1. Introduction

Power transformers are critical and high-cost assets essential for the reliability of electrical transmission and distribution systems. The operational life of these assets is primarily dictated by the degradation of their cellulose insulation [

1,

2], an irreversible chemical reaction dependent on temperature, moisture, and oxygen content [

1,

3,

4,

5]. Historically, transformers were often over-rated and operated under light loads. However, modern power grids face increasing stress from grid development, the integration of volatile renewable energy sources, and the expansion of high-dynamics loads such as Electric Vehicle (EV) charging clusters [

6,

7,

8]. Along with the emergency cases, these factors force transformers to operate closer to their nameplate ratings and increasingly under temporary overload conditions [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

This new operational pattern makes the accurate monitoring and prediction of the winding hot-spot temperature (HST) and the resulting insulation aging a critical task for operators to ensure reliability and avoid expensive replacements. To manage this, system operators rely on two main international loading guides: the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) 60076-7 [

14] and the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) C57.91 [

15]. While both standards share the common goal of calculating thermal aging, they utilize fundamentally different physical models and are not interchangeable [

16].

A significant challenge arises because these standards propose different mathematical approaches for calculating the winding hot-spot gradient and insulation aging. Furthermore, while advanced dynamic thermal–hydraulic models have been proposed to account for oil viscosity and transient “overshoot” phenomena [

17,

18,

19], utility operators predominantly rely on the simplified differential equations provided in the standards, which only highlights how important the topic is.

The core problem addressed in this study is the inconsistency in risk assessment caused by these differing methodologies. Although the standards provide ranges for key parameters (such as winding exponents) that technically overlap, they prescribe different default values for identical cooling modes. Consequently, an operator assessing a specific overload event may receive contradictory safety signals depending on which standard is applied. Understanding the magnitude and direction of this divergence—specifically under modern multi-stage cooling scenarios—is essential for grid reliability.

The purpose of this study is to quantify these differences. A comprehensive MATLAB simulation framework was developed to compare the standards across a wide range of parametric and transient scenarios, including multi-stage active cooling (Oil Natural Air Natural (ONAN), Oil Natural Air Forced (ONAF), and Oil Forced Air Forced (OFAF)) [

20]. It is demonstrated that for modern transformers using Thermally Upgraded (TU) paper, the significant difference in life estimation stems solely from the physical thermal models rather than the aging mathematics.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 details the mathematical modeling methodology, defining the specific thermal differential equations and default exponent parameters used for the IEC and IEEE simulations.

Section 3 presents the simulation results, beginning with foundational parameter sensitivities and progressing to complex multi-stage cooling scenarios.

Section 4 discusses the implications of the “reversal of conservatism” finding, and

Section 5 summarizes the conclusions.

