Abstract

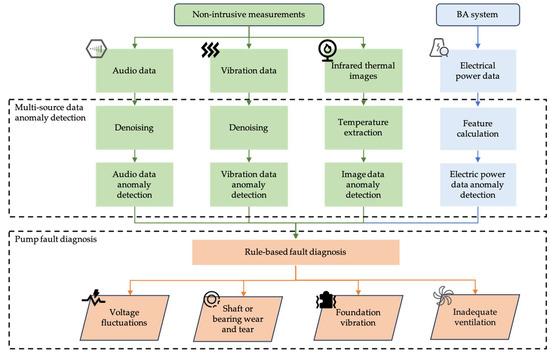

Fault detection and diagnosis (FDD) in pumps is crucial for building energy management by detecting the abnormal operation status, increasing the service life of equipment, and enhancing the energy performance of buildings. Most FDD methods predominantly rely on single-source data, such as building automation (BA) data or vibration data. However, sensors in BA systems are prone to inaccuracies, which consequently impedes the performance of FDD algorithms. This paper proposes a novel FDD method for pumps based on multi-source data, which integrates traditional BA electrical power data with non-intrusive measurements, including audio data, vibration data, and infrared thermal images. The method includes two stages: (1) multi-source data anomaly detection and (2) pump fault diagnosis. Various fault scenarios were tested on an experimental platform. The results demonstrate that the proposed method can effectively diagnosis pump faults in detail, such as voltage fluctuations, shaft or bearing wear and tear, inadequate ventilation, and foundation vibration. With intrusive and non-intrusive data, the proposed FDD method is more robust and could provide more detailed diagnosis of pump faults.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Pumps are essential equipment in building mechanical systems, including heating, ventilation and air-conditioning, plumbing, and domestic hot water systems. It is estimated that the electric motor systems, including power supply equipment, mechanical transmission equipment, and driven equipment (such as pumps, fans, and compressors) account for more than half of all electrical energy in the industrial and building sectors [1]. With growing focus on sustainable manufacturing, some studies tried to identify the causes of energy losses in pump systems. Cieślicki, R. and Karpenko, M. [2] investigated how pump deformations affect circumferential gap height of external gear pumps. Ji et al. [3] simulated and analyzed the energy loss across various components of a shaft tubular pump device under different operating conditions. Orosnjak proposed an Energy-Based Maintenance (EBM) paradigm [4] and applied a dynamic functional-productiveness method to analysis the energy waste of a hydraulic systems [5].

As important driven equipment, pump faults not only reduce their own operational efficiency, increase energy consumption, and shorten service life, but also affect the operation efficiency of the whole system, potentially causing damage to power supply equipment. Therefore, fault detection and diagnosis (FDD) in pumps is important for building energy management by detecting the abnormal operation status, increasing the service life of equipment, and enhancing the energy performance of buildings.

1.2. Literature Review

Pump faults can be categorized into four groups: mechanical, power-related, hydraulic, and operational faults. Mechanical faults are caused by physical problems of the pump’s components, including shaft or bear wear and tear, impeller defects, misalignment, and foundation vibration. Power-related faults are from power sources, such as power fluctuations and phase loss in three-phase motors, which would lead to motor faults. Hydraulic faults are flow-related problems, including cavitation, recirculation, vapor trapped in pumping fluid, inadequate ventilation, improper viscosity, etc. Operational faults indicate problems caused by unreasonable pump control strategies, including abnormal water temperature, high or low flow rate, etc. Operational faults not only place pumps in inefficient operation states, but also cause damage to the components of pumps. These fault types are interdependent, meaning that one can lead to another, and multiple faults may happen at the same time [6], which increases the difficulty of pump FDD.

FDD process mainly consist of three parts: data collection, data preprocessing, and FDD model developing [7]. Data preprocessing prior to FDD modeling is primarily conducted to reduce noisy data and extract more significant features as model inputs, thereby enhancing FDD performance. Common preprocessing techniques include wavelet transform (WT), principal component analysis (PCA), Fourier transform, empirical mode decomposition (EMD), etc. FDD models can be divided into two categories: knowledge-based methods and data-driven methods [8]. Knowledge-based methods rely on past information to construct rules or models for FDD. Data-driven methods can automatically train FDD models by classification or clustering algorithms. Table 1 lists the fault types, input data, and methods for pump FDD research.

Table 1.

Summary for pump FDD research.

As shown in Table 1, the majority of pump FDD studies focus on mechanical faults, with vibration data being the predominant data type. Many researches require installing multiple vibration sensors at different locations on the pump, which presents significant practical implementation challenges in real applications. Audio data offers easier acquisition compared to vibration measurements, but it requires substantial focus on noise reduction. Current research mainly uses audio data to detect faults of piston pumps. Now, there is a growing trend toward applying multi-source data fusion approaches for fault detection, primarily integrating audio, pressure, vibration, and displacement data to train FDD models.

In practical applications, sensors are highly prone to malfunctions. For single-data-source FDD methods, it is necessary to consider data quality issues arising from sensor faults. Furthermore, when both positive (normal) and negative (fault) samples are available, both single-source and multi-source FDD models can perform well. However, the main challenge in practical applications remains the lack of fault data, which hinders model deployment in real engineering projects or transfer to new pump systems.

1.3. Study Aims and Objectives

In order to enable pump FDD in practical engineering cases lacking historical fault data, this paper proposes a novel FDD method for pumps based on multi-source data, which integrates traditional intrusive BA electrical power data with non-intrusive measurements, including audio data, vibration data, and infrared thermal images. The method includes two steps: multi-source data anomaly detection and pump faults diagnosis. By analyzing anomaly indicators from different data sources, the proposed method reduces the risk of missed fault detection and demonstrates enhanced robustness. Unlike conventional FDD methods that require a lot of sensors or complex models to identify different fault types, which usually need to retrain the model for a new case, our method can be directly deployed in new pump systems. An experimental platform was established to validate the effectiveness of the proposed method in detecting pump faults, including voltage fluctuations, shaft or bearing wear and tear, inadequate ventilation, and foundation vibration.

The rest of paper is structured as follows: Section 2 introduces the experimental platform, the proposed pump FDD method, and the evaluation method. The anomaly detection results for each data source and the fault diagnosis results based on multi-source data are shown and discussed in Section 3. Section 4 summarizes the proposed method by contributions, limitations, and future work.

2. Methods

2.1. Experimental Platform and Data Collection

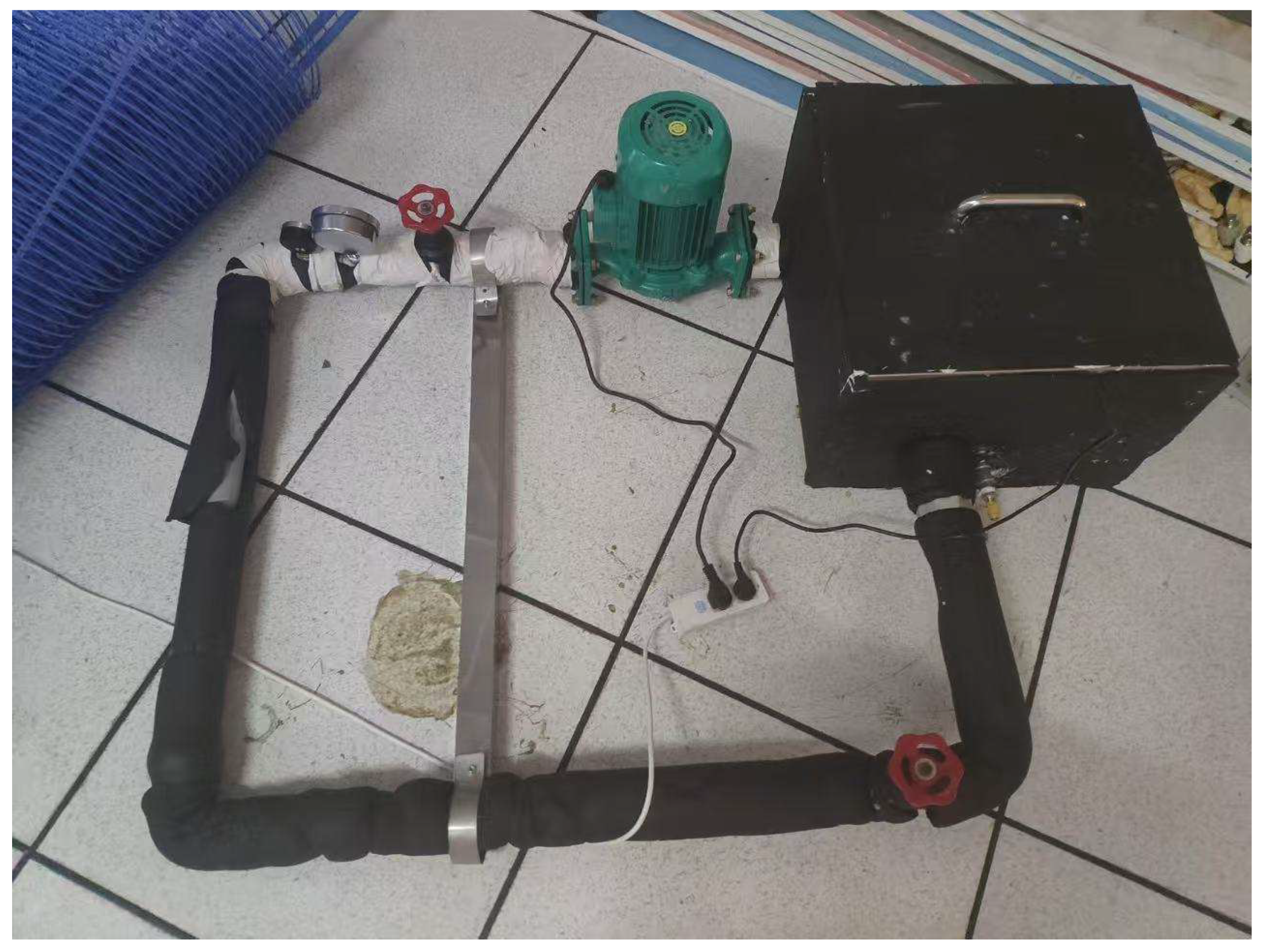

To address the lack of fault data from actual operational systems, an experimental platform (shown in Figure 1) is established to collect multi-source data for pumps under both normal and faulty operating conditions.

Figure 1.

Experimental platform.

The experimental pump is a circulation pump with a rated head of 15 m, a rated speed of 2860 rpm, and an output power of 750 W. The audio signals are collected by ReSpeaker Mic Array v2.0. Vibration data are collected with a magnetically mounted vibration velocity sensor attached directly to the pump surface. The infrared thermal images are taken by FLIR-E6 camera. The electrical power data are collected by a voltammeter during operation. Table 2 lists the parameters of sensors in detail.

Table 2.

Parameters for sensors.

According to the Shannon–Nyquist sampling theorem [26], the sampling frequency for the digital signal should exceed twice the bandwidth of the signal to capture all its information. Combined with the Fourier transform results of the actual data, the significant frequency components of the audio and vibration data are concentrated within 10,000 Hz and 200 Hz, respectively. Therefore, the audio signals in this work are sampled at a frequency of 22,050 Hz (in sampling process of 20 s), while the vibration signals are sampled at 500 Hz (in sampling process of 10 s).

In order to generate fault data, specific measures are implemented to the experimental platform. Table 3 lists the experimental methods for different pump faults.

Table 3.

Experimental methods for different pump faults.

In practical engineering, pump rooms or chiller plant rooms inherently contain ambient noise generated by other equipment. Therefore, background noise is collected from an actual chiller plant room for incorporation into the experimental audio data.

