Abstract

To explore the potential of solar energy in the pursuit of a more sustainable aviation sector, this research examines the feasibility of solar photovoltaic systems for battery recharge of electric or electric hybrid aircraft deployed at four airports in North Africa and North, Central, and South Europe, respectively: Cairo International, London Heathrow, Milan Malpensa, and Rome Fiumicino. Employing PVGIS software with Google Maps, a site-specific photovoltaic array can be designed, optimizing module tilt and orientation to maximize solar energy collection across various climatic conditions. The energy production of the photovoltaic systems at the selected airports is compared to the energy demand required for the annual recharge of the batteries (28 MWh each) used in a widely popular medium-range aircraft, the Airbus A320. Although the calculated amount of energy, allowing for daily capacities ranging from 6 to 10 batteries on average, is insufficient to support the extensive demand associated with the typical air traffic in such airports, the potential of solar energy to decarbonize aircraft seems an appropriate approach to be pursued. Locations with limited solar access necessitate hybrid solutions, especially in sunny regions.

1. Introduction

The very large consumption of fossil fuels in aeronautics causes environmental damage and impacts climate change [1,2]. These effects emphasize the need to rethink our energy choices in such a sector. Global warming, pollution, and the depletion of fossil fuels have necessitated that all stakeholders prioritize renewable energy sources, such as photovoltaics (PVs), wind energy, and biofuels, as sustainable alternatives [3,4,5]. Each energy source possesses unique requirements and benefits. Besides their technical benefits, almost all of them have very low global warming emissions [6]. In comparison to natural gas, which releases 0.27 to 0.91 kg of CO2E/kWh, wind energy releases just 0.009 to 0.018 kg of CO2E/kWh, while solar PV releases only 0.032 to 0.091 kg of CO2E/kWh [7]. Among all renewable energy sources, solar photovoltaic could be an appropriate, although partial, option for airports. Ample land areas are accessible at airports, offering a secure and sheltered location for the building of a solar PV system [8,9]. A photovoltaic module with a power output of 100 Wp occupies an area of roughly one square meter; hence, a substantial area is required for considerable energy generation [1].

However, airport PV installations must verify that panels are outside airport design forbidden zones and that solar facilities will not impede radar communications [10]. Moreover, to increase electrical energy output, solar panels use glass to increase light absorption. To consider the serious issue of glare, solar panels are normally constructed of dark-colored, light-absorbing material covered with anti-reflection coating. A solar panel coated with Brisbane Materials Technology (BMT) reflects less than 1% of sunlight [3].

A wide range of airports across the globe have implemented extensive solar PV systems to meet part or all of their electricity needs. Notable examples include Cochin (the first airport in the world to run entirely on solar power) [11], Galápagos Ecological Airport [12], Rome Fiumicino (22 MWp, currently Europe’s largest airport PV plant) [13], Delhi (the first Indian airport to run entirely on hydro + solar) [14], Bologna Guglielmo Marconi (rooftop and parking installations) [15], and Fresno Yosemite International (the first airport in the United States to have a car park project) [16]. In light of the expanding research in this area, it is noteworthy that the majority of current studies concentrate solely on the application of airport photovoltaic systems to meet the energy demands of terminal buildings, HVAC systems, lighting, and ground services [17,18,19]. In arid regions like the Middle East and Iran, advanced hybrid wind–solar systems have the capability to fully power airports. These systems harness wind energy during cloudy conditions and solar energy when sunlight is abundant, effectively lowering carbon emissions and fostering sustainability [17]. National assessments utilizing GIS tools reveal considerable photovoltaic potential at civil airports in China, identifying 239 facilities that could generate up to 2.50 GW to fulfill aviation electricity needs across eight provinces. Additionally, these findings suggest profitable economic models for stakeholders through the strategic optimization of installations on terminals and parking lots [18]. Optimization models demonstrate that renewable sources, such as solar, geothermal, and biomass, have the potential to meet the majority, if not all, of an airport’s energy needs, including heating, cooling, and lighting. These sources exceed lignite and natural gas in terms of reliability and emissions, while also addressing the growing energy demand in regions with untapped potential [19].

Scarce peer-reviewed studies are available that quantitatively assess the feasibility of utilizing on-airport solar generation for the direct recharging of batteries for upcoming electric or hybrid electric aircraft operating from the same airport. This is an essential consideration, especially as certified all-electric aircraft, such as the Pipistrel Velis Electro, along with regional hybrid electric designs, are anticipated to enter the commercial market between 2026 and 2035. These aircraft will necessitate the establishment of megawatt-scale charging infrastructure at gates or remote stands [20,21,22].

The use of solar energy requires addressing several issues, such as the source intermittence, the collective influence of non-south terminal azimuths, the practical panel inter-row winter shading, and the glare limitations. All these aspects that limit the potential photovoltaic yield and aircraft charging efficiency have yet to be systematically analyzed across different latitudes and climates.

Renewable energy may not always be available, especially at night and in some areas during certain seasons. The best production window is constrained to the central hours of the day, approximately between 10:00 a.m. and 2:00 p.m. The primary element influencing the variation is the seasonal climatic conditions of summer and winter, e.g., the winter season in the Northern Hemisphere in countries like Sweden or Norway.

Electric or hybrid aircraft may serve as a viable means of reducing fossil fuel use and decarbonizing the aviation industry. However, the issue of recharging the battery systems of such types of aircraft must be considered. One possible approach to obtain at least part of the energy for recharging the onboard aircraft batteries is with renewable energy and specifically that generated by PV systems. To use solar energy, one suggested technology is the establishment of photovoltaic fields in suitable areas, such as airport rooftops or other facilities like parking lots.

This paper proposes a methodological approach to study the feasibility at different latitudes of the installation of green energy sources from the perspective of the introduction of electrical aircraft. In fact, the future spreading of electrical aircraft will increase the demand for electrical energy. This way, in order to preserve the green trend of future aviation, it is highly recommended for future airports to introduce green energy sources, such as PV plants, in order to have locally produced energy.

