1. Introduction

Agriculture is the foundation of our survival and is crucial to the sustainability of our planet and environmental development. Climate change, frequent extreme weather events, and regional conflicts have exacerbated the global food crisis [

1,

2]. Furthermore, global food consumption is projected to grow at an annual rate of 1.2% [

3], underscoring the urgency of agricultural development. However, every stage of the agricultural supply chain consumes significant energy—from direct energy use in lighting, irrigation, transportation, and heating/cooling to indirect energy use in chemical and fertilizer production [

4,

5]. Yet rural areas primarily rely on fossil fuels like coal and natural gas [

6]. To reduce greenhouse gas emissions and dependence on non-renewable energy, promoting sustainable agricultural development through energy-efficient technologies and renewable energy is crucial for environmental protection, food security, economic vitality, climate change adaptation, and social development. However, agricultural production often occurs in remote areas with weak infrastructure. Large-scale energy transportation is inefficient and costly, making it difficult to guarantee a reliable electricity supply for local farmers. Therefore, ensuring energy availability throughout the agricultural supply chain and exploring pathways for transforming rural power systems toward renewable energy dominance are critical.

Sustainable development is a global issue that encourages humanity to meet the needs of present generations while safeguarding the Earth’s resources for future generations. It has garnered extensive attention and research across all sectors. This paper employs a questionnaire survey combined with quantitative statistical methods using PQstat 1.6.6 software to assess the younger generation in Poland’s understanding of human security within sustainable development. The findings indicate that this group demonstrates a solid grasp of sustainable development and closely integrates it with environmental and security concerns [

7]. Limited research on sustainable energy in agriculture has hindered the widespread implementation of sustainable energy solutions for agricultural challenges [

8]. Few studies have addressed agricultural sustainability issues to further advance development and ensure agro-energy security. Martí et al. emphasize energy security as central to sustainable development goals, revealing how national economic and political contexts influence energy security, energy equity, and environmental sustainability. Their findings provide empirical evidence for formulating policies that synergistically advance the transformation of agro-energy systems [

9]. Selvan et al. underscore the importance of agroforestry and resource recycling in enhancing food security and reducing environmental impacts, offering innovative pathways to achieve SDGs that directly address global food shortages and ecological degradation [

10]. Raihan et al. empirically demonstrate that economic growth and agricultural land expansion significantly increase CO

2 emissions, while renewable energy use effectively reduces emissions, highlighting its critical role in promoting energy security and climate-smart agriculture [

11]. Rial identifies integrated biorefinery technologies for agricultural waste resources and sustainable land-use planning as key pathways to balance energy demands with agro-ecological security, emphasizing biofuels’ importance for agricultural sustainability and energy security [

12]. Rather et al. argue that bioenergy serves as a key technology for addressing climate change and achieving environmental sustainability, particularly stressing its importance in enhancing energy security by reducing reliance on fossil fuels through the utilization of renewable resources like agricultural residues [

13]. Kumar et al. review the pivotal role of renewable energy technologies in achieving sustainable development and clean energy goals, highlighting the significance of agriculture-related energy sources such as biomass in improving energy security and reducing greenhouse gas emissions [

14]. Gorjian et al. analyze the pivotal role of renewable energy technologies in ensuring food security and advancing sustainable agriculture, effectively reducing the agricultural sector’s reliance on fossil fuels [

15]. Cergibozan empirically examines the differential impacts of various renewable energy sources on energy security risks, finding that wind and hydropower significantly mitigate risks while solar power does not, underscoring the need to align energy security policies with national resource endowments [

16]. Bathaei underscores the importance of renewable energy in enhancing agro-energy security, reducing fossil fuel dependence, and safeguarding food supply. They further advocate for integrating renewable energy sources like solar and biomass into the agricultural sector to address climate change and achieve sustainable development [

17].

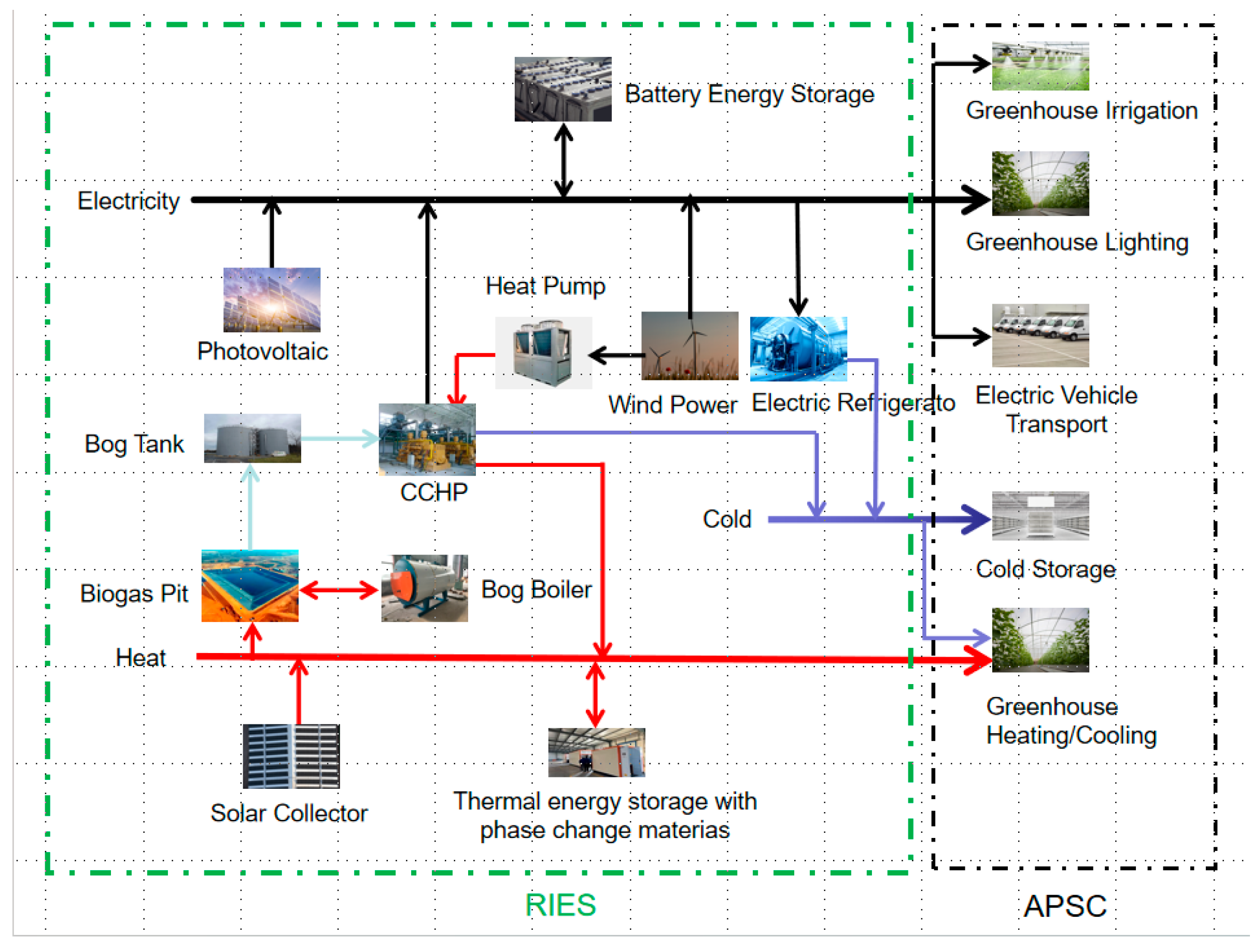

The Rural Integrated Energy System (RIES) [

18], primarily based on renewable energy, is a system that organically integrates multiple forms of rural energy to achieve efficient energy production, distribution, conversion, and utilization. The APSC [

19] encompasses the entire process from production to consumption of agricultural products, aiming to ensure that agricultural products flow from producers to consumers in an efficient, safe, and low-cost manner. Regarding rural integrated energy systems, most studies focus on their optimized operation. Xu et al. [

20] considered the storage issue in rural energy operations to address the problem of insufficient utilization. Ali et al. [

21] conducted an in-depth analysis of the techno-economic feasibility of energy systems integrating photovoltaics and storage technologies, indicating that such systems can effectively meet the electricity supply needs of rural areas. Reference [

22] designed an agricultural microgrid system that integrates wind, solar, and storage to simultaneously meet the power and water needs of rural residents. Li Min et al. [

23], focusing on rural diversified industries such as animal husbandry, planting, and agricultural by-product processing, constructed a rural integrated energy framework. Li et al. [

24] proposed a two-stage robust optimization model for capacity configuration of biogas-solar-wind integrated energy systems suitable for rural areas. Ai Ping et al. [

25] put forward an optimization model for wind, solar, and biomass complementary renewable energy combined heat and power systems, using heat-electricity coverage and biomass utilization rate as evaluation indicators. Wang Yongli et al. [

26] proposed a rural electric-thermal integrated energy system based on bio-solar coupling utilization, considering multi-objective optimization for economic, environmental, and energy consumption factors. Yang et al. [

27] introduced biogas tanks and livestock farms into rural integrated energy systems and performed distributed robust optimization to achieve resource-efficient utilization. Gao Jianwei et al. [

28] took the wind-solar-waste-biogas-storage joint system in agricultural parks as the research object, constructing a low-carbon optimization operation model for agricultural integrated energy systems based on multi-scenario confidence gap decision theory. Wang Ruiqi et al. [

29] considered the unique biogas fermentation power model and thermal load characteristics of rural areas, and built a robust optimization model for rural integrated energy systems featuring integrated photovoltaic hydrogen production, biogas fermentation energy storage, etc. However, the above studies mainly focus on the development and supply reliability of rural integrated energy systems with biogas and biomass resource characteristics, but do not sufficiently pay attention to the special demand loads in rural areas, especially the energy consumption in agricultural crop production and operations.

As a critical component of agricultural production, greenhouse cultivation consumes substantial energy to regulate internal parameters and shorten growth cycles. Currently, few studies focus on energy balance within greenhouses. Goo et al. [

30] employed a generic design algorithm to explore dynamic energy consumption predictions for crop growth processes across different greenhouse structures, while also conducting in-depth studies on multiple cooling models. Dorji et al. [

31] designed solar water heating systems for resource-constrained regions to regulate greenhouse temperature and humidity. Van et al. [

32] developed a novel greenhouse management system utilizing dynamic optimization tools to obtain greenhouse energy flow trajectories, achieving year-round minimization of total external energy consumption. In the field of artificial plant lighting cultivation, Cai et al. [

33] proposed energy-saving technologies including precision ventilation, spectral regulation, and artificial intelligence-based intelligent control. Li et al. [

34] examined thermal and light regulation strategies for greenhouse microenvironments from an energy-saving, environmentally friendly, and low-carbon emissions perspective, emphasizing the advantages of active cooling technologies. These studies reveal the benefits of applying diverse innovative technologies in greenhouse energy consumption management.

A limited number of studies have focused on the overall optimal operation of rural energy systems and greenhouses. Tan et al. [

35] proposed a robust energy management approach for the coordinated operation of rural energy systems and greenhouses. By accounting for the uncertainty in renewable energy output, this method enhances the robustness of energy utilization during greenhouse cultivation while reducing operational costs. Liu et al. [

36] addressed issues such as complex greenhouse structures, numerous equipment, and high energy consumption by proposing a solar thermal regulation system solution. Jin et al. [

37] advocated for the synergistic development of new energy vehicles and electric agricultural machinery, utilizing mobile power supply to meet flexible electricity demands in agricultural production. Simultaneously, batteries from electric agricultural machinery can serve as distributed energy storage devices. Jiang et al. [

38] proposed a negative carbon planning approach for integrated energy systems in modern agricultural facilities, modeling “zero-carbon” benefits from biomass energy in agricultural production activities. Liu et al. [

39] proposed a rooftop agro-photovoltaic complementary model, exploring synergies between rooftop agriculture and photovoltaic power generation. Research revealed that this model not only enhances crop yields but also significantly increases annual electricity generation, demonstrating substantial carbon reduction potential. Xie et al. [

40] implemented an integrated coupling management strategy for energy production, cold storage management, and cold chain transportation systems targeting fresh produce requiring low-temperature storage within green industrial parks. Zhang et al. [

41] investigated synergies between solar technology and air-source heat pumps, ground-source heat pumps, and thermal storage facilities to enable cross-seasonal energy utilization for greenhouse heating and cooling. While Liu et al. [

42] considered renewable energy applications across agricultural supply chain segments, they did not address optimizing energy scheduling to ensure crop yields while achieving sustainable agricultural energy use. The aforementioned studies primarily explore the application of renewable energy (primarily solar) in agriculture. However, renewable energy sources such as solar and wind exhibit high volatility, posing challenges in enhancing the reliability of agricultural energy supply and the energy security capacity across all segments of the agricultural supply chain [

43]. Simultaneously, crop growth exhibits dynamic characteristics, creating a mismatch between the temporal scales of growth stages and energy supply.

Regarding dynamic crop growth, few studies have examined the relationship between crop growth and yield. Existing research predominantly employs estimated indoor climate data in crop growth models, failing to adequately account for the dynamic growth stages of greenhouse crops and the feedback effects of crop growth on energy consumption. Talbot et al. [

44] integrated a dynamic crop model into a greenhouse climate model to calculate energy efficiency and crop yield. Golzar et al. [

45] proposed a comprehensive energy-yield model and crop growth model based on dynamic energy consumption and material balance. Su et al. [

46] suggested dividing the production cycle into several crop development stages according to greenhouse climate conditions at different time scales. Xie et al. [

47] constructed a yield estimation model combining remote sensing data and crop physiological indicators, while precisely capturing soil moisture dynamics and carbon cycling processes. Yang et al. [

48] analyzed water energy consumption per unit crop yield from the perspective of agricultural energy-water inputs and crop outputs to evaluate crop production efficiency. Liu et al. [

49] constructed a coupled model of agricultural energy demand and agricultural park power systems, developing an accurate energy consumption model for dynamic crop growth processes to analyze energy patterns and abnormal load characteristics during specific growth stages.

Based on the above analysis, there are currently the following shortcomings in research on the application of rural energy to various links of the APSC:

- (1)

Currently, within the research fields of sustainable development and human security, the synergies and conflicts between energy and agriculture have not received sufficient attention. Although a few studies [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17] have highlighted that sustainable agricultural transformation requires systematic consideration of the energy dimension and the utilization of agricultural resource waste—particularly through renewable energy supporting the development of new power systems—comprehensive sustainability assessments remain weak throughout the entire process of energy system optimization and agricultural supply chains. Research must further emphasize systematic exploration of sustainability to provide robust safeguards for human security.

- (2)

There is a lack of consideration for agricultural loads with industry-specific characteristics in the integrated agricultural energy system, especially in research on greenhouses. Most studies focus on operational models, environment, and yield. For instance, the research in paper [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19] takes agricultural load as a fixed parameter and inputs it into the operation of a rural integrated energy system that includes biogas/combined heat and power. Since greenhouses are high-energy-consumption systems with flexible load demands, their energy consumption needs to be accurately estimated and integrated into the optimized management of rural energy systems.

- (3)

Since crop growth in greenhouses is a dynamic process, the growth process in turn affects energy consumption. Therefore, the dynamic growth of crops requires special attention. Most existing research, such as [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34], mainly analyzes the energy balance in greenhouses and simplifies crop energy consumption into a single process, which does not align with actual scenarios and leads to inaccurate energy consumption estimates.

- (4)

In addition, the timescale of crop growth stages does not coincide with the timescale of storage, transportation, and energy scheduling, which poses significant challenges for the synergistic coupling of the two heterogeneous systems and further affects multi-energy flows. The aforementioned studies, such as [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49], that consider the dynamic growth phase as related to energy focus on yield and energy balance processes, but further attention is needed on the process of timescale unification.

- (5)

There is a lack of integration between the APSC and the operation of integrated agricultural energy systems. Due to the above-mentioned shortcomings in research on links such as greenhouses, energy consumption estimates are inaccurate, which further affects energy scheduling strategies. Studies such as [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43] mainly focus on energy consumption during the growth phase of agricultural products, but storage and transportation also consume a large amount of energy and greatly affect energy regulation strategies. Therefore, it is necessary to comprehensively consider the matching between each link of the APSC and agricultural energy, and select appropriate energy optimization management methods to ensure a reliable energy supply for the product supply chain.

