Abstract

The main objective of this article is to model, simulate, and analyze the interaction of energy storage systems with BIPV installations. Currently, due to the instability of energy generation, the economic challenges of integrating PV installations into the electricity grid, and the desire to increase self-consumption, energy storage facilities are becoming increasingly popular. Subsidy programs most often favor PV installations, including BIPV, that work with energy storage devices. Therefore, there is a justified need to model energy storage devices for use with BIPV. The article describes the rationale for the benefits of using energy storage systems within current billing models, using Poland as an example. The introduction also provides an overview of the most popular energy storage technologies compatible with renewable energy installations. To achieve these objectives, appropriate system solutions were designed in the MATLAB environment and used to perform simulations, taking into account variable energy demand. An economic analysis of the system’s operation was conducted using a prosumer net-billing model, and adjustments were made to the system configuration. It has been shown that the use of appropriate energy storage solutions, cooperating with photovoltaic installations, allows for increased self-consumption and more efficient management of electricity obtained in BIPV, which has a positive impact on the payback time and economic profits. The analysis method used and the results obtained are true for the assumed known load profile; however, the method can be successfully applied to various load profiles.

1. Introduction

The increasing number of micro-installations, primarily photovoltaic, operating in BIPV systems, means that the traditional grid, based on centralized energy production, must adapt to new operating conditions—particularly the instability and variability of renewable energy generation [1,2,3].

In this situation, energy storage devices are becoming a key element of the energy transition, enabling the storage of surplus energy, increasing self-consumption, and reducing the load on the power grid.

The issue of cooperation between energy storage and PV installations, especially BIPV, is increasingly being addressed worldwide. Several representative works from recent years have been selected to summarize the dominant directions of research in this area.

In [4], a review of typical configuration and operation solutions of BIPV installations was presented. It focuses on the products and technologies used to integrate PV panels directly into buildings, describing 35 existing BIPV test systems monitored under real conditions. Their performance, efficiency, and payback times are analyzed. The authors consider the potential for predictive maintenance, which can increase BIPV reliability and extend the system’s lifespan. The authors do not address the use of energy storage devices in this paper.

In their article [5], the authors note that BIPV systems can gain energy flexibility through integration with energy storage (batteries), especially in the context of distributed renewable applications. The key challenge they analyze is optimally controlling the energy flow (on an hourly basis) among PV panels, the battery, and the power grid, accounting for the building’s load profile. In line with this challenge, the authors addressed the strategic selection of energy storage capacity and therefore proposed a nonlinear optimization model with multiple constraints that describes the power flows between PV panels, the battery, and the grid throughout the day. The proposed strategy can be used by designers to determine how to manage energy throughout the day (when to charge the battery, when to sell excess energy to the grid), depending on local energy costs and loads. This model does not account for weather changes, assuming a clear day, and the analysis covers a single 24 h period.

The authors of one of the most recent review articles from 2025 [6] focus on the integration of photovoltaic systems with energy storage systems in the context of buildings. They describe system configurations and mathematical models used to simulate and forecast the operation of these systems. They also analyze operational strategies that improve economic efficiency. ESS models include modeling of the battery state of charge (SoC) as well as models of battery degradation over time. Various storage technologies are considered: not only electric batteries but also other forms (e.g., thermal storage, in some cases hydrogen storage), thus providing a broad perspective on possible ESS applications in buildings. This article serves as a guide for designers of PV systems cooperating with energy storage in buildings, indicating which models and strategies may be most effective depending on the assumed conditions (economy, building load, available technology).

In the article [7], the author analyzes the economic profitability of integrating an energy storage system (battery) with a BIPV system in a residential building. The article makes simplifying assumptions, such as predictable and unchanging random loads, constant battery performance, and a selected geographic region (Italy). For designers of BIPV systems with energy storage, the article provides a decision-making tool that helps select the battery size based on market costs, allowing for more economically viable storage integration.

In the article [8], 11 different BESS (Battery Energy Storage System) models using the machine learning (ML) method were presented and it was pointed out that due to the increasing integration of renewable sources (especially PV) in energy systems, it is necessary to implement distributed energy storage systems (BESS) that will help in system stabilization, energy management and power control.

As can be seen, in recent years, topics related to BIPV and ESS have been discussed in various contexts and areas, but apart from review articles, there is a lack of works that combine different aspects.

Considering the range of topics covered in previous research papers and the conclusions drawn from them, the authors propose a case study of a selected energy storage system operating in conjunction with a BIPV system in Poland. This approach provides a more realistic and comprehensive approach to BIPV + ESS modeling, combining variable load, MATLAB simulations (MATLAB 24.11 (R2024a) environment), economic analysis in a specific energy market (Poland), and the impact of self-consumption on investment return. Compared to previous work, this is a step beyond simple optimization models or general overviews.

The role of energy storage devices in conjunction with BIPV is described below, along with the principles of charging the selected type of energy storage device. Based on the analysis, lithium–iron–phosphate (LFP) technology was selected for modeling and simulation, and its properties and characteristics are also described.

In the remainder of this article, data regarding PV generation and the energy demand of the facility in an exemplary BIPV system are modeled. A simulation of the storage device’s operation, degradation over time, and its impact on self-consumption is developed. On this basis, an economic analysis of the project was performed, taking into account, among others, investment costs and the NPV profitability index.

1.1. The Role of Energy Storage in Power Systems

Energy storage systems enable effective management of the energy system, acting as a reserve power source and mitigating voltage problems in distribution networks. They contribute to improving energy quality parameters, such as voltage and frequency stability. They also reduce the need for grid infrastructure expansion through local energy storage and distribution, for example, in BIPV installations, which provides an alternative to costly investments in power grid development.

