Pretreatment Using Auto/Acid-Catalyzed Steam Explosion and Water Leaching to Upgrade the Fuel Properties of Wheat Straw for Pellet Production

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Experimental Treatments

2.3. Fuel and Physicochemical Properties of Biomass Samples

2.4. Thermogravimetric Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fuel and Physicochemical Properties of Treated Samples

3.1.1. Ultimate and Proximate Analysis

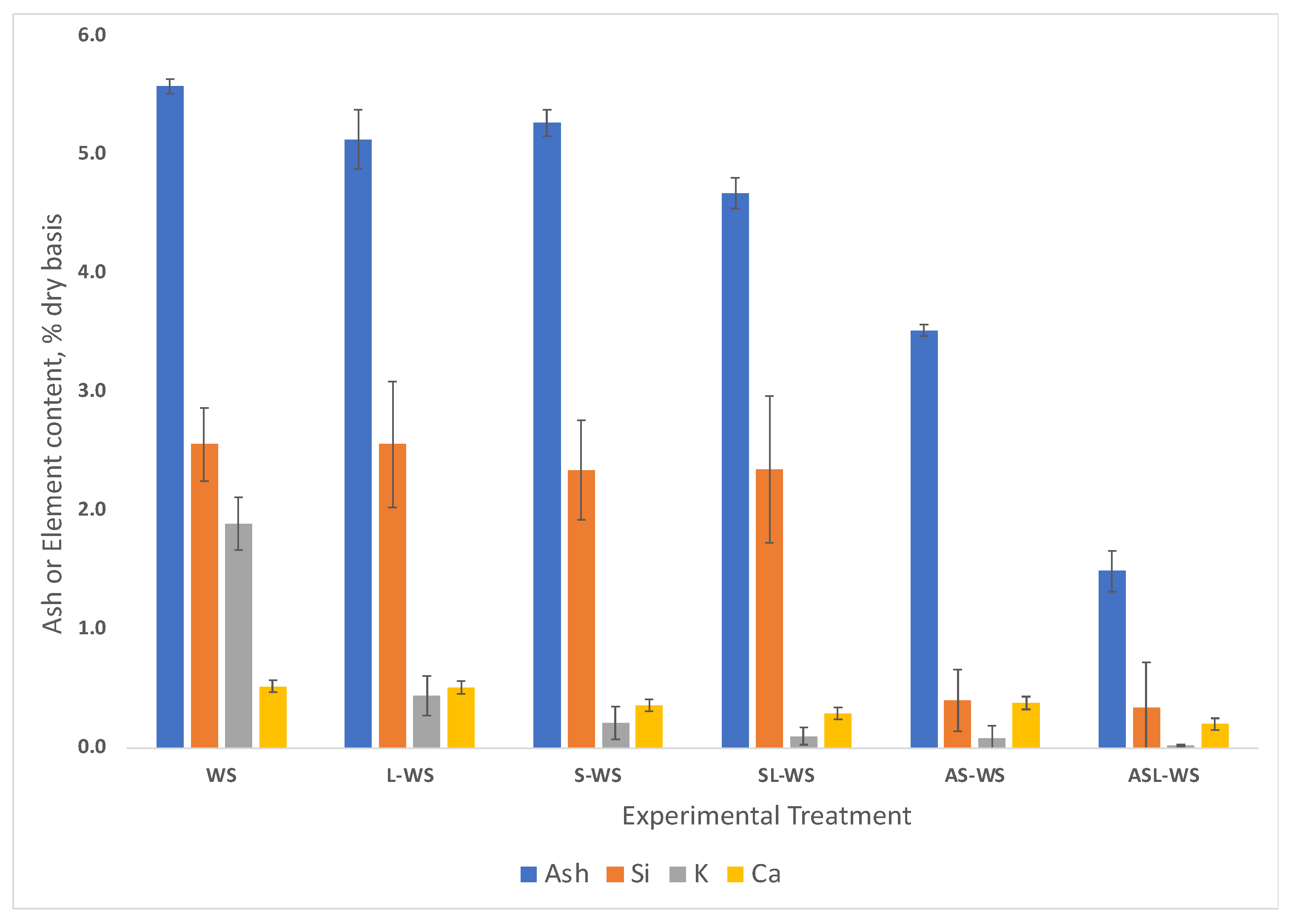

3.1.2. XRF Analysis

3.2. Structural Analysis—XRD Spectroscopy

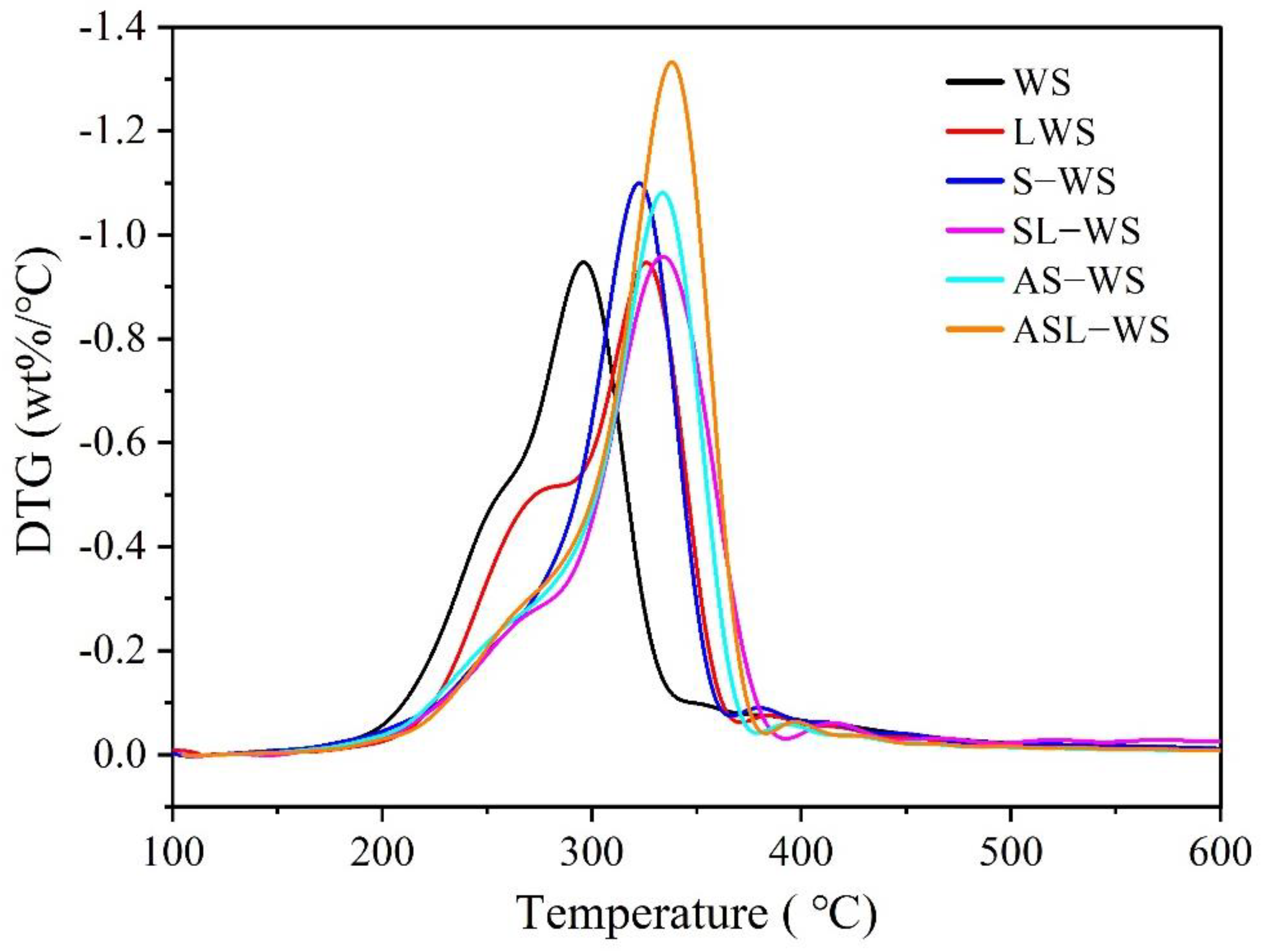

3.3. DTG and Analytical Pyrolysis Performance Analysis

3.4. DTG and Analytical Combustion Performance Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, C.; Zhang, W.; Qiu, X.; Xu, C. Hydrothermal Treatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass Towards Low-carbon Development: Production of High-value-added Bioproducts. EnergyChem 2024, 6, 00133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langholtz, M.H. Chapter 1: Background and Introduction. In 2023 Billion-Ton Report; Langholtz, M.H., Ed.; Oak Ridge National Laboratory: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mostafa, M.E.; Hu, S.; Wang, Y.; Su, S.; Hu, X.; Elsayed, S.A.; Xiang, J. The Significance of Pelletization Operating Conditions: An Analysis of Physical and Mechanical Characteristics as well as Energy Consumption of Biomass Pellets. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 105, 332–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElMekawy, A.; Diels, L.; De Wever, H.; Pant, D. Valorization of Cereal Based Biorefinery Byproducts: Reality and expectations. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 9014−9027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Qiu, F. Bioenergy in the Canadian Prairies: Assessment of Accessible Biomass from Agri-crop Residues and Identification of Potential Biorefinery Sites. Biomass Bioenergy 2020, 140, 105669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passoth, V.; Sandgren, M. Biofuel Production from Straw Hydrolysates: Current Achievements and Perspectives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 