Abstract

District heating (DH) is a key solution for decarbonising heat supplies, improving energy efficiency, and generating multiple economic, social, and environmental benefits. Identifying, quantifying, and monetising these benefits is crucial to assessing the impact of DH systems, comparing them with alternative heating solutions, and informing investment decisions and policy design. This paper conducts a systematic literature review to identify and classify DH benefits and to analyse the methods used to assess their economic impacts. The identified benefits are classified into four categories: energy system, end users, environment, and society, considering 123 research papers. Across all studies, 26 monetised DH benefits, but only 10 studies explicitly described the methods applied. This work demonstrates the limited but growing use of monetisation approaches for analysing DH benefits. The crucial monetisation approaches are avoided cost, net present value, hedonic pricing, levelised cost of heat, and willingness to pay. However, the absence of a harmonised framework for evaluating and monetising DH benefits limits the comparability and consistency of existing studies. Also, the study shows how emerging technologies like AI, digital twins, IoT, and cyber–physical systems are enhancing DH system performance and associated benefits. The study highlights the need for an integrated and standardised evaluation framework to assist policymakers and investors in financing efficient and sustainable DH projects.

1. Introduction

The current rise in global energy demand is a key challenge at the global level. According to EIA [1], the overall global primary energy consumption will drastically rise by 16–57% by 2050 compared to the 2022 level, considering yearly growth rates of 0.5–1.6% based on the assumptions that the global energy system will continue its growth on the current track and that there will be an absence of new policies [2]. The increasing energy demand will also lead to a rise in CO2 emissions by 32.0 Gt in 2050 [3,4]. Almost one-third of global energy consumption and 25% of CO2 are generated by buildings [5]. Moreover, 50% of buildings’ energy consumption is used for space and water heating [1]. A district heating (DH) system is one of the most feasible solutions for enhancing energy efficiency, decreasing building energy consumption and CO2 emissions, and meeting the Paris Agreement goals [6,7].

A DH system conveys hot water or steam to consumers from a centralised heating facility [8,9,10]. Nearly 90% of global energy production for DH is concentrated in China, Russia, and Europe [11]. Nearly 6000 DH networks function globally [12], with an estimated total distribution pipe length of 600,000 km, of which over 200,000 km are situated within the European Union (EU) [9]. In Europe, DH constitutes roughly 10% of the overall heat supply [10], accompanied by a comprehensive and resilient infrastructure.

DH systems have experienced evolutionary progress over time, by enhancing their performance and efficiency. By looking at DH systems, the first-generation DH (1GDH) was first commercially found in the USA in the 1880s, where steam was used as a heat carrier [13]. Subsequently, second-generation DH (2GDH) was implemented massively in Europe throughout the 1930s by exploiting superheated water as a heat transport medium [13]. Later, in the 1980s, the third-generation DH (3GDH) was significantly developed in the Scandinavian countries [13]. One of the key contributions of 3GDH was reduced heat carrier temperature (less than 100 °C) [13]. Afterwards, in the 2020s, the supply temperature was lowered to the 60–70 °C range in fourth-generation DH (4GDH). Also, sustainable self-powered thermoelectric systems can be utilised to capture waste heat in 4GDH systems, and recent advances in energy system design and cyber–physical energy networks further highlight their integration within broader energy and material system frameworks [14]. The fifth-generation DH (5GDH) can run its operation bidirectionally to fulfil end-users heating needs [13].

The DH system helps to perform the energy production unit more efficiently than an independent heating system that utilises equal resources. Also, the DH system can increase its efficiency by integrating emerging technologies, including the Internet of Things (IoT), digital twin, artificial intelligence (AI), blockchain, and cyber–physical system (CPS) [7,15]. Emerging technologies can be utilised, especially in the fourth- and fifth-generation DH systems, to improve energy efficiency and network management, reduce the energy consumption, maintenance costs, and energy bills of energy users, and foster the decarbonisation process [16].

According to the literature, DH can generate several benefits, i.e., economic, social, and environmental benefits [17,18,19,20,21], including energy efficiency, reduction in energy poverty, RES integration, lower maintenance cost, comfort, heat supply security, CO2 reduction, etc. However, not all DH systems achieve these benefits to the same extent, and the contribution of emerging technologies is still only partially explored. Several review studies have attempted to identify and categorise DH benefits, sometimes also addressing the role of innovative technologies. For instance, A. Soleimani et al. focused on hybrid heating solutions and their role in decarbonising the built environment [22], while C. Ntakolia et al. examined the use of machine learning in DH applications [23], classifying 74 studies mainly into (i) heating load/demand forecasting and (ii) design, maintenance, and scheduling. M. Jiang et al. also analysed the optimal planning and integration of sustainable heat sources in DH systems, identifying barriers to their deployment [24]. However, these review studies do not systematically analyse DH benefits nor how these benefits are economically evaluated or how emerging technologies enhance DH benefits across different operational phases.

Therefore, this paper aims to fill this gap by identifying and categorising DH benefits through a systematic literature review (SLR) with an emphasis on methodologies and techniques applied to measure and evaluate them in economic terms as well as to compare monetisation methods. Furthermore, the paper aims to better understand how different emerging technologies or innovative approaches can enhance the benefits identified in three distinct phases: design (the “design” phase of DH refers to the process of designing the DH system.), operation (the phase “operation” refers to the time during which DH operates its function), and management (the “management” phase of DH means organisation of the DH functions) of DH systems. Thus, we analyse which DH benefits can be enhanced from specific emerging technologies by improving the performance of the design, operation, and management phases of DH. To address these goals, three research questions are summarised below.

RQ1: Which DH benefits have been identified, quantified, and monetised in the current literature?

RQ2: Which monetisation methods and approaches are most frequently utilised to evaluate these DH benefits in economic terms?

RQ3: How do emerging technologies or innovative approaches enhance these DH benefits in three phases, including the design, operation, and management phases of DH systems?

The final aim of this paper is to strengthen the systemic understanding of district heating benefits and of how they can be assessed and monetised, thereby supporting policymakers and project managers in making informed decisions and in directing investments toward sustainable and high-impact projects. The paper is organised into four main sections. Section 2 is devoted to the methodology of the work, Section 3 presents the results, and Section 4 discusses the results. Section 5 is allocated to analysing DH benefits by using Emerging Technologies. In Section 6, the work is concluded.

2. Materials and Methods

An SLR was conducted with the aim of identifying and categorising the most widespread benefits of DH and comparing methods to monetise those benefits. The SLR was conducted by performing four search runs in the Scopus and Web of Science (WOS) databases and utilising several keywords. In the first search run, the keyword “district heating” was only used. In the second search run, we employed “district heating”, “economic”. During the third search run, we utilised four keywords, “society”, “energy”, “environment”, and “user”, with the second search run. In our final search (fourth search run), emerging technologies-related keywords like “cyber physical”, “digital twin”, “IOT”, “Artificial Intelligence”, and “block chain” were employed, along with the third search run. The final search runs are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Selected search runs.

This work has followed the criteria established by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to ensure transparency and replicability. The inclusion criteria comprised (i) journal articles and conference papers; (ii) studies written in English and published between 2007 and 2023 through database searches (all fields), and (iii) studies written between 2024 and 2025 through forward snowballing and the fourth search run (limited to studies within the economic field). This was performed to identify newer publications citing selected journal articles and conference papers, allowing recent and relevant studies on the same topic to be included; (iv) studies identifying at least one DH benefit; and (v) studies where DH systems incorporated emerging technologies or innovative approaches. On the other hand, exclusion criteria included (i) reviews, book chapters, editorials, short surveys, data papers, and letters; (ii) studies written in languages other than English (e.g., Chinese, Russian, Japanese, Spanish, Polish, and French); and (iii) studies that did not identify, quantify, or monetise DH benefits.

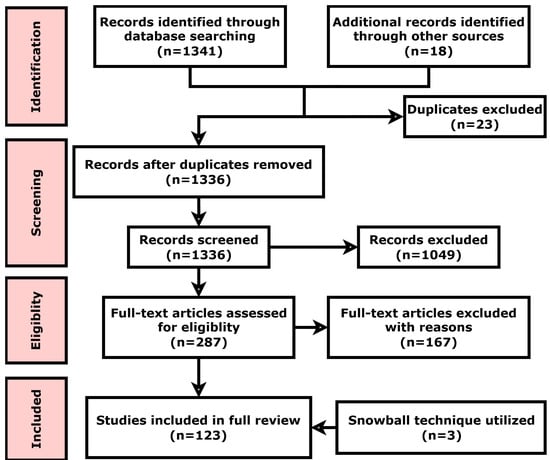

A total of 1341 research papers were identified in two databases, (i) Scopus and (ii) WOS, comprising primarily peer-reviewed journal articles and conference proceedings. Also, 18 external sources (including reports) were included because these were relevant to the scope of this study. After eliminating 23 duplicates, 1336 articles were reviewed based on their titles and abstracts. Three conditions were applied during the selection process: Yes = 1 (assigned when the paper meets the inclusion criteria), Maybe = 2 (assigned when unsure regarding the decision-making, and later, a full-text assessment is conducted), and No = 0 (assigned if the paper meets the exclusion criteria). Research papers marked as ‘Yes’ were included in the review; those marked as ‘No’ were excluded, while documents marked as ‘Maybe’ were subject to further evaluation after analysis of the full text.