2. Modeling Methodology

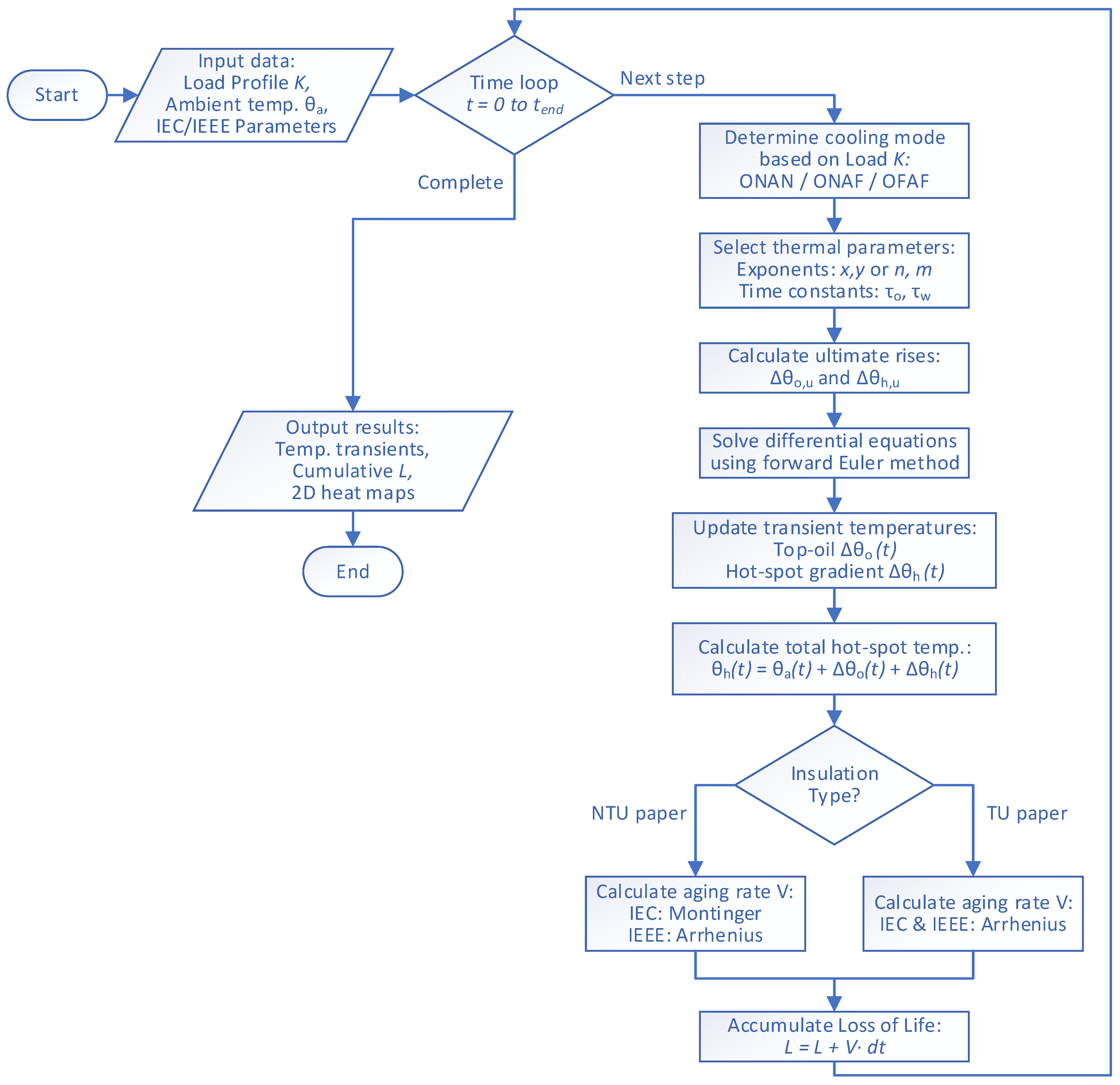

This study is based on a comprehensive thermal-aging simulation framework developed in MATLAB R2024b, which implements the transient thermal models of both the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) 60076-7 and the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) C57.91. The overall computational logic of this framework is illustrated in

Figure 1. The simulation operates on a discrete time-step basis, processing the input load profile

K(

t) and ambient temperature

θa(

t). At each calculation step, the algorithm first determines the active cooling mode (Oil Natural Air Natural (ONAN), Oil Natural Air Forced (ONAF), or Oil Forced Air Forced (OFAF)) based on the instantaneous load factor. Subsequently, the appropriate thermal parameters are selected, and the differential equations (detailed in

Section 2.1 and

Section 2.2) are solved using the forward Euler method. Finally, the instantaneous aging rate is computed based on the specific insulation type (Non-Thermally Upgraded paper (NTU) or Thermally Upgraded paper (TU)) and accumulated to determine the total Loss of Life. It is important to notice that the cooling control logic implemented in this simulation utilizes ideal load-based thresholds without hysteresis. The cooling stage transitions occur instantaneously when the load factor

K crosses the defined limits (e.g., switching from ONAN to ONAF at

K = 0.8, and to OFAF at

K = 1.2) to strictly isolate the thermal models response from any control lag.

2.1. IEC 60076-7 Model Realization

The developed MATLAB script implements the steady-state equations from the IEC 60076-7 standard, solving the transient response with a simplified first-order dynamic model using the forward Euler method.

2.1.1. Calculation of Ultimate Top-Oil Temperature Rise

Ultimate top-oil temperature rise is the steady-state top-oil temperature rise the transformer would reach if the current load (

K) was held indefinitely.

where ∆

θo,u is the ultimate top-oil temperature rise, ∆

θor is the top-oil temperature rise at rated load (

K),

R is the ratio of load losses at rated current to no-load losses,

K is the load factor (per unit of rated load), and

x is the specified oil exponent (e.g., 0.8 for ONAN).

2.1.2. Calculation of Ultimate Hot-Spot Gradient

The ultimate hot-spot gradient is the steady-state hot-spot-to-top-oil gradient for the current load:

where ∆θ

h,u is the ultimate hot-spot gradient, ∆

θhr is the hot-spot-to-top-oil gradient at rated load,

K is the load factor (per unit of rated load), and

y is the specified winding exponent (e.g., 1.3 for ONAN).

In the IEC model, the winding exponent

y in Equation (2) dictates the non-linear rise in the winding gradient. While the standard allows

y to range from 1.3 to 2.0 depending on the specific design, this study utilizes the standard default value of

y = 1.3 for ONAN and ONAF cooling modes, as typically prescribed for distribution transformers [

14]. This parameter is a primary differentiator from the IEEE model.

2.1.3. Calculation of Transient Temperatures

The transient response is calculated at each time step (

Dt) using a discrete difference equation based on the forward Euler method. The top-oil rise is calculated according to Equation (3) and the hot-spot gradient according to Equation (4):

where ∆

θo(

t) is the top-oil rise in current calculation step, ∆

θo(

t − 1) is the top-oil rise in the previous calculation step, ∆

θo,u is the ultimate top-oil temperature rise,

τo is the oil time constant [min], ∆

θh(

t) is the hot-spot gradient in the current calculation step, ∆

θh(

t − 1) is the hot-spot gradient in the previous calculation step, ∆

θh,u is the ultimate hot-spot temperature, and

τw is the winding time constant [min].

2.1.4. Calculation of Final Hot-Spot Temperature

The final hot-spot temperature is the sum of the ambient temperature and the two calculated values above:

where

θh(

t) is the final hot-spot temperature,

θa(

t) is the ambient temperature, ∆

θo(

t) is the top-oil rise temperature, and ∆

θh(

t) is the hot-spot gradient.

2.1.5. Calculation of Insulation Aging (Loss of Life)

The IEC model relative aging rate (

V) calculation for Non-Thermally Upgraded paper is based on Montsinger’s empirical ‘6-degree rule’, stating that the rate of aging doubles for every 6 °C increase above the reference temperature of 98 °C (Equation (6)), while for Thermally Upgraded paper, it is based on chemical kinetics and utilizes the Arrhenius Equation (7):

where

V(

t) is the relative aging rate, and

θh(

t) is the hot-spot temperature.

