1. Introduction

Transmitting electricity via high-voltage power lines is one of the best and cheapest methods globally. Like in any engineering process, however, it has characteristics that have evolved over decades with a view to stabilizing network operation in energy systems. Power lines are the key parts of electric networks, particularly arterial lines, which are designed over considerable distances to work as part of high-voltage systems.

Our research interests cover transients in high-voltage power lines, in particular, their mathematical modelling. Their key parameters need to be addressed in order to correctly represent such processes in high-voltage lines. Given the substantial lengths of such lines, comparable to those of electromagnetic waves, clear wave processes are present in these lines. Another important characteristic of these systems is the presence of shield wires, whose interactions with live wires, particularly in emergency states like a lightning strike, must be taken into account.

Lightning strikes are among the most difficult in the theory of modelling energy systems. The need to address wave processes across a line, which requires combining field and circuit approaches, is one of the reasons. Another is the numerical realisation of a model, which consists of solving a mixed problem, which means calculating boundary and initial conditions.

To correctly represent these processes, the application of circuit-based approaches, i.e., representing lines with equivalent electric circuits, will not produce correct results, since the physical meaning of the model is lost. It is obvious that wave processes in long power lines need to be treated as distributed-parameter systems. A mathematical line model must then be based on field approaches and the fundamental laws of applied physics.

A number of approaches to mathematical modelling are available in the scientific literature, but two are crucial: the classic approach, based on the law of energy conservation, and the variation approach, relying on energy laws and allowing for a generalised description of complex physical systems and the generation of their state equations using Maupertuis’s principle of least action.

Despite substantial progress in modelling transient processes in long power lines, the question of their adequate representation in the conditions of lightning strikes remains open. The existing approaches implemented for universal software packages usually rely on some simplified assumptions concerning the line structure and fail to provide for an unambiguous determination of boundary conditions for partial differential equations. This is, in particular, true of lines containing two lightning protection wires, where electromagnetic interactions considerably complicate overvoltage dynamics across the line. In the circumstances, the application of the modified Hamilton–Ostrogradsky principle simplifies the formulation of the line state equation, starting only with energetic approaches.

The scientific literature offers multiple publications devoted to the modelling of transients across long lines struck by lightning. We shall focus on those closest to our subject matter.

Similar subject matter is addressed in [

1,

2,

3], whose authors analyse transients triggered by lightning strikes in power supply lines. Special attention is paid there to surges induced by the electric pulses associated with lightning, modelled as a distributed source of voltage, and to wave phenomena caused by electromagnetic pulses described by means of the Maxwell equations. A pulse is simulated using a model of a lightning strike current. Numerical simulations use Matlab/Simulink and Scilab environments.

Due to electromagnetic interactions between transmission line elements, a lightning strike in a shield wire affects current and voltage waveforms across live wires as well as other magnetically coupled line elements. It is, therefore, reasonable to analyse the nature and effects of this coupling in detail. Refs. [

4,

5,

6] deal with electromagnetic effects of pulses generated by lightning strikes and of the magnetic coupling between circuits. Ref. [

4] points out that the impact of an electromagnetic pulse triggered by lightning is normally ignored in the analysis of electric network failures, and only current flows across networks are addressed.

Ref. [

7] analyses the impact of lightning strikes on power lines and presents some methods for their protection. The operation of a 200 km-long 275 kV power supply line connected to a power substation with a 1000 MW rated power is simulated in the MATLAB/Simulink environment. A 30 kA lightning strike causes momentary overvoltages reaching 2.4 MV, causing an emergency stop of the line. Based on the results, some methods of protection against lightning overvoltages are suggested.

Ref. [

8] examines the effect of negative and positive polarity lightning currents on nonlinear surge arresters. A dynamic, frequency-dependent model of surge arresters proposed by an IEEE working group is employed. The oscillograms of real lightning currents are recorded, and their impact is analysed on surge arresters’ parameters. Contrary to standard approximations, the method addresses the real characteristics of lightning current waveforms.

The impact of a lightning strike on a hybrid overhead high-voltage line is studied in [

9]. In this case, the effect of a lightning strike on a 400 kV power line is simulated in the EMTP-ATP programming environment. The effectiveness of surge arresters in overhead lines is tested. A maximum of 2.6 MV is found in the absence of arresters, whereas a maximum overvoltage of ca. 730 kV is reached once the surge arresters are in place.

A comparative study of 220 kV line models exactly at the moment of a lightning strike, simulated using EMTP/ATP software, is undertaken in [

10]. The lightning strike is simulated across a live wire and the line’s lightning shield wire. Overvoltages of 50 kA and 100 kA caused by lightning strikes are simulated.

Ref. [

11] examines the effect of a lightning strike on a long 132 kV power line. ECSP electric circuit modelling software is used to analyse the line’s behaviour when there is a 100 kA lightning strike. All the elements of the electric network section studied are presented as an equivalent circuit in the mathematical model developed.

Ref. [

12] is dedicated to modelling a lightning strike against a 400 kV power line. The model is developed in an EMTP software package. A distributed-parameter line including two shield wires is taken into consideration. A method is suggested for selecting an optimum power line model for lightning overvoltage analysis.

Ref. [

13] examines overvoltages caused by lightning in multiple power lines, in particular, those including shield wires and nonlinear loads. Three line variants are modelled: shield wires; lightning shield wires but with surge arresting; and those including shield wires. The modelling is executed in the SPICE environment. Some simulations are undertaken to assess the effect of shield wire screening and analyse the effect of surge arresters. The results are compared to those available in the literature.

Ref. [

14] studies the impact of a direct lightning strike on a 24 kV distribution line and assesses the effectiveness of protection measures, including surge arresters and lightning shield wires. The electric network fragment in question is simulated in an EMTP/ATP programming complex. A mathematical analysis of electromagnetic wave reflection is carried out here as well.

Ref. [

15] analyses the effectiveness of storm protection in mixed 110 kV power lines that combine overhead and wire elements. The paper focuses on overvoltages across the main wire insulation and outside armature, since some cases of damage to external wire armature exactly at the moment of lightning strikes have been described in practice. Three programming complexes are applied, in particular, the insulation is modelled in EMTP, ATP, and MATLAB. An electromagnetic model of the earthing system is generated, while some additional electric potential modelling is executed in MATLAB.

Ref. [

16] simulates and analyses processes across a power supply line exactly at the moment of a lightning strike and their effects on power distribution lines where overvoltages occur. An approach to computing surges is suggested and tested by modelling. Remote lightning strikes against a line are modelled, too, generating a wave of overvoltages across the line’s live wires. The modelling is executed in the NETOMAC programming complex, which is specialised in the modelling of transients across electric networks.

Ref. [

17] develops some methods of dynamic modelling of lightning strikes across power lines. To this end, an algorithm is generated that gradually shifts the point of lightning strikes along a line and models a variety of scenarios. MATLAB and ATP interfaces are applied to the modelling.

The potential for improving lightning protection of power lines in mountain areas based on the optimum locations of linear surge arresters and shield wires is presented in [

18]. To this end, a transmission line including a double 400 kV circuit with various locations of lightning shields and surge arresters is executed in EMTP-RV software.

Ref. [

19] examines the impact of an indirect lightning strike against 66 kV power lines. Situations are highlighted where lightning strikes against adjacent 150 kV or 500 kV high-voltage lines, inducing an overvoltage across 66 kV lines, which may damage insulation. An electro-geometric model in the TAS programming environment is tested for a variety of current values.

Ref. [

20] studies lightning strikes in combined 20 kV transmission lines, concentrating on how pulse voltage varies depending on the strike location and line configuration. The analysis is carried out for strikes using lightning current peak values of 20 kA and 50 kA. Computer simulations are executed in ATP-EMTP software.

Our team has already developed a series of mathematical models of electric power, electric and mechanical, electromagnetic, and other systems based on energy approaches and using a modified Hamilton–Ostrogradsky variation principle [

21,

22,

23]. An application of this principle to transient modelling across a three-phase long transmission line, including two shield wires exactly at the moment of a lightning strike, is presented here. It should also be noted that the paper will proceed to discuss the traditional three-phase line with two shield wires, which will be analysed as a five-wire line.

In ref. [

24], numerical solutions to the NLS equation are obtained using the B-spline Galerkin method. Time discretization and the B-spline basis function for space discretization are obtained using the Crank–Nicolson scheme. The obtained equations were verified in numerical experiments. The linear stability of the method was investigated using the Von Neumann method.

Ref. [

25] presents a numerical analysis of the one-dimensional Burgers’ equation using a method based on the collocation of cubic B-splines over finite elements. The proposed method was tested using three experiments. Integrating the Burgers’ equation in terms of time and space makes it possible to obtain a system of differential equations that is stable.

Both the accuracy and complexity are still examined for the methods of mathematical modelling of processes taking place in power lines affected by lightning strikes. Ref. [

26] analyses a variety of modelling approaches and their impact on simulations in the ATPDraw environment. The models applied there are adopted for the analysis of transient states across distribution lines, and attention is drawn to the use of the models for the purpose of simulating transmission lines of different designs. Interestingly, the level of a model’s detail does not necessarily translate into any significant differences in simulation results. Mathematical models are also universally employed to analyse short-circuiting and develop the methods of their detection, which has already been studied in [

26,

27].

The simulation of transients triggered by lightning strikes against distribution line elements is an important and complex field of research that is extensively discussed in the literature. Ref. [

28] analyses wave phenomena across long distributed-parameter power lines, considering transient states associated with line turn-on. The numerical method of interpolation and spline functions serves to solve equations describing the system. Another approach is suggested in [

29], which searches for solutions to long line differential equations with the method of basis functions combined with the finite difference method in the time domain. Distributed-parameter systems are analysed in [

30,

31], too, where the Laplace transforms are employed in the domains of both time and frequency. Those results help to develop models that better represent losses across wires and improve the accuracy and flexibility of simulations, as well as some models allowing for the application of line ends of any complex impedance without the necessity of redesigning the line itself.

This review of the state of the art suggests there is no single approach to the modelling of overhead power lines when considering lightning protection, especially with regard to research into transient electromagnetic processes exactly at the moment of lightning strikes. Existing models differ significantly in their levels of detail, assumptions, and mathematical approaches. Some use concentrated-parameter models or simplified line topologies treated as single circuits. Such models fail to accurately represent wave processes or asymmetrical states. EMTP, ATP, and MATLAB/Simulink software packages are the most common modelling tools, but they suffer from a range of limitations, in particular, insufficient clarity of disclosing numerical resolution algorithms for process realisation and the application of simplified methods like that of travelling waves. This software, since it is universal, may not address all forces other than those of potential and kinetic nature, as named in Max Planck’s terminology, and thus is not always fit for analysing processes across electric power lines, especially including lightning protection wires. Research along these lines is, therefore, important.

It is, therefore, the aim of this paper to apply a modified Hamilton–Ostrogradsky principle to the mathematical modelling of transients across a five-wire distributed-parameter power supply line exactly at the moment of a lightning strike against its lightning protection wire.