5105–5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilev, S.V.; Vassileva, C.G.; Song, Y.C.; Li, W.Y.; Feng, J. Ash Contents and Ash-forming Elements of Biomass and their Significance for Solid Biofuel Combustion. Fuel 2017, 208, 377–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Aston, J.E.; Lacey, J.A.; Thompson, V.S.; Thompson, D.N. Impact of Feedstock Quality and Variation on Biochemical and Thermochemical Conversion. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 65, 525–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerriero, G.; Hausman, J.F.; Legay, S. Silicon and the Plant Extracellular Matrix. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hupa, M.; Karlstrom Vainio, E. Biomass Combustion Technology Development—It is All About Chemical Details. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2017, 36, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Tian, X.; Liao, H.; Guo, Y.; Cheng, F. Improvement of Fly Ash Fusion Characteristics by Adding Metallurgical Slag at High Temperature for Production of Continuous Fiber. J. Clean Prod. 2018, 171, 464–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Yang, H.; Qian, K.; Wang, X.; Chen, H. Fusion and Transformation Properties of the Inorganic Components in Biomass Ash. Fuel 2014, 117, 1281–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S.K.; Jagtap, S.S.; Bedekar, A.A.; Bhatia, R.K.; Patel, A.K.; Pant, D.; Banu, J.R.; Rao, C.V.; Kim, Y.G.; Yang, Y.H. Recent Developments in Pretreatment Technologies on Lignocellulosic Biomass: Effect of Key Parameters, Technological Improvements, and Challenges. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 300, 122724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasiak, M.; Molenda, M.; Bańda, M.; Wiącek, J.; Parafiniuk, P.; Gondek, E. Mechanical Combustion Properties Sawdust-straw Pellets Blended in Different Proportions. Fuel Process. Technol. 2017, 156, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Thy, P.; Wang, L.; Anderson, S.N.; VanderGheynst, J.S.; Upadhyaya, S.K.; Jenkins, B.M. Influence of Leaching Pretreatment on Fuel Properties of Biomass. Fuel Process. Technol. 