The cumulative Loss of Life (

L) is the sum of relative aging rates for each calculation instant

t according to Equation (8):

2.2. IEEE C57.91-2011 Model Realization

The developed Matlab script implements the thermal model described in Chapter 7 of the IEEE standard [

15].

2.2.1. Calculation of Ultimate Top-Oil Temperature Rise

Ultimate top-oil temperature rise is the steady-state top-oil temperature rise the transformer would reach if the current load (

K) was held indefinitely:

where ∆

ϴTO,U is the ultimate top-oil temperature rise, ∆

ϴTO,R is the top-oil temperature rise at rated load (

K),

R is the ratio of load losses at rated current to no-load losses,

K is the load factor (per unit of rated load), and

n is the specified oil exponent (e.g., 0.8 for ONAN).

2.2.2. Calculation of Ultimate Hot-Spot Gradient

The IEEE model calculates the ultimate hot-spot gradient using the winding exponent

m. It is important to note that while the IEEE exponent

m typically ranges from 0.8 to 1.0, it is applied as

2m in the gradient calculation (Equation (10)). For this study, the standard default of

m = 0.8 is used, resulting in an effective exponent of 1.6 [

15]. Although this value (1.6) falls within the theoretical range of the IEC parameter

y (1.3–2.0), the distinct default selection (1.6 for IEEE vs. 1.3 for IEC) creates the structural divergence in risk assessment analyzed in this paper:

where ∆

ϴH,U is the ultimate hot-spot gradient, ∆

ϴH,R is the hot-spot rise over top-oil at rated load (

K),

KU is the load factor (per unit of rated load), and

m is the specified winding exponent (e.g., 0.8 for ONAN/ONAF).

2.2.3. Calculation of Transient Temperatures

The developed MATLAB script calculates the transient behavior by solving the first-order differential equations provided in the IEEE standard [

15] using a discrete difference equation based on the forward Euler method. This approach is applied to Equation (11) for top-oil rise and Equation (12) for the hot-spot gradient.

where ∆

ϴTO(t) is the top-oil rise in the current calculation step, ∆

ϴTO(

t − 1) is the top-oil rise in the previous calculation step, ∆

ϴTO,U is the ultimate top-oil temperature rise,

τTO is the oil time constant, ∆

ϴH(

t) is the hot-spot gradient in the current calculation step, ∆

ϴH(

t − 1) is the hot-spot gradient in previous calculation step, ∆

ϴH,U is the ultimate hot-spot temperature, and

τw is the winding time constant.

2.2.4. Calculation of Final Hot-Spot Temperature

The final hot-spot temperature is the sum of the ambient temperature and the two calculated above values:

where

ϴH(

t) is the final hot-spot temperature,

θA(

t) is the ambient temperature, ∆

θTO(

t) is the top-oil rise temperature, and ∆

ϴH(

t) is the hot-spot gradient.

2.2.5. Calculation of Insulation Aging (Loss of Life)

The IEEE standard uses the Aging Acceleration Factor (

FAA) expression for relative aging rate (

V), which is presented in the IEC standard. For better clarity, in this paper all the results will be presented uniformly with use of relative aging rate (

V) and Loss of Life (

L) notation for both standards. The relative aging rate (

V) calculation in the IEEE standard utilizes the Arrhenius equation for both types of insulation paper but with different reference temperatures (

ϴH,R):

where

V(

t) is the relative aging rate,

ϴH,R is the reference temperature (95 °C for NTU and 110 °C for TU), and

ϴH(

t) is the hot-spot temperature.

The cumulative Loss of Life (

L) is a sum of relative aging rate for each calculation step—exactly as in the IEC approach, presented with Equation (8) in

Section 2.1.5.

4. Discussion

The results of this comparative study provide a detailed, quantitative answer to the uncertainties between the IEC 60076-7 and IEEE C57.91 standards. The findings confirm the working hypothesis that the standards are not interchangeable. More importantly, this work proves that the primary source of disagreement in modern transformers is not the aging mathematics, but the fundamental differences in the physical thermal models themselves. The potential effects of this are significant and depend entirely on the operational state of the transformer’s cooling system.