Literature comparison.

| Ref | Research Content | Method | Biogas/RIES | Crop Grow | Time-Scale | APSC | RIES-APSC | Energy Management |

| [9] | Address security in energy applications and agricultural issues | Cluster analysis and contingency tables | | | | | | ✔ |

| [11] | Dynamic Ordinary Least Squares | | | | ✔ | | ✔ |

| [12] | Research on Technological Innovation | ✔ | | | | | ✔ |

| [13] | Life Cycle Assessment | ✔ | | | | | ✔ |

| [16] | Generation panel data techniques | | | | | | ✔ |

| [17] | SALSA-PRISMA | | | | | | ✔ |

| [20] | The operation of a rural integrated energy system, including biogas/combined heat and power | Day-ahead optimal dispatch model | ✔ | | | | | ✔ |

| [21] | HOMER PRO software simulation | ✔ | | | | | ✔ |

| [23] | Mixed integer linear programming | ✔ | | | | | ✔ |

| [24] | Two-stage robust optimization | ✔ | | | | | ✔ |

| [25] | HOMER Pro simulation system | ✔ | | | | | ✔ |

| [26] | Multi-objective optimization | ✔ | | | | | ✔ |

| [27] | Distributed robust optimization | ✔ | | | | | ✔ |

| [28] | Information gap decision theory | ✔ | | | | | ✔ |

| [29] | Robust optimization | | | | | | |

| [30] | The balance of energy consumption in greenhouses | EnergyPlus simulation | | ✔ | | | | ✔ |

| [31] | TRNSYS simulation tool | | ✔ | | | | |

| [32] | Optimal control | | ✔ | | | | ✔ |

| [33] | / | | | | | | ✔ |

| [34] | / | | ✔ | | | | ✔ |

| [35] | Energy consumption of agricultural products and energy optimization | Robust energy management method | ✔ | ✔ | | | | ✔ |

| [36] | / | ✔ | ✔ | | | | ✔ |

| [37] | / | | ✔ | | | | ✔ |

| [38] | Two-stage distributionally robust model | ✔ | ✔ | | | | ✔ |

| [38] | Deep learning | ✔ | ✔ | | | | ✔ |

| [40] | Two-stage multi-objective optimization model | ✔ | ✔ | | ✔ | | ✔ |

| [41] | TRNSYS software simulation | ✔ | ✔ | | | | ✔ |

| [42] | Optimization Theory | | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| [43] | / | | | | | ✔ | ✔ |

| [44] | Consider the research related to dynamic growth stages and energy | Crop Growth Model-Energy Balance Model | | | | | | |

| [45] | Integrated Energy Output Model | | ✔ | | | | ✔ |

| [46] | Multi-level hierarchical optimal framework | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | | | ✔ |

| [47] | Machine learning | | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | | |

| [48] | / | | ✔ | ✔ | | | ✔ |

| [49] | Mixed-integer linear programming | ✔ | ✔ | | ✔ | ✔ | |

| This paper | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

Based on this, this paper proposes the RIES-APSC collaborative robust operation framework [

50], studying the energy scheduling problem of supply chain reliable operation under the conditions of heterogeneous system coupling and uncertain environment. Through the collaborative operation of the RIES-APSC system, each link of the APSC is coupled with energy on different time scales, addressing the insufficient consideration of loads in traditional greenhouse models. During the dynamic growth process, crop growth is treated as a flexible load to supplement the instability of new rural power systems in coping with fluctuations, and to enhance the consumption of renewable energy locally.

The main innovative points are as follows:

The collaborative operation framework integrates APSC and RIES to achieve multi-energy flow coupling and dynamic optimization between heterogeneous systems based on energy consumption. On the RIES side, a cross-time energy scheduling mechanism is established based on renewable energy and biogas technology storage systems [

51]. On the APSC side, an energy consumption-yield prediction model based on dynamic crop growth monitoring [

52] is developed, implementing cold storage temperature optimization strategies. Path optimization algorithms with time window constraints [

53,

54] are applied to integrate novel transport vehicles [

55], thereby reducing transportation energy consumption.

Through the multi-linkage integrated energy consumption model of the APSC, achieve time-scale coupling and energy consumption integration for the collaborative operation of heterogeneous systems. By leveraging iterative optimization of daily dynamic growth and hourly energy demand forecasts, complete full-cycle energy consumption modeling and yield prediction for crop growth. Employ standardized energy conversion functions to describe energy consumption characteristics across growth, storage, and transportation phases.

Employ a two-stage robust optimization model with a nested column constraint generation algorithm [

56] to address the trade-off between economic efficiency and robustness in coordinated energy scheduling for farmland irrigation-agricultural production systems. The first stage constructs a baseline optimization model targeting minimized energy supply costs. The second stage incorporates multi-scenario uncertainties—including resource fluctuations, demand variations, and environmental disturbances in agricultural production—to establish robust constraints that ensure supply chain resilience while optimizing overall operational costs.

Naming table.

| A Index and Superscript | B Parameter |

| T/t | index of scheduling period/specific time period | ηwp | efficiency of wind power generation (15%) |

| ρ | leaf density | ηpv | efficiency of photovoltaic power generation (30%) |

| βN | slope of the node development curve (0.169) | ηsc | thermal efficiency of the collector (40%) |

| N0 | initial number of nodes (2.4) | / | power generation efficiency (35%) and heating efficiency (50%) of CHP |

| Nb | nodes number when the LAI increases (8) | ηbgb | heating power of the biogas boiler |

| Nm | maximum node growth rate (0.025) | ηhp | heating coefficient of the HP (3.0) |

| Nff | nodes number that start fruiting (16) | | optimal temperatures for crops day/night |

| Kf | fruit ripening rate (0.58) | | outdoor ambient temperature |

| light intensity conversion coefficient lamps | / | energy storage (92%)/release efficiency (97%) of the ES |

| GRnet | growth rate of net photosynthesis (25%) | | actual/optimal fermentation temperature of the biogas digester |

| Cair | the concentration of CO2 in the greenhouse (1000 ppm) | Pwp | output power of WP |

| ρair | density of air (1.225) | Ppv | output power of PV |

| Icon | the amount of water used for irrigation | Pes | output power of ES |

| Alamp | area of sodium lamps | Qsc | output power of SC |

| APV | swept area of the blade | Plamp | power of the sodium lamp light |

| Asun | effective area of the collector | Pelectric | power consumed by the cold storage |

| Apv | area of the PV array | Php | electrical power of the HP |

| G | total radiation intensity of solar radiation | Pgrid | output power of electricity purchased by the power grid |

| Tcell | reference battery temperature | Pes | operating power of the ES |

| Tref | the battery temperature | Pvechicle | the operating power of the vehicle |

| Qd,in | daily crop yield. | | lower limit of battery energy storage capacity |

| Qd,store | storage capacity of the cold storage | | thermal power for supplying biogas |

| Qd,need | market demand | | the biogas production rate |

| Qd,out | volume of electric vehicles transported | qbio.chr/dis | biogas production or consumption |

| Vbs | biogas storage capacity | Hbio: | the calorific value of biogas |

| σes | self-discharge rate of batteries (0.5%) | Qcov,in | heating released to the outside |

| C Decision Variable | Qc | heating/cooling energy of the greenhouse |

| electric/thermal power output of CHP units | Qlat | latent heat energy of ventilation in greenhouses and transpiration of plants |

| / | electrical/thermal power generated by the heat pump | Eheat | heat energy supplied to the greenhouse |

| charging/discharging the power of the battery | Elamp | lighting energy consumption |

| the power of electricity purchased/sold to the grid | Estorge | cold storage energy consumption |

| // | the remaining energy of ES/HS/BS | Qin | total heat entering the cold storage |

| SOC(t) | the state of charge of the ES | Qout | heat removed from the refrigerant |

| start and stop of heating equipment | Qgoods | total heat brought in by crops |

| t | start and stop of refrigeration equipment | Qsolar | solar radiation heat transmitted |

| start and stop of sodium lamp irradiation | Eair | controlling humidity energy consumption |

| the start and stop of irrigation | Evehicle | the total energy consumption for transporting goods |

| energy storage charging | ψpv | the unit power generation cost of PV |

| energy storage discharge | ψwp | the unit power generation cost of WP |

| vehicle transportation speed | ψess | the unit operating cost of ESS |

| vehicle transportation distance | ψchr,dis | the operating cost per unit of energy storage charge and discharge |

5. Energy Optimization Scheduling Based on RIES-APSC Cooperative Operation

The collaborative operation of energy optimization scheduling mainly considers operational economy and reliability. Reliability is to ensure that APSC can operate stably. Operational economy is considered to minimize the collaborative operation cost of RIES-APSC, including the operational cost of providing a suitable greenhouse microclimate environment, storage, transportation, and the energy supply cost for support. The optimized decision variables are the start-stop of energy-consuming equipment for maintaining the indoor environment, the cold supply equipment, and the time and speed of vehicle transportation.

5.1. A Two-Stage Robust Optimization Model for Collaborative Operation

The RIES-APSC collaborative operation framework is a system integrating multi-energy supply with multi-energy load management, involving energy consumption across multiple scenarios and temporal dimensions. To achieve optimal utilization of RIES-APSC, uncertainties across all phases must be comprehensively considered [

70], alongside the implementation of real-time scheduling and operational strategies. This study proposes the TSRO model, constructing an optimization scheduling model that minimizes total operating costs under uncertain external climatic conditions. Robust optimization models are commonly employed for energy optimization problems, yet robust analysis remains relatively scarce in agricultural supply chain research. This study’s robustness analysis accounts not only for uncertainties affecting energy production processes but also encompasses factors influencing crop growth. For instance, from early sowing to the onset of winter, routine ventilation maintains temperature and humidity. However, during extreme heatwaves, greenhouse temperatures may become excessively high, intensifying crop transpiration. This necessitates not only cooling but also supplemental irrigation. Additionally, solar panels and collectors require angle adjustments in high-temperature environments, introducing significant uncertainty in photovoltaic power generation. Therefore, this study thoroughly considers extreme adverse conditions to analyze energy supply reliability under these scenarios.

The optimization objective of TSRO:

In which y represents the power output situation of the RIES, including the planned capacity of the energy storage system, CCHP, photovoltaics, wind power, and other equipment output situations. x represents the vector of continuous decision variables, and z represents the decision variable vector composed of 0–1 variables, which is made of the variable status of cooling, heating, lighting, irrigation, and the status of vehicle transportation equipment, as well as the charging and discharging status of energy storage devices. The first-stage problem is the minimization of RIES operation cost, and the second-stage problem is the power supply reliability of the APSC system under an uncertain environment.

5.2. The First Stage

The first phase of scheduling addresses a deterministic problem, considering energy output across different time periods to ensure reliable supply chain operation while prioritizing energy supply from wind, photovoltaic, and solar thermal collectors. During crop growth, node counts and LAI are obtained from the monitoring system.

Daily crop yield is updated based on node count and LAI values recorded at the end of the previous day, estimated using Equations (5)–(15), thereby determining total APSC production to ensure output meets demand.

Daily storage and transportation volumes are determined according to wholesale market demand, yielding APSC’s daily energy consumption. Ultimately, energy scheduling for both processes is coordinated to achieve synergy between energy allocation and APSC’s temporal scale, seeking a scheduling strategy that minimizes total operating costs.

5.2.1. Objective Function

For the economic objectives, the daily energy supply cost is used as the optimization index, including the greenhouse operation cost C

gh, cold storage cost C

wh, and vehicle transportation cost C

vt. The objective function is as follows:

5.2.2. Yield Constraint of Agricultural Products

5.2.4. Biogas Storage Constraint

In which Equation (44) restricts that the production or consumption of biogas, qgs.chr/dis, must be between 0 and the maximum possible production or consumption at any time t,εgs.chr/dis is a coefficient between 0 and 1, representing the efficiency, and qmax is the maximum possible. Equation (45) defines the relationship between production efficiency and consumption efficiency, both of which are less than 1. Equation (46) describes the change in biogas storage volume Vgs from time t to t + 1. Equation (47) restricts the biogas storage volume Vgs to be between the minimum storage volume Vmin and the maximum storage volume Vmax from time t to t + 1.

5.2.5. Power Grid and Heat Supply Network Constraint

In which Equations (48)–(53) represent that the total electricity supply equals the total electricity demand at any time; the change in battery energy storage Ees from time t to t + 1, the change in battery energy storage depends on the charging power Pes.chr, discharging power Pes.dis, battery efficiency ηes, and self-discharge rate σes. In Equations (54)–(56), the objective function is (34)–(37). To ensure the reliability requirements of the APSC, it is necessary to ensure the suitable growth conditions for crops and meet the yield constraint formulas (38) and (39). In energy scheduling, it is necessary to meet the energy constraints (40) and (41), biogas storage constraints (42)–(45), and the constraints of the electricity and heat networks (46) and (47). Preliminary total energy consumption of the APSC is obtained based on Formulas (16)–(32) and combined with the DEG-CG. According to the total energy consumption, a scheduling plan for wind power, photovoltaics, CCHP, and energy storage devices is formulated.

5.3. The Second Stage

The second stage is a minimax problem, which represents the optimization of the operation strategies for various equipment of the APSC under the most adverse external environment scenario. Decision variables include the start-stop of cooling/heating systems and irrigation equipment, the exposure of sodium lamps, the cha/dis strategies of energy storage devices, and the transportation time and speed of vehicles. The constraints include the energy storage devices, transportation time, operation of various electrical equipment, and the bounds of uncertain variables. The optimized operation results for the second stage were obtained through optimizing these variables.

5.3.1. Objective Function

Uncertain conditions are considered in the second phase, and the uncertain variables are mainly caused by the energy consumption load and environmental factors, in which, the uncertain set can be represented as follows, where Γx is used to adjust the conservatism of the solution.

5.3.2. Normal Crop Growth Restraint

The above formula represents the demand for resources at specific stages of crop growth, which must be met in time, and describes the relationship between crop evaporative heat and plant heat dissipation that used to control temperature and humidity.

5.3.3. Electric Vehicle Power Constraints

The transportation of electric vehicles will have demands on the mileage, volume, and time of transportation. There are K vehicles available in the distribution center, and y wholesale markets. The load capacity of each vehicle is Q, and the demand of each client is qi. The concrete constraints are as follows:

- (1)

Every wholesale market must be served

In which N is the set of all nodes, K is the set of all available vehicles, and Xijk is a binary decision variable; if vehicle k1 goes directly from node i to node j, then Xijk = 1; otherwise Xijk = 0.

- (2)

Vehicle capacity constraint

In which dij represents the demand or volume of goods from node i to node j, and Qk is the maximum load capacity of vehicle k.

- (3)

Time window constraint

In which Si represents the time that arrives at customer point i of vehicle k, tij represents the transportation time from node i to j, ai is the earliest start time for service, bi is the latest start time, and M is a sufficiently large number.

(4) Electric vehicle power constraints

In which bKLi represents the remaining battery level when leaving node i of electric vehicle k, r is the power consumption per unit distance, and di0 is the distance from node i back to the warehouse.

5.3.4. Device Operation Constraints

In which Equations (72) and (73) represent whether device i is turned on at time k (1 indicates on). Ton,min,i and Toff,min,i respectively represent the minimum time that device i must be turned on and off within a cycle. Equation (74) restricts the changes in equipment status. Equation (75) calculates the cost of turning on or off equipment i at time t. Hi is the cost coefficient related to equipment i, Coststart,i,t represents the cost of turning on equipment i at time t, and Coststop,i,t represents the cost of turning off. Equation (76) represents that there is a minimum time interval during the start and stop, and indicatori,t is used to determine whether this time interval should be considered at time t. Equations (77)–(80) represent that the battery’s charging and discharging status, and the energy storage status must be within the rated range.