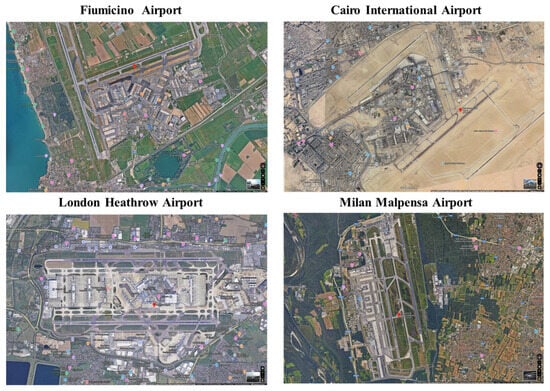

In particular, the method is tested by evaluating the electrical energy production in which four major airports in North Africa and South, Central, and North Europe are equipped with solar facilities specifically designed to recharge aircraft batteries. The chosen airports are Milan Malpensa (MXP) in Central Europe, Rome Fiumicino (FCO) in Southern Europe, London Heathrow (LHR) in Northern Europe, and Cairo International Airport (CAI) in North Africa, exemplifying diverse geographical and climatic conditions, facilitating a thorough evaluation of solar energy potential across different regions.

The purpose of this paper is to investigate the practical possibility of recharging a battery system designed for two types of aircraft with different flight ranges and passenger capacities and related levels of energy demand, i.e., the Airbus A320 [23] and the Pipistrel Alpha Electro [24]. The Airbus A320 was selected for this study because it is widely used in commercial flying, it is considered an example of a log-range, high-passenger-capacity and high-energy-demand flight, and it has a battery capacity of 28 MWh [23]. Moreover, a small-range, all-electric aircraft, such as the Pipistrel Alpha Electro equipped with a 0.021 MWh battery, is considered an opposite example with a short range, few passengers, and a low energy demand. The daily recharging frequency of battery systems is a critical metric that is assessed based on the specific time period (month) of the year.

2. Methods and Techniques

A hypothetical installation of photovoltaic systems has been considered at the four airports previously indicated, each situated at distinct latitudes, longitudes, solar radiation levels, and meteorological circumstances across three different continents. Figure 1 summarizes the software tools used to design PV installations. Google Maps [25] was used to pinpoint exact locations for the installation of photovoltaic systems and determine the size of buildings in the region of interest using the scale bar in the image. PVGIS 5.3 software [26] (developed by the European Commission, Joint Research Centre, Energy Efficiency and Renewables Unit, Ispra (VA), Italy) was used to determine the slope for panel installation and power outcomes. ImageJ software 1.52a (developed by the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) was utilized to calculate the total area for the installation of PV systems [27].

Figure 1.

Software tools used in the proposed PV installation design.

2.1. Data Collection and Analysis Using PVGIS

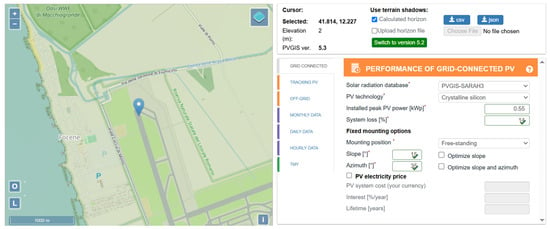

The PVGIS release 5.3 European Union database software was used to evaluate the solar energy potential of airports. This software includes data of solar radiation from satellite data. In the data, average clouds are considered. For instance, Sarah’s database picks up data from EUMETSAT (Climate Monitoring Satellite Application Facility) [28,29]. In particular, the database of solar radiation PVGIS-SARAH3 was used in this study. This dataset is incorporated in PVGIS release 5.3 and considers solar radiation from 2005 to 2023. Data are given as averaged quantities without uncertainty information [30]. To estimate the energy produced by each module in a given installation site, the key parameters were introduced into PVGIS, including an azimuth depending on the considered building orientation, a slope of 15°, and an installed peak photovoltaic output of 0.55 kWp (Figure 2). The slope was determined as the trade-off between the installed power and produced energy, considering a maximization of the installed power that can be achieved by fixing the slope to 0°. Such a condition is clearly not acceptable, and a slope larger than 0° has to be maintained to allow for natural rain cleaning of the PV panels. Then, these figures were selected to achieve maximum installed power while taking shadow behaviors into account.

Figure 2.

PVGIS image showing selected parameters for Rome Fiumicino Airport.

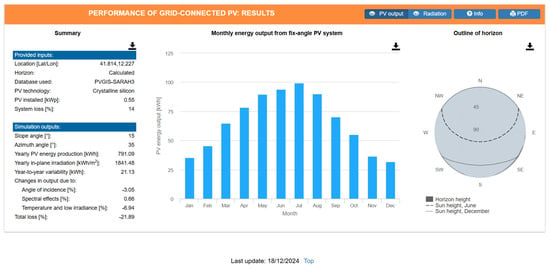

The year’s production for each airport was evaluated using the “Grid Connected” module in PVGIS, with the free-standing option. It is supposed that PV modules are mounted on plane roofs (as usually happens in modern airports) to allow for the considered 15° slope. The database used for sun irradiation is PVGIS-SARAH3, which assumes a crystalline silicium panel. The year’s production was evaluated per panel by considering, as previously mentioned, installed peak power of 0.55 kWp; system losses were supposed to equal 14%. The azimuth was evaluated according to the building orientation with respect to the south. The latitude was set to the same as that of the considered airports. The generated hourly profiles of temperature, electrical production, and irradiance obtained by the “Grid Connected” module in PVGIS for the selected site (Fiumicino Airport) are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

PVGIS image showing energy produced per installed panel in [kWh] per month for the site Rome Fiumicino Airport.