2.2. Multi-Source FDD Method

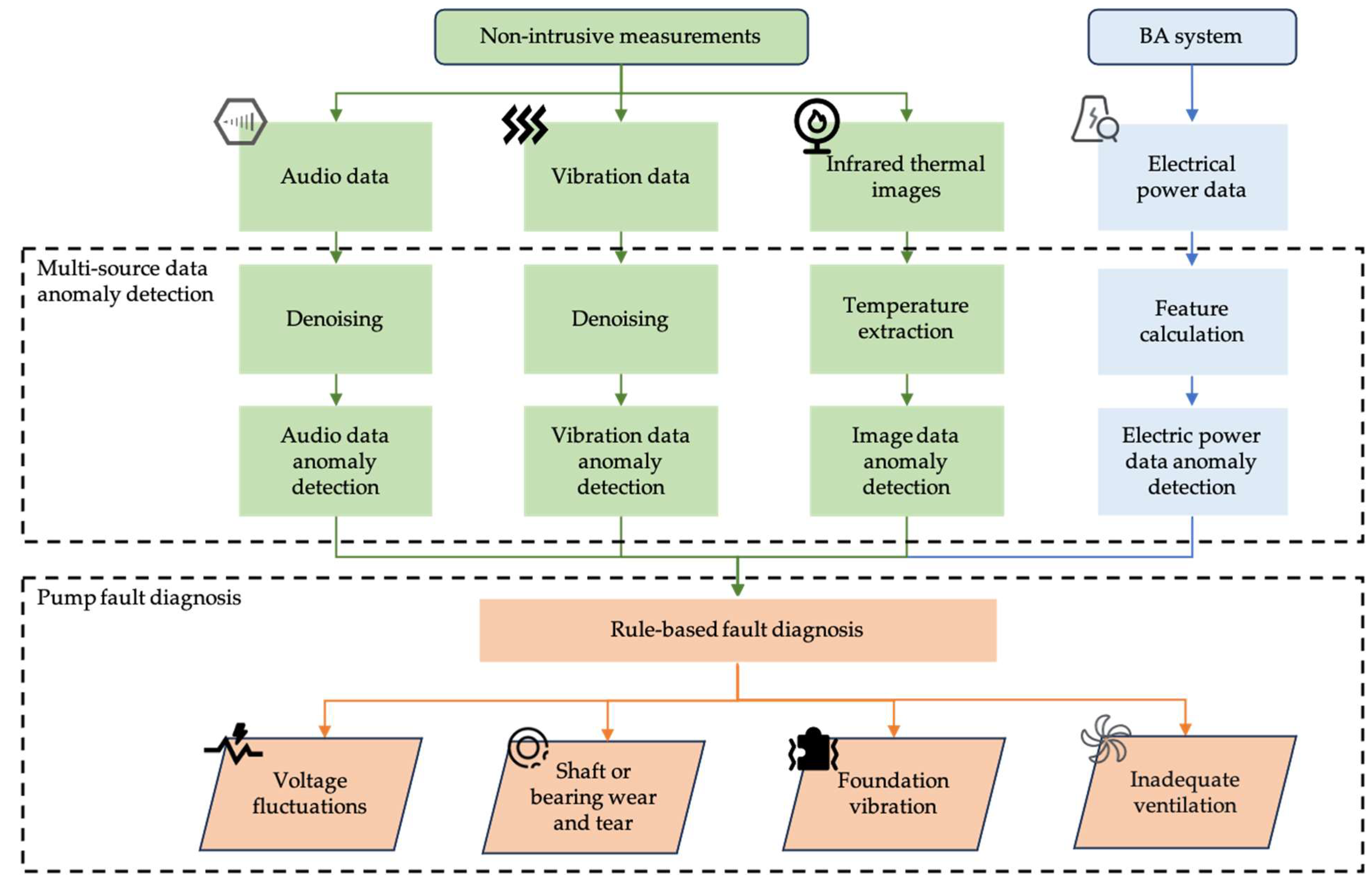

Figure 2 illustrates the process of the proposed multi-source data-driven FDD method, including anomaly detection for different source data and pump fault diagnosis.

Figure 2.

Process of multi-source data-driven FDD method.

2.2.1. Multi-Source Data Anomaly Detection

- Audio data anomaly detection

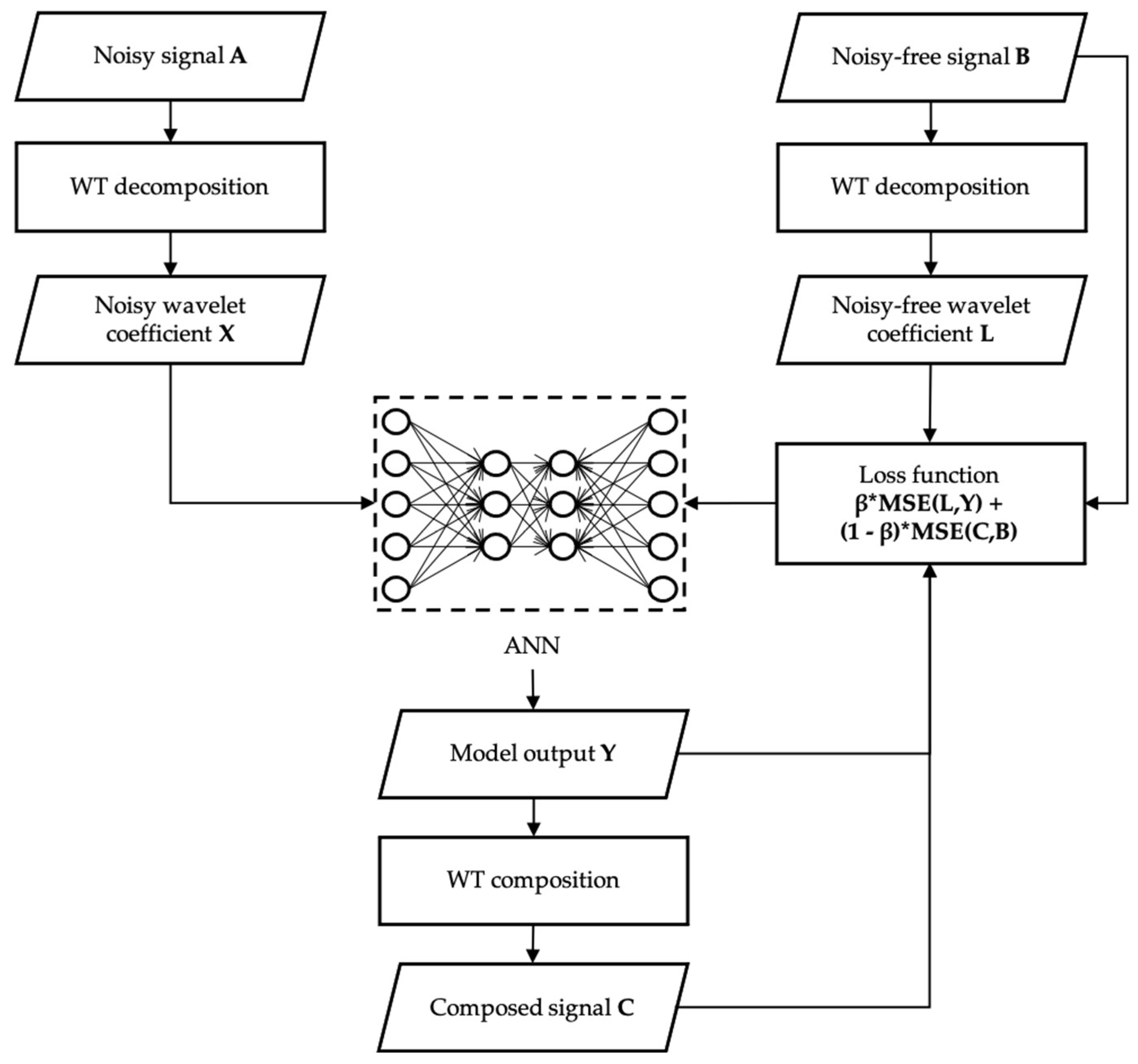

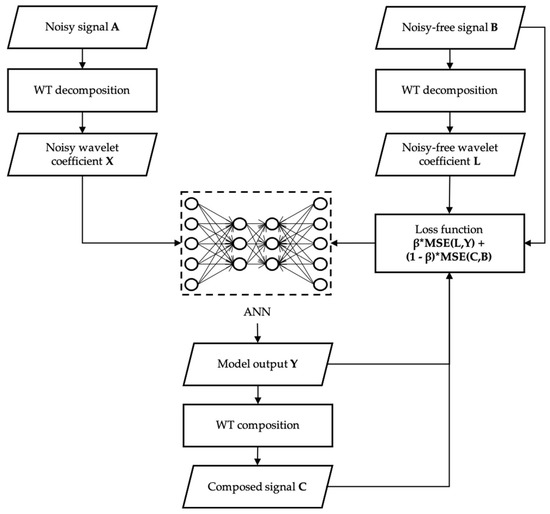

The audio data requires an initial denoising step to isolate the pump’s audio data from the background noise produced by other equipment in the plant room. The denoising process is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Denoising process of audio data.

In this paper, a WT-ANN (Wavelet Transform and Artificial Neural Network)-based process is proposed to denoise audio data. Firstly, both noisy and noise-free audio signals are decomposed by wavelet transform, yielding their respective wavelet coefficients, X and L. Then, wavelet coefficients X and L are applied to train an ANN model. The ANN model comprises two fully connected layers: a 1782 × 512 layer followed by a 512 × 256 layer, both utilizing the ReLU activation function. The loss function consists of two weighted components. The first component is the mean squared error (MSE) between the model output Y and the noise-free wavelet coefficient L. The second component is derived by first reconstructing signal C from the model output Y through an inverse wavelet transform, and then computing the MSE between this reconstructed signal C and the noise-free signal B. The final composite loss is the weighted sum of these two components.

The noisy signals are synthetically generated by mixing 100 segments of noise-free pump audio data with 50 segments of background noise at signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs) of 20, 15, 10, and 5 dB, resulting in a total of 20,000 input data segments. The dataset is split into training and testing sets in a 7:3 ratio, and the model is optimized using the Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) method. The data process is implemented in Python with the PyWavelets 0.2.2 package [27] for wavelet transform and the PyTorch 1.13.1 library [28] for ANN model training.

For a new noisy signal, it first undergoes wavelet decomposition to obtain its noisy coefficients. These coefficients are then fed into the trained model, whose output is subsequently reconstructed through an inverse wavelet transform to produce the denoised signal for downstream anomaly detection tasks.

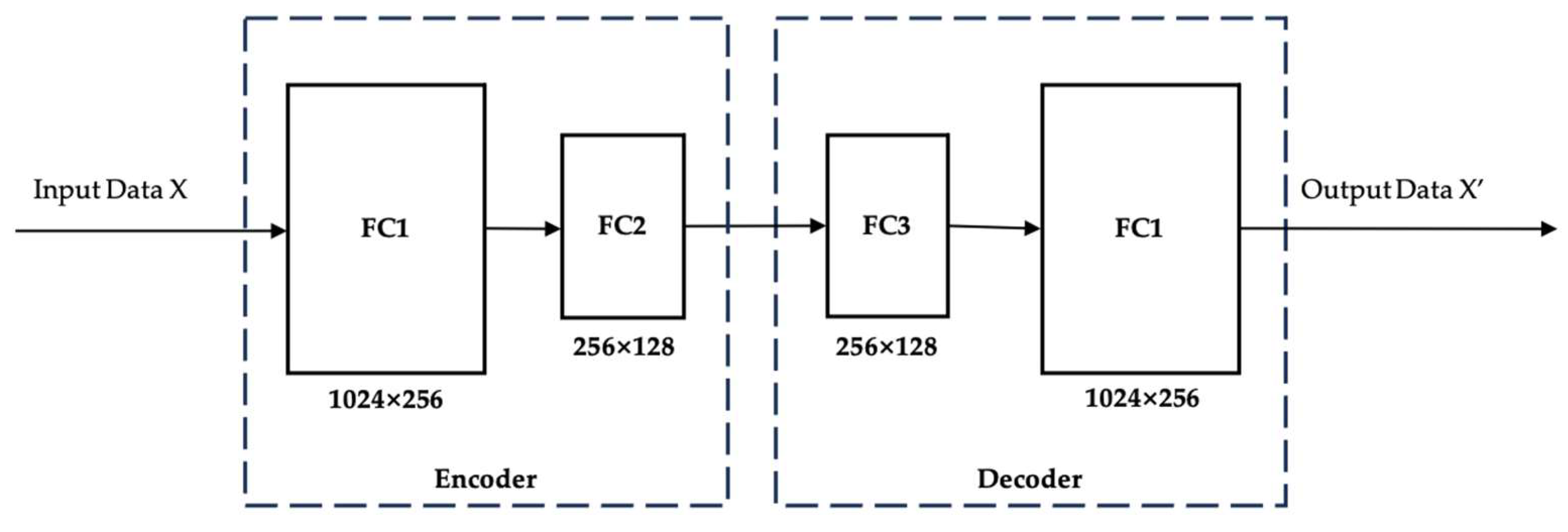

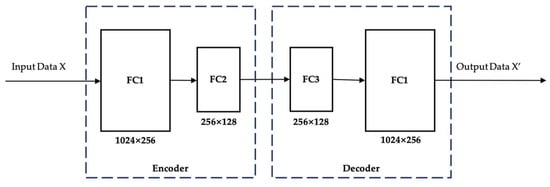

In practical operation, obtaining audio signals from pumps under abnormal conditions is challenging, resulting in a dataset comprised mainly of positive (normal) samples with very few negative (abnormal) samples. To address this data imbalance problem, an autoencoder is adopted as the anomaly detection model for audio signals. The autoencoder is particularly suitable for anomaly detection scenarios, with few or even zero negative samples [29]. For data conforming to a specific distribution, symmetrical networks are constructed to effectively extract the distributional features of this data (encoder) and use these features to reconstruct the input (decoder). Data that does not conform to this distribution cannot be reconstructed by the autoencoder accurately, thereby identifying as an anomaly.