2014, 128, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmunds, C.W.; Hamilton, C.; Kim, K.; Chmely, S.C.; Labbé, N. Using a Chelating Agent to Generate Low Ash Bioenergy Feedstock. Biomass Bioenergy 2017, 96, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Turn, S.Q.; Morgan, T.; Li, D. Processing Freshly Harvested Banagrass to Improve Fuel Qualities: Effects of Operating Parameters. Biomass Bioenergy 2017, 105, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abelha, P.; Mourão Vilela, C.; Nanou, P.; Carbo, M.; Janssen, A.; Leiser, S. Combustion Improvements of Upgraded Biomass by Washing and Torrefaction. Fuel 2019, 253, 1018–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, Y.W.; Gamage, P.; Gunarathne, D.S. Hot Water Washing of Rice Husk for Ash Removal: The Effect of Washing Temperature, Washing Time and Particle Size. Renew. Energy 2020, 153, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, A.; Konttinen, J.; Joronen, T. Effect of different Washing Parameters on the Fuel Properties and Elemental Composition of Wheat Straw in Water-washing Pre-treatment. Part 2: Effect of Washing Temperature and Solid-to-liquid Ratio. Fuel 2021, 292, 1220209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamisaye, A.; Ige, A.R.; Adegoke, K.A.; Adegoke, I.A.; Bamidele, M.O.; Adeleke, O.; Idowu, M.A.; Nobanathi, W.M. H2SO4-treated and Raw Watermelon Waste Bio-briquettes: Comparative, Eco-friendly and Machine Learning Studies. Fuel 2024, 358, 129936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Wan, Z.; Smith, M.D.; Mohan, M.; Sokhansanj, S.; Lau, A.; Smith, J.C.; Rojas, O.J. Macroscale Properties and Atomic-scale Mechanisms of Ash Removal in Low-temperature Hydrothermal Carbonization. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 500, 156913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacey, J.A.; Emerson, R.M.; Thompson, D.N.; Westover, T.L. Ash Reduction Strategies in Corn Stover Facilitated by Anatomical and Size Fractionation. Biomass Bioenergy 2016, 90, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, H.A.; Sganzerla, W.G.; Larnaudie, V.; Veersma, R.J.; van Erven, G.; Shiva; Ríos-González, L.J.; Rodríguez-Jasso, R.M.; Rosero-Chasoy, G.; Ferrari, M.D.; et al. Advances in Process Design, Techno-economic Assessment and Environmental Aspects for Hydrothermal Pretreatment in the Fractionation of Biomass under Biorefinery Concept. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 369, 128469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Wu, J.; Ren, X.; Lau, A.; Rezaei, H.; Takada, M.; Bi, X.; Sokhansanj, S. Steam Explosion of Lignocellulosic Biomass for Multiple Advanced Bioenergy Processes: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 154, 111871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Deng, J.; Zhang, S.; Bicho, P.; Wu, Q. Effect of Steam Explosion Treatment on Characteristics of Wheat Straw. Ind. Crops Prod. 2010, 31, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondesson, P.M.; Galbe, M.; Zacchi, G. Ethanol and Biogas Production after Steam Pretreatment of Corn Stover with or without the Addition of Sulphuric Acid. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2013, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanase-Opedal, M.; Ghoreishi, S.; Hermundsgård, D.H.; Barth, T.; Moe, S.T.; Brusletto, R. Steam Explosion of Lignocellulosic Residues for Co-production of Value-added Chemicals and High-quality Pellets. Biomass Bioenergy 2024, 181, 107037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 17225-2/6; Solid biofuels—Fuel Specifications and Classes—Part 2: Graded Woody Pellets and Part 6: Graded Non-Woody Pellets. International Standards Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- García, R.; Gil, M.V.; Rubiera, F.; Pevida, C. Pelletization of Wood and Alternative Residual Biomass Blends for Producing Industrial Quality Pellets. Fuel 2019, 251, 739–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, I.; Negro, M.J.; Olivia, J.M.; Cabanas, A.; Manzanares, P.; Ballesteros, B. Ethanol Production from Steam Explosion Pretreated Wheat Straw. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2006, 129–132, 496–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, H.; Deng, J.; Zhang, X. Steam Explosion with a Refiner. Bioresources 2011, 6, 4468–4480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D3174-04; Standard Test Method for Ash in the Analysis Sample of Coal and Coke from Coal. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2004.