After the first screening, 154 papers were marked as ‘Yes’, 133 papers as ‘Maybe’, and 1049 papers as ‘No’ and excluded. Thus, 287 papers were selected for the full-text assessment since they comply with four parameters: (a) the research has a connection with DH benefits identification, (b) the research has considered the quantification and monetisation of DH benefits, (c) the research has included a benefit monetisation method, and (d) the research utilises emerging technologies to generate DH benefits. Later through forward snowballing and the fourth search run, 29 papers published between 2024 and 2025 and related to economic studies were funded and analysed. Among these, three papers were identified as particularly relevant and have been added to the review and incorporated into the analysis. After the full-text assessment, 123 research papers were chosen for this research work. Figure 1 illustrates the PRISMA analytical diagram of the paper selection process for this review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA analytical diagram of paper selection for this review.

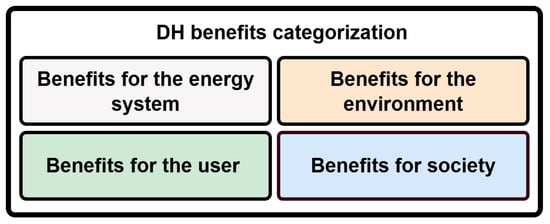

By conducting this SLR, the DH benefits reported were identified in the literature. Conceptually similar or overlapping benefits were therefore grouped under the same benefit to avoid duplication. To classify the identified benefits, we adopted the categorisation proposed by the European Network of Transmission System Operators for Electricity (ENTSO-E) benefit framework, as it is one of the most widely recognised references in the literature [25], i.e., (a) benefits for the energy system, (b) benefits for the environment, (c) benefits for the user, and (d) benefits for society [26]. Figure 2 illustrates the four categorisations for DH benefit analysis. After identifying the benefits, we analysed how they were assessed across the selected studies, distinguishing between the qualitative (I), quantitative (Q), and monetisation method (M) [26]. “Qualitative method (I)” means when DH benefits were only identified but not quantified or monetised in a research work, “quantitative method (Q)” refers to when DH benefits were quantified but not monetised further, and “monetisation method (M)” expresses when DH benefits were monetised in a research work by utilising one or more different methods. For each benefit, we determined the number of studies (frequency and percentage of all selected papers) in which it appeared according to each evaluation method. In this analysis, the frequency of the term indicates the number of reviewed studies that we identified, monetized, and quantified a particular benefit. At the same time, the percentage represents the proportion of the total articles (123 papers) analysed in which that benefit was observed. This procedure enabled us to map both the recurrence of DH benefits in the literature and the extent to which they have been identified, quantified, or monetised. Finally, for the benefits that were monetised, we examined the monetisation methods applied to estimate economic values and the results obtained. This analysis enabled us to examine various monetisation strategies in the literature and identify benchmark approaches to maximising the benefits of DH.

Figure 2.

The four categorisations for DH benefit analysis.

In addition to analysing the DH benefits and their evaluation methods, an investigation was conducted to characterise the reviewed studies further. First, we examined the DH scientific works described in the 123 selected research works, identifying the countries where DH projects were located in our analysis. Furthermore, to explore research patterns and collaborations, the VOSviewer version 1.6.19 software [27] was used to perform a bibliometric analysis of keyword co-occurrence and co-authorship networks, highlighting the main research connections across countries and thematic areas. Moreover, we analysed how emerging technologies are being integrated into DH systems to enhance the benefits previously identified. This analysis was carried out on the final set of 123 studies and focused on three main implementation phases of DH systems, namely, (a) operation, (b) design, and (c) management. For each phase, whether and how emerging technologies were investigated, such as AI, digital twins, the IoT, and CPS, can improve DH performance and increase its associated benefits.

3. Results

3.1. Geographic Variation and Scientific Studies

3.1.1. Scientific Studies

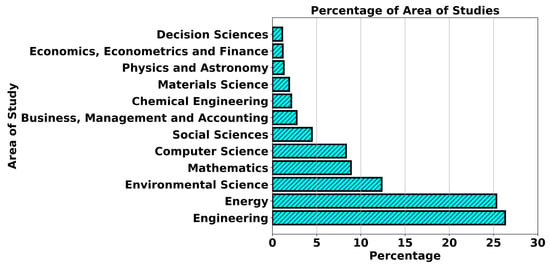

Figure 3 displays the distribution of the scientific studies included in the review across various research fields. The analysis reveals that most of the research falls into the fields of “Energy” and “Engineering”. “Environmental Science” ranks third among the most prevalent fields, accounting for almost 12% of the analysed publications. On the contrary, studies on “Economics”, “Econometrics and Finance”, “Decision Sciences”, “Social Sciences”, and “Business, Management, and Accounting” were found to be relatively limited in the reviewed research work.

Figure 3.

Scientific studies by different research fields (data obtained from Scopus).

3.1.2. Geographical Variation

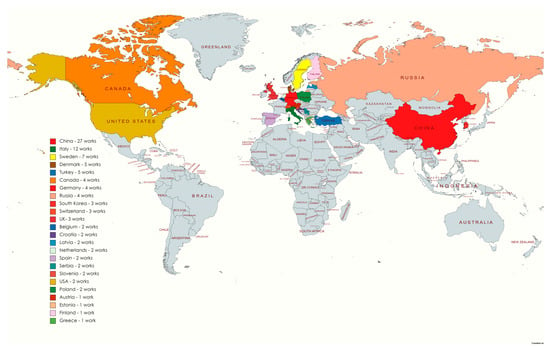

During the examination of the DH studies included in the review, most originated from Asia, Europe, and North America. Among the reviewed studies, 27 papers were produced in China, indicating the highest number of contributions. In addition, Italy followed with 12 papers, while Sweden accounted for 7 works. Denmark and Turkey each contributed five research works. Figure 4 illustrates a world map displaying the geographical distribution of the DH-related studies considered in this review.

Figure 4.

Map of DH projects-related works in different countries for this review work [28] (mapchart.net).

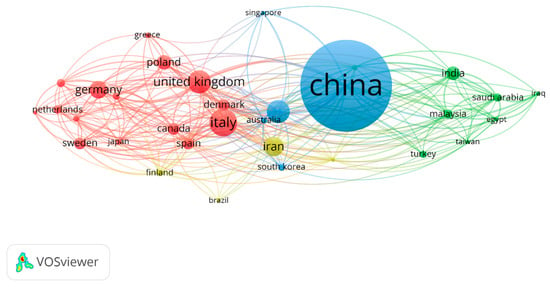

To assess the relevance of geographical variation in DH research, a bibliometric analysis was conducted using VOSviewer. The Scopus database file obtained from the keyword search was analysed to identify co-authorship networks and collaborative links among researchers from different countries. Figure 5 displays that the strongest co-authorship connections are among researchers from Italy, the United Kingdom, Germany, and Sweden, indicating well-established joint research communities in these countries. This pattern reveals that research on DH is most advanced in regions where the technology is cutting-edge and where climatic conditions and common energy and climate targets drive a strong and sustained demand for efficient and effective heating systems. Countries such as (i) Sweden and (ii) Denmark, known for their harsh winter climates and long-standing energy policies, have developed advanced DH infrastructure and conducted research supported by significant public investment and regulatory frameworks. Conversely, nations with underdeveloped DH markets often face significant upfront investment cost (capital expenditures) barriers that limit nationwide implementation and research capabilities. The concentration of DH research in economically and technologically advanced countries indicates their better institutional capacity and the growing importance of DH systems in their energy and climate strategies. Figure 5 illustrates the co-authorship relationships among countries’ researchers participating in DH research.

Figure 5.

Co-authorship connections between countries in the DH sector researchers (data obtained from Scopus and analysed with VOSviewer). The node size indicates the number of publications, and the link thickness represents the strength of collaborations. China (blue colour) has the highest research output, while European countries, particularly Italy (red colour), the United Kingdom (red colour), Germany (red colour), Denmark (red colour), and Sweden (red colour), form the most interconnected collaborative network (in the credit of VOSviwer.com [27]).