Figure 4 shows the structure of the autoencoder applied in this paper. The encoder and decoder are symmetrically structured, each containing a 1024 × 256 fully connected layer and a 256 × 128 fully connected layer. The loss function is MSE, and the optimizer is Adam. Before training, all audio signals are preprocessed through discrete Fourier transform. The dataset comprises 274 positive samples and 834 negative samples. In total, 70% of the positive samples are used for training the autoencoder, while the remaining 30% of positive samples combined with all negative samples are reserved for testing model performance. PyTorch library [28] is used for autoencoder model training and testing. The boxplot method is applied for threshold calculation. Samples are flagged as anomalies if their MSE exceeds the threshold θ derived from the training positive data. The threshold θ is calculated using Equation (1):

where Q1 and Q3 are the first and third quartile of normal data. For this case, normal data are the MSE of training positive data.

θ = Q3 + 1.5 × (Q3 − Q1),

Figure 4.

Structure of autoencoder for audio data anomaly detection.

- 2.

- Vibration data anomaly detection

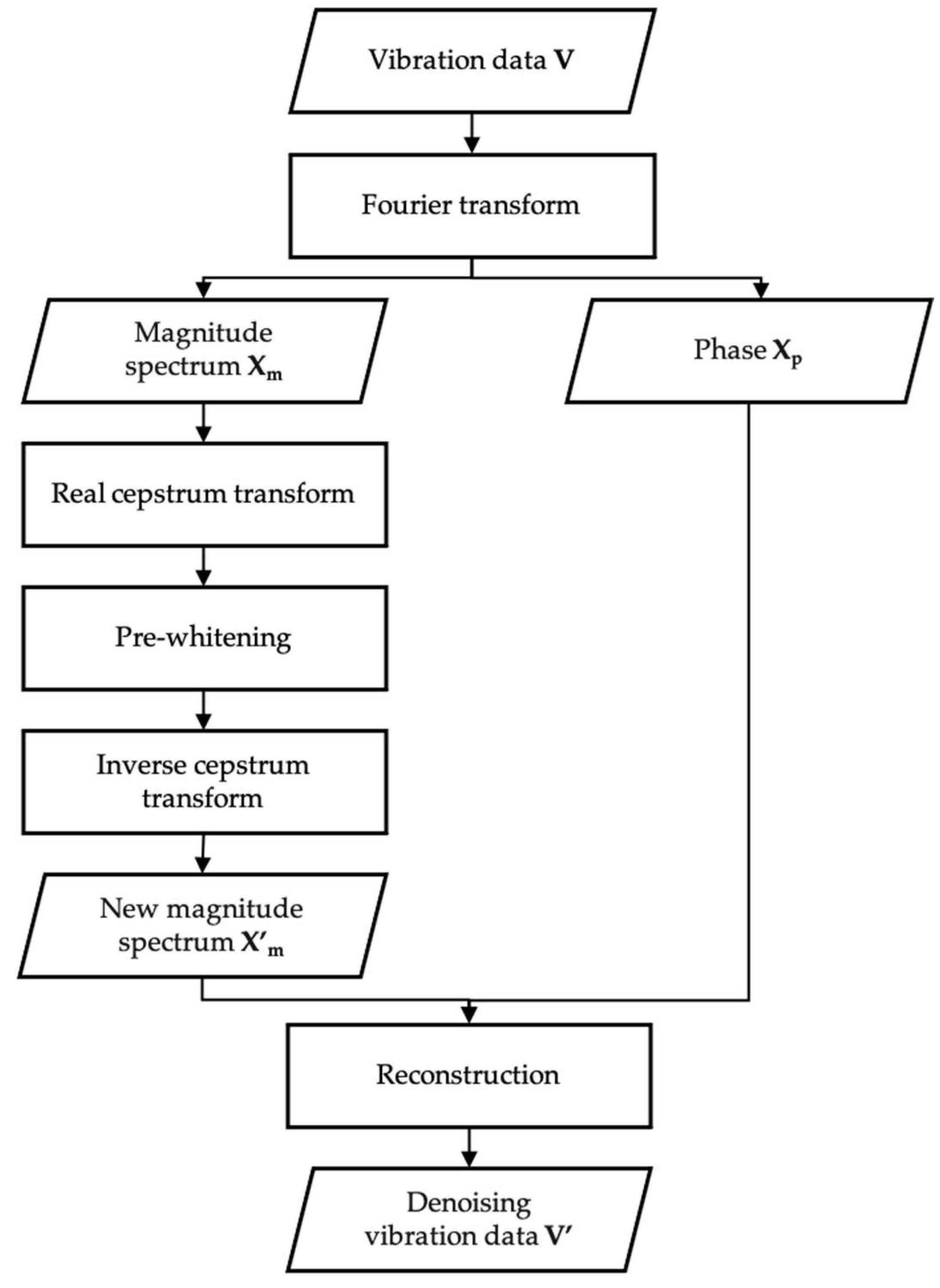

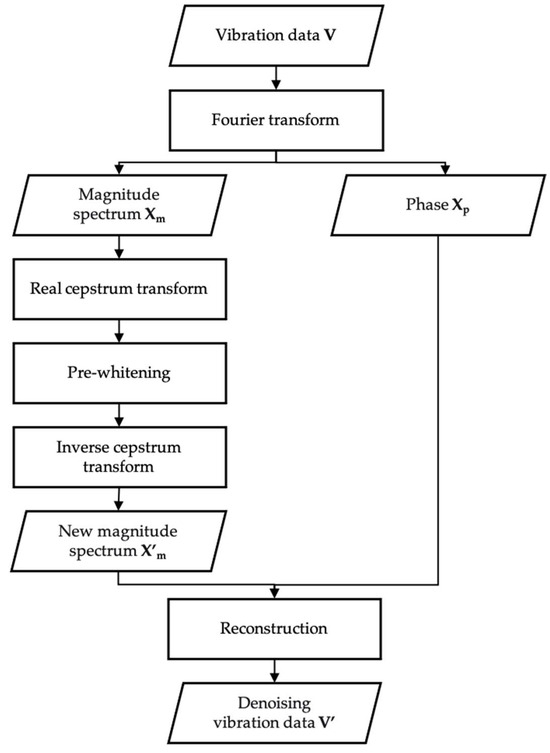

The vibration signals of pumps consist primarily of vibrations from the pump shaft, combined with vibrations from other equipment and random vibrations. In the frequency domain, the superposition of these signals is called harmonic modulation, resulting in numerous sidebands in the frequency spectrum. Consequently, denoising can be achieved by filtering out these sidebands in the frequency domain. The overall vibration signal denoising workflow based on cepstrum pre-whitening (CPW) is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Denoising process of vibration data based on CPW.

CPW is an effective method for extracting deterministic components from noisy vibration signals in mechanical systems [30]. The magnitude spectrum Xm and phase Xp can be obtained by Fourier transform of vibration data X. The real cepstrum C can be calculated using Equation (2):

where IFT indicate inverse Fourier transform. The pre-whitening operation sets a zero value for the whole real cepstrum, except possibly at zero quefrency. After inverse transform of Equation (1), the new magnitude spectrum X’m can be obtained and used to reconstruct the denoising data with the original phase Xp.

C = IFT(log(Xm)),

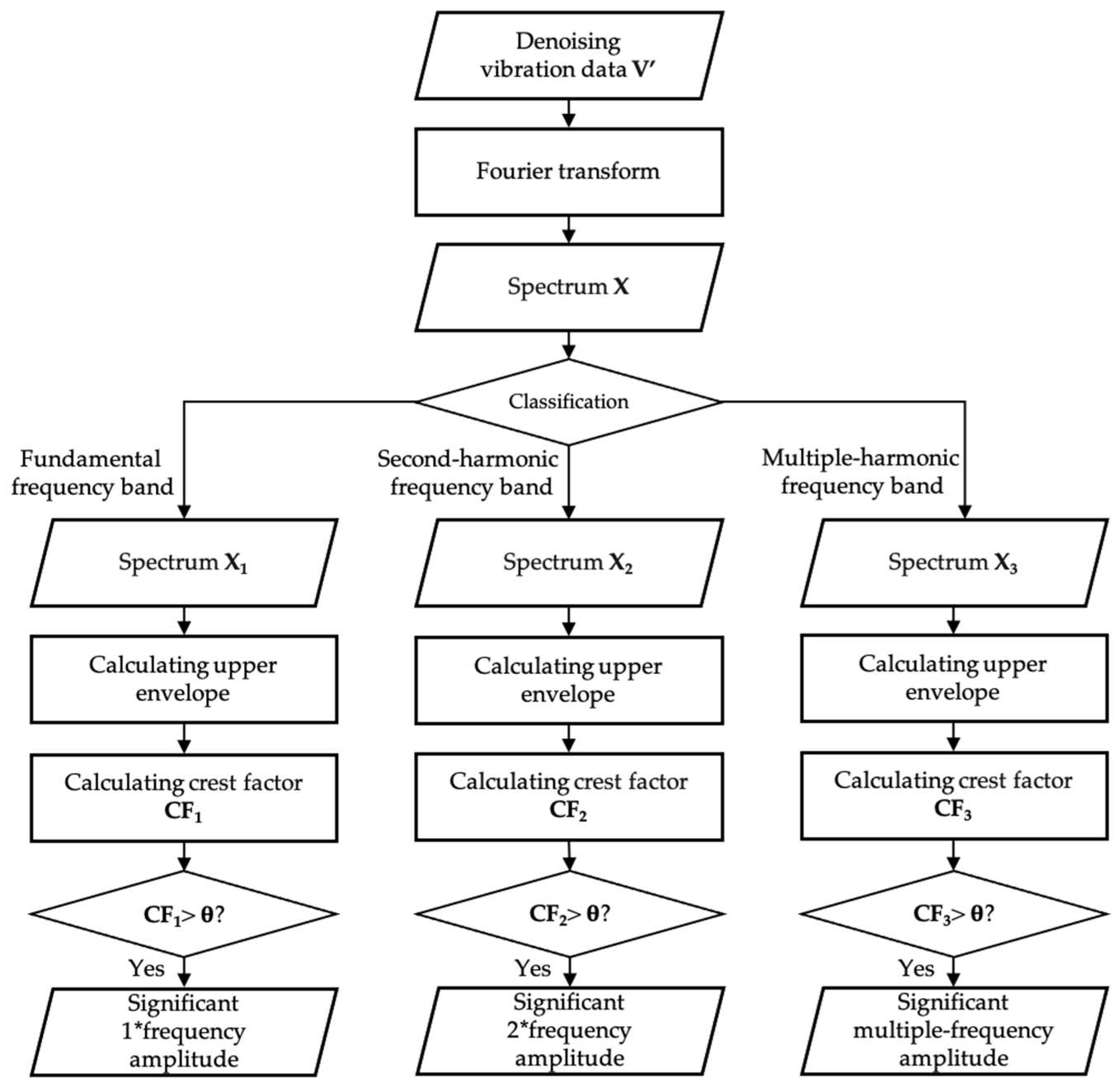

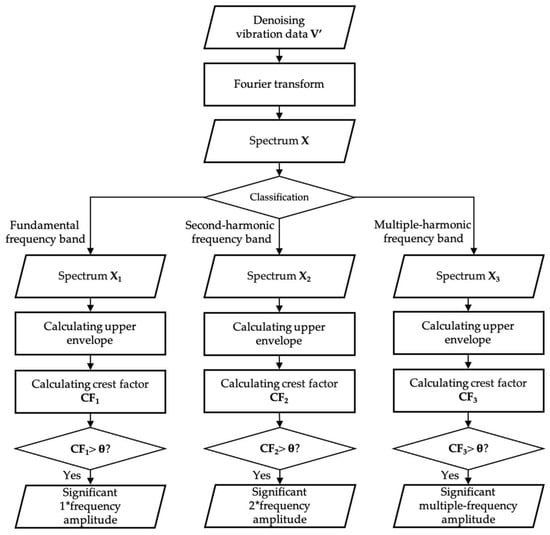

Mechanical faults in pumps would induce different features in the vibration spectrum. For instance, loose foundation causes significant peaks at the 1X (fundamental) and 3X (third harmonic) frequencies, and bearing or shaft wear and tear tends to generate multiple-harmonics in the spectrum [31,32]. Therefore, anomaly detection in pumps can be performed by analyzing the significant features of vibration data across different harmonic frequency bands.

