1. Introduction

Globally, with the continued expansion of renewable energy sources, which are also referred to as inverter-based resources (IBRs), some conventional power plants are being decommissioned or taken offline [

1]. The majority of decommissioned power plants are coal- and gas-fired power plants that employ synchronous generators (SynGen), which play a crucial role in the maintenance of the power system stability by providing reactive power compensation, inertia, and a short-circuit current [

2,

3,

4,

5].

IBRs that are connected to the grid via grid-following (GFL) voltage source converters, which are commonly used, can degrade the power system stability [

6,

7,

8]. These voltage source converters act as current sources, and they are synchronized with the grid’s frequency and voltage through phase-locked loop control. Consequently, GFL IBRs are dependent on the frequency and voltage of the grid, and therefore, they can operate reliably only when the grid is stable [

9,

10]. Unlike conventional SynGen, GFL IBRs do not provide physical rotational inertia energy to the grid. Hence, the stability of the power grid could be adversely affected when IBRs are connected to it, especially as the number of GFL IBRs increases [

11,

12].

To address these issues, non-transmission alternatives (NTA) are being studied, as they offer flexible, cost-effective, and rapidly deployable solutions; examples of NTAs are flexible AC transmission systems [

13,

14,

15,

16] and energy storage systems [

17,

18,

19]. One such NTA device is the synchronous condenser (SynCon), which is a synchronous machine without a prime mover. Its basic principle is similar to that of the SynGen, with the exception that it does not provide active power [

20]. In the SynCon, voltage is regulated through the control of reactive power by regulating the field current via an exciter. Notably, the SynCon provides rotational inertia (to the rotor) and short-circuit current, thereby enhancing the stability of the power system. In other words, the SynCon functions as an inertia resource as well as a reactive power compensation resource [

21,

22]. It can be used as an inertia resource to enhance the frequency stability of a power grid [

21]. Therefore, installation location of SynCon is closely related to active power, which is less location dependent owing to the low resistance of transmission lines. Consequently, when the SynCon is to be used as an inertia resource, the total amount of inertial energy injected into the grid is crucial, and the installation location of SynCon can be ignored [

22]. By contrast, when the SynCon is used as a reactive power compensation resource, it is highly location dependent owing to the high impedance of transmission lines. Therefore, the location and specifications of the SynCon can be determined by considering the effects of reactive power on voltage and transient stability enhancement.

There have been several studies on the optimal determination of the installation location and specifications of the SynCon for enhancing the stability of power systems [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. In [

23], the effect of the SynCon’s placement on electric power system networks was analyzed, with the focus being on identifying optimal locations to enhance voltage stability. With the primary objective of addressing challenges in regulating the voltage in medium-voltage networks, the study employed simulation-based approaches to determine an appropriate SynCon placement. In [

24], a SynCon placement methodology was proposed to enhance the system short-circuit ratio (SCR) in power systems with high renewable energy penetration. The study evaluated the effect of the SynCon’s placement on the SCR at various nodes in a network and provided an allocation strategy to strengthen weak nodes. In [

25], a genetic-algorithm-based optimal allocation method was proposed for the SynCon in wind-dominated power grids. This method helps to enhance the economic benefits of SynCon installation and to improve the SCR at critical grid locations. In [

26], a variety of optimization techniques were employed with the objective of optimizing the installation location and size of the SynCon. The optimization increased the SCR and reduced the investment, operation, and maintenance costs of the SynCon. In [

27], the reactive power limit of SynCon in HVDC transmission systems was optimized on the basis of the reactive power conversion factor. The optimization methodology enhanced the reactive power output of SynCon to improve the HVDC system performance, especially in terms of voltage stability. The reactive power output limit of the SynCon was optimized for enhancing the transmission capacity and voltage stability of HVDC systems. While previous studies have focused on optimizing the locations and ratings of SynCon for voltage stability or power system strength enhancement, existing studies only optimize voltage stability or system strength individually, without simultaneously considering transient stability or jointly optimizing voltage settings and installation locations.

This paper proposes a methodology for the optimization of the installation location and voltage setting of the SynCon for improving the voltage stability and transient stability of a power system. The remaining part of this paper is ordered as follows:

Section 2 presents the power system stability indices, and

Section 3 describes the proposed method, which is based on the power system stability indices.

Section 4 presents an overview of the power system considered in this study, in which SynGen were replaced with IBRs. In

Section 5, simulation results are presented and discussed. Finally,

Section 6 presents the conclusion.

