Abstract

Conventional thermoelectric conversion and onboard power-generation systems struggle to meet the active-cooling requirements of hypersonic vehicles under extreme conditions. The SCO2 Brayton cycle emerges as a promising solution due to its high density, specific heat capacity, cost-effectiveness, and superior heat-transfer characteristics. This review analyzes the evolution of SCO2 Brayton cycle configurations, focusing on the following four primary types: recuperated, compression, combined, and other specialized cycles. Their working principles and processes are summarized. Current application progress is detailed across the following four key areas: cycle layout design, printed circuit heat exchangers, SCO2 heat-transfer behavior, and operational dynamics. Future research directions for SCO2-based active cooling in hypersonic applications are identified. Emphasis is placed on understanding SCO2 flow dynamics within cooling channels during transient vehicle operation and investigating component coupling effects in integrated power-generation systems.

1. Introduction

Extreme thermal loads reaching 10.0 MW/m2 are generated during the operation of hypersonic vehicle (Ma > 5) scramjet engines—the core power units—due to high-speed airflow compression and combustion [1]. This imposes critical challenges on thermal protection systems. Structural integrity and operational longevity of the engine are severely compromised under such thermal extremes, while propulsion system performance degradation may simultaneously be induced. Thus, the implementation of high-efficiency active cooling is established as an essential requirement for secured vehicle operational reliability. Substantial electrical power requirements characterize hypersonic vehicles, which incorporate critical power-intensive subsystems, such as propellant feed systems, laser-based armaments, avionics control units, and precision navigation/guidance assemblies. Stringent volume and power-to-weight ratio requirements imposed on airborne thermoelectric systems necessitate the development of power-generation units characterized by structural compactness, minimized spatial footprints, and enhanced power-to-mass metrics. This operational reality demands that accelerated investigation of next-generation thermoelectric conversion methodologies and integrated airborne power systems be conducted for hypersonic platforms functioning within extreme mission profiles.

Currently prevalent power-generation cycles include the following: Rankine cycle, organic Rankine cycle, open Brayton cycle, closed Brayton cycle, Stirling cycle, and Ericsson cycle. Superior thermoelectric conversion efficiencies ranging 20.0~40.0% and outstanding power-to-weight metrics reaching 100.0 kW/kg have been documented for closed Brayton cycle configurations in multiple research initiatives [2]. Significant reductions in density and viscosity, coupled with enhanced incompressibility and dramatic elevations in thermal conductivity and specific heat capacity, were observed in CO2 near its critical point (7.4 MPa, 304.3 K) during 1960s research. The utilization of SCO2, as a working fluid, provides integrated benefits of high density, enhanced specific heat, economic efficiency, and excellent heat-transfer performance. System operation is characterized by advantageous flow dynamics, minimized compressor work requirements, and negligible viscosity. Phase change elimination during thermodynamic processes allows for significant compression work reduction. Thus, SCO2 Brayton cycles establish unparalleled superiority in airborne power-generation applications compared with alternative cycles. Current SCO2 Brayton cycle configurations for active cooling—categorized as recuperated, compression, combined, and other specialized cycles—are systematically reviewed. This review identifies the following critical gap in the literature: the prevailing, isolated focus on thermodynamic efficiency fails to address the systems-level challenges paramount for hypersonic applications. The following three scientific questions remain unresolved: the efficiency–complexity trade-off paradox, the poorly understood dynamic coupling mechanisms among components, and the absence of a unified design paradigm. To bridge this gap, we not only provide a critical evaluation of cycle configurations but also propose a novel hierarchical modeling framework. This framework is designed to unravel component interactions and establish a structured methodology for future research, thereby defining the scientific significance and pathway for developing robust SCO2 Brayton cycles for hypersonic vehicles.

2. Configuration Review of Closed-SCO2 Brayton Cycle

2.1. Recuperated Cycle

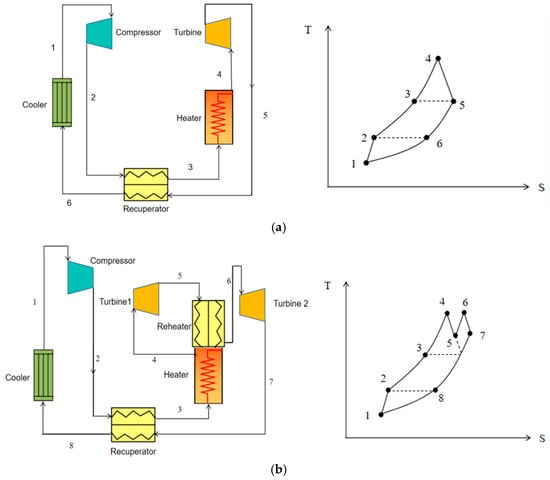

Fundamental Brayton cycle processes—adiabatic compression, constant-pressure heating, adiabatic expansion, and constant-pressure cooling—exhibit significant thermal losses through the cooler. This renders the cycle inefficient for integrated active-cooling power generation. Efficiency improvement is achieved by integrating a recuperator, defining the simple recuperated cycle. The corresponding process schematic and temperature–entropy chart appear in Figure 1a.

Figure 1.

Different recuperated cycles: (a) work flow diagram and temperature–entropy diagram for a simple regenerative cycle; (b) work flow diagram and temperature–entropy diagram for a reheat regenerative cycle.

Luo [3] applied a simple recuperated cycle model to scramjet research. Under optimal conditions, the cycle process is characterized as follows: Cooled CO2 (State 1: T1 = 305.0 K, P1 = 7.6 MPa) undergoes compressor pressurization (State 2: P2 = 32.0 MPa, T2 ≈ 380.3 K). The pressurized CO2 enters the cold side of the recuperator, where it is preheated by turbine exhaust (T5 = 520.0 K) to State 3 (T3 = 420.0 K, P3 = 32.0 MPa). The preheated CO2 then flows through the heater (simulating engine wall cooling channels), absorbing combustion chamber heat to reach State 4 (T4 = 680.0 K, P4 = 32.0 MPa). High-temperature CO2 expands through the turbine (State 5: P5 = 7.6 MPa, T5 = 520.0 K). Turbine exhaust enters the recuperator hot side, rejecting heat to State 6 (T6 = 400.0 K), and finally cools in the heat exchanger through thermal transfer with hydrocarbon fuel (returning to T1 = 305.0 K, P1 = 7.6 MPa). This completes the simple recuperated cycle. At this optimum, the system delivers 25.1 kW net power output with 16.1% thermal efficiency.