Figure 6 shows the process of vibration data anomaly detection. After a Fourier transform, the vibration spectrum is partitioned into three sub-components, X1, X2, and X3, which represent the spectrum in fundamental, second-, and multiple-harmonic frequency band, respectively. The frequency ranges for these components are [0.5 × fbase, 1.5 × fbase] for X1, [1.5 × fbase, 2.5 × fbase] for X2, and [2.5 × fbase, +∞] for X3, where fbase represents the fundamental frequency. Each component undergoes sequential steps to identify significant amplitude anomalies. Firstly, the spectrum is simplified by calculating the upper envelope. Then, crest factor CF is calculated using Equation (3) to indicate the presence of transient peaks:

where xpeak is the peak value of data. CF values exceeding the threshold θ of normal data calculated by Equation (1) are flagged as significant amplitude increases.

Figure 6.

Process of vibration data anomaly detection.

- 3.

- Infrared thermal images anomaly detection

The temperature recognition method from infrared thermal images is proposed by our previous research [33]. First, the pump region is segmented from the infrared image by a trained AlexNet model. Second, the color bar is localized to establish a mapping relationship between RGB values and temperature readings. This enables the conversion of RGB values in the pump region to their corresponding temperature values. In this paper, the average temperature of the pump region is selected as temperature features. Temperature feature data exceeding the threshold θ, derived from normal data calculated by Equation (1), is identified as overheating.

- 4.

- Electrical power data anomaly detection

Relative power standard deviation pstd is used to evaluate the fluctuations of electrical power, which is calculated by Equation (4):

where pi is the i-th power data within the time window, and is the average power within the time window. In this paper, the time window is set to 5 min. pstd values exceeding the threshold θ of normal pstd data, calculated by Equation (1), are identified as excessive power fluctuations.

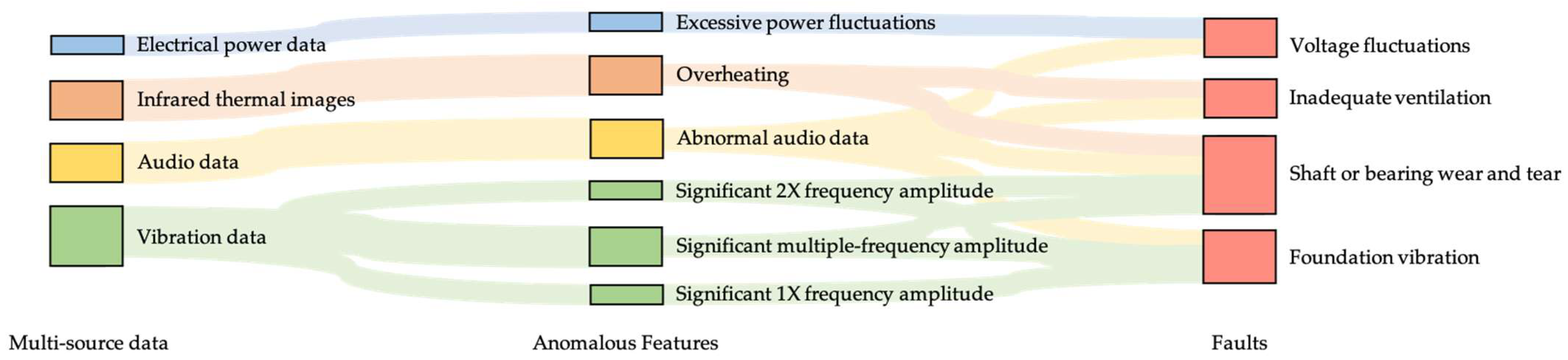

2.2.2. Pump Fault Diagnosis

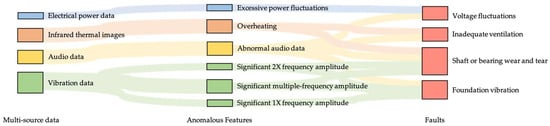

Different pump faults would cause different anomalies in certain indicator features. By applying these feature-to-fault rules, pump fault diagnosis can be achieved. Figure 7 displays the anomalous features and their data sources corresponding to different pump faults in the experiments conducted in this study.

Figure 7.

Pump fault diagnosis rules.

Voltage fluctuations would cause excessive power fluctuations. All faults would cause abnormal audio data. While both inadequate ventilation and shaft or bearing wear and tear result in overheating phenomena, inadequate ventilation does not typically produce significant double-frequency/multiple-frequency components in vibration data. Both shaft or bearing wear and tear and foundation vibration exhibit significant harmonic components in vibration data. However, in actual operation, foundation vibration rarely generates noticeable overheating.

2.3. Evaluation Method

In this paper, F1-score and accuracy are used to evaluate the proposed multi-source FDD method, which are calculated by Equation (5) and Equation (6), respectively:

where is the ratio . is the ratio of . , and are the numbers of true positives, false positives, and false negatives for category i, respectively. N is the total number of categories.

3. Results and Discussion

The results of multi-source data anomaly detection and pump fault diagnosis are presented and discussed in this section.

3.1. Results of Audio Data Anomaly Detection

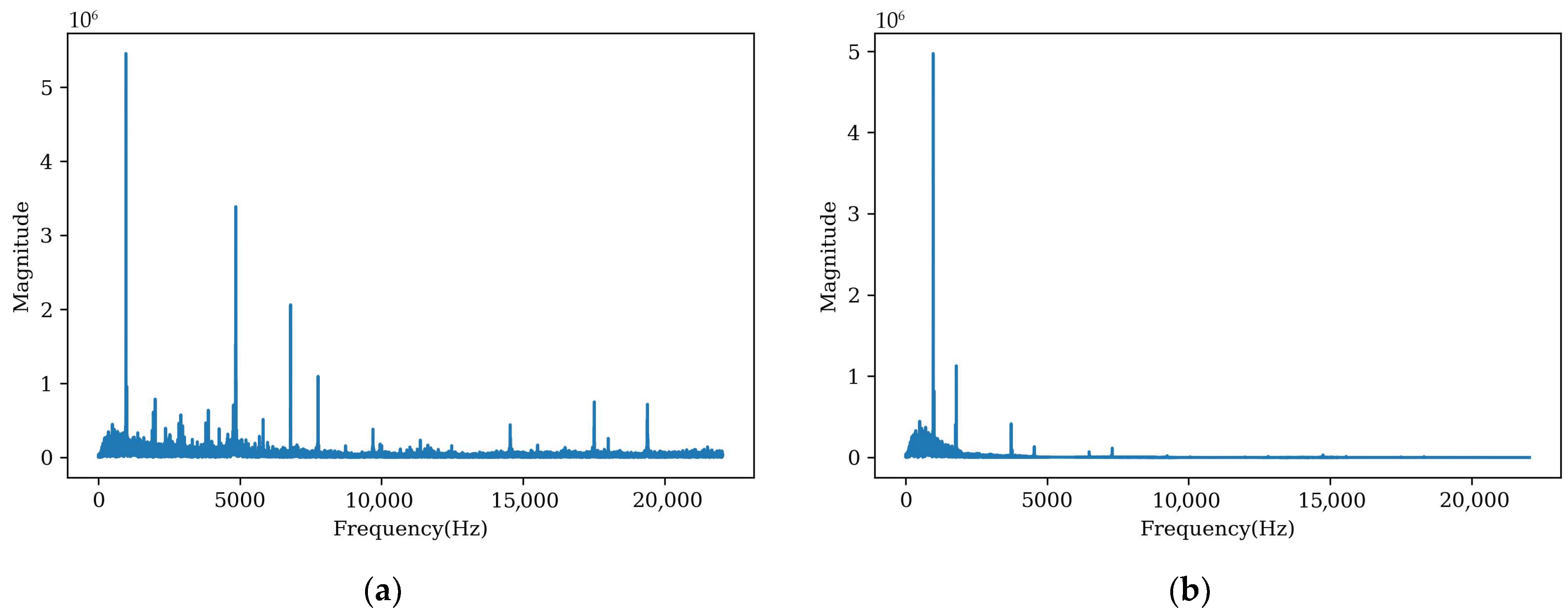

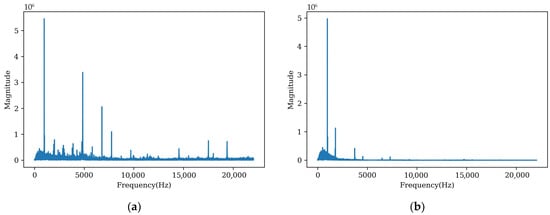

Figure 8 displays the spectrums of the audio data before and after denoising processing, which shows the effectiveness of the denoising procedure. The loss values of the proposed WT-ANN model on training dataset and test dataset are 0.032 and 0.043, respectively.

Figure 8.

The spectrums of the audio data before and after denoising processing. (a) Before denoising; (b) after denoising.