2. The Differential Equations of a Five-Wire Long Power Line

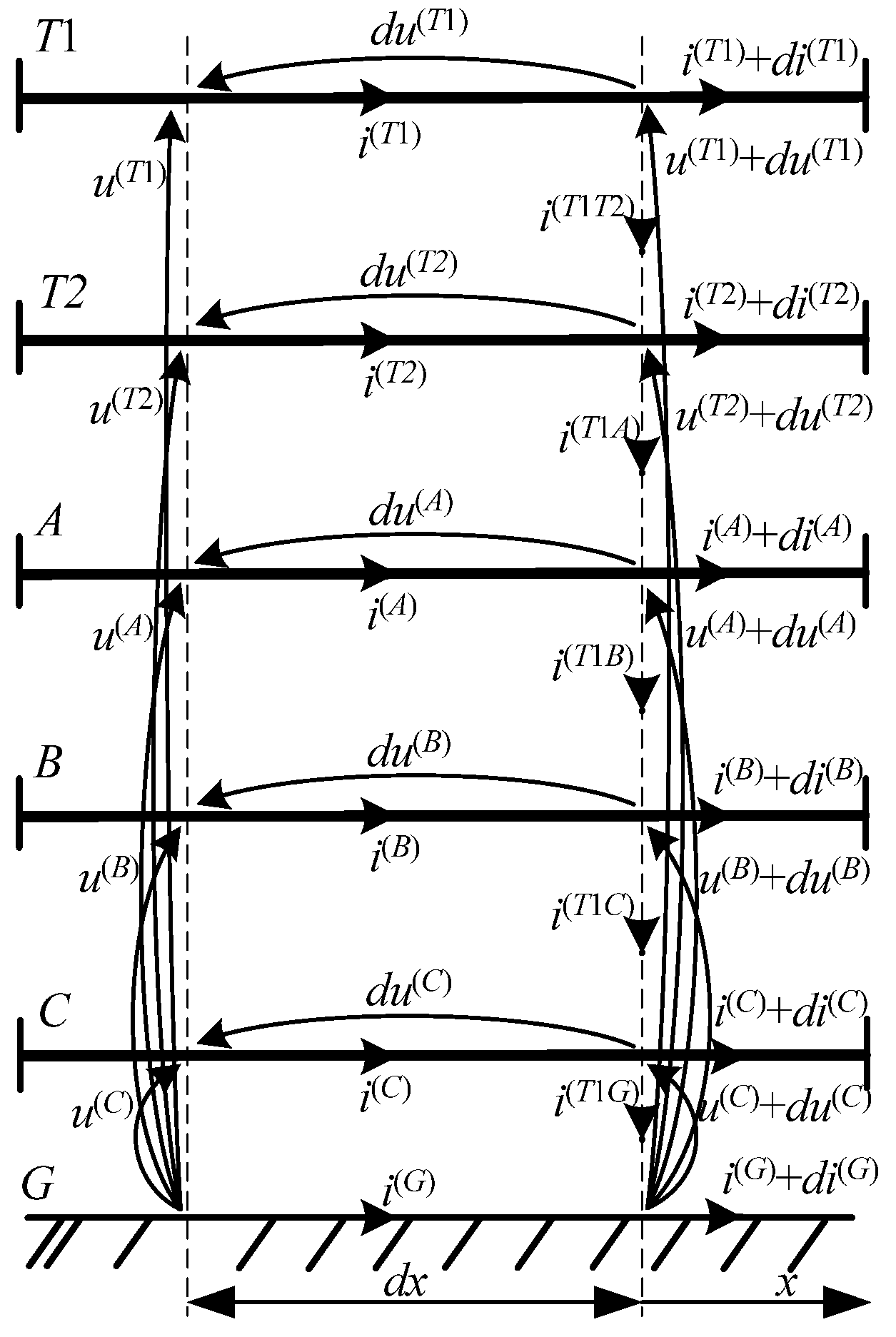

Figure 1 shows a five-wire system representing a long power line including lightning shield wires; shield wires

T1,

T2, and live wires

A,

B,

C are designated. Separated live wires are presented as single wires of appropriate equivalent radii.

The following is the action functional for the distributed-parameter system in question [

21]:

where

S—action functional according to Hamilton–Ostrogradsky,

L*—extended Lagrange function,

Ll—the linear density of the modified Lagrange function, and

I—energy functional.

The extended functionality of the action functional according to Hamilton–Ostrogradsky for the system will be as follows [

21]:

where

—kinetic coenergy,

P*—potential energy,

Φ*—energy dissipation, and

D*—the energy of external nonpotential forces, with the index

l corresponding to the linear densities of energies.

To develop a mathematical model of the line, the functional variation (1) needs to be calculated and compared to zero. The Euler–Poisson equation results that can be interpreted as the mathematical model of a given distributed-parameter object are as follows:

The stationary connection equation as per Kirchhoff’s first law for a long line’s elementary section with the length of

and the shield wire

T1, where

(see

Figure 1), is as follows:

where

x—the coordinate travelling along the power line;

—elementary line unit;

—the leakage current element across

T1 with the length of

; and

—leakage current elements between shield wires

T1 and

T2, phases

A,

B,

C, and the earthing

G.

Equations for the remaining power line wires can be formulated in a similar manner.

Considering all the line’s phase and shield wires, (4) is confirmed as subject to the condition

, and the following results:

where

—the elements of the power line section load for

T1,

T2, and phase wires

A,

B, and

C (

).

Writing the expression for the line element loads in the instance of

T1 will produce the following:

where

—voltages between shield wires and between phase wires;

—linear capacitances between the phase wire and the shield wire and between the phase wires.

Considering (4)–(6), the following is written:

where

, (7)–(11) can be written as coordinates; since high-voltage power lines must be transposed, we assume

,

,

,

,

and the following results:

where

u(T1),

u(T2),

u(A),

u(B),

u(C)—the voltages of

T1,

T2 relative to ground and phase voltages

A,

B,

C;

CTT,

CTF,

CFF—capacitances between the lightning shield wires, between the shield and phase wires, and between the phase wires;

CTG,

CFG—capacitances between the shield wires and the earthing and between the phase wires and the earthing.

Relying on Kirchhoff’s second law, five circuit equations will be formulated for

(for

T1), see

Figure 1, and the following will result:

where

—voltages between the phase wires and the ground across the line section

;

—the linear resistances and inductances of the line’s shield and phase wires;

—linear mutual inductance between the appropriate line wires;

—line wires;

—linear earth resistance;

—current across the earth.

Dividing (14)–(18) by

and given

, equations in the coordinate format are produced, assuming

,

,

,

,

,

,

:

where

i(T1),

i(T2),

i(A),

i(B),

i(C)—the currents of

T1,

T2, and

A,

B, and

C;

r0T,

r0F,

rG—the linear resistances of

T1,

T2,

A,

B,

C and of the earth;

L0T,

L0F—the linear inductances of

T1,

T2,

A,

B, and

C;

MTT,

MTF,

MFF—mutual linear inductances: «shield wire-shield wire», «shield wire-phase wire», and «phase wire-phase wire».

The following are (12) and (19) in the matrix-vector format:

where

—the column vector of line wire loads;

—the column vector of line currents;

—the column vector of voltages between the line wires and the earth; and

—line parameter matrices.

Using the equations for kinetic and potential energies across a long line and the linear density functions of the internal and external electric energy dissipation, the linear density elements of the non-conservative Lagrange function [

21] are produced:

where

—the linear density of the internal electromagnetic energy dissipation;

—the linear density of the external electromagnetic energy dissipation;

,

—wire and interwire linear electrical conductivities of the line, respectively (

). Electric energy is only transmitted via the electromagnetic field (Poynting vector), whereas line wires merely indicate the direction of the field’s action. This explains the minus sign in the first expressions of (23) and [

21].

The following is written based on the first expression in (20):

Note that the matrix C is analytically reversed with the additional aid of the symbolic calculation package Maple 2023.2.1, which produces an accurate analytical form of matrix C−1.

Thus, by detailing the variation in internal energy functional

I, comparing it to zero, and considering the linear density elements of the Lagrange function (21)–(23), the following five-wire interpretation of the long distribution line is produced:

Similar mathematical operations can obviously be executed for the function of wire load Q or current i across the line. Experience suggests that analysing transient line processes using voltages (u) is reasonable.

The conductance

g matrix has the same topological structure as the capacitance

C matrix [

21], since mutual conductances between wires are defined by the same configuration of electric connections as the corresponding mutual capacitances, and hence, we have the following:

where

gTT,

gTF,

gFF—electrical conductivities between shield wires, between lightning protection and phase wires, as well as between phase wires;

gTG,

gFG—electrical conductivities between shield wires and the earth and between phase wires and the earth.

3. A Mathematical Model of the Electric Network

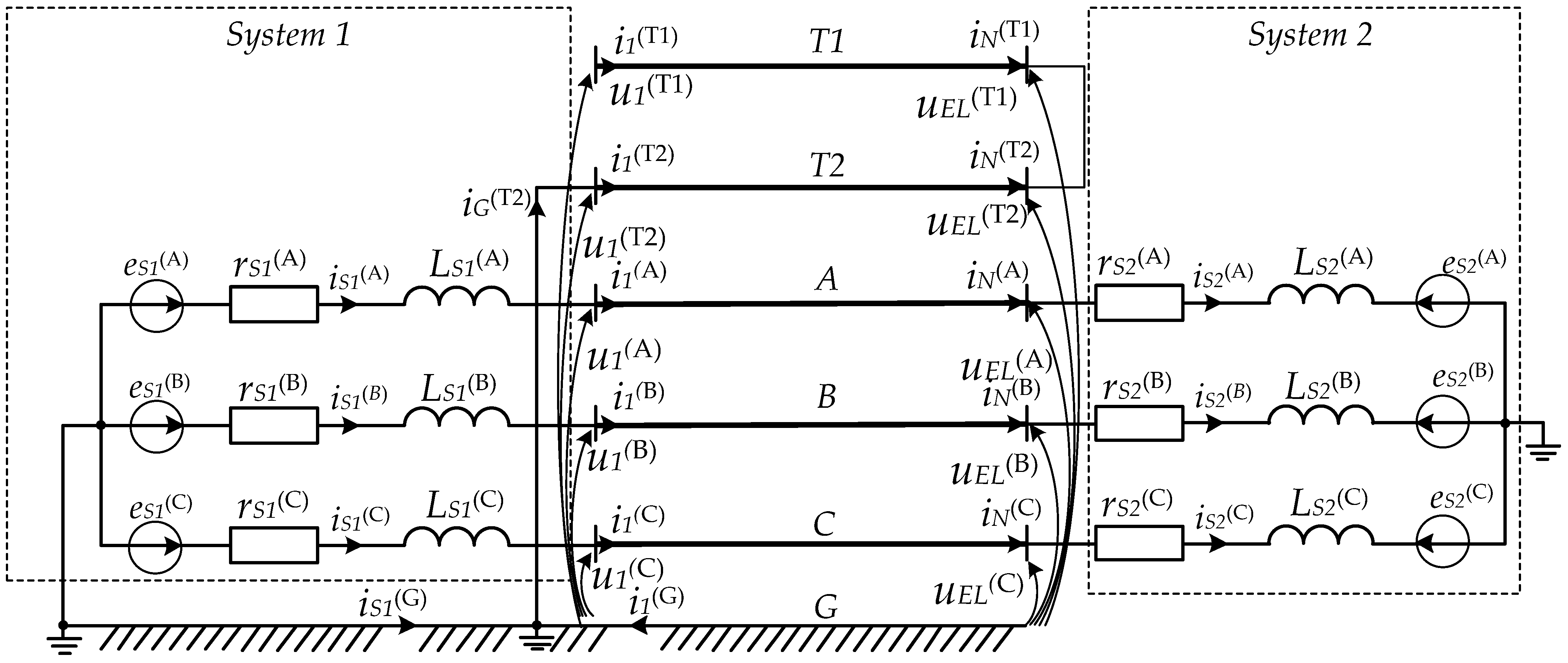

Figure 2 contains a calculation scheme of the power line section studied, which consists of a power supply line connecting two equivalent electric power systems 1 and 2. The line is presented as a distributed-parameter system including two lightning shield wires. According to the long line Equation (25) and

Figure 1, the line is seen as including five conductors, shield wires

T1 and

T2, and phase wires

A,

B, and

C. Equivalent electric power systems are presented with phase electromotive forces

eS1,

eS2, their corresponding modules and arguments of phase shift angles, internal active resistances

rS1,

rS2, and inductances

LS1,

LS2.