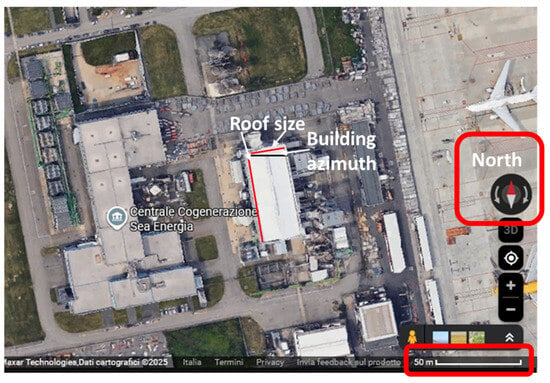

2.2. Site Assessment Using Google Maps

Suitable roof areas for solar panel installation were identified via Google Maps’ satellite imagery, considering the airport’s structures in February 2025. Screenshots of the airport roofs were obtained at a consistent north direction and zoom level. Each image (e.g., Figure 4) has its scale bar and north orientation. This information allows us to evaluate roof areas and building azimuth with respect to the south direction. Certain buildings were identified as potential candidates to install PV modules on their roof surfaces, while those with an insufficient roof area (typically allowing for less than 10 panels) were dismissed. Figure 5 shows the images of all airports with a north direction.

Figure 4.

Google Maps image at 50 m scale bar.

Figure 5.

Google Maps images (200 m north) of the 4 considered airports.

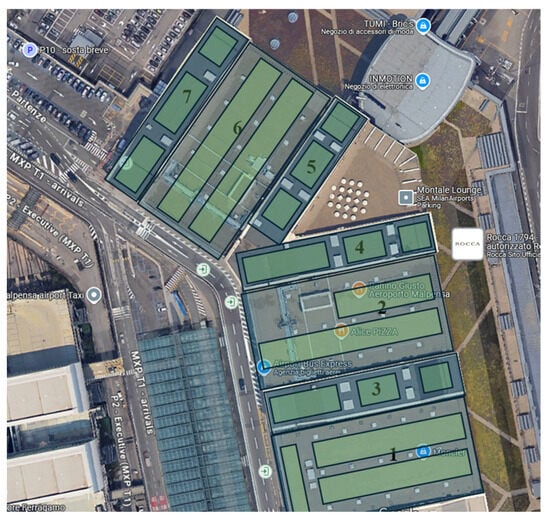

2.3. Detailed Measurements Using ImageJ

The screenshots obtained from Google Maps were loaded into ImageJ for precise dimension measurements. A calibrated scale was used to ensure accuracy. The size of the building was determined using the image scale bar. In practice, using ImageJ, a line can be superposed to the image scale bar for which a distance is defined in terms of pixel per meter with an uncertainty of 0.5 pixels, with a scale, e.g., of 5 pixel/m, u(Li) = 0.1/√3 = 0.06 m, considering a uniform distribution, u(Li). Using the ImageJ scale tool, the length defined by the scale bar image can be assigned to the drawn line. In this way, any other line drawn on the image is sized as a scale bar. The buildings are sized by superposing lines to their profile, and each line is measured according to the image scale bar. Moreover, using ImageJ also, the building azimuth with respect to the south direction can be evaluated since ImageJ gives the angle of any line drawn on the image with respect to the horizontal edge of the image frame. The total area available for solar panel installation was calculated by measuring the dimensions of the building’s sides and their azimuth with respect to the south direction. Figure 6 shows how the areas of the building’s roof are measured for the installation of solar panels using the methodology illustrated in Figure 4. In practice, the green rectangles are the building, and the ones with the same size/orientation are identified by a number. Each building profile is measured using a scaled line, and the azimuth with respect to the south was calculated. Considering an area L1 × L2, e.g., 15 ± 0.06 × 10 ± 0.06 m2, the uncertainty is ; if , then , and if 5 pixels are 1 m, then m2. For each building, the usable area is determined considering a 1 m band from the building edge where any panel can be installed. Then, a 1 m buffer zone was maintained around the roof edges to facilitate maintenance access and adhere to fire safety regulations.

Figure 6.

Calculation of building’s area in relation to installing solar panels: green areas are the considered buildings identified by a number (same-size/same-azimuth buildings are identified with the same number).

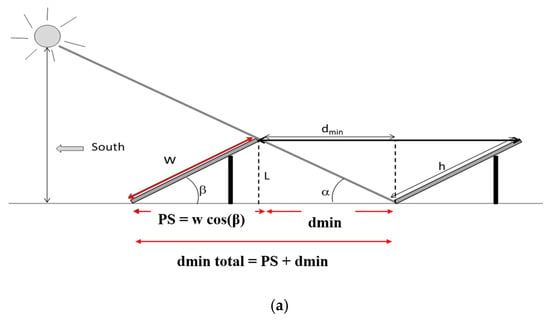

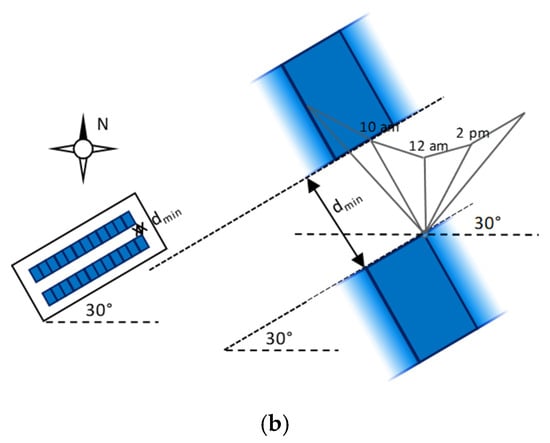

2.4. Panel Configuration and Installment

For all airports, the minimal distance, dmin = L cota, where L is the panel height and a is the sun high angle required between the panel’s rows to avert shadowing effects, was determined using a shadow study (Figure 7a,b) conducted between 11:00 a.m. and 2:00 p.m., taking into account the building azimuth with respect to the south and the sun high on 21 December. The panels were oriented with the short side parallel to the side closer to the south orientation. The object’s total height was 0.59 m with a 15° inclination. Two panel configurations were examined: horizontal (aligned with the length) and vertical installation (aligned with the width). The research indicates that horizontal installation of solar panels generated much more energy than vertical installation. In particular, buildings with a capacity for less than 10 panels to enhance installation viability were excluded.

Figure 7.

Blue shadow is the concept and calculation of dmin (a) for a south-oriented panel at noon and (b) with a different azimuth with respect to the south direction. The blue area identified a particular panel in a row represented by the white band.