Cycle net efficiency improvement was investigated by Dostal et al. [4] through reheat–recuperated cycle development. Integration of supplementary turbine stages and reheat components enables dual-stage heat extraction from thermal sources, with corresponding process schematics detailed in Figure 1b. Research confirms that reheat insertion (positioned interstage between HP/LP turbines at primary-heating-equivalent temperatures) increases mean heat uptake temperature under equivalent T_max limitations, concurrently decreasing exhaust gas temperatures and diminishing recuperator duty requirements.

Figure 1a,b illustrate the workflows and thermodynamic characteristics of the simple recuperated and reheat–recuperated cycles, respectively. The simple recuperated cycle significantly enhances system efficiency (16.1%) by recovering heat from the turbine exhaust, while the reheat cycle further increases the average heat absorption temperature and efficiency through interstage heating. For hypersonic system design, the simple recuperated cycle is more suitable due to its structural simplicity and high reliability; although the reheat cycle offers higher efficiency, its complexity may pose integration and reliability challenges in the transient flight environment.

2.2. Compression Cycles

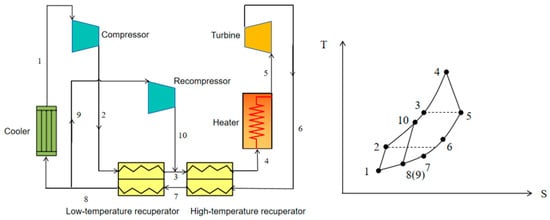

Critical-state CO2 in recuperated cycles was observed by Feher [5] to undergo discontinuous specific heat transitions. Heat capacity disparity between recuperator flow paths generates micro-regions exhibiting near-zero temperature gradients. These areas impose fundamental limitations on thermal energy recovery, ultimately reducing cycle efficiency through the established recuperator pinch point mechanism. Addressing the recuperator pinch point limitation is therefore essential for SCO2 Brayton cycle optimization. As a leading technical solution, the recompression cycle achieves markedly higher efficiency than simple recuperated systems when operating with high-grade thermal sources at elevated pressures (typically >30.0 MPa). This performance advantage has positioned it as both a predominant research direction and reference cycle design. Structurally, it integrates supplementary heat recovery and compression components—specifically an extra recuperator and recompressor—relative to basic recuperated layouts. Figure 2 details its schematic representation and thermodynamic state diagram.

Figure 2.

Work flow diagram and temperature–entropy diagram for a recompression cycle.

Kim et al. [6] applied recompression cycle modeling to scramjet research. Under optimal conditions (compression ratio 2.6, split ratio 0.3, turbine inlet temperature 823.2 K, high pressure 19.2 MPa), the cycle process operates as follows: The working fluid exiting the low-temperature recuperator (LTR) splits into two streams. The primary stream enters the cooler (State 1: T1 = 269.2 K, P1 = 7.4 MPa), undergoes main compression (State 2: T2 = 353.2 K, P2 = 19.2 MPa), and is preheated in the LTR by fluid from the high-temperature recuperator (State 7: T7 = 573.2 K, P7 = 19.3 MPa) to State 3 (T3 = 423.2 K, P3 = 19.2 MPa). The secondary stream passes through the recompressor (State 10: T10 = 393.2 K, P10 = 19.2 MPa), merging with the primary stream at State 3. The combined flow enters the high-temperature recuperator (HTR), preheated by turbine exhaust (State 6: T6 = 623.2 K, P6 = 7.4 MPa) to State 4 (T4 = 693.2 K, P4 = 19.2 MPa). After heater absorption (State 5: T5 = 823.2 K, P5 = 19.2 MPa), the fluid expands through the turbine to State 6, subsequently rejecting heat through the HTR and LTR. Simulation results demonstrate the following: 278.7 K and 284.9 K pinch-point temperature differences for LTR and HTR respectively, 95.0% recuperator effectiveness, and 44.7% thermal efficiency. This confirms the split-flow mechanism effectively mitigates recuperator pinch-point limitations, achieving significant efficiency gains over simple recuperated cycles.

The recompression cycle shown in Figure 2 effectively addresses the recuperator pinch point problem through split-flow and recompression processes, achieving a high thermal efficiency of up to 44.7% under high-temperature and high-pressure conditions. However, for hypersonic system design, the additional recuperator and recompressor in this cycle lead to a significant increase in system complexity and weight, accompanied by higher fuel consumption, which severely limits its practical application potential in airborne platforms with strict space and weight constraints.