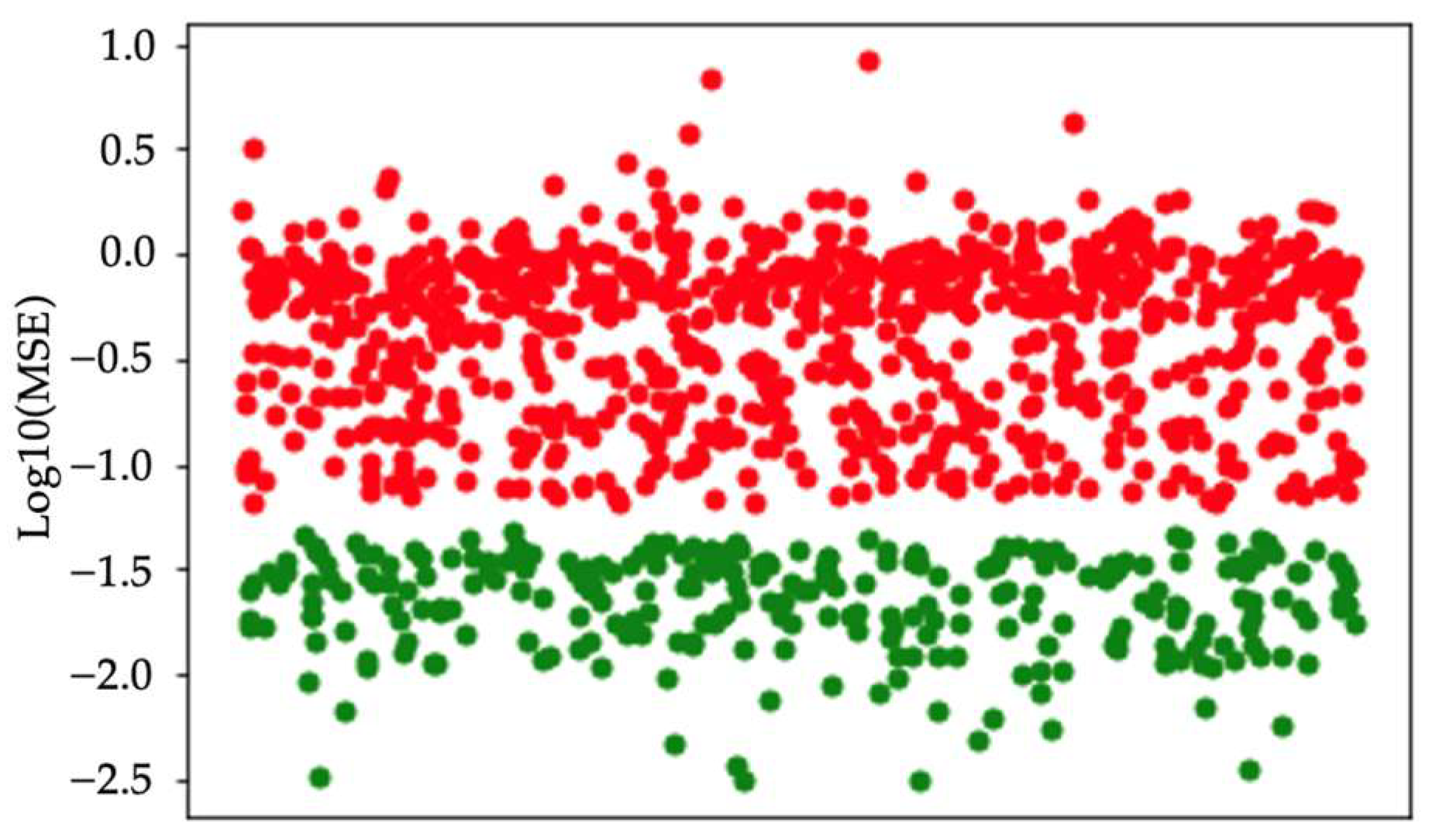

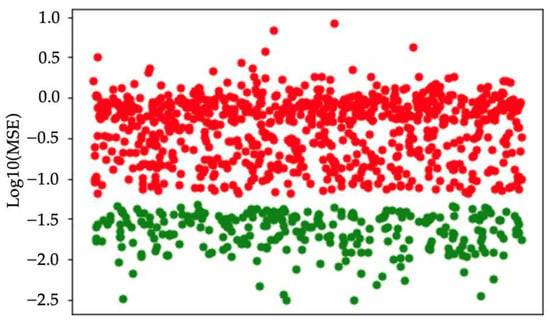

The autoencoder’s output is not a classification label but the reconstruction results from the decoder. MSE between the reconstructed output and the input data is used to distinguish positive and negative samples. Figure 9 presents the MSE results for both normal and anomalous audio data processed through the autoencoder.

Figure 9.

MSE results for both normal and anomalous audio data. Red dots denote negative samples, and green dots represent positive samples.

The vertical axis represents the base-10 logarithm of the MSE between output and input. Red dots denote negative samples, while green dots represent positive samples. A clear separation between these two classes demonstrates the autoencoder’s effectiveness in accurately distinguishing abnormal samples from normal samples. A threshold of −1.4304 (on the log10 scale) is selected as the anomaly criterion. With this threshold, the autoencoder achieves 100% accuracy in anomaly detection.

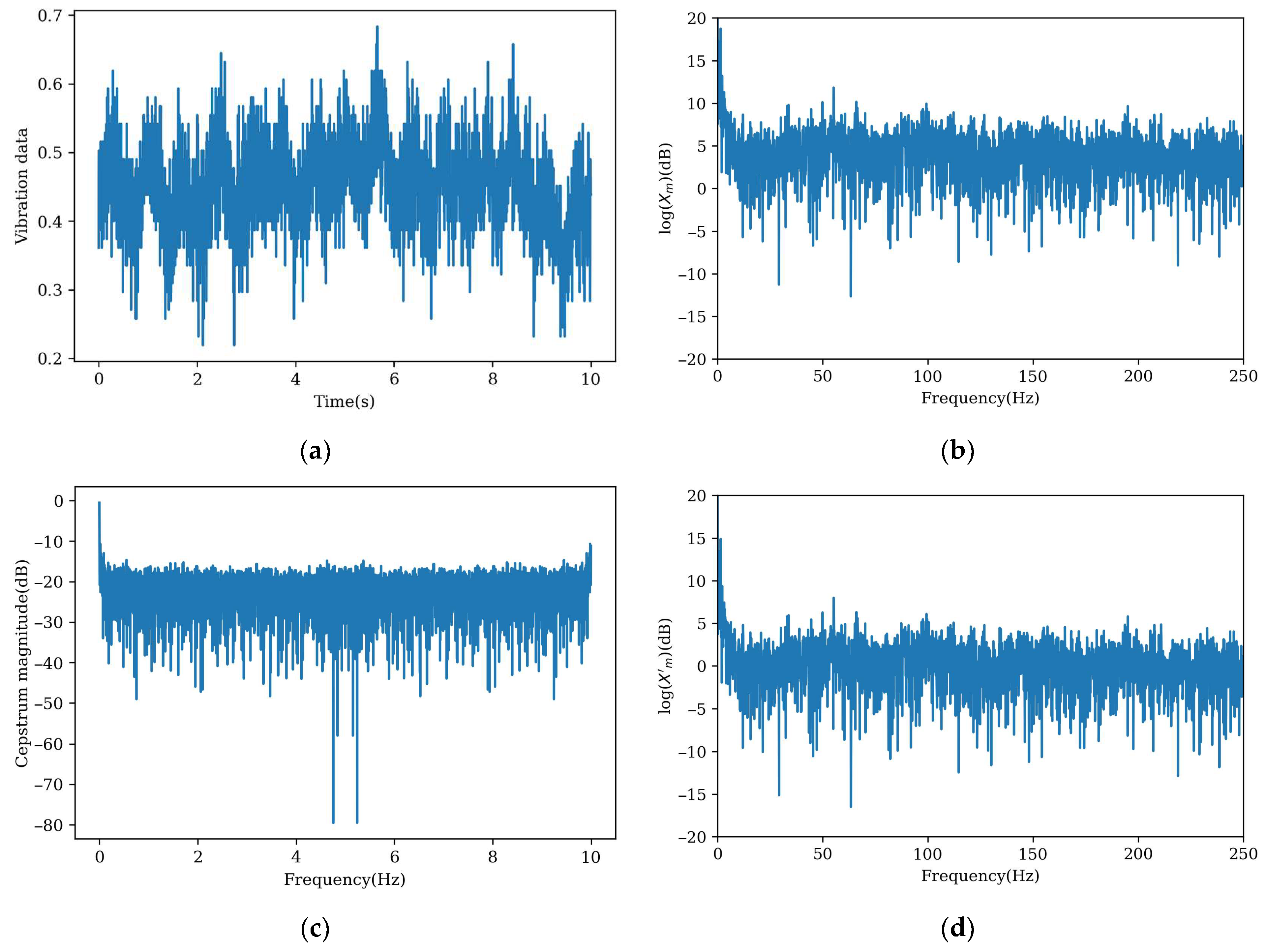

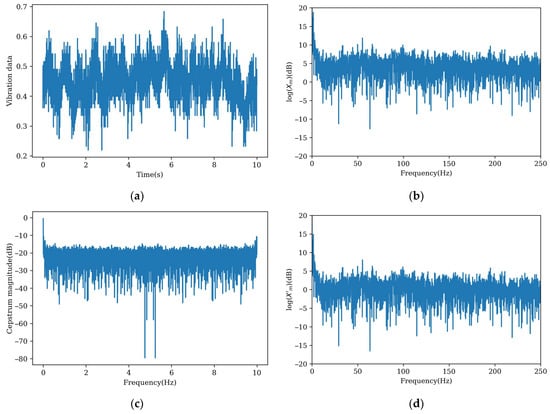

3.2. Results of Vibration Data Anomaly Detection

Figure 10 illustrates the vibration data denoising process. Subfigure (a) displays the original vibration waveform, (b) shows the logarithmic spectrum of original data (log(Xm), (c) presents the real cepstrum, and (d) demonstrates the logarithmic spectrum of denoising data after pre-whitening. The denoised spectrum exhibits an overall amplitude reduction while making some frequency components more obvious, particularly the 100 Hz and 200 Hz components, which become distinctly visible relative to other spectral elements. This result confirms that the CPW method effectively reduces noise by eliminating sideband frequencies.

Figure 10.

The vibration data denoising process. (a) Original waveform diagram; (b) logarithmic spectrum of original vibration data; (c) real cepstrum; (d) logarithmic amplitude spectrum of denoising data (log(X’m)).