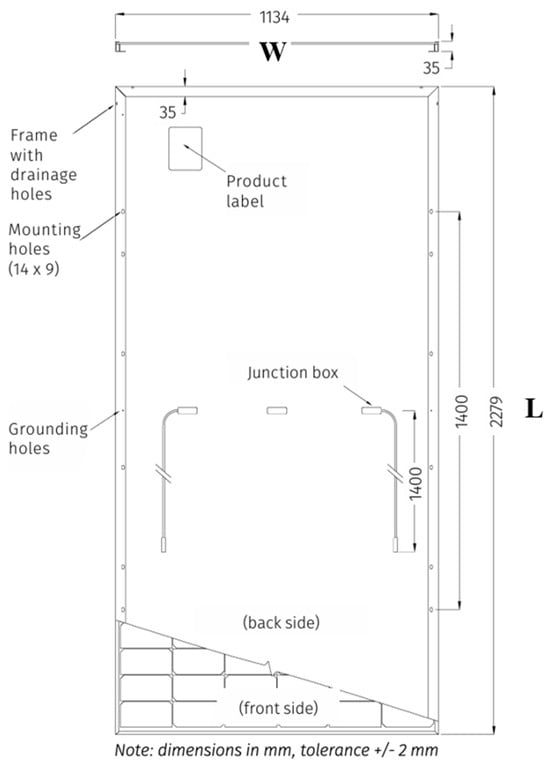

Figure 8 shows the technical drawing of the solar panels (FuturaSun Silk Plus), chosen because they are suitable for use in commercial and industrial locations. They measure 2279 × 1134 × 35 mm3 and have a 540–550 W power output.

The module distance, dmin total, was determined considering 21 December at noon, the longest shadow day in the Northern Hemisphere. Considering a south orientation of the panel surface, dmin total is obtained using the following equation:

where β is the module slope on Figure 7a, fixed to 15° as found in the optimization process, w is the panel length (w = 2.279 m), δ is the sun declination equal to −23.45° on 21 December in the Northern Hemisphere, φ is the latitude of the installation site, and PS is the length of the module projection on the x axis, as in Figure 7a.

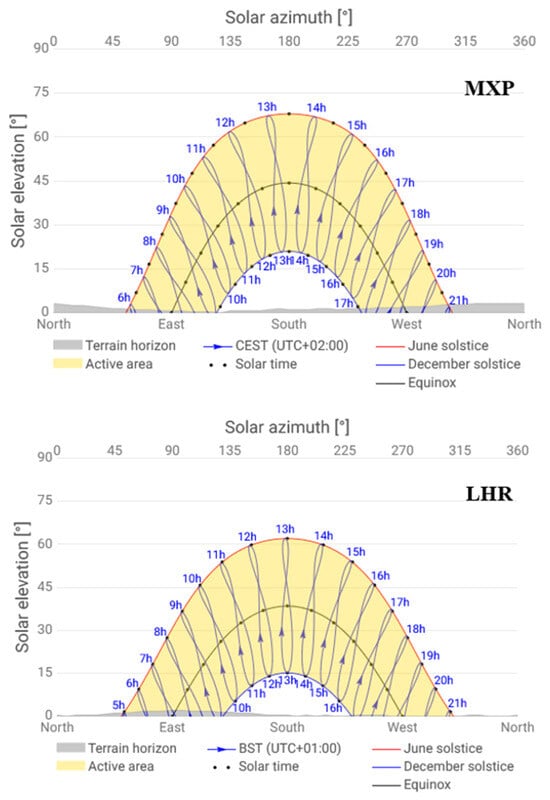

Assuming the azimuth of the building with respect to the south direction and considering an installation according to the roof orientation and sun height in the installation site, the is evaluated. As shown in Figure 7b, starting from the sun coordinate at a given azimuth, the shadow length on 21 December at 10:00 a.m. can be determined. This way, the considered shadow is longer with respect to that at noon, and consequently, this design allows for energy production also in the winter season. A time window exists when energy production is high enough to turn on the inverter from its sleeping-mode state, which happens from sunrise until solar radiation provides insufficient energy to balance the plant’s self-consumption. The sun coordinates on 21 December are obtained using Solargis software (developed by Solargis s.r.o., Bratislava, Slovakia) [31], available online. Using Solargis, solar maps were created for each airport to determine the solar installation design, as shown in Figure 9. Such a figure depicts the sun’s azimuth and elevation throughout the course of the year for each site. Solar coordinates were used for the shadow length analysis to determine the panel row distance, avoiding partial shadowing in the winter season.

Figure 8.

Structure and size of the considered PV panel (adapted from [32]).

Figure 9.

Solar coordinates of all 4 airport sites (SOLARGIS) [31].

3. Results and Discussion

The solar maps (Figure 9) show important details like the summer and winter solstices, equinoxes, and land slopes, providing essential information on the best direction and angle for solar panels to collect the maximal energy at each location. The following subsections delineate the solar energy potential at each airport, evaluating their capability to fulfill the energy requirements of electric aircraft charging infrastructure. By using scaled PVGIS data, Table 1 displays the energy production per panel per year in kWh for each airport at different azimuth angles and the total annual energy production per plant.

Table 1.

Total annual energy at specific azimuths.

For the sake of completeness of the study, a sensitivity analysis with respect to the panels’ slopes and associated spacings is carried out. Table 2 reports the energy produced considering a rectangular area with a Y direction 15 m long and an X direction 10 m long. The X direction is oriented towards the south. In this area, the energy generated by panels is evaluated considering different panel slopes between 10° and 40° and airport latitude (reported in Table 2). Panels in this analysis were oriented with their short edge aligned along the south direction.

Table 2.

Yearly PV output (kWh) from a 150 m2 airport area at MXP, FCO, and LHR for 10–40° tilts (bold = best south-facing; real terminal orientations favor the lowest tilt).