T1 and

T2 are connected at the line’s end and open at its start, thus forming an open circuit, and

T2 is earthed at the line’s start. This particular scheme is selected for the purposes of research as it reflects the design of an actual ultra-high-voltage 750 kV power transmission line from the West Ukrainian substation to Vinnytsia (Ukraine), which helps bring the results of modelling as close to actual operating conditions as possible.

The electromagnetic state equation of the equivalent electric power system (

Figure 2) based on Kirchhoff’s second law is produced:

Equation (28) contains the following matrices and column vectors:

where

eS1(A),

eS1(B),

eS1(C),

eS2(A),

eS2(B),

eS2(C)—the phase electromotive forces EMFs of equivalent electric power systems 1 and 2;

iS1(A),

iS1(B),

iS1(C),

iS2(A),

iS2(B),

iS2(C)—phase currents across the branches of equivalent electric power systems 1 and 2;

rS1,

rS2,

Ls1,

Ls2—the internal resistances and inductances of equivalent electric power system branches.

Equations (25) and (28) describe the electromagnetic condition of the system analysed. Solving (28) poses no difficulties with a range of available software, whereas (25) contains second-order partial derivatives, and appropriate boundary conditions must be set in order to solve it.

Since (25) is related to voltage functions, voltages at the line’s ends must be found to solve it; in other words, the boundary problem must be solved. In the general case, voltages at the line’s ends are not known, which leads to quite complicated approaches to determining the Neumann boundary conditions of the second type and the Poincare conditions of the third type. A concept for determining these boundary conditions will be introduced.

Considering the distributed parameters of the power line, r, L, C, and g, which are dependent on frequency, would greatly complicate the mathematical model. Addressing the impact of frequency is crucial to detailed research into very high frequency components or into the problems of precise insulation coordination. Therefore, no parameters dependent on frequency are considered to develop our mathematical model.

Discretising (20) and (25) with the method of lines [

21] produces the following:

where Δ

x—discretisation step, and

N—the number of discretisation nodes.

Equations (32) and (33) will be written for the first discrete node:

Equations (34) and (35) show the currently unknown u0 representing the so-called virtual voltages across a fictitious node. The following method will serve to find it.

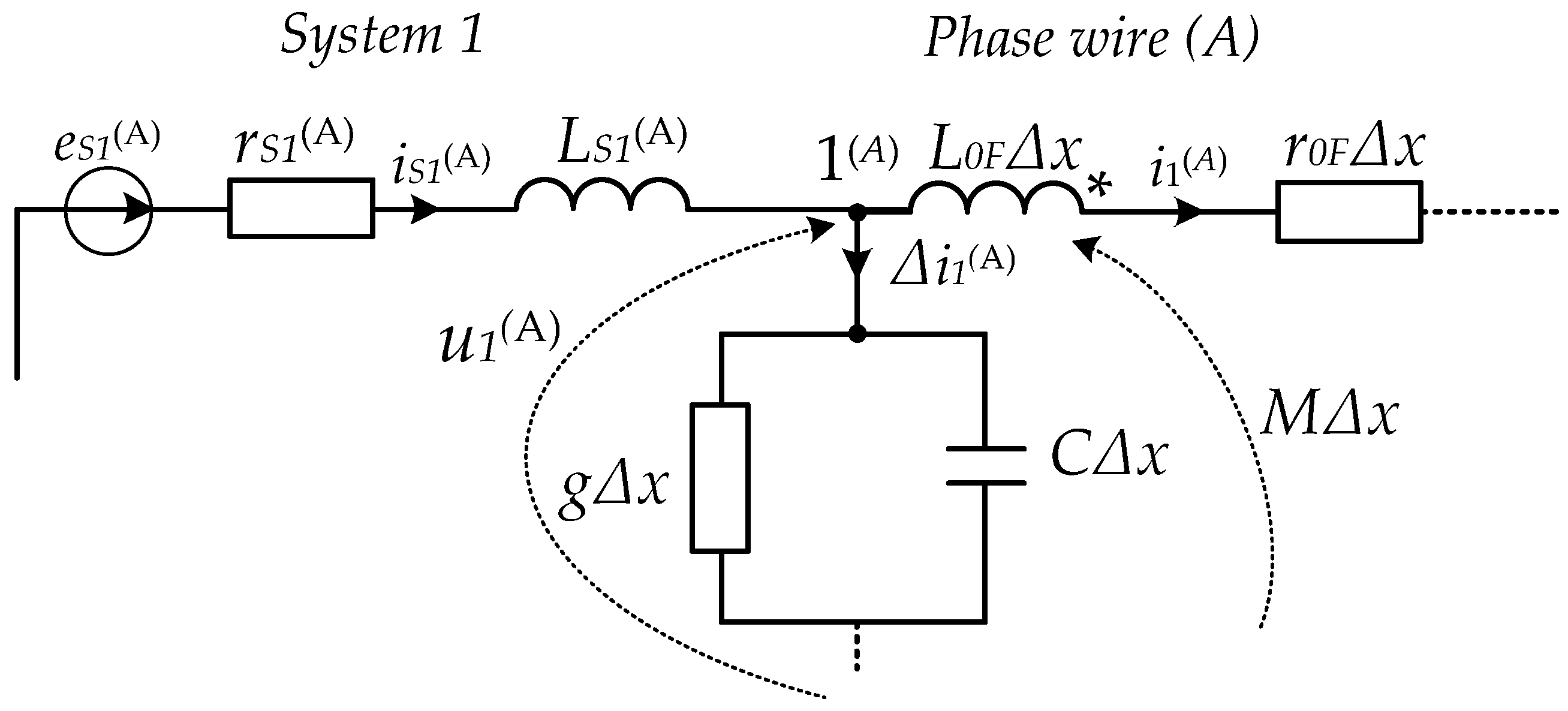

Figure 3 depicts a calculation scheme of the first discrete section of a power line for phase

A.

The following will be written for Kirchhoff’s first law:

where

is the summary leakage current into the earth.

is derived from the following:

Differentiating (36) and (37) against time while considering the boundary condition will produce the following [

21]:

Substituting the first expression in (28) to (38), (35), and (39) will result in the following:

Substituting (34) to (40), we arrive at the following:

Equation (42) helps to determine the virtual voltage of a fictitious node at the line’s start, .

Equations (32) and (33) will be formulated for the line’s end,

j = N:

An analysis of (43) and (44) shows that voltages across the fictitious nodes at the line’s end, uN+1, must be known in order to find voltages across the final discretisation nodes and currents across the final discrete branches of shield and phase wires of the long line.

Employing the boundary condition of the third type, the universal expression for finding u

N+1 of the fictitious nodes at the line’s end has already been found in [

22]. Since the method of finding the voltages remains unchanged in the presence of shield wires, we will not present the mathematical derivations or discuss the method, but will only introduce its final format to save space:

This expression serves to autonomously utilise the mathematical model of the power supply line for the purposes of modelling any configuration of network element connections to the main grid. This means the problem of finding voltages across a fictitious node is reduced to finding the voltages at the line’s end—the column vector elements (

= (

uEL(T1),

uEL(T2),

uEL(A),

uEL(B),

uEL(C)). As the shield and phase wires of the line have different connection configurations, the expressions for finding them will obviously be different. The method of finding the voltages

is described in [

23]. To avoid tautologies and excess mathematical formulas, only the final expressions for finding the vector elements will be presented.

The line’s end voltages for the lightning shield wires will be the same, since they are connected at the line’s end:

where

m =

T2,

A,

B,

C; and

n =

T1,

A,

B,

C.Voltages at the line’s end will be of the same type for the phase wires, too. For phase A wire, the voltage at the line’s end is as follows:

4. Lightning Strike Modelling

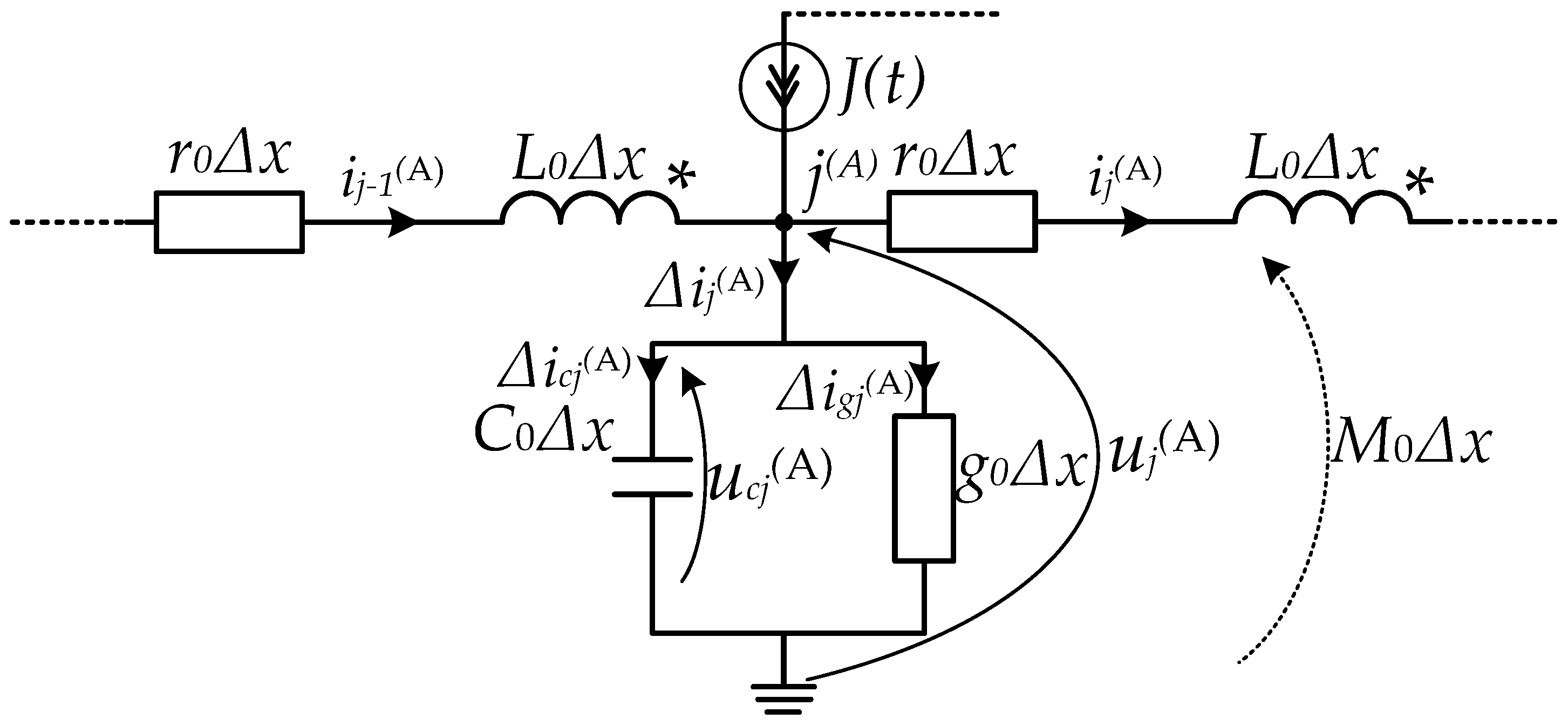

A similar approach is suggested for simulating a lightning strike as the one used to set the boundary conditions for the power line equation. In particular, we suggest considering a lightning strike against the

jth discretisation node in

Figure 4. For the sake of simplicity, we present a diagram for the line’s phase

A.

It is easy to note in the equivalent diagram that the voltage of the

jth discretisation node

uj is equal to the voltage across the capacitance C

0Δx of the same node

ucj,

uj =

ucj. Since the same will apply to all the line wires, the successive equations will already be written in their matrix-vector format:

where

j—discretisation node number; and

—the vector of leakage currents into the earth.

The following will be written then, cf. [

32]:

where

—the column vectors of currents across the

j − 1th discrete line branch, lightning current, the currents of the

jth discrete line branch, and leakage currents across the line conductance into the earth at the

jth discretisation node.