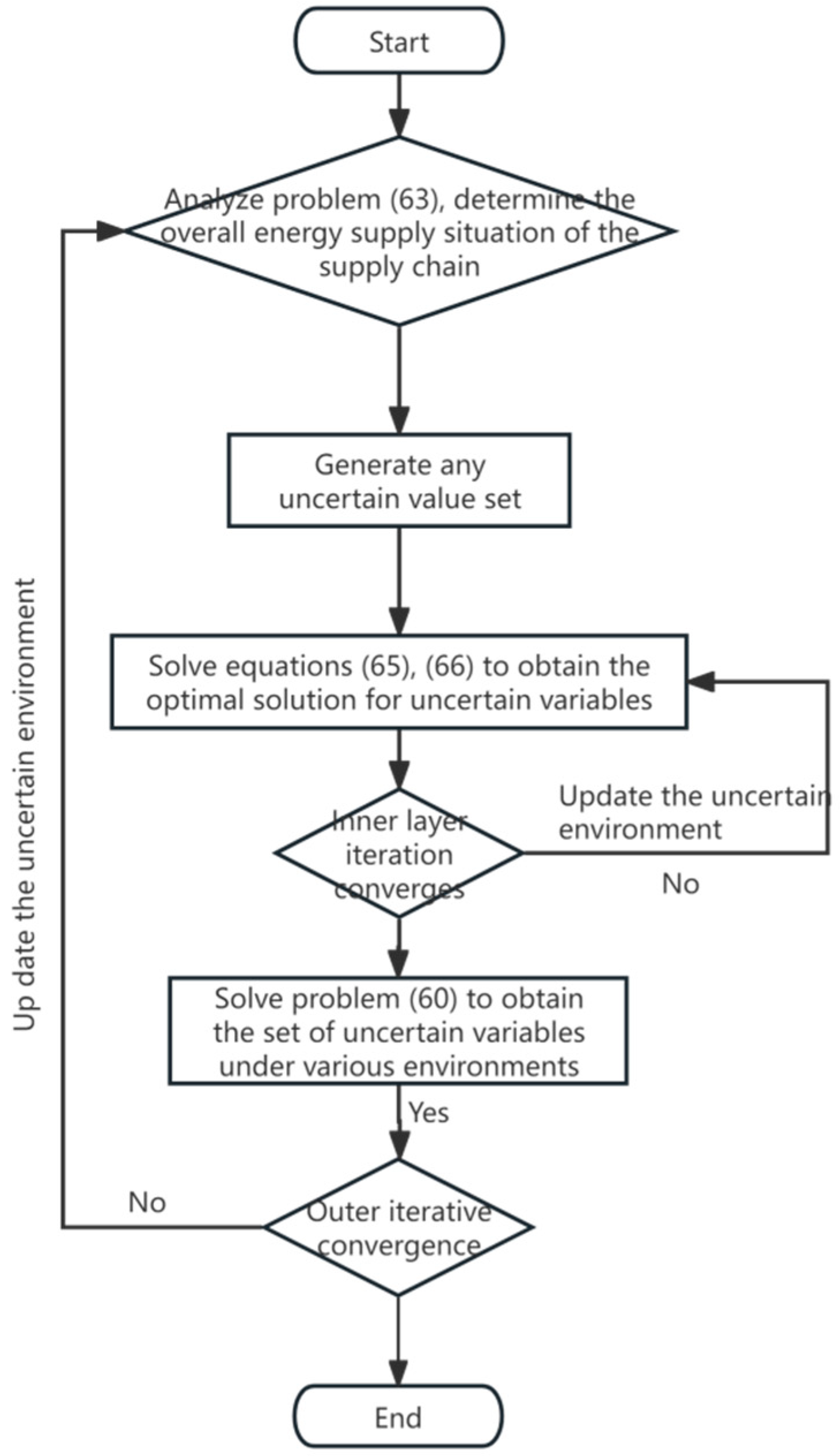

6. Nested Column and Constraint Generation Algorithm Solution Procedure

For the two-stage robust optimization problem, the normal solution is the C&CG algorithm [

51]. However, the study introduces the 0–1 variables, such as storage energy vehicle transportation, which caused the dual and KKT transformation to not be able to be directly performed; therefore, the NC and CG algorithms are adopted as a solution. The NC and CG algorithm divides the original problem into outer iterations and inner iterations. The outer iterations solve the master problem and the subproblem, while the inner iterations solve the subproblem containing 0–1 variables. As a result of the large computational load and slow convergence in the loop process of the inner iterations, auxiliary variables are introduced into the subproblem to transform it into a linear programming problem.

The compact form of two-stage robust cooperative optimization of energy scheduling

Relationship between the compact and detail constraints.

| Compact Form | Detail Constrains |

| (a) | (1)~(4) (38)~(41) (71) |

| (b) | (46)~(54) |

| (c) | (73)~(76) (55)~(58) |

| (d) | (62)~(66) (68)~(72) |

Principal problem

The principal problem is to minimize the energy supply cost of RIES, including production, energy, biogas, and line constraints, as well as the C&CG constraints returned in the subproblem, compactly formulated as follows:

In which c, d, e, f, and g represent constant coefficient vectors, and D, E, F, G, H, K, and L represent constant coefficient matrices or vectors.

Subproblem

The subproblem is to determine the start-stop status of each device to meet the reliable operation of the APSC under the given energy scheduling of the principal problem. The max-min problem cannot be solved directly, and the inner problem needs to be performed a dual transformation. This study introduces an auxiliary variable

, and the compact form of the subproblem is as follows:

The inner iteration further divides the subproblem into an inner subproblem and an inner principal problem through the C&CG algorithm. The tightened form of the inner subproblem is as follows:

The tightened form of the inner principal problem is as follows:

In which

is a continuous auxiliary variable, which is used to linearize the 0–1 variable and transform it into a linear problem. It can be derived from the following formula:

Algorithm iterative solution steps (Algorithms 1 and 2)

| Algorithm 1. Inner layer iteration |

Step 1: Set the upper bound BU1 and lower bound BL1 of the model as +∞ and −∞, set the number of iterations n = 0, generate an arbitrary uncertain variable vector u, and set the iterative convergence gap as ε ∈ [0, 1]. Convergence accuracy ∈ (0, ε/(1 + ε)).

Step 2: Solve the inner subproblem, use the given y and u to solve the inner subproblem, and obtain cTx within the relative optimal precision of ε, as well as obtain the upper bound BUMP and lower bound BLMP from the solver for the master problem. If BLMP > BL1, update BL1 = BUMP.

Step 3: Use the given x and zl. Solve the inner principal problem to obtain the optimal value u1 and of the master problem. Update BU1 = cTy + .

Step 4: Optimality test and backtracking process. If (BU1-BUMP)/BU1 < , terminate the iteration and return the planned result cTy; otherwise, carry out the following operation: if (BU1-BUMP)/BU1 ≥ , set n = n + 1, BL1 = BLMP, set = ω , and return to step 2. |

| Algorithm 2. Outer layer iteration |

Step 1: Initialize the number of iterations m = 1 and set the upper bound BU2 and lower bound BL2 to +∞ and −∞.

Step 2: Solve the external principal problem using the allocated u to obtain the optimal solution ψ and x, and update BL2 = BL2 + ψ.Step 3: Call Algorithm 1 and return the optimal solution u and , update BU2min = .

Step 4: If BU2-BL2 ≤ ξ, stop the iteration and record the results; otherwise, create new variables ym+1 and zm+1, let m = m + 1, and return to Step 2, adding the following constraints to the outer principal problem (81): |

|

The flowchart shown in

Figure 2 above illustrates the overall process of the solution algorithm. The NC and CG algorithm is used for solving the TSRO model, utilizing uncertainty variables to obtain the best scheduling results for various equipment in the APSC under the worst scenario. Optimize the goal of minimizing costs based on the obtained operational status of the equipment, and formulate a schedule for the operation of the equipment.

7. Simulation Analysis

This section uses a case to test whether the RIES-APSC system can collaborate operationally under multiple timescales and to test the algorithm. The concrete situation of the case is as follows:

For the validity of the model, RIES refers to the system built by Huang Hongxu [

58]. The capacities of CCHP wind turbines, and photovoltaic panels are 3 MW, 1 MW, and 0.4 MW, 5 solar collectors, and a 700–1000 L thermal exchange hot water storage tank, equipped with a 4 MWh battery, 6 MWh phase change material thermal storage, and 2000 m

3 GST. The biogas fermentation tank is a cylindrical underground biogas pool, whose bottom radius is 10 m and depth is 5 m. In addition, the RIES is connected to the public power grid.

For the validity of the model, primarily referring to an experimental greenhouse studied by Golzar [

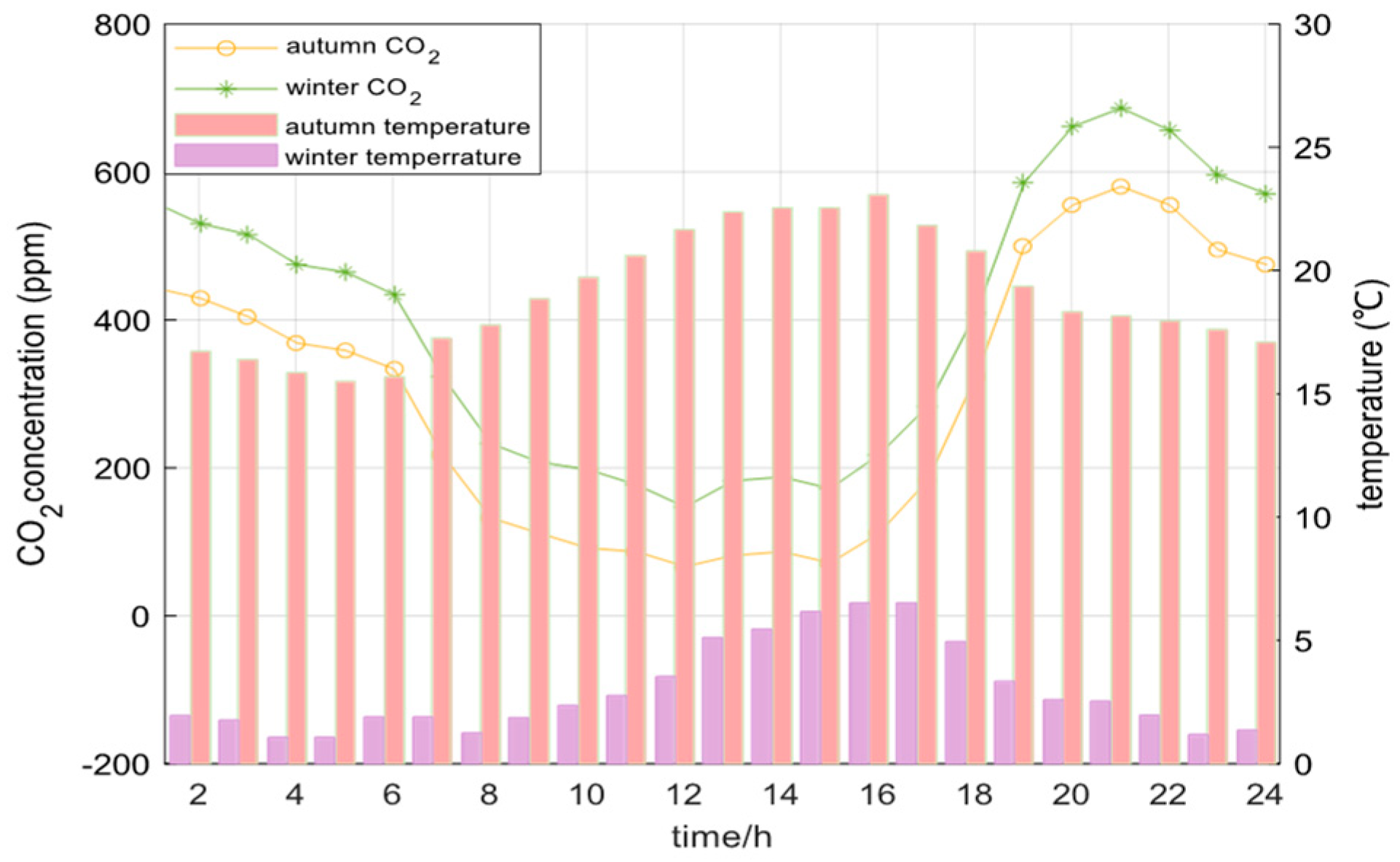

71] in Switzerland, the APSC system consists of 10 greenhouses, 1 large central cooling warehouse, and 3 wholesale markets at the end of the APSC. The greenhouse is heading north and south, 60 m long, 40 m wide, and 3.5 m high. The glass covering layer is 5 mm thick, and the roof has a slope of 40°. The crop planting density is 3.47 per square meter. The central cooling warehouse is 80 m long, 40 m wide, and 3.5 m high.

This paper’s RIES-APSC case conducts an empirical analysis on the cultivation cycle of autumn and winter crops in the southwestern region of China. Sowing the crops is completed in mid-August, finishing the harvest by mid-January of the following year, and market terminal sales are achieved by the end of February. The study conducts environment parameter prediction models based on the historical meteorological data, while the environmental conditions are sensed in real-time by monitors, and optimizes control devices through dynamic comparison of demand data and monitoring data. In which the outdoor temperature and average CO

2 concentration after crop transplanting are shown in

Figure 3.

Outdoor temperature and CO

2 concentration are the two important uncertainty parameters.

Figure 3 clearly presents the two most representative scenarios, autumn and winter, to identify the optimal energy dispatch strategy that can withstand seasonal fluctuations. The model calculates the required heating/cooling by comparing the outdoor temperature with the optimal temperature for crop growth, thereby determining the start/stop status and power output of devices such as heat pumps and boilers. The model needs to determine whether to activate CO

2 enrichment equipment based on the outdoor concentration and the optimal concentration. High outdoor concentration in autumn may require less supplementation, while low concentration in winter creates greater demand.