3. Proposed Method

The optimization process was performed using the Differential Evolution (DE) algorithm, which is suitable for solving non-linear, constrained, and multi-objective problems [

31]. The DE algorithm is a simple population-based heuristic for solving non-linear and constrained optimization problems. It maintains a population of candidate solutions and iteratively updates them through three basic operations: mutation, crossover, and selection. At each generation, a mutant vector is generated by adding a scaled difference between two randomly selected individuals to a third base individual. A trial vector is then formed by recombining the mutant and the current target individual according to a given crossover rate. The trial vector is evaluated by the objective function, and it replaces the target individual if it provides a better objective value; otherwise, the original target is retained. This process is repeated until a stopping criterion, such as the maximum number of generations, is reached.

In this study, the DE algorithm is used to optimize the configuration of SynCon, including their installation locations and terminal voltage setpoints. Here, the voltage setpoint refers to the reference voltage of the automatic voltage regulator (AVR), whereas the actual terminal voltage and reactive power output are determined by the power-flow solution and the device’s reactive power capability under AVR control.

Each individual in the population encodes a candidate SynCon configuration as a vector of decision variables. For a given individual, steady-state power-flow and transient stability simulations are performed to evaluate the voltage stability index and transient stability margin, which are combined into a composite objective function. The DE operators (mutation, crossover, and selection) are then applied to iteratively improve the population and search for the SynCon configuration that minimizes the objective function while satisfying the operational constraints. In all case studies, the parameters of the DE algorithm are fixed as follows: the population size is set to 100, the maximum number of generations to 100, the mutation factor to 0.243, and the crossover probability to 0.651. These values were chosen based on preliminary tuning and further increases in population size or maximum number of generations did not lead to noticeable changes in the optimal solution.

3.1. Objective Function

To optimize the installation location and voltage settings of the SynCon to improve power system stability, we used power system stability indices in the objective function. Several objective functions were designed to address different aspects of system stability.

The objectives of Functions (1)–(3), shown as Equations (4)–(6), were to enhance the voltage stability, improve the transient stability, and simultaneously optimize both voltage stability and transient stability. The relative importance assigned to each stability aspect was influenced by the weights ω.

Objective Function 1 involved IVSIT, a voltage stability index, to assess the voltage stability of the entire power system. Following the installation of the SynCon, a power flow analysis was conducted to determine the IVSIi at each bus, and subsequently, all IVSIi values were summed to obtain IVSIT. The optimization process involved minimizing IVSIT to enhance voltage stability.