Equation (48) considering (49) will be written as follows:

where

A typical current pulse of the amplitude 66 kA with the time characteristic 3.7/13 µs and total pulse duration 80 µs is suggested for our purposes here [

33].

The lightning current has a physically complex form of a pulse function, which is to some extent similar to the Dirac function δ(t). Accordingly, the lightning current function JL(t) is approximated by means of a cubic interpolation of a section curve as eight splines.

This ensures the first and second derivatives are continuously interrupted, and signal modelling is highly accurate. The application of spline interpolation functions to modelling problems involving high-frequency signals is actively studied, as demonstrated by [

24], and confirms its applicability.

This approach helps to describe physical processes across the power line exactly at the moment of a lightning strike with a high degree of adequacy and without applying complex electrodynamics equations like the well-known Maxwell’s equations.

The approximation of the lightning current function is analytically formulated as a cubic spline interpolation function. As a result, the interpolation curve is smooth, or continuous, across the first and second derivatives and can be matched to data with greater accuracy than in simpler interpolation methods, e.g., linear:

where

t is the time expressed in microseconds.

By substituting JL(t) for the column vector JL, a lightning strike against any line wire or point can be simulated.

The following systems of equations are jointly integrated (28), (32)–(35), (43), (44), and (50), considering (29)–(31), (42), (45)–(47), and (52).

5. Computer Simulation Results

A programming code is created in Visual Fortran 2021.1.1 on the basis of the mathematical model. The programme allows for a computer simulation of transient electromagnetic processes across the electric network section, as shown in

Figure 2.

Transient electromagnetic processes across the power line are simulated at two stages: the line is switched to its normal operation first, and after it reaches its steady state, a lightning strike is simulated midline. The simulation is carried out since the moment t = 0 s and follows the sequence below.

At the first stage, the line is switched on as the momentary phase voltages are zero. This corresponds to the physical model of the line switch-on, which involves phase turn-ons as momentary voltages are zero. The switches are not directly modelled here, and the switching is realised as momentary state changes.

The following are the starting moments of phase turn-ons at the line’s start: tes1(A) = 0.0088 s, tes1(B) = 0.0054638 s, and tes1(C) = 0.0021333 s. The corresponding moments at the line’s end are tes2(A) = 0.0093194 s, tes2(B) = 0.0059833 s, and tes2(C) = 0.0026527 s. The indicated time instants correspond to the controlled switching moments of the phase circuit breakers.

At the instant t2 = 0.12 s, the introduction of a negative lightning pulse with the current amplitude 63 kA and time characteristic 3.7/13 µs (mid-line) to the shield wire T1 is simulated. Modelling the process of line turn-off with the protection apparatus is not analysed here.

A computer simulation is undertaken for a real overhead 750 kV power line between the West Ukrainian and Vinnitska (Ukraine) substations, whose total length is l = 360 km. These are the line’s detailed parameters for a unit of length:

r0F = 1.9·10−5 Ω/m, r0T = 4.28·10−4 Ω/m, rG = 5·10−5 Ω/m, L0F = 1.647·10−6 H/m, L0T = 2.4049·10−6 H/m, MFF = 7.41·10−7 H/m, MFT = 7.4·10−7 H/m, MTT = 7.05·10−7 H/m, gFG = 3.253·10−11 Sm/m, gFF = gFT = 3.253·10−13 Sm/m, gTG ≈ 0, gTT ≈ 0, CFG = 0.8647·10−11 F/m, CFF = 0.103·10−11 F/m, CFT = 0.0723·10−11 F/m, CTG = 0.3501·10−11 F/m, and CTT = 0.04162·10−11 F/m. The equivalent power systems at the line’s ends display the following parameters: rS1 = 2.03 Ω, LS1 = 0.16 H, rS2 = 2.4 Ω, and LS2 = 0.14 H for each phase.

The simulation is performed for the following EMFs: es1(A) = 612 sin(ωt + 21.7°) kV, es1(B) = 612 sin(ωt − 98.3°) kV, es1(C) = 612 sin(ωt + 141.7°) kV, es2(A) = 600 sin(ωt + 12.7°) kV, es2(B) = 600 sin(ωt − 107.3°) kV, and es2(C) = 600 sin(ωt + 132.7°) kV.

The spatial discretisation step of partial differential equations is Δx = l/20 = 18 km. The resulting ordinary differential equations are integrated using the implicit Euler method with a time step of Δt = 13 μs for general simulation, which is reduced to Δt = 1 μs during the lightning strike to accurately capture the high-speed transient lasting about 80 μs.

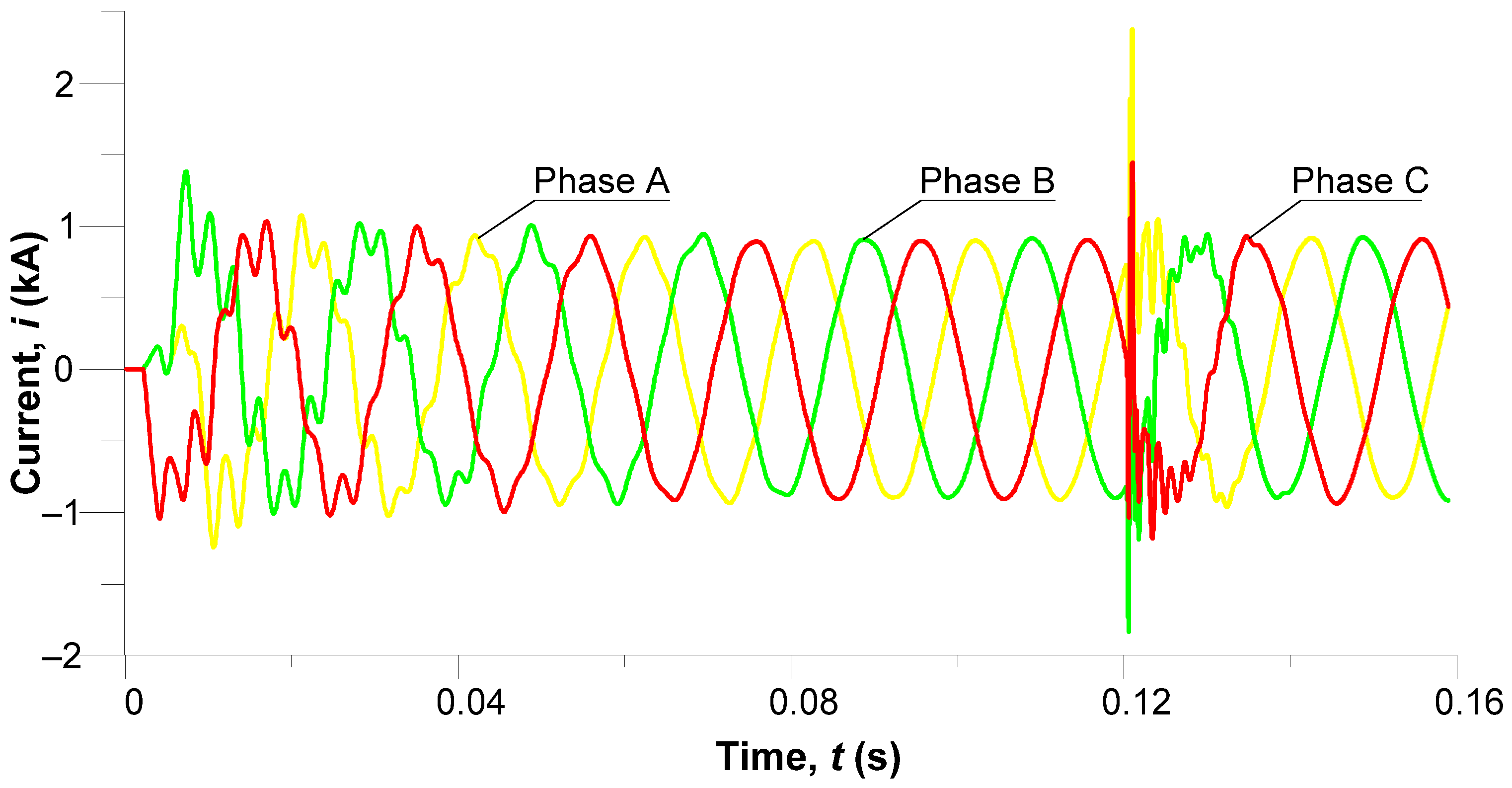

The computer simulation results are presented graphically. In these graphs, yellow lines stand for processes in phase A, green lines for processes in phase B, and red lines for processes in phase C. The black lines denote processes associated with the shield wires T1 and T2.

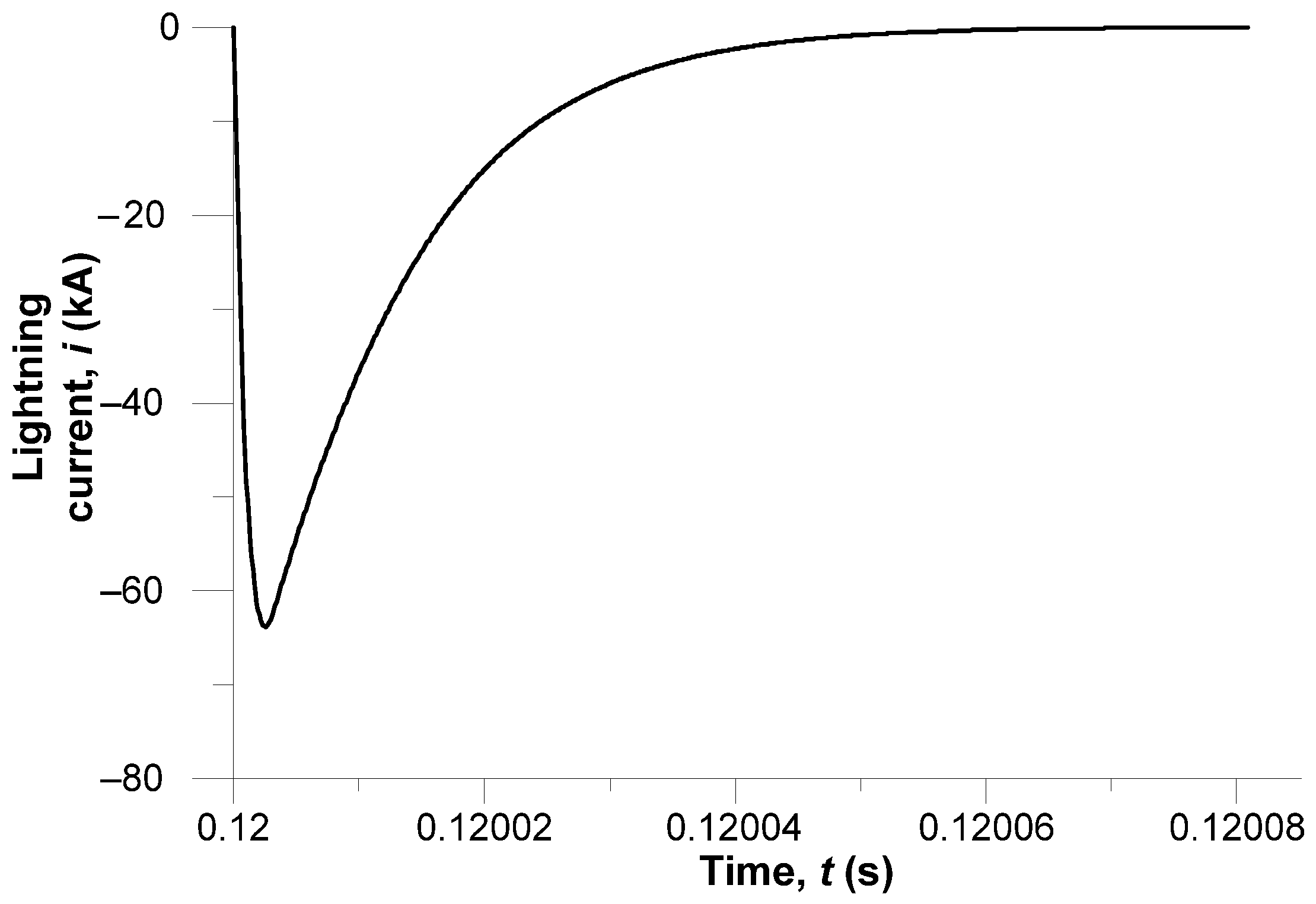

Figure 5 shows the time waveform of the computer-simulated lightning current.