3.2. Benefits of the DH System

After analysing the literature, we identified and grouped DH benefits into four categories i.e., (a) benefits for the energy system, (b) benefits for the environment, (c) benefits for the user, and (d) benefits for society. In the next sections, we present the results for each category of benefits.

3.2.1. Benefits for the Energy System

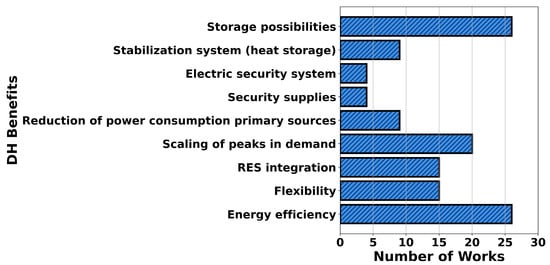

DH systems play a crucial role in energy systems by offering several benefits. Figure 6 illustrates 92 research works which identified DH benefits for energy systems.

Figure 6.

DH benefits for energy systems obtained from 92 research works.

We found several benefits from the literature, including “energy efficiency”, “flexibility”, “RES integration”, “scaling of peaks in demand”, “reduction of power consumption primary sources”, “security supplies”, “electric security system”, “stabilisation system”, and “storage possibilities”. “Energy efficiency” was identified as a benefit in 26 research papers, of which 5 quantified it, 1 monetised it, and the remaining studies only mentioned it qualitatively. Moreover, “flexibility” was quantified in 4 studies, and none of them monetised, while 11 papers identified it as a benefit. Furthermore, “RES integration” was recognised in a total of 15 works, where this benefit was identified 5 times, quantified 6 times, and monetised 4 times. “Scaling of peaks in demand” was identified as a key benefit in 20 studies; 14 of these quantified it and 6 identified it. The benefit “reduction of power consumption from primary sources” was reported in 9 times; specifically, 1 study applied the “avoided cost” method to monetise it, 5 quantified it, and 3 identified it qualitatively. “Security supplies” was identified as a benefit in 4 studies, of which 1 monetised it. Four studies recognised “electric security systems” as an essential benefit; among these, 1 monetised it and 3 identified it qualitatively. The benefit “stabilisation system” appeared in 9 studies, including 8 that identified it and 1 that quantified it. Finally, “storage possibilities” emerged as the most frequently reported benefit for the energy system, being discussed in 26 studies, the same as “Energy efficiency”. It was monetised in 4 papers, quantified in 12, and identified qualitatively in 10. More analysis of DH system benefits for the energy system is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Analysis of DH system benefits for the energy system.

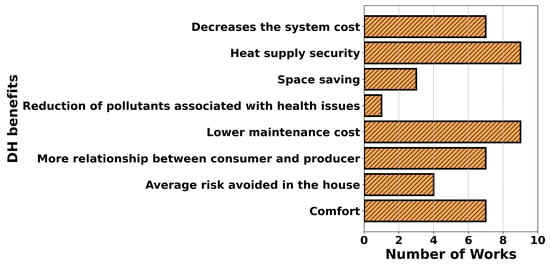

3.2.2. Benefits for the End User

We identified various DH benefits for the end user in 38 research works, including “comfort”, “average risk avoided in the house”, “more relationship between consumer and producer”, “lower maintenance cost”, “reduction of pollutants associated with health issues”, “space saving”, “heat supply security”, and “decreased system cost”. Figure 7 shows various DH benefits for the end user identified from different research works.

Figure 7.

Various DH benefits for the end user obtained from 38 research works.

Specifically, “comfort” was recognised as a benefit in seven research articles, quantified in two works, and monetised in two studies employing the “willingness to pay (WTP)” methodology and in one study employing the “hedonic pricing” methodology, respectively. Additionally, “average risk avoided in the house” was recognised in four studies and monetised once using the WTP method. The benefit “more relationship between consumer and producer” was identified in six studies, with one instance of quantification. “Lower maintenance cost” emerged as a benefit in nine papers, but none of them monetised or quantified it. In addition, “reduction of pollutants associated with health issues” was identified in one study, but no study quantified and monetised it. “Heat supply security” was recognised as a DH benefit for end users in nine studies, although it was not further monetised or quantified. Similarly, “space saving” was identified in three papers. Finally, “decreasing the system cost” was identified as an important benefit in seven studies and monetised in four of them. All analyses of DH benefits for end users are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summarised DH Benefits for the end user.

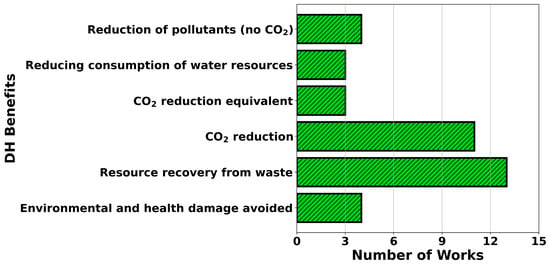

3.2.3. Benefits for the Environment

We identified various benefits for the environment associated with the use of DH systems in 35 studies included in the review. Benefits to the environment include “environmental and health damage avoided”, “resource recovery from waste”, “CO2 reduction”, “CO2 reduction equivalent”, “reduced consumption of water resources”, and “reduction of pollutants (no CO2)”. Figure 8 displays several DH benefits for the environment acquired from several research works.

Figure 8.

Several DH benefits for the environment acquired from 35 research works.

In detail, “environment and health damage avoided” was identified as a benefit in four studies, with one case quantified and one monetised using the “avoided cost” method. “Resource recovery from waste” was recognised in 13 studies; among these, 3 quantified the benefit and 2 monetised it. “CO2 reduction” emerged as a key DH benefit for the environment, identified in 11 studies; it was the second most frequently reported benefit for the environment, and 8 studies quantified it and 3 identified it. Moreover, “CO2 reduction equivalent” was quantified in three studies but not monetised further. Similarly, “reducing consumption of water resources” was identified in three studies. In addition, “reduction of pollutants (no CO2)” was reported as a benefit in four studies, with two quantifying it and one monetising it through the “avoided cost” and “pollution tax” methods. Table 4 provides a summary of the DH environmental benefits identified in the literature.

Table 4.

Summarised analysis of DH benefits for the environment.

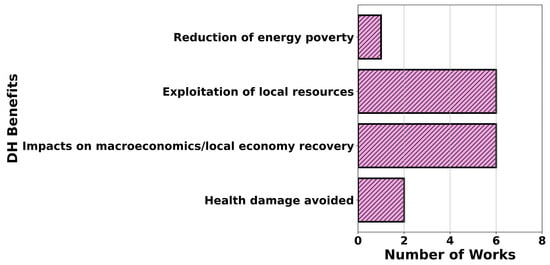

3.2.4. Benefits for the Society

Overall, we found 15 research works where researchers considered benefits to society, including “health damage avoided”, “impacts on macroeconomics/local economy recovery”, “exploitation of local resources”, and “reduction of energy poverty”. Figure 9 shows the DH benefits for society obtained from several scientific works.

Figure 9.

Numerous DH benefits for society obtained from 15 scientific works.

Moreover, “health damage avoided” was identified as a benefit in two studies, with one study monetising it using the “avoided cost” method. In addition, “impacts on macroeconomics/local economy recovery” was identified in six studies, and three of them monetised it, one by employing the software tool MOVE2social. “Exploitation of local resources” was identified as an important benefit in six studies, with one study quantifying but not monetising it. Finally, “reduction of energy poverty” was reported as a benefit in one study, but it was neither quantified nor monetised. Table 5 provides an overview of the DH societal benefits identified in the literature.

Table 5.

An overview of summarised DH benefits for society.

