Abstract

The research process was based on an analysis of an existing building equipped with a heat pump on which photovoltaic panels were installed; then, based on energy consumption, the investment profitability was evaluated. In this research, using the available data, the coefficient of self-consumption of energy from the PV installation, the potential index of the installation’s own needs coverage, and the index of energy use from photovoltaic modules were determined, which in practice is equated with the energy efficiency of the PV installation. The entire investment was subjected to simulation and field tests to determine the energy demand of a single-family building. The main aim of this work was to check whether a system equipped with a heat pump combined with a PV installation is an effective technical solution in the analysed climatic conditions in one of the countries of Central and Eastern Europe. In addition, both positive and negative aspects of renewable energy sources were analysed, including long-term financial savings, energy independence, and reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. It has been shown that the described solution is characterised by high initial costs depending on weather conditions. The installation presented would allow us to avoid 1891 kg/year of CO2 emissions, which means that with this solution, we contribute to environmental protection activities.

Keywords:

PV panels; heat pumps; energy efficiency; renewable energy; synergy effect; research study 1. Introduction

The contemporary goal of housing construction is to follow the trend of saving energy and reducing emissions of harmful substances into the natural environment. Observations of the reality surrounding us indicate the effects of the transformation taking place in this area in the form of, among others, better insulation or equipping buildings with recuperators that recover heat from the exchanged air. In addition, solutions based on intelligent electrical installations are promoted, which control devices in a way that optimises energy consumption. In practice, all the changes described above also result in the desire to use cheap energy. One of the mentioned methods of obtaining cheap energy is the use of sunlight, which can be converted into electricity or heat energy in a relatively simple way [1,2,3]. Dynamically developing technology in both the areas of photovoltaic cells and solar collectors has increased the availability of these category solutions, thus enabling everyone to become an energy producer for their own needs.

It should be emphasised that individual photovoltaic power plants are an excellent solution for installations located far from the existing power grid infrastructure because they allow the use of technological solutions that were not possible before, thus enabling the construction of electrical technical facilities in places where, for example, the construction of power lines is economically unjustified. However, the barriers that currently prevent individual investors from widely using PV installations are usually high investment costs related to the construction of their own extensive PV systems, enabling the fulfilment of all energy expectations, and the relatively long payback period of such investments [4,5,6]. Therefore, the analysis of issues related to the assessment and implementation of investments based on the integration of several energy sources based on RES solutions is becoming an increasingly popular research topic.

This paper discusses the analysis of a hybrid-home photovoltaic power plant with an air-heat-pump system in order to reduce the costs of purchasing energy from the grid, using the example of individual housing construction. The choice of this category of construction was not accidental, because in this category of buildings, there is the greatest interest in solutions based on the integration of renewable energy systems. The scope of this work includes an analysis of energy production from a home PV installation. This research presents the basic technical specification of photovoltaic devices, the main components of the system, and related technical parameters, which were used to simulate the compatibility and effectiveness of the combination of a PV system and an air heat pump in a single-family house. Based on the presented concept, the profitability of investing in a power plant project was analysed in light of the current energy settlement rules for home photovoltaic installations. By using data balancing, electricity is taken from the grid, fed into the grid, and data are directly stored in the inverter’s memory regarding the production of electricity by photovoltaic modules. The conditions identifying the extent to which electricity is used in a household equipped with a heat pump have been defined. The obtained results allowed for the assessment of the profitability of the analysed investment in the climate conditions prevailing in one of the countries of Central and Eastern Europe. In practice, the presented conclusions can be used for the optimal selection of energy storage for this type of renewable energy installation.

Therefore, the presented discussion sheds new light on the issue of assessing the integration of energy sources from a PV system and an air heat pump. To our knowledge, this is the first approach to this topic, which includes a synthetic analysis of the implementation of investments in the mentioned energy sources on the example of a selected case study—a single-family house covering the prevailing climatic conditions in Central and Eastern Europe. The presented considerations provide new qualitative and quantitative data in the area of rationalisation of obtaining cheap energy—taking into account economic criteria in terms of expenditure incurred and returns on this investment—and thus provide recommendations for selecting energy storage dedicated to this category of renewable energy installations. The presented research, therefore, fills the gap in the literature, bringing a new, fresh perspective on the topics of (I) energy efficiency, (II) photovoltaic panels, (III) system integration, (IV) heat pump installation, (V) economic analyses, and (VI) energy storage.

The article is organised as follows. Section 2 presents a detailed description of the research approach based on the recent literature on the topic. Section 3 describes the research methodology used. Section 4 presents the experimental results and their interpretation; this chapter focuses on presenting research results and assessing the functioning of individual systems. In addition, a discussion of the results is presented, devoted to an in-depth and critical analysis of the results obtained in terms of their reality and significance. Section 5, in turn, covers research conclusions, indicating their limitations, practical applications, and future research directions in this field.

2. Review of the Literature in the Context of the Research Problem

As the literature on the subject indicates, the integration of a photovoltaic installation with a heat pump is an innovative and increasingly common approach in individual construction, which focuses on self-sufficiency, ecology, and energy efficiency. Such synergy allows you to optimise the use of solar energy, transforming it into heat and electricity to power your home, which translates into a reduction in heating costs and other energy bills [7,8,9]. In many Central and Eastern European markets, there are forms of financial support available that help reduce the initial financial outlay needed to install such a system, making the investment more affordable. The use of a heat pump combined with a photovoltaic installation seems to be an effective solution for households, potentially leading to a significant reduction in costs related to heating and electricity consumption, stabilising expenses, and bringing long-term benefits for many years [10,11,12,13]. The heat pump uses renewable energy sources to provide heating to the building and access to hot water, but requires electricity to power it. In turn, a photovoltaic installation allows you to obtain electricity from sunlight and directly powers a heat pump and other electrical devices. The combination of these two technologies allows you to create a complete system that can operate independently of conventional energy distribution sources [14]. This solution can lead to a significant reduction in energy bills and significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions. It is worth noting that the investment of combining a heat pump with a photovoltaic installation involves significant financial outlays at the stage of installing the system itself, but in practice, the return should be made in the long run [15,16,17]. Exact payback time for invested financial outlays depends on many factors, such as the price of electricity at a given moment, the costs of installation and maintenance of the system, as well as climatic conditions and energy consumption in the building.