Initially, the negative current grows extremely fast to reach an amplitude of above 66 kA at microsecond intervals. This curve shape is typical for negative lightning strike pulses. On reaching its peak value, the current vanishes relatively slowly for approximately 80 µs. This shape matches the realistic parameters of lightning currents in power lines and illustrates the short, but powerful, effect of a lightning pulse well. It may cause substantial overvoltages, electromagnetic disruptions, and resonant effects across the network.

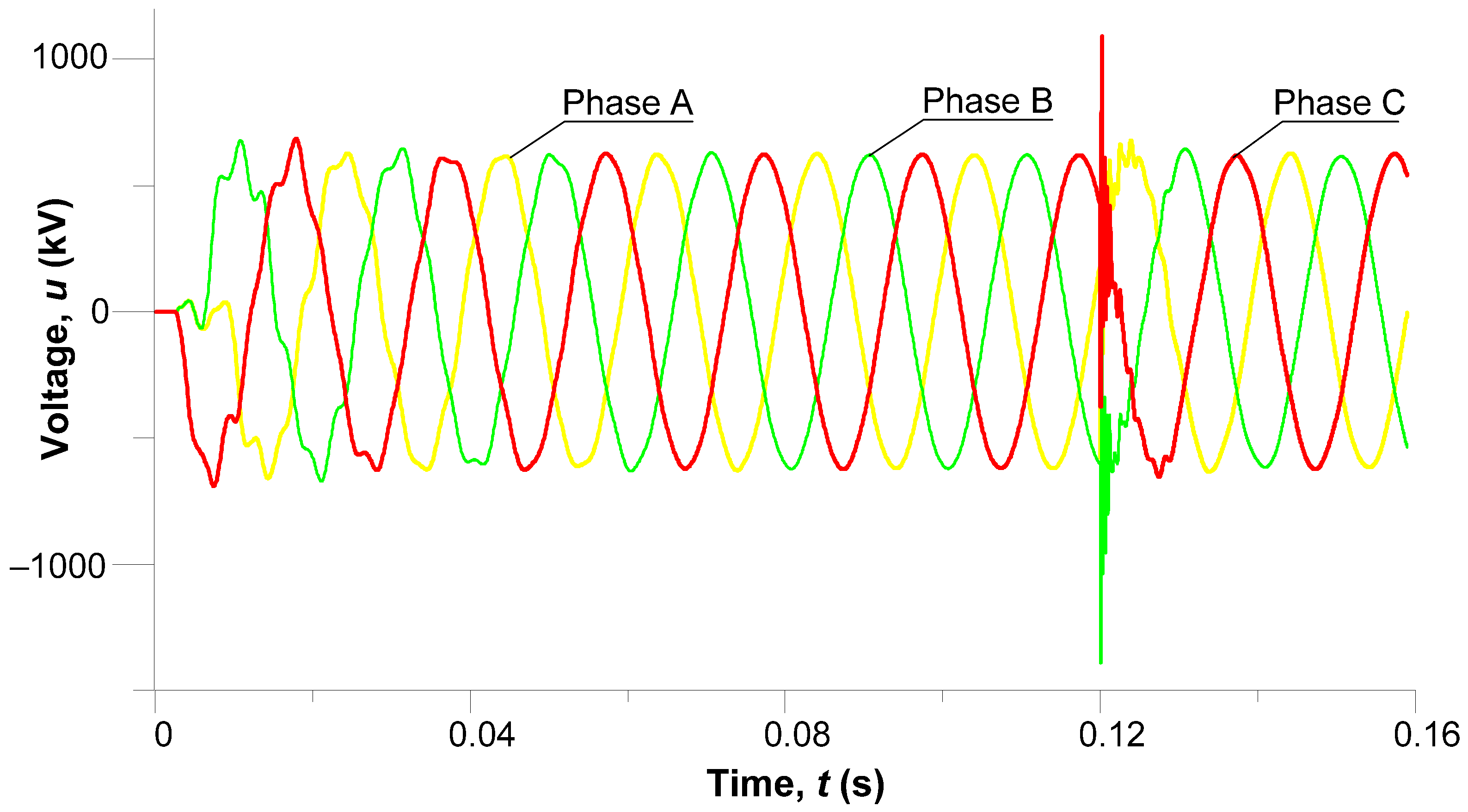

Figure 6 shows phase voltage transients in the middle section of a power line.

Promptly after voltage is applied, some short-lived oscillations can be observed that are caused by the line’s turn-on. They do not exhibit significant amplitudes and are typical, since controlled turn-on is applied, where the temporary phase voltage is zero. Starting with approximately t = 0.06 s, the steady state begins: all three phase voltages are sinusoidal, with an amplitude of circa 620 kV, and in the normal symmetrical three-phase state.

Once the lightning strikes against T1 (t = 0.12 s), high-frequency overvoltages take place in the system that cause electromagnetic interactions (Faraday’s law) with phase wires and induce EMFs across all three phases. This is best seen in phase B (the green curve), where a sharp voltage pulse is noted, followed by its overvoltage and vanishing. The phase symmetry is moving, and high-frequency oscillations appear, indicating electromagnetic effects in the system. The Figure illustrates the nature of a lightning strike, which does not cause a direct phase short-circuit but has a considerable impact on the electromagnetic condition of the entire line interphase space.

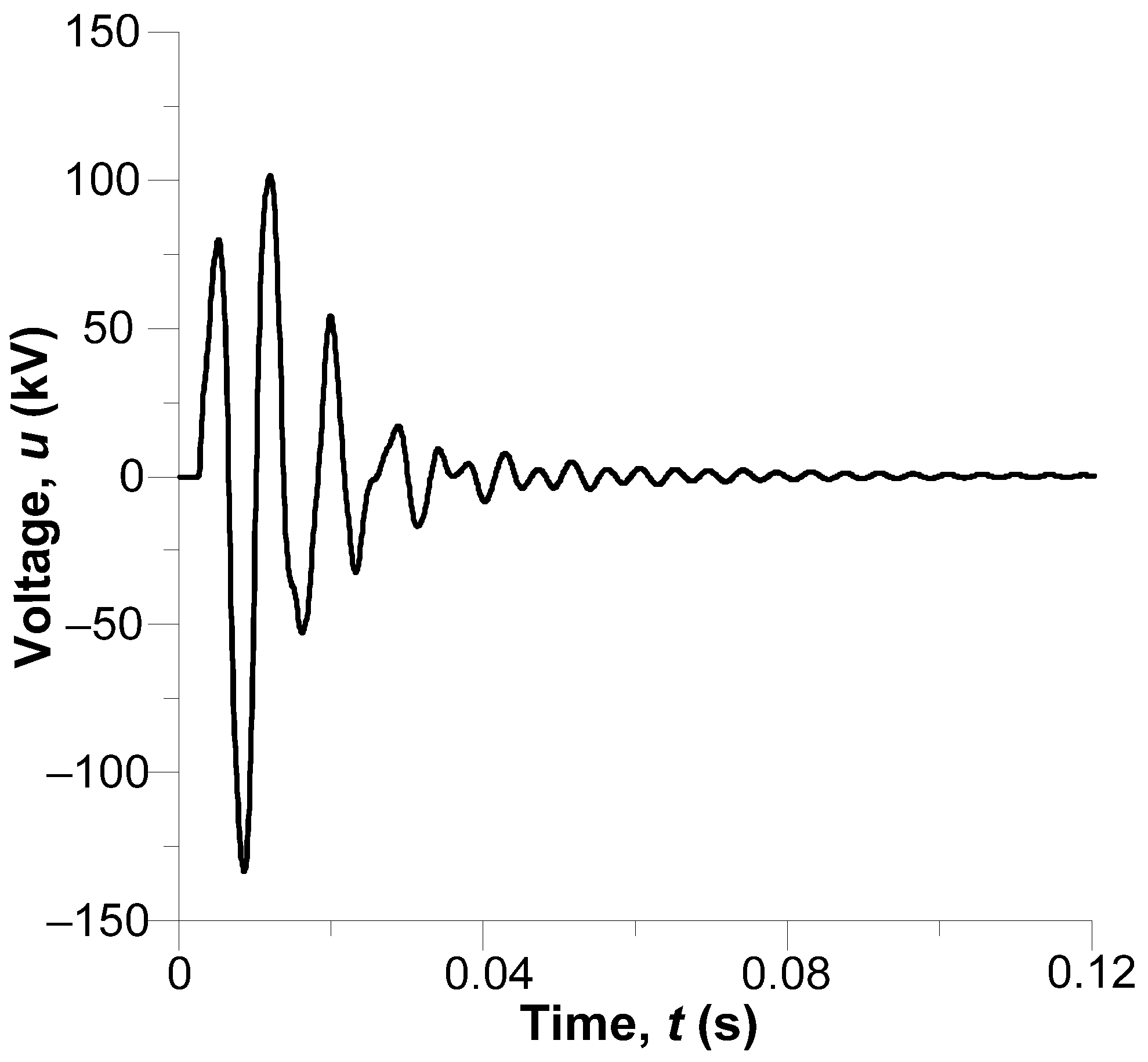

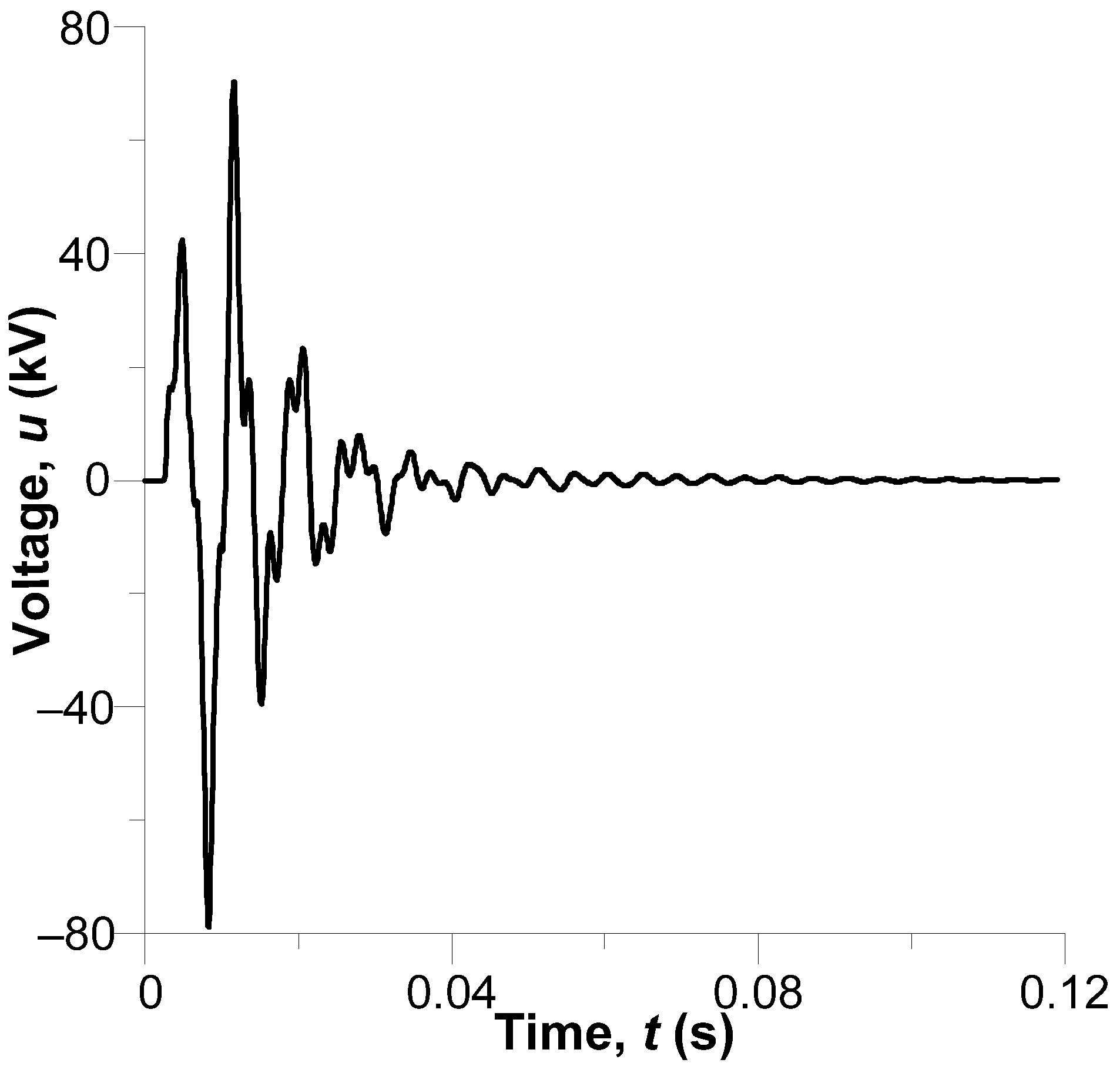

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 show temporary voltages across