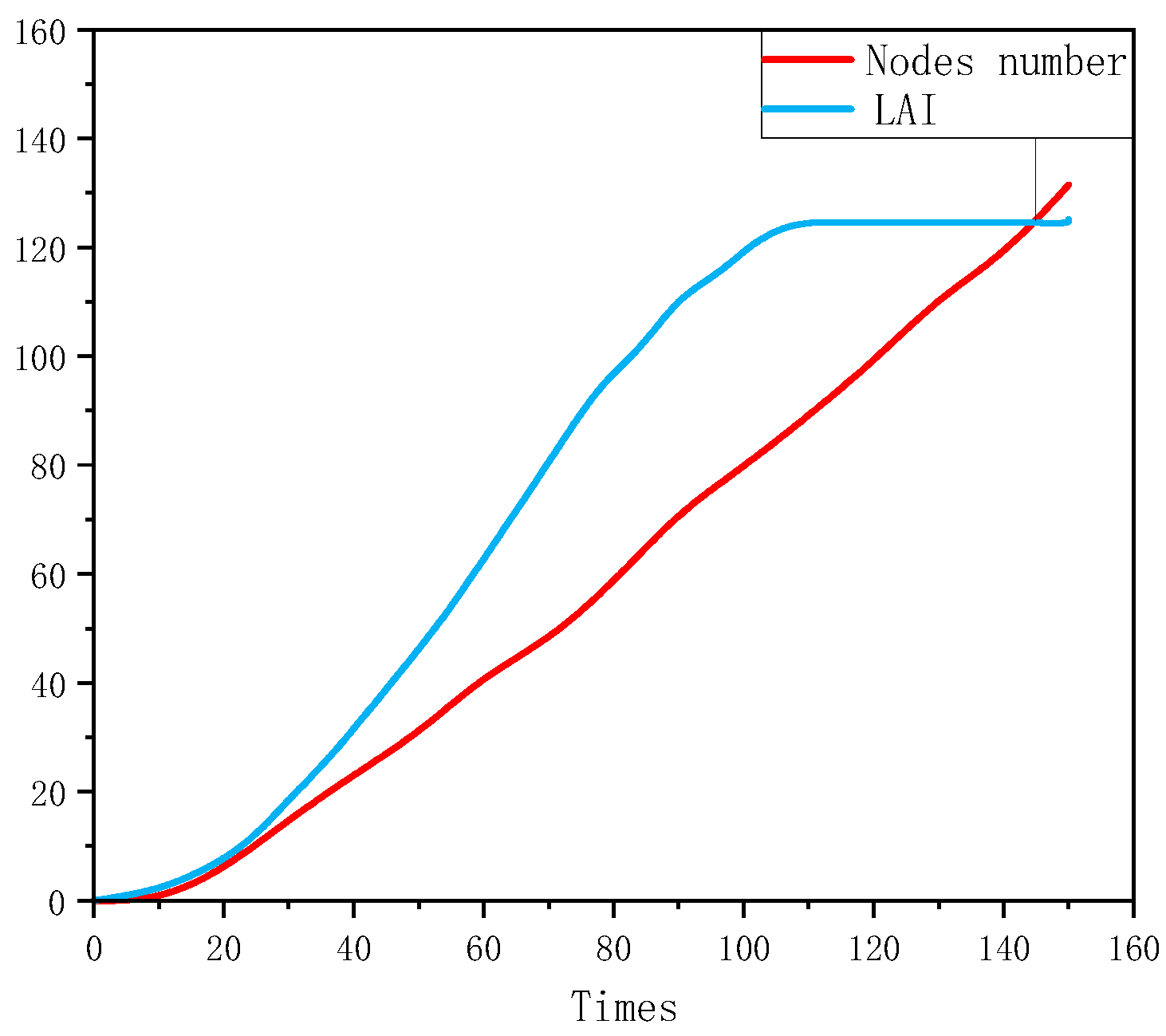

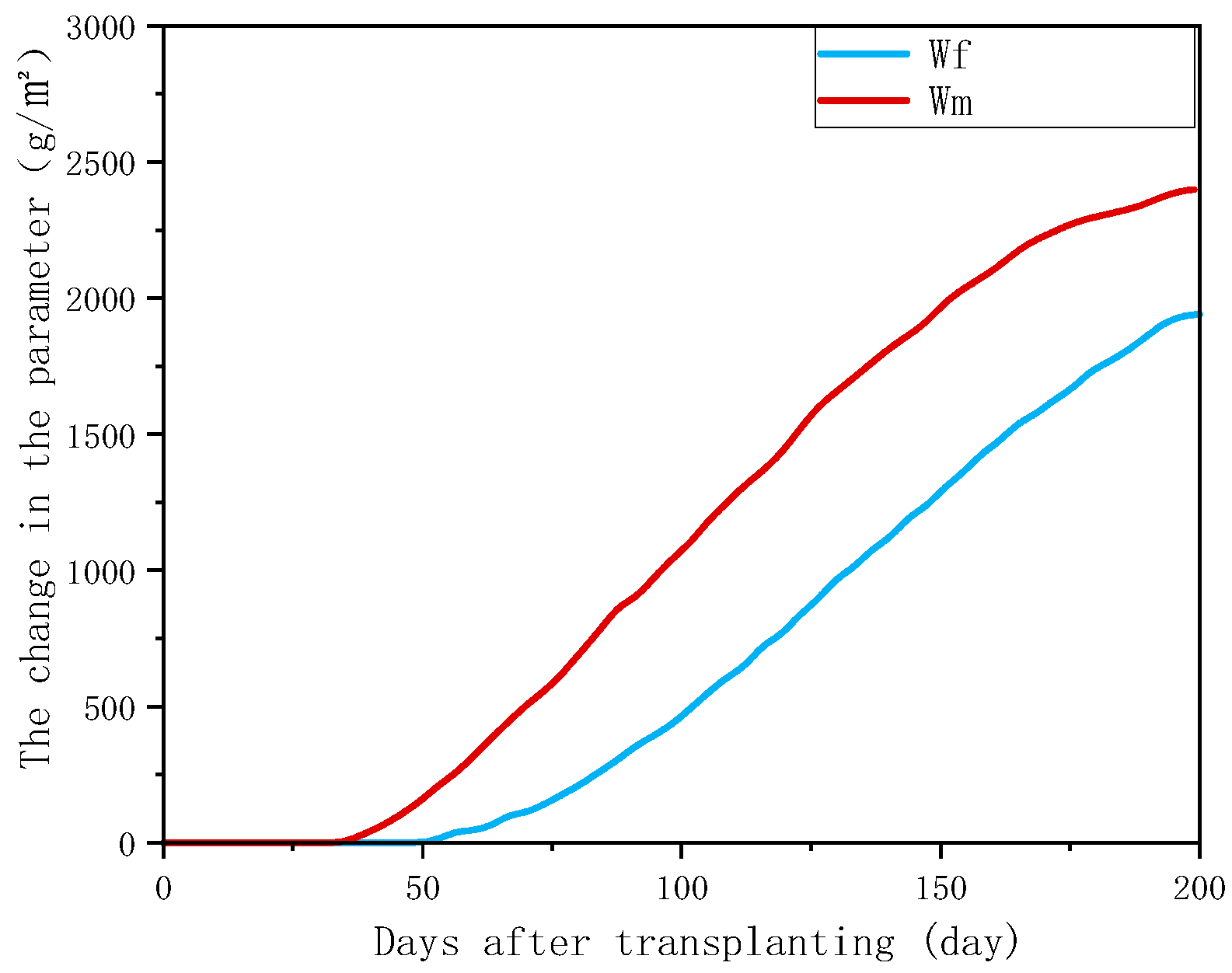

7.1. Dynamic Growth Model Results of Crops

TOMRGO, dynamically simulates the growth and yield formation process by parsing key physiological parameters of crops. The model sets W

f and W

m as output variables and calculates W

f and W

m on a daily basis. The transformation process of crops from seedlings to maturity was simulated using the nodes/LAI. The stabilization of node number marks the completion of plant growth, while the peak and decline of LAI reflect the dynamic balance of the top photosynthetic organs. W

f and W

m were used to reveal the biological pattern of yield accumulation, and the aforementioned indicators were correlated with energy demand to quantitatively characterize energy consumption at each stage.

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 present four indicators: LAI continued to grow after transplantation and reached stability on the 100th day, while the number of nodes showed a linear increasing trend, peaking on the 160th day; the dry matter of the plant priority allocated to the fruits with growing, W

m shows significant growth after about 50 days, and both exhibit a monotonically cumulative characteristic with growth days, finally leading to yield production.

During the crop growth process, samples were taken every 3–5 days to measure LAI, plant height, stem diameter, and W

f and W

m. Further comparative analysis was conducted with the crop growth model presented in this paper, observing the RMSE, R

2, and MAE between the dynamic change curves predicted by the model and the measured values. As shown in

Table 1, it was found that, throughout the growth cycle, the average predicted RMSE was 2.7, R

2 reached 0.9125, and MAE was 2.305, with an average error less than 10% and a coefficient of determination close to 1, indicating that the TOMGRO model constructed in this study can effectively simulate the dynamic growth of crop leaf area. In the later stages of growth (after 100 days), the root mean square error was relatively high, possibly due to insufficient consideration of the senescence and shedding of lower leaves. In the future, a leaf senescence sub-model may be introduced for improvement.

7.2. Energy Consumption Results of APSC

Based on the DEG-CG model, preliminarily estimate the output, and combine historical wholesale market demand data to infer the energy consumption of APSC through storage and transportation volumes.

7.2.1. Characteristic Analysis of Energy Consumption in Temperature Control

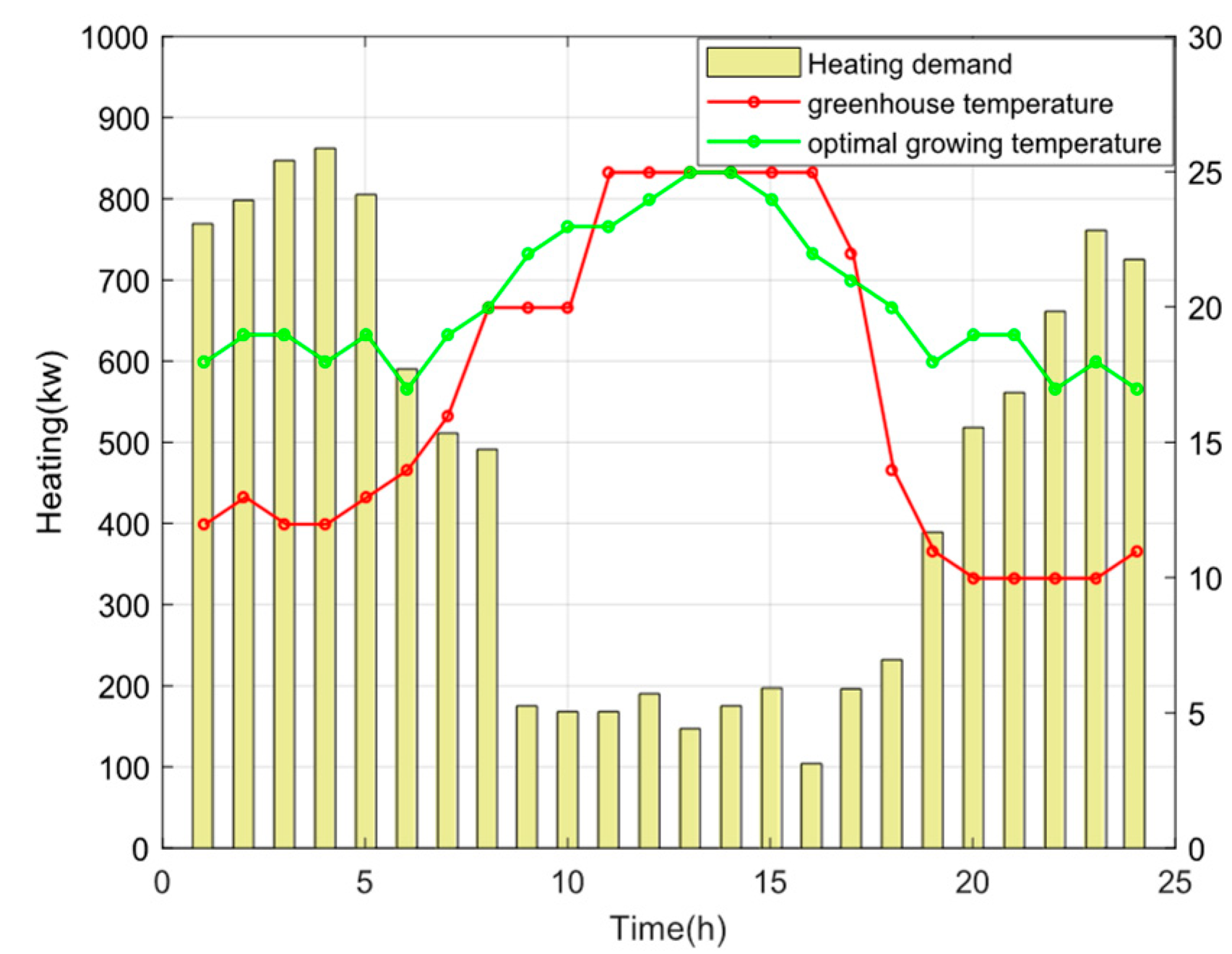

Figure 6 illustrates that during the day, temperatures are higher and the heating demand is low, and at night, temperatures are lower and the heating demand is high.

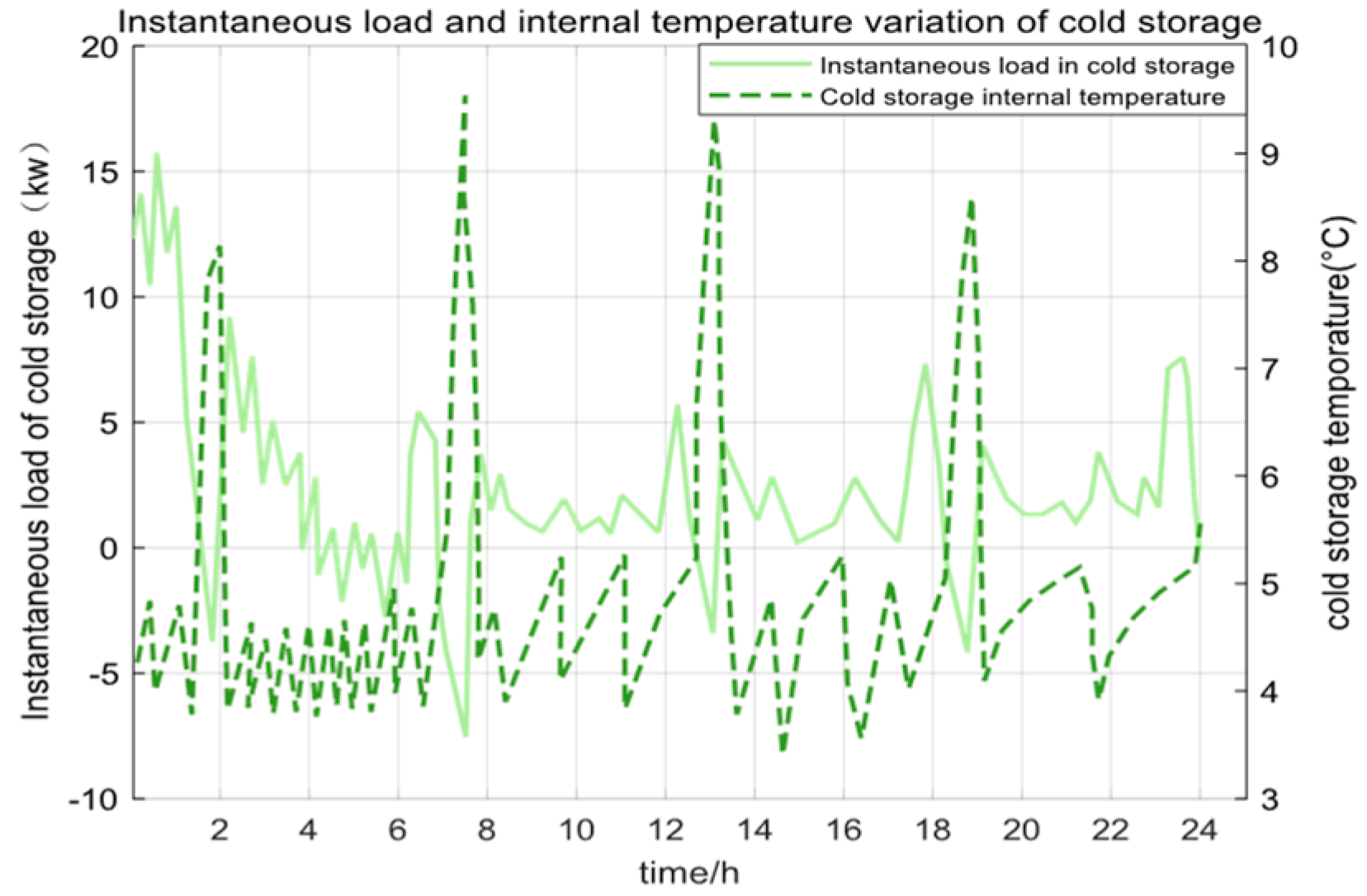

Figure 7 illustrates that crops are usually centralized in storage at three specific times: 8:00, 13:00, and 18:00, during the harvest season. These periods are peak cooling loads due to significant temperature fluctuations in the external environment.

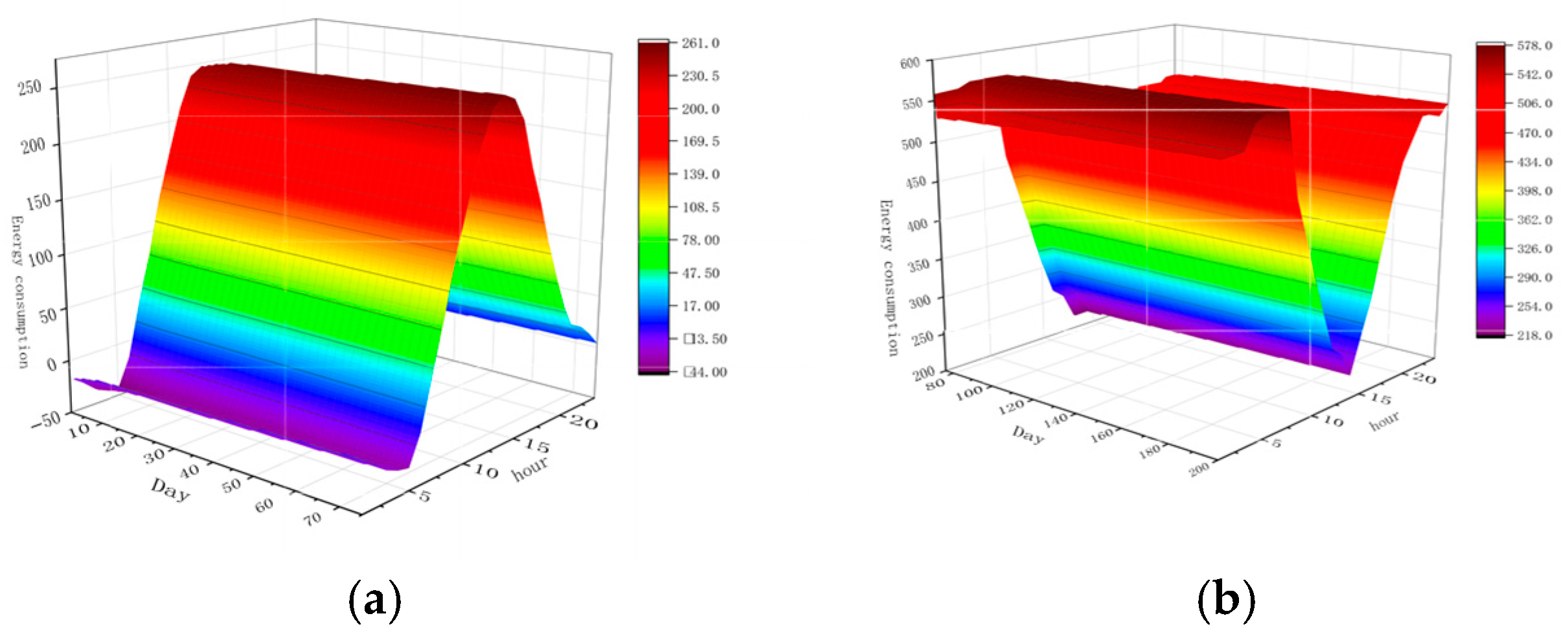

Figure 8 illustrates that the temperature control mainly focused on the greenhouse cultivation and cold storage stages. The saplings are transplanted in mid-August. It is necessary to open the cooling system during the noon period and to strengthen insulation at night to reduce the heating load. The occurrence of negative energy consumption (1:00–3:00) indicates that the waste heat generated by the decrease in indoor temperature is recovered and stored. Activating the heating system at night after seventy-five days, the heating energy consumption increases significantly with growth; around 100 days, the change rate of energy consumption decreases, but the daily trend is maintained; after 160 days, the crops enter the ripening stage, and only the storage temperature needs to be maintained.