3.3. Comparison of Monetisation Methods for Monetising DH Benefits

Among the 123 studies selected and analysed in this work, 19 studies monetised at least one DH benefit 26 times (although 19 studies monetised at least one DH benefit, the total number of monetisation cases identified across all categories amounts to 26, since some studies monetised more than one benefit). Specifically, 12 studies monetised benefits for the energy system, 4 studies monetised benefits for the environment, 6 studies monetised benefits for the user, and 4 studies monetised benefits for society. However, only 10 studies reported the monetisation methods employed. A comprehensive analysis of these studies was conducted to evaluate and compare the various methodological approaches. Across all studies, six distinct monetisation methods were identified: avoided cost, net present value (NPV) (the difference between the current value of cash inflows and outflows over a given period of time is known as net present value (NPV) [142]), net present cost (NPC), hedonic pricing (a hedonic pricing function is a mathematical representation of the property price that takes into account three distinct types of independent variables: structural, neighbourhood, and environmental attributes [143]), levelised cost of heat (LCOH) (the levelized cost of heat (LCOH) refers to the expenses incurred in producing heat specific to a certain system, considering the temperature of the working fluid. An economic evaluation of the heat-generating system’s cost incorporates all expenses incurred throughout its lifespan, including initial investment, operations and maintenance, fuel costs, and capital costs [144]), and WTP (Willingness to pay (WTP) is the highest price that a buyer is willing to pay for a specific number of products or services [145]) (See Appendix A.7 for equations of monetisation method). These methods collectively monetised 26 times DH benefits, corresponding to 14 unique types of benefits, including energy-related, environmental, and social dimensions. For the comparative analysis, we considered the following dimensions: the specific DH benefits examined, the frequency of use of the different monetisation methods, the cost components included, the application of interest rates, additional influencing factors, and, finally, the outcomes of DH benefit monetisation. These dimensions were selected to provide a deeper understanding of how DH benefits are monetised within the literature. The factor “frequency” was considered to assess the recurrence of each monetisation method in the reviewed literature. The “cost components” were analysed to understand the different types of costs incorporated during the monetisation of DH benefits. The “interest rate” was chosen as an essential comparison factor because of its direct significance on total economic activities, such as return on investment, inflation rate, and discount rate. Subsequently, “additional influencing factors” were incorporated to discover other parameters that could impact the total cost, such as time, heat output, or energy generation, beyond purely economic concerns. The “results of monetising the benefits of DH” were assessed to determine the overall cost or cost per unit of the monetised benefits. The comparative evaluation of these monetisation approaches is summarised in Table 6.

Table 6.

Comparison of different monetisation methods employed in the literature, detailing the specific DH benefits examined, the frequency of use, the cost components included, the application of interest rates, additional influencing factors, and the resulting values.

The research reveals considerable methodological divergence in the monetisation of DH benefits. Among the studies analysed, the NPV and avoided cost approaches are the most frequently utilised. In contrast, NPC, hedonic pricing, and WTP are employed only occasionally, appearing in just one or two cases each. This pattern indicates that conventional economic and financial methodologies, rather than behavioural or stated-preference techniques, are primarily used to quantify the monetary benefits of DH. The avoided cost methodology was used to monetise DH benefits four times, considering annual heat production along with marginal and penalty costs to quantify benefits such as “reduction in energy consumption from primary sources”, “avoided environmental and health damages”, and “impact on the macroeconomy/local economic recovery”. This method quantifies the expenses that would be incurred without the intervention, thus demonstrating the economic advantages of implementing the project compared to the status quo. The NPV approach, employed six times to monetise DH benefits, used net cash flow, time in years, and discount rate assumptions to quantify benefits such as “RES integration”, “security supplies”, “electric security system”, and “resource recovery from waste”. NPV offers a flexible and well-established framework for monetising the benefits of energy systems, thanks to its flexibility in accommodating diverse metrics and time horizons. Alternative approaches were used less frequently. The NPC technique focused on investment, operation, and replacement costs to monetise “RES integration”. The hedonic pricing method, used in one study, integrated product costs, regression coefficients, and product characteristics to quantify non-monetary benefits such as “comfort”. The LCOH methodology was used in four studies, employing total expenditures, total energy production, and interest rates to monetise benefits such as “storage possibilities” and “resource recovery from waste”. Like NPV, LCOH offers a consistent framework for translating the performance of energy systems into monetary terms. The WTP method was employed twice to determine the maximum price customers would be willing to pay for benefits such as increased comfort or reduced risk in the household. This provides information on user preferences that can be useful for policy formulation and decision-making. Comparing the monetised results of various studies is inherently complex because of the heterogeneity of benefit types, cost components included, and underlying assumptions in each case. Therefore, the results were evaluated based on the cost per unit (e.g., €/kWh) or total monetised benefits, depending on the data availability. The wide variation in estimated values also indicates a significant dependence on case-specific criteria, including geographical scale, energy mix, local cost structures, and temporal assumptions. Overall, this comparative research highlights the variety of monetisation strategies and techniques employed. These findings underscore the need to standardise the economic evaluation of DH benefits by adopting uniform methodologies and variables, thereby facilitating more rigorous, transparent, and comparative assessments across projects.

4. Discussion

The main objective of this SLR was to identify and categorise the benefits of DH systems and to determine how these benefits can be measured and economically evaluated. This study placed a particular emphasis on the methodologies and techniques used to assess these benefits in the existing literature. Benefits are classified in four categories, including (a) “benefits for the energy system”, (b) “benefits for the environment”, (c) “benefits for the user”, and (d) “benefits for society” [26].

Our findings indicate that “benefits for the energy system” were identified in 92 studies, which is substantially higher than other categories of DH benefits. Across all studies, the benefits belonging to this category were quantified 68 times and monetised 26 times. The predominance of this category can be attributed to the well-established metrics available for quantifying the benefits for energy systems, which facilitate their identification and evaluation. Furthermore, there is a large amount of research devoted to the energy sector, which has contributed to greater visibility and analysis of these benefits compared to other categories.

In contrast, “benefits for the environment” were identified in 35 studies and “benefits for the end user” were identified in 38 studies. Regarding the frequency of quantifying and monetising benefits, end-user benefits were only quantified thrice but monetised 7 times, while environmental benefits were quantified 17 times and monetised 4 times. The lower frequency of these categories suggests that these characteristics are analysed less often. This discrepancy could be because of several factors, including the energy sector’s greater focus on technical innovation, limited funding, and the lack of suitable metrics for measuring benefits in the “end-user” and “environment” categories.

Additionally, “benefits to society” were identified in only 15 research works (quantified once and monetised four times), suggesting that benefits to broader society are the least prioritised and assessed. This could be due to the difficulty in quantifying and monetising social benefits and a predominant focus on technical research over social aspects.

The analysis of monetisation methods applied to assess DH benefits illustrates a clear predominance of economic–financial methods, namely, NPV, avoided cost, and LCOH, which represent the core approaches used for the monetisation of DH benefits. In detail, NPV emerges as the most versatile and widely adopted, spanning applications across benefits for the energy system, the environment, users, and society. Avoided cost is predominantly used to assess environmental and health-related benefits, while LCOH provides a techno-economic perspective that links DH system performance with cost structures. This reflects a persistent focus on cost-efficiency and investment performance in the DH evaluation frameworks. In contrast, behavioural and user-oriented approaches such as WTP and Hedonic Price are only occasionally employed, indicating the limited integration of social valuation into DH benefit assessment. The limited emphasis on monetising social benefits underscores the need for further research and the development of more robust methodological approaches in this field.

In Europe, strong institutional data, regulation frameworks for transparency, and uniform monetisation methods such as NPV, NPC, and avoided cost are widely relevant and comparable across different research papers, including Spain and the UK, but not considered in a single study in the North America (USA) and Asia. Furthermore, hedonic pricing is employed by European countries, but LCOH is particularly relevant in countries with established DH infrastructure, such as the Nordic and central European regions. However, in Asia, applicability varies widely by country. WTP is remarkably effective at eliciting consumer preferences in Asia, specifically South Korea, where no study considered WTP in Europe in our analysis.

DH systems involve high investment costs for both public and private actors, encompassing infrastructure development, network expansion or systems revamping, and the integration of renewable or waste heat sources. Therefore, demonstrating the DH benefits, as well as similar alternative heating solutions, is essential to justifying expenditures and attracting long-term capital. Quantifying and communicating these benefits, in economic terms as well, increases investor confidence and enables public authorities to prioritise DH projects in their energy-transition strategies.

The ability to identify, monetise, and report DH benefits is increasingly critical in the evolving landscape of sustainable finance. The EU Taxonomy [146] (Regulation EU 2020/852) was introduced to direct investments towards environmentally sustainable activities by defining technical screening criteria and enforcing the “Do No Significant Harm” (DNSH) principle. In this context, district heating distribution is explicitly recognised as a sustainable activity, as it meets strict requirements for energy efficiency, RES integration, and environmental protections. Therefore, the taxonomy links financial eligibility to measurable indicators of environmental and social impact, making transparency and standardised reporting essential for accessing sustainable finance.

At the same time, public authorities are responsible for creating enabling conditions for developing DH systems through policies, regulations and funding mechanisms. National and regional policies for building renovation and energy efficiency [147] illustrate how targeted incentives can align building retrofits with new generations of DH systems. Indeed, considering that the 4th GDH and 5th GDH are required to work at low temperatures, the refurbishment of houses is needed to exploit the full potential and benefits of those systems.

Given that DH networks often function as natural monopolies or oligopolies, pricing transparency and consumer protection also deserve specific attention to avoid the reduction in benefits for the final user. DH price transparency is essential to encouraging people to connect to DH networks and obtaining the full benefits it can generate. Furthermore, raising awareness of the various benefits provided by DH systems, particularly for consumers, can attract new customers, increase profitability, support customer retention, and stimulate the launch of new project pipelines.

