Abstract

The chemical looping steam methane reforming (CL-SMR) process is an efficient and low-carbon hydrogen production technology. It enables high-efficiency methane conversion and inherent CO2 separation through the cyclic utilization of oxygen carriers. Perovskite-materials are regarded as potential oxygen carriers due to their superior oxygen transport capabilities, tunable chemical compositions, and excellent high-temperature stability. This review summarizes recent advances in perovskite-based oxygen carriers, focusing on the effects of elemental doping and structural characteristics on key performance metrics, including methane conversion rate, CO selectivity, H2/CO ratio, and hydrogen yield. Based on existing research findings, we propose optimization strategies for improving the reaction performance of perovskite oxygen carriers in CL-SMR processes. Additionally, we outline future research directions, such as the design of high-efficiency oxygen carriers and in-depth exploration of reaction mechanisms. This work provides a comprehensive theoretical framework and research roadmap for advancing CL-SMR technology, while identifying potential pathways for developing efficient and stable perovskite-based oxygen carriers.

1. Introduction

The extensive utilization of traditional fossil fuels (e.g., coal, oil, and natural gas) is the primary anthropogenic source of greenhouse gas emissions, especially CO2, leading to the greenhouse effect and significant changes in the global climate system, manifested by frequent extreme weather events, rising sea levels, and ecosystem imbalances. To address this challenge, developing clean energy systems and efficient CO2 emission reduction technologies has become a global consensus. Hydrogen energy, with its high energy density, zero carbon emissions, and versatile application potential, is regarded as an ideal energy carrier [1,2]. Whether replacing fossil fuels in industrial production processes or acting as a clean power source in fuel cells, hydrogen demonstrates significant application value [3]. As global carbon neutrality goals advance, developing efficient, low-cost, and environmentally friendly hydrogen production methods has become a key focus in current energy research.

Hydrogen production technologies are shifting towards low-carbon and high-efficiency routes. Alkaline water electrolysis (AWE), a representative of conventional water electrolysis, has advanced rapidly with the development of renewable energy integration and advanced electrode materials [4]. Powered by renewable sources, AWE can directly convert electricity into high-purity hydrogen and is a cornerstone of green hydrogen production. Nevertheless, the high cost and intermittency of renewable electricity limit its large-scale deployment.

In parallel, photocatalytic and photo-thermal routes have gained attention for their potential to utilize solar energy directly. For instance, TiO2-In2O3-based ternary heterojunctions [5] and Cu2O-modified composite catalysts [6] have demonstrated remarkable charge-separation efficiency and significantly enhanced hydrogen evolution rates under visible light. Despite these advances, photocatalytic hydrogen production still faces fundamental challenges in photon utilization efficiency, catalyst stability, and scalability, limiting its current use to laboratory and prototype scales.

Therefore, liquid organic hydrogen carriers (LOHCs) such as formic acid offer an alternative hydrogen storage and release route. The use of Au nanoparticles confined in porous polymer matrices has achieved efficient and selective hydrogen release from formic acid at mild conditions, highlighting the potential of catalytic dehydrogenation strategies [7]. Nevertheless, the high cost of noble metals and the carbon footprint of formic acid synthesis still hinder its large-scale deployment.

Currently, steam methane reforming (SMR) is the dominant method for global hydrogen production [8,9]. As a mainstream hydrogen manufacturing process, SMR is widely employed in the natural gas and petrochemical industries—particularly for hydrogen and syngas production—due to its advantages such as abundant feedstock availability, mature technology, and high production efficiency. Compared to AWE, SMR avoids reliance on renewable power infrastructure. Meanwhile, in contrast to photocatalytic and liquid organic hydrogen carrier (LOHC) systems, it offers higher energy density, better scalability, and greater compatibility with existing natural gas networks.

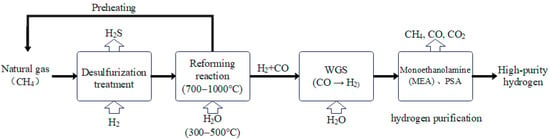

Figure 1 shows the principle diagram of methane steam reforming [10]. Firstly, the preheated natural gas undergoes sulfur removal through adsorption or hydrogenation to prevent catalyst poisoning. Then, methane (CH4) reacts with water vapor (H2O) under the action of a catalyst (such as Ni/Al2O3) at a temperature range of 700–1000 °C to form carbon monoxide (CO) and hydrogen (H2), which require external heating. The water-to-carbon ratio is usually controlled at 2.5–3.5 to inhibit carbon deposition. Next, carbon monoxide is further converted into CO2 and H2 through the water-gas shift reaction (WGSR) to increase the hydrogen yield. Finally, impurities are removed through pressure swing adsorption (PSA) or membrane separation technology to obtain high-purity hydrogen.

Figure 1.

Simplified flow diagram of the conventional SMR process.

However, SMR has obvious limitations: its highly endothermic nature requires burning large amounts of methane to maintain high temperatures, leading to significant carbon emissions; meanwhile, the multi-step purification process increases both energy consumption and process complexity. The drawbacks of existing methane reforming technologies are not limited to SMR; methane reforming mainly includes three variants [11], and their core reaction equations are shown below (Equations (1)–(3)):

Steam methane reforming:

Dry reforming of methane:

Partial oxidation of methane:

Based on the above reaction characteristics, all three variants have inherent defects: Equation (1) corresponds to steam methane reforming [12], whose highly endothermic nature requires methane combustion for energy supply, exacerbating carbon emissions; Equation (2) corresponds to dry reforming of methane (DRM) [13], whose higher enthalpy change results in significantly higher energy consumption than SMR; Equation (3) corresponds to partial oxidation of methane (POM) [14]. Although it is an exothermic reaction, the mixing of methane and oxygen poses flammability risks; additional processes are needed to separate syngas from nitrogen in air, and the reaction relies on noble metal catalysts.

With the proposal of China’s “dual carbon” goals (carbon peaking and carbon neutrality) [15], the development of low-carbon and clean energy technologies has become essential for sustainable development. Chemical looping methane reforming (CL-SMR) offers a promising route toward sustainable energy systems [16]. This process combines catalytic CH4 conversion with in situ CO2 separation, producing hydrogen with a lower carbon footprint. The purpose of this paper is to review the use of perovskite oxygen carriers in CL-SMR. Unlike previous reviews, this work focuses on anti-coking as an important part of stability for perovskite oxygen carriers. It also systematically examines how A-site doping, B-site doping, and A/B-site Co doping affect the performance of perovskite oxygen carriers. Finally, we suggest possible strategies for designing efficient and stable perovskite-based oxygen carriers.

2. Perovskite as Oxygen Carrier in CL-SMR

2.1. CL-SMR

Chemical looping technology is based on the principle of chemical looping reactions, achieving energy conversion by separating fuels and oxidizers. This technology uses solid oxygen carriers instead of oxygen in air to participate in reactions, enabling efficient conversion of methane to hydrogen without direct contact between methane and oxygen [17]. This approach not only reduces energy loss during energy conversion to improve energy utilization efficiency but also captures large amounts of CO2, effectively solving the problem of CO2 emissions in traditional combustion processes [18]. Therefore, using chemical looping technology to convert methane into hydrogen and CO exhibits enormous application potential in clean energy development [19,20].

The CL-SMR process involves two core reactions: the reaction between the oxygen carrier and methane (Equation (4)) and the reaction between the reduced oxygen carrier and steam (Equation (5)):

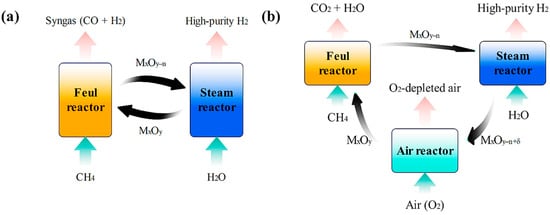

As shown in Figure 2, CL-SMR typically adopts a dual-reactor (Figure 2a) or triple-bed reactor system (Figure 2b): in the dual-reactor system, the reduced oxygen carrier reacts with steam in the steam reactor to produce H2; in the triple-reactor system, an additional air reactor (AR) is installed to reoxidize the reduced oxygen carrier, enabling continuous cycling of the oxygen carrier [21,22].

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of dual-reactor (a) and triple-reactor systems for CL-SMR (b).