To verify the optimization effects of different storage temperature ranges, a comparative analysis was conducted on three storage temperature schemes: −3 °C, 1 °C, and 4–5 °C. The results show that the −3 °C and 1 °C temperatures not only have higher cooling costs and require a large amount of energy to support temperature regulation across time scales, but they also lead to crop freeze damage, affecting the quality for consumption. However, the 4–5 °C can ensure the crops’ storage quality while significantly decreasing the energy consumption cost, realizing the economy and feasibility of long-term storage. The cost comparison of different storage temperatures is shown in the

Table 2 below.

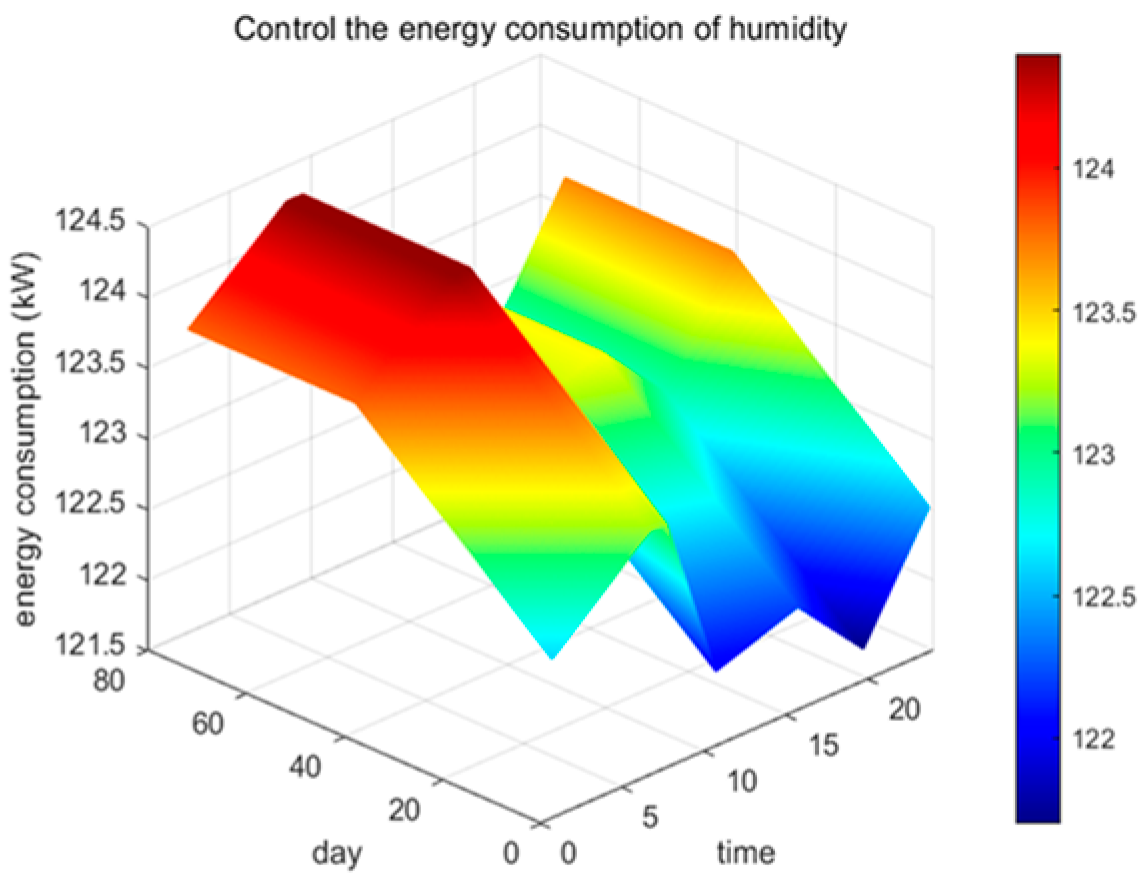

7.2.2. Characteristic Analysis of Energy Consumption in Humidity Control

Figure 9 illustrates that the humidity demand gradually increases with growing [

72], leading to a rise in energy consumption before 75 days of planting. The high temperature inside the greenhouse is not suitable for large-scale irrigation during the 11:00 to 16:00 period, resulting in lower energy consumption. In contrast, the nighttime from 20:00 to 12:00 is the main period for humidity supplementation. If this period coincides with the peak electricity usage hours, it is useful to open windows for ventilation. After 75 days, winter began, leading to intensified ground evaporation and the formation of condensation droplets adhering to the surface of the greenhouse covering materials, which further reduces the indoor humidity, resulting in energy consumption for humidity supplementation from 12:00 to 5:00 at night increasing. The supply can be reduced around 7:00.

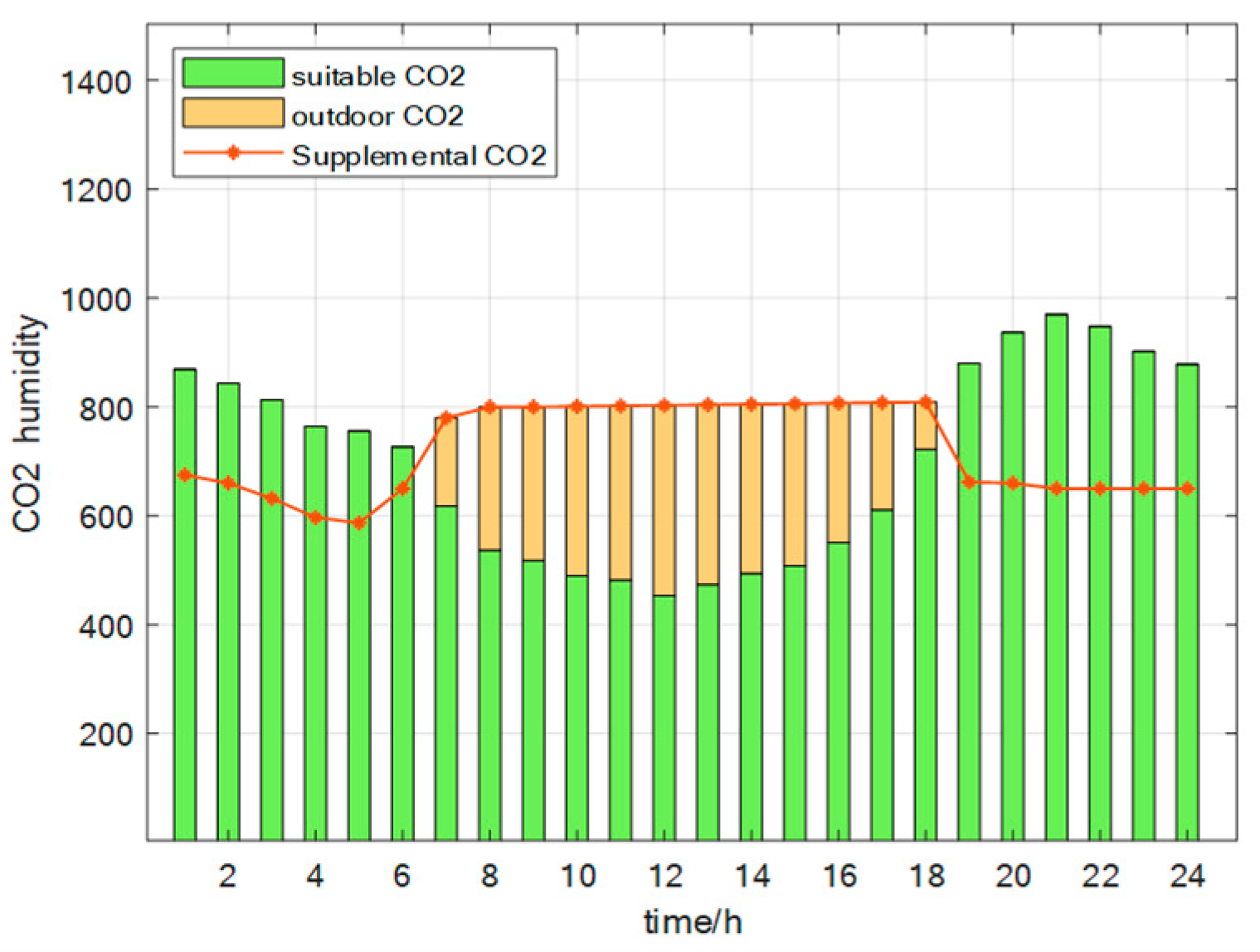

7.2.3. Characteristic Analysis of Energy Consumption in Carbon Dioxide Concentration Control

Figure 10 shows the changes in CO

2 within a day. Furthermore, the energy consumption was analyzed. 75 days before transplanting, the CO

2 concentration was relatively low from 8:00 to 16:00 during the day, and the energy consumption was high, with the peak around 12:00. The photosynthesis of crops leads to a continuous decline in CO

2 concentration, reaching its lowest point around 12:00 midnight. After 75 days, the winter greenhouse was closed for a long time, the average CO

2 concentration increased, and the energy demand relatively decreased.

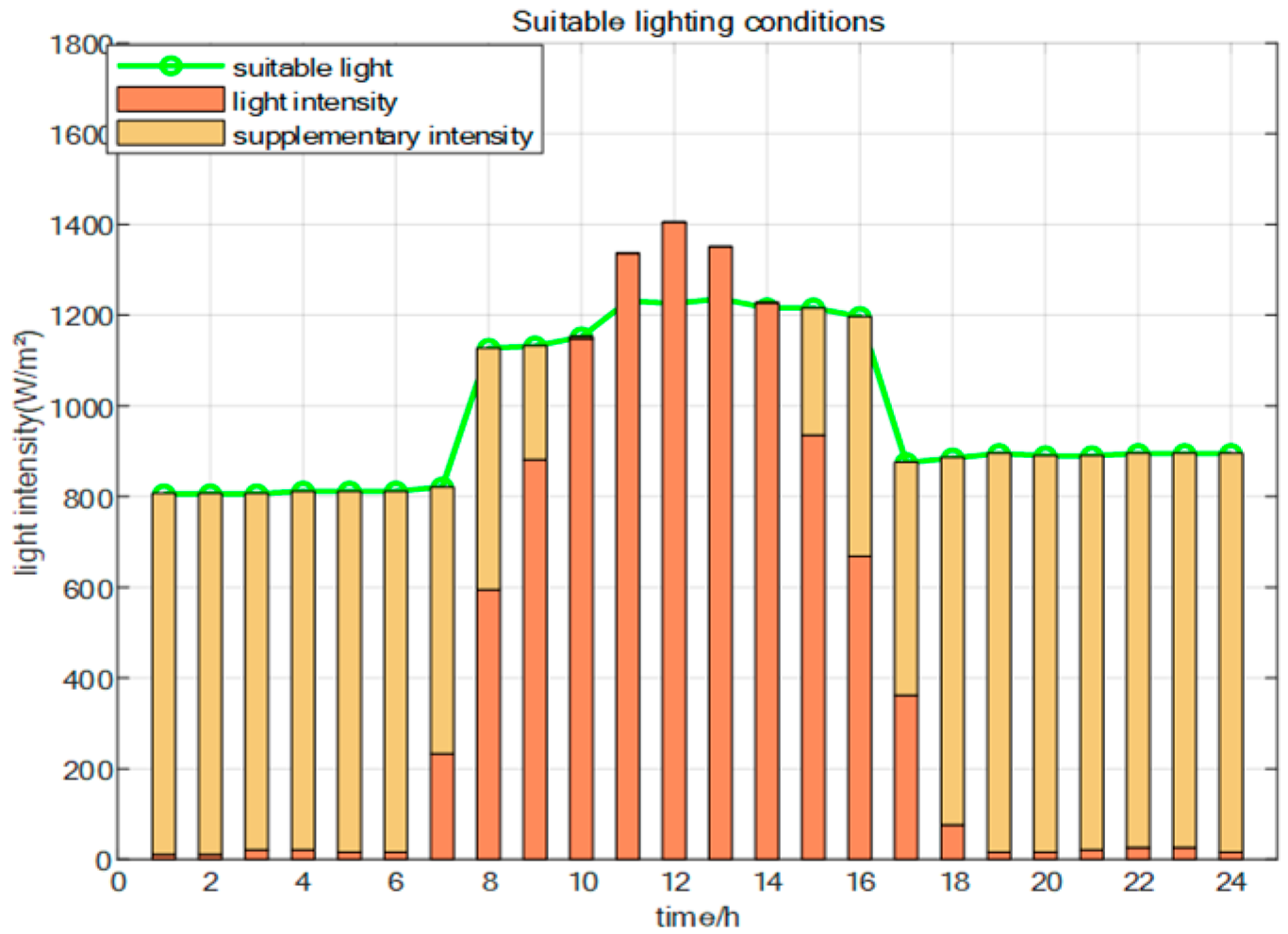

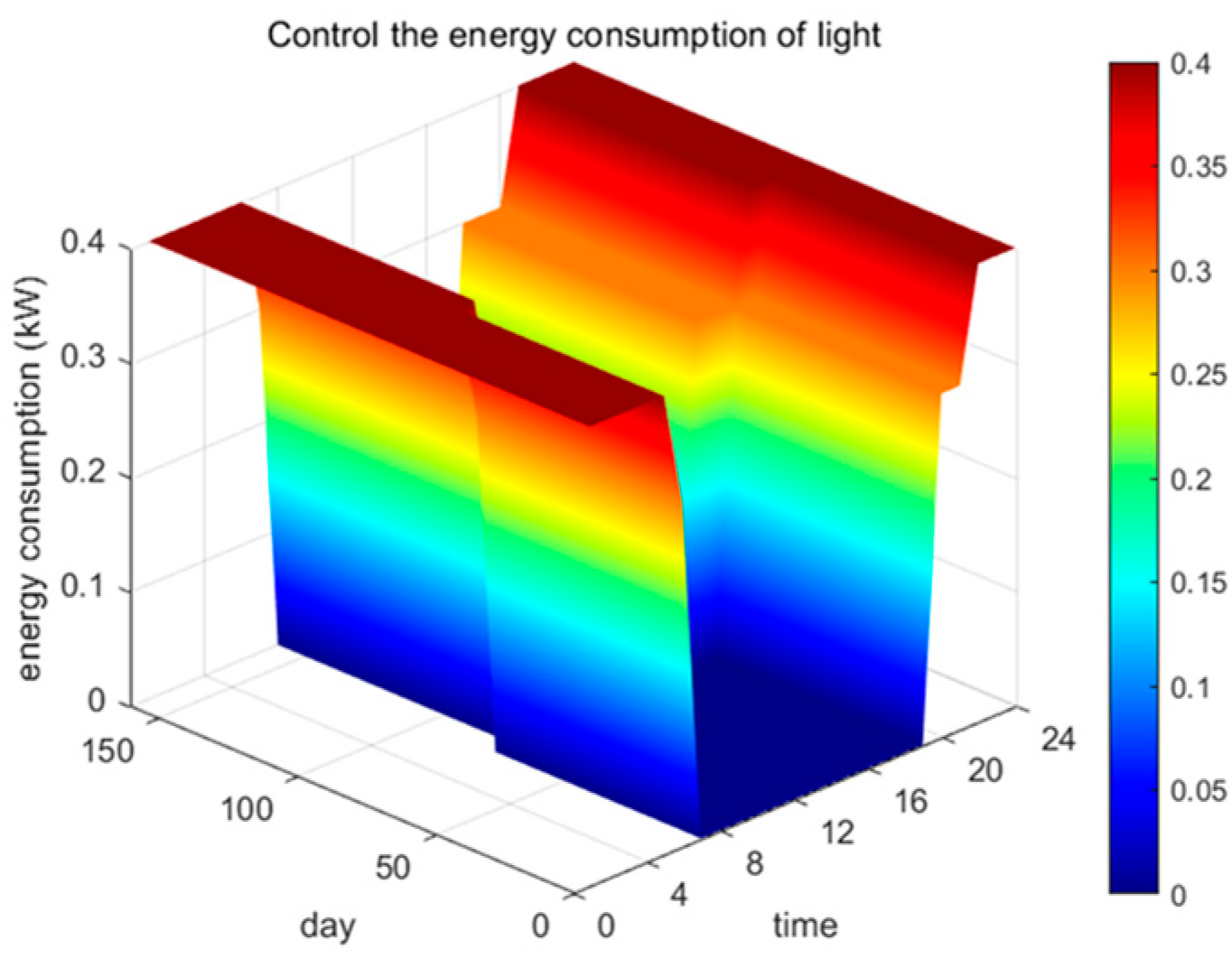

7.2.4. Characteristic Analysis of Energy Consumption in Illumination Control

Figure 11 illustrates the changes in lighting conditions throughout the day and the supplementary lighting requirements for the greenhouse. As shown in

Figure 12, with supplementary lighting from 7 PM to 6 AM the next day. The daylight during the day satisfies the photosynthesis needs of crop growth. If the electrical load is high during the night supplementary lighting period, it is necessary to appropriately reduce the power of sodium lamps.