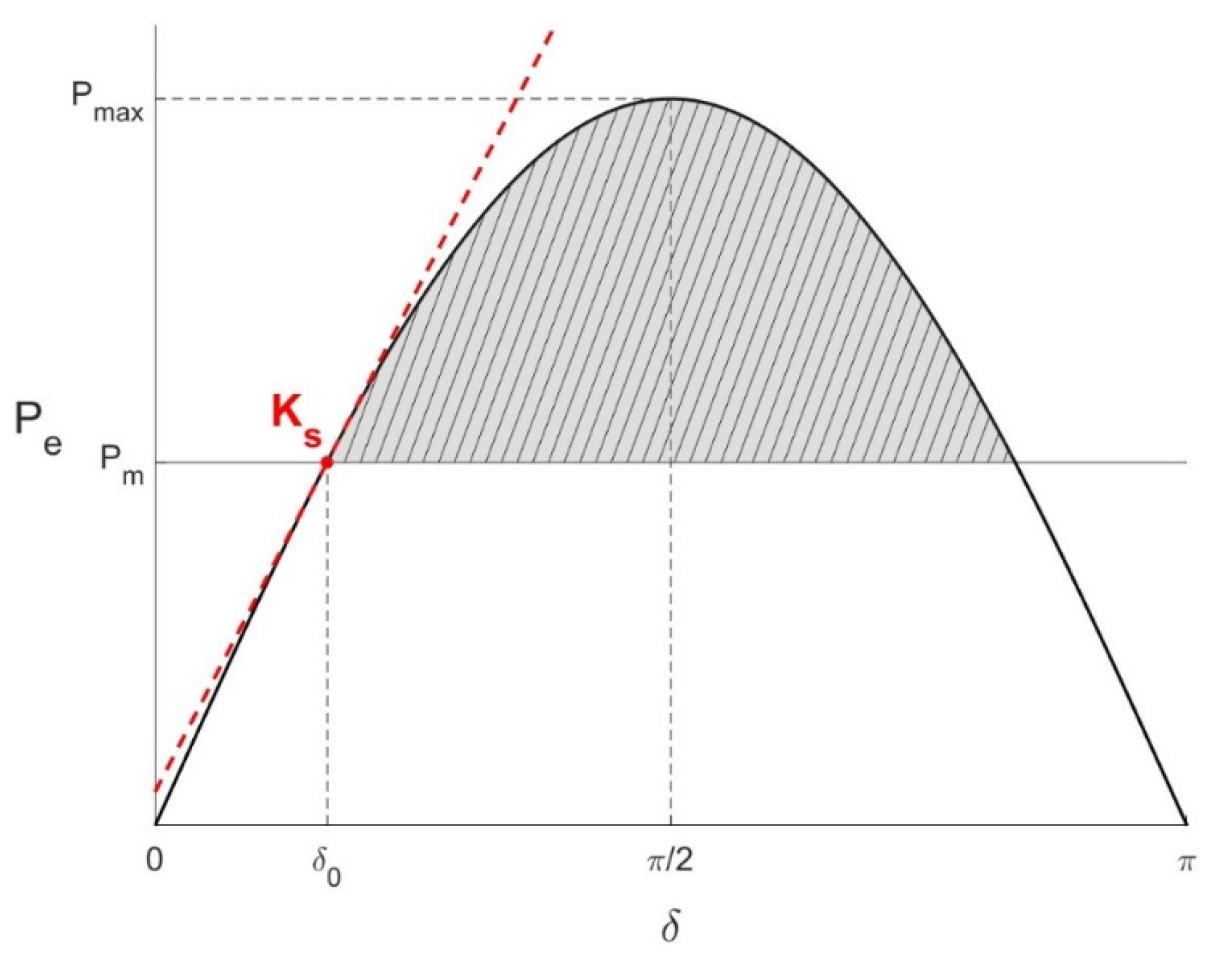

Objective Function 2 employed to assess the transient stability of the SynGen. The objective was to improve the transient stability of the SynGen exhibiting the lowest transient stability. In other words, the optimization process involved increasing of the SynGen with the lowest , hereafter denoted by , to enhance transient stability. To identify the SynGen with , we derived a single machine infinite bus (SMIB) model, and the power-angle curve was plotted for each of the SynGen to calculate their respective values.

Objective Function 3 was a comprehensive objective function, and it integrated objective Function 1 and objective Function 2 by combining their respective stability indices, namely IVSIT and , and employed weights. The objective was to simultaneously optimize both voltage stability and transient stability by minimizing IVSIT and maximizing . The minimization and maximization were intended to enhance the overall voltage stability and improve the transient stability of the SynGen with the lowest transient stability, respectively.

In the case of voltage stability, after installing SynCon, a power flow analysis is conducted to calculate IVSIi for each bus, and the sum of these values IVSIT is used. For transient stability, SMIB model is derived for the SynGen with , and the corresponding power-angle curve is plotted to calculate .

3.2. Constraints

A voltage tolerance of 5% is typically deemed acceptable for steady-state operation [

32]. Accordingly, the voltage of the SynCon was set to be in the range of 0.95 to 1.05 p.u. Furthermore, to compare power system stability characteristics for different SynCon installation locations, we prohibited the installation of multiple SynCon on a single bus. Additionally, the reactive power output of the SynCon was limited to ensure that it did not exceed the maximum capacity of SynCon. For all buses, the IVSI

i was maintained to be in the range of 0 to 1.

5. Case Study

In a case study, we analyzed the voltage and transient stability of the power system for the optimal location and voltage setting of the SynCon. The case studies were based on the objective functions presented in (4)–(6) and the scenarios presented in

Table 1.

5.1. Objective Function 1: Voltage Stability Improvement

Table 2 and

Table 3 present optimization results for enhancing the voltage stability under scenarios with different numbers and capacities of SynCon.

Table 2 presents the optimization results for voltage and transient stability indices under scenarios with varying numbers and capacities of SynCon. A decrease in IVSI

T reflects an improvement in overall voltage stability, while an increase in

indicates enhanced transient stability.

Table 3 summarizes the corresponding optimal installation locations and voltage settings of SynCon for each scenario.

