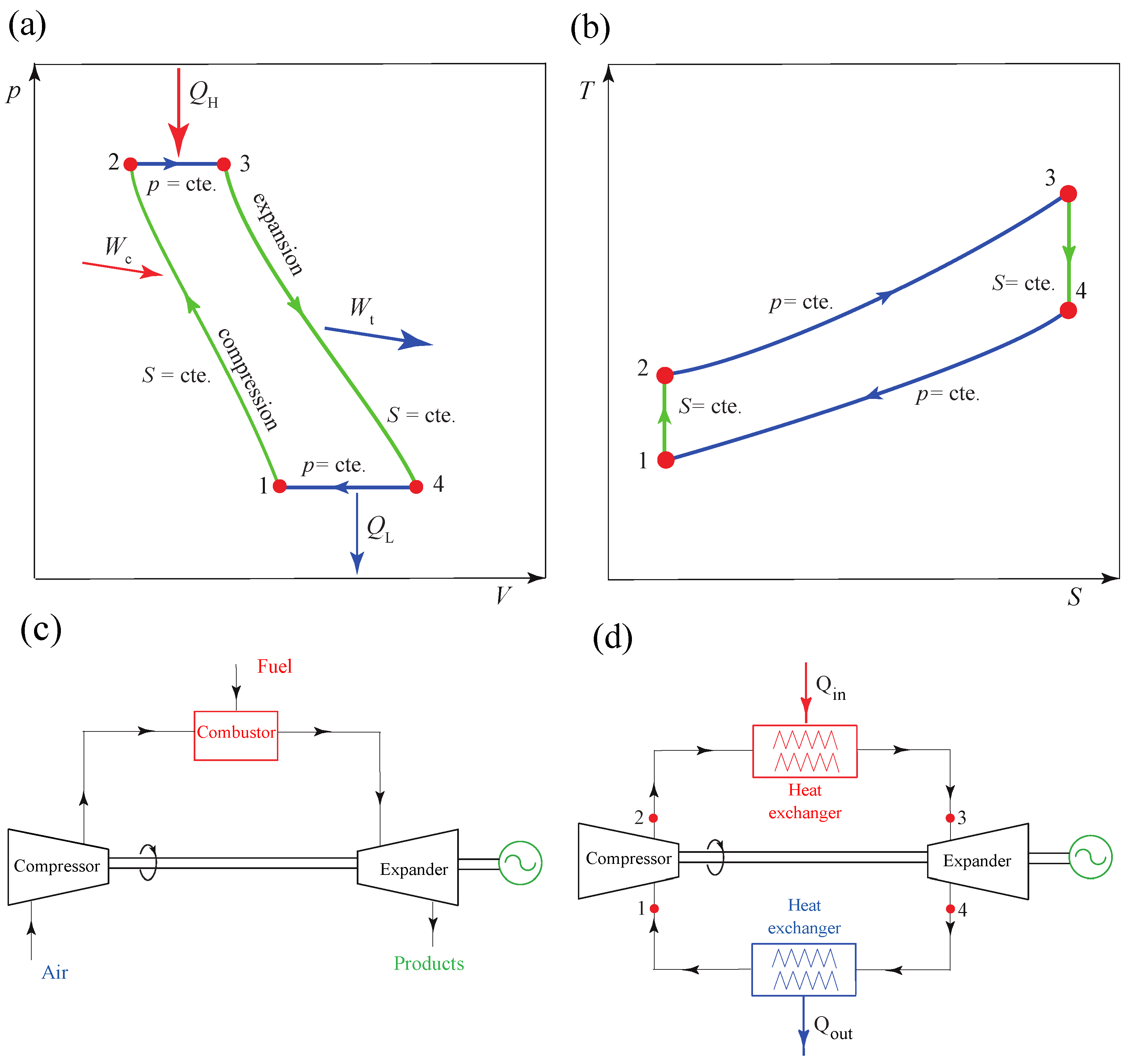

Gas turbines are based on the Brayton cycle, which converts thermal energy into mechanical energy. As presented in Figure 14a,b, the ideal cycle consists of an adiabatic gas compression, an isobaric heat absorption, an adiabatic expansion in the turbine, and finally an isobaric cooling. Conventional real gas turbines comprise a compressor, a heat source, and an expander. In the open-cycle (see Figure 14c, isobaric cooling is achieved by expelling the air to the ambient. Another configuration includes a heat exchanger with the ambient, closing the cycle (see Figure 14d). The fuel used in the combustor can be kerosene, propane, or natural gas. However, the use of biogas is gaining attention [86], as it is considered a net-zero CO2 emissions fuel. To further increase the cycle efficiency, a recuperator is usually placed connecting the compressor and the expander outlets, aiming to preheat the working fluid, which can attain temperatures up to 900–1000 °C [87].

Figure 14.

Brayton cycle: (a) Reversible diagram, (b) Reversible diagram, (c) Basic open-cycle configuration, and (d) Closed-cycle configuration.

In solar Brayton cycles, the combustor is replaced by the solar receiver as the primary heat source, although another combustor/heat exchanger could be placed in series to enhance the thermal energy provided by this hybridized configuration. Solar-powered micro-gas turbines (MGTs) have been considered a potentially low-maintenance alternative to Stirling engines, leveraging existing gas turbine technology. They can operate in harsh environments like deserts or sea sides without needing deep maintenance [88]. The main bottleneck for this technology is the adaptation of suitable small turbines for solar applications [79]. The MGT can be applied to small solar towers (if the power output required is above 50 kWe) while parabolic solar dishes are limited to power outputs up to 50 kWe [15].