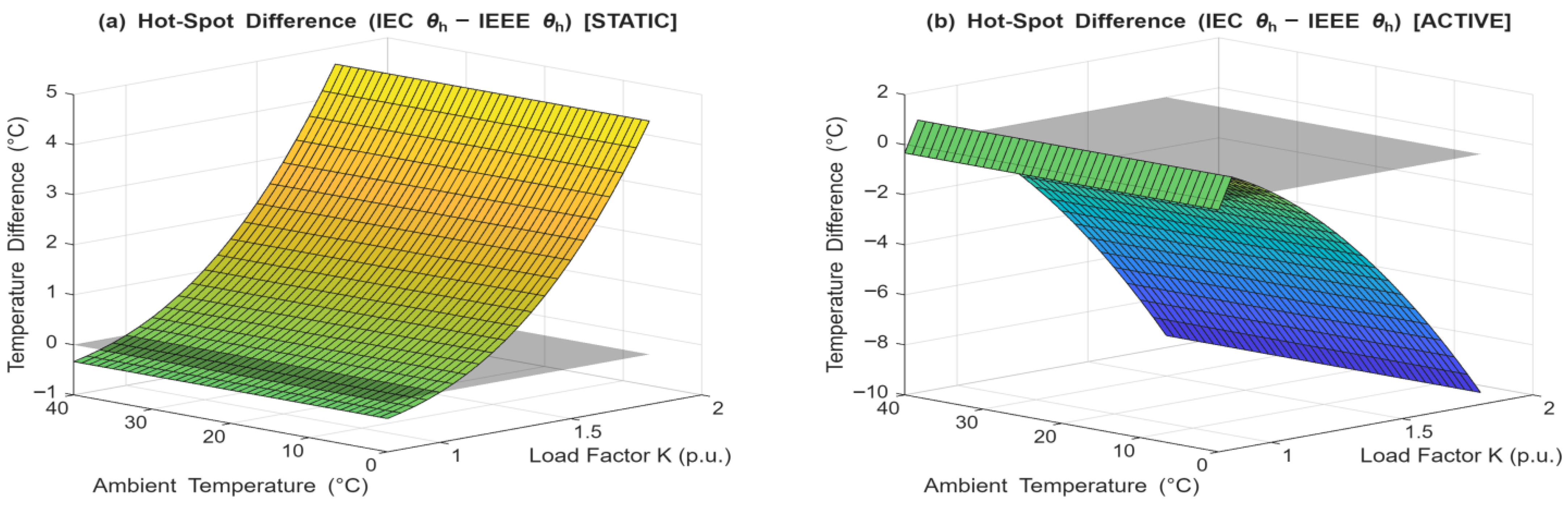

The first important finding of this paper is the “reversal of conservatism” shown in

Figure 7. The analysis of the steady-state operational maps proved that in a static ONAN (failure) mode, the IEC thermal model is more conservative, predicting higher transformer hot-spot temperatures (

Figure 7a), while in an Active Multi-Stage cooling mode, the IEEE thermal model is more conservative (

Figure 7b).

The study also revealed the cause of this reversal. In the static ONAN mode, the IEC model’s higher oil exponent (n = 0.9) is the dominant factor, leading to a higher calculated top-oil temperature. However, when the active cooling stages (ONAF/OFAF) engage, the oil exponents of both standards equalize (to n = 0.9 and n = 1.0, respectively). This neutralization of the oil model difference leaves the winding-to-oil gradient as the primary differentiator. In this case, the IEEE model’s more aggressive winding exponent (2m = 1.6) becomes the decisive factor, dominating the thermal calculation and resulting in a consistently hotter hot-spot prediction.