From a research standpoint, measuring and monetising DH benefits remains a methodological challenge. While DH benefits are well identified and frequently quantified, they are only rarely monetised. Few studies evaluate benefits in economic terms, mainly because social dimensions are more difficult to assess. The predominance of engineering and energy-system analyses, with limited input from economics or social sciences, further constrains methodological progress. Advancing this field requires developing new monetisation frameworks, supported by adequate funding to attract interdisciplinary research and to improve valuation methods that capture the full spectrum of DH benefits.

Finally, the emergence of new technologies is transforming the DH sector. Tools such as blockchain, IoT, digital twins, AI, optimisation, CPS, and advanced analytics can simultaneously enhance system performance and improve the monitoring and measurement of impacts. The next section explores how such technologies can support a more comprehensive and dynamic evaluation of DH systems.

5. Benefits of DH System by Using Emerging Technologies

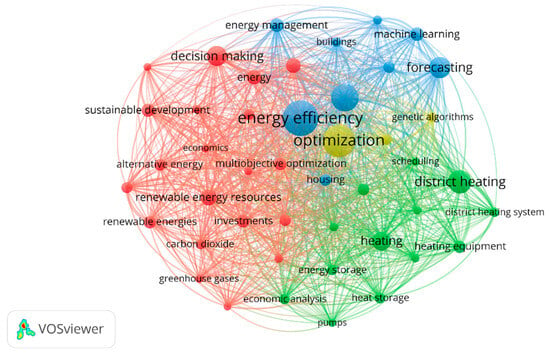

In recent years, new technologies have become quite popular in enhancing the performance of different energy systems. Therefore, we examined which specific technologies support and enhance the generation of benefits by improving the operation and management of DH systems and the prediction or quantification of benefits in a more efficient way. Those emerging technologies or techniques are AI, blockchain, digital twin, IoT, optimisation and CPS. Specifically, we can employ different emerging technologies, especially in the 4th- and 5th-generation DH systems, to improve energy efficiency and network management, reduce energy consumption, maintenance costs, and energy bills of energy users, and foster the decarbonisation process. Moreover, we can employ these technologies with net metering system to monetise benefits to improve better user experience. So, in this section, we analysed how technologies support the generation of DH benefits by improving the performance of different phases of DH, including operation, design, and management. Also, we analysed the Scopus file of our selected keywords, and we found that approaches such as machine learning, forecasting, genetic algorithm, optimisations, decision making, investments, and economic analysis are becoming key parts of research works. Figure 10 displays the different keyword connections of DH research works.

Figure 10.

Different keyword connections of DH research works (data obtained from Scopus and analysed with VOSviewer). The size of the nodes indicates the number of connections between keywords, and the thickness of the links represents the strength of those connections. Energy efficiency (blue colour), optimisation (yellowish green colour), and district heating (green colour) appeared most frequently, while economics, investments, heat storage, and carbon dioxide, among other keywords, were less prevalent (in the credit of VOSviwer.com [27]).

After analysing all selected works for this research, we found several AI (the term artificial intelligence (AI) refers to the notion of modelling intelligent behaviour using computers and minimum human interaction [148]. Precisely, to apply AI in different applications numerous AI algorithms could be employed. An AI algorithm is the programming that describes a computer to learn how to function independently [149]) algorithms that can be applied to enhanced performance and efficiency. Precisely, ANN (Artificial Neural Network (ANN) is an algorithm that is inspired from the neural network of the human brain [150]) was utilised to improve the operation phase [38,39,43,52,60,84,105,114,127,128,132] of the DH system and enhance DH benefits including “energy efficiency”, “decreases the system cost”, “flexibility”, “scaling of peaks in demand”, and “storage possibilities”. Moreover, the management phase of the DH system [51,85,86,102,120,151] was improved by employing the ANN, enhancing DH benefits such as “energy efficiency” and “lower maintenance cost”. Likewise, the design phase of the DH system was improved by utilising ANN [32,42,45,60,83,84,102,114], which improved DH benefits including “energy efficiency” and “scaling of peaks in demand”. Additionally, 9 works employed LR (LR is a statistical technique similar to linear regression [152]) to improve the operation phase [38,39,92,95], enhancing DH benefits such as “energy efficiency”, “lower maintenance cost”, and “decreases the system cost”. In the management phase [85,86,87,95], DH benefits including “decreases the system cost”, “scaling of peaks in demand”, “lower maintenance cost”, and “security of supplies” were also improved. Moreover, the design phase [76,103] was enhanced, improving DH benefits such as “storage possibilities” and “heat supply security” (See Table A1 where summarized DH system benefits by employing AI algorithms/methods).

Another emerging technology, blockchain (A blockchain is comprised of a chain of data packages (blocks). This block consists of several transactions [153]. Blockchain can be integrated to improve several applications, including the energy sector, communication sector [154], financial services (currency exchange, precisely cryptocurrency), music industry, decentralised storage and, etc.), can be utilised to support different phases of DH systems, including operation, management, and design, and enhance DH benefits. However, we only found one work [57] among selected works, which improved the DH operation [57] and achieved two DH benefits “flexibility” and “decreases the system cost” (See Table A2 for the analysis of DH system benefits by employing blockchain). Also, L. Zhao et al. have used a blockchain framework that includes Proof of Solution (PoSo) consensus, which is designed to prevent malicious behavior during benefit distribution [57]. This approach ensures mutual trust between power agents [57].

Moreover, we found five research works where researchers utilised “digital twin” (digital twin means a digital version of a physical entity; specifically, the physical entity can be mirrored in a virtual environment and continually updated data from numerous sources for different applications [155]) technology to improve DH operation [43,46,48,119,129] and enhance DH benefits, including “reduction of power consumption”, “scaling of peaks in demand”, “energy efficiency”, and “heat supply security” (See Table A3 for the analysis of DH system benefits by employing digital twin). In addition, a digital twin of the DH system is created by Z. Liu et al., which considers both human behavior and the heat dissipation of radiators [43]. From the analysis, two DH benefits are produced, such as energy efficiency and heat supply security [43]. In the management phase [119], only one benefit called “average risk avoided in the house” was identified as improved using a digital twin technology. In the design phase [48,129,131], several DH benefits can be improved, including “reduction of power consumption”, “scaling of peaks in demand”, “decreases the system cost”, and “resource recovery from waste”.

Furthermore, we found only three studies that employed IoT (Internet-linked appliances capable of computing are often referred to as the Internet-of-things (IoT) [156]) to enhance the operation phase [93,119]. These works primarily improved two DH benefits: “reduction of power consumption” and “reduction of pollutants (no CO2)” (See Table A4 for the analysis of DH system benefits by employing IOT). We also observed that CPS (Cyber-physical system (CPS) is a connection among a computer and a physical system. CPS can be employed in DH systems, automotive systems, smart grid, home automation, industrial automation, HVAC systems, security systems, water treatment facilities, and traffic control systems [157]) can support improvements across different DH phases. In the operation phase [93], the same DH benefits, “reduction of power consumption” and “reduction of pollutants (no CO2)”, were strengthened. In the management [44] and design [44] phases, only “energy efficiency” was reported as an enhanced DH benefit)” (See Table A5 for the analysis of DH system benefits by employing CPS). Moreover, X. Lin et al. conducted research where they utilised CPS and IOT [93]. By utilising both of these emerging technologies, the research shows a decrease in natural gas consumption by up to 31.2%, and operation costs during that phase are also reduced by 2.6% while achieving two distinct benefits: a reduction in power consumption and a decrease in pollutants (no CO2) [93].

The use of optimisation methods (optimization method is considered as the approach mainly dedicate to reduce or maximize an objective function in order to achieve the best decision for a problem [158]) is crucial for obtaining diverse benefits from DH systems. PSO (PSO is a well-known metaheuristic method for addressing optimization problems [159]) was applied in three studies addressing various DH phases, including the operation phase [69,131], where reported benefits included “decreased system cost”, “reduction of power consumption”, and “RES integration”. Likewise, in the management phase [69,94], three DH benefits including “decreased system cost”, “reduction of power consumption”, and “RES integration” were enhanced.

Also, four research works utilised GA (GA was presented in 1975 [160], GA is the finest method for resolving simple single-objective issues [161]) to optimise DH operation [81,115], enhancing two benefits such as “storage possibilities” and “peak demand scaling”. Moreover, the design phase [104] was benefited by utilising GA, with reported improvements in “CO2 reduction” and “storage possibilities”. In the management phase [94], GA was employed to enhance DH benefits such as “reduction of power consumption”, “comfort”, and “resource recovery from waste” (See Table A6 for the analysis of DH system benefits by utilising optimisation method according to literature).