The yearly energy produced by one panel at optimal slope is also evaluated (expressed in bold letters and numbers in Table 2). Considering the panel size in Figure 7 along the X direction, there are eight panels. The number of panels along the Y direction is determined considering the shadow length at 12 p.m. on 21 December (the bad case g). The total number of panels in the considered area is the product of the ones along X by the ones along Y. This investigation shows that for MXP airport, the best energy production is obtained considering slopes of 20° and 15°, for which there is a yearly production of 22 MWh in the considered area. Considering building azimuth at 15°, the production will be lower with respect to the south, and the best option is positioning panels at minimum slope. The same considerations can be made for FCO airport, for which a south orientation has an optimal slope between 15° and 25°, but the building azimuth is 36°. Therefore, the minimum slope is the best solution. This is also the case for LHR, for which buildings are east–west-oriented (azimuth at 90°). Hence, the best solution is minimizing slope.

Table 3 reports the energy produced considering the same area to be filled by panels but considering the building azimuth indicated in Table 2. The annual energy produced by one panel is lower with respect to the values reported in Table 2. In this case, the number of panels along the Y direction is determined considering the shadow length at 10:00 a.m. on 21 December (the worst case). The total number of panels in the area considered is evaluated in these realistic conditions. This investigation indicates that the slope that maximizes the generated power could be different with respect to the previous case. For instance, for LHR airport, the best condition in this second case is for a slope between 10° and 15°, while before it was for a slope between 20° and 25°.

Table 3.

Annual PV production (kWh) in the 150 m2 area using actual terminal azimuths and 10:00 a.m. winter shadow spacing.

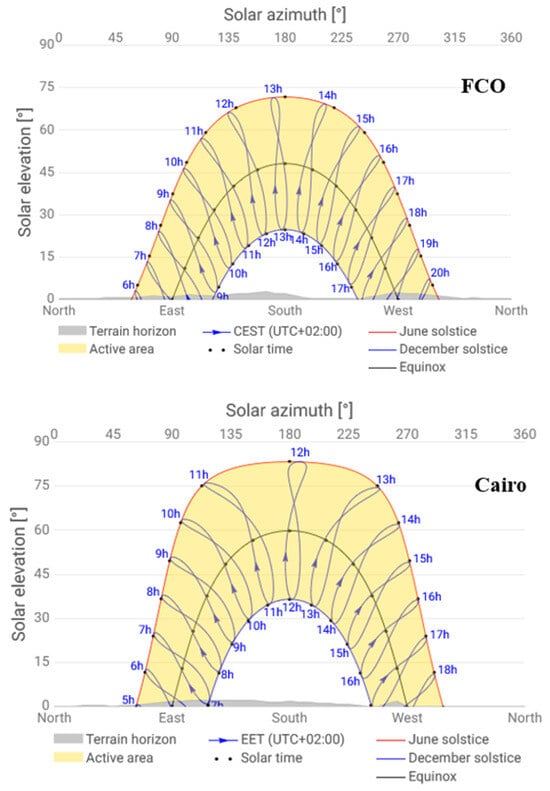

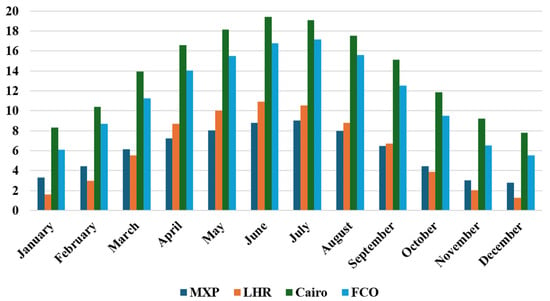

The bar graph in Figure 10 displays the total amount of electricity generated during each month (in GWh) at the four locations, namely MXP, LHR, Cairo, and FCO, which have azimuth angles of 15, 90, 105, and 36 degrees, respectively. The best performances are achieved at a slope of 15°, with each panel having a maximum power of 0.55 kWp. CAI and FCO typically generate far more energy than MXP and LHR, with peak production often surpassing 13 million kWh per month. Seasonal fluctuations are evident, with energy output typically rising during the summer months (June–August) at all locations. CAI and FCO have consistently high production throughout the year. MXP and LHR show more significant swings, particularly reduced output during cold months such as January and December.

Figure 10.

Total power generated (GWh/month) of all airports.

3.1. Milan Malpensa Airport (MXP), Central Europe

MXP can fit up to 87.53 × 103 PV panels on certain building roofs. PVGIS simulations calculated an annual energy production of 697 kWh per panel, optimum at a slope of 15 degrees and an azimuth of 15 degrees, with a peak PV power of 0.55 kWp per panel. The calculated system’s overall yearly power production is 61.01 × 106 kWh/year. Even though MXP produces less energy than the other airports because it has fewer buildings, it can still be important for Central Europe’s system of recharging electric and hybrid aircraft batteries if other airport-available areas for the installation of panels can be used.

3.2. Rome Fiumicino Airport (FCO), Central/Southern Europe

For FCO, a maximum capacity of 15 × 104 photovoltaic panels over designated roofs was evaluated. The yearly energy output, estimated by PVGIS, is 790, 802, 751, and 700 kWh for single panels positioned at different angles (azimuth) of 36, 20, 66, and 95, set at a 15-degree tilt, with each panel having a maximum power of 0.55 kWp. The system’s total yearly power generation is estimated to be 11.53 × 107 kWh/year, based on various panels positioned at distinct azimuths in relation to the building’s orientations. Leveraging Southern Europe’s advantageous solar conditions, FCO has considerable potential to fulfill the energy demands for recharging electric aircraft batteries, thereby furthering the region’s initiatives to decarbonize the aviation sector.

3.3. London Heathrow Airport (LHR), Northern Europe

For LHR, the solar installation potential is equal to 13.36 × 104 photovoltaic panels for deployment on designated building roofs. PVGIS simulations showed that a single panel could produce 465,523,493 kWh of energy each year at angles of 90, 30, and 65 degrees, with a slope of 15 degrees and a maximum power output of 0.55 kWp per panel. Subsequently, as per the building’s different directions, the total panel production on the basis of different panels at different azimuths was calculated. This setup yielded an annual power production of 62.52 × 106 kWh/year for the system. Even though this production is impressive, LHR’s location in Northern Europe creates problems because there is less sunlight, especially in winter, which means that we need extra energy methods to ensure that hybrid and electric aircraft batteries can be reliably recharged in this region.