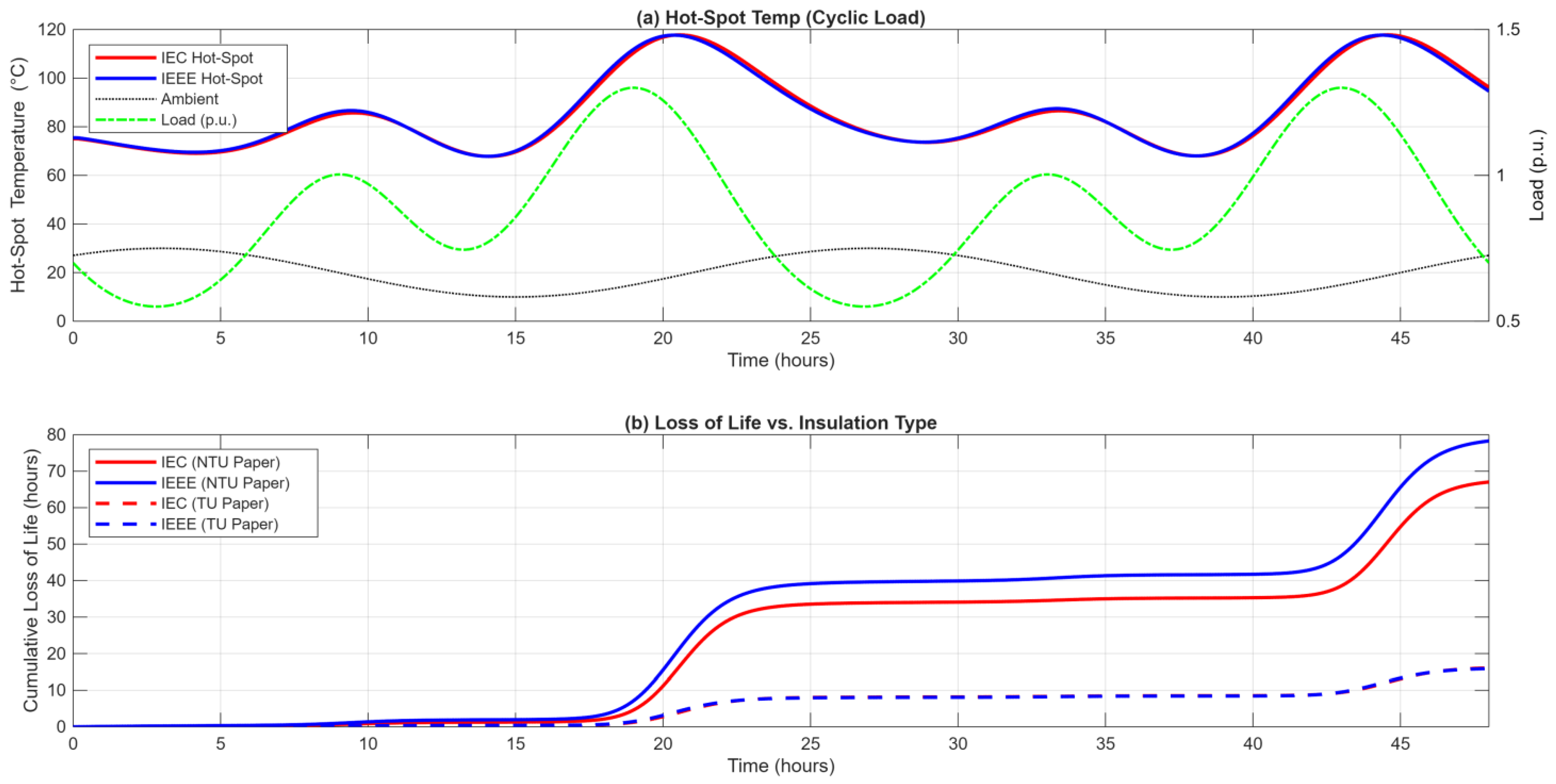

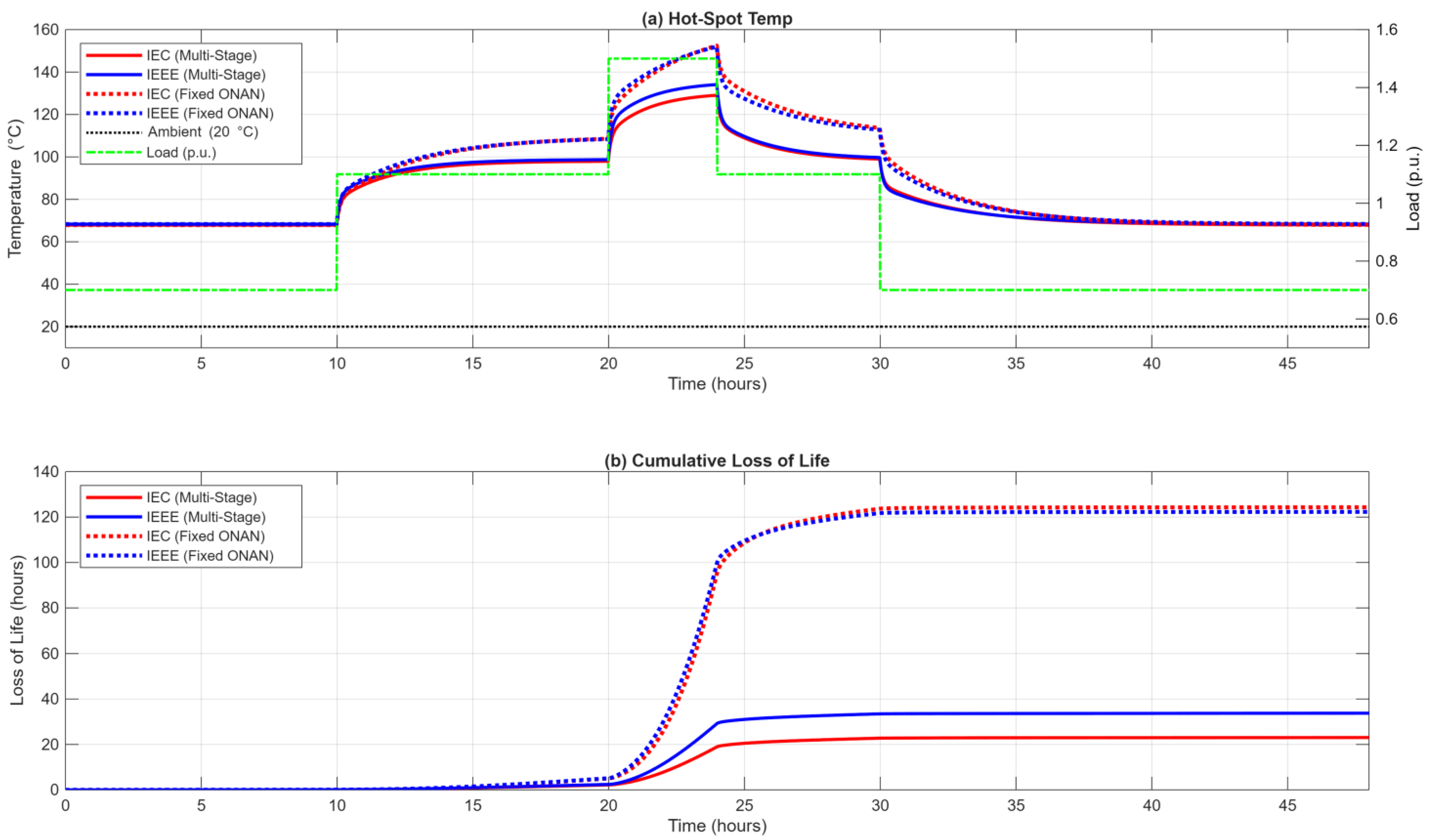

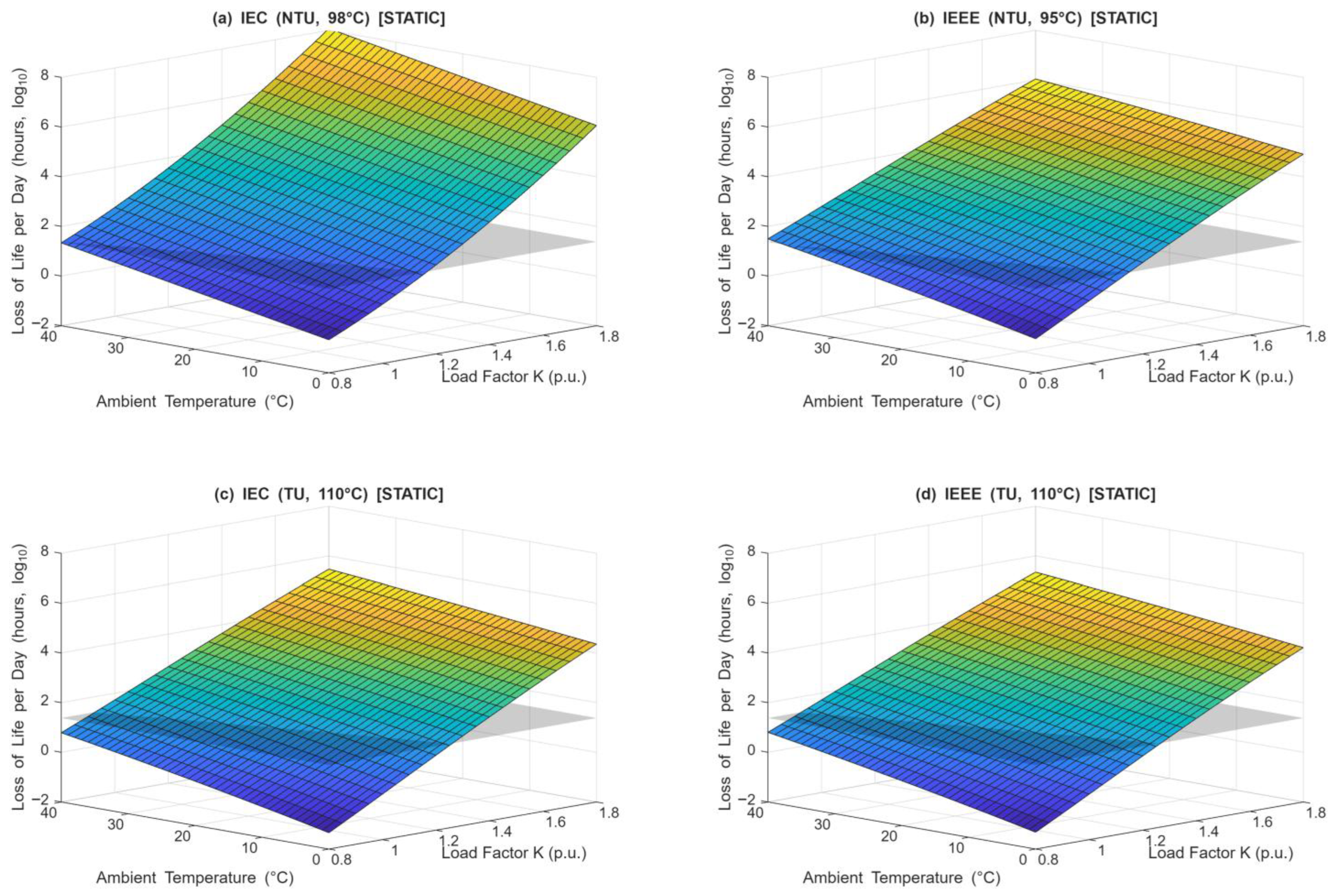

This finding has a significant implication for modern transformers using Thermally Upgraded (TU) paper. As it was shown in

Figure 8c,d and

Figure 10b, when both standards use the same Arrhenius aging equation, their Loss of Life predictions are very similar. This proves that for modern transformers the differences due to aging mathematics are secondary, and the thermal model itself is the main source of this nonconformity. The major discrepancy in aging calculations for NTU paper (

Figure 10a) confirms that the IEC “6-degree rule” is far more punitive than the IEEE Arrhenius model, but this is primarily relevant to older, NTU-equipped transformers.

The practical implications for a utility operator are two-fold. First, the conservatism of the chosen standard is not fixed but is conditional on the health of the cooling system. An operator relying on the IEEE standard (

Figure 11) might set conservative loading limits for a healthy transformer, while an operator using the IEC standard (

Figure 10a) would be far more conservative when assessing a cooling failure. Second, the 2D operational heat maps (

Figure 12) provide a practical, visual tool for this risk assessment. They confirm that for a healthy transformer, the IEEE standard defines a smaller “safe operating area” (white and green zone) than the IEC standard.