2.3. Combined Cycle

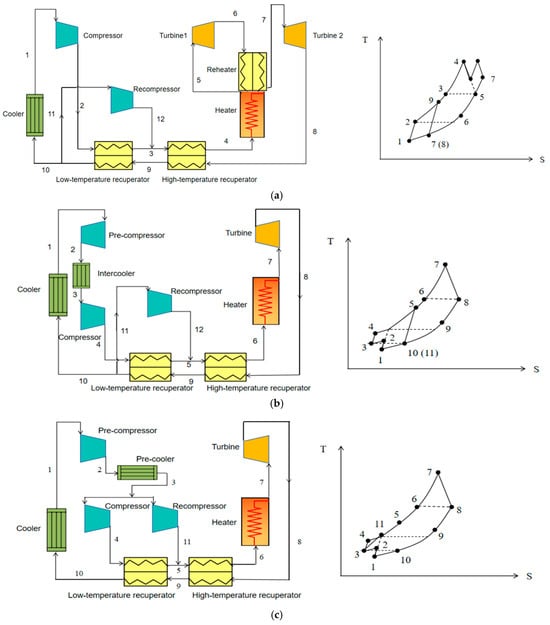

Substantial efforts have been directed toward SCO2 Brayton cycle thermal efficiency optimization, yielding multiple advanced configurations derived from fundamental cycle topologies through rigorous thermodynamic analysis and component innovation. Sarkar et al. [7] integrated operational workflows of reheat and recompression cycles to propose a reheat–recompression cycle. Their research demonstrates that under typical operating conditions (heat source temperature: 973.2 K~1023.2 K), this cycle achieves efficiencies approaching or exceeding 55%. The process flow and T-s diagram of the reheat–recompression cycle are depicted in Figure 3a. Furthermore, researchers have proposed intermediate cooling cycles and pre-compression cycles based on recompression architectures. Intermediate cooling effectively reduces compressor power consumption by 10.0~20.0% through lowering average compression temperature—significantly enhancing net efficiency (0.5~2.0%) and specific work output at elevated pressure ratios (ε > 3.0). This approach proves particularly advantageous for high-compression-ratio applications. The intercooled cycle incorporates an additional pre-cooler and pre-compressor into the recompression architecture. Unlike the recompression cycle, the CO2 stream diverted to cooling flows sequentially through the pre-cooler and pre-compressor before converging with the other stream at the low-temperature recuperator (LTR) outlet (process path: 1→2→3→4→5). The process flow and T-s diagram of the intercooled cycle are shown in Figure 3b. The pre-compression cycle utilizes identical components but differs in flow-split location. Here, CO2 passes through the LTR without splitting, proceeds to the cooler, then through the pre-compressor and pre-cooler. Flow division occurs only after exiting the pre-cooler. Subsequent processes align with standard recompression cycle operation. The pre-compression cycle schematic and thermodynamic diagram appear in Figure 3c.

Figure 3.

Different combined cycle: (a) work flow diagram and temperature–entropy diagram for a reheat recompression cycle; (b) work flow diagram and temperature–entropy diagram for an Intercooled cycle; (c) work flow diagram and temperature–entropy diagram for a pre-compression cycle.

The combined cycles shown in Figure 3, such as reheat–recompression, intercooling, and pre-compression cycles, can theoretically achieve higher thermal efficiency (e.g., the reheat–recompression cycle can reach 55.0%) or improve performance by reducing compression work (intercooling cycle). However, for hypersonic system design, these ultimate efficiency gains come at the cost of extremely high system complexity and component count. Given the stringent requirements for compactness, reliability, and weight in hypersonic platforms, the overall advantages of these complex cycles are often inferior to those of simpler cycle layouts.

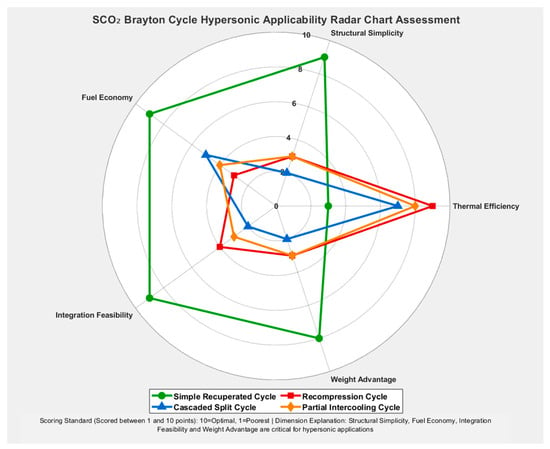

The comprehensive assessment presented in Figure 4 visually compares the four innovative SCO2 Brayton cycles across the following five critical dimensions: thermal efficiency, structural simplicity, fuel economy, integration feasibility, and weight advantage. The quantitative basis for this radar chart assessment is rigorously defined as follows: thermal efficiency is derived from theoretical maximum values reported in literature under representative hypersonic operating conditions; structural simplicity is evaluated through a composite metric of component count and control system complexity, where fewer components and simpler flow paths score higher; fuel economy is quantified by the cooling fuel mass flow rate required per unit of net power output (kg/s·kW), as established in coupled thermal management system analyses [8,9]; integration feasibility assesses the challenges associated with system volume, installation, and dynamic control under transient flight profiles; and weight advantage is determined by the system’s power-to-weight ratio (PWR in kW/kg) and total mass, based on integrated component weight analyses [9,10]. This multi-criteria framework ensures that the assessment reflects the practical trade-offs essential for hypersonic aircraft applications beyond mere thermodynamic performance. The radar chart clearly demonstrates that the simple recuperated cycle exhibits the most balanced performance, excelling in all dimensions except thermal efficiency. This visual representation corroborates the findings from the detailed cycle analysis in Section 2.1, Section 2.2 and Section 2.3, where the simple recuperated cycle consistently demonstrated superior practical viability despite its moderate thermodynamic efficiency. In contrast, the recompression and cascaded split cycles achieve higher thermal efficiency but at the cost of significantly increased system complexity, reduced fuel economy, and challenging integration—trade-offs that are clearly visualized in the radar chart’s sharp, irregular polygons. The partial intercooling cycle shows moderate improvement in thermal efficiency over the simple cycle but still suffers from high complexity. The visualization underscores that for hypersonic aircraft, where reliability, compactness, and fuel efficiency are paramount, the simple recuperated cycle offers the most favorable trade-offs.

Figure 4.

SCO2 Brayton cycle hypersonic applicability radar chart assessment.

3. Research Status of SCO2 Brayton Cycle Applications

3.1. System Layout Characteristics

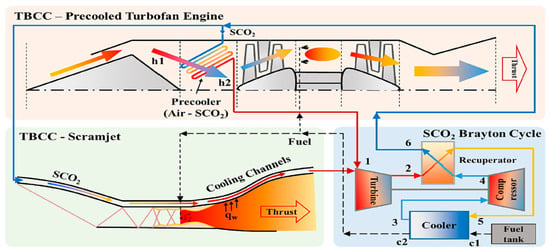

The analysis of the aforementioned cycle layouts primarily relies on steady-state conditions. However, the actual operational environment of hypersonic vehicles introduces the following two core constraints: the limited heat sink and stringent weight limitations. These constraints collectively define the performance boundaries and dynamic response characteristics of the cycle, making layout selection a complex multi-objective trade-off problem. Structure of supercritical carbon-dioxide Brayton cycle integrated with a turbine-based combined-cycle engine is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of the supercritical carbon-dioxide Brayton cycle integrated with a turbine-based combined-cycle engine [10]. Numbers denote key thermodynamic state points in the SCO2 cycle; solid arrows indicate primary working fluid flow, dashed lines show heat transfer paths; The color gradient in the diagram visually represents the temperature change of the working fluid throughout the cycle (red indicates high temperature, blue indicates low temperature).