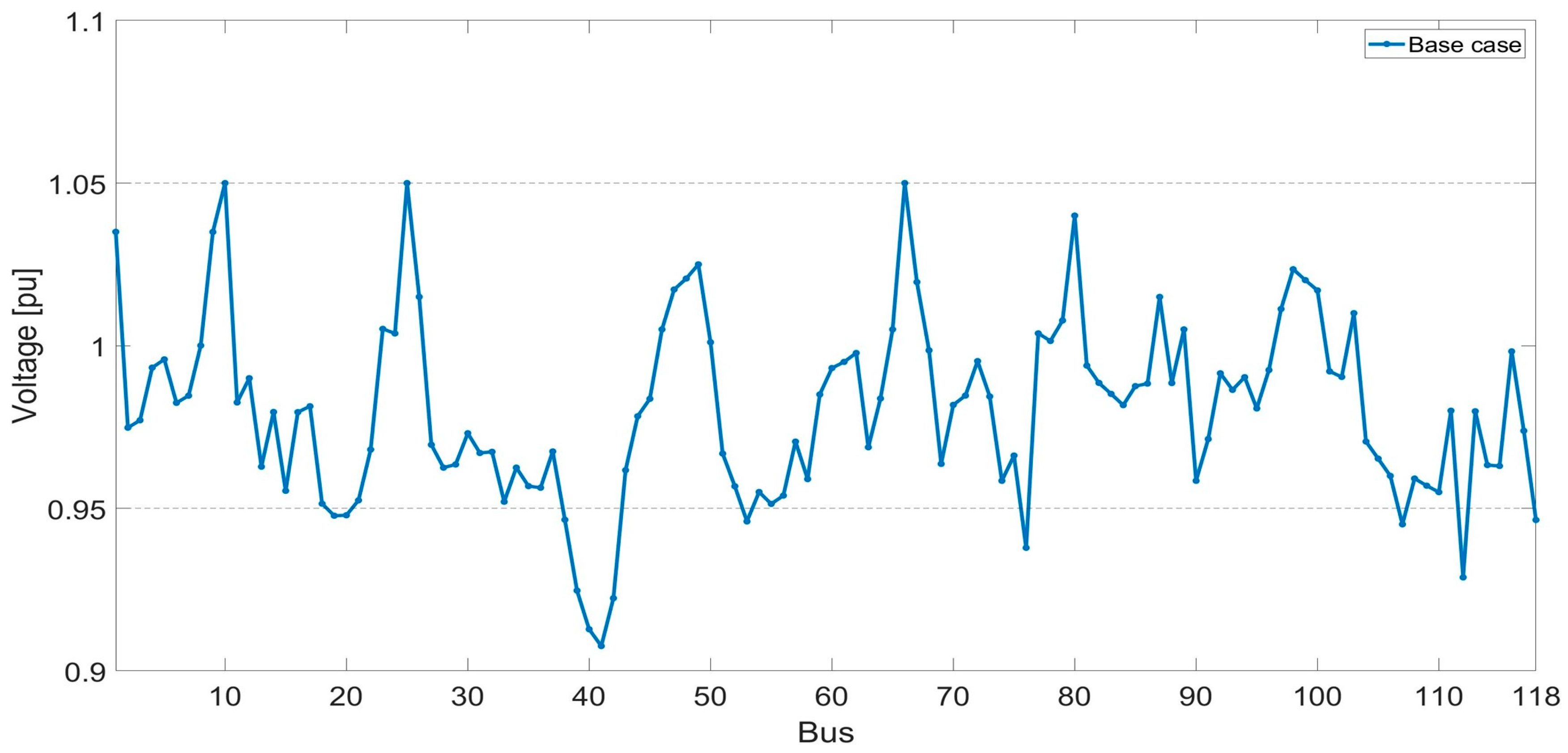

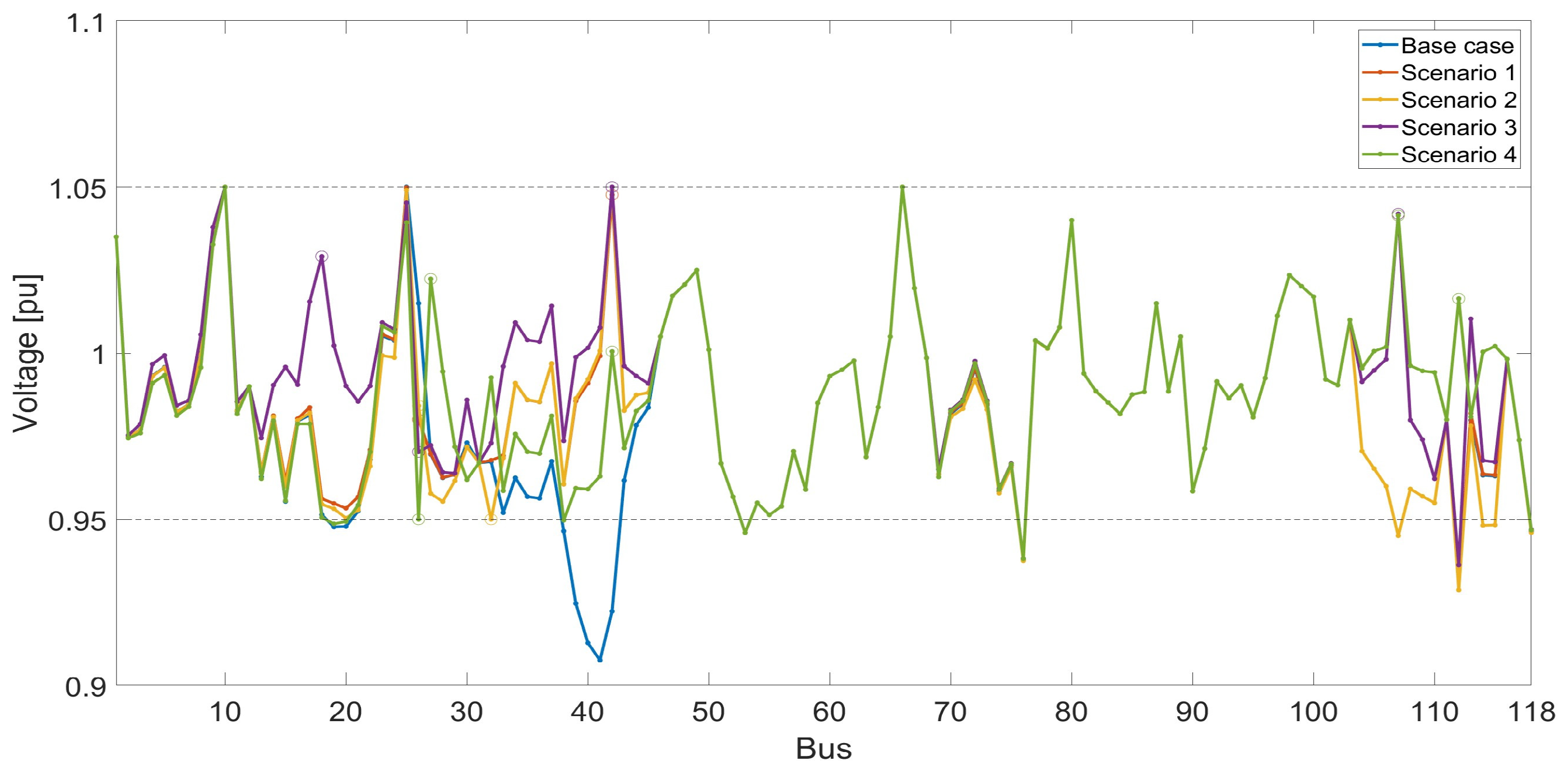

The installation of SynCon on the basis of the optimization results in

Table 3 resulted in the voltage profiles shown in

Figure 3 being obtained. The VDI

T and CCT values, calculated and measured for voltage stability and transient stability assessments, are presented in

Table 4.

As apparent from the optimization results in

Table 3 and

Figure 3, the SynCon were mainly installed in low-voltage regions. The stability assessment in

Table 4 shows that in the case of voltage stability, VDI

T decreased from 3.2844 to the range of 2.3287–2.6707 after the installation of the SynCon, with the lowest value observed for Scenario 4, which had the largest number of SynCon. However, in the case of transient stability,

did not show much difference between the scenarios, as evident from the stability index in

Table 3. Furthermore, the CCT in

Table 4 decreases from 174 ms to 137 ms.

5.2. Objective Function 2: Transient Stability Improvement

Table 5 and

Table 6 present the optimization results for enhancing transient stability for the different scenarios. Specifically,

Table 5 shows the voltage stability and transient stability indices, while

Table 6 shows the optimal installation locations and voltage settings for each scenario.