In the fuel reactor (FR), methane undergoes oxidation reactions. There are two possible outcomes of this reaction: one is partial oxidation, which produces CO and H2; the other is complete oxidation, which generates CO2 and H2O [23]. Subsequently, the reduced oxygen carrier enters the steam reactor and reacts with water vapor, thereby producing high-purity hydrogen [24]. For the triple-reactor system, the situation is different–the oxygen carrier needs to be further oxidized in the air reactor to continue participating in the chemical looping cycle [25]. Compared with traditional SMR technology, CL-SMR has distinct advantages: it can not only directly produce high-purity hydrogen but also avoid CO2 generation with the participation of steam, thus providing a cleaner solution for carbon emission reduction [26].

2.2. Perovskite Oxygen Carriers

In the research and application of chemical looping technology, oxygen carrier materials are key factors determining reaction rate and efficiency, playing a core functional role [27,28]. Between the fuel reactor and air reactor, oxygen carriers achieve efficient transfer of lattice oxygen through a redox (reduction-oxidation) cycle mechanism, thereby enabling precise selective oxidation of fuels and directional regulation of products. Therefore, developing oxygen carriers with high stability, high redox rate, and high oxygen transport capacity has become a research hotspot in this field [29].

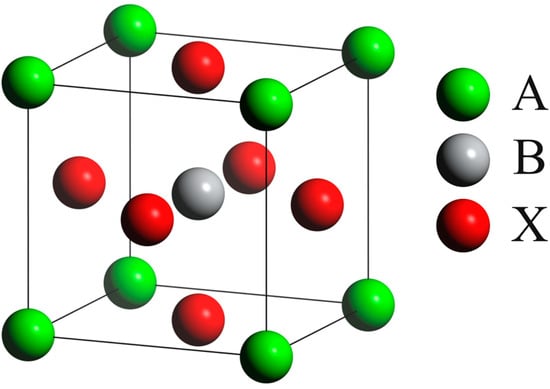

Among various oxygen carrier materials, perovskites possess unique crystal structures, and their compositional flexibility and diverse physicochemical properties have attracted widespread attention. Perovskite was first discovered by Gustav Rose in the Ural Mountains of Russia in 1837 and named in honor of the Russian mineralogist L. A. Perovski (1792–1856) [30]. It usually includes simple perovskite structures, double perovskite structures, and layered perovskite structures, and has excellent physical co-chemical properties. As shown in Figure 3, perovskites have an ABX3-type crystal structure with a specific spatial arrangement in the lattice. The A-site is occupied by large-radius cations, such as divalent alkali metals, alkaline earth metals, or rare earth elements [31], and these cations are located at the corners of the perovskite cubic unit cell. Meanwhile, the B-site consists of small-radius transition metal cations, like Ti4+ and Fe3+, which are positioned at the center of octahedrons. Additionally, the X-site is usually occupied by oxygen or halogen ions, and these ions are located at the face centers of the cubic unit cell [32].

Figure 3.

Crystal structure of the perovskite structure ABX3 [33].

Perovskites and their derivative structures exhibit high stability and multifunctionality, which enables them to accommodate various cations in their lattice and thus achieve flexible regulation of oxygen transport performance. Perovskites and their derivative structures have become ideal oxygen carrier materials in chemical looping technology due to their high stability and multifunctionality [34]. This multifunctionality and tunability make perovskites prominent in the field of catalysis, especially the application of lanthanum-based perovskites in methane chemical looping reforming: doping and modifying B-site cations can significantly enhance their catalytic activity and redox performance, enabling efficient methane conversion and hydrogen production [35].

Since the 1970s, research on the perovskite structures has spurred the development of diverse synthesis methods, advancing their catalytic applications. Several preparation techniques, including the Pechini method [36,37,38], the sol–gel method [37,39,40,41], the wet impregnation method [42], and the solid-state reactions method [43,44], have been employed to produce perovskite-based oxygen carriers for chemical looping processes [45]. Each method exhibits distinct advantages and limitations in terms of product performance and scalability.

The Pechini and sol–gel methods achieve excellent metal homogeneity and doping control, making them suitable for laboratory-scale optimization of composition and microstructure. However, both methods involve relatively high costs, generate liquid waste, and face challenges in viscosity control and residue treatment, limiting their large-scale application. In contrast, the wet impregnation and solid-state reactions offer more practical pathways for industrial production. Wet impregnation uses readily available raw materials and is easily scalable at low cost, though it often encounters issues such as metal aggregation and sintering. The solid-state approach, based on direct calcination of oxide or carbonate powders, is simple and economical for mass production, yet requires prolonged high-temperature treatment and subsequent grinding. The sol–gel and Pechini methods improve metal homogeneity, enhancing lattice oxygen mobility and reducing carbon deposition; wet impregnation may cause metal aggregation, weakening anti-sintering and anti-coking properties; solid-state reactions require high-temperature calcination, which affects the specific surface area and active site density, indirectly influencing reactivity.

For engineering applications, solid-phase synthesis or wet impregnation on robust substrates are recommended as primary options, combined with cost-effective A/B-site doping to verify stability and assess economic feasibility. At the laboratory stage, the sol–gel and Pechini methods remain valuable for precise doping screening and microstructure optimization. Collectively, these synthesis routes establish a foundation for tailoring the properties of perovskite oxygen carriers. Current research continues to focus on optimizing elemental doping strategies to regulate physicochemical properties, further expanding their applicability in chemical looping steam methane reforming and other emerging fields.

2.3. Research on Carbon Deposition

In the process of hydrogen production via CL-SMR, the production of high-purity hydrogen in the steam reactor is prone to contamination, which is attributed to carbon deposition on oxygen carriers during the reduction process. These carbons deposited on the surface of oxygen carriers react with subsequent water vapor to generate carbon oxides, thereby affecting hydrogen purity. There are four main reaction pathways for carbon deposition: methane cracking, CO disproportionation, CO hydrogenation, and CO2 hydrogenation. Among them, methane cracking is the primary cause of carbon deposition in hydrogen production via CL-SMR [46].

The anti-coking performance of oxygen carriers is generally positively correlated with lattice oxygen mobility [47], and this correlation has been verified by multiple studies. From the perspective of process conditions, higher fuel reactor temperature and oxygen content can significantly reduce carbon deposition, while the presence of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) in fuel gas exacerbates it. Essentially, process parameters affect coking by regulating lattice oxygen diffusion efficiency: high temperature promotes lattice oxygen migration, high oxygen content enhances oxygen supply, and H2S poisons active sites to inhibit oxygen transport [48].

In terms of material doping optimization, doping Co (as a second redox-active metal) into La-Fe-based perovskites can significantly reduce carbon deposition during the reduction process [49]. It is pointed out that introducing specific metals into Fe-containing oxygen carriers is a feasible approach to address carbon deposition when methane is used as a reducing agent. These metals need to meet two key conditions: they should be capable of forming solid solutions/alloys with iron and possess redox activity. Further studies have shown that the synergistic regulation of Co doping and Silicalite-1 content can also optimize anti-coking performance, and an appropriate amount of Silicalite-1 can reduce carbon deposition on the surfaces of LaFe0.9Co0.1O3/10%S-1 and LaFe0.8Co0.2O3/10%S-1 [50]. Lori Nalbandian et al. [51] investigated that, when using La1−xSrxMγFe1−γO3−δ (M = Ni, Co, Cr, Cu) as oxygen carriers, the carbon generation rate was the lowest, when δ ranged between 0.2 and 0.6 g-atoms O/mol solid in a low-oxygen environment. This result further confirms the core correlation that “higher lattice oxygen mobility leads to better anti-coking performance.

Raman spectroscopy is commonly used to distinguish coke types: the intensity ratio of D-band to G-band (ID/IG) > 1.0 indicates amorphous carbon, while ID/IG < 0.8 corresponds to graphitized carbon. Notably, amorphous carbon on perovskite surfaces can be easily oxidized and removed by lattice oxygen, whereas graphitized carbon tends to block active sites permanently [49,52]. Preventing carbon deposition can also be achieved by limiting the reduction degree of oxygen carriers or oxidizing deposited carbon using lattice oxygen. Therefore, studying the methane cracking process and the oxygen diffusion capacity of oxygen carriers is crucial for inhibiting carbon deposition.