The limited heat sink establishes a narrow operable range for the onboard SCO2 cycle. Its upper performance limit is constrained by the pinch point temperature difference (PPTD) in the cooler, while its lower limit is set by the turbine inlet temperature (TIT) and material temperature limits [11]. Under this constraint, the performance of the conventional recuperated layout (RL) is restricted. In contrast, the recuperative reheat layout (RRHL), through processes of staged expansion and subsequent cooling, effectively reduces the minimum CO2 flow rate required to meet the TIT limit, thereby broadening the operable range and theoretically increasing the maximum cycle work by approximately 7.0% [11]. This demonstrates that under limited heat sink conditions, innovative layout design aimed at fully utilizing the cooling potential of the CO2 working fluid holds greater engineering value than solely pursuing theoretical efficiency.

Recent coupled research targeting the hypersonic environment, utilizing a 1D model that integrates a scramjet, regenerative cooling channels, and the SCO2 Brayton cycle, clearly reveals the multi-dimensional trade-offs between cooling and power for different layouts under Ma8 conditions: the Simple Layout (SL) provides the best regenerative cooling performance (SCO2 cooling area ratio, Ar = 0.3) with a net power output of 249.0 kW, while the Recuperated Layout (RL) achieves superior thermodynamic performance, maximizing power to 274.0 kW, albeit at the cost of significantly reduced cooling performance (Ar = 0.2); the proposed Split-flow Recuperated Layout (S-RL) successfully strikes a balance, achieving a competitive power output of 261.0 kW while maintaining a strong cooling coverage (Ar = 0.3), thus demonstrating superior comprehensive performance [12].

From the perspective of system weight and dynamic characteristics, the total system weights of the SL and RL are 292.0 kg and 318.0 kg, respectively, with corresponding power-to-weight ratios (PWR) of 0.88 kW/kg and 0.86 kW/kg [10]. Furthermore, the SL, benefiting from fewer components and lower system inertia, exhibits smaller efficiency fluctuations and superior inherent stability during transients compared to the RL. Research indicates that under limited heat sink conditions, the system is susceptible to disturbances, potentially triggering a vicious cycle where increasing compressor speed and CO2 flow rate mutually reinforce, leading to significant performance degradation.

Recently, targeting the limited cold source and lightweight requirements of hypersonic vehicles, researchers have proposed various improved sCO2 cycle layouts. Dang et al. [8] proposed a novel thermal management system based on a three-sub-cycle closed Brayton architecture. By optimizing the split ratios and thermodynamic parameters, they reduced the cooling fuel mass flow rate to 0.3313 kg/s while maintaining the wall temperature below the safety limit, achieving a system net power of 162.4 kW. If the maximum fuel temperature is increased to 723.0 K, the fuel flow rate can be further reduced to 0.2907 kg/s, representing an 18.2% reduction compared to existing studies. This research demonstrates that in the hypersonic environment, enhancing fuel cooling efficiency is often more critical than solely pursuing theoretical thermal efficiency.

Furthermore, system weight and flight duration are critical trade-offs in hypersonic vehicle design. Luo et al. [9] systematically compared combined regenerative cooling with batteries/fuel cells against SCO2 CBC systems. Their results demonstrate a dynamic weight advantage: regenerative cooling with batteries is lightest for short missions (4.0~7.0 min), SCO2 CBC for medium durations, and regenerative cooling with fuel cells for long missions (35.0~309.0 min). Increasing compressor outlet pressure extends the SCO2 CBC’s weight advantage window, with recompression cycles outperforming simple regenerative cycles [9]. This expands system selection beyond thermal efficiency to mission-specific weight optimization, crucial for hypersonic vehicle design.

From the Table 1. analysis above that for hypersonic vehicles, where fuel availability, weight constraints, and operational reliability are paramount, maximizing thermal efficiency alone is not the optimal goal. The simple recuperated cycle stands out as the most favorable due to its superior balance of performance, complexity, and fuel economy, while the turbine-outlet split layout emerges as a powerful alternative for enhanced fuel saving. In contrast, the thermodynamic advantages of more complex cycles, such as recompression and reheat–recompression, are negated by their prohibitive integration penalties and excessive fuel consumption, rendering them uncompetitive in this practical context.

Table 1.

Performance comparison of different SCO2 cycle layouts for hypersonic applications.

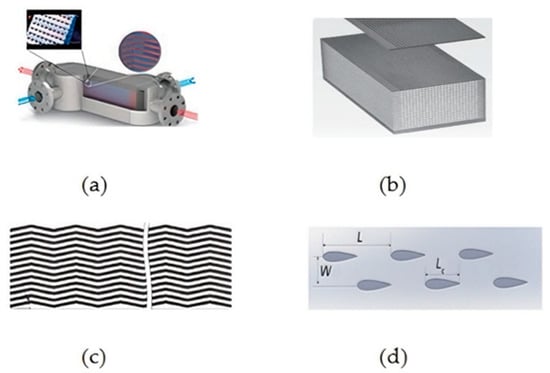

3.2. Printed Circuit Heat Exchanger

In simple recuperated cycles, 60.0~70.0% of total heat transfer occurs within recuperators [13], thus requiring essential studies on their thermal performance for overall efficiency enhancement. As compact heat exchange devices, printed circuit heat exchangers (PCHEs) deliver superior heat-transfer capabilities and high thermal effectiveness (>2500.0 m2/m3 surface density) due to their exceptionally large heat-transfer area [14]. The stringent volumetric and weight constraints inherent to airborne systems necessitate the adoption of such compact heat exchangers. To optimize system-level thermal performance and PCHE efficiency, researchers focus on flow channel geometry improvements. Current PCHE channel architectures are categorized into the following: continuous channels—straight, serpentine (Z-type), ladder-type, and sinusoidal (S-type) configurations; discontinuous channels—rectangular fins, elliptical fins, corrugated fins, and airfoil-shaped fins, which are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Conventional PCHE configuration and flow channels: (a) schematic diagram of the structure; (b) straight-channel type; (c) Z-shaped flow channel; (d) airfoil-shaped rib. In subfigure (a), the red color represents the high-temperature working fluid, and the blue color represents the low-temperature working fluid.