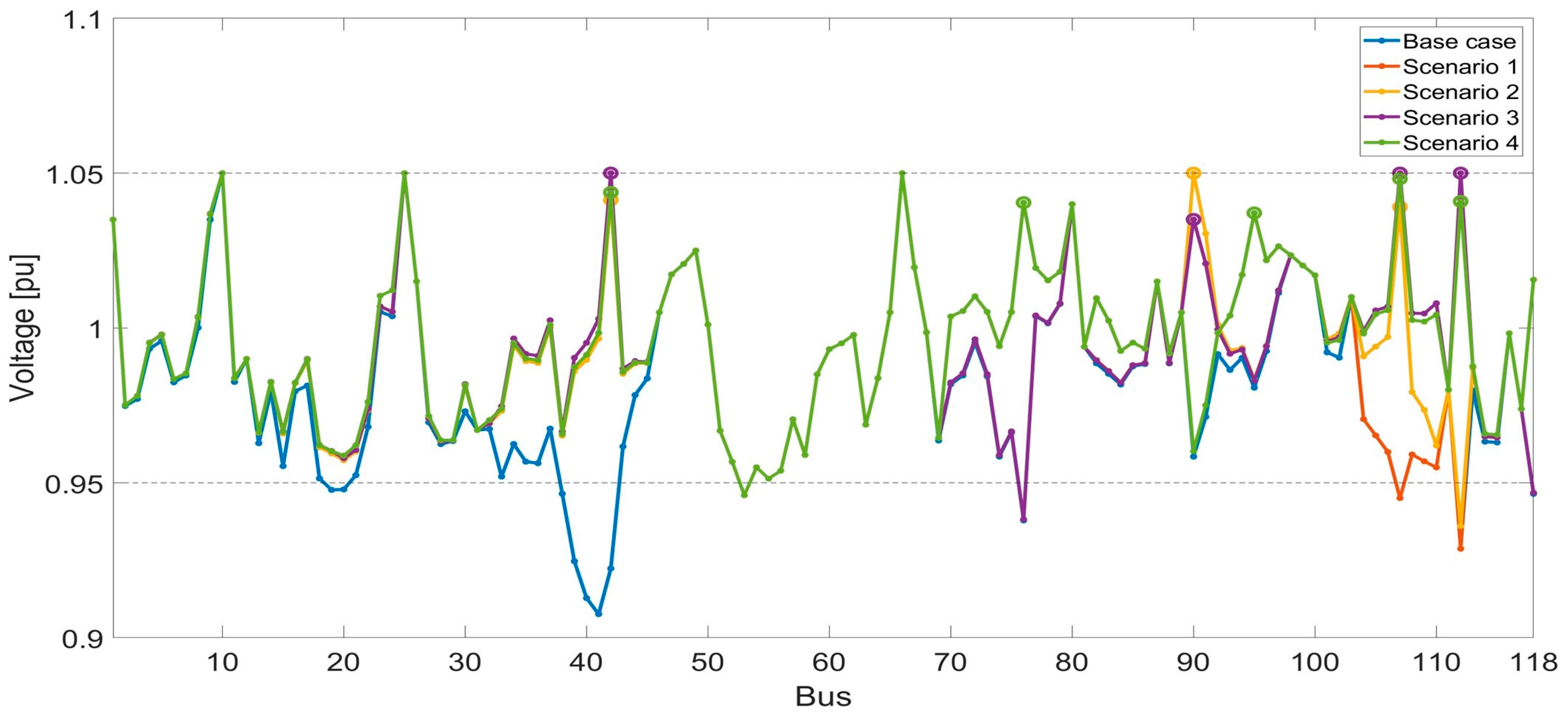

For the installation of the SynCon on the basis of the optimization results in

Table 6, the voltage profiles shown in

Figure 4 were obtained. The VDI

T and CCT values are presented in

Table 7.

As apparent from the optimization results in

Table 6 and

Figure 4, the SynCon were mainly installed near SynGen 25, which was the target SynGen for transient stability improvement. The stability assessment in

Table 7 shows that in the case of voltage stability, VDI

T did not show much difference between the scenarios, changing from 3.2844 for the base case to values in the range of 3.3818–3.4936. However, in the case of transient stability (

Table 5), the installation of SynCon resulted in

increasing from 2.5280 to the range of 3.4645–3.7000. This trend indicates that both

and the power-angle curve improved with an increase in the number of SynCon. Furthermore, the stability assessment in

Table 7 shows that the installation of SynCon increased the CCT from 174 ms to the range of 201–220 ms. In Scenario 1, where two 300 MVA SynCon were installed, the CCT reached its maximum value, namely 220 ms. However, when three or more SynCon were installed, the CCT decreased slightly, ranging between 201 ms and 215 ms.

5.3. Objective Function 3: Voltage Stability and Transient Stability Improvement

Table 8 and

Table 9 present the optimization results for enhancing both voltage and transient stability under different scenarios with different numbers and capacities of SynCon. Specifically,

Table 8 shows the voltage and transient stability indices, while

Table 9 shows the optimal installation locations and voltage settings for each scenario.