T1 and

T2 in the middle line section within the interval from 0 to 120 ms, that is, before the lightning strike.

Following the line’s turn-on, wave overvoltages occur across the shield wires. The maximum voltage of T1, insulated at the line’s start, is approximately −140 kV, a result of an EMF induced by an electromagnetic coupling with phase wires. The transient process continues for up to 0.08 s, and then the voltage stabilises, approaching zero. Since T2 is earthed at the line’s start, the overvoltage across it is circa −80 kV, and its oscillations vanish more quickly. These results uphold the importance of an effective earthing of T2 to limit overvoltages at the time of transients across the line. In addition, the application of a controlled commutation helps to greatly reduce the amplitude of initial voltage waves and the likelihood of insulation breakdown.

Figure 9 presents transient current processes across phase wires in the middle line section.

At the time of a controlled line turn-on, when the temporary voltage is zero and short-lived, inrush currents show low amplitudes, and, in particular, the phase A current is 1.24 kA and in phase B, 1.38 kA, with inrush currents across phase C virtually non-existent, which corresponds to a normal transition to a steady operating state. Once the steady operation is maintained, the current amplitudes across phases are ca. 0.9 kA and are typically sinusoidal.

When lightning strikes against T1, additional transitional disruptions arise across phase wires. Due to the mutual effects of shield and phase wires, currents across the latter include short-lived, pulse surges, and drops. These peak currents reflect electromagnetic interactions between the shield and phase wires in the line. For the purposes of a continuing analysis of lightning strike impact, their characteristics will be discussed.

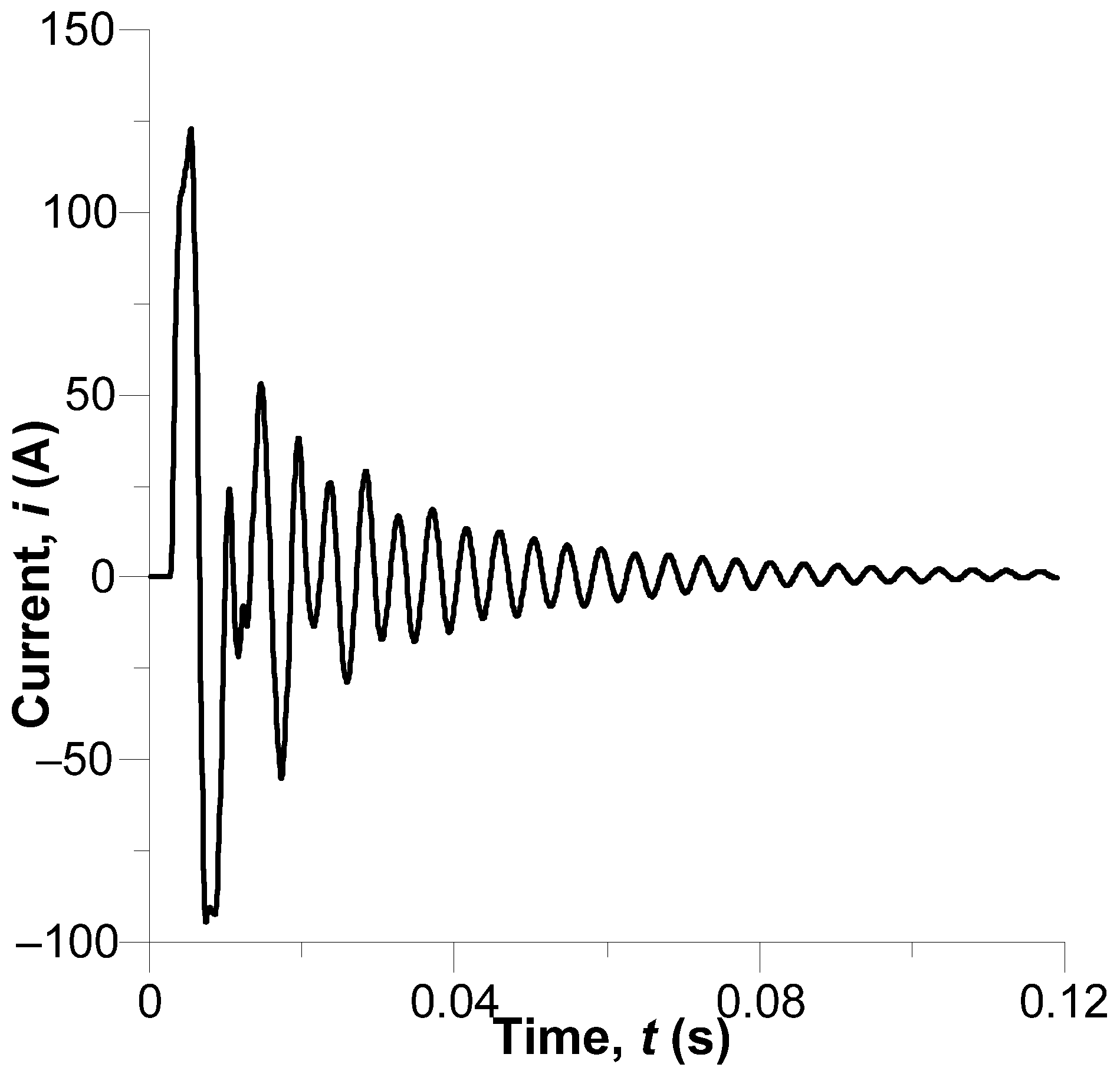

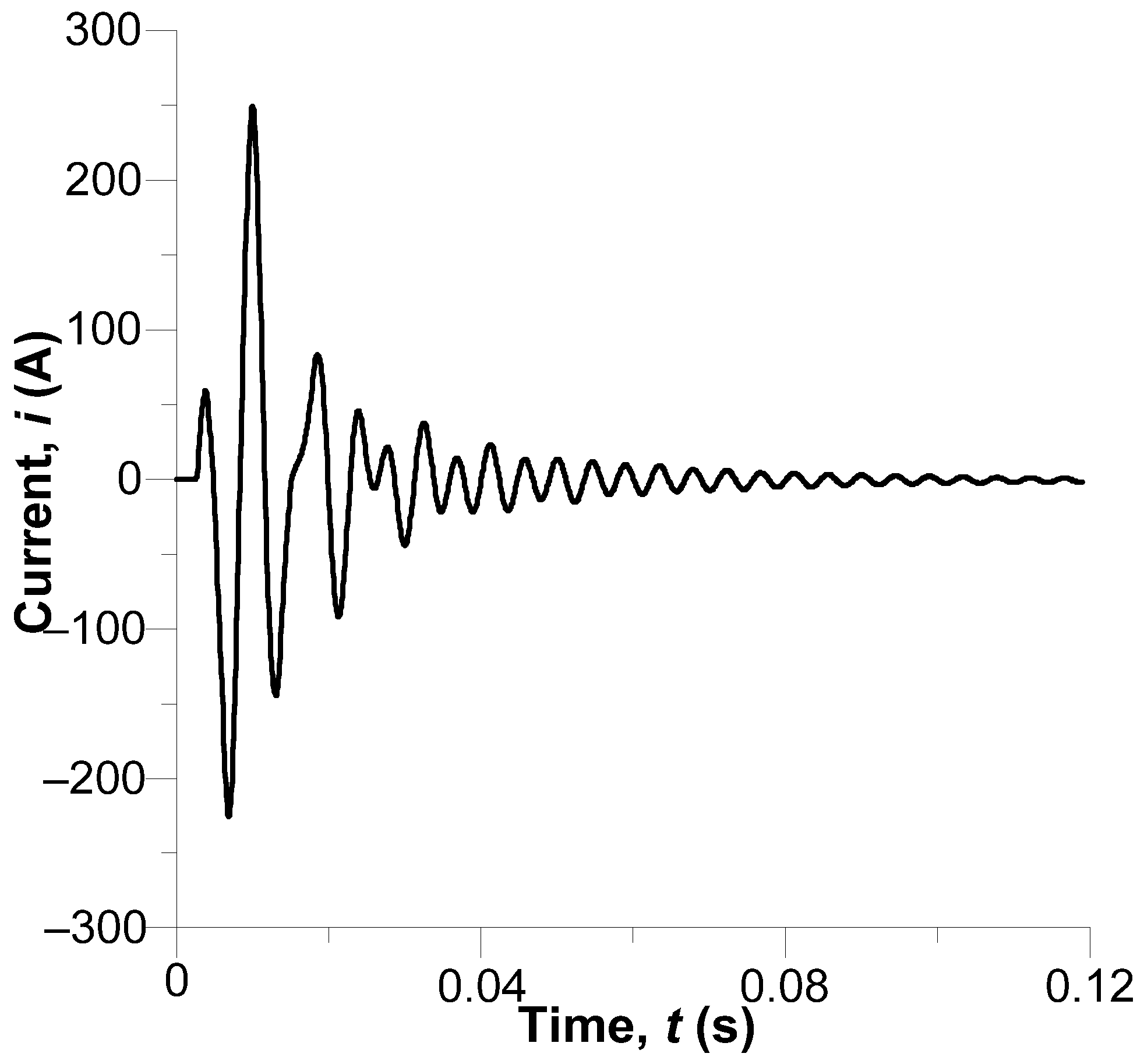

Transitional currents across

T1 and

T2 in the middle line section are depicted in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11.

Current is applied to T1: Following an initially quick rise, the current becomes oscillatory, and the amplitude visibly reduces. The maximum current is about 125 A. In T2, meanwhile, with one end earthed, the current’s amplitude is markedly greater and reaches 250 A. The difference relates to the different operating conditions of T1 and T2.