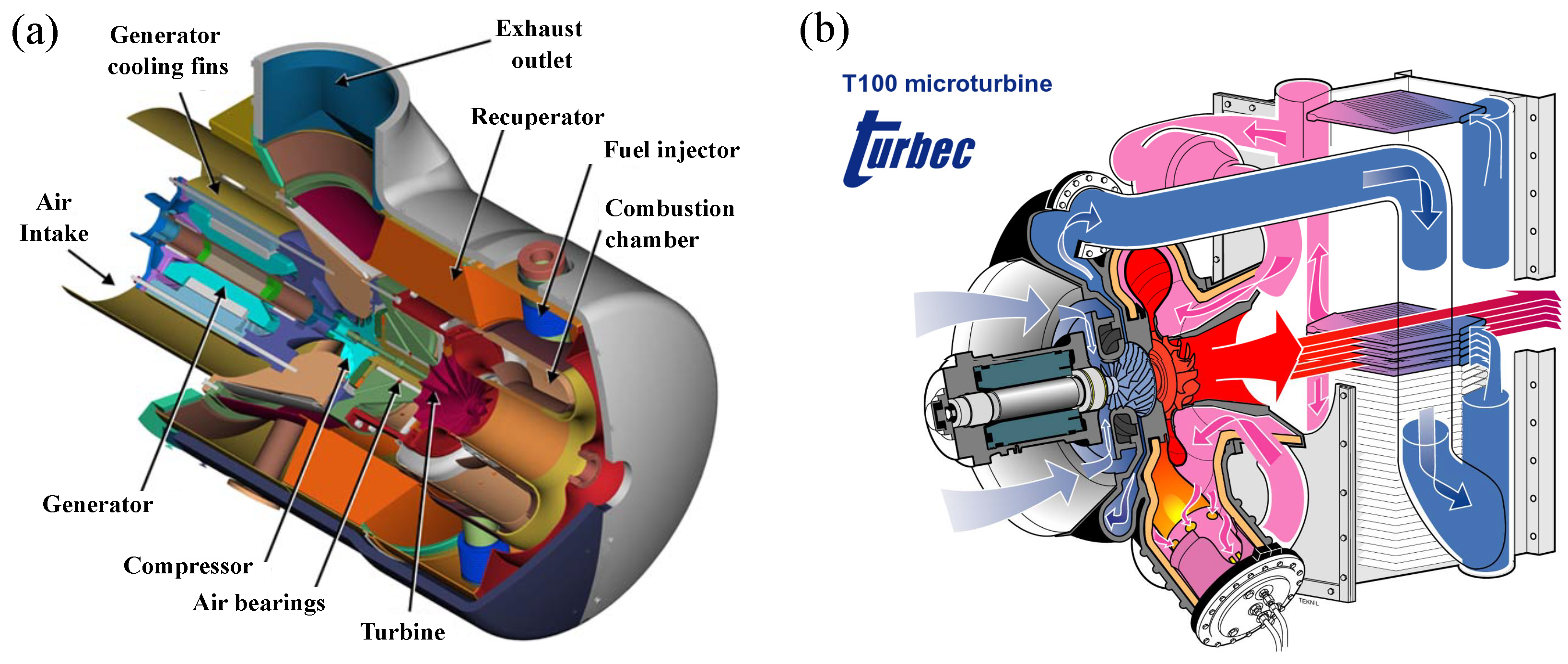

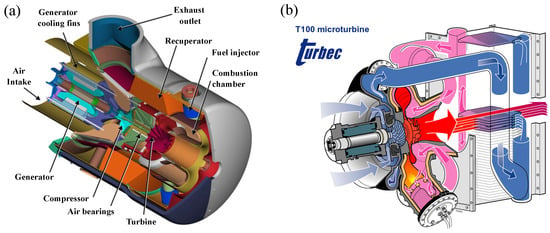

Among the working fluids, air is considered to offer numerous advantages, such as on-site availability, low supply and maintenance costs, non-toxicity, and no environmental problems [87]. From an overall perspective, solarized open-cycle MGT operating with air is one of the best configurations for PDC [31], with power block efficiencies ranging from 27% to 37% (at on-design conditions). Closed-cycle gas turbines, in the range of MW, have been demonstrated to increase their efficiency by using other working fluids such as helium [89,90] or even sCO2, which is a vanguard and interesting topic today [91]. However, to the authors’ knowledge, there is a lack of thermodynamic analysis dealing with different working fluids for a small-scale solarized MGT (in the range of 50 kWe or below). Most studies devoted to MGT over such a range of energy outputs use air as the working fluid [11,31,92,93,94]. Some commercial MGTs are presented in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

MGT commercial models: (a) Capstone C30, 30 kWe at nominal conditions [95]; (b) Turbec T100, 100 kWe and 170 kWt at nominal conditions [96].

Recently, Cockcroft and Le Roux [97,98] have analyzed the influence of pressure losses in solarized Brayton MGTs by means of a new concept of multi-dish systems on small scales. These authors compare recuperated and non-recuperated parallel-flow solar cycles, obtaining a significant reduction in pressure losses while increasing efficiency.

2.3.3. Methodologies

Regarding the methodology for simulating thermodynamic cycles, Barreto and Canhoto [12] summarize the tools available for simulating a Stirling engine. Among them, the ideal Stirling cycle can be simulated under the assumption of an ideal working gas, perfectly effective heat transfer, uniform temperature distribution, and ideal adiabatic processes. A step further would be to consider heat transfer coefficients in the expansion and compression spaces with constant wall temperature (semi-adiabatic analysis), non-ideal regenerative processes, and pressure losses. Finally, CFD models are the most sophisticated ones. They are also employed for improving the accuracy in the numerical analysis of the Stirling engines [12]. Mass, momentum, and energy conservation are solved locally using a very fine discretization grid. The main drawback of CFD is the significant computational effort required by the specific software.