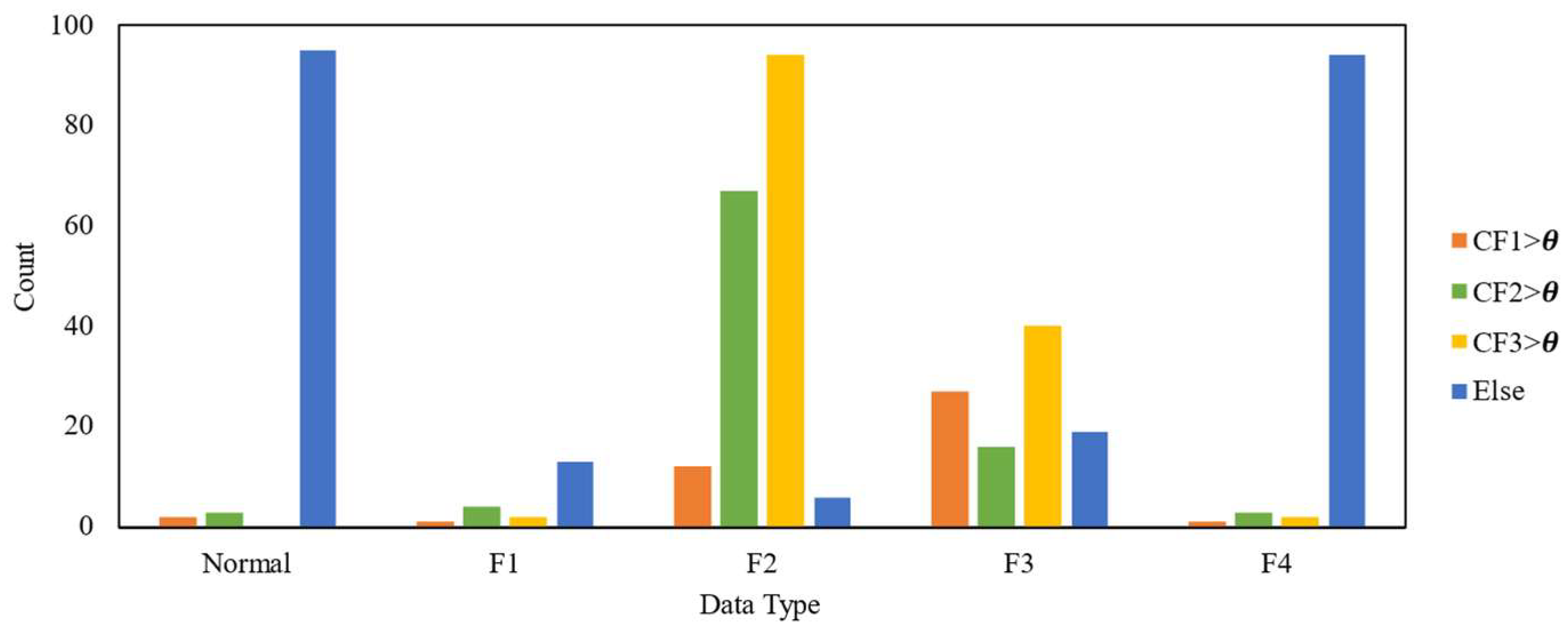

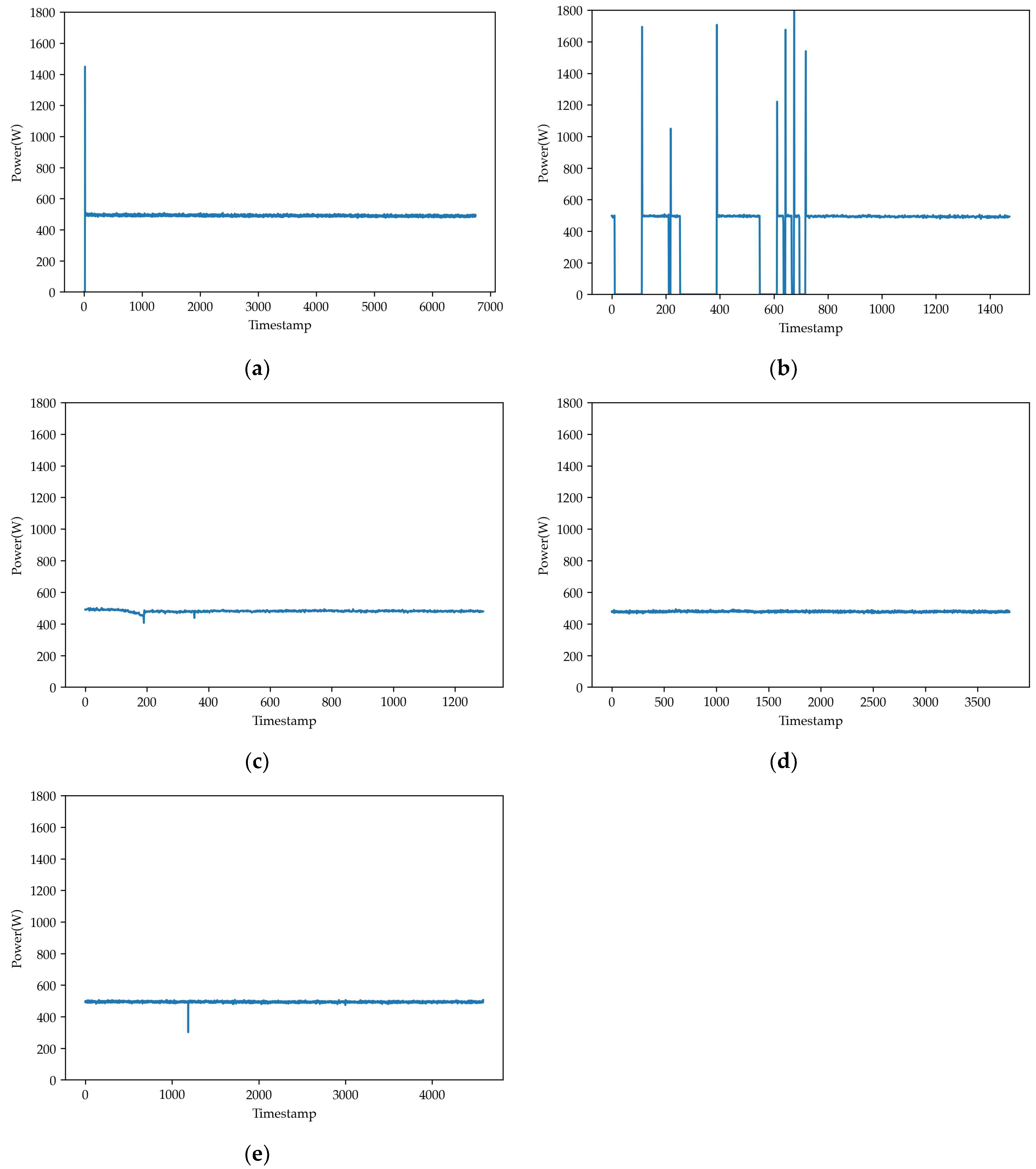

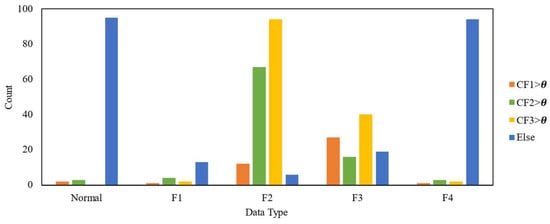

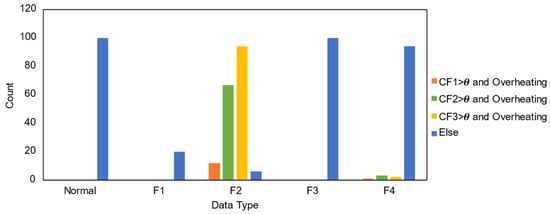

A total of 100 vibration data samples under normal conditions are collected, along with 20 samples of F1 faults, 100 samples of F2 faults, 100 samples of F3 faults, and 100 samples of F4 faults. Figure 11 shows the number of samples exhibiting significant features in the fundamental (CF1 > θ), second-harmonic (CF2 > θ), and multiple-harmonic frequency bands (CF3 > θ), as well as the number of samples without significant features in any of these bands (Else).

Figure 11.

The number of samples exhibiting significant features in different frequency bands.

For normal data, F1 (voltage fluctuation), and F4 (inadequate ventilation) faults, most samples show no significant features in the fundamental, second-harmonic, or multiple-harmonic bands. In contrast, for shaft or bearing wear and tear fault (F2), the numbers of samples with significant features in the fundamental, second-harmonic, and multiple-harmonic bands are 12, 67, and 94, respectively, indicating that shaft or bearing wear and tear faults are primarily characterized by second- and multiple- harmonics. For foundation vibration (F3), the corresponding numbers are 27, 16, and 40, suggesting that faults caused by foundation vibration present significant features throughout fundamental, second-, and multiple-harmonics, mainly existing in the fundamental and multiple-harmonic frequencies.

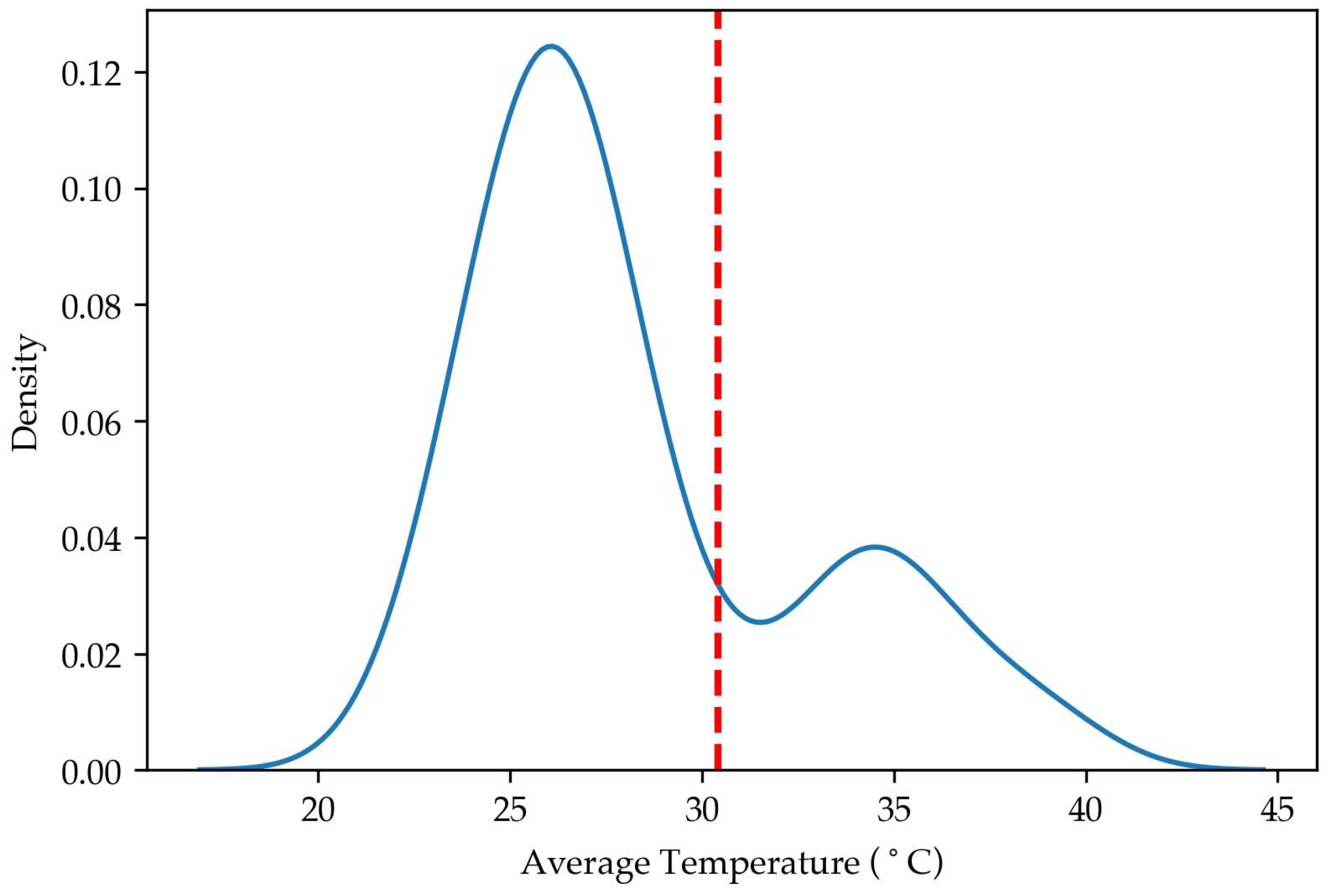

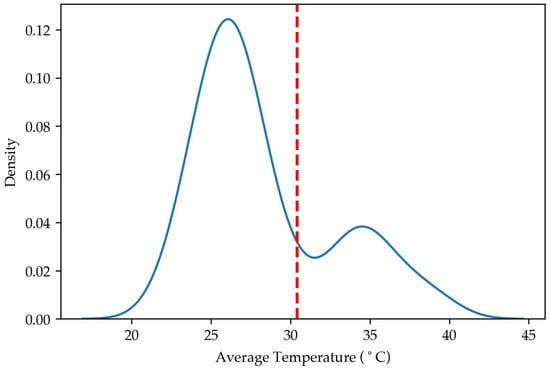

3.3. Results of Infrared Thermal Images Anomaly Detection

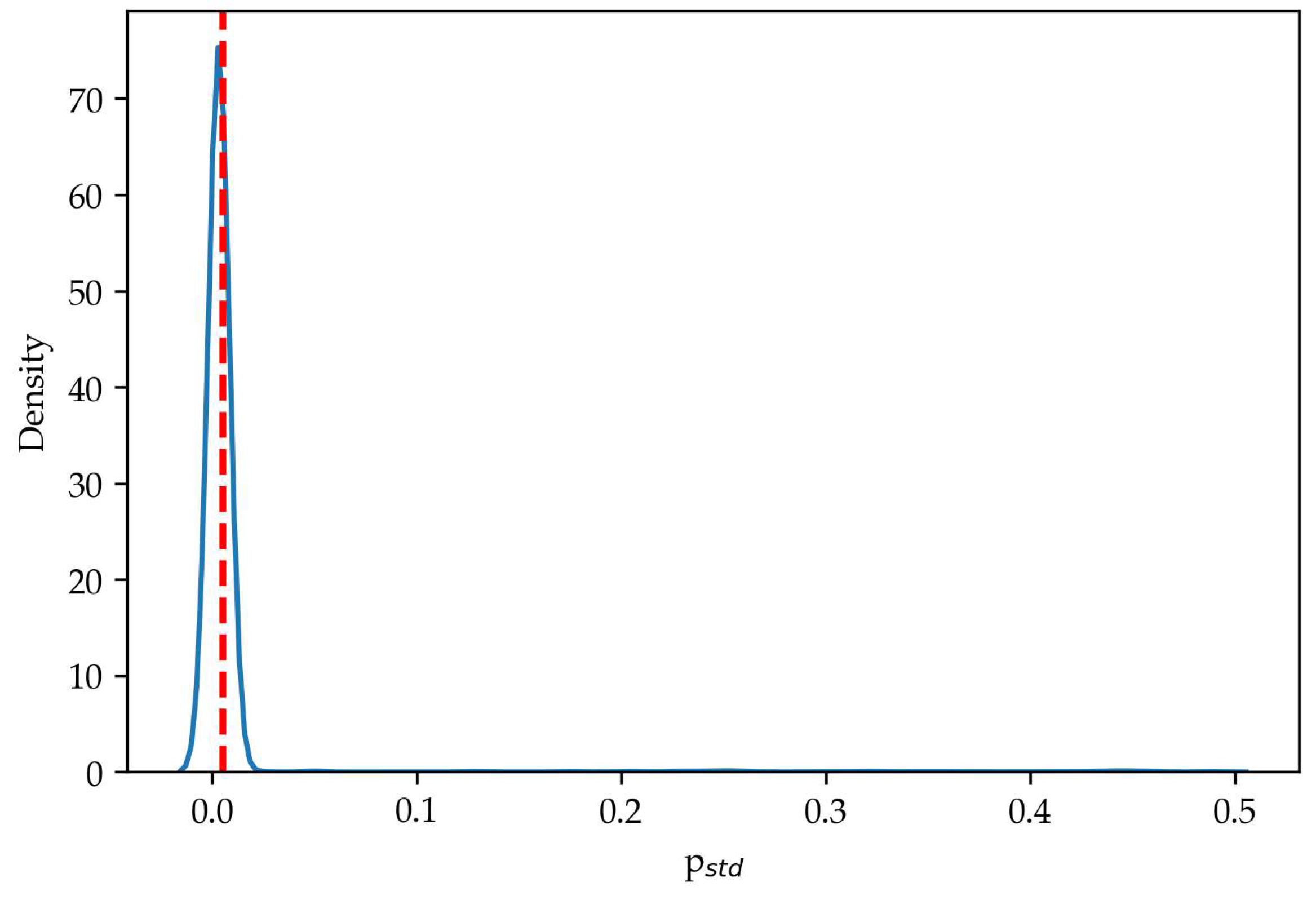

The number of infrared thermal images under normal condition, F1 faults, F2 faults, F3 faults, and F4 faults are 68, 20, 20, 20, 20, respectively. Only F2 and F3 faults would cause overheating. Figure 12 shows the distribution of average pump temperatures across all infrared thermal images. The red dashed line indicates the anomaly threshold at θ = 30.41 °C.