In addition to traditional Z-channels, the airfoil-fin printed circuit heat exchangers (AF-PCHEs) have garnered significant attention due to their excellent comprehensive thermal–hydraulic performance. Ye et al. [15] conducted a structural parameter optimization study on an SCO2-to-aviation kerosene AF-PCHE used in the scramjet power and thermal management system (PTMS). They optimized four key parameters—fin horizontal spacing (Lh), vertical spacing (Lv), cold-side channel height (Hc,RP3), and hot-side channel height —with the comprehensive performance coefficient (JF factor) as the objective. The study found that the hot-side channel height (Hc,CO2) had the most significant impact on the JF factor. The optimized structural parameters were Lh = 12.6 mm, Lv = 5.3 mm, Hc,RP3 = 1.1 mm, and Hc,CO2 = 1.4 mm. Compared to the original design, the optimized design’s JF factor increased by 24%, with more uniform flow and temperature field distributions. This research provides crucial guidance for the high-efficiency design and performance enhancement of PCHEs under the compact space constraints of hypersonic vehicles.

However, most existing PCHE studies assume ample ground cold sources, unlike hypersonic applications where fuel-limited cooling introduces unique challenges. Li et al. [16] demonstrated that fuel-side laminar flow at the PCHE inlet severely deteriorates heat transfer, necessitating longer flow channels that increase SCO2 pressure loss—the dominant factor limiting cycle efficiency. They identified a critical fuel mass flow rate (~1.6 kg/s) where transition from laminar to turbulent flow stabilizes system performance. Consequently, PCHE design for hypersonic vehicles must prioritize fuel-side flow state alongside SCO2 optimization to prevent localized heat-transfer degradation.

Beyond the flow state, the chemical transformation of the fuel itself presents a unique challenge and design paradigm shift. Zhou et al. [17] numerically investigated the coupled heat transfer between sCO2 and RP-3 aviation kerosene undergoing deep pyrolysis within a zigzag-type PCHE. They found that the chemical heat absorption from the pyrolysis reaction dominated the heat-transfer process, accounting for over 65% of the total. This introduces significant nonlinearity. Contrary to the conventional wisdom for PCHEs with small molecule fluids, where reducing channel diameter enhances heat transfer, they discovered that smaller diameters increased flow velocity and reduced fuel residence time, thereby suppressing the pyrolysis reaction and weakening the dominant chemical heat sink. Consequently, for this type of pyrolytic kerosene/sCO2 PCHE, optimal performance was achieved with a larger channel diameter (2.4 mm) and a smaller bend angle (30°), which prioritized facilitating the endothermic pyrolysis reaction over turbulent mixing. This study underscores that PCHE design for hypersonic vehicles must account for the complex coupling between fluid dynamics, heat transfer, and chemical kinetics.

3.3. Research on SCO2 Heat-Transfer Characteristics

The recuperator in the SCO2 Brayton cycle is typically operated near the pseudocritical point of CO2. However, near this point, CO2 exhibits dramatic variations in its thermophysical properties. This results in heat-transfer characteristics significantly different from those of traditional constant-property fluids. Consequently, accurately predicting the SCO2 heat-transfer coefficient over a wide range of operating conditions is challenging. Researchers have conducted numerous experiments under specific conditions to investigate the convective heat-transfer characteristics of SCO2 during pipe cooling. The flow of SCO2 inside pipes can be categorized into three heat-transfer modes: normal heat transfer, heat-transfer deterioration, and heat-transfer enhancement. Current research on SCO2 heat transfer primarily focuses on enhancing heat transfer and mitigating or avoiding heat-transfer deterioration. Furthermore, during the ascent or descent of hypersonic vehicles, the originally horizontal, highly forced flow transitions to upward or downward flow at a certain inclination angle, known as the flight attack angle. This angle influences the flow and heat-transfer characteristics of SCO2 within the cooling channels through buoyancy forces and secondary flows.

To investigate the influence of buoyancy and secondary flow on SCO2 flow and heat-transfer characteristics, Xu [18] noted that buoyancy is the primary factor affecting heat transfer in vertical flows. In upward channels, it weakens shear forces and deteriorates heat transfer, whereas in downward channels, it synergizes with shear forces to enhance heat transfer. Li et al. [19] studied SCO2 flow and heat transfer in heated upward and downward tubes, finding superior heat transfer performance in downward tubes. Upward tubes exhibited multiple heat transfer deterioration regions and wall temperature peaks. Li [20] found that in Z-type channels, secondary flow induced by boundary layer separation at turns is modulated by geometric parameters: reducing pitch length and bend angle intensifies secondary flow to enhance heat transfer at the cost of higher pressure drop, while smaller hydraulic diameter weakens this effect, yielding less pronounced heat transfer enhancement compared to straight channels. Shi et al. [21] systematically investigated the heat-transfer characteristics of sCO2 in inclined circular tubes using a method combining numerical simulation and deep learning. The study revealed significant circumferential inner wall temperature non-uniformity in inclined flows, with the temperature difference between the top and bottom generatrices increasing as the inclination angle approached 90° (horizontal). This temperature difference can induce substantial thermal stress and increase the risk of local over-temperature. To rapidly predict this two-dimensional heat-transfer behavior, the authors developed a deep neural network model (7 inputs–1 output) based on 520,000 numerical data points, achieving rapid 2D prediction of inclined sCO2 heat transfer with a maximum absolute relative error of 16.6% and prediction efficiency comparable to empirical correlations. This method provides a powerful tool for the initial design and rapid assessment of heat exchangers under transient operating conditions in hypersonic vehicles.