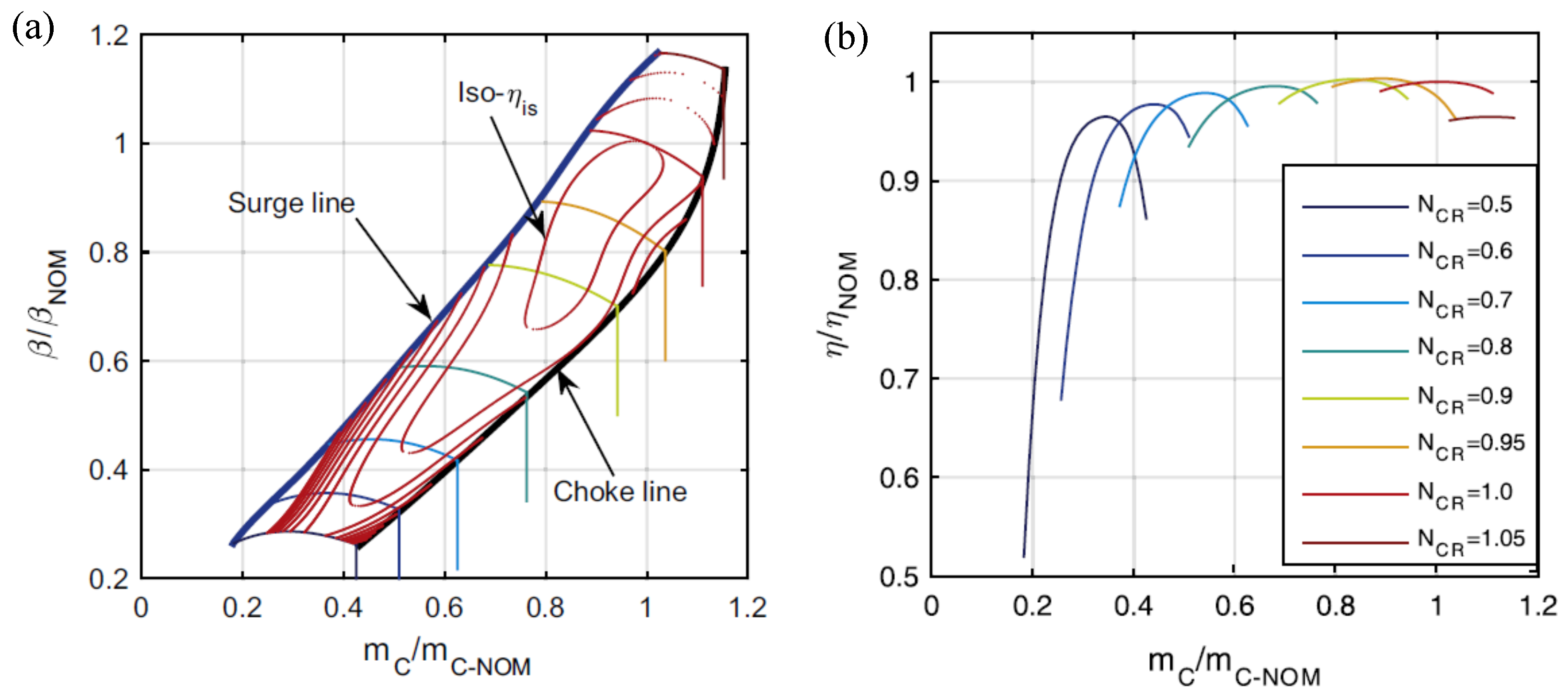

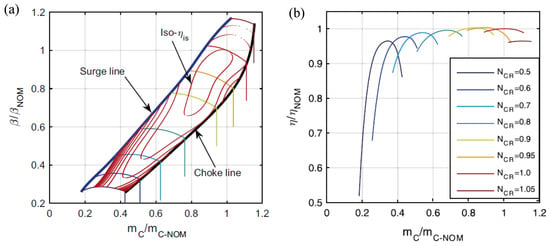

MGTs can be analytically studied using nodal models based on mass and energy balance equations, written in terms of enthalpies, temperatures, and pressure drops. For analyzing the turbine at off-design conditions, operational maps [31,87] are employed (see Figure 16). They describe how the compression and expansion ratios and the rotor speed change with the mass flow, which varies with external conditions. Moreover, dynamic studies are necessary due to delayed responses to external disturbances [99], caused by the metal matrix’s thermal inertia. In solarized MGT without a backup system, the solar dish collector, joined to the sudden variations in DNI and weather, cause the response to be further delayed. Finally, there exists dedicated software such as GasTurb [100], Thermoflex® [101] and TRNSYS [102].

Figure 16.

Example of operational maps employed in the analysis of a MGT [31]. (a) stands for the compressor pressure ratio, is the corrected working fluid mass flow, and (b) is the compressor isoentropic efficiency. ‘NOM’ refers to nominal (on-design) conditions, and NCR is the off-design compressor shaft speed ratio to the nominal one.

Table 4 summarizes the main results on the analyzed power blocks. The following comments are pertinent at this point. The sealing technology of the kinetic Stirling engine remains difficult to meet the long-term operating requirements. Selected working fluid must be carefully checked to ensure minimizing pressure drops to get the desired and reliable power output while avoiding high cost issues. In this context, the supercritical carbon dioxide (sCO2) turbines, with and without reheating, seem to be appropriate to achieve the higher temperatures needed for distributed solar thermal applications. Recent studies on new power blocks based on semiconductor materials have been reported taking advantage of the solar thermionic generation (TIG), thermoelectric generation (TEG), and thermal photovoltaic (TPV) properties. However, doubts on the thermal stability of semiconductor materials in an environment with continuous radiation fluctuations must also be considered [27,28].

Table 4.

Summary of the most common power block types linked to a PDC: Stirling and micro-gas turbines (MGTs).