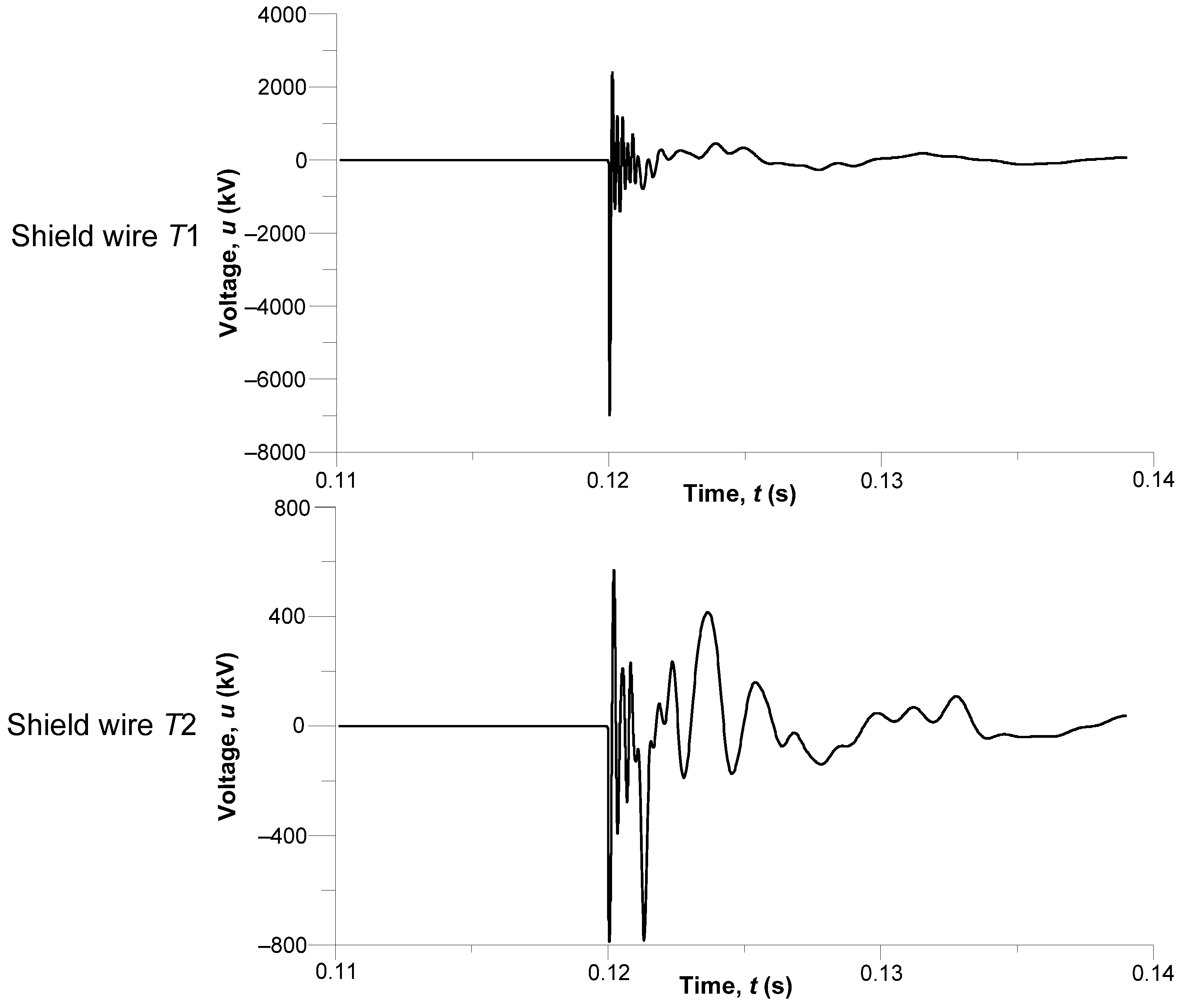

Let us now analyse the processes exactly at the moment of a direct lightning strike.

Figure 12 presents transient voltages across shield wires in the middle section of the line exactly at the moment of a lightning stroke, particularly in the time interval

t (0.11; 0.14) s.

The oscillogram illustrating voltage variations across T1 clearly shows an immediate response to a lightning strike against the wire. A sharp pulse of a maximum voltage peak up to around −7 MV promptly follows the strike, indicating a very high lightning current and a fast potential rise at the strike point. The pulse slope rises very steeply while its duration is barely several dozen microseconds; the voltage passes to a damped oscillatory process after that. The amplitude of these oscillations gradually declines to reach 1 MV and vanishes in time.

The oscillogram for T2, not directly struck by lightning, shows the induction of an EMF reaching −800 kV. This voltage level is a direct result of electromagnetic induction and coupling with T1, directly struck by lightning. The voltage is clearly oscillatory, the oscillations concentrate on the first 1–2 ms after the strike, and then the amplitude gradually shrinks. This indicates an effective energy transfer between the line elements via the electromagnetic field, even if there is no direct current contact with the lightning.

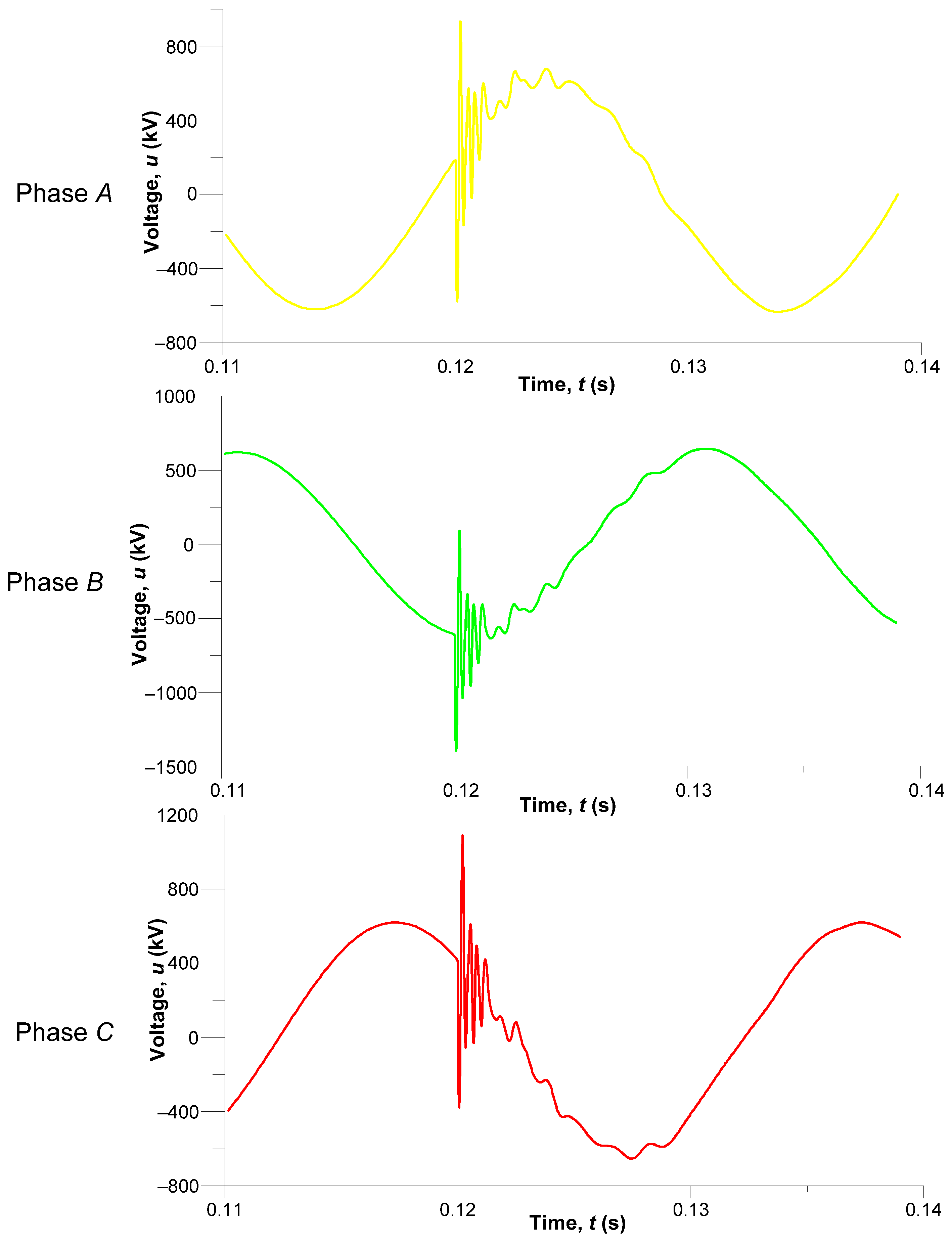

Figure 13 shows transient voltages across phase wires along the middle section of the line exactly at the moment of a lightning strike, particularly in the time interval

t (0.11; 0.14) s.

The phase A oscillogram (yellow line) represents the pulse voltage rise to 900 kV in a moment of 0.1202 s, i.e., nearly immediately following the lightning strike against T1; the phase A voltage is 1.4 UMCOV—maximum continuous operating voltage. This indicates a dangerous overvoltage that may potentially lead to a phase insulation breakdown. The shape of the voltages includes a characteristic high-frequency component that overlaps the sinusoidal basic frequency voltage. On reaching its peak value, the voltage gradually returns to its normal sinusoidal condition.

Although there is no direct lightning strike in phase B (the green line), the voltage is clearly pulsed and reaches its maximum of about 1.4 MV. The pulse is generated by the operation of the law of induction.

The phase C voltage (the red line) reaches its maximum of 1.1 MV after the lightning strike. Like the other phase voltages, it is briefly oscillatory, quickly damped, and transitions to its sinusoidal condition.

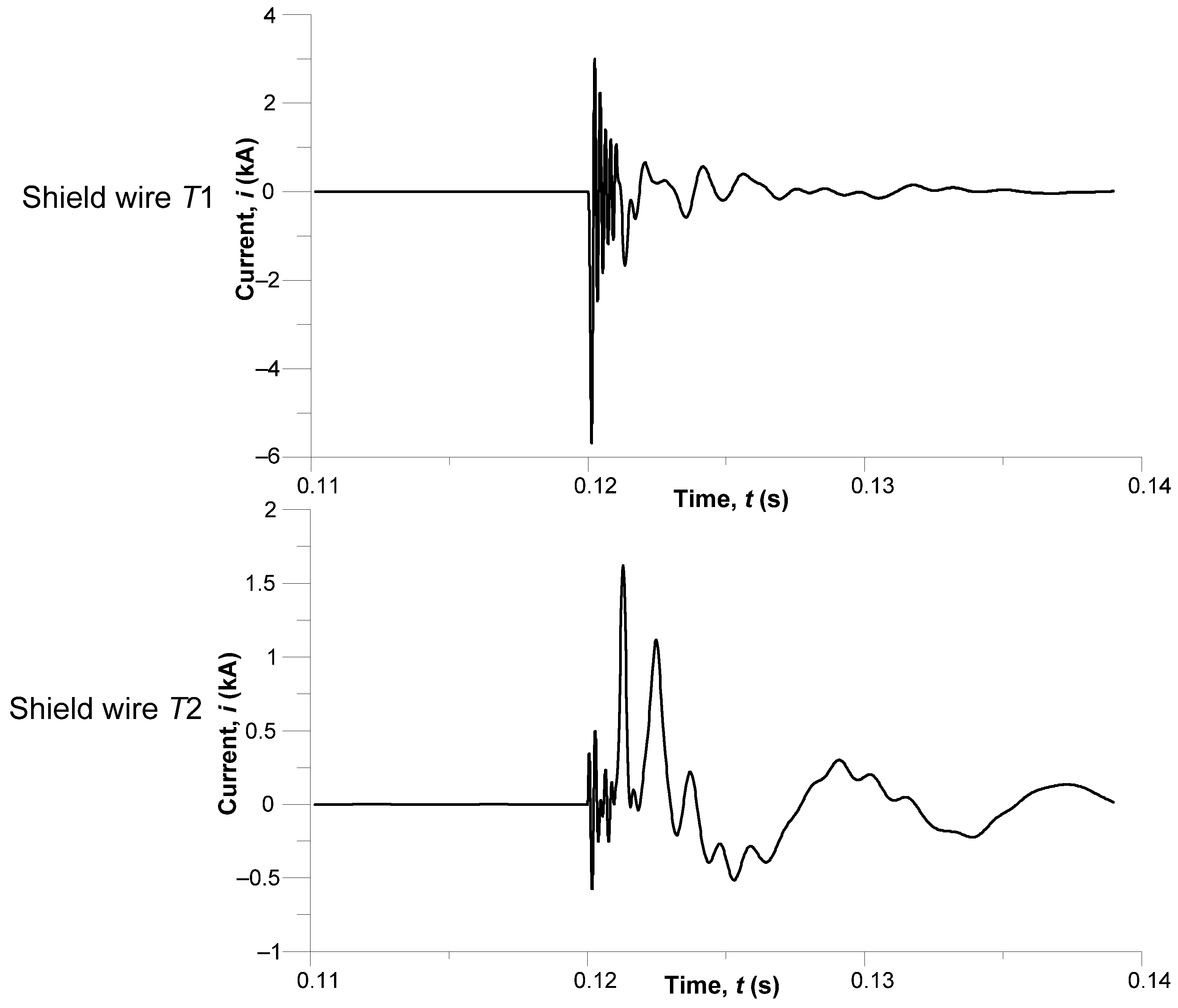

Figure 14 shows transient currents in the lightning shield wires in the mid-span of the line exactly at the moment of a lightning strike, particularly in the time interval

t (0.11; 0.14) s. The oscillograms in

Figure 14 present the nature of current variations across each line wire following the lightning strike against

T1.