Figure 12.

The distribution of average temperature across all infrared thermal images.

All normal data samples are correctly classified, and all F4 faults are accurately diagnosed. For F2 faults, 17 samples are correctly identified as anomalies, while 3 samples are misclassified as normal. This misclassification occurs because a detectable temperature rise lags behind the initial faults, and the images captured during the initial stage of the fault do not yet exhibit significant temperature increase.

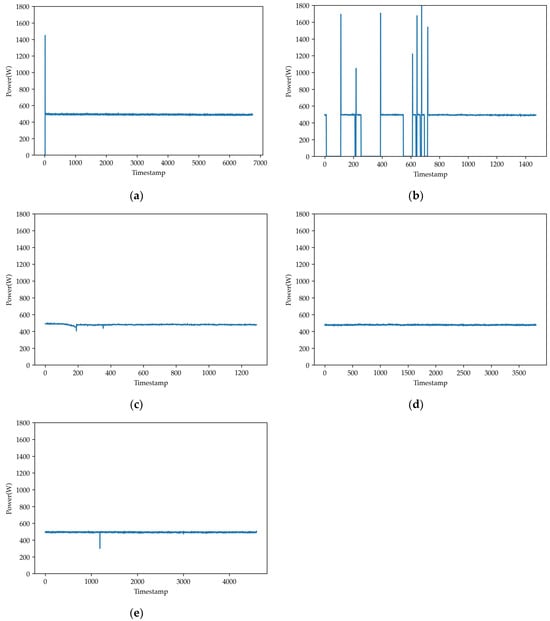

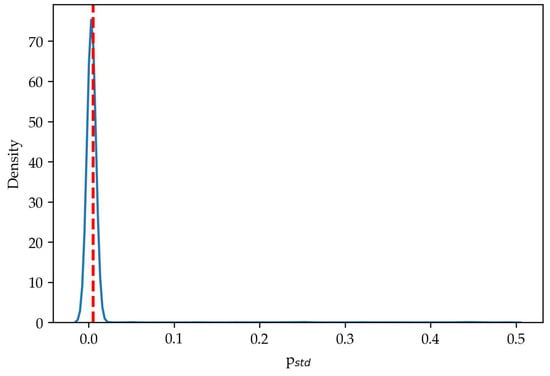

3.4. Results of Electrical Power Data Anomaly Detection

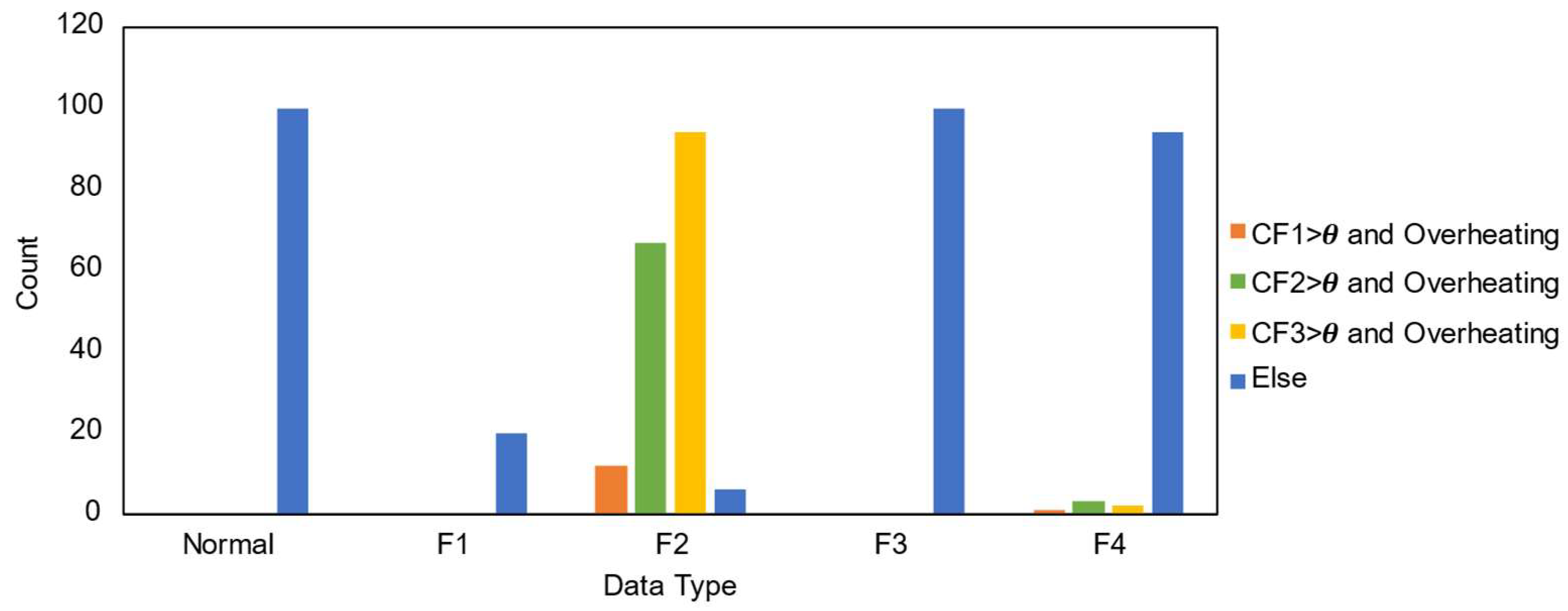

Figure 13 shows the electrical power of pumps under different conditions. During normal operation, the pump power maintains at approximately 500 W. In contrast, data from voltage fluctuation faults (shown in Figure 13b) show frequent and significant power fluctuations. Other fault types exhibit only occasional, minor power anomalies. It is noteworthy that under normal operating conditions, an obvious power transient appears during the startup phase, after which the power remains steady.

Figure 13.

The electrical power of pumps under different conditions. (a) Normal; (b) F1 fault; (c) F2 fault; (d) F3 fault; (e) F4 fault.

Figure 14 shows the distribution of relative power standard deviation pstd under different operation conditions. The red dashed line indicates the anomaly threshold at θ = 0.0055. The power anomalies across all scenarios are detected successfully. However, for some cases, power fluctuations occur occasionally. Thus, the frequency of pstd anomalies within a time window is chosen as the indicator for voltage fluctuation fault. Since the data collection frequency in this paper is 20 s and the time window for pstd calculation is set to 5 min, we define a voltage fluctuation fault as occurring when more than 45 pstd anomalies are detected within a 15 min period. For other applications, this threshold should be calibrated based on the data collection frequency and chosen time window.

Figure 14.

The probability density distribution of pstd under different operation conditions.

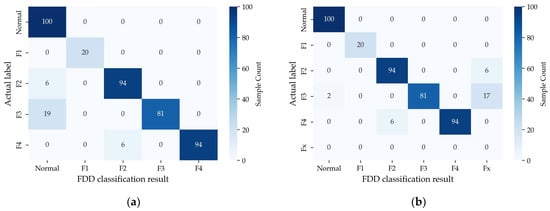

3.5. Results of Pump Fault Diagnosis

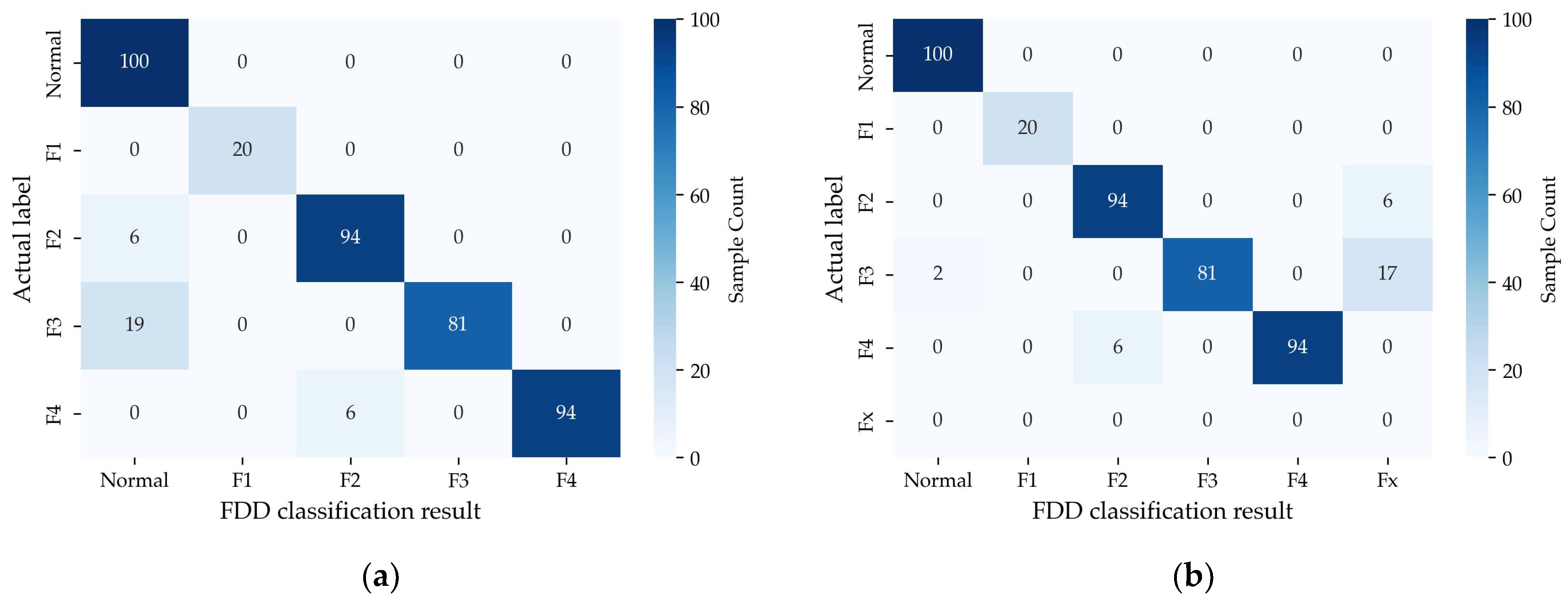

The voltage fluctuation fault in the experiment can be successfully diagnosed using the excessive power fluctuation indicator. However, distinguishing between shaft or bearing wear and tear (F2) and foundation vibration (F3) proves challenging based only on vibration data. F2 and inadequate ventilation (F4) cannot be identified exclusively from infrared images. By integrating vibration data with infrared thermal images, these three fault types can be effectively differentiated.

Figure 15 presents a statistical summary of vibration samples under different fault conditions, integrating both vibration anomaly indicators and overheating indicators. The results clearly show that, with the inclusion of the overheating indicator, only data under F2 fault condition continues to exhibit significant features within the harmonic frequency ranges. Thus, F2 and F3 faults can be distinguished by the overheating indicator, while the F2 and F4 faults can be differentiated through the vibration significance indicator.

Figure 15.

The number of vibration samples exhibiting overheating and significant features in different frequency bands.