Practice shows that the photovoltaic installation itself can be used to power the heat pump by using surplus electricity [18]. However, it should be remembered that it is in the summer that electricity from photovoltaics is produced in the largest quantities, when household demand for thermal energy decreases [19]. Therefore, in the warmest months, the electricity generated by photovoltaic panels can be used to power a heat pump, which can be used, for example, to heat domestic water. The expenses related to powering and operating the heat pump depend on the pump’s power, demand for hot water, electricity consumption, and many other factors [20,21]. However, electricity consumption depends mainly on the energy class of the building and the degree of its thermal insulation. In theory, having a photovoltaic installation with appropriate power will reduce the costs of powering the heat pump to zero, and the electricity generated by the photovoltaic panels will cover the entire electricity demand of the pump.

The key issue for selecting a PV installation is determining how much electricity the heat pump will consume. If it is already installed in the house where photovoltaic panels are to be additionally installed, this process seems to be easier in terms of methodology. Modern heat-pump controllers have built-in energy consumption metres [22,23,24,25,26,27]. All that remains is to read the value for the entire year of operation of the device in the space-heating and domestic-hot-water heating modes. However, for a new, designed building, accurate thermal calculations should first be performed. Then the expected heating needs of the building are known, to which the estimated hot water needs for the number of inhabitants can be added. In the case of a modernised building, thermal needs are usually determined through an energy audit. Then the amount of energy in kWh/year is known, which allows you to select the heating power of the heat pump and photovoltaic installation. You can also make calculations of heat needs based on the costs of purchasing the fuel that would be incurred when operating the old heat source. However, the efficiency of the boiler to be replaced must be determined or at least assumed.

In one of the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, Poland, the methodology for selecting the power of a photovoltaic (PV) installation is often based on the energy consumption of the heat pump. For every 1000 kWh/year of energy consumed by the pump, a power of 1 kWp of the PV installation is recommended. Based on the heating power of the heat pump, you can approximately select the appropriate power of the PV installation, which is usually from 0.5 to 0.8 kWp for each 1 kW of heating power.

Many studies have been carried out to increase the self-consumption of photovoltaic energy by controlling the operation of heat pumps using a building energy management system (BEMS) [28,29,30]. Similarly, the study [31] used various strategies to control battery operation to improve photovoltaic self-consumption. These strategies include the following: a daily dynamic feed-in limit based on ideal forecasts, a fixed 70% feed-in limit, and maximising self-consumption. Other research results [32,33,34] show that the first strategy outperforms the others, with energy consumption for PV’s own needs above 78%. The combined operation of the heat pump, battery energy storage, and thermal energy storage reduces PV’s limitation by up to 21%. Disaster recovery-based techniques can be used in buildings to control bidirectional energy flow while operating in a grid-connected mode. In turn, in the study [35,36,37,38], the authors indicate the possibility of optimally selecting the power of the PV installation for individual needs. At the same time, they consider various variants of the operation of such an installation, including its location and tracking of solar radiation. The analysis in this work was performed on experimental data regarding electrical load, ambient temperature, and solar radiation intensity. Using these factors, the optimal performance of the on-grid photovoltaic system was assessed based on maximising its own energy consumption, which can cover the load demand of the analysed household. The heat pump is by far the largest source of electricity consumption, affecting the self-consumption rate the most among all devices powered by this energy in a building. Previous research shows that adding a heat pump to photovoltaics may lead to an increase in auto consumption in a standard household by up to 50÷60% [39]. The authors kept this in mind and decided to research whether such a solution is equally effective in the moderate climate conditions of one of the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, which will help future investors make key decisions based on the scientific evidence that investments in this type of hybrid combination of renewable energy sources can be economically profitable and energy efficient.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Assumptions for Research

At the first stage, the daily demand for electricity in the household was defined. The data presented in Table 1 are based on our own observations and measurements. Table 1 lists all electrical devices used regularly, provides the nominal power of each of them as well as operating time in hours per day, and calculates the daily energy consumption using the following formula:

where

E = P × t, Wh

- E—daily energy consumption, Wh;

- P—nominal power, W;

- t—working time per day, h/day.

Table 1.

Daily demand for electricity in the household.

Table 1.

Daily demand for electricity in the household.

| Rooms | Electrical Devices That Consume Electricity | Nominal Power, W | Working Time per Day, h/day | Daily Energy Consumption, Wh/day |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kitchen | Electric kettle | 2000 | 0.5 | 1000 |

| Microwave oven | 1500 | 0,5 | 750 | |

| Refrigerator | 600 | 10 | 6000 | |

| Coffee machine | 750 | 0.33 | 247.5 | |

| 2 lamps | 60 × 2 = 120 | 5 | 600 | |

| Salon | TV set | 150 | 3 | 4 |

| 1 lamp | 40 | 3 | 120 | |

| Bathroom | Dryer | 1200 | 0.33 | 396 |

| 2 lamps | 2 × 40 = 80 | 3 | 240 | |

| Washing machine | 2000 | 2 | 4000 | |

| Bedroom 1 | Reading lamp | 40 | 2 | 80 |

| TV set | 150 | 2 | 300 | |

| Charger for phone | 1.5 | 2 | 3 | |

| Bedroom 2 | Night lamp | 10 | 0.33 | 3.3 |

| TV set | 150 | 2 | 300 | |

| Charger for phone | ||||

| Iron | 1.5 | 2 | 3 | |

| Utility room | Eco-pea stove | 1200 | 0.5 | 600 |

| 15,066.80 | ||||

By adding up the total daily electricity consumption in Wh, the resulting value is 15,067 Wh; if this is converted into kilowatt hours, the daily energy consumption will be 15.07 kWh. The price for 1 kWh of electricity from the distributor is 0.26 EUR/kWh. Knowing the following data, daily, monthly, and annual electricity costs were estimated:

- Costs of daily energy consumption [EUR] = 3.92;

- Costs of monthly energy consumption [EUR] = 118;

- Costs of annual energy consumption [EUR] = 1416.

- Parameters of the analysed installation:

- Building type: single-family house with an area of 100 m2;Type of heat pump: air (installed);

- Generator power PV: 8.05 kWp;

- Generator area PV: 22.2 m2;

- Number of inverters: 1;

- Tilt: 25°;

- Orientation West: 265°;

- Dimensioning factor: 113.8%;

- Configuration MPP 1: 1 × 10;

- Number of phases: 1;

- Mains voltage (single phase): 230 V;

- Power factor (cos phi): +/−1;

- Installation efficiency: 75–90%.