6. Conclusions

The main objective of this work was to identify and categorise DH benefits through an SLR and to understand which methodologies are applied to monetise them. Also, we evaluated current emerging technologies in DH systems to understand how these technologies can enhance identified DH benefits by improving the performance of operation, design, and management phases. Emerging technologies and approaches, such as blockchain, IoT, digital twins, AI, optimisation, and CPS, were considered. The SLR was conducted using the Scopus and WOS databases, using four search queries with different keyword combinations. In total, 123 scientific research works were included. Furthermore, DH benefits were classified into four categories: (1) energy system, (2) end-users, (3) environment, and (4) society, following the ENTSO-E assessment framework. After analysing the literature, we observed that DH benefits are well recognised, but only a few studies monetise them or define economic assessment methods and approaches. Many of the identified benefits are evaluated qualitatively or quantitatively, but without monetary valuation. Among the 123 studies analysed, and only 10 studies explicitly described the monetisation methods employed. Few monetisation methods were found, including avoided cost, NPV, hedonic pricing, LCOH, and WTP. Our results support stakeholders and policymakers in understanding DH benefits and highlight the need for a common assessment framework to monetise them, thereby supporting decision-making processes and guiding sustainable financing.

Based on the results of this review, the next phase of the research as a future work will focus on developing a replicable and adaptive framework for the economic evaluation of DH benefits. The first step will be to group the recognised benefits into four distinct categories: (1) energy system benefits (energy efficiency, supply security, and stabilisation system); (2) environmental benefits (CO2 reduction, reduction of pollutants (no CO2), and resource recovery from waste); (3) user-related benefits (improved indoor comfort, lower maintenance cost, and improved heat supply security); and (4) societal benefits (reduction of energy poverty, and exploitation of local resources). This classification will offer a coherent taxonomy and prevent double counting or overlaps. For each benefit, existing evaluation, quantification, and monetisation methods will be reviewed to identify the most appropriate benefits, if necessary, for defining new approaches for their economic assessment. The framework will also be designed to accommodate several technical, geographic, and economic contexts, ensuring flexibility and transferability. The overall goal is to establish a simple, transparent, and replicable tool that enables consistent and comparable economic assessments of DH benefits, supporting evidence-based policymaking and guiding future research.

Moreover, as an outcome of this analysis, it is evident that emerging technologies can enhance DH system performance and maximise DH benefits across the design, operation, and management phases. DH benefits can also serve to monitor and communicate the impacts achieved. Therefore, we strongly encourage policymakers to integrate emerging technologies into DH system policies to improve system performance and environmental and social impacts. Furthermore, new DH services can emerge from these technologies, creating new business opportunities and jobs for society. Citizen awareness programmes, such as seminars and webinars, could also be promoted to encourage the adoption of DH systems integrated with emerging technologies.

This study provides a starting point for understanding the current state of the art and expanding knowledge of the DH benefits. The results identify current research gaps, particularly in monetising social and end-user benefits. Also, they help one understand the necessity of developing a comprehensive DH benefits assessment framework. Ultimately, our study aims to promote a deeper understanding of DH systems and provide guidance for their future sustainable implementation and growth.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, S.M.M.A., A.B. and E.C.; methodology, S.M.M.A., A.B. and E.C.; software, S.M.M.A.; validation, A.B. and E.C.; formal analysis, S.M.M.A.; investigation, S.M.M.A.; resources, S.M.M.A., A.B. and E.C.; data curation, S.M.M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.M.A.; writing—review and editing, S.M.M.A., A.B. and E.C.; visualisation, S.M.M.A.; supervision, A.B. and E.C.; project administration, A.B. and E.C.; funding acquisition, E.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project has received funding from the SmartGYsum project, which is the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 955614. This work has been developed within the MUSA—Multilayered Urban Sustainability Action—project, funded by the European Union—NextGenerationEU, under the PNRR Mission 4 Component 2 Investment Line 1.5: Creation and strengthening of “innovation ecosystems” and establishment of “territorial R&D leaders” cod. ECS 000037.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 1GDH | First-generation DH |

| 2GDH | Second-generation DH |

| 3GDH | Third-generation DH |

| 4GDH | Fourth-generation DH |

| 5GDH | Fifth-generation DH |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| ANN | Artificial neural network |

| Bagging | Bootstrap aggregating |

| BiLSTM | Bidirectional long short memory |

| BLO | Bi-level optimisation |

| BPNN | Back-propagation neural network |

| BT | Bagged tree |

| CNN | Convolution neural network |

| CPS | Cyber-physical system |

| CRO | Chemical reaction optimisation |

| DAO | Day-ahead optimisation |

| DDPG | Deep deterministic policy gradient |

| DH | District heating |

| DT | Decision trees |

| EIA | Energy information administration |

| ELM | Extreme learning machine |

| ENTSO-E | European network of transmission system operators for electricity |

| ETR | Extreme tree regression |

| FFNN | Feed forward neural network |

| GA | Genetic algorithm |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas emissions |

| GRU | Gated recurrent unit |

| GPR | Gaussian process regressions |

| GWO | Gray wolf optimisation |

| H2M-LSTM | Hybrid bimodal LSTM |

| HPBO | Hybrid polar bear optimisation |

| IoT | Internet of things |

| KNN | K-nearest neighbour |

| LCOH | Levelised cost of heat |

| LGBM | Light gradient boosting model |

| LR | Logistic regression |

| LSTM | Long-short term memory |

| MILP | Mixed-integer linear programming |

| MLP | Multi-layer perceptron neural network |

| MLR | Multinomial logistic regression |

| MOGA | Multi-objective genetic algorithm |

| MPC | Model predictive control |

| NLO | Non-linear optimisation |

| NPC | Net present cost |

| NPV | Net present value |

| NuSVR | Nu-support vector regression |

| RF | Random forest |

| RL | Reinforcement learning |

| RNN | Recurrent neural networks |

| RT | Regression tree |

| SLR | Systematic literature review |

| SG | Stochastic gradient |

| SVC | Support vector classifier |

| SVM | Support vector machine |

| SVR | Support vector regression |

| PassAgg | Passive-aggressive regression |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PoSo | Proof of Solution |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimisation |

| TCN | Temporal convolution neural network |

| TSRO | Two-stage robust optimisation |

| WTP | Willingness to pay |

| WOA | Whale optimisation algorithm |

| WOS | Web of science |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Table A1.

DH system benefits by employing AI algorithms/methods.

Table A1.

DH system benefits by employing AI algorithms/methods.

| Algorithms/Methods | Ref. | DH Benefit | Improvement Sector of DH | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANN | [32,38,39,42,43,45,46,51,52,60,83,84,85,86,102,105,114,120,127,128,132,151] | Energy Efficiency, Flexibility, Comfort, Decreases the system cost, Scaling of peaks in demand, Storage possibilities, Average risk avoided in the house, Lower maintenance cost, Environmental and health damage avoided | Operation | [38,39,43,46,52,60,84,105,114,127,128,132] |

| Management | [51,85,86,102,120,151] | |||

| Design | [32,42,45,60,83,84,102,114] | |||

| ADABOOST | [37,103] | Energy efficiency, Storage possibilities, Heat supply security | Operation | [37,103] |

| Design | [103] | |||

| Autoregression | [77] | Scaling of peaks in demand | Operation | [77] |

| Bagging | [37] | Energy Efficiency | Operation | [37] |

| Bayesian Ridge | [103] | Storage possibilities, Heat supply security | Design | [103] |

| BiLSTM | [77,85] | Scaling of peaks in demand | Operation | [77] |

| Management | [85] | |||

| Boosted Trees | [103] | Storage possibilities, Heat supply security | Design | [103] |

| BPNN | [40,42,102] | Stabilisation system | Management | [102] |

| Design | [42,102] | |||

| Operation | [40] | |||

| BT | [103] | Storage possibilities, Heat supply security | Design | [103] |

| CNN | [36,37,127] | Heat supply security, Energy Efficiency | Operation | [36,37,127] |

| DEEP RL | [94] | Reduction of power consumption, Comfort, Resource recovery from waste | Operation | [94] |

| DeepVAR, | [41,49] | Energy efficiency | Operation | [41,49] |

| DT | [85,86,103,105] | Storage possibilities, Heat supply security, Scaling of peaks in demand | Design | [103] |

| Operation | [105] | |||

| Management | [85,86] | |||

| Elastic Net | [103] | Storage possibilities, Heat supply security | Design | [103] |

| ELM | [43,128] | Heat supply security | Operation | [43,128] |

| Extreme gradient boosting | [41,50] | Energy efficiency | Operation | [41,50] |