The use of energy storage systems increases the energy efficiency of the system by supporting demand management and optimizing energy consumption. Depending on the rules of the given energy trading market, it is also possible to conduct price arbitrage, involving the purchase of energy during periods of low prices and the sale during periods of price increases. Energy storage systems also support the development of energy communities, energy clusters, and prosumers, enabling increased self-consumption of energy and reducing load on the power grid.

Thanks to integration with electromobility, energy storage facilities enable charging of electric vehicles while reducing peak grid loads. Their role is particularly important in the context of achieving climate goals, as they support decarbonization and the implementation of sustainable and low-emission solutions. The adoption of energy storage facilities as full participants in the energy market enables their commercial use in the provision of system services, which supports the further development of this sector [9,10,11,12].

1.2. Issues Related to the Design of Energy Storage Facilities

Designing an individual energy storage system requires a holistic approach to the details and conditions of the planned installation. The goal is to maximize operational benefits. These benefits include the following: maximizing the utilization of the energy produced by the PV system, increasing self-consumption, reducing energy purchases from the Distribution System Operator (DSO), providing emergency power in the event of a grid outage, and islanding (always include the switch-on delay time, which varies depending on the selected technology). This is important to keep in mind when configuring sensitive devices, such as those used in hospitals.)

The selection of a given technology should be supported by a prior analysis of the properties of the configuration in which the storage system will be located [13,14,15]. This analysis can be considered using the technical parameters listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Electric energy storage parameters [16].

The demand for energy storage solutions is very high and constantly growing. Industry is rapidly capitalizing on the economic potential of renewable energy, and the market has become widespread for home users. All of this is driving an increase in the number of inquiries from the scientific community, and the list of problems in fields related to renewable energy is expanding. Current challenges facing scientists include the following [16]:

- Insufficiently regulated SEI—the interfacial layer between the electrodes and the electrolyte liquid, which, if sealed (which is a challenge), prevents direct contact between the anode, cathode, and electrolyte.

- Explosion hazard—caused by a spontaneous, self-propelled series of uncontrolled changes that provoke heat generation and ultimately explosion. This phenomenon is known as thermal runaway.

- Battery toxicity related to the internal composition of the electrolytes used in LiPo batteries.

- Recycling, due to the growing demand for batteries in electric mobility and energy storage systems, where 5% of components/devices are recycled.

- Degradation of battery capacity over time, resulting from changes in the electrolyte’s chemical structure.

- Technology is providing an increasing number of possibilities that can provide a platform for solving the above problems. These include [16]:

- use of a nanometric cathode;

- reducing the cathode size through the use of nanostructured material in lithium-ion batteries;

- modifying electrolytes to achieve the following characteristics: non-flammability, non-toxicity, low vapor pressure, thermal stability, resistance to temperature changes;

- refining ionic liquid technology;

- anode modification;

- using a BMS (Battery Management System), which allows for the observation and analysis of changes in important battery parameters.

1.3. Comparison of Parameters of Selected Lithium-Ion Technologies

Among lithium-ion batteries, the most popular solutions are considered to be LTO, LFP, and NMC. All three technologies differ in their physical properties and industry applications [17,18].

The values of the parameters presented in Table 2 influence the extent to which the above technologies are applied, as does the summary of advantages and disadvantages in Table 3.

Table 2.

Summary of individual technology parameters: LTO, NMC, LFP [17,18].

Table 3.

Summary of advantages and disadvantages of NMC, LFP, and LTO [19].

1.4. Charging Lithium-Ion Batteries

Lithium-ion batteries utilize the phenomenon of lithium-ion extraction. This process involves the introduction of lithium ions into the electrodes during charging (or discharging). The two electrodes are separated by a foil (SOE) to prevent electrical contact, and all components are immersed in a liquid electrolyte containing charged lithium particles. It is worth noting that some solutions use a solid electrolyte, the purpose of which (in this case) is not only electrical conductivity but also separation between the electrodes. These batteries are called lithium-ion polymer batteries. Regardless of the electrolyte production technology used, lithium ions move between the electrodes; hence, these batteries are generally classified as lithium-ion batteries [18,19].

The process of lithium-ion movement during charging/discharging is correlated with the oxidation reaction of the electrodes, supported by electron flow via an external circuit. The diagram in Figure 1 shows the battery charging process in which positively charged lithium ions are transferred (caused by a potential difference) from the positive electrode (cathode) to the negative electrode (anode) [18,19].

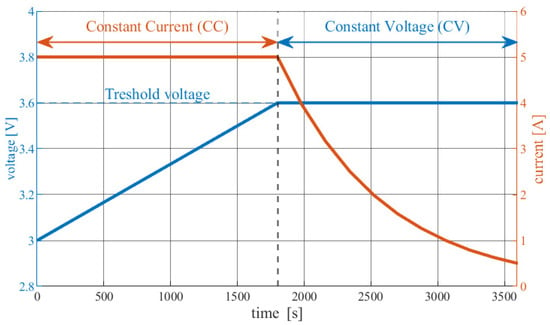

Figure 1.

Graphical interpretation of the CC-CV loading algorithm [20].

1.5. CC/CV (Constant Current/Constant Voltage) Charging Algorithm

This solution is widely used (proven, well-developed) as a method for charging lithium-ion batteries, thanks to its relatively easy implementation and the lack of the need for microcontrollers.

This process is essentially two-phase. The first phase, called constant current, involves charging the device with a constant current (DC), which increases the battery voltage. Once the highest voltage is reached, the next phase, called constant voltage, begins. This involves the charger forcing the charging process to continue at a fixed voltage. The current decreases exponentially during this phase. The process ends when the current reaches a pre-defined (low) value. The graph in Figure 1 illustrates the algorithm described above [20].

In real-world conditions, for operational safety reasons, the CC-CV algorithm must be divided into several conditional processes. Table 4 describes the CC-CV algorithm in real-world conditions.

Table 4.

CC-CV loading algorithm [20].