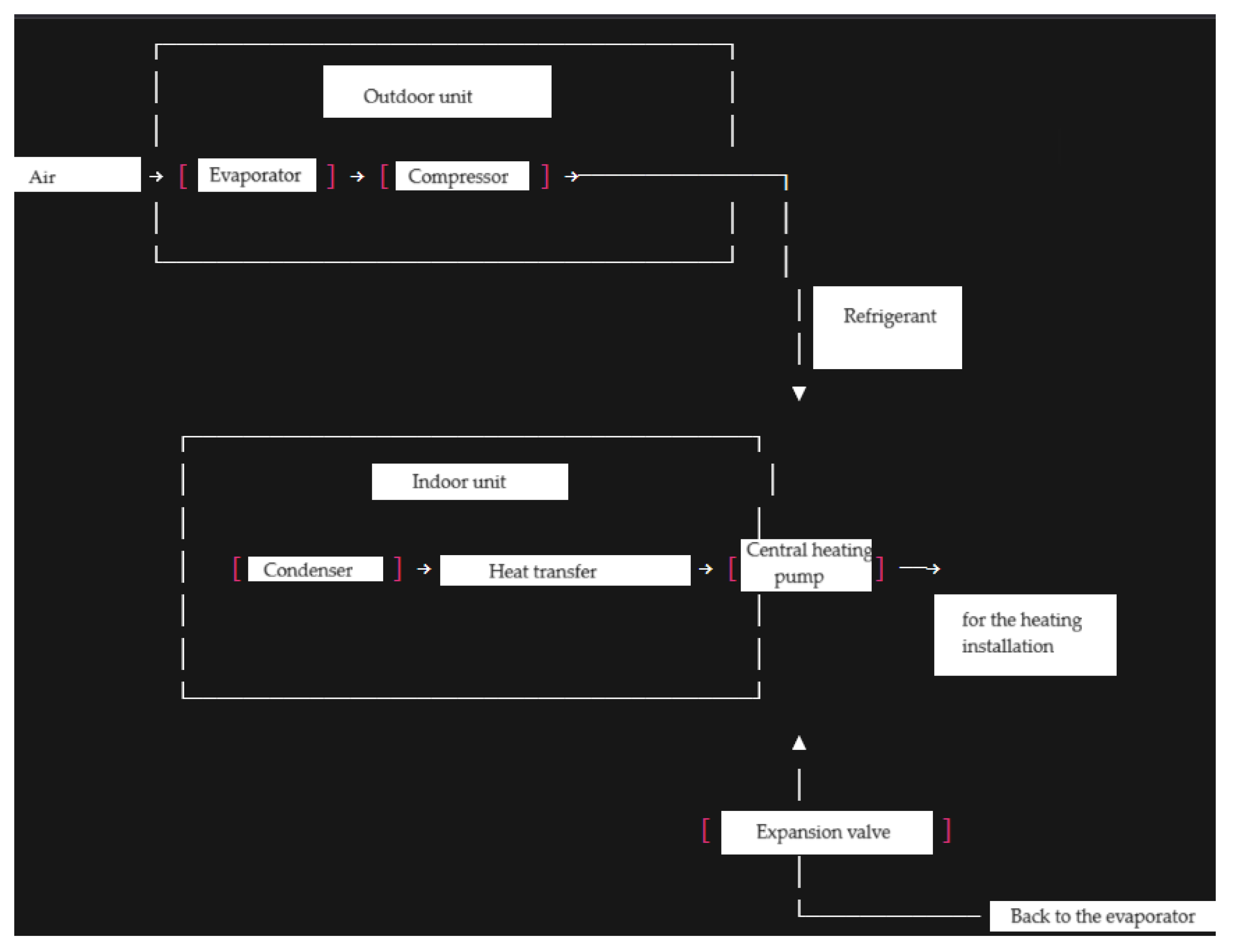

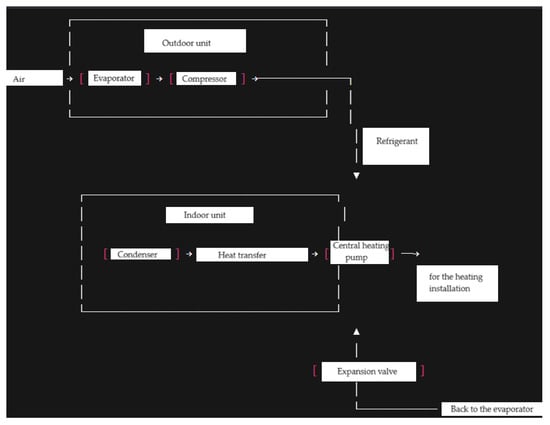

Figure 1.

Heat pump installation—illustrative photos.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of a heat pump in a building.

As part of this study, calculations were performed for a single, coherent model of an 8.05 kW installation, considering orientation, tilt angle, shading, and module degradation. Additionally, time series COP/SPF were determined for this installation using a binary method, separating loads into heating and domestic hot water, taking into account outdoor temperature and defrosting processes. Based on the obtained data, a tariff table was developed, including retail and export energy prices, fixed charges, inflation, discount rates, system lifespan, inverter replacement, and warranty degradation. Further research focused on key indicators: self-consumption (SCR), energy self-sufficiency (autarkic), load coverage ratio, peak-power-to-PV-power matching, and power plant capacity share. The final result of the analyses was the determination of the economic indicators NPV, IRR, and DPB, as well as an assessment of billing policy options (including net billing). Consolidated energy yields (P50/P90) and cost ranges (±) were also developed.

3.2. Research Program

This project aims to build a photovoltaic installation connected to the on-grid network (it involves storing electricity at the distributor) with a capacity of 8.05 kW. The installation consisted of 23 photovoltaic modules of the LR6-60OPH 350M model with a very high efficiency of 350 Wp. We provide a 25-year performance warranty. The installation was located in one building. The installation was oriented south at an angle of 35°, and a 6 kW inverter was installed on the building, to which all panels were connected. Before installing the panels on the roof, measurements of the installation space necessary to achieve the intended purpose were made; the dimensions of a single panel are 1762 mm × 994 mm × 35 mm. Table 2 lists the parameters of a single photovoltaic panel of a given model. Figure 3 shows a diagram of the analysed panel along with a technical description.

Table 2.

Parameters of a single piece of LR6-60OPH 350M photovoltaic panel [37].

Figure 3.

Percentage of energy losses resulting from shading of the roof surface.

- Technical specifications of the inverter:

- Dimensioning factor: 113.8%;

- Configuration: MPP 1: 1 × 10, MPP 2: not covered;

- AC network—number of phases: 3;

- Mains voltage (single phase): 230 V;

- Power factor (cos phi): ±1.