| Extremely randomised trees regressor ETR | [38] | Energy efficiency | Operation | [38] |

| FB-Prophet | [41,49] | Energy efficiency | Operation | [41,49] |

| FFNN | [39] | Energy efficiency | Operation | [39] |

| GPR | [116] | Storage possibilities, CO2 reduction, Exploitation of local resources | Operation | [116] |

| KNN | [36,85] | Scaling of peaks in demand | Operation | [36] |

| Management | [85] | |||

| Lasso Regression | [103] | Storage possibilities, Heat supply security | Design | [103] |

| Least Angle | [103] | Storage possibilities, Heat supply security | Design | [103] |

| LGBM | [127] | Heat supply security | Operation | [127] |

| LSTM | [36,49,50,77,85,92,103,127] | Scaling of peaks in demand, Storage possibilities, Heat supply security, Reduction of power consumption, Resource recovery from waste | Design | [103] |

| Operation | [36,49,50,77,92,127] | |||

| Management | [71] | |||

| LR | [38,39,76,85,86,87,92,95,103] | Scaling of peaks in demand, Storage possibilities, More relationship between consumer and producer, Reducing consumption of water resources | Design | [76,103] |

| Operation | [38,39,92,95] | |||

| Management | [85,86,87,95] | |||

| GRU | [92] | Reduction of power consumption, Resource recovery from waste, | Operation | [92] |

| H2M-LSTM | [103] | Storage possibilities, Heat supply security | Design | [103] |

| MLP | [36,49,85,103,123] | Storage possibilities, Heat supply security, Lower maintenance cost, | Design | [103] |

| Operation | [36,49,123] | |||

| Management | [85,123] | |||

| MLR | [39,86] | Energy efficiency, Scaling of peaks in demand | Management | [86] |

| Operation | [39] | |||

| Multilayer perceptron | [41] | Energy efficiency | Operation | [41] |

| NuSVR | [37] | Energy Efficiency | Operation | [37] |

| RBFNN | [40] | Stabilisation system | Operation | [40] |

| RF | [36,50,85,86,92,103,127,162] | Energy efficiency, Storage possibilities, Heat supply security, Reduction of power consumption | Design | [103] |

| Operation | [36,50,92,127,162] | |||

| Management | [85,162] | |||

| RL | [82] | Scaling of peaks in demand, CO2 reduction, Health damage avoided | Operation | [82] |

| RNN | [37,49] | Energy Efficiency | Operation | [37,49] |

| RT | [39,50] | Energy efficiency | Operation | [39,50] |

| SARIMA | [79] | Scaling of peaks in demand | Operation | [79] |

| SVC | [85] | Scaling of peaks in demand | Management | [85] |

| SVM | [37,38,39,43,45,81,84,89,92,105,127,151,162] | Energy efficiency, Scaling of peaks in demand, Storage possibilities, Reduction of power consumption, Resource recovery from waste, Heat supply security | Operation | [37,38,39,43,84,92,105,127,162] |

| Management | [151,162] | |||

| Design | [45,84] | |||

| SVR (poly, linear, rbf) | [37,41,103] | Energy efficiency, Storage possibilities, Reduction of power consumption, Resource recovery from waste | Design | [103] |

| Operation | [37,41] | |||

| SVR | [40] | Energy efficiency | Operation | [40] |

| SG | [103] | Reduction of power consumption, Resource recovery from waste, Storage possibilities | Design | [103] |

| TCN | [37] | Energy Efficiency | Operation | [37] |

| PassAgg | [37] | Energy Efficiency | Operation | [37] |

| Xgboost | [36,37,40,42,49,151] | Stabilisation system, Energy Efficiency | Operation | [36,37,49] |

| Design | [151] | |||

| Management | [42] |

Appendix A.2

Table A2.

Analysis of DH system benefits by employing Blockchain.

Table A2.

Analysis of DH system benefits by employing Blockchain.

| Emerging Technology | Ref. | DH Benefits | Improvement Sector | Generation of DH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blockchain | [57] | Flexibility, Decreases the system cost | Operation | 5GDH |

Appendix A.3

Table A3.

Analysis of DH system benefits by employing Digital twin.

Table A3.

Analysis of DH system benefits by employing Digital twin.

| Emerging Technology | Ref. | DH Benefits | Improvement Sector | Generation of DH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital twin | [48] | Energy efficiency, Scaling of peaks in demand, Reduction of power consumption | Design, Operation, | 5GDH |

| [119] | Average risk avoided in the house | Design, Operation, Management | 5GDH | |

| [43] | Energy efficiency, Heat supply security | Operation | 5GDH | |

| [129] | Heat supply security | Design, Operation | 5GDH | |

| [47] | Energy efficiency, Flexibility, RES integration, Reduction of power consumption, Security supplies, Stabilisation system, Storage possibilities, Environmental and health damage avoided, Resource recovery from waste, Exploitation of local resources | Operation | 5GDH |

Appendix A.4

Table A4.

Analysis of DH system benefits by employing IOT.

Table A4.

Analysis of DH system benefits by employing IOT.

| Emerging Technology | Ref. | DH Benefits | Improvement Sector | Generation of DH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOT | [93] | Reduction of power consumption, Reduction of pollutants (no CO2) | Operation | 5GDH |

| [119] | Average risk avoided in the house | Design, Operation, Management | 5GDH | |

| [120] | Average risk avoided in the house, Lower maintenance cost, Environmental and health damage avoided | Management | 5GDH |

Appendix A.5

Table A5.

Analysis of DH system benefits by employing Cyber–physical system.

Table A5.

Analysis of DH system benefits by employing Cyber–physical system.

| Emerging Technology | Ref. | DH Benefits | Improvement Sector | Generation of DH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyber-physical system | [93] | Reduction of power consumption, Reduction of pollutants (no CO2) | Operation | 5GDH |

| [44] | Energy Efficiency | Management, Design | 5GDH |

Appendix A.6

Table A6.

DH system benefits by utilising an optimisation method according to literature.

Table A6.

DH system benefits by utilising an optimisation method according to literature.

| Optimisation Algorithm/Method | Ref. | DH Benefits | Improvement Sector of DH | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MILP | [56,75,104,108] | Flexibility, Scaling of peaks in demand, More relationship between consumer and producer, Heat supply security, Resource recovery from waste, CO2 reduction, Impacts on macroeconomics/local economy recovery, Storage possibilities, RES integration | Operation | [56,75,108] |

| Design | [104,108] | |||

| MOGA | [73] | RES integration, Storage possibilities, Lower maintenance cost, Decreases the system cost | Operation | [73] |

| Design | [73] | |||

| PSO | [69,94,131] | RES integration, Reduction of power consumption, Decreases the system cost, Reduction of power consumption, Comfort, Resource recovery from waste | Operation | [69,131] |

| Management | [69,94] | |||

| GA | [81,94,104,115] | Reduction of power consumption, Comfort, Resource recovery from waste, Scaling of peaks in demand | Management | [94] |

| Operation | [81,115] | |||

| Design | [104] | |||

| GWO | [94] | Reduction of power consumption, Comfort, Resource recovery from waste | Management | [94] |

| WOA | [94] | Reduction of power consumption, Comfort, Resource recovery from waste | Management | [94] |

| DDPG | [94] | Reduction of power consumption, Comfort, Resource recovery from waste | Management | [94] |

| HPBO | [138] | Reducing consumption of water resources | Management | [138] |

| Operation | [138] | |||

| NSGA-II | [135] | CO2 reduction | Operation | [135] |

| Management | [135] | |||

| Design | [135] | |||

| CRO | [138] | Reducing consumption of water resources | Management | [138] |

| Operation | [138] | |||

| Firefly | [45] | Energy Efficiency | Design | [45] |

| NLO | [31] | Energy efficiency | Operation | [31] |

| BLO | [98] | Stabilisation system | Operation | [98] |

| TSRO | [124] | Lower maintenance cost, Resource recovery from waste | Operation | [124] |

| MPC | [62,116] | Flexibility, Storage possibilities, Impacts on macroeconomics/local economy recovery, CO2 reduction, Exploitation of local resources | Operation | [62,116] |

| DAO | [130] | Heat supply security | Operation | [130] |

| Normal Optimisation | [30,34,41,42,48,49,53,60,61,70,71,72,78,82,84,88,89,90,91,93,95,110,114,117,119,125,132,163] | Flexibility, Decreases the system cost, Impacts on macroeconomics/local economy recovery, Reduction of pollutants associated with health issues, CO2 reduction, Average risk avoided in the house, Storage possibilities, Resource recovery from waste, Reducing consumption of water resources, Lower maintenance cost, Security supplies, Reduction of pollutants (no CO2), Reduction of power consumption, Scaling of peaks in demand, Health damage avoided, RES integration, Energy efficiency, Reduction of power consumption, Comfort | Operation | [30,34,48,49,53,60,61,70,71,78,82,84,88,89,90,91,93,95,110,114,117,119,125,132,163] |

| Management | [41,60,84,93,95,117,119] | |||

| Design | [41,48,61,70,71,78,84,93,110,114,117,129] |

Appendix A.7

Equations of monetisation method

Net present cost is denoted as ;

In Equation (A1), is investment Cost, is operational cost, and is replacement cost.