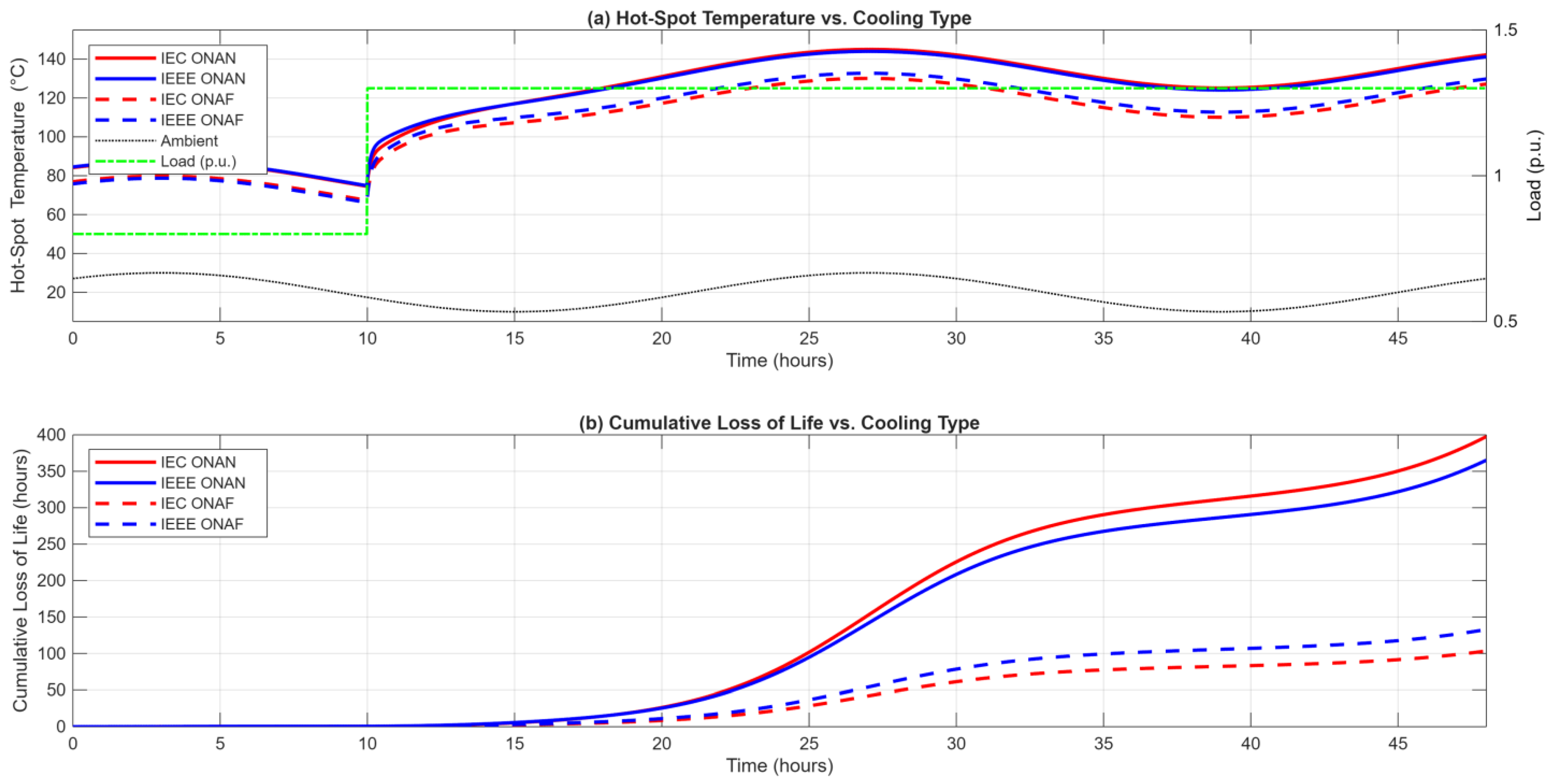

Finally, this study reinforced two other important concepts. The active vs. static cooling scenario analysis (