In addition, the A-site doping of LaFeO3 perovskite can also inhibit carbon deposition. Yuan et al. [53] used LaxCe1−xFexNi1−xO3 as oxygen carriers and studied the influence of carbon deposition in chemical looping cycles by doping Ce and Ni ions. The results showed that the La0.6Ce0.4Fe0.6Ni0.4O3 oxygen carrier calcined at low temperature can enhance its carbon deposition resistance during cycles.

From the perspective of the overall technical characteristics of CL-SMR, as an innovative combustion and gasification technology, CL-SMR features high efficiency, low carbon emissions, and the capability to directly produce pure hydrogen. It is a two-step reaction process based on oxygen carriers, with its core lying in the cyclic utilization of oxygen carriers their performance directly determines the reaction efficiency, hydrogen selectivity, and cyclic stability. According to material types, oxygen carriers are mainly divided into two categories: metal oxide-based and composite oxide-based (e.g., perovskites). The following sections will discuss and compare the research advancements of some metal oxide oxygen carriers and perovskite composite oxide oxygen carriers, building on the anti-coking performance analysis of perovskites above.

In summary, there are two main effective methods to regulate perovskites for eliminating carbon deposition on oxygen carriers: (1) Surface modification: Adding alkali metals or other metals as secondary active metals, or adjusting their size to improve lattice oxygen mobility and thereby reduce carbon deposition. (2) Structural design: Adopting a three-dimensionally ordered macroporous (3DOM) structure, which has a large specific surface area, low mass transfer resistance, and abundant active sites, enabling the effective inhibition of carbon deposition.

3. Comparative Study of Oxygen Carriers for CL-SMR

To understand the progress and unique advantages of perovskite-based oxygen carriers, it is very beneficial to first examine the performance and limitations of traditional metal oxide systems. This section briefly reviews metal oxide oxygen carriers, as described below. The inherent challenges of these materials provide a fundamental basis for the subsequent research focus to shift towards more tunable and stable perovskite structures.

3.1. Metal Oxide-Based Oxygen Carriers

Metal oxide-based oxygen carriers are included as a “comparative baseline”—their high oxygen transport capacity but poor cyclic stability highlight the advantages of perovskites’ structural tunability. Common metal oxide-based oxygen carriers include nickel-based, iron-based, copper-based, and manganese-based materials, which have attracted widespread attention due to their low cost, high activity, and ease of large-scale preparation.

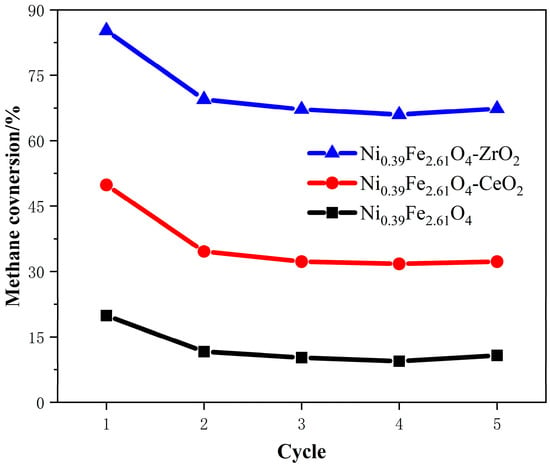

In the study of metal oxide oxygen carriers, Yin et al. [54] proposed and prepared a core–shell structured Fe@Ce oxygen carrier (with a Ce shell encapsulating an Fe core). This design combines the excellent ionic conductivity of Ce and the high oxygen storage capacity of iron oxide. Compared with Fe-Ce composite oxygen carriers, the Fe@Ce structure exhibits significantly enhanced syngas production, hydrogen yield, CO selectivity, and methane conversion. Garai et al. [55] studied the performance of Ni-Fe oxygen carriers supported on Ce and ZrO2 in CL-SMR. As shown in Figure 4, it can be seen that after repeated cycling, Ni0.39Fe2.61O4-ZrO2 exhibits the best performance among the three carriers. In the first cycle tested, the methane conversion rate of Ni0.39Fe2.61O4-ZrO2 was 86%. In the second cycle, this proportion dropped to 69%, and the conversion rate remained almost unchanged in the subsequent cycles. This can be attributed to the growth and adhesion of particles during the water decomposition step. Table 1 summarizes the performance of metal oxides–most exhibit >90% initial methane conversion but suffer from sintering (Fe2O3-based) or coking (Ni-based), a challenge that perovskites address via doping and structural design. The summary of other relevant research results is shown in Table 1.

Figure 4.

Cyclability of three oxygen carriers for methane conversion [55].

Table 1.

Studies on metal oxide-based oxygen carriers for Cl-SMR.

However, conventional metal oxides have obvious limitations in CL-SMR applications: (1) They are prone to sintering or phase transitions (e.g., reduction in Fe2O3 to Fe3O4 or FeO) at high temperatures, leading to structural degradation and activity loss. (2) Deep reduction processes generate metallic species that catalyze methane cracking reactions, resulting in severe carbon deposition and reducing reaction efficiency and cycling stability. (3) The relatively simple composition and structure of metal oxides limit further performance optimization through flexible regulation. These limitations have driven the shift in research focus to perovskite-type oxygen carriers, which have better structural tunability and high-temperature stability.

To overcome these issues, researchers have begun to explore other types of oxygen carriers, among which perovskite-type materials have attracted widespread attention due to their unique crystal structures, excellent oxygen transport properties, and high tunability.

3.2. Perovskite-Based Oxygen Carriers

Compared with metal oxides, perovskite-based oxygen carriers exhibit superior structural stability under high temperatures–A/B-site doping enables precise regulation of oxygen vacancies, addressing the sintering and coking issues of metal oxides. Perovskite-type oxygen carriers exhibit excellent oxygen transport properties, high-temperature stability, and anti-coking ability due to their unique crystal structures and tunable chemical compositions. This section focuses on the structural characteristics, performance advantages of perovskite-type oxygen carriers, and their research progress in hydrogen production via CL-SMR, with relevant research results summarized in Table 2.

The performance optimization of perovskite oxygen carriers mainly relies on A-site/B-site doping, with elements such as Co, Sr, and Ni showing the most significant regulatory effects: Co doping increases surface active sites and enhances reducibility. Sr doping promotes oxygen migration by forming oxygen vacancies. Ni doping strengthens oxygen donation capacity and methane dissociation.

Zheng et al. [61] synthesized and evaluated La1−xMnCuxO3 (x = 0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.15, 0.2) perovskite oxygen carriers for CL-SMR. The results showed that the incorporation of Cu improved the reducibility, oxygen mobility, and reactivity of the oxygen carrier. Furthermore, the metal homogeneity of the oxygen carrier prepared via the sol–gel method further enhanced these effects. Among them, La0.85MnCu0.15O3 and La0.8MnCu0.2O3 had a H2/CO ratio of approximately 2 (1.92–2.10), and La0.8MnCu0.2O3 showed nearly 100% CO selectivity after 1600 s. Yin et al. [62] investigated Al-doped LaMnO3+δ perovskites and found that the introduction of Al into LaMn O3+δ perovskite will lead to an increase in the symmetry of the crystal structure, which will weaken the strength of Mn-O bonds and the confinement of lattice oxygen, promote the formation of oxygen vacancies, and increase the release rate of selective oxygen and the yield of syngas. LaMn0.5Al0.5O3+δ (sol–gel method) exhibited optimal performance, with 96.4% CO selectivity higher than the solid-state synthesized samples (≈90%) due to better metal dispersion. It exhibited hydrogen yields of 3.32 mmol/g (reduction) and 1.98 mmol/g (oxidation), with a H2/CO ratio of 2. The team also studied LaMn1-xBxO3+δ (B = Fe, Co, Ni; x = 0.1–0.3), [52], and the results showed that Fe, Co, and Ni doping all improved oxygen mobility, CO selectivity, and H2 yield. Fe doping into LaMnO3+δ can effectively stabilize the crystal structure, while Co doping enhances reactivity. This discrepancy arises from the stronger Mn-O bond reinforcement by Fe compared with the flexible redox pairs of Co. Among them, LaMn0.7Fe0.3O3+δ had the highest CO selectivity (90.6%), with a H2/CO ratio of 2.