3.4. Cairo International Airport (CAI), North Africa

For Cairo International Airport, a maximum of 16.20 × 104 photovoltaic panels for installation on designated roofs was estimated. The PVGIS study revealed an annual energy production of 838 kWh per panel, optimal at a slope of 15 degrees and an azimuth of 105 degrees, with a peak photovoltaic power of 0.55 kWh per panel. The system’s total yearly power production was determined to be 14.26 × 107 kWh/year. Cairo Airport capitalizes on North Africa’s ample solar irradiance, demonstrating significant potential for recharging electric aircraft batteries, facilitating multiple daily charging cycles, and substantially aiding the aviation industry’s transition to renewable energy in the region.

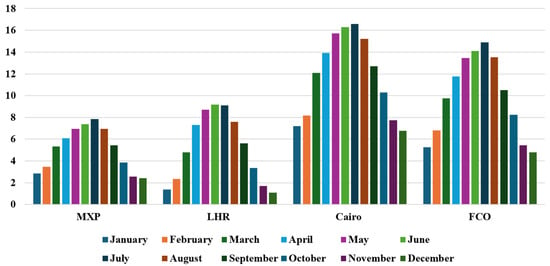

3.5. Battery Charging Capacity

The solar energy produced at the four airports, assessed by PVGIS for the planned rooftop installations, enables the recharge of battery systems for the Airbus A320, each possessing a capacity of 28 MWh, promoting the integration of electric and hybrid aircraft. The PVGIS figures, as already evidenced, include a 14% energy loss attributable to variables like inverter inefficiencies and transmission losses, indicating the effective energy available for charging. This analysis measures how much energy can be used to charge batteries each day, month, and year at each airport, based on the solar energy produced by the largest possible panel setups (buildings with fewer than 10 panels are neglected), and it assumes that energy is evenly spread out over the year to create a standard for charging potential.

The solar panels at four major airports allow for the recharge of Airbus A320 batteries (28 MWh apiece), thereby facilitating electric or hybrid electric aircraft operations in various locations. Milan Malpensa Airport (MXP) in Central Europe has the capacity to recharge roughly 2181 batteries yearly, averaging around 6 batteries daily and 181 batteries monthly (based on a 30-day period). Rome Fiumicino Airport (FCO) in Southern Europe processes 4236 batteries annually, averaging 11 per day and 343 per month. With an average of 6 batteries per day and 186 per month, London Heathrow Airport (LHR) in Northern Europe handles 2220 batteries a year. Cairo International Airport in North Africa processes 5094 batteries yearly, averaging 14 per day and 424 per month, underscoring their capacity to enhance sustainable aviation infrastructure.

Figure 11 shows how much battery recharging capacity solar systems have each month at Milan Malpensa (MXP), Rome Fiumicino (FCO), London Heathrow (LHR), and Cairo International Airports. The graph shows the daily average of Airbus A320 batteries (28 MWh apiece) that may be charged, emphasizing notable seasonal variations across the airports. MXP’s capacity varies from 2 to 8 batteries daily, reaching its zenith in July owing to increased solar production. FCO has the greatest variety, ranging from 5 to 16 batteries per day, with a peak in July. LHR’s capacity varies from 1 to 10 batteries, peaking in June, indicative of seasonal solar trends. Cairo maintains consistent solar power production, recharging 7 to 19 batteries daily, with June as the peak month, underscoring its reliable solar potential throughout the year. These variations in Table 4 highlights the influence of sun availability and regional disparities on daily recharging capacity. Nevertheless, when managing electric aircraft using only green energy, only a small percentage of the total number of daily flights can be recharged. For instance, FCO airport manages more than 10 flight departures per hour, so 5–16 charged batteries per day with an additional 88.4 MW of photovoltaic power installed (22 MW is the current installed power) is just a small part of all the required energy to manage electrical aircraft supply with green energy, considering that in FCO, a 22 MW PV plant has been in operation since 2024.

Figure 11.

Different airports’ capacity to recharge batteries (28 MWh) per day.

Table 4.

Battery (28 MWh) charging capacity of all airports.

The adopted approach could also be used for evaluating the charging of smaller all-electric aircraft, such as the Pipistrel Alpha Electro (equipped with a 0.021 MWh battery), with the same infrastructure [24].

At MXP, roughly 29.07 × 105 Pipistrel Alpha Electro batteries (21 kWh each) may be recharged annually, i.e., between 11.50 × 104 and 35.08 × 104 batteries monthly and between 3710 and 12,047 daily, peaking in July. FCO could recharge yearly around 56.46 × 105 batteries, with monthly figures ranging from 22.84 × 104 to 70.87 × 104 and daily counts between 7368 and 22,864, peaking in July. During its peak in June, LHR is capable of processing between 1663 and 14,572 batteries daily, 51.54 × 103 to 43.71 × 104 batteries monthly, and around 29.60 × 105 batteries annually. CAI has the capability to recharge around 67.93 × 105 batteries annually, 32.23 × 104 to 77.58 × 104 monthly, and 10,400 to 25,863 daily, with June being the peak month (Table 5).

Table 5.

Battery (0.021 MWh) charging capacity of all airports.

These numbers illustrate the potential for each site to facilitate large-scale electric aircraft operations, with seasonal peaks denoting favorable times for optimizing the use of battery recharging infrastructure. Future research may investigate uses of power supply for ground services.

The estimated energy production by PV plants can be considered a small percentage of the total energy required for airports and related service functioning. In this context, energy storage using batteries was not considered because it increases the cost of the plant without providing significant benefits. In fact, the produced energy can supplement the energy provided to airport services and reduce the energy produced by traditional fossil fuel plants. For instance, MPX airport has an electrical generation unit that supports airport supply based on two natural gas cogeneration units sized at 31.25 MW and 30 MW [33]. Then, photovoltaic energy could be a support of energy produced daily by means of other fuels during sunny hours. SEA, the society that manages both MPX and Linate airports, reported an energy consumption of around 388 GJ with 17% of green energy support for both airports in 2024 [34]. Then, photovoltaic energy is only a small percentage of the required energy. In 2025, Fiumicino Airport installed a 22 MW photovoltaic land plant for a production of 30 GWh/y that integrates the cogeneration plant production in order to reduce the power network absorption [13,35]. FCO consumes more than 9 GWh per year, i.e., more than 32,400 GJ, whereas the energy consumption in London Heathrow Airport is around 271 GWh/y [36]. One hypothesis in this case is to provide a 150 MW PV plant with a year’s production of 135 GWh.