1.6. LiFePo4 Cell Structure

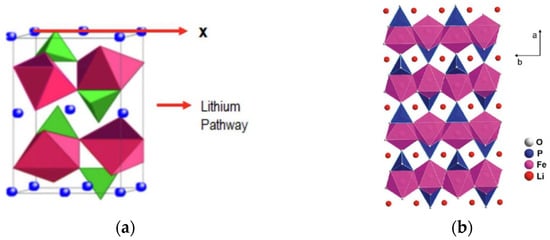

The negative electrode (Figure 2a) used in this technology is made of graphite, which readily absorbs and releases lithium ions. The positive electrode is typically made of LiNiO2, LiMn2O4, LiCoO2, or LiFePO4 (LFP). LFP is a popular solution due to its abundant availability, low toxicity, and stability. LFPhas an olivine crystal structure containing iron, lithium, and phosphorus atoms. Oxygen is the linker that creates an ordered crystal lattice. The advantage of this solution is the strong oxygen-phosphorus bond, which prevents oxidation at high temperatures, effectively enhancing the battery’s stability.

Figure 2.

LFP batteries: (a) internal structure of the cathode material; (b) olivine structure [21].

The internal system in LFP batteries (Figure 2b) allows lithium to be transported through one type of channel, thereby limiting the rate of reactions. The electrolyte is a mixture of organic solvents and lithium salts. This design limits the decrease in electrical conductivity with temperature increases above the nominal value. The separator between the electrodes is usually a polyethylene or polypropylene foil [21].

1.7. Organization of the Paper

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the mathematical and simulation models used in the study. In Section 2.1, a model for estimating the power generated by a rooftop photovoltaic (PV) installation is introduced. For this purpose, the authors used commercial software Helioscope (Folsom Labs: San Mateo, CA, USA, available online: https://www.helioscope.com). Next, Section 2.2 focuses on modeling the electrical load profile of the analyzed facility, including assumptions regarding consumption patterns and temporal variations in energy demand.

In Section 2.3, a model of the energy storage system is described, with particular emphasis on battery characteristics, operational constraints, and aging effects. Building on this, Section 2.4 introduces the control algorithm responsible for managing the charging and discharging processes of the energy storage system. The algorithm aims to optimize system operation with respect to energy efficiency and economic performance.

Section 2.5 is devoted to the economic model, which defines the costs and benefits associated with the deployment of the energy storage system. This includes investment costs, operational expenses, energy savings, and potential revenues from surplus energy.

Section 3 presents a case study of a facility located in Poland, outlining the assumed design parameters for the building, the photovoltaic installation, and the energy storage system. Subsequently, Section 4 discusses the simulation results, including system performance indicators, energy flows, and economic outcomes. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the main findings of the study and highlights conclusions.

2. Materials and Methods

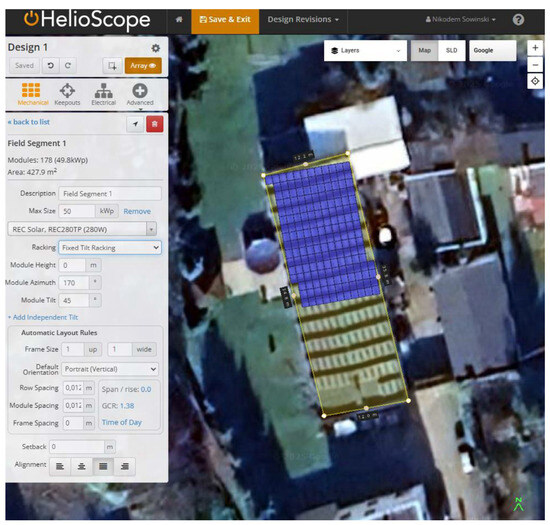

2.1. Data Generation from BIPV Installations

To generate data defining energy generation from the PV installation, the Helioscope software was used (Figure 3). This tool utilizes publicly available weather databases containing key information necessary for the proper design of a PV generator, including irradiance under several conditions (clear sky, fully overcast, albedo), wind speed, and temperature. Based on implemented models simulating energy generation, it creates predictions.

Figure 3.

Helioscope program interface when designing an installation.

2.2. Simulation of the Facility’s Energy Demand

To simulate the operation of an energy storage system, it is necessary to provide data on the electricity demand for the facility where the battery is to operate. To do this, a list of basic devices located in the facility must be defined. Based on this, it is possible to determine the total effective power of devices operating during operating hours Pdevs, according to the following formula:

where —rated power of the i-th device, —simultaneity factor of the i-th device, —number of devices installed in the factory.

The generation of the correct demand profile takes into account both the energy consumed during production processes and the energy resulting from the plant’s own needs. To ensure the profile is realistic and reflects the natural variability occurring in real-world technological processes, a random fluctuation of ±15% is introduced into the effective power. Outside of business hours and on weekends, the algorithm only considers minimal energy consumption associated with the operation of systems necessary to maintain facility operations.

The active power consumed in the plant at the h-th hour is presented by the relationship [22,23]:

where —power resulting from the plant’s own needs during working hours, —power corresponding to the plant’s own needs outside working hours, —random variable with a uniform distribution over the interval from a to b.

2.3. Energy Storage Model

The model of the developed energy storage device is based on a quasi-static electrical description, in which the nonlinear electromotive force , which depends on the current state of charge (SoC), and the internal resistance , whose values change with temperature, play a key role. The energy storage device consists of a set of . Each module has both the total system capacity expressed in ampere-hours and the maximum charging and discharging power . The total capacity of the entire storage device is therefore equal to the following:

where Ctotal—total energy storage capacity [Ah], nmodules—number cell modules.