Liu Shenghui et al. [22] explored buoyancy’s impact on supercritical fluid heat transfer. The results indicate that in heated upward pipes, buoyancy reduces near-wall shear stress, disrupting local turbulence generation and diffusion, ultimately causing heat-transfer deterioration. They also derived a theoretical criterion for predicting the onset of heat-transfer deterioration in supercritical fluids. Chu et al. [23] observed that buoyancy effects under heating or cooling conditions cause non-uniform friction coefficient distribution, leading to flow stratification and secondary flow generation. This process elevates wall temperature at the pipe top while enhancing the local heat-transfer coefficient at the bottom; however, the buoyancy effect diminishes with decreasing pipe diameter.

3.4. Research on Cycle Operation Dynamic Characteristics

Although the recuperator significantly influences the performance of the SCO2 Brayton cycle, the cycle itself constitutes a complex integrated system comprising multiple components such as compressors, turbines, recuperators, and precoolers. Consequently, understanding the interactions among these components, the overall system performance, and the system’s response under various operating conditions becomes essential for practical application in hypersonic vehicles. Current research predominantly employs dynamic models of the system to simulate cycle performance and component responses across different operating conditions. For heat exchange equipment like recuperators, the prevalent dynamic modeling method involves solving reduced-dimensional or one-dimensional unsteady conservation equations using the finite volume method [24]. The one-dimensional approach discretizes the recuperator into a finite number of control volumes along the flow direction. Current literature broadly categorizes solution methods for SCO2 closed cycles into quasi-steady-state and transient approaches [25]. The key difference lies in their capabilities: Quasi-steady-state methods can only determine system behavior at a series of steady-state off-design operating points. They cannot capture the complex state changes occurring during non-equilibrium transitions. In contrast, transient methods comprehensively record the instantaneous operating states of all system components.

The dynamic operation of hypersonic vehicles imposes stringent demands on the sCO2 Brayton cycle. Analysis by Lang et al. [26] quantified these challenges, revealing an asymmetric system response where stabilization after a 5% power increase was 9.6% faster than after a decrease. Furthermore, disturbances in cooling fuel flow were 23.0% more impactful on stabilization time than temperature shifts. Critically, a mere 277.2 K rise in fuel temperature can precipitate a 14.9% surge in compressor power and a 15.7% drop in net efficiency. These findings, coupled with optimization results showing an 18.2% reduction in cooling fuel consumption is achievable [11], underscore the critical need for fast-response control strategies and precision pressure regulation to maintain system stability and efficiency.

The direct use of SCO2 for combustor wall cooling creates a strong combustor-cycle coupling, making decoupled performance analyses inapplicable for scramjets. Utilizing a 1D coupled model, Miao et al. [27] quantified the critical trade-offs, establishing fuel consumption as the paramount metric. Their proposed low-temperature recompression SCO2 (LRe-SCO2) cycle achieved a 38.5% reduction in cooling fuel consumption while delivering 211.4 kW of power, demonstrating that cycles must be optimized for this balance rather than pure thermal efficiency. Consequently, layout selection must rely on coupled analysis to weigh cooling, power, complexity, and weight, favoring designs like the simple recuperated or the recompression SCO2 cycle that excel in this integrated environment.

The dynamic operation discussed above must be further contextualized within the transient flight envelope of the hypersonic vehicle (e.g., acceleration, cruise, maneuvering). During flight, the thermal environment undergoes dramatic shifts. On the heat source side, the extreme thermal loads on the scramjet engine walls, which can reach up to 10.0 MW/m2 [1], are not constant but scale approximately with the cube of the flight Mach number (Ma). A rapid acceleration can precipitate a several-fold increase in heat flux, demanding a rapid response from the cooling system. Concurrently, on the heat sink side, the cooling capacity of the onboard fuel is itself a dynamic and constrained resource. The available heat sink fluctuates with engine thrust demands and preheating from aerodynamic effects. Research by Lang et al. [26] quantitatively underscores this vulnerability, revealing that a mere increase in fuel temperature to 277.2 K can trigger a 14.9% surge in compressor power and a 15.7% drop in net cycle efficiency.

This dynamic interplay between variable heat source and limited heat sink across the flight envelope critically influences cycle configuration selection. The simple recuperated cycle and its variants demonstrate superior robustness in this environment. Their lower system inertia enables a faster response to transient events. Furthermore, their performance is less dependent on sensitive parameters like split ratios, leading to more graceful performance degradation when the heat sink is constrained, as evidenced by the balanced cooling and power output of the split-flow recuperated layout (S-RL) under Ma8 conditions [9]. In stark contrast, the recompression and other combined cycles, despite their impressive design-point thermal efficiencies (e.g., 44.7% [6]), face significant challenges. Their additional components increase system weight and inertia, slowing their dynamic response. More critically, their high efficiency is acutely dependent on maintaining an optimal split ratio, which is impossible across a varying flight envelope, leading to performance degradation. The extreme control complexity required presents a substantial reliability risk. Consequently, this transient perspective reinforces the conclusion that for hypersonic vehicles, robustness and adaptability across the flight envelope are more critical than peak design-point efficiency, firmly establishing the simple recuperated cycle as the most favorable configuration.

3.5. A Hierarchical Modeling Framework for Unraveling Component Coupling Mechanisms

While previous sections have reviewed the state-of-the-art in component and cycle analysis, a significant gap exists in the structured methodology for progressing from fundamental understanding to the design and control of complex, integrated systems. To address this gap and guide future research beyond isolated case studies, this section proposes a novel, hierarchical modeling framework. This framework is designed to systematically unravel the component coupling mechanisms and dynamic interactions that are crucial for hypersonic vehicle applications, thereby offering a new methodology for approaching the study and development of sCO2 Brayton cycles.