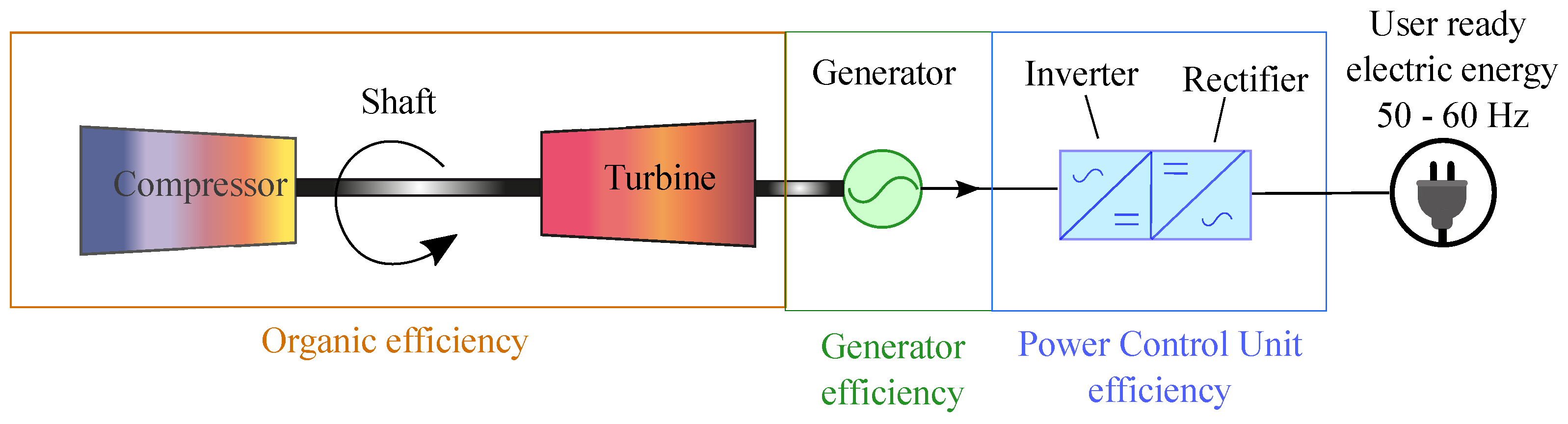

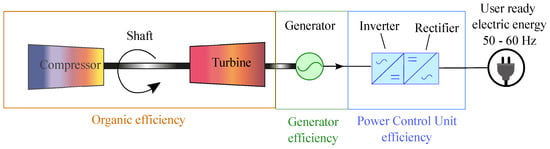

2.4. Other Elements

Some other components are required to convert the mechanical energy generated by the thermal engine into electricity if that is the final energy the user requires. For solar dishes coupled to Stirling engines, Barreto [12] considers a permanent-magnet synchronous machine with a DC output of 300 V and a speed of 2300 rpm. In Brayton-cycle MGT, the high rotating speed of the compressor-expander turbomachinery inevitably leads to a high frequency AC output at the generator [31]. This electrical energy is converted to DC by a rectifier and then turned back into AC by an inverter, meeting the grid AC frequency (50 or 60 Hz). Giostri et al. [31] report the different efficiencies assigned to each of the components involved in this process, which could well vary according to the partial load operation conditions. The reported efficiencies for the on-design point are 96% for the generator and the power control unit (rectifier and inverter). The most common configuration of this rotatory turbomachine has only one shaft coupling the compressor and the expander movement. This means that a share of the total power produced in the expander is used to drive the compressor. Thus, it is necessary to consider an organic efficiency, defined as the relation between the shaft and the turbine rotor powers, with values around 98% [31]. In Figure 17, a scheme of all the electrical elements mentioned above is presented.

Figure 17.

Scheme of the elements involved in the conversion of the MGT mechanical energy into electricity. Adapted from [31].

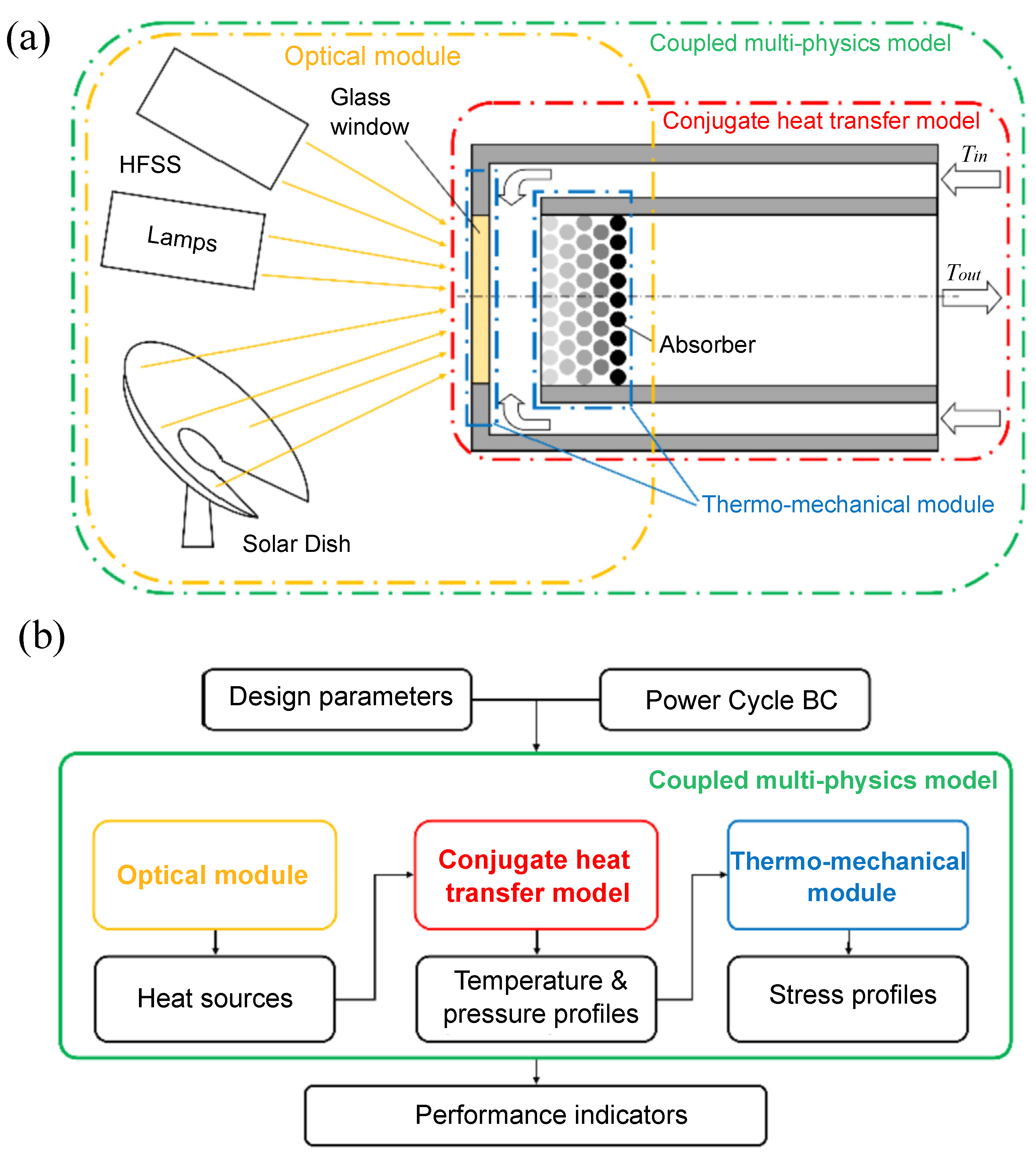

2.5. Component Integration and System Optimization

After modeling each component, it is necessary to integrate all components to obtain a global view of the system’s performance. It is of major importance to conduct this kind of study, as it provides useful information and helps identify the plant’s main bottlenecks. The integration of the system mainly consists in carefully selecting the inputs for each sub-model, and sequentially solving the equations associated with them, obtaining the corresponding outputs. Multi-physics-specific software, such as COMSOL [37], can be used to simulate subsystems using advanced numerical methods. Aichmayer et al. [47] performed a multi-physics analysis, coupling a parabolic solar collector and a volumetric receiver. The model and the flowchart that the authors followed for integrating the system are depicted in Figure 18.

Figure 18.

Integrated multi-physics model: (a) scheme and (b) flowchart [47].