A full dynamic battery model typically uses additional RC segments to represent dynamic phenomena. However, their time constants are primarily important for modeling short-term electrical responses, typically ranging from seconds to several minutes. Because the analyses were conducted with a time step of one hour over a period of many years, the impact of these rapid dynamics is averaged out, and including additional RC branches does not significantly improve accuracy.

The storage status update procedure is as follows. If the system is discharged at hour with constant power for time , then first the discharge current is determined based on the current battery voltage [24]:

where voltage at the battery terminals [V].

Solving the relationship (4) allows us to determine the current drawn from the storage and, consequently, the charge [25]:

Since the capacity of the entire storage is directly related to the number of base modules and their nominal capacity, the new state of charge is calculated by relating the transferred charge to this capacity [26]:

Updating the SoC then allows us to determine the new open circuit voltage , and thus obtain the updated battery voltage [27]:

This model enables a reliable representation of the energy storage system’s operation at hourly intervals, ensuring an appropriate compromise between computational complexity and the accuracy of representing the processes occurring within the battery.

The study also takes into account the battery aging process, i.e., changes in its State of Health (SoH) over the operating lifetime of the system. For this purpose, after each simulation step, the SoH value is determined according to equation [28]:

where —the number of full charge and discharge cycles of the storage, updated after each hour of simulation, storage life given in full charge cycles, —battery end-of-life threshold.

2.4. Energy Storage Control Algorithm

Energy storage is controlled based on the current power balance between photovoltaic generation , consumer demand , and the storage’s charging/discharging capabilities. Initially, the power balance of the entire system is determined at the -th hour:

where PPV—power generated by the PV installation [W], Pd—power required by the mechanical workshop [W].

If there is excess power in the installation (, it is first directed to the storage limited by the maximum charging power and the maximum permissible state of charge [29]:

The remaining part of the surplus, if any, is fed into the grid as power :

If there is a power shortage in the installation (, the algorithm first uses the energy stored in the storage, with the limitation resulting from the maximum discharge power and the minimum permissible charge level [29]:

If, however, a shortage remains, the missing power is taken from the grid according to the relation (9). In this case, the power sent to the grid is negative.

2.5. Economic Analysis of a Prosumer Installation in Poland

Current Polish regulations prevent price arbitrage by prosumers. Legislators intend for prosumers to be consumers-producers for their own needs, not “speculators” in the energy market. The key provision here is Article 3, Section 13a of the Energy Law [30], which excludes energy purchased for storage from the category of the end user’s “own use.” This means that as soon as a prosumer begins purchasing energy with the intention of reselling it, they cease to act as an end user for their own needs, thus losing their privileged status (exemption from many obligations) and assuming the role of an energy entrepreneur. To legally conduct such a practice, all the requirements for an energy trading company must be met. In practice, for prosumers, this means establishing a business, obtaining a license (at least for energy trading), completing registration of an energy storage facility, and, if necessary and depending on the installation’s capacity, entering the MIOZE (Register of Small-Scale Energy Producers). Only after meeting these conditions could one legally purchase energy from the grid, for example, at a cheaper tariff and resell it at a more expensive one. However, in such a case, the user of the installation is no longer strictly a prosumer, but rather an energy company. The legislator’s intention was to clearly distinguish between prosumer activity and professional energy trading. Prosumers are expected to use energy storage primarily to increase their own green energy self-consumption (e.g., by using what was produced during the day at night), or to postpone the moment of feeding surplus energy into the grid to a more cost-effective point (which is permitted if it concerns their own renewable energy). However, profiting from typical arbitrage (buy low, sell high) is reserved for entities with appropriate authorizations and licenses. Current regulations effectively block the possibility of price arbitrage by prosumers, provided they operate within their standard status as end users.

In summary, the average owner of a prosumer PV installation cannot legally charge their home storage with cheap electricity from the grid and sell it for profit at high prices. Such activity is considered illegal energy trading by the end user. Only after meeting strict conditions (company registration, obtaining a license, registering entries, etc.) can price arbitrage be conducted legally, which, in practice, makes it beyond the reach and interest of the typical prosumer. Regulations require prosumers to remain consumers, not full-fledged traders in the energy market, thus protecting the market from uncontrolled energy trading that bypasses licensed companies [30,31,32,33].

Based on the above analysis, the following assumption was made: The analyzed installation is entirely focused on self-consumption and reducing costs associated with energy shortages and surpluses from the PV installation.

To simulate the savings of an energy storage system operating in self-consumption mode and minimizing energy drawn from the grid, the data summarized in Table 5 was implemented. Table 6 characterizes the input parameters used in the economic model.

Table 5.

Approximate values of market electricity prices, based on the TGEBase 24 index of the Polish Power Exchange.

Table 6.

Summary of input parameters used in the economic analysis.

The data in Table 5 are average values of the TGEBase 24 indexes. It was assumed that the most important factor is data consistency (within the same year, here: 2024) and the shortest time horizon from the potential implementation year (2025). The average monthly value was selected due to the implementation of the fixed-month billing method in the model, in which 20% of the energy fed into the grid can be collected from the prosumer deposit and, as a result, reduce the cost of purchasing electricity [33] (the simulator does not implement this billing formula because the storage system normally reduces the PV surplus) [34,35].

The economic model analyzes savings as follows [36]:

where Esup—energy supplementing generation deficiencies from PV installations [Wh].

The Energy Storage System Cost (ESScost) depends on the cell price (Co), multiplied by the number of cells in the modules, and finally, this amount is increased by 30%, which corresponds to the forecasted cost of cabling and balancer [37]:

3. Case Study

3.1. Parameters of the Analyzed Object

To ensure consistent and realistic conditions for the simulation, several operational assumptions were defined for the analyzed facility:

- Work in the mechanical workshop takes place from 8:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. on each business day (Monday–Friday);

- The building is equipped with a heating system that does not rely on electricity (i.e., no electric heaters are used);

- The year 2024 is used as the reference year for operating the storage system. Due to the way data are processed in the Helioscope software, the simulation repeats after 365 days, effectively extending 2024 as the test year and reproducing the same work schedule and electricity demand patterns;

- Electricity demand is calculated as the sum of the installed power of the devices located in the facility, adjusted by the simultaneity factor (Table 7);

Table 7. Devices located in the analyzed mechanical workshop.