- ASTM D3175-89; Standard Test Method for Volatile Matter in the Analysis Sample of Coal and Coke. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1989.

- Shi, S.; Guan, W.; Blersch, D.; Li, J. Improving the Enzymatic Digestibility of Alkaline-Pretreated Lignocellulosic Biomass using polyDADMAC. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 162, 113244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Wang, G.; Bai, X.; Liu, J.; Wang, D.; Wang, Z. Combined Different Dehydration Pretreatments and Torrefaction to Upgrade Fuel Properties of Hybrid Pennisetum (Pennisetum americanum × P. purpureum). Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 263, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Singh, H.; Singh, B.; Mani, S. Torrefaction of Sorghum Biomass to Improve Fuel Properties. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 232, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adapa, P.; Tabil, L.; Schoenau, G.; Opoku, A. Pelleting Characteristics of Selected Biomass with and without Steam Explosion Pretreatment. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2010, 3, 62–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Chandra, R.P.; Sokhansanj, S.; Saddler, J.N. Influence of Steam Explosion Processes on the Durability and Enzymatic Digestibility of Wood Pellets. Fuel 2018, 211, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Deng, L.; Che, D. Analysis on Organic Compounds in Water Leachate from Biomass. Renew. Energy 2020, 155, 1070–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, M.; Raj, T.; Vijayaraj, M.; Chopra, A.; Gupta, R.P.; Tuli, D.K.; Kumar, R. Structural features of dilute acid, steam exploded, and alkali pretreated mustard stalk and their impact on enzymatic hydrolysis. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 124, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yuan, Q.; Cheng, G. Deconstruction of corncob by steam explosion pretreatment: Correlations between sugar conversion and recalcitrant structures. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 156, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Ma, X. The thermal behaviour of the co-combustion between paper sludge and rice straw. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 146, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, G. Combustion characteristics and kinetic analysis of biomass pellet fuel using thermogravimetric analysis. Processes 2021, 9, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Meng, J.; Moore, A.M.; Chang, J.; Gou, J.; Park, S. Thermogravimetric investigation on the degradation properties and combustion performance of bio-oils. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 152, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, K.; Takeno, K.; Ichinose, T.; Ogi, T.; Nakanishi, M. Gasification reaction kinetics on biomass char obtained as a by-product of gasification in an entrained-flow gasifier with steam and oxygen at 900–1000 °C. Fuel 2009, 88, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Description |

|---|---|

| WS | Wheat straw without any pretreatment (Control) |

| L–WS | Water leaching of wheat straw |

| S–WS | Auto-catalyzed steam explosion of wheat straw |

| SL–WS | Auto-catalyzed steam explosion of wheat straw followed by water leaching |

| AS–WS | Acid-catalyzed steam explosion of wheat straw |

| ASL–WS | Acid-catalyzed steam explosion of wheat straw followed by water leaching |

| Ultimate Analysis (% db) | Proximate Analysis (% db) | Fuel Ratio | HHV (MJ/kg) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | H | O | N | VM | Ash | FC | |||

| WS (untreated) | 44.9 ±0.07 | 5.71 ±0.05 | 48.8 ±0.15 | 0.60 ±0.14 | 79.9 ±0.10 | 5.58 ±0.06 | 14.8 ±0.09 | 0.19 ±0.001 | 18.0 ±0.06 |

| L-WS | 45.1 ±0.11 | 5.50 ±0.07 | 48.4 ±0.02 | 0.38 ±0.14 | 80.1 ±0.13 | 5.13 ±0.25 | 15.0 ±0.17 | 0.19 ±0.001 | 18.2 ±0.19 |

| S-WS | 47.6 ±0.12 | 5.51 ±0.01 | 46.4 ±0.02 | 0.38 ±0.14 | 74.9 ±0.04 | 5.27 ±0.11 | 19.4 ±0.05 | 0.26 ±0.001 | 20.0 ±0.13 |

| SL-WS | 48.0 ±0.06 | 6.07 ±0.03 | 46.1 ±0.04 | 0.48 ±0.14 | 76.3 ±0.17 | 4.68 ±0.13 | 19.2 ±0.06 | 0.25 ±0.001 | 20.1 ±0.17 |

| AS-WS | 48.4 ±0.13 | 6.01 ±0.01 | 44.0 ±0.10 | 0.48 ±0.14 | 72.3 ±0.15 | 3.52 ±0.05 | 24.1 ±0.03 | 0.34 ±0.001 | 21.6 ±0.06 |

| ASL-WS | 48.7 ±0.11 | 6.03 ±0.07 | 44.6 ±0.01 | 0.58 ±0.14 | 73.5 ±0.08 | 1.49 ±0.17 | 25.0 ±0.06 | 0.34 ±0.001 | 21.9 ±0.10 |

| Ym | η | ηe,Si | ηe,Ca | ηe,K | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-WS | 94.5 | 13.1 | 5.6 | 3.5 | 78.0 |

| S-WS | 73.4 | 30.7 | 33.7 | 46.1 | 86.2 |

| SL-WS | 70.6 | 40.8 | 35.7 | 60.5 | 96.3 |

| AS-WS | 68.2 | 57.0 | 89.7 | 47.4 | 97.0 |

| ASL-WS | 66.6 | 82.2 | 91.1 | 74.3 | 99.6 |

| Hemicellulose Content, %db | Cellulose Content, %db | Lignin Content, %db | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WS | 21.7 ± 0.6 | 43.2 ± 0.9 | 22.7 ± 1.2 |