Yin et al. [63] further studied the performance of LaMnO3+δ doped with Co and Sr and found that the charge unbalances that aroused by the substitution of metal Co are mainly compensated by the increase in metal valence states, which may induce the valency pair (Fe4+/Fe5+, Co2+) and (Fe3+, Co3+) to provide active sites for methane dissociation. After 50 consecutive redox cycles, La0.8Sr0.2Mn0.5Co0.5O3+δ retained over 90% of its initial methane conversion rate–significantly better than Ni0.39Fe2.61O4-ZrO2, which lost 17% of its conversion after two cycles. Zhao et al. [64] investigated the structure and performance of double perovskite oxides LaSrFe2−xCoxO6 (x = 0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8) in CL-SMR. The results show that the selectivity of hydrogen and CO of the five oxygen carriers increases in the initial stage and tends to stabilize after 8 to 10 min. However, it is worth noting that the hydrogen selectivity change in the LaSrFe2O6 sample seems irregular, with two distinct fluctuation points. Ultimately, it is attributed to the delay in the transfer of lattice oxygen from the bulk. It once again proves that the substitution of metallic cobalt has a positive effect on oxygen mobility. The optimal Co substitution ratio in LaSrFe2−xCoxO6 was x = 0.4–0.6, achieving 70% methane conversion, an H2/CO ratio of 2, an average H2 yield of 2.89–3.33 mmol/g, and a carbon deposition rate of 1.46–1.61 wt%―inhibited by Co-induced lattice oxygen mobility enhancement.

He et al. [65] studied the effect of Sr doping on the performance of La1−xSrxFeO3 (x = 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7) perovskite oxides as oxygen carriers for CL-SMR and found that the substitution of Sr2+ for La3+ generates an electronic unbalance, compensated by oxygen vacancies and/or Fe3+ oxidation to Fe4+/Fe5+. For this series, La0.7Sr0.3FeO3 showed optimal performance: Sr doping (x = 0.3) generates oxygen vacancies and weakens Fe-O bonds (5.9 eV vs. 6.8 eV for undoped LaFeO3), balancing oxygen mobility and phase stability; x > 0.3 causes lattice distortion, and x < 0.3 limits active sites. It achieved 80% methane conversion during partial oxidation at 850 °C, an average H2/CO ratio close to 2, and 96% H2 purity during water splitting. Shen et al. [66] studied the structure–activity relationship of Ni-substituted LaFe1−xNixO3 (x = 0.05–0.3) perovskites in CL-SMR, focusing on reactivity and anti-coking ability. The results showed that the substitution of Ni for Fe in perovskite induces charge unbalances, which are subsequently compensated by the increase in metal valence and more oxygen vacancies. The XPS and TG results showed Ni substitution would improve the amount of adsorbed oxygen, thereby inhibiting the formation of carbon deposition. But high Ni-content generates carbon deposition more easily. The oxygen carrier with x = 0.1 (LaFe0.9Ni0.1O3) exhibited excellent regenerability and thermal stability, with 90% methane conversion, an H2/CO ratio of approximately 2.5, a H2 yield of 83.9 mL/g, and a carbon deposition rate of 0.9 wt% during methane conversion.

Cao et al. [67] systematically screened perovskite oxygen carriers with different A-site (La, Sr) and B-site (Co, Fe) elements supported on various materials (CeO2, ZrO2, Al2O3, SiO2). They found that CeO2 not only provided lattice oxygen during partial oxidation but also enhanced hydrogen production during steam reduction. Of these composites, the LaFeO3-CeO2 composite oxygen carrier showed optimal performance, with CO selectivity >98%, an H2/CO ratio of 2, and a H2 purity of 95%.

Jiang et al. [68] studied a solar-driven CL-SMR process using perovskite as the oxygen carrier (La1−yCayNi0.9Cu0.1O3). The results showed that the reactivity of the oxygen carrier increased to a certain extent with the increase in Ca content. Among them, La0.1Ca0.9Ni0.9Cu0.1O3 had the best reactivity, regenerability, and anti-coking ability. This stems from the structural differences between perovskite oxides and metal oxides. Unlike the cubic structure of metal oxides, the perovskite framework is supported by metal A, with an octahedral structure, which can enhance stability during the reaction process.

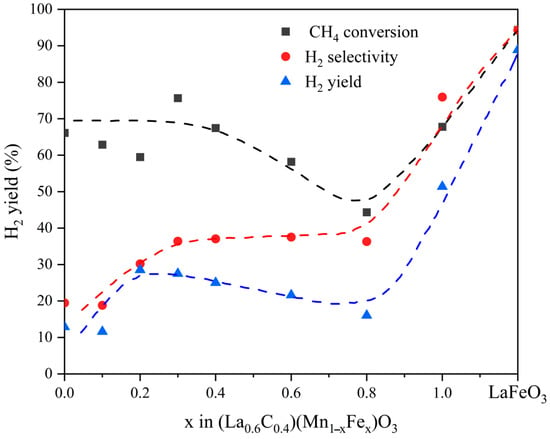

In the work of Antigoni Evdou et al. [69], the performance of perovskite-type oxygen carriers doped with different A/B-sites in the chemical looping hydrogen production process was systematically compared. The research was carried out in two directions: A-site (partially replaced by Ca2+ or Sr2+) and B-site (replaced by Fe). The results show that Ca2+ or Sr2+ doping enhances oxygen migration but reduces H2 selectivity, while Fe replacing Mn improves partial oxidation activity–LaFeO3 was identified as the most promising carrier. As shown in Figure 5, the curves of total CH4 conversion rate, hydrogen production rate (H2), and selectivity varying with Fe content x are presented. A critical comparison of similar perovskite systems reveals that, in Mn-based systems, Cu-doped samples (La0.8MnCu0.2O3) show higher CO selectivity (~100%) than Fe-doped ones (LaMn0.7Fe0.3O3+δ, 90.6%). This is attributed to the more flexible redox pairs of Cu and the adoption of sol–gel synthesis (in contrast to the solid-state method used for the Fe-doped samples). In Fe-based systems, Sr doping (La0.7Sr0.3FeO3) balances activity and stability, while excessive Sr causes lattice distortion.

Figure 5.

Overall CH4 conversion, H2 yield, and selectivity as a function of Fe content (x) [69].

Table 2.

Studies on chemical looping steam methane reforming of perovskite oxygen carriers.

Table 2.

Studies on chemical looping steam methane reforming of perovskite oxygen carriers.

| Oxygen Carrier | Doping Site | Methane Conversion Rate | CO Selectivity | H2/CO Ratio | Yield | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2 | Syngas mmol/g | ||||||

| SrFeO3−δ/01Ni (Sr:Ni = 1:0.001) | A | 38% | — | ~1.8 | 2.66 mmol/g | — | [38] |

| La0.8MnCu0.2O3 | A | ~28% | ~100% | 1.91–2.10 | 2.45 mmol/g | 5.11 | [61] |

| La0.7Sr0.3FeO3 | A | 80% | — | 2 | 2.12 mmol/g (96%) | — | [65] |

| BaSrCo3710/CeO2 | A | — | 90% | ~2 | — | — | [70] |

| Ba0.3Sr0.7CoO3-δ/CeO2 | A | — | 95% | ~2 | (~93%) | — | [71] |

| LaMn0.5Al0.5O3+δ | B | — | 96.4% | 2 | 3.32 mmol/g | 3.68 | [62] |

| LaMn0.7Fe0.3O3+δ | B | — | 90.6% | 2 | ~0.24 mmol/g | — | [52] |

| LaSrFe2-xCoxO6 (x = 0.4–0.6) | B | 70% | ~54% | 2 | 2.89–3.33 mol/g | — | [64] |