Table 7. Devices located in the analyzed mechanical workshop. - A total of 250 working days per year is assumed.

Additionally, a constant, unchanging power demand of 7 kW (covering everyday appliances and lighting) was added between 8 a.m. and 4 p.m., and 5 kW (lighting and monitoring) during the remaining hours.

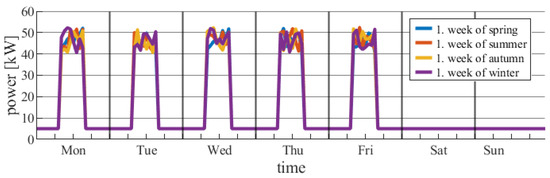

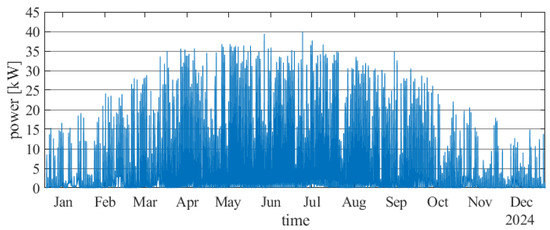

Figure 4 shows the power demand profile of the analyzed plant during the first week of each of the four seasons in 2024. These profiles reflect characteristic changes in demand resulting from seasonal variations in operating conditions and the facility’s typical operating schedule. This allows for comparison of plant load dynamics across different periods of the year and identification of potential differences relevant to the design and selection of energy storage.

Figure 4.

Power demand for the first week of all four seasons of 2024.

3.2. PV Installation Parameters

To obtain detailed data regarding the planned installation, the following data was submitted:

- Installation place: city of Gniezno in Poland (Greater Poland);

- Coordinates: and [WGS 84 (EPSG 4326)];

- Expected installation power: 49.8 kWp;

- PV module model selection: REC 280TP (280 Wp) [38];

- Azimuth angle: 170°;

- Module angle relative to the Sun: 45°.

After implementing the expected data listed above, it is possible to download the projected operational data for the PV installation in a CSV file from Helioscope software. Table 8 and Figure 5 contain some of the data obtained.

Table 8.

Selected data for 1 January 2024 obtained in the Helioscope program.

Figure 5.

Power generation by a photovoltaic installation at the DC side obtained from the Helioscope environment.

3.3. Energy Storage System Parameters

In order to apply the energy storage model discussed in Section 2.5, it was necessary to define a set of parameters describing the analyzed battery. The battery meets the design constraints related to the assumed maximum storage volume and weight. In this work, the storage system was assumed to utilize LFP battery technology, characterized by high cyclic durability and operational stability. For further calculations and simulations, the parameter values listed in Table 9 were adopted, covering key characteristics necessary to correctly represent the storage system’s behavior under the operating conditions of the tested facility.

Table 9.

GC LFP (LiFePO4) green cell parameters [39].

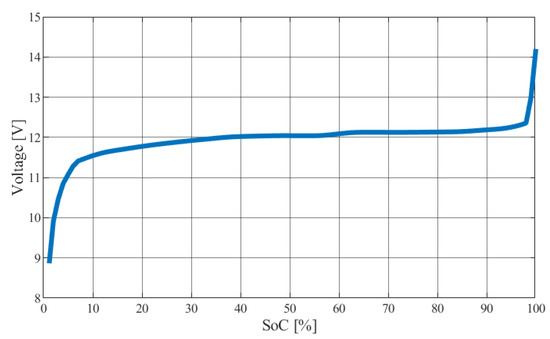

Figure 6 shows the voltage characteristics as a function of the state of charge (SoC), obtained from the catalog data of the adopted battery pack. This curve reflects the nonlinear relationship between open-circuit voltage and charge level typical of LFP technology.

Figure 6.

Characteristics of cell discharge with 1 C current.

The program operates based on several key assumptions. The model directly uses previously defined single-cell parameters (Table 9, Figure 6); any modification to these parameters would result in incorrect simulation performance. The discharge curve was implemented based on catalog data. To assess the impact of temperature on storage operation, the year was divided into two periods relative to the nominal temperature of 25 °C: the summer period (January–June), during which the cell temperature is 30 °C, and the winter period (July–December), during which the cell temperature is 23 °C.

The energy storage operates solely to increase self-consumption. Depth of discharge (DoD) is limited to 85%, in accordance with catalog recommendations, while the battery’s state of health (SoH) decreases linearly with the number of cycles completed. At each simulation step, the difference between the energy produced by the photovoltaic system and the plant’s demand is calculated. A positive value indicates excess energy that can be stored, while a negative value indicates the need to draw energy from the storage.

4. Results and Discussion—Simulation and Analysis

4.1. Selection of the Target Configuration of Energy Storage

Using the models presented in Section 2, simulations of system operation were conducted for various battery pack sizes to analyze the impact of storage capacity on the facility’s energy balance. For each variant, detailed storage operation profiles and the degree of utilization of locally generated energy were calculated. In the next step, an economic analysis was performed, taking into account both investment costs and the potential benefits resulting from increased energy self-consumption. A summary of the costs and benefits achieved for the individual energy storage system configurations is presented in Table 10.

Table 10.

Simulated operating costs of an energy storage system depending on the storage size.

The net present value (NPV) was additionally calculated for each case. The value of this economic indicator expresses: the profit from updated net revenues after deducting the initial costs incurred and the increase in investor wealth resulting from the investment, taking into account the time value of money. The investment is acceptable if NPV ≥ 0 [34,40].

where Ct—savings in year t [PLN], r—discount rate [-], t—year number, n—number of years of analysis, C0—initial investment cost [PLN].