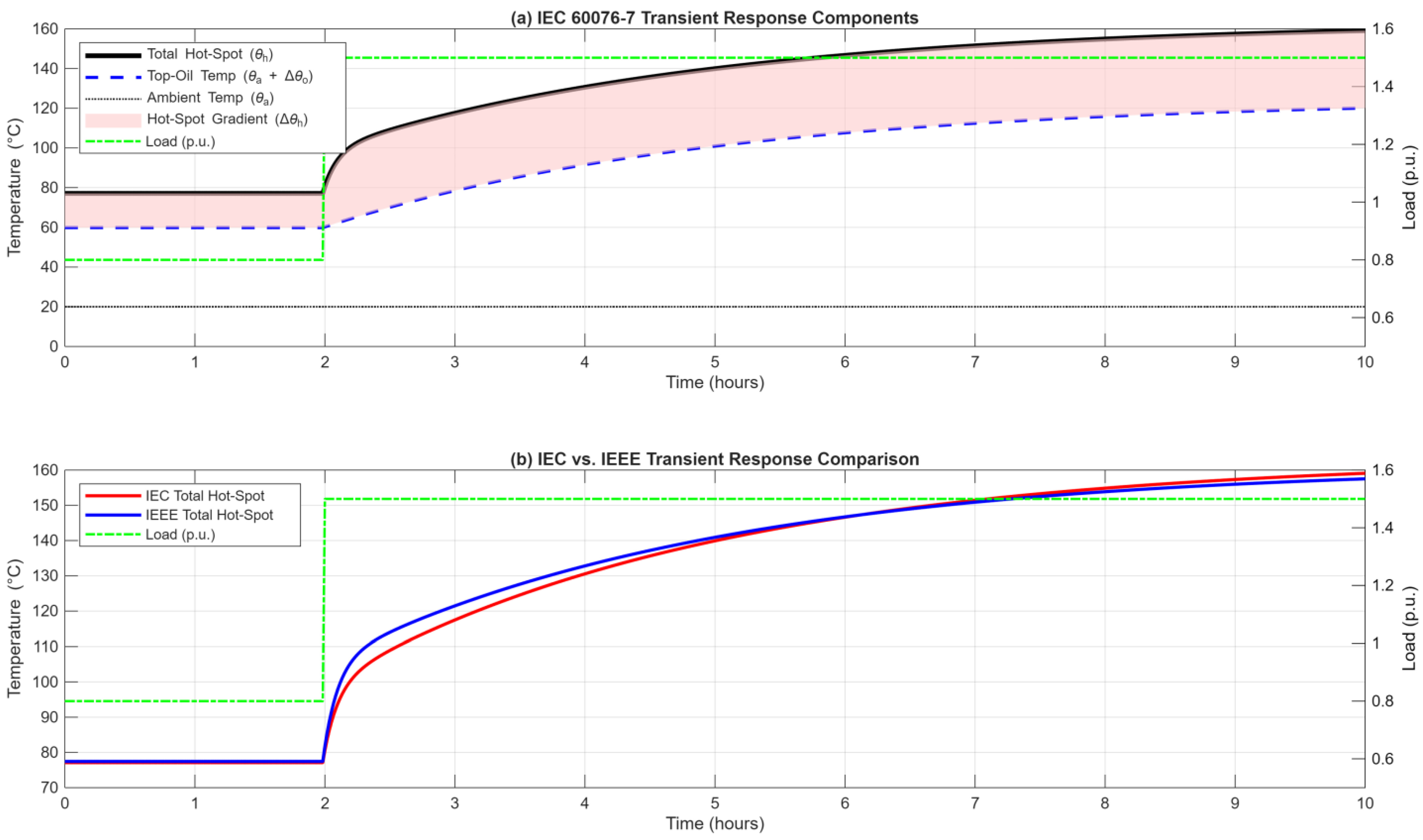

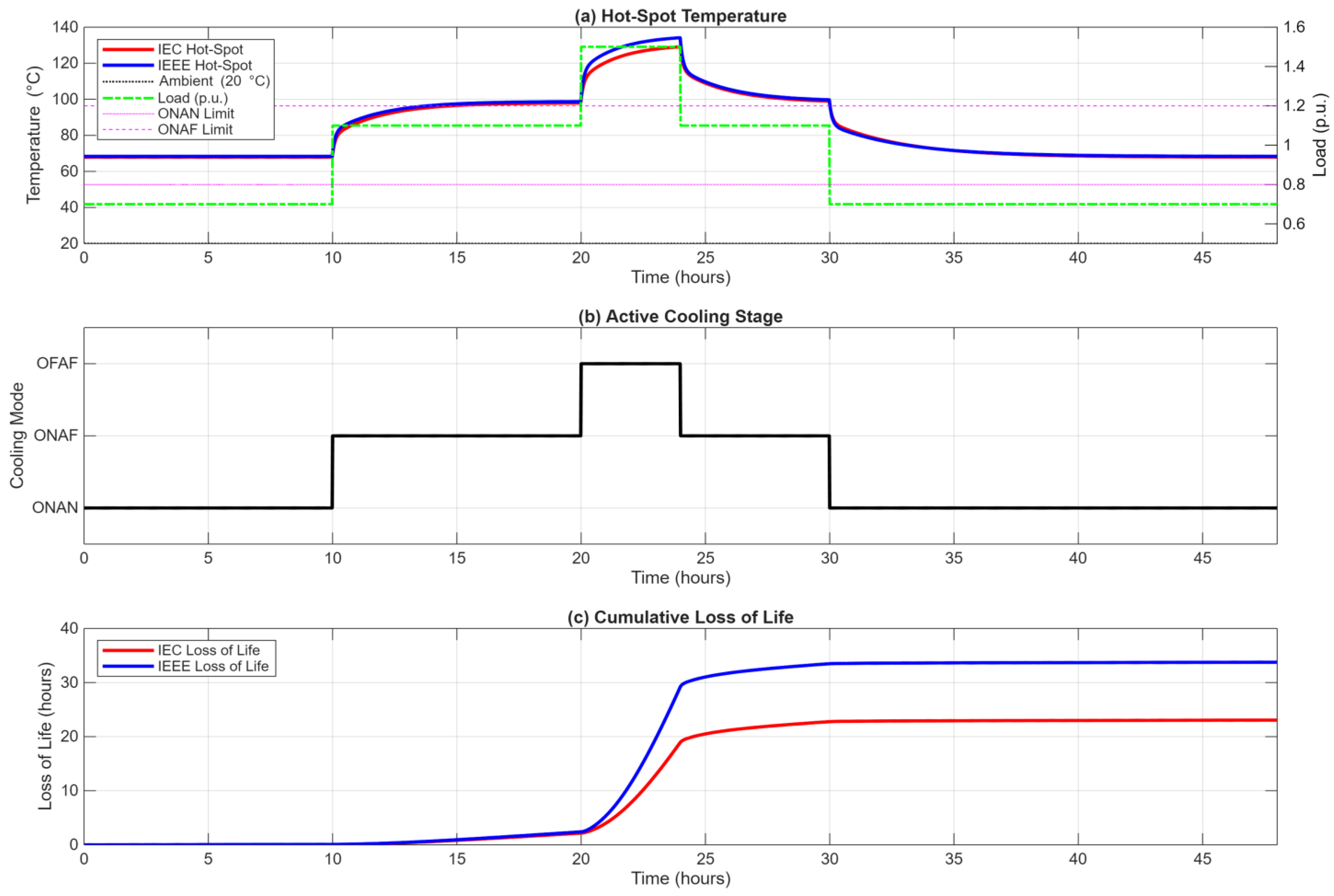

Figure 6) quantitatively proved that a cooling system failure is a high-impact event, acting as a four- to five-fold multiplier on life-loss for a 4 h overload. This validates classifying the cooling system as a safety-critical component. Furthermore, the transient analysis (

Figure 4) demonstrated the two-stage thermal response, proving that aging begins almost immediately with the short winding time constant (τ

w). This implies that short-duration, high-impact overloads (e.g., from EV charging or renewable in-feeds) must be accounted for in aging calculations, as they will consume life long before the top-oil temperature has risen significantly.

For future research, these findings should be validated against field data from transformers equipped with fiber-optic winding sensors. This would provide the necessary proofs to determine which standard’s thermal model—and specifically, which set of exponents—more accurately represents physical reality. Further modeling could also incorporate the dynamic oil-viscosity effects proposed by Susa et al. [

17,

18] to refine the transient response for these new, volatile load profiles.