For T1, the current pulse rises very steeply to reach nearly −6 kA immediately after the lightning strike at t = 0.12 s, followed by a damped oscillatory process continuing for about 10 ms. This current waveform is typical for the lightning current model, with a current rising steeply for a short time.

Current begins to flow across the adjacent shield wire T2, too. Its initial amplitude, caused by electromagnetic coupling between the wires, is far lower, at approximately 0.5 kA. The current across T2 reaches its peak as the current wave from T1 reaches the end of the line, bounces, and overlaps the current generated by the induced EMF. In effect, the current across T2 in the middle section of the line reaches 1.7 kA and vanishes with a certain aperiodic component.

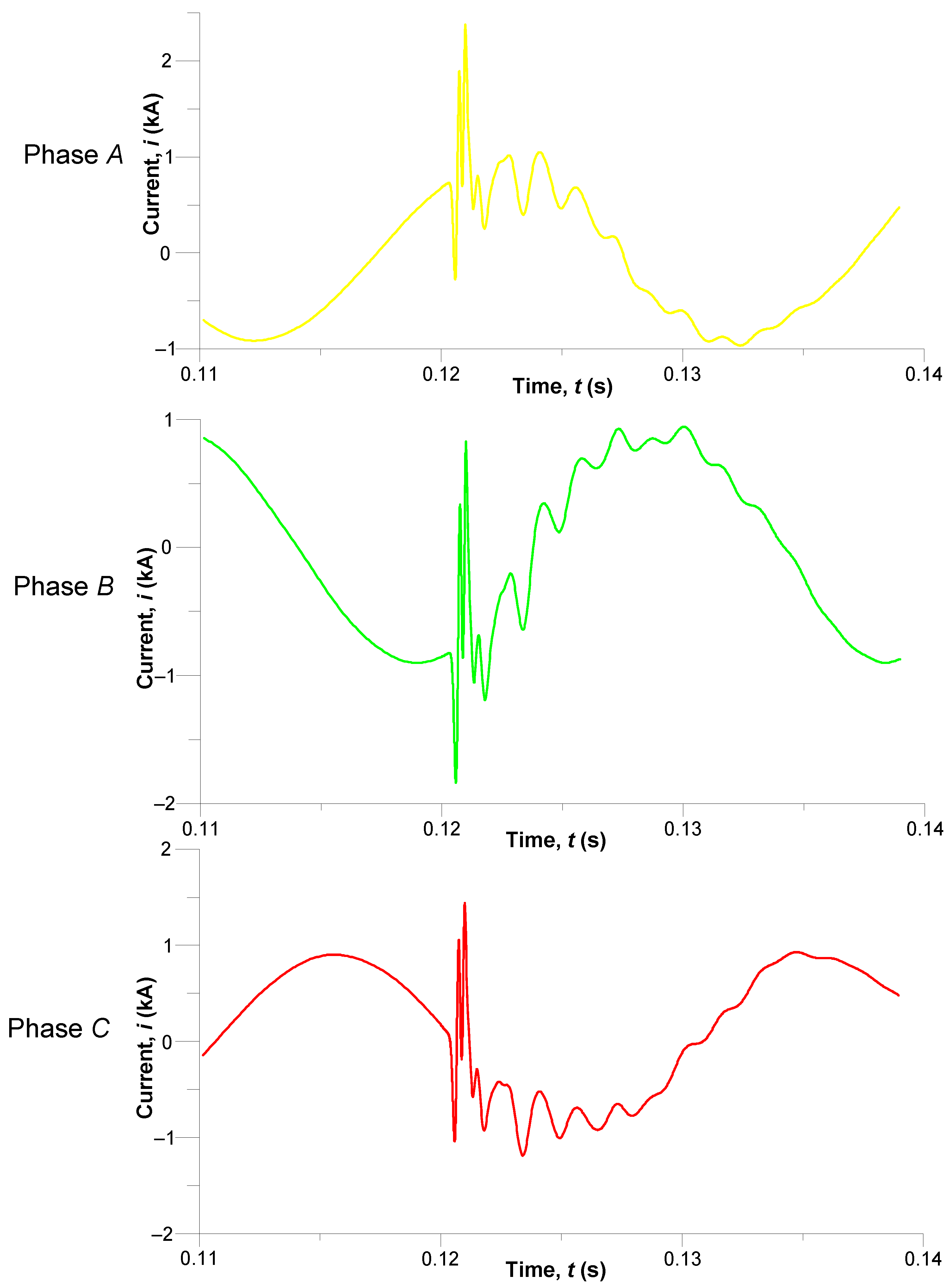

Phase current processes in the middle section of the line as lightning strikes

T1, particularly in the time interval

t (0.11; 0.14) s, are depicted in

Figure 15.

A current pulse of amplitude 2.4 kA, overlapping with the main sinusoid, can be observed in phase A (the yellow line). Such an excess pulse component may cause additional energy losses across active parts.

In phase B (green line), the pulse is less intense. It extends the oscillatory process, which is evidence of the line’s high sensitivity to external interference.

The initial pulse current has an opposite polarity and is an asymmetrical, gradually damped response in phase C (the red line). This suggests complex electromagnetic interactions between the phase wires, particularly the presence of some mutual effects of electromagnetic pulses.

All three phase wires display the characteristic dynamics of alternating current, suggesting that the starting pulse propagates along the line and the phase responses are co-dependent. An instant response to the lightning pulse and a characteristic oscillatory damping are generally observed across all the wires, confirming a high electromagnetic coupling in the system.

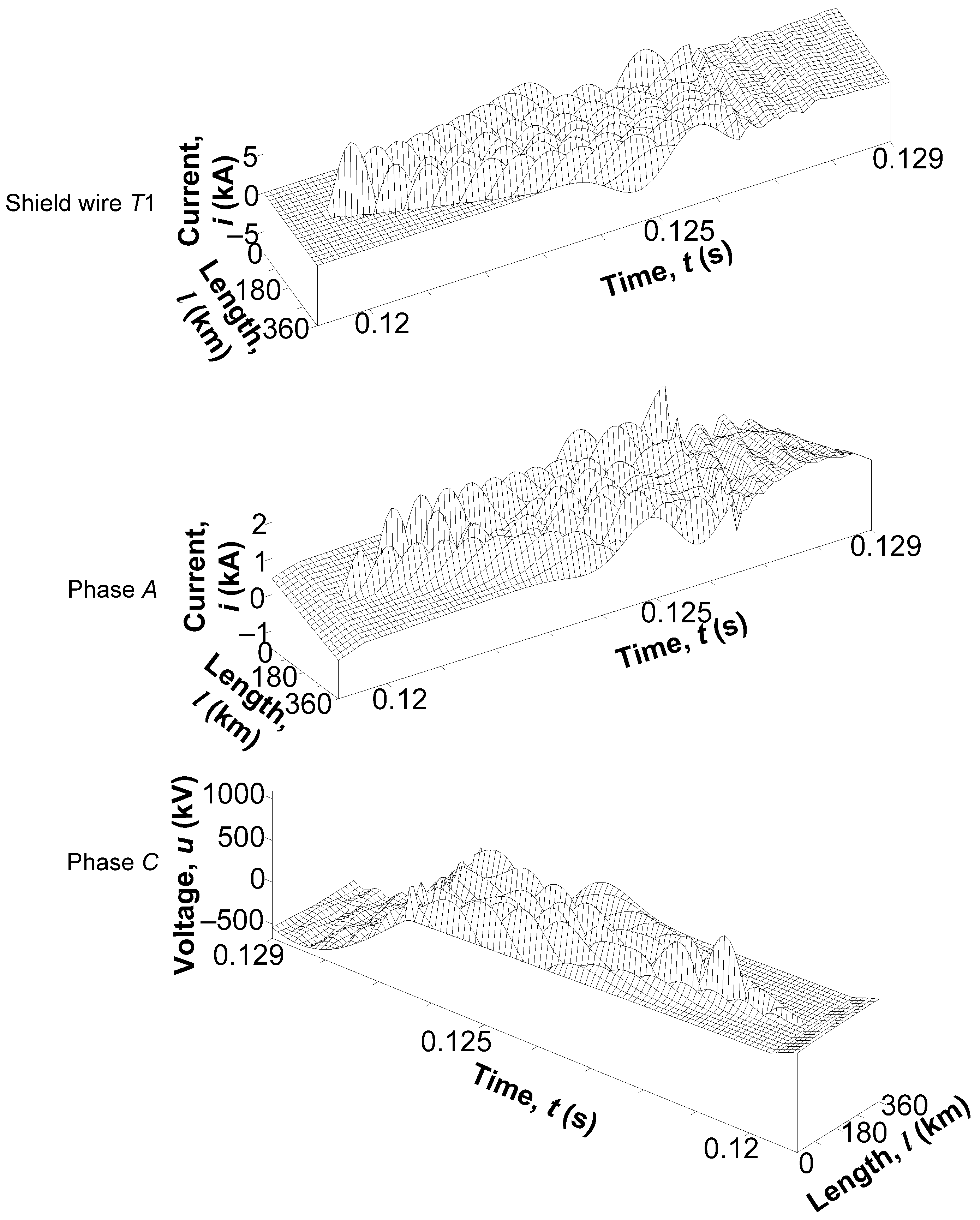

The possibility of plotting voltage and current oscillograms in 3D space, or temporal–spatial waveforms, is a key advantage of the mathematical model. Our field-circuit mathematical model allows for a 3D reproduction of temporal–spatial dependencies in the results of the model’s computer simulation. Such a representation provides for a more precise visualisation of transient processes. Such an approach serves not only to record amplitudes at specific points but also to visualise the dynamics of electromagnetic wave propagation along the line in time. It helps to understand the interactions between the wires and allows for the analysis of the processes of electromagnetic wave reflection and damping.

The temporal–spatial waveforms of currents across

T1 and phase

A wires and of voltages in phase

C are presented in

Figure 16.

Figure 16 clearly shows the wave background to the complicated electrodynamic processes across the power supply line. The areas of wave reflection, where the direction of propagation changes due to heterogeneous or varying boundary conditions, are clearly observable. Multiple wave reflections can be observed in the phase wires, suggesting the possibility of different-phase waves superposing. Likewise, current across

T1 exhibits non-symmetrical pulses that indicate the absence of earthing—

T1 is insulated along its entire length from the earth.

The analysis of the resulting temporal–spatial waveforms allows for a clear tracking of the dynamics of electromagnetic wave propagation along the line in time and space, which is important for detecting wave reflection and superposition effects.