The NPV index was calculated for the data presented in Table 11 for the time n = 10 years. Due to the property of this method, which is the subjective selection of the discount rate, the calculations were performed for r ∊ <5%, 10%>, and the calculation results are presented in Table 12. In practice, however, for investments in the renewable energy sector, the value of the discount rate in Poland oscillates around 7% [35].

Table 11.

NPVs depending on the installation capacity and discount rate.

Table 12.

Cost estimate for a 6.4 kWh energy storage.

The analyses indicate that the most economically effective solution is an energy storage system consisting of four battery packs (). This configuration provides an optimal compromise between investment costs and the benefits of increased energy self-consumption, achieving the highest net present value (NPV) of the considered options. Table 12 presents the cost estimate for the 6.4 kWh energy storage solution.

The difference between the predicted cost and the actual cost obtained in the cost estimate results from the model assumption that the remaining costs constitute 30% of the total price of all cells (Formula (14)).

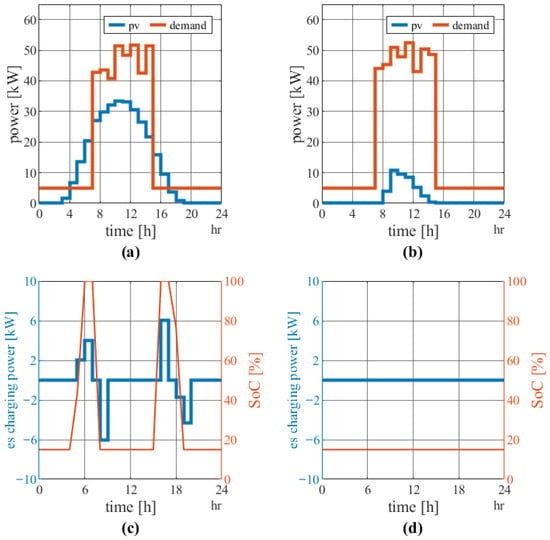

4.2. Simulation Results for 6.4 kW Energy Storage

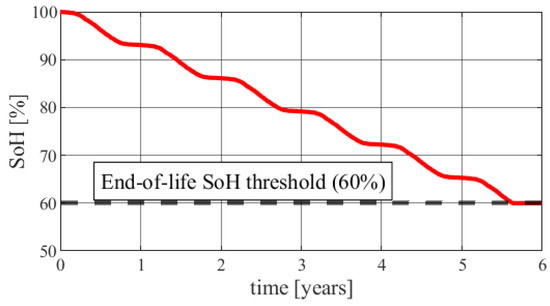

Figure 7 shows the course of the storage’s charging power, the photovoltaic system’s generation, and the load demand for a 6.4 kWh storage system. Analysis of these profiles allows assessment of the dynamics of energy flows in the system and the degree of utilization of the stored energy under various operating conditions. Figure 8, on the other hand, presents the degradation of the battery packs over the entire life of the system, determined based on Formula (8), which allows assessment of changes in the storage’s state of health (SoH) in the long term.

Figure 7.

Single-day simulation (6.4 kWh). (a) PV generation and the demanded power on the first day of summer. (b) PV generation and demanded power on the first day of winter. (c) Energy storage charging schedule and SoC for the first day of summer. (d) Energy storage charging schedule and SoC for the first day of winter.

Figure 8.

Storage degradation simulation (6.4 kWh).

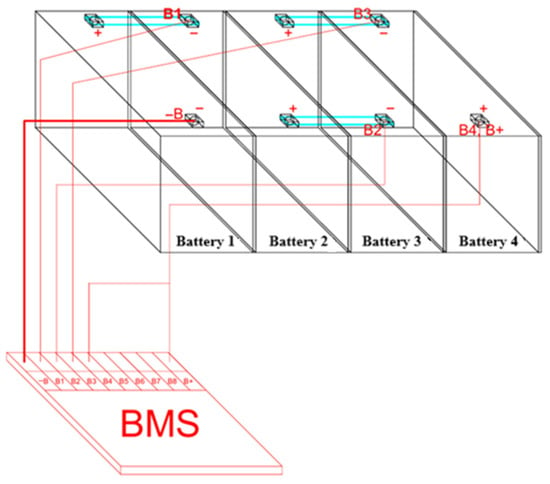

4.3. Example Diagram of an Energy Storage Installation for Cooperation with BIPV

A wiring diagram was created for a 6.4 kWh storage system consisting of four Green Cell CAV13 LiFePO4 GC LiFePO4 batteries [38], with a total energy of 1.6 kWh, connected in series with a 35 mm2 PVC-insulated copper wire, coupled to a JK-B1A8S20P balancer [41].

The Green Cell CAV13 batteries [39] are equipped with individually integrated battery management systems (BMS) that maintain the same voltage level on each cell (3.2 V × 4). However, to ensure uniform voltage across all batteries, the JK-B1A8S20P system was used. This device is intuitive to use, includes all necessary components for installation, and has a user-friendly mobile application that allows for setting parameters such as Sustained Discharge Current, Shutdown Voltage, and Remote Battery Disconnect [41].

A diagram of the proposed system is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Storage installation connection diagram.

5. Conclusions

The authors intended to implement a design for an electricity storage system integrated with a photovoltaic installation based on simulation models. Analyses were conducted at a real-world site with an existing PV installation, and the data regarding energy generation and consumption profiles were prepared to accurately represent local conditions. Thanks to this, results were obtained that can be treated as representative for the case under consideration and used in a possible real implementation.