| LaFe0.9Ni0.1O3 | B | 90% | — | 2.5 | 3.69 mmol/g | — | [66] |

| LaCo0.6Fe0.4O3 | B | — | 92% | 1.9–2.05 | 2.22 mmol/g (99.3%) | 2.40 | [72] |

| CeO2/La2Ni1.4Co0.6O6 | B | 85% | — | 2 | 33.0 mmol/g (94%) | (95%) | [73] |

| La0.8Sr0.2Mn0.5Co0.5O3+δ | AB | 55.2% | 83.7% | 2 | 2.48 mmol/g | — | [63] |

| LaFeO3-CeO2 | AB | 98% | ~98% | 2 | 0.0374 mmol/g | — | [67] |

| La0.1Ca0.9Ni0.9Cu0.1O3 | AB | 52% | 60% | 2 | 3.08 mmol/g | — | [68] |

| La0.95Ce0.05Ni0.2Fe0.8 | AB | 93.1% | — | 2 | (99.6%) | (94.8%) | [74] |

| La0.95Ce0.05Ni0.5Fe0.5 | AB | 95.7% | — | 2 | (99.5%) | (89.0%) | [74] |

| La0.95Ce0.05Ni0.2Fe0.8O3 | AB | — | — | 2.3 | (67.6%) | — | [75] |

Zhao et al. [74] prepared perovskite La0.95Ce0.05NixFe1−xO3 (x = 0, 0.2, 0.5, 0.8, 1.0) as the oxygen carrier for CL-SMR and studied the activation of methane and steam cracking. The results showed that the addition of Ni significantly promoted the release of lattice oxygen, but excessive Ni would exacerbate carbon deposition. Ni doping does not affect the perovskite structure but results in the transformation of crystal structure, reducing the symmetry of the perovskite lattice and adjusting the migration of lattice oxygen. The doping of Ni apparently enhances the release of lattice oxygen due to the synergistic effects of Ni-Fe, which corresponds with their performance for CH4 partial oxidation. Among them, when the Ni/Fe ratio was 1:4 and 1:1, high syngas selectivity (94.8%, 89.0%), methane conversion rates (93.1% and 95.7%), nearly 100% steam cracking, hydrogen concentrations (higher than 99.6% and 99.5%), and a molar ratio of H2/CO close to the optimal value of 2 were observed.

Wang et al. [73] studied the influence of Ni and Co-doped La2Ni2−xCoxO6 double perovskite composite oxygen carriers in CL-SMR. It was found that the Co doping of Ni and Co has a dual modulating effect on the catalytic performance of the CeO2/La2Ni2−xCoxO6 double perovskite-type oxygen carriers. Among them, the CeO2/La2Ni1.4Co0.6O6 sample showed a good syngas selectivity (95%) at 850 °C and a relatively high methane conversion rate (85%), with a hydrogen purity of 94% in the steam conversion stage and a H2/CO ratio of 2.

Due to the absence of hydroxide adsorption, LaCoO3 exhibits negligible hydrogen production and minimal oxygen transfer from the surface to the lattice. Lee et al. [72] demonstrated that substituting Fe at the B-site in LaCo0.6Fe0.4O3 effectively overcomes this limitation. Iron promotes hydroxide adsorption and decomposition, enhancing hydrogen generation. As the active site for steam splitting, Fe increases its oxidation state and improves oxygen mobility, while reducing lattice oxygen transfer. This leads to insufficient replenishment of surface oxygen vacancies, thereby promoting partial oxidation of methane. Overall, LaCo0.6Fe0.4O3 shows superior hydrogen production and syngas selectivity, making it a suitable oxygen carrier for low-temperature CL-SMR. Under optimal conditions, CO selectivity reached 92%, hydrogen purity was 99.3%, hydrogen yield was 2.22 mmol H2/g, and the H2/CO ratio was maintained at 1.9–2.05, with a carbon deposition rate of <0.8 wt%.

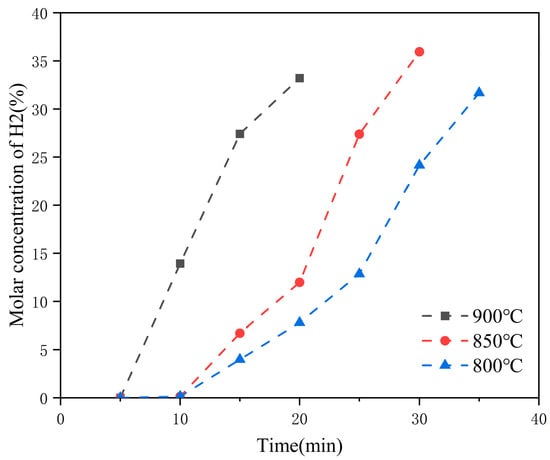

Further improvements in oxygen carrier performance have been achieved through structural and compositional modifications. Farzam Fotovat et al. [76] incorporated kaolin and boehmite alumina into La0.7Sr0.3FeO3, forming KB(x,y)/LSF composites with a pure perovskite structure. These materials exhibit high oxygen adsorption capacity, coke suppression, wear resistance, and thermal stability over repeated cycles. As shown in Figure 6, KB(x,y)/LSF maintained stable H2 production during reduction and, after ten cycles at 900 °C, still produced syngas with a H2/CO ratio of 2–3, a methane conversion of 64%, and a CO selectivity of 87%.

Figure 6.

The cyclic average concentration of H2 in gaseous products in the reduction step, with KB(25,15)/LSF as the oxygen carrier [70].

For Fe-based systems, it is generally believed that Sr doping at the A-site enhances oxygen mobility by generating charge-compensated oxygen vacancies, thereby increasing the partial oxidation activity of methane. Meanwhile, an appropriate amount of Sr can improve cycling stability, but excessive SR can cause lattice distortion and secondary phases, reducing long-term durability. Overall, the anti-sintering stability of the Fe-based system stems from the intrinsic framework of perovskite and the regulation of oxygen vacancies/valence states by moderate A-site doping. However, its renewability depends on appropriate B-site doping and an operating window to avoid deep reduction leading to metal precipitation or carbon deposits that are difficult to oxidize. In many studies on Fe-based systems perovskites, samples synthesized via the sol–gel or Pechini routes show higher oxygen mobility and more stable Fe4+/Fe3+ redox cycles than materials prepared by solid-state methods. This explains why studies using wet-chemistry syntheses often report better coking resistance and cycling stability.

In another approach, Cao et al. [70] studied Ba1−xSrxCoO3-δ/CeO2 on honeycomb ceramics through the impregnation method. The results showed that the introduction of honeycomb ceramics could effectively reduce methane pyrolysis and carbon deposition in the POM stage, with a CO selectivity of about 90% and a H2/CO ratio close to 2. Ding et al. [71] studied the reaction activity and cyclic performance of perovskites of Ba1−xSrxCoO3−δ (x = 0, 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7, 0.9) loaded with CeO2 at different A-site doping ratios in CL-SMR. The results showed that Sr doping increased the yields of syngas and hydrogen, with a H2/CO ratio of the syngas close to 2, CO selectivity of 95%, and a hydrogen selectivity of approximately 93% in partial oxidation stage. Ding et al. [77] developed and tested the performance of the CeO2-loaded BaCoO3−δ oxygen carrier and found that the sample prepared by the sol–gel method was an efficient oxygen carrier for CL-SMR and determined that the conversion of –O–CH3 to –CHO + H2 was the rate-limiting step. Among them, when the BaCoO3−δ/CeO2 oxygen carrier, prepared by the sol–gel method, was at 850 °C, the H2/CO ratio was about 2, the syngas yield was 4.57 mmol/g, and the hydrogen yield was 1.47 mmol/g. Yang et al. [38] studied the influence of low-content Ni or Co-doped SrFeO3−δ (SFO) oxygen carriers in methane chemical looping reforming and found that the doped oxygen carriers made the methane conversion more active, and the synergistic effect caused by the presence of Ni might enhance the activity of the oxygen carriers. Among them, SFO/01Ni (Sr:Ni = 1:0.001) had the highest methane conversion rate (38%), and SFO/01Co (Sr:Co = 1:0.001) had the highest syngas selectivity (93%).

In addition, introducing a small number of precious metals (such as Pd, Pt, Rh, or Ru) into perovskite-type oxides is an effective way to enhance their redox performance, lattice oxygen mobility, and surface reaction kinetics. For instance, Y. Farhang et al. [78] investigated the improvement of the catalytic performance of LaSrCuO4 perovskite in methane combustion and carbon monoxide oxidation reactions by replacing part of the Cu element with Pd and Pt. Pd and PT-doped LaSrCuO4 achieved complete oxidation of CH4 and CO at a relatively low temperature, indicating that precious metals can effectively promote lattice oxygen activation and reactant adsorption. Meanwhile, precious metals can also act as spillover centers, transferring activated H or O species to the surface and lattice of perovskites, enhancing the oxidation and reduction steps [79]. However, the high cost and easy sintering of precious metals still restrict their industrial application. The current research trends are focused on ultra-low loading, single-atom dispersion, and precipitated metal-oxide structures (exsolution), etc., to maintain high activity while reducing the usage of precious metals.