The inverter’s task is to convert electricity generated in photovoltaic modules in the form of direct current and voltage into energy with parameters occurring in the facility’s electrical installation. One Huawei inverter was used in the designed installation. The Huawei SUN2000-6KTL-M1 inverter (Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) is designed to work with a three-phase electrical installation and is characterised by the parameters shown in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3.

AC parameters for the Huawei SUN2000-6KTL M1 inverter.

Table 4.

DC parameters for the Huawei SUN2000-6KTL-M1 inverter.

Figure 3 shows two panel areas: the left part of the roof, with panels marked 1.1.3 to 1.1.11, is string 1. The right part of the roof, with panels marked 1.1.1 and 1.1.2, is the second section, the beginning of the next system. A string in a photovoltaic installation refers to series-connected groups of PV panels that form a single electrical circuit that supplies power to the inverter. Figure 3 presents a roof shading analysis, with percentages indicating the annual shading level for individual panels or roof sections. Values such as 1.4%, 0.7%, and 0.5% mean that in a given location, the surface is in shade for 1.4% of the year or loses approximately 1.4% of its energy due to shading.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Photovoltaic System Configuration

When configuring a photovoltaic system, an important issue is to calculate the voltage at high and low temperatures and the direct current intensity that may appear in the photovoltaic circuit in extreme solar radiation intensity. It is assumed that the photovoltaic module can reach a temperature of up to 70 °C during a very hot day and start working on cold mornings at temperatures of −25 °C. To determine the power of a photovoltaic installation, the number of panels, the power of a single module, and the power of the photovoltaic installation should be taken into account, which can be calculated using the following formula:

where

PPV = LM × PSTC PV

- PPV—power of the photovoltaic installation, Wp;

- LM—number of photovoltaic modules in the entire installation, piece;

- PSTC PV—power of a single photovoltaic module, Wp.

For the analysed installation, the following was obtained:

PPV = 23 piece × 350 Wp = 8050 Wp = 8.05 kW

The power of the photovoltaic installation is 8.05 kW.

The next step is to calculate the minimum and maximum number of modules connected in series and parallel to properly configure the photovoltaic system. To achieve this, determine the voltage change per 1 °C using the following formula:

where

ΔU = β × U0C

- ΔU—voltage change on 1 °C, V/°C;

- β—temperature coefficient of open-circuit voltage, %/°C;

- U0C—open-circuit voltage, V.

For the analysed installation, the following was obtained:

ΔU = 0.286 × 38.5 = 0.110 V

The voltage change is 0.110 V per 1 °C. From this data, the voltage at extreme temperatures can be calculated. The next step is to calculate the open-circuit voltage at −25 °C for a single module according to the formula below:

where

V0C–25 = V0C + (Δv × ΔT1)

- V0C–25—module open-circuit voltage at temperature −25 °C, V;

- V0C—module open-circuit voltage under standard measurement conditions, V;

- ΔT1—temperature difference between normal conditions and design conditions, °C;

- Δv—temperature coefficient of voltage, %/°C.

For the analysed installation, the following was obtained:

V0C–25 = 38.5 + (0.110 × 50) = 43.80 V

The calculated voltage is 43.80 V.

Then, the voltage at the maximum power point at 70 °C of a single module was calculated using the formula:

where

VMPP+70 = VMPP − (ΔV·ΔT2)

- VMPP+70—module operating voltage at +70 °C, V;

- VMPP—module voltage at the point of maximum power under normal conditions, V;

- ΔV—voltage change to 1 °C, V/°C;

- ΔT2—temperature difference between calculation conditions and normal conditions, °C.

VMPP+70 = 31.8 − (0.110 × 45) = 26.85 V

For the analysed installation, the following was obtained:

The determined voltage is 26.85 V.

Then, count the minimum number of modules that can be connected in one chain in series, according to the following formula:

where

- —minimum number of modules in the chain, pieces;

- —inverter starting voltage, V;

- —module operating voltage at +70 °C, V.

A minimum of six PV panels can be connected into a single chain.

Then, the opposite needs to be calculated, i.e., the maximum number of modules that can be connected in one chain in series, using the following formula:

where

- —minimum number of modules in the chain, pieces;

- —maximum input voltage on the inverter, V;

- —no-load module voltage at −25 °C, V.

For the analysed installation, the following was obtained:

The maximum number of photovoltaic modules in one chain is 22 pieces.

The installation uses a parallel connection. According to the formula, we calculate the maximum number of module chains in parallel connection:

where

- —maximum number of strings connected in parallel on the inverter, pieces;

- —maximum input current per MPPT of the inverter, A;

- —current intensity at the maximum power point of the module, A.

For the analysed installation, the following was obtained:

A maximum of one chain can be used in a parallel connection.

Below is a complete method for calculating the annual production of a 23-module PV installation (8.05 kWp), taking into account: orientation (azimuth), tilt, shading, and annual degradation.

- Input: 23 modules with a total power of 8.05 kWp;

- Average power per module ≈ 350 W (8050 W/23 ≈ 350 W);

- The reference value was adopted → 1050 kWh/kWp/year;

- The azimuth assumed was 210°(southwest)→ −3%;

- Tilt: 25° → −2%;

- Shading: moderate (chimneys/trees) → loss −8%;

- Module degradation: 0.6%/year.

Annual production = kWp × kWh/kWp/year

P_0 = 8.05 kWp × 1050 kWh/kWp = 8452 kWh/year

- Correction for orientation + slope

Total geometric correction:

- Orientation—210° × 0.97;

- Slope—25° × 0.98.

k_geom = 0.97 × 0.98 = 0.951

P1 = 8452 × 0.951 = 8038 kWh/year

Shading correction:

- Assumption: moderate → −8% → ×0.92.

P2 = 8038 × 0.92 = 7394 kWh/year

Degradation of modules in the following years. Annual demotion accepted: 0.6%/year.

Production in year n:

P(n) = P2 × (1 − 0.006)ⁿ

- Year 1—7394 kWh;

- Year 5—7394 × 0.971 ≈ 7173 kWh;

- Year 10—7394 × 0.943 ≈ 6970 kWh;

- Year 20—7394 × 0.889 ≈ 6564 kWh;

- Comparison to consumption 3487 kWh/year;

- Coverage of energy consumption PV = 3487/7394 ≈ 47%.

The installation produces approximately twice the annual energy demand, i.e., approximately 3900 kWh more than required. The excess energy will be sent to the grid (net-billing) or to storage, depending on the configuration. Over 10 years, production will decline by approximately 6%, but it will still be more than twice the consumption. Optimal PV power should be selected for consumption; the ideal installation would be around 3.5–4 kWp. However, the analysed installation provides higher production and a slower decline in profitability.