Other aspects associated with energy production based solely on green sources, such as that deriving from PV plants, instead of a mix of green and traditional energy, must be well considered. Green energy production could be unstable, and if there is a rapid change in weather, it could not adequately face the risks of blackout and service interruption due to a request larger than the actual production. To avoid this drawback, the best approach is balancing green and traditional energy supply. Short interruption of the battery charging for service vehicles or aircraft could be acceptable, whereas stopping operativity of the airport must be avoided.

Finally, as it concerns the glare problem, it can be considered to have a limited impact, since photovoltaic modules are designed to avoid glare and improve light absorption. In particular, less than 5% of reflection is estimated. Nevertheless, during sunrise and sunset, when the incidence angle is larger than, e.g., 60°, the reflection can increase [37]. This problem was also analyzed by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Golden, CO, USA [38], and some countries issued regulations to reduce the problem. In general, smaller slopes have to be avoided [37]. Nevertheless, some airport plants were already realized. For instance, the last was recently realized at FCO airport. This plan is integrated along with the takeoff and landing area and is actually considered the biggest in the airport area with its 22 MW installed. Nevertheless, in the past, some airports were realized, as at Delhi Airport there is a 7.84 MW plant on the airside and a 5.3 MW rooftop solar plant [14]. The first 2.4 MWp plant was installed at Fresno Yosemite International Airport (FAT) in the USA, and it has been in operation since 2008 [16]. Additionally, Bologna Airport, BLQ, is foreseeing a 4.4 MW plant in the baggage handling area [15]. Then, airport plants aim to increase the energy available to recharge electrical aircraft that require more electrical energy to be available.

Considering that few airports are already provided by PV plants, this paper proposes a methodological approach to study the feasibility at different latitudes and then different climate characteristics in terms of sun irradiation for the installation of green energy sources from the perspective of the introduction of electrical aircraft. In fact, the future spreading of electrical aircraft will increase the demand for electrical energy. This way, to preserve the green trend of future aviation, it is mandatory for future airports to introduce green energy sources in order to increase energy production inside the site. The best would be to introduce green energy sources that are able to supply the energy required to recharge green electrical aircraft.

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

This study has proposed a method for assessing the feasibility of placing solar panels on airport roofs. The method that integrates data from available software packages (PVGIS, Google Maps, and ImageJ) has been applied to evaluate the potential energy production and optimal photovoltaic plant arrangement in four airports with different solar energy availabilities in North Africa and North, Central, and South Europe. A horizontal installation configuration of the PV modules with minimum tilt to allow for rain cleaning is found to be the optimal option for maximizing renewable energy production, since it yields the maximum energy output.

Under the considered hypothesis, all the analyzed airports (Cairo International, London Heathrow, Milan Malpensa, and Rome Fiumicino) cannot produce energy recharge for more than 20 Airbus 320 aircrafts with 28 MWh battery packs per day. However, these photovoltaic plants can provide sufficient energy to recharge a Pipistrel Alpha Electro equipped with a 0.021 MWh battery. Considering the 28 MWh battery in the North Europe airport, in London, the photovoltaic energy could recharge from 1 in winter up to 10 batteries during summer. The figures are more favorable for Cairo installations, where the produced energy allows from 7 to 19 recharges per day from winter to summer.

Future studies will look into the impact of adding solar panels to airport parking lots and fields to see if this can create a system where aircraft batteries can be fully recharged, making it easier and more sustainable to use renewable energy in aviation.

In addition, future research will also examine other factors such as integration with existing infrastructure, economic feasibility, and the impact of seasonal variations on energy production.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H.K., P.L. and E.S.; methodology, M.H.K., P.L. and E.S.; investigation, M.H.K. and E.S.; resources, P.L. and V.T.; data curation, M.H.K. and E.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.H.K.; writing—review and editing, M.H.K., P.L., E.S. and V.T.; supervision, V.T.; funding acquisition, P.L. and V.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the European Union Horizon Europe research and innovation program (HORIZON-CL5-2021-D5-01-05) under grant agreement no. 101056866 (EFACA project) and by FARB funding of the University of Salerno.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