Figure 16 shows the confusion matrices for different multi-source FDD classification results. Figure 16a presents the FDD classification results with electrical power, vibration, and infrared thermal data. The F1-scores for normal data, F1, F2, F3, and F4 faults are 0.89, 1, 0.94, 0.90, and 0.97, respectively, with an overall accuracy of 92.62%. Figure 16b incorporates additional audio data. The corresponding F1-scores are 0.99, 1, 0.94, 0.90, and 0.97, respectively, with the overall accuracy remaining at 92.62%. Since all fault types would cause abnormal audio data, data samples exhibiting only acoustic anomalies are categorized separately as unknown fault type Fx. Incorporating audio anomaly indicator prevents misclassification of faulty data as normal, which explains the increase in the F1-score for normal data to 0.99. For example, in Figure 16a, six F2 samples showed no anomalous indicators and would have been misclassified as normal, which poses higher risk in practical engineering than misclassifying normal data as faulty. As shown in Figure 16b, with the inclusion of the audio indicator, all F2 samples exhibit anomalies, eliminating false negative classifications and thereby reducing the risk of missed faults.

Figure 16.

The confusion matrices of different multi-source FDD classification results. (a) Electrical power data + vibration data + infrared thermal images; (b) electrical power data + vibration data + infrared thermal images + audio data.

4. Conclusions

Based on the practical engineering challenges of the lack of fault data and poor data quality, this paper proposes a novel FDD method for pumps based on multi-source data, which integrates traditional intrusive BA electrical power data with non-intrusive measurements, including audio data, vibration data, and infrared thermal images.

With our proposed muti-source pump FDD method, the F1-scores for normal data and F1, F2, F3, and F4 faults are 0.99, 1, 0.94, 0.90, and 0.97, respectively, and the overall accuracy is 92.62%. Electrical power data can effectively detect voltage fluctuations (F1 fault). Vibration data is suitable for identifying both F2 (shaft or bearing wear and tear) and F3 (foundation vibration) faults. However, distinguishing between F2 and F3 faults is challenging using model-free analysis of vibration data from a single measurement point. Infrared thermal data plays a critical role in pump fault detection, as it not only reliably identifies inadequate ventilation (F4 fault) but also helps differentiate between F2 and F3 faults when combined with vibration data. All four fault types in this experiment cause abnormal audio data. The incorporation of audio data effectively reduces the risk of fault samples being misclassified as normal samples.

The main contributions of this study are as follows:

- A two-step multi-source data-based method is proposed for pump fault diagnosis. The first step performs anomaly detection on each data type individually, followed by a rule-based fusion for comprehensive fault diagnosis. By analyzing anomaly indicators from different data sources, the proposed method reduces the risk of missed fault detection and demonstrates enhanced robustness. Unlike conventional FDD methods that require a lot of sensors or complex models to identify different fault types, which usually needs to retrain the model for a new case, our method can be directly deployed in new pump systems.

- The proposed method operates independently of fault data. The first step only requires detecting abnormal data from normal data, which is a binary classification task. Thus, the anomaly detection method is simple and only needs the normal operation data. In this paper, only audio anomaly detection utilizes an autoencoder model, while other types of data types use statistical threshold methods to identify abnormal data. This method is suitable for real operation cases without historical fault data.

- The integration of non-intrusive data (audio, infrared, and vibration) significantly reduces implementation costs. These data can be collected periodically by facility management people or inspection robots, which reduces the costs of sensor installation and maintenance.

The limitations of the proposed method are as follows:

- The current study only addresses four pump faults: voltage fluctuations, shaft or bearing wear and tear, foundation vibration, and inadequate ventilation. And the method is only tested on a vertical fixed-speed centrifugal pump. Other pump fault diagnoses require further experimental discussion and validation.

- This study only considers scenarios where the four fault types occur individually and does not address situations where multiple faults occur simultaneously.

- The use of infrared thermal images for overheating detection introduces an inherent detection delay, because thermal anomalies become visible in the images only after a fault has happened for some time. Practical applications must consider appropriate data collection frequencies.

In future work, more pump fault types and data requirements can be studied. For instance, segmenting infrared images into specific regions to identify overheating locations could help to locate the faulty component of pumps. Implementation and validation in real pump systems is the next phase of this research, with detailed analysis of abnormal indicators under varying control strategies.

Author Contributions

Methodology and Original Draft Writing, J.G.; Software and Investigation, H.L.; Data Curation and Validation, C.G.; Software and Visualization H.J.; Software and Writing—Review and Editing, W.L.; Supervision and Writing—Review and Editing, P.X.; Writing—Review and Editing, L.L.; Project Administration and Validation, K.C.; Validation and Resources L.Z.; Data Curation and Resources, R.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52161135202) and the Guangdong Key Laboratory of Thermal Energy Storage Technology for Buildings.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Kan Chen, Leqi Zhu and Renrong Ding were employed by the GD Midea Heating & Ventilating Equipment Co., Ltd. All the authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FDD | Fault detection and diagnosis |

| BA | Building automation |

| CAE | Convolutional autoencoder |

| ANN | Artificial neural network |

| CEEMDAN | Complete ensemble empirical mode decomposition with adaptive noise |

| SVD | Singular value decomposition |

| BPNN | Back propagation neural network |

| WGAN-GP | Wasserstein generative adversarial network with gradient penalty |

| EMD | Empirical mode decomposition |

| GRNN | Generalized regression neural network |

| PCA | Principal components analysis |

| KPCA | Kernel principal components analysis |

| PSO | Particle swarm optimization |

| WT | Wavelet transform |

| MSE | Mean squared error |

| CPW | Cepstrum pre-whitening |

References

- United Nations Environment Programme. Accelerating the Global Adoption of Energy-Efficient Electric Motor Systems–Policy Guide; United Nations Environment Programme’s United for Efficiency: Nairobi, Kenya, 2025; ISBN 978-92-807-4216-9. [Google Scholar]

- Cieślicki, R.; Karpenko, M. An investigation of the impact of pump deformations on circumferential gap height as a factor influencing volumetric efficiency of external gear pumps. Transport 2022, 37, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, D.; Lu, W.; Xu, B.; Xu, L.; Lu, L. Study of Energy Loss Characteristics of a Shaft Tubular Pump Device Based on the Entropy Production Method. Entropy 2023, 25, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orosnjak, M. Maintenance Practice Performance Assessment of Hydraulic Machinery: West Balkan Meta-Statistics and Energy-Based Maintenance Paradigm. In Proceedings of the 2021 5th International Conference on System Reliability and Safety (ICSRS), Palermo, Italy, 24 November 2021; pp. 108–114. [Google Scholar]

- Orošnjak, M.; Brkljač, N.; Šević, D.; Čavić, M.; Oros, D.; Penčić, M. From Predictive to Energy-Based Maintenance Paradigm: Achieving Cleaner Production through Functional-Productiveness. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 408, 137177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapur, J.S.; Tiwari, R. Experimental Fault Diagnosis for Known and Unseen Operating Conditions of Centrifugal Pumps Using MSVM and WPT Based Analyses. Measurement 2019, 147, 106809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ding, L.; Xiao, J.; Fang, G.; Li, J. Current Status and Applications for Hydraulic Pump Fault Diagnosis: A Review. Sensors 2022, 22, 9714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosato, A.; Piscitelli, M.S.; Capozzoli, A. Data-Driven Fault Detection and Diagnosis: Research and Applications for HVAC Systems in Buildings. Energies 2023, 16, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, H.; Braun, J.E. Development of Fault Models for Hybrid Fault Detection and Diagnostics Algorithm; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, B.; Zhu, R.S.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, Y.R.; Fu, Q.; Wang, X.L. Fault Diagnosis of Horizontal Centrifugal Pump Orifice Ring Wear and Blade Fracture Based on Complete Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition with Adaptive Noise-Singular Value Decomposition Algorithm. J. Vib. Control 2024, 30, 5228–5236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosvirin, A.E.; Ahmad, Z.; Kim, J.-M. Global and Local Feature Extraction Using a Convolutional Autoencoder and Neural Networks for Diagnosing Centrifugal Pump Mechanical Faults. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 65838–65854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Chu, L.; Sun, Q.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Fault Identification of Centrifugal Pump Using WGAN-GP Method with Unbalanced Datasets Based on Kinematics Simulation and Experimental Case. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2024, 35, 096108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Xu, Y.; Gao, S.; Zhang, K.; Lin, Z.; Xia, T. Improved Center Loss-Based Metric Learning for Fault Diagnosis of Water Injection Pump. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2853, 012065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, W.; Ahmad, Z.; Siddique, M.F.; Ullah, N.; Kim, J.-M. Centrifugal Pump Fault Diagnosis Based on a Novel SobelEdge Scalogram and CNN. Sensors 2023, 23, 5255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, R.; Attaran, B.; Hajnayeb, A.; Ghanbarzadeh, A.; Changizian, M. Improving Accuracy of Cavitation Severity Detection in Centrifugal Pumps Using a Hybrid Feature Selection Technique. Measurement 2017, 108, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, A.K.; Rapur, J.S.; Tiwari, R. Prediction of Flow Blockages and Impending Cavitation in Centrifugal Pumps Using Support Vector Machine (SVM) Algorithms Based on Vibration Measurements. Measurement 2018, 130, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Ding, L.; Jiang, W. Study on Application of Principal Component Analysis to Fault Detection in Hydraulic Pump. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Fluid Power and Mechatronics, Beijing, China, 17–20 August 2011; pp. 173–178. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Meng, Y.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, S. Kernel Principal Component Analysis Fault Diagnosis Method Based on Sound Signal Processing and Its Application in Hydraulic Pump. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Fluid Power and Mechatronics, Beijing, China, 17–20 August 2011; pp. 98–101. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, G.; Tang, S.; Wang, R.; Su, H.; Wang, C. Acoustic Signal-Based Fault Detection of Hydraulic Piston Pump Using a Particle Swarm Optimization Enhancement CNN. Appl. Acoust. 2022, 192, 108718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Zhu, Y.; Yuan, S. An Adaptive Deep Learning Model towards Fault Diagnosis of Hydraulic Piston Pump Using Pressure Signal. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 138, 106300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Zhu, Y.; Yuan, S. An Improved Convolutional Neural Network with an Adaptable Learning Rate towards Multi-Signal Fault Diagnosis of Hydraulic Piston Pump. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2021, 50, 101406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, H. Layered Clustering Multi-Fault Diagnosis for Hydraulic Piston Pump. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2013, 36, 487–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Wang, S.; Wang, X. A Multi-Source Information Fusion Fault Diagnosis for Aviation Hydraulic Pump Based on the New Evidence Similarity Distance. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2017, 71, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, D.A.; Martins, G.S.O.; David, E.R.; Reis, F.L.M.; Carneiro, L.E.M.; Correia, J.R.; Lima, L.M.; Silva Freire, A.P. Fault Diagnosis of Electric Submersible Pumps Using Vibration Signals. J Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2023, 45, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Ma, X.; Nie, Z.; Cheng, W.; Xing, J.; Zhang, L.; Hong, J.; Xu, Z.; Chen, X. Integration of Multi-Relational Graph Oriented Fault Diagnosis Method for Nuclear Power Circulating Water Pumps. Measurement 2025, 242, 115811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Gommers, R.; Waselewski, F.; Wohlfahrt, K.; O’Leary, A. PyWavelets: A Python Package for Wavelet Analysis. JOSS 2019, 4, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. PyTorch: An Imperative Style, High-Performance Deep Learning Library. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.01703. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton, G.E.; Salakhutdinov, R.R. Reducing the Dimensionality of Data with Neural Networks. Science 2006, 313, 504–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghesani, P.; Pennacchi, P.; Randall, R.B.; Sawalhi, N.; Ricci, R. Application of Cepstrum Pre-Whitening for the Diagnosis of Bearing Faults under Variable Speed Conditions. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2013, 36, 370–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Analysis of Pump Vibration and Research on Vibration Reduction. Master’s Thesis, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.Q. Study on Fault Diagnosis of Water Pump in Long Pressure Water Supply System—Mechanical and Hydraulic Vibration Fault Diagnosis. Master’s Thesis, North China University of Water Resources and Electric Power, Zhengzhou, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- He, R.; Xu, P.; Chen, Z.; Luo, W.; Su, Z.; Mao, J. A Non-Intrusive Approach for Fault Detection and Diagnosis of Water Distribution Systems Based on Image Sensors, Audio Sensors and an Inspection Robot. Energy Build. 2021, 243, 110967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).