The simulations were performed in the MATLAB environment, which, due to its extensive range of analytical, visualization, and computational capabilities, proved to be an effective tool for modeling. Using the MATLAB environment enabled the creation of custom algorithms and the testing of various energy storage system configurations (changes to the input parameter, i.e., capacity). The simulations demonstrate that using such models not only allows for the adaptation of the system’s technical parameters to the actual needs of a BIPV system but also provides significant added value during the economic and functional verification phase of the project.

The designed system is based on comparing the PV generation profile with the energy demand profile (at hourly resolution), for example, of a facility equipped with BIPV. Generation data was obtained from Helioscope software, which relies on meteorological data (data for 2024) and installation parameters, while demand was modeled based on the operation of a real mechanical workshop. This includes, among other things, the power and operating time of individual devices, variability in consumption throughout the day, and basic nighttime consumption. This database enabled the creation of a dynamic model that allows analysis of the energy balance at any time of the year.

The energy storage portion of the model implements algorithms to manage battery charging and discharging, while simultaneously monitoring their state of charge (SoC), state of health (SoH), and limitations resulting from depth of discharge and temperature. The selected Green Cell lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO4) battery was used in the model due to its market availability, popularity in this segment, and well-documented technical characteristics. It is worth noting that the model allows editing battery parameters, enabling a quick assessment of the cost-effectiveness of using an alternative solution—one that might be more economically or technically advantageous.

Analyses showed that a 6.4 kWh storage configuration provides the best balance between investment costs and increased self-consumption. The system significantly reduces the amount of energy fed into the grid, which, in a net-billing model, translates into a noticeable increase in savings and a faster return on investment. At the same time, the model reduces the impact of RES generation instability on load power, thus increasing energy security for local consumers.

This article confirms the validity of using simulation tools—such as MATLAB—in the energy system design process. Thanks to the capabilities of dynamic modeling, technical and economic analysis, and the flexible structure of simulators, it is possible to create realistic and reliable projects even at the concept stage. It is worthwhile to develop such approaches in the context of the growing number of prosumer installations, the energy transition, and the need to build independent, decentralized power sources, particularly in BIPV.

The analysis method used and the results obtained are valid for the assumed known load profile; however, the method can be successfully applied to various load profiles.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.T., S.M., L.K., N.S. and D.G.; methodology, G.T., N.S. and S.M.; software, N.S. and S.M.; validation, G.T., L.K. and D.G.; formal analysis, G.T., S.M., L.K., N.S., and D.G.; investigation, G.T., S.M., and N.S.; resources, G.T., S.M., N.S. and D.G.; data curation, S.M. and N.S.; writing—original draft preparation, G.T., S.M. and D.G.; writing—review and editing, G.T., L.K. and D.G.; visualization, S.M. and N.S.; supervision, L.K., G.T., and D.G.; project administration, L.K., G.T., S.M., N.S. and D.G.; funding acquisition, G.T. and S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Polish Ministry of Science, grant number 0212/SBAD/0633.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained in this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Belloni, E.; Bianchini, G.; Casini, M.; Faba, A.; Intravaia, M.; Laudani, A.; Lozito, G.M. An overview on building-integrated photovoltaics: Technological solutions, modeling, and control. Energy Build. 2024, 324, 114867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Management strategy for building—Photovoltaic with battery energy storage. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 2025, 20, ctae282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Ge, L.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, M.; Xu, Z. A Review of Distribution Grid Consumption Strategies Containing Distributed Photovoltaics. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, D.S.; Shabunko, V.; Krishna, A. A comprehensive review on building integrated photovoltaic systems: Emphasis to technological advancements, outdoor testing, and predictive maintenance. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 156, 111946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Lin, M.; Feng, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ma, W. Operation optimization strategy of a BIPV-battery storage hybrid system. Results Eng. 2023, 18, 101066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, R.; Yang, H.; Wang, Q.; Lin, J. Reviews of Photovoltaic and Energy Storage Systems in Buildings for Sustainable Power Generation and Utilization from Perspectives of System Integration and Optimization. Energies 2025, 18, 2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toosi, H.A. Life Cycle Cost Optimization of Battery Energy Storage Systems for BIPV-Supported Smart Buildings: A Techno-Economic Analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5820. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelsattar, M.; AbdelMoety, A.; Emad-Eldeen, A. Advanced Machine Learning Techniques for Predicting Power Generation and Fault Detection in Solar Photovoltaic Systems. Neural Comput. Appl. 2025, 37, 8825–8844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasecki, S. Rola Magazynów Energii W Procesie Transformacji Energetycznej. Available online: https://www.urzadzeniadlaenergetyki.pl/magazyny-energii/rola-magazynow-energii-w-procesie-transformacji-energetycznej (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- Hylla, P.; Trawiński, T.; Polnik, B.; Burlikowski, W.; Prostański, D. Overview of Hybrid Energy Storage Systems Combined with RES in Poland. Energies 2023, 16, 5792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyinka, A.M.; Esan, O.C.; Ijaola, A.O.; Farayibi, P.K. Advancements in Hybrid Energy Storage Systems for Enhancing Renewable Energy-to-Grid Integration. Sustain. Energy Res. 2024, 11, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamska, B. Magazyny energii niezbędnym elementem transformacji energetycznej. Energetyka Rozproszona 2022, 7, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowski, H. Technologie Magazynowania Energii. Cz. I, Źródła ciepła i energii elektrycznej. Inf. Instal. 2017, 2, 20. Available online: www.informacjainstal.com.pl (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Rey, S.O.; Romero, J.A.; Romero, L.T.; Martínez, À.F.; Roger, X.S.; Qamar, M.A.; Domínguez-García, J.L.; Gevorkov, L. Powering the Future: A Comprehensive Review of Battery Energy Storage Systems. Energies 2023, 16, 6344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.-J.; Chung, W.-H. Evaluation of Charging Methods for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Electronics 2023, 12, 4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemielity, J.; Czapla, Ł.; Rozenkiewicz, P. Techniczne aspekty projektowania bateryjnych magazynów energii w świetle doświadczeń z realizacji projektu GEKON. In Proceedings of the Materiały Konferencyjne XIX Konferencji Naukowej AKTUALNE PROBLEMY W ELEKTROENERGETYCE APE’19, Jastrzębia Góra, Polska, 12–14 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, S.J.; Thomas, P.; Rajan, E.; Anjali, R. Design and Prototype Modelling of a CC/CV Electric Vehicle Battery Charging Circuit. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Circuits and Systems in Digital Enterprise Technology (ICCSDET), Kottayam, India, 21–22 December 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 110–115. [Google Scholar]