4.2. Analysis of the Effects of Using a Photovoltaic System to Power a Household

In order to estimate the profit resulting from installing a photovoltaic system, many factors must be taken into account. The manufacturer of the panels used to complete the project guarantees that the panels will work at a power level of 83% after 25 years. This is because the initial power of the panels works at the level of 97% and the annual decline in work is 0.55%. The following formula was used to calculate the estimated yield over the applicable warranty period:

where

- E—energy yield, kWh;

- —initial installation power, Wp;

- —number of warranty years, years;

- —power level after the warranty period, %;

- —initial power level, %.

For the analysed installation, the following was obtained:

The calculations show the yield from only one panel during the warranty period. To obtain the total yield from all panels, perform calculations using the formula:

Knowing the yield from the entire installation over a period of 25 years, how much energy the installation will produce annually, Ep, can be calculated. The formula used for calculation is as follows:

For the analysed installation, the following was obtained:

To sum up, the designed installation will produce 7245 kWh per year, while the annual demand for electricity in the example farm is 1297.2 kWh, which means that the designed installation will generate approximately 6 times more electricity. The installation will be connected to the on-grid network, i.e., excess energy generated will be stored in the network. To recover the costs of the entire installation more quickly, excess energy generated can be sold back to the grid.

4.3. Simulation Results

- During the tests performed, the following was obtained:

- PV installation

- PV generator power: 8.05 kWp;

- Yield reduction due to shading: 3.2%/year;

- Energy fed into the grid: 3823 kWh/year;

- Consumption in standby mode (inverter): 10 kWh/year;

- Avoidable CO2 emissions: 1891 kg/year.

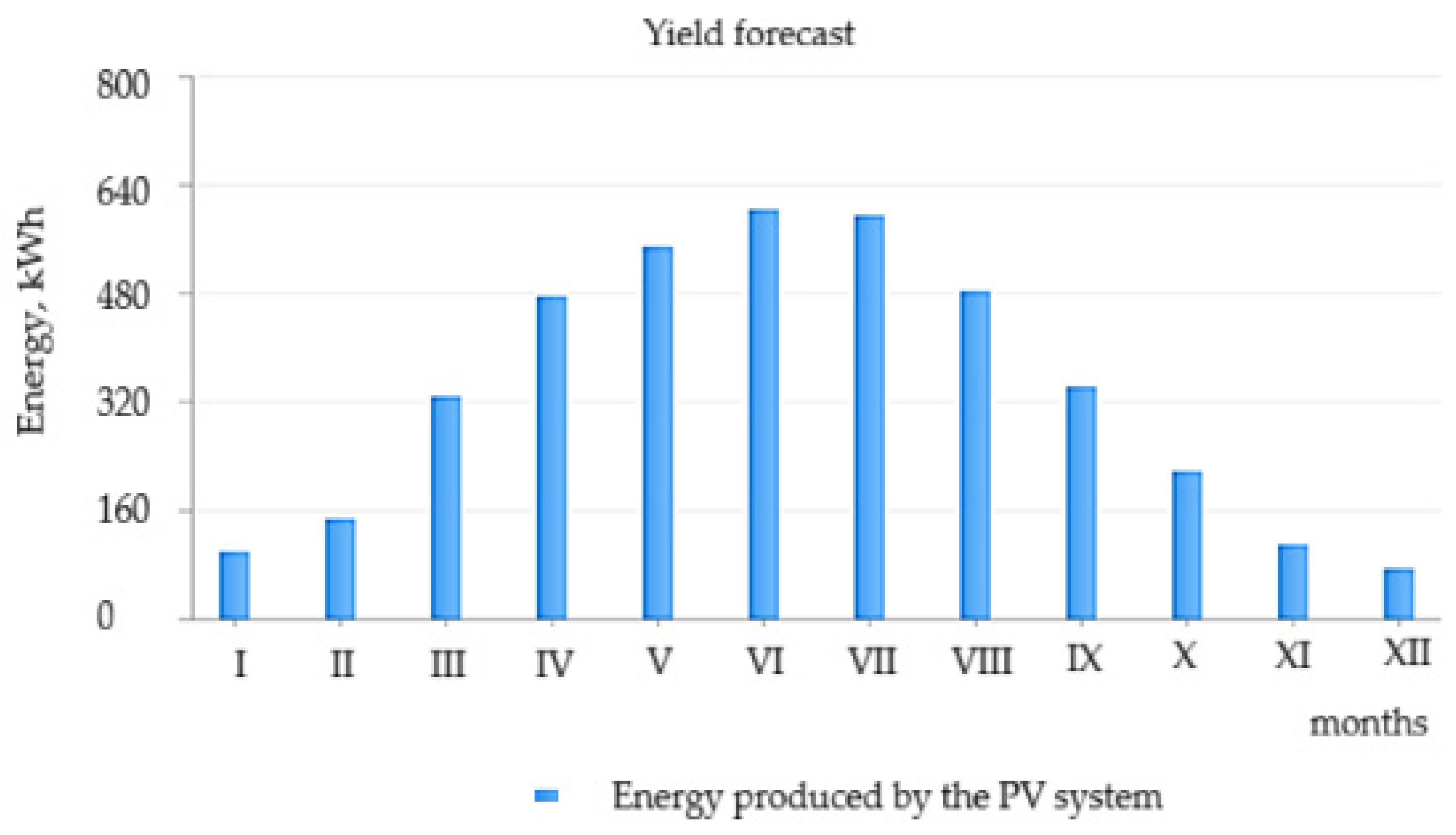

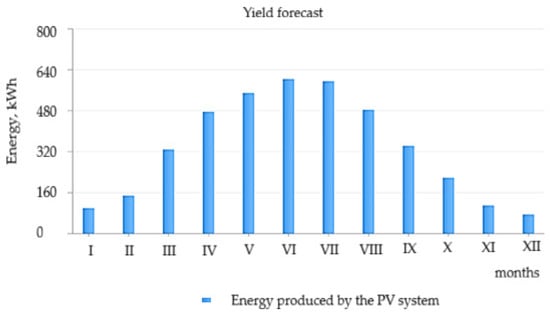

- Figure 4 shows the power output for the ammalized installation.

Figure 4. Yield forecast.

Figure 4. Yield forecast.

- 2.

- Obtained research data sheet:

- Mechanical data:

- -

- Width: 1052 mm;

- -

- Height: 2112 mm;

- -

- Depth: 35 mm;

- -

- Frame width: 35 mm;

- -

- Weight: 24.5 kg.