The proposed framework is built upon four sequential, interconnected modeling tiers, each with a distinct objective, progressively increasing in complexity and fidelity, as follows:

Tier 1: Steady-State Thermo-Mechanical Coupling Model of a simple recuperated cycle. The foundation of the framework is a high-fidelity steady-state model of the simple recuperated Brayton cycle. This model integrates thermodynamics, fluid mechanics, and heat-transfer principles, employing iterative algorithms to solve key components, with particular focus on the recuperator’s performance. It serves as the benchmark and validation base, providing reliable system performance parameters (e.g., efficiency and heat exchange capacity) and establishing the initial design space.

Tier 2: Parametric Analysis of Working Fluid Velocity and Recuperator Design. Building upon the validated steady-state model, this tier focuses on investigating the critical relationship between working fluid velocity and recuperator structural parameters (e.g., diameter, length, number of channels). Through systematic parametric sweeps and sensitivity analysis, this stage quantifies the influence of these parameters on Reynolds number, heat-transfer coefficient, pressure drop, and overall system efficiency. The output provides direct theoretical guidance for optimizing compact heat exchanger design under specific mass flow and spatial constraints.

Tier 3: Dynamic Simple Recuperated Model and Component Coupling Investigation. This tier marks the transition from steady-state to transient analysis. The model is expanded to a non-steady-state formulation by introducing time-dependent governing equations and accounting for thermal inertia in components. Using numerical methods like the finite volume method, the model simulates the system’s response to transient operating conditions typical of hypersonic flight. The primary objective here is to probe the dynamic, bidirectional coupling between components, such as how a disturbance in compressor speed propagates through the system, affecting turbine work, recuperator effectiveness, and ultimately the heat sink capacity of the cooling channels.

Tier 4: Analysis of Complex Configurations and Split-Ratio Effects. The final tier involves constructing models of advanced cycle configurations, such as the recompression cycle. A key operational parameter, the split ratio, is introduced as a central variable. This stage aims to investigate the quantitative impact of the split ratio on the coupling between all major components (main compressor, recompressor, high- and low-temperature recuperators). It evaluates the trade-offs in dynamic performance and control challenges inherent in more efficient, but architecturally complex, cycles. This provides critical insights for selecting and tailoring cycles that balance efficiency with dynamic stability and weight under hypersonic constraints.

This systematic, tiered modeling framework offers a new, structured pathway for future research. It moves beyond analyzing individual cycles in isolation and provides a methodology to systematically understand and manage complexity, from basic principles to integrated system dynamics. Adopting this approach will accelerate the development of robust, efficient, and controllable sCO2 Brayton cycle systems for the next generation of hypersonic vehicle thermal management and power generation.

4. Conclusions

Through systematic comparative analysis of different cycle layouts, heat-transfer characteristics, and dynamic behaviors, this review draws the following core conclusions: (1) Cycle layout selection: The simple recuperated cycle demonstrates the best balance in system complexity, fuel efficiency, and integration feasibility, making it the most suitable layout for hypersonic applications. (2) Recuperator optimization direction: The Z-channel PCHE with a bend angle of 15.0° and small pitch offers the best comprehensive performance, making it an ideal choice for compact hypersonic systems. (3) Heat-transfer considerations: Cooling channel design must account for flow direction changes induced by flight attack angles, avoiding heat-transfer deterioration during upward flow. (4) Dynamic control requirements: The system responds slowly to transient conditions, urgently requiring the development of fast-response dynamic control strategies to cope with variable operating conditions of the vehicle. These comparative analysis conclusions provide clear design guidance and technical pathways for the engineering application of the sCO2 Brayton cycle in hypersonic vehicles.

Since its proposal as an active-cooling technology, continuous research efforts have focused on the SCO2 Brayton cycle itself, aiming to enhance cycle efficiency through investigations into cycle layout, internal components, and SCO2 heat-transfer characteristics within tubes. Current research on SCO2 Brayton cycle active-cooling technology for hypersonic vehicles primarily concentrates on the following three areas: optimizing cycle configuration to improve performance, enhancing heat-transfer performance under limited volume and weight constraints, and investigating the dynamic characteristics of components within the cycle system. Furthermore, establishing suitable dynamic models for the SCO2 Brayton cycle under diverse operating conditions has become a crucial research direction for its application in hypersonic vehicle active-cooling technology.

Current research identifies several developed SCO2 Brayton cycle configurations, as follows: (1) simple regenerative, reheat regenerative, recompression, pre-compression, and intercooling cycles. Simulation results indicate the reheat regenerative layout demonstrates particular suitability for onboard power-generation systems in hypersonic vehicles. (2) Regenerator research is primarily focused on structural optimization within printed circuit heat exchangers (PCHEs), with zigzag channels being a key focus. Optimization of apex angles and pitches is recognized as a critical approach for enhancing heat-transfer performance. (3) CO2’s unique thermophysical properties significantly influence cycle performance through buoyancy effects and secondary flows in heat-transfer processes. (4) Current cycle investigations are largely limited to steady-state conditions, revealing component interactions and system instabilities during transient operation. Given extended variable operating conditions in hypersonic flight, future research on SCO2 Brayton cycle active-cooling technology should prioritize fundamental transient dynamics studies. Key aspects include (1) dynamic characteristics of SCO2 flow in cooling channels during vehicle transients and (2) coupling mechanisms between components of the integrated thermal-electric power system under variable operating states.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.L. and G.S.; methodology, H.L. and G.S.; software, H.L. and G.S.; investigation, G.S. and L.Z.; resources, L.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, H.L., L.Z. and G.S.; writing—review and editing, S.X. and Q.X.; visualization, S.X.; project administration, H.L. and S.X.; funding acquisition, H.L. and S.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation, grant number 2023A1515110541, Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation, grant number 2025A1515010722 and Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation, grant number 2024A1515010637.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LRe-SCO2 | Low-Temperature Recompression Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Cycle |

| AF-PCHE | Airfoil-Fin Printed Circuit Heat Exchanger |

| PCHEs | Printed Circuit Heat Exchangers |

| RRHL | Recuperative Reheat Layout |

| PTMS | Power and Thermal Management System |

| PPTD | Pinch Point Temperature Difference |

| SCO2 | Supercritical Carbon Dioxide |

| LTR | Low-Temperature Recuperator |

| HTR | High-Temperature Recuperator |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| S-RL | Split-Flow Recuperated Layout |