In multi-component systems, the combined influence of A-site charge imbalance and B-site redox coupling leads to the highest reported reactivities but also the largest variation among studies. In these materials, oxygen mobility is governed simultaneously by A-site and B-site redox, making the oxygen-release pathways highly sensitive to synthesis method, calcination temperature, and operating conditions.

In summary, elemental doping or substitution at the A-site and B-site of perovskite materials effectively tunes their performance by enhancing reactivity, regulating oxygen vacancy concentration, and improving anti-coking properties. For instance, Cu doping in LaMn1−xCuxO3+δ improves reducibility and oxygen mobility, while Al doping in LaMn1-xAlxO3+δ boosts CO selectivity and hydrogen yield. As shown in Table 2, Ni and Fe notably enhance methane conversion. In systems like La1−xSrxMn1−γCoγO3+δ, Co doping with Co and Sr increases surface active sites and oxygen vacancy concentration. Replacing A-site La3+ with low-valence cations (e.g., Sr2+, Ca2+, Ba2+) introduces oxygen vacancies, improving lattice oxygen mobility and redox activity. For example, Sr-doped LaFeO3 weakens the Fe-O bond, facilitating oxygen release and uptake, and typically raises methane conversion and hydrogen yield by 10–20%. However, excessive doping causes lattice distortion and secondary phases, reducing cycling stability.

B-site doping with transition metals (e.g., Ni, Co, Mn, Cu) adjusts metal–oxygen bond strength and electronic structure, lowering oxygen vacancy formation energy and promoting lattice oxygen migration and methane activation. Ni and Co introduce reversible redox couples (Ni2+/Ni3+ and Co2+/Co3+), accelerating CH4 cracking, while Mn and Cu facilitate oxygen vacancy formation and reoxidation by CO2, aiding in CO2 separation. An optimal design for CL-SMR oxygen carriers should combine A-site charge compensation (Sr, Ba, Ce) with B-site redox enhancement (Ni, Co, Mn) to balance activity, stability, and coke resistance. This strategy effectively boosts H2 yield, oxygen mobility, and long-term performance, underscoring the value of elemental doping in advancing perovskite-based CL-SMR processes.

4. Conclusions and Outlook

CL-SMR represents an efficient and low-carbon technology for hydrogen production, enabling controllable fuel conversion and significant greenhouse gas reduction. The key to its technological advancement lies in the development of high-performance oxygen carriers. Among various candidates, perovskite-based oxygen carriers emerge as ideal materials due to their distinctive advantages: exceptional lattice oxygen mobility that facilitates methane partial oxidation and syngas generation, coupled with remarkable structural stability, anti-sintering properties, and coke resistance under high-temperature reaction conditions.

The anti-coking performance of perovskite oxygen carriers can be enhanced through two optimization strategies. The first is surface modification—enhancing lattice oxygen mobility by doping with alkali metals, introducing secondary active metals, or regulating the size of active sites, thereby inhibiting coke formation from the source. The second is structural design—adopting a three-dimensionally ordered macroporous (3DOM) structure, which utilizes its characteristics of large specific surface area, low mass transfer resistance, and abundant active sites to accelerate the removal of carbon species and significantly reduce coking risk.

Regarding material synthesis, while refined methods like sol–gel yield high-quality perovskites, they incur substantial costs. Alternatively, the wet impregnation route utilizing inexpensive dopants offers an economically viable pathway. The economic feasibility of CL-SMR is fundamentally governed by the cost and durability of oxygen carriers, though scale-up production still faces challenges in process optimization and waste treatment. Compared with other hydrogen production technologies (SOEC, ATR, and LOHCs), CL-SMR demonstrates superior CO2 management and energy efficiency. With the development of low-cost, scalable, and stable perovskite oxygen carriers, CL-SMR is positioned to achieve highly competitive levelized hydrogen costs compared to CCS-equipped autothermal reforming.

Despite considerable progress in enhancing the redox performance and coking resistance of perovskite oxygen carriers, current research still faces several limitations. First, the development process remains heavily reliant on trial-and-error experimentation, resulting in low efficiency in screening high-performance materials. Second, the high preparation cost of perovskite oxides continues to hinder their large-scale industrial adoption. Third, insufficient understanding of reaction kinetic mechanisms and low levels of process integration have impeded the formation of a systematic technical framework.

Based on the aforementioned limitations, future research should focus on four key directions to advance the industrial application of CL-SMR technology. The recommendations are structured according to their implementation timeline as follows:

- (1)

- Short-term: Optimize research methods by integrating simulation and experimental validation to establish an efficient research and development framework based on “theoretical prediction–experimental verification”, thereby reducing trial-and-error costs and improving the screening efficiency of oxygen carriers.

- (2)

- Medium-term: Deepen the investigation into carbon deposition mechanisms and structure–activity relationships. On one hand, advanced characterization techniques and theoretical calculations should be combined to clarify the types, morphology, and formation kinetics of coke on perovskite oxygen carriers, providing a theoretical basis for precise carbon control. On the other hand, systematic efforts should be made to reveal the intrinsic correlation between the crystal structure of perovskite materials (e.g., A/B-site doping, oxygen vacancy concentration) and their redox activity and anti-coking performance, so as to guide the targeted design of high-performance oxygen carriers.

- (3)

- Long-term: Improve reactor design by optimizing reactor selection and structural parameters (e.g., temperature distribution, gas flow field) according to the performance characteristics of perovskite oxygen carriers, thereby fully leveraging their anti-coking advantages and achieving precise alignment between technical conditions and material properties.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.L.; resources, Z.L., H.Z. and J.F.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.L.; writing—review and editing, Z.L., H.Z. and J.F.; visualization, Z.L.; supervision, J.F.; project administration, Z.L.; funding acquisition, Z.L. and J.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Key Research and Development Program of Shaanxi Province (No. 2024NC-YBXM-246) and the 2024 Innovation and Scientific Research Plan Project of the Education Department of Shaanxi Province (No. 203010712).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 3DOM | Three-dimensionally ordered macroporous |