- U/I parameters with standard:

- -

- Voltage in MPP: 41.82 V;

- -

- Current intensity in MPP: 10.88 A;

- -

- Rated power: 455 W;

- -

- Efficiency factor: 20.48%;

- -

- Open-circuit voltage: 49.85 V;

- -

- Short-circuit current: 11.41 A;

- -

- Fill factor: 79.99%;

- -

- Open-circuit voltage boost before stabilisation: 0%.

- Part load parameters U/I:

- -

- Sunlight: 200 W/m2;

- -

- Voltage at MPP at partial load: 40.7 V;

- -

- Current intensity in MPP at partial load: 2.18 A;

- -

- Open-circuit voltage at partial load: 46.9 V;

- -

- Short-circuit current at partial load: 2.28 A;

- -

- Voltage ratio: −136 mV/K;

- -

- Current factor: 5 mA/K;

- -

- Power factor: −0.35%/K;

- -

- Angle of incidence ratio: 98%;

- -

- Maximum system voltage: 1500 V.

The value of the installation after taking into account subsidies and relief is presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Value of the installation after taking into account government subsidies and reliefs.

The payback time is shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Payback time on the investment.

PV*SOL 2026 Valentin software was used to calculate the numerical values; this is a professional software for the design, simulation, and analysis of photovoltaic (PV) systems, created by Valentin Software. The program enables the following: precise modelling of PV installations (rooftop, ground-mounted, and hybrid); simulation of energy production taking into account shading, orientation, and climatic conditions; economic and financial analysis of the investment; creation of reports and 3D visualisations. The basic results of the economic measures of the presented problem analysis are included in Table 7, Table 8, Table 9, Table 10 and Table 11.

Table 7.

Annual cash flows: savings + sales revenue.

Table 8.

Economic metrics for PV 8.05 kWp installations: ROI, NPV, IRR.

Table 9.

Basic performance indicators for PV 8.05 kWp installations.

Table 10.

Comparison of policy scenarios.

Table 11.

Summary of key uncertainties.

Discounted payback period (DPP): 10.3 years. NPV (25 years, 4%): +EUR 3715. The system generates real economic value, IRR: 8.8–9.5%. This is a very good rate of return compared to other investments with similar risk. An 8.05 kWp installation generates a stable positive NPV. Profitability is significantly increased by high self-consumption (heat pump/storage) and rising energy prices. Replacing the inverter does not significantly impact the overall investment. Degradation is mild at 0.7%/year—after 25 years, the system still operates at ~85% capacity.

- Energy yields P50/P90 for PV 8.05 kWp:

- P50 (normal expected yield): P50 = 7245 kWh/year.

- P90—10% Lower Production (Conservative):

P90 = P50 × (1 − 0.10) = 6520 kWh

- P50–P90 difference:

Δ = 7245 − 6520 = 725 kWh

- Suggested error bars:

- Annual production—error bar: ±6%.

E = 7245 × 0.06 = 435 kWh

- The graph should show mid: 7245 kWh, min: 7245 − 435 = 6810 kWh, and max: 7245 + 435 = 7680 kWh.

- P90 Production—Error Bar: ±3% (more conservative)

- Minimum production value: ~6320 kWh;

- Maximum (unlikely): ~6720 kWh.

4.4. Assessment of Cooperation Between the PV System and the Heat Pump

Available research and reports indicate that more and more newly constructed single-family residential buildings are considering options for heat pumps and photovoltaics. Knowledge about these devices is increasing, and there is a common belief that a heat pump is a device that consumes more electricity than a heating device using traditional fuel. Therefore, it seems profitable to supplement the existing renewable energy installation with photovoltaic installations that provide free energy to power the heat pump. The heat pump uses renewable energy, but an important part of the equipment—the compressor—requires about 20% of electricity to function properly, which is almost free from photovoltaic panels. It draws energy from the sun through photovoltaic panels mounted on roofs, walls, or special supports. In addition, heat pumps used as part of central heating installations can also be used to heat domestic water, and the pumps are intended only for central installations; they only allow continuous and effective use of electricity [40]. Therefore, generating photovoltaic energy using a heat pump allows you to increase the use of all the electricity generated by photovoltaic panels for your individual needs. This makes investing in both types of installations more profitable, because in this case, potential users of the system do not cause losses by discharging excess electricity to the grid. At this stage of the discussion, it should be mentioned that heat pump installations themselves are very diverse; there are no typical solutions or repeatable options. Each installation project is a different technological undertaking. All the more so because its level of complexity is influenced by the fact that it is connected with a PV installation. It is worth mentioning that critics of combining heat pumps with photovoltaic installations emphasise that although photovoltaic panels produce energy in the summer, heat pumps are used the most in winter. There is a logical contradiction to this hypothesis. As a result, both installations would be considered ineffective; however, as previous research indicates, solar energy production in winter is not zero. Photovoltaic panels perform their work both at low temperatures and on days with very low sunlight.

Additionally, this study evaluated the performance of a heat pump with an 8.05 kWp PV system, categorised by heating, domestic hot water (DHW), seasonal coefficient of performance (SPF), and the impact of PVs on actual costs and self-consumption. Model assumptions include the following:

- -

- Photovoltaic installation with a capacity of 8.05 kWp and annual production of 7250 kWh/year;

- -

- Heat pump (air–water)—typical values: SPF (heating): 3.2–4.0, SPF (DHW): 2.0–2.7.

- Building demand: heating: 12,000 kWh of heat/year, DHW: 2000 kWh of heat/year. Electricity consumed by the heat pump: heating: Q = 12,000 kWh at SPF = 3.5. Energy consumption = approx. 3430 kWh/year.

- DHW: Q = 2000 kWh, SPF = 2.5. Energy consumption = approx. 800 kWh/year. Total heat pump power consumption ≈ 4200–4400 kWh/year PV compatibility 8.05 kWp—self-consumption and balance. Annual PV production ≈ 7250 kWh.

- Heat pump self-consumption with PVs: 25–40% (without storage and without hourly control). Estimated PV energy consumed directly by the heat pump: ≈ 1200–1700 kWh/year. The heat pump consumes ~4200 kWh/year, of which ~1500 kWh will be generated by PVs.

- In the net billing/net metering system:

- From PV (self-consumption): 1500 kWh → EUR 0;

- From the grid: 2700 kWh → paid.

If grid electricity costs 0.17 EUR/kWh, the annual pump operating cost = approximately EUR 453. If there were no PVs, the cost would be 4200 × 0.17 ≈ EUR 714. Savings thanks to PVs ≈ EUR 238–286 per year.