- Martí-Florences, M.; Cecilia, A.; Costa-Castelló, R. Modelling and Estimation in Lithium-Ion Batteries: A Literature Review. Energies 2023, 16, 6846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafał, K.; Grabowski, P. Magazynowanie energii. Mag. Pol. Akad. Nauk. 2021, 65, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, A.C.-C.; Syue, B.Z.-W. Charge and Discharge Characteristics of Lead-Acid Battery and LiFePO4 Battery. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Power Electronics Conference, Sapporo, Japan, 21–24 June 2010; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 3175–3180. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R. Comparative analysis of ternary lithium batteries and lithium iron phosphate. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 606, 5001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Sun, Z.; Song, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, C.; Chang, F.; Yang, D.; Fu, X. Stochastic Scenario Generation Methods for Uncertainty in Wind and Photovoltaic Power Outputs: A Comprehensive Review. Energies 2025, 18, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minuto, F.D.; Crosato, M.; Schiera, D.S.; Borchiellini, R.; Lanzini, A. Shared energy in renewable energy communities: The benefits of east- and west-facing rooftop photovoltaic installations. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 5593–5601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorouri, H.; Safari, A.; Oshnoei, A.; Teodorescu, R. Voltage-Controlled SoC Estimation in Lithium-Ion Batteries: A Comparative Analysis of Equivalent Circuit Models. In Proceedings of the 26th European Conference on Power Electronics and Applications (EPE), Paris, France, 11 June 2025; 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Schimpe, M.; Naumann, M.; Truong, N.; Hesse, H.C.; Santhanagopalan, S.; Saxon, A.; Jossen, A. Energy efficiency evaluation of a stationary lithium-ion battery container storage system via electro-thermal modeling and detailed component analysis. Appl. Energy 2018, 210, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piller, S.; Perrin, M.; Jossen, A. Methods for state-of-charge determination and their applications. J. Power Sources 2001, 96, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Hu, B.; Yu, Z.; Wang, H.; Qu, L.; Yang, D.; Wang, J.; Li, W.; Bai, C.; Sun, Y. State-of-charge estimation of lithium-ion battery based on improved equivalent circuit model considering hysteresis combined with adaptive iterative unscented Kalman filtering. J. Energy Storage 2024, 102, 114105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, H.; Thomas, P.; Rajan, E. Capacity and State-of-Health Prediction of Lithium-Ion Batteries. Batteries 2025, 11, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Castellanos, A.; Pozo, D.; Bischi, A. Non-ideal Linear Operation Model for Li-ion Batteries. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2019, 35, 672–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustawa z Dnia 10 Kwietnia 1997 r.—Prawo Energetyczne. Dz.U. 1997, nr 54, poz. 348 z późn. zm., Art. 3 pkt 13a. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=wdu19970540348 (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Fotowoltaiki, A. Net-Billing Przykład Rozliczenia. Available online: https://akademia-fotowoltaiki.pl/net-billing-fotowoltaika-przyklady/ (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- E-Magazyny.pl. Magazyny Energii a Przepisy Prawne w Polsce w 2024 Roku. Available online: https://e-magazyny.pl/eksperckim-okiem/magazyny-energii-a-przepisy-prawne-w-polsce-w-2024-roku/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Globenergia. Czy Prosument Może Odsprzedawać Energię Z Magazynu? Odpowiedź Zaskakuje. Available online: https://globenergia.pl/czy-prosument-moze-odsprzedawac-energie-z-magazynu-odpowiedz-zaskakuje/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Enerad. 17 Lutego Rusza Nabór Na Dotacje Do Magazynów Energii Dla Firm—Do Zdobycia 900 mln zł. Available online: https://enerad.pl/17-lutego-rusza-nabor-na-dotacje-do-magazynow-energii-dla-firm-do-zdobycia-900-mln-zl/ (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Felis, P. Metody I Procedury Oceny Efektywności Inwestycji Rzeczowych Przedsiębiorstw; Wydawnictwo WSE-I: Warszawa, Polska, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Neugebauer, M.; Brandt, T.; Klement, J. Economic Analysis of Profitability of Using Energy Storage in a Net-Billing System. Energies 2024, 17, 3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baake, J.; Tao, Z. A Cost Modeling Framework for Modular Battery Energy Storage Systems. In Transport Research Arena Conference; Springer Nature: Cham, The Switzerland, 2024; pp. 247–253. [Google Scholar]

- REC 280 TP BLK—Datasheet. Available online: https://www.europe-solarstore.com/rec-280-tp-blk.html (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- GC LiFePO4 CAV13—CAV13PL—Datasheet. Available online: https://stylem.pl/upload/files/product/green-cell-akumulator-lifepo4-cav13-12-12-8v-125ah-1600wh-m8-163537.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Ross, S.A.; Westerfield, R.; Jaffe, J. Corporate Finance, 12th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 101–104. [Google Scholar]

- JK Active Balance BMS JK-B1A8S20P JK-B2A8S20P User Manual. Available online: https://energiepanda.com/jk-active-balance-bms-jk-b1a8s20p-jk-b2a8s20p-user-manual/ (accessed on 20 March 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).