7.2.5. Characteristic Analysis of Energy Consumption in Transportation

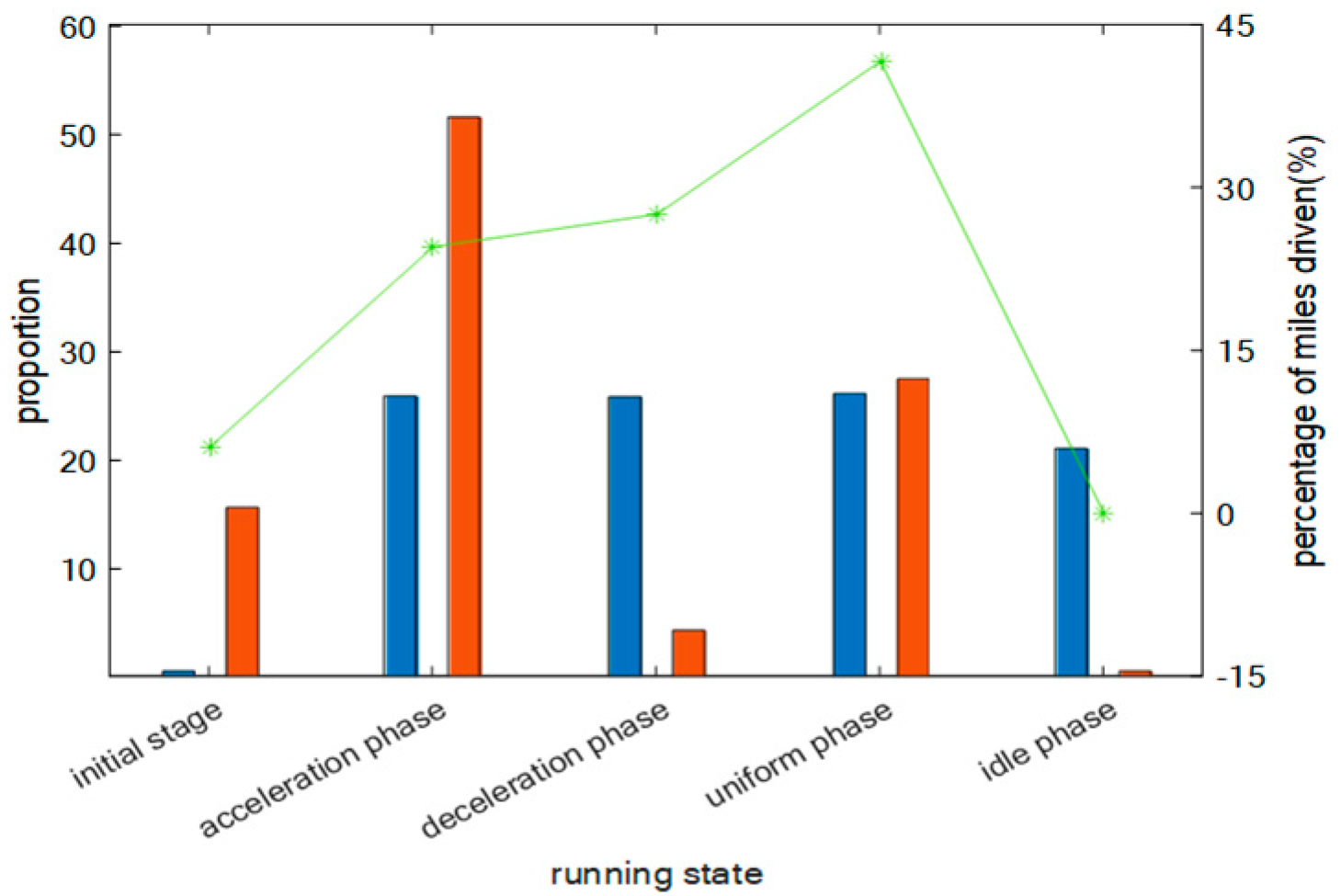

This paper considers the vehicle transportation path research with time windows, analyzing the differences in vehicle transportation energy consumption at different driving speeds. From the kinematic segment analysis of electric vehicles, the vehicle state is divided into start, acceleration, constant speed, deceleration, and idling based on speed, and then the energy consumption is analyzed.

It can be seen that the energy consumption of vehicles is related to the transportation status and driving time, according to

Figure 13. The energy consumption of starting and accelerating accounts for a larger proportion. Due to the requirements of transportation routes and time windows, the route should be planned based on the real-time traffic network between the agricultural product planting base and the wholesale market transportation section, to ensure smooth vehicle flow and reduce the time spent on acceleration and starting phases.

Table 3 shows the negative relationship between transportation and power consumption, but the shortest routine does not necessarily correspond to the shortest transportation time. Therefore, the route optimization should prioritize considering the smoothness of road conditions under the premise of satisfying the time window constraints, rather than simply pursuing the shortest path.

In the collaborative optimization framework of the RIES-APSC constructed in this paper, electric vehicles serve as key mobile units connecting energy and crops. Their operational strategies are crucial to the overall system’s economy and reliability. Among variables closely related to electric vehicle operation, such as the number of vehicles and operating distance, this paper further analyzes the sensitivity of these variables to operating costs under the same conditions. As shown in

Table 4, Suppose 50 electric vehicles are selected to transport goods to a distribution market six kilometers away from the farm, with electricity consumption per kilometer based on an energy consumption rate of 0.5 kWh/km. The results show that changes in transport distance have a more significant impact on operating costs. Therefore, in order to save costs, more vehicles than the number assigned to a single route can be deployed for relay transportation to ensure economic efficiency.

7.2.6. Energy Consumption Distribution of APSC

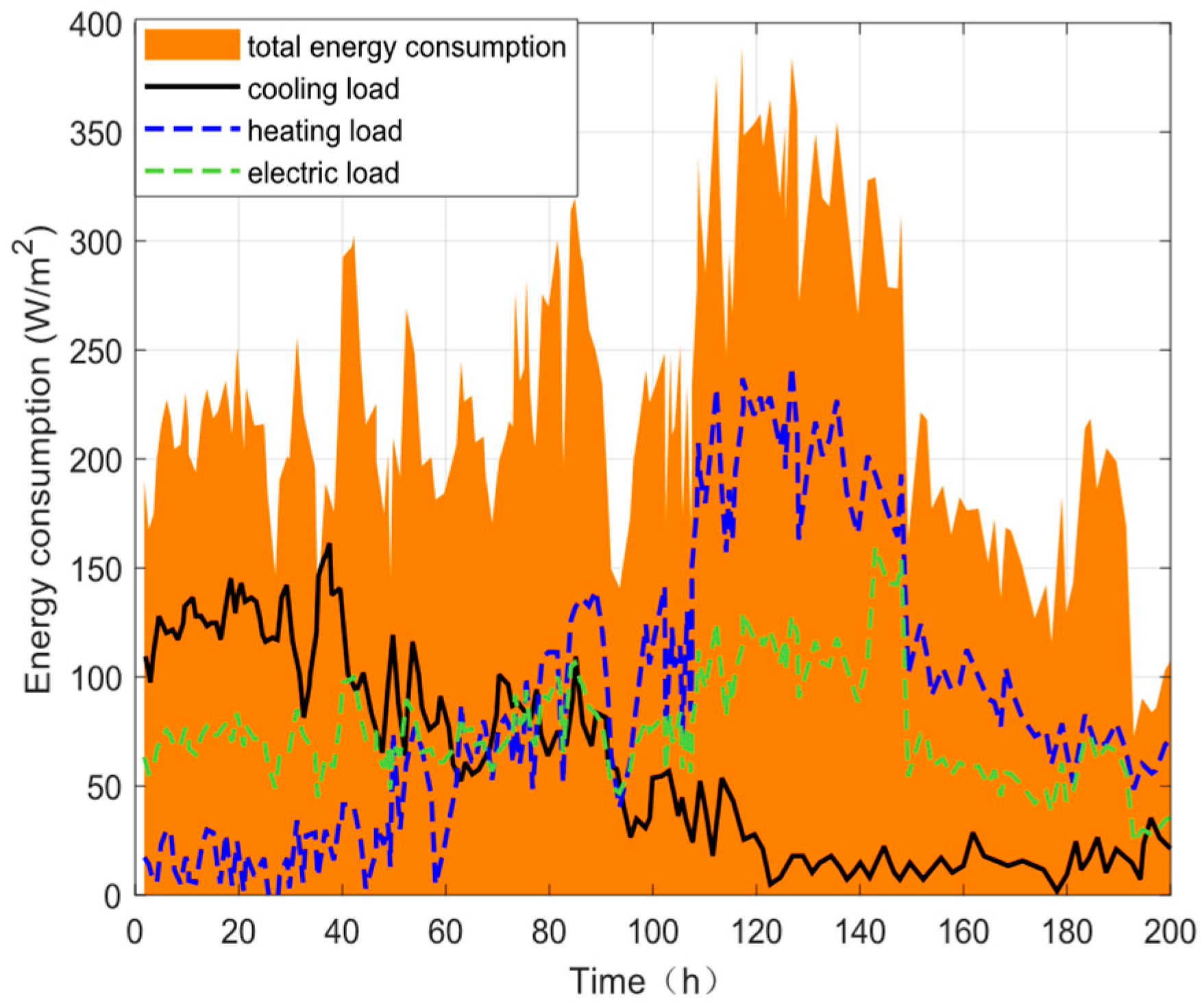

The total energy consumption distribution of the APSC is shown in

Figure 14, which visually presents the dynamic energy consumption situation of the APSC system during the growth cycle. It indicates that the energy consumption of the APSC is not a simple, single, and stable load, but a complex system characterized by multiple energy sources, strong fluctuations, and joint drivers of natural climate and human activities. This further lays the foundation for energy dispatch planning. From the figure, it can be analyzed that there is significant cooling load demand in the first 60 days; during days 60–80, the climate is suitable, and cooling and heating loads can be converted into electrical loads through ventilation operations; days 80–120 represent a key energy consumption stage, when outdoor temperatures decrease and fruits mature intensively, resulting in increased nighttime heating demand, while weakened light necessitates reliance on wind power and photovoltaic generation to meet requirements for humidity control, supplementary lighting, and CO

2 concentration regulation; after 120 days, both cooling and heating loads are significantly reduced. Refrigeration in cold storage is mainly realized through electricity conversion, with insufficient parts supplemented by the CCHP system; thermal energy demand is supplied through heat energy storage and solar collectors, and if still insufficient, electricity is purchased from the grid, with energy conversion achieved through RIES to support APSC operations. Finally, the two-stage robust optimization model takes energy consumption supply as its objective, seeking the most economical and robust supply scheme for the rural energy system.

7.3. Rural Integrated Energy Optimization Results

The energy consumption of the APSC system has been analyzed above. Whether RIES can provide a reliable energy supply requires further research into the system’s energy operation results.

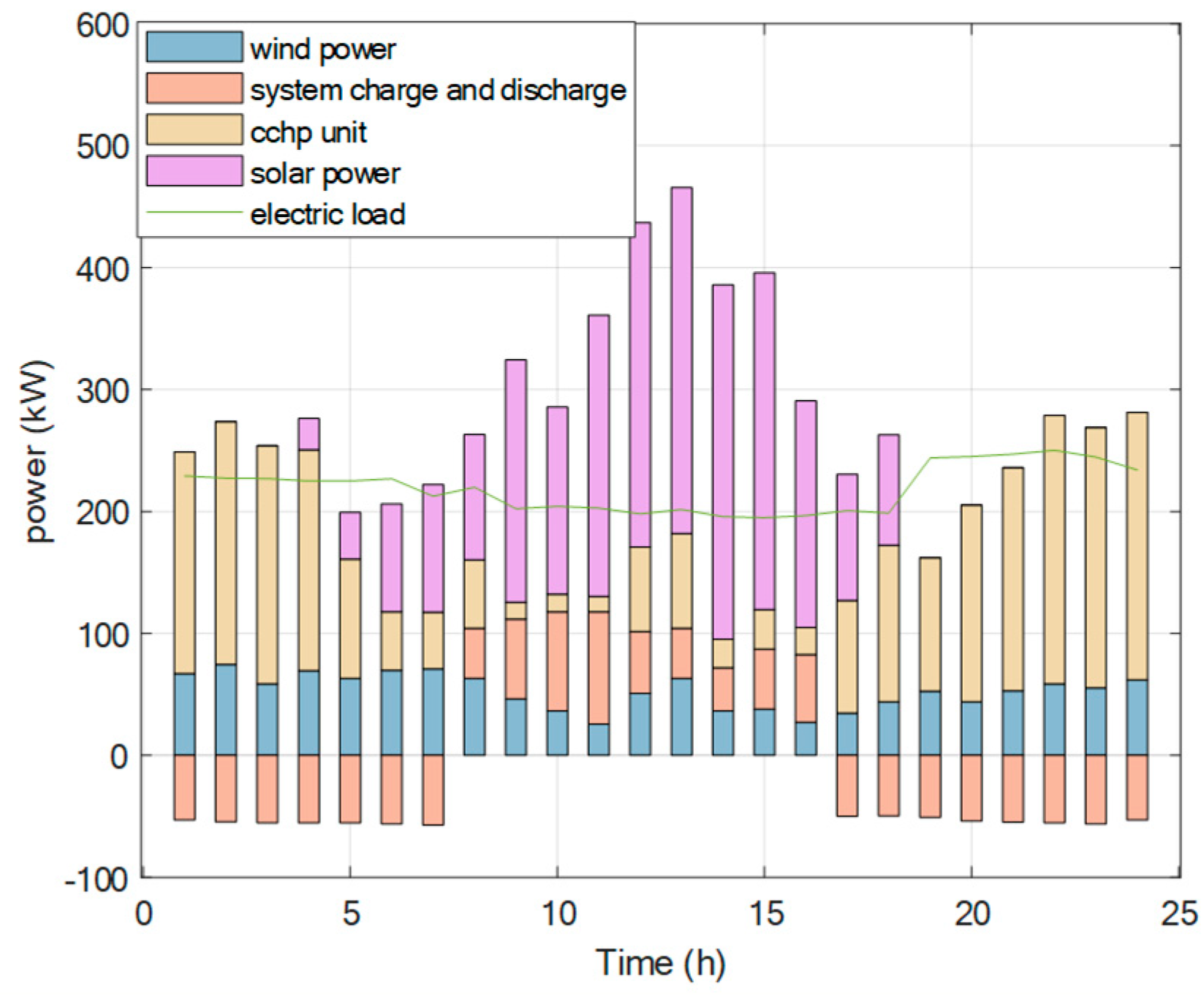

7.3.1. RIES Power Composition and Optimal Scheduling

Figure 15 illustrates the RIES’s electrical energy composition. Photovoltaic power generation is concentrated from 08:00 to 16:00, and the surplus electricity is used to increase the temperature of biogas fermentation; wind power generation is relatively small, and its output period is from 04:00 to 08:00 and from 22:00 to 24:00. The system’s chr/disc strategy can be adjusted dynamically based on energy supply and demand: the pink area with negative values indicates charging.