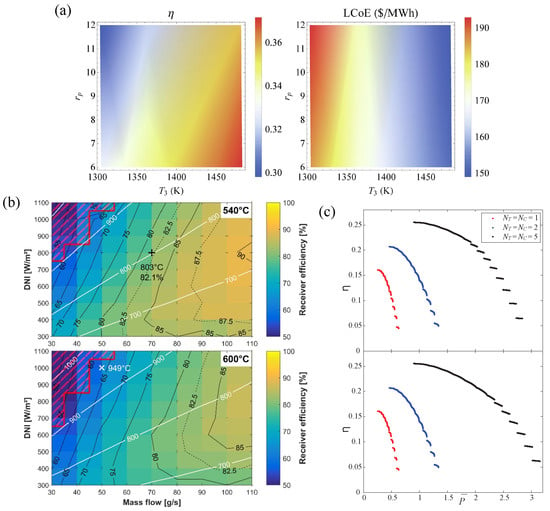

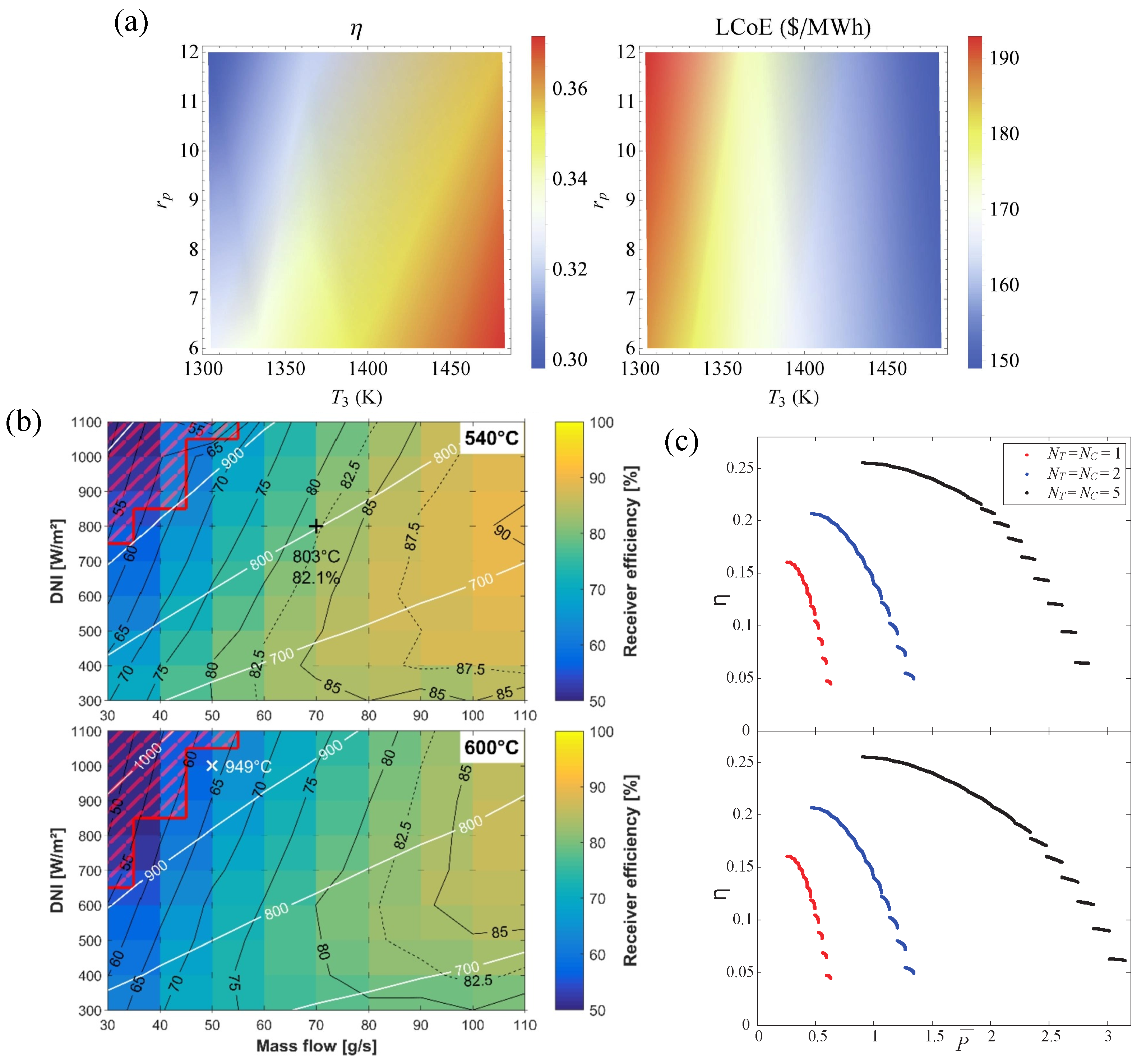

The next step after coupling the system is to try to optimize it. One option for starting the system optimization is to perform a sensitivity analysis. This approach involves a multi-parametric evaluation to determine whether some characteristic parameters exhibit a maximum or minimum as a function of others. For example, Merchán et al. [103] perform a two-dimensional sensitivity analysis for a Brayton-like Solar Tower plant, identifying how the overall efficiency and the Levelized Cost of Electricity (LCoE) changed as a function of the compressor pressure ratio and the turbine inlet temperature (Figure 19a). Aichmayer et al. [47] studied how the receiver efficiency changed as a function of air mass flow and DNI, for different receiver inlet temperatures (Figure 19b).

Finally, it is worth briefly explaining multi-objective optimization, which is often used to jointly optimize two (or more) objective functions [104,105]. For thermal engines, these functions are commonly the overall plant efficiency and the net power output [106], but also techno-economic ones can be selected [13,14,107]. The Multi-Objective Optimization Problem (MOOP) seeks to find the Pareto Front (PF) of the given functions. The solutions obtained represent the different trade-offs between conflicting objectives, as improving one objective function degrades another. In Figure 19c, some examples of PF are exposed. Specifically, the overall efficiency, , and the dimensionless power output, , are the two objective functions optimized attending to the adiabatic coefficient of the working gas, , and the number of expanders and turbines of the multi-stage Brayton-cycle studied.