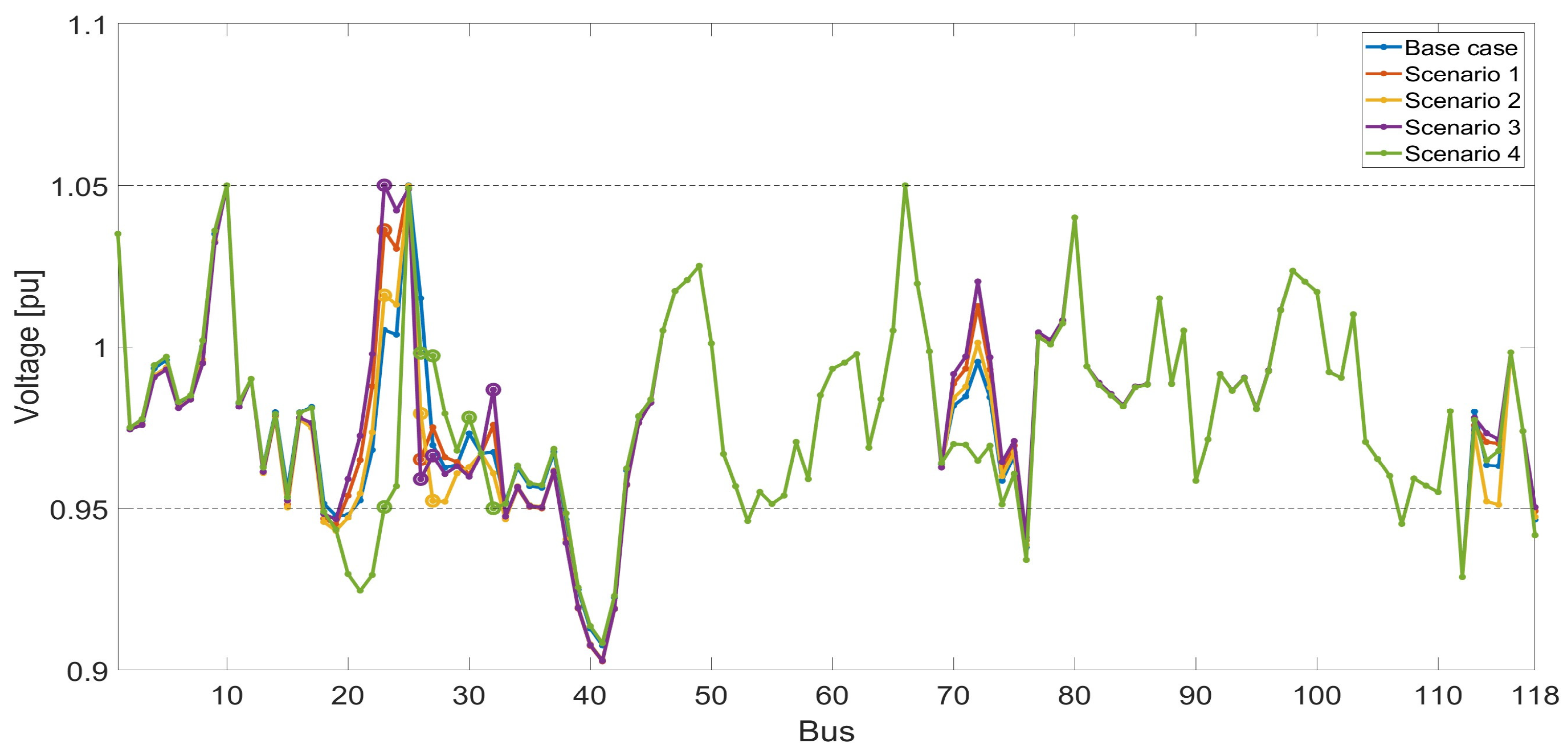

Following the installation of SynCon on the basis of the optimization results in

Table 9, we obtained the voltage profiles shown in

Figure 5. The VDI

T and CCT values are presented in

Table 10.

As evident from the optimization results in

Table 9 and

Figure 5, the SynCon were mainly installed in low-voltage regions and near SynGen 25, which was target SynGen for transient stability improvement. The stability assessment in

Table 10 shows that in the case of voltage stability, VDI

T decreased from 3.2844 to the range of 2.3197–2.8981. In the case of transient stability, as shown in

Table 10, the installation of SynCon increased

from 2.5280 to the range of 3.2675–3.4521. Furthermore, the stability assessment in

Table 10 shows that the installation of SynCon increased the CCT from 174 ms to 195–217 ms. For Scenario 1, where two 300 MVA SynCon were installed, the CCT reached its maximum value, namely 217 ms. However, when three or more SynCon were installed, the CCT decreased slightly, ranging between 195 ms and 210 ms.

5.4. Analysis and Discussion

The three objective functions considered in this paper represent different operational priorities: Objective 1 emphasizes voltage stability, Objective 2 focuses on transient stability, and Objective 3 aims to balance both aspects. The optimization results can be interpreted by examining how these priorities shape the spatial allocation and voltage setpoints of the SynCon.