M.H.K. acknowledges the support received from the Dottorato di Ricerca Nazionale (National PhD) in Photovoltaics funded by the Italian Ministry for University and Research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability; Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg2/ (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- United Nations. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1992; Available online: http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/conveng.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Hermawan, K. Design Analysis of Photovoltaic Systems as Renewable Energy Resource in Airport. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Information Technology, Computer, and Electrical Engineering (ICITACEE), Semarang, Indonesia, 18–19 October 2017; pp. 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayigh, A. Renewable Energy: A Status Quo; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: https://books.google.se/books?id=HKijDAAAQBAJ (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Johannsen, R.M.; Mathiesen, B.V.; Kermeli, K.; Crijns-Graus, W.; Østergaard, P.A. Exploring Pathways to 100% Renewable Energy in European Industry. Energy 2023, 268, 126687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.F.; Abdel Aleem, S.H.E.; Zobaa, A.F. Risk Assessment and Possible Mitigation Solutions for Using Solar Photovoltaic at Airports. In Proceedings of the 2016 Eighteenth International Middle East Power Systems Conference (MEPCON), Cairo, Egypt, 27–29 December 2016; pp. 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In Renewable Energy Sources and Climate Change Mitigation; Edenhofer, O., Pichs Madruga, R., Sokona, Y., Seyboth, K., Matschoss, P., Kadner, S., Zwickel, T., Eickemeier, P., Hansen, G., Schlömer, S., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rüther, R.; Braun, P. Energetic contribution potential of building-integrated photovoltaics on airports in warm climates. Solar Energy 2009, 83, 1923–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, I.; Tatsunokuchi, M.; Nakahara, H.; Tomita, T. Bifacial PV system in Aichi Airport-site demonstrative research plant for new energy power generation. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2009, 93, 911–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpholo, M.; Nchaba, T.; Monese, M. Yield and performance analysis of the first grid-connected solar farm at Moshoeshoe I International Airport, Lesotho. Renew. Energy 2015, 81, 845–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramashivaiah, P.; Chakraborthy, S.; Shashidhar, R. Illuminating an airport with sustainable energy: Case of Cochin International Airport. OIDA Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 11, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Galapagos Ecological Airport: The World’s First Ecological Airport. Corporación América Airports. 2025. Available online: https://caap.aero/n.php?id=41 (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Aeroporti di Roma (ADR). ADR: Rome Fiumicino Airport’s New Solar Farm Unveiled. Aeroporti di Roma. 2025. Available online: https://www.adr.it/documents/10157/34057756/PR+Solar+Farm+%28ENG%29.pdf/6de18f05-b834-73d3-536c-3e1af0f7b00a?t=1737371568504 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Reccessary. Delhi Airport Becomes India’s First to Run Entirely on Hydro, Solar. Reccessary. 2024. Available online: https://www.reccessary.com/en/news/Delhi-Airport-becomes-Indias-first-to-run-entirely-on-hydro-solar (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Aeroporto Guglielmo Marconi di Bologna S.p.A. Projects Involving Photovoltaic Systems. Bologna Airport Official Website. 2025. Available online: https://www.bologna-airport.it/en/innovability/sustainability/sustainability-plan/photovoltaic/?idC=62809 (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Fresno Airport Dedicates Solar Installation. Renewable Energy World. 22 July 2008. Available online: https://www.renewableenergyworld.com/solar/fresno-airport-dedicates-solar-installation-53113/ (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Sreenath, S.; Sudhakar, K.; Yusop, A.F. Airport-based photovoltaic applications. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2020, 28, 833–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Qi, L.; Yu, Z.; Wu, D.; Si, P.; Li, P.; Yan, J. National level assessment of using existing airport infrastructures for photovoltaic deployment. Appl. Energy 2021, 298, 117195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarshenas, P. The transformation of the green sustainable airports construction industry through the innovative applications of green energies in comprehensive energy modality of Venus: A study on the supply & development of renewable energy in airports of country with dry climate by means of wind & solar energy. Geek Chron. 2024, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Pipistrel Aircraft d.o.o. Velis Electro. Pipistrel Aircraft. 2025. Available online: https://www.pipistrel-aircraft.com/products/velis-electro/ (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Ollas, P.; Sigarchian, S.G.; Alfredsson, H.; Leijon, J.; Döhler, J.S.; Aalhuizen, C.; Thiringer, T.; Thomas, K. Evaluating the role of solar photovoltaic and battery storage in supporting electric aviation and vehicle infrastructure at Visby Airport. Appl. Energy 2023, 352, 121946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, M.; Leijon, J. Electrifying aviation: Innovations and challenges in airport electrification for sustainable flight. Adv. Appl. Energy 2025, 17, 100222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, X. Aviation-to-Grid Flexibility Through Electric Aircraft Charging. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 8149–8159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipistrel. Alpha Electro. Available online: https://pipistrelaircraft.eu/alpha-electro/ (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Google Maps. Satellite Imagery and Mapping Data for (Region of Interest). Available online: https://www.google.com/maps (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Huld, T.; Pinedo Pascua, I.; Gracia Amillo, A. PVGIS 5: Internet Tools for the Assessment of Solar Resource and Photovoltaic Solar Systems; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2017; JRC107813. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC107813 (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- National Institutes of Health (NIH). ImageJ Software. Available online: https://imagej.net/ij/ (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Urraca, R.; Gracia-Amillo, A.M.; Koubli, E.; Huld, T.; Trentmann, J.; Riihelä, A.; Lindfors, A.V.; Palmer, D.; Gottschalg, R.; Antonanzas-Torres, F. Extensive validation of CM SAF surface radiation products over Europe. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 199, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EUMETSAT. CM SAF—Satellite Application Facility on Climate Monitoring; EUMETSAT: Darmstadt, Germany, 2025; Available online: https://www.cmsaf.eu/EN/Home/home_node.html (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Taylor, N.; Martinez, A.; Alexandris, N.; Gounari, O.; Szabo, S.; Chatzipanagi, A.; Mercado, L.; Falangas, A. Photovoltaics Geographical Information System: Status Report 2024; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Data, Software and Services for Solar Projects|Solargis. Available online: https://solargis.com/ (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- FuturaSun. SILK® Plus—Pannelli Monocristallini 108 Celle Black Frame. Available online: https://www.futurasun.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/FuturaSun_144_540-550W_Silk-Plus_IT.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- A2A Airport Energy S.r.l. Centrale di Malpensa. A2A Airport Energy S.r.l. 2025. Available online: https://www.a2aairportenergy.it/it/impianti/centrale-malpensa (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- SEA—Società Esercizi Aeroportuali S.p.A. SEA ESG Report 2024; SEA Milan Airports: Milan, Italy, 2025; Available online: https://milanairports.com/sites/default/files/SEA%20ESG%20Report%202024_DEF.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- European Commission. PIONEER: Decarbonising Airport Operations with Second-Life Car Batteries; European Climate, Infrastructure and Environment Executive Agency (CINEA): Brussels, Belgium, 2025; Available online: https://cinea.ec.europa.eu/featured-projects/pioneer-decarbonising-airport-operations-second-life-car-batteries_en (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Ventus Ltd. Heathrow Airport Energy Use and the Case for Onsite Generation; Ventus Ltd.: Singapore, 2024; Available online: https://www.ventusltd.com/post/heathrow-airport-energy-use-and-the-case-for-onsite-generation (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Sreenath, S.; Sudhakar, K.; Yusop, A.F. Solar PV in the airport environment: A review of glare assessment approaches & metrics. Sol. Energy 2021, 216, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). Analyzing Glare Potential of Solar Photovoltaic Arrays; NREL/FS-6A10-67250; U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy: Golden, CO, USA, 2016. Available online: https://docs.nrel.gov/docs/fy17osti/67250.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).