Due to the close and necessary connection among the different components, and beyond the elected MOOP, the importance of the influence of the location-dependent factors for any particular PDC should be stressed: variable incident DNI (with direct effects on the concentration ratio), ambient temperature (a key factor in balancing convective effects and radiation losses), and wind speed (as this affects optical and thermal losses with significant influence on aerodynamics). In climates with high variability factors, as abrupt fluctuations, solar flux could provoke thermal stress in the receiver (and thus in the power block). Concerning variable DNI, an appropriate balance between the dish and receiver sizes has been proposed according to the statistical distribution of the local DNI: in areas with low average DNI, the strategy is to find geometries with higher concentration while high variability areas benefit from receivers with high thermal inertia or hybridized with PCM material. For tropical regions with intermittent cloud cover, tracking with predictive algorithms, and incorporating both local and operational constraints can aid to reduce losses due to temporary misalignment and to achieve improvements in the optical and thermal efficiencies (and indeed, in the economic metrics) [108].

Figure 19.

Optimization methods: (a) Sensitivity analysis of a Brayton-like Solar Tower [103]; (b) Sensitivity analysis of a solar receiver integrated into a PDC [47]; (c) Multi-objective optimization of a multi-stage Brayton turbine [106].

Figure 19.

Optimization methods: (a) Sensitivity analysis of a Brayton-like Solar Tower [103]; (b) Sensitivity analysis of a solar receiver integrated into a PDC [47]; (c) Multi-objective optimization of a multi-stage Brayton turbine [106].

3. PDC-Related Projects

In this section, some projects devoted to the development of PDC technology for different applications are presented. All of them focuses on MGT as power block unit.

3.1. OMSoP Project

The most remarkable European project dealing with this topic was the so-called Optimized Microturbine Solar Power system (OMSoP) [69,109]. Started in 2013 and coordinated by the City University of London (UK), it was the first proof-of-concept of a MGT integrated into a PDC. The consortium counted with another seven partners: four in Italy (Universita degli Studi Roma Tre, Agenzia Nazionale per le Nuove Technologie, l’Energia e lo Sviluppo Economico Sostenibile (ENEA) and Innova Energy Solutions SPA), two in Sweden (Compower AB and KTH), one in Spain (University of Seville), and one in Belgium (European Turbine Network). A 10 kWe PDC-MGT prototype was installed in the ENEA Cascaccia Centre. The main objective of this project was to develop a system capable of producing energy for domestic and small-scale applications. The results demonstrated that this technology is feasible not only technically but also economically. The minimum LCoE achieved was about 0.15 €/kWhe, so this system is likely to compete with dish-Stirling, whose LCoE is above 0.20 €/kWhe [110]. The project ended in 2017, providing new knowledge and experience that paved the way for reducing the risk of this technology.

3.2. SolGATS Project

By March 2017, a collaborative research and development (R&D) project managed by the City University of London and Zhejiang University in China began to be developed [111]. It was funded by the UK Research and Innovation Organization and two industrial partners: Samad Power Ltd. and SUPCON companies. The project was intended to analyze a solarized MGT integrated into a PDC with TES. According to Iaria et al. [112], the thermal storage analysed was designed to smooth solar irradiance fluctuations, supplying energy for about 1 h. The TES considered within [112] consisted of a ceramic material with a honeycomb structure with hot air crossing it. The authors demonstrated that, for a strong DNI decrease (from 900 W/m2 to 200 W/m2), the TES system could maintain the power output in 7 kWe (nominal power output was 8 kWe). The project pursued the development of a Thermo-Chemical Energy Storage (TCES) for tri-generation, i.e., the production of electricity, heating, and cooling. Although the project finished in June 2019, the partners continued collaborating and published several papers on this topic [113,114]. The TCES selected was the cobalt/cobaltous oxide redox cycle, in which air serves as both the reaction medium and the HTF. Both studies [113,114] implemented control strategies for the system, achieving successful results and enabling more stable, safe, and efficient system operation.

3.3. SOLMIDEFF Project

SOLMIDEFF (SOLar micro-gas turbine-driven Desalination for Environmental oFF-grid applications) [115] was a Spanish multidisciplinary project developed between 2019 and 2021. The initiative focused on the development of small-scale water desalination for remote, off-grid locations. Two devices were combined within the same system: a Zero Liquid Discharge (ZLD) unit and a Seawater Reverse Osmosis (SWRO) unit. Both of them were empowered by a solar-MGT that had already delivered positive results from the OMSoP project [115]. Petit et al. [84] analyzed the configuration for this system. They concluded that the most suitable setup would be if the 10 kWe delivered from the solar MGT is split into power surplus (2.52 kWe) and in the treatment of brackish water in a reverse osmosis unit (7.48 kWe). Additionally, the exhaust gases from the MGT, with temperatures above 250 °C, were used in the ZLD unit to treat industrial effluents. The use of biofuel as a backup supply for the solarized MGT was also considered in [84]. The authors concluded that the solar MGT coupled with ZLD would enhance the circular economy of the mining industry, although further research and experimental testing are needed.

3.4. NextMGT Project and European MGT Forum

Some other projects and initiatives, such as the NextMGT European project (developed during the years 2020–2024 and coordinated by St Georges University of London) or the European MGT Forum, are devoted to enhancing and further commercializing MGT technology into the low-carbon economy scenario [116]. Although the initiatives are not directly linked to solar PDC, the MGT is one of the elements that needs to boost its presence in the renewable energy market. The higher the maturity of the MGTs, the easier the integration into solar PDCs will be. Escamilla et al. [117], within the NextMGT project, have analysed the integration of hydrogen and a MGT for renewable energy storage. After analyzing different types of H2 storage (liquified, compressed, in the form of metal hydride), they conclude that this system could compete with other methods of energy storage such as Liquid Air Energy Storage (LAES) and Compressed-Air Energy Storage (CAES). The NextMGT project has partners who have great expertise on this topic since they have previously participated in the above-mentioned projects (OMSoP, SolGATS, and SOLMIDEFF).

The European Micro-gas Turbine Forum (EMGTF) [118] is an updated initiative that each year joins researchers with extensive experience on MGTs. The main goal of this consortium is to foster the commercial development of MGTs for contributing to sustainable clean power generation.

3.5. SOLARGRID Project

SOLARGRID project [119] considers broad objectives related to the analysis of hybrid configurations, including solar thermal and PV with storage for cogeneration purposes and flexible generation of energy. Concerning PDC, the hybridization of solar dishes in the Mediterranean region was investigated using two hybrid parabolic dish systems: the dish-Stirling system at the University of Palermo and the dish-Micro Gas Turbine system at ENEA Casaccia. The findings suggested that hybridizing parabolic dish systems, both Stirling and MGT, with conventional fuels or renewable energies greatly enhances their performance, increasing operational hours and maximizing energy production.