| PWR | Power-to-Weight Ratio |

| HP | High-Pressure |

| LP | Low-Pressure |

| 1D | One-Dimensional |

| Ar | Cooling Area Ratio |

| Ma | Mach Number |

| RL | Recuperated Layout |

| SL | Simple Layout |

| ε | Pressure Ratio |

| d | Diameters |

| p | Pitches |

| θ | Deflection Angle |

| T | Temperature |

| T_max | Maximum Temperature |

| P | Pressure |

References

- Liu, S.; Feng, Y.; Cao, Y.; Gong, K.; Zhou, W.; Bao, W. Numerical simulation of supercritical catalytic steam reforming of aviation kerosene coupling with coking and heat transfer in mini-channel. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2019, 137, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Performance Analysis and Power Enhancement Study of SCO2 Closed Brayton Cycle with Finite Heat Sink. Master’s Thesis, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Q.-Q.; Luo, L.; Du, W.; Yan, H. Performance Analysis of Thermoelectric Conversion System Based on S-CO2 Closed Regenerative Brayton Cycle for Scramjet. Chin. J. Turbomach. 2024, 66, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ladislav, V.; Vaclav, D.; Ondrej, B.; Vaclav, N. Pinch point analysis of heat exchangers for supercritical carbon dioxide with gaseous admixtures in CCS systems. Energy Procedia 2016, 86, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feher, E.G. The supercritical thermodynamic power cycle. Energy Convers. 1968, 8, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Cho, Y.; Kim, M.S.; Kim, M. Characteristics and optimization of supercritical CO2 recompression power cycle and the influence of pinch point temperature difference of recuperators. Energy 2018, 147, 1216–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, J.; Bhattacharyya, S. Optimization of recompression S-CO2 power cycle with reheating. Energy Convers. Manag. 2009, 50, 1939–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, C.; Xu, J.; Tan, X.; Cheng, K.; Qin, J.; Liu, G. Performance analysis and optimization of a novel SCO2 closed-Brayton-cycle-based thermal management system for scramjets. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 254, 123879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Luo, L.; Xing, H.; Du, W.; Yan, H. Performance evaluation of regenerative cooling and closed Brayton cycle for hypersonic vehicles. Energy 2025, 333, 137356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Jiang, P.; Zhu, Y. Dynamic simulation and analysis of transient characteristics of a thermal-to-electrical conversion system based on supercritical CO2 Brayton cycle in hypersonic vehicles. Appl. Energy 2024, 359, 122686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, Y.; Li, X. Performance analysis and enhancement of onboard supercritical CO2 closed Brayton cycles for hypersonic vehicles. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2025, 116, 109957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Guo, H.; Jiang, P.; Zhu, Y. Performance analysis and design optimization of a supercritical CO2 Brayton cycle cooling and power generation system coupled with a scramjet. Appl. Energy 2025, 383, 125362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshram, A.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Khivsara, S.D.; Ortega, J.D.; Ho, C.; Bapat, R.; Dutta, P. Modeling and analysis of a printed circuit heat exchanger for supercritical CO2 power cycle applications. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 109, 861–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Z.-H.; Liao, S.-M. Numerical Simulation of Laminar Flow and Heat Transfer of Supercritical CO2 in Horizontal Mini/Micro Tubes. J. Therm. Sci. Technol. 2005, 4, 113–117. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, T.; Zhou, Y.; Bao, Z. Optimization of structural parameters of airfoil-fin printed circuit heat exchanger for power and thermal management system of hypersonic vehicles. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2024, 54, 102877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, S. Performance analysis of scCO2 closed Brayton cycle applied to aero engine thermal protection considering flow and heat transfer characteristics inside the scCO2-fuel heat exchanger. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2026, 228, 106787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, S.; Guo, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, H.; Bao, W. Study on coupled heat transfer of pyrolytic kerosene and supercritical CO2 in zigzag-type PCHE used for hypersonic vehicle power generation system. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 247, 123101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.-N.; Luo, F.; Jiang, P.-X. Experimental research on the turbulent convection heat transfer of supercritical pressure CO2 in a serpentine vertical mini tube. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2015, 91, 552–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-H.; Jiang, P.-X.; Zhao, C.-R.; Zhang, Y. Experimental investigation of convection heat transfer of CO2 at supercritical pressures in a vertical circular tube. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2010, 34, 1162–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. Flow and Heat Transfer Characteristics of Supercritical CO2 in Printed Circuit Heat Exchanger. Master’s Thesis, Lanzhou University of Technology, Lanzhou, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Chai, X.; Chen, W.; Chyu, M.K. Rapid 2-Dimensional prediction of supercritical CO2 heat transfer behaviors in inclined tubes based on deep learning. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 240, 122244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.-H.; Huang, Y.-P.; Liu, G.-X.; Wang, J.-F.; Jiu, Y.-F.; Lang, X.-M. Improvement of Buoyancy Factor and Flow Acceleration Factor and Their Application in Mixed Convection Heat Transfer of Supercritical Fluid. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2017, 47, 176–189. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, X.; Laurien, E. Flow stratification of supercritical CO2 in a heated horizontal pipe. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2016, 116, 172–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y. Study on Dynamic Characteristics of Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Brayton Cycle System. Master’s Thesis, North China Electric Power University, Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z. Investigation on Flow and Heat Transfer Characteristics of Supercritical Carbon Dioxide and Dynamic Simulation of Brayton Cycle. Ph.D. Dissertation, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, L.; Jiang, F.; Cheng, K.; Liu, Z.; Wang, S.; Dang, C.; Qin, J.; Huang, H.; Zhang, X. Dynamic characteristics analysis of supercritical CO2 closed Brayton power generation system for hypersonic vehicles. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 269, 126016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, H.; Che, X.; Geng, T.; Wang, X.; Qiang, H. Coupled modeling and performance analysis of a supercritical CO2 cycle cooling system integrated with the actively cooled combustor for scramjets. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 280, 128492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).