Seasonal Performance Factor (SPF) including PVs:

- Heating SPF: 3.2–3.8.

- Domestic Hot Water SPF: 2.2–2.7.

- Combined All-Year SPF: 3.0–3.5.

- We calculate the total SPF = 3.33.

- Evaluation of cooperation between the heat pump and PV 8.05 kWp is as follows:

- (1)

- The PV system covers 20–35% of the pump’s energy consumption. Under ideal conditions, this can be as much as 40%.

- (2)

- Heating + DHW with SPF ≈ 3.3 means approx. 14,000 kWh of heat from ~4200 kWh of electricity.

- (3)

- PV 8.05 kWp allows the pump to be powered almost entirely in summer (DHW) and partially in winter.

- (4)

- Annual savings with PV are typically around EUR 238–358.

The presented installation (west) would avoid 1891 kg/year of CO2 emissions, which means that, thanks to this solution, we contribute to activities in the area of environmental protection. Based on the available data and the installation cost, it is estimated at approximately EUR 4381 (with the thermal modernisation relief deducted from tax). Given the estimated energy prices, annual consumption, and forecasts of energy production by the proposed installation, the payback period of the investment was determined to be 5 years; however, in reality, the benefits will start to be felt much earlier. The results of the conducted research are confirmed by publications [41].

5. Conclusions

Based on the simulations and analyses presented in this article, the following conclusions were formulated:

1. In the presented research, the payback time of a photovoltaic investment with an already installed air heat pump is approximately 5 years. This is an interesting prospect (especially if both investments are covered by plans to co-finance their purchase and installation). In this case, the profitability of the investment is at a high level, as long as the potential investor has the opportunity to invest approximately 4236 EUR.

2. The installation presented would allow us to avoid 1891 kg/year of CO2 emissions, which means that with this solution, we contribute to environmental protection activities.

3. Investing in such a dual energy system allows you to reduce the costs of heating and electricity. Heating and electricity bills must become more predictable, which allows you to plan your expenses.

4. Even without obtaining a subsidy for the installation of a heat pump with photovoltaics, the analysed combination of these two sources seems beneficial in terms of the economic and ecological benefits achieved. The above-mentioned system allows you to reduce CO2 emissions and the costs associated with maintaining single-family households by several dozen per cent.

5. The proposed design of a photovoltaic installation with an installed air heat pump may cover the annual energy demand.

6. According to researchers, it is best to perform the integration process already at the stage of building a house, which will save costs and accelerate the return on investment; however, in most cases, this process is also possible when there is already one renewable energy system, because in the vast majority of cases, both a heat pump and a photovoltaic system can be installed.

To sum up, the integration of a heat pump with a photovoltaic panel system is a solution that can bring both economic and ecological benefits. The use of such a hybrid system allows you to become independent from variable market prices, which may be an optimal solution from the perspective of expected upward changes in energy price markets. Additionally, the use of such an integrated energy system increases the market value of the property during its possible resale. As for the ecological effect, both systems use renewable energy sources (sun and air/land/water energy), which significantly reduces carbon dioxide emissions and, therefore, the carbon footprint.

Like any study, this one has its limitations. It is important to emphasise that each such project requires an individual approach and there are no identical system solutions that can be implemented in each analysed case. For the integration and implementation process itself, each such investment must include several stages, including an energy audit of the building, analysis of the power selection of the photovoltaic installation, optimisation of panel installation, and assessment of the possibility of technical integration.

Further directions of research in this area should certainly include storage systems (both heat and electricity) based on the Smartgrip idea. Such a connection is a real step towards full energy independence. If the operation were economically justified, such a solution could further increase household self-sufficiency in the context of energy purchases.