4. Future Prospects

Inherent advantages of the PDCs are high geometric concentration factor, high energy intensity, and high temperatures due to the small local focus of the incoming solar radiation. However they are the least widespread configuration among CSP technologies. In fact, as noted in [9], they amount to only the 0.04% for a total of 129 CSP-projects worldwide and for a total capacity of 3 MW (see Figure 15 in [9]), and according to works [24,25,120], no commercial projects relying on PDC technology are expected in the near future. Therefore, it is not as mature as other CSP technologies (such as parabolic troughs and towers), but it rests in its early stages of commercialization. Additional challenges are should be supported in the integration with TES facilities and/or hybridization layouts. Below, some particular scenarios for future research are briefly listed: they represent promising trends in PDC research that could improve the Technology Readiness Level (TRL), lowering costs and thus allowing wider implementation of PDC systems.

4.1. Solar Receivers and Solar Collectors

As mentioned in Section 2.2, two critical components in the PDC technology are the solar collector and solar receiver. Regarding the solar collector, its efficiency is strongly influenced by materials, aperture area (or diameter), concentrator shape, rim angle, and focal length. Malik et al. [8], after an exhaustive review, claim that solar collectors can be optimized by using silver materials with reflectivity of 97% and rim angles near 45°. The aperture area can only be optimized based on the targeted thermal energy, while the rim angle, tilt angle, and receiver position can be optimized using MCRT software and the Finite Volume Method (FVM).

On the other hand, solar receivers are highly dependent on the geometry and the type of HTF selected. For the targeted application, the solar receiver can be tubular, generally hosting a liquid HTF [121,122], or volumetric [72,123], allowing gases as HTF for high-temperature operation and high thermal performance. Indeed, this goal is strongly dependent of how heat losses can be minimized using coatings, including photonic crystal mirrors [124] or transparent aerogels [125] and suitable nanofluids [126,127] as HTF. Regarding minimizing pressure losses, the novel multi-dish configurations for single-shaft and parallel-flow solar dishes [97,98] achieve, for particular arrangements with low-temperature turbines, efficiencies of 39.6% and a power output of 2.5 kW at a lower pressure ratio of 1.2.

With regard to the energy conversion unit, together with conventional closed Stirling engines, single or multistep closed MGTs still could be a viable option by using in combination with selected working fluids allowing high temperatures under regenerative arrangements. The results of the most recent alternatives based on semiconductor materials and thermochemical reactors still appear to be inconclusive, perhaps influenced by the effects of the non-uniformity of solar radiation [28].

4.2. PDC Scenarios for High Temperature Applications

Nowadays, hybrid and/or CHP configurations are the most appealing PDC scenarios for both medium and high-temperature applications. A combustion chamber integrated into a solar PDC [85], the most conventional PDC hybrid configuration, can be improved when coupled with additional energy sources. In this regard, solar–wind hybrid systems aim to compensate for the intermittency of solar energy by using wind energy to maintain stable operation of the Stirling engine. This can be achieved either by using wind as an additional electrical resource for the micro-grid when the solar source is enough to power the Stirling cycle, or by using wind as an electrical resource in the compression (or pumped) stage of the cycle when the DNI is not sufficient to operate the Stirling cycle, thus preventing drops in pressure and working fluid temperatures. Three concrete but different and representative layouts are the following: Da Silva et al. [128] proposed the integration of wind blades into a dish-Stirling collector, creating a hybrid solar-wind system oriented to the harvesting of solar and wind energy; Shboul et al. [129] performed a design and techno-economic assessment for a new hybrid system with solar dish Stirling engine integrated with a horizontal axis wind turbine for micro-grid power generation. The reported simulated results at design point show a thermal efficiency of 37% with a net output power suitable for operation in terms of costs. The third layout (and the most ambitious) refer a hybrid solar PDC–wind turbine aimed to meet the electric demand of a sustainable multi-family buildings with possible generation of clean hydrogen when an electrolyzer and a hydrogen storage tank are added [130]. By performing sensitivity studies, the viability of the proposal was analyzed in two different locations in Morocco. The findings indicated that the proposed design and configuration are site-dependent due to discrepancies in wind and solar energy potential of the examined locations. Regarding CHP configurations with PDCs can be implemented for several cogeneration and even poly-generation processes. So, Al-Amayreh et al. [131] designed a PDC to provide light to indoor PV panels via optical fibers and domestic water heating. Cost analysis of solar thermal power generators based on parabolic dish and micro-gas turbine including manufacturing, transportation, and installation were reported by Gavagnin et al. [132]; the optimal design and economic analysis of a hybrid solid oxide fuel cell and parabolic solar dish collector, combined cooling, heating and power (CCHP) system used for a large commercial tower was analyzed by Moradi et al. [133]. A six-focus high-concentration photovoltaic-thermal dish system was designed and implemented in [134] obtaining a high geometric concentration ratio of 1733 at each of its six receivers. Water treatment, such as desalination or distillation, is also a growing area of interest at low temperatures due to the forecast freshwater stress. Many research studies [135,136,137,138,139] and also some projects like SOLMIDEFF [115] are focused on purifying wastewater and reusing it in industrial processes or taking seawater for turning it into freshwater. A key point in this issue, as noted in the work by [135], refers to the development of efficient sCO2 Brayton arrangements, able to balance the heat extraction for desalination as the main point to future solar thermal desalination systems.

In thermal energy production and high-temperature scenarios, two innovative applications, such as TES for diverse processes and solar fuels production, are emerging [140]. Although TES is widely integrated into larger-scale CST systems, it is less common to integrate it into PDC. As noted previously, there exist some studies intended to integrate PDC with power cycles in the range of 400 kWe and molten salts TES [107]. Nevertheless, the most widespread configuration for integrating thermal energy storage into solar dishes involves the use of PCM [141,142,143], i.e., solid-to-liquid or liquid-to-gas phase change materials that harness latent heat for energy storage. Besides, TCES (Thermo-Chemical Energy Storage) options are emerging, enabling higher-temperature operation and higher volumetric energy density [144]. Very recently, Palladino et al. [145] have suggested the possible applications of PDC systems as heat generators for seasonal energy storage applications.