Heat production cost (avoided cost) (excl. externalities) is denoted as ;

In Equation (A2), is annual heat production, and is marginal cost of heat production, including the penalty cost for coal supply. Net present value is expressed as .

In Equation (A3), is net cash flow at time t, is the interest rate, and is time in years. Levelised cost of heat is denoted as .

In Equation (A4), is the interest rate and is time in years.

References

- Global Energy Demand to Grow 47% by 2050, with Oil Still Top Source: US EIA | S&P Global Commodity Insights. Available online: https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/oil/100621-global-energy-demand-to-grow-47-by-2050-with-oil-still-top-source-us-eia (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- U.S. Energy Information Administration—EIA—Independent Statistics and Analysis. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/pressroom/releases/press542.php (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Barco-Burgos, J.; Bruno, J.C.; Eicker, U.; Saldaña-Robles, A.L.; Alcántar-Camarena, V. Review on the Integration of High-Temperature Heat Pumps in District Heating and Cooling Networks. Energy 2022, 239, 122378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency. World Energy Outlook 2022; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Heating—Fuels & Technologies—IEA. Available online: https://www.iea.org/fuels-and-technologies/heating (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- The Paris Agreement | UNFCCC. Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Rezaie, B.; Rosen, M.A. District Heating and Cooling: Review of Technology and Potential Enhancements. Appl. Energy 2012, 93, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, J.; Delsing, J.; van Deventer, J. Improved District Heating Substation Efficiency with a New Control Strategy. Appl. Energy 2010, 87, 1996–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, S. International Review of District Heating and Cooling. Energy 2017, 137, 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Knotzer, A.; Billanes, J.D.; Jørgensen, B.N. A Literature Review of Energy Flexibility in District Heating with a Survey of the Stakeholders’ Participation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 123, 109750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- District Heating—Analysis—IEA. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/district-heating (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Buffa, S.; Cozzini, M.; D’Antoni, M.; Baratieri, M.; Fedrizzi, R. 5th Generation District Heating and Cooling Systems: A Review of Existing Cases in Europe. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 104, 504–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, H.; Østergaard, P.A.; Nielsen, T.B.; Werner, S.; Thorsen, J.E.; Gudmundsson, O.; Arabkoohsar, A.; Mathiesen, B.V. Perspectives on Fourth and Fifth Generation District Heating. Energy 2021, 227, 120520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Liu, W. An Engineering Roadmap for the Thermoelectric Interface Materials. J. Mater. 2024, 10, 748–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjoka, K.; Rismanchi, B.; Crawford, R.H. Fifth-Generation District Heating and Cooling Systems: A Review of Recent Advancements and Implementation Barriers. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 171, 112997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inderwildi, O.; Zhang, C.; Kraft, M. Cyber-Physical Systems in Decarbonisation. In Intelligent Decarbonisation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sartori, D. Guide to Cost-Benefit Analysis of Investment Projects: Economic Appraisal Tool for Cohesion Policy 2014–2020; European Commission, Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy: Brussels, Belgium, 2015; ISBN 9789279347962. [Google Scholar]

- Sorknæs, P.; Nielsen, S.; Lund, H.; Mathiesen, B.V.; Moreno, D.; Thellufsen, J.Z. The Benefits of 4th Generation District Heating and Energy Efficient Datacentres. Energy 2022, 260, 125215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, S.; Mayrhofer, J.; Schmidt, R.-R.; Tichler, R. Socioeconomic Cost-Benefit-Analysis of Seasonal Heat Storages in District Heating Systems with Industrial Waste Heat Integration. Energy 2018, 160, 868–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Energy. Energy Efficiency and Energy Security Benefits of District Energy; United States Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Djuric Ilic, D.; Trygg, L. Economic and Environmental Benefits of Converting Industrial Processes to District Heating. Energy Convers. Manag. 2014, 87, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, A.; Davidsson, P.; Malekian, R.; Spalazzese, R. Modeling Hybrid Energy Systems Integrating Heat Pumps and District Heating: A Systematic Review. Energy Build. 2025, 329, 115253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntakolia, C.; Anagnostis, A.; Moustakidis, S.; Karcanias, N. Machine Learning Applied on the District Heating and Cooling Sector: A Review. Energy Syst. 2022, 13, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Rindt, C.; Smeulders, D.M.J. Optimal Planning of Future District Heating Systems—A Review. Energies 2022, 15, 7160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Network of Transmission System Operators for Electricity. ENTSO-E Guideline for Cost Benefit Analysis of Grid Development Projects; European Network of Transmission System Operators for Electricity: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.M.M.; Croci, E.; Bagaini, A. A Critical Review of District Heating and District Cooling Socioeconomic and Environmental Benefits. In Technological Innovation for Connected Cyber Physical Spaces, Proceedings of the 14th IFIP WG 5.5/SOCOLNET Advanced Doctoral Conference on Computing, Electrical and Industrial Systems, DoCEIS 2023, Monte da Caparica, Portugal, 5–7 July 2022; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software Survey: VOSviewer, a Computer Program for Bibliometric Mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Map—Simple|MapChart. Available online: https://www.mapchart.net/world.html (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Chicherin, S.; Zhuikov, A.; Junussova, L. 4th Generation District Heating (4GDH) in Developing Countries: Low-Temperature Networks, Prosumers and Demand-Side Measures. Energy Build. 2023, 295, 113298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Min, Y.; Zhou, G.; Chen, L.; Chen, Q.; Xu, F.; Ye, Q. A Hierarchical Dispatch Method for Tri-Level Integrated Thermal and Power Systems. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 133, 107284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rušeljuk, P.; Lepiksaar, K.; Siirde, A.; Volkova, A. Economic Dispatch of Chp Units through District Heating Network’s Demand-Side Management. Energies 2021, 14, 4553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Chung, D.H.; Cho, S. Energy Cost Analysis of an Intelligent Building Network Adopting Heat Trading Concept in a District Heating Model. Energy 2018, 151, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, J.; Jia, L.; Wang, Y. Improving Room Temperature Stability and Operation Efficiency Using a Model Predictive Control Method for a District Heating Station. Energy Build. 2023, 287, 112990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.; Ying, S.; He, W.; Zhang, S.; Hu, Z.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Y. Strategy Optimization of District Energy System in Case of Sudden Demand Response or Power Accident. Energy Build. 2022, 277, 112543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Chen, D.; Peng, W. Anomaly Detection Analysis for District Heating Apartments. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. 2018, 21, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Zhang, T.; Yue, B.; Ding, Y.; Xiao, R.; Wang, R.; Zhai, X. Prediction of Residential District Heating Load Based on Machine Learning: A Case Study. Energy 2021, 231, 120950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, Q.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xue, G.; Shen, X.; Wu, X. Estimate the Daily Consumption of Natural Gas in District Heating System Based on a Hybrid Seasonal Decomposition and Temporal Convolutional Network Model. Appl. Energy 2022, 309, 118444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geysen, D.; De Somer, O.; Johansson, C.; Brage, J.; Vanhoudt, D. Operational Thermal Load Forecasting in District Heating Networks Using Machine Learning and Expert Advice. Energy Build. 2018, 162, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idowu, S.; Saguna, S.; Åhlund, C.; Schelén, O. Applied Machine Learning: Forecasting Heat Load in District Heating System. Energy Build. 2016, 133, 478–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, S. A Novel Combined Model for Heat Load Prediction in District Heating Systems. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 227, 120372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, A.; Chong, D.; Wang, J. Load Forecasting of District Heating System Based on Improved FB-Prophet Model. Energy 2023, 278, 127637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arat, H.; Arslan, O. Optimization of District Heating System Aided by Geothermal Heat Pump: A Novel Multistage with Multilevel ANN Modelling. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 111, 608–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Fan, X.; You, S.; Li, A. Data-Driven Predictive Model for Feedback Control of Supply Temperature in Buildings with Radiator Heating System. Energy 2023, 280, 128248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesendorfer, B.; Widl, E.; Gawlik, W.; Hofmann, R. Co-Simulation and Control of Power-to-Heat Units in Coupled Electrical and Thermal Distribution Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 Workshop on Modeling and Simulation of Cyber-Physical Energy Systems (MSCPES), Porto, Portugal, 10 April 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]