7.3.2. RIES Cold and Thermal Composition and Optimal Scheduling

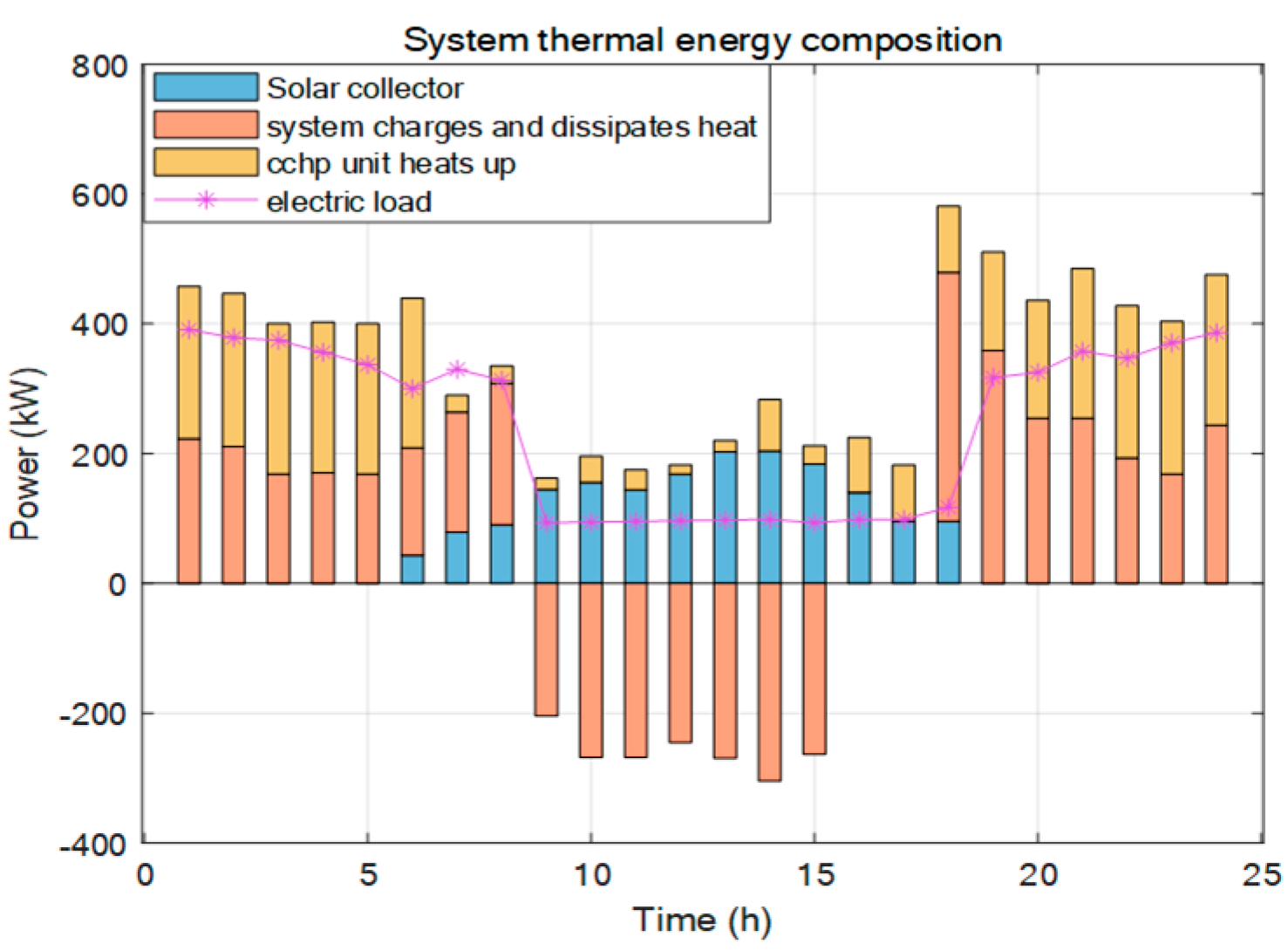

The thermal energy composition of the system is shown in

Figure 16. Solar collectors efficiently generate heat during 10:00–16:00, with the thermal load relatively low, so the excess heat is stored with priority. And the remaining part is used to increase the temperature of biogas production. The heat released by the CCHP heating and thermal storage system works together to meet the heating needs of the greenhouse during the night from 22:00 to 05:00. In the picture, the heat release of the thermal storage system is positive.

The cooling of the system is mainly provided by CCHP and electric chillers. In the early stage of the APSC, only greenhouse cultivation requires cooling, and the demand for cooling is relatively small. After 75 days, there is a need for cold storage as crops are gradually harvested, and the electric chiller meets the full-day load of cold storage. The cooling demand of the greenhouse is met by the output of the CCHP unit.

To verify the advantages of the TSRO model proposed in this paper for RIES-APSC collaborative operation, it is necessary to conduct a comparative analysis with other optimization methods based on their individual operation results. This chapter introduces Deterministic Optimization (DO), Distributionally Robust Optimization (DRO), and Scenario-Based Stochastic Programming (SP) as comparison schemes, systematically comparing them across multiple dimensions such as operating cost, total adjustment amount, and energy supply reliability flexibility indicators (load shedding rate, worst-case operating cost), as shown in

Table 5. First, 1000 wind and solar forecast error scenarios are generated using Monte Carlo simulation, with each scenario including 24 periods of wind and solar forecast error curves. It is assumed that the forecast errors in each time period follow a uniform distribution, and the standard deviation of wind and solar forecasts is 15% of the wind power forecast value. Based on the generated scenarios, the total adjustment amount and load shedding rate are calculated, and the worst-case operating cost is identified. The results show that the TSRO method provides the highest energy supply reliability (load shedding rate > 50%). It does not seek the absolute minimum cost under ideal conditions, but rather, in the face of uncertainty, exchanges an acceptable increase in cost for superior system resilience and reliability. This characteristic is critical to ensuring the continuous and stable operation of APSC and provides a new approach for APSC-RIES collaborative optimization.

By analyzing energy demand and load, the daily energy output of the RIES can meet the requirements of the APSC, but multi-time scale energy scheduling needs to be achieved through battery energy storage and thermal energy storage. The TSRO method adopted in this paper enables the RIES to provide nearly maximum energy support under the worst-case scenario to maintain the economical operation of the system. When the load exceeds the limit, electricity is purchased from the grid to ensure basic growth and storage conditions. The two-stage robust optimization method proposed in this paper ensures both good economic performance and reliable operation in the collaborative operation of RIES and APSC.

7.4. Advantages of Collaborative Operation

7.4.1. Economic Analysis of RIES-APSC Collaborative Operation

To analyze the advantages of the RIES-APSC collaborative operation, a comparative plan 2 was designed in which APSC and RIES operate separately. The equipment of the two plans is identical, and the operating costs for both plans are shown in

Table 6. In Plan 1, the load of the APSC system is flexible; ventilation measures can be taken to transfer electrical load to thermal/cooling load, achieving the conversion between different types of energy and the synergy between energy and crops across different time scales. Plan 2 does not have this characteristic. When APSC has demands for heating, cooling, and irrigation, it responds immediately, and its load does not have flexibility; the cost of collaborative operation is lower.

7.4.2. Sensitivity Analysis

Due to the significant impact of natural environmental changes on agricultural load, the paper considers the influence of environmental uncertainties. Set up various scenarios shown in

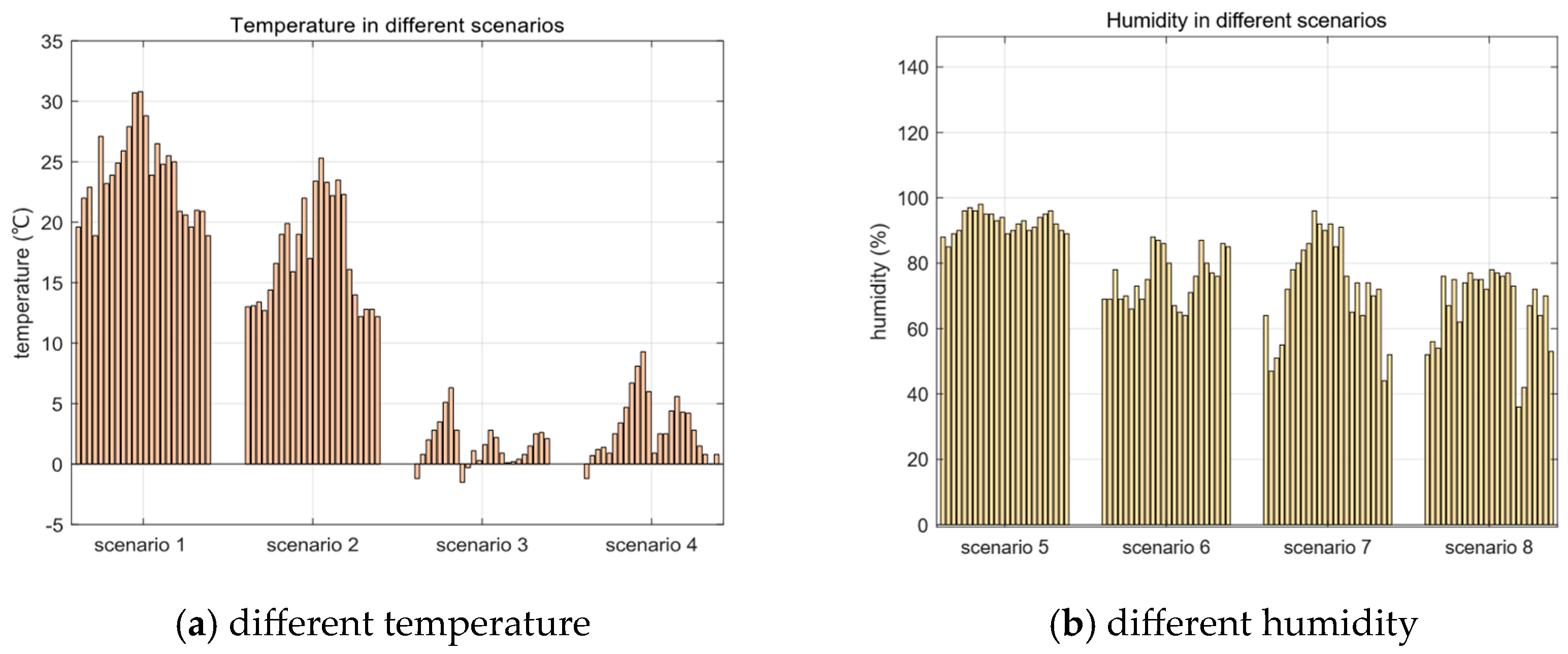

Figure 17: Scenario 1: High temperature and humidity; Scenario 2: High temperature and low humidity; Scenario 3: Low temperature and high humidity; Scenario 4: Low temperature and humidity; Scenario 5: Strong light and wind; Scenario 6: Strong light and weak wind; Scenario 7: Weak light and strong wind; Scenario 8: Weak light and wind. Based on different scenarios that meet the energy consumption and operational cost changes, determine which environmental factors have the greatest impact, and prepare for reliable supply scheduling under the most adverse environmental conditions.

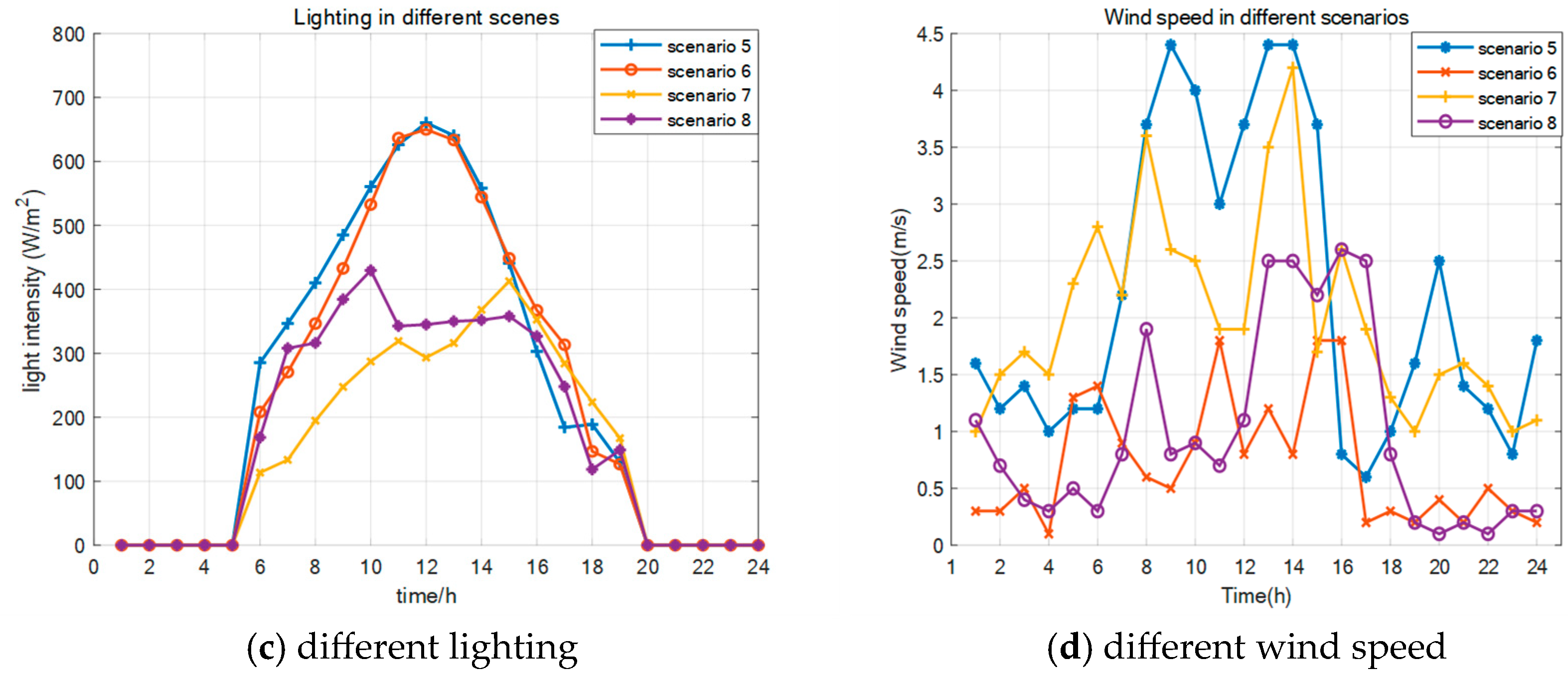

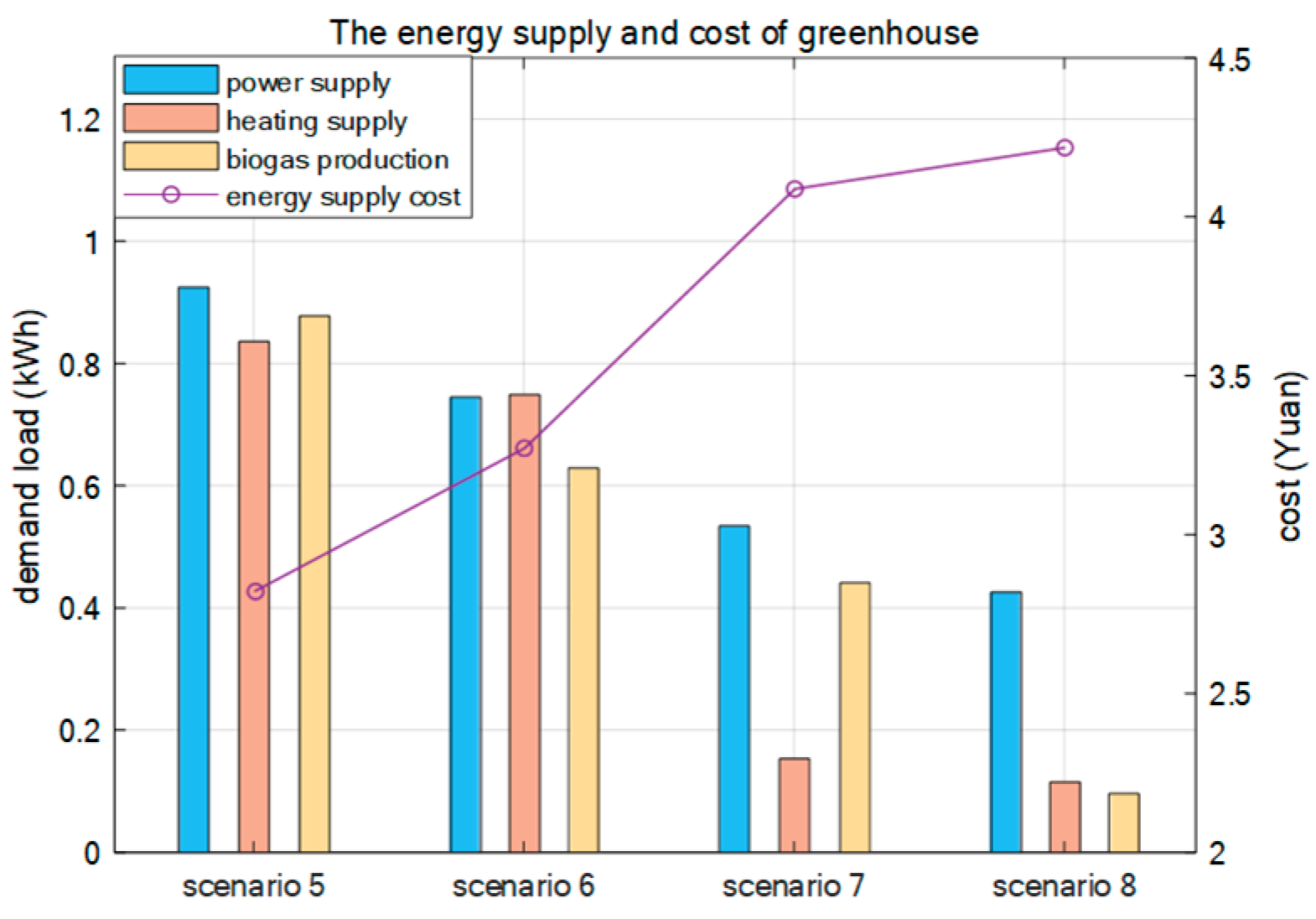

The power supply, heating, cooling demands, and operating costs of different scenarios are shown in

Figure 18. The temperatures are relatively high in Scenarios 1 and 2, and there is a significant need for cooling two months after transplantation. In Scenarios 3 and 4, the temperatures are low, and there is a greater demand for heating both during the day and at night. In scenarios 1 and 3, the relative humidity is suitable for crop growth. In scenarios 2 and 4, the relative humidity is lower, and energy support is needed for irrigation.