For Objective 1, the optimizer consistently places SynCon in low-voltage regions or areas with low system strength and assigns relatively high voltage setpoints to them. It is also observed in

Table 3 and

Table 6 that several SynCon voltage setpoints are pushed to the upper limit of 1.05 p.u. This indicates that, under the voltage-oriented objective, the optimizer tends to place SynCon in weak-voltage areas and to utilize their available reactive power capability as much as possible to support the local voltage profile, resulting in operation close to the reactive power capability limits. In other words, the algorithm exploits the SynCon mainly as local reactive support resources: by strengthening multiple weak buses, the overall voltage profile is flattened and the voltage stability index is substantially improved. This behavior is particularly evident when the total SynCon capacity is split into several smaller units and distributed across different weak regions, which allows the reactive support to be shared spatially and reduces localized voltage drops more effectively than concentrating the same capacity at a small number of buses. However, this purely voltage-oriented placement changes the pre-fault power-flow pattern and the effective network impedance seen by SynGen 25, which can increase rotor-angle excursions for the considered fault and thereby reduce the CCT. This illustrates that improving voltage stability alone can inadvertently deteriorate transient stability for specific contingencies.

For Objective 2, the optimization naturally drives the SynCon installations toward buses electrically close to SynGen 25, which is the target generator for transient stability enhancement. In this case, the main role of the SynCon is to modify the local impedance and power-transfer conditions around the faulted generator, reducing the severity of rotor-angle swings and increasing the CCT and values. As a consequence, the transient stability margin of SynGen 25 improves significantly. On the other hand, because the optimization no longer prioritizes weak-load regions, the voltage support in remote low-voltage areas is reduced and the voltage stability index deteriorates compared with Objective 1. This outcome confirms that using SynCon solely to enhance transient stability near a specific generator can lead to less favorable steady-state voltage profiles in other parts of the system.

Objective 3 explicitly accounts for both voltage and transient stability indices through the composite objective function. As a result, the optimized SynCon configurations exhibit a mixed placement pattern: some units are located in low-voltage or low-strength areas to support the steady-state voltage profile, while others are placed near SynGen 25 to improve its transient response. The corresponding solutions provide simultaneous improvements in both VDIT and CCT relative to the base case, although neither metric is as extreme as in the single-objective cases. In this sense, the solutions obtained under Objective 3 can be interpreted as operating points on a trade-off surface between voltage and transient stability, where the chosen weight combination determines the relative emphasis on each type of stability.

These results show that the placements and voltage settings of SynCon were optimized for the intended improvement in voltage and transient stability. The SynCon installation strategy is designed to enhance the desired type of stability, and the objective functions were successfully validated. However, the improvement of one type of stability may lead to the degradation of another type of stability, and this highlights the need for optimization strategies that balance different types of stability in practical system applications. This is apparent from the results of Objective Function 3, which show that simultaneously targeting both stability types considered in this study could effectively mitigate the trade-off between them. By appropriately optimizing the placements and voltage settings of SynCon, we can improve both voltage stability and transient stability effectively.

6. Conclusions

This paper proposes an optimization method for the installation of SynCon for enhancing the stability of power systems in which SynGen are replaced by IBRs. The case study assumed a scenario in which a predefined level of inertia energy was provided to meet frequency stability requirements, as the replacement of SynGen with IBRs reduces the system inertia energy. Under these conditions, an optimization method for determining the placements and voltage settings of SynCon for enhancing voltage stability and transient stability is proposed.

These results suggest that buses with high IVSI or VDI values, or those electrically distant from existing reactive power sources, should be prioritized for SynCon installation. For transient stability, SynCon are best placed electrically close to SynGen that exhibit low Ks values, as these units are more vulnerable to rotor angle instability.

The use of the proposed optimization method for different scenarios provided significant insights into the stabilization of IBR-integrated power systems. By strategically placing and configuring SynCon, we can effectively address the challenges posed by the reduction in system stability. These findings are expected to be useful for power system planners and operators seeking to maintain stability as the generation mix undergoes changes.

While the proposed optimization method demonstrated effectiveness in improving voltage and transient stability, some limitations remain. First, the sensitivity of the optimization results to different weight configurations in the composite objective function was not systematically analyzed. A more detailed investigation of how varying the weighting coefficients affects the trade-offs between voltage and transient stability indices across a wide range of operating scenarios would provide deeper insight and practical guidance. Second, no comparative study was conducted against conventional optimization methods. Without benchmarking against existing approaches, it is difficult to quantitatively assess the relative advantages or performance improvements of the proposed method. Third, the operating losses and investment costs of synchronous condensers are not explicitly modeled in the current framework, and only technical stability metrics are considered. Incorporating cost-related terms into a multi-objective optimization framework will be essential for practical planning applications and for evaluating the economic efficiency of the optimal SynCon configuration. Future work should include direct comparisons with existing approaches to more clearly demonstrate the efficacy and robustness of the optimization framework.