| S-WS | 15.0 ± 0.2 | 60.0 ± 0.8 | 21.5 ± 0.7 |

| AS-WS | 9.1 ± 0.1 | 52.0 ± 0.8 | 33.3 ± 2.1 |

| CrI (%) | Tin (°C) | Tmax (°C) | Rmax (wt% min−1) | ΔT0.5 (°C) | Di (10−6 min−1 °C−3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WS | 41.5 | 202.9 | 297.5 | 18.5 | 50.4 | 6.1 |

| L-WS | 41.7 | 204.0 | 306.6 | 18.3 | 47.5 | 6.2 |

| S-WS | 43.4 | 224.6 | 326.0 | 21.4 | 39.2 | 7.5 |

| SL-WS | 43.4 | 225.7 | 339.8 | 21.2 | 38.4 | 7.2 |

| AS-WS | 36.9 | 225.7 | 356.7 | 23.4 | 40.2 | 7.2 |

| ASL-WS | 37.0 | 227.2 | 366.5 | 24.1 | 41.2 | 7.0 |

| Devolatization Stage | ||||||||

| Rmax (wt% min−1) | Tmax (°C) | Ti (°C) | Tb (°C) | ΔT0.5 (°C) | Di × 10−4 (min−1 °C−2) | Db × 10−6 (min−1 °C−3) | S × 10−6 (min−2 °C−3) | |

| WS | 20.9 | 261.5 | 230.8 | 320.7 | 58.3 | 3.46 | 5.93 | 0.26 |

| L-WS | 19.5 | 290.3 | 244.6 | 324.7 | 64.3 | 2.75 | 4.28 | 0.24 |

| S-WS | 24.8 | 289.9 | 263.2 | 321.0 | 37.9 | 3.24 | 8.56 | 0.37 |

| SL-WS | 27.1 | 290.8 | 267.2 | 320.4 | 38.2 | 3.49 | 9.13 | 0.43 |

| AS-WS | 34.1 | 294.0 | 267.5 | 320.1 | 35.6 | 4.34 | 12.2 | 0.54 |

| ASL-WS | 43.1 | 293.6 | 270.0 | 321.1 | 33.5 | 5.44 | 16.3 | 0.69 |

| Combustion stage | ||||||||

| WS | 0.6 | 367.2 | 349.6 | 423.3 | 40.8 | 1.01 | 2.47 | 0.07 |

| L-WS | 0.5 | 395.1 | 379.7 | 445.4 | 43.6 | 0.58 | 1.33 | 0.04 |

| S-WS | 0.4 | 415.1 | 398.7 | 470.6 | 41.8 | 0.47 | 1.13 | 0.03 |

| SL-WS | 0.3 | 427.8 | 403.3 | 496.3 | 74.3 | 0.34 | 0.46 | 0.02 |

| AS-WS | 0.5 | 399.7 | 385.3 | 426.4 | 32.8 | 0.67 | 2.03 | 0.08 |

| ASL-WS | 0.2 | 432.8 | 398.8 | 462.1 | 38.1 | 0.20 | 0.53 | 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, Y.; Wu, J.; Sokhansanj, S.; Saddler, J.; Lau, A. Pretreatment Using Auto/Acid-Catalyzed Steam Explosion and Water Leaching to Upgrade the Fuel Properties of Wheat Straw for Pellet Production. Energies 2025, 18, 6545. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246545

Yu Y, Wu J, Sokhansanj S, Saddler J, Lau A. Pretreatment Using Auto/Acid-Catalyzed Steam Explosion and Water Leaching to Upgrade the Fuel Properties of Wheat Straw for Pellet Production. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6545. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246545

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Yan, Jie Wu, Shahabaddine Sokhansanj, Jack Saddler, and Anthony Lau. 2025. "Pretreatment Using Auto/Acid-Catalyzed Steam Explosion and Water Leaching to Upgrade the Fuel Properties of Wheat Straw for Pellet Production" Energies 18, no. 24: 6545. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246545

APA StyleYu, Y., Wu, J., Sokhansanj, S., Saddler, J., & Lau, A. (2025). Pretreatment Using Auto/Acid-Catalyzed Steam Explosion and Water Leaching to Upgrade the Fuel Properties of Wheat Straw for Pellet Production. Energies, 18(24), 6545. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246545