Temperature and humidity have a significant impact on costs. When the external temperature and humidity conditions do not change significantly and do not greatly exceed the optimal environment for crop growth, it is possible to open windows for exchange with the external environment.

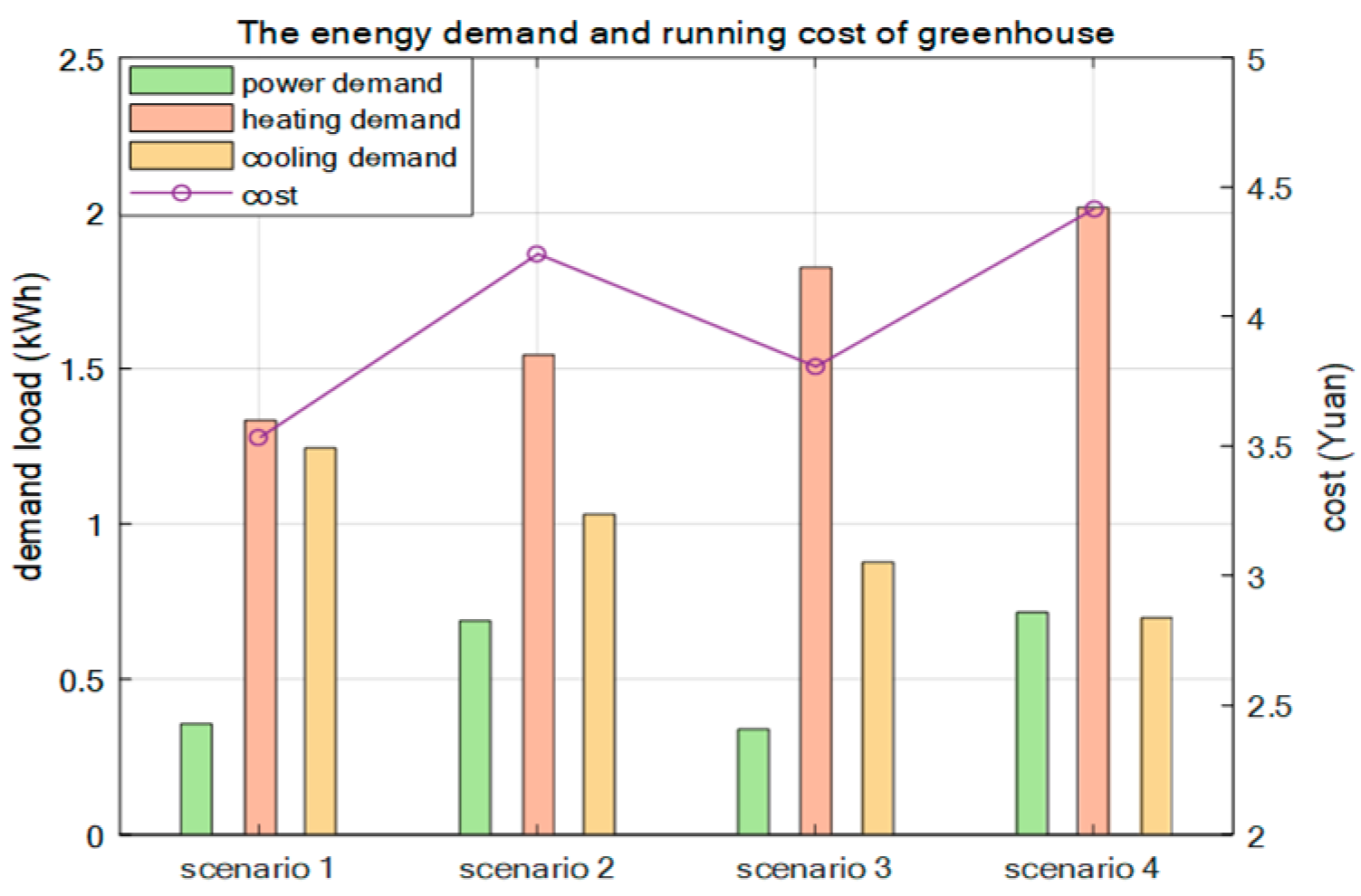

In scenarios 5 and 6, the light intensity enhances the efficiency of converting solar energy into thermal energy and biogas temperature. Scenarios 7 and 8 have lower light intensity; it is necessary to ensure the stable operation of the CCHP unit and supplement the light, which leads to increased operational costs. In scenarios 5 and 7, the wind speed is beneficial for increasing electricity generation and biogas production. However, it is necessary to pay attention to the impact of strong winds on greenhouse crops. In scenarios 6 and 8, the wind speed is lower, which limits energy output and results in higher system operation costs.

As shown in

Figure 19, the production of electricity and heat increases when the wind and solar resources are abundant. The surplus energy is used to increase temperature and aid production, which in turn reduces the cost of energy supply. Therefore, it is necessary to consider the impact of extreme temperature and humidity environments on crop growth under fluctuating conditions, and achieve the optimization of energy utilization across time scales through energy storage systems.

7.4.3. Sensitivity Analysis of Crop Growth Conditions

Based on the analysis of the above collaborative operation situation, this paper further studies the sensitivity of the proposed system to crop yield and energy consumption under different crop planting densities and planting areas. Using the collaborative DEC-CG and two-stage TSRO framework, the following detailed descriptions are given from three aspects: the impact of planting density and comparison of climatic regions. Firstly, in terms of planting density sensitivity, this paper sets the baseline density at 3.47 plants per square meter, and this parameter is directly related to LAI and node number. High-density planting can improve photosynthetic efficiency, but it also increases canopy transpiration, resulting in higher energy consumption for greenhouse humidity control. Additional control of indoor temperature and CO2 concentration is required. In addition, fruit dry matter accumulation is affected by density. Excessive density may lead to nutritional competition, delayed maturity, and reduced yield, which further increases long-term heating demand, highlighting the nonlinear relationship between density and energy consumption.

In terms of climate region comparison, this paper takes the Southwest region as the baseline (with outdoor temperature and CO

2 concentration shown in

Figure 3), and simulates extreme scenarios in the cold and dry northeast region (low temperature, low CO

2 concentration), as shown in

Table 7. The Southwest has a mild climate, with average daily temperatures of 15–25 °C in autumn and lows of 0–10 °C in winter, and higher CO

2 concentrations, resulting in a phased energy consumption pattern: cooling is predominant in the early growth period, while heating demand increases in the later stage, and abundant sunlight leads to low artificial lighting energy consumption. Meanwhile, the northeast region experiences an extended growth cycle of 20–30 days and a decrease in fruit dry matter accumulation rate, resulting in a 10% yield reduction, which highlights the dual pressures of climate on yield and energy.

To address the aforementioned challenges, the RIES-APSC collaborative framework proposed in the document achieves dynamic regulation through multi-temporal scale optimization. The TSRO model targets the uncertainty in the northeast region, maximizing adaptability in the worst-case scenario and ensuring energy supply reliability (load shedding rate > 50%). Energy storage and biogas systems play a key role in the northeast region, balancing intermittent power supply through wind and photovoltaic complementarity, while the DEC-CG model converts growth data into hourly energy consumption demand to optimize scheduling strategies. In summary, the interaction between planting density and climate zone significantly affects crop yield and energy consumption.

8. Conclusions

This paper proposes a multi-timescale RIES-APSC collaborative robust operation scheme covering energy subsystems such as electricity, heat, and biogas, as well as supply chain segments including agricultural production, storage, and transportation. By constructing a DEC-CG model and a supply chain energy consumption model, and embedding them within a robust optimization framework, the system can accurately estimate crop yields and hourly energy consumption based on the TOMGRO crop growth model. This effectively resolves the mismatch in time scales between energy scheduling and supply chain operations, providing theoretical support for the coordinated management of energy and supply chains. It transforms the agricultural production process from a purely “energy consumer” to a “flexible regulator” within the energy system. This facilitates reduced agricultural operational costs, enhanced energy self-sufficiency, and the promotion of sustainable development in both the agriculture and energy sectors. Concurrently, this study comprehensively considers the impact of environmental uncertainty on coordinated operation and rural integrated energy systems, significantly enhancing system robustness and adaptability. It also conducts an in-depth analysis of the optimization potential and advantages of RIES-APSC coordinated operation. The following key conclusions are drawn:

During crop growth, both LAI and node count exhibit significant upward trends, leading to continuously rising energy consumption for greenhouse environmental control. LAI stabilizes after approximately 100 days of growth, while node count reaches stability around 160 days. Crop yield begins to increase significantly after 50 days, with the yield growth rate showing a sustained upward trajectory. During cold storage, optimizing the storage temperature to 4–5 °C and adding a pre-cooling zone achieved a significant 25% reduction in operating costs. By precisely modeling the crop growth process, energy supply is tailored to demand, preventing waste while ensuring reliable energy availability.

The RIES-APSC system experiences peak energy consumption between 80 and 120 days, specifically during November and December, when heating demands are most pronounced. Concurrently, photovoltaic power generation significantly diminishes while thermal and electrical loads remain substantial. Therefore, energy storage and CCHP output are substantial. Energy is stored during the earlier period of lower consumption, while surplus wind and solar resources are utilized for biogas heating and production assistance. This reduces curtailed wind and solar power, enabling cross-temporal energy utilization and mutual energy conversion. Treating the APSC as a controllable load, its coordination with the energy system provides valuable “flexibility” for integrating renewable energy.

The RIES-APSC framework enhances supply chain load flexibility by efficiently integrating energy systems with APSC. It increases utilization rates of abundant rural resources such as biogas, wind, and solar energy, replacing reliance on fossil fuels or external high-carbon grid electricity in traditional approaches. This directly reduces greenhouse gas emissions from the energy supply side, improving supply chain reliability by 10–15% and significantly lowering the cost of operating integrated systems. Case studies demonstrate that integrating agricultural supply chains into rural integrated energy systems reduces total costs by 8.4%.

Even under adverse climatic conditions, the system ensures the greenhouse environment remains within the optimal range for crop growth through optimized scheduling, thereby guaranteeing the stability of agricultural product supply. This holds practical significance for achieving high crop yields. Concurrently, the allocation of flexible resources such as energy storage effectively addresses the randomness and uncertainty of renewable energy output, enhancing the system’s robustness and dynamic adaptability. For the multivariable collaborative optimization problem, the proposed NC&CG algorithm efficiently solves two-stage robust optimization models involving 0–1 integer variables. Sensitivity analysis reveals that ambient temperature exerts a significant nonlinear influence on cooling and heating load demands. Energy storage systems must be deployed to guarantee a reliable energy supply during extreme conditions, while flexibly leveraging the adjustable capacity of agricultural loads to minimize system operating costs.

9. Discussion

This study comprehensively examined energy consumption across agricultural supply chain segments, focusing on the dynamic growth processes of greenhouse crops. Key physiological parameters—including LAI, node count, and fruit dry weight—exhibit significant dynamic variations throughout the entire growth cycle, rather than the static or segmented constant values assumed in traditional research [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. This dynamic nature directly determines the energy requirements for greenhouse environmental control (as shown in

Figure 6,

Figure 8a,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10), resulting in strong temporal fluctuations in the energy consumption of APSC (

Figure 14). This finding aligns with the research directions of Golzar [

45] and Talbot [

44], both of whom emphasize the importance of coupling crop growth models with energy models. However, this study further extends this coupling beyond the single greenhouse growth stage to encompass the entire supply chain, including storage (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8b) and transportation (

Figure 13), achieving progress in expanding system boundaries and refining modeling. Through optimizing storage temperatures, sensitivity analysis of temperature settings combined with pre-cooling zone configuration reduced energy consumption by approximately 25%. This validates Su’s [

57] argument that setting 0 °C as the setpoint achieves 27% energy savings. Considering operational losses from frequent equipment start-stop cycles, this study sets the range at 4–5 °C.

The coordinated operation framework effectively leverages the flexibility of energy storage and CCHP systems to smooth fluctuations in APSC loads. During daytime photovoltaic output peaks (08:00–16:00), surplus electricity is not only stored but also utilized to elevate biogas digester temperatures (Formulas (1)–(3)), thereby increasing subsequent biogas production and CHP generation capacity. This “energy transfer across time” and “multi-energy complementarity” strategy plays a crucial role during the peak energy consumption period of the APCS (80–120 days post-transplantation), significantly reducing reliance on the conventional grid and enhancing the local consumption capacity of rural renewable energy. This finding aligns with Wang Yongli’s [

26] conclusion that biomass-solar coupling increases energy utilization by 24% and further reduces costs. However, this study enhances the system’s regulatory capacity by introducing APSC as a flexible “demand-side resource.”

Faced with dual uncertainties in renewable energy output and agricultural environmental demands, this study employs a two-stage robust optimization (TSRO) model and the NC&CG algorithm to seek economically optimal solutions under worst-case scenarios. Sensitivity analysis (

Figure 17,

Figure 18 and

Figure 19) reveals the impact of varying environmental conditions—temperature, humidity, sunlight, and wind speed—on system operating costs and energy requirements. Results indicate that extreme temperature scenarios exert the most significant impact on total system costs, as they directly trigger drastic fluctuations in cooling/heating loads, testing the supply limits of the energy system. This conclusion aligns with the findings of Ding [

51] and Zeng [

50] regarding the advantages of TSRO in addressing uncertainty. This study successfully applied the methodology to the interdisciplinary RIES-APSC system while resolving computational challenges arising from the introduction of numerous 0–1 decision variables. Compared to Li’s [

24] robust optimization for rural wind-solar-biogas system capacity allocation, this research not only addresses energy-side configuration and scheduling but also incorporates agricultural-side operational strategies as endogenous decision variables. This achieves source-load coordinated robustness, enhancing system reliability by 10–15%.

This study builds upon the aforementioned research but still has limitations. First, certain parameters in the model (such as crop growth model parameters and equipment cost coefficients) rely on specific case studies and literature. Future work requires broader calibration and validation using actual measurement data, and their universality across different crop growth patterns warrants further discussion. Second, the synergistic system describes energy consumption within a single crop growth cycle. Whether crop residues like straw can continue to be utilized for renewable energy and prepare for the next crop season requires strengthened coupling analysis over longer time scales. Third, while the NC&CG algorithm proves effective, computational efficiency remains a challenge for larger-scale systems. Future research may explore more efficient heuristic algorithms or distributed computing approaches. Finally, this study primarily focuses on economic objectives and reliability. Future work could incorporate environmental metrics such as carbon footprint and water consumption into the multi-objective optimization framework to provide a more comprehensive assessment of system sustainability.