To sum up the above, considerations regarding the assessment of the integration of photovoltaic cells with a heat pump do not exhaust the entire topic. There remains an incentive for further research to confirm that photovoltaic panels and a heat pump are currently the two best renewable energy systems cooperating with each other to generate free energy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.N. and W.L.; methodology, M.N.; software, M.N. and W.L.; validation, M.N., A.K. and W.L.; formal analysis, M.N., A.K. and W.L.; investigation, M.N. and W.L.; resources, M.N. and W.L.; data curation, M.N., A.K. and W.L.; writing—original draft preparation, M.N.; writing—review and editing, M.N.; visualisation, M.N.; supervision, M.N.; project administration, A.K., W.L. and M.N.; funding acquisition, A.K., W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lorenzo, C.; Narvarte, L.; Almeida, R.H.; Cristóbal, A.B. Technical evaluation of a stand-alone photovoltaic heat pump system without batteries for cooling applications. Sol. Energy 2020, 206, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliano, A.; Tina, G.M.; Aneli, S. Improvement in Energy Self-Sufficiency in Residential Buildings Using Photovoltaic Thermal Plants, Heat Pumps, and Electrical and Thermal Storage. Energies 2025, 18, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Shi, C.; Liu, Y.; Fu, X.; Ma, T.; Jin, M. Advanced Exergy and Exergoeconomic Analysis of Cascade High-Temperature Heat Pump System for Recovery of Low-Temperature Waste Heat. Energies 2024, 17, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Wang, R. When and how to use cascade high temperature heat pump—Its multi-criteria evaluation. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 309, 118435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Gracia, A.; Uche, J.; del Amo, A.; Bayod-Rújula, Á.A.; Usón, S.; Arauzo, I. Energy and environmental benefits of an integrated solar photovoltaic and thermal hybrid, seasonal storage and heat pump system for social housing. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 213, 118662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kezier, D.; Cheng, J.H.; Li, X.Y.; Cao, X.; Zhang, C.L. A semi-cascade heat pump system for different temperature lifts. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 236, 121767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niekurzak, M.; Kubińska-Jabcoń, E. Analysis of the Return on Investment in Solar Collectors on the Example of a Household: The Case of Poland. Front. Energy Res. 2021, 9, 660140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, D.; Zhang, G.; Peng, X.; Qin, X.; Wang, G. 4E analyses of a novel solar-assisted vapour injection autocascade high-temperature heat pump based on genetic algorithm. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 299, 117863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerstwo Klimatu i Środowiska—Portal Gov.pl. Polityka Energetyczna Polski do 2030 Roku. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/klimat/polityka-energetyczna-polski-do-2030-roku (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Cevik, S.; Zhao, Y. Shocked: Electricity Price Volatility Spillovers in Europe; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sarfarazi, S.; Deissenroth-Uhrig, M.; Bertsch, V. Aggregation of Households in Community Energy Systems: An Analysis from Actors’ and Market Perspectives. Energies 2020, 13, 5154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, A.; Pecnik, R.; Peeters, J.W. Thermodynamic analysis and heat exchanger calculations of transcritical high-temperature heat pumps. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 303, 118172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitsos, V.; Vontzos, G.; Paraschoudis, P.; Tsampasis, E.; Bargiotas, D.; Tsoukalas, L.H. The State of the Art Electricity Load and Price Forecasting for the Modern Wholesale Electricity Market. Energies 2024, 17, 5797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, C.; Narvarte, L.; Cristóbal, A.B. A Comparative Economic Feasibility Study of Photovoltaic Heat Pump Systems for Industrial Space Heating and Cooling. Energies 2020, 13, 4114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udroiu, C.M.; Navarro-Esbrí, J.; Giménez-Prades, P.; Mota-Babiloni, A. Towards sustainable process heating at 250 °C: Modelling and optimisation of an R1336mzz (Z) transcritical High-Temperature heat pump. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 242, 122521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, H.u.; Hirvonen, J.; Jokisalo, J.; Kosonen, R.; Sirén, K. EU Emission Targets of 2050: Costs and CO2 Emissions Comparison of Three Different Solar and Heat Pump-Based Community-Level District Heating Systems in Nordic Conditions. Energies 2020, 13, 4167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.; Zhang, X.; Gao, J.; Wang, R.; Xu, Z. Entransy-based heat exchange irreversibility analysis for a hybrid absorption-compression heat pump cycle. Energy 2024, 289, 129990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niekurzak, M. The Potential of Using Renewable Energy Sources in Poland, Taking into Account the Economic and Ecological Conditions. Energies 2021, 14, 7525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawley, J.; Martin-Vilaseca, A.; Wingfield, J.; Gill, Z.; Shipworth, M.; Elwell, C. Demand response with heat pumps: Practical implementation of three different control options. Build. Serv. Eng. Res. Technol. 2023, 44, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettinari, M.; Frate, G.F.; Tran, A.P.; Oehler, J.; Stathopoulos, P.; Kyprianidis, K.; Ferrari, L. Impact of the Regulation Strategy on the Transient Behaviour of a Brayton Heat Pump. Energies 2024, 17, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayibo, K.S.; Pearce, J.M. A review of the value of solar methodology with a case study of the US VOS. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 137, 110599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.A.; Dunlop, E.D.; Hohl-Ebinger, J.; Yoshita, M.; Kopidakis, N.; Hao, X. Solar cell efficiency tables (version 56). Prog. Photovolt. 2020, 28, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Wang, C.; Liu, J.; Zhuang, Y.; Du, J. Design and 4E analysis of heat pump-assisted extractive distillation processes with preconcentration for recovering ethyl-acetate and ethanol from wastewater. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2024, 201, 510–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziras, C.; Calearo, L.; Marinelli, M. The effect of net metering methods on prosumer energy settlements. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2021, 27, 100519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldyryev, S.; Ilchenko, M.; Krajačić, G. Improving the Economic Efficiency of Heat Pump Integration into Distillation Columns of Process Plants Applying Different Pressures of Evaporators and Condensers. Energies 2024, 17, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatellos, G.; Zogou, O.; Stamatelos, A. Energy Performance Optimisation of a House with Grid-Connected Rooftop PV Installation and Air Source Heat Pump. Energies 2021, 14, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.K.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, H.; Dong, Y.; Jamil, S.R.; Adnan, M. Performance analysis of a novel combined open absorption heat pump and FlashME seawater desalination system for flue gas heat and water recovery. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 301, 117996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróblewski, P.; Niekurzak, M. Assessment of the possibility of using various types of renewable energy source installations in single-family buildings as part of saving final energy consumption in Polish conditions. Energies 2022, 15, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klute, S.; Budt, M.; van Beek, M.; Doetsch, C. Steam generating heat pumps–Overview, classification, economics, and basic modelling principles. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 299, 117882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somakumar, R.; Kasinathan, P.; Monicka, G.; Rajagopalan, A.; Ramachandaramurthy, V.; Subramaniam, U. Optimisation of emission cost and economic analysis for microgrid by considering a metaheuristic algorithm-assisted dispatch model. Int. J. Numer. Model. Electron. Netw. Devices Fields 2022, 35, e2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomasson, T.; Raitila, J.; Tsupari, E. Experimental and techno-economic analysis of solar-assisted heat pump drying of biomass. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheswaran, G.; Ravi, R.; Maheswar, R.; Shanmugasundaram, K.; Padmanathan, K.; Subramaniyan, U.; Alavandar, S.; Ganesh, R.; Manikandan, V. Conceptual context of tilted wick type solar stills: A productivity study on augmentation of parameters. Sol. Energy 2021, 221, 348–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcicki, R. Solar Photovoltaic Self-consumption in the Polish Prosumer Sector. Rynek Energii 2020, 1, 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Gong, H.; Cheng, C.; Qie, Z. Experimental evaluation of metal–organic framework desiccant wheel combined with heat pump. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 236, 121542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.M.; Sommerfeldt, N. Economics of Grid-Tied Solar Photovoltaic Systems Coupled to Heat Pumps: The Case of Northern Climates of the U.S. and Canada. Energies 2021, 14, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spale, J.; Hoess, A.J.; Bell, I.H.; Ziviani, D. Exploratory Study on Low-GWP Working Fluid Mixtures for Industrial High Temperature Heat Pump with 200 °C Supply Temperature. Energy 2024, 308, 132677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Yin, H.; Li, B.; Zhang, H.; Jurasz, J.; Zhong, L. Heating performance and spatial analysis of seawater-source heat pump with staggered tube-bundle heat exchanger. Appl. Energy 2022, 305, 117690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinnia, S.M.; Amiri, L.; Nesreddine, H.; Monney, D.; Poncet, S. Thermodynamic analysis of high temperature cascade heat pump with R718 (high stage) and six different low-GWP refrigerants (low stage). Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 53, 103812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymiczek, J.; Szczotka, K.; Michalak, P. Simulation of Heat Pump with Heat Storage and PV System—Increase in Self-Consumption in a Polish Household. Energies 2025, 18, 2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politykin, M.; Yatsenko, O. Integration of a solar power plant and a heat pump into a hot water supply system based on a digital twin. Technol. Eng. 2025, 26, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Li, Z.; Gou, Y.; Guo, G.; An, Y.; Fu, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhong, X. Modelling and Simulation Analysis of Photovoltaic Photothermal Modules in Solar Heat Pump Systems. Energies 2024, 17, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).