Finally, it is worth noting that PDC systems could contribute to the development of new technological routes for producing solar fuels [146,147,148], taking advantage of the available high temperatures at high concentration factors with a reduction of levelized production costs for solar energy conversion to electricity processes. Solarized synthetic fuels and biofuels could be an alternative to achieve a net-zero CO2 emissions system, compared with well-established industrial chemical engineering processes for hydrogen, syngas, diesel, methane, and ammonia, but at high prices and with polluting emissions. In the particular case of hydrogen production, some authors focus on thermo-chemical optimization of the solar cavity receiver to enhance the solar-to-fuel conversion efficiency [149], while others explore electrochemical methods [150] using novel parabolic dish concentrator geometries and PV modules.

5. Conclusions

In closing, compared with other CSP technologies, PDC systems require a smaller land area and due to their modularity, adaptability, and high concentration factors can be a valid option in power generation systems for both isolated units or solar farms. Promising perspectives, such as water treatment, hydrogen production, and the implementation of Phase-Change Materials as TES facilities, together with the adoption of appropriate policies, could aid in addressing existing bottlenecks, such as high costs and the lack of complete life-cycle assessments (LCA), thereby increasing PDC technological maturity.

Indeed, the optimized integration of all subsystem by an LCA methodology is a necessary step, as all of them play a complementary role: collectors and receivers are mutually connected for the attainment of high concentration factors but also the outputs of the power block are highly influenced by the heat transfer fluid, and the thermodynamic cycle or appropriate semiconductor device used in the in the solar-mechanical energy transformation. Additionally, the inclusion of efficient TES system and/or hybridization depend, in last instance, of the temperature at the receiver and, thus, of the concentration factor, which also depend on the real DNI at any elected location. Real-time and integrated optimization methods are thus needed to promote the transition to the commercial deployment of PDCs. Perhaps recent advances in machine learning, and artificial intelligence can be useful tools to progress in the analysis, design, and implementation of any particular and location dependent PDC unit including DNI variability, efficient power blocks, and TES performance.

However, certain precautions must be taken into account when analyzing the expectations of theoretical and/or simulated results and the comparison with experimental values: (a) the high thermal efficiencies (30–35%) commonly cited in the literature must be properly qualified for operation under actual conditions at a specific location; (b) it is obvious that the physical size of the receivers limits the thermal mass of any TES advantage and that its full time-dependent evolution is usually not considered; (c) closed power block cycles are inherently irreversible, with both pressure and temperature drops, and the most promising working fluids require special care in terms of safety risks; meanwhile, energy convertion units based on semiconductor materials are affected by the non-uniformity of the solar radiation which often are not fully taken into consideration; (d) it is not possible to create hybrid combinations that couple different and intermittent sources without significant exergy losses (not considered in some works) and receiver materials are greatly affected by long-term degradation. In particular, the latter greatly affect the LCoE and LCA, two key factors in the ultimate techno-economic viability of any PDC system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.G.-F. and A.C.-H.; Supervision, A.M., M.J.S., and J.M.M.R.; Funding acquisition, A.C.-H., A.M., and J.M.M.R.; Visualization, M.J.S., J.G.-F., A.M., and R.P.M.C.; Writing—original draft preparation, A.C.-H., M.J.S., A.M., and J.G.-F.; Writing—review and editing, J.G.-A., R.P.M.C., S.A., J.A.M.-H., and D.P.-G. All Authors equally contributed in the methodology, formal analysis, writing—the review and editing to provide the final version. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by: University of Salamanca and Junta de Castilla y León (“Next Generation EU” within “Programa Investigo, Plan de Recuperación, Transformación y Resiliencia”); the Energy for Future Postdoctoral Fellowship Program 2024-2025 MSCA Cofund and European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program (Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 101034297); the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (PID2023-147201OB-I00 project); and Junta de Castilla y León (Grant SA071G24).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

| Nomenclature | |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| CHP | Combined Heat and Power |

| CSP | Concentrated Solar Power |

| CSR | circumsolar ratio |

| CTS | Central Tower System |

| CST | Concentrated Solar Thermal |

| DNI | Direct Normal Irradiance |

| DSDC | Discretized solar dish collector |

| HTF | Heat Transfer Fluid |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| LCoE | Levelized Cost of Electricity |

| MCRT | Monte-Carlo Ray Tracer |

| MGT | Micro-Gas Turbine |

| MOOP | Multi-Objective Optimization Problem |

| ORC | Organic Rankine Cycle |

| PF | Pareto Front |

| PCM | Phase-Change Materials |

| PDC | Parabolic Dish Collector |

| STCPCR | Solar Thermochemical Coupling Phase Change Reactor |

| TCES | Thermo-Chemical Energy Storage |

| THEK | thermo-helio-electricity-kW |

| TES | Thermal Energy Storage |

| TRL | Technology Readiness Level |

| Symbols | |

| Dd | PDC Aperture diameter |

| fd | Focal length |

| Ib | Photon intensity |

| Greek symbols | |

| Collector rim angle | |

| Radiant flux | |

| Optical error (slope, align, track, etc.) | |

References

- Woerlen, I. Ericsson Solar Engine. 2023. Available online: http://hotairengines.org/solar-engine/ericsson-1868/study (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Coventry, J.; Andraka, C. Dish systems for CSP. Sol. Energy 2017, 152, 140–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilliestam, J.; Labordena, M.; Patt, A.; Pfenninger, S. Empirically observed learning rates for concentrating solar power and their responses to regime change. Nat. Energy 2017, 2, 17094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilliestam, J.; Ollier, L.; Labordena, M.; Pfenninger, S.; Thonig, R. The near- to mid-term outlook for concentrating solar power: Mostly cloudy, chance of sun. Energy Sources Part B Econ. Plan. Policy 2021, 16, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Sanders, S.R.; Dubey, S.; Choo, F.H.; Duan, F. Stirling cycle engines for recovering low and moderate temperature heat: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 62, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez, A.Z.; Soliman, A.; El-Metwally, K.A.; Ismail, I.M. Design analysis factors and specifications of solar dish technologies for different systems and applications. Renew. Sust. Energy Rev. 2017, 67, 1019–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayed, M.E.; Zhao, J.; Elsheikh, A.H.; Li, W.; Sadek, S.; Aboelmaaref, M.M. A comprehensive review on Dish/Stirling concentrated solar power systems: Design, optical and geometrical analyses, thermal performance assessment, and applications. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 283, 124664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.Z.; Shaikh, P.H.; Zhang, S.; Lashari, A.A.; Leghari, Z.H.; Baloch, M.H.; Memon, Z.A.; Caiming, C. A review on design parameters and specifications of parabolic solar dish Stirling systems and their applications. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 4128–4154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]