| AWE | Alkaline water electrolysis |

| AR | Air reactor |

| CCS | Carbon capture and storage |

| CL-SMR | Chemical looping steam methane reforming |

| DRM | Dry reforming of methane |

| FR | Fuel reactor |

| LOHCs | Liquid organic hydrogen carriers |

| oxygen carriers | oxygen carriers |

| POM | Partial oxidation of methane |

| SFO | SrFeO3−δ |

| SMR | Steam methane reforming |

| SOEC | Solid oxide electrolysis cell |

| WGS | Water-gas shift |

References

- Ramezani, R.; Di Felice, L.; Gallucci, F. A review of chemical looping reforming technologies for hydrogen production: Recent advances and future challenges. J. Phys.-Energy 2023, 5, 024010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Lin, Y.; Huang, J.; Ye, T.; Huang, Z.; Huang, H.; Li, S. Competitive Reaction Mechanism Between Biomass Char and Reduced Oxygen Carrier during Chemical Looping Hydrogen Production. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 3256–3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giuliano, A.; Capone, S.; Anatone, M.; Gallucci, K. Chemical Looping Combustion and Gasification: A Review and a Focus on European Research Projects. IEC Res. 2022, 61, 14403–14432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emam, A.S.; Hamdan, M.O.; Abu-Nabah, B.A.; Elnajjar, E. A review on recent trends, challenges, and innovations in alkaline water electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 64, 599–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Hou, H.; Yang, Y.; Ma, G.; Zhan, X.; Yang, H.; Yang, W. MXene-derived anatase-TiO2/rutile-TiO2/In2O3 heterojunctions toward efficient hydrogen evolution. Colloid Surf. A 2022, 652, 129881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impemba, S.; Provinciali, G.; Filippi, J.; Salvatici, C.; Berretti, E.; Caporali, S.; Banchelli, M.; Caporali, M. Engineering the heterojunction between TiO2 and In2O3 for improving the solar-driven hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 63, 896–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diglio, M.; Contento, I.; Impemba, S.; Berretti, E.; Della Sala, P.; Oliva, G.; Naddeo, V.; Caporali, S.; Primo, A.; Talotta, C.; et al. Hydrogen Production from Formic Acid Decomposition Promoted by Gold Nanoparticles Supported on a Porous Polymer Matrix. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 14320–14329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storione, A.; Boscherini, M.; Miccio, F.; Landi, E.; Minelli, M.; Doghieri, F. Improvement of Process Conditions for H2 Production by Chemical Looping Reforming. Energies 2024, 17, 1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, D.; Kang, F.; Qiu, Y.; Cui, D.; Li, M.; Ma, L.; Zhang, S.; Xiao, R. Iron oxides with gadolinium-doped cerium oxides as active supports for chemical looping hydrogen production. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 396, 125153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, K.S.; Son, S.R.; Kim, S.D.; Kang, K.S.; Park, C.S. Hydrogen production from two-step steam methane reforming in a fluidized bed reactor. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2009, 34, 1301–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.L.; Gao, M.L.; Pu, G.; Lu, X.Q.; Gao, J.; Wu, J.L.; Yang, Q.H. High selectivity syngas generation by double perovskite oxygen carriers La2Fe2−xCoxO6 for chemical looping steam methane reforming. Environ. Chem. Eng 2024, 12, 114176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oni, A.O.; Anaya, K.; Giwa, T.; Di Lullo, G.; Kumar, A. Comparative assessment of blue hydrogen from steam methane reforming, autothermal reforming, and natural gas decomposition technologies for natural gas-producing regions. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 254, 115245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.Q.; Xin, Y.; Xing, J.X.; Cao, Y.L.; Sun, F.; Xing, X.L.; Hong, H.; Xu, C.; Jin, H.G. Enhanced oxygen migration in tailored lanthanum-based perovskite for solar-driven dry reforming of methane. Fuel 2024, 363, 130852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscherini, M.; Storione, A.; Minelli, M.; Miccio, F.; Doghieri, F. New Perspectives on Catalytic Hydrogen Production by the Reforming, Partial Oxidation and Decomposition of Methane and Biogas. Energies 2023, 16, 6375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.-L.; Cui, H.-J.; Ge, Q.-S. Will China achieve its 2060 carbon neutral commitment from the provincial perspective? Adv. Clim. Change Res. 2022, 13, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Fang, X.J.; Cui, C.X.; Kang, S.S.; Zheng, A.Q.; Zhao, Z.L. Co-production of syngas and H2 from chemical looping steam reforming of methane over anti-coking CeO2/La0.9Sr0.1Fe1−xNixO3 composite oxides. Fuel 2022, 317, 123455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Song, D.; Li, Y.; Cao, J.; Wei, G.; He, F. High-Quality Syngas Production by Chemical Looping Gasification of Bituminite Based on NiFe2O4 Oxygen Carrier. Energies 2023, 16, 3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papalas, T.; Palamas, E.; Antzaras, A.N.; Lemonidou, A.A. Evaluating bimetallic Ni-Co oxygen carriers for their redox behavior and catalytic activity toward steam methane reforming. Fuel 2024, 359, 130272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Han, H.; Zhu, N.; Che, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xue, Y.; Deng, J.; Wu, C.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y.; et al. Chemical Looping Combustion for Coupling with Efficient CO2 Capture and Utilization: Stable Oxygen Carriers and Carbon Cycle. IEC Res. 2025, 64, 1933–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.Y.; Sukma, M.S.; Scott, S.A. The exploration of NiO/Ca2Fe2O5/CaO in chemical looping methane conversion for syngas and H2 production. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 465, 142779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Chen, S.; Duan, L.; Xiang, W. Carbon Dioxide Capture and Hydrogen Production with a Chemical Looping Concept: A Review on Oxygen Carrier and Reactor. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 16245–16266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Xu, S.; Song, Y.; Shan, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, G. Biomass steam gasification for hydrogen-rich gas production in a decoupled dual loop gasification system. Fuel Process. Technol. 2017, 165, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, D.; Cui, D.; Lu, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, S.; Xiao, R. A mixed spinel oxygen carrier with both high reduction degree and redox stability for chemical looping H2 production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 1444–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhu, X.; Wei, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Yang, Z.; Li, K. Evaluation of Fe substitution in perovskite LaMnO3 for the production of high purity syngas and hydrogen. J. Power Sources 2020, 449, 227505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miccio, F.; Mazzocchi, M.; Boscherini, M.; Storione, A.; Minelli, M.; Doghieri, F. The Trade-Off between Combustion and Partial Oxidation during Chemical Looping Conversion of Methane. Energies 2024, 17, 2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, M.; Khan, M.N.; Zaabout, A.; Cloete, S.; Amini, S. Review of pressurized chemical looping processes for power generation and chemical production with integrated CO2 capture. Fuel Process. Technol. 2021, 214, 106684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, M.; Soltanieh, M.; Heydarinasab, A.; Maddah, B. Synthesis of a new self-supported Mgy(CuxNi0.6−xMn0.4)1−yFe2O4 oxygen carrier for chemical looping steam methane reforming process. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 19397–19420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Wang, C.; Han, Y.J.; Wang, X. Recent Advances of Oxygen Carriers for Chemical Looping Reforming of Methane. ChemCatChem 2021, 13, 1615–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysowski, R.; Ksepko, E.; Ra, H. Increased stability of CuFe2O4 oxygen carriers in biomass combustion by Mg doping. Waste Manag. 2025, 199, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Lin, J. Layered organic–inorganic hybrid perovskites: Structure, optical properties, film preparation, patterning and templating engineering. CrystEngComm 2010, 12, 2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Li, K.; Neal, L.; Li, F. Perovskites as Geo-inspired Oxygen Storage Materials for Chemical Looping and Three-Way Catalysis: A Perspective. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 8213–8236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assirey, E.A.R. Perovskite synthesis, properties and their related biochemical and industrial application. Saudi Pharm. J. 2019, 27, 817–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, S.; Daoud, W.A. Recent progress in organic–inorganic halide perovskite solar cells: Mechanisms and material design. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 8992–9010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, L.K.; Juarez-Perez, E.J.; Qi, Y. Progress on Novel Perovskite Materials and Solar Cells with Mixed Cations and Halide Anions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 30197–30246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawa, T.; Sajjadi, B. Exploring the potential of perovskite structures for chemical looping technology: A state-of-the-art review. Fuel Process. Technol. 2024, 253, 108022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, A.; de Leeuwe, C.; Spallina, V. Bi-metallic Ni-Fe LSF perovskite for chemical looping hydrogen application. Powder Technol. 2024, 436, 119510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, I.; Liu, L.; Yu, S.; Lai, N.; Gao, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, W. Highly sintering-resistant iron oxide with a hetero-oxide shell for chemical looping water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 57, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhao, Z.; Cui, C.; Zhang, J.; Wei, J. Effect of Nickel and Cobalt Doping on the Redox Performance of SrFeO3−δ toward Chemical Looping Dry Reforming of Methane. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 12045–12057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turap, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, S.; Wang, W. High purity hydrogen production via coupling CO2 reforming of biomass-derived gas and chemical looping water splitting. Appl. Energy 2023, 331, 120447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Cheng, B.; Yang, H.; Cui, X.; Zhao, M. Chemical looping partial oxidation (CLPO) of toluene on LaFeO3 perovskites for tunable syngas production. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 451, 138968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Nam, H.; Kim, H.; Hwang, B.; Baek, J.I.; Ryu, H.J. Experimental screening of oxygen carrier for a pressurized chemical looping combustion. Fuel Process. Technol. 2021, 218, 106860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, Z.; Lu, C.; Li, D.; Li, Z.; Gao, J.; Wei, J.; Li, K. Enhanced performance of LaFeO3 oxygen carriers by NiO for chemical looping partial oxidation of methane. Fuel Process. Technol. 2022, 236, 107396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zheng, Z.; Yi, F.; Liu, W. Modified CeO2 as active support for iron oxides to enhance chemical looping hydrogen generation performance. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 32995–33006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.H.; Lee, K.-T. Development of MgFe2O4 as an oxygen carrier material for chemical looping hydrogen production. J. Ceram. Process. Res. 2020, 21, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papalas, T.; Antzaras, A.N.; Lemonidou, A.A. Unravelling the role of Co in mixed Ni-Co oxygen carriers/catalysts for H2 production via sorption enhanced steam methane reforming coupled with chemical looping. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2024, 347, 123777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Yang, Q.; Song, Z.; Chang, W.; Huang, C.; Zhu, Y.; Ma, X.; Wang, X. Improving the carbon resistance of iron-based oxygen carrier for hydrogen production via chemical looping steam methane reforming: A review. Fuel 2023, 351, 128864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Long, T.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Fan, M.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, H.; Lin, Y.; Huang, Z.; et al. Micro-structure change and crystal-structure modulated of oxygen carriers for chemical looping: Controlling local chemical environment of lattice oxygen. Fuel 2024, 364, 131087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yan, R.; Lee, D.H.; Liang, D.T.; Zheng, Y.; Zhao, H.; Zheng, C. Thermodynamic investigation of carbon deposition and sulfur evolution in chemical looping combustion with syngas. Energy Fuels 2008, 22, 1012–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donat, F.; Kierzkowska, A.; Muller, C.R. Chemical Looping Partial Oxidation of Methane: Reducing Carbon Deposition through Alloying. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 9780–9784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, K.; Wang, H.; Jiang, L.; Yuan, K.; Zheng, Y. Modification of LaFe1−xCoxO3 oxygen carrier by Silicalite-1 for chemical looping coupled with the reduction of CO2. J. CO2 Util. 2022, 63, 102124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalbandian, L.; Evdou, A.; Zaspalis, V. La1−xSrxMyFe1−yO3−δ perovskites as oxygen-carrier materials for chemical-looping reforming. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 6657–6670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, B.; Shen, L. Perovskite-type LaMn1−xBxO3+δ (B = Fe, CO and Ni) as oxygen carriers for chemical looping steam methane reforming. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 422, 128751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, K.; Zheng, Y.; Li, K.; Yang, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Zhu, X.; Wei, Y.; Wang, Y. Enhanced Resistance to Carbon Deposition over LaxCe1−xFexNi1−xO3 Oxygen Carrier for Chemical Looping Reforming. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 15867–15878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Wang, S.; Sun, R.; Jiang, S.; Shen, L. A Ce-Fe Oxygen Carrier with a Core-Shell Structure for Chemical Looping Steam Methane Reforming. IEC Res. 2020, 59, 9775–9786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garai, M.H.S.; Khosravi-Nikou, M.R.; Shariati, A. Chemical Looping Steam Methane Reforming via Ni-ferrite Supported on Cerium and Zirconium Oxides. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2020, 43, 1813–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Li, H.; Chen, S.; Xiang, W. Enhanced Fe2O3/Al2O3 Oxygen Carriers for Chemical Looping Steam Reforming of Methane with Different Mg Ratios. IEC Res. 2022, 61, 1022–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, J.; Wongsakulphasatch, S.; Kokoo, R.; Noppakun, N.; Prapainainar, C.; Aziz, M.A.A.; Assabumrungrat, S. Optimisation of a sorption-enhanced chemical looping steam methane reforming process. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2021, 173, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Miao, Z.; Wu, J.; Jiang, E. Nickel-iron modified natural ore oxygen carriers for chemical looping steam methane reforming to produce hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 39700–39718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins-Martinez, V.H.; Cazares-Marroquin, J.F.; Salinas-Gutierrez, J.M.; Pantoja-Espinoza, J.C.; Lopez-Ortiz, A.; Melendez-Zaragoza, M.J. The thermodynamic evaluation and process simulation of the chemical looping steam methane reforming of mixed iron oxides. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 684–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, S.; Chen, H.; Zeng, D.; Xiao, R. Ni-Promoted Fe2O3/Al2O3 for Enhanced Hydrogen Production via Chemical Looping Methane Reforming. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 12788–12795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Zhu, X.; Wei, Y.; Li, K. Enhanced activity of La1−xMnCuxO3 perovskite oxides for chemical looping steam methane reforming. Fuel Process. Technol. 2021, 215, 106744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, B.; Shen, L. Chemical looping steam methane reforming using Al doped LaMnO3+delta perovskites as oxygen carriers. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 33375–33387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Shen, L.; Wang, S.; Wang, B.; Shen, C. Double adjustment of Co and Sr in LaMnO3+delta perovskite oxygen carriers for chemical looping steam methane reforming. App. Catal. B Environ. 2022, 301, 120861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Chen, J.; Li, H.; Zheng, A.; He, F. Effects of Co-substitution on the reactivity of double perovskite oxides LaSrFe2−xCoxO6 for the chemical-looping steam methane reforming. J. Energy Inst. 2018, 92, 594–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Chen, J.; Liu, S.; Huang, Z.; Wei, G.; Wang, G.; Cao, Y.; Zhao, K. La1-xSrxFeO3 perovskite-type oxides for chemical-looping steam methane reforming: Identification of the surface elements and redox cyclic performance. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 10265–10276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zhao, K.; He, F.; Li, H. The structure-reactivity relationships of using three-dimensionally ordered macroporous LaFe1−xNixO3 perovskites for chemical-looping steam methane reforming. J. Energy Inst. 2019, 92, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.; Luo, C.; Wu, F.; Zhang, L.; Li, X. Screening loaded perovskite oxygen carriers for chemical looping steam methane reforming. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Cao, Y.; Hong, H.; Jin, H. Solar hydrogen production via perovskite-based chemical-looping steam methane reforming. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 187, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evdou, A.; Zaspalis, V. Comparative Evaluation of Various ABO3 Perovskites (A = La, Ca, Sr; B = Mn, Fe) as Oxygen Carrier Materials in Chemical Looping Hydrogen Production. Hydrogen 2025, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.; Ding, H.; Luo, C.; Wu, F.; Li, X.; Zhang, L. Development of a cordierite monolith reactor coated with CeO2-supported BaSrCo-based perovskite for chemical looping steam methane reforming. Fuel Process. Technol. 2021, 220, 106889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Luo, C.; Li, X.; Cao, D.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, L. Development of BaSrCo-based perovskite for chemical-looping steam methane reforming: A study on synergistic effects of A-site elements and CeO2 support. Fuel 2019, 253, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Lim, H.S.; Kim, Y.; Lee, J.W. Enhancement of highly-concentrated hydrogen productivity in chemical looping steam methane reforming using Fe-substituted LaCoO3. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 207, 112507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Chen, S.; Chen, S.; Du, J.; Duan, L.; Xiang, W. Double adjustment of Ni and Co in CeO2/La2Ni2−xCoxO6 double perovskite type oxygen carriers for chemical looping steam methane reforming. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 465, 143041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Zhang, R.; Gao, Y.; Lin, Y.; Liu, A.; Wang, X.; Zheng, A.; Huang, Z.; Zhao, Z. High syngas selectivity and near pure hydrogen production in perovskite oxygen carriers for chemical looping steam methane reforming. Fuel Process. Technol. 2022, 236, 107398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyed, S.Z.; Vaidya, P.D. Chemical Looping-Steam Reforming of Biogas and Methane over Lanthanum-Based Perovskite for Improved Production of Syngas and Hydrogen. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 19082–19091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotovat, F.; Beyzaei, M.; Ebrahimi, H.; Mohebolkhames, E. Synthesis, Characterization, and Attrition Resistance of Kaolin and Boehmite Alumina-Reinforced La0.7Sr0.3FeO3 Perovskite Catalysts for Chemical Looping Partial Oxidation of Methane. Catalysts 2024, 14, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Jin, Y.; Hawkins, S.C.; Zhang, L.; Luo, C. Development and performance of CeO2 supported BaCoO3-delta perovskite for chemical looping steam methane reforming. Fuel Process. Technol. 2023, 239, 107546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhang, Y.; Taheri-Nassaj, E.; Rezaei, M. Enhanced methane combustion and CO oxidation with Pd and Pt substitution LaSrCuO4 perovskites. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 36, 106891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shun, K.; Mori, K.; Masuda, S.; Hashimoto, N.; Hinuma, Y.; Kobayashi, H.; Yamashita, H. Revealing hydrogen spillover pathways in reducible metal